Chapter 3. Access and equity in higher education in Kazakhstan

This chapter looks at access, student preparation and admissions requirements for higher education. It also discusses the financial aid system and its effects on equity of access, as well as the barriers to equal academic achievement. The system in Kazakhstan places particular focus on high-performing students and there is a lack of data and monitoring processes to support disadvantaged students. Poor and uneven student preparation as well as current admissions requirements tends to favour students from better-resourced schools and those whose parents can afford tutoring. The systemic challenge of lower-quality, less well-resourced schooling for rural students and students from low socioeconomic groups acts as a significant barrier to equal academic achievement. Measures to address this issue remain limited, and the current financial aid system negatively affects equity of access.

Access and equity in higher education from an international perspective

Good access to higher education is generally taken to mean that all people with the desire and capability to attend university have the opportunity to do so, and to succeed in their studies, regardless of their background. It is linked to equity which requires that opportunities be “equally available to all citizens.” (Reisberg and Watson, 2011). Greater access does not necessarily lead to enhanced equity: to ensure equity, it is necessary to “address the underlying factors that determine who enrols and who persists to graduation.” (Reisberg and Watson, 2011).

The OECD identifies two key dimensions of equity: fairness and inclusion. Personal or social circumstances (such as gender, ethnic origin or family background) should not be obstacles to achieving educational potential, and all individuals should reach at least a basic minimum level of skills. In education systems that achieve fairness and inclusion, the majority of students will have the opportunity to attain high-level skills, regardless of their personal and socio-economic circumstances (OECD, 2012a).

Approaches to ensuring equity in higher education are thus informed by principles such as the following:

-

Everyone who has the ability to study at a higher education institution should be able to do so.

-

Selection for higher education places should occur without discrimination on the basis of social class, gender, religion or ethnicity.

-

All individuals should be afforded the same opportunity to develop their talents (James, 2007).

Different interpretations of these principles influence national policies and strategies, and determine how effectiveness in achieving objectives is measured. Notably, different countries have adopted different strategies for expanding higher education access. These variations shape both how higher education is financed overall and how much financial support is provided to individuals seeking an education. The highest-performing education systems are those that combine fair access with high-quality student outcomes.

The skills and knowledge that higher education develops have positive effects on economic growth and regional competitiveness and, just as importantly, on individual employment and career prospects.

Higher education is also associated with wider benefits for individuals and society, from better health and life satisfaction to social cohesion and public safety (Department for Business Innovation and Skills, 2015) (see Figure 3.1).

Sources: Department for Business Innovation and Skills, UK, (2013), www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/254101/bis-13-1268-benefits-of-higher-education-participation-the-quadrants.pdf.

Importantly, higher education has the potential to reduce social inequalities, and thus lessen the social and economic costs (lower growth, lower investment) that come with inequality (OECD, 2015). Nonetheless, increasing overall levels of education does not necessarily lead to increases in social mobility and more equitable outcomes.

Sometimes, if opportunities are not equitably distributed, higher education simply reproduces social stratification. This occurs for instance when “merit” criteria for access to higher education heavily reflect the advantages that young people derive from their family’s socio-economic status (e.g. access to better schools and to tutoring, access to more powerful social networks). Across the world, the expansion of higher education has often failed to narrow wide disparities in the rates at which students from higher and lower income families enter and complete their studies. Indeed, there is growing evidence that higher education has, in some instances, widened rather than narrowed social disparity – and that imbalances in access to higher education have had a negative effect on intergenerational mobility (Department for Business Innovation and Skills, 2015; Redmond et al., 2014).

Low socio-economic status (SES) involves more than narrow economic disadvantage: it is characterised by gaps in social capital (i.e. the links, shared values and understandings in society that enable individuals and groups to trust each other and work together) and cultural capital (i.e. the ideas and knowledge that people draw upon as they participate in social life, including understanding of socially appropriate behaviour and the capacity to communicate effectively). In most countries, social class is the single most reliable predictor of the likelihood that individuals will participate in higher education at some stage in their lives and that, if they participate, they will have access to more prestigious institutions and fields of study. This is particularly true in developing countries, where lower SES students often have little chance of gaining entry to higher education.

Delivering equity in (higher) education is one of the most challenging problems facing policy makers (see Box 3.1). Despite widespread acknowledgement of the positive role and contributions of higher education to a broad range of social and economic goals, there is great variation in the extent to which countries invest in this area and in the way these investments support individual opportunities.

OECD research finds that:

-

Only one in five students from families with low levels of education attains a tertiary degree. By way of comparison, on average across OECD countries, two-thirds of students who have at least one parent with tertiary education graduate from tertiary education.

-

Young women are more successful than young men in attaining levels of education that are higher than their parents.

-

On average across OECD countries, approximately half of 25-34 year-old non-students have achieved the same level of education as their parents, while more than one-third have surpassed their parents’ educational level.

Sources: OECD (2012b), Education at a Glance 2012: Highlights, OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/eag_highlights-2012-en.

Policies to address barriers to access and equity

At a time when many OECD countries are experiencing increased higher education enrolments that are accompanied by significant budget constraints, there is a real challenge of identifying the most effective and equitable approach to promote higher education access and good student outcomes. The challenge for all systems in pursuing equity is twofold:

-

Provide the best opportunities for all students to achieve their full potential.

-

Address instances of disadvantage which limit educational achievement.

Raising aspirations and providing active support

There is overwhelming evidence that the condition of primary and secondary schooling is the main impediment to achieving equitable outcomes in higher education (OECD, 2012a, 2014a and b). Practices in pre-tertiary education, and in particular during the early years of schooling, affect students in ways that have profound consequences for their later years (Ferguson et al., 2007). The under-representation of people from low SES backgrounds in higher education is typically a consequence of the effects of lower school completion rates and lower levels of skills attainment in basic education (limiting opportunities when competitive entry is based on academic achievement). It is also a consequence of lower levels of educational aspiration, lower perceptions of the relevance of higher education and a lack of affiliation with the culture of universities (Bowes et al., 2013).

In many countries the idea of “first in family” or “first generation” students has been a useful device for identifying and addressing the particular needs of these students. Programmes that tackle social disadvantages, raise aspirations and change expectations about education have been shown to make a measurable difference in access to and success in higher education. Such initiatives are most effective when centrally co-ordinated and supported (Bowes et al., 2013).

In many education sectors there are strong, centrally financed schemes that work with schools in disadvantaged and low SES areas to raise aspirations, and familiarise students with the idea of higher education. These schemes may involve visits from faculty who will talk about higher education and teach school students. Summer or vacation schools on campus for rural and disadvantaged school students expose them to higher education and give them additional instruction. Peer mentoring schemes, where higher education students work with school students, have been very effective at raising aspirations (Garranger and MacRae, 2008). For instance, the Australian Indigenous Mentoring Experience (AIME) programme has successfully utilised peer mentoring strategies with indigenous secondary school students to raise aspirations, improve school completion and attainment rates and enhance employment outcomes (KPMG, 2013). In Canada, joint university/school programmes that focus on the aspirations of disadvantaged youth, such as the University of Winnipeg’s Wii Chiiwaakanak Learning Centre, have also been shown to be effective in exposing students to higher education and in encouraging them to think of higher education as a real future for them.

In 2009, the Australian government introduced the Higher Education Participation and Partnerships Programme (HEPPP) aimed at improving access and retention among students from lower socio-economic backgrounds. The “participation” component offers universities a financial incentive to enrol and retain low SES students. The funds can be used by institutions to finance outreach activities.

Partnership projects funded by the HEPPP have led to collaboration among universities. For instance, Bridges to Higher Education is a collaborative project among five universities in the state of New South Wales. It is aimed at dramatically improving the participation rate of students from communities that are under-represented in higher education in the state. The programme has delivered positive results as measured by external evaluations. Projects have been focused on:

-

students’ academic preparedness and outcomes (e.g. academic skills sessions, and mentoring and tutoring by current university students)

-

access to higher education (e.g. student visits to university campuses, community events, and focus groups for parents)

-

school community and capacity – projects creating partnerships with schools, communities and universities (e.g. via teachers’ professional development workshops and community events)

-

awareness, confidence and motivation – projects improving students’ awareness of higher education possibilities

-

engaging Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples – projects centred on aspiration-building, addressed to students’ unique and cultural needs.

