Chapter 1. Overview of the Irish higher education system

This chapter presents the Irish higher education system. It describes the multi-step ladder system of qualifications that allows students to step in and out of undergraduate education. It presents trends in student numbers and resources of higher education institutions. Further it provides an overview of recent policy initiatives, such as the National Strategy for Higher Education to 2030, the System Performance Framework and the Strategic Dialogue and institutional performance compacts with individual higher education institutions, and the establishment of the Regional Clusters of higher education institutions. These will be further discussed in subsequent chapters.

Higher education providers

Higher education in Ireland is provided by public and private higher education institutions (HEIs). The public HEIs include seven universities, fourteen institutes of technology (IOTs) and seven colleges of education, several of which are in the process of merging with universities, and five colleges recognised by the National University of Ireland. In addition, a number of other third-level institutions provide specialist education in such fields as art and design, medicine, business studies, rural development, theology, music and law. Universities operate under the 1997 Universities Act, which sets out the objects and functions of a university, the structure and role of governing bodies, staffing arrangements, composition and role of academic councils and sections relating to property, finance and reporting. The governing authorities are required to see that strategic development plans are in place, along with procedures for evaluating teaching and research. The legislative framework preserves the academic freedom of the universities and respects the diverse traditions and institutional autonomy of each university. Institutes of Technology operate primarily under the 1992 Regional Technical Colleges Act and the 2006 Institutes of Technology Act. The latter provided IOTs with a similar relationship to the Higher Education Authority (HEA) as the universities. It also provided IOTs with greater autonomy, improved governance and a statutory guarantee of academic freedom. Colleges operate under various pieces of legislation. Most public HEIs are under the purview of the HEA but a small number are directly funded by the Department of Education and Skills (DES). Further, several private colleges receive state funding from competitive programmes such as through the recent labour market activation initiative called Springboard.

Approximately 90% of higher education students in Ireland attend public institutions. Private higher education providers do not generally provide information on registered students to the HEA. A study undertaken for the HEA in 2012, estimated that the private colleges account for approximately 10% of the total higher education student population in Ireland (DES, 2015). The private HEIs are mostly located in Dublin and have significant presence in part time, international education and in labour market activation programmes in the Dublin area.1

Student numbers

The higher education component of Ireland’s qualifications framework comprises: Level 6 (Higher Certificate), Level 7 (Ordinary Bachelor Degree), Level 8 (Honours Bachelor Degree/Higher Diploma), Level 9 (Masters Degree), and Level 10 (Doctorate). The majority of students are enrolled on Level 8 degree programmes. Between 2011 and 2014 there was a 7.1% increase in the number of graduates.

Applications for entry to undergraduate courses in universities, IOTs and colleges are processed by the Central Applications Office (CAO). The aim of the system is to process applications centrally and to deal with them in an efficient and fair manner. The participating HEIs retain the function of making decisions relating to admissions. In 2014/15 there were 217 520 students enrolled in HEA-designated HEIs, including full-time, part-time and remote students, and of these 42 464 were new undergraduate entrants, that is a 17% increase in the seven years from 2007/08. Table 1.1 provides a breakdown across the three major sectors, and Table 1.2 shows the distribution across the different levels of the qualifications framework.

In 2014/2015, the number of international students in Ireland studying in a full-time course for a semester or more in a public or private HEI was 33 118, of whom 11 678 are EU students and 21 440 are non-EU. This represents an increase of 58% in the number of international students since 2010/11.

According to most recent data the highest number of new entrants in universities is in humanities and arts (28%), followed by both social science, business and law, which has the highest number of new entrants in institutes of technology and the second highest in universities (24%). The lowest number of entrants in both is recorded for agriculture and veterinary science. Table 1.3 shows the percentage distribution of new entrants across different disciplines in both universities and IOTs in 2014/15.

A multi-step ladder system of qualifications

At undergraduate level, Ireland has introduced a multi-step ladder system of qualifications. This allows students to step in and out of undergraduate education. This system has several advantages. It helps to improve retention and progression rates within the higher education system by allowing students to obtain a full qualification at an earlier stage within the undergraduate cycle. Students can decide on how to progress with their undergraduate studies in terms of the level at which they enter and exit. The flexibility to enter and exit at different levels means that students can gain exposure to industry and business, both at home and abroad, and return to their studies at a later stage.

Resources in Irish higher education

Current funding model

The current funding model of higher education is kept under ongoing review with the primary objective of ensuring that it appropriately supports the national objectives set for the higher education system. The introduction of performance funding and the provision of incentivisation funding for clusters of collaborating institutions represents a major new departure. Funding discussions between the HEA and the HEIs are now integrated into the strategic dialogue process (see below) rather than standalone budget meetings as was previously the case.

The recently published Report of the Expert Group on Future Funding (Cassell’s Report) states that Ireland’s higher education system needs a substantial increase in the level of investment to ensure that the system is able to deliver fully on its role in supporting national economic and social development. The report also states that the investment must be linked to enhanced quality and verification of outcomes. The report points to a number of different potential ways to provide additional funding for higher education, including increased state funding, increased state funding with a student loan system and an increased contribution from enterprise (HEA, 2016a).

Under current funding arrangements, the HEA allocates exchequer funding to HEIs through the Recurrent Grant Allocation Model (RGAM) which was initially introduced for the universities in 2006 and for the IOTs from 2011, and has three main elements:

-

An annual recurrent “block” grant that is allocated to each institution based on known formulae relating to the number of students and their subject areas. The principle behind the grant is that it should be fair, simple, transparent, that there should be uniformity in the core grant allocation for students in the same broad areas (regardless of the institution at which they study), and that there should be recognition of the extra costs that arise for students from under-represented backgrounds and research students.

-

Performance related funding that is allocated to institutions based on benchmarked performance in delivering on national objectives set for their sector. This type of funding is being phased in (from 2014), and it is expected to account for up to 10% of annual funding in time.

-

Targeted/strategic funding that supports national strategic priorities and which may be allocated to the HEIs on a competitive basis.

The annual grant that HEIs receive is allocated as a block grant, and how funds are allocated internally (for example, across faculties and between research and teaching) is a matter for each institution. There are two main elements to the allocation model, a core grant and a grant in lieu of undergraduate fees. As an incentive to maximise the other income that HEIs may earn, such income is not taken into account in the grant allocation.

