Chapter 1. Higher education in Kazakhstan1

Prior to 2014, Kazakhstan’s story had been one of dramatic economic expansion. However the benefits of growth have not been shared equally and there are significant wealth disparities, especially between urban and rural areas. Kazakhstan performs better on the dimensions of well-being that are more closely associated with income. Recent market volatility has emphasised the risks of resource dependence, highlighting the need for economic diversification. Development of the higher education sector is crucial for Kazakhstan to address its diversification challenge. Its highly centralised top-down system of governance is reflected in the education system. A new State Programme for Education and Science Development 2016-2019 (SPESD) for 2016-19 lays out the current strategy for the education sector. While basic education is quasi-universal and the level of educational attainment is comparable to OECD levels, the average quality of schooling is low, and funding remains below international standards. Despite the significant reforms that Kazakhstan has undertaken, there remains substantial room to improve its effectiveness and thereby enhance learning outcomes.

Economic and political context

The Republic of Kazakhstan is a landlocked middle-income country spanning Europe and Asia. It is the ninth-largest country in the world by land surface, but its population density is low given that it has only 17.5 million inhabitants (estimation of the population in 2016). The Republic is bordered by the Russian Federation to the north, the Caspian Sea to the west, People’s Republic of China to the south-east, the Kyrgyz Republic and Uzbekistan to the south, and Turkmenistan to the south-west.

Kazakhstan achieved independence in 1991. With its long history of centralised planning, the country’s transition to a more market-oriented economy was unstable and disruptive. During the 1990s, it experienced hyperinflation, the loss of more than 1.5 million jobs and a dramatic decline in real gross domestic product (GDP) (OECD, 2016a). This was accompanied by significant emigration.

Recent economic performance

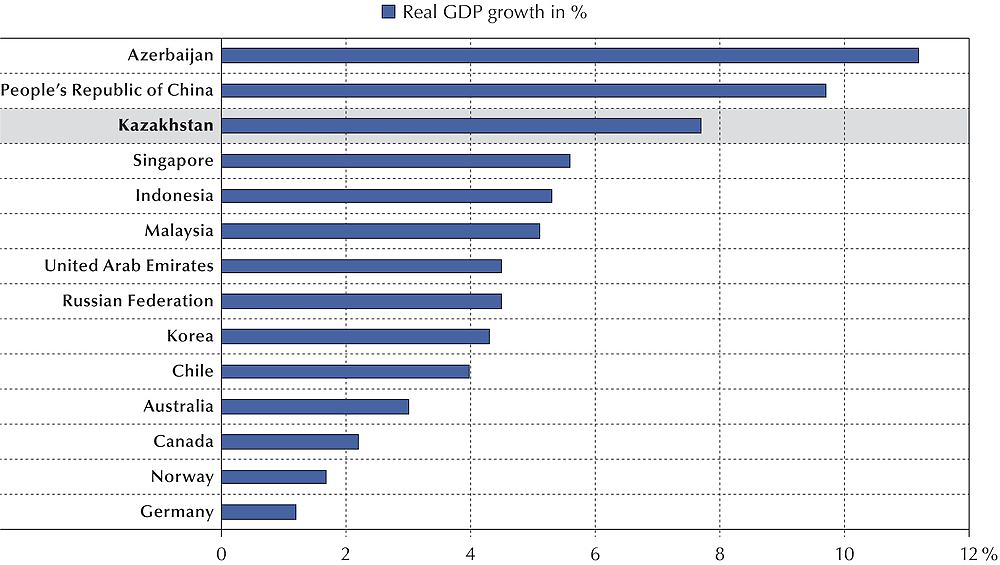

For most of this century, Kazakhstan’s story has been one of dramatic economic expansion. As demonstrated in Figure 1.1, GDP growth from 2000 to 2014 averaged an impressive 8% per year. Between 2001 and 2013, Kazakhstan more than doubled its GDP per capita to around USD 13 000 at current market exchange rates. This growth can largely be attributed to rising prices for Kazakhstan’s leading exports – mainly oil, metals, and grain. In 2013, the largest sectors of Kazakhstan’s economy (in terms of share of GDP) were wholesale and retail trade, natural resource extraction, real estate, transportation and storage, construction and agriculture. Together these six sectors made up more than 50% of Kazakhstan’s GDP (OECD, 2016a).

Sources: World Bank (2014), World Development Indicators (database), http://data.worldbank.org.

The benefits of growth have not been shared equally and there are significant wealth disparities among Kazakhstan’s regions. In 2014, the national GDP per capita at USD 13 154 was three times higher in the western, oil-rich region of Atyrau (USD 39 072) and more than twice lower than the national average in Almaty city (USD 29 286). However, South Kazakhstan’s GDP per capita (USD 4 775) was just one-third of the national average (OECD, 2016a).

Dependence on natural resources

The importance of extractive industries in Kazakhstan’s economy cannot be overstated. Due to increases in both production and prices, the oil and gas sector and related activities came to make up 25% of GDP during the early 2000s and almost 35% during 2005-08. In recent years the sector’s share of GDP has fallen, but it still accounts for roughly two-thirds of exports and approximately one-third of budget revenues (OECD, 2016a).