Sources: Bridges to Higher Education (2016), www.bridges.nsw.edu.au/home; Gale, T. and S. Parker (2013), Widening Participation in Australian Higher Education, Report submitted to HEFCE and OFFA, www.ncsehe.edu.au/publications/widening-participation-australian-higher-education/.

Government policies in countries such as the United Kingdom and Australia (see Box 3.2) that have been aimed at widening access or participation have been particularly effective in increasing participation rates of students from low SES backgrounds (Higher Education Funding Council for England, 2015). For instance, “positive discrimination” measures, such as allocating places in higher education specifically for students from disadvantaged backgrounds, has played a major role in widening participation in Australia.

In Spain, the state is responsible for guaranteeing the uniformity and unity of the tertiary education system, including equality of opportunities and treatment within and across autonomous communities. It achieves this through the provision of financial assistance for low-income students through a national scholarship system and complementary schemes at regional level. Public universities have low tuition fees and higher vocational education institutions charge no fees. The creation of tertiary education institutions in each autonomous community provides increased access by expanding the supply of education. Active policies of positive discrimination target mature and disabled students. Complementary policies generate awareness of equity issues, particularly in the area of gender equality.

Addressing financial barriers

Sometimes, barriers to higher education stem from students’ limited financial resources. Growing up in a disadvantaged family where parents have low levels of education often means having less financial support available for studies. Furthermore, some young adults may have to enter the labour market early in order to support themselves and their families. Challenges are heightened if the education system does not provide support for students from disadvantaged backgrounds.

The answer to this problem is not necessarily “free tuition for all”, as that approach can lead to inefficient use of scarce public funds: it heavily subsidises not just those who cannot afford higher education, but also those who can. Instead, charging a moderate level of tuition fees – while simultaneously giving students opportunities to benefit from comprehensive financial aid systems – is an effective way for countries to increase access to higher education, stretch limited public funds, and promote equity by acknowledging the significant private returns that students receive from higher education. Gale and Parker (2013) found for instance that Australian students from certain target groups (particularly low SES students) appear to benefit from three forms of financial support: support to repay tuition fees, such as a deferred and income-contingent loan repayment schemes; income support while studying at university, which is means-tested and sufficient to reduce or eliminate the need to engage in paid work while studying; and funding schemes, which institutions can access to address the specific needs of target groups.

One promising approach is embodied in financial aid systems that combine means-tested grants with loans whose later repayment levels are contingent upon a graduate’s income (see Box 3.3). Australia and New Zealand have used this approach to mitigate the impact of high tuition fees, encourage disadvantaged students to enter higher education and reduce the risks of high student loan debt.

At least eight countries around the world have adopted versions of Australia’s Higher Education Contribution Scheme (HECS). The scheme typically requires students to pay some of the cost of their degrees, with the remainder funded through a government loan.

HECS was introduced in 1989 by the Australian government. The loan component is repaid through the tax system, and repayment is dependent on the borrower’s income. This arrangement is known as an income contingent loan or an ICL. The fundamental difference between ICLs and “normal” loans is that repayments occur if and only when the borrower’s income reaches a pre-determined level. If their salary never reaches that level, then no payments are ever required.

ICLs now underpin the student loan mechanism in countries such as Australia, New Zealand, Ethiopia, England, Hungary, South Africa, South Korea and Chile, with most of these countries providing finance for both tuition fees and to cover living costs. Interest rate subsidies are usually provided. It is generally agreed that these policies have worked effectively in equity, efficiency and the administrative sense.

ICL arrangements reduce repayment difficulties and provide protection against default – a potential risk with university financing because of students’ lack of collateral. If loans are not income contingent, many students will face considerable repayment burdens, and some may default.

Sources: Chapman, B. (2015), “Taking income contingent loans to the world”, University World News, 06 March 2015, Issue No. 357, www.universityworldnews.com/article.php?story=20150305123821344.

Chapman, B. (2006), Income Contingent Loans as Public Policy, The Academy of the Social Sciences in Australia, Occasional Paper 2/2006, Policy Paper # 5, www.assa.edu.au/publications/occasional/2006_No2_Income_contingent_loans.pdf.

Chapman, B. (2005), Income Contingent Loans for Higher Education: International Reform, The Australian National University, Centre for Economic Policy Research, Discussion Paper No. 491, www.cbe.anu.edu.au/researchpapers/cepr/DP491.pdf.

Higher education equity and access in Kazakhstan

Socio-economic status and participation in higher education

Kazakhstan has had difficulty in developing reliable SES information. This reflects a more general lack of data about the income levels of the population, linked in part to the presence of a substantial “grey” economy. As a consequence, there is a paucity of data related to the SES distribution of students and on the effects of SES at the school and higher education levels. Data from the Ministry of Education and Science (based on a survey of higher education institutions, to which 80 institutions replied) do indicate though that roughly two-thirds of “students from poor families” study without any financial support (i.e. pay fees) – compared to 10 percentage points fewer students in the overall student population.

Despite the lack of good SES data in Kazakhstan, there is clearly a correlation between the geographic location of students, their SES and their academic performance. In Kazakhstan, most students enter higher education – and qualify for state support – based on the results of the Unified National Test (UNT) which they sit at the end of upper secondary school. The relationship of UNT mean scores to income levels confirms a link between levels of poverty and the urban-rural divide. Rural students in Kazakhstan are more likely to be of low SES status and to perform less well on the UNT (MESRK, 2014a).

The state grants approach to financing higher education thus has a negative effect on participation in higher education by students from rural areas. Even though there is a 30% set aside of state-funded spots for rural youth, the UNT/state grant system – combined with poorer-quality rural schools that make students less prepared for the UNT – creates an inequitable financial barrier. A study by the National Center for Educational Statistics and Evaluation (NCESE, 2014) shows that UNT scores (the primary determinant of an individual’s eligibility for free university education) are correlated with regional poverty levels: in regions with high numbers of people living below subsistence level, the UNT scores were considerably lower. By way of contrast, the high-income cities of Almaty and Astana achieved the highest scores on the UNT in 2012 (NCESE, 2012).

Differences in UNT scores are also related to the language of instruction in schools – in ways that appear to be related to the rural/urban divide. In 2014, the average score on the UNT for candidates from Russian-language taught schools was 81.7%, while for students from Kazakh-language taught schools it was only 74.84% (NCESE, 2014). Those students in schools where Kazakh, Russian and English are taught appear to be comparatively advantaged over students from schools where only Russian and Kazakh are taught.

Students with a disability and other vulnerable groups

The State Program for Education Development (SPED) 2011-2020 acknowledges that inclusive education has not been well developed in Kazakhstan. About 3% of all minors in Kazakhstan are classified as having a disability (MESRK, 2010). However, according to data received from the MNERK, in 2014 students with disabilities over 18 years of age made up only about one-third of one percent of all higher education students, and two-thirds of one percent of students who were studying on a state grant. In principle, 1.2% of state-funded spaces are set aside for students with disabilities (MNERK, 2014-2015).

The higher education institutions that the OECD review team visited were poorly equipped to deal with the needs of students with disabilities. Teaching spaces were frequently inaccessible and there was little in the way of specialist equipment or facilities. Education plays a special role in assisting socially vulnerable segments of society to adapt to the expectations of modern society. According to the MNERK, approximately 98% of orphanage and foster care leavers aged 18-28 years old are enrolled in technical and vocational, higher and postgraduate education (MNERK, 2014-2015). This category of students is eligible for subsidised higher education and constitutes 1.9% of the total of all students eligible for benefits. In practice, based on data provided to the OECD review team by the Ministry of Education and Science, these students appear to make up about 0.7% of the total student population and 1.3% of students studying on state grants. They are comparatively unlikely to be studying as fee-paying students.

