Chapter 4. Migration and the labour market in the Philippines

Despite steady economic growth, the Philippine economy is marred by un- and underemployment, contributing to emigration of many people in search of work. This chapter explores what this outflow – and the significant rate of remittance inflows – means for the domestic labour market. It also investigates the role played by labour market programmes – particularly employment agencies and vocational training – in people’s migration decisions. The recommendations for policy are outlined, particularly in terms of how to improve skills matching in the labour market.

People often feel forced to seek jobs in another country when work opportunities at home are scarce or unsatisfactory. Consequently, governments in countries of origin are constantly challenged to improve work opportunities so as to decrease the need for people to seek work abroad. In the case of the Philippines, the constant growth in the past 40 years of the annual outflow of overseas workers (from 300 000 in 1984 to 1.4 million in 2014) indicates that domestic labour policies are not sufficient to generate alternative solutions for all those seeking better employment, although labour policies cannot be isolated from demographic, economic and social factors.

For many years the failure of Philippine policies to generate full employment was attributed to the uneven growth of the economy, which has been subject to cyclical downturns. From the 1970s to the end of the 20th century, the GDP growth rate went through a sequence of boom and bust cycles. Apart from a decline in 2009, in the last 15 years the growth rate has been more stable, averaging 6.2% between 2010 and 2015. However, this growth has not translated into an adequate decline of unemployment and underemployment, leading observers to speak of economic growth without job creation. This is a major explanatory factor for the continuous outflow of workers seeking employment in foreign labour markets.

This chapter explores these interrelationships between migration and the labour market in the Philippines. It begins with an overview of the country’s labour market characteristics, before analysing how various migration channels affect key labour market outcomes, such as the influence of remittances on the work choices of migrant households and individuals. It then analyses the influence of labour market policies and programmes on households’ migration decisions. The chapter concludes with policy recommendations based on the findings of the project.

A brief overview of the Philippine labour market

According to the Philippines’ quarterly Labour Force Survey (LFS), in January 2016, the country had 67 million people aged 15 years old and above, 63.3% of whom were in the labour force (PSA, 2016). Of those in the labour force, 94.2% were employed and 5.8% unemployed. The employment rate of the population 15 years old and above was 59.6%. Underemployment was estimated at 19.7% and it is a significant aspect of the Philippine labour market as it involves around 7 million people.

Underemployment cannot be ignored when considering the real dimensions of employment. Although youth unemployment is an important issue, accounting for almost half of total unemployment (ILO, 2015), the real issue is the large number of underemployed and low productivity workers, who constitute perhaps one third of the labour force (Paqueo et al., 2014). Therefore, poverty in the Philippines is not primarily a matter of joblessness, but of lack of opportunities for gainful employment. In this respect, economic growth was indeed accompanied by job creation, but not sufficiently to decrease underemployment in a significant way. Vulnerable employment (people employed as own-account or contributing family workers) decreased by five percentage points between 2008 and 2013, but still remained as high as 38% (ILO, 2015). Real wages declined between 2001 and 2011, explained by the fact that the Philippines can be considered a country with unlimited labour supply and therefore does not force employers to increase wages (Paqueo et al., 2014).

As expected, the labour force participation rate was higher for men (76%) than for women (50%), (PSA, 2016). The distribution of employment by industry showed that 27% were employed in agriculture, 16% in industry and 56% in services (PSA, 2016). This distribution reflects the well-known anomaly of the Philippine labour market, whereby the decrease of population working in agriculture has never been matched by an increase in the industrial sector. This is because manufacturing has never developed to the point of being able to employ a large portion of the population, not even in the years of import substitution. Industry counted for 13.8% of employment in 1974, when the overseas employment programme started (Chapter 2), and increased only slightly 40 years later, while services has increased from 29% to 53%.

Labourers and unskilled workers were the largest major occupation (31.7%), followed by government officials and managers (16.8%), sales workers (13%) and farmers and fishers (11.5%). Data on employment by class of workers are also helpful to understand the labour profile in the Philippines – they indicate that 63.2% were wage workers, of whom 8.6% were employed by the government and 5.7% worked for a private household. Of the non-wage workers, 25.8% were self-employed in their own businesses (but without paid employees), 3.3% were employers in their own family-operated farm or business, and 7.7% were employed without pay in family-operated farms or businesses (PSA, 2016).

The IPPMD survey was conducted in 1 999 households, distributed equally across the Philippines’ four provinces (Chapter 3). It collected information on all members of households, for a total sample size of 6 554 individuals aged 15 and above. Amongst the working age group (15-64), the labour force participation rate was 56%, significantly lower than the national rate (Table 4.1). This gap is explained by the different formulation of the question on employment in the two surveys. While the LFS asks whether X worked for at least one hour during the past week, the IPPMD survey simply asked what the current employment status of X was. The unemployment rate amongst survey respondents was 9%, higher than the national average, while underemployment cannot be measured through the survey dataset. Consistent with data at the national level, women in the survey had a lower labour force participation rate (41%) than men (66%).

The household survey revealed some small rural-urban differences in individuals’ labour market characteristics. The labour force participation rate is slightly higher in urban areas; unemployment is higher in rural areas; those employed in urban settings are more likely to be in the private sector; and rural areas have a higher percentage of individuals who are not in paid work and not looking for work. Employment in agriculture and fishing is obviously higher in rural settings, while a higher percentage of urban workers are employed as plant and machine operators.

How does migration affect the labour market in the Philippines?

