Chapter 7. The violence lens and final recommendations

This final chapter of States of Fragility 2016 describes a tool for understanding violence better, and makes recommendations addressed at the broader fragility and violence community. The violence lens, a tool first presented by the OECD in 2009, is updated to better understand violence today. The report then highlights some areas where the development community can more effectively address fragility and violence. These are grouped as policy, programming and financing recommendations. The report concludes with a call to alleviate the toll of violence and fragility on those who are most left behind.

Understanding the findings through the violence lens

Violence – in all its complexity – is clearly a major issue. A better understanding of its trends and manifestations will help policy makers and practitioners design more effective approaches to reducing the fragility of states and societies. The violence lens, developed by the OECD in 2009 (Box 7.1), is an analytical tool that helps to frame the cause and effect relationship between the different factors influencing the emergence and persistence of violence, in order to identify options for violence prevention and reduction. It is updated here to reflect new research findings.

The 2009 armed violence lens captures key features and levels of armed violence. Its various components have been developed in consultation with development practitioners, and are grounded in the armed violence reduction programming lessons learned in conflict, post-conflict and crime-violence-affected contexts. The lens offers a flexible and unified framework for thinking about the context-specific drivers, risk factors, protective factors and effects. It is also unconstrained by preconceived assumptions regarding donor-imposed categories such as “conflict”, “crime” or “fragile”.

The armed violence lens underscores the way violence transcends separate development sectors, and highlights the potential for cross-sector and integrated responses. It also highlights the potential connections between different elements and levels: these are often treated separately due to disconnected sector or thematic programming streams. The lens encourages development practitioners to think outside their particular programming mandates and to consider the entirety of the challenges at hand.

A unified analysis of armed violence can help bring together a diverse array of actors who are otherwise working on different aspects of the issue. For example, it can assist practitioners working on criminal justice reform to consider how their programming efforts and objectives are potentially connected to interventions focused on community security, crime prevention, restorative justice, small arms and light weapons control or initiatives targeting at-risk youth. It can also encourage improved whole-of-government responses.

It is important to note that the armed violence lens should not supplant existing assessment and programming tools such as conflict or stability assessments; drivers of change, governance and criminal justice assessments; or a public health approach. Rather, it serves as a complementary framework that can help to identify how different tools and data sources can be combined to enhance existing diagnostics and formulate more strategic or targeted interventions.

Source: OECD (2009).

