Chapter 4. Targeting young people – work-based training at the local level in Germany

This chapter investigates the opportunities for work-based training for young people in the context of the dual vocational education system of Germany. The transition from school to work for young Germans is smoothed by a strong apprenticeship system and mechanisms that target government and employment services to young people at risk or with low qualifications. Specific examples of employer engagement in youth employment initiatives are also explored.

Key findings

-

Germany has a long history of vocational education, and vocational education pathways are seen as of equal or greater standing than traditional academic routes. The German vocational education system is characterised by its “dual” nature, which features a combination of “on-the-job” training in an enterprise and theoretical training with a local training provider.

-

Young people in Germany have the ability to transition into the world of work through a number of diverse pathways. Young people who choose to pursue apprenticeships through the dual vocational system can use them as a means to transition into high quality and desirable employment.

-

The German employment authorities have pursued a number of new initiatives to improve the integration of young people into the labour market. These range from improved matching of apprentices for small and medium-sized enterprises to improving access to introductory work-based training opportunities.

-

While the system is diverse and complex, and involves an array of programmes that occur at both the national, regional and local level, some concerns remain about the flexibility of the system to adapt to circumstances at the local level. There are also concerns about potential path dependency associated with pursuing vocational education pathways.

Introduction

The German technical and vocational education and training (TVET) system is one of the most developed in the world. Germany has a long history of vocational education and work-based training programmes as a pathway to high quality employment in a range of occupations. This is partially due to strong institutional support from employers, who provide relatively more training places than employers in other countries. Employers also enjoy a number of opportunities to contribute to the design and delivery of TVET policies at the national, regional and local levels.

Young people in Germany have a diverse array of options when transitioning from compulsory education to the world of work. This report explores some of these pathways through the lens of work-based training opportunities available through the vocational education system. It investigates a variety of initiatives from government actors, employment agencies at both the national and federal state level and employer groups.

Policy context

After fulfilling compulsory schooling, young people can work, undertake an apprenticeship or tertiary education or some mixture of these activities. In Germany, the tertiary education system can be separated into classical universities and universities of applied sciences (“Fachhochschule”). Classical universities cover a range of academic disciplines and features theoretical and research-oriented education. In contrast, teaching at the “Fachhochschule” is usually more practical and work-oriented. There are also co-operative study programmes (“Duales Studium”), which combine practical studies at university with on‐the-job training at private companies. Dual education students are primarily employees with fixed-term contracts who also receive regular social insurance payments.

Outside of the different types of universities, young people in Germany can enter the dual vocational education system (“Duales Ausbildungssystem”) and begin an apprenticeship after leaving school. Within the OECD, Germany has one of the largest shares of young people in upper secondary education pursuing dual vocational training (OECD, 2015).

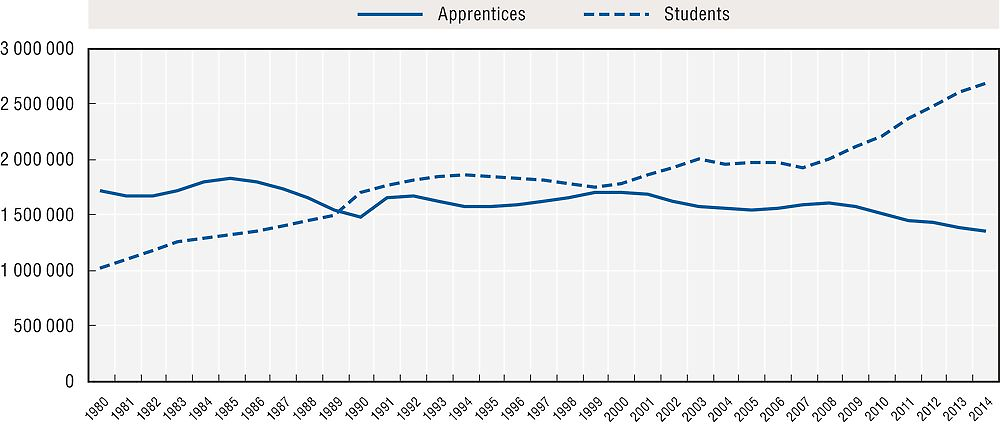

The dual vocational training system has a long history in Germany and many professions that require a college degree in other countries can be pursued after completing an apprenticeship, such as occupations in the fields of nursing or physiotherapy. Thus, there has been a relatively large share of apprentices in Germany in the past, although an increasing share of young people have pursued tertiary education over the last 30 years. Trends in the number of apprentices and university students in Germany since 1980 are illustrated in Figure 4.1.

Source: Statistisches Bundesamt (2015).

The increasing numbers in tertiary education reflects expanded access to universities. In recent decades, the freedom to choose between educational paths has vastly increased. In the past, tertiary education was predominantly reserved for a small fraction of students who graduated from the most advanced level of secondary education. Nowadays universities and universities of applied sciences are more accessible for the majority of youth, which reflects the German political desire to increase the levels of skilled workers in Germany.

