Chapter 2. Skills and global value chains: What are the stakes?

This chapter explores how investing in skills and knowledge can increase country’s ability to make the most of global value chains (GVCs), socially and economically. It shows how GVCs have developed and the extent to which countries vary in their participation in these chains; examines the benefits that participation in GVCs can have for productivity growth, especially when it goes hand in hand with investment in skills; shows how participation in GVCs can affect employment and inequalities; outlines the characteristics that expose jobs to the risk of offshoring and the implications for workers’ skills; and investigates how participation in GVCs affects job quality and how stronger skills and better education can translate participation in GVCs into better jobs.

Over the last two decades, international patterns of production and trade have changed, leading to a new phase of globalisation. Each country’s ability to make the most of this new era, socially and economically, depends heavily on how it invests in the skills of its citizens.

In this new phase of globalisation, production is increasingly fragmented, with different stages of production dispersed among different suppliers in different countries, to form global value chains (GVCs). This fragmentation has increased trade in intermediate goods and services – semi-finished inputs, or components, of the final product or service. Countries now specialise in tasks rather than in specific products.

This growing interconnectedness of economies presents countries with opportunities and challenges, many of which affect or are affected by the skills of the population. GVCs intensify competition worldwide, forcing firms to become more productive. Trade in intermediate goods and services that incorporate technology fosters the spread of knowledge, as it requires workers who are skilled in learning from new technologies. GVCs lead to reallocation of tasks and jobs as companies relocate or outsource processes, making some skills less or more needed. They also reshape international investment, as multinationals account for an increasing share of global trade.

Globalisation is generally thought to strengthen economic growth and welfare, especially when accompanied by rising educational attainment, as has been the case over the past few decades. However, today it is facing strong headwinds – productivity has slowed, inequalities have risen and high unemployment rates have persisted in many countries (OECD, 2015a; OECD, 2016a). More and more people are concerned about the consequences of the intensification of globalisation. One of the major challenges for governments is to understand how investing in skills and knowledge can increase countries’ competitiveness in GVCs with the objective of moving to higher value-added activities and improving job quality.

This chapter aims at shedding light on this challenge by investigating the links between GVCs, productivity, inequality and job quality. It investigates how skills can shield individuals and firms from harm that globalisation might cause and help countries derive the greatest advantage from GVCs. In particular, this chapter:

-

Shows how GVCs have developed and the extent to which countries vary in their participation in these chains.

-

Examines the benefits that participation in GVCs can have for productivity growth, especially when it goes hand in hand with investment in skills.

-

Shows how global value chains have increased the share of employment exposed to global trade and how participation in GVCs can affect jobs and inequalities.

-

Outlines the characteristics that expose jobs to the risk of being relocated to other countries (offshoring) and the implications for workers’ skills.

-

Investigates how participation in GVCs affects job quality and how stronger skills and better education can translate participation in GVCs into better jobs.

The main findings in this chapter include:

-

Participation in GVCs has increased significantly in many countries over the last two decades. On average, 30% of the value of exports of OECD countries now comes from abroad. In many OECD countries, up to one-third of jobs in the business sector depend on foreign demand.

-

GVCs can improve productivity. Countries with the largest increase in participation in GVCs over the period 1995-2011 have benefited from additional annual industry labour productivity growth ranging from 0.8 percentage points in industries that offer the smallest potential for fragmentation of the production process to 2.2 percentage points in those with the highest potential.

-

Investing in skills ensures that participation in GVCs increases productivity, because firms need workers who can learn from new technologies. This is particularly important for small and medium-sized firms that are lagging behind in terms of productivity growth.

-

The effects of global value chains on employment and inequalities are difficult to assess:

-

Import competition from low-cost countries such as China has led to a fall in employment, especially in the manufacturing sector. However, competition from low-cost countries, which mainly affects low-skilled jobs, is only one aspect of GVCs. OECD countries import business services and intermediates from high-tech manufacturing industries but also export these products, making it difficult to gauge the overall employment effect.

-

There is no clear relationship between participation in GVCs and inequalities within countries. Skill-biased technological change – which favours skilled over unskilled workers – and institutions are important determinants of inequalities while competition from low-cost countries seems to play a smaller role.

-

-

While GVCs do not appear to be the main driver of employment and inequality, some characteristics of jobs make them more likely to be relocated offshore, such as routine task content and lack of face-to-face contact. Investing in skills makes workers less exposed to the risk of losing their jobs because of offshoring.

-

Investing in skills can also limit the risks that participation in GVCs leads to lower job quality, especially in the form of higher job strain for low-skilled workers. In both emerging economies and developed countries, job quality increases substantially as educational attainment improves.

Countries’ involvement in global value chains: facts and trends

Measuring the development of global value chains

Over the last two decades, digitalisation, decreasing trade barriers, and the search for efficiency gains have led countries to specialise in activities that create as much value as possible and to offshore other activities. The production process has become increasingly fragmented among different countries, while trade in intermediate goods and services has expanded, leading to the development of GVCs.

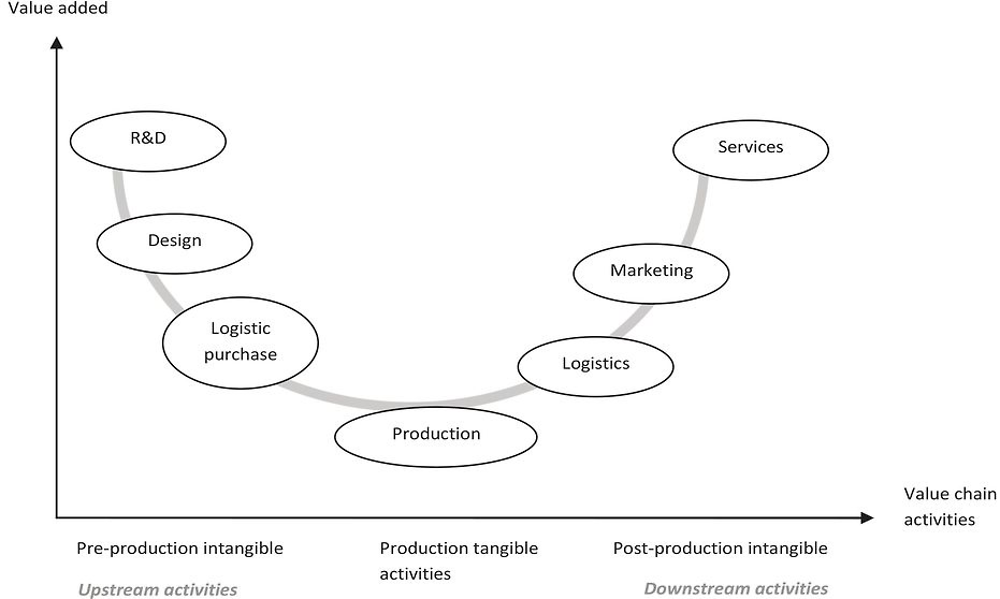

Each stage in the production process has a different potential to add value. This difference is often presented as a “smiling curve” (Figure 2.1). While this curve does not capture the complexity of the organisation of the production process in GVCs, it can help illustrate what is meant by GVCs. The smiling curve was originally proposed by Stan Shih, the founder of Acer, an information technology (IT) company, to illustrate the problems of IT manufacturers in Chinese Taipei, which found itself locked along the bottom of the curve (Shih, 1996).

Source: OECD (2013), Interconnected Economies: Benefiting From Global Value Chains, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264189560-en.

According to the smiling curve, in many activities the most value is typically added in either upstream activities, such as the development of a new concept, research and development (R&D) and the manufacturing of key components, or downstream activities, such as marketing, branding and customer service. In-between activities, such as product assembly, add the lowest share of value along the supply chain. These activities tend to be offshored to emerging and developing economies.

The emergence of GVCs has pushed forward the development of value-added measures of trade. As inputs pass through value chains, they cross borders many times, which means that exports in gross terms overstate the amount of domestic value added in exports. In addition, gross trade statistics give a distorted picture of the importance of trade for economic growth and income, as countries with final producers appear to be capturing most of the value of goods and services traded, even though these exports may depend on significant imports (Johnson, 2014). The OECD Trade in Value Added (TiVA) database measures the origin of value added embodied in exports, making it possible to distinguish between foreign and domestic value added content of exports (Box 2.1).

The OECD Trade in Value Added (TiVA) database measures the origin of value added embodied in any goods or services exported. In doing so, it addresses the issue of double counting of value added that is implicit in reported gross trade flows. The TiVA framework can reveal the global origins of the cumulative value added present in final goods and services consumed by households, government and businesses. Accounting for trade in value added (especially trade in intermediate parts and components) redistributes surpluses and deficits across partner countries while leaving the overall trade balances of countries with the rest of the world unchanged

The TiVA database based on the October 2015 update of the OECD Inter-Country Input-Output (ICIO) tables covers 61 countries, 34 industries and 7 years (1995, 2000, 2005 and all years between 2008 and 2011). Constructing a global input-output table presents many challenges, and entails making several assumptions, as well as reconciling and balancing data. This means that some care is needed in interpreting results, especially given the aggregate nature of the underlying input-output table. All indicators presented in this chapter are estimates of some aspects of GVCs and thereby should be interpreted with care.

The TiVA database reveals new insights into global interconnectedness and bilateral relationships. It captures the degree of fragmentation of trade, the value added exported by countries and industries, and the interconnections between countries arising from trade. The database is a rich source of information on the development of GVCs and the extent to which countries and industries are integrated into GVCs.

Source: OECD Trade in Value Added database (TiVA), https://stats.oecd.org/index.aspx?queryid=66237.

The value added of gross exports can be separated into: i) the domestic value added of gross exports and ii) the foreign value added coming from the use of foreign intermediates in a country’s exports. The use of foreign intermediates in exports includes the offshoring of activities to other countries but is a broader concept than offshoring, as some activities may have always been done in another country and not just recently relocated. In recent decades, the share of domestic value added in exports in the manufacturing sector has declined in many economies while trade in intermediates has increased (Johnson and Noguera, 2012). This trend reflects the growing role of GVCs in trade flows. Now, more than half of world trade in manufacturing goods consists of intermediate goods and more than 70% of trade in services involves intermediate services.

How countries participate in global value chains

Participation in GVCs takes two main forms: i) importing foreign inputs for exports or backward participation; and ii) producing inputs used in third countries’ exports, or forward participation. Participation in GVCs is generally assessed through a participation index by looking at its two forms as a share of countries’ exports or of foreign final demand.

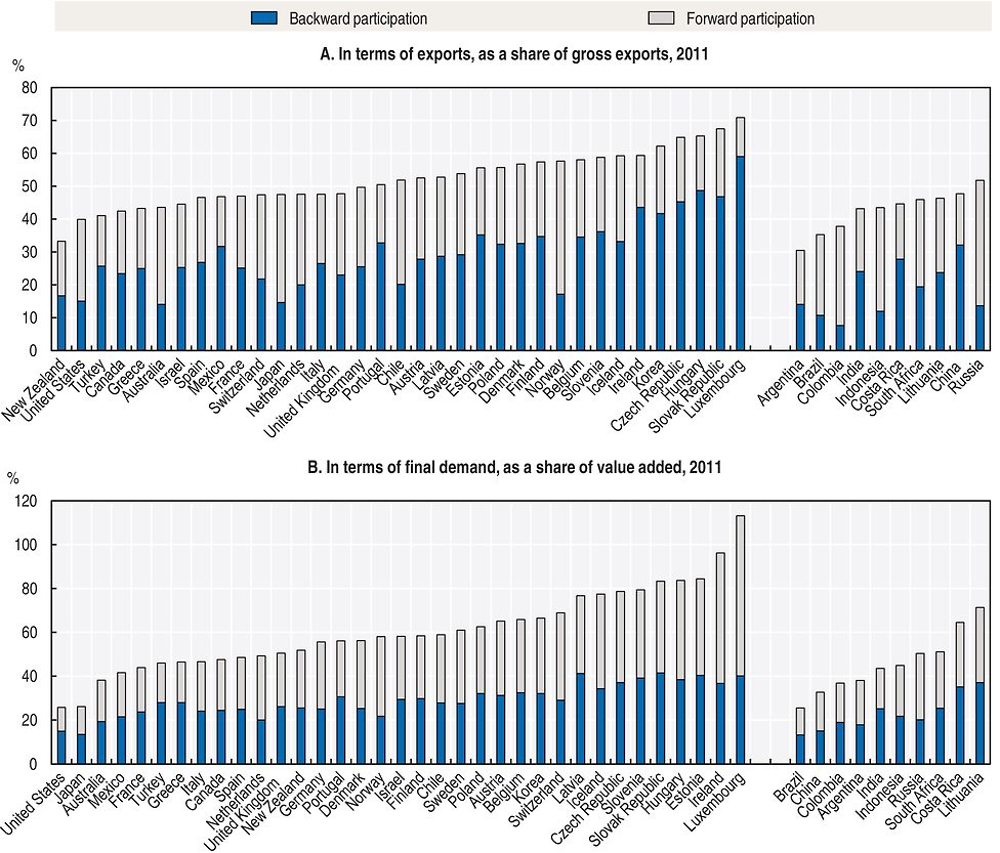

Countries vary greatly in terms of their participation in GVCs (Figure 2.2, Panel A) because of their economic structure and other characteristics (De Backer and Miroudot, 2013; Johnson and Noguera, 2012; UNCTAD, 2013). Such characteristics include:

Note: Forward and backward participation in terms of final demand are respectively the domestic value added embodied in foreign final demand and the foreign value added embodied in domestic final demand divided by countries’ value added.