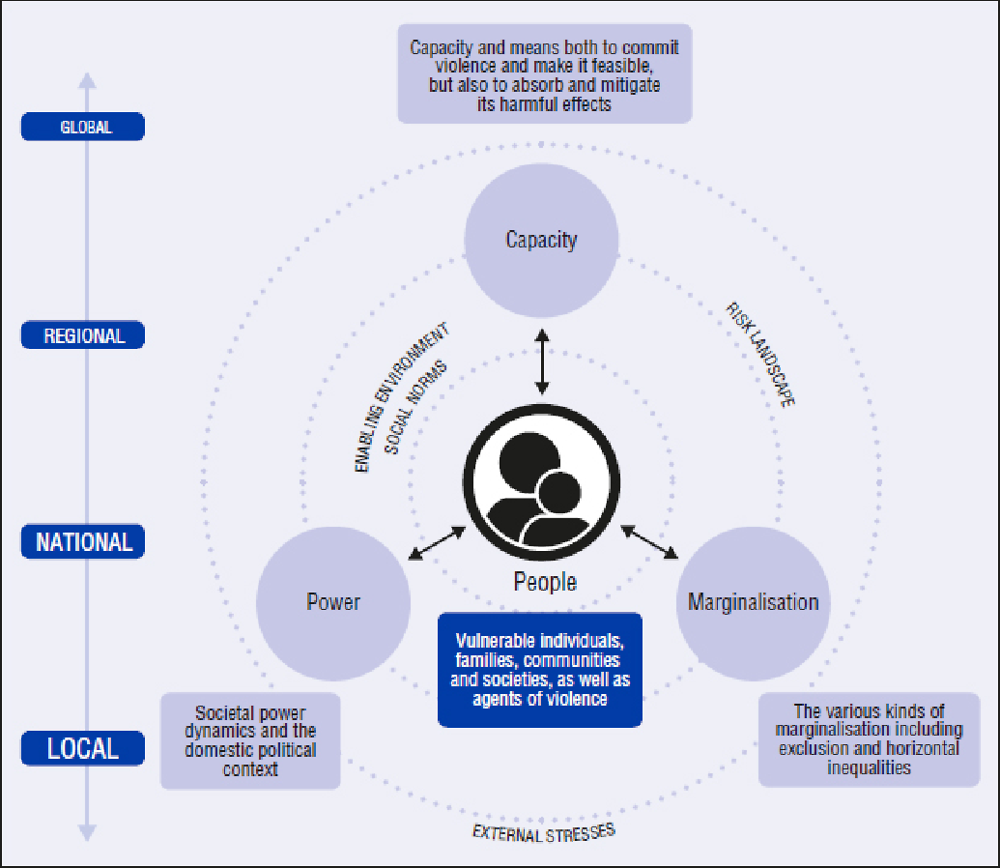

The updated violence lens (Figure 7.1) includes:

-

societal power dynamics and the domestic political context

-

the various kinds of marginalisation including exclusion and horizontal inequalities

-

the capacity and means both to commit violence and make it feasible, but also to absorb and mitigate its harmful effects.

A geographic dimension provides scope. But at the centre of the lens are people: the vulnerable individuals, families, communities and societies who bear the greatest consequences of violence, and are also the agents of violence. Together, these conditions for violence become a risk framework, which can act to detect and predict trends, and can offer clues for more effective prevention efforts.

Power

Much of the conflict and violence experienced today is a function of “competition” politics, corruption and poor state-society relationships. The sources of power within any given society can often be varied, and do not necessarily coexist harmoniously. The tensions between different sources of power, and among those who are excluded from the benefits of power, can be important drivers of violence. As outlined in Chapter 2, violence is increasingly fuelled by domestic political instability. The terms of access to power, including among elites and their proxies, often perpetuate risks of violence, even in countries and societies considered to be at peace. This competition can play out at regional, state and/or local level.

Power sharing and inclusion do not automatically eliminate or lessen these tensions and, in fact, can exacerbate them.

Marginalisation

Inequality and division deepen social cleavages and increase the propensity for violence. Socio-economic marginalisation derived from horizontal inequalities, uneven development and economic exclusion can lead to multiple forms of interpersonal, criminal and social violence as well as collective armed political violence. Power dynamics, as outlined above, can deepen the marginalisation of individuals and communities, creating a negative feedback loop of grievances that lasts for generations and leaves marginalised groups vulnerable to exploitation by political or criminal actors. Marginalisation can also play out in social violence, such as in North, South and Central America where there are higher rates of homicide and crime among disadvantaged communities (Hagedorn, 2008).

Other push and pull factors can trigger violence among marginalised communities. Several socio-economic factors can stoke violence – unemployment, poverty, clan/social/political marginalisation, corruption and youth frustration. Other factors can pull marginalised individuals towards violence – access to material resources, weapons and protection, a sense of belonging and empowerment, strong governance – leading to violent extremism and radicalisation (Glazzard et al., 2016). Urbanisation can also act as a trigger for violence by marginalised people (Østby, 2015; Raleigh, 2015). Urban economic development brings rural poor to cities, where they often live in slums. Research has shown that when this occurs, violence increases (Geneva Declaration Secretariat, 2011). The Sustainable Development Goal period will see huge demographic shifts that concentrate the world’s poorest people in urban areas, thereby creating hotspots of marginalised communities. The most populated cities in the world are also likely to be the most fragile as structural inequalities and social exclusion become more prevalent. The connection between violent conflict and horizontal inequalities is applicable to a variety of contexts and types of violence (Langer and Stewart, 2013; Brown and Langer, 2010), including communal violence (Mancini, 2005; Fjelde and Østby, 2014), inter-regional inequality and separatist conflict (Bakke and Wibbels, 2006); and group mobilisation in civil war (Langer, 2005).

Capacity

The feasibility of violence and conflict is an important determinant for their emergence. The availability of weapons and ammunition, and access to money through such means as natural resource exploitation and organised crime, do not in themselves cause violence. But they are risk factors that enable its emergence. Added to this, the capacity of groups to mobilise human and financial resources, logistics, and military capability also heighten the risk of armed violence.

People

The complexity of violence leads to dominant narratives that can impede understanding and the effectiveness of interventions.

