Chapter 1. The teaching profession and its knowledge base1

This chapter outlines the context for investigating teacher knowledge by providing a brief overview of the teaching profession. First, we summarise some of the sociological literature on professions, including how professions have been conceptualised, what their main attributes are and how teaching is seen within these approaches. Second, we review the main factors that have exerted influence on the status of the teaching profession such as autonomy, governance, self-regulation and teacher education. These reflections prompt questions on teachers’ scientific knowledge base, their professional competence and how the two are related. Questions raised in this introduction provide the rationale for this publication: the need to derive evidence-informed suggestions for educational policy and future research by examining the current state of teachers’ pedagogical knowledge and implications for the instructional process.

To introduce the major policy and research issues concerning teachers and knowledge, this chapter provides the reader with a contextual overview of the teaching profession. Scholars from different fields have been trying to operationalise what a profession is and what its attributes are. The status of teaching as a profession has been largely debated. This chapter is not meant to provide an extensive review of literature; rather it introduces some of the arguments in this debated field and thus serves as a rationale for investigating teachers’ pedagogical knowledge as a component of professional competence.

Contextualising the teaching profession

In recent decades the teaching profession has been on the policy agenda of most OECD countries and partner economies. Some of the key issues include how to attract motivated and high-achieving candidates to the profession, how to retain quality teachers and how to improve initial teacher education and professional development. The teacher clearly contributes to student learning and achievement, and the empirical research base showing the value of high quality teachers in learning outcomes is growing. For example, even after accounting for prior student learning and family background characteristics, several studies indicate that teacher quality is an important factor in determining gains in student achievement (Darling-Hammond, 2000; Hanushek, Kain and Rivkin, 1998; Muñoz, Prather and Stronge, 2011; Wright, Horn and Sanders, 1997).

Often, the status of the profession has been implicated in the recent challenge in recruiting and retaining good teachers. The teaching profession is perceived to have a lower status than other professions such as medicine, law or engineering (Ingersoll and Merill, 2011). However, defining what is meant by the status of a profession in general, and the status of the teaching profession in particular has long been debated. In 1966, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) and the International Labour Organisation (ILO) addressed the importance of the status of the teaching profession. The publication “The ILO/UNESCO Recommendation concerning the Status of Teachers” states that:

“the expression ‘status’ as used in relation to teachers means both the standing or regard accorded them, as evidenced by the level of appreciation of the importance of their function and of their competence in performing it, and the working conditions, remuneration and other material benefits accorded them relative to other professional groups.” (UNESCO/ILO, 2008: 21).

Commonly, the word “status” is used as a generic term to indicate social standing. Scholars, however, have proposed to operationalise the concept by decomposing it. For example, Hoyle (1995a; 2001) proposes to distinguish occupational status from occupational prestige and esteem. According to Hoyle (2001), occupational status is the category to which knowledgeable groups (e.g. politicians, sociologists) allocate an occupation. On the other hand, occupational prestige is “the public perception of the relative position of an occupation in a hierarchy of occupations” (Hoyle, 2001: 139), whereas occupational esteem is “the regard in which an occupation is held by the general public by virtue of the personal qualities which members are perceived as bringing to their core task” (Hoyle, 2001: 147). In their usage of the word, UNESCO/ILO appear to be referring to the concepts of prestige and esteem.

Status is a relative concept and shows cross-cultural variation (Hargreaves, 2009). In the review which follows, we show that the status of the teaching profession is closely linked to whether teaching is (or is not) acknowledged as a profession. Sociologists have been interested in the study of professions for a long time, and we briefly review some of this debate as it relates to teaching, before returning to discussing the status of the teaching profession specifically.

What is a profession?

There are different approaches to characterising professions and those that are based on determining criteria may emphasise different elements. Many scholars have written about the distinction between professions and semi-professions, and for one reason or another, some have characterised teaching as a semi-profession (e.g. Hoyle, 2001; Howsam et al., 1985; Krejsler, 2005; Ingersoll and Merrill, 2011). For example, Howsam et al. (1985), who use a taxonomic approach to defining professions, conclude that teaching is a semi-profession because it does not have all the characteristics of a profession, as illustrated in Box 1.1.

-

Professions are occupationally related social institutions established and maintained as a means of providing essential services to the individual and society.

-

Each profession is concerned with an identified area of need or function (e.g. maintenance of physical and emotional health, preservation of rights and freedom, enhancing the opportunity to learn).

-

Collectively and individually the profession possesses a body of knowledge and a repertoire of behaviours and skills (professional culture) needed in the practice of the profession; such knowledge, behaviour and skills normally are not possessed by the non-professional.

-

The members of the profession are involved in decision making in the service of the client, the decisions being made in accordance with the most valid knowledge available, against a background of principles and theories, and within the context of possible impact on other related conditions or decisions.

-

The profession is based on one or more underlying disciplines from which it draws basic insights and upon which it builds its own applied knowledge and skills.

-

The profession is organised into one or more professional associations which, within broad limits of social accountability, are granted autonomy in control of the actual work of the profession and the conditions which surround it (admissions, educational standards, examination and licensing, career line, ethical and performance standards, professional discipline).

-

The profession has agreed-upon performance standards for admission to the profession and for continuance within it.

-

Preparation for and induction to the profession is provided through a protracted preparation programme, usually in a professional school on a college or university campus.

-

There is a high level of public trust and confidence in the profession and in individual practitioners, based upon the profession’s demonstrated capacity to provide service markedly beyond that which would otherwise be available.

-

Individual practitioners are characterised by a strong service motivation and lifetime commitment to competence.

-

Authority to practice in any individual case derives from the client or the employing organisation; accountability for the competence of professional practice within the particular case is to the profession itself.

-

There is relative freedom from direct on-the-job supervision and from direct public evaluation of the individual practitioner. The professional accepts responsibility in the name of his or her profession and is accountable through his or her profession to the society.