The RGAM includes a moderating mechanism that ensures that the grant allocation per HEI may not change by more than 2% (increase or decrease) from year to year. The purpose of this is to prevent large swings in allocations and to help institutions maintain financial stability.

The core grant is allocated based on a standard per capita amount for each student, “weighted” by the relative cost of the student’s subject group. This system of weighting draws significantly from that used by the Higher Education Funding Council for England (HEFCE) and reflects the fact that broad groups of subjects have different levels of resource requirements. The student numbers used for calculating the amount are those as at 1 March in the previous academic year. Table 1.4 shows the four subject groups and their weighting.

An adjustment is made within the core grant allocation to reflect the costs to the institutions of attracting and supporting students who come from non-traditional backgrounds. An additional weighting of 33% is currently used. The current funding model also includes an adjustment to equalise overall funding provided for level 6, 7 and 8 programmes in the IOTs, thereby removing the previous financial disincentive in relation to the provision of level 6 and 7 programmes. Most recently, a specific detailed report on funding in the IOTs (HEA, 2016b) has recommended an adjustment be applied to STEM funding for IOTs in recognition of the declining impact of STEM weightings as a consequence of increasing student contribution and decreasing RGAM allocations.

Allocation of funding based on research is organised in the following way. In addition to weighting research students, 5% of the core allocation is top-sliced (exclusive of the grant in lieu of tuition fees) and allocated on the basis of research criteria (research degrees awarded and contract research income per academic staff). This element of the model currently applies only to universities.

Funding levels and trends

Between 2008 and 2014 the total income (from all sources) per student decreased by 22%. The overall level of state funding of HEIs has been declining since 2007/08, and by 2015/16 it was at 51% of total funding, compared to 76% in 2007/08. This continuing decline is in line with public policy measures in relation to increases in the student contribution (student charge or fee) and reductions in overall funding, including income from the student contribution. When taking into account the fact that approximately half of the student charge income is paid indirectly by the Exchequer through student higher education grants, the decline in funding is from 78% of the total in 2008 to 68% in 2013 and to 64% in 2016. This compares with the OECD average of 68% and the EU21 average of 76.4% for 2010, the latest year for which data is available.

By 2016, privately paid student contributions, that is, excluding higher education grants and as distinct from the total of income from non-state sources, have amounted to 19% of total HEI income. Income from research grants and contracts as a proportion of the total income of universities and institutes of technology has increased from EUR 373 million or 13% of income in 2002 to EUR 453 million or 19% of total income in 2011. Table 1.5 shows the changes in the composition of total recurrent income of HEIs from 2007/08 to 2014/15.

Expenditure per student by HEIs (excluding research expenditure) has declined by 15% in the five years to 2013, and the bulk of this decline is accounted for by the growth in student numbers. Expenditure per student will have declined by 24% over the eight years from 2008 to the end of the Strategic Dialogue period in 2016. The HEA considers that the rapid decline in funding per student constitutes a strong warning that it may not be possible to achieve all of the projected future increases in enrolment or that future increases may be delivered at the expense of quality. Table 1.6 presents the actual and projected expenditure per student.

Research funding

Research funding in higher education has decreased in recent years and the vast majority of the research and development (R&D) component of the block grant allocated to cover core teaching and research activities within institutions is spent on salaries and overheads. Ireland does not have a system for allocating core funds to HEIs for research purposes. The core funding is allocated as a block grant, using a formula which top-slices a research element. It is up to the HEIs to determine its internal allocation. As a result of the reductions in the block grant and a period of no capital investments, the research infrastructure in terms of equipment and facilities that were invested during less constrained times are becoming obsolete. To counter this, Science Foundation Ireland has provided funding to HEIs through its Research Infrastructure Programme and there are commitments to fund capital equipment and to increase human capital as part of Innovation 2020, Ireland’s new strategy for research and development, science and technology.

There are three main competitive research funding agencies: the Irish Research Council (IRC), the Health Research Board (HRB) and Science Foundation Ireland (SFI), each with distinct and complementary missions. Other state and semi-state bodies that fund research do so as part of their function (e.g. Teagasc). SFI funds research centres and large projects with economic impact as a priority. The IRC funds smaller, individually focused programmes targeted at human capital development in the research arena. The HRB focuses on the clinical domain and the health system. In addition, Enterprise Ireland focuses on innovation, near market and enterprise competitive supports. Each of these funding sources have their own, often complex processes for responding to calls for applications. There is no common research classification system, which makes sharing data between agencies difficult. Lead times from application to award can be lengthy. Research programmes are all allocated competitively and this means that the HEIs and individual researchers must compete with each other, as well as with other public and private research organisations, both nationally and (in the case of EU funds) internationally.

It is worth noting HEI success in competing for EU research funding. Of the EUR 625 million drawdown under DFP7, the Higher Education Institutions accounted for 65% of total drawdown (EUR 409 million), with Ireland’s companies accounting for 26% (EUR 164 million) of total funding secured. More recently, in the period from commencement of Horizon 2020 in January 2014 to September 2016 (latest report available) there were 5 298 applicants from Irish-based organisations in Horizon 2020 proposals. From these, 811 applicants were successful, giving an overall Irish success rate of 15.31% (EU Member State average: 14.13%). Ireland’s drawdown in Horizon 2020 in this period was EUR 336 million. The HEIs were the primary beneficiaries, accounting for 59% of all funding. Funding to Private Industry was 31%, with public bodies, research organisations and others (e.g. hospitals) making up the rest (9.9%).

The Innovation 2020 strategy recognises the importance of continuing to support excellent research across all disciplines. The national research prioritisation exercise in 2011/12 identified 14 priority areas where future competitively awarded research funding should be focused. The criteria used to select the areas were:

-

The priority area is associated with a large global market or markets in which Irish-based enterprises already compete or can realistically compete.

-

Publicly performed R&D in Ireland is required to exploit the priority area and will complement private sector research and innovation in Ireland.

-

Ireland has built or is building (objectively measured) strengths in research disciplines relevant to the priority area.

-

The priority area represents an appropriate approach to a recognised national challenge and/or a global challenge to which Ireland should respond.

The prioritisation exercise did not affect the balance of funding between the Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics (STEM), and Arts Humanities and Social Sciences (AHSS).

Source: Source: DJEI (2013).