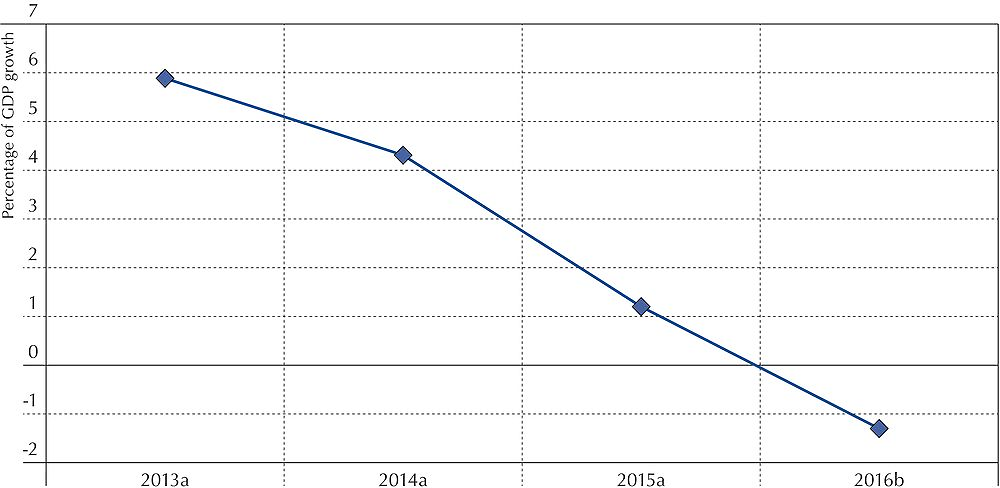

Kazakhstan’s government has used resource-related public revenues to establish a sovereign wealth fund, Samruk-Kazyna, whose goals are to enhance economic competitiveness and sustainability, and to mitigate the impact of external shocks on domestic development. Yet even with the fund in place, Kazakhstan’s economy has felt the effects of external shocks – and in particular, of the recent dramatic decline in the price of oil (from USD 110 per barrel in June 2014 to under USD 50 in June 2016) (OECD, 2016a). GDP growth slowed from 5.9% in 2013 to 4.3% in 2014 and to 1.2% in 2015. The economy is expected to contract in 2016 (Figure 1.2). This would be the first annual fall in real GDP since the Russian financial crisis of 1998 (Intelligence Economist Unit, 2016). An economic slowdown in the People's Republic of China and the Russian Federation, two of Kazakhstan’s primary trade partners, has highlighted the structural weaknesses in Kazakhstan’s economy. Reflecting this economic turmoil, the value of the country’s currency, the tenge, has fallen sharply.

Notes: Rates from 2013 to 2015 are the actual rates (a); rates for 2016 are The Economist Intelligence Unit’s forecasts (b).

Sources: International Monetary Fund (2016), International Financial Statistics; Intelligence Economist Unit, http://data.imf.org/?sk=388DFA60-1D26-4ADE-B505-A05A558D9A42.

Kazakhstan’s reliance on natural resources has taken a toll on the environment. With water shortages and considerable pollution, Kazakhstan’s fragile ecology is vulnerable to the effects of climate change. Over 75% of the country’s land is used for agriculture, making reliable access to water an ongoing concern – especially in regions like Central Kazakhstan. In recognition of its economy’s reliance on natural resources, and of the impact this reliance has on the environment, Kazakhstan has recently been investing in sustainable, renewable energy sources and in better management of its water, land, air and other natural resources (OECD, 2016a).

Other sectors

Kazakhstan has long recognised that its significant dependency on oil and other extractive industries means that it needs to diversify its economy. In recent years, growth in manufacturing and knowledge-intensive services has helped with diversification. However, manufacturing in Kazakhstan is not as developed as in many other emerging economies or in many advanced resource-rich countries: manufacturing accounts for just 11% of GDP and employs 5% of the labour force. The fastest-growing manufacturing sectors include transportation equipment, chemicals and pharmaceuticals, rubber, refined petroleum and food processing. Employment in knowledge-intensive services –including information and communications technology (ICT), finance and professional services – has also increased in recent years (OECD, 2016a).

In Kazakhstan, public and state-owned entities still account for approximately one-third of GDP. Since independence, privatisation efforts have led to a larger private sector, but this contains many big conglomerates stretching across multiple areas of activity. As a result, there is a powerful business class with enough political influence to oppose market reforms that threaten its interests (OECD, 2016a).

Kazakhstan’s weak financial sector is a significant constraint on private business development. Bank lending is an important source of financing for firms, but lending growth has been modest. Compared to similarly situated countries, Kazakhstan ranks low on key financial indicators such as the size of the stock market and local capital markets.

Small-and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) account for roughly 20% of GDP, a comparatively low share by international standards. They nonetheless play an increasing role in job creation, accounting for 30% of total employment as compared to 26% a decade ago (OECD, 2016a). Business climate constraints and limited access to finance raise challenges for the further development of Kazakhstan’s SMEs. However, a number of programmes have recently been implemented to increase SMEs access to finance.

Kazakhstan has taken many steps to improve its business climate and lower regulatory burdens. On the “ease of doing business” measures, Kazakhstan ranks 77th out of 189 countries but has lost 27 places since 2014 (World Bank, 2016). There remains ample room to encourage entrepreneurialism and private sector growth.

The labour market

Kazakhstan’s labour force utilisation has increased considerably over the course of this century, and is in line with rates in many advanced economies. From 2000 through 2013, the labour force participation rate rose from 77% to 80% and the unemployment rate dropped from 10% to 4% (OECD, 2016a). Since there is little room for further increases in labour force participation rates, economic growth is more likely to come from a shift towards more productive jobs and more productive sectors.

Kazakhstan’s agricultural sector employs almost one-quarter of the labour force but only contributes 5% of total GDP. Another quarter of all workers are employed in the wholesale and retail trade, and another quarter in the construction sector. Though the extractive sector has a significant impact on GDP, it employs just 3% of all workers. Manufacturing employs approximately 5%, while the knowledge-intensive services such as ICT, finance, insurance, and professional, scientific and technical services collectively employ around 8% (OECD, 2016a).

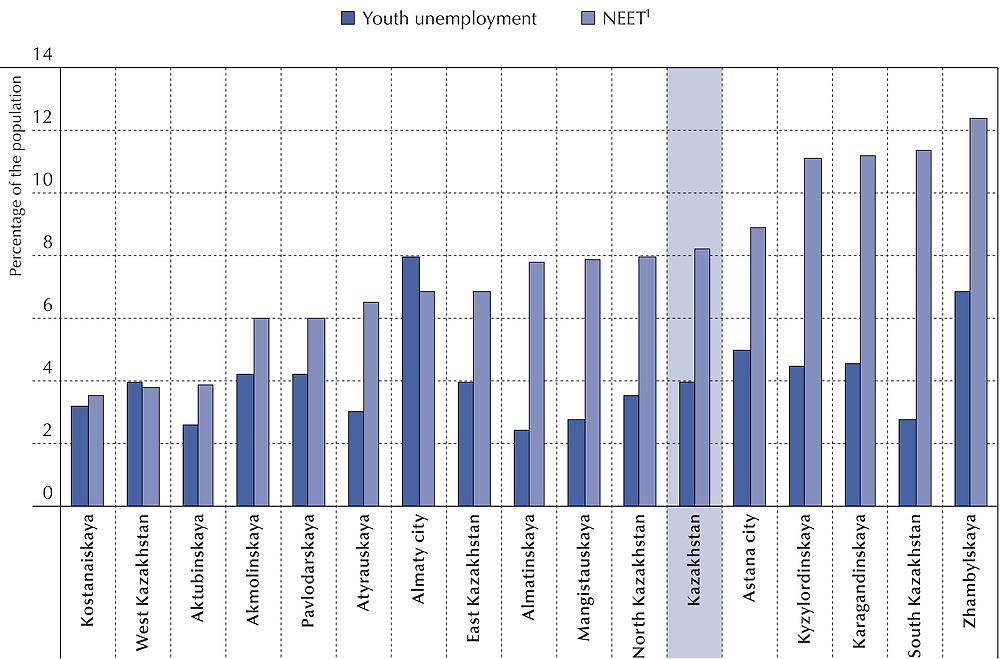

There are substantial regional differences in industrial growth and employment. For example, although the country enjoys relatively low overall levels of youth unemployment, the percentage of youth who are “Not in Employment, Education or Training” (NEET) varies significantly across regions (see Figure 1.3). Of particular concern are southern regions such as Kyzylorda, and South Kazakhstan (OECD, 2016a).

