Chapter 6. The political economy of the ITQ system and resource rent tax in Icelandic fisheries

This case examines the political economy of the reform to establish an economically efficient and more environmentally-sustainable fisheries management system in Iceland based on individually transferable quotas. It also discusses the introduction of a resource rent tax to more broadly share the benefits from harvesting a common property resource with the general public. The case study draws lessons learned about the drivers of reform, how distributional issues were addressed, and how subsequent reforms were undertaken to respond to specific stakeholder demands.

Introduction

The introduction in the 1980s of the individually transferrable quota (ITQ) management system in the Icelandic fisheries was driven by a looming crisis. It became apparent that the status quo would most likely lead to fisheries collapse and major economic hardships for the country as a whole. With the Fisheries Act in 1990, the ITQ system became comprehensive and thus, the cornerstone of the fisheries management system. Evidence suggests that the Icelandic ITQ system has been very successful in increasing efficiency in the fisheries and created the correct incentives for fishers when it comes to safeguarding and rebuilding fish stocks. The case study shows how a crisis threatening an economically vital industry can provide the political drive for reform. It also illustrates that despite the overall economic gains of the reform, it still produced winners and losers, which spurred later reforms to the system.

6.1. An overview of marine biodiversity and the fisheries sector in Iceland

Marine biodiversity in Iceland

Around 270 fish species have been identified in Icelandic marine waters and at least 150 of these spawn within the exclusive economic zone (EEZ). Only around 20 of these are harvested to any considerable extent by the fishing fleet and just a handful of species (notably cod) predominate in catches (MENR, 2014). The warm and cold currents in Icelandic seas combined with nutrient-rich seawater provide an environment highly conducive to flourishing marine life and high-yield fishing grounds. Although measurable amounts of pollutants are found in marine catches, pollutant concentrations in fish are generally below maximum levels and declining, which is important for maintaining the market value of Icelandic marine produce (MENR, 2014). This productive marine ecosystem has supported a robust fishing industry, accounting for about 7% of GDP, with marine products representing more than 25% of total exports of goods and services in 2012 (measured in value); although the share has been in decline since 2000 (OECD, 2014).

Iceland’s first National Biodiversity Strategy (NBS) was prepared by the Ministry of Environment and Natural Resources (MENR) and adopted by the Government in 2008. An Action Plan for the implementation of the NBS was prepared by the Ministry for the Environment, in co-operation with other relevant ministries, and approved by the Government in 2010. The main focus is on increasing knowledge about the state and trend of biological diversity and securing protection of species in danger or threatened by extinction. Although fisheries do not figure prominently in the NBS, Iceland has designated five protected areas for the conservation of cold water corals as well as three marine areas protected for biological diversity, with a total of 455 000 hectares of marine protected areas (MENR, 2014).

Iceland’s National Strategy for Sustainable Development includes specific objectives related to the sustainable use of living marine resources (MENR, 2010). The objectives emphasise that the use of fish stocks should remain on a sustainable basis and based on the best available scientific findings. They also state that for those fishing stocks that require harvest limits, a cautionary approach to management should be taken, so as to achieve maximum yields over the long run. Finally, the objectives specify that the use of living marine resources should take into account the diverse interplay of the marine ecosystem and should aim to minimise negative effects of the use on other parts of the ecosystems. In the context of pollution prevention, the Strategy also includes an objective stating that the concentration of man-made pollutants in Icelandic marine products should always be less than the strictest standards of domestic and foreign health authorities (MENR, 2010).

Currently, none of the commercially harvested species in Iceland are considered to be threatened due to overfishing, although non-sustainable exploitation has been a problem in the past (MENR, 2014). For example, in the late 1960s, herring populations collapsed due to over-fishing and a drop in seawater temperatures, but have since recovered. For demersal fish,1 cod has experienced considerable declines, although haddock has increased. For many years, demersal fish catches exceeded levels recommended by scientists, but over the past decade, the limit of total allowable catches has been in line with the advice of the Marine Research Institute.2 The main purpose of most of the marine fisheries management areas has been to secure the sustainable use of the harvested resources, but not necessarily to conserve biological diversity per se (MENR, 2014).