Source: Howsam, R. B., et al. (1985), “Educating a profession”, http://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED270430.

Professions and semi professions

Howsam et al. (1985) classify teaching as a semi-profession because it lacks one of the main identifying characteristics of a full profession: professional expertise. They argue that teaching lacks a common body of knowledge, practices and skills that constitute the basis for professional expertise and decision-making. This is a consequence of the practice of teaching not being founded upon validated principles and theories. In their view, few teachers use existing scientific knowledge, nor do they contribute to building a scientific knowledge base through the development of principles, concepts and theories or to validating practices. As a consequence, there are no agreed-upon performance standards for evaluating teachers to continue in the profession. Importantly, the quality of the preparation of teachers and induction into the profession is poor as a consequence of the absence of a common body of scientific knowledge underpinning professional expertise and transmitted via teacher educators during initial teacher education.

Likewise, Hoyle (1995b) argues that teaching satisfies some but not all criteria of a profession. His defining criteria, also within a taxonomic perspective, are somewhat different from those of Howsam et al., but there are some important similarities. For example, in characterising full professions, Hoyle (1995b: 12) argues that “although knowledge gained through experience is important, this recipe-type knowledge is insufficient to meet professional demands and the practitioner has to draw on a body of systematic knowledge”. Furthermore, in the case of professions, the acquisition of knowledge and development of specific skills requires a lengthy period of higher education and training, during which the practitioner undergoes a process of socialisation to the professional values, centred on the client’s interests and made explicit through a code of ethics. Like Howsam et al., Hoyle considers decision-making to be an important characteristic of professions because professions require the practice of skills in situations that are not routine and where professional judgement, based on a systematised body of knowledge, will need to be exercised when encountering new problems. Both scholars stress the importance of autonomy over professional judgement regarding daily practice, as well as autonomy over control of regulating the profession, such as the setting of admissions criteria, performance standards and licensing.

A semi-profession meets some, but not all, of the criteria for professions. For example, Etzioni (1969) describes semi-professions as occupations where training is shorter, status tends to be less legitimated, there is a less established right to privileged communication, a less specialised body of knowledge and less autonomy from supervision or societal control than professions. In some cases, semi-professions are occupations that are in the process of becoming professions through a process known as “professionalisation”. This process refers to achieving the status of a profession (Evetts, 2012), or “the degree to which occupations exhibit the structural or sociological attributes, characteristics and criteria identified with the professional model” (Ingersoll and Merrill, 2011: 186). Box 1.2 illustrates the characteristics of semi-professions as proposed by Howsam et al. who compiled the characteristics from various sources.

-

Lower in occupational status.

-

Shorter training periods.

-

Lack of societal acceptance that the nature of the service and/or the level of expertise justifies the autonomy which is granted to the professions.

-

A less specialised and less highly developed body of knowledge and skills.

-

Markedly less emphasis on theoretical and conceptual bases for practice.

-

A tendency for the professional to identify with the employment institution more and with the profession less. (This difference is not due to the condition of employment, but to the identity of the practitioners.)

-

More subject to administrative and supervisory surveillance and control.

-

Less autonomy in professional decision-making with accountability to superiors rather than to the profession.

-

Management of organisations within which semi-professions are employed by persons who have themselves been prepared and served in that semi-profession.

-

Absence of the right of privileged communication between client and professional.

Source: Howsam, R. B., et al. (1985), “Educating a profession”, http://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED270430

The concept of professionalism

Defining when an occupation is or is not a profession is closely related to the discourse of professionalism. For example, Freidson (2001) names two basic assumptions underlying the professionalism of an occupation: (1) unique and specialised tasks that can only be performed by members of the occupation who have the required formal training and experience and (2) work that cannot be standardised, rationalised or commodified. Freidson (2001: 2) defines professionalism as a “set of interconnected institutions providing economic support and social organisation that sustains the occupational control of [the] work”. Professionalism exists “when the organized occupation gains the power to determine who is qualified to perform a defined set of tasks, to prevent all others from performing that work, and to control the criteria by which to evaluate performance” (Freidson, 2001: 12). The ideal elements of professionalism as proposed by Freidson are illustrated in Box 1.3.

-

Specialised work in the officially recognised economy that is believed to be grounded in a body of theoretically based, discretionary knowledge and skill and that is accordingly given special status in the labour force

-

exclusive jurisdiction in a particular division of labour created and controlled by occupational negotiation

-

a sheltered position in both external and internal labour markets that is based on qualifying credentials created by the occupation

-

a formal training programme lying outside the labour market that produces the qualifying credentials, which is controlled by the occupation and associated with higher education

-

an ideology that asserts greater commitment to doing good work than to economic gain and to the quality rather than the economic efficiency of work.

Source: Freidson, E, (2001), Professionalism, the Third Logic, Polity, Cambridge.

The concept of professionalism can also be used to describe the attitudes and psychological attributes of members of a profession or of those aspiring to be professionals (Ingersoll and Merrill, 2011). Pratte and Rury (1991, as cited in Shon, 2006: 4) define professionalism as “an ideal to which individuals and occupational groups aspire in order to distinguish themselves from other workers”. Thus, professionalism could be perceived as an occupational value.

Hargreaves (2000) investigated the historical processes underlying the development of teacher professionalism among several different countries and identified four phases: the pre-professional age, the age of the autonomous professional, the age of the collegial professional and the age of the post-professional or postmodern professional. Teaching in the pre-professional era was considered to be “technically simple”. It employed the transmission method of teaching, and training occurred through apprenticeships by observing more experienced teachers. Beginning in the 1960s, during the age of the autonomous professional, teacher salaries increased and teacher education was increasingly based on university courses. Teaching practice and classroom pedagogy became subjects of inquiry. During the age of the collegial professional, beginning in the 1980s, teachers became members of professional communities. Teachers participated in professional collaborations and teacher education was moved to universities. However, the 1980s also saw the introduction of educational reforms and increasing complexity in education governance. By consequence, teachers’ roles and responsibilities began to change. The current post-professional age is being influenced by economics, globalisation and digital communication, and these changes are bringing further uncertainty to teachers’ professionalism. As a consequence, the status of the teaching profession, as it relates both to its prestige as well as to its governance, is being influenced by various factors, including sociological, political, cultural and economic ones.

