Chapter 1. Overview: Skills to seize the benefits of global value chains1

Over the last two decades, international patterns of production and trade have changed, leading to a new phase of globalisation. Each country’s ability to make the most of this new era, socially and economically, depends heavily on how it invests in the skills of its citizens. This chapter develops a scoreboard that measures the extent to which countries have been able to make the most of global value chains through the skills of their populations. It assesses jointly how countries have performed in recent years in terms of skills, global value chain development, and economic and social outcomes. This chapter offers an overview of the whole report. It examines how countries can ensure their performance within global value chains translates into better economic and social outcomes through effective, well-co-ordinated skills policies.

Since the 1990s, the world has entered a new phase of globalisation. Information and communication technology, trade liberalisation and lower transport costs have enabled firms and countries to fragment the production process into global value chains (GVCs): many products are now designed in one country and assembled in another country from parts often manufactured in several countries. To seize the benefits of GVCs, countries have to implement well-designed policies that foster the skills their populations need to thrive in this new era.

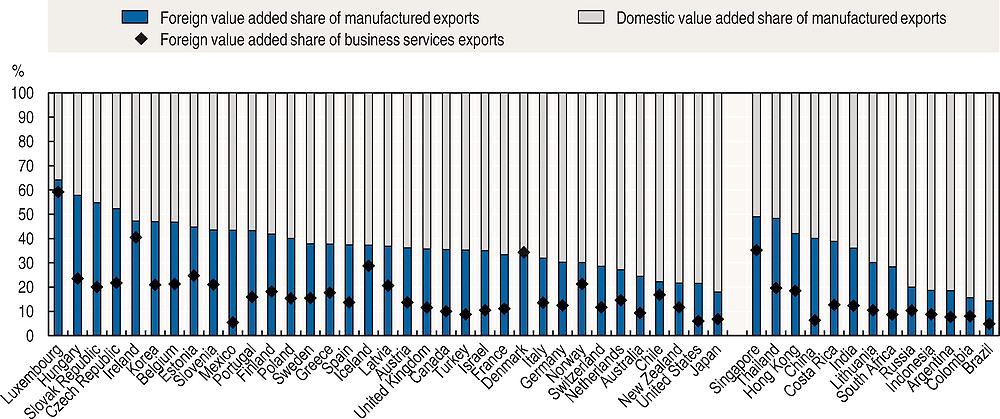

The scale of GVC deployment can be gauged by measuring trade in value-added terms instead of in gross terms, thus distinguishing between the value of exports that is added domestically and the value that is added abroad. Such measurement has been made possible through important recent advances by the OECD in co-operation with the WTO (OECD, 2013). On average, in OECD countries, close to 40% of the value of manufactured exports and 20% of the value of business services exports comes from abroad (Figure 1.1).

Source: OECD Trade in Value Added database (TiVA), https://stats.oecd.org/index.aspx?queryid=66237.

Global value chains present both opportunities and challenges for countries

GVCs give workers the opportunity to apply their skills all around the world without moving countries: an idea can be turned into a product more easily and those who are involved in production can all benefit from this idea. GVCs give firms the possibility of entering production processes they might be unable to develop alone. At the same time, the demand for some skills drops as activities are offshored, exposing workers to wage reductions or job losses in the short term. In the long term, however, offshoring enables firms to reorganise and achieve productivity gains that can lead to job creation. Overall, the costs and benefits of GVCs are complex. GVCs increase the interconnections between countries and thereby the uncertainty surrounding the demand for skills. A country’s competitiveness can be affected by skills policy changes occurring in its trading partners.

The impacts of GVCs on economies and societies are more diffuse and less controllable than those from the initial phase of globalisation (Baldwin, 2016). Economies used to be split into a sector exposed to international competition and a sheltered sector. Workers could enjoy higher wages in the exposed sector in return for accepting higher risks (e.g. unemployment risks), while governments could design specific policies for this sector. This distinction has now disappeared. Any job in any sector can be the next to benefit or suffer from globalisation: in many OECD countries, up to one-third of jobs in the business sector depend on foreign demand.

The rise of GVCs has prompted a backlash in public opinion in some countries. This negative reaction has sometimes focused on the leading role of multinationals and foreign direct investment. Multinationals can boost production and job creation in the host country by engaging local companies as suppliers, but they can also quickly relocate parts of the production process from country to country. This increases uncertainty about the demand for jobs and skills in each country, while making unco-ordinated policy response in each country less effective. Multinationals are often seen as responsible for offshoring jobs while contributing to the increase in top incomes.

The belief that rising trade integration can lead to unemployment, income losses and inequalities can lead to polarisation of politics (Autor et al., 2016). Given this risk, the challenge for countries is not only to seize the economic and social benefits of GVCs but also to explain their consequences better so that citizens can have informed views on the issue and vote accordingly.

The development of global value chains is uncertain

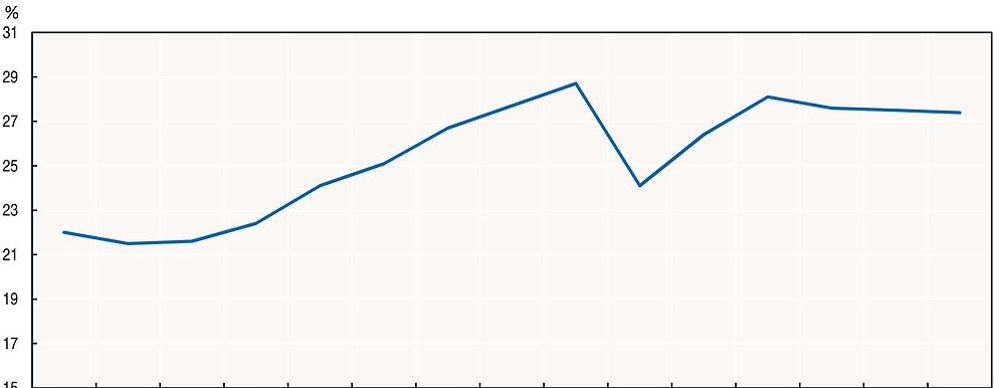

The trend towards GVCs, which had been increasing since the 1990s, dipped slightly in 2008 with the global trade slowdown and has since levelled off (Haugh et al., 2016; Timmer et al., 2016; Figure 1.2). Structural factors also seem to have contributed to the slowdown in the fragmentation of production, including greater protection of domestic production and, in some countries such as China, a substitution of imports by domestic goods as local production capabilities increase.

Note: Global value chain imports are all imports of goods and services needed in any stage of production of a final product.

Source: Timmer et al. (2016), “An Anatomy of the Global Trade Slowdown based on the WIOD 2016”, GGDC Research Memorandum, No. 162, University of Groningen.

