Chapter 17. Big Potential: An investment readiness programme, United Kingdom

The Big Potential programme provides grants for investment readiness support, and raises awareness of investment approaches for voluntary, community and social enterprises in England. This chapter describes the programme’s objectives, rationale and activities, the challenges faced in implementing the scheme, and the impact achieved. It includes lessons learnt and conditions for transferring this practice to another context.

Summary

Big Potential is a three-year, EUR 23.8 million1 (GBP 20 million) grant fund programme (2014-17) helping voluntary, community and social enterprises (VCSEs) in England take on repayable investment to increase their social impact. It is funded by the Big Lottery Fund and delivered by a partnership led by the Social Investment Business (SIB).

The grant programme has two strands, “Breakthrough” and “Advanced”, based on the recipient’s level of investment-readiness and the desired investment amount. The Breakthrough strand funds specialist help for VCSEs embarking on the first stages of social investment so that they can undertake in-depth investment readiness work. The Advanced strand supports organisations that are further along on the social investment journey and are seeking investments totalling over EUR 595 000 (GBP 500 000).

The programme is currently a bit more than midway through its lifespan and is still awaiting full evaluation. Nevertheless, some of its innovative features could clearly be replicated in other countries. Key features for replication include: undertaking prior research on the needs of the organisations requiring support; hiring a grant manager with sufficient expertise and capacity to manage the programme; engaging in good outreach and collaboration with social enterprise networks; developing a robust support provider base; undertaking ongoing evaluation; broadening the objective to include sustainability issues for VCSEs; and tailoring the programme to the different needs of social enterprises and more traditional charities.

Key facts

Big Potential is a three-year programme ending in December 2017. The launch of the Big Potential Breakthrough fund in 2014 provided initial funding of EUR 11.9 million (GBP 10 million). In September 2015, the establishment of the Big Potential Advanced fund added a further EUR 11.9 million (GBP 10 million) in funding.

Big Potential aims to provide around 320 grants to VCSEs located in England. Separate policies and programmes support VSCEs in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland. Big Potential is funded by the Big Lottery Fund, a quasi-public body accountable to the United Kingdom (UK) government, which distributes annually EUR 773.5 million (GBP 650 million) – 40% of the money raised for good causes by the UK National Lottery. Big Potential receives no European Union (EU) funding.

Big Potential is managed by SIB, a non-profit organisation that provides loans, grants and other financial products to charities and social enterprises, in partnership with four other organisations: Charity Bank (a UK-wide specialist finance provider), Locality (a network of local asset-based community organisations), Social Enterprise UK (a representative body for social enterprises) and the University of Northampton (acting as an evaluator). The grants are paid into the VCSEs, which then enter into contractual relationships with accredited support providers to help them get ready for investment.

As of March 2016, Big Potential had approved 128 Breakthrough grants (out of 246 applications received) and 23 Advanced grants (out of 58 applications received). Big Potential has gathered and accredited 39 Breakthrough and 24 Advanced support providers. As of June 2015, the Breakthrough programme had yielded four successful investments in VCSEs, raising a total EUR 1.2 million in finance.

Objectives

Big Potential targets VCSEs in England. Its policy approach is to provide grants funding work by approved providers to help VCSEs ready themselves for investment or win public contracts. Beneficiary organisations and approved providers are selected on the basis of a diagnostic screening process. In addition to supporting the organisations participating in the programme, Big Potential has the wider objective of raising awareness of investment approaches for VCSEs. It shares learning through a three-year programme of 17 workshop events across different geographical areas of England, as well as a number of additional customised events according to demand.

The programme also aims to create an online marketplace of investment readiness support providers, who are accessible to anyone (not only grant applicants) through the Big Potential website.2 The goal is to increase these organisations’ visibility and co-ordination, as well as reach a greater audience and have an impact beyond its grant recipients.

