Chapter 2. Environmental governance and management

Korea has made significant progress in environmental governance over the past decade, including introducing strategic environmental assessment, reforming environmental permitting and strengthening environmental standards. This chapter examines Korea’s environmental governance framework for environmental management, including mechanisms for horizontal and vertical co-ordination. It reviews the regulatory framework for environmental management, including for environmental impact assessment, land use planning and permitting, as well as enforcement and compliance assurance. It also briefly addresses the promotion of environmental democracy through public participation, access to information and environmental education.

1. Introduction

Korea has made substantial progress in implementing the 2006 OECD Environmental Performance Review (EPR) recommendations in the area of environmental governance. The most important achievements are related to the introduction of strategic environmental assessment (SEA), the ongoing environmental permitting reform, and the strengthening of air and water quality and emission/effluent standards. These policy areas, along with achieving more effective and efficient compliance monitoring, represent key priorities of the Ministry of Environment (MOE), as challenges in these areas still persist.

At the same time, further environmental management improvements are held back by insufficient collaboration among key government ministries, lack of environmental policy implementation capacity and political will at the provincial and local levels, and limited engagement of civil society in environmental decision making.

2. Institutional framework for environmental governance

Korea has a centralised system of environmental governance, albeit with significant devolution and delegation of policy implementation responsibilities to provincial and local governments. Local authorities’ political emphasis on economic growth, sometimes at the expense of environmental protection, and their capacity to adequately enforce environmental regulations remain key multilevel governance concerns, provoking a slow-down and in some cases reversal of the devolution process. At the national level, many environmental responsibilities (e.g. for water resource management) are fragmented across multiple ministries, and permanent rather than ad hoc co-ordination mechanisms have been put in place only recently.

2.1. National institutions and horizontal co-ordination

The MOE is responsible for environmental policy and legislative development, formulation and implementation of comprehensive plans for environmental conservation, and support for environmental management activities of local governments. Its annual budget grew by an average of 5.3% per year in real terms from KRW 3.6 trillion in 2006 to KRW 5.7 trillion in 2015. During this period the MOE lost some of its functions to other ministries: for example, management of the Emissions Trading Scheme was moved to the Ministry of Strategy and Finance (MOSF).

The MOE has four River Basin Environmental Offices, for the Han, Nakdong, Geum and Yeongsan river basins, and three Regional Environmental Offices, in Wonju, Daegu and Saemangeum, as well as the Metropolitan Air Quality Management Office in charge of improving air quality in the Seoul Metropolitan Area. The Regional Environmental Offices’ tasks include developing and implementing environmental management plans in their areas of jurisdiction, providing formal MOE opinions on environmental impact assessment (EIA) and SEA reports, and supervising compliance assurance by local governments. After a major acid leak in Gumi in September 2012, the National Institute of Chemical Safety was established as an affiliated agency of the MOE in September 2013 and made responsible for preventing and responding to chemical accidents and terrorism.

Other ministries with environment-related responsibilities include the Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs (MAFRA), Ministry of Trade, Industry and Energy (MOTIE), Ministry of Land, Infrastructure and Transport (MOLIT) and Ministry of Oceans and Fisheries (MOF). These ministries, along with the MOSF and the Ministry of the Interior (MOI), are part of the Commission on Sustainable Development, which since 2010 has been chaired by the environment minister. The commission, consisting of high-ranking public officials and experts, reviews the National Sustainable Development Master Plan as well as legislation and key administrative plans with sustainable development implications. Initially, the commission was convened under the president’s office, but was relegated to the MOE to make way for the Presidential Committee on Green Growth (PCGG) at the ministerial level (Box 2.1). That committee, established in 2009, became the prime minister’s responsibility in 2013 under a new administration that prioritises a “creative economy”. Such institutional instability may hinder effective environmental policy implementation.

The Presidential Committee on Green Growth was established in January 2009 to formulate, co-ordinate, monitor and evaluate Korea’s green growth strategy and policy. Its functions were further concretised in the 2010 Framework Act on Low Carbon, Green Growth, and in 2013 it came under the aegis of the prime minister’s office. The committee has formulated the National Green Growth Strategy and master plans on climate change response and energy, among other initiatives. In terms of co-ordination, ministries and subnational governments must report their green growth action plans to the PCGG annually. The PCGG took 267 green growth-related projects submitted by 20 ministries and offices, and streamlined them into nine core projects. It has also undertaken evaluations of green growth policy implementation and suggested direction for improvement. Green growth policy is implemented by individual ministries, other public institutions and local green growth committees.

The PCGG has been held up as an example of multi-stakeholder collaboration for green growth policy development. It is co-chaired by the prime minister, with members including representatives from ministries, national research institutes, universities, the private sector and civil society. Despite its multi-stakeholder structure, however, non-government members have voiced concern that their participation is limited and that it is difficult to make their voices heard. Members meet regularly: 21 standard meetings and 11 policy implementation review meetings were held between January 2009 and October 2012. Since 2013 the work of the PCGG has been divided into four subcommittees: on green growth strategy, climate change countermeasures, energy, and green technology and industry. Furthermore, five multi-stakeholder green growth consultative groups – in the fields of industry, finance, science and technology, green lifestyle, and green IT – have been established to provide feedback to the PCGG on the feasibility and practicality of implementation of the policies it proposes.

Source: GGGI (2015), Korea’s Green Growth Experience: Process, Outcomes and Lessons Learned; Choi (2014), “The green growth movement in the Republic of Korea: option or necessity?”; UNEP (2010), Overview of the Republic of Korea’s National Strategy for Green Growth.

Collaboration between key government players in the environmental field, such as the MOSF, the MOE, MOLIT, MOTIE and MAFRA, needs to be reinforced significantly to overcome a historical “silo culture” of adversity and competition. As part of Government 3.0, a concept unveiled in 2012, efforts are under way to make inter-agency collaboration more effective. For example, six regional Chemical Accident Prevention Centres were established in 2013 with staff from the MOE, MOTIE, Ministry of Employment and Labour, Ministry of Public Safety and Security, local governments and associated institutions. Regarding climate change, there is some co-operation between the MOE, MOTIE and MOLIT.

The main institutional challenges are in the area of water management. After extensive droughts in 2015, a Water Management Committee was established under the Office for Government Policy Coordination, bringing together representatives of MOLIT (responsible for water quantity management, hydropower generation and inter-regional water supply), the MOE (water quality management, aquatic ecosystem conservation, water supply and sewerage infrastructure), MAFRA (agricultural water use) and other stakeholders depending on the committee’s agenda, including representatives of subnational governments and state-owned corporations.1 Such collaboration on water resource management goes in the direction of the 2006 EPR recommendation to consider combining policy functions for water quantity and quality. Inter-agency consultations on water management highlighted the need for an overarching legal framework, leading to elaboration of the latest draft Framework Act on Water Management, being considered by the National Assembly. Eight drafts of such an act have been considered since 1997 to provide a legal foundation for integration of water management functions and systems. The lack of success so far has been attributed to political disagreement between stakeholder ministries.