The development of GVCs is uncertain. Digitalisation could enable further fragmentation of production. Services offer a large potential for fragmentation, which could also reinvigorate the development of GVCs (Baldwin, 2016). As some emerging economies, including China, move up GVCs, the internationalisation of production could expand to other countries, especially developing economies. On the other hand, technological innovations such as automation could stimulate renewed localisation of production in advanced countries, especially if policies enable this.

Investing in skills helps countries to seize the benefits of global value chains

This edition of the OECD Skills Outlook shows that through their skills and well-designed skills policies, countries can shape their capacity to seize the benefits of GVCs. As these policies are also vital to tackle other challenges, such as youth unemployment, investing in skills is a double-dividend strategy. Governments tend to respond to concerns about GVCs with policies outside the skills area, e.g. trade and industry, including policies that aim to stop the offshoring of activities. Such policies can be ineffective and less certain in terms of outcomes, and do not lead to a double dividend.

Skills can help countries to make the most of GVCs through various channels:

-

Skills are needed to realise the productivity gains offered by participation in GVCs and ensure these gains transfer to a broad range of firms, including small ones, and thereby benefit the whole economy.

-

Skills can protect workers against the potential negative impacts of GVCs in terms of job losses and lower job quality.

-

Skills are crucial for countries to specialise in the most technologically advanced manufacturing industries and in complex business services that are expected to lead to innovation, higher productivity and job creation.

More generally, investing in skills can ensure that all individuals understand the challenges and opportunities of globalisation, feel more confident in the future, shape their own careers, and cast informed votes.

OECD countries that appear to have benefited the most economically and/or socially from global value chains include Germany, Korea and Poland

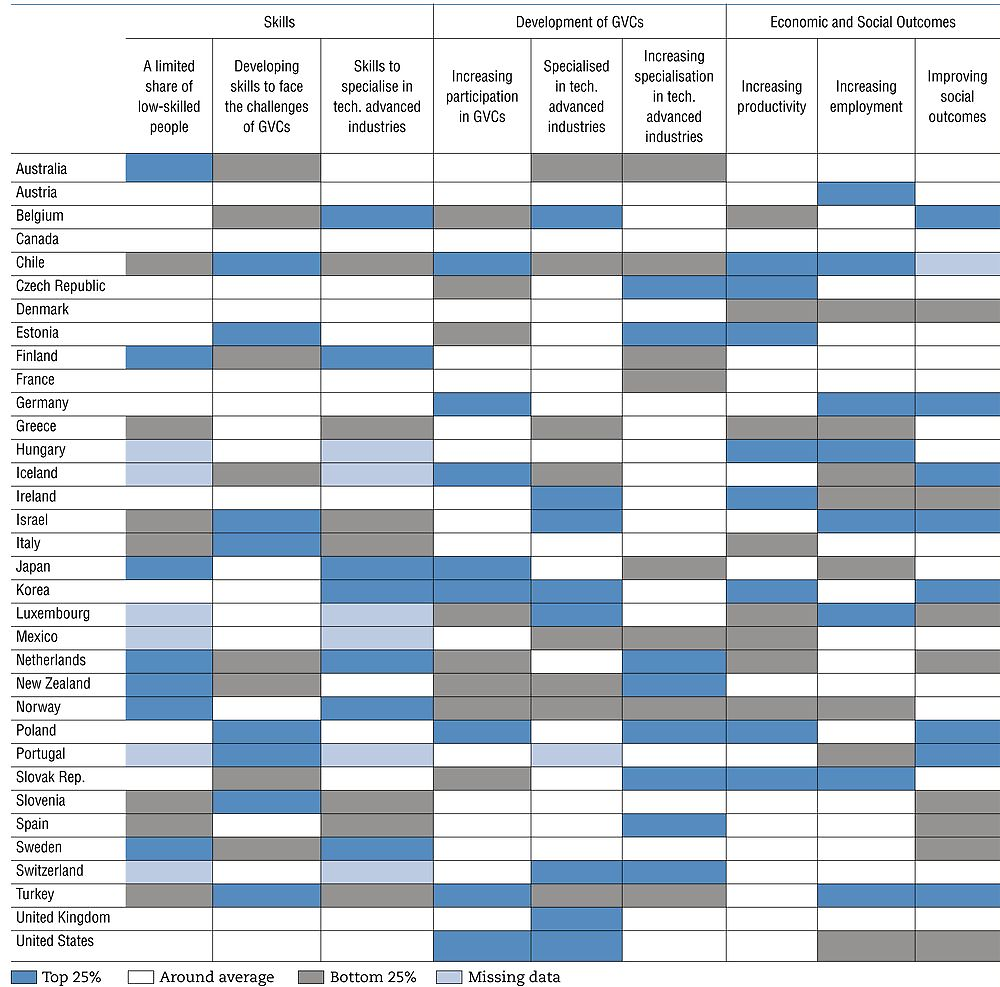

The extent to which countries have been able to make the most of GVCs through the skills of their populations can be summarised in a scoreboard (Table 1.1). The scoreboard gathers three blocks of information on i) countries’ skills; ii) countries’ participation in GVCs; and iii) countries’ economic and social outcomes based on the analysis developed in the whole publication (Box 1.1).

Note : Indicators are described in Box 1.1. The scoreboard shows for each sub-category, countries that perform in the top 25%, bottom 25%, and those around the OECD average. For instance, Finland is among the OECD countries that have the lowest share of low-skilled people, have not developed skills much to face the challenges of GVCs but have the skills to specialise in technologically advanced industries, and have not increased much their specialisation in technologically advanced industries. It performs around the average for the other sub-categories.

Source: OECD calculations based on the OECD Trade in Value Added database (TiVA), https://stats.oecd.org/index.aspx?queryid=66237; OECD Income Distribution Database, www.oecd.org/social/income-distribution-database.htm; OECD Job Quality Database, https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=JOBQ; OECD Productivity Database, http://stats.oecd.org/; OECD STAN STructural ANalysis Database, http://stats.oecd.org/; PISA database (2012), www.oecd.org/pisa/pisaproducts/pisa2012database-downloadabledata.htm; Survey of Adult Skills (PIAAC) (2012 and 2015), www.oecd.org/skills/piaac/publicdataandanalysis; and OECD (2016), Education at a Glance 2016: OECD Indicators, https://doi.org/10.1787/eag-2016-en.

The scoreboard presented in Table 1.1 aims to measure the extent to which countries have been able to make the most of GVCs through the skills of their populations. It assesses jointly how countries have performed in recent years in terms of skills, GVC development, and economic and social outcomes linked to participation in GVCs. It also gives information on the populations’ skills at the latest available date and the state of play of countries’ specialisation in technologically advanced industries.