Source: OECD calculations based on OECD Trade in Value Added database (TiVA), https://stats.oecd.org/index.aspx?queryid=66237.

-

Size of the economy. Large economies such as Japan and the United States have larger internal value chains and rely less on foreign inputs than smaller economies, such as Luxembourg. However, much depends on the ability of the domestic market to provide the required intermediate inputs, as well as the nature of the country’s engagement in GVCs. China, for example, has large backward linkages reflecting its significant (albeit declining) share of processing activities.

-

Composition of exports. Countries with a high share of natural resources in their exports have a higher share of domestic value added in their exports. Also, countries that have a high share of both upstream and downstream services in their exports tend to add more value. Overall, positioning in GVCs (Figure 2.1) influences the share of domestic value added in exports. Countries at the beginning of the value chain (exports of raw materials and R&D services) and at the end of the chain (exports of logistics and after-sales services, like the United States) tend to have a higher share of domestic value added in their exports. Countries that export value added in highly fragmented industries, such as Germany, have a higher share of foreign intermediates in their exports. Countries such as Australia, Japan, and Norway have strong forward participation as they export intermediate products that are used in the exports of third countries.

-

Economic structure and export model. Countries with a higher share of foreign value added include those specialised in the assembly of intermediate inputs from various countries for consumption in third markets and those with significant shares of entrepôt trade. An entrepôt is a transhipment port where merchandise may be imported, stored or traded, usually to be exported again.

Participation in GVCs can also be assessed in terms of final demand (Figure 2.2, Panel B), or the extent to which countries are connected to final consumers in other countries where no direct trade relationship exists. A country can export products that reach final consumers through the export of third countries (forward participation). A country can also be connected to other countries through the use of foreign inputs that end up in domestic final demand (backward participation). Forward participation tends to be higher in terms of final demand than in terms of exports in OECD countries, reflecting their leading role in exporting value added that reaches final demand. The opposite holds for non-OECD countries.

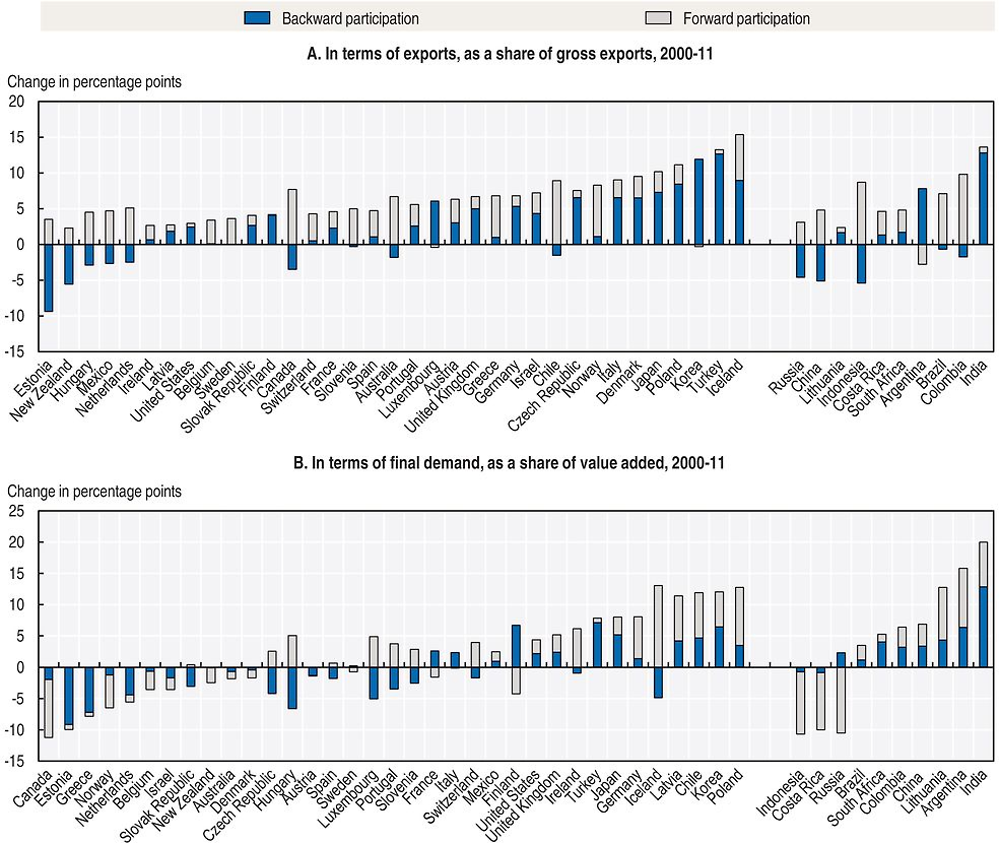

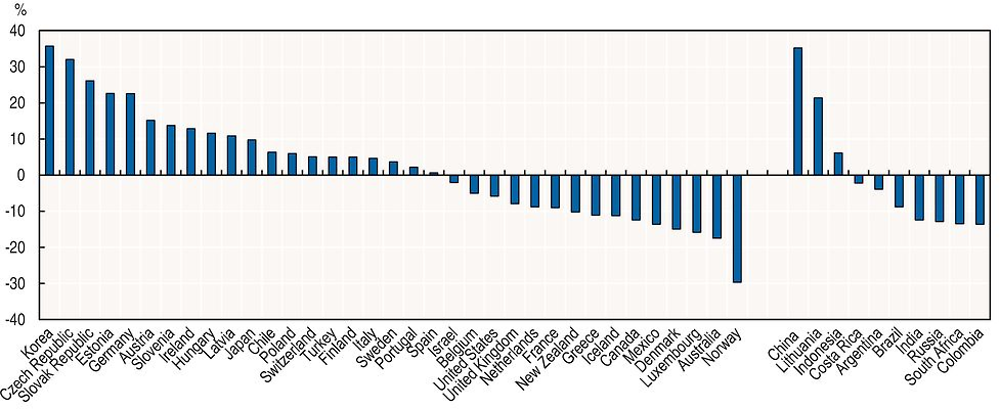

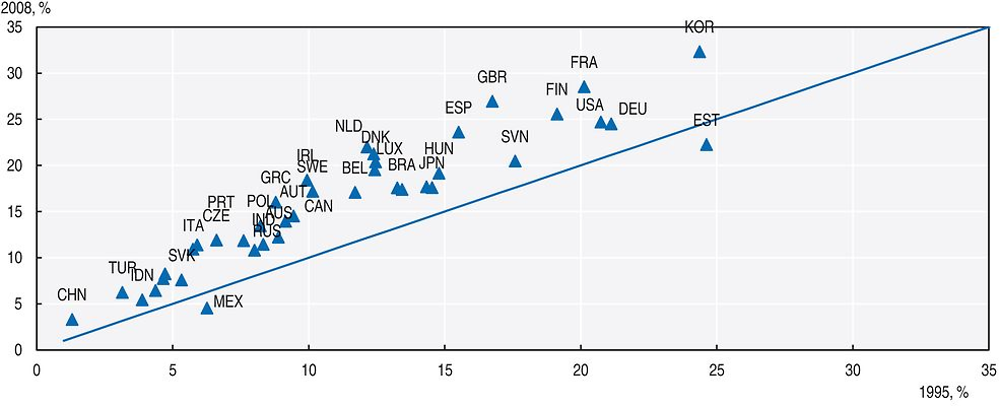

In the last two decades, most countries have increased their participation in GVCs (Figure 2.3). Many countries have offshored activities in certain industries to increase their specialisation in other activities (Johnson and Noguera, 2012; Timmer et al., 2014; Chapter 3). A group of countries, including Japan, Ireland, Poland, Latvia and Lithuania, have increased their outreach to final consumers through forward participation.

Source: OECD calculations based on OECD Trade in Value Added database (TiVA), https://stats.oecd.org/index.aspx?queryid=66237.

Several misguided ideas exist about what countries should aim to achieve in relation to GVCs. One is that raising participation in GVCs could be an objective per se. The participation index reflects the nature of participation in GVCs, the influence of several inherited factors and, in the end, simply the extent to which countries’ exports are integrated in an internationally fragmented production network. Another is that countries should aim to increase the domestic value added share in their exports (or limit backward participation), as the foreign value added part measures the extent to which the contribution of exports to gross domestic product (GDP) is absorbed by other countries in the value chain. However, this accounting does not capture the indirect gains of participation. Backward participation enables countries to specialise in the most productive activities, to achieve gains from declining costs of intermediate goods and services, and to benefit from technology transfer through the use of inputs with high technology content (see next section).

Countries’ positioning in global value chains

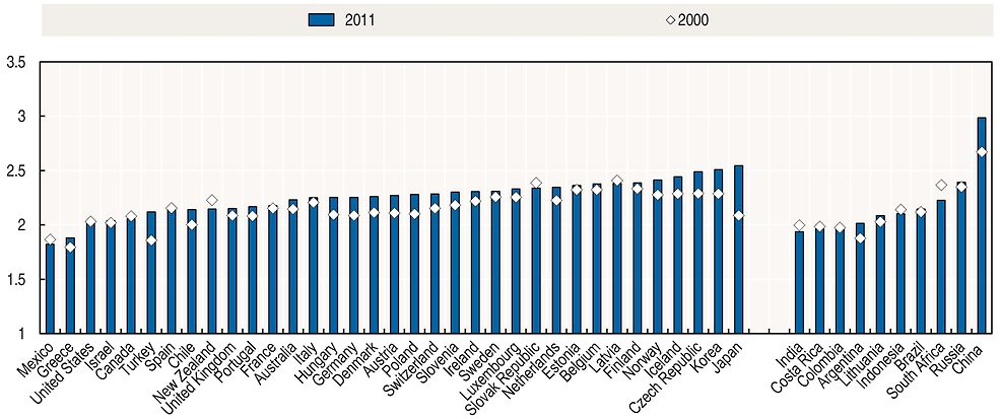

Several indicators measure the positioning and specialisation of countries within GVCs. Countries can be located upstream at the beginning of the value chain, in activities such as producing raw materials or intangibles (research and design), or downstream at the end of the value chain in activities such as assembling processed products, logistics and customer services. The “distance to final demand” indicator measures how many stages of production are left before goods or services reach final demand (De Backer and Miroudot, 2013; Figure 2.4). Some economies, such as the United States, are generally located downstream, as they specialise in activities close to final consumption such as marketing and sales. By contrast, Japan and Korea are located upstream, as they provide other countries with high-tech components before the assembly phase.

In many countries, the average distance to final demand has increased because chains have lengthened as production has become more fragmented. Countries in which the distance has increased the most may have moved downstream.

Note: The distance to final demand indicator measures how many stages of production are left before the goods or services produced reach final demand. Average distance across industries to final demand in industries excluding agriculture, hunting, forestry and fishing; mining and quarrying; private households with employed persons.

Source: OECD calculations based on OECD Trade in Value Added database (TiVA), https://stats.oecd.org/index.aspx?queryid=66237.

The distance to final demand indicator does not fully describe how countries are positioned in GVCs and how this positioning has evolved. For instance, the United States tends to control upstream activities such as design as well as downstream activities such as sales, but only the downstream aspect is reflected by the distance to final demand. “Factory-less” goods producers, which design and co-ordinate the production process of manufacturing goods, are engaged in both upstream and downstream activities, but input-output tables typically bundle these into one downstream activity (Bernard and Fort, 2013).

The income generated by GVCs is unevenly distributed among countries. One way of estimating how well countries perform in GVCs is to look at their income generation within GVCs as related to their size (Figure 2.5). Half of the OECD countries generate larger shares of income within GVCs than their relative size. The leading emerging economies, except China and Indonesia, contribute to a smaller share of income within GVCs than their relative size.

Note: Average GVC income share in industries (country GVC income divided by world’s GVC income per industry) excluding Agriculture, hunting, forestry and fishing; Mining and quarrying; and Private households with employed persons. Income shares are divided by countries’ value added share in total value added. Countries above (below) the horizontal axis have on average a larger (smaller) share of GVC income than their average value added share.

Source: OECD calculations based on OECD Trade in Value Added database (TiVA), https://stats.oecd.org/index.aspx?queryid=66237.

Global value chains, productivity, employment and inequality

How can global value chains increase productivity?

By specialising in tasks in which they have a comparative advantage, companies and countries can increase their productivity. If firms can relocate the less efficient parts of their production process to countries that can carry out these tasks more cheaply, they can expand their output in more efficient production stages (Antras and Rossi-Hansberg, 2009). This so-called “unbundling” of production, or the offshoring of both manufactured and service-based inputs, has been shown to be equivalent to a technological improvement.

In the United States, for instance, service offshoring in the manufacturing sector has accounted for around 10% of labour productivity growth between 1992 and 2000 (Amiti and Wei, 2006). By trading tasks or unbundling production, firms can enjoy the productivity benefits of worker specialisation without sacrificing the gains from locating production in the most cost-effective location (Grossman and Rossi-Hansberg, 2008).

Participation in GVCs increases competition among firms, leading to the reallocation of workers and capital towards the most productive firms. Trade increases the minimum productivity level that is required for firms to survive in the market (Melitz, 2003). As a result, only the most productive firms enter the export market. Less productive firms continue to produce only for the domestic market, while the least productive firms are forced to exit. The reallocation of resources towards the most productive firms contributes to an aggregate productivity gain. The increased competition arising from trade is expected to be exacerbated by GVCs, as firms and countries now compete in terms of tasks as well as in terms of products. The possibility of offshoring activities can also increase competition.