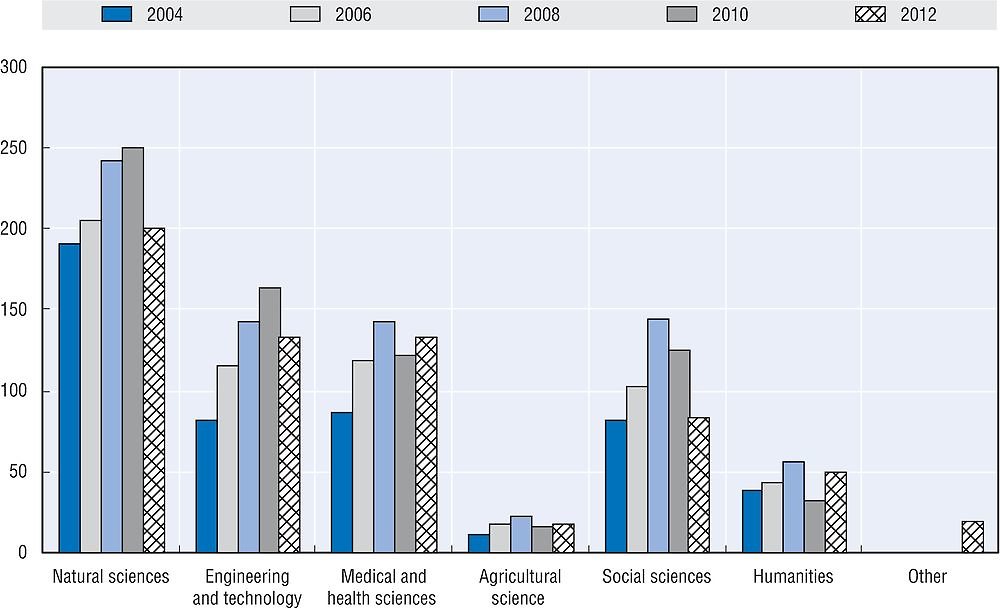

Looking at funding between 2008 and 2012, there has been a reduction in funding for AHSS. In 2008, funding was EUR 201 million and this dropped by 32% or EUR 65 million in 2012 to EUR 134 million. Most of this reduction was in the social sciences area. Other disciplines also saw reductions between 2008 and 2012, but not as much.

In 2013 the Independent Review of Research Prioritisation pointed out that for many research areas, including most of the Humanities and Social Sciences, and basic and applied STEM outside the 14 priority areas, the only national funding schemes available were those administered by the Irish Research Council. These account for 4% of total public investment in R&D and concentrate on individual awards for PhD students and postdoctoral researchers. The report goes on to state that the scarcity of national funding for areas outside the Research Prioritisation, even in some areas where Ireland had significant capacity prior to the Research Prioritisation, may undermine Ireland’s ability to respond to emerging or unforeseen areas of opportunity in the future. There is a concern that researchers from those areas will exit the system, with adverse consequences for higher education, skills supply and the broader ecosystem.

Staffing arrangements

The HEIs have absorbed substantial cuts in public funding while meeting demands for increased intake of students and maintaining quality. In this environment of constrained resources, workload management models can support a more sustainable use of resources and greater and more transparent efficiency. It remains particularly difficult, however, to make workload comparisons across disciplines and institutions. As a result of this, most institutional models require further development – mainly in the area of better workload data collection and analysis.

Institutional workload management models have been developed and implemented since 2010 as part of wide-scale reforms of the public sector. A review of staffing arrangements carried out in 2014 found that all universities and most other HEIs have introduced workload management practices since 2010, see Table 1.7 for data relating to staffing (HEA, 2014b).

Higher education policy framework

Key actors

The Department of Education and Skills (DES) is the government department responsible for all aspects of education and training in the country. Public policy in higher education and research is informed by the work of the Higher Education Authority (HEA), a statutory state agency established with its own board under the aegis of the DES. The HEA is accountable to the Minister for Education and Skills for the achievement of national outcomes for the higher education sector. It exercises a central oversight role in the higher education system and is the lead agency in the ongoing development of a co-ordinated system of HEIs that have diverse but clear roles appropriate to their individual strengths and are responsive to national strategic objectives. Its responsibilities include i) leading the strategic development of Irish higher education and research; ii) advising the Minister and the Department of Education on all matters relating to higher education; iii) acting as the funding authority for the universities, institutes of technology and other designated HEIs; iv) ensuring effective governance and regulation of HEIs and of the higher education system as a whole; v) promoting equity of access to higher education; and vi) enhancing HEIs’ responsiveness to the needs of wider society. A central mission of the HEA is therefore to ensure that higher education and research remain responsive to the social, cultural and economic development of Ireland and its people and support the achievement of national objectives. This includes ensuring that institutional strategies are aligned with national objectives, that there is effective performance management at institutional and system-level, and that due regard is given to institutional autonomy and academic freedom.

The Department of Jobs, Enterprise and Innovation (DJEI) is responsible for developing, promoting and co-ordinating science, technology and innovation policy in Ireland, including opening access to opportunities for Ireland’s research and enterprise communities. DJEI is also responsible for Science Foundation Ireland (SFI), which funds oriented basic research and applied research in the areas of Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics (STEM), and more recently has seen an expansion of its mandate to cover applied research, as well as for the “Programme for Research in Third Level Institutions”, which supports research in humanities, science, technology and the social sciences, including business and law. DJEI also has responsibility for Enterprise Ireland, the agency charged with the development of indigenous enterprise and IDA Ireland, the agency charged with responsibility for foreign direct investments.

Over the past 20 years Ireland has operated on the basis of an emerging European model that places a strong emphasis on institutional autonomy in higher education, and within which HEIs take primary responsibility for quality assurance. An external agency, Quality and Qualifications Ireland (QQI) was established in 2012 as a result of the amalgamation of three existing quality assurance agencies. QQI is responsible for ensuring the effectiveness of the HEIs’ internal quality assurance arrangements through external monitoring and review. Public HEIs are self-validating but QQI is responsible for validating programmes in private HEIs and in further education and training providers. The method used in higher education is quite intensive with a separate independent 4-5 person panel visiting the institution/provider for each new programme approval.