Migration affects the labour market in various ways. The most immediate impact is the loss of people in the labour market. If these people were unemployed before leaving, a significant drop in the labour supply can in theory reduce competition in the labour market, which in turn increases wage levels and decreases unemployment. The consequences, however, can vary according to many factors. If the workers come from a skilled sector for which there is little supply in the labour market, their skills can be lost. If the labour market can easily substitute for workers who emigrate there may be little impact (although there is a general loss of work experience). If an emigrant leaves a household comprised of a married couple with young children, this can reduce the time available for formal employment or increase the workload of the remaining adults (if not compensated for by hiring household workers) (Hagen-Zanker et al., 2014). Emigration can also trigger an investment in skills, both to respond to the international labour market as well as to the vacancies left by migrants in the national labour market (however, this can also result in an oversupply of certain skills).

Migrants in general send remittances home to their families; if these are spent on setting up a business, this can generate employment. On the other hand, receiving remittances can increase the household reservation wage,1 altering the need for household members to be in work. A moral hazard effect of remittances is that household members become remittance-dependent, leave their jobs or do not look for one (Chami, Fullenkamp and Jahjah, 2005). On the other hand, they might use remittances to secure better jobs.

Finally, migrants may return home after a number of years. They might re-enter the labour market as paid employees, either in the same or a different sector; they may or may not use skills acquired abroad; they may decide to be self-employed, either by setting up a business or in a business set up by their household while they were abroad, or by farming land possibly bought on their return; or they might decide to retire if they are nearing retirement age.

The sections which follow attempt to shed light on some of these effects by drawing on the analysis of the IPPMD data.

Emigrants are more likely to come from the more skilled occupations and the health sector

Migration is intuitively considered as a movement that reduces unemployment in the country of origin. However, research has not produced evidence to support this. A review of the literature conducted by Hagen-Zanker (2015) laments the lack of studies in this area. What is mostly unknown or not reported is whether migrants go abroad because they are unemployed or out of paid work or whether they go in search of a better or better paid job. The IPPMD survey sheds some light on this debate. It finds that 11% of those who migrated were unemployed before migration and 22% were not in paid work (Table 4.2), and that migration significantly reduced these percentages for the migrants (down to 0% and 2% respectively). However, at the aggregate level the absorption of about 30% of the annual new hires into paid employment (about 162 000 in 2014) is a significant, but not dramatic reduction of the overall number of unemployed at the national level (2.9 million at the time of the survey). Employment abroad was found mostly in the private sector.

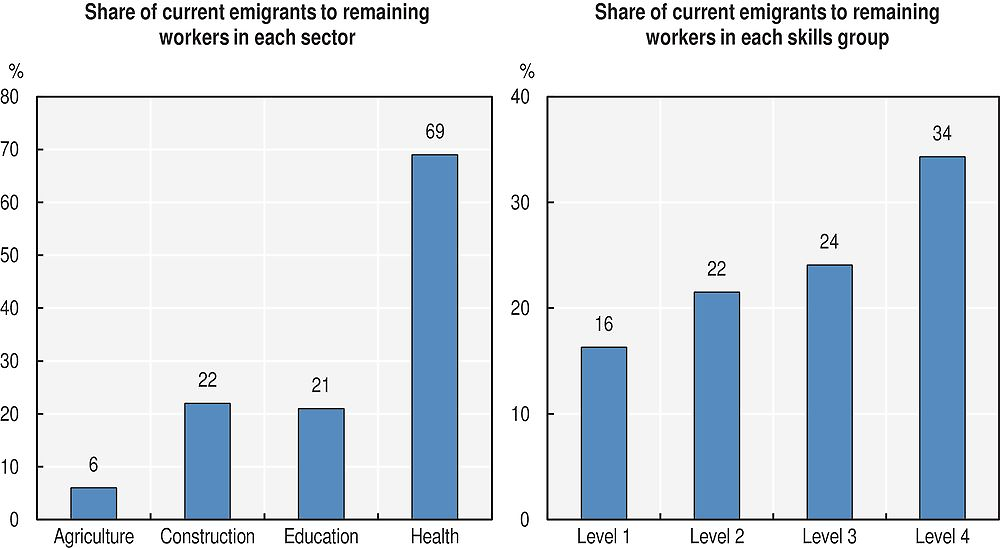

In spite of the large labour supply in the Philippines, emigration may lead to a shortage of skills in specific sectors (Mendoza, 2015). The IPPMD research explored this for four key sectors – agriculture, construction, education and health – comparing the number of emigrants who left each sector with the number of workers remaining (Figure 4.1, left-hand chart). The health sector seems to be the most affected by emigration. The emigration of highly skilled workers can also have a direct impact on the labour market. Exploring the patterns of emigration among occupational groups at different skills levels reveals that the Philippines is losing a larger share of skilled workers to emigration than any other skill groups (Figure 4.1, right-hand chart).

Note: The skills level of occupations has been categorised using the International Standard Classification of Occupations (ISCO) provided by the International Labour Organization (ILO, 2012). Skills level 1: occupations which involve simple and routine physical or manual tasks (includes elementary occupations and some armed forces occupations). Skills level 2: clerical support workers; services and sales workers; skilled agricultural, forestry and fishery workers; craft and related trade workers; plan and machine operators and assemblers. Skills level 3: technicians and associate professionals and hospitality, retail and other services managers. Skills level 4: Other types of managers and professionals.

Source: Authors’ own work based on IPPMD data.

Women in particular seem to respond to migration through their job choices. Table 4.3 in Box 4.1 shows the results of a regression analysis exploring the link between occupational skills level and the receipt of remittances. The results show a significant link between households that receive remittances and female members with occupations which require more complex skills levels. Remittances may have provided women with the resources needed to obtain better employment, such as a better education. On the other hand, higher paid jobs may have allowed other members to emigrate.