The status of the teaching profession

The above review suggests that one reason the status, or social standing, of the teaching profession is difficult to define could be due to teaching being placed more along the lines of a semi-profession than a profession. There are several interrelated core characteristics of professions which are not necessarily apparent in the teaching profession: (1) a profession-specific, systematised and scientific body of knowledge that informs the daily activities of practitioners; (2) a lengthy period of higher education training and induction, and continuous professional development and (3) autonomy, both in connection with the right to exercise professional judgement and decision-making in practice and in governance over the profession. These three characteristics are at the heart of a profession. At the same time, new scientific knowledge is continuously incorporated into the profession often by practitioners themselves, as they have the expertise for evaluating the applicability of new research for practice. Due to their specialised knowledge and lengthy training, the practitioner is granted the freedom, autonomy and trust to decide on the most appropriate course of action by members of society, as well as self-regulation and autonomy over governance. Governance and self-regulation seem to be closely associated with professional autonomy, and it can be argued that a profession that does not have control over itself is by consequence less prestigious.

Teaching governance and autonomy

Indeed, issues of governance and self-regulation are two factors that have exerted a strong (often negative) influence on the status of the teaching profession in recent years. Hargreaves (2000) argues that, up until the collegial era, the occupational changes in teaching had been moving toward increasing teacher autonomy and by consequence teacher professionalism. However, since then and continuing today, the intensification of educational reforms and governance structures that are becoming increasingly more complex are eroding teachers’ autonomy, resulting in a path towards the de-professionalisation of teaching. Some argue that teachers have lost whatever autonomy they might have had in decision-making over pedagogical theory and their classrooms and have become functionaries or employees of hierarchical organisations (Lortie, 1975 in Biddle, 1995). Performance-based compensation schemes are an example of how teachers are perceived as employees who are expected to achieve certain outcomes in order to earn their salaries. Other evidence suggests, to the contrary, that recent decentralisation trends increase schools’ autonomy and also enlarges professional autonomy of teachers (Burns and Köster, 2016). Regardless of these arguments, a number of scholars have similarly argued that autonomy is one of the basic elements of teacher professionalism (Whitty, 2008; OECD, 2016a) and one of the key identifying characteristics of a profession (e.g. Etzioni, 1969; Hoyle, 1995b; Howsam et al., 1985; Reagan, 2010).

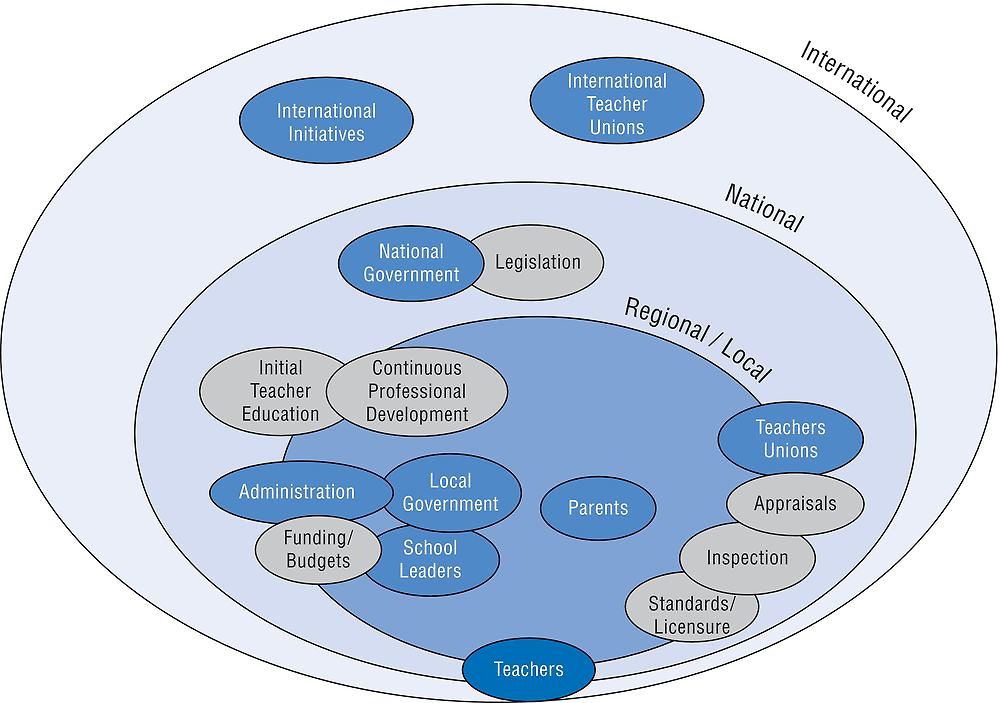

The extent of autonomy in the teaching profession is context dependent and varies both between and within countries. Within each context, the extent of autonomy granted to teachers will be the result of how the profession is governed at local or regional, national and international levels, and in the case of the teaching profession, its governance is dependent on the governance of education as whole. To illustrate the complexity involved in the governance of the teaching profession, Figure 1.1 displays some of the major factors (and this is not an exhaustive set) that come into play in the governance of the profession – much of them having to do with the increase in accountability of education systems in recent decades. For example, the extent of decision-making power that teachers have over factors such as school inspections, teacher appraisal, performance standards, credentialing and licensure, will determine the degree of autonomy teachers have over their profession in their context. According to Hargreaves and Flutter (2013), the increasing emphasis on accountability through national or international tests of student performance is likely to influence the status of the profession. This is related to issues of trust in the profession; whether teachers are considered responsible for what they do and how they can affect the extent to which they are trusted, and by consequence whether their profession as a whole is trusted.