1. NEET= Neither employed nor in education and training

Sources: Ministry of National Economy of the Republic of Kazakhstan, Committee on Statistics (MNERK, 2014), www.stat.gov.kz.

Job quality also varies within Kazakhstan. The recent shift in employment from agriculture to services, and the growth of certain sectors such as education, has led to a decrease in self-employment. In 2001, salaried workers made up 58% of total employment; by 2013, this had increased to 69% (OECD, 2016a). However, just under half of the remaining self-employed are concentrated in the southern regions of South Kazakhstan, Zhambyl and Almaty (OECD, 2016a).

In 2013, approximately one-quarter of Kazakhstan’s workers were informally employed. This is comparable to the number in other countries with similar levels of development, and whose economy has a similar sectorial composition (OECD, 2016a). The large share of the young as part of Kazakhstan’s informal workforce suggests that informal employment may serve as an initial entry point into the labour market, or that it may be an employment opportunity of last resort.

Though labour productivity in Kazakhstan has increased steadily over the years, it is still low in comparison to more advanced countries. Certain sectors pose particular challenges. In the agriculture sector, for instance, the self-employment rate is extremely high (approximately 50%). For sustained growth, Kazakhstan must continue increasing the productivity of jobs in agriculture, while shifting employment from agriculture to other more productive sectors. Productivity has increased considerably in some sectors such as transport equipment manufacturing, and chemicals and pharmaceuticals (OECD, 2016a).

The diversity of Kazakhstan’s people and regions

Kazakhstan is a large and diverse country. It is divided into 14 provinces (oblasts) and two municipal districts, Almaty and the capital, Astana. With just nearly 10% of the country’s total population (1.5 million), Almaty, the largest city and the financial centre of the country, served as the capital for several years after independence.

Kazakhstan is a bilingual country with Kazakh designated as the “state” language and Russian as an “official” language. Roughly one out of every six people understands some English (CIA, 2016). Kazakhs account for approximately 63% of the population. There are many other ethnic groups in the country though. These include Russians, Uighurs, Ukrainians, Koreans, Uzbeks, Tatars, and Germans (CIA, 2016).

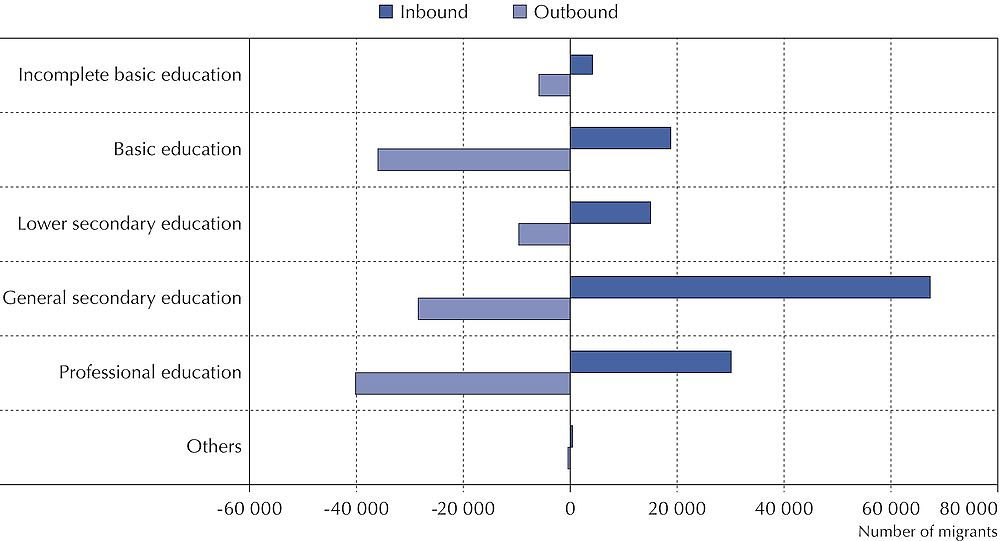

Migration flows are still significant in Kazakhstan. Emigration has been mostly directed towards the Russian Federation and other Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) countries, with the most popular non-CIS destinations being Germany, Israel, the United States and Canada. Immigration is primarily from the Russian Federation and other CIS countries. Kazakhstan’s migration pattern poses skills challenges, since approximately 25% of immigrants have less than a secondary education (see Figure 1.4). Meanwhile, a relatively large portion of those who leave the country have a professional education; this signals a potential brain drain. With immigrants largely concentrated in the south, migration flows create a bigger challenge for some regions than others (OECD, 2016a).

Sources: Economic Research Institute, Astana, in OECD (2016a), Multi-dimensional Review of Kazakhstan: Volume 1. Initial Assessment, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264246768-en.

Kazakhstan has a significant urban-rural divide, with incomes and consumption expenditures higher in urban areas. In 2013, urban poverty rates were one-fourth the rates in rural areas (OECD/The World Bank, 2015). The most urbanised regions are Karaganda (where 79% of the population is urban), Pavlodar (70%), Aktobe (62%) and East Kazakhstan (59%). The most rural regions are Almaty (where 77% of the population is rural), South Kazakhstan (61%), Zhambyl (60%), North Kazakhstan (58%) and Kyzylorda (57%).

From 1999 through 2009, the population declined in the regions of East Kazakhstan (-8.8%), Kostanay (-12.9%), Karaganda (-4.8%), West Kazakhstan (-2.9%), Akmola (-10.8%), Pavlodar (-8.0%) and, most dramatically, in North Kazakhstan (-17.8%). By way of contrast, other regions increased their population significantly during this period: Mangystau (+54.2%), South Kazakhstan (+24.8%), and the cities of Astana (+86.7%) and Almaty (+20.7%) (OECD and the World Bank, 2015).