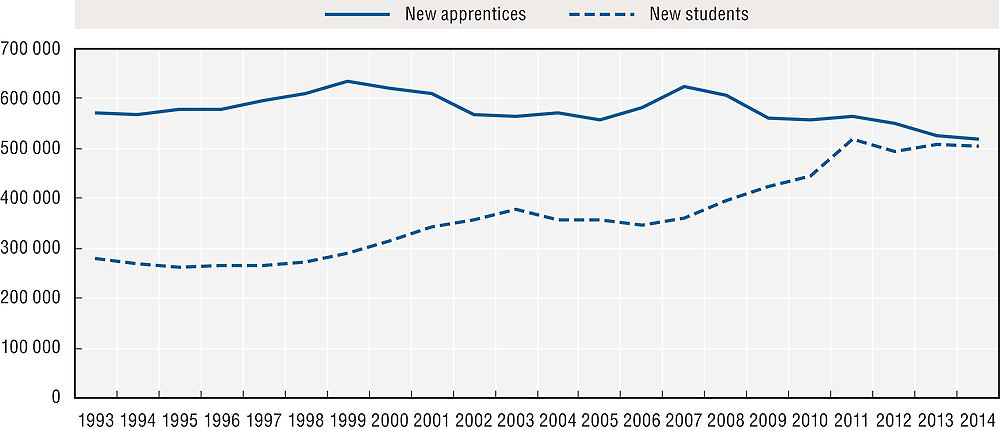

Figure 4.2 shows the converging trends in enrolments in apprenticeships and tertiary education. The abolition of compulsory military service and the shortening of the “Abitur” (the final secondary school exam) in some federal states have also contributed to the strong recent rise in new tertiary students. At present, the number of new students and new apprentices are almost equal, which is remarkable in the context of the last 20 years (see Figure 4.2).

Source: Statistisches Bundesamt (2015).

Overview of the German apprenticeship system

The German training system is considered “dual” because it combines both practical on-the-job training with theoretical education in vocational schools (“Berufsschule”). The duration of the apprenticeship typically varies between two and three-and-a-half years, depending on the profession. There is no formal requirement for starting an apprenticeship, although most training facilities require a secondary school leaving certificate from a secondary education school. A better certificate can improve the chances of successfully gaining an apprenticeship and can also reduce the duration of the apprenticeship. For example, the “Abitur”, the highest leaving certificate, shortens an apprenticeship by up to a year. After completing the training, apprentices receive certification that outlines the skills acquired, an evaluation of performance throughout the apprenticeship and the vocational school.

Apprentices receive monetary compensation throughout the job training, which increases every year. The vocational training pay varies substantially across professions as well as between German regions. For example, a West German construction mechanic receives 879 Euros per month in their first year while a West German first year apprentice in the hairdressing sector will only receive 374 Euros per month (BIBB, 2014a). Similarly, the average payment in West Germany is 767 Euros per month, but only 708 Euros per month in East Germany (BIBB, 2014b). As the compensation in many occupational fields is exceeded by living expenses, there are additional vocational training grants available from the German Federal Employment Agency, depending on the apprentice’s living situation. These grants vary depending on the apprentice’s living circumstances, rent, parents’ income and apprenticeship payments.

Apprentices typically spend three to four days per week at a training facility to gain work experience and acquire practical job-relevant skills. The training facility will typically offer resources and guidance to the apprentice. Apprentices can also choose to attend vocational schools on a part-time basis, for either one or two days a week or in blocs of several weeks. The vocational school is compulsory for apprentices younger than 21 years, while older apprentices are not obliged but retain the right to regularly attend vocational school. The subjects in the vocational schools include job-specific studies like technical and medical courses as well as general education in subjects like German and politics. The Chambers of Industry and Commerce (Industrie- und Handels-kammer, “IHK”) are responsible for monitoring the quality of the apprenticeship in the training facilities and establishing guidelines. This guarantees that the successful completion of the apprenticeship will be recognised throughout Germany, which enables graduates to move between regions.

The dual vocational training system is based on the voluntary involvement of the employers. There is no specific obligation for employers to train students, nor is the system heavily subsidised by the government. Employers choose to opt into the vocational training system because it is viewed as a major investment in their future workers. This attitude has a long tradition in Germany as well as its neighbouring countries. In general, employers view vocational training as an opportunity to train young people according to their business needs.

Three legal documents (Berufsbildungsgesetz, Handwerksordnung and Jugendarbeitsschutzgesetz) administer the eligibility of employers and training companies to offer vocational training. Under these laws, over half of German employers are eligible to offer apprenticeships. Since 2000, around 50% of eligible employers have participated in the vocational education system. The participation rate of eligible employers is positively correlated with the size of the workforce of the enterprise.

The content of the training is determined by vocational training regulations that are approved by the Federal Ministry for Labour and Social Affairs with advice from the Federal Institute for Vocational Education and Training. Social partners and employers may also propose changes to these regulations or even the introduction of completely new training occupations. Through this mechanism, local stakeholders are able to influence the development of vocational training curricula. The training regulations define the name of the apprenticeship and its duration. The regulations also include the minimum skills and proficiencies to be developed, as well as a time schedule for teaching and the examination requirements of the apprenticeship.

The nature of the apprenticeship can differ widely. Training facilities provide training in approximately 400 different professions, ranging from administrative positions such as bank clerks to technical positions such as dental technicians and carpenters. Besides companies in the industrial, commercial, trading and agricultural sectors, it is also possible to complete an apprenticeship with administrative authorities and freelance professionals like physicians and lawyers.

There were 1.35 million apprentices in Germany in 2014, and approximately 500 000 sign new training contracts each year. In 2014, the most popular apprenticeship was an office clerk role, 75 000 apprentice positions, 75% of whom were female. 62% of all apprentices were male (see Table 4.1), but the nature of apprenticeships varies between the genders. On average, male apprentices favour more technical positions while female apprentices tend to take apprenticeships in medical and commercial roles. For example, while there are almost 61 000 German motor vehicle mechatronics apprentices, only about 2 000 of them are female. In contrast, over 37 000 women take apprentice positions as medical assistants in comparison to just 550 men (Statistisches Bundesamt, 2015).