2.2. Subnational institutions and vertical co-ordination

Korea is divided into eight provinces (do), one special autonomous province (Jeju), six metropolitan cities, one metropolitan autonomous city (Sejong) and one special city (Seoul). Other administrative divisions include cities of at least 150 000 people (si), counties (gun), townships and villages.

Provincial and city governments play an important role, administering environmental permits and enforcing environmental laws as statutory delegates of the MOE. They also develop and implement environmental conservation policies within their jurisdiction and are in charge of municipal waste management, local water supply and sewage treatment, as well as regulation of vehicle emissions and noise.

Since 2002, 328 environmental responsibilities have been devolved to local governments, and 128 further tasks have been delegated to them by the MOE (KEI, 2013). In 2008, decentralisation was reconsidered in the Special Act on Local Decentralisation and the Reform of the Local Administrative System, which stipulated more gradual devolution with priority on delegating rather than transferring responsibilities, and the return of certain responsibilities (e.g. chemical management) to the central level.

Most local authorities lack fiscal autonomy and rely on financial transfers from the central government. The degree of fiscal autonomy is defined as the ratio between local tax revenue and the local budget, with the gap covered by central government subsidies. The degree of fiscal autonomy ranges from 80% in Seoul to an average of 11.6% for gun governments; the overall average is 45%. While over 60% of the MOE budget is spent on support to local governments, responsibilities were often devolved to the provincial and local levels without sufficient funding. Financial transfers tend to address immediate priorities rather than long-term local capacity needs. As a result, subnational governments, especially outside the Seoul Metropolitan Area, lack human, technical and financial resources to carry out these responsibilities, notably in compliance monitoring and enforcement (KEI, 2012b). The MOE carries out a capacity building programme, including training, for local authorities to address this challenge.

While administrative capacity of local governments has substantially improved in recent years, the lack of competent local environmental staff remains a major constraint. Moreover, environmental tasks are often assigned low priority and fragmented across several divisions (e.g. in charge of health or forest management) within a local government (MOE, 2013). Local authorities seem to have particular difficulty handling air quality and industrial and commercial waste management issues, where powerful private sector interests are involved. More generally, local economic development considerations tend to take precedence over environmental ones.

General policy co-ordination between the central and local governments is carried out by the Local Government Policy Council, created in July 2015. The Central Government Policy Delivery Council also assists in communication between government levels. A joint annual evaluation assesses the performance of local governments in executing delegated responsibilities and state-funded projects (mostly using output indicators such as number of inspections conducted). Regional councils formed by the MOE and several local governments address specific environmental issues in some regions. Environmental co‐operative conferences on various environmental topics are held to promote vertical policy co-ordination. Still, the level of vertical collaboration is insufficient in some policy areas, including water resource management (Ahn et al., 2015).

3. Setting of regulatory requirements

Korea’s Constitution (Article 35) states that all people have the right to live in a healthy and pleasant environment. The country’s environmental regulatory framework is made up of laws, enforcement decrees, ministerial decrees and regulations. Since 2006, many issue-specific environmental laws have been amended, notably those governing air, water and soil pollution, as well as EIA; and several important new laws have been adopted, including the Framework Act on Low Carbon, Green Growth (2010) and the Environmental Education Promotion Act (2008).

3.1. Regulatory impact analysis

The quality of draft versions of new and amended regulations is considered by a “regulation self-evaluation committee” in each ministry. They deliver their opinion to an independent Regulatory Reform Committee, which deliberates further on the appropriateness and feasibility of the proposed regulatory change and may return the assessment to the ministry if it deems the analysis to be inadequate. In 2015, Korea’s score on the OECD Regulatory Impact Analysis (RIA) Index was slightly above the OECD average for both primary laws and secondary regulations (OECD, 2016). However, RIA applies mostly to regulatory proposals developed by the executive branch (OECD, 2015a).

RIA is a key part of the Korean government’s “cost-in cost-out” initiative. Following a court decision imposing rigorous (“scientific”) cost-benefit analysis of draft policies and regulations, the MOE developed a manual for such analysis of environmental measures and works with other agencies to conduct quantitative analysis of costs and benefits of draft regulations. As of early 2016, only eight draft regulations had undergone cost-benefit analysis. In cases where such quantitative analysis is complicated, regulations are assessed using indices based on qualitative evaluation of their potential economic, social and financial impact.

Two independent RIA centres have been established, under the Korea Development Institute and the Korea Institute of Public Administration, to ensure that all the RIA requirements are fully met and that government does not view RIA as a formality. In September 2015, the government introduced an e-RIA system enabling officials to prepare, submit and review RIA reports online (OECD, 2016). All RIA reports are published on the relevant ministry websites. The public can comment on drafts of major laws, but not on proposed implementing regulations (Chapter 5). Ex post evaluation of the impact of environmental legislation is part of several legislative review and improvement programmes.

3.2. Key regulatory requirements for economic activities

This section provides a brief overview of instruments used to regulate air and water quality and respective pollution releases. Waste management regulations are addressed in Chapter 4.

Air quality and emission standards

Korea sets ambient air quality standards for seven major pollutants: SO2, NO2, CO, fine particulate matter (PM10 and PM2.5), ozone, lead and benzene. Industry-specific emission standards are set for 26 substances. They have been progressively tightened every five years; the most recent ones went into effect in 2015. Even stricter emission standards can be applied to industrial complexes (as is the case for the Ulsan-Onsan and Yeosu industrial complexes) and other areas of severe air pollution designated as “air conservation special countermeasure areas”.

Emission standards can be made more stringent by a municipal ordinance in designated “air quality control areas” and other areas where it is difficult to meet national or regional air quality standards. For example, industrial installations emitting air pollutants in the Seoul Metropolitan Area are regulated by the Special Act on the Improvement of Air Quality in Seoul Metropolitan Area (2003), which established an emission control regime as part of an air pollutant emission cap management system for the entire metropolitan area (Box 2.2). In addition, the Clean Air Conservation Act (2007) requires facilities that produce fugitive dust (over 80% are construction businesses) to report to the local government and adopt preventive practices promoted by the government through continuous guidance, inspections and education.

The Seoul Metropolitan Area air pollutant emission cap management system has been implemented since 2008 as part of measures to control metropolitan air quality. It allocates yearly emission allowances for nitrogen oxides (NOx) and sulphur oxides (SOx) to large facilities, requiring them to keep their emissions within the allowances and allowing them to trade any surplus allocations. Fines are imposed on facilities that exceed their total allocated emission amount and have not purchased adequate allowances to cover the excess emissions. The system initially covered 117 of the largest-emitting installations and has gradually been expanded to lower emitters; 295 facilities were participating by the end of 2013.