Development of the fisheries sector in Iceland

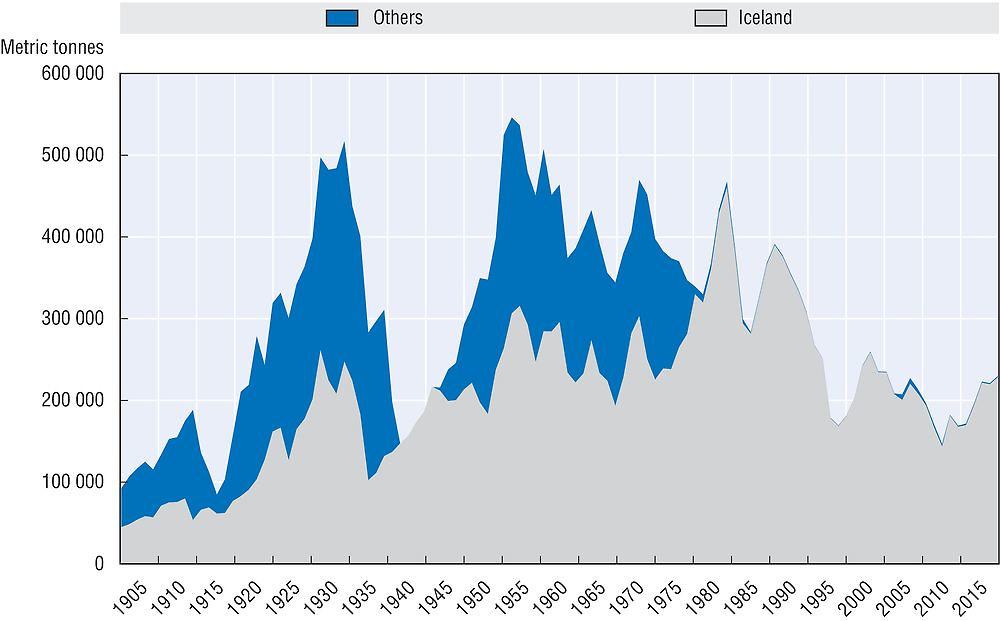

For many centuries, foreign fishing fleets were prevalent off the coast of Iceland. The first half of the twentieth century was marked by the struggle of Icelanders to control their waters and secure exclusive access to the resources. In 1901 Iceland declared a fishing limit of three nautical miles, which was extended to four miles in 1952. The fishing limits were gradually extended, to 12 miles, 50 miles and 200 miles in 1958, 1972 and 1976, respectively resulting in significant declines of foreign catches in Icelandic waters (Figure 6.1). These extensions were all opposed at the time by other fishing nations that used to fish in these waters, but these disputes have since been resolved by international agreements.3 The reasons behind the willingness of Icelanders to fend off foreigners were many, and included conservation issues such as the perceived danger of damaging coastal fishing grounds with the use of trawls and overfishing (Jóhannesson, 2004).

Source: Based on data from Marine Research Institute (2016), http://data.hafro.is/assmt/2016/cod/.

Year-round fishing villages did not appear around the Icelandic coast until the industrialisation of fisheries in the early twentieth-century4 when fisheries finally took off, quickly becoming the backbone of the economy.5 Although the share of the fishing industry in the economy, and notably as a percentage of the total labour force, has decreased over the years, it is still vital to Iceland’s prosperity and it is still the most important industry in many of the rural regions (Figure 6.2).

Source: Based on data from Statistic Iceland (2016), personal correspondence with G. Thordardottir.

The economic importance of fishing to the overall economy hinges upon many factors, both related to the industry itself, such as fishability and abundance of different species, but also the macroeconomic situation in general, not least the exchange rate of the local currency. Although the relative importance of the fishing industry in the Icelandic economy has declined (notably as a percentage of the total labour force), it still is one of the mainstays of the economy, accounting for 5% of GDP in 2015 (Figure 6.2). Around 56.7% of total merchandise export value came from seafood exports in 2015 (Statistics Iceland, author’s calculations).

In many rural regions, fishing is still the most important industry. It is notable that Iceland has a population of around 330 000 inhabitants of which around two-thirds live in the Southwest of the country, including the capital Reykjavik. The remaining population lives in scattered villages along the coast and on farms. In the fishing villages, there used to be very few opportunities outside of the fishing industry, until the beginning of the current boom in the tourism industry.

6.2. The introduction and evolution of the ITQ system

As is the case with many reforms, the introduction of the ITQ management system in the Icelandic fisheries was driven by a looming crisis. Fishing in Iceland expanded considerably in the post-war period,6 with foreign fishing fleets returning with an ever-increasing fishing effort due to technological advances and a considerable increase in the size of the Icelandic fleet. Catches of some valuable species such as haddock, decreased sharply between 1949 and 1953 and scientists became concerned about the state of some of the commercially important stocks. In 1975, the Marine Resource Institute published a report warning that if the cod fisheries were to be continued in a similar way, the catches were bound to fall drastically, mostly due to overfishing (Hafrannsóknastofnun, 1975). Due to its bleak message, the report was colloquially referred to as “The Black Report”. The main indications were poor recruitment and a diminishing size of fishable stock (Jakobsson, 1979). To manage the fishery, various effort restrictions were dominant (days-at-sea limitations and gear restrictions) and setting of total allowable catches (TACs) for different species.

Contrary to the prevailing belief at the time, good management was not secured by imposing gear and effort restrictions, setting TACs, providing subsidies to scrap fishing vessels or driving foreign fishing fleets from Icelandic waters.7 Since the common-property nature of the resource remained, the fishery consequently continued to suffer from overexploitation. It became apparent that Icelanders themselves had increased their fishing fleets and effort beyond what was biologically sustainable and that the economic performance of the fishing industry was poor as a result (Danielsson, 1997). Total productivity in the fishing industry (following the ITQ reforms) was 73% higher in 1995 than in 1973, compared to an increase in total productivity in other industries (excluding fish processing) of 21% over the same period (National Economic Institute, 1999). Emphasis had been on increasing investments in the fishing fleet to generate jobs and support rural regions depending on fisheries often with financial support through state-owned funds (Schrank, 2003; Matthiasson, 2008). Furthermore, although the Marine Resource Institute regularly published results regarding the recommended TAC for the main species, ministerial decisions by the Minister of Fisheries on the TAC most often exceeded the recommendations due to political and economic pressures from the electorate and the industry respectively, resulting in higher actual landings (Figure 6.3). Deviations from scientific recommendation was justified by referring to the uncertainty of scientific evidence and the economic and social necessity of not decreasing catches too dramatically in order to safeguard employment.

Source: Based on data from Marine Research Institute (2016), http://data.hafro.is/.