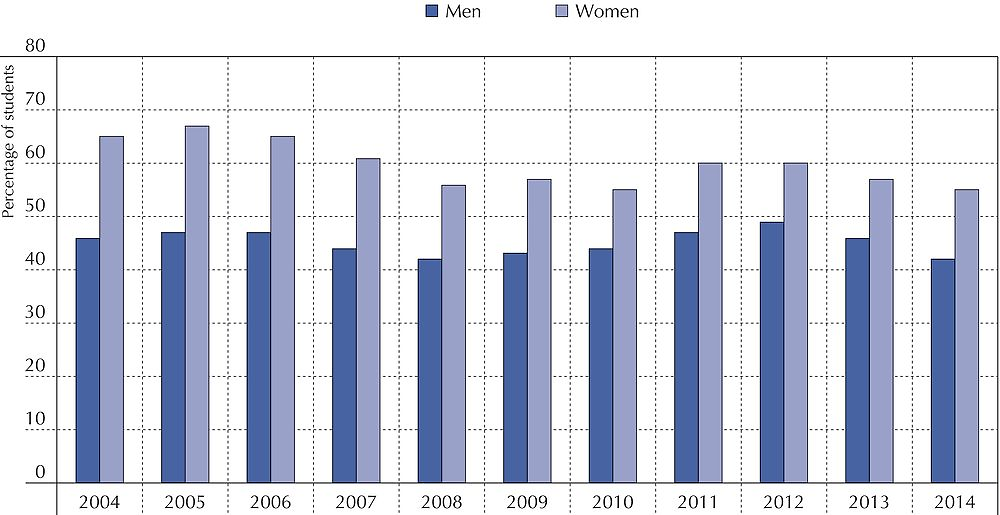

Gender

Over the period 2004 to 2014, the gross enrolment ratio1 of women in higher education in Kazakhstan was greater than that of men; it ranged from 65.18% in 2004 to 54.7% in 2014 (MNERK, 2014-15). This change needs to be seen in the context of an overall decline of 36% in higher education enrolments over the same time period (see Figure 3.2).

Sources: Ministry of National Economy of the Republic of Kazakhstan, Committee on Statistics (MNERK) (2014-2015), www.stat.gov.kz.

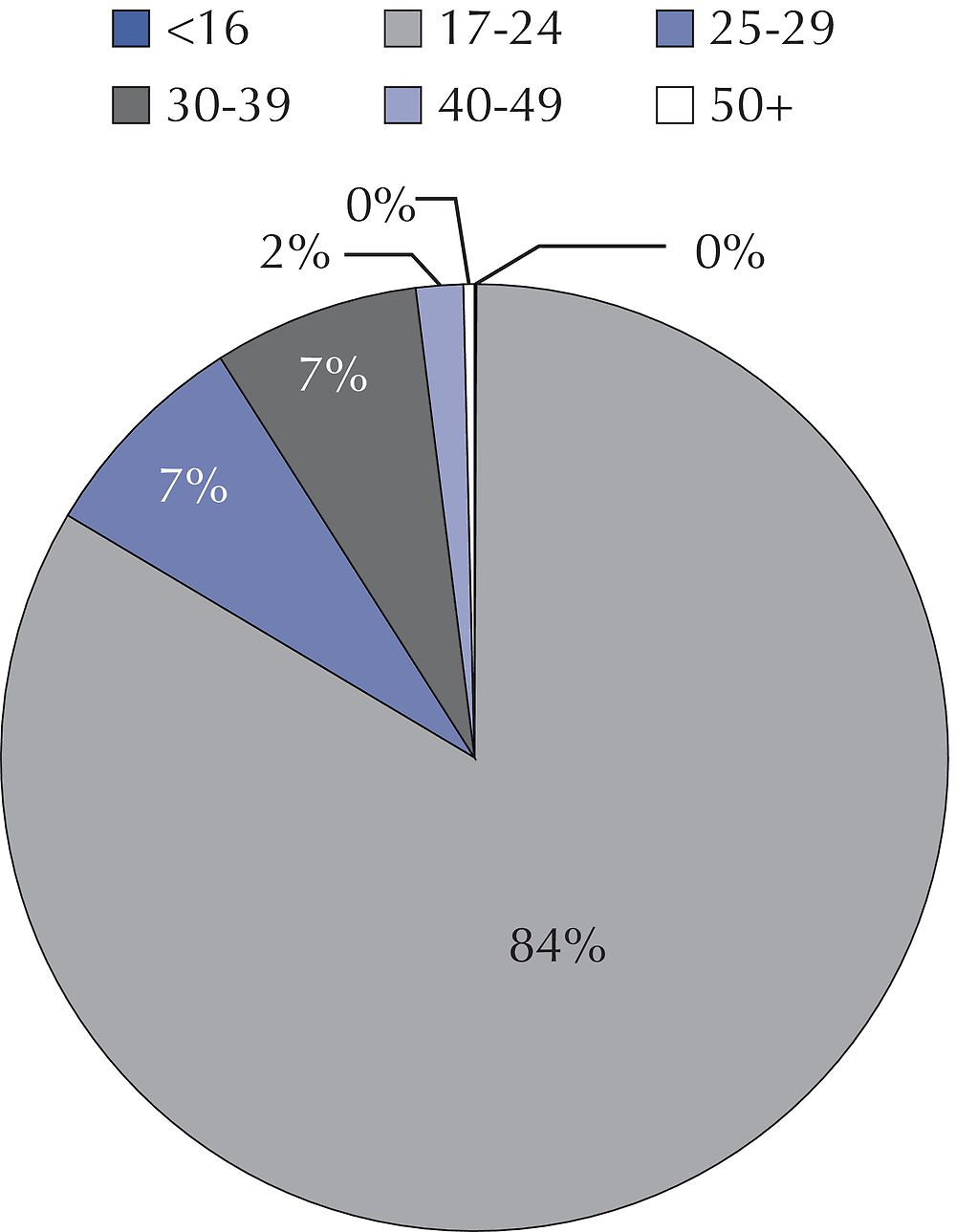

Adult and mature-aged students

Youth between 17 and 24 years of age represent the greatest number of participants in higher education in Kazakhstan (see Figure 3.3). This reflects admissions practices that recently favour school leavers. These data do not distinguish level of study, so it is not possible to comment on the proportion of older students studying at undergraduate level.

Sources: JSC Information-Analytic Center (2015), “Country Background Report”, prepared for the OECD follow-up review of higher education policy in Kazakhstan, JSC Information-Analytic Center, Ministry of Education and Science of the Republic of Kazakhstan, Astana.

The OECD review team has not been able to identify the age or gender distribution of part-time students or whether part-time students are concentrated in particular institutions or locations. The MESRK reports that 75.5% of students study full time, which is in accordance with the prescribed ratio of full-time to part-time students of 4 to 1. It appears that this ratio is applied across the sector rather than at the level of individual institution. The state prescription of a ratio of full-time to part-time study across the sector likely limits the capacity of students who face financial barriers to support themselves while studying part time. The restriction on part-time enrolment numbers also militates against older students returning to study while working full or nearly full time.

Access and equity: policy issues for Kazakhstan

Kazakhstan’s policy relating to access to higher education has emphasised the expansion of overall enrolment, with less of an effort being made to ensure equity of access and participation. Beyond the admissions set-asides for certain classes of students (people with disabilities 0.5%, rural youth 30%, people of the Kazakh nationality who are not citizens of the Republic 2%, orphans and children left without parental care 1%), little attention appears to have been paid to differences in participation rates as broken down by socio-economic background, region of residence, cultural background or disability. As a result, there have been only limited initiatives to tackle these challenges.

The Law on Education (2007) guarantees free public higher education on a competitive basis in accordance with the state educational order. However, the law’s emphasis on competition results in inequality of access in higher education: it overlooks just how important it is to have had an opportunity to participate in the kind of schooling that makes students academically competitive. The law fails to acknowledge the underlying causes and the cumulative effects of educational disadvantage, as well as issues surrounding the measurement of achievement that complicate a merit-based approach.