To further analyse how migration is associated with the occupational choices of the remaining household members, an ordered logit model was used in the following form:

(1)

(1)

where  represents the occupational skills level of an individual i. Following Figure 4.1, occupations are categorised by their ordered skill levels into four levels.

represents the occupational skills level of an individual i. Following Figure 4.1, occupations are categorised by their ordered skill levels into four levels.  signifies that a household receives remittances.

signifies that a household receives remittances.  stands for a set of control variables at the individual level and

stands for a set of control variables at the individual level and  for household level controls.a

for household level controls.a  implies regional fixed effects and

implies regional fixed effects and  is the randomly distributed error term. Table 4.3 shows the coefficients and standard errors for the main variable of interest.

is the randomly distributed error term. Table 4.3 shows the coefficients and standard errors for the main variable of interest.

← a. Control variables include age, sex and education level of individuals and their households’ wealth estimated by an indicator (Chapter 3) and whether it is in a rural or urban municipalities or cities.

The occupational skills and educational profile of current migrants do not correspond with the occupations they engage in overseas, however. POEA data suggests that emigrants predominantly hold less skilled occupations in their destination countries. The concern about the de-skilling of overseas Filipino workers has been an enduring and recurrent issue (Asis and Battistella, 2013). Based on an analysis of youth employment and migration, young Filipinos (aged 24 and below) tend to land less-skilled occupations overseas, similar to the general pattern of employment of the overseas Filipino worker population (Asis and Battistella, 2013; Battistella and Liao, 2013). This is a worrying trend because such occupations also tend to be less protected, which is not a good start for young migrants. Moreover, given the narrow possibilities for occupational mobility, young Filipino migrants may get stuck in this stable but low-skilled employment (Asis and Battistella, 2013).

Emigration and remittances tend to reduce household labour supply

The literature on the impact of migration on the Philippine labour market offers some conflicting conclusions. Many studies have concluded that migration and remittances generate some level of dependence among the members of the households. Rodriguez and Tiongson (2001) found that adults simply rely on money from abroad rather than seeking employment, or can afford to remain unemployed instead of taking up a job that is not sufficiently satisfactory or remunerative. Other studies concluded that remittances do not have an impact on the labour force participation of the household (Ducanes and Abella, 2008). Cabegin (2006) analysed the impact of migration and remittances on the spouse left behind, concluding that there is a decrease in labour force participation. For wives the decisive factor was the need to spend time with children of school age, while for husbands it was receiving remittances. The issue remains controversial because it is difficult to account for unobserved characteristics of the people, particularly men, left behind (Hanson, 2007). It is possible that the reasons why they did not migrate may also explain why they are not formally employed. Conflicting results depend also on methodological problems (Orbeta, 2008).

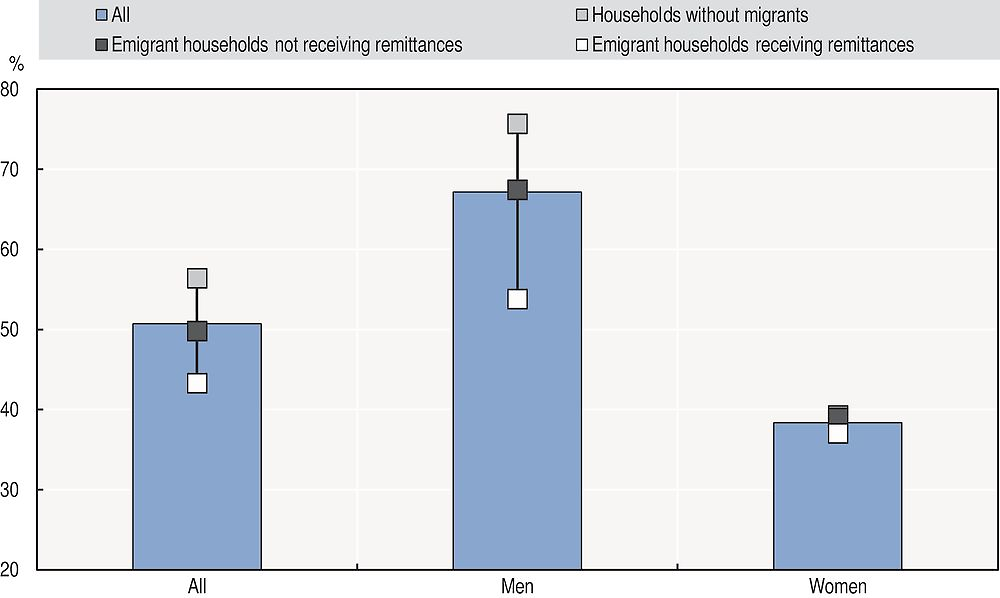

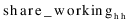

Although it is challenging to isolate individual effects of having a family member who has emigrated and the receipt of remittances, the IPPMD data give some clues on this matter. Figure 4.2 compares the average share of working household members from non-migrant households, emigrant households not receiving remittances and those that are receiving remittances. The graph shows that remittance-receiving households have the lowest share of working adults. Gender patterns differ, however. While there is not much difference between the employment rate for women in remittance versus non-remittance receiving households, men in emigrant households with remittances are less likely to work than men in the other types of households.

Note: The sample excludes households with return migrants only.

Source: Authors’ own work based on IPPMD data.