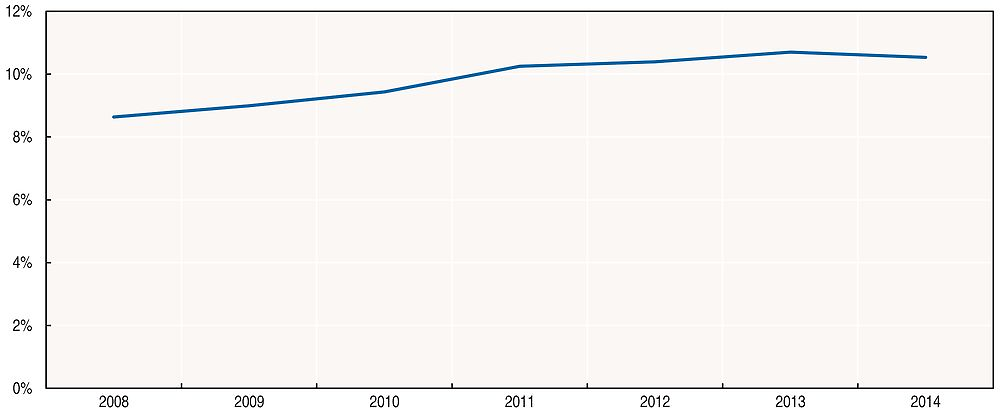

Figure 4.3 shows a relatively constant trend in apprenticeship drop-outs until 2010, when the rate increases despite a strong decline in the stock of apprentices. The nature of the education before the apprenticeship appears to be a factor in completion rates. In 2012, 34.6% of apprentices with a secondary school leaving certificate from lower secondary education providers (“Hauptschule”) did not complete their apprenticeship and training programme. In contrast, only 13.4% of apprentices with a higher standard of secondary education (“Abitur”) terminated their training without a certificate (Statistisches Bundesamt, 2013). The increase in drop-out rates may also be driven by increased freedom to choose between educational paths, as those who fail to complete their apprenticeships are able to more easily apply for other forms of education.

Source: Statistisches Bundesamt (2015).

Work-based training programmes in Germany – The role of active labour market policies

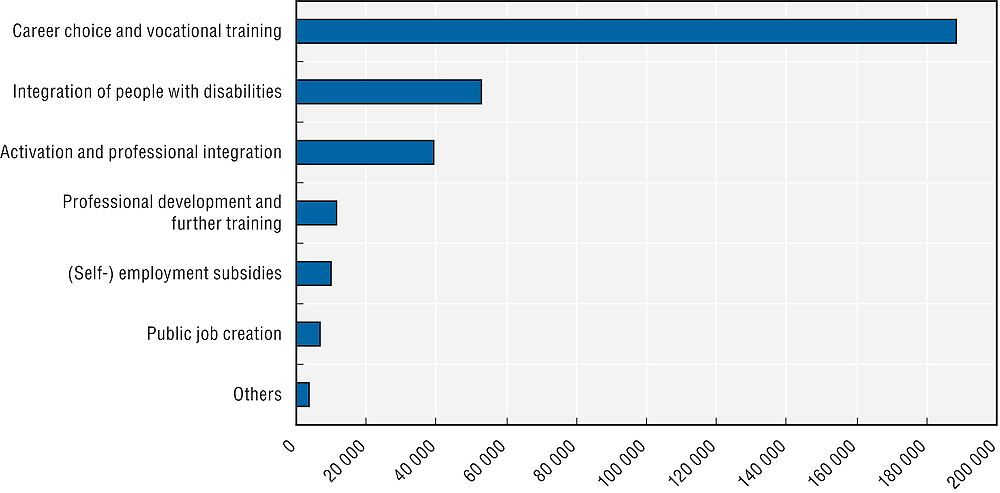

In 2013, the German Federal Employment Agency (“Bundesagentur für Arbeit”, BA) had a budget of 1.5 billion euros for active labour market policies (ALMP), many of which feature work-based training programmes. Of these, almost EUR 300 million was spent on measures targeted towards young people (BA, 2014a). In each month of 2014, over 300 000 young people took part in ALMP (BA, 2014b). In addition to targeted ALMP, young people are able to take part in general services provided by public employment services, including computer software training, foreign language courses and general job application training. In June 2014, over 39 000 participants aged below 25 years participated in publically funded training programmes (BA, 2014b).

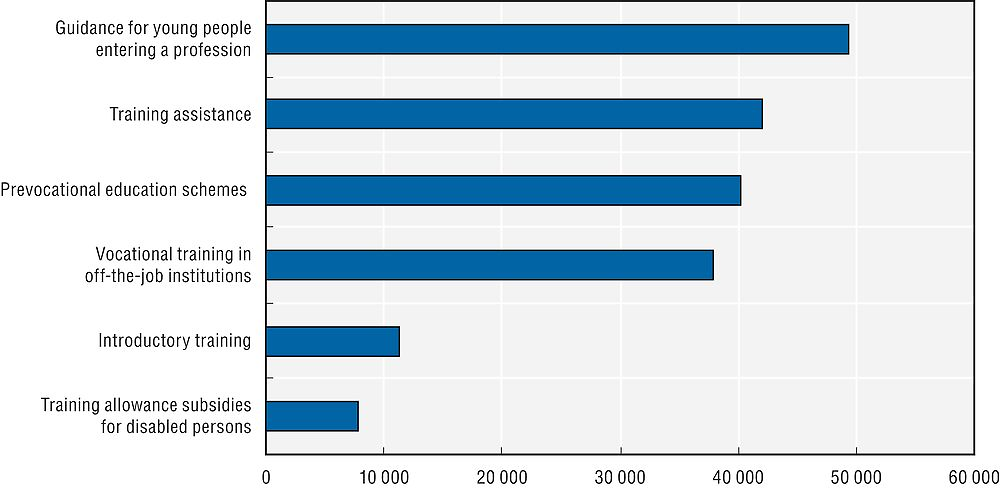

Figure 4.4 summarises and illustrates the policies that target German jobseekers below the age of 25. The overwhelming majority of youths (188 000) who receive in employment services participate in programmes that offer career guidance and vocational training. For example, over 49 000 persons participated in programmes that provide guidance for young people entering a profession (“Berufseinstiegsbegleitung”) and a further 11 000 participated introductory training courses (“Einstiegsqualifizierung”) (see Figure 4.5).