The Black Report underlined the need for reform and a new Black Report was released in 1983. It became apparent that the status quo would most likely lead to disaster and, given the importance of the fisheries for the national economy, that was not a gamble that many were willing to take, as a collapse of the fisheries would most certainly lead to major economic hardships for the country as a whole. A formal analysis of the mechanism leading up to the reforms is lacking but, generally speaking, the aforementioned poor economic performance of the fisheries coupled with scientific evidence on the poor state of commercially important stocks finally pushed the parliament to introduce new management measures.

Finally, in 1984 the ITQ system was introduced in the demersal fisheries with the allocation of the first quotas allotted to vessels. Individual quota systems (some transferable, others non-transferable) had already been used in some pelagic fisheries (herring and capelin) from the 1970s, and had proven to be very successful in reducing fleet sizes and fishing effort. With little doubt it can be said that this positive experience in Iceland helped in the introduction of a quota system in the more important demersal fisheries. Nevertheless, it was not self-evident that this positive experience from the pelagic fisheries could be applied to the more economically and socially important demersal fisheries.

This reform process was primarily driven by scientists, politicians and public servants. The involvement with other stakeholders, such as industry leaders and trade unions, was minimal. When the ITQ system was first introduced, it was not specified whether the new system was permanent or temporary. It was also clear that as with most reforms there would be winners and losers. As discussed later, not everyone participated in the ITQ system from the beginning and because the success of the system was not guaranteed, it would be an oversimplification to say that even all incumbents were supportive of the system in the beginning.8

The ITQ system was gradually introduced into Icelandic fisheries, incorporating more and more species and with more clear rules on transferability. It was nevertheless difficult to ensure that the TAC was not exceeded, partly because some boats could still opt for effort restrictions instead of quotas. Finally, with a new Fisheries Act in 1990, the ITQ system became comprehensive and thus, the cornerstone of the fisheries management system.

The essential feature of the ITQ system is that the quotas represent defined shares in the TAC of given stocks each fishing year. The quotas are permanent, perfectly divisible and fairly freely transferable. Discarding of fish is prohibited as well as high-grading. The TAC for each fishing season is formally decided upon by the Minister of Fisheries and is based on the scientific recommendation of the Marine Resource Institute. The allotted TAC for each species has followed quite closely the scientific recommendations in recent years. Since the fishing year 1994-95, specific catch rules have been used in determining the recommended TAC for cod. These catch rules, which basically set the allowable TAC for cod as a percentage of fishable stock size, were set to rebuild the spawning stock while at the same time providing clear guidance to industry on how that would be achieved.9

Has the ITQ system been a success?

From a pure economic theory point of view property rights-based systems in fisheries, if designed and implemented correctly, should yield numerous economic benefits, including;10

-

Reduced fishing effort due to the elimination of competition between vessels

-

Reduced cost of effort as firms can focus on catching their share with the lowest costs

-

Improved quality of catch as the firms are restricted by the quotas and can only increase revenue by improving the quality of catches

-

Reduction in fleet size due to rationalisation through buying and selling of quotas (less efficient vessels sell quotas and opt out of the fishery

-

Rent generation

There is ample evidence to support the view that the Icelandic ITQ system has been very successful in increasing efficiency in the fisheries. Overcapitalization, in the form of too large a fleet, unravelled quickly and profitability increased (Figure 6.4). The former situation of the fishing fleet being a recipient of state-aid quickly became history.11 Although direct subsidies in the Icelandic fisheries were generally lower than in many other countries, various programmes existed, e.g. public investments funds, funds granting fuel subsidies, vessel buyback programs and export grants. Also, before the ITQ system, the exchange rate of the national currency rate was regularly adjusted to improve the competitiveness of the fish exports compared to the main foreign competitors.12

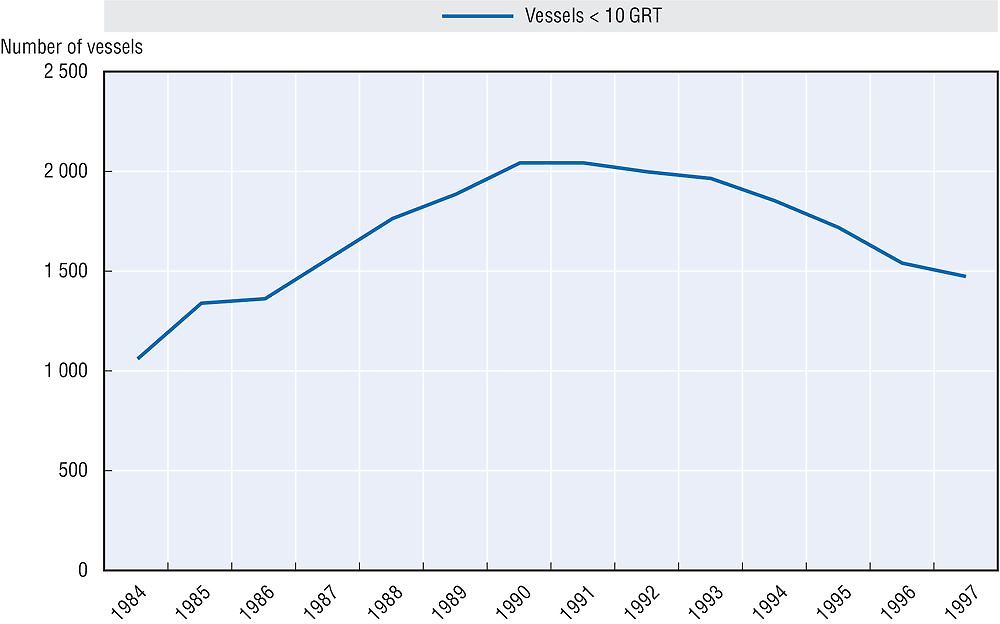

Note: GRT= “gross registered tonnes”.