Violence does not fit neatly into customary security frameworks or conflict narratives, and is often treated subjectively within different organisations. As mentioned in Chapter 2, approaches that reduce violence to “perpetrators versus victims” or “criminals versus innocent citizens” ignore how chronic violence actually pushes everyone affected into a complex violence situation. For instance, in societies that have been afflicted by violence for many years, victims can become perpetrators and perpetrators can become victims, demonstrating the shape-shifting nature of violence.

The tremendous versatility of violence to transform in changing circumstances and contexts, as well as the complexity of drivers and motivations for individual behaviour, make it tempting to homogenise actors and simplify programmatic responses. However, this can compound risks. Non-selective targeting or broad punitive measures can inadvertently sweep up non-violent individuals in their wake, or fail to account for social norms, motivations and other factors. As a result, they may deepen marginalisation, foster mistrust for the rule of law or provide motives for violent behaviour.

Power, marginalisation and capacity interact with one another – and with the normative environment in which they coexist – to form a risk context in which violence may emerge or subside. People in turn interact with the risk environment they find themselves in and may become perpetrators and/or victims of violence depending on the dynamics of these interrelationships. A full picture of the complexity of violence emerges only by closely analysing these interactions on multiple levels.

States of Fragility 2016 – final recommendations

By 2030, it is estimated that more than 60% of the global poor will be living in states of fragility. It is our collective goal to ensure that these people – those left furthest behind – are part of our shared tomorrow.

Given the breadth of States of Fragility 2016, it is impossible to provide an exhaustive list of specific recommendations. However, it is possible to highlight some areas where the development community can more effectively address fragility and violence. Good practice does exist; these examples need to be shared, discussed and improved upon. The following recommendations benefit from the valuable insights of the International Network on Conflict and Fragility (INCAF) and its members, as well as the wider community of practice.

BETTER POLICY

Recognise that fragility is multidimensional

States of Fragility 2016 recognises that fragility has many dimensions with many aspects and facets. These dimensions – both the exposure to different types of risks and the lack of capacity to absorb them or to adapt – can affect developing and richer countries alike. States and societies face an accumulation or combination of risks – and if that state, society or system cannot manage, absorb or mitigate the consequences of those risks, then it shows signs of fragility.

The OECD fragility framework has highlighted five dimensions of fragility: economic, environmental, political, security and societal. The resulting multidimensional model provides an important new framework to consider how fragility is framed and assess how it is monitored.

Recognising that fragility is multidimensional can help practitioners design better theories of change and programming in at-risk contexts. To start with, practitioners need to at the very least invest in a better, more holistic analysis of the context. In turn, a better analysis will help support better programme design, ensuring that programmes support the capacity of state and society systems to manage, absorb and mitigate potential risks across all the different dimensions of fragility. Using a multidimensional framework will also help different actors in a particular context understand how their individual actions and programmes are interdependent. If all the facets of fragility are to be addressed, different actors will need to plan, design and implement programmes in a more collaborative way.

Take violence seriously – in all its forms

More attention must be paid to the important impact of violence, in its many forms, on fragility.

States of Fragility 2016 reframes fragility as a combination of risks, with violence as perhaps its most frequent driver and its most frequent outcome. The report findings – that violence is increasing, it is complex and shape-shifting, and it is extremely costly – demonstrate that the international community needs to dedicate more resources and attention to this important area.

The treatment of violence must take into account the interconnected nature of different forms of violence, and their shared root causes. This will involve a shift in development practice – moving from interventions that are focused primarily on conflict and its aftermath to interventions that address violence, and its prevention, in all its forms. It will also require closer collaboration, at least at the analysis stage, between different policy communities working at different layers of society – especially between development, stabilisation and humanitarian actors.

Challenge existing paradigms

Dominant narratives about violence can oversimplify what are inherently complex multi-causal dynamics, leading to facile assumptions about how to most appropriately respond. This will entail adopting a broader definition of violence, one that explicitly avoids attributing labels of “good” and “bad” to populations and places, while also recognising the mutability of roles, actors and circumstances.

Conflict areas are not necessarily anarchic, disordered or ungoverned. Civilians are not just victims – they can also be active participants in, and enablers for, violent acts. Peace does not necessarily follow conflict. Domestic politics, even in times of peace, can also cause political violence.

In addition, not all development work has an impact on violence. The international community should thus better distinguish between programmes for broader development gains (e.g. education and jobs) that have potential long-term yields for violence prevention, on the one hand, and other targeted interventions that lead to more immediate, significant and measurable reductions in violence, on the other hand. Both are necessary in order to foster a context in which sustainable development can take hold, and in which societal norms evolve to eventually discourage violence. Indeed, the first step to better addressing violence is to frame it in a way that takes full account of its complexity.