International trade and foreign direct investment (FDI) are major channels of technology diffusion among countries (Keller, 2004). Imports are a significant channel of technology diffusion, but the evidence is weaker that firms learn about foreign technology through exporting – for example, through foreign customers imposing higher standards on exporting firms.

In theory, FDI is a channel for technology diffusion, as technology is supposed to be shared among the multinational parent and its subsidiaries. Most recent studies do tend to find that FDI aids the diffusion of technology (Keller, 2004; Javorcik, 2014), but the empirical evidence for such FDI spillovers is mixed. In addition, the diffusion of technology is only one of the spillover effects of FDI, which also include the transfer of tacit knowledge, know-how, management techniques and marketing strategies within multinationals.

Assessing the impact of participation in global value chains on productivity growth

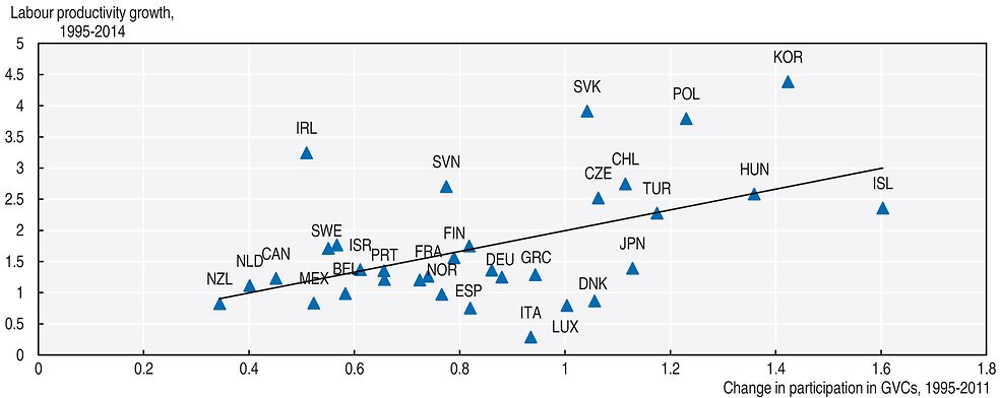

In recent decades, countries’ integration into GVCs has increased substantially overall, but productivity has slowed down in most OECD countries (OECD, 2016a). Simple correlations suggest that countries that have increased their participation in GVCs a lot over the period 1995-2011 also had stronger labour productivity growth (Figure 2.6). These correlations have to be interpreted carefully, however, as the links between productivity and GVCs run in both directions. Firms with high productivity that face low international transport costs tend to choose exporting and importing (Baldwin and Yan, 2014; Kasahara and Lapham, 2013; Melitz, 2003). In return, participation in GVCs can lead to some productivity gains arising from both the use of foreign intermediates (backward linkages) and the export of products used in third countries’ exports (forward linkages).

Source: OECD Productivity Database, http://stats.oecd.org/; OECD Trade in Value Added database (TiVA), https://stats.oecd.org/index.aspx?queryid=66237.

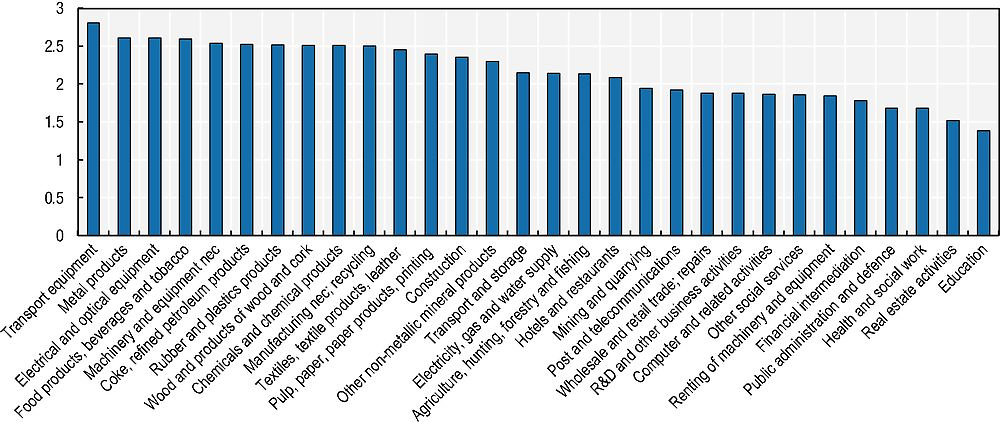

As the relationship between participation in GVCs and productivity runs in both directions, it is difficult to show that participation in GVCs increases productivity. One option to remedy this issue is to assess whether countries with strong participation in GVCs have stronger productivity growth in industries that have a higher potential for fragmentation of the production process (Formai and Vergara Caffarelli, 2015). Industries differ by how much they are fragmentable, as reflected by the average length of GVCs in OECD countries by industry, measured by the number of stages involved in the production process (Figure 2.7). Manufacturing industries show the highest level of fragmentation and services industries the lowest.

Source: OECD calculations based on OECD Trade in Value Added database (TiVA), https://stats.oecd.org/index.aspx?queryid=66237.

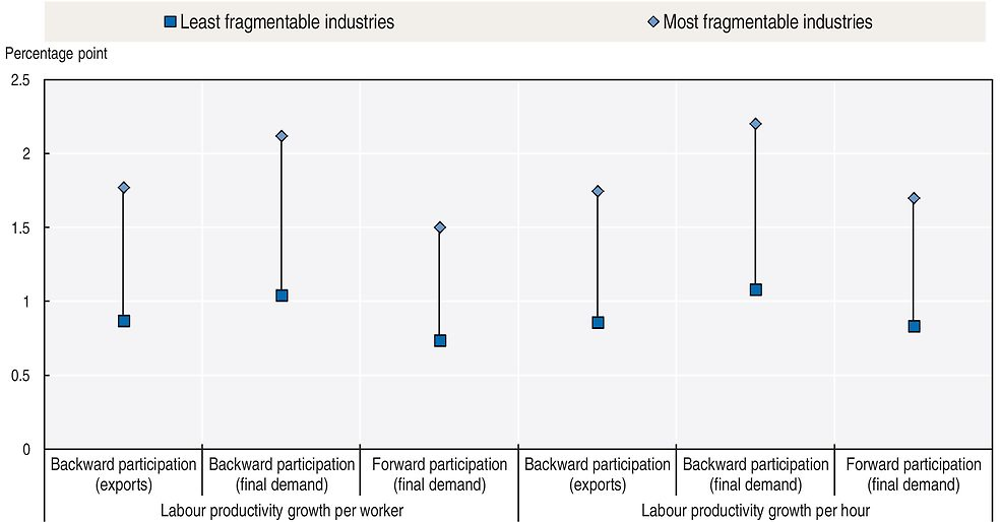

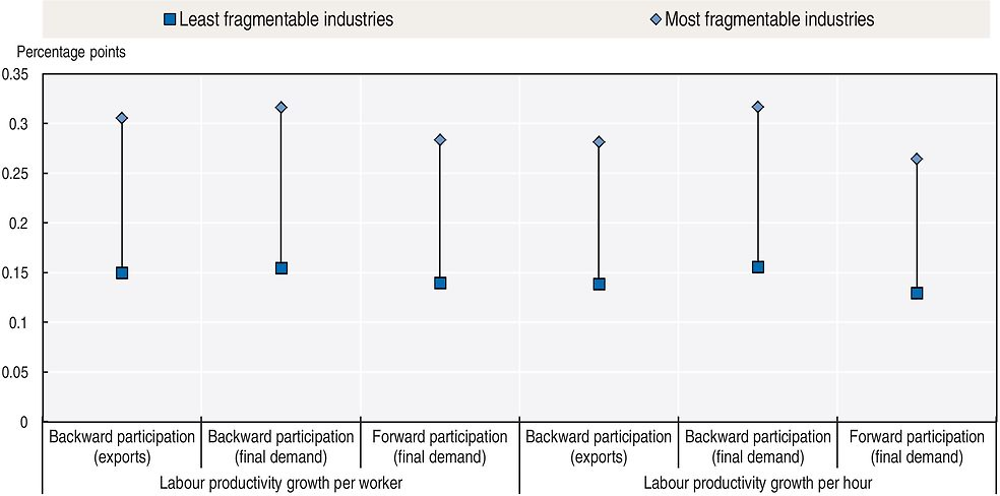

Empirical estimates suggest that increasing participation in GVCs can lead to labour productivity growth (Box 2.2): countries with stronger GVC participation in the beginning of the period have had stronger productivity growth in industries that offer higher potential for fragmentation. The annual gains in industry labour productivity growth range from 0.8 percentage points in the least fragmented industry to 2.2 percentage points in the most fragmented industry (Figure 2.8). Such an increase in labour productivity could be achieved by raising backward participation by 15 percentage points, which is what countries with the biggest change in participation in GVCs over the period 1995-2011 have experienced. Hence, these estimates tend to show the maximum gains countries may have experienced over the period.

While global value chains are generally considered to offer potential for productivity gains, the links between the two have seldom been tested empirically. Exceptions include a study that shows that multi-factor productivity grew faster in industries that experienced larger increases in GVC participation (Saia, Andrews and Albrizio, 2015). However, as more productive firms tend to choose GVC participation, this relationship cannot be interpreted in a causal way.

In an attempt to address this issue, a different approach is proposed here following another recent study (Formai and Vergara Caffarelli, 2015). This new assessment investigates whether countries with the highest participation in GVCs in the beginning of the period experienced higher productivity growth rates over the time periods 1995-2009 (or 2000-09) in industries that offer the highest potential for fragmentation of the production process. This methodology, which explains industries’ productivity growth by the interaction between a country-specific measure of participation in GVCs and an industry-specific characteristic of potential for international fragmentation, can address some of the causality issues (Rajan and Zingales, 1998). It is however unlikely that this approach solves all the causality issues and therefore, should be considered as tentative and its results should be interpreted with caution.

The analysis uses data from the OECD-WTO TiVA database, the World Input-Output Database (WIOD) and the OECD Inter-Country Input-Output (ICIO) tables to test the relationship between countries’ participation in GVCs and industries’ productivity growth in a sample of 35 countries and 30 industries over the 1995-2009 period. The potential of industries for fragmentation of the production process is approximated by the average length of the global value chain of industries in OECD countries over all years (Figure 2.7). Two measures of labour productivity are considered, by employer and by hour. Other variables include the industry’s share of a country’s value added, the country-industry’s capital stock, the country-industry’s shares of high-skilled and medium-skilled workers, all taken in the beginning of the period, and industry and country fixed effects.

The results of this analysis are shown in two sections of this chapter. Figure 2.8 shows the impact of an increase in participation in GVCs at a country level on industry productivity growth depending on their potential for fragmentation. Figure 2.15 proposes a tentative estimate of the share of productivity gains that stems from the fact that some industries had a higher proportion of high- and medium-skilled workers at the beginning of the assessment period. This is achieved by comparing the estimated impact of countries’ participation in GVCs on industries’ productivity growth when the skills intensity of industries is accounted for versus when skills intensity is not accounted for.

Source: Formai, S. and F. Vergara Caffarelli (2015), “Quantifying the productivity effects of global value chains”, Cambridge Working Paper in Economics, No. 1564.

Rajan, R.G. and L. Zingales (1998), “Financial dependence and growth”, The American Economic Review, Vol. 88, No. 3.

Saia, A., D. Andrews and S. Albrizio (2015), “Public policy and spillovers from the global productivity frontier: Industry level evidence”, OECD Economics Department Working Papers, No. 1238.

Note: Gains in productivity growth coming from an increase from the 25th percentile of the distribution of integration to the 75th percentile. This corresponds to an increase by 15 percentage points for backward participation in terms of exports, 13 percentage points for backward participation in terms of final demand, and 12 percentage points for forward participation in terms of final demand. See Box 2.2.

Source: OECD calculations based on OECD Trade in Value Added Database (TiVA), https://stats.oecd.org/index.aspx?queryid=66237; and World Input-Output Database (WIOD), www.wiod.org/home.

Global value chains and jobs

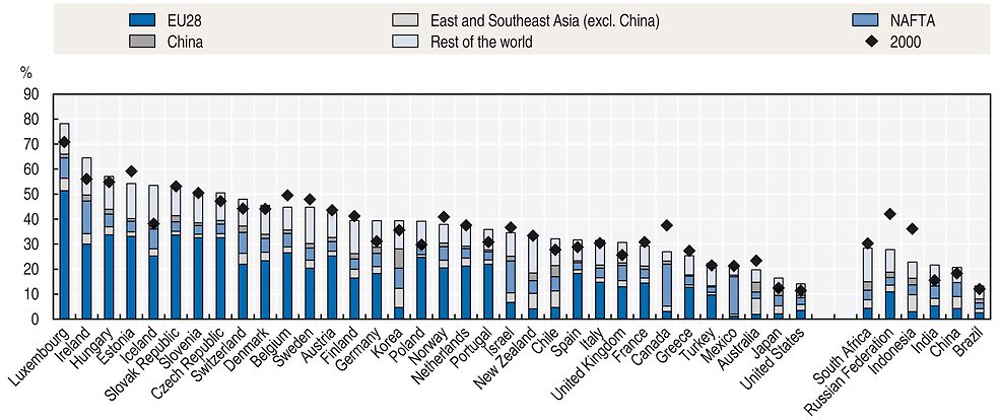

Many jobs are connected to GVCs and therefore depend on consumers in other countries. The development of GVCs has deepened dependencies between economies (OECD/World Bank, 2015). Estimates of how many jobs are sustained by foreign final demand reveal the extent of a country’s integration into the global economy and therefore, the exposure of its labour market to external shocks (Figure 2.9).