Three main dimensions are considered, with sub-dimensions based on a group of indicators. All of them are taken from the analytical work presented in this edition of the OECD Skills Outlook.

The skills dimension attempts to capture some skills features that affect countries’ performance in GVCs and their capacity to make the most of GVCs. The following sub-categories are considered:

-

Do countries have a limited share of low-skilled people? To participate in GVCs, ensure that participation translates into productivity growth, and limit the risks of employment loss, increased inequality and poor job quality, countries need to minimise their shares of low-skilled adults (Chapter 2). To measure this aspect of skills, the scoreboard uses three indicators of the shares of adult low performers in different cognitive skills domains (literacy, numeracy and problem solving in technology-rich environment) based on the Survey of Adult Skills, a product of the Programme for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies (PIAAC).

-

Have countries developed skills to face the challenges of GVCs? To perform well in GVCs and ensure that participation in GVCs translates into good economic and social outcomes, countries need to invest in skills (Chapters 2and 3). To measure how skills have developed, the scoreboard uses three indicators of change in students’ scores in the OECD Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) (2003-15) and the growth rate of tertiary graduates (2000-15).

-

Do countries have the skills to specialise in technologically advanced industries? Technologically advanced industries require workers who have strong sets of skills and perform at the expected level (Chapter 3). To measure this aspect of skills, the scoreboard uses indicators of the skills (covered in the Survey of Adult Skills) of the adult population scoring in the top 25% of each country’s population, and indicators of the skills dispersion of adults with similar characteristics.

The global value chains dimension captures the extent to which countries have increased their participation in GVCs between 2000 and 2011, their specialisation in technologically advanced industries, as well as the state of play of this specialisation. It consists of three sub-dimensions:

-

How much have countries extended their participation in GVCs? An increase in participation in GVCs can lead to productivity growth, especially if countries have the relevant skills. The scoreboard uses several indicators to account for the development of the main two forms of participation (2000-11): i) importing foreign inputs for exports, or backward participation; and ii) producing inputs used in third countries’ exports, or forward participation. Participation in GVCs is assessed by looking at these two forms of participation as a share of countries’ exports or, alternatively, of foreign final demand (see Chapter 2).

-

To what extent are countries specialised in technologically advanced industries? Specialisation in technologically advanced industries is linked to value creation, innovation and productivity gains (Chapters 2and 3). It is measured by the indicator of revealed comparative advantage in technologically advanced industries in 2011.

-

How much have countries increased specialisation in technologically advanced sectors? This is measured by the growth rate of the revealed comparative advantage indicator mentioned above (2000-11).

The economic and social outcomes dimension captures how well countries have performed over the last 15 years in a variety of economic and social outcomes. It consists of three sub-dimensions:

-

To what extent have countries increased productivity? Increased participation in GVCs can lead to productivity gains via several channels, including the possibility to specialise in certain tasks, increased competition, and technology diffusion (Chapter 2). This economic outcome is measured by the growth rate of labour productivity (2000-15).

-

To what extent has employment increased? Participation in GVCs may affect employment, through both job destruction and job creation (Chapter 2). This is measured by looking at employment patterns in the business sector (2000-15), the share of youth who are neither employed nor in education or training (NEET, 2007-15), and the employment rate of workers older than the age of 54 (2000-15).

-

To what extent have social outcomes improved? Increased integration in GVCs can affect wages and inequalities, labour market security, and the quality of the working environment (Chapter 2). To measure these social outcomes, the scoreboard uses the growth rate of the Gini coefficient (2004-12) and the development of two aspects of job quality: labour market security (2007-13) and job strain (2005-15).

For each of the sub-dimensions of the scoreboard, a summary indicator is calculated and presented in Table 1.1. Each summary indicator aggregates the set of indicators presented above. Before the aggregation, each indicator was normalised in a way that implies a higher value and being among the “top 25%” reflects better performance. For this purpose, the inverse of several variables is considered in the ranking. The summary indicators for the nine sub-dimensions are calculated as a simple average of the indicators they contain.

Countries are ranked according to the nine summary indicators. The scoreboard shows countries in the bottom 25%, in the top 25% and those around the OECD average (in the remaining part of the distribution). A sharp threshold has been applied and therefore, some countries can be classified in one group (e.g. the bottom 25%) but be close to the other group (e.g. average).

The scoreboard shows that:

-

No country has achieved above-average outcomes in all the dimensions of the scoreboard.

-

Some countries, such as Germany, Korea and Poland, appear to have seized the benefits of GVCs by increasing their participation in GVCs, increasing their specialisation in technologically advanced industries, performing well in terms of the skills of their populations, and achieving good social or economic outcomes.

-

In contrast, countries such as the United States and to a lesser extent Denmark and Ireland have also increased their participation in GVCs but have seen weak economic or social development, which may be partly explained by insufficient skills.

-

Considering their populations’ high skills, Finland and Japan could benefit more from participation in GVCs by deepening their specialisation in technologically advanced industries, and by increasing productivity and employment. Policies outside the skills domain may be preventing them from realising these gains.

-

While Chile and Turkey have increased their participation in GVCs a lot and have developed the skills needed to face the challenges of GVCs, they could do more to develop the skills needed in technologically advanced industries and increase their specialisation in this area.

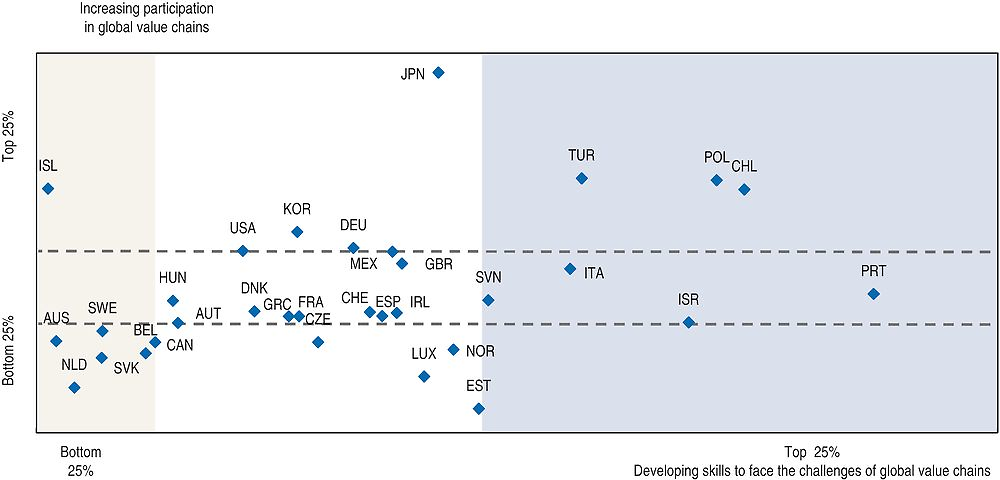

To some extent, countries that have improved the skills of their population the most have also increased their participation in GVCs more than average (Chile, Poland and Turkey, and to some extent Japan) (Figure 1.3). However, in a group of countries, increased participation in GVCs has not been accompanied by a similar development in skills (Korea and Germany). As these countries have good levels of skills already, it may not represent an issue at present, but it could dampen their capacity to fully realise the benefits of their participation in GVCs in the future.