Recent policy developments

The National Strategy for Higher Education to 2030

The National Strategy for Higher Education to 2030 was published by the Department of Education and Skills in January 2011 and provides a clear policy framework and context for higher education in Ireland (DES, 2011). The strategy sets out a new vision in which higher education will play a central role in making the country recognised for innovation, competitive enterprise and continuing academic excellence, and an attractive place to live and work.

The strategy re-affirmed the fundamental importance of excellent teaching and learning, quality in research and knowledge transfer, and effective engagement between higher education and society. In particular, it identified the challenge and opportunities that come with growing demand for higher education arising from Ireland’s demographic growth, which is relatively unique in the European context. It also recognised the need for the higher education system to be internationally networked and to perform to international benchmarks, and its role in upskilling the workforce.

The strategy made 26 recommendations, the implementation of which is in progress and is having profound effects on higher education in Ireland. The recommendations cover areas as diverse as access, knowledge transfer, institutional consolidation, the development of a sustainable funding base, institutional collaboration through regional and thematic clusters, and performance funding. The most radical recommendation, however, was that instead of considering higher education in Ireland as comprising a set of discrete institutions it should be regarded as a system that as a collective delivered higher education outputs for the country. Underpinning all the recommendations is the idea that higher education in Ireland is best understood as a collective system that delivers the higher education that Ireland needs and within which each individual institution makes its contribution in a way that is consonant with its mission (HEA, 2012). The recommendations ranged across a number of areas, but those that relate to research and engagement with wider society are of most relevance to this review.

In relation to research, the strategy recommends affording a wider focus to the researcher’s role, one that might allow for greater mobility of staff between higher education and enterprise, and increase researchers’ career opportunities. More specifically, it recommends “mobility of staff … between higher education … and enterprise and the public service … to promote knowledge flows and to capitalise on the expertise within higher education for the benefit of society and the economy”. Various mechanisms such as secondments and consultancy are suggested as being mutually beneficial to academics, their institutions, and to wider society.

The strategy also notes that in order to facilitate such collaboration and engagement between higher education and enterprise, review mechanisms and metrics are required to achieve parity of esteem across disciplines, types of research and innovation activities (including knowledge transfer and commercialisation). It also recommends embedding knowledge transfer within HEIs’ activities, which should be rewarded accordingly. In this regard, the establishment of Knowledge Transfer Ireland in 2014 (see below) is also relevant DJEI (2016).

As part of the efforts to encourage a broadening of individual researchers’ roles, the Strategy calls for HEIs to be more engaged with the wider community, and for this engagement to be embedded in their missions. The specific actions that HEIs need to take to achieve this goal are:

-

Encourage greater inward and outward mobility of staff between HEIs, business, industry, and the wider community.

-

Respond positively to the continuing professional development needs of the wider community to develop and deliver appropriate modules and programmes in a flexible and responsive way.

-

Recognise civic engagement of their students through programme accreditation as is appropriate.

-

Put in place procedures and structures that welcome and encourage the involvement of the wider community in a range of activities, including programme design and revision.

As part of these actions, the Strategy calls for the HEA to carry out a national survey of employers as part of the assessment of quality outcomes for the system. Also proposed was a coherent framework of system-wide collaboration between HEIs in so-called Regional Clusters, with a view to improving responsiveness to local and regional economic needs.

The System Performance Framework; Strategic Dialogue and institutional performance compacts

The System Performance Framework includes a set of high-level system indicators relating to the following key system objectives for 2014-16:

-

Meet Ireland’s human capital needs across the spectrum of skills through engaged institutions, a diverse mix of provision across the system and through both core funding and specifically targeted initiatives.

-

Promote access for disadvantaged groups and put in place coherent pathways from second-level education, from further education and other non-traditional entry routes.

-

Promote excellence in teaching and learning and assessment to underpin a high quality student experience.

-

Maintain an open and excellent public research system focused on the national priority areas and the achievement of other societal objectives and to maximise research collaborations and knowledge exchange between and amongst public and private sector research actors.

-

Ensure that Ireland’s HEIs will be globally competitive and internationally oriented, and Ireland will be a world-class centre of international education.

-

Reform practices and restructure the system for quality and diversity.

-

Increase accountability of autonomous institutions for public funding and against national priorities.

The rollout of the Strategic Dialogue process and the agreement of the institutional performance compacts between the HEA and each HEI is an integral element of the implementation of the System Performance Framework for Higher Education 2014-16, which sets out to align the missions, strategies and profiles of individual HEIs with national priorities. The Framework outlines a set of strategic objective indicators of success against which institutional performance can be measured and funding can be allocated. The compacts recognise that an individual HEI is an autonomous institution with a distinctive mission, operating within a regional, national and international higher education environment, while also being part of a system and contributing to overall system performance.

The Strategic Dialogue process involves annual meetings between the executive of the HEA, supported by independent national and international experts, and the executive of the individual HEIs at which their performance compact submissions and progress against targets are discussed and assessed in detail. All HEIs have engaged seriously with this process having returned completed draft compacts setting out their mission, strategies, objectives and performance targets to 2016 under all the required headings, and within the required timescale, which was challenging (HEA, 2014a).

The first round of Strategic Dialogue concentrated on agreeing the mission, profile and strategy of each HEI, taking account of its place in the landscape, agreeing the set of strategic objectives needed to implement the strategy, agreeing a set of realistic but challenging interim and final targets associated with the achievement of these objectives, together with the indicators of success by which the HEI itself proposed that it should be measured and the clear means of verification of these indicators.

In drawing up their performance compacts, the HEIs were asked to propose the qualitative and quantitative indicators against which they wished their performance to be assessed. The compacts include the following elements:

-

Establishment of the compact: provides for the establishment of the compact and its term, and for the HEA to inform of any actual or prospective changes to policy.

-

Performance funding framework: sets out the performance funding framework within which the HEA will allocate performance funding.

-

Mission and strategy statement: includes a statement of the HEI mission and strategy and also agrees to inform the HEA of any changes to its mission and profile.

-

Current and planned profile: contains the most recent profile (as supplied by the HEA) and the planned profile 2016/17 completed by the institution itself.

-

Development plans and objectives: sets out the HEI’s development plans and objectives using standardised templates. These development plans and objectives must be taken from the institution’s own properly formulated strategic plan. The quality of the HEI’s strategic planning process will be evaluated. The areas under which objectives are sought are National Strategy objectives including:

-

regional clusters

-

participation, equal access and lifelong learning

-

teaching and learning and quality of student experience

-

high quality, internationally competitive research and innovation

-

enhanced engagement with enterprise and the community and embedded knowledge exchange

-

enhanced internationalisation

-

institutional consolidation.