Kazakhstan is implementing programmes to encourage labour flows across regions as a way of fostering more equitable growth and increasing overall productivity. For example, the “Serpin-2050” project aims to support the mobility of youth away from southern regions and some western regions where jobs are lacking. The state provides these youth with scholarships to study at higher education institutions in the regions that are experiencing labour and skills shortages (JSC Information-Analytic Center, 2015).

Beyond GDP: well-being in Kazakhstan

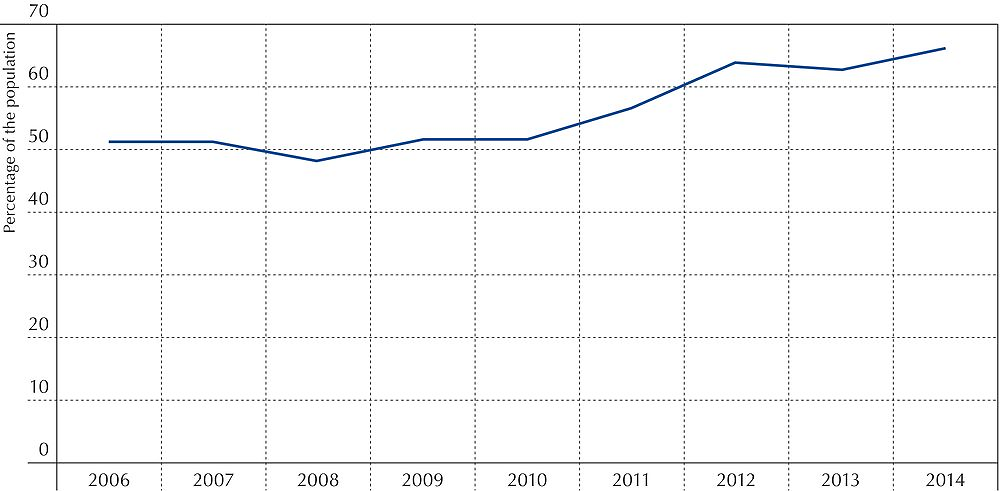

On balance, economic development has helped to improve the quality of the life of Kazakhstanis. Between 2000 and 2013, gross national income per capita (expressed in purchasing power parity terms) has more than doubled. Employment levels are high and, as depicted in Figure 1.5, two out of three Kazakhstani citizens report satisfaction with their living conditions (OECD, 2016a).

Sources: Gallup World Poll (database) in OECD (2016a), Multi-dimensional Review of Kazakhstan: Volume 1. Initial Assessment, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264246768-en.

While well-being indicators reflect substantial progress since 2000, many of Kazakhstan’s outcomes are below what one might expect in comparison to countries with similar levels of economic development. For example, life expectancy at birth has increased considerably, but still remains lower than the average for upper middle-income countries and for developing countries in Europe and Central Asia2 . Generally speaking, Kazakhstan performs better on the dimensions of well-being that are more closely associated with income (e.g. consumption possibilities, housing, infrastructure and life evaluation). On indicators where the correlation with income is weaker (e.g. environmental conditions, empowerment and vulnerability), Kazakhstan performs less well.

Although poverty rates increased dramatically in the 1990s, the economic growth of the 2000s subsequently lifted many out of poverty. Extreme or absolute poverty (defined as the state of those living below the international line of approximately USD 2 per day) has been virtually eliminated in Kazakhstan. The share of the country’s households with income below the national subsistence minimum has also decreased dramatically, falling from 46.7% in 2001 to 5.5% in 2011 and 2.8% in 2014 (Figure 1.6). Wage income – which doubled between 2003 and 2013 – has been the largest single contributor to poverty reduction over the past decade (OECD, 2016a).

Sources: Ministry of National Economy of the Republic of Kazakhstan, Committee on Statistics (MNERK, 2014), www.stat.gov.kz.

Gender inequality is comparatively low in Kazakhstan, although some challenges persist in the labour market. The labour force participation rate for men is 78%, while for women it is only 68% – a gap that is roughly consistent with the OECD average. Men outperform women in terms of income, but the gender pay gap (standing at less than 10%) is relatively low compared to some OECD countries. Access to primary and secondary education is near universal for both genders, but enrolment rates in tertiary education are higher for women (53%) than for men (37%) (OECD, 2016a). Kazakhstan has recently adopted several laws that prohibit discrimination based on gender.

Kazakhstan’s economic diversification challenge and the role of higher education

Emerging market economies have lost momentum as global growth prospects have failed to improve substantially. In recent years, these economies have found it harder to continue closing the income gap with more advanced economies (OECD, 2016a).

As noted above, Kazakhstan’s policy makers recognise that strong future economic growth requires reduced reliance on the natural resources sector and a move towards higher value-added activities and sectors. However, economic diversification policies have proven challenging to implement in Eurasian countries (Gill et al., 2014). Recent research suggests that these countries may best approach diversification by “try[ing] to create the conditions for accumulating a balanced portfolio of national assets, exploiting natural resources responsibly, building infrastructure and human capital, and instituting mechanisms that manage resource rents, provide public services and regulate private enterprise” (Gill et al., 2014).

This review focuses on higher education in Kazakhstan and its potential to support the diversification of the country’s economy, both through the development of a broad and advanced skills mix, and through the creation and application of knowledge.

Governance, infrastructure, regulation and the rule of law are all important areas where Kazakhstan needs to keep making progress if its economy is to successfully diversify, seize on the potential of promising sectors such as ICT and other forms of advanced manufacturing, and enjoy sustainable long-term growth. Just as important for growth, though, are the skills and knowledge resources of Kazakhstanis, and the nation’s capacity for research and innovation (World Bank, 2015).

To build on recent economic progress, Kazakhstan needs a well-functioning innovation system that supports productivity growth and helps develop a broad, sustainable mix of economic activity that has significant strengths in high value-added economic activities. Such activities tend to be technology- and knowledge-intensive and require smart investment in research and development (R&D) and innovation.

To ensure continued growth in prosperity, Kazakhstan will also need to ensure that its population builds and reinforces a mix of skills and knowledge that:

-

meets the needs of the current economy

-

allows the country to seize on – and indeed, shape – the opportunities and challenges of a future economy whose outlines are still uncertain.