Allocations in the first year, 2008, were 2.3 times higher than emissions for NOx and 2.1 times higher for SOx, casting doubt on the system’s effectiveness. However, allocations have since been continuously reduced, and in 2013 NOx and SOx allocations exceeded emissions by only 20%. Emission trading affected only 1.4% of NOx emissions and 0.5% of SOx emissions in 2008, but by 2013 the respective shares were 6% and 23%, at unit prices of KRW 285 000 per tonne of NOx and KRW 180 000 per tonne of SOx. Future allocations are expected to be assigned at the levels of actual emissions, further increasing demand for emission trading. Now that the system has been tested and shown to work, it could be expanded to other parts of the country with large industrial complexes.

The Seoul Metropolitan Air Quality Control Master Plan (2005-14), aimed at improving PM10 and NO2 concentrations to the levels of Tokyo, Paris and other major cities by reducing air pollutant emissions by half from 2001 levels by 2014. While air quality improved significantly over the period, the concentration targets were not achieved. In 2013, a second master plan (2015-24) was formulated, adding targets for PM2.5 and ozone. Measures to achieve these goals consist of motor transport management – including a project to reduce exhaust gas from vehicles in operation – and total emission load management for large installations.

Source: MOE (2015), Ministry of Environment, brochure, http://eng.me.go.kr/eng/file/readDownloadFile.do?fileId= 115224&fileSeq=1&openYn=Y.

Korea has made considerable progress with respect to the 2006 EPR recommendation to strengthen vehicle emission and fuel efficiency standards. In 2009, it adopted California’s “fleet average” system for non-methane organic gases (NMOG) from petrol-fuelled vehicles, in which a carmaker can offer a range of models with different emission levels as long as its fleet meets a prescribed level of average NMOG emissions, which is lowered over time. Diesel vehicle emission standards follow the European example and were last updated in 2013. Since 2014, diesel emissions have been regulated under Euro 6 limit values. As studies have shown the real-world NOx emission performance of Euro 5 and 6 vehicles to be far poorer than test-cycle measurements in laboratories (Carslaw et al., 2011; Franco et al., 2014), Korea introduced real-driving emission standards on top of existing in-laboratory standards in 2016 (MOE, 2016a). Fuel regulations also apply; for example, the sulphur content of diesel and heavy fuel has been regulated since 1981, and standards have been continuously tightened. Since 2012, diesel fuel supplied throughout the country must have a sulphur content at or below 0.1% (MOE, 2015).

Water quality and effluent standards

Since the early 2000s, water management policies have focused on river basins to address conflicts between upstream and downstream reaches and between urban and agricultural regions. The key instruments of river basin management include the Total Water Pollution Load Management System (TPLMS) (Box 2.3), riparian zone designation, land purchase and establishment of a river management fund from water use charges.

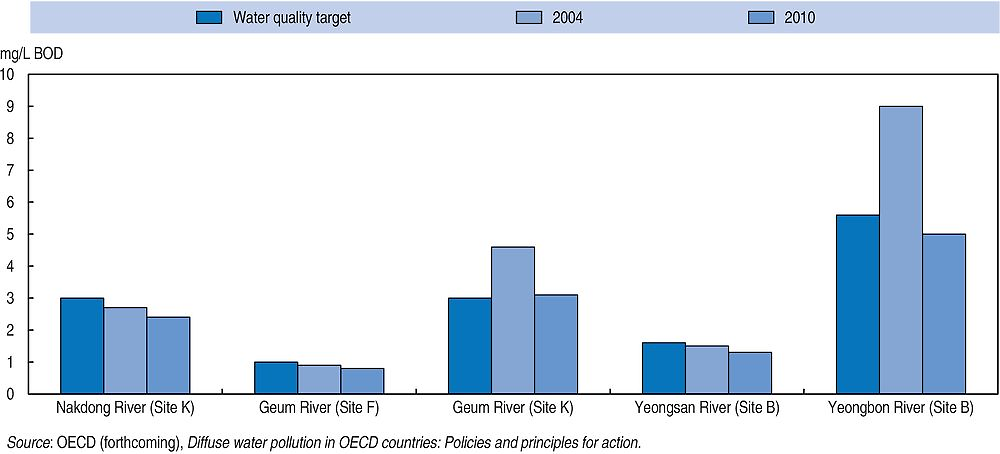

The TPLMS sets water quality goals for each river basin based on scientific evidence, limiting the total amount of pollutant load for each water body. It also calculates total pollutant discharges to reach these goals, and allocates discharges to each local government in the river basin to keep the total volume of emissions from each section under the permissible level. If the total pollution load for certain parameters is exceeded, specific measures to reduce it are prescribed, with the MOE monitoring their implementation. Only biochemical oxygen demand (BOD) was targeted by load management until 2010 (leading to a more than 60% reduction in BOD discharges compared to 2002); in stage 2 (2011-15), total phosphorus was added as a target pollutant, and there are plans to expand the coverage to other substances.

Initially, three river basins (Nakdong, Geum and Yeongsan-Seomjin) had to carry out load management if they did not reach the water quality goals. Since June 2013, the TPLMS has been extended to the Han River basin and areas that are not part of the four major river basins but are affected by severe water pollution. As of June 2015, the TPLMS had been implemented by 122 local governments. Pollution load is allocated from top to bottom: from the watershed to each local government, then to a group of pollution sources, then to individual facilities. Feasibility, equity, cost of pollution reduction and local policies are all factors in load allocation.

Local governments applying the TPLMS must formulate a pollution load management master plan that includes pollution load allocation and reduction plans to meet the targets. “Basic plans” at the watershed level are developed under the jurisdiction of metropolitan mayors or provincial governors and are approved by the MOE, while more detailed “action plans” are submitted by local mayors for approval at the metropolitan or provincial level. The allocation of pollution load permits to individual facilities to attain and maintain the overarching target for the watershed is done in accordance with technical guidelines issued by the National Institute of Environmental Research.

The TPLMS has contributed to improving water quality in many previously polluted areas: in 2015, water quality targets were achieved in 75% of rivers, but in only 8% of lakes. The figure below demonstrates BOD reductions in the Nakdong, Geum, Yeongsan and Yeongbon rivers.

Source: MOE (2015), Ministry of Environment, brochure, http://eng.me.go.kr/eng/file/readDownloadFile.do?fileId=115224&fileSeq=1& openYn=Y.