Regression analysis was carried out to explore how migration is associated with the remaining household members’ labour decisions (Box 4.2). The results suggest that individuals are less likely to be working when their households have at least one emigrant and receive remittances (Table 4.4). The propensity for men not to be working is higher when they belong to a urban household with at least one emigrant. Women are less likely to be working when they receive remittances and live in an urban area, which is consistent with previous studies conducted in Salvador (Acosta, 2006) and Mexico (Hanson, 2007). Remittances more easily substitute wages for women than for men in urban settings as women’s salaries tend to be lower than men’s and there is no longer an incentive to seek paid employment. Individuals living in non-agricultural households appear to be less likely to have a job when the household receives remittances, while emigration of a household member does not seem to have an influence.

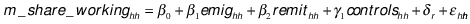

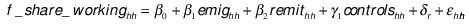

To investigate the link between migration and households’ labour decisions, the following regression models were used:

(2)

(2)

(3)

(3)

(4)

(4)

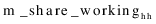

where  signifies households’ labour supply, measured as the share of household members aged 15-64 who are working.

signifies households’ labour supply, measured as the share of household members aged 15-64 who are working.  is the share of male household members that are working among men and

is the share of male household members that are working among men and  for female household members.

for female household members.  represents a variable with the value of 1 where a household has at least one emigrant, and

represents a variable with the value of 1 where a household has at least one emigrant, and  denotes a household that receives remittances.

denotes a household that receives remittances.  stands for a set of control variables at the household level.a

stands for a set of control variables at the household level.a  implies regional fixed effects and

implies regional fixed effects and  is the randomly distributed error term. The models were run for two different groups of households depending on their location

(rural or urban). The coefficients of variables of interest are shown in Table 4.4.

is the randomly distributed error term. The models were run for two different groups of households depending on their location

(rural or urban). The coefficients of variables of interest are shown in Table 4.4.

← a. Control variables include the household’s size and its squared value, the dependency ratio (number of children 0-15 and elderly 65+ divided by the total of other members), the male-to-female adult ratio, family members’ mean education level, its wealth estimated by an indicator (Chapter 3) and its squared value.

Many return migrants turn to self-employment

The literature on return migration to the Philippines is rather scarce, largely because the topic poses conceptual and empirical difficulties. At the conceptual level, it is difficult to determine when a migrant, in a highly circulatory system such as that which characterises Philippines, has definitely returned. The empirical difficulty rises from the lack of administrative data to measure return. The IPPMD study constitutes one of the first attempts to measure return migration in the Philippines.

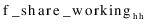

Return migrants tend to come home with greater financial and human capital than when they left. Savings accumulated abroad can be used as a resource for working on their own account. Growing evidence from the literature suggests that return migrants tend to be self-employed or establish their own businesses (De Vreyer, Gubert and Robilliard., 2010; Ammassari, 2004). Figure 4.3 compares the employment status of non-migrants and return migrants for the Philippines. While the share of non-active individuals is considerably lower among return migrants than non-migrants, return migrants are more likely to be unemployed. Looking at the employed population, return migrants are significantly more likely to be self-employed than non-migrants.

Note: The difference between non-migrants and return migrants are statistically significant (using a chi-squared test). Non-active individuals are not working and not looking for work.

Source: Authors’ own work based on IPPMD data.

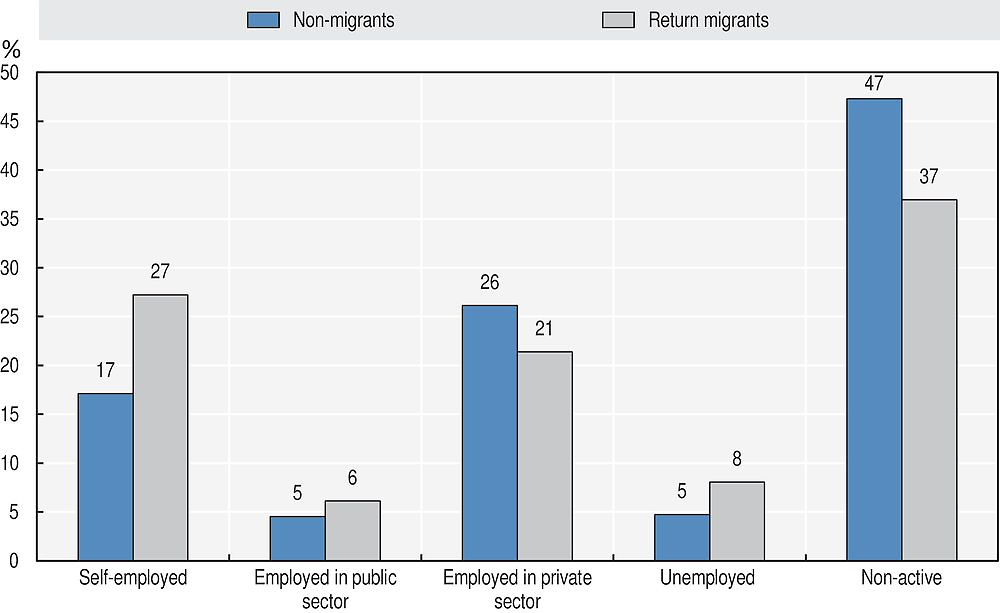

It may be that return migrants were already self-employed prior to emigrating or that they chose migration as a strategy to set up a business or to become self-employed. Figure 4.4 compares the employment status of return migrants before emigration and after their return. This shows a significant increase in self-employment and this is the case for both men and women. Overall, only 13% of the returnees were self-employed before leaving, while 27% were after they returned. The change in employment status for women is noticeable, in particular the increased share of non-active women after return. The data indicate that many women return to a domestic occupation after achieving the objective of the migration project.

Source: Authors’ own work based on IPPMD data.