Human capital is a vital component of economic growth. It is a key source of innovation and productivity that enables the transfer of wealth across generations, and brings together the other factors of production in ways that drive prosperity. The pace of human capital’s growth depends on the quantity and quality of education provided to each individual, and provided to all individuals collectively, over entire lifespans. It also depends on other factors such as the quality of health care and the broader social environment (Gill et al., 2014). A social system where corruption is widespread, for instance, will lower individuals’ incentive for investing in knowledge and skills – and perhaps also limit their ability to make such investments.

Policy makers across the world face the challenge of ensuring that their citizens and residents develop the skills they need for success. The OECD defines skills as “the bundle of knowledge, attributes, and capacities that enable individuals to successfully and consistently perform an activity or task, and that can be built up and extended through learning” (OECD, 2012c). In broad terms, there are three sets of skills and knowledge that are critical for economic growth and social well-being. Higher education, just like the other parts of the skills and knowledge system, plays an important role in developing each of these.

Good technical, professional and discipline-specific knowledge and skills reflect a solid theoretical and/or practical understanding of subject matter; at the higher education level this subject matter is typically codified by academic disciplines. These kinds of skills are not developed solely to meet labour market ends. Employers often use these credentials – which will vary widely of course in different contexts – as a first lens to screen individuals for jobs. In fact, for many jobs a given level of a concrete set of technical and professional skills is an essential requirement (e.g. in Kazakhstan’s current natural resources sector). At the level of the overall labour market, an adequate supply and mix of these skills is an important precondition for economic growth.

Generic cognitive skills include for example literacy, numeracy, problem solving, critical thinking and digital competencies. They support individuals’ ability to acquire knowledge, thoughts and experience – and to interpret, reflect and extrapolate based on knowledge that they have acquired (OECD, 2015a).

Generic cognitive skills are needed to perform a wide range of tasks. They also support adaptability in the face of a changing economy – in part because they enable further learning. These skills also support workplace productivity by allowing individuals to effectively deal with non-routine challenges.

Social and emotional skills encompass skills like initiative, teamwork and leadership. They are manifested in consistent patterns of thoughts, feelings and behaviours, and play an important part in achieving goals, working with others and managing emotions. Like other kinds of skills, they can be developed through both formal and informal learning experiences (OECD, 2015c).

Good levels and mixes of these various skills, combined with a sound innovation system, are critical if countries are to support growth and seize on the potential of new production technologies.

Kazakhstan’s social challenges, and its need to diversify its economy in ways that ensure sustainable long-term growth, have substantial implications for the country’s innovation system and its skills needs. The remainder of this chapter will look at skills outcomes in Kazakhstan today, after first situating higher education within Kazakhstan’s broader education landscape.

Kazakhstan’s education and training systems

Kazakhstan’s level of educational attainment is comparatively high, approaching average levels of OECD countries. Of the adult population aged 25 and above, approximately 40% have upper secondary education as their highest level of attainment, 30% have a post-secondary degree and 25% have completed higher education.

Main institutions and underlying principles

Kazakhstan’s central government plays a very important role in the country’s education and training system:

-

The Executive Office of the President defines key education strategies and develops major initiatives such as the network of Nazarbayev Intellectual Schools that cater to gifted students. The Office also monitors progress towards the objectives that are laid out in education strategies.

-

The Ministry of Education and Science of the Republic of Kazakhstan (MESRK) manages, implements and monitors work in education, science, protection of children’s rights and youth policy. The MESRK is mandated to: define and execute educational policy; draft regulations with regards to funding education; prepare educational standards and curricula; organise and implement assessment systems; set requirements for teacher education; support the educational process in Kazakh language; and sign international agreements on education.

-

The MESRK has several subordinate organisations that operate in specific areas (e.g. quality assurance, statistics or managing international projects). For instance, the Information Analytic Center provides analytical support the MESRK and is responsible for a variety of things, such as the Ministry’s international projects (including reviews of the education system like this one). The National Center for Professional Development (ORLEU) provides a second example. It is responsible for the design and provision of professional development opportunities for teachers and school leaders.

-

The MESRK reports to the Executive Office of the President, is assessed by the Ministry of National Economy of the Republic of Kazakhstan (MNERK) for performance, and is monitored by the Ministry of Finance on the execution of its budget.

The underlying principles of Kazakhstan’s education system are defined by the Constitution of the Republic of Kazakhstan (1995) and the Law on Education (2007). Among its main provisions, the Law on Education (2007) determines the objectives and principles of education, outlines the educational administrative structure and stipulates different administrative and financial aspects of education institutions’ operations.

Funding

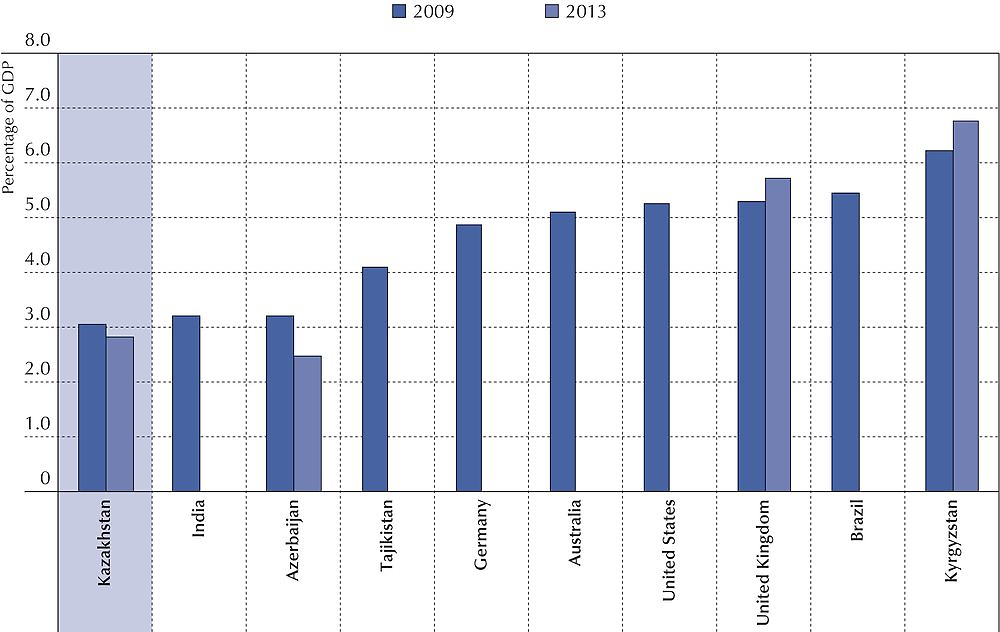

As Kazakhstan’s overall economy has expanded in recent years, nominal public spending on education has also increased (JSC Information-Analytic Center (2015). However, growth in spending as a percentage of GDP has been modest over the past ten years, and indeed fell from 3.1% of GDP in 2009 to 2.9% in 2014 (UNESCO, 2016) (Figure 1.7). This puts Kazakhstan below the 4-6% international benchmarks for public expenditure on education (Figure 1.7).