-

-

Annual Compliance Statement: As the Strategic Dialogue process develops, the HEA takes into account ongoing compliance of institutions, and where significant or urgent compliance issues arise, they will be discussed as part of the next Strategic Dialogue.

-

Performance Funding: a statement of the amount of performance funding allocated.

-

Agreement: confirmation of the agreement between the HEA and the HEI to be signed upon conclusion of the strategic dialogue process.

-

Appendices: includes any additional material supplied by the HEI, including details of how objectives might be objectively verified.

An element of performance-related funding was introduced primarily based on the quality of the HEIs’ engagement with the reformed performance governance system. As a signalling measure, a limited amount of performance funding of EUR 5 million was reserved from the allocation of the 2014 recurrent grant to HEIs to be released subject to satisfactory engagement with the Strategic Dialogue process. In the allocation of this funding the HEA was cognisant that this was the first year of Strategic Dialogue and that this was a developmental and learning stage for all involved.

In the allocation of performance funding for subsequent years, the HEA will have to consider the agreed outcomes from the current year’s dialogue process. For this, each HEI will have to include not only specific objectives and indicators proposed within the compacts, but also responses to general and specific feedback given to HEIs by the HEA regarding the overall content and quality of compacts. The HEIs will be expected to demonstrate that they have incorporated any feedback into their processes for the next annual review cycle.

Moving to a system-level approach to higher education

Restructuring of the Irish higher education system has also been progressed with the aim of creating a more coherent system of mission-diverse, complementary, and highly collaborative institutions in which the diversity and areas of high quality performance that were already evident would be maintained and strengthened. The major components of restructuring are:

-

The establishment of a set of Regional Clusters, the governance of which should be kept light and flexible and not dilute the accountability or autonomy of the HEIs; with strategic objectives which are clear, simple and well prioritised and focus, in the first instance, on shared academic planning and improved student pathways.

-

The implementation of the recommendations of the Initial Teacher Education Review on the formation of providers of initial teacher education into six centres – through mergers and collaborations, integrating teacher education provision across all levels of education from early childhood to adult education. This process is research-led and university based.

-

The establishment of a process by which consortia of IOTs that meet the requirements can apply for designation as technological universities. A core objective will, therefore, be to protect and enhance the role of the IOT sector in supporting enterprise, underpinning diversity and promoting access and participation.

-

The strengthening of existing strategic alliances between HEIs in ways that protect and enhance the distinctiveness of their missions.

The Regional Cluster initiative

To aid the implementation of the National Strategy for Higher Education to 2030, Regional Clusters of HEIs were developed to assist in achieving the core objectives of a high-quality, sustainable, competitive higher education system. The aim was to build up the collective capacity, and capability of Irish higher education, to enhance quality and efficiency, to support higher education’s role in the regional innovation system and, thus to strengthen international competitiveness. The HEA was responsible for steering the overall process development through the Strategic Dialogue process. Overall the response from HEIs was good given that the reorientation of internal systems and structures to take greater account of external, regional forces was both time-consuming and challenging. In total, five Regional Clusters were developed: Dublin/Leinster I, Dublin/Leinster II, West/North West, the Shannon Consortium (see Chapter 3), and the South.

The evolution of successful and sustainable regional clusters of HEIs can depend upon a symbiotic approach, encompassing, on the one hand, inward-facing groupings of proximate HEIs which, working together, can best optimise their collective impact in terms of effectiveness, efficiency, quality and competitiveness and, on the other hand, outward-facing groupings of HEIs interacting with regional agencies/external stakeholders to meet national and regional economic needs, and position the region as a self-reinforcing knowledge hub that is internationally attractive, socially beneficial, and economically successful. The further development of the Regional Clusters and the next generation of regional collaborative fora (e.g. Regional Skills Fora) are discussed in further detail in Chapter 3 of this report.

Technological universities

The National Strategy provides for the establishment of a new type of university – a technological university. Internationally, a technological university is a higher education institution that operates at the highest academic level in an environment that is specifically focused on technology and its application. A technological university is distinguished from existing universities by a mission and ethos that are faithful to and safeguard the current ethos and mission focus of the institutes of technology. These are based on career-focused higher education and on industry-focused research and innovation – this will have to be taken to a higher level in a technological university.

A technological university will also be expected to play a pivotal role in facilitating access and progression (particularly of the workforce) through strengthening existing relationships between higher education, providers of further education and training and proximate employers. In a technological university, the fields of learning will be closely related to labour market skill needs with a particular focus on programmes in science, engineering and technology and including an emphasis on workplace learning.

The mission of these new institutions “…will have a systematic focus on the preparation of graduates for complex professional roles in a changing technological world” (HEA, 2012) thus maintaining distinctiveness between universities, technological universities and institutes of technology. It will advance knowledge through research and scholarship and disseminate this knowledge to meet the needs of society and enterprise. It shall have particular regard to the needs of the region in which the university is located. Consolidation via merger is a central element of the process.

Institutes of Technology proposing to become technological universities must be able to establish that they are operating at a level equivalent to a technological university as set out in the Technological Universities Bill 2015. To date, four expressions of interest have been received by the HEA. In determining whether an application for designation as a technological university should be approved, the HEA is supported by international panels of experts who will carry out site visits and reviews as appropriate.2

Ireland’s national innovation system

As Forfás, the former national policy advisory board for enterprise, trade, science, technology and innovation in Ireland, noted in its “Evaluation of Enterprise Supports for Research, Development and Innovation” of 2013, the country has made significant progress over the previous decade and established an international reputation in key research areas; collaboration between HEIs and industry has increased, with resulting economic benefit; and there has been an increase in business expenditure on research and development (Forfás, 2013). The report, however, also emphasised the need for continued investment in Ireland’s innovation system, pointing out that it was weaker than benchmark countries such as Austria, Denmark, Sweden and Switzerland. The key challenges identified in the report were to increase the scale and depth of R&D activity in firms, to commercialise state-funded academic research, and to connect industry with HEI research and vice versa.