Challenging the dominant paradigm opens entry points for interventions, and empowers people to change those roles, and norms, in positive ways.

Invest in prevention

Investing in prevention saves lives, resources and money. It is not only logical; it is simply more effective. A prevention culture must permeate all levels of aid planning and decision making, including investment in resolving the root causes of conflict.

An important determinant of success is early engagement in emerging crises; this is key to prevention and to the protection of civilians affected by violence and fragility. Both are cyclical in nature, and evidence shows that exposure to violence often leads to more violence down the line. Early intervention, focusing on changing behavioural and societal norms, is therefore essential to break this cycle of violence before it picks up unstoppable momentum (UNODC, 2013). Young people, with the most to lose and gain, are the key to realising these generational shifts.

Sustained and committed political diplomacy for prevention and resolution must also be part of a more comprehensive package of responses, dealing with the underlying factors that led to fragility and violence in the first place (UNOCHA, 2016).

Deliver on the Stockholm Declaration and the New Deal

The Stockholm Declaration outlines how to revive commitment to the New Deal for Engagement in Fragile States and take it the next level, so that the ambitions of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development can be realised in fragile and conflict affected environments (IDPS, 2016).

In Stockholm, the members of the International Dialogue on Peacebuilding and Statebuilding committed to: accelerate and improve their efforts to address the root causes of fragility and violence, using the New Deal’s Peacebuilding and Statebuilding Goals to guide their interventions; strengthen women’s active participation in the process; build stronger partnerships, including multi-stakeholder dialogue at country level, and with the humanitarian community; build effective structures for conflict management and reconciliation, and to make politics more inclusive; increase political and financial efforts, in line with the New Deal principles, to address the special needs of fragile contexts; strengthen national public financial management systems to reduce fiduciary risks; and to scale up programmes to support domestic resource mobilisation.

Making good on these Stockholm Declaration commitments, and being held to account for progress, will be an important task for the coming years.

Use domestic policy to promote global peace and security

Action against violence and fragility can also start at home. Domestic policies, if enacted with a violence and fragility lens, can make a real difference to the factors of power, marginalisation and capacity that enable violence around the world.

There are a number of ways this could be done. Transparency about the purchase and sale of resources, including oil and minerals, by domestic citizens and companies, could be improved. This would help limit the resulting flows to proponents of violence. Investing and trading with fragile contexts – providing predictable, long-term access to markets – could help promote economic growth, stability and jobs, and thus mitigate the incentives for violence. Shutting down tax havens and financial secrecy jurisdictions could create more tax resources in fragile contexts and promote a social contract between citizens and state. Tackling environmental issues at home, for example reducing deforestation and climate change, and protecting biodiversity, could help reduce the environmental factors that disproportionately impact fragile societies. Increasing economic opportunities for migrants from fragile contexts – for example through seasonal worker visas, and in areas where skills are in short supply such as care for the elderly – would increase the flow of remittances, spread democratic ideas and values, and also provide value for domestic economies. Other global norms and values can also be promoted – for example through rules regarding landmines and small arms, war crimes and against the use of torture; arms sales, protecting freedom of the press and the rights of minorities; and furthering the fight against corruption (Barder, 2016).

BETTER PROGRAMMING

Develop a whole-of-society approach

Positive and sustainable outcomes in fragile contexts depend on multiple and interconnected factors. Focusing on a single actor, or a single layer of society, or a single sector, will therefore be insufficient. Instead, better results will come from working with multiple types of actors, at different layers of society – individual, community, municipal, provincial and national – and taking a multidimensional, multi-sector approach. In this way the capacities of whole societies to respond to volatile, risky and rapidly evolving contexts will be strengthened. Like other development efforts, multi-year financing that allows for longer-term strategic theories of change will go a long way to facilitating this work. Additionally, investing in context and problem analysis as core donor behaviour will help ensure this targeting is systematically used and is based on the best available evidence (OECD, 2016).

Likewise, the teams and disciplines tackling the many dimensions of violence and fragility must be as diverse and robust as the challenges they face. Better collaboration among those engaged in tackling social, criminal and interpersonal violence and those working on the issues of conflict, peace and security will provide valuable synergies. Such cross-fertilisation can draw on an immense evidence base of global experience connecting different approaches and streams of violence programming.