In 2014, the MESRK proposed reforms to improve access to higher education for all social groups. It set an ambitious target of 55% participation of the eligible population by 2016 (JSC Information-Analytic Center, 2015). Without a dramatic expansion of scholarship funds and more active improvement of the school sector, it will be some time before the 2016 target is reached. In recognition of equity challenges inherent in a merit-based admissions system, the government has also stated its intention to introduce socio-economic criteria as a determinant of eligibility for free higher education (JSC Information-Analytic Center, 2015). At the time of writing, no further detail was available on these changes.

Figure 3.4 outlines recommendations made by the 2007 OECD/World Bank Review of Higher Education in Kazakhstan. Many of these respond to issues identified in the previous section of this chapter. The table also briefly outlines responses to these recommendations.

Addressing the effects of prior schooling

The recent OECD Review of Secondary Education in Kazakhstan found that Kazakhstan has invested considerable effort in improving the capacity and the learning conditions of its primary and secondary schools (OECD, 2014b). Yet, there is still much to be done to eliminate persistent inequities in access to quality schooling and to ensure that all students have an equal chance of being prepared to enter higher education.

Sources: OECD/The World Bank (2007), Reviews of National Policies for Education: Higher Education in Kazakhstan 2007, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264033177-en.

To date, policy interventions have primarily benefitted those schools whose mandate is to nurture academic excellence. This focus has to some extent crowded out investments in meeting the needs of students who struggle academically and underachieve, and it has reinforced uneven levels of quality across the system. For instance, the distribution of teachers among schools is not well balanced. Well-qualified and highly effective teachers are less likely to work in disadvantaged schools, and more likely to work in schools for gifted students where additional resources and support are available.

The team that authored the Review of Secondary Education in Kazakhstan also judged that the biggest problem facing Kazakhstan schooling was the absence of education stakeholders’ knowledge and concern about the level of under-achievement. The report recommended actions that would tackle the “long tail” of under-achievement that is, the many students who fall in the lower part of the academic distribution. The team found little evidence of specific initiatives aimed at students who were struggling academically, who were falling behind their peers or were below average ability. All this suggests that there is a systemic problem in secondary schools that has had a significant effect on the academic achievement of many students, negatively influencing their ability to later gain entrance to – or succeed in – higher education.

A 2009 OECD review of the provision for students with special needs and disabilities identified a number of concerns relating to the extent to which these students experienced equal access to quality education (OECD/JRC, 2009). The 2014 Review of Secondary Education in Kazakhstan recognised that there was still some way to go before the country realised its aims for inclusion (OECD, 2014b). Indeed, many students with special needs and disabilities are still educated in special classes, in separate “correctional” schools or via home learning schemes rather than in mainstream schools. This has the effect of amplifying disadvantage, providing limited support and resources, inadequately accommodating their needs and restricting opportunities for social and academic development.

Kazakhstan has very few programmes and resources targeting the needs of students from a disadvantaged background or with learning difficulties. The current concept of disadvantage focuses narrowly on disabilities and extreme socio-economic disadvantage, and consequently identifies only a small number of students as eligible for support. In addition, the lack of standards for minimum school size and teacher quality mean that students in small schools and rural locations, particularly secondary students, are disadvantaged (OECD, 2014b).

At the “high” end of the education system, in 2011 there were 115 specialised secondary schools for gifted children. There is also a range of other schools for gifted children in Kazakhstan including the Nazarbayev Intellectual Schools (NIS). Kazakhstan’s emphasis on preparing top-performing students for participation in academic Olympiads and prioritising gifted children is detrimental to other students. When emphasis is placed on high performance and the elite, schools and teachers will frequently focus on enhancing the performance of the “best” students, rather than meeting the needs of lower-performing students.

Schools that cater to gifted students, such as the Nazarbayev Intellectual Schools, receive considerably higher levels of funding than mainstream schools. However, the very notion of “giftedness” that underlies these schools is somewhat problematic in the Kazakhstani context. Students from less advantaged backgrounds have limited access to extracurricular classes to prepare for admission to elite schools. This makes it likely that “gifted” schools do not necessarily attract the most academically able in the country, but rather tend to disproportionately meet the needs of a subset – those from more advantaged backgrounds.

Kazakhstan could benefit from the introduction of programmes that use university students as peer mentors who can share their discipline knowledge and experience with secondary students, support their learning and help raise their aspirations. Such programmes might include structured visits to higher education institutions that allow secondary students to experience a university class and get a sense of campus life. An example of this sort of approach, which has been used effectively with students from disadvantaged schools in Scotland, is described in Box 3.4. To be successful, such approaches require the active engagement of higher education – the support of the senior management and involvement of faculty.

The University of Edinburgh in Scotland has made widening participation one of the six themes of its strategic plan. The university is aiming to raise all school students’ awareness about the possibilities that university studies hold. To this end, it has developed a range of programmes that seek to raise awareness, builds aspirations and help students get ready for university. These include:

-

Information provision for students from targeted schools to raise their awareness of particular disciplines.

-

“Educated Pass” – a programme that works with local boys’ football teams to raise aspirations and awareness of higher education though passion for football.

-

Peer mentoring programmes for students once they enter university to help them adjust and study successfully.

The university has also developed an extensive Widening Participation website with resources and information.

Sources: The University of Edinburgh, www.ed.ac.uk/student-recruitment/widening-participation/projects.

While they are only part of a bigger solution to the problems facing many Kazakhstani schools, properly implemented digital technologies do provide numerous possibilities for delivering high-quality “just-in-time” and “just-in-case” resources to students and teachers. The proliferation of freely available, quality-assured open education resources represents a key means to upskill teachers, develop discipline-based content knowledge and provide students with access to high quality, contemporary instruction. As reported by the 2014 review, current “e-learning” practices do not extend beyond computer drill and instruction with a focus on memorisation.

Kazakhstan should expand its use of technology-enabled learning and distance education methods (in particular e-learning): at present, distance-learning often seems to take a traditional approach of students completing paper assignments and sending them back for assessment. Particular attention should be given to developing e-learning support for teachers, as well as resources that teachers can integrate into their teaching. Centrally supported repositories of digital learning assets that are curated, and that are accompanied by teachers’ guides, would provide a sustainable approach to upskilling rural teachers and enriching the curriculum. However, if digital resources are to be used effectively, then issues associated with poor access, lack of speed, and low connectivity at school and home have to be addressed.

Admission to higher education

As described above, the Unified National Test is a high-stakes examination that regulates not just admission to university but also access to state student grants. The UNT was introduced to address the risks of corruption endemic in the previous system of individual university admissions systems. However, it was frequently reported to the OECD review team that many students now focus almost exclusively on preparing for this test during their final two years of secondary school. They may strategise and look for opportunities to “play the system” – losing valuable learning time at secondary school as they focus on achieving high scores on the UNT. Moreover, it was reported to the review team that students sometimes choose courses on the basis of the availability of grants rather than on the basis of interest, passion or talent.

Coaching for the UNT is a common practice. While in principle there is nothing wrong with tutoring, in this case it has important implications for equity. Not all families are financially able to afford to pay for coaching and tutoring. The review team heard that students and families from urban areas spend more on education, including on private tutoring, than rural families. UNT preparation materials are available for sale to the public, but students must be able to afford to buy them, and they are unlikely to prepare a candidate to the same level as private or group tutoring. Staff of the National Testing Center reported that the Center offers free preparatory sessions for students. Trial testing is also available, but while helpful, these services are once again unlikely to match the benefits of private tutoring.

Redevelopment of the test to a more open UNT would help minimise the effect of coaching and teaching to the test, and thus create a fairer and more equitable playing field. The Ministry of Education’s proposed changes to the UNT that were reported to the OECD review team – and which include the use of more open-ended questions, essays and a move towards multiple-choice questions that assess higher-order thinking skills – would likely contribute to a more credible and valid instrument. The National Testing Center also told the review team that they anticipate the UNT will become completely computer-based and have the capacity to allow re-testing within the year following completion of year 11.