Innovation 2020 is Ireland’s current five-year strategy for research and development, science and technology published in December 2015. It provides a whole-of-government approach to research and innovation, building on the progress made to date in the research and innovation system, addressing identified challenges, and advancing fresh strategic ideas to distinguish Ireland globally through its ability to make research work to maximum effect for the country. Its aim is to leverage a vibrant public research base in order to develop the skills base necessary to build a sustainable and resilient society, to create employment, and to establish innovative companies that will succeed internationally. A key ambition is to increase total investment in R&D in Ireland, led by the private sector, to 2.5% of gross national product. It also aims to build on existing infrastructures and achieve ambitious private-public collaborations.

Public investment in technology transfer for the period 2007-16 amounted to EUR 52 million and is focused on providing a streamlined process that delivers effective commercialisation of research (DES, 2015). Various agencies provide funding for research personnel and infrastructure, R&D activities, commercialisation and international networking. The key activities of Enterprise Ireland, Knowledge Transfer Ireland, Science Foundation Ireland, the Irish Research Council, and IDA Ireland (formerly the Industrial Development Authority), are outlined below.

Key state agencies

Enterprise Ireland

Enterprise Ireland (EI) plays a key role in the commercialisation of research. The agency provides a range of supports for both companies and research performing organisations to develop new technologies and processes that will lead to job creation and increased exports. It also has a number of supports to directly assist companies with research and innovation activities. Enterprise Ireland provides support relevant to all stages of company development, enabling companies to progress from undertaking an initial research project to higher level innovation and R&D activities. This includes in-company supports, collaboration supports, and supports for realising commercial potential (Table 1.8). Enterprise Ireland has recently published a new Strategy (Enterprise Ireland, 2017) which underlines the importance of driving innovation in Irish enterprise through new supports to reach the target of EUR 1.25 billion in R&D expenditure per annum by 2020. The Strategy emphasises the importance of innovation in the context of the Brexit decision in the UK. Implementation of the Strategy will see new innovation supports for companies and implementation of a new Innovation Toolkit to support client companies to identify innovation opportunities.

Through the Technology Transfer Strengthening Initiative (TTSI), Enterprise Ireland has invested in developing the capability and capacity for knowledge transfer and commercialisation in research performing organisations. The HEIs provide dedicated resources to knowledge transfer and commercialisation, ranging from a full technology transfer office (TTO) within a larger HEI to an individual working part-time in a smaller institution. The HEIs refer to this function in a variety of ways, such as “technology transfer”, “industrial liaison”, “knowledge exchange” or “innovation office”, but all offer activities such as intellectual property management, licensing, partnering, consultancy and support for the creation of new companies. For the smaller IOTs, this activity is supported by the TTSI programme consortium lead partner.

Knowledge Transfer Ireland

Knowledge Transfer Ireland (KTI) was established in late 2013 as a partnership between Enterprise Ireland and the Irish Universities Association. KTI acts as a national office for technology transfer and plays a key role in the country’s innovation system by providing a responsive interface between companies and the higher education system. KTI’s mission is to maximise innovation from state-funded research, by getting technology, ideas and expertise into the hands of business, swiftly and easily for the benefit of the public and the economy. One of the many functions is the provision of a central hub that enables companies to explore, through a web interface, the research resources available to them throughout Ireland. KTI also has a role in allocating and managing funding to support knowledge transfer offices within Ireland’s HEIs and state-funded research organisations.

Science Foundation Ireland

Science Foundation Ireland (SFI) was established in 2003 as the national foundation for investment in excellent scientific and engineering research. SFI invests in STEM academic researchers and research teams who are likely to generate new knowledge and leading-edge technologies or start up competitive enterprises. In order to fully support research prioritisation, SFI’s mandate has been expanded to allow for funding the full continuum of research, applied as well as basic oriented, across all of the 14 priority research areas. SFI has several programmes that support HEI-industry relationships, including the following:

-

SFI Industry Fellowships facilitate the placement of researchers in industry or academia to stimulate excellence through knowledge transfer and training. Fellowships enable researchers to access new technology pathways and standards, and facilitate training in the use of specialist research infrastructure.

-

SFI Partnerships provide funding for ambitious research projects between industry and academia, enabling industry to engage with world-class academic researchers and gain access to infrastructure and intellectual property using a shared-risk funding model.

-

SFI Research Centres consolidate the activities of public research organisations to create a critical mass of leading researchers in strategic areas. The Centres are part-funded (minimum 30%) by industry, and this ensures that there is an effective and productive partnership between academia and industry. Some 300 industry partners are involved – approximately 150 each from the multinational and indigenous sectors.

-

SFI Research Centre Spokes Programme provides a mechanism for new industry partners to join the existing SFI Research Centres.

-

SFI Technology Innovation Development Award provides funding to support researchers to develop entrepreneurial skills and to enable them to focus on the initial stages of developing a new or innovative technology, product, process or service with strong commercial potential. This programme, funded by SFI, is run in partnership with Enterprise Ireland.

-

SFI Academic-Led Programmes support research, employing a broad portfolio of funding mechanisms, with the potential for economic and societal impact. Academic-led programmes, such as the SFI Investigators Programme, the SFI Future Research Leaders Award and the SFI Starting Investigator Grant address research questions and provide recruitment and career development opportunities in Ireland. SFI also provides a number of incentives to encourage applicants to apply to the European Research Council.

The Irish Research Council

The Irish Research Council (IRC) was established in 2012 from a merger of the Irish Research Council for Humanities and Social Sciences and the Irish Research Council for Science, Engineering and Technology. It operates under the aegis of the HEA. IRC operates a suite of interlinked research schemes, in particular at postgraduate and early stage postdoctoral researcher levels. IRC is responsible for funding research within and between all disciplines, and supporting the education and skills development of excellent early-stage researchers. Currently, approximately two-thirds of the IRC funding is allocated to the STEM areas. A capacity building scheme enables researchers to develop their track record and stimulate applications for European research funding, including from the European Research Council and the Horizon 2020 Societal Challenges. The IRC also has a partnership with government departments to enhance the evidence and knowledge base for a diverse range of themes. Two support programmes are directed to enhance industry mobility of early-stage researchers (Table 1.9).