Note: The business sector is defined according to ISIC Rev.3 Divisions 10 to 74 i.e. total economy excluding agriculture, forestry and fishing (Divisions 01 to 05), public administration (75), education (80), health (85) and other community, social and personal services (90 to 95). East and Southeast Asia (excluding China) comprises Brunei Darussalam, Cambodia, Indonesia, Hong Kong (China), Japan, Korea, Malaysia, Philippines, Singapore, Chinese Taipei, Thailand and Viet Nam.

Source: OECD (2015b), OECD Science, Technology and Industry Scoreboard 2015: Innovation for Growth and Society, https://doi.org/10.1787/sti_scoreboard-2015-en.

In 2011, more than 30% of jobs in the business sector in most OECD countries were sustained by consumers in foreign markets. In some small European countries, this share reached over 50%. In Japan and the United States, shares are lower, reflecting their larger economies and lower dependency on exports/imports. Overall, a large share of jobs depends on foreign demand, because of direct links with trade partners or indirect ones when products reach final consumers through the exports of third countries.

By increasing specialisation in tasks, participation in GVCs affects the level of employment, but this impact has not been studied much. There is no simple relationship between employment growth and change in the use of goods or services that come from other countries. GVCs are expected to lead to job destruction and job creation. Several studies have shown that competition from Chinese imports led to a sharp decline in employment in the United States in the manufacturing sector in the early 2000s (Autor, Dorn and Hanson, 2015). However, competition from low-wage countries is only one aspect of participation in GVCs. The use of foreign inputs can also enable firms to develop new activities and therefore create jobs.

The development of GVCs affects the types of jobs in the economy. In most GVCs, there is a strong shift towards value being added by capital and high-skilled labour and away from low-skilled labour, even though the overall employment impact of GVCs remains disputed (Timmer et al., 2014).1 Developed countries have increasingly specialised in activities carried out by high-skilled workers. Emerging economies have specialised in capital and low-skilled activities.

Global value chains and inequalities within countries

The reference trade model (Hecksher-Ohlin model) predicts that in developed countries, wages of skilled workers should increase compared with wages of unskilled workers as demand for skilled labour increases and demand for low-skilled labour falls, and wage inequality should rise with trade. In developing countries that are well endowed with unskilled labour, on the other hand, wages of low-skilled workers should increase and wage inequality should decline.

However, there is little empirical evidence that trade is a major cause of increasing wage inequalities (OECD, 2011). Skills-biased technological change – change that favours skilled over unskilled workers – and other factors such as institutions may play a bigger role in explaining inequalities within countries.

The development of offshoring and increased import competition from low-wage countries has reawakened the debate on trade and inequality. Fragmentation of production has increased demand for skilled labour in both the North and the South: as the North sheds an activity that requires unskilled labour from its point of view, the South gains an activity that is skills-intensive from its point of view (Markusen, 2005; Feenstra and Hanson, 1996). By making some low-skilled workers redundant, offshoring lowers the wages of low-skilled workers or leads to their dismissal. This could explain the increase in inequalities in both developed and developing countries.

While offshoring can exacerbate inequalities by increasing the vulnerability of low-skilled workers, it can also enable low-skilled workers to abandon unproductive tasks and firms to increase specialisation in tasks. This can lead to productivity gains that at least partly accrue to low-skilled workers in terms of higher wages (Grossman and Rossi-Hansberg, 2008). This productivity effect explains why countries with a higher degree of backward participation in GVCs tend to have lower levels of wage inequality among their working population (Lopez Gonzalez, Kowalski and Achard, 2015).

Skill-biased technological change seems to affect inequalities more than offshoring. In the United States, import competition from low-wage countries appears to reduce employment of all occupation groups while technology has the largest negative effect on the middle category of routine, task-intensive occupations (Autor, Dorn and Hanson, 2015). In Europe, there is also evidence of a polarisation of employment: the share of low-paid and high-paid occupations has increased while the share of middle-paid occupations has decreased (Breemersch, Damijan and Konings, forthcoming). Technological change and to a lesser extent Chinese imports have contributed to this polarisation, with the increase in backward participation playing a lesser role. Another study finds that technological change and de-unionisation played a central role in explaining the wage distribution in the 1980s and 1990s, while offshoring became an important factor from the 1990s onwards (Firpo, Fortin, and Lemieux, 2012).

In developing and emerging economies, there is evidence that inequality has risen at the same time as globalisation (Pavcnik, 2011). However, very few studies have tried to assess the impact of offshoring or participation in GVCs on inequalities in these countries. These countries are exposed to offshoring both as purchasers of foreign intermediates and hosts of offshored activities.

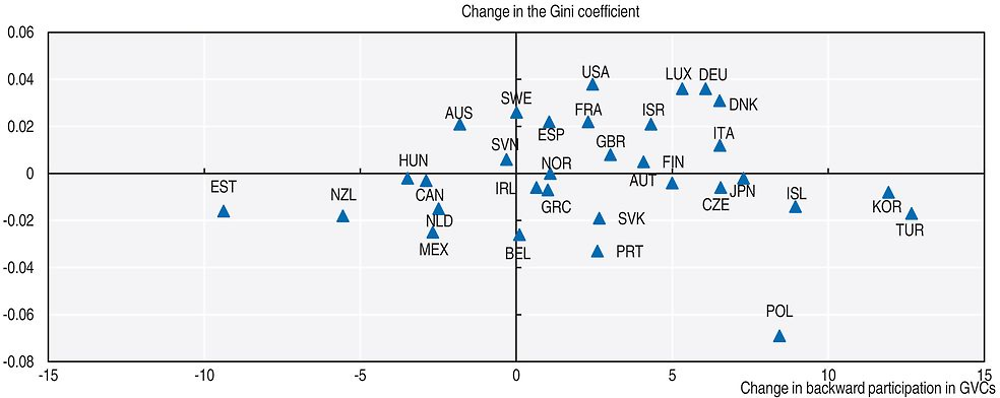

Simple correlations do not show any clear link between backward participation and inequalities. Since 2000, most OECD countries have developed offshoring, as measured by the foreign value added content of exports, with some of them experiencing a simultaneous rise in income inequalities and others a decline in inequalities (Figure 2.10).

Note: Gini coefficient for disposable income and for the working age population. Backward participation is measured by the foreign value added content of exports as a share of gross exports.

Source: OECD Trade in Value Added Database (TiVA), https://stats.oecd.org/index.aspx?queryid=66237; OECD Income Distribution Database, www.oecd.org/social/income-distribution-database.htm.

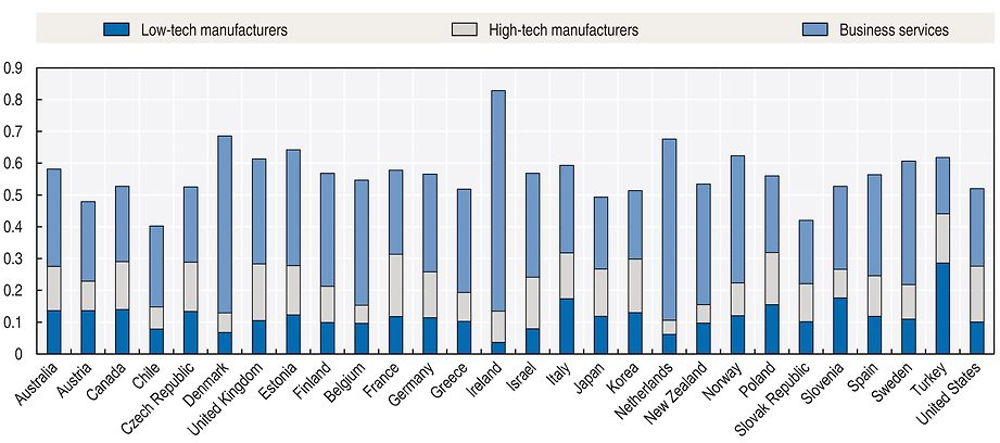

The use of foreign intermediate inputs is not more prevalent in low-tech manufacturing than in high-tech manufacturing and business services (Figure 2.11). This is also an indication that both low-skilled and high-skilled jobs can be concerned by offshoring, explaining why the increase in backward participation is weakly linked to changes in inequalities.

Note: Low technology manufactures are defined as sectors covering ISIC Rev.3 codes 15-22 and 36-37; business services include ISIC Rev.3 codes 50-74; and high technology manufactures include ISIC Rev.3 codes 24, 30, 32-33, 35.

Source: OECD (2016b), OECD Employment Outlook 2016, https://doi.org/10.1787/empl_outlook-2016-en.

Skills as a condition to make the most of global value chains

Skills help determine countries’ comparative advantages in global value chains

A workforce that is more skilled than in other countries is a source of comparative advantage that enables a country to specialise in high-skilled activities, according to the Heckscher-Ohlin model of international trade and empirical studies (Chor, 2010).

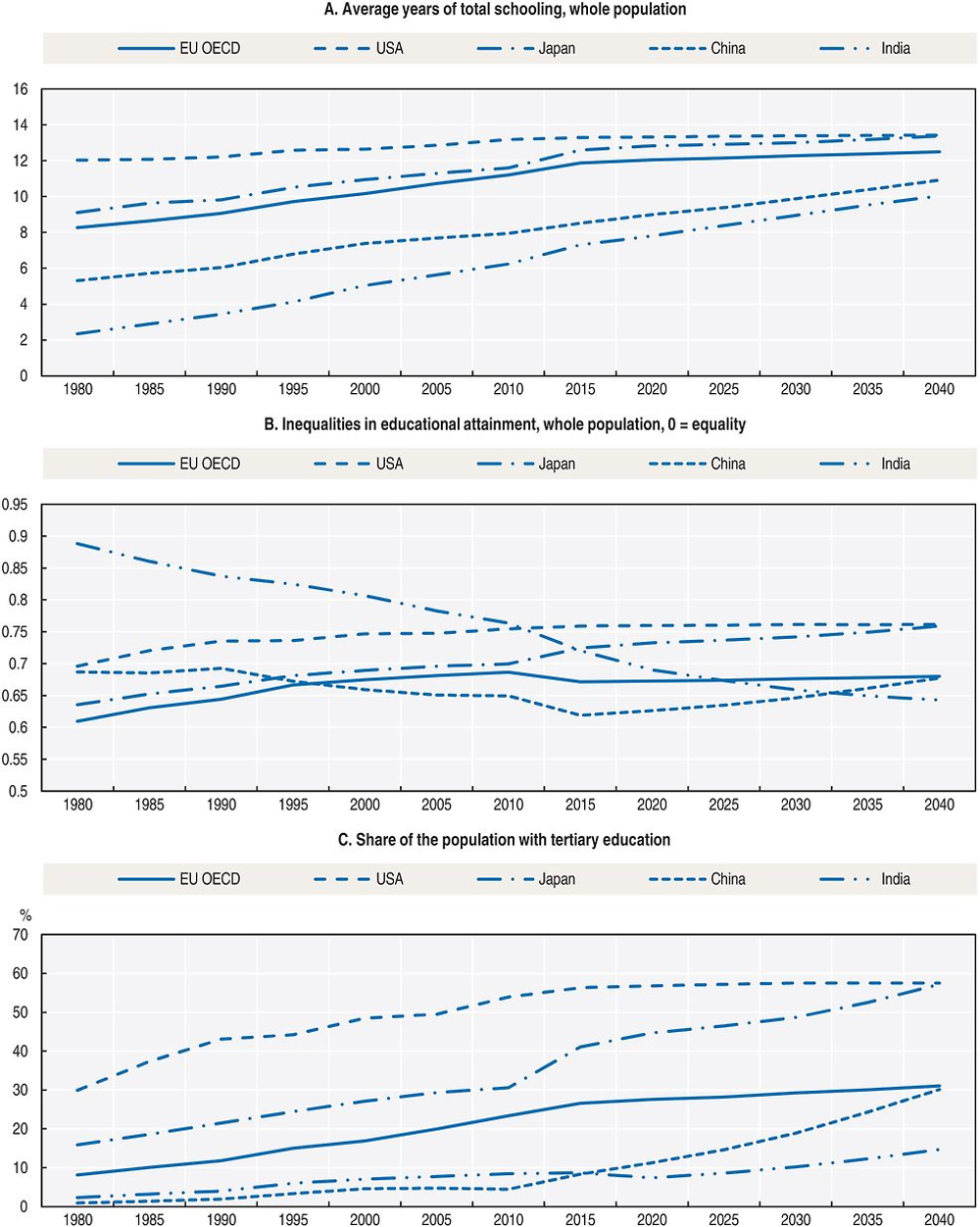

Educational attainment, the most common measure of skills, has increased in recent decades in most countries. The share of the population attaining tertiary education has more than doubled since the 1980s in many countries, including China and Japan, but remains the highest in OECD countries (Figure 2.12). At the same time, the gap between those with the lowest educational attainment and those with the highest has declined in countries where the gap was large to start with, such as India and – to a lesser extent – China, but has increased in several OECD countries, including Japan and the United States.