The less decision-making power granted to teachers within this complex system, the less autonomous the profession. By consequence, the profession is perceived as less prestigious. Indeed, empirical data exist to support this relationship. The Teaching and Learning International Survey (TALIS), which collects teachers’ self-reported perceptions about the learning environment and working conditions in their schools, shows a strong positive association between the extent that teachers participate in decision-making and the likelihood that society values teaching as a profession (OECD, 2014a). In countries where teachers are not included as decision-makers, the teaching profession is less likely to be valued in society.

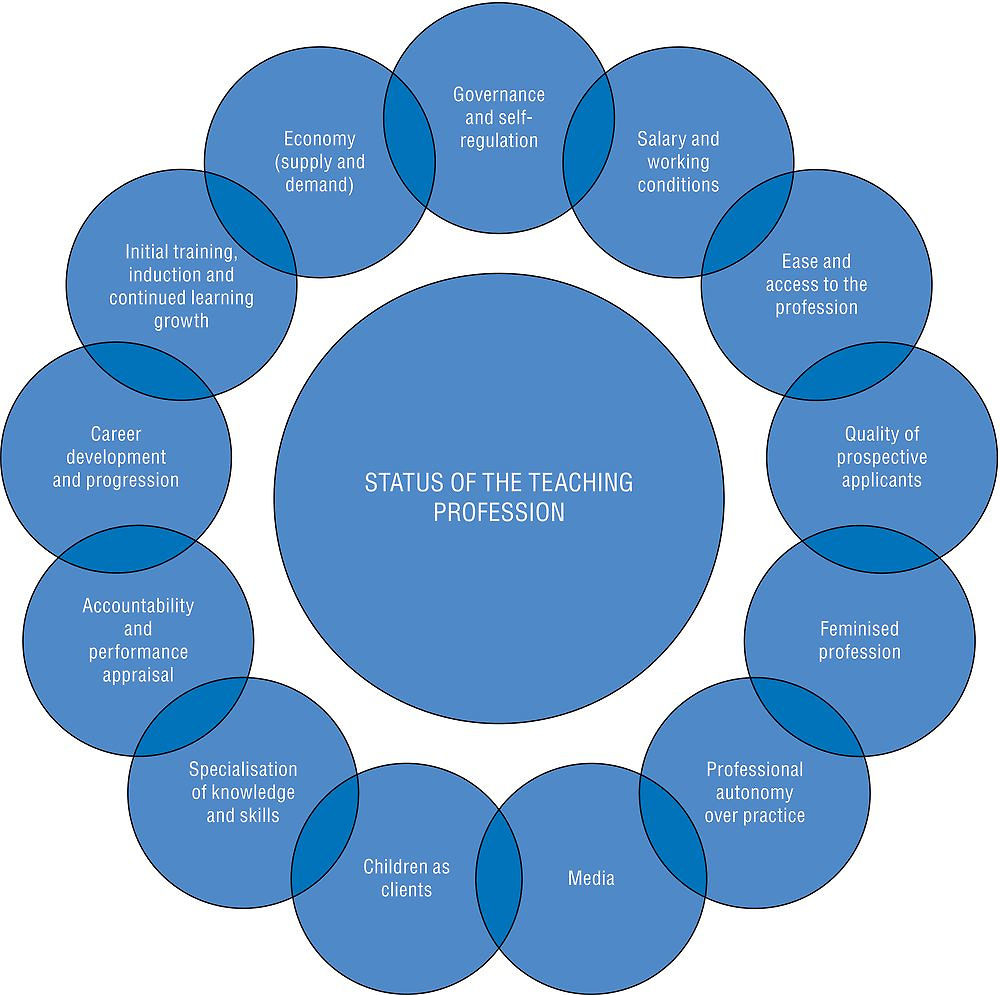

Governance and autonomy are just two of the factors that are frequently debated in the literature related to their influence over the status of the teaching profession. There are a range of other factors which in combination interact in complex ways to determine the resulting status, as illustrated in Figure 1.2 (in no particular order). Two that have been debated at length by policy makers and economists alike are salary and working conditions. In writings related to the sociology of professions, Hoyle (1995b) identified one noteworthy characteristic of full professions that does not appear in the list of Howsam et al. (1985). According to Hoyle (1995b: 13), “lengthy training, responsibility, and client-centeredness are necessarily rewarded by high prestige and a high level of remuneration”. Likewise, in the UNESCO/ILO (2008: 21) recommendation, the word “status” is used to refer to “the working conditions, remuneration, and other material benefits accorded them [teachers] relative to other professional groups”.

Indeed, salary and working conditions are often implemented as policy levers for improving the profession’s prestige. This is because in most OECD countries and partner economies teacher salaries are lower compared to occupations requiring equivalent levels of education, and the salary difference is often cited as one of the primary reasons for the perception of the profession’s lower status. For example, OECD data indicate that across OECD countries primary-school teachers earn on average 81% of the salary of a tertiary-educated 25-64 year-old full-time, full-year worker; lower-secondary teachers are paid 85% of that benchmark; and upper-secondary teachers are paid 89% of that benchmark salary (OECD, 2016b). In terms of working conditions, factors often cited as negatively impacting the profession’s status include large class sizes, long teaching hours, excessive workloads, poor job security, lack of instructional resources, poor school safety, little or no access to professional development opportunities and excessive administrative duties (Leitwood, 2006). Some policy initiatives have tried to improve one or more aspects of teachers’ working conditions for raising the status of the profession with varying degrees of success (Hargreaves et al., 2007).