Source: Based on data from Statistic Iceland (2016), personal correspondence with G. Thordardottir.

Given the option for smaller vessels to stay outside of the ITQ system, their numbers increased at the same time as larger boats exited the fishery (Figure 6.5).

Source: Based on data from Statistic Iceland (2016), personal correspondence with G. Thordardottir.

It is more difficult to evaluate the biological success of the system because of the inherent complexity and dynamics of the ecological system. However, it is clear that the reduction in fishing effort has secured the sustainability of most of the commercially exploited species (Figure 6.6).

Source: Based on data from Marine Resource Institute (2016), http://data.hafro.is/assmt/2016/cod/.

There are two important points to keep in mind when evaluating the biological and economic successes of the ITQ system in Iceland. First, the reduction in fishing effort was made possible due to the ITQ system. While it was necessary to reduce TACs for many species, notably cod, the fishers received quota shares in return, which helped them to survive the consequent economic hardships. The less efficient vessels could exit the fishery and were compensated through the sale of their quota shares.

Second, property rights systems such as ITQs can create the correct incentives for fishers when it comes to safeguarding and rebuilding fish stocks.13 Those that have permanent quota shares are able to take a long-term perspective as secure access rights mean that they can have confidence in being able to reap the benefits of fishing less today if restricting fishing now will increase their chances of fishing more later.14 This is of utmost importance as the appropriate incentive structure eliminates the wasteful race-to-fish and the so-called “Tragedy of the Commons”, which has often proven to be devastating for the biological sustainability of fish resources.15 The Fisheries Directorate keeps track of all exchanges between vessels by prices and quantities for each species. One measure of the economic efficiency of the ITQ system is to look at quota values over time. The annual quota rental values in the Icelandic fisheries increased dramatically (around 20-fold) between 1984 and 1999.16

The fisheries management system and biodiversity

The Icelandic ITQ system was a major reform driven mainly by economic considerations spurred by the threat of collapse of the most important fish stock. Given the economic importance of the fisheries, it was politically acceptable to adopt such drastic measures. When the system was introduced, the focus was mainly on avoiding collapse and improving overall economic performance in the sector, by dramatically decreasing fishing effort. Biodiversity as such, was not high on the agenda.

ITQ systems create incentives for fishers to operate in an economically efficient manner. Being assured a predefined share of the harvest provides surety and reduces the wasteful need to race, whilst transferability of quota brings market forces to bear on fishers by creating financial incentives to maximise the net return they generate on their quota. From a biodiversity perspective, an associated benefit of ITQs is that if the TAC is set at an appropriate level and there is effective monitoring and enforcement, they can also result in sustainable exploitation of the fish stocks they are used to manage. However, as the focus of ITQs is typically limited to a subset of commercially exploited species their ability to conserve biodiversity in the broader context is constrained by the scope of their application. When it comes to limiting the overall effects of fishing on biodiversity, other measures in addition to TACs for different species are needed.17

For these reasons, traditional management measures that protect habitat and reproduction capabilities in the ecosystem have always been applied along with the ITQ system in Iceland. These measures include temporal closures of spawning grounds, temporal spatial closures to protect juveniles, as well as restrictions on gear types for different time periods and fishing grounds. Such measures are based on scientific recommendations provided by the Marine Research Institute and are implemented frequently. Some zones have been closed from fishing for many years while others are closed for shorter time periods. The Coast Guard plays an active role in surveillance related to such management measures.

6.3. Political economy aspects of the ITQ system

The ITQ system has been considered a success from an economic efficiency perspective and has helped fish stocks to recover, putting fisheries on a more sustainable footing. However, political tensions and discontent have still emerged, spurring a number of exemptions and amendments to the system over the years. An account of some of the major issues is given below.

Distributional issues arose from the initial allocation of quotas

Much of the political discontent is due to the initial allocation of the quotas.18 When the system was first implemented for the demersal fisheries in 1984, the quotas were allocated to vessels based on each vessel’s average share in the total catch in the three years prior, i.e. 1981-83. There were certain exceptions to this rule, such as if the vessel in question had not been in full operation, e.g. because of major repairs or having entered the fishery later than 1981, the share was adjusted upwards. In the years 1985-87, there was a possibility to modify the TAC shares by temporarily opting for effort restrictions instead of quotas and thereby demonstrating higher catches during this period. When the allocations were made it was not stipulated whether they were permanent or not. From a legal standpoint, the quota shares represent user rights rather than property rights to the resource as such.

This approach, of initially grandfathering fishing rights is very common for property rights based systems because it is often the easiest approach from a political perspective and it can have positive efficiency advantages compared to some other means of distribution, e.g. by increasing rents by raising expected rates of return for investment and lowering the cost of capital.19 However, even more than thirty years later, this is considered by some people in and outside the industry to have been an unjust way of disbursing rights to harvest a commonly owned resource.20 According to the Fisheries Act, fish resources in Icelandic waters are common property of the nation, but the right to harvest has been transferred to the quota owners.

Whatever position one may have on the fairness of initially distributing fishing rights through a grandfathering system, it would be almost impossible to undo the distributional effects of the initial allocation now, as the quotas have been bought and sold many times over since the initial allocation and many of the vessel owners that received quotas originally have left the industry. The quota market is quite competitive and there is clear evidence of concentration of quotas with increasing transfers between different harbours (Agnarsson, et al., 2016). Through the Fisheries Act there is a limit to how much of the total quota for each species a company (or related businesses) can own.