How do labour market policies affect migration in the Philippines?

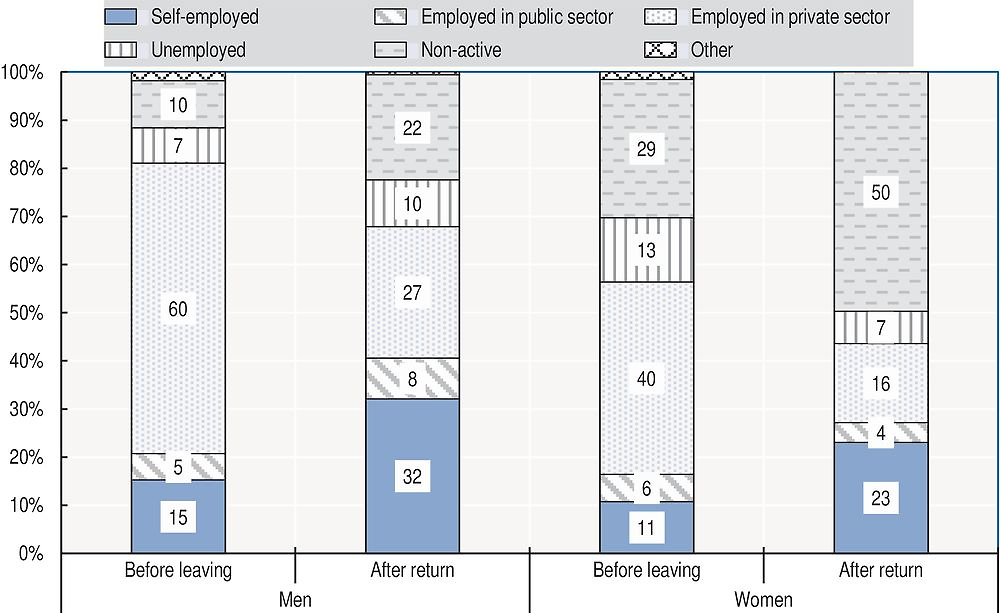

The previous section has investigated how migration affects the labour market. On the other hand, Philippines’ labour market policies also affect migration, directly or indirectly. Policies to improve the domestic labour market may reduce the incentive to migrate. Such policies can seek to enhance labour market efficiency through government employment agencies, improve the skills set of the labour supply through vocational training, and expand labour demand by increasing public employment programmes. To date, the impact of these labour market policies on migration in the Philippines remains unexplored in the research. The IPPMD survey attempted to disentangle the link between these policies and the decision to emigrate and the reintegration of return migrants into the labour market (Box 4.3).

The IPPMD household survey asked household members whether they had benefited from any of the labour market policies and programmes listed in Figure 4.5 in the five years prior to the survey. It asked people employed in the public and private sectors how they found their jobs, with government employment agencies being one of the options. The survey also asked the labour force if they had participated in any vocational training programmes, and if so what type of training they received. They were also asked about participation in public employment programmes.

Note: The IPPMD survey in other countries also asked if individuals received unemployment benefits but this question was not included in the Filipino survey as the Philippines had no unemployment benefits at the time of the survey.

The community survey collected information on the existence of vocational training centres and job centres. It also asked if certain types of training programmes had been held in the communities and whether they had offered public employment programmes.

The primary institution responsible for employment in the Philippines is the Department of Labor and Employment (DOLE). The Bureau of Local Employment (BLE), formerly Bureau of Employment Services (BES), was created by the 1974 Labor Code and operates as part of DOLE. The Philippine Labor and Employment Plan (PLEP) 2011-2016 emphasised decent and productive work and set the goal of creating 1 million jobs every year (DOLE, 2011). The target has been reached, but the quality of new jobs is not always satisfactory, as the target includes temporary workers (9% in 2014) and self-employed and unpaid family workers. To facilitate the matching of jobs and skills, DOLE has created the Philippine Job Network (PHIL-JobNet), an online portal containing labour market information.

While the government has the main responsibility for policies, it is the private sector that has the greatest potential for job creation. Unfortunately, however, private investment in the Philippines is below expectations (Bocchi, 2008). This was also acknowledged by the Philippine Development Plan 2011-2016 (NEDA, 2011), which observed that the investment-to-GDP ratio had fallen to 15% in 2010. Labour unions also play an important role;2 however, their main focus on minimum wages has been criticised as protecting their constituents who already hold a job rather than promoting job creation. In fact the legal minimum wage in the Philippines is among the highest in Asia and is ultimately considered not beneficial for workers, particularly for those with low human capital, such as “the young, the inexperienced, the less educated and the women” (Paqueo et al., 2014).

Keeping these observations in mind, the rest of the chapter will limit itself to examining the most relevant labour employment and vocational training programmes enacted by the Philippine government and their utilisation by the migrant and non-migrant households in the IPPMD.

Government employment agencies can curb emigration

If people can find jobs in the local labour market through government employment agencies, they may choose to stay rather than move abroad to seek work. A comparative study of the ten IPPMD partner countries suggests that the share of people who have no plans to emigrate is higher for those who found jobs through government employment agencies than those who did not (OECD, 2017).

Government employment agencies aim to improve the functioning of the labour market by providing information on the economy and local labour market, including employment opportunities. The Public Employment Service Office (PESO) was established in 1999. It helped some 5.6 million Filipinos to find a job between 2010 and 2015, according to the Department of Labor and Employment. PESO offices organise job fairs and livelihood and self-employment bazaars among others. As of December 2014, PESO had 1 925 offices, although only 390 were provided with the necessary personnel and funds to operate on a regular basis. To remedy this, an amendment signed by President Aquino in 2015 mandated that the office be institutionalised in all provinces, cities and municipalities. Establishments are required to submit to local government units the number and type of jobs in demand; this information will be submitted to PESO for job matching and to educational institutions for career guidance. The law has expanded the functions of PESO to provide not only employment facilitation services, but also labour market trends and information, training and other capacity-building initiatives.