Public perceptions of the teaching profession

One factor that might play a role in shaping the public’s perception of the teaching profession is the media (Cameron, 2003). Media sources can portray a negative image of teaching, usually through film, but often via news reports, for example, when there are contract disputes between the government and teacher unions (Hargreaves et al., 2007). Others have written about how the importance of the “clients” of a profession affect its prestige (Eraut, 1994). In the case of teaching, the clients are children, and because children have a lower social standing than adults, by consequence the profession is lower in social status. Also, patriarchal attitudes in societies may contribute to the devaluation of teaching due to the high proportion of women in the profession (Hoyle, 1995a).

Indeed, teaching is predominantly a women’s profession. According to recent OECD data (2016b), women make up 97% of teachers at the pre-primary level, 82% at the primary level, 68% at the lower secondary level, 58% at the upper secondary level, and only 43% at the tertiary level. Additionally, recent international reports indicate that the proportion of female teachers is increasing (Commonwealth Secretariat and UNESCO, 2011). Interestingly, “a preponderance of women” is argued to be a characteristic of semi-professions identified by Howsam et al. (1985: 18). Often referred to as the “feminisation” of the teaching profession, the overrepresentation of female teachers has been argued to have a detrimental effect on its occupational status (Hoyle, 1995a).

Some have argued that the overrepresentation of female teachers may partly be the result of the profession attracting individuals (irrespective of gender) who value predictable work hours and long summer vacations because this corresponds well to the schedules of families with children (Podgursky, 2003, 2011). Because of issues such as family responsibilities and structural barriers such as limited opportunities for promotion, teaching is often perceived to be “career-less” (Lortie, 2002). OECD data indicate that, in most countries, opportunities for promotion and new responsibilities are generally limited for teachers who want to stay in the classroom (Schleicher, 2011). Even when upward mobility is an option, salaries are still smaller in relation to other hierarchical organisations. Poor career prospects and limited opportunities for continued learning and professional growth contribute to lowering the profession’s prestige (Hargreaves, 2009).

Accessibility

The teaching profession is generally viewed as easily accessible. When compared to other professional occupations such as medicine or law, selection into initial teacher education is not competitive. Factors such as the quality of prospective applicants into initial teacher education programmes and minimum entry requirements are highly related to occupational prestige. For example, it has been argued that those who enter teaching are generally of lower academic achievement than those who enter other professional occupations such as medicine or law (Hoyle, 1995a, 2001), and many scholars and policy makers have advocated for raising entry standards (Darling-Hammond, 2005; Carlo et al., 2013; Eurydice, 2015). To add to this, the rise of alternative entry routes might affect the profession’s prestige (Hargreaves and Flutter, 2013). Alternative entry routes and the private tutoring industry are often accused by teachers and teacher unions of contributing to the continued de-professionalisation of teaching (Finn and Petrilli, 2007). In some contexts, the rise of alternative entry routes has necessitated reducing the duration or scope of initial teacher preparation thereby impacting the depth of knowledge and skills to be acquired by graduates, or by restricting teacher education to the learning of routine-like, prescriptive practices, leading to further claims of de-professionalisation. On the other hand, alternative routes can also be effective (Humphrey et al, 2008). For example an evaluation of teachers in the U.S. trained through different routes to certification revealed no statistical difference between traditional preparation and alternative routes in terms of their impact on student achievement (Constantine et al, 2009).

Often, however, ease of accessibility has to do with market drivers affecting supply and demand, which are often out of the control of the profession itself. For example, opening up the profession through alternative entry routes or the lowering of entry requirements are usually the result of policies aiming to fill teacher shortages, either due to changing demographics, challenges in recruiting new teacher candidates, or teacher attrition. It is often suggested that there is a high attrition rate for novice teachers leaving the profession. For example, in the USA it has been reported that almost 50 percent of those who enter teaching leave before their fifth year of practice (Ingersoll and Perda, 2012; Perda 2013 as cited in Ingersoll and Merill, 2013). However, there is some variation between countries. For example in Israel 32% of upper secondary teachers leave the profession within their first 5 years, in England 27% and in the Netherlands 22.5% (OECD, 2014b). Hence, Hargreaves and Flutter (2013) introduce elements such as recruitment and retention as factors influencing teaching’s status.

At the same time, challenges in teacher recruitment and retention have been argued to be the result (rather than determinant) of the poor status of teaching. For instance, despite high demand for teachers or ease of access into the profession, many OECD countries and partner economies face challenges in recruiting new, particularly high-ability candidates and retaining quality teachers in the workforce. This is related to another approach to exploring the status of the teaching profession having to do with whether teaching is an attractive career choice (Everton et al, 2007; Carlo et al., 2013; Eurydice, 2015). A recent study investigating the career expectations of secondary school students in countries participating in the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) in 2006, reported that, on average across countries, only 5% of students indicated that they planned to work in the teaching profession (OECD, 2015). Whether challenges in recruitment and retention or the quality of prospective applicants are the result or the cause of the profession’s poor status remains an open question.

Teachers’ pedagogical knowledge and the teaching profession

According to the consensus of scholars as reviewed above, the knowledge, skills and expertise required by practitioners of full professions are the result of a lengthy period of specialised training and continuous professional development. The more specialised the knowledge and skills, the lengthier and more challenging the training. In the case of teaching, as discussed previously, it has been argued that the knowledge and skills required by teachers are often considered to be less sophisticated than those required in other major professions (Hoyle, 1995b). Related to this is the notion that teaching can be learned simply through observation, and because most adults have experienced at least some type of formal schooling, teaching is therefore perceived as something that is easy to master and routine (Hoyle, 1995a, 2001). Indeed, for almost two hundred years those who were responsible for teaching in schools were not subject to any form of specific preparation or training (Lortie, 2002). Those who entered the teaching profession tended to have varied qualifications, and the occupation was unregulated (Lortie, 2002).