Organisations eligible for support broadly match the European Commission-SBI concept of a social enterprise. An applicant to Big Potential must be “a non-governmental body that principally reinvests its surpluses for social or environmental purposes”; this includes registered charities, social enterprises, companies limited by guarantee with charitable aims, community interest companies and mutuals (H.M. Government, 2011a).3

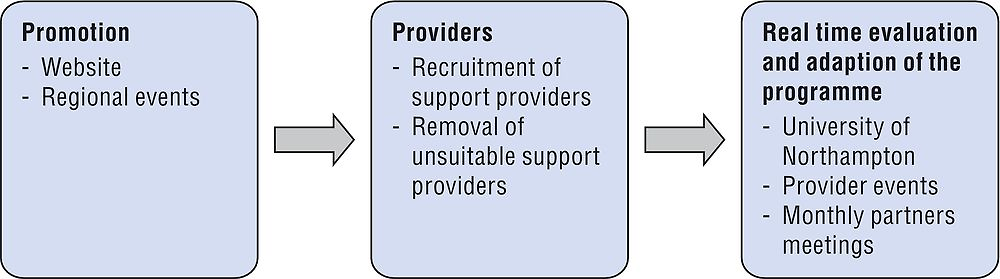

To draw out learning from the process of running the fund, Northampton University is undertaking formal evaluations of both strands while the programme is still running, so that issues can be addressed and improvements made during the course of the programme. The University will continue to monitor the impact on grantees for another two years after the programme ends.

Rationale

The United Kingdom has a long tradition, dating back to the 19th century, of nurturing various social enterprise business models. The UK ecosystem is well-developed: for almost 20 years, successive governments have developed policies to support social enterprises’ growth, including by facilitating access to investment (Bland, 2010).

In 2011, the previous UK coalition government published a vision document, Growing the Social Investment Market, A Vision and Strategy (H.M. Government, 2011b), which advocated increasing social investment supply and demand. The government launched a number of initiatives, including a EUR 35.7 million (GBP 30 million) social investment pilot programme incorporating three funds: the Impact Readiness Fund, the Investment and Contract Readiness Fund (ICRF) and the Social Incubator Fund. These funds provided grants to help VCSEs seeking investment and public service contracts become investment-ready and demonstrate their impact. The learning from this pilot programme informed the development of the Big Potential programme.

The Big Lottery Fund has a remit to support charities, community organisations and social enterprises through a number of thematic grant programmes. In 2010, the Fund began to provide direct funding to social investment initiatives. In 2012, it published a research report on investment readiness in the United Kingdom setting the policy rationale for creating Big Potential as part of its social-investment strategy (Gregory et al., 2012). The report identified a number of barriers to VCSE investment readiness, including:

-

a lack of suitable financial skills

-

a general lack of understanding of the concept and appropriateness of social investment

-

the absence of filtering systems, leading organisations to approach investors too early

-

poor signposting4 and co-ordination of organisations providing advice and support

-

the complexity of deals relative to the amount of finance involved.

The Fund used the results of this research to shape its social investment strategy for VCSEs and the Big Potential programme – especially with regard to developing a co-ordinated marketplace of suppliers offering support services.

Activities

SIB answers to the Big Lottery Fund and is the principal manager of the programme. Working with its four partners, it promotes Big Potential through a dedicated website and regional events, selects grant recipients, creates and maintains a marketplace of accredited support providers, disburses funds and monitors the programme. Big Potential is divided into two strands: Breakthrough and Advanced.

Breakthrough

The EUR 11.9 million (GBP 10 million) Breakthrough fund provides grants ranging from EUR 23 800 to EUR 89 250 (GBP 20 000-75 000) to VCSEs seeking to raise up to EUR 595 000 (GBP 500 000). Organisations in earlier stages of their investment journey can apply for preliminary grants ranging from EUR 23 800 to EUR 35 700 (GBP 20 000-30 000) to help determine what kind of investment will meet their needs, or for investment plan grants ranging from EUR 47 600 to EUR 59 500 (GBP 40 000-50 000) if they already have a detailed investment proposition. No single organisation can receive more that EUR 89 250 (GBP 75 000).