Notes: Data for the years 2001, 2003, 2010, 2011 and 2012 are not available for Kazakhstan.

Sources: UNESCO Institute for Statistics (UIS) database, http://data.uis.unesco.org (accessed on 18 May 2016).

Notes: Some countries did not have data available in 2013 (Australia, Brazil, Germany, India, Tajikistan, the United States).

Sources: UNESCO Institute for Statistics (UIS) database, http://data.uis.unesco.org (accessed on 18 May 2016).

Kazakhstan’s reported public investment in higher education is also low by international standards, with the government spending only about 0.3% of GDP on higher education. Higher education accounts for 8.6% of the total state budget for education (Nazarbayev University Graduate School of Education, 2014).

In 2014, approximately 70% of Kazakhstan’s total expenditure on higher education came from private rather than public sources (MNERK, 2014) – primarily from tuition fees (see Chapters 3 and 6). By way of comparison, across all OECD countries in 2012, 69% of expenditures on tertiary education came from public sources and 31% from private sources (OECD, 2015b). Thus, low public spending on education in Kazakhstan is partially offset by a heavy reliance on private spending. This private/public balance has equity implications that Chapter 3 will explore in more detail.

Policy priorities

Kazakhstan has formulated the goal of improving the quality of its education system, with international standards and practices serving as key points of reference. Building on the State Programme for Education Development in the Republic of Kazakhstan 2011-2020 (SPED), the updated State Programme for Education and Science Development 2016-2019 (SPESD) for 2016-19 lays out the current strategy for the education sector. The SPED identifies priorities, targets, and indicators to be achieved by 2020 from preschool to higher education.

At the level of primary and secondary education, key policy objectives include: developing new mechanisms of education financing such as per capita financing; providing education staff with more preparation, support and incentives; improving student assessment methods; transitioning to a 12-year education model; updating curricula; and developing inclusive education with supports for low-performing students.

At the higher education level, the primary objectives of the SPED include: equipping students with skills more relevant to the labour market; integrating Kazakhstan more fully into the European Higher Education Area; bolstering synergies between education, science and industry; stimulating the commercialisation of research; fostering national identity; and encouraging active citizenship and social responsibility.

Primary and secondary education

In Kazakhstan, primary education is compulsory and spans the first four years of schooling. Children typically enrol at age seven, but six-year-olds can be admitted through an entrance exam. Secondary education has two levels: the basic lower level covers grades 5 through 9 and the general or vocational upper secondary level covers grades 10-11. A small minority of schools also have a grade 12 (e.g. the Nazarbayev Intellectual Schools) (see Annex I.A1).

The net enrolment rate for primary and lower secondary education (ages 5-14) is 99%, and for upper secondary education (ages 15-19) it stands at 86%. The enrolment rates of boys and girls are similar to each other. The most gifted students can attend the Nazarbayev Intellectual Schools: 0.4% of the total general secondary student population is enrolled at these special schools, which receive much more funding than mainstream schools (OECD and the World Bank, 2015).

Upon completion of the upper secondary level, students can enter technical vocational schools (colleges) or higher education institutions.

Technical and vocational education

Students can choose to enter vocational education and training (VET) institutions at upper secondary level (currently after 9th grade) or after upper secondary schooling (currently after 11th grade) (OECD, 2013a).

Since 2012, both kinds of institutions are referred to as “colleges”. In 2013, Kazakhstan had a total of 888 VET institutions and the enrolment rate in 2015 was 16.1%. There has been a decrease over the past years in the number of students enrolling in VET, although the government recently announced measures to encourage enrolment through a free tuition scheme. There are also concerns about poor co-ordination and interaction between VET schools and employers, and about poor quality assessment and certification processes (Álvarez-Galván, 2014).

Higher education

In 2015, Kazakhstan had a total of 125 higher education institutions3 . This represents a significant decline from the more than 180 institutions that were operating in 2000. Like many post-Soviet economies, Kazakhstan saw rapid growth in the number of private providers in the 1990s in response to high student demand. Over the past several years, Kazakhstan has been seeking to reduce this number (a process, known as “optimisation”, which has led to mergers and sometimes closure of institutions).

In 2015, Kazakhstan’s network of higher education institutions included 64 private institutions (including 10 joint-stock companies or “JSCs”4 ) and 61 public institutions. Of these institutions, 85 operate as universities, 21 as academies, 18 as institutes and one as a conservatory. These distinctions are made as part of institutional licensing procedures, and are based on a variety of factors including the number of graduate programmes, the institution’s research profile, and its certifications and accreditations. There is one autonomous university in Kazakhstan: President Nazarbayev established Nazarbayev University in 2010, directing it to become a world-class university with a strong research programme (JSC Information-Analytic Center, 2015).

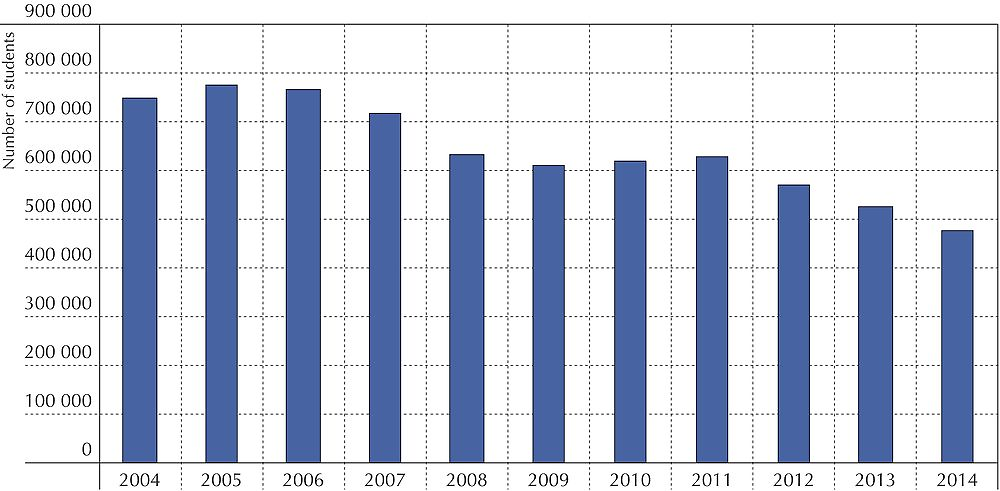

Kazakhstan’s higher education enrolment rate5 currently stands at approximately 48%. However, over the past ten years, the absolute number of students entering higher education (including post-secondary technical and vocational education) has declined by 36% (Figure 1.8). In 2014, 477 387 students were enrolled in higher education – a decline of nearly 50 000 from 2013 levels. Falling student numbers over time are linked to the low fertility rates that characterised Kazakhstan’s transition period post-independence and to falling enrolment in part-time education.