The lack of a profession-specific knowledge base and the absence of any specialised pedagogical training are important factors implicated in the lower prestige of the teaching profession, and likewise, in characterising teaching as a semi-profession. Others who argue that teaching is not a profession, or that it is rather a semi-profession, have similarly pointed to the absence of a profession-specific or specialised knowledge base derived from scientific processes (e.g. Ingersoll and Merrill, 2011; Thomas, 1998). For Hoyle (1995a), specialisation is linked to a higher professional status and this may help explain why secondary teachers, who are specialised in the content they teach, are considered to have a higher status than those in primary education, who are generalists. Hoyle (1995a) further argues that another reason the teaching profession has been unable to enhance its status is the uncertain relationship between educational and pedagogic theory, pedagogic practice and learning outcomes, and points to the frequency with which teachers themselves appear to criticise educational theory as irrelevant to their everyday practice (Hoyle, 1995b). In such a way, it is argued, teachers cast doubt on their own professional knowledge.

And this is the rationale for our book on teachers’ pedagogical knowledge and the teaching profession: What is the nature of teachers’ pedagogical knowledge? Is the current state of teachers’ pedagogical knowledge evidence-based and grounded in current scientific understanding about learning? Is teaching practice informed by research? To date, this is still not clear. Furthermore, there is more to competent teaching than a scientifically-informed knowledge base. How does teachers’ pedagogical knowledge relate to overall professional teaching competence? And how do these relate to the professionalisation of teaching? We argue that raising the status of the teaching profession can be achieved by making teaching and learning more scientific and evidence-based.

The empirical study of teaching and learning has been going on for centuries and, especially in recent decades, there is a growing body of scientific literature investigating teaching and the effects of various teaching practices on student learning. One prominent example is the work of Hattie (2009) who conducted a synthesis of educational research studies looking at which teaching practices had the most influence on student learning. Are teachers familiar with this and related research or do they continue to use practices that have been shown not to work? Another example comes from the interdisciplinary field of the “Science of Learning”, which includes the foundation fields of cognitive science, neuroscience and developmental psychology. This new field of research has made huge progress in understanding how the human brain processes, encodes and retrieves information, and how these biological processes interact with aspects of the social learning environment. Understanding how the brain works and how the brain is affected by social interactions with parents, peers and teachers, and how learning is hindered by environmental factors such as poverty or trauma, can inform teachers’ pedagogical practice. Such an understanding can help teachers adapt lessons to individual students’ prior knowledge, motivation and ability levels, for example, or help teachers to design and structure lessons to enable deep, rather than surface, learning.

Thus, teachers’ pedagogical knowledge base is not static. New knowledge emerges from research or is shared through professional communities, and this knowledge needs to be accessed, processed and evaluated, and transformed into knowledge for practice. As professionals, teachers are expected to process and evaluate new knowledge relevant for their core professional practice and to regularly update their profession’s knowledge base. Indeed, one of Hargreaves’s (2000) recommendations for re-professionalising teaching is for teachers to implement a rigorous knowledge base that supports their professionalism through a critical assessment of the scientific basis of effective teaching before applying it to practice. Similarly, Buchberger (2000) argues that professionalisation of teaching can be achieved by adopting scientifically-validated knowledge and practices. Importantly, as proposed by Helsby and McCulloh (1996 in Whitty, 2008), having control over how their knowledge is developed, negotiated and used in the classroom is a key factor underlying teachers’ autonomy. As we have argued in the previous section, professional autonomy is an important determinant of a profession’s prestige.

The nature of teachers’ pedagogical knowledge and how new knowledge is incorporated into the profession is an especially relevant issue for policy makers. The learning environments of today’s classrooms are becoming more diverse and teachers are expected to teach “21st century skills” that are the new priority among OECD countries and partner economies. In our increasingly complex, knowledge-based and interconnected digital societies, the labour market requires a new set of skills previously of little significance for seeking employment. Today, skills such as creativity, critical thinking, problem-solving, collaboration, communication, among others, are necessary to succeed in the labour market. These new demands require teachers to deviate from traditional teaching methods and to employ innovative, evidence-based teaching practices. For some countries, this might entail a re-skilling of the current teaching workforce and upgrading of the profession’s knowledge base within teacher education institutions and through professional communities. Therefore, understanding what the current knowledge base looks like will help determine whether and to what extent re-skilling is required.

Thus, there is a need to derive evidence-based suggestions for educational policy and future research by examining the current state of teachers’ pedagogical knowledge and implications for the instructional process. Although new research is suggesting that a high level of pedagogical knowledge is part of competent teaching, there is still the need to assess teacher knowledge as a learning outcome of teacher education systems and as a predictor of effective teaching and student achievement. These questions are important for making policy improvements across the spectrum of the teaching workforce, from policies directed to pre-service teachers and teacher educators in initial teacher education, through to novice teachers undergoing induction and mentoring, and to in-service teachers participating in professional development.

This volume

With the above considerations in mind, the OECD Centre for Educational Research and Innovation (CERI) Symposium on “Teachers as Learning Specialists – Implications for Teachers’ Pedagogical Knowledge and Professionalism” (Brussels, 18 June 2014) brought together leading experts in the field to begin explore two overarching questions: (1) What is the nature of the pedagogical knowledge base of the teaching profession, and (2) is the pedagogical knowledge of the teaching profession up-to-date?

Part I of this book provides a broad contextual overview of teacher’s knowledge and the teaching profession. We explore the dynamics of knowledge in the teaching profession from a structural, functional and social perspective and what complexity theory can offer to understanding the governance of teachers’ knowledge. Next we look at how teachers’ professionalism and pedagogical knowledge is manifested through instruments such as qualification frameworks and professional standards. Parts II and III bring together the set of papers contributed by experts at the symposium.