Source: Federal Employment Agency (2014a).

Source: Federal Employment Agency (2014a).

Over the last few years, the number of unoccupied positions and unplaced applicants for apprenticeships has increased due to spatial and occupational mismatch. In response, the BA introduced the “Berufliche Ausbildung hat Vorfahrt” initiative in 2014 which features a campaign that encourages employers to provide apprenticeships to disadvantaged young people. The initiative also targets policymakers to increase access to training assistance, arguing that measures that support vocational training (“Ausbildungsbegleitende Hilfe”, ABH) should be offered to all jobseekers in order to prevent breaks in vocational training. These measures include exam preparation assistance, private tuition in German, counselling or mediation between apprentices, teachers and parents. The BA’s initiative aims to further co-operation between employers and vocational training institutions and promote additional external training for regions with a high level of skills mismatch.

Some ALMP are designed to improve skills match between aspiring apprentices and employers, thereby improving apprenticeship outcomes while also broadening access to the system. Others attempt to improve the employability and skills among young people through work-based training. Some of these initiatives are discussed further below.

Customised apprenticeship placement services for SMEs

In 2007, the Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Energy (BMWi) introduced a new programme to improve the placement of trainees in enterprises (PV). The aim of the programme was to ensure that small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), particularly those in the craft and services sector, were able to obtain suitable talent for dual vocational training. Without support from third parties, SMEs have more difficulty attracting apprenticeship candidates in comparison to the public sector or large enterprises.

The programme provides funding to agencies that assist the placement of apprentices into suitable positions. These agencies are typically not-for-profit organisations who aim to find placements for enterprises and intermediate agencies that provide assistance to SMEs. There are a number of intermediate training placement companies and chambers of commerce who are supported by the PV placement programme in order to help SMEs recruit suitable trainees.

PV agencies and implementation of the PV programme

In Germany, it is the norm for businesses seeking apprentices to liaise with third party placement organisations to find a suitable apprentice. PV placement is the only significant alternative to the mediation services offered by the Federal Employment Agency. Very few companies (< 5%) seeking apprentices negotiate private arrangements with potential trainees.

The PV services are provided by a range of not-for-profit organisations, including chambers of commerce, chambers of craft, chambers of liberal professions and other business organisations, which tend to offer more personalised services to SMEs than alternative services offered by the Federal Employment Agency, job advertisements and internet portals.

The model of implementation varies, but these organisations generally work closely with local SMEs to determine their particular skills needs. They also recruit aspiring apprentices from local technical education schools and recruitment events, such as career fairs, and assess their training needs, wishes and living conditions. The PV agencies also typically arrange the initial interaction between employers and apprentices.

Since a preliminary study in 2008-09 funded by the BMWi (Salman and Vock, 2009), the PV programme has expanded both its scale, in terms of funding, number of beneficiaries and reach. In response, the number of PV agencies that receive funding has risen from 70 in 2011 to 105 in 2013. These organisations provided counselling, possible workplace-related training and placement assistance in 159 continuously manned offices throughout Germany.

Employers and PV agencies

There is also a pool of trainees who use PV services to find apprenticeships, with each organisation averaging 250 to 700 “informational interviews” to interested candidates throughout 2014. There is also a large number of known and potentially interested companies that offer training places for trainees and apprentices. The PV agencies in the commercial and industrial chambers have the largest pool of companies who are willing to host an apprenticeship, usually between 2 000 and 3 000 enterprises. These organisations are also often responsible for vocational training within their field and are aware of placement opportunities. They also typically maintain databases of the nature and requirements of their member enterprises.

However, the pool of places is significantly smaller among PV organisations that are not affiliated with a particular commercial or craft chamber. The PV projects of major chamber organisations such as the trade and industrial chambers typically offer an average of 100 to 250 apprenticeship places per year. The PV projects of craft-related organisations, other business organisations as well as the chamber of liberal professions do not typically deliver the same number of apprenticeship places.

Outcomes

From 2010 to 2013, participants in the PV service seeking apprenticeships were approximately 60% male and 40% female. Around 90% were under the age of 25, and just 11% were under the age of 15. Around 45% of those advised were students from general schools, while more than half had already left school. PV counsels a relatively small proportion of A‐level students (10%). The majority of participants who sought apprenticeship placement assistance were youths from lower secondary education and middle school. Around one-quarter were from an immigrant background.