Sources: Ministry of Education and Science of the Republic of Kazakhstan (MESRK), statistics (2004-2014).

The role of research in Kazakhstan’s higher education system has evolved considerably in recent years. In the immediate post-Soviet period, much of the country’s research activity remained concentrated in institutes that operated under the Academy of Sciences. Over time, however, many research institutes have been merged or aligned with universities, while others have been newly created within universities. These changes, which are still underway, are meant to better integrate science and education.

Though most universities still report some level of research activity, the Law on Science in 2011 and the State Programme of Education Development for 2011-2020 introduced two new designations for selected higher education institutions –“research university” and “national research university”. These institutions enjoy access to enhanced funding for research and they are expected to integrate teaching, learning and research at all levels of study.

Skills outcomes in Kazakhstan

There are few measures of the current skills outcomes of Kazakhstan’s education and training systems, and of how well these systems are positioned to meet the needs of the labour market. This data gap is broadly consistent with other data challenges that the OECD review team observed in Kazakhstan – and has serious negative consequences for policy making. Much of the evidence on skills outcomes that does exist is not encouraging.

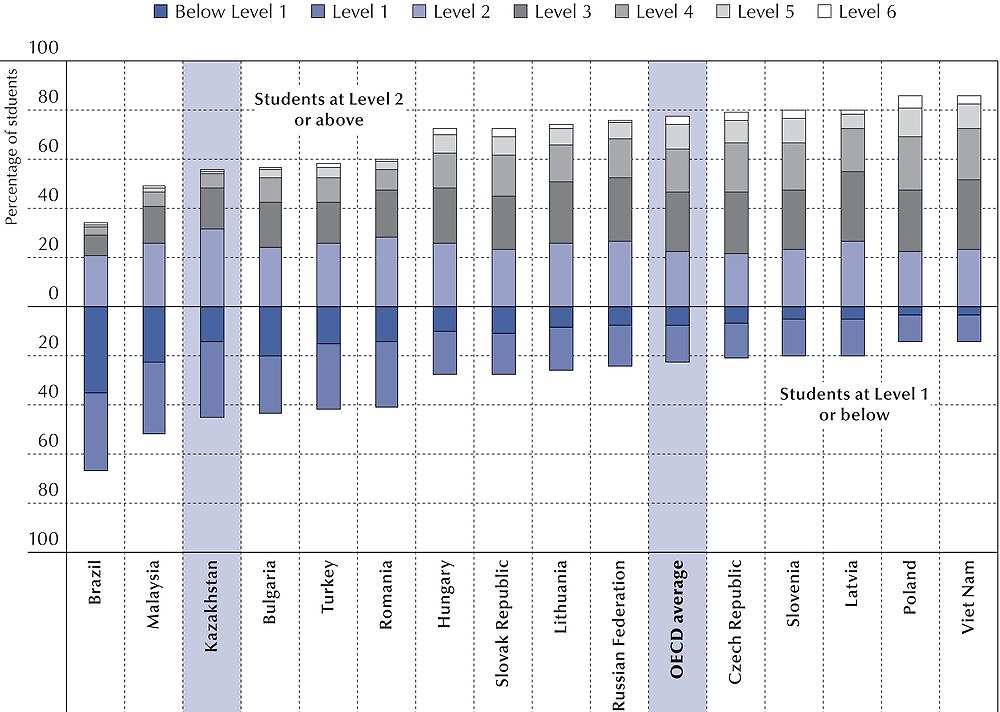

While basic education is quasi-universal, international comparisons such as the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) suggest that the average quality of schooling is low. In PISA 2012, the performance of 15-year-olds in Kazakhstan rose compared to 2009 levels, and showed a narrowing achievement gap among students (OECD, 2013b). Math and science performance improvements equivalent to more than half a year of schooling were registered (OECD, 2014). Despite this apparent improvement, countries with income per capita levels similar to Kazakhstan’s (e.g. Turkey and the Russian Federation) still performed significantly better in mathematics, science and reading. Furthermore, Kazakhstani PISA reading scores continue to lag (by the equivalent of about one year of schooling) behind the Europe and Central Asia average, and by almost two years of schooling behind the OECD average. The percentage of low performers (45%) is significantly above the OECD average (23%) (see Figure 1.9). Those students can extract relevant information from a single source and use basic algorithms, formulae, procedures or conventions to solve problems involving whole numbers. Whereas top performers, who represent 0.9% of the population, have more problem-solving skills that are more developed when working with mathematics models – they use their thinking and reasoning skills. This percentage is much smaller than on average across OECD countries (13%). School location, the language of instruction, the socio-economic background of students and schools make a difference in student performance. The quality of school educational resources registers at one of the lowest levels among PISA countries (OECD, 2013b). Other national and international assessments also suggest that students from urban areas have better educational outcomes than students in rural areas.

Sources: OECD (2014), PISA 2012 Results: What Students Know and Can Do (Volume I, Revised edition, February 2014): Student Performance in Mathematics, Reading and Science, PISA, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264208780-en.

Kazakhstan has national tests of graduating secondary school and higher education students. However, these tests are of questionable validity and fail to measure many of the most important skills that workers and citizens need in a modern society, such as problem-solving skills, creativity and independent-thinking skills. There is little systematic follow-up of graduates, but employers in Kazakhstan do report gaps in employees’ skills (World Bank, 2013a and b). Following the “shock” of the country’s poor performance in PISA 2012, the government focused on high-ability students. Kazakhstan’s policy has concentrated on recognising and encouraging academically talented students, with little attention paid to ensuring equity. Chapter 2 of this report examines these issues in more detail.