Water quality targets are set for major rivers and lakes throughout the country. The water quality classification system consists of seven grades across seven pollution parameters for rivers and eight for lakes with respect to aquatic ecosystem protection (“living environment standards”), with a grade assigned to each river reach and lake as the water quality target. The criteria include biological water quality standards, as recommended by the 2006 EPR. In addition, ambient water quality standards for human health protection are set for 20 chemical substances, consistent with good international practice. While the water quality targets and standards are regarded as policy goals, the TPLMS pollution load limits are directly enforceable.

Effluent standards (discharge limits) have been set for 49 parameters, including organic substances, suspended solids and phenols. Their number has increased significantly since the 2006 EPR, and many standards (e.g. for total nitrogen and total phosphorus discharges) have been made more stringent, representing important progress. Receiving water body characteristics such as water quality grade are considered in the application of the effluent standards. To comprehensively manage the ecosystem impact of hazardous water pollutants, an effluent standard measured in “toxic units” (a composite measure of concentration reflecting the toxicity of individual substances) has been applied to industrial facilities and wastewater treatment plants since 2011.

With regard to diffuse water pollution, environment-friendly land use has been promoted from the early stages of development and land use projects by continuously applying non-point source (NPS) management provisions to 27 regulations and guidelines associated with EIA, city master plans and forestry legislation. Eight regions where diffuse pollution may significantly harm aquatic ecosystems were designated as NPS Control Areas, and pollution reduction projects involving land use improvement have been implemented.

3.3. Environmental impact assessment

EIA, in use since the early 1980s, is the cornerstone of Korea’s environmental regulation. The Environmental Impact Assessment Act (1993, last amended 2012) requires EIA as a precondition for a construction permit in 17 activity sectors (80 types of projects), mostly covering infrastructure development. The government plans to extend EIA requirements to several other types of projects. However, for industrial sites, only those with a surface area greater than 150 000 m2 are subject to EIA, but these accounted for less than a quarter of EIAs conducted in 2011 (KEI, 2012a). This size criterion does not take account of the potential environmental impact of an industrial facility and may leave many hazardous facilities outside the EIA coverage.

EIA scoping, including description of alternatives (but not concerning site selection, already determined in a master plan), is set out in a preliminary assessment report reviewed by the EIA Council. The council is made up of representatives of the approving authority (a local government or a ministry), other relevant public officials, experts and residents’ representatives. The 2012 amendment of the EIA Act gave residents near the work site – but not the public at large or non-government organisations (NGOs) – an opportunity to comment as early as the EIA scoping phase, and again while a draft EIA report is prepared. However, there is no obligation for authorities to consider the public’s comments (Chapter 5). The EIA report is submitted to the approving authority, which must consult the MOE before deciding whether to grant the permit. After the report’s approval, the operator is responsible for monitoring the project’s impact and reporting to the MOE and the approving authority.

A project that does not fall under EIA Act requirements may undergo an EIA by a local government (in metropolitan cities, provinces and cities with a population of at least 500 000) based on a local ordinance if the project raises local environmental concerns. As of 2014, eight local governments, including the cities of Seoul, Busan, Incheon and Daejeon, had applied this provision.

A simplified, small-scale EIA can be used when a development project is planned in one of the 19 environmental conservation areas designated under the National Land Planning and Utilization Act (2002), Mountainous Districts Management Act (2002), Natural Parks Act (1980, amended 2001) and Wetlands Conservation Act (1999). The developer must prepare a small-scale EIA report and request approval from the MOE. No public participation takes place as part of this procedure (MOE, 2015).

An extensive information and services network supports the EIA procedure. The online EIA Support System provides EIA-related information to the project proponent, the local authority and the public to ensure transparency. The MOE has developed about 50 guidelines and regulations on EIA in specific activity sectors. The Korea Environment Institute (KEI) has been a professional reviewing agency for EIA matters since 1997. The KEI reviews assessment reports and delivers formal opinions upon request from the MOE. An EIA Agent System aids the MOE in licensing professional engineers and EIA consulting firms. There were more than 330 EIA consulting firms in 2012 (KEI, 2012a).

By late 2014, over 5 100 EIAs had been conducted, with nearly 90% of EIA reports approved, almost always with additional environmental conditions. The effectiveness of the EIA system is illustrated by the fact that, between 2012 and 2015, EIA conditions imposed on industrial complex projects led to emission reductions of 56% for cadmium and 27% for PM10, as well as 46% more green space conservation, compared to projections of preliminary assessment reports (MOE, 2016).

3.4. Land use planning and strategic environmental assessment

Korea faces rapid urbanisation and deterioration of natural ecosystems. The surface area of urbanised and dry areas doubled between 1989 and 2009; over the same period, the area of grasslands decreased by 24% and of wetlands by 61% (MOE, 2016). To address this challenge, the comprehensive national land plan (2006-20, modified 2011), lays out a vision of “global green national land” for Korea, while the fifth National Forest Plan (2008-17) calls for “establishment of a balanced mountainous district management system” and expansion of green urban spaces.

The provisions of the comprehensive national land plan, comprehensive provincial plans and regional and sector plans are used to develop larger city (si) and county (gun) master plans, which guide local authorities’ more specific management plans. For example, the third Seoul Metropolitan Area Readjustment Plan (2006-20) and Sejong Urban Master Plan (2015-30) integrate sustainable mobility considerations pursuant to the 2006 EPR recommendation on better integration of transport, housing and land use policies in the context of sustainable development.

In addition, the concept of concurrence between national plans for land and for environment entails close co-ordination between land use plans and Basic Plan for Natural Environment Conservation (the current one, the third, covers 2016-25) at an early stage. This concept was inscribed in amendments to the Framework Act on Environmental Policy in December 2015, and the MOE has prepared general guidelines for its implementation, but implementing it requires increased collaboration between the MOE and MOLIT. Such concurrence allows environmental considerations to be better taken into account in land use planning and should be pursued further.

Various development acts, such as the Industrial Sites and Development Act (2009), have complicated land use planning. Industrial complexes, power sector facilities, even urban residential areas are routinely developed either bypassing regular territorial planning or having the latter validate predetermined development projects. As a result, in many instances planning is led by development rather than guiding it (Lim, 2014). Various development acts have complicated the planning system that controls territorial development.

By 2016, the MOE had reviewed 75% of environmental regulations and revised “unrealistic and unreasonable” ones to facilitate business investment and economic revitalisation (CMEJ, 2016). For example, green belt restrictions could be lifted in the Seoul region, enabling development in areas of high conservation value. There is evidence that economic development and investment increasingly take precedence over biodiversity conservation. Two high-profile cases are proposals to build a ski run for the 2018 Winter Olympics in a native forest and to install cable cars in some national parks (e.g. Seoraksan Mountain National Park). Currently pending in the National Assembly is an act to promote tourism in mountain areas, which would allow tourism infrastructure development in protected and other ecologically sensitive areas. Local governments, which have recently assumed the management of many protected areas, largely support such initiatives, which pose concerns for biodiversity that is already under high pressure from urbanisation (Chapter 1). In addition, there is a proposal to lift a ban on siting new polluting facilities in areas that do not meet environmental quality standards.