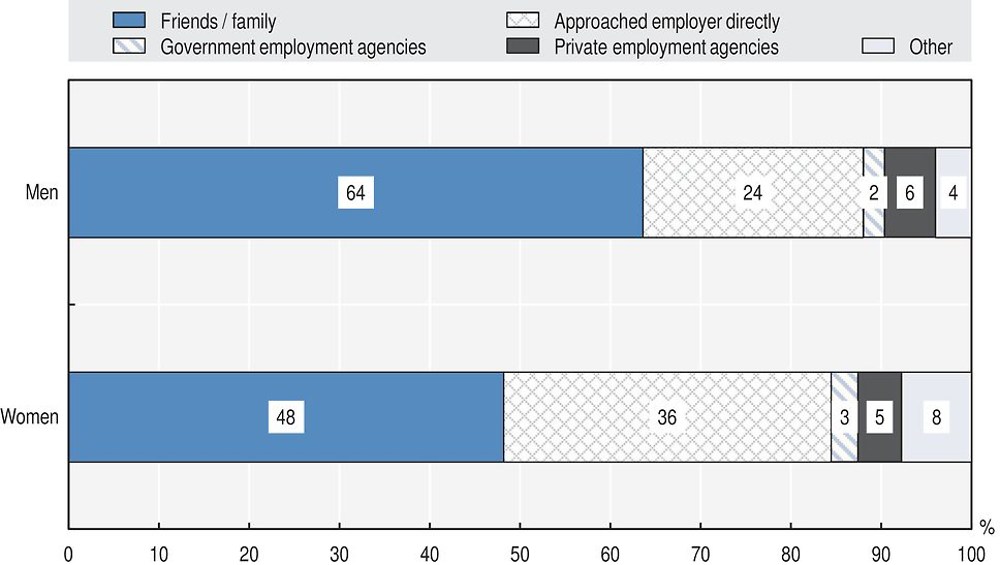

To what extent did people in the IPPMD Philippine survey benefit from government employment agencies? The survey asked how people found their jobs. The results indicate that very few (2.6%) used the services of government agencies. The vast majority (87%) obtained employment through friends and relatives and by approaching the employer directly. Interestingly, there is a clear difference between men and women in job-seeking strategies. Men prefer to go through family and friends (64% versus 48%) while women prefer to approach the employer directly (36% versus 24%) (Figure 4.6). Private employment agencies were used by 5% of all individuals. This percentage increases to 7% for individuals in households with a return migrant, and to 9% for males in return migrant households.

Source: Authors’ own work based on IPPMD data.

While the share of people who benefited from government employment agencies is low, there are certain patterns related to migration: 86% of the beneficiaries of government employment agencies have no plans to emigrate, which is lower than the share among non-beneficiaries (79%).3 Individual characteristics matter, of course. Beneficiaries are more likely than non-beneficiaries to have higher education levels and to hold jobs in the public sector, which are seen as secure occupations.

Vocational training programmes spur emigration in the Philippines

DOLE 2020 Vision, Jobs Fit is a government programme to identify the skills needed by the emerging industries in the regions and to reduce the job-skills mismatch. The project identified 12 key employment generators. The 2013 revision ascertained that in the Philippine labour market there were 273 hard-to-fill positions. The DOLE report was used by the Technical Education and Skills Development Authority (TESDA) to refine its Technical and Vocational Education and Training (TVET) programmes. In addition to TVET provided within the school system, vocational education is also offered at regional and provincial TESDA centres, through community-based training programmes organised in co-operation with local government units, and by the private sector through enterprise-based training.

According to data from TESDA, 4 609 institutions together offered 20 329 programmes as of July 2015. The top three sectors are tourism, ICT and health, social and other community development, which are also the fastest growing sectors of the Philippine economy (Orbeta and Esguerra 2016). In 2012, TVET courses were taken mostly by high school graduates (50%), as well as also by college students; 7% were high school undergraduates. The two main reasons for taking TVET courses were to gain employment (45%) and to improve skills (38%).

The Philippine Qualification Framework was developed in 2012 and certifies eight different skill levels. It includes a qualification and certification system which ensures that students have acquired the necessary competencies. Some challenges still remain for the vocational programmes, such as the scarcity of centres for community-based programmes, the uneven quality of education in the different regions, the low absorption of vocational students by the labour market and the low prestige attached to vocational studies (UNESCO-UNEVOC, 2014).

The IPPMD survey found that about 5% of the labour force had participated in a vocational training programme in the past five years. The rate of participation is similar for men and women; and in rural and urban areas. The most common training programmes among the IPPMD respondents were mechanic-related programmes (29%), followed by computer and IT (13%) and electricity and plumbing (12%).

Vocational training programmes affect migration in several ways. While they might help people secure better jobs in the domestic labour market, they can also be a means to make would-be migrants more employable overseas. The latter seems to be the case for the Philippines. Regression analysis explored how participating in vocational training programmes is related to plans to emigrate (Box 4.4). It suggests that people in the Philippines are more likely to have plans to emigrate when they receive vocational training. The relevance of the training programmes to the domestic labour market may play a role here. If training does not lead to the right job or a higher income, it may increase the incentive to withdraw from the domestic labour market and search for jobs abroad. It is also possible that people are participating in vocational training programmes in order to find jobs abroad.