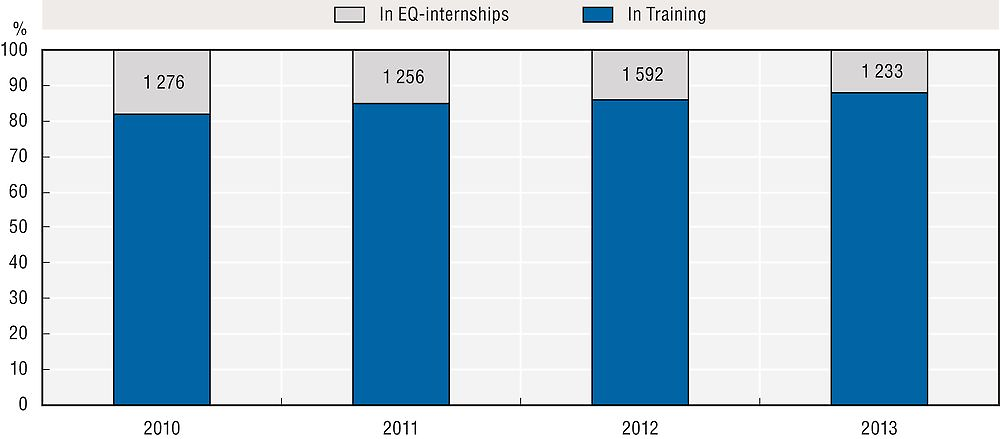

According to the PV placement statistics, thousands of apprenticeships are placed through the PV programme (see Figure 4.6). In 2010, 5 726 mediations (81.8%) into training were achieved, which increased to 9 016 mediations (88.0%) in 2013. At the same time, the PV agencies became the largest external actor of the Federal Agency for Labour and mediated the “Einstiegqualifizierung” (EQ, see section below) internships for several thousand candidates. From 2010 to 2013, the PV initiative mediated between 41% and 47% of all apprenticeship vacancies. During the period between 2007 and 2013, the PV projects were able to place 56 594 apprentices with SMEs and mediated 5 357 operational EQ internships with a total funding disbursement of EUR 30.2 million.

Source: BMWi (2014).

The agencies that provide PV services tend to work closely with regional employment agencies. A survey of PV services in 2014 found that 82% of chambers of craft and 71% of chambers of commerce work closely with regional employment agencies. The chambers of liberal professions and other economic organisations co-operate with the employment agencies on a case-related basis. When evaluated in 2014, regional employment agencies positively assessed the work carried out by the PV agencies, but noted that the PV initiative does not necessarily create additional places for trainees and apprentices.

The PV projects have set up a rapid and flexible process that is appreciated by SMEs. Around 40% to 50% of the SMEs surveyed in 2014 noted that their use of intermediate PV agencies had resulted in cost savings in the search and recruitment of trainees. Around 30% to 50% of the companies perceive the benefit of ensuring the competitiveness of their business. About 90% of those searching for a traineeship or apprenticeship appreciate the PV mediation offer as “largely helpful” and about 68% to 78% as “very useful”.

Broadly speaking, a survey of the organisations that use PV services in 2014 found that they provided added value. The PV projects of craft chambers and craft-related organisations achieve a high placement rate, whereby 16% to 19% of all apprenticeship applicants are assessed and advised through “informational interviews”. The “accuracy” of placement was considered satisfactory in more than half of the companies surveyed in 2014, indicating that the proposed candidates mostly fit the requirements of the apprenticeship vacancy. Only a small proportion of companies – between 9% and 17% – were disappointed by the candidates for apprenticeships that were provided by PV organisations.

However, the analysis also showed that gaps can emerge among SMEs that are not specifically affiliated with a single industry or profession, as they will not necessarily receive services from a particular chamber of industry or craft. Similarly, PV services offered by an intermediate organisation outside of the chambers of commerce or industry will typically offer their services to particular member companies or a set of company circles. PV services reach around 44% of companies associated with a particular craft, while only 17% of service companies make use of PV placement services.

Because the PV funding guidelines provide no detailed instructions to beneficiaries regarding consultation and conciliation, the PV agencies have developed a variety of local structures and practices over time. There is a wide degree of local diversity in the implementation and nature of PV services, and there has been some criticism that the initiative has not developed an overarching brand.

Around 87% of the PV agencies use the key concept of “accuracy” (“Passgenauigkeit”), while other PV projects use terms such as matching or coaching. A survey of PV agencies in 2014 found that they tended to exhibit systematic and goal-oriented consulting and mediation between enterprises and aspiring trainees. However, there were differences in the degree of professionalisation (structuring of business processes, targeted and standardised instruments) that was observed among PV agencies.

Einstiegsqualifizierung (EQ)

“Einstiegsqualifizierung” (EQ) is a work-based training programme that provides a form of introductory training for those aged under 25. It comprises a 6-12 month internship combined with vocational education. It was developed in order to provide basic vocational competences and company-based qualifications to jobseekers that have been unable to secure apprenticeships. After the successful completion of the EQ internship, the company is able to take on the candidate as an apprentice for a shortened duration. The EQ intern receives a payment of 216 euros per month from the BA. In June 2014, more than 11 000 adolescents took part in the introductory training scheme (BA, 2014b).

Participants in the scheme discuss their desire to achieve a diploma or a professional qualification with trained mediation professionals, who determine whether academic or pre-vocational programmes are more appropriate than EQ. The majority of young people and companies learn about EQ through public employment services. The Chambers of Crafts and Chambers of Commerce mediate 67-73% of EQ positions in their member companies. In particular, chambers will actively recruit companies with training experience (such as PV agencies, see section above) to mediate EQ positions.

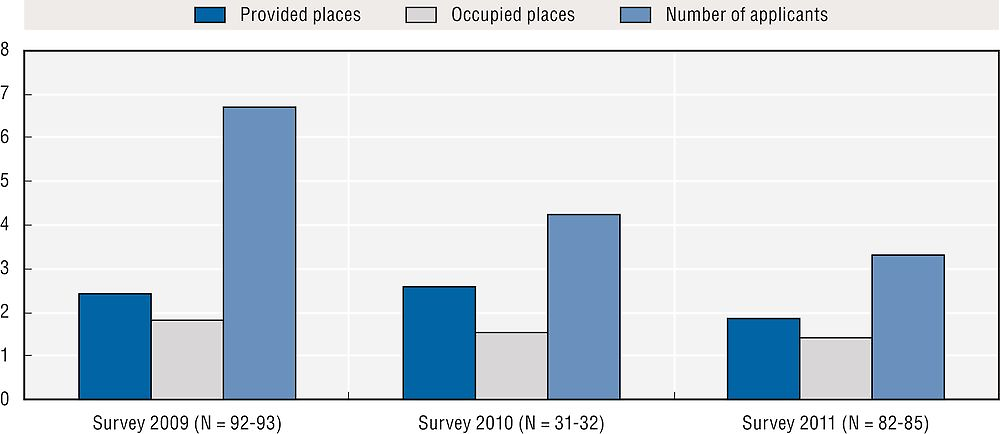

Over a three-year period from 2009 to 2011, companies were asked to provide information on their EQ programme and applicants. The surveyed companies tended to offer 1.8-2.4 EQ places but only tended to fill 1.4-1.8 of these places. While the number of applicants exceeded the number of offered positions in all surveyed years, the total number of occupied EQ places has been in decline over the surveyed period and the average number of applicants for each position has fallen from 6.7 to 3.3 (see Figure 4.7). This reflects the falling number of early school leavers, with fewer applicants available for the EQ scheme as a result.