SEA was introduced in 2006, in line with that year’s EPR recommendation to enhance environmental review of land use planning. In reviewing the environmental appropriateness of a plan, it focuses primarily on location. SEA targets 17 types of policy plans in eight policy areas (including urban development and road construction), but not sector development policies, and 95 types of development master plans in 17 areas, but not covering all 250 county and city spatial management plans. Land use plans are developed under the supervision of MOLIT, which has its own assessment system. Co-ordination between the MOE and MOLIT on SEA coverage and implementation is often challenging.

SEA of a policy plan evaluates conformity with national environmental policy and the target area’s environmental capacity. SEA of a development master plan takes into account the impact on natural landscape and biodiversity, existence of adequate environmental infrastructure, compliance with environmental standards, and resource and energy efficiency considerations. A “natural landscape deliberation system” was introduced in 2006, also in response to a 2006 EPR recommendation, with the adoption of guidelines on evaluating landscape impact of development projects as part of SEA.

A preliminary assessment report defining the SEA scope (target area, proposed land use and alternatives) is reviewed by the EIA Council. The authority responsible for the plan must request the MOE consent prior to approval of the SEA report (the MOE may ask the KEI or other experts for technical advice or a field survey). Residents’ opinions on the draft SEA report are solicited through public notice, presentation or hearing, but only in the case of a development master plan, which limits the extent of public participation. Areas with high ecological value are an exception (section 5.1).

3.5. Environmental permitting

Korea is undertaking a major environmental permitting reform, moving from issue-specific to integrated permitting for large industrial installations. The existing system has 10 environmental permits prescribing uniform emission limit values (ELVs) for each activity sector, with permitting procedures involving multiple authorities and 73 types of documents. Any facility with a potentially significant air emission or wastewater discharge, for instance, must obtain a permit from, or file a report with, the local government. The regulatory regime depends on whether the facility would release any specified hazardous air or water pollutants, or is located in an environmentally sensitive area. Self-monitoring requirements are more stringent for permitted facilities.

The new integrated permitting system, inspired by the EU system of integrated pollution prevention and control (IPPC) and following best international practices, is being introduced following adoption in November 2015 of the Act on Integrated Management of Environmentally Polluting Facilities. It is expected to go into force in 2017, starting with power and heat generation and incineration facilities. The government was expected to adopt implementing regulations in the second half of 2016. This reform directly responds to the 2006 EPR recommendation to introduce IPPC permits for large stationary sources at the national and regional levels.

The new system will be applied to 19 industry sectors once the regulatory framework is complete. Best available techniques (BAT) will be identified for each sector by technical working groups and specified in BAT reference documents (K-BREFs, an analogue of EU BREFs, which are also prepared and revised through a robust technical expert process), taking into account potential compliance costs and economic feasibility. Industries participate directly in technical working groups to select and periodically review K-BREFs. A K-BREF with ELVs for the power generation sector was completed in 2014; the ones for the steel, non-ferrous metals and organic chemicals industries are under development. Seven K-BREFs are expected to be developed by 2021. Existing industrial facilities will be given a four-year grace period (until 2021) to obtain integrated permits and comply with new ELVs, customised for each installation by considering BAT and local environmental conditions. Mechanisms to link site-specific evaluation for permitting purposes with EIA for new facilities, to avoid duplication of assessment, are being considered.

The reform is expected to reduce the administrative burden by combining medium-specific permits into one through a single procedure involving online applications. The MOE is expected to become the sole competent authority for issuing integrated permits and controlling compliance with them, thus taking back much of environmental permitting responsibility from local governments. An Environmentally Polluting Facility Permit System Advancement Division is expected to be established within the ministry, supported by a technical expert panel. The role of the MOE’s regional offices and degree of co-ordination with local governments have not yet been defined, but it is clear that implementing the reform will require substantial capacity building at the MOE in issuing and enforcing integrated permits.

An online integrated environmental permitting system will be established to provide technical information and application support. Permits will be reviewed and revised every five to eight years. Unlike in the existing system, integrated permits will require facility operators to disclose information on their environmental impact. However, public participation is not envisaged as part of integrated permitting.

This reform will not affect industrial activities with low environmental impact – mostly small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). The administrative burden of current issue-specific permitting is particularly heavy for SMEs, which have little in the way of human resources and technical capacity. To simplify the regulatory regime for low-risk installations, Korea may consider replacing multiple permits with sector-specific general binding rules (GBRs), as other OECD countries have done (e.g. the Netherlands, Box 2.4).

The Netherlands has different requirements for three categories of installations, as defined in a 2008 decree:

-

Type A facilities, characterised by minimal environmental impact, are regulated by general, not activity-specific provisions; they do not need to notify the competent authority of their operations.

-

Type B installations have a moderate environmental impact, are covered by activity-specific GBRs and must notify the competent local or provincial authority of the nature and size of their activities four weeks before starting operations.

-

Type C installations have a potentially important impact and require an environmental licence, which they have to comply with along with activity-specific GBRs. This category includes large installations which are subject to the EU Industrial Emissions Directive and need an integrated permit/licence.

GBRs establish “quantitative target-based provisions” (i.e. ELVs) that can be achieved by any “recognised” measure without prior consent from the competent authority, as well as “qualitative” provisions that require certain techniques or management practices that can be modified only with the authority’s consent.

GBRs have been developed for activities related to hazardous substances, plastics, metals, paper and textiles, food products, vehicles and other motorised equipment, etc.

Source: Mazur (2012), “Green Transformation of Small Businesses: Achieving and Going Beyond Environmental Requirements”.

4. Compliance assurance

Korea has made significant progress since the 2006 EPR, which recommended increasing local inspection and enforcement capacity and strengthening related national supervision and evaluation mechanisms. The central and local governments have been reinforcing their compliance assurance programmes to better detect and deter non‐compliance (environmental liability regimes are discussed in Chapter 5). The national government is also actively promoting voluntary compliance and adoption of green business practices.