Note: The figure shows the scoreboard indicators capturing the development of participation in GVCs over 2000-11 and the evolution of skills (Box 1.1). Countries in the upper part of the figure are among the top 25% that have increased their participation in GVCs the most while those in the lower part of the figure are among the bottom 25% that have increased their participation in GVCs the least. Countries in the right-hand side of the figure are among the top 25% that have increased their skills the most while those in the left-hand side of the figure are among the bottom 25% that have increased their skills the least. Countries in the middle of the figure are around the average.

Source: OECD calculations based on the OECD Trade in Value Added database (TiVA), https://stats.oecd.org/index.aspx?queryid=66237; PISA database (2012), www.oecd.org/pisa/pisaproducts/pisa2012database-downloadabledata.htm; and OECD (2016), Education at a Glance 2016: OECD Indicators, https://doi.org/10.1787/eag-2016-en.

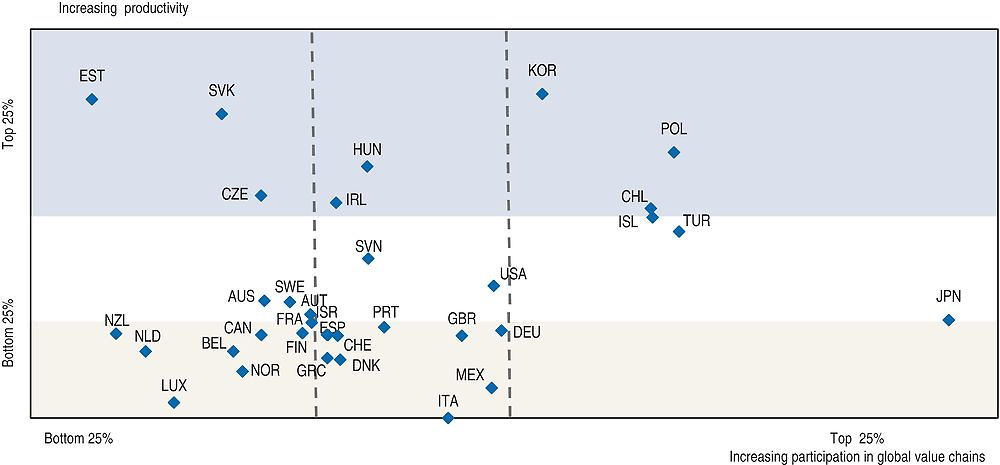

Global value chains improve productivity, especially when participation goes hand in hand with skills

GVCs offer firms and countries opportunities to increase their productivity by specialising in tasks in which they perform better. Participation in GVCs can also increase competition among firms, which can stimulate the adoption of new ways of organising work and production. Finally, the use of more sophisticated imported intermediate products can boost productivity by facilitating the diffusion of new technologies. Over the last 15 years, the OECD countries with the highest increases in participation in GVCs experienced average or above-average productivity gains (Figure 1.4). Some countries increased both their participation in GVCs and their productivity more than others (Chile, Korea and Poland).

Note: The figure shows the scoreboard indicators capturing the development of participation in GVCs over 2000-11 and the evolution of productivity, see Box 1.1. Countries in the upper part of the figure are among the top 25% that have increased productivity the most while those in the lower part of the figure are among the bottom 25% that have increased productivity the least. Countries in the right-hand side of the figure are among the top 25% that have increased their participation in GVCs the most while those in the left-hand side of the figure are among the bottom 25% that have increased their participation in GVCs the least. Countries in the middle of the figure are around the average.

Source: OECD calculations based on OECD Trade in Value Added database (TiVA), https://stats.oecd.org/index.aspx?queryid=66237; and OECD Productivity Database, http://stats.oecd.org/.

According to new OECD estimates, countries with the largest increase in participation in GVCs over the period 1995-2011 have benefited from additional annual industry labour productivity growth ranging from 0.8 percentage points in industries that offer the smallest potential for fragmentation of production to 2.2 percentage points in those with the highest potential (Chapter 2).

Investing in skills ensures that participation in GVCs increases productivity, because firms need workers who can learn from new technologies and who benefit from the exposure to more sophisticated goods and new work organisation. However, productivity gains will not spread to the whole economy if small firms do not have the capacity to absorb new technology and production modes, or if they remain disconnected from GVCs. Skills indicators based on the Survey of Adult Skills show that workers in small firms have lower levels of skills than those in larger firms.

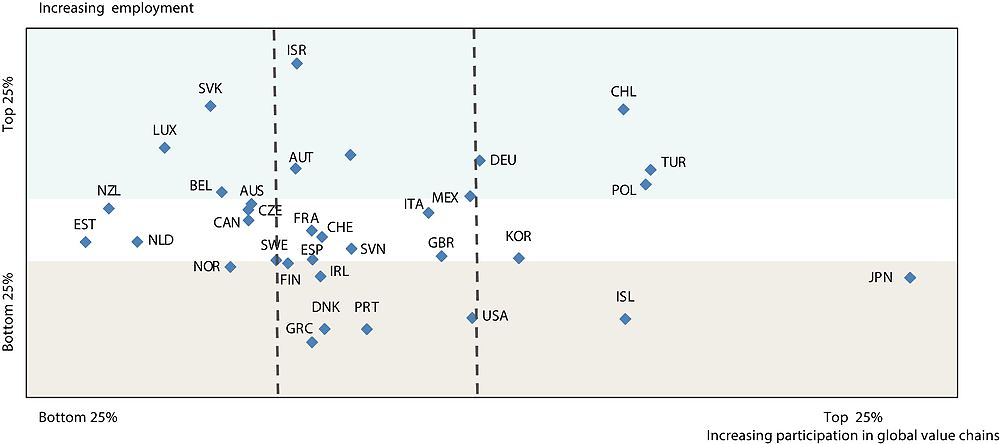

Skills act as a bolster against the potential negative impact of global value chains on social outcomes

Linking more firms to GVCs can help spread productivity gains to the whole economy. It also means that more firms, and therefore more workers, are exposed to the impacts – positive and negative – of GVCs on employment and wages.