One important lesson is that effective policies and strategies must not only target at-risk young people, but also promote young people and local communities working together to break the cycle of violence (UNODC, 2013). Community mobilisation programmes, when combined with support services and media outreach, have had success in changing social norms in high-violence areas, as evidenced by greater reporting of violence and reduced impunity (WHO, 2016).

This type of multidimensional, systems-based approach starts with whole-of-society analysis and planning, resulting in shared strategic goals and more coherent programming and results.

Put people at the centre

Agenda 2030, and its theme to “leave no one behind”, aims to ensure that marginalised, excluded and vulnerable groups are prioritised. A focus on violence in all its forms also means shifting towards an approach that puts people at its centre, recognising that a stable state and strong institutions do not automatically lead to a reduction in violence. Instead, focusing on those individuals most likely to engage in violence can be a better strategy, one that positively influences social norms and behaviour change. Once such example is focused deterrence, which places high-risk people at the centre, and uses strategies such as direct communication of community standards against violence, prior notice from law enforcement about the legal consequences of further violence, and a tailored offer of help (Locke, 2016). However, a more focused approach requires a great deal of care, and a strong understanding of how individuals and communities perceive issues such as legitimacy, trust and the existing provisions of security, and it therefore will be highly context-specific.

In practice, however, structural responses to fragility tend to be favoured over societal ones. This is because they are more visible, easier to manage and measure, and may yield more immediate results. However, development actors who favour central capacity building must recognise that the state is often a non-neutral actor and that enhanced state capacity could – perversely – also increase economic exclusion, and increase marginalisation and

insecurity. For example, where strong law enforcement is not accompanied by commensurate social investments, communities may feel persecuted and even empathise with criminals. In addition, a more sophisticated approach to engagement with elites is needed, as they can have vested interests in perpetuating fragility. Investing in community capacity and mobilisation can help counter these effects.

Indeed, local actors have the knowledge and legitimacy to handle sensitivities, and are best positioned to address societal violence where they too see that as a priority. In fragile contexts where risks of violence are greater, involving local actors in the programming cycle will ensure that assessments, planning, data collection and research, and evaluation reflect their particular needs.

Use the violence lens to design and deliver programming

States of Fragility 2016 proposes an updated violence lens to help practitioners better understand the drivers of violence in all its forms (Figure 7.1).

The violence lens shows that power, marginalisation and capacity interact with each other to create an environment that either leads to or, in its positive form, reduces, violence. People interact with that environment to become perpetrators or victims of violence, or both.

Using the updated violence lens to help analyse contexts, and deliver and monitor results, will help foster a greater understanding of violence in societies, design better programmes that either directly or indirectly reduce the drivers of violence, and thus deliver more effective results.

The OECD will further develop the violence lens, as well as guidance on its use, over the coming year.

Prioritise reconciliation

Dialogue and reconciliation in post-conflict societies, with the support and commitment of the international community, can help support sustainable peace. For example, the g7+ is using fragile-to-fragile co-operation to share experiences of transitions to peace by supporting dialogue and reconciliation. It has established Councils of Eminent Persons to promote dialogue.

Reconciliation is a critical part of healing the social cleavages that perpetuate and exacerbate violence, and can therefore help reduce a key driver of fragility. Without addressing these social cleavages the root causes of violence will remain, ready to flare up again at any moment, or embed grievances and inequalities. However, the international community has difficulty funding reconciliation programmes. Results are hard to capture and prove, and programmes take a long time, meaning that the case for reconciliation can be difficult to make in project proposals, especially for programmes at the community level where reconciliation is arguably most needed. In addition, given the unpredictability of human behaviour and the complex incentives involved in violent and fragile environments, reconciliation programmes cannot be guaranteed to work for everyone. However, when reconciliation is effective, it can have a multiplier effect on other development programming in fragile environments and enable a more inclusive peace, especially in contexts that are experiencing severe violence and mistrust – including contexts that are feeding the fires of violent extremism.

Therefore, more sustained international support for reconciliation processes, and integration of reconciliation into peacebuilding programming, would be useful.

Recognise the critical role of gender in addressing fragility

OECD research on gender and fragility shows that international support in areas such as gender reforms or women’s participation will have limited impact when powerful societal norms and structures are left unaddressed. While discriminatory norms can be particularly harmful in fragile contexts, opportunities to shift such norms do exist in fragile and post-conflict contexts (OECD, forthcoming). Programming in fragile contexts therefore needs to go beyond a focus on reform and strengthening of formal institutions. It should also recognise the importance of informal power structures and institutions, social norms, and behaviours in shaping both gender inequality and their follow-on impacts on states of fragility. However, at present, development actors often analyse gender and fragility in separate processes, and fail to link their findings.