The Breakthrough programme provided 30 grants in its first year and 93 in its second year; it aims to provide a total of around 200 grants by the end of the programme.

Advanced

The EUR 11.9 million (GBP 10 million) Advanced fund provides grants ranging from EUR 59 500 to EUR 178 500 (GBP 50 000–150 000) to VCSEs seeking to raise more than EUR 595 000 (GBP 500 000). Applicants must have a clear understanding of social investment’s potential benefits to them. They must already have a potential deal or interest from investors, and need help closing that deal. The Advanced fund is also available to organisations needing help to secure a contract over EUR 1.19 million (GBP 1 million).

The Advanced programme had provided 12 grants by March 2016; it aims to make around 120 grants by 2017.

Applicants for both funds go through the following steps (Figure 17.1.):

-

Online registration: the applicant submits basic information about the organisation.

-

Online diagnostic tool: the applicant provides further information, including detailed information about the organisation’s business model (i.e. the business sector, legal structure, financial data, income streams, governance, staffing, skill sets, product/service offer, accounting practices and investment needs).

-

Advisor session: a face-to-face interview (normally through a video call) is conducted to review the diagnostic results and discuss the business model.

-

Provider selection: the applicant selects a support provider from an approved list; they then work in partnership to co-develop the grant application.

-

The applicant submits the grant request.

-

Assessment: an external panel of experts (one for each fund) decides whether to approve or reject the application.

-

Implementation: if successful, the VCSE works with the support provider to develop the organisation’s investment-readiness and secure investment.

The process aims to be developmental; unsuccessful applicants may be invited to reapply.

Relying on the recommendations of a panel of experts, SIB rigorously selects for each of the programmes the providers who will advise the VCSEs on specific topics related to social investment. The providers must offer a competitive daily rate to allow comparing costs. All daily rates are capped at EUR 1 190 (GBP 1 000), including value added tax; SIB may intervene if rates are significantly higher than average for comparable services.

Using a matching process, the VCSE chooses the provider that will help it prepare a proposal and (if successful) deliver the project. Details on application success rates are posted on the Big Potential website.

Big Potential covers 100% of the costs incurred by Breakthrough applicants; Advanced applicants are expected to contribute about one-third of costs of the provider’s work. Big Potential provides the funds directly to the VCSE, which must then agree on payment terms directly with the provider. The provider takes on the role of prime contactor and is responsible for sourcing additional support in the event that the organisation requires assistance it cannot provide.

Provider support to the VCSEs includes:

-

business planning to develop and scale services

-

strengthening financial modelling

-

establishing reporting and controls

-

improving impact measurement

-

working with people to plan and structure deals

-

strengthening managerial and financial capabilities

-

improving governance and partnership work

-

undertaking market research and collecting evidence to support product development

-

developing products and services that will bring in trading income

-

networking with appropriate stakeholders (including investors)

-

developing and creating vehicles for social investment

-

hiring talent with the appropriate skills

-

improving sales and marketing plans.

The provider and the VCSE jointly manage and monitor the project, and must submit quarterly monitoring reports and a final closing report to SIB.

VCSEs provide feedback on providers; any provider giving a consistently poor level of service is removed from the list. New providers are invited to apply through the website and are regularly considered by the expert panels.

Every six months, providers are invited to dedicated events to share their experience, feedback and learning with SIB staff, thereby supporting the programme’s continuous improvement.

In addition to issuing reports on both of its strands, Big Potential is creating a dataset of 1 500 to 2 000 VCSEs to inform investors and better match projects with funding. The Big Lottery Fund has committed to making these “open data” publicly available at the end of the programme.