It has been previously reported (OECD, 2014b) that Kazakhstan intended to develop separate school leaving and university entry tests starting in 2015, but the OECD review team did not hear any further detail about this. Because of the effect of high stakes exams on the behaviour and learning of students, it is important that any high-stakes exam (such as university entrance exams) assess the types of thinking and skills that a student needs to be competitive in fast-changing modern economies and societies. If Kazakhstan moves, as reported to the review team, toward the introduction of the twelfth year of schooling, it could take that opportunity to introduce a school-leaving exam that is distinct from the separate university entrance exam. In any case, Kazakhstan should seek to implement a more valid, reliable assessment that more effectively regulates university entrance and that is more fair for students from disadvantaged backgrounds.

Although improvements to standardised testing would be a positive step, it would be desirable to supplement testing with alternative entry schemes that recognise and compensate for disadvantage and unequal schooling conditions (see Box 3.5). Such schemes might include the provision of bonus points to address disadvantage caused by rural or remote school location; alternative testing to select students from particular disadvantaged groups or locations; or recommendation schemes that identify students with academic potential who have experienced adversity during their school years. Of course, such approaches would need to include rigorous checks and balances to ensure fairness and prevent corruption. There are examples of such approaches in other countries, and there is an urgent need in Kazakhstan to implement an entry scheme that actively addresses systemic disadvantage and recognises academic potential (World Bank, 2012).

In Australia, alternative entry methods include consideration of disadvantage identified by postcode (applicants can be awarded “bonus points” depending on their home postcode); the set-aside of places in highly competitive programmes for students from disadvantaged backgrounds; and means-tested scholarships.

Australia also has a programme that allows secondary schools to identify students with academic potential, but who may have experienced adversity; it gives these students special entry. This programme is managed by a central university admissions centre. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander students may sit a specially designed alternative entry test. Students who are admitted via alternative schemes are provided with additional academic and social support.

In Sweden, higher education institutions can use alternative selection criteria for up to one-third of available places. These are normally used to select among candidates who already have the necessary formal qualifications. Special tests other than the standard university entrance exams, relevant knowledge, professional or vocational experience and other criteria relevant to the programme can be considered in these cases.

Sources: The University Admission Centre (n.d.), Alternative Entry, www.uac.edu.au/undergraduate/admission/alternative-entry.shtml; Higher Education and Research (31 May 2016), https://sweden.se/society/higher-education-and-research/

The complex test and alternate pathways to higher education

Technical and Vocational Education (VET) has a key role to play in providing the viable educational pathways and specialist training that countries need for sustainable economic development. In 2014, approximately one in every six Kazakhstanis aged 14-24 was enrolled in technical and vocational education institutions. However, rates of enrolment vary substantially by region. With only 20% of VET institutions located in rural areas, the access of rural youth to technical and vocational education is severely restricted (MESRK, 2014).

Barriers to VET access have negative consequences for their employment prospects, and are an important impediment to social and economic development. Between 2011 and 2013, the number of VET graduates decreased by more than 15% (Álvarez-Galván, 2014). Part of the challenge is that post-secondary VET in Kazakhstan has traditionally been seen as a fallback for young people who have not completed compulsory education, or who have been unsuccessful in general or higher education. The role of post-secondary VET in the education system remains somewhat unclear, and would benefit from being positioned as a stronger and more prestigious higher-level vocational option (Álvarez-Galván, 2014).

The Complex Test (CT) is the mechanism that Kazakhstan uses for managing admission to higher education, as well as eligibility for state grants for people who failed the UNT on their first attempt; for graduates of VET; and for school leavers who were not able to complete their studies or who studied in foreign schools. A student who fails the UNT must wait until the following year to attempt the CT.

The number of students sitting the Complex Test rose from 29 141 in 2011 to 78 248 in 2015. The success rate on the CT is generally low because of the reported difficulty of the test, and because most students are poorly prepared for it. In 2015, substantially fewer than half of the candidates who sat the CT scored a passing grade (NCESE, 2014). Like the UNT, the CT would benefit from an overhaul that makes it into a more meaningful assessment of higher-order thinking and skills, and better able to measure a range and depth of practical and theoretical knowledge.

The CT is a particularly important pathway into higher education for students with VET qualifications who wish to transfer into higher education. Higher education currently provides little recognition or credit transfer for students who have studied at VET colleges, so they must achieve success on the CT to enter higher education institutions. Under a former arrangement, applicants from VET who were prepared to fund their own tuition could be admitted on the basis of an interview at the higher education institution at which they wished to study; when they wished to study in an area closely related to their VET studies, they could be admitted to the second year of the undergraduate degree programme. There do not appear to be any substantial benefits from the closure of this pathway, which (according to reports make to the OECD review team) seems to have functioned effectively as a viable route from VET to university study.

The OECD review team was not able to locate any data that could conclusively show whether or not the introduction of the CT requirement has had any impact on the rates of transfer to higher education. Nevertheless, it is clear that its implementation has raised an additional barrier to higher education participation and that it sends a message which undervalues technical education. The CT itself needs reform. At the same time, development of alternative admission schemes would create a more equitable environment for VET students – and also allow individuals who are older or have missed out on education in some way, to demonstrate their potential and thus gain admission to higher education.

In summary, Kazakhstan should explore ways to promote expanded and systematised recognition of VET qualifications in higher education; the recognition and formalisation of credit transfer; and, in particular, it should consider the removal of the requirement that students sit the CT when they are already successful graduates of a relevant or similar VET course. To this end, more could be done to encourage higher education and VET institutions to develop partnerships across sectors and regions, and to put in place articulation agreements that facilitate transfer between institutions and sectors.

Financial aid

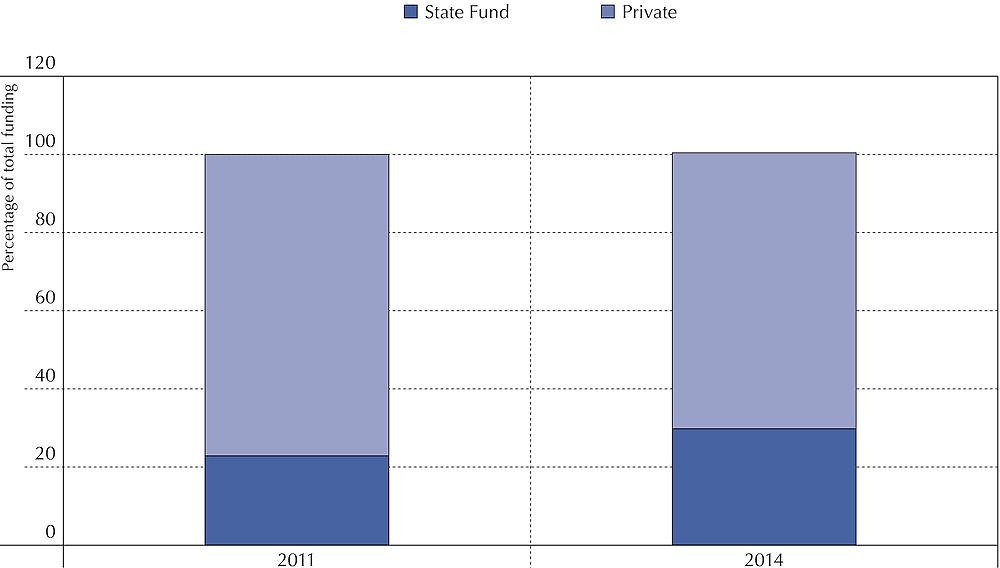

The absence of needs-based financial aid is a major barrier to access to higher education in Kazakhstan. Students primarily pay for their education through personal funds and state grants. However, state grants only provide funding for around one-quarter of higher education students.

Grants

As Chapters 2 and 6 also discuss, Kazakhstan’s state grants are a voucher-type system. Funds for higher education places are allocated to the recipient (the student), rather than the supplier of education services (the institution). The state contribution to higher education in Kazakhstan is low: in 2013 public expenditures on higher education in Kazakhstan were just 0.3% of GDP (NCESE, 2014). There is thus a heavy reliance on private sources of funding to support higher education.