Therefore, one way to help achieve a more cohesive approach would be to develop tools that bring together gender, violence and fragility issues within one analytical framework.

Experiment, remain flexible and take risks

People are at the centre of violence-related threats and solutions – and yet human behaviour is often difficult to foresee and anticipate. Therefore, programming to address violence, and the budgets that support it, will need to remain flexible enough to allow programmes to be adapted or dropped if they are not working, and/or to be scaled up when showing signs of success (OECD, 2016, 2012; European Commission, 2015). Becoming comfortable with a measure of well-calculated risk, and even programming failure, can have big payoffs. This includes learning from, rather than penalising, failure as well as incentivising innovation and marginal risk acceptance.

A strategy with high potential for success and, often, cost savings is one that emphasises learning by doing; piloting and incubating various experimental approaches; monitoring and collecting feedback; and growing an evidence base and then gradually scaling up. Courageous leadership is also important, helping leverage multi-sector investments and draw on shared resources, including strategic partnerships with the private sector (World Economic Forum, 2016). Lessons from the Latin American “citizen security” model are relevant here. First, a clear strategy is critical. Second, these interventions are successful when they are tightly focused on high-risk places and behaviours, and set short- and long-term horizons (Abt and Winship, 2016; Muggah et al., 2016).

Learn and build the evidence base

Investments to counter fragility must be built on a foundation of both qualitative and quantitative evidence and real data, rather than assumptions (OECD, 2011). Surprisingly, this is not the case today. A recent study for the World Economic Forum, for example, concludes that fewer than 6% of public security and justice measures undertaken across Latin America and the Caribbean have any evidentiary base (Szabó de Carvalho and Muggah, 2016). A broad foundation is required: analyses should include information related to individuals, organisational dynamics and local political economies. Much of this is difficult to measure, and thus understand, because rates of reporting non-lethal violence are low. Better outreach to produce and use such data – particularly at the local level – would help fill these critical gaps. It is important to find and test innovative approaches to understanding the drivers of violence, and how to respond to violence, despite the data gaps. Because violence cuts across a broad spectrum of fields and institutions, key data for measuring trends and dynamics tend to remain inside professional silos. This disaggregation means it is difficult to ascertain the complex ways in which violence drives and contributes to fragility. A common database allowing for information sharing on the range of violence related to fragility could be considered a public good (OECD, 2016). Furthermore, there may be more effective ways to gather data using existing tools, if international donors are willing to be flexible and innovative. Even well-known technology, like geographic information systems (GIS), can be leveraged in new ways, such as for geo-referenced violence “hot spots”. Qualitative measures like perception-based surveys are also becoming common and could be repurposed to reflect the violence-fragility nexus. Strategic partnerships should therefore be built on an interdisciplinary approach that utilises the full range of tools available, and does not limit fragility to a single field of study.

In addition, where impacts and/or causes are comparable, lessons and methodologies from other fields (e.g. rule of law, social violence, criminal and behavioural science, health, and anthropology) can be useful references.

FINANCING

Provide adequate, long-term ODA financing

States of Fragility 2016 highlights the continued importance of ODA in fragile contexts. ODA remains a growing, stable flow that complements private sector investments, which are often highly volatile and concentrated in only a few fragile contexts, as well as remittances, which are difficult to channel to specific development programmes because they are flows to friends and families. The report also shows that fragile contexts are often more aid-dependant than other developing countries.

However, States of Fragility 2016 also demonstrates that in many cases ODA supports immediate or short-term remedies but not measures that require a longer time frame. This is as true for development ODA as it is for humanitarian aid. If ODA is to be most useful, it will need to be sufficiently predictable, flexible and long-term to enable multi-annual responses that address underlying drivers of fragility – across all its dimensions. Strategic patience is required for sustainable results in fragile contexts.

Fund the real drivers of fragility

States of Fragility 2016 shows there is at best limited correlation between the main risks of fragility in a given context and funding to help that context build resilience to those risks. For example, contexts that are fragile in the economic dimension currently receive more ODA for crisis management than for strengthening their underlying economic structures, and therefore resilience. Similarly, higher exposure to political fragility does not necessarily correspond to greater ODA flows for building government and civil society capacity, although this could help to strengthen institutions and improve state-society relations.