Big Potential was initially limited to the EUR 11.9 million (GBP 10 million) Breakthrough fund. Following the successful piloting of the Cabinet Office’s ICRF, also managed by SIB, the evidence suggested that supporting VCSEs requiring over EUR 595 000 (GBP 500 000) in investment was still essential, and that the basic delivery mechanisms had been successful (Ronicle and Fox, 2015). The evidence also suggested that the ICRF element relative to helping organisations achieve contract readiness had worked well. Big Potential was therefore expanded in 2015 to include both a further EUR 11.9 million (GBP 10 million) in funding for the Advanced programme and contract-readiness support.

Challenges encountered and impact

Table 17.1. presents a strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats (SWOT) analysis of Big Potential.

Even though Big Potential is more than midway through its term, it is still too early to fully assess its success/impact or draw proper conclusions about what could be done differently. However, an evaluation of the first few months of the Breakthrough programme was conducted and published in 2015. The evaluation’s key findings are as follows (Hazenberg, 2015):

VCSE engagement has been largely successful: as of January 2015, nearly 13 500 visitors had engaged with the Big Potential website; 3 898 VCSEs had registered on the site; 1 415 were deemed eligible to apply for grants; 283 organisations had completed the online diagnostic tool; and 162 had participated in one-on-one advisor sessions. Out of the 71 grant applications, 32 had been successful, totalling EUR 1.19 million (GBP 1 million) and averaging EUR 37 185 (GBP 31 248) each; most projects were locally based and small in scale, with an average turnover of around EUR 357 000 (GBP 300 000). By January 2015, no investment had been secured as a result of the work carried out.

The online diagnostic tool and one-on-one support sessions worked well. The panel and grant decision-making phase were also effective, although rejected applicants expressed a desire for more feedback and streamlining the process to facilitate resubmitting applications when the panel only recommended minor improvements.

Provider selection was crucial to success, operating best when providers worked closely with the VSCEs on their applications. Many of the VCSEs that had received an investment readiness grant had already benefitted from in-depth collaboration with the providers, analysing their strengths and weaknesses, and identifying they types of social investment they wished to pursue.

The main reasons grant applications were rejected pertained to poor market analysis, a lack of financial data and organisations applying too early in their development.

Despite these positive results overall, the evidence showed that more needed to be done to engage certain types of VCSEs (e.g. those led by disabled people and women; some English regions were also under-represented). In addition to addressing these issues, the report (Hazenberg, 2015) recommended a number of minor improvements: aligning support providers with the programme’s objective of acting as a developmental process for VSCEs; improving information on the website; providing more information to help VCSEs select a provider; establishing a more robust means for VCSEs to evaluate the providers; and improving feedback on rejected applications. It also suggested that providers work more closely with VCSEs on their approaches to social-impact measurement “to ensure that VCSEs incorporate formalised and externally validated measures of social impact measurement” (Hazenberg, 2015).

Finally, to shape the programme’s ongoing evaluation, Hazenberg (2015) recommended drawing up case studies and conducting future research on VCSE progression, provider selection and performance, barriers to women and disabled people, and investment-panel decisions on rejected applications.

In addition to this evaluation, an emerging theme from comments made by The Big Lottery Fund, SIB and Northampton University5 is that the programme enhances the sustainability of VSCEs (particularly charities), even when they don’t take on investment, by helping them focus on improving their performance and explore other growth channels that do not involve debt. As of June 2015, four investments totalling EUR 1.2 million (GBP 1 million) had been raised as a result of Breakthrough grants.

Lessons learnt and conditions for potential replicability

Lessons learnt

One of Big Potential’s strengths is as a mechanism promoting social investment and supporting the investment readiness of all VCSEs. The event programme, the information resources featured on the website and the online provider marketplace are important tools that broaden its impact beyond successful applicants.