In 2014, an estimated 73% of Kazakh higher education students funded their participation in higher education using their own or family funds (see Figure 3.5) (MNERK, 2014-2015). Meanwhile, tuition rates have increased at a faster rate than income levels across the population (Nazarbayev University School of Graduation, 2014). Institutions are required to ensure that the tuition levels do not fall below those of the state education grant. This has a perverse effect: the state cannot increase public funding of higher education without raising new affordability challenges for students who must pay for their studies.

Minimum grant/tuition fee levels are specified by the relevant ministry, and vary somewhat across institutions and disciplines. Typical tuition levels at public institutions range from roughly KZT 300 000 to KZT 700 000 or roughly USD 900 to USD 2 000 at mid-2016 conversion rates. Some private institutions charge as much as three times the upper end of that scale, though.

Free higher education is available on a competitive basis only when the individual is participating for the first time at a particular level. Public educational grants give selected students access to the institution of their choice, and the major share of grants are allocated to state education institutions.

In order to regulate the training of specialists, the state (through the MESRK) draws up an order each year, to fund the number of places required to educate specialists in areas the state determines to be in demand. Thus in certain fields, such as law, as few as one in ten bachelor-level students studies on a state grant. In other fields, such as engineering and technology, roughly six in ten students hold a grant – and in agricultural sciences (a small field of study), as many as eight in ten do (data provided by the JSC Information-Analytic Center based on a survey of higher education institutions).

Sources: Ministry of National Economy of the Republic of Kazakhstan, Committee on Statistics (MNERK) (2014-2015), www.stat.gov.kz.

Special grant set-asides have been introduced for students from a range of backgrounds: rural students; those in priority social and economic disciplines; Kazakh ethnic minorities; Kazakhs who are citizens of another country; students with a disability; and orphans and children without parental support. In the case of equal scores on the UNT and CT, orphans and children who need support are given preferential treatment.

Planning is reportedly underway for the development of new special programmes to provide additional access to higher education for students from rural areas and low-income families; planning for measures like this, that somewhat counterbalance the equity effects of the UNT, should be accelerated. Such measures need to be complemented, though, by approaches designed to improve the quality of teaching and schooling in rural and regional areas.

The government’s “Serpin 2050” educational grant programme began in 2014 and currently supports education at seven higher education institutions (with plans to expand this number). Serpin provides incentives for student mobility which are designed to reduce unemployment in the southern regions (which have a young, growing and often poorer population), and to address skills and labour shortages in certain western, eastern and northern regions. Serpin’s success will depend on the willingness of students from the South to remain, over the longer term, in the areas to which they move for their studies. As Serpin is quite new, its success remains to be seen. The OECD review team was not able to determine whether the policy model behind the programme has adequately estimated the long-term willingness of Kazakhstanis to resettle in other parts of the country.

Other grants and discounts

Many higher education institutions have introduced their own discounts for various groups of students. Fees may be reduced by between 15% and 50% for high-achieving students, elite athletes, students with dependents, and where two or more students come from the same family. Data provided by the JSC Information-Analytic Center in May 2016 suggest that nearly one in twelve students may be in receipt of such discounts – with students from poor families somewhat more likely to receive them.

Employers provide grant funding for students – with these grants by far the most common in the fields of engineering and technology. Higher education institutions themselves currently have only limited opportunities to raise revenue and to use this to offer additional financial support to students in need. Kazakhstan’s highly centralised financial regulations do not, for instance, allow higher education institutions to establish endowments – which, with appropriate safeguards, have proven to be an effective approach for funding targeted initiatives in a number of countries. The restrictions in Kazakhstan limit higher education institutions’ ability to access philanthropy and to develop active partnerships with industry that could support disadvantaged students.

Student loans and savings schemes

Student aid schemes are very limited in scope, volume and impact. The introduction of a student loans scheme in 2005 has failed to gain real traction. Only 6 000 students have taken up the loan option in the ten years since its introduction (Nazarbayev University School of Graduation, 2014).

Loan availability is dependent on a risk assessment that includes measures of academic performance. Educational loans are provided by second-tier banks and the loan principal is guaranteed by the JSC Financial Center of the Republic of Kazakhstan (JSC Information-Analytic Center, 2015). In practice, this guarantee process means that many students cannot meaningfully apply for “official” student loans, as they would be seen as too great risk. The public student loan system is still tainted by a policy initiative in the 1990s which had the state directly provide loans to students. This programme had extremely high default rates; the bad debts are still being actively collected.

Those who are approved for a state-guaranteed loan still need co-signers. It was reported to the OECD review team that a significant percentage of “guaranteed” borrowers do not in the end receive loans. Sometimes the bank breaks off contact with the borrower, and sometimes a co-signer cannot be found. It was also reported to the review team that the typical credit recourse of students who need to borrow is to private loan markets, where interest rates may be upwards of 25%.

The State Educational Accumulation Scheme (SEAS) introduced in 2013 may hold promise but suffers from design defects. Under the SEAS, the government pays an additional interest premium on educational savings accounts thereby encouraging parents to accumulate savings to pay future tuition fees for their children. Where the amount accumulated is insufficient to pay the tuition fee, an educational loan can be provided for the balance. In 2015 there was a minimum introductory contribution of KZT 5 946 and a maximum term of twenty years. The state premium is currently 5% per annum. There is a small additional premium of 2% for orphans, people with disabilities, children from large families and students from families with income below the subsistence minimum.

The Finance Center of the Ministry of Education and Science reported to the OECD review team that, since the inception of the SEAS in 2012, only 11 000 people have created deposits under the scheme – a figure which is far below the 500 000 depositors predicted at the programme’s outset. Kazakhstanis’ uncertainties about the economy (given rising inflation and the risk of further currency devaluation) reduce the appeal of a savings vehicle denominated in tenge.

There is also a cultural bias implicit in this scheme: it will be more attractive to those families who have the financial capacity to save and a predisposition towards doing so – and it will thus use public funds to encourage behaviour that may well have happened anyway. However, it will be less attractive for lower SES households – both because they often lack funds to save and because they are less likely to aspire to higher education for their children. Yet it is precisely these families that stand to benefit the most from an effective targeted allocation of incremental public funding.

Other financial supports

To promote lifelong learning, the government has created incentive schemes for employers to provide support for employees who want to study at higher education level. This involves companies developing their own educational and training programmes. These social partnership arrangements seem to be slow to develop. As reported by faculty and employer groups to whom the OECD review team spoke, there appears to be either a lack of trust between institutions and employers or a lack of understanding of each other’s perspectives. In some countries, programmes such as these have had a substantial positive effect on participation in higher education, particularly in encouraging older learners to engage in study. Approaches have included tax breaks for employers who support staff in formal study, and formal educational collaborations between industry and universities.

In developed countries such as the United States and Australia, for instance, there are a range of emerging partnerships in which universities work with employers to develop specialised qualifications for staff. For example IBM has partnered with 28 universities and business schools to develop a curriculum on big data. In Australia, the financial services firm AMP and Griffith University have collaborated to create university-industry postgraduate degrees that combine theoretical coursework with experience as a financial adviser (Griffith University, 2016).

Schemes to encourage participation

While financial barriers to participation are substantial, the influence of attitude and aspirations cannot be underestimated. Educational inequity has become entrenched in Kazakhstan. The systemic impediments of lower quality, and less well-resourced schooling for rural and low SES students have a direct effect by limiting opportunities for academic achievement. These impediments also have reduced individuals’ opportunity to develop a mindset that understands the potential benefits of higher education.

The OECD review team observed very little systematic attempt in Kazakhstan to address this issue of low aspirations. It does not help that the current method of managing admission to higher education fails to recognise or address adversity or disadvantage in a young person’s life. There are few if any enabling and bridging courses that might allow students to address gaps in their knowledge and develop knowledge and skills that are a pre-requisite for their course of study.

The team also observed few examples of study and learning skills support available for students at higher education institutions, and students with whom the team spoke noted that there was little formal provision of study support. The lack of additional support schemes can only further reduce the educational achievement of young Kazakhstanis.