To investigate the link between participation in vocational training programmes and having plans to emigrate, the following probit model was used:

Prob( (5)

(5)

where  represents whether individual i has a plan to emigrate in the future. It is a binary variable and takes a value of 1 if the

person is planning to leave the country.

represents whether individual i has a plan to emigrate in the future. It is a binary variable and takes a value of 1 if the

person is planning to leave the country.  is the variable of interest and represents a binary variable indicating if the household has at least one member who participated

in a vocational training programme in the five years prior to the survey.

is the variable of interest and represents a binary variable indicating if the household has at least one member who participated

in a vocational training programme in the five years prior to the survey.  stands for a set of control variables at the individual level and

stands for a set of control variables at the individual level and  for household level controls.a

for household level controls.a  implies regional fixed effects and

implies regional fixed effects and  is the randomly distributed error term. The model has been tested for two different groups of households depending on their

location (urban or rural). The coefficients of variables of interest are shown in Table 4.5.

is the randomly distributed error term. The model has been tested for two different groups of households depending on their

location (urban or rural). The coefficients of variables of interest are shown in Table 4.5.

← a. Control variables include age, sex, education level of individuals and whether the individual is unemployed or not. At the household level, the household’s size and its squared value, the dependency ratio, its wealth indicator and its squared value are controlled. Whether the household has an emigrant or not is also controlled.

Public employment programmes are too small scale to have an impact

The Community-based Employment Program (CBEP) is the overall umbrella of government initiatives to provide short-term employment to disadvantaged people. It consists of three components: infrastructure jobs, non-infrastructure jobs (such as livelihood programmes) and emergency employment projects. Between 2011 and 2014, 8.6 million disadvantaged people benefited from the various programmes. Of them, 3.5 million jobs were created by infrastructure projects and 5 million by non-infrastructure projects, according to the Secretary of Labour. Among the CBEP, it is worth mentioning the Special Program for Employment of Students (SPES), mandated under Republic Act No. 9547, which aims at helping poor but deserving students through employment during summer and other holiday periods. From 2010 to 2013, 493 742 students, 42.5% of them women, took advantage of the programme. In spite of these numbers, researchers have observed that CBEP only has a transitory impact on the labour market, since the programmes are designed more to address social issues than providing a net employment impact (Ballesteros and Israel, 2014).

The take-up ratio of public employment programmes (PEPs) among the IPPMD surveyed households in the Philippines is low, at 1%. This poses challenges for exploring the relationship between PEPs and migration. In theory, PEPs can either increase or decrease the incentives to migrate depending on households’ response to the additional income received through such programmes. Programmes which improve local employment opportunities may reduce the incentives to migrate as the opportunity cost of migration increases. In rural areas in particular, public works programmes to support agricultural workers during the farming off-season can provide an alternative to seasonal migration. On the other hand, the increased income received may encourage migration. Overall, the impact of PEPs on migration is likely to depend on their duration, coverage and income level.

Conclusions and policy recommendations

Despite the Philippines’ robust growth between 2010 and 2015, the country has not been able to create sufficient high quality jobs leading many people to look for employment abroad. The government has put in place a variety of initiatives to foster job creation, but these do not seem to have had a strong impact on the culturally embedded propensity of Filipinos to migrate (Chapter 2).

The IPPMD research confirms that it is the more highly skilled occupational groups that lose the most labour to emigration, especially the health sector. In addition, migration can be a de-skilling experience for Filipinos – particularly for women, who tend to only find employment abroad in occupations for which they are over qualified. Within the Philippines, emigration and remittances tend to curb households’ activity in the labour market although women tend to use remittances to upskill, and self-employment is a common phenomenon among return migrants.

The investigation into the influence of labour market policies on migration decisions finds that government employment agencies are hardly used by job seekers. On the other hand, vocational training programmes seem to encourage people to emigrate and are possibly used by people to find jobs abroad. It may also be the case that the training programmes do not match the needs of the domestic labour market.

While policies are needed to address the potential negative effects of migration and to amplify its positive effects on the labour market, labour market policies should also incorporate migration into their design. Here are some policy recommendations deriving from the findings in this chapter:

-

To stem the loss of the highly skilled, better skills matching mechanisms are needed as well as ensuring the creation of quality jobs.

-

Vocational training programmes can be better targeted to match demand with supply by mapping the shortages in the domestic labour market, especially at the local government level, and strengthening co-ordination mechanisms with the private sector. They can also aim to foster the reintegration of return migrants into the labour market.

-

The government could consider expanding the coverage of the Public Employment Service Office’s (PESO) portal to include more domestic jobs. Strengthening the PESO’s technological capacity will allow it to reach more people in the provinces and local communities, as well as emigrants abroad and return migrants at home.

-

Building closer connections between the employment agencies and the private sector will be important.

References

Acosta, P (2006), “Labour supply, School Attendance, and Remittances from International Migration: The case of El Salvador”, World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 3909, Washington, DC.

Ammassari, S. (2004), “From nation-building to entrepreneurship: the impact of élite return migrants in Côte d’Ivoire and Ghana”, Population Space Place, 10: pp. 133–154, doi: 10.1002/psp.319.

Asis, M.M.B. and G. Battistella (2013), The Filipino Youth and the Employment-Migration Nexus in the Philippines, UNICEF-Philippines and Scalabrini Migration Center, Makati City and Quezon City, https://www.unicef.org/philippines/Filipino-Youth-Employment-Migration-Nexus.pdf.