The implications of participation in GVCs for employment remain to be fully understood. Recent studies show that import competition from low-cost countries such as China has led to a fall in employment, especially in the manufacturing sector (Autor, Dorn and Hanson, 2015). However, competition from low-cost countries is only one aspect of GVCs. OECD countries import intermediates from high-tech manufacturing industries and business services but also export these products to other countries, which creates new employment opportunities. Among countries that have increased their participation in GVCs the most, some countries had the largest employment growth (Chile, Germany, Turkey and Poland), while others had the lowest (Iceland, Japan and the United States) (Figure 1.5).

Note: The figure shows the scoreboard indicators capturing changes in participation in GVCs over 2000-11 and the evolution of employment, see Box 1.1. Countries in the upper part of the figure are among the top 25% that have increased employment the most while those in the lower part of the figure are among the bottom 25% that have increased employment the least. Countries in the right-hand side of the figure are among the top 25% that have increased their participation in GVCs the most while those in the left-hand side of the figure are among the bottom 25% that have increased their participation in GVCs the least. Countries in the middle of the figure are around the average.

Source: OECD calculations based on OECD Trade in Value Added database (TiVA), https://stats.oecd.org/index.aspx?queryid=66237; OECD Employment database, www.oecd.org/employment/emp/onlineoecdemploymentdatabase.htm; and OECD STAN STructural ANalysis Database, http://stats.oecd.org/.

The impact of participation in GVCs on inequalities within countries also remains debated. Most studies conclude that skill-biased technological change and institutions are the major determinants of inequalities while competition from low-cost countries plays a smaller role. But GVCs create inequalities of opportunity: some high-skilled workers and those with jobs involving non-routine tasks can apply their skills all around the world while those whose jobs can be offshored face a rise in competition.

Countries can reduce workers’ exposure to the risk of offshoring by investing in the development of skills. What people do on the job, and thereby the type of skills they develop, strongly influences the exposure of their jobs to the risk of offshoring. Jobs that involve face-to-face interactions, the need to be on-site, and decision making are less easy to offshore. When workers have the necessary skills, they can help their jobs evolve or find it easier to adapt to changing needs.

Participation in GVCs can also affect job quality, by intensifying competition, exposing workers to new standards and work organisation settings, raising the demand for quality and shortening production times. In all countries, more educated workers enjoy higher job quality than low-educated ones. But the gap in job strain between low-educated and high-educated workers is larger in countries that participate more in GVCs (Estonia, Hungary, Poland and Slovenia). Investing in skills along with increasing participation in GVCs is particularly important in developing economies that tend to be at the lower end of value chains, where working conditions are more often poor.

Countries increasingly compete through their skills

A more educated labour force has enabled many OECD countries to specialise in technologically advanced industries, in both the manufacturing and services sectors. Countries’ specialisation within GVCs can be gauged via their revealed comparative advantages (RCAs), which indicate the extent to which a country receives a bigger part of its overall GVC income from adding value in the production of an industry than other countries. Over the last 15 years, OECD countries have been increasingly specialising in services and in high-tech manufacturing industries.

However, the comparative advantage that many OECD countries used to derive from the higher education level of their population is shrinking as tertiary education develops in many developing and emerging economies. By 2040, the share of the population with tertiary education in China will approximate the share in European OECD countries but will remain below the share in Japan and the United States (Barro and Lee, 2013). By 2040, around two-thirds of young people with tertiary education will come from non-OECD G20 countries (OECD, 2015).

At the same time, it has become less costly for firms to tap into the international pool of skills. With the fragmentation of production, firms can use workers from abroad without moving the whole production chain. This has increased competition between highly educated individuals.

Countries and individuals increasingly compete through their skills, not only through their level of education. Countries can gain comparative advantages in technologically advanced industries through the characteristics of their skills, how well these skills match industry requirements, and their overall capacity to make the most of these skills pools.

Cognitive skills and readiness to learn are crucial for performance in global value chains…

Skills in all their diversity are a fundamental determinant of economic and social success. While there is no broad agreement on a typology of skills, skills that matter for job performance can be considered as a continuum, with some skills having mostly a cognitive component (e.g. literacy and numeracy), some mostly linked to personality traits (e.g. conscientiousness and emotional stability), and others arising from the interaction and combination of these two components (e.g. communicating, managing and self-organising).

The Survey of Adult Skills provides a broad range of information on the skills composition of the population and the tasks performed on the job, which can be used to measure some of the skills that have been identified as important for workers’ and firms’ performance. This survey directly assesses three domains of cognitive skills (numeracy, literacy and problem solving in technology-rich environments) through administered tests. In addition, the large set of information on frequency of performance of several tasks at work and on attitudes towards learning sheds light on six other skills domains: information and communications technologies (ICT) skills; management and communication skills; self-organisation skills; marketing and accounting skills; science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) skills; and readiness to learn.

Analysis of this information shows that workers’ cognitive skills and readiness to learn play a fundamental role in international integration as workers need them to share and assimilate new knowledge, allowing countries to participate and grow in evolving markets. Literacy, numeracy, problem solving in technology-rich environments and readiness to learn all tend to be stronger where exports are stronger, even more so when exports are expressed in value added terms, with cognitive skills having the strongest links.

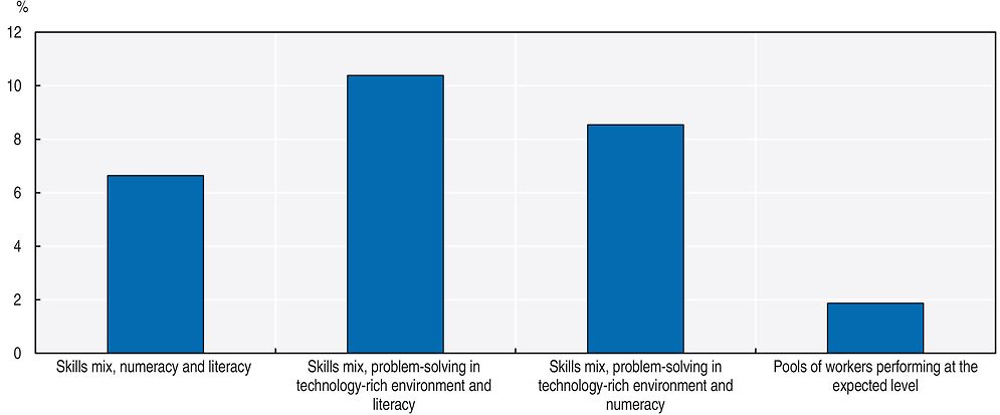

… but countries have to equip their populations with strong skills mixes

Strong cognitive skills are not enough on their own to achieve good performance in GVCs and to specialise in technologically advanced industries. Industries involve the performance of several types of tasks, but all require social and emotional skills as well as cognitive skills. To succeed in an internationally competitive environment, countries and industries need skills in addition to those related to their domain of specialisation.