Source: BMWi (2014).

The assessment of participating companies found there was good alignment of expectations between the programme’s participants and employers. The vast majority of EQ participants surveyed found that the majority of EQ enterprises shared their expectations with respect to social skills, external appearance and grades in subjects like German. The survey found that the majority of chambers of commerce, job centres and social security agencies found EQ to be either a very good or good method of supporting job applicants with limited placement opportunities and those without previous experience in the vocational training system. More than three quarters of the surveyed firms noted that EQ participants and conventional apprentices completed similar content in the first year of learning, namely guided job-related activities and auxiliary activities.

Participants reported largely positive outcomes from the introductory training. In 68% of cases, the participants note that they were better able to assess future career goals after the introductory training. More than half of respondents agreed that the introductory training corresponds to the desired training occupation, whereas only 11% of the participants were unsatisfied. However, surveyed participants noted that EQ is terminated before completion in 29% of reported cases. The job centres and social security agencies report an average drop-out rate of 25%, commensurate with the general rate of drop-outs for German apprentices. Some employers who are considered more conservative, such as the Chamber of Crafts, have high drop-out rates, while more liberal institutions tend to have higher rates of completion.

Early terminations could be attributed to several reasons. Firstly, dissatisfaction with social behaviour, motivation and reliability of the participants could be an issue. Another reason could be the early achievement of objectives – for example, participants may gain an apprenticeship during the EQ programme and opt to pursue that option instead. Young participants may also drop out due to personal problems with superiors and colleagues. In addition, very few businesses allow participants with learning difficulties or social disadvantages to use external support, which can seriously restrict the success of participants with learning disabilities to the EQ progamme.

In some German federal states, vocational schooling during the EQ programme is mandatory, whereas in others it depends on the age of participants. This is relevant because the inclusion of vocational training in the EQ phase can shorten the duration of any subsequent apprenticeships. The surveyed stakeholders noted that the handling of vocational school attendance was a prominent issue, and some advocated for a unified national vocational education scheme. Apprenticeships can be shortened for a number of reasons. The young people surveyed noted that 45% of apprenticeships had been shortened due to the completion of the EQ programme. In a further 42% of these cases, the apprenticeship was truncated due to professional school attendance or the successful completion of qualifications.

After the successful completion of the EQ programme, participants are eligible to receive a company certificate that outlines the acquired knowledge, skills and abilities. Participants can also receive a certificate from the relevant Chamber of Commerce. These documents then allow young people to enter the dual vocational training scheme. Over a three-year period, the practice of company-based certification increased to 62%. In 2011, 24% of participants received certification of the successful completion of EQ from chambers of commerce. This low rate of certification is because few training agencies and EQ participants apply for the relevant documents.

The majority of the chambers of commerce, job centres and social security agencies have assessed operational introductory training as either a very good or good support tool for those with limited placement opportunities or lack of training maturity. The evaluation shows that EQ participants experience an easier transition into training or employment. In each year of the three-year evaluation period, three-quarters of young people end up in vocational training or training in the profession of their EQ internship. This research provides a reasonable basis for the continuation of EQ programmes. However, the programme could be improved in a number of ways.

Entry qualifications should target the core demographics of young people with low maturity or individual placement constraints. Furthermore, the success of individually or socially disadvantaged young people should be taken into account throughout the allocation process. This could be supported by re-designing the application process to better determine whether the young person has a disability or is otherwise at-risk. Focussed measures can help the programme to reach the target group and smooth the transition between the EQ programme and further vocational education.

The stakeholder involved in the EQ process, particularly the Chambers of Commerce and employment agencies, could streamline their operations to better deliver services to disenfranchised youth. In addition, a clear and uniform definition across Federal States (published in the form of an action guideline or recommendation) and competent authorities could enable national recognition of training and allow graduates to move between regions. In order to boost the utility of the EQ programme, a stakeholder-led process should aim to significantly raise the certification ratio by emphasising the importance of obtaining a certificate or directly sending the application forms to the participants. Recruiting firms with more experience with the TVET system could also ensure that participants in the operational EQ programme have a more valuable experience.

The JOBSTARTER initiative

In 2006, a training structure programme called “JOBSTARTER” was introduced by the Federal Institute for Vocational Education and Training (“Bundesinstitut für Berufsbildung” – BIBB). The goal of the programme is to promote local projects that deepen the relationships between companies, chambers of commerce and employment agencies to create new apprenticeship places. Between 2006 and 2013, the projects of this programme created more than 60 000 new apprenticeship places (BIBB, 2013).

Since 2014, the JOBSTARTER initiative has entered a new programme period, named “JOBSTARTER plus- für die Zukunft ausbilden”, which aims to support SMEs in the acquisition of skilled labour. The second iteration of the JOBSTARTER initiative has two main goals: to better integrate young people into job training, and to intercept and integrate university dropouts. The existing KAUSA (“Koordinierungsstelle Ausbildung und Migration”) service centres aim to increase participation from young immigrants. The project also attempts to improve the mobility of young people in order to address supply and demand within and between regional training markets (BIBB 2014c, BMBF 2015).