Note: Data for the whole population are for those aged above 15 until 2010 and estimates are given for the population 15-64 after 2010. Inequalities in educational attainment are measured by the coefficient of variation of average years of schooling.

Source: OECD calculations based on Barro and Lee (2013), “A new data set of educational attainment in the world, 1950-2010.”, Journal of Development Economics, Vol. 104.

These trends suggest that the comparative advantage of most OECD countries in terms of educated workers has decreased and will continue to do so, although educated workers will remain abundant in some of these countries, according to projections of educational attainment (Barro and Lee, 2013).

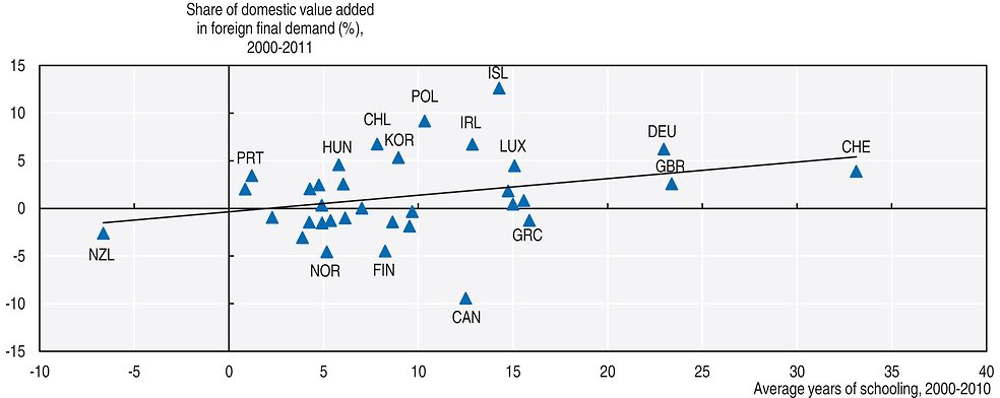

The evolution of participation in GVCs seems to be linked to the evolution of educational attainment. There is a positive correlation between the share of domestic value added in foreign final demand, which measures the extent to which a country reaches final consumers through its exports (forward participation), and the change in average educational attainment of the population (Figure 2.13).

Source: Barro and Lee (2013), “A new data set of educational attainment in the world, 1950-2010.” Journal of Development Economics, Vol. 104; OECD Trade in Value Added Database (TiVA), https://stats.oecd.org/index.aspx?queryid=66237.

However, educational attainment does not account for the skills and experience gained after initial education. In addition, as it does not directly measure the skills obtained at school, it does not reflect differences in the quality of education systems across countries. Some studies have corrected for differences between the quality of education systems by using available international mathematics and science test results as a proxy for skills (Hanushek and Woessmann, 2009). The Survey of Adult Skills, a product of the OECD Programme for International Assessment of Adult Competencies (PIAAC), directly measures some cognitive skills of the adult population and thereby accounts for the quality of education and other channels of skills development. However, it gives only limited information on the evolution of skills.

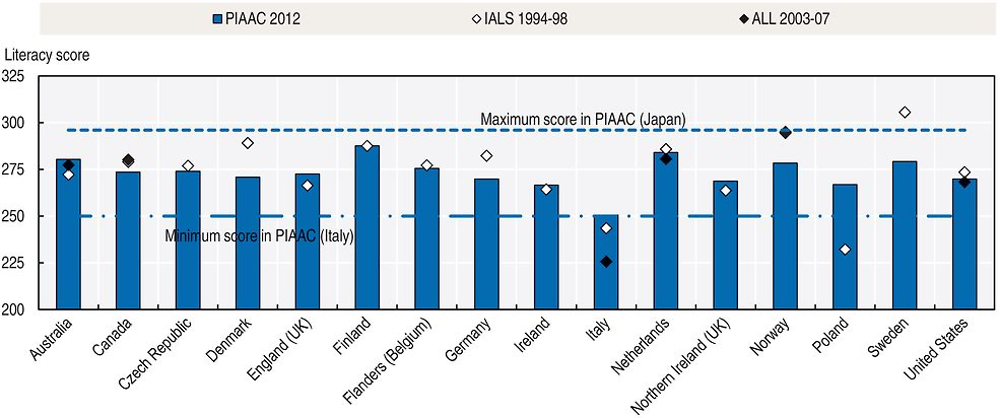

The trend in the development of skills is much less clear than educational attainment trends. Prior to the Survey of Adult Skills undertaken in 2011, two international assessments of adult skills were conducted in OECD countries: the International Adult Literacy Survey (IALS) between 1994 and 1998, and the Adult Literacy and Life Skills Survey (ALL) between 2003 and 2007. The Survey of Adult Skills was designed to be linked with IALS and ALL in the domain of literacy, and with ALL in the domain of numeracy, but differences in the implementation of the surveys may have affected the comparability of the data. Comparisons between IALS and PIAAC and between ALL and PIAAC show a mixed picture (Paccagnella, 2016; Figure 2.14).

Literacy skills appear to have declined in some countries (Canada, Denmark, Germany, Norway, Sweden), to have increased in few countries (Australia, Italy and Poland), and to have stagnated among another group (Belgium, the Czech Republic, Finland, Ireland, the Netherlands, the United Kingdom and the United States). The smallest changes have been observed among youth and the biggest among the oldest, which is consistent with the tapering off of the increase in educational attainment. In most countries, the skills of individuals with an upper secondary or tertiary level qualification have declined over the last decades – either because the quality of education has deteriorated or because higher educational attainment has been achieved by lowering skills acquisition requirements.

Note: Some caution is needed in interpreting the changes in proficiency observed between International Adult Literacy Survey (IALS), Adult Literacy and Life Skills Survey (ALL) and PIAAC for all countries, due to differences in the implementation of the surveys between countries and over time that may affect the comparability of the data from the different studies. There are specific concerns about the reliability of IALS and ALL data for Italy, England (UK), Northern Ireland (UK) and Poland.

Source: Paccagnella (2016), “Literacy and numeracy proficiency in IALS, ALL and PIAAC”, OECD Education Working Papers, No. 132, https://doi.org/10.1787/5jlpq7qglx5g-en.

Simple correlations at a country level can only provide a first glance at the links between skills and GVCs. Chapter 3 will investigate these links, based on the Survey of Adult Skills and the TiVA database. These links have never been analysed, as all past studies have looked at trade performance with exports defined in gross terms, not in value-added terms.

Skills are necessary to achieve productivity gains in global value chains

Skills are one of the factors that play a key role in ensuring that participation in GVCs translates into productivity gains. By enabling workers to absorb technology and knowledge, skills aid the diffusion of knowledge not only to firms that are part of GVCs but also to the rest of the economy (Morisson, Pietrobelli and Rabellotti, 2008; OECD, 2015c).

Skills are needed for the assimilation of technology, its adaptation and improvement, quality and inventory control, monitoring of productivity, co-ordination of different production stages, and for the process and product innovations related to basic research activity (Box 2.3). Specific skills are also needed to establish technology linkages among enterprises, with service suppliers, and with science and technology institutions.

Skills and technology combine to create non-tangible capital – usually called knowledge-based capital – that contributes to firms’ performance. Three types of knowledge-based capital assets are generally considered: computerised information (software and databases); innovative property (patents, copyrights, designs, trademarks); and economic competencies (including brand equity, firm-specific human capital, and organisational know-how that increases enterprise efficiency) (Corrado, Hulten and Sichel, 2005).

The relationship between knowledge-based capital and GVCs runs in both directions. Investing in knowledge-based capital may enhance firms’ ability to co-ordinate with and monitor suppliers; to integrate into production inputs of different quality or technological content; and to better match workers with tasks in production. Investing in knowledge-based capital can thus increase the benefits from backward participation in GVCs. In the other direction, participation in GVCs can stimulate investment in knowledge-based capital by providing access to greater varieties of inputs; reducing costs and thus freeing resources for investment; and enhancing the pace of reallocation within and across sectors, thanks to competition.

Such mutually reinforcing dynamics between knowledge-based capital investment and the use of foreign intermediates can nevertheless be dampened by the possibility that in-house production is downsized in favour of production elsewhere, to such an extent that investment in knowledge-based capital ultimately gets reduced at home.

A recent OECD empirical study investigates the links between two forms of knowledge-based capital – investment in software and organisational capabilities – and backward participation in GVCs (Marcolin, Le Mouel and Squicciarini, forthcoming). Investment in organisational capabilities captures the amount that industries devote to the compensation of workers whose occupations are intensive in managerial and organisational tasks (Squicciarini and Le Mouel, 2012; Le Mouel, Marcolin and Squicciarini, 2016).

This study shows that that the relationship between investment in organisational capabilities and software on the one hand and backward participation in GVCs on the other hand does indeed run in both directions, suggesting that investment in knowledge-based capital is complementary to relocating part of production offshore. Such a complementarity may arise from firms’ improved ability to adapt production processes and the labour force engaged in them, especially if offshored inputs are of different quality or technological content than domestic production. Greater offshoring of inputs, in turn, may further enhance investment in organisational capabilities and software through channels such as greater foreign competition on the input market or improved technological content of production.

Investing in R&D, skills and organisational know-how helps firms to reap the full benefits of new technologies and the fragmentation of production. These features of knowledge-based capital investment highlight the importance of policies sustaining the creation and absorption of knowledge in the economy, and of the need to co-ordinate innovation, skills and trade policies.

Source: Corrado, C., C. Hulten and D. Sichel (2005), “Measuring capital and technology: An expanded framework”, in Measuring Capital in the New Economy.

Le Mouel, M., L. Marcolin and M. Squicciarini (2016), “Investment in organisational capital: Methodology and panel estimates”, SPINTAN Working Paper, No. 2016/21.

Marcolin, L., M. Le Mouel and M. Squicciarini (forthcoming), “Investment in knowledge-based capital and backward linkages in global value chains”, OECD Science, Technology and Industry Working Papers.

Squicciarini, M. and M. Le Mouel (2012), “Defining and measuring investment in organisational capital: Using US microdata to develop a task-based approach”, OECD Science, Technology and Industry Working Papers, No. 2012/5, https://doi.org/10.1787/5k92n2t3045b-en.

The idea that international linkages can play a crucial role in accessing technological knowledge and enhancing learning and innovation is at the core of the concept of “economic upgrading”. This generally refers to the process of “moving up the value chain”, or moving from activities that generate little value added to those that are more complex and sophisticated (Figure 2.1).

A vast literature in the fields of international development, economic geography and sociology has illustrated the role of skills in participation in GVCs through activities that generate more value added. While this literature does not lead to a clear definition of economic upgrading and does not propose how to measure it, it supports the idea that skills can be a bolster against the risk that globalisation will reduce employment or increase inequalities. Overall, there is a need to adopt a clearer definition of economic upgrading in order to apply this concept using available databases.

At an industry or country level, economic upgrading can be defined as achieving productivity gains from participation in GVCs through the development of skills or innovation (Box 2.4). This definition implies that upgrading can be gauged by looking at both the generation of value added and the evolution of skills and technologies involved in the production process. It also implies that skills are at the core of upgrading. Some of the potential productivity gains at an industry level from participation in GVCs (Figure 2.8) come from the fact that countries that have increased participation in GVCs also had a high level of skills, proxied by the level of education, at the beginning of the period (Figure 2.15). This tentative estimate suggests that productivity gains are strongest when skills development and participation in GVCs go together.

The concept of economic upgrading has been mainly used in the context of developing economies, as the process according to which countries and firms that enter GVCs through low-skilled activities move to higher value added activities in production with improved technology, knowledge, and skills (e.g. Barrientos, Gereffi and Rossi, 2011). It is mainly used in the fields of international development, economic geography and sociology (Gereffi, 1994, 1999; Giuliani, Pietrobelli and Rabellotti, 2005; Kaplinsky, 2000; Humphrey and Schmitz, 2002; Pietrobelli and Rabellotti, 2007).

Upgrading is defined in opposition to other paths for achieving gains in value added based on the use of developing countries’ cheap labour (Rossi, 2013). Hence, upgrading has generally been defined as achieving a certain goal: increased value added, through specific means, more knowledge and skills. However, there is no consensus on what is meant by upgrading (Humphrey and Schmitz, 2002; Blažek, 2015). Some authors consider that upgrading can consist in moving into market niches that have entry barriers and are therefore isolated from pressures to maintain or increase income in the face of competition. Other authors have argued that channels other than skills and innovation should also be included, such as exposure to different managerial models and increased demand to meet certain standards (Ponte and Ewert, 2009).

In general, four types of upgrading channels are proposed:

-

Process upgrading is achieved through changes in the production process with the objective of making it more efficient. This can involve the substitution of capital to labour to achieve higher productivity through automation. Process upgrading is expected to reduce the demand for workers in routine tasks.

-

Product upgrading occurs where products with superior technological sophistication and quality are introduced, which often require more skills to make.

-

Functional upgrading is achieved when firms can provide competitive products or services in new segments or activities of a GVC that are associated with higher value added. It involves the development of skills and possibly the introduction of new skills to become competitive in new segments of the production process.

-

Chain upgrading is achieved when firms are able to participate in new GVCs that produce higher value-added products or services, often leveraging the knowledge and skill acquired in the current chain.

This classification may not match the complexity of concrete situations but it is useful to illustrate the role of skills and of different types of skills for maintaining competitiveness in GVCs.