IDA Ireland

IDA Ireland plays a key role in attracting high-value R&D investments to Ireland by promoting collaboration between industry, academia, government agencies and regulatory authorities. The agency funds in-company R&D and identifies support opportunities from other funding organisations. The R&D fund provides grant-aid to clients establishing new R&D facilities, expanding existing ones, or embarking on R&D projects. The strengthening of Ireland’s research ecosystem in recent years has enabled IDA Ireland to attract increased levels of high-value R&D projects, which qualitatively transform and deepen the roots of key multinational corporations in the country.

Enhancing the role of education in innovation and entrepreneurship

The 2014 National Policy Statement on Entrepreneurship in Ireland (DJEI, 2014) identified several potential roles for education institutions in supporting entrepreneurship and innovation. These include i) embedding the development of entrepreneurship in the education system across all levels of education; ii) increasing the number of professionals in information and communications technology (ICT); and iii) developing the appropriate infrastructure to support technology transfer into industry. Some of the more recent initiatives with a focus on higher education are described below and will be discussed further in Chapters 3, 4and 5.

Engagement with enterprise and society

The HEA recently published a report on the HEI engagement activities with enterprise and society, which sets out how it aims to support implementation of the National Strategy for Higher Education to 2030 and the system-wide reform and development programme (HEA, 2015). The aim is to organise a step-change in the scale and quality of partnerships between higher education and the enterprise community in all regions of the country. It builds on a range of initiatives and practices that are already in place between higher education and enterprise, targeted national talent development initiatives and several local and regional partnerships between education providers and individual companies. Implementation of this engagement strategy has been incorporated into the implementation of the National Skills Strategy (DES 2016) which has a strong focus on entrepreneurship and employer participation in the development of skills.

Labour market activation initiatives

Aside from standard entry routes to higher education, there has been an increased focus in recent years on labour market activation programmes that are directly linked to enterprise and industry needs. Examples include the ICT Skills Action Plan and the Springboard Programme, both of which are administered by the HEA on behalf of the DES.

The first ICT Skills Action Plan was published in 2012 as a collaborative industry-government approach to increasing the domestic supply of high-level ICT graduates. The latest plan includes an ambition to make Ireland a global leader for ICT talent and skills, with the education system satisfying 74% of the forecast industry demand for high-level ICT skills by 2018 (up from the current level, estimated at over 60%). An updated ICT Skills Action Plan is expected to be published in 2017.

To address the emerging skills gaps, the current Plan’s key targets include doubling the output of Level 8 graduates by 2018 and interim steps to increase supply through conversion and reskilling programmes. Significant progress has been made in meeting these targets. The Plan also includes measures to attract highly skilled ICT professionals from abroad to augment the domestic supply. These measures include streamlining the operation of the employment permit regime and promoting Ireland as a destination for skilled ICT professionals. Industry’s continued upskilling and development of its current employees will also make a vital contribution to the achievement of the Plan’s goals.

The Springboard+ Programme is a recent labour market activation initiative administered by the HEA on behalf of the DES. It provides recently unemployed people with free higher education opportunities, giving them the opportunity to reskill and return to work. Springboard+ courses are provided in areas identified as those where there is a shortage of skills and/or strong growth leading to potential skills shortages. Each course aims to cross-skill or up-skill participants to enable them to restart their careers, and to provide a pipeline of graduates for enterprise sectors that are growing and expanding. The Springboard Programme has been running since 2011 and was renamed Springboard+ in 2014 and saw the incorporation of a standalone ICT Skills Conversion programme under the Springboard branding. The full-time ICT Conversion programmes have been open to all applicants regardless of employment status. In 2016, a new part-time ICT Conversion programme was introduced as part of the Springboard+ 2016 call. Over 30 000 people have completed courses to date with an average of 6 000 free places available per academic year. Over 90% of the 2015/16 courses (excluding entrepreneurship courses) include work placements, and employers see such work experience as a useful complement to course studies. The HEA has built a rigorous evaluation framework into the initiative, including publishing process evaluations and reporting on outcomes to date. Three comprehensive evaluations of outcomes have been published to date, with participants and graduates, with the HEIs involved, and with enterprise (HEA, 2017b). The evaluations show that, within two years of completing a course, 60% of graduates are back in employment or self-employment.

Action Plans for Jobs

Since 2012, a series of Action Plans for Jobs has acted as key policy instrument to supporting job creation and enterprise growth. Each year, these documents set out a series of commitments to be delivered under a number of thematic headings. So far, over 1 000 actions have been implemented and the original target to support the creation of 100 000 new jobs by 2016 has been exceeded with nearly 190 000 more people now at work.3 Actions to align skills provision with the needs of enterprise have been a feature of every plan so far.

Building on the success of the national Action Plans for Jobs, a series of eight regional Action Plans for Jobs was developed in 2015 with the aim of distributing job creation more evenly across the country for the period 2015-17. Both the national and the regional Action Plans have been developed with extensive stakeholder consultation, including engagement with state agencies, local government, education providers (both further and higher education), industry, and business representatives (DJEI, 2017).

The National Skills Strategy and Regional Skills Fora

The Department of Education and Skills has developed the National Skills Strategy 2025 (DES, 2016). The purpose is to provide a framework for skills development that will help drive Ireland’s growth both economically and societally over the next decade. It sets out a wide range of actions under six key objectives, aimed at improving the development, supply and use of skills over the next decade.

The National Skills Strategy also provides for the establishment of the National Skills Council that will oversee research, forecasting and prioritisation of skills needs in the economy, and nine so-called Regional Skills Fora, which bring together employers and the education and training system in each region to facilitate the planning and delivery of programmes, to reduce duplication, and to inform national funding decisions. The Regional Skills Fora have been effective in raising the awareness of the range of programmes on offer across a region and how these can be accessed.

Developing entrepreneurial mindsets

There is a joint understanding and commitment across all policy makers that manifestations of entrepreneurial mindsets in the form of enterprise4 and entrepreneurship are crucial for addressing broader policy objectives through innovation and partnership – tackling grand global challenges, such as sustainable energy, healthy ageing and smart cities (DJEI, 2015b; DES, 2016). The National Skills Strategy provides for the completion of an Entrepreneurship Education Policy Statement that will inform the development of entrepreneurship education guidelines for schools. It also provides for the pilot and support of Makerspaces, Fab labs and innovative summer camp ideas to promote entrepreneurial thinking, STEM and design skills amongst secondary school students.