To perform well in an industry, workers need to have the right mix of skills. According to new OECD estimates, differences in countries’ capacity to endow the population with the right skills mix can lead to differences in relative exports of around 8% between two countries with average differences in their skills mixes (Figure 1.6) and of up to 60% between two countries with large differences. In particular, several high-tech manufacturing industries and complex business services are found to require strong skills in problem solving in technology-rich environments, and those with these skills need to also have strong numeracy and literacy skills. The countries with the strongest alignment of the mix of skills with these industries’ skills requirements are Canada, Estonia, Israel, Korea and Sweden.

Note: Change in exports (in value added terms) in an industry relative to another industry (which has one standard deviation lower industry intensity) resulting from a marginal change (one standard deviation) in each of the four countries’ skills characteristics. When countries with large differences in their skills characteristics are considered, these effects reach 60% for the skills mix and 10% for pools of workers performing at the expected level. These effects come from empirical work developed in Chapter 3.

Source: OECD calculations based on the Survey of Adult Skills (PIAAC) (2012, 2015), www.oecd.org/skills/piaac/publicdataandanalysis; OECD Trade in Value Added database (TiVA), https://stats.oecd.org/index.aspx?queryid=66237; OECD (Annual National Accounts, SNA93, http://stats.oecd.org/; OECD STAN STructural ANalysis Database, http://stats.oecd.org/; Mayer and Zignago (2011), “Notes on CEPII’s distances measures: the GeoDist Database”, CEPII Working Paper 2011-25; World Input-Output Database (WIOD), www.wiod.org/home.

Equipping individuals with strong skills mixes is not the same as having groups of individuals who are strong in just one type of skill. Even those who are specialised in one area, for instance in STEM skills, need to have complementary skills.

Specialisation in technologically advanced industries requires pools of workers who perform at the expected level

High-tech manufacturing and complex business service industries require all workers to perform at the expected level, because they involve long sequences of tasks and poor performance in any task can greatly reduce the value of output (Chapter 3). In contrast, industries that are less technologically sophisticated generally involve shorter sequences of tasks. Poor performance in some tasks can be mitigated by superior performance in others.

Pools of workers performing at the expected level (or reliable workers) emerge in countries in which individuals with similar characteristics – including educational attainment – have similar skills. In such cases, employers who have selected applicants on the basis of observable characteristics do not receive any unwelcome surprises from workers’ actual skills. According to new OECD estimates, for instance, Japan – which has a small skills dispersion of individuals with similar characteristics – can export in value-added terms around 20% more than Chile and 10% more than Spain in high-tech manufacturing and complex business service industries relative to other industries. Differences in relative exports between two countries with average differences in their skills dispersion reach 2% (Figure 1.6).

As OECD countries progressively lose the comparative advantage that they receive from the higher level of education of their populations, they can seek to gain comparative advantages from their capacity to provide pools of reliable workers:

-

The Czech Republic, Japan, the Netherlands and the Slovak Republic show a small dispersion of the skills of individuals with similar characteristics, helping them to provide pools of workers performing at the expected level.

-

Canada, Chile, Poland, Slovenia and Turkey show a large dispersion of the skills of individuals with similar characteristics. To maintain or increase their comparative advantages, these countries need to lower the skills dispersion of individuals with similar characteristics. They could achieve this goal through policies fostering equal quality across similar educational programmes, training workers who do not perform at the expected level and better signalling workers’ skills.

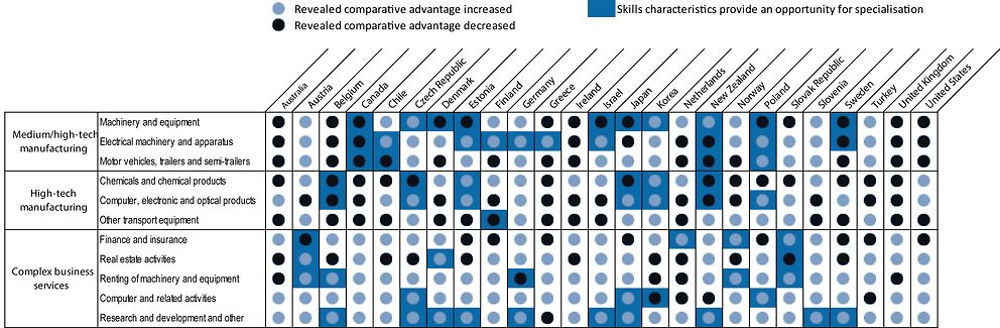

Countries whose skills characteristics appear to be best aligned with technologically advanced industries’ requirements include the Czech Republic, Estonia, Japan, Korea and New Zealand

Countries can shape their specialisation in GVCs through their skills characteristics, by aligning these characteristics with industries’ skills requirements. Policies to support a specific industry can be inefficient if countries’ skills do not match the skills requirements of the industry, and by misallocating skills they can lower the comparative advantage countries have in other industries.

Many OECD countries strive to excel in technologically advanced sectors, but the specialisation pathways for some countries would require more effort and take longer depending on their current production structure, skills characteristics and other countries’ comparative advantages in these industries. Table 1.2 shows whether countries have increased or decreased their specialisation in technologically advanced industries and whether their skills characteristics offer them opportunities to specialise in these industries:

-

Some countries (the Czech Republic, Estonia, Japan, Korea and New Zealand) have increased their specialisation in technologically advanced industries, and in most cases, this is supported by their skills characteristics (e.g. Poland in some medium high-tech manufacturing industries and Korea in high-tech manufacturing industries).

-

Some other countries’ specialisation is not supported by their skills characteristics (e.g. the United Kingdom and the United States). To maintain their comparative advantages, these countries need to improve the skills mixes of their populations to better align them with the skills requirements of technologically advanced industries.

-

Finally, some countries need to improve the alignment of their skills characteristics with technologically advanced industries’ requirements if they want to increase their specialisation in these industries. Canada, Chile, Greece, Israel, Poland, Slovenia and Turkey need to achieve a stronger homogeneity in the skills of workers with similar characteristics. Australia and Ireland need to better align the skills mix of their workers with the skills requirements of these industries.