The purpose of Part II is to explore current conceptual and empirical work on teachers’ pedagogical knowledge, and how pedagogical knowledge can be measured as an indicator of teacher quality. It investigates the following:

-

How is teachers’ general pedagogical knowledge conceptualised? Is it multi-dimensional, and if so, what are the various cognitive dimensions and can these be measured?

-

How do teachers’ motivations and beliefs about teaching relate to their pedagogical knowledge and how can these relationships be measured?

-

How does teachers’ pedagogical knowledge impact student learning outcomes?

-

What is the relationship between pedagogical knowledge and teachers’ overall professional competence, and how can it be measured?

Chapters 4 to 8 synthesise literature on teachers’ pedagogical knowledge, propose various models and concepts to better understand the complex nature of teacher competence, including both cognitive and affective-motivational facets. They also underline how teachers draw on their pedagogical knowledge in the classroom and investigate the motivational factors that drive expert teaching.

Part III is designed to be forward-looking and explores the impact of 21st century demands on teachers’ knowledge and the teaching profession through the following questions:

-

Does the knowledge base of teachers sufficiently incorporate the latest scientific research on learning? Can scientific research inform teachers about how to create effective teaching-learning environments?

-

Does the current state of teachers’ pedagogical knowledge meet the expectations for teaching and learning “21st century skills”?

Chapter 9 investigates whether and how incorporating findings from the Science of Learning into teachers’ knowledge base could enhance teaching and learning. The authors argue that teachers who understand the mechanisms that underlie learning can enhance the cognitive engagement of their students and help to realise the potential for each and every student to learn. Chapter 10 reviews the definition of “21st century skills” and terms like “deep learning” and “transfer of knowledge”. It provides a state of the art of the empirical evidence on how these various competencies matter for success in education, work and other aspects of adult life, and underlines the challenges in assessment and in teaching for transfer.

We conclude with a summary of the work presented in this volume and discuss implications for the teaching profession. The argument that will emerge is that teaching should become a more evidence-based practice, and importantly, be informed by scientific research on teaching and learning. We argue that grounding the practice of teaching in a scientific knowledge base will address the challenges that are giving the profession a low status. Doing so would address the argument made previously that teachers do not generally use scientific knowledge in their practice, or that they do not contribute to building a pedagogical knowledge base founded on scientific principles.

Of course, this would require considerable reforms to how teachers are trained, the duration of training, and correspondingly, reforms to the roles and responsibilities of teacher educators. As a consequence of such reforms, we would expect corresponding changes to minimum standards for entry into teacher education programmes, and likewise, for certification and licensing. More stringent entry requirements, a lengthier training period, and practice grounded in a scientific knowledge base typically leads to the profession being granted autonomy and trust over daily practice and governance, and consequently, a higher prestige.

References

Biddle, B. J. (1995), “Teachers’ Roles”, in Lorin W. Anderson (Ed.), International Encyclopedia of Teaching and Teacher Education, pp. 61-67, Oxford: Pergamon Press (2nd ed).

Burns, T. and F. Köster (2016), Governing Education in a Complex World, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264255364-3-en.

Cameron, M. (2003), Teacher Status Project: Stage 1 Research: Identifying Teacher Status, its Impact and Recent Teacher Status Initiatives, Prepared for the New Zealand Teachers Council and the New Zealand Ministry of Education.

Carlo, A. et al. (2013), Study on Policy Measures to Improve the Attractiveness of the Teaching Profession in Europe, Research Report EAC-2010-1391, European Commission, Directorate General For Education and Training.

Commonwealth Secretariat and UNESCO (2011), Women and the Teaching Profession: Exploring the Feminization Debate, London and Paris.

Constantine, J. et al. (2009), An Evaluation of Teachers Trained through Different Routes to Certification (NCEE 20094043), Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Education, Institute of Education Sciences, National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance, http://ies.ed.gov/ncee/pubs/20094043/index.asp.

Darling-Hammond, L. et al. (2005), Does Teacher Preparation Matter? Evidence about Teacher Certification, Teach for America, and Teacher Effectiveness, CA: Stanford University, Stanford, www.srnleawds.org/data/pdfs/certification.pdf.

Darling-Hammond, L. (2000), “Teacher quality and student achievement: A review of state policy evidence”, Education Policy Analysis Archives, Vol. 8/1, pp. 1-44.

Eraut, M. (1994), Developing Professional Knowledge and Competence, Falmer Press, London.

Etzioni, A. (1969), The Semi-Professions and their Organization, The Free Press, New York.

Eurydice (2015), The Teaching Profession in Europe: Practices, Perceptions, and Policies, Eurydice Report, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg.

Everton, T. et al. (2007), “Public perceptions of the teaching profession”, Research Papers in Education, Vol. 22/3, pp. 247–265, https://doi.org/10.1080/02671520701497548.

Evetts J. (2012), “Professionalism in Turbulent Times: Changes, Challenges and Opportunities” delivered at Propel Inaugural Conference: Professions and Professional Learning in Turbulent Times: Emergent practices and Transgressive Knowledges, Stirling University, 11 May, www.propel.stir.ac.uk/downloads/JuliaEvetts-FullPaper.pdf.

Finn, C. E. and M. J. Petrilli (2007), “Forward”, in K. Walsh and S. Jacobs (Eds.), Alternative Certification isn’t Alternative, pp. 7-11, Thomas B. Fordham Institute, Washington, DC.

Freidson, E. (2001), Professionalism, the Third Logic, Polity, Cambridge.

Hanushek, E.A., J. F. Kain and S. G. Rivkin (1998), “Teachers, schools, and academic achievement”, NBER Working Paper Series, No. 6691, National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge, MA.