A related issue to the initial allocation debate is how the general public in Iceland should receive benefits from the commonly owned fish resources. Although it is undeniable that the Icelandic economy has benefitted greatly from a more efficient fishing industry, claims have been made that the ITQ system generates resource rents to companies in the industry and that these resource rents should to a greater extent, accrue to the general public.21 Such claims have been voiced by different people and groups, including scholars and politicians. It is difficult to pinpoint such claims to specific political parties or views, or specific stakeholders. Regional differences exist when it comes to different views regarding critique of the system (Kokorsch et al., 2015). Since the introduction of the ITQ system most political parties in Iceland have taken part in various coalition governments, but all governments have kept the fundamentals of the system in place with only marginal changes made to the system. We give an overview of the most important ones below.22

A resource rent tax sought to remedy some of the distributional issues related to the initial free allocation of quotas

The Icelandic fishing firms have paid special fishing fees, mainly used to finance the running of the fisheries management system, since 2001. In 2012 a special resource rent tax was introduced. This resource tax is two-fold, i.e. it is composed of a general part, which replaced the older fishing fees and a specific part which is aimed at collecting a part of the resource rent. The resource rent tax system is quite complicated and has evolved over time but essentially it takes into consideration the profit margin in the harvesting of different species.23 Fundamentally, the system is designed in such a way that the different variable cost of fishing different species is reflected in the species specific tax rates.

The total tax receipts from this tax have changed somewhat over the years, due to changes in the profitability of the different fisheries over time. The tax levied on the industry amounted to ISK 12.8 billion for the fishing year 2012/13 and ISK 7.7 billion for the fishing year 2014/15.24 To put this into perspective, net profits of fishing firms (EBT) amounted to ISK 14.8 billion in 2014 and total tax receipts from Icelandic firms (tax on revenue and profits) amounted to roughly ISK 58.6 billion in 2015 (Statistics Iceland, 2014; Fjársýsla ríkisins, 2016). The revenues from the resource rent tax accrue to the general government budget.

Even though the resource rent tax has provided increased revenues to the state, there is still discussion on whether the tax rate is set too high or too low. Furthermore, in spite of the introduction of the resource rent tax, there are still claims for using other methods to collect the resource rent into the state coffers, such as through the auctioning of the fishing rights by the government. The main rationale being that an auctioning mechanism would reveal the true monetary value of the right in a better way than the current system. The fact that the Icelandic fishing industry can pay a special resource rent tax on top of other taxes and at the same time receives no subsidies, can be seen as a sign of its economic efficiency.

Exemptions for small vessels aimed to protect rural employment, but undermined the sustainability of the system

Although the Icelandic ITQ system was quite uniform from the start, the smallest boats in the fleet were exempt from the system in the beginning. The small vessel fleet is driven by professional motives rather than for subsistence or leisure, but is considered to create employment in many rural areas. Due to political desire to conserve employment in rural fishing villages there was a tendency to safeguard this fleet from consolidation through quota trades. In 1984, all boats measuring less than 10 gross registered tons were allotted 3.77% of the total cod catch of each year, but no restrictions were put on effort or catches for individual boats. The Ministry of Fisheries was supposed to stop the fishing activity of this fleet if the TAC was exceeded. This was not done despite exceedance of the TAC in both 1984 and 1985 due to political pressure from small scale fishers and rural communities, which were dependent on employment linked to small scale fishing.

In the years that followed, the authorities used various measures to try to get these small vessels to exit various effort-control regimes and enter the general ITQ system in spite of the aforementioned political resistance. The main driver behind this willingness to incorporate the small vessels in an ITQ system was to increase the overall efficiency of the industry, while political resistance came from those who stressed the importance of the small vessel fleet in maintaining rural employment. When various amendments were made to the Fishing Act in 1988-90 the legislative body tried to limit the increase in the number of small fishing vessels, which were entering the fishery. Nevertheless, new boats entered the fishery through various means often replacing those that exited.

The catches of this fleet were substantial. In the fishing year 1994/95, around 35% of the total cod catches in Iceland accrued to this fleet. In the fishing year 2001/02 the share of the small vessel fleet in the total catch of cod was around 8%, although the number of vessels had been reduced substantially. The number of small vessels outside the ITQ system was 1 022 in the fishing year 1993/94 but was down to 293 in the fishing year 2002/03.25

After various twists and turns aimed at reducing the fishing effort of the small vessel system which remained outside the ITQ system, the Minister of Fisheries finally decided in 2004 to abort the days-at-sea regime option for small boats and required them to enter an ITQ system. At that time, the number of small vessels outside of the system had decreased as previously discussed and the political resistance had diminished accordingly.

This development clearly shows the complicated political economy issues that can arise in fisheries reforms where different fleet segments are not treated in the same way. For example, it can be argued that in a situation where some fleet segments are exempt from being managed under an ITQ system they have an incentive to free-ride when it comes to rebuilding fish stocks.26 This hinges upon the assumption that such stakeholders have the political clout to do so.