One aspect of the JOBSTARTER initiative is the project “CONNECT”, which is based on the idea of fulfilling several elements (modules) to obtain a vocational certificate. These modules represent different occupational competences. At present, there are fourteen occupations divided into these elements (“Ausbildungsbausteine”). Participation in one or more of the modules is intended to count for subsequent firm-led training. The JOBSTARTER initiative also encourages part-time apprenticeships, whereby working hours are reduced to at least 20 hours per week. This should increase the number of companies willing to offer apprenticeships that may not have enough work for a full-time apprentice. In North Rhine-Westphalia, this initiative is accompanied by the “ModUs” project, which supports parents in the application process, organises childcare and mediates between the apprentice and employer in case of conflicts.

Jugendberufsagentur

In January 2011, the Senate of the Free Hansa City of Hamburg established the goal of giving every young person the opportunity to undertake vocational training, with a stronger focus on retaining youth who might have dropped out of the previous system. Hamburg was chosen as a model region to test the improved co-operation between stakeholders and jurisdictions of different Social Codes (SGB II, III and VIII).

In response, Hamburg established special job agencies for young people (“Jugendberufsagentur”) in 2012. The Youth Employment Agency (YEA) is a coalition of institutions that support adolescents under the age of 25 and provide guidance concerning vocational training or study, employment, entitlement to benefits and assistance in overcoming educational problems.

The co-operative partners of the YEA include:

-

The Employment Agency of Hamburg, which offers vocational and academic guidance as well as orientation and placement into available vocational training opportunities;

-

The Job Centre ‘team.arbeit.hamburg’, which supports youths who receive unemployment assistance;

-

The Authority for Schools and Vocational Training (BSB) and the Hamburg Institute for Vocational Education and Training (HIBB), two organisations that provide guidance about vocational schools and further education;

-

The Federal Agency for Labour, Social Affairs, Family and Integration (BASFI);

-

The district offices that assist disadvantaged youths with special needs.

The economy and the trade unions (Chambers of Crafts, Chambers of Commerce, UVNord and DGB, GEW and ver.di) are also represented on the Board of Directors (HIBB, 2012).

All young people in Hamburg must either finish the A-level schooling or receive vocational training to eventually take part in the labour market. Depending on their performance, Hamburger students can choose to attend upper school or start a vocational track educational training after the 10th grade. This results in a large number of young people searching for suitable pathways into training and employment. This transition may not be smooth for young people for a variety of reasons, including low academic performance, lack of housing, debts or a lack of information.

To combat this issue, the YEA provides consolidated information and personalised consultancy and mentoring services in one organisational unit. The YEA operates between and within governance levels to ensure joined up thinking. At the local level, the YEA directly advises students of school-leaving age while also acting to ensure the efficient provision of information at the district level. The YEA also works at the federal level to co-ordinate measures, monitor the labour market and transfer information between partner institutions. At the local level, the YEA and its co-operative partners arrange career counselling in schools from the eighth grade onwards in order to understand the students’ professional goals and the optimal pathways between education and work. All students who receive advice are registered with the Employment Agency, which allows the YEA to provide continuous supervision and support until they have found employment or vocational education opportunities.

Similarly, the YEA and its partners work at the regional level in all seven districts of Hamburg. Young people aged below 25 can opt to have their data shared between different institutions in the YEA framework, which facilitates integrated and specialised assistance. Young people can seek personalised guidance from offices that combine the services of employment agencies, Job Centre team.arbeit.hamburg, the Hamburg Institute for Vocational Education and Training (HIBB). This includes providing information about new educational or employment paths alongside services that address social disadvantage. The programme also empowers employees to actively seek out young people at home or elsewhere if they have repeatedly missed school, training or counselling appointments.

At the state level, the YEA’s Board of Directors and other economic and social stakeholders meet regularly to discuss and clarify significant issues of co-operation between institutions. They also co-ordinate publicly funded measures and test the accuracy, effectiveness and efficiency of employment services to young people. The YEA has also established a networking department at the state level that collects the data of students to assess the achievement of the YEA’s objectives. This department co-ordinates the commitment of the HIBB employees who participate in the career and study orientation procedures. In addition, they administratively manage the planning team and provide necessary data for forecasting their work by monitoring the activities of the YEA. In co‐operation with the planning management, they also support the national action plan of the Board of Directors (HIBB, 2015).

During a survey period between October 2013 and September 2014, 9 221 young participants made use of the measures offered by the Employment Agency. Among them, 37.1% have their first degree, while only 4.7% are without any qualifications. With the support of the YEA, the majority of the supervised candidates – namely 4 031 applicants – were able to access to dual training. Only 162 candidates began to undertake tertiary education (Freie und Hansestadt Hamburg, Jobcenter team.arbeit.hamburg, Agentur für Arbeit Hamburg, 2014).

Significant challenges are forecast to affect the YEA in the future, including providing better educational outcomes for young immigrants and refugees, and improving the permeability between vocational and academic education streams.

Employer-driven initiatives for German youth

There are a number of initiatives to improve employment services for German youth that have been piloted by employer groups in the private sector.

For example, the employers’ association “Nordmetall”, which covers 250 firms in the metal and electronics industry in northern Germany, developed a model called “Nord-Chance”. Young people interested in a metal or electronics job who have not found a vocational training opportunity within the placement period are offered the opportunity to gain a relevant qualification. They are trained and prepared by an educational institution for up to five months and subsequently placed in a firm. If the apprentice is subsequently found to be suitable for the job, he/she is eligible for vocational training opportunities. Within the firm, young people acquire basic knowledge and take part in firm-specific training modules. Furthermore, an allowance is paid during the preparation (150 Euros per month) and introductory training (300 Euros per month). The goal of this initiative is to engage about 1 000 young people with vocational training.