Note: Revealed comparative advantages show the extent to which a country is specialised in a certain industry within GVCs (or receives more income from its exports in this industry than other countries). The dots in the table show whether countries have increased or decreased their revealed comparative advantages over the period 2000-11. Opportunities for specialisation are the results of empirical work developed in Chapter 3. Countries have an opportunity to specialise in an industry if there is a good alignment of countries’ skills characteristics with the skills requirements of this industry. Several characteristics of skills shape countries’ specialisation in GVCs. The extent to which these characteristics are aligned with each industry’s skills requirement can be consolidated into one measure showing the specialisation opportunities of each country in each industry.

Source: OECD calculations based on OECD Trade in Value Added database (TiVA), https://stats.oecd.org/index.aspx?queryid=66237; and the Survey of Adult Skills (PIAAC) (2012 and 2015), www.oecd.org/skills/piaac/publicdataandanalysis.

Countries need to improve the quality of their education and training systems

Countries can gain comparative advantages from their populations’ skills, and thereby from the quality of their education systems. They can improve their competitiveness in GVCs by teaching all students strong cognitive and soft skills at the same time, and by developing multidisciplinarity. This requires innovative teaching strategies and flexibility in the curriculum choice in tertiary education while maintaining a strong focus on developing cognitive skills.

Countries can also do more to achieve uniform quality of education across schools and programmes. In many countries (including Chile and France), learning outcomes are strongly tied to social background. Countries in which social background influences education outcomes at the age of 15 the least (Estonia, Finland, Japan, Korea and Norway) are also those in which adults with similar characteristics have similar skills, leading to good signals to employers about workers’ actual skills. The education funding system, including the way education resources are allocated, plays a vital role for achieving homogeneity in quality of otherwise similar education programmes. This is an area where many countries have to make progress.

Strong co-operation between education and training institutions and the private sector is crucial

Countries can gain comparative advantages in industries if countries’ skills characteristics are closely aligned with industries’ skills requirements. To improve this alignment, education and training systems need to co-operate with the private sector, for example through vocational education and training with a strong work-based learning component; local initiatives to link education institutions to the private sector; and policies to foster interaction between the private sector, universities and research institutions. Such co‐operation would also make young people feel better prepared and more confident of their capacity to manage their careers in an uncertain environment if they are more exposed to the world of work during their study.

As large parts of global trade are organised around supply chains of multinationals (UNCTAD, 2013), it is important for education and training systems to work with these companies to understand their skills needs. Such links can be developed by encouraging internship and work-based learning, and enabling representatives from firms involved in GVCs to share their experiences with tertiary students. Developing courses in English can also facilitate the recruitment of young graduates by firms involved in GVCs.

Countries need to work on various fronts to encourage adult education and training

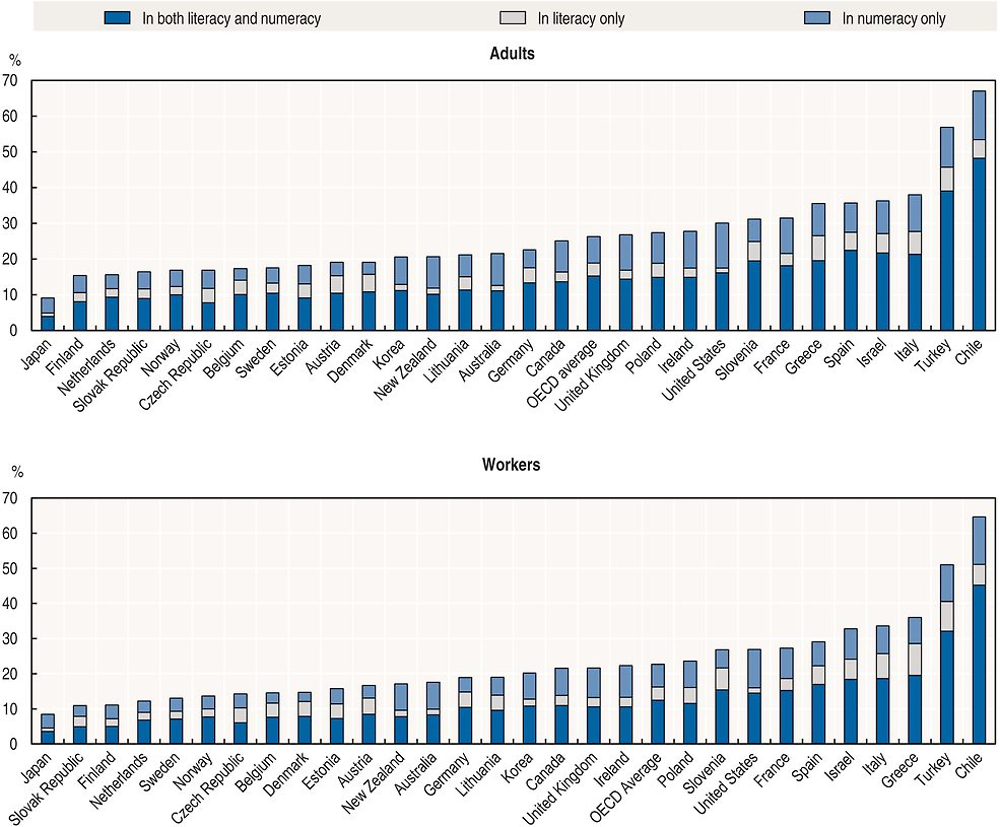

Countries with a low share of low-skilled workers are not necessarily less at risk of offshoring, which depends on a country’s position in GVCs: some countries might offshore mainly low-skilled activities while countries higher on the value chain might offshore activities performed by skilled workers. In either case, however, workers find it easier to make the transition to a new job if they have the ability to manage this transition and to learn the necessary new skills. Countries differ in their share of low-skilled adults (Figure 1.7). Those with a high share of low-skilled workers (Chile, Greece and Turkey) will have to make significant efforts to implement appropriate education and training policies if they want to specialise in more technologically advanced activities without unemployment expanding.

Note: Low performers are defined as those who score at or below Level 1 in either literacy or numeracy according to the Survey of Adult Skills. Chile, Greece, Israel, New Zealand, Slovenia and Turkey: Year of reference 2015. All other countries: Year of reference 2012. Data for Belgium refer only to Flanders and data for the United Kingdom refer to England and Northern Ireland jointly.

Source: OECD calculations based on the Survey of Adult Skills (PIAAC) (2012 and 2015), www.oecd.org/skills/piaac/publicdataandanalysis.

For workers at risk of displacement, labour market programmes and effective, modern public employment services can ease the transition to new jobs. In the long term, however, policies are needed that prepare workers for a world in which skills requirements are evolving fast, by facilitating the development of skills at various phases of life.