Regional quotas were put in place to support communities where fishing is an economic mainstay

The transferability of quotas is an essential feature if a quota system is to increase the economic efficiency in the fishery. Quotas are sold or leased from less efficient vessels to more efficient ones. In the Icelandic system there is a limit to the consolidation of quotas in each species but nevertheless there have been concerns when quotas have been sold or leased from towns or regions where fishing is the mainstay of the economic activity. In order to address such concerns, special regional quotas were introduced in 2002. The authorities set aside a part of the TAC for specific species and distributed it to rural regions. As ITQs are determined as a percentage of TACs, this meant that the regional quotas were distributed at the cost of quota holders. Quota holders were not compensated for their loss. These quotas are a relatively small share of the total TAC and decisions regarding their distribution are taken by the Minister of Fisheries. These decisions are based on various factors, such as the employment status of the town or region concerned, whether quotas have been leased or sold from the area, how dependent the region is upon fisheries, etc. The idea behind the regional quotas is to help the communities rather than the fishing firms directly.

A recent study indicates that the effects of the regional quotas differ widely from one region to another (Karlsson and Johannesson, 2016). Interestingly, the regional quota allocation has also benefitted the greater capital region, due to its geographical proximity to some of the regions that received regional quotas. This is probably due to the importance of the greater capital region in processing and handling of fish (Karlsson and Johannesson, 2016).

Whether and how the ITQ system has affected the regional development in Iceland is a complicated issue as factors other than fisheries have an effect on whether people and businesses leave or enter various regions.27

The coastal fisheries system aimed to accommodate new entrants with small vessels, but the efficiency of this system is questionable

Although the small vessel fishery was finally incorporated into the quota system in 2004, demands were still made for specific measures for smaller vessels, mostly on the ground that entry into the fishing industry was difficult for newcomers. Also, small-scale hand-line fishing was considered by some to be ecologically superior to other fishing methods and that encouraging such activities would create employment and revitalize fishing communities.

To meet such demands, the authorities allowed for a specific coastal fishery system, which opened up in 2009. This is mainly a cod-fishery where small vessel owners can apply for a specific license. The only gear allowed is hand-line and the fishing season is limited to the summer months. In very broad terms, the coastal waters are divided into 4 parts (roughly, north-south-east-west). Only fishing vessels with appropriate licenses can fish in the designated area. A share of the total TAC for cod is allotted to the coastal fishery every year and is distributed between the different fishing areas. There are limits to how much each vessel can land in a day and when the total allowable catch for each area is reached, the fishing in that area stops. This fishery is well monitored and, as in all other fisheries, the catches are all weighted at official weights which exist in all ports.

This coastal fishery system rapidly turned into a derby-style fishery, where fishers compete to fish as much as quickly as possible, and the economic efficiency and results on the ease of entry of newcomers is questionable. This fishery is mostly carried out by seasoned fishers that had already left the industry or are still quota holders.28

6.4. Lessons learned

Averting a potential crisis threatening an economically vital industry provided the political drive to establish a sustainable resource management system

The introduction of the Icelandic ITQ system for managing its fisheries was a major reform spurred by an imminent collapse of the most important fish stock, which would have put the fishing industry in peril. Given the importance of the fishing activity to the Icelandic economy, people were willing to undertake strong measures. Having positive experience from similar measures on a smaller scale helped. Such a collapse would have meant economic hardship for the country as a whole. The ITQ system provided the correct incentives for the sustainable harvesting of fish and made it possible for fishers to safeguard stocks through decreasing effort and catches, while at the same time securing their long-term economic future. Such fundamental reforms were only possible to implement in such a short time period because of the perceived imminent threat.

Regarding other policy measures available at the time, it had become apparent that traditional measures, such as input controls (e.g. days-at-sea restrictions, gear restrictions) and output controls (TACs) had not been successful in bringing about sustainable extraction levels from the resources while at the same time the economic efficiency was poor. In that sense, the authorities had run out of policy options.

Although some of the design features of the Icelandic ITQ system have been criticised and various changes have been made over time to meet certain economic and political demands, it is still a success measured in economic efficiency and as a way of drastically reducing fishing effort to safeguard the sustainability of the fish stocks. Biodiversity was not one of the main issues when the system was introduced and other direct measures have been used to secure biodiversity in the marine ecosystem. Safeguarding biodiversity can nevertheless be seen as a positive by-product of the fisheries rebuilding process through the use of the ITQ system.

Overall economic gains of the ITQ reform were positive, but it still generated winners and losers, which consequently led to further reforms

Interestingly, the main stakeholders engaged in the reform design and implementation were government authorities, including scientists, rather than fishers or their associations. Introducing a property rights based system, such as ITQs, leads to changes that benefit some more than others, especially when fishing rights are freely transferable. People who live in fishing regions from which quotas are sold or leased are often left with few other employment opportunities and experience economic and social hardships. Although the quota owners receive payment for their quotas, others that depended on the fishing activity for their livelihood, directly or indirectly, do not receive such payments. Therefore, although the general economic outcome of such reforms is positive, there are clearly those that gain and those that lose from such reforms.

Some industry stakeholders, such as fishers and people whose livelihood depended to a great extent on the fishing (such as people in the processing industry and people living in rural areas dependent on fishing) were not explicitly engaged in the reforms and the implementation of the ITQ system. The subsequent amendments of the system to meet demands from different stakeholders such as small-vessel owners, as well as the regional municipalities, raises the question whether their inclusion into the design and implementation phases of the reforms would have led to the introduction of a different system than the one that was eventually adopted. The answer to that question is not simple, and it may be argued that such sweeping reforms would have been difficult to implement as quickly as was the case, if the process had included the participation of all the different stakeholders. Including every possible stakeholder group would have taken time and resulted in a political debate at every step of the process. On the other hand, limited initial stakeholder engagement may have led to piecemeal amendments to the system over time to respond to specific stakeholder demands, which in some instances may have undermined the sustainability and efficiency of the system.