The difficulty in defining economic upgrading leads to a corresponding difficulty in measuring it. A definition that matches firms’ dynamics cannot be applied at an industry or country level; upgrading at an industry or country level cannot be simply defined as the summing up of specific firms’ behaviour. The spillover effects to other firms have implications for performance of the industry and the country. For instance, upgrading in some firms may come at the cost of other domestic firms downgrading in GVCs. Conversely, firms that are linked to firms participating in GVCs, either directly or indirectly, may benefit from the diffusion of knowledge and technology. In addition, the performance of countries within GVCs depends on the dynamic process of firms, with new competitors entering GVCs and others quitting the market.

Increasing the domestic value-added content of exports has often been taken as a signal of upgrading. This is not always the case, however, as countries may rely on imports of inputs not because they are unable to produce these inputs but because they focus on parts of the production process where they have comparative advantages (Escaith, 2016). Upgrading may mean gaining overall competitiveness by offshoring non-core inputs.

Overall, if the concept of economic upgrading is to be used at a country level – for instance, as a policy objective – it could be understood more generally as achieving productivity gains from participation in GVCs through the development of skills or innovation.

Source: Barrientos, S., G. Gereffi and A. Rossi (2011), “Economic and Social Upgrading in Global Production Networks: A New Paradigm for a Changing World”, International Labour Review, Vol. 150, No. 3-4, pp. 319-340.

Blažek, J. (2015), “Towards a typology of repositioning strategies of GVC/GPN suppliers: the case of functional upgrading and downgrading”, Journal of Economic Geography, Vol. 16/4, pp. 849-869, https://doi.org/10.1093/jeg/lbv044.

Escaith, H. (2016), “Revisiting growth accounting from a trade in value-added perspective”, WTO Working Papers, ERSD-2016-01.

Gereffi, G. (1994), “The organization of buyer-driven global commodity chains: how US retailers shape overseas production networks”, in G. Gereffi and M. Korzeniewicz (Eds), Commodity Chains and Global Capitalism.

Gereffi, G. (1999), “International trade and industrial upgrading in the apparel commodity chain”, Journal of International Economics, Vol. 48, pp. 37-70.

Giuliani, E., C. Pietrobelli and R. Rabellotti (2005), “Upgrading in global value chains: lessons from Latin America clusters”, World Development, Vol. 33, pp. 549-573.

Humphrey, J. and H. Schmitz (2002), “How does insertion in global value chains affect upgrading industrial clusters?”, Regional Studies, Vol. 36, pp. 1017-1027.

Kaplinsky, R. (2000), “Globalisation and unequalisation: What can be learned from value chain analysis?”, Journal of Development Studies, Vol. 37, pp. 117-146.

Pietrobelli, C. and R. Rabellotti (2007), Upgrading to Compete. Global Value Chains, Clusters and SMEs in Latin America, Harvard University Press Cambridge, MA.

Ponte, S. and J. Ewert (2009), “Which way is ’’Up’’ in upgrading? Trajectories of change in the value chain for South African wine”, World Development, Vol. 37, pp. 1637-1650.

Rossi, A. (2013), “Does economic upgrading lead to social upgrading in global production networks? Evidence from Morocco”, World Development, Vol. 46, pp. 223-233.

Note: Gains in labour productivity growth coming from an increase from the 25th percentile to the 75th percentile of the distribution of the participation indicators channelled by skills. This corresponds to an increase of 15 percentage points for backward participation in terms of exports, 13 percentage points for backward participation in terms of final demand, and 12 percentage points for forward participation in terms of final demand.

The assessment comes from comparing the effect of participation in GVCs on productivity gains when the skill intensity of industries is accounted for or not. See Box 2.2.

Source: OECD calculations based on OECD Trade in Value Added Database (TiVA), https://stats.oecd.org/index.aspx?queryid=66237; and World Input-Output Database (WIOD), www.wiod.org/home.

Similarly, studies that trace the skills content of participation in GVCs show that skills influence future specialisation in GVCs. Countries with higher initial shares of high-skilled workers show a faster increase in the share of high-skilled workers in GVCs (Figure 2.16).

Note: Types of labour skills are classified on the basis of educational attainment levels as defined in the International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED): low-skilled (ISCED categories 1 and 2), medium-skilled (ISCED 3 and 4) and high-skilled (ISCED 5 and 6).

Source: Timmer et al. (2014), “Slicing up global value chains”, Journal of Economic Perspectives, Vol. 28/2.

Skills can connect local firms to multinationals

Many GVC activities are concentrated around multinationals, which themselves often concentrate skills and technology. As multinationals relocate activities to get access to skilled workers, a pool of workers with strong skills helps to attract FDI.

However, small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) also contribute to the development of GVCs. Data for a group of OECD countries show that the contribution of SMEs to the domestic value added of exports is above 50% in business services and above 40% in manufacturing in most countries of the group when their provision of intermediate goods and services to exporting firms is taken into account (OECD/World Bank, 2015).

SMEs tend to channel their value added for exports through large multinational firms rather than through other SMEs. On average, parent companies usually specialise in conception and design stages, and their affiliates and other local suppliers specialise in marketing and after-sales service (Antras and Yeaple, 2014). Nonetheless, some SMEs are also strongly involved in tasks at the higher end of the value chain, such as R&D, design and branding.

Exposure to GVCs can enable local firms to increase productivity by learning about advanced technologies or good organisational and managerial practices (Saia, Andrews and Albrizio, 2015). Lead firms require more and better inputs from local suppliers, creating a highly competitive environment, as well as incentives for local firms to meet higher standard requirements and opportunities to learn through imitation. Using foreign intermediate goods in production often also requires that firms adopt more sophisticated technology (Keller, 2004).

However, the gap in productivity growth between leading firms and other firms has increased over time, suggesting that the diffusion of knowledge from globally connected firms to leading national firms and from leading national firms to laggard firms has not operated well (Andrews, Criscuolo and Gal, 2015). One explanation is that low levels of skills have prevented highly productive national firms from catching up with globally connected firms. Even if workers in national firms have strong cognitive and technical skills, they may lack foreign language skills, cultural understanding, and knowledge of ways of doing business.

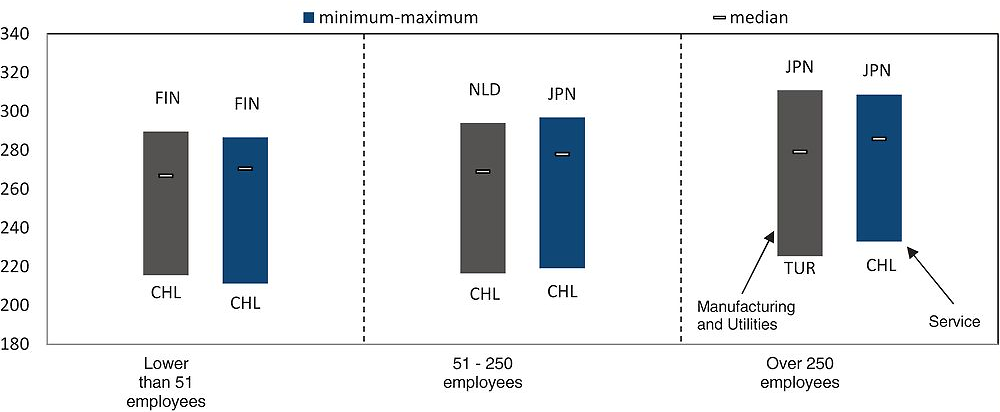

The skills of workers in SMEs are an important factor in the diffusion of knowledge to the whole economy. Foreign investors want face-to-face interactions and more responsive supply chains, so they prefer not to have to rely on importing goods and services where cost-effective scope exists for domestic suppliers to compete by upgrading skills and standards (OECD/World Bank, 2015). Some multinationals train local workers so they can use their knowledge-based assets, substituting for domestic educational and training systems. In developing countries, knowledge transfer occurs between headquarters and foreign affiliates (Javorcik, 2014). However, multinationals sometimes bring all the technology, management and know-how that they need, and choose not to rely on local know-how if it is too far from international standards (Baldwin and Lopez Gonzalez, 2013). The Survey of Adult Skills shows that workers in smaller firms have lower cognitive skills than those in larger firms, putting these workers at a higher risk of not meeting the skills requirements of multinationals (Figure 2.17).

Source: OECD calculations based on OECD Survey of Adult Skills (PIAAC) (2012, 2015), www.oecd.org/skills/piaac/publicdataandanalysis.

Relationships between multinationals and affiliates (or local suppliers) – and their respective bargaining powers – may influence the diffusion of knowledge and technology and thereby firms’ ability to gain a larger share of the value generated within GVCs (Gereffi, 1994 and 1999; Giuliani, 2005; Kaplinsky, 2000). Having the skills capacity to absorb new technologies can help SMEs to develop the types of relationships that foster the diffusion of knowledge.

What makes jobs vulnerable to globalisation and the implications for skills

The task content of jobs plays a key role in determining which jobs are favoured by globalisation, and which skills will maintain workers’ employability if offshoring exposes them to the risk of losing their jobs.

A first main dimension is the routine content of jobs. Evidence in the United States shows that demand for routine cognitive and manual tasks has declined since 1970, while the demand for non-routine analytic and interactive tasks has increased (Autor, Levy and Murnane, 2003).2 According to this study, substitution of routine by non-routine labour input is pervasive at all educational levels, but globalisation could be only one of several reasons for the shift of labour demand towards jobs intensive in non-routine tasks and skills. These authors consider that technology and automation are the main reasons for the collapse of jobs intensive in routine tasks. Other studies also find that the correlation between the routine content of jobs and the likelihood that they will be relocated offshore appears to be low (Blinder and Krueger, 2013). While routine tasks are easier to relocate than jobs requiring complex thinking, judgment and human interaction, a wide variety of complex tasks that involve high levels of skills and human judgment can also be relocated via telephone, fax or Internet.

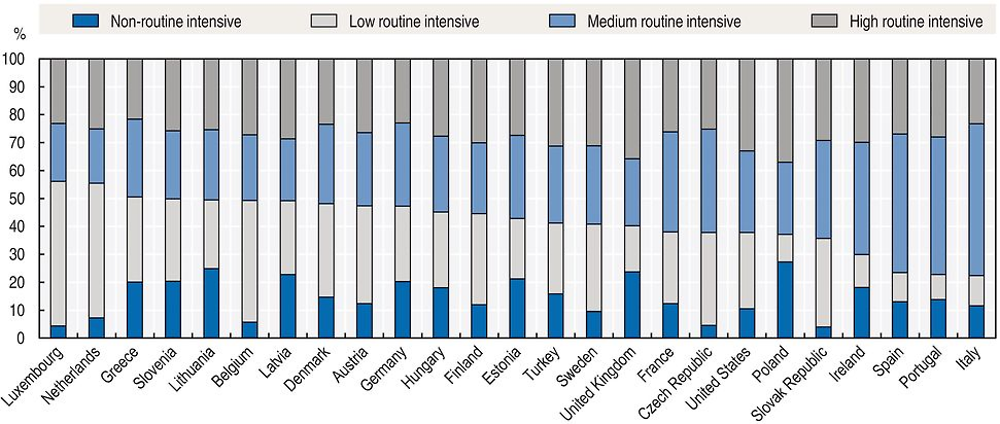

The Survey of Adult Skills reveals significant differences in the average proportion of employment accounted for by occupations of different routine intensity (Marcolin, Miroudot and Squicciarini, 2016; Figure 2.18). The share of non-routine and low routine-intensive workers ranges between about 55% in Luxembourg and 20% in Italy for the period 2000-11. The average share of workers employed in high routine-intensive occupations ranges between over 20% in Greece and 35% in the United Kingdom. Since the Survey of Adult Skills has only one point in time at the moment, the evolution of employment by routine content over time rests on the assumption that the routine content of each occupation has remained unchanged.3

Source: Marcolin, Miroudot and Squicciarini (2016), “Routine jobs, employment and technological innovation in global value chains”, OECD Science, Technology and Industry Working Papers, No. 2016/01. https://doi.org/10.1787/5jm5dcz2d26j-en.

The evidence based on the Survey of Adult Skills on the link between the routine content of jobs and their likelihood of being relocated offshore is not conclusive (Marcolin, Miroudot and Squicciarini, 2016). This is because interactions between the routine content of occupations, skills, technology, industry structure and trade are complex, which makes it difficult to identify “winners” and “losers” in a GVC context.

These results suggest that routine content is not the only characteristic that makes activities likely to be relocated. Others include the ability of a task to be performed in a remote location without substantial quality degradation (Acemoglu and Autor, 2011). It is possible that any job that does not need to be done in person (i.e. face-to-face) can ultimately be outsourced, regardless of whether its primary tasks are abstract, routine or manual (Blinder, 2009; Blinder and Krueger, 2013). The need for on-site work and the importance of decision taking may make jobs more difficult to relocate (Firpo, Fortin and Lemieux, 2012).

Note: The employment share in high routine intensity tasks is an average over the period 2000-11. Average workers’ skills are in 2012.

Source: OECD calculations based on OECD Survey of Adult Skills (PIAAC) (2012); www.oecd.org/skills/piaac/publicdataandanalysis; and Marcolin, Miroudot and Squicciarini (2016), “Routine jobs, employment and technological innovation in global value chains”, OECD Science, Technology and Industry Working Papers, No. 2016/01, https://doi.org/10.1787/5jm5dcz2d26j-en.