Retraining low-skilled workers is one of the biggest challenges that many countries face. Countries have to find efficient ways to develop skills but also to break the vicious cycle between being low-skilled and not participating in adult learning. In all countries, those who are the most skilled or who are making the most intensive use of their skills are those who benefit the most from adult training programmes.

The obstacles to adult education need to be removed, by better designing the tax system to provide stronger learning incentives, easing access to formal education for adults, improving the recognition of skills acquired after initial education, and working with trade partners to develop on-the-job training opportunities and enhance flexibility in the sharing of time between work and training.

Countries can co-operate better on the design and funding of education and training programmes…

GVCs benefit from the internationalisation of tertiary education. Students from abroad with a domestic diploma might be well placed, for instance, to work in multinationals and develop activities in their countries of origin. GVCs can also stimulate the internationalisation of education by giving students opportunities to apply their skills in many countries, not only in the country where they graduated.

As GVCs spread, it becomes more complex to allocate the costs and benefits of the internationalisation of tertiary education. Developing and emerging economies see a large share of their most talented youth leave to study abroad. If they do not return, part of the initial education investment is lost. Developed economies, for their part, lose some investment in education – typically in specific vocational skills – when activities are offshored. In terms of benefits, the opportunity to study abroad may increase the incentive to invest in education at home in developing economies and those who have left may develop activities with their countries of origin through GVCs. Developed economies can enlarge the domestic pool by attracting international students.

Co-operation in the design of education programmes is a way to ensure quality, maintain knowledge in the development of skills that have been offshored but could be brought back to the domestic market tomorrow, and raise the skills in developing economies. Countries could seek agreements to co-design some education and training and consider new financing arrangements that better reflect the distribution of benefits and costs coming from the internationalisation of tertiary education and of the production process. An agreement can take various forms, from consultation on the skills needs implied by offshoring and on how they can be met, to a more formal agreement in which the costs of some education programmes can be shared and offshoring countries can help design education programmes in countries to which activities are offshored.

… and improve recognition of skills acquired informally or abroad

Improving the recognition of skills acquired abroad would help attract foreign students and foreign workers who can contribute to research, innovation and performance in an international context. And expanding recognition of skills acquired informally would help workers exposed to the risks of offshoring gain further qualifications and adapt to changing needs. In addition, it would give employers clearer signals about workers’ actual skills. This can contribute to strong performance in GVCs as workers have to perform at the expected level in order not to weaken the production chain.

Policies can ensure better use of the skills pool

Developing the right skills is crucial for countries to seize the benefits of GVCs, but for these skills to materialise into good performance within GVCs, they need to be used effectively. This means ensuring that skills are allocated to the right firms and industries, and using skills effectively within firms.

Within firms, management policies can ensure good use of skills and enhance productivity. The level of education of both managers and non-managers is strongly linked to better management practices, so it is important to ensure that education and training systems develop strong mixes of skills, including entrepreneurship and management skills. Entrepreneurship education can foster awareness and knowledge of best practices for both employers and workers.

Non-compete clauses influence workers’ capacities to apply their skills elsewhere. Under these clauses, employees agree not to use information learned on the job for a limited period of time. While protecting employers’ intangible investments, these clauses restrict workers’ mobility, can be an obstacle to structural adjustments, and limit the spread of knowledge. The use of non-compete clauses in OECD countries needs to be better understood, and it is vital to ensure they are not abused.

The allocation of skills to firms also depends on employment protection legislation. It needs to provide flexibility to firms but also security to workers, so that they have incentives to develop firm-specific skills as well as income security. Non-standard forms of employment have not yet developed much in industries exposed to GVCs but their progress needs to be monitored. While providing flexibility to firms and opportunities to workers, they may lead to underinvestment in skills development, which is crucial for maintaining international competitiveness.

A whole-of-government approach is needed

Within governments, the risks of misalignment between policies and international competitiveness objectives are large. GVCs and trade pertain to ministries with their own sets of policies outside the skills area, while the ministries in charge of most skills policies – education, research and labour – generally focus on national employment and innovation. To make the most of GVCs, a whole-of-government approach is needed.

There are two main types of misalignments of policies. Trade, tax or competition policies aimed at fostering performance in some industries may not be supported by policies ensuring that these industries have the skills they need. Or skills policies may be undermined by employment protection legislation, non-compete clauses or migration policies. For instance, education and training policies may not be able to boost performance in GVCs if migration policies prevent countries from building links with other countries in innovation networks, or if strict employment protection legislation and non-compete clause regulations hinder the needed structural changes.

To make sure that policies across government are aligned in favour of improving performance in GVCs, all of those involved should consult with the aim of reaching a holistic understanding of: i) their country’s current positioning in GVCs; ii) the strengths and weaknesses of skills policies, and of other types of policies affecting countries’ performance in GVCs; and iii) the potential opportunities for further specialisation. This kind of whole-of-government approach requires moving beyond a short-term policy response to the challenges posed by this new phase of globalisation. In a world that faces major transformations such as globalisation and digitalisation, it is crucial to adopt long-term responses.

References

Autor, D. et al. (2016), “Importing political polarization? The electoral consequences of rising trade exposure”, NBER Working Paper, No. 22637, The National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge, MA.

Autor, D.H., D. Dorn and G.H. Hanson (2015), “Untangling trade and technology: Evidence from local labour markets”, The Economic Journal, Vol. 125/584, pp. 621-646.

Baldwin, R. (2016), The Great Convergence: Information Technology and the New Globalization, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA.

Barro, R. and J.W. Lee (2013), “A new data set of educational attainment in the world, 1950-2010”, Journal of Development Economics, Vol. 104, pp. 184-198.

Haugh, D. et al. (2016), “Cardiac arrest or dizzy spell: Why is world trade so weak and what can policy do about it?”, OECD Economic Policy Papers, No. 18, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/5jlr2h45q532-en.

Mayer, T. and S. Zignago (2011), “Notes on CEPII’s distances measures: the GeoDist database”, CEPII Working Paper, No. 2011-25.

OECD (2015), “How is the global talent pool changing (2013, 2030)?”, Education Indicators in Focus, No. 31, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/5js33lf9jk41-en.

OECD (2013), Interconnected Economies: Benefiting from Global Value Chains, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264189560-en.

Timmer, M.P. et al. (2016), “An anatomy of the global trade slowdown based on the WIOD 2016”, GGDC Research Memorandum, No. 162, University of Groningen.

UNCTAD (2013), World Investment Report 2013 – Global Value Chains: Investment and Trade for Development, United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), Geneva.

← 1. The statistical data for Israel are supplied by and under the responsibility of the relevant Israeli authorities. The use of such data by the OECD is without prejudice to the status of the Golan Heights, East Jerusalem and Israeli settlements in the West Bank under the terms of international law.