References

Agnarsson, S. et al. (2016), “Consolidation and distribution of quota holdings in the Icelandic fisheries”, Marine Policy, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2016.04.037.

Anderson, T. et al. (2010), “Efficiency Advantages of Grandfathering in Rights-Based Fisheries Management”, NBER Working Paper No. 16519 (November).

Arnason, R. (2005), “Property rights in fisheries: Iceland’s experience with ITQs”, Reviews in Fish Biology and Fisheries, Vol. 15, No. 3, pp. 243-264.

Arnason, R. (1995), The Icelandic Fisheries The Evolution of a Fishing Industry, Fishing News Books. Oxford.

Arnason, R. (1993), “The Icelandic individual transferable quota system: a descriptive account”, Marine Resource Economics, Vol. 8, pp. 201-218.

Arnason, R. (1991), “Efficient management of ocean fisheries”, European Economic Review, Vol. 35, pp. 408-417.

Arnason, R. and S. Agnarsson (2003), “The role of the fishing industry in the Icelandic economy: A historical examination”, Institute of Economic Studies Working Papers, W03:08. University of Iceland.

Asche, F. et al. (2014), “Development in fleet fishing capacity in rights based fisheries”, Marine Policy, Vol. 44 (February), pp. 166-171.

Ásgeirsson, G. (2012), Kvótakerfið í fiskveiðum. Tilurð þess og áhrif á byggð og samfélag [The quota system in fisheries: The emergence and influence of communities and community], unpublished BA‐thesis, University of Iceland.

Chambers, C. and C. Carothers (2016), “Thirty years after privatization: A survey of Icelandic small-boat fishermen”, Marine Policy (in press).

Clark, C.W. and G.R. Munro (1982), “The economics of fishing and modern capital theory: A simplified approach”, In Mirman, L.J. and D.J. Spulber (eds.), Essays in the Economics of Renewable Resources, North-Holland.

Danielsson, A. (1997), “Fisheries management in Iceland”, Ocean and Coastal Management, Vol. 35, Issues 2-3.

Fjársýsla ríkisins [State Accounts] (2016), Ríkisreikningur 2015. [Treasury accounts 2015].

Grafton, R.Q. (1996), “Individual transferable quotas: theory and practice”, Reviews in Fish Biology and Fisheries, Vol. 6, Issue 1, pp. 5-20.

Hafrannsóknastofnun [MRI] (1975), Ástand fiskistofna og annarra dýrategunda á Íslandsmiðum og nauðsynlegar friðunaraðgerðir innan íslenskrar fiskveiðilandhelgi, [State of fish stocks and other species in Icelandic waters and the necessary conservation measures in Icelandic waters], Sérrit Hafrannsóknastofnunar [MRI Special publication], Hafrannsóknastofnun [MRI], Reykjavik.

Hagfræðistofnun [Institute of Economic Studies] (2007), Þjóðhagsleg áhrif aflareglu [Macroeconomic effects of HCR], Report No. C07:09, Hagfræðistofnun [Institute of Economic Studies] Háskóla Íslands. Reykjavik.

Hannesson, R. (2000), “A note on ITQs and optimal investment”, Journal of Environmental Economics and Management, Vol 40, pp. 181-188.

Hardin, G. (1968), “The Tragedy of the Commons”, Science, 162, pp. 1243-1248.

Haraldsson, G. (2008), “Impact of the Icelandic ITQ system on outsiders”, Aquatic Living Resources, Vol. 21, pp. 239-245.

Haraldsson, G. and D. Carey (2011), “Ensuring a Sustainable and Efficient Fishery in Iceland”, OECD Economics Department Working Papers, No. 891. OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/5kg566jfrpzr-en.

Innes, J. et al. (2015), “Mitigating undesirable impacts in the marine environment: A review of market-based management measures”, Frontiers in Marine Science, Vol. 2. Article 76.

Jakobsson, J. (1979), “Um forsendur „Svörtu skýrslunnar“ [The criteria “Black Report”] Ægir.

Jóhannesson, G.T. (2004), “How ‘cod war’ came: The origins of the Anglo-Icelandic fisheries dispute”, 1951-61. Historical Research, Vol. 77, Issue 198, pp. 543-574.

Karlsson, V. and H. Johannesson (2016), Skýrsla um ráðstöfun aflamangs sem dregið er frá heildarafla og áhrif þess á byggðafestu [Report on the TAC and its effects on sustainability], Rannsóknarmiðstöð Háskólans á Akureyri [Research at the University of Akureyri].

Kokorsch, M. et al. (2015), “Improving or overturning the ITQ system? Views of stakeholders in Icelandic Fisheries”, Maritime Studies, pp. 14-15.

Mace, P.M. et al. (2014), “The evolution of New Zealand’s fisheries science and management systems under ITQs”, ICES Journal of Marine Science, 71(2), pp. 204-215.

Matthiasson, T. (2013), “Closing the open-sea: Development of fishery management in four Icelandic fisheries”, Natural Resources Forum, Vol. 27, No. 1.

Matthiasson, T. (2008), “Rent Collection, Rent Distribution, and Cost Recovery: An Analysis of Iceland’s ITQ Catch Fee Experiment”, Marine Resource Economics, 23, No. 1 (2008): 105-117.

McWhinnie, S. (2007), “The Tragedy of the Commons in International Fisheries: An Empirical Examination”, The University of Adelaide School of Economics Research Paper, No. 2007-05.