Another asset is that Big Potential appointed an evaluation partner right from the onset, allowing it to introduce changes and improve operations over the course of the programme. Big Potential will also create an important dataset to inform new policies and programmes supporting VCSEs.

Condition for potential replicability

Big Potential could be replicated in other countries, taking into account the following key lessons:

-

design the programme according to a robust needs assessment, based on prior research or evaluation results of similar programmes under way in the locality where it will be undertaken

-

hire a grant-fund programme manager with sufficient expertise in, and experience of, working with social enterprises on investment readiness and capacity-building

-

develop and maintain a good marketplace of support providers to ensure choice and competition, and allow the grantee to select a provider with matching values

-

create an expert panel that will make grant decisions

-

establish a mechanism to provide unsuccessful applicants with proper feedback, to allow them to learn and develop

-

develop and engage a variety of marketing channels/partners to reach VSCEs; build a good website to promote the programme; and involve social enterprise networks and other specialist organisations

-

appoint an evaluator early on and perform ongoing programme evaluation to introduce changes that improve its overall effectiveness.

Two issues should be kept in mind when considering replication:

-

Big differences exist in the organisational culture of organisations that start with a charity mindset and those that start from an enterprise approach, resulting in the need for more nuanced support. This may be even more pronounced in different national contexts. This could be improved by having two distinct programmes – one aimed at trading businesses and one aimed at capacity-building and change for social organisations wishing to become fully trading social enterprises..

-

The programme initiator should decide whether to focus on helping organisations raise social investment or to include the additional objective of enhancing the organisations’ overall sustainability. While evaluation of Big Potential is still at an early stage, its biggest impact may consist in helping grantees become more sustainable as a result of the consultancy support, even if they do not take on repayable investment.

References

Bland, J. (2010), Social Enterprise Solutions for 21st Century challenges: The UK Model of Social Enterprise and Experience, Publication of the Finish Ministry of Employment and the Economy – Strategic Projects 25/2010, TEM, Helsinki.

Hazenberg, R. (2015), Big Potential Breakthrough Evaluation Report Year 1, University of Northampton, http://nectar.northampton.ac.uk/7753/1/Hazenberg20157753.pdf.

H.M. Government (2011a), A Guide to Mutual Ownership Models, HM Government Department for Business, Innovation and Skills, London, https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/31678/11-1401-guide-mutual-ownership-models.pdf.

H.M. Government (2011b), Growing the Social Investment Market, A Vision and Strategy, H.M. Government, London.

Gregory, D. et al. (2012), Investment Readiness in the UK, Big Lottery Fund, London, www.biglotteryfund.org.uk/global-content/research/uk-wide/investment-readiness-in-the-uk.

OECD/EU (2016), Inclusive Business Creation: Good Practice Compendium, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264251496-en.

Ronicle, J. and T. Fox, (2015) In Pursuit of Readiness: Evaluation of the Investment and Contract Readiness Fund, Ecorys, London, https://issuu.com/thesocialinvest/docs/icrf_final_report_final.

Notes

← 1. Based on the exchange rate of 1 July 2016 (GBP/EUR = 1.19), retrieved from: https://www.ecb.europa.eu/stats/exchange/eurofxref/html/eurofxref-graph-gbp.en.html.

← 3. “The term ‘mutual’ is used as an umbrella term for several different ownership models. The distinguishing characteristic of a mutual is that the organisation is owned by, and run for, the benefit of its members, who are actively and directly involved in the business – whether its employees, suppliers, or the community or consumers it serves, rather than being owned and controlled by outside investors” (H.M. Government, 2014a).

← 4. “Signposting is a service that provides information to entrepreneurs about where they can go and seek professional sources of information and assistance. This can be done through websites, information provided through public employment services and other partners (e.g. chambers of commerce) or media campaigns.”(OECD/European Union, 2016).

← 5. In addition to publicly available material about Big Potential, interviews were carried out with representatives of the Big Lottery Fund, SIB and Northampton University in June 2016.