Flexible study

The dominant approach to higher education is through full-time study. This can discourage participation of students from disadvantaged and low SES backgrounds who may, for instance, not be able to pay the “opportunity cost” of foregone wages if they engage in full-time study.

Kazakhstan’s state classification of full-time, part-time and evening, distance education and external studies does not align with the definitions applied to such terms outside the country. In Kazakhstan, “part-time education” is intensive training of around one month per year followed by an examination; school leavers are excluded from this option. Enrolments in this form of study have fallen sharply over the last several years.

In many other countries, the concept of part-time study involves a student carrying a subject load that is less than that required to complete a qualification in the minimum period of time. Part-time study may be offered by classes in the evenings, weekend study and intensive periods of study often over a summer. Alternatively, students may simply carry a lighter subject load. These options all provide a student with opportunity to balance university study with work or family commitments. However, not all countries recognise part-time study, and there is no universal definition. Many government policies apply different definitions of part- or full-time study for the purposes of funding decisions.

Initiatives that offer increased opportunities for Kazakhstani students to study part-time could increase the accessibility of higher education. These might be enabled by new technologies, in the form of open universities for example (Box 3.6), but that does not necessarily have to be the case. Changes to the funding of higher education places (including financial aid initiatives for part-time study) could also facilitate increased levels of participation in higher education by students from disadvantaged and low SES backgrounds.

Open Universities such as the Open University of the United Kingdom, Turkey’s Anadolu University, Indira Ghandi National Open University (India) and Athabasca University (Canada) have demonstrated how distance education and open entry can dramatically expand access to higher education. Drawing on the expertise of domestic and foreign faculty from quality institutions, these institutions make education available at a reasonable cost through print and digital resources supplemented by tuition. They make use of techniques such as credit transfer from other institutions, assessment and recognition of prior learning and challenge for credit. Quality higher education is provided at scale to all who wish to participate.

Sources: ICDE (International Council on Distance and E-learning), www.icde.org/.

Athabasca University www.athabascau.ca/; www.universityadmissions.ca/open-distance-universities-in-canada/.

The availability of data for policy purposes

To design and implement approaches that address inequalities in access to higher education, policy makers first need good data and information on these inequalities. However, given the difficulties that the OECD review team had in obtaining reliable data that it required for this chapter’s analysis, it appears that Kazakhstan is not systematically tracking, monitoring and analysing the performance of students on the basis of their geographic and socio-economic backgrounds. It is not following students through primary and secondary education, and into any post-secondary studies they may engage in. Policy makers thus lack reliable analysis of the higher education participation and completion rates of students from low SES or disadvantaged backgrounds, and of the factors that contribute to these outcomes. This represents a major limitation on the business intelligence of the higher education system and of the education system more generally. It is enough, in itself, to substantially hinder efforts to enhance access and equity.

Recommendations

This Review recommends that Kazakhstan:

Reform the system of state grants and student loans. Ensure that there are viable mechanisms for supporting students from poorer families and from rural areas, from all parts of the country.

-

The amount of funding available to support higher education participation should be increased. The number and value of grants is small compared to the number of students who might benefit from higher education. This creates a sharp discontinuity between a minority of students who are able to access higher education free of charge and a majority who pay full tuition fees.

-

A significant amount of grant funding should be allocated to means-tested financial support, in order to enhance equitable access to higher education. The current system advantages those who are already in a comparatively privileged position, and wastes public funds in ways that are particularly problematic given Kazakhstan’s fiscally constrained environment.

-

A shift in grant funding policy should be complemented by student loan systems reforms to make loans more accessible and affordable to students who are not in receipt of a grant. Kazakhstan should, in particular, consider the potential for modified terms of loan repayment, including incremental repayment through an income contingent loans programme. Such lending should include a component for living expenses: students need realistic amounts of funding to cover their living costs while in higher education.

-

Reform of state policy could encourage the establishment of endowments at higher education institutions. This could, over time, provide institutions with a potential source of funds that they might use to support disadvantaged students. This approach would help systematise the role of employers in supporting students. State incentives could encourage these contributions.

-

The various approaches detailed above are unlikely to be cost neutral. However, given Kazakhstan’s low level of public funding of higher education, and given the fact that public funding mostly flows to higher education institutions via students themselves, these changes to student financial assistance are not unreasonable. To scale back costs, more emphasis could be put on affordable loans with innovative repayment conditions, as opposed to grants.

-

Effective implementation of many of the above courses of action will require better measurement of socio-economic status in Kazakhstan. Current tax data only provide partial information, and the state should develop a more comprehensive approach to measuring SES (e.g. parental occupation and education or postal code equivalent).

Reform the relationship between state grants and tuition policy.

-

Decouple university tuition fees from state grants levels. The current situation whereby the university fee cannot be less than the state grant (i.e. if the grant is raised, fees must also be raised) is not sustainable. Such an approach makes it impossible to increase per student public funding without at the same time generating new affordability burdens and creating further barriers to participation.

Improve the quality of primary and secondary schooling.

-

Expand incentives to attract and retain quality teachers to rural and disadvantaged schools. These may include travel and housing subsidies, sign-on and retention bonuses, salary enhancements, and educational scholarships for family members.

-

Improve conditions in rural and disadvantaged schools – including physical infrastructure, educational resources, and social support for staff and students.

Increase efforts to raise the educational aspirations of students in rural areas and from low SES backgrounds.

-

Public investments will be required, but incentives should also be directed towards employers to encourage their contribution to these schemes.

-

Any publicly funded schemes should be required to develop and share full documentation about their procedures and the resources they use. This would help enable the scaling up of successful approaches.

-

Align these outreach measures with scholarship programmes to multiply their effect.

Expand the use of technology-enabled learning and distance education methods (in particular e-learning) in order to provide high-quality learning opportunities for students in rural areas.

-

Pay particular attention to e-learning support for teachers, including tools that teachers can integrate into their teaching. Centrally supported repositories of digital learning assets that are curated and accompanied by teachers’ guides could provide a sustainable approach to help upskill rural teachers, enrich the curriculum, and thus better prepare students for higher education.

-

Expansion of e-learning in higher education institutions would provide greater flexibility for students who must work while studying, and help ensure that students who are encountering difficulties have access to supports and remedial resources.

Continue to reform the Unified National Test (UNT), so that it is an effective part of a higher education admissions system that equitably recognises the abilities of prospective students.

-

Current efforts at revision, aimed at making the UNT a more reliable and valid test, should be accelerated.

-

Pursue the development of separate tests to assess school completion and university admission.

-

Equity would be enhanced if there were a central mechanism to take account of the ways in which educational disadvantage and adversity interact with the UNT. For instance, to address the issues created by a universal test, an agreed upon table of “bonus points” might be applied to the UNT score of candidates from low SES areas and specified disadvantaged backgrounds. Alternative ways of assessing preparedness for higher education might be considered as well.

-

An expanded system of financial supports should also be provided (based on need) for successful students from these special categories.

Further develop mechanisms that recognise and provide credit for VET qualifications, in order to better take advantage of the training that occurs in VET colleges and to benefit from the potentially close relationship between technical and higher education.

-

Approaches should include formalised credit transfer, recognised articulation pathways and partnerships between universities and VET colleges. These will enable movement and minimise barriers to the transition from one sector to another. They can also be used to facilitate greater access to higher education for students who may not have performed well on the UNT, as well as mature students.

Improve data systems to better understand system performance in the areas of access and participation. Commit to establishing robust and reliable data regarding students of low socio-economic status.

-

Measures of employment, starting salaries and career progression will provide valuable information about the performance and effects of higher education.

-

In particular, students of low SES and other equity groups should be clearly identified, with their progress tracked throughout their studies and post-graduation.

References

Álvarez-Galván, J. (2014), A Skills beyond School Review of Kazakhstan, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264221826-en.

Athabasca University, www.athabascau.ca/.

Bowes, L. et al. (2013), International Research on the Effectiveness of Widening Participation, Higher Education Funding Council for England, www.hefce.ac.uk/media/hefce/content/pubs/indirreports/2013/WP,international,research/2013_WPeffectiveness.pdf.