While the OECD’s fragility framework should not be seen as a resource to help make programming decisions on the ground, this lack of correlation between the dimensions of fragility and the direction of funding is a cause for concern. It is important that thorough, systemic analyses of risk and capacity are undertaken in fragile contexts, and that funding allocations target the highest risks, across all layers of society (OECD, 2014).

Develop better financing strategies

The availability of sufficient, appropriate financial resources will be critical to addressing the root causes and drivers of violence and fragility, and to deliver Agenda 2030 in fragile contexts. In order to meet these ambitious goals, development actors will need to seek greater efficiency and impact from their existing financial resources and tools.

This new efficiency will necessarily take place in a dynamic and evolving international financing environment. Traditional international financial tools including ODA are increasingly called on to engage with a more diverse cast of actors and meet a wider range of ambitions than ever before – to catalyse technical solutions, influence policy, invest in new capabilities, underwrite public goods, incentivise and leverage investment, and stimulate financing flows from other public and private sources in support of better results in fragile contexts. In addition, the economic, environmental, political, security and social effects of fragility have shifted into new environments, notably towards middle-income countries, and are also increasingly understood as having country, regional and global impacts and solutions. The international community’s existing toolbox of financing instruments is under pressure to adapt to this new reality (OECD, forthcoming).

The ambitious new global development goals, dynamic and emerging states of fragility, and calls for more suitable financing mechanisms, present challenges for the international community. Development actors will need to gain a broader understanding of the development financing landscape for fragile contexts and address gaps in their financing toolbox. They will also need to better prioritise, quantify, sequence and layer different types of financial tools, and develop more coherent and forward-looking financing strategies for fragile contexts.

The OECD will continue work to promote a better understanding of financial tools and portfolio management in fragile contexts in 2017.

Conclusion

The stakes have never been higher. Violence and fragility wreak destruction on human lives and societies, preventing people from fully achieving their potential. Violence obstructs development, stalls recovery from conflict, compounds the risks of fragility, and feeds devastating new cycles of violence. The international policy response to violence must recognise the varied risks, impacts and causes. Unless the international community rises to this challenge – adapting traditional approaches where feasible, embracing risk, testing innovative models, working across boundaries and disciplines, and building evidence – then the trend of ever more costly violence will continue. Indeed, this fragile world could become more so in an exponential way, given that it will likely face more stresses from climate change, fragile cities, and the regionalisation of violence and conflict. Getting it wrong will not just leave the unsatisfactory status quo in place. It could well make matters worse. This opportunity to alleviate the toll of violence and fragility must not be missed.

References

Abt, T. and C. Winship (2016), What Works in Reducing Community Violence: A Meta-Review and Field Study for the Northern Triangle, USAID, Washington, DC, www.usaid.gov/sites/default/files/USAID-2016-What-Works-in-Reducing-Community-Violence-Final-Report.pdf.

Bakke, K.M. and E. Wibbels (2006), “Diversity, disparity, and civil conflict in federal states”, World Politics, Vol. 59/1, pp. 1-50.

Barder, O. (2016), “Give us the courage to change the things we can”, Center for Global Development blog, 6 October 2016, www.cgdev.org/blog/give-us-courage-change-things-we-can.

Brown, G.K. and A. Langer (2010), “Horizontal inequality and conflict: A critical review and research agenda”, Conflict, Security & Development, Vol. 10/1, pp. 27-55.

European Commission (2015), STRIVE for Development: Strengthening Resilience to Violence and Extremism, International Cooperation and Development, Luxembourg, https://ec.europa.eu/europeaid/sites/devco/files/strive-brochure-20150617_en.pdf.

Fjelde, H. and G. Østby (2014), “Socioeconomic inequality and communal conflict: A disaggregated analysis of sub-Saharan Africa, 1990–2008”, International Interactions, Vol. 40/5, pp. 737-762.

Geneva Declaration Secretariat (2011), Global Burden of Armed Violence 2011: Lethal Encounters, Geneva, www.genevadeclaration.org/measurability/global-burden-of-armed-violence/global-burden-of-armed-violence-2011.html.

Glazzard, A. et al. (2016), “Conflict and countering Islamist violent extremism”, Summary paper, Royal United Services Institute (RUSI) for the UK Department for International Development, London, www.gov.uk/dfid-research-outputs/conflict-and-countering-violent-extremism-summary-paper.