Hargreaves, L. (2009), “The status and prestige of teachers and teaching”, in Saha, L. and Dworkin, G. (Eds.), The Springer International Handbook of Research on Teachers and teaching, Vol. 21, Part 1, pp. 217-230., Springer, New York.

Hargreaves L. et al. (2007), The Status of Teachers and the Teaching Profession in England: Views from Inside and Outside the Profession, Final Report of the Teacher Status Project, Research Report No 831A, University of Cambridge, Faculty of Education/Department of Education and Skills.

Hargreaves L. and Flutter J. (2013), “The status of teachers and how might we measure it?”, presentation given on the 9th EI Annual Research Network (ResNet) meeting held in Brussels, Belgium, on 10-11 April, 2013.

Hargreaves, A. (2000), “Four Ages of Professionalism and Professional Learning”, Teachers and Teaching: History and Practice, Vol. 6/2, pp. 151-182.

Hattie, J. (2009), Visible Learning: A Synthesis of over 800 Meta-analyses relating to Achievement, Routledge, London.

Howsam, R.B. et al. (1985), “Educating a profession”, reprint with postscript 1985, Report of the Bicentennial Commission on Education for the profession of teaching of the America Association of colleges for teacher education, American Association of Colleges for Teacher Education, Washington, DC, http://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED270430.

Hoyle, E. (2001), “Teaching Prestige, Status and Esteem”, Educational Management Administration & Leadership, Vol. 29/2, pp. 139–152, https://doi.org/10.1177/0263211X010292001.

Hoyle, E. (1995a), “Social Status of Teaching”, in Lorin W Anderson (Ed) International Encyclopaedia of Teaching and Teacher Education, pp. 58-61, Pergamon Press, Oxford.

Hoyle E. (1995b), “Teachers as professionals”, in Lorin W Anderson (Ed) International Encyclopedia of Teaching and Teacher Education, pp 11-15, Pergamon Press, Oxford.

Humphrey, D. C., M. E. Wechsler, M. E. and H. J. Hough (2008), “Characteristics of Effective Alternative Teacher Certification Programs”, Teachers College Record, Vol. 110/1, pp. 1–63.

Ingersoll, R.M. and E. Merrill (2013), “Seven trends: the transformation of the teaching force”, updated October 2013. CPRE Report #RR-79, Consortium for Policy Research in Education, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

Ingersoll, R.M. and E. Merrill (2011), “The Status of Teaching as a Profession”, in J. Ballantine and J. Spade (Eds.), Schools and Society: A Sociological Approach to Education, 4th Ed. Press/Sage Publications, pp. 185-189, CA: Pine Forge.

Krejsler, J. (2005), “Professions and their identities: How to explore professional development among (semi-)professions”, Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, Vol. 49/4, pp. 335–357, https://doi.org/10.1080/00313830500202850.

Leithwood, K. (2006), Teacher Working Conditions that Matter: Evidence for change, Elementary Teachers’ Federation of Ontario, Toronto.

Lortie, D. C. (2002), Schoolteacher, 2nd ed., The University of Chicago Press, Chicago and London.

Muñoz, M.A., J. R. Prather, J.R. and J.H. Stronge (2011), “Exploring teacher effectiveness using hierarchical linear models: Student- and classroom-level predictors and cross-year stability in elementary school reading”, Planning and Changing, Vol. 42/3/4, pp. 241–273.

OECD (2016a), Supporting Teacher Professionalism: Insights from TALIS 2013, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264248601-en.

OECD (2016b), Education at a Glance 2016: OECD Indicators, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/eag-2016-en.

OECD (2015), “Who wants to become a teacher?”, PISA in Focus, No. 58, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/5jrp3qdk2fzp-en.

OECD (2014a), New Insights from TALIS 2013: Teaching and Learning in Primary and Upper Secondary Education, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264226319-en.

OECD (2014b), Table D6.5d. Entry into the teaching profession, upper secondary education (2013), in Education at a Glance 2014: OECD Indicators, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/888933120252.

Podgursky, M. (2011), “Teacher compensation and collective bargaining”, in E. A. Hanushek, S. Machin and L. Woessmann (Eds.), Handbook of the Economics of Education, Vol. 3, pp. 279–313, North Holland, Amsterdam.

Podgursky, M. (2003), “Fringe benefits: There is more to compensation than a teacher’s salary”, Education Next, Vol. 3/3 pp. 71-76.

Reagan, T. (2010), “The professional status of teaching”, in R. Bailey, et al. (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of philosophy of education, pp. 209-22, SAGE Publications Ltd, London.

Schleicher, A. (2011), Building a High-Quality Teaching Profession: Lessons from around the World, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264113046-en.

Shon, C.K. (2006), “Teacher Professionalism”, Faculty Publications and Presentations, Paper 46, http://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/educ_fac_pubs/46.

Thomas N. (1998), “Teaching as a profession”, Education 3-13: International Journal of Primary, Elementary and Early Years Education, Vol. 26/1, pp. 8-16.

UNESCO and ILO (2008), The ILO/UNESCO Recommendation concerning the Status of Teachers (1966) and The UNESCO Recommendation concerning the Status of Higher-Education Teaching Personnel (1997), http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0016/001604/160495e.pdf.

Whitty, G. (2008), “Changing modes of teacher professionalism: Traditional, managerial, collaborative and democratic”, in B. Cunningham (Ed.), Exploring Professionalism, pp. 28-49, Bedford Way Press, London.

Wright, S.P., S.P Horn and W.L. Sanders, (1997), “Teacher and classroom context effects on student achievement: Implications for teacher evaluation”, Journal of Personnel Evaluation in Education, Vol. 11, pp. 57-67.

Note

← 1. The statistical data for Israel are supplied by and under the responsibility of the relevant Israeli authorities. The use of such data by the OECD is without prejudice to the status of the Golan Heights, East Jerusalem and Israeli settlements in the West Bank under the terms of international law.