Ballesteros, M.M. and D.C. Israel (2014), “Study of government interventions for employment generation in the private sector”, PIDS Discussion Paper Series 2014-28, Philippine Institute for Development Studies, Makati City, http://dirp3.pids.gov.ph/webportal/CDN/PUBLICATIONS/pidsdps1428.pdf.

Battistella, G. and K.A.S. Liao (2013), Youth Migration from the Philippines: Brain Drain and Brain Waste, UNICEF-Philippines and Scalabrini Migration Center, Makati City and Quezon City, https://www.unicef.org/philippines/Youth-Migration-Philippines-Brain-Drain-Brain-Waste.pdf.

Bocchi, A.M. (2008), “Rising growth, declining investment: the puzzle of the Philippines”, Policy Research Working Paper 4472, World Bank, Washington DC, http://econpapers.repec.org/paper/wbkwbrwps/4472.htm.

Cabegin, E.C.A. (2006), “The effect of Filipino overseas migration on the non-migrant spouse’s market participation and labor supply behavior”, IZA Discussion Paper Series No. 2240, Institute for the Study of Labor, Bonn.

Chami, R., C. Fullenkamp and S. Jahjah (2005), “Are Immigrant Remittance Flows a Source of Capital for Development?”, IMF Staff Papers, Vol. 52, No. 1, International Monetary Fund.

Danish Trade Union Council for International Development Cooperation (2014), The Philippine Labor Market Profile 2014, Danish Trade Union Council for International Development Cooperation, Copenhagen.

De Vreyer, P., F. Gubert and A.S. Robilliard (2010), “Are There Returns to Migration Experience? An Empirical Analysis Using Data on Return Migrants and Non-migrants in West Africa”, Annals of Economics and Statistics, Vol. 97/98, pp. 307–28, www.jstor.org/stable/41219120.

DOLE (2011), The Philippine Labor and Employment Plan 2011-2016. Inclusive Growth through Decent and Productive Work, Department of Labor and Employment, Manila, http://www.dole.gov.ph/fndr/bong/files/PLEP-26%20April%20version.pdf.

Ducanes, G. and M. Abella (2008), “Overseas Filipino workers and their impact on household employment decisions”, Working Paper No. 8, ILO Asian Regional Programme on Governance of Labour Migration.

Hagen-Zanker, J. (2015), “Effects of remittances and migration on migrant sending countries, communities and households”, Overseas Development Institute, London, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/57a08999ed915d3cfd000326/Effects_of_remittances_and_migration_56.pdf.

Hagen-Zanker, J., R. Mallett, A. Ghimire, Q. Shah and B. Upreti (2014), “Migration from the margins: mobility, vulnerability and inevitability in western Nepal and north-western Pakistan”, Report 5, Secure Livelihoods Research Consortium, Overseas Development Institute, London, www.nccr.org.np/uploads/publication/72a205aef977e2745e5377142ff08a1e.pdf.

Hanson, G. (2007), “Emigration, remittances and labor force participation in Mexico”, INTAL & ITD Working Paper 28, Institute for the Integration of Latin America and the Caribbean, Buenos Aires.

ILO (2015), Philippine Employment Trends 2015. Accelerating inclusive growth through decent jobs, International Labour Organization, Country Office for the Philippines, Makati City, www.ilo.org/manila/publications/WCMS_362751/lang--en/index.htm.

Mendoza, D.R. (2015), “Human Capital: the Philippines’ labor export model”, World Policies Review, 16 June, www.worldpoliticsreview.com/articles/15998/humancapital-the-philippines-labor-export-model.

NEDA (2011), Philippine Development Plan 2011-2016, www.neda.gov.ph/2013/10/21/philippine-development-plan-2011-2016/.

OECD (2017), Interrelations between Public Policies, Migration and Development, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264265615-en.

Orbeta, A.C. Jr. (2008), “Economic impact of international migration and remittances on Philippine households: what we thought we knew, what we need to know”, PIDS Discussion Paper Series No. 2008-32, Philippine Institute for Development Studies, Makati City, http://dirp3.pids.gov.ph/ris/dps/pidsdps0832.pdf.

Orbeta, A.C. Jr. and E. Esguerra (2016), “The National System of Technical Vocational Education and Training in the Philippines: review and reform ideas”, PIDS Discussion Paper Series No. 2016-07, Philippine Institute for Development Studies, Makati City, http://dirp3.pids.gov.ph/websitecms/CDN/PUBLICATIONS/pidsdps1607_rev.pdf.

Paqueo, V.B., A.C. Orbeta, Jr., L.A. Lanzona, Jr. and G.C. Dulay (2014), “Labor policy analysis for jobs expansion and development”, PIDS Discussion Paper Series No. 2014-34, Philippine Institute for Development Studies, Makati City, http://dirp3.pids.gov.ph/webportal/CDN/PUBLICATIONS/pidsdps1434_rev.pdf.

PSA (2016), “Current labor statistics”, April, Philippine Statistics Authority, Quezon City, https://psa.gov.ph/tags/current-labor-statistics-april-2016-issue.

Rodriguez, E.R. and E.R. Tiongson (2001), “Temporary migration overseas and household labor supply: Evidence from urban Philippines”, International Migration Review, 35(3), pp. 708-725.

UNESCO-UNEVOC (2014), World TVET Database: Philippines, www.unevoc.unesco.org/go.php?q=World+TVET+Database&ct=PHL.

Notes

← 1. The reservation wage means the lowest wage rate people would be willing to accept.

← 2. The trade union density in the Philippines is considered rather low (Danish Trade Union Council for International Development Cooperation, 2014).

← 3. The difference is not statistically significant (using a chi-squared test).