4.1. Environmental inspections

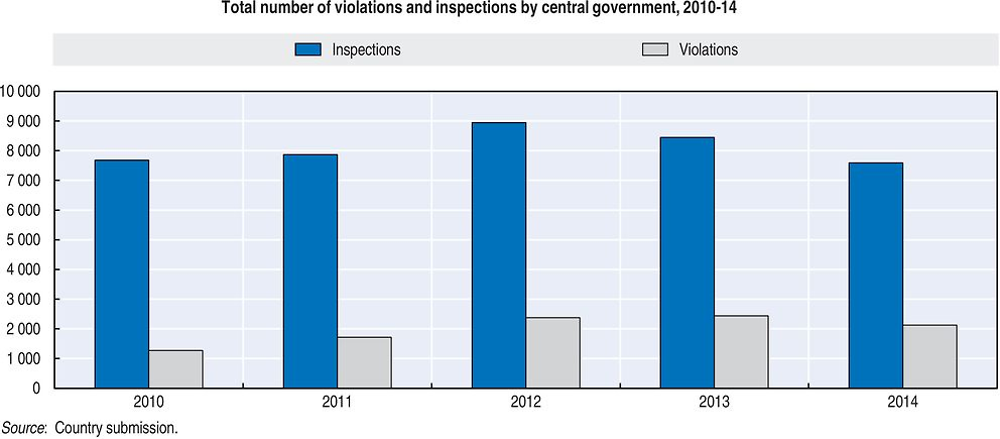

Compliance monitoring responsibilities for stationary sources (in all areas except management of designated hazardous waste) was transferred in 2002 from the MOE to local governments (the authority that issues a permit also monitors compliance with it), but in 2015 toxic chemicals control reverted to the MOE because local management of major chemical accidents had been insufficient. Figure 2.2 presents the number of local authority inspections and identified violations in 2006-14. Although the frequency of site visits fell – after a tele-monitoring system for air and water pollution from large facilities was introduced and inspections were focused on recidivist violators, but also due to resource constraints – the detection rate (the ratio between the number of detected offences and the number of inspections) grew steadily from 4.7% in 2006 to 8.4% in 2014. To further increase detection rates, the MOE is encouraging local authorities to conduct more frequent random inspections. However, many municipalities do not have sufficient resources to do so. Local governments also rely on civil environmental monitoring groups to signal visible offences. Better targeting of inspections, based on the level of environmental risk of individual facilities, would help make compliance monitoring more efficient.

The staff of the MOE’s regional and river basin offices include environmental police who supervise and complement local authorities’ compliance monitoring activities. They focus on highly polluted areas and recalcitrant offenders. Detection rates of MOE inspections grew from 16.6% in 2010 to 28% in 2014 (Figure 2.3). In addition, since 2013 the MOE’s head office has had a Central Environmental Controls Task Force dedicated to compliance monitoring of the largest polluters or those provoking frequent citizen complaints. Thus far the task force has targeted over 630 polluting installations with an offence detection rate of 43.1%. Its recent focus was discharges from public sewage treatment plants and illegal wastewater dumping. MOE compliance monitoring capacity was further reinforced in 2016 by the creation of an Environmental Offence Investigation Planning Division.

The transition to integrated environmental permitting also entails reform of the compliance monitoring regime, from largely reactive inspections triggered by incidents or complaints to planned periodic controls with a frequency based on the installation’s level of risk.

4.2. Enforcement tools

Very significant criminal sanctions for non-compliance are set in issue-specific environmental laws. Criminal fines for operating without a permit are up to KRW 50 million under the Water Quality and Ecosystem Conservation Act (2005) and up to KRW 100 million (KRW 200 million in the Seoul Metropolitan Area) under the Clean Air Conservation Act (2007). In addition, if there are aggravating circumstances in terms of damage to public health or the environment, heavier criminal penalties (three or more years of imprisonment) can be applied under the Act on Special Measures for the Control of Environmental Offences and Aggravated Punishment. There are plans to amend this act in the near future to make the sanctions even more severe.

In practice, however, sanctions of this degree are rarely applied. For criminal proceedings to take place, the MOE or the local authority that identifies a violation must refer the case for investigation to the special environmental police and then to the public prosecutor, who decides whether to pursue it in court. In 2013, such referrals occurred in only 1.8% of local authorities’ enforcement cases related to air pollution and 1.5% of water pollution cases (MOE, 2014). Public prosecutors assign relatively low priority to environmental offences and rarely pursue such cases. Judges generally lack expertise to consider the merits of environmental cases. The MOE would be well advised to work more closely with prosecutors’ offices and the courts to build capacity in this area.

At the same time, administrative sanctions are relatively weak: authorities can impose light monetary penalties for minor offences and issue orders to stop the polluting activity, but violators can avoid this by paying a higher “excess” pollution charge. Polluters often get away with a simple warning: in 2013, for air pollution cases, warnings accounted for 57% of local authorities’ administrative enforcement actions, cessation orders for 30% and corrective action for only 13%. With respect to wastewater discharges, the administrative response tends to be more robust, with 35% of actions ordering corrective measures (MOE, 2014).

4.3. Promotion of compliance and green practices

The MOE promotes good environmental behaviour in the regulated community through voluntary agreements, information-based instruments and regulatory incentives.

Voluntary agreements and corporate social responsibility

The ministry makes extensive use of various kinds of voluntary agreements to address key environmental issues in a non-regulatory manner. Voluntary agreements help industry to either avoid additional regulation or better prepare for it, and to improve relations with affected communities. Examples of such agreements include the following:

-

Since 2013, four-year voluntary agreements have been concluded with 31 companies in the Ulsan, Yeosu, Daesan and Ochang regions to reduce emissions of carcinogens (benzene, butadiene, etc.). In total, these agreements are expected to reduce Korea’s emissions of carcinogenic substances by 14% compared to the 2012 levels.

-

Two four-year regional agreements in the Kwangyang Bay and Ulsan areas have engaged 40 companies in voluntarily designing and implementing their own reduction plans for particulate matter, SOx, NOx and volatile organic compounds (VOCs). A 2012 sector-wide agreement with the shipbuilding industry (six companies) targeted VOCs and a 2014 agreement with 26 cement, power generation, and steel and iron manufacturing firms focused on voluntary cuts in SOx, NOx and particulates. Overall, the pledged reductions would amount to about 1% of the country’s emissions of these pollutants.

-

In 2015, the MOE signed an agreement with three online trade companies that pledged to strengthen their internal controls to prevent illegal online sales of toxic chemicals.

-

The MOE, the automobile industry and the fuel industry agreed in 2011 to contribute a total of KRW 1 billion, in equal shares, to the Auto-Oil Program, a public-private research project aimed at reducing emissions of greenhouse gases and other air pollutants from motor vehicles.

To promote corporate social responsibility, the government issues the Grand Award for Excellence in Sustainability Management to large enterprises and public institutes; 124 awards were conferred in 2014. They are based on annual sustainable management reports as well as business and consumer surveys. The number of enterprises publishing such reports went from four in 2003 to 224 in 2014, including 64 of the top 100 Korean companies (MOE, 2016). The award criteria cover such areas as corporate environmental management, sustainable use of resources, green management of the supply chain, enhanced management of hazardous substances and actions related to climate change.