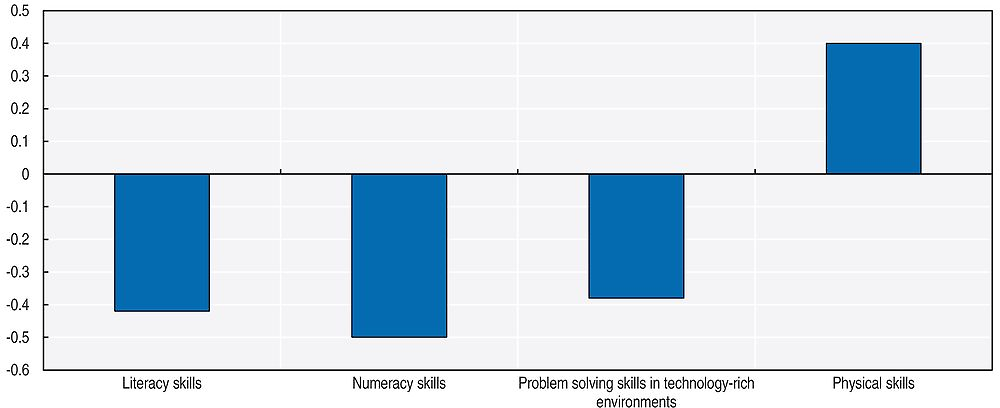

The possibility of offshoring certain tasks increases the importance of some skills and makes others obsolete. Tasks with a low degree of routine intensity and a high degree of abstract thinking may require stronger cognitive skills. Indeed, the OECD routine intensity index is negatively correlated with workers’ cognitive skills, as measured by the Survey of Adult Skills, but it is positively linked to physical skills (Figure 2.19). The strong managing, communicating and interacting skills that are required in decision-making also put workers less at risk of losing the domestic demand for their expertise.

Skills and the implications of global value chains for job quality

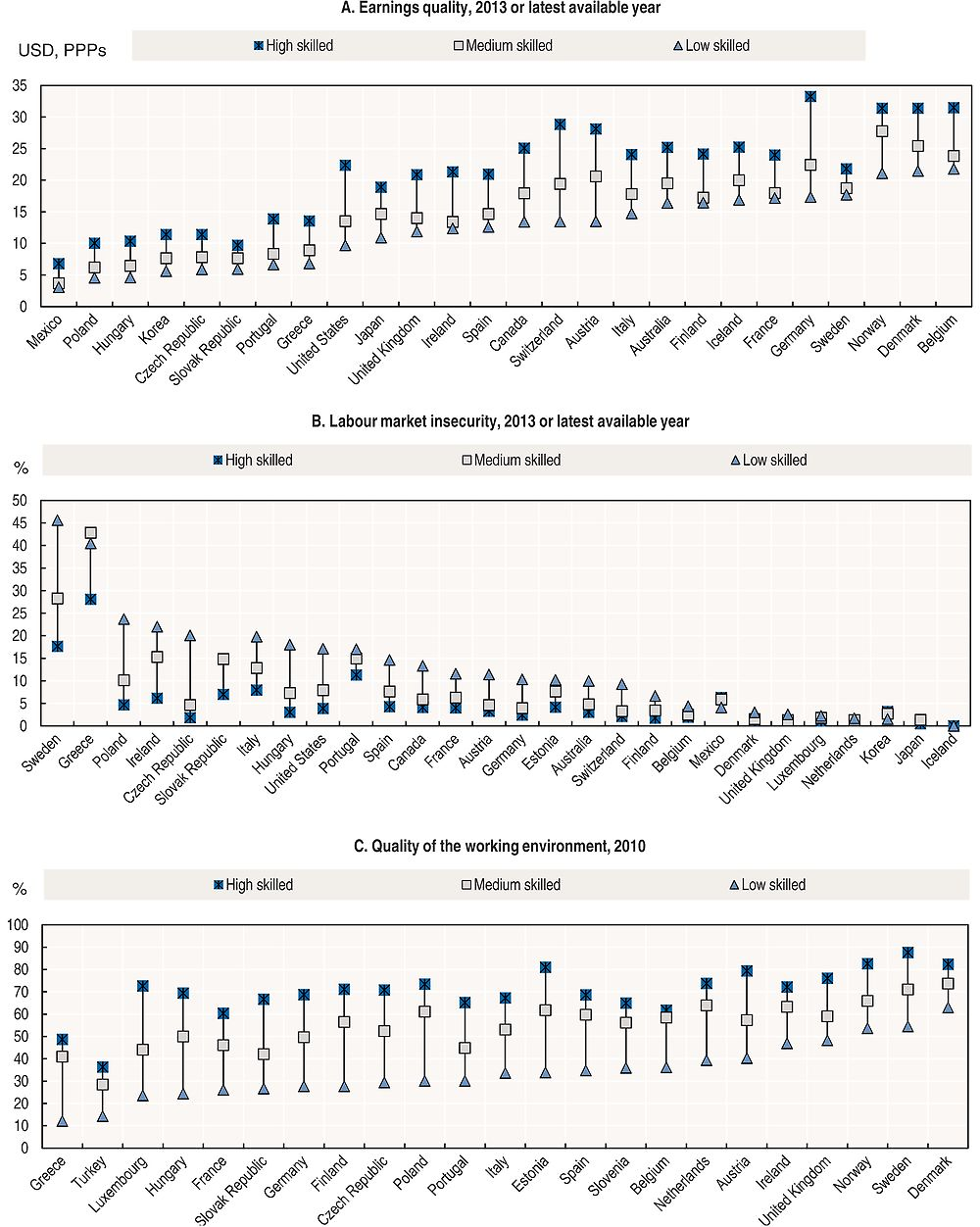

A key question about participation in GVCs and economic upgrading is whether they have improved quality of employment, or led to “social upgrading” – jobs with better wages, working conditions, social protection and rights (Barrientos, Gereffi, and Rossi, 2011; Rossi 2013). There has not been any comprehensive attempt to assess the extent of social upgrading, mainly because it is difficult to measure some of its aspects, such as working conditions and enabling rights. The OECD job quality framework assesses some of these aspects, however, by examining three dimensions:

-

Earnings quality: The level of earnings and their distribution across the workforce.

-

Labour market security: The risk of unemployment and the income support to which workers are entitled if unemployed.

-

Quality of the working environment: The nature and content of work performed, working-time arrangements and workplace relationships.

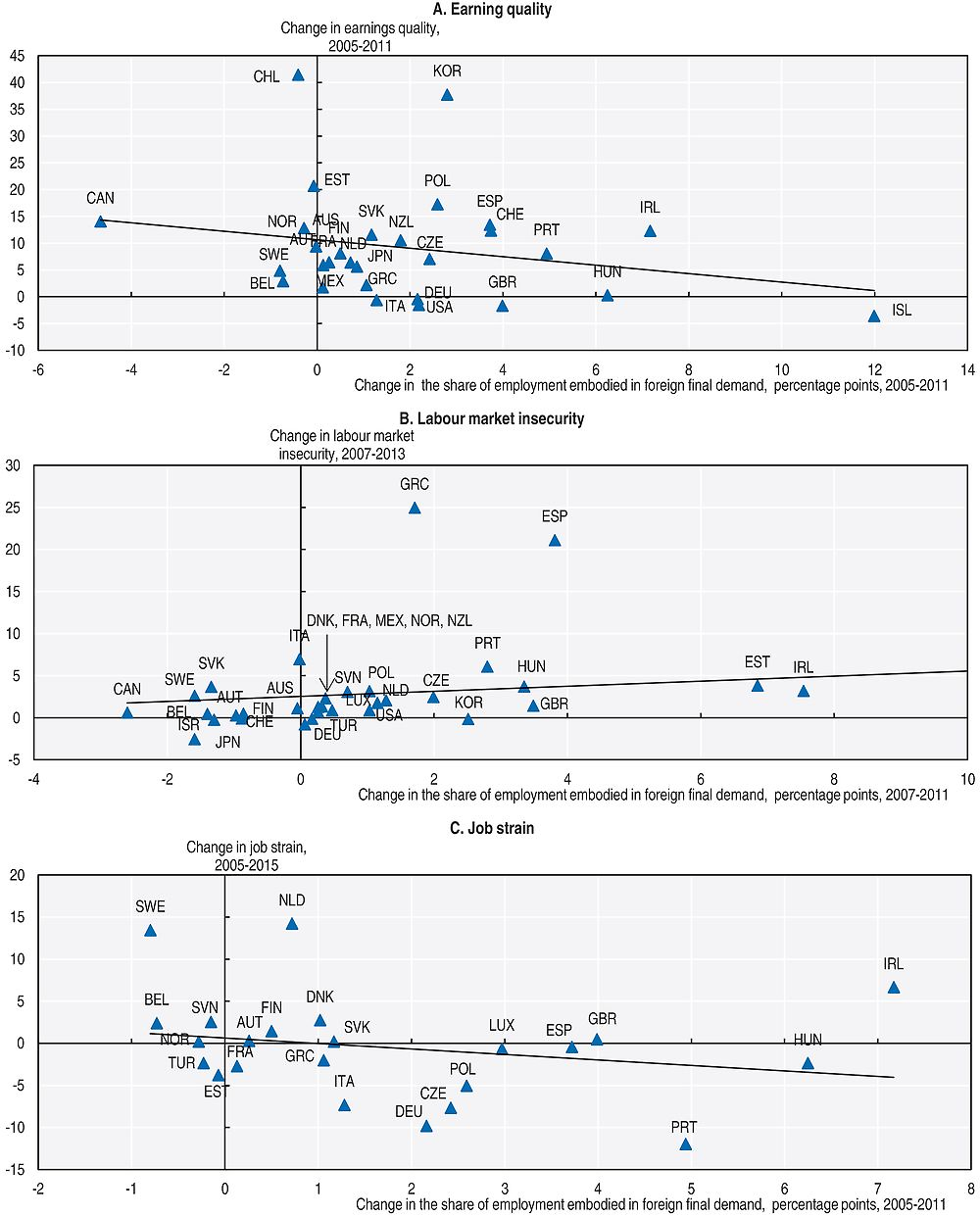

One way of gauging the impact of participation in GVCs on job quality is to consider the relationships between the change in the share of employment sustained by foreign final demand and changes in the various aspects of job quality (earnings, labour market security and working environment) over the same period (Figure 2.20). These relationships are weak, with earnings quality lowered the most by employment exposure to GVCs.

Source: OECD calculations based on the OECD Job Quality Database, https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=JOBQ; and OECD Trade in Value Added Database (TiVA), https://stats.oecd.org/index.aspx?queryid=66237.

Earnings quality was heavily affected by the fact that the jobs lost during the 2008 global economic crisis were predominantly low-paid, which led to an apparent increase in earnings quality on average during the crisis and the recovery period (OECD, 2016c). Countries where employment exposure to GVCs has increased may have seen a smaller reduction in low-paid jobs and an apparent smaller increase in earning quality.

Labour market insecurity has increased in most countries in the last decade but with no strong link with employment exposure to GVCs. Job strain, which occurs when job demands are high and workers’ control and resources are low, reflects the quality of the working environment. It has increased in some countries and decreased in others but has not increased more in countries in which the share of employment exposed to GVCs has increased. These links need to be interpreted with care as they cover a limited number of countries and do not demonstrate any causal relationship between job quality and participation in GVCs. In addition, institutional factors and country characteristics are major determinants of job quality.

Workers with the highest skills, as measured by level of education, enjoy the greatest job quality in all three dimensions – earnings, job security and working environment (Figure 2.21). In most countries, having a tertiary degree makes the most difference in terms of employment quality – particularly for earnings, but also for labour market security and working environment in many countries.

Note: The skill levels are based on the International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED, 1997). Low (skills) corresponds to less than upper secondary ISCED levels 0, 1, 2 and 3C short programmes. Medium (skills) corresponds to upper secondary and post-secondary non-tertiary ISCED levels 3A, 3B and 3C long programmes, and ISCED 4. High (skills) corresponds to tertiary ISCED levels 5A, 5B and 6.

Source: OECD Job Quality Database, https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=JOBQ.