More generally, despite the significant reforms that Kazakhstan has undertaken in recent years to improve the quality of its primary and secondary education systems, there remains substantial room to improve the overall effectiveness of the education system and enhance learning outcomes (OECD and the World Bank, 2015). Potential areas of intervention include reviewing the organisation of the school network, lengthening the school day, supporting disadvantaged students and schools, and improving teacher quality and school leadership (see also Chapter 3 of this review). However, these initiatives will only succeed if evaluation and information systems are used to foster improvement and accountability (OECD and the World Bank, 2015).

References

Álvarez-Galván, J.-L. (2014), A Skills beyond School Review of Kazakhstan, OECD Reviews of Vocational Education and Training, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264221826-en.

Central Intelligence Agency (2016), The World Factbook: Kazakhstan, www.cia.gov/library/publications/resources/the-world-factbook/geos/kz.html.

Gill, I.S., I. Izvorski, W. van Eeghen and D. De Rosa (2014), Diversified Development: Making the Most of Natural Resources in Eurasia, World Bank, Washington DC, documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/124481468251373591/Diversified-development-making-the-most-of-natural-resources-in-Eurasia, License: Creative Commons Attribution, CC BY 3.0.

JSC Information-Analytic Center (2015), “Country Background Report”, prepared for the OECD follow-up review of higher education policy in Kazakhstan, JSC Information-Analytic Center, Ministry of Education and Science of the Republic of Kazakhstan, Astana.

International Monetary Fund (2016), International Financial Statistics; Intelligence Economist Unit, http://data.imf.org/?sk=388DFA60-1D26-4ADE-B505-A05A558D9A42.

Law on Education (2007), Law on Education of the Republic of Kazakhstan, of 27 July 2007, No.319 –III ZRK, About education, last edition of 09 April 2016.

MESRK (2016), The State Programme for Education and Science Development in the Republic of Kazakhstan 2016-19, RK Presidential decree as of 1 March, 2016.

MNERK (2014), Ministry of National Economy of the Republic of Kazakhstan, Committee on Statistics, http://kyzylorda.stat.gov.kz/eng/ (accessed 25 February and 04 March 2016).

MESRK (2010), The State Program for Education Development in the Republic of Kazakhstan 2011-2020, RK Presidential decree as of 7 December, 2010, Number 1118.

MESRK (2004-2014), Ministry of Education and Science of the Republic of Kazakhstan, Statistics, http://edu.gov.kz.

Nazarbayev, N.A. (2012), Address by the President of the Republic of Kazakhstan, Leader of the Nation, N.A. Nazarbayev: “Strategy Kazakhstan-2050”: New political course of the established state, www.inform.kz/en/address-by-the-president-of-the-republic-of-kazakhstan-leader-of-the-nation-n-nazarbayev-strategy-kazakhstan-2050-new-political-course-of-the-established-state_a2346141.

Nazarbayev University Graduate School of Education (2014), Development of Strategic Directions for Education Reforms in Kazakhstan for 2015-2020, Diagnostic Report, Indigo Print, Astana.

OECD (2016a), Multi-dimensional Review of Kazakhstan: Volume 1. Initial Assessment, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264246768-en.

OECD (2015a), Skills for Social Progress: The Power of Social and Emotional Skills, OECD Skills Studies, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264226159-en.

OECD (2015b), Education at a Glance 2015: OECD Indicators, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/eag-2015-en.

OECD (2014), PISA 2012 Results: What Students Know and Can Do: Student Performance in Mathematics, Reading and Science, (Volume I, Revised edition, February 2014) PISA, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264208780-en.

OECD (2013a), Developing Skills in Central Asia Through Better Vocational Education and Training Systems, Private Sector Development Policy Handbook, OECD Publishing, Paris, www.oecd.org/globalrelations/VocationalEducation.pdf.

OECD (2013b), PISA 2012 Results: What Makes Schools Successful (Volume IV): Resources, Policies and Practices, PISA, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264201156-en.

OECD (2012), Better Skills, Better Jobs, Better Lives: A Strategic Approach to Skills Policies, OECD Publishing, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264177338-en.

OECD/The World Bank (2015), OECD Reviews of School Resources: Kazakhstan 2015, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264245891-en.

OECD/The World Bank (2007), Reviews of National Policies for Education: Higher Education in Kazakhstan 2007, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264033177-en.

The Economist (2016), “Economic Intelligence Unit Report on Kazakhstan”, The Economist, http://country.eiu.com/kazakhstan (accessed 24 February 2016).

UNESCO Institute for Statistics (UIS) database, http://data.uis.unesco.org, (accessed 18 May 2016).

World Bank Group (2016), “Ease of doing business in Kazakhstan (ranking data for 2014 and 2015)”, Doing Business, www.doingbusiness.org/data/exploreeconomies/kazakhstan (accessed 15 February 2016).

World Bank (2015), “Kazakhstan - Low Oil Prices, an Opportunity to Reform”, Economic Update Spring 2015, World Bank, www.worldbank.org/en/country/kazakhstan/publication/kazakhstan-economic-update-spring-2015 (accessed on 5 February 2016).

World Bank (2014), World Development Indicators (database), http://data.worldbank.org.

World Bank (2013a), Kazakhstan Country Economic Memorandum: Beyond Oil: Kazakhstan’s path to greater prosperity through diversifying, Report No. 78206 Volume 1: overview, June 2013 Poverty Reduction and Economic Management Unit, Europe and Central Asia Region.

World Bank (2013b), www.worldbank.org/en/results/2014/10/15/in-kazakhstan-better-training-for-a-better-economy (accessed 12 April 2016).

Notes

← 1. The statistical data for Israel are supplied by and under the responsibility of the relevant Israeli authorities. The use of such data by the OECD is without prejudice to the status of the Golan Heights, East Jerusalem and Israeli settlements in the West Bank under the terms of international law.

← 2. Developing countries in Europe and Central Asia include: Albania, Armenia, Belarus, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, the Kyrgyz Republic, Azerbaijan, Croatia, Georgia, Kazakhstan, the Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia, Republic of Moldova, Montenegro, Poland, Romania, the Russian Federation, Serbia, Tajikistan, Turkey, Turkmenistan, Ukraine, and Uzbekistan.

← 3. A total of 126 including Nazarbayev University.

← 4. JSCs are legally registered entities that issue stock in order to attract funding for their operations. JSC shareholders can be of different kinds. In case of JSCs that are linked to the MESRK, the main shareholder is usually the ministry or government itself. JSCs are for-profit organisations, but non-profit units can be established within them.

← 5. Gross enrolment rates in higher education are defined as the ratio of the number of students, (regardless of age) to the total population in the typical enrolment age range (e.g. 18-22 in many countries).