National networks to enhance enterprise and entrepreneurship in higher education

Recently, several networks have been forming across the Irish HEIs to promote and develop enterprise and entrepreneurship. CEEN, the Campus Entrepreneurship Enterprise Network, is one of them. CEEN aims to create a sustainable national platform for raising the profile of entrepreneurship, extending engagement and further developing entrepreneurship across Irish HEIs. It will do this by providing a vehicle for a national dialogue between academia, industry and voluntary and public sectors on the development of entrepreneurship education, promoting excellence in the field by stimulating research, developing new pedagogy, evaluating and disseminating good practice initiatives, and facilitating the networking and collaboration within and between HEIs. Examples of CEEN’s projects include the National Educators Programme, the Engaged Student Project, Entrepreneurship Scholarship Scheme, and the Spark Social Enterprise Awards (CEEN, 2017).

Entrepreneurship education activities in Irish HEIs

Most HEIs in Ireland are targeting a very significant development and embedding of entrepreneurship education in programmes at both undergraduate and at postgraduate level. Table 1.10 gives an overview of current initiatives which were included in the institutional compacts presented in 2016.

References

CEEN (2017), “Campus Entrepreneurship Enterprise Network” website, www.ceen.ie/ (accessed 11 February 2017).

Department of Education and Skills (2011), National Strategy for Higher Education to 2030, published online, www.hea.ie/sites/default/files/national_strategy_for_higher_education_2030.pdf (accessed 11 February 2017).

Department of Education and Skills (2015), Country Background Report Ireland, prepared for the HEInnovate Ireland country review, unpublished report submitted to the OECD.

Department for Education and Skills (2016), National Skills Strategy 2025 – Ireland’s Future, published online, www.education.ie/en/Publications/Policy-Reports/pub_national_skills_strategy_2025.pdf (accessed 11 February 2017).

Department of Enterprise, Jobs and Innovation (2013), Survey of Research & Development in the Higher Education Sector 2012/2013, published online, www.djei.ie/en/Publications/Publication-files/Survey-of-Research-and-Development-in-the-Higher-Education-Sector-2012-2013.pdf (accessed 11 February 2017).

Department of Enterprise, Jobs and Innovation (2014), National Policy Statement on Entrepreneurship in Ireland, published online, www.localenterprise.ie/Documents-and-Publications/Entrepreneurship-in-Ireland-2014.pdf (accessed 11 February 2017).

Department for Jobs, Enterprise and Innovation (2015a), Survey of Research & Development in the Higher Education Sector 2012/2013, published online, www.djei.ie/en/Publications/Publication-files/Survey-of-Research-and-Development-in-the-Higher-Education-Sector-2012-2013.pdf (accessed 11 February 2017).

Department of Enterprise, Jobs and Innovation (2015b), Enterprise 2025 – Ireland’s National Enterprise Policy 2015-2025, published online, www.djei.ie/en/Publications/Publication-files/Enterprise-2025-Summary-Report.pdf (accessed 11 February 2017).

Department of Enterprise, Jobs and Innovation (2016), Inspiring Partnership – The National IP Protocol 2016. Policies and resources to help industry make good use of public research in Ireland, published online, www.knowledgetransferireland.com/ManagingIP/KTI-Protocol-2016.pdf (accessed 11 February 2017).

Department of Enterprise, Jobs and Innovation (2017), “Action Plan for Jobs” website, www.actionplanfor jobs.ie/ (accessed 11 February 2017).

Enterprise Ireland (2016), Strategy 2017-2020, published online, https://enterprise-ireland.com/en/Publications/Reports-Published-Strategies/Strategy-2017-to-2020.pdf, (accessed 11 February 2017).

European University Association (2013), Financially Sustainable Universities. Full Costing: Progress and Practice, EUA Publishing, Brussels.

Forfás (2013), Evaluation of Enterprise Supports for Research, Development and Innovation, published online, www.djei.ie/en/Publications/Publication-files/Forf%C3%A1s/Evaluation-of-Enterprise-Supports-for-Research-Development-and-Innovation.pdf (accessed 11 February 2017).

Higher Education Authority (2012), Towards a Future Higher Education Landscape, published online, www.9thlevel.ie/wp-content/uploads/TowardsaFutureHigherEducationLandscape.pdf (accessed 11 February 2017).

Higher Education Authority (2014a), Higher Education System Performance. First Report 2014-2016. Report of the Higher Education Authority to the Minister for Education and Skills, published online, www.education.ie/en/Publications/Education-Reports/Higher-Education-System-Performance-First-report-2014-2016.pdf (accessed 11 February 2017).

Higher Education Authority (2014b), Review of Workload Allocation Models in Irish Higher Education Institutions, Higher Education Authority, Dublin.

Higher Education Authority (2015), Collaborating for Talent and Growth: Strategy for Higher Education – Enterprise Engagement 2015-2020, published online, www.hea.ie/sites/default/files/hea_collaborating_for_talent_and_ growth_strategy_he-enterprise_june_2015.pdf (accessed 11 February 2017).

Higher Education Authority (2016a), Investing in National Ambition: A Strategy for Funding Higher Education. Report of the expert group on future funding for higher education, published online, www.education.ie/en/Publications/Policy-Reports/Investing-in-National-Ambition-A-Strategy-for-Funding-Higher-Education.pdf,(accessed 11 February 2017).

Higher Education Authority (2016b), Financial Review of the Institutes of Technology, published online, www.hea.ie/sites/default/files/final_iot_financial_review_3_11.pdf (accessed 11 February 2017).

Higher Education Authority Ireland (2017a), “Student enrolment numbers” website, www.hea.ie/node/1557 (accessed 11 February 2017).

Higher Education Authority (2017b), “Springboard Programme” website, www.springboardcourses.ie (accessed 11 February 2017).

Notes

← 1. An association of private for-profit providers, the Higher Education Colleges Association (HECA, www.heca.ie) has a list of affiliated members on its website, but this is not an exhaustive list.

← 2. The designation process consists of four stages as follows: i) expression of interest; ii) preparation of a plan to meet the criteria; iii) evaluation of the plan, iv) an application for designation.

← 3. The Action Plan for Jobs 2012 included an ambition to create 100 000 jobs by 2016.

← 4. Enterprise here refers to entrepreneurial skills in the broader sense which are also important for developing skills in the future workforce to ensure they make the maximum contribution to productivity and growth in public, private and third sector organisations.