Bridges to Higher Education (2016), www.bridges.nsw.edu.au/home.

Canning, M. et al. (2013), Roadmap for the Development of Education in Kazakhstan. Higher Education Roadmap Recommendations, www.gse.upenn.edu/pdf/irhe/roadmap_kazakhstan.pdf.

Chapman, B. (2015), “Taking income contingent loans to the world”, University World News, 06 March 2015, Issue No. 357, www.universityworldnews.com/article.php?story=20150305123821344.

Chapman, B. (2006), Income Contingent Loans as Public Policy, The Academy of the Social Sciences in Australia, Occasional Paper 2/2006, Policy Paper # 5, Canberra, www.assa.edu.au/publications/occasional/2006_No2_Income_contingent_loans.pdf.

Chapman, B. (2005), Income Contingent Loans for Higher Education: International Reform, The Australian National University, Centre for Economic Policy Research, Discussion Paper No. 491, Canberra, www.cbe.anu.edu.au/researchpapers/cepr/DP491.pdf.

Chapman, B., T. Higgins and J. Stiglitz (eds.) (2014), Income Contingent Loans: Theory, practice and prospects, Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke and New York.

Department for Business Innovation and Skills (2015), The Contribution of Further Education and Skills to Social Mobility, Research Paper No. 254, October 2015, London, www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/466420/BIS-15-579-contribution-of-further-education-and-skills-to-social-mobility.pdf.

Department for Business Innovation and Skills (2013), The Benefits of Higher Education Participation for Individuals and Society: Key Findings and Reports “The Quadrants”, Research Paper 146, October 2013, www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/254101/bis-13-1268-benefits-of-higher-education-participation-the-quadrants.pdf.

Ferguson, H. B., S. Bovaird and M.P. Mueller (2007), “The impact of poverty on educational outcomes for children”, Paediatrics and Child Health, October, Vol. 12, No. 8, pp. 701-706, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2528798/.

Gale, T. and S. Parker (2013), Widening Participation in Australian Higher Education, Report submitted to HEFCE and OFFA, www.ncsehe.edu.au/publications/widening-participation-australian-higher-education/.

Garranger, M. and P. MacRae (2008), Building Effective Peer Mentoring Programs in Schools: An Introductory Guide, Mentoring Resource Center, Folsom, CA, http://educationnorthwest.org/sites/default/files/building-effective-peer-mentoring-programs-intro-guide.pdf.

Griffith University, “AMP financial planning degrees” www.griffith.edu.au/business-government/finance-financial-planning/what-can-i-study/amp-financial-planning-degrees.

Higher Education Funding Council for England (2015), Delivering Opportunities for Students and Maximising their Success: Evidence for Policy and Practice 2015-2020, www.hefce.ac.uk/media/HEFCE,2014/Content/Pubs/2015/201514/HEFCE2015-14.pdf.

Higher Education and Research (31 May 2016), https://sweden.se/society/higher-education-and-research/.

JSC Information-Analytic Center (2015), “Country Background Report”, prepared for the OECD follow-up review of higher education policy in Kazakhstan, JSC Information-Analytic Center, Ministry of Education and Science of the Republic of Kazakhstan, Astana.

International Council on Distance and E-learning, www.icde.org/.

James, R. (2007), “Social Equity in a Mass, Globalised Higher Education Environment: The Unresolved Issue of Widening Access to University”, Centre for the Study of Higher Education, Melbourne, http://web.education.unimelb.edu.au/news/lectures/pdf/richardjamestranscript.pdf.

KPMG (2013), Economic Evaluation of the Australian Indigenous Mentoring Experience Program Final report, Australian Indigenous Mentoring Experience (AIME), Government Advisory Services, http://files.aimementoring.com/pdf/aime-2013-kpmg-report.pdf.

Law of the Republic of Kazakhstan, of 27 July 2007, No. 319-III ZRK, About education, last edition, 9 April 2016.

MESRK (2014), Youth of Kazakhstan, National Report Ministry of Education and Science of the Republic of Kazakhstan, Council for Youth Policy, Science Research Centre “Youth”, Republic of Kazakhstan, http://ortcom.kz/media/upload/1/2015/10/31/b9a9b0397ae4c967b709463b1bab063e.pdf.

MESRK (2010), The State Program of Education Development in the Republic of Kazakhstan 2011-2020, RK Presidential Decree as of 7 December 2010, Number 1118.

MNERK (2014-2015), Committee on Statistics (2014-2015), www.stat.gov.kz.

NCESE (2014), “Statistics of education system of the Republic of Kazakhstan”, National Collection, National Center for Educational Statistics and Evaluation http://iac.kz/en/analytics/statistics-education-system-republic-kazakhstan-national-collection.

(NCESE) (2012), “Statistics of education system of the Republic of Kazakhstan”, National Collection, National Center for Educational Statistics and Evaluation, http://iac.kz/en/analytics/statistics-education-system-republic-kazakhstan-national-collection.

Nazarbayev University Graduate School of Education (2014), Development of Strategic Directions for Education Reforms in Kazakhstan for 2015-2020, Diagnostic Report, Indigo Print, Astana, http://nur.nu.edu.kz/bitstream/handle/123456789/335/DIAGNOSTIC%20REPORT.pdf.

NSW Education Department (2015), “Benefits of teaching in rural and remote NSW”, www.teach.nsw.edu.au/exploreteaching/high-demand-locations/benefits-of-teaching-in-rural-and-remote-nsw.

OECD (2016), Low-Performing Students: Why They Fall Behind and How To Help Them Succeed. PISA, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264250246-en.

OECD (2015), In It Together: Why Less Inequality Benefits All, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264235120-en.

OECD (2014a), Education at a Glance 2014: OECD Indicators, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/eag-2014-en.

OECD (2014b), Reviews of National Policies for Education: Secondary Education in Kazakhstan, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264205208-en.

OECD (2013), OECD Education at a Glance: Highlights 2013, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/eag_highlights-2013-en.

OECD (2012a), Equity and Quality in Education: Supporting Disadvantaged Students and Schools, OECD Publishing Paris. https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264130852-en.

OECD (2012b), OECD Education at a Glance: Highlights, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/eag_highlights-2012-en.

OECD (2008), Tertiary Education for the Knowledge Society, Volume 2, Special Features: Equity, Innovation, Labour Market, Internationalisation, OECD Publishing, Paris, www.oecd.org/education/skills-beyond-school/41266759.pdf.

OECD/JRC (2009), Students with Disabilities, Learning Difficulties and Disadvantages in the Baltic States, South Eastern Europe and Malta: Educational Policies and Indicators, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264076860-en.

OECD/The World Bank (2007), Reviews of National Policies for Education: Higher Education in Kazakhstan 2007, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264033177-en.

Open and Distance Universities in Canada, www.universityadmissions.ca/open-distance-universities-in-canada/.

Redmond, G. et al. (2014), Intergenerational mobility: new evidence from the Longitudinal Surveys of Australian Youth, National Centre for Vocational Education Research (NCVER), Adelaide, www.ncver.edu.au/publications/publications/all-publications/intergenerational-mobility-new-evidence-from-the-longitudinal-surveys-of-australian-youth.

Reisberg, L. and D. Watson (2011), “Access and Equity” in P. Altbach (ed.), Leadership for World-Class Universities: Challenges for Developing Countries, pp. 187-204, Routledge, New York.

The University Admission Centre (n.d.), Alternative Entry, www.uac.edu.au/undergraduate/admission/alternative-entry.shtml.

The University of Edinburgh, www.ed.ac.uk/student-recruitment/widening-participation/.

World Bank (2012), Kazakhstan - Student Assessment, Saber Country Report, www-wds.worldbank.org/external/default/WDSContentServer/WDSP/IB/2013/08/12/000356161_20130812163634/Rendered/PDF/799380WP0SABER0Box0379795B00PUBLIC0.pdf (accessed 25 April, 2016).

Note

← 1. A gross enrolment ratio is the ratio of the number of students enrolled in technical, vocational and university education to the total population aged 18-22.