Ministry for the Environment and Natural Resources (MENR) (2014), The Fourth National Report to the Convention on Biological Diversity, Reykjavík, www.cbd.int/doc/world/is/is-nr-04-en.pdf (accessed 24 August 2016).

Ministry for the Environment and Natural Resources (MENR) (2010), “Welfare for the Future: Iceland’s National Strategy for Sustainable Development – Priorities 2010-13”, Ministry for the Environment, Reykjavík.

National Economic Institute [Þjóðhagsstofnu] (1999), Þróun sjávarútvegs, kvótakerfið, auðlindagjald og almenn hagstjórn [Development of the fisheries quota system, resource tax and economic management]. Þjóðhagstofnun [National Economic Institute], Reykjavík, www.atvinnuvegaraduneyti.is/media/2011/Thjodhagstofnunarskyrsla1999.pdf.

OECD (2014), OECD Environmental Performance Reviews: Iceland 2014, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264214200-en.

OECD (n.d.), “Country note on national fisheries management systems – Iceland”, www.oecd.org/iceland/34429527.pdf (accessed 30 August 2016), p. 21.

Pascoe, S. et al. (2010), “Use of incentive-based management systems to limit bycatch and discarding”, International Review of Environmental and Resource Economics, Vol. 4(2), pp. 123-161.

Runolfsson, B. Th. (1997), “Regional impact of the individual transferable quotas in Iceland”, In Jones, L. and M. Walker (eds.), Fish or Cut Bait! The Case for Individual Transferable Quotas in the Salmon Fishery of British Columbia, Fraser Institute, Vancouver, BC.

Schrank, W.E. (2003), Introducing Fisheries Subsidies, FAO, Rome.

Statistic Iceland (2016), www.statice.is/ (accessed 16 August 2016).

Statistics Iceland (2014), “Rekstraryfirlit sjávarútvegs 2008-14” [Operating Fisheries: 2008-14, http://px.hagstofa.is/pxis/pxweb/is/Atvinnuvegir/Atvinnuvegir__sjavarutvegur__afkomasja/SJA08109.px/table/tableViewLayout1/?rxid=38f8b711-203c-4c5a-85e9-4d08032dc1ce (accessed 30 August 2016).

Thordardottir, G. (2016), personal correspondence.

University Centre of the Westfjords (2010), Úttekt á framgangi og áhrifum strandveiðanna sumarið 2009 [Stock of the progress and effects of coastal fishing in summer 2009], University Centre of the Westfjords, Ísafjörður.

Notes

← 1. Demersal fish live and feed on or near the bottom of seas or lakes.

← 2. The Marine Research Institute is a government agency under the auspices of the Ministry of Fisheries that provides the Ministry with scientific advice based on its research on marine resources and the environment.

← 3. Primarily the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS).

← 4. Prior to this, fishing in Iceland was in many ways very primitive through the ages and to a large extent seen and organised as a side-activity to farming, which was the mainstay of the economy.

← 5. This is a very general and simplified overview of the history of fishing and fisheries in Iceland. A more detailed discussion can be found in Arnason (1995) and Arnason and Agnarsson (2003).

← 6. During the Great War (1914-18) and World War II (1939-45) foreign fleets were almost non-existant on fishing grounds off Iceland.

← 7. These measures proved to be ineffective in lowering the fishing effort for many reasons. Most importantly, technical advances, such as more powerful engines and more efficient gear, resulted in effort creep which outpaced all the stringencies put in place through regulation. Above all, there was no or little incentive for each fishing firm to reduce its own individual level of effort, representing the well-known problem of free riding and the commons.

← 8. For a recent survey on attitutes towards the ITQ system by small-boat fishermen, see Chambers and Carothers (2016).

← 9. These catch rules have been changed slightly over time. For a discussion of catch rules in Iceland, their history and rationale, see Hagfræðistofnun (2007).

← 10. See e.g. Clark and Munro (1982), Arnason (1991), R.Q. Grafton (1996) and Hannesson (2000).

← 11. For a discussion see e.g. Danielsson (1994), Arnason (2005), Matthiasson (2008) Asche, Bjorndal and Bjorndal (2014).

← 12. For a discussion see Schrank (2003).

← 13. See OECD (2012).

← 14. If the growth rate of the fish stock in question is higher than the discount rate of fishers, ceteris paribus.

← 15. The notion of the “Tragedy of the Commons“ is attributed to Hardin (1968). For empirical studies, see e.g. McWhinnie (2007).

← 16. OECD (n.d.), “Country Note on National Fisheries Management Systems – Iceland“, pp. 21.

← 17. For a discussion on similar issues in New Zealand, see Mace, Sullivan and Cryer (2014) and for a general discussion of how incentive based measures may be applied to help conserve biodiversity see Pasecoe et al. (2010) and Innes et al. (2015).

← 18. See Kokorsch (2015) and Chambers and Carothers (2016).

← 19. See Anderson, Arnason and Libecap (2010).

← 20. For a survey of different perceptions regarding the fairness and efficiency of the system see Chambers and Carothers(2016).

← 21. See Haraldsson and Carey (2011) and Matthiasson (2008).

← 22. This overview is very general. For a more detailed discussion see Matthiasson (2008).

← 23. See Matthiasson (2008) for more detail on how the tax system operates and background information on the legislative activity that lead up to the its introduction.

← 24. The fishing year begins 1 September and ends 31 August.

← 25. Fisheries Directorate.

← 26. Haraldsson (2008).

← 27. See Runolfsson (1997) and Ásgeirsson (2012).

← 28. University Centre of the Westfjords (2010).