Hagedorn, J. (2008), A World of Gangs: Armed Young Men and Gangsta Culture, University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis.

IDPS (2016), Stockholm Declaration on Addressing Fragility and Building Peace in a Changing World, declaration signed on 5 April 2016, International Dialogue on Peacebuilding and Statebuilding.

Langer, A. (2005), “Horizontal inequalities and violent group mobilisation in Côte d’Ivoire”, Oxford Development Studies, Vol.33/1, pp. 25-45.

Langer, A. and F. Stewart (2013), “Horizontal inequalities and violent conflict: Conceptual and empirical linkages”, Working Paper, No. 14, Centre for Research on Peace and Development, Leuven, Belgium, https://soc.kuleuven.be/web/files/12/80/wp14.pdf.

Locke, R. (2016), “Violence can be prevented”, Center on Media Crime and Justice, John Jay College, New York, 10 October 2016, http://thecrimereport.org/2016/10/10/violence-can-be-prevented.

Mancini, L. (2005), “Horizontal inequality and communal violence: Evidence from Indonesian districts”, CRISE Working Paper, No. 22, Centre for Research on Inequality, Human Security and Ethnicity, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/57a08c6ded915d3cfd0013aa/wp22.pdf.

Muggah, R. et al. (2016), “‘Making cities safer: Citizen security innovations from Latin America”, Strategic Paper, No. 20, Igarapé Institute, Rio de Janeiro, https://igarape.org.br/en/making-cities-safer.

OECD (forthcoming), Better Financing for Fragility (working title), OECD Publishing, Paris, to be released in January 2017.

OECD (2016), “Good development support in fragile, at-risk and crisis-affected contexts”, OECD Development Policy Papers, No. 4, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/5jm0v3s71fs5-en.

OECD (2014), “Guidelines for resilience systems analysis: How to analyse risk and build a roadmap to resilience”, OECD, Paris, www.oecd.org/dac/Resilience%20Systems%20Analysis%20FINAL.pdf.

OECD (2012), International Support to Post-Conflict Transition: Rethinking Policy, Changing Practice, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264168336-en.

OECD (2011), “Breaking cycles of violence: Key issues in armed violence reduction”, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://www.oecd.org/governance/governance-peace/conflictfragilityandresilience/docs/48913388.pdf.

OECD (2009), Armed Violence Reduction: Enabling Development, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264060173-en.

Østby G. (2015), “Rural–urban migration, inequality and urban social disorder: Evidence from African and Asian cities”, Conflict Management and Peace Science, Vol. 1/25.

Raleigh, C. (2015), “Urban violence patterns across African states”, International Studies Review, Vol. 17/1.

Szabó de Carvalho, I. and R. Muggah (2016), “Latin America’s cities: Unequal, dangerous and fragile. But that can change”, World Economic Forum, 13 June 2016, www.weforum.org/agenda/2016/06/latin-america-s-cities-unequal-dangerous-and-fragile-but-that-can-change.

UN (2015), High-Level General Assembly Thematic Debate Promoting Tolerance and Reconciliation: Fostering Peaceful, Inclusive Societies and Countering Violent Extremism, United Nations Headquarters, New York, 21-22 April 2015, www.un.org/pga/wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2015/06/170615_HLTD-Promoting-Tolerance-Reconciliation-Summary.pdf.

UNOCHA (2016), Chair’s Summary, World Humanitarian Summit, 23-24 May 2016, www.unocha.org/about-us/world-humanitarian-summit.

UNODC (2013), Global Study on Homicide 2013: Trends, Contexts, Data, Global Study on Homicide 2013: Trends, Contexts, Data, United Nations Office for Drugs and Crime, unodc.org/documents/gsh/pdfs/2014_GLOBAL_HOMICIDE_BOOK_web.pdf.

WHO (2016), INSPIRE: Seven Strategies for Reducing Violence against Children, World Health Organization, Geneva, www.unodc.org/documents/justice-and-prison-reform/who---inspire_-seven-strategies-for-ending-violence-against-children.pdf.

World Economic Forum (2016), Responsible Investment in Fragile Contexts, Global Agenda Council on Fragility, Violence & Conflict, World Economic Forum, Geneva, https://igarape.org.br/wp-content/ uploads/2016/05/GAC16_Responsible_Investment_Fragile_Context.pdf.