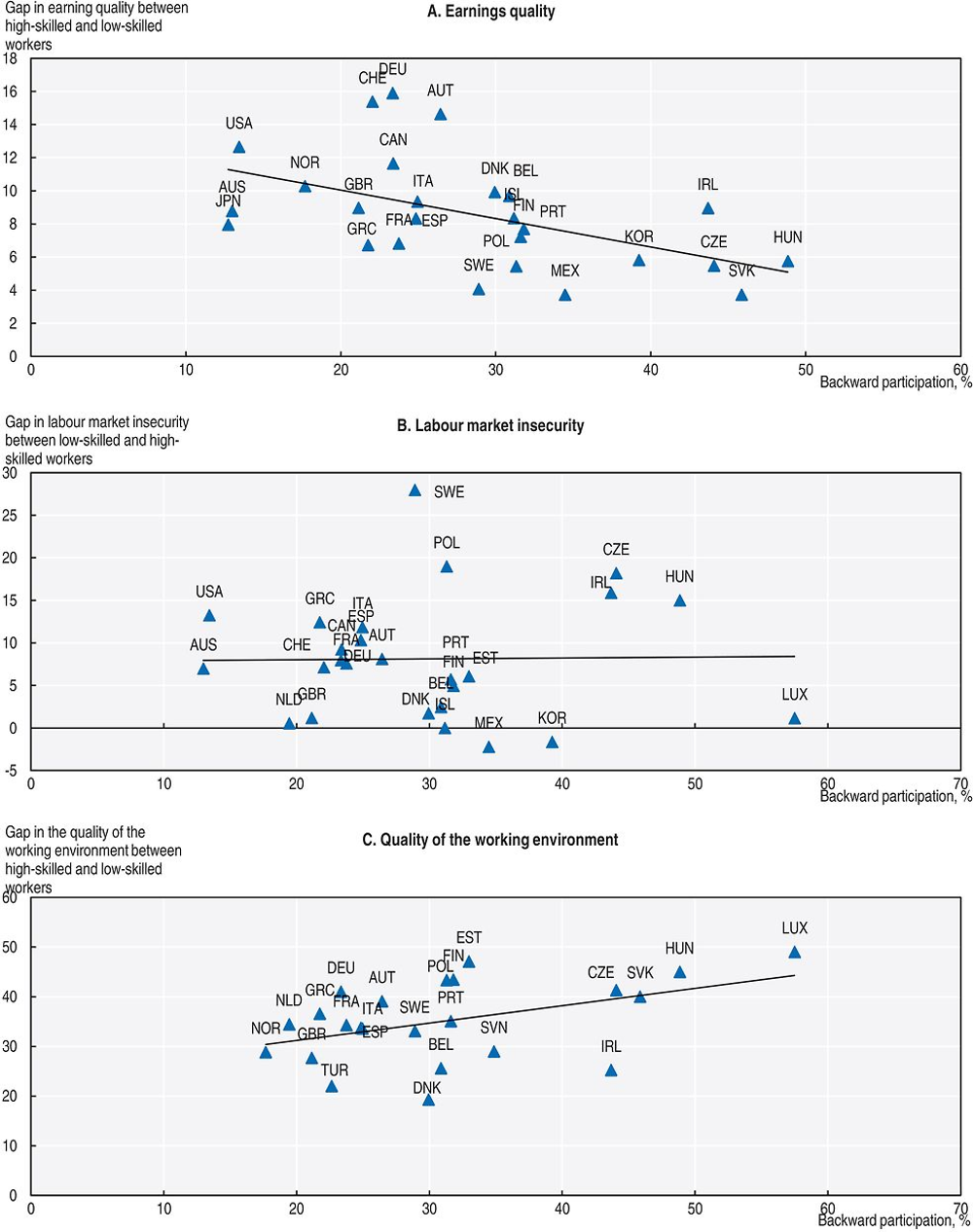

To determine whether skills can prevent participation in GVCs from lowering job quality, one can look at the relationship between the gap in job quality between low-skilled and high-skilled workers, on one hand, and participation in GVCs on the other hand. This gap varies greatly from country to country. The difference in earnings quality between low-skilled and high-skilled workers is large in Austria, Germany and Switzerland and much lower in France and Sweden. Labour market institutions contribute to these differences across countries, but participation in GVCs might be another explanation. The gap in job strain between low-skilled and high-skilled workers increases with the use of foreign intermediates, suggesting that participation in GVCs might create stronger work pressure for low-skilled workers (Figure 2.22). In contrast, the gap in earnings quality between low-skilled and high-skilled workers decreases with the use of foreign intermediates.

Source: OECD calculations based on OECD Job Quality Database, https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=JOBQ; and OECD Trade in Value Added database (TiVA), https://stats.oecd.org/index.aspx?queryid=66237.

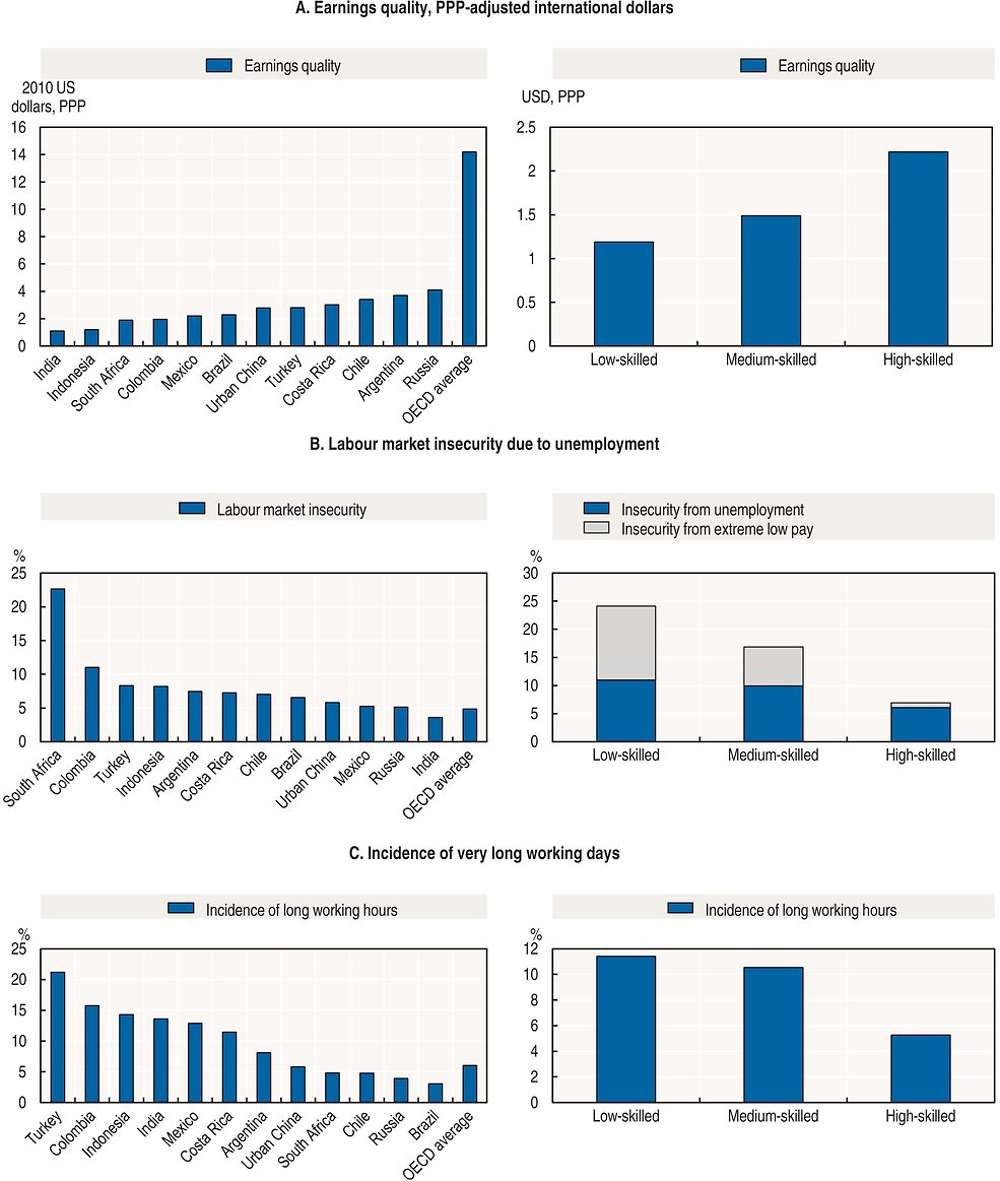

In developing and emerging countries exposed to globalisation, the evolution of wages, working conditions, social protection and workers’ rights has raised concerns. These concerns escalated when more than 1 100 people died in the 2013 collapse of the Rana Plaza, a commercial building in Dhaka, Bangladesh, that housed several factories making garments for retailers in developed countries. The OECD job quality framework clearly shows that job quality is lower in emerging economies than on average in OECD countries, in all three dimensions (OECD, 2015d) (Figure 2.23).

Note: Earnings quality is in 2010, labour market insecurity in 2010 to 2012 depending on countries and the incidence of very long working days in 2010 to 2011 depending on countries. Earnings quality is given for a medium inequality aversion.

The right-hand panels represent unweighted country averages of 12 sampled emerging economies (Argentina, Brazil, Chile, China, Colombia, Costa Rica, India, Indonesia, Mexico, the Russian Federation, South Africa, Turkey) except that China, India, Indonesia and the Russian Federation are excluded from the calculation of overall labour market insecurity due to missing information on social transfers.

The skill levels are based on the International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED, 1997). Low-skilled corresponds to less than upper secondary ISCED levels 0, 1, 2 and 3C short programmes. Medium-skilled corresponds to upper secondary and post-secondary non-tertiary ISCED levels 3A, 3B and 3C long programmes, and ISCED 4. High-skilled corresponds to tertiary ISCED levels 5A, 5B and 6.

For more information about the construction of these indicators, see the source document.

Source: OECD (2015d), OECD Employment Outlook 2015, https://doi.org/10.1787/empl_outlook-2015-en.

Educated workers in emerging countries are less exposed to the risk of low job quality (Figure 2.23). Workers with a high level of educational attainment enjoy not only higher earnings but also more earnings equality than less educated workers. They are much less exposed to labour market insecurity and the quality of their work environment is better.

Due to data limitations, it is not possible to link the evolution of job quality in emerging economies to their participation in GVCs. However, case studies of industries or firms illustrate how participation in GVCs can influence job quality and what role skills play in giving workers access to better jobs within GVCs. A study of 19 garment supplier firms in Morocco showed that increased value added in these firms did not lead to better working conditions for all workers (Rossi, 2013). Distinguishing between the various forms of economic upgrading (Box 2.4), the study showed that functional upgrading – a change in the activities of the firm (e.g. from manufacturing to product conception or packaging) – led to an increase in inequalities between workers. High-skilled workers benefited from training, as well as increased responsibilities and wages, while low-skilled workers, who were often on temporary contracts or in irregular jobs, faced pressure to work longer days and accept poorer working conditions.

Summary

Participation in GVCs poses both challenges and opportunities for countries. The main opportunity takes the form of higher productivity gains. New estimates in this chapter show that countries with the highest participation in GVCs experience higher productivity gains in industries that offer greater potential for fragmentation of the production process. Skills appear to play a key role in realising these productivity gains. For participation in GVCs to benefit to a maximum number of firms, including smaller ones, their workers need a level of skills high enough for the firm to realise the productivity gains offered by increased specialisation in tasks and exposure to more sophisticated inputs.

The main challenges posed by participation in GVCs are the risks of reduced employment and higher inequality. Competition from imports from China seems to have had a greater influence on employment than on inequality, because both low-skilled and high-skilled jobs are affected by the use of foreign intermediates. In addition, factors other than the development of GVCs appear to play a bigger role in explaining inequality. Findings on the impact of GVCs on employment and inequality are sometimes difficult to reconcile, however, and generally look at only one aspect of GVCs, the risk of offshoring.

Jobs that involve a higher proportion of routine tasks are more exposed to the risk of offshoring, whereas factors such as face-to-face contact, the need to be on-site and involvement in the decision process tend to make jobs less easy to offshore. Overall, investing in skills development is important to reduce workers’ exposure to offshoring.

Participation in GVCs can also reduce job quality, for instance by putting workers under greater pressure. Workers in emerging economies who have a low or medium level of education are particularly exposed to this risk, but workers in OECD countries are also affected. The gap in the quality of the working environment between workers with low and high levels of education tends to increase with as participation in GVCs increases in OECD countries.

In many respects, investing in skills can help countries seize the benefits of GVCs. A broad range of skills is needed, including skills to absorb new technologies, to communicate with other workers in the value chain, and to adapt to change. Skills can also directly shape countries’ positioning and specialisation in GVCs (see Chapter 3). While some OECD countries used to have a clear advantage because their workers had a higher level of education, this is becoming less and less the case. What makes the most difference now is the quality of education – the overall set of skills of the population, and how workers use these skills – rather than the overall level of education.

References

Acemoglu, D. and D.H. Autor (2011), “Skills, tasks and technologies: Implications for employment and earnings”, in O. Ashenfelter and D.E. Card (eds.), Handbook of Labor Economics, Elsevier, Amsterdam, Vol. 4B, pp. 1043-1171.

Aedo, C. et al. (2013), “From occupations to embedded skills: A cross-country comparison”, Policy Research Working Paper, No. 6560, The World Bank, Development Economics, Office of the Senior Vice President and Chief Economist, August 2013.

Amiti, M. and S.J. Wei (2006), “Service offshoring and productivity: Evidence from the United States”, NBER Working Papers, No. 11926, The National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge, MA.

Andrews, D., C. Criscuolo and P.N. Gal (2015), “Frontier firms, technology diffusion and public policy: Micro evidence from OECD countries”, OECD Productivity Working Papers, No. 2, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/5jrql2q2jj7b-en.

Antràs, P. and E. Rossi-Hansberg (2009), “Organizations and trade,” Annual Review of Economics, Vol. 1/1, pp. 43-64.

Antràs, P. and S.R Yeaple (2014), “Multinational firms and the structure of international trade”, in Handbook of International Economics, Vol. 4, pp. 55-130.

Autor, D.H., D. Dorn and G.H. Hanson (2015), “Untangling trade and technology: Evidence from local labour markets”, The Economic Journal, Vol. 125/584, pp. 621-646.

Autor, D.H., F. Levy and R.J. Murnane (2003), “The skill content of recent technological change: An Empirical exploration”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 118/4, pp. 1279-1333.

Baldwin, R. and J. Lopez Gonzalez (2013), “Supply-chain trade: A Portrait of global patterns and several testable hypotheses,” NBER Working Papers, No. 18957, The National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge, MA.

Baldwin, J. and B. Yan (2014), “Global value chains and the productivity of canadian manufacturing firms”, Economic Analysis Research Paper Series, No. 090, Statistics Canada, Analytical Studies Branch.