Advice and guidance

The MOE provides information on environmental regulations and green business practices through its website and printed materials, and operates a web-based helpline where regulatory questions must be answered within five working days. The Korea Environmental Industry and Technology Institute (KEITI) operates the Green-Up programme, a customised consulting service for environmental improvement of SMEs. It also offers financial support for environmental performance audits.

Environmental management system certification and awards

The Green Enterprise certification programme was established in 1995 and converted in 2010 into a statutory programme under the Environmental Technology and Industry Support Act. The MOE, through its regional offices, designates as Green Enterprises businesses that undertake substantial voluntary reductions of pollutant releases, carry out resource and energy saving measures, improve their products’ environmental characteristics, adopt environmental management systems (EMS), etc.

Green Enterprises can submit a declaration instead of applying for a permit, are exempted from periodic inspections and are subject to more lenient penalty rules, which are important regulatory incentives for going beyond environmental compliance. The MOE periodically reviews a company’s Green Enterprise designation and can cancel it if the company’s environmental performance deteriorates. As of September 2014, there were 197 Green Enterprises, including 52 in the chemicals sector and 39 in electronics (MOE, 2016).

To facilitate access to finance, a support system for green businesses called enVinance has been established to give the financial sector information on eco-friendly companies. The government created a database of information from ministries on green businesses (including environmental performance) and makes it available to financial institutions to help them better evaluate businesses when deciding which ones to provide loans to or invest in.

ISO 14001 EMS certification has been very popular among Korean companies, primarily due to international market demand. Between 2002 and 2012, the number of certified firms increased tenfold, though it has declined somewhat in recent years. The government promotes EMS certification through reduced frequency of environmental inspections. Korea’s SME agency also has a programme to encourage EMS certification among small businesses.

Green public procurement

Korea has a well-developed system of green public procurement (GPP). Although GPP has been encouraged since the 1994 Development and Support of Environmental Technology Act, the 2005 Act on Promotion of Purchase of Green Products made it obligatory for all government agencies (including local authorities) and other public institutions. Public institutions must buy products that are certified by Korea Eco-Label or the Good Recycled Mark, or that meet other environmental criteria set by the MOE, assuming such products are available, can be supplied in a stable manner and are of sufficient quality. However, neither producers’ environmental compliance records nor EMS certification are among the selection criteria. Incorporating these into the GPP system would help promote better environmental performance of government suppliers. More details on Korea’s GPP system can be found in Chapter 3.

5. Promoting environmental democracy

Since 2006, Korea has established a firm legal and policy framework for environmental education and a multitude of programmes to raise environmental awareness of students and the general public. At the same time, it has a fairly restricted system of public participation and access to information on environmental matters. While NGOs are involved in strategic policy planning, there is no public participation in law making, and public engagement in environmental assessment remains limited to local residents. Despite growing disclosure of environmental information, much of it remains classified to protect private economic interests. Public participation and access to justice and information are addressed in detail in Chapter 5.

5.1. Public participation in environmental decision making

The main national stakeholder consultation body on environment is the Central Environmental Policy Committee, which is involved in developing the Comprehensive National Environmental Plan, conservation master plans and other policy documents. It has almost 200 members from academia, research institutions, private companies, etc. There are also issue-specific stakeholder committees, such as the river basin management committees in each river basin, the Environmental Health Committee and the Chemicals Evaluation and Management Committee.

Large NGOs, such as the Korean Foundation for Environmental Movements and Green Korea United, actively seek to influence national environmental policy making. NGO representatives can participate as technical experts in consultative bodies but not promote their organisations’ policy agendas. A significant reduction in the number of stakeholder co-ordination bodies in recent years has contributed to distrust between the government and civil society groups. Unlike in most OECD countries, NGOs in Korea generally do not receive government financial support.

In accordance with the Administrative Procedure Act (1996) and the Operational Regulation of Legislative Affairs (1998), the main provisions of every draft law and most executive regulations are announced through the media and the government’s public relations portal (www.epeople.go.kr). The public then has 40 days to submit comments and opinions.

Public participation in EIA and SEA is restricted to residents of the area affected by the proposed project or plan (as defined by government authorities) and does not include the wider public. Citizens living outside the designated “impact area” who feel affected by the project or plan can appeal to the MOE or their local government, but do not have judicial recourse. Non-residents can express opinions only on plans related to areas with “high ecological value”. EIAs do not have to be announced in the mainstream media, public hearings serve mostly to inform rather than seek comments, and there is no obligation for authorities to accept citizens’ proposals. Nor does the integrated permitting reform (Section 3.5) envisage public participation in permitting decisions.

This lack of transparency has led to strong, sometimes unconstructive, citizen opposition to major government-promoted projects, such as the Four Rivers Restoration Project (Chapter 3), nuclear power plant construction and siting of hazardous facilities (Bell, 2014). An effective conflict resolution mechanism is needed to address this issue and ensure that government works in partnership with NGOs.

5.2. Access to environmental information

The public is entitled to access to environmental information under the Official Information Disclosure Act, except in cases where disclosure “may interfere with government business” or damage the company or organisation in question. Any applicant denied access to information is entitled to an administrative hearing or administrative court action under the Administrative Procedures Act.

Korea has had a pollutant release and transfer register (PRTR) since 1999. Pollution release data by industry sector and by pollutant are publicly available on the PRTR website. The 2015 Act on Integrated Management of Environmentally Polluting Facilities requires facilities with environmental impact above defined thresholds to disclose their integrated permit applications and annual reports containing data on pollution releases, except when this information is judged commercially sensitive. Although businesses must provide formal justification for non-disclosure of information for commercial confidentiality reasons to a special government commission for approval, many civil society groups feel it is difficult to obtain timely information from private enterprises.

The MOE provides a wide range of environmental information to the public, including the annual Environmental Statistics Yearbook and the biennial Ecorea white paper. Environmental authorities maintain records on all regulated entities, including permit applications, regular self-monitoring reports and inspection reports. The Government 3.0 initiative, launched in 2013, aims to open up public data and foster its reuse by business as well as the administration (OECD, 2015b). As a result, the disclosure rate of environmental information produced or managed by government rose from 24% in 2012 to 55% in 2013 (MOE, 2016). The MOE intends to disclose 80% of government-held environmental information by 2017 through Korea’s main information portal (www.data.go.kr) or on the MOE website.

5.3. Environmental education

In line with the 2006 EPR recommendation on raising public awareness of environmental issues, the Environmental Education Promotion Act (2008) provided the basis for measures to promote environmental education, many of which were envisaged in the Environmental Education Master Plan (2011-15). An Environmental Education Promotion Committee was formed in 2010 and an Environmental Education Development Council in 2013. A network of national environmental education centres has been functioning since 2012. An environmental education internet portal created in 2008 shares education materials and other relevant information.

Korea has made substantial progress in expanding environmental education in schools. This is particularly important in the context of its heavily test-driven education system, which leaves little space for behavioural learning. To provide assistance for school environmental education, the National Environmental Education Centre has been operating since 2012, and an environmental education teaching tool has been available since 2007. Over 350 000 students from more than 3 000 elementary schools were reached between 2004 and 2014 by Pureumi mobile environmental classrooms – trucks or buses remodelled and equipped with educational tools. After-school environmental classes have been given in over 340 schools since 2013. Environmental experience education programmes receive state support of almost KRW 1 billion per year (MOE, 2016).

In the area of social environmental education, an environmental education promotion team numbering 400 people in 2015 conducted about 2 000 awareness-raising sessions for businesses, local governments, military troops, etc. Over 300 environmental education programmes have received official certification since 2010, further illustrating Korea’s achievements in this area.

-

Support a whole-of-government approach to water resource management by building on the existing collaboration platforms for policy dialogue between all relevant government stakeholders and adopting a Framework Act on Water Management; strengthen co‐ordination between ministries on other key environmental issues, including climate change, chemicals safety and biodiversity.

-

Build provincial and local governments’ capacity to carry out their statutory environmental responsibilities and tasks delegated to them by the central government; provide the necessary financial resources to ensure effective enforcement of national environmental regulations; strengthen the system of environmental performance indicators for all levels of government.

-

Reinforce ex ante assessment of environmental policies and regulations through wider application of cost-benefit analysis, and expand ex post evaluation of their implementation.

-

Continue to expand the coverage of the EIA and SEA systems by making hazardous industrial facilities subject to EIA independently of their size and requiring SEA for a wide range of government policies and programmes with potential impact on the environment, including all local land use plans. Ensure appropriate use of these instruments to prevent uncontrolled development in environmentally sensitive areas; pursue closer co-ordination between land use and nature conservation plans.

-

Ensure coherent introduction of integrated environmental permitting reform for major industrial polluters on the basis of best available techniques, accompanied by capacity building for competent authorities and broad stakeholder involvement; consider replacing single-medium permits for low-risk installations with sector-specific general binding rules.

-

Increase the efficiency of compliance monitoring through better targeting of inspections based on the level of environmental risk of individual facilities; strengthen administrative enforcement tools and build the capacity of public prosecutors and the courts in applying penalties for criminal offences.

References

Ahn, J.H. et al. (2015), Water and Sustainable Development in Korea: A country case study, Policy Study 2015-01, Korea Environment Institute, www.kei.re.kr/aKor/fBoardEtypeView.kei?khmenuSeq=3&cId=703438.

Bell, K. (2014), Achieving Environmental Justice: A cross-national analysis, Policy Press, Bristol, UK.

Carslaw, D.C. et al. (2011), Trends in NOx and NO2 emissions and ambient measurements in the UK, prepared for the UK Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs, London, http://uk-air.defra.gov.uk/reports/cat05/1108251149_110718_AQ0724_Final_report.pdf.

Choi, S.D. (2014), “The green growth movement in the Republic of Korea: option or necessity?”, Korea Green Growth Partnership/World Bank, Seoul/Washington, www.greengrowthknowledge.org/sites/default/files/kggp_knowledge%20note%20series_01.pdf.

CMEJ (2016), “Critical Review of Environmental Justice in South Korea”, report prepared for the OECD Environmental Performance Review of Korea by the Environmental Justice Institute of the Citizens’ Movement for Environmental Justice, Seoul.

Franco, V. et al. (2014), “Real-world exhaust emissions from modern diesel cars – A meta-analysis of PEMS emissions data from EU (Euro 6) and US (Tier 2 Bin 5/ULEV II) diesel passenger cars”, White Paper, International Council on Clean Transportation, Washington, DC.

GGGI (2015), Korea’s Green Growth Experience: Process, Outcomes and Lessons Learned, Global Green Growth Institute, Seoul, http://gggi.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/Koreas-Green-Growth-Experience.pdf.

ISO (2015), ISO Survey 2014, International Organization for Standardization, www.iso.org/iso/home/standards/certification/iso-survey.htm?certificate=ISO%209001&countrycode=AF (accessed on 31 January 2016).

KEI (2013), Advancing the environmental administrative system for efficient environmental resources management: the role of central and local governments (in Korean), Korea Environment Institute, http://library.kei.re.kr/dmme/img/001/014/002/사업보고서_2013-09-08_정우현.pdf.

KEI (2012a), “Environmental Impact Assessment System”, Korea Environmental Policy Bulletin, Vol. 10, No. 2, Korea Environment Institute, Sejong.

KEI (2012b), Diversification of environmental governance and policy implications (in Korean), Korea Environment Institute, http://library.kei.re.kr/dmme/img/001/014/001/사업2012_14_02_정우현.pdf.

Mazur, E. (2012), “Green Transformation of Small Businesses: Achieving and Going Beyond Environmental Requirements”, OECD Environment Working Papers, No. 47, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/5k92r8nmfgxp-en.

MOE (2016), “Response to the questionnaire for the OECD Environmental Performance Review of Korea”, Ministry of Environment, Sejong.

MOE (2015), Ecorea: Environmental Review 2015, Korea, Ministry of Environment, Sejong, http://eng.me.go.kr/eng/web/board/read.do?pagerOffset=0&maxPageItems=10&maxIndexPages=10&search Key=&searchValue=&menuId=30&orgCd=&boardId=565930&boardMasterId=547&boardCategoryId=&decorator=.

MOE (2014), Environment Statistics Yearbook, Ministry of Environment, Sejong, http://webbook.me.go.kr/DLi-File/091/020/003/5588561.pdf.

MOE (2013), White Paper on Environment (in Korean), Ministry of Environment, Sejong, http://library.me.go.kr/search/DetailView.Popup.ax?sid=11&cid=5566014.

OECD (2016), Government at a glance: How Korea compares, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264259003-en.

OECD (2015a), OECD Regulatory Policy Outlook 2015, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264238770-en.

OECD (2015b), Government at a Glance 2015: Country Fact Sheet – Korea, OECD Publishing, Paris, www.oecd.org/gov/Korea.pdf.

Park, K.S. et al. (2012), Environmental Law and Practice in South Korea: overview, Practical Law, http://us.practicallaw.com/2-508-8379 (accessed on 12 January 2016).

Lim, S.-h. (2014), Planning Practice in South Korea, www.academia.edu/12312831/Planning_practice_in_ South_Korea (accessed on 16 September 2016).

UNEP (2010) Overview of the Republic of Korea’s National Strategy for Green Growth, United Nations Environment Programme, Nairobi, www.unep.org/PDF/PressReleases/201004_unep_national_strategy.pdf.

Note

← 1. Other co-ordination committees on specific water-related issues include the Committee for Deliberation of Police on Water Quality and Aquatic Ecosystems and the Water Reuse Policy Committee.