Another model called “Zukunft durch Ausbildung und Berufseinstieg” is carried out by the employers’ association “BAVC” of the chemical industry. Between 2014 and 2016, the programme aims to offer 9 200 vocational training opportunities each year. The collective agreement also includes a measure to prepare young people for training maturity (“Start in den Beruf”). It is targeted to young school leavers and qualifies them for vocational training for up to twelve months within an operational promotion scheme. In addition, the new agreement also allows for the participation of long-term unemployed persons over the age of 25.

Similarly, the foundation “Senior Experten Service” (SES), in co-operation with the umbrella organisations of the industrial and craft sectors and liberal professions, has introduced the “VerA” initiative to address the trend of discontinued or terminated vocational education. VerA organises about 1 000 retired volunteer professionals who guide young people in vocational education in times of crisis. Based upon trainees’ demand, SES appoints experts as training companions to offer support on issues ranging from technical questions about exam preparation to strengthening personal qualities such as motivation and self-confidence (Ies, 2013). VerA is also responsible for smoothing the transition from school to work as well as promoting the initiative to other partners.

VerA is free to use and can be initiated by employers, vocational schools or the apprentice and is carried out through support via telephone or mail. In more than 60% of cases, ongoing support is required for six months or less, while intensive support can extend for over two years. In about half of the cases, the reason for accompaniment was the monitoring and optimisation of the training. After six months, around one-third to half of all trainees improved in the area of “learning”. In 20% to 30% of cases, positive changes in “personal factors” like motivation or social skills are observed. Rare improvements are documented in the “external conditions” such as financial problems or diseases. In about two-thirds of all completed accompaniments, the objectives are fully met.

While the evaluation found that that surveyed trainees, training companions, regional co-ordinators and regional actors had similar opinions of the VerA initiative, there were still significant differences in outcomes based on gender, education and the number of meetings that occurred during the monitoring process. However, more meetings tended to improve the outcomes for female youth participating in the programme. It was also found that the migration background of trainees had no influence on the targets. Overall, 90% of trainees and attendants would recommend the VerA programme.

The initiative could be improved through increased evaluation and better matching of training companions and programme participants. To become or remain a competent actor, the training companion should strengthen their own experiences and skills. Since there are interfaces between the tasks of SES and regional co-ordination, the tasks and responsibility of regional co-ordination should be more clearly defined. In order to increase the acceptance of the VerA initiative and enhance the volunteer work, appropriate resources for a professionalised work could be introduced. Finally, it is also important that trainees are approached through number of media, including social media.

Other groups have focussed on improving the quality of vocational education. For example, the IHK and the Central Agency for Continuing Vocational Education and Training in the Skilled Crafts (ZWH) introduced the project “Stark für Ausbildung- Gute Ausbildung gibt Chancen”, which is supported by the Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Energy. This project focuses on the quality of the training staff. The scheme offers specific qualification and training to develop the special needs of disadvantaged young people.

Pathways from school to work – Broadening educational options for young people

After leaving secondary education institutions, most students decide to pursue dual vocational education or study through a tertiary institution. While tertiary education requires at least a secondary education certificate from a vocational secondary educational institution, there is no formal minimum requirement for starting dual vocational education. However, the completion of vocational education does not qualify learners for further tertiary education, which increases opportunities for those without a satisfactory secondary education degree but may reduce educational pathways after vocational education. This is significant because 76.9% of participants in the dual vocational education system did not meet the minimum secondary education standard for tertiary education and a significant minority (26.8%) were 17 years old or younger. A number of policy responses have been developed to address concerns about path dependency and limited future work opportunities for young people who enrol in the dual education system.

In 2009, the Conference of the Ministers of Education and Cultural Affairs announced that those with an advanced level of vocational education (“Meister”) or three years of professional experience would be eligible for tertiary education. Private colleges also offer shorter courses for persons with corresponding professional experience. Although universities are able to shorten tertiary degrees for applicants with professional experience, in practice this option is not widely exercised.

The federal state of Baden-Württemberg has piloted a programme to provide alternative pathways for young people. Those with an intermediate school leaving certificate will be eligible for a “Fachhochschulreife” after the successful completion of three years of the programme. The “Fachhochschulreife” entitles participants to study at universities of applied sciences.

Other states are developing early personalised vocational guidance and counselling through the school system to reduce drop-outs of schools and colleges and mitigate the issue of path dependence. A new initiative called “Berufswahlsiegel” awards schools with outstanding vocational guidance and counselling services. A similar project called “Starke Schule” is supported and managed by the Hertie-Stiftung, BA, BDA and the Deutsche Bank Stiftung.

Other initiatives exist to support the transition from education to work. In 2010, the Ministry of Education (BMBF) founded the “Bildungsketten” (education chains) programme to assist young people with special needs who are likely to drop out of school without a certificate. The programme has three elements: analysis, career orientation and support for starting careers. Qualified teachers conduct interviews with children in seventh grade and analyse their strengths and weaknesses with respect to technical competence (e.g. problem solving competence), personal motivation and social skills (e.g. communicative ability). In the following year, personal guidance counsellors help participants to orient career goals through personal advice and assistance with finding internships and apprenticeships. Guidance counsellors continue to assist participants until the completion of their first year of the vocational training (BMBF, 2013a). Over 50 000 people aged 25 years or younger were involved in the programme in each month of 2014, a rise from previous years (BA, 2014b).

Another programme called “Berufsorientierungsprogramm” aims to assist students in the eighth grade with career orientation. Over a two week period, students gain practical experience from qualified trainers in three occupations in order to determine the occupations that best fit their personal aptitudes and motivations. Since its inception in 2008, over 450 000 school students have participated in the programme (BMBF, 2013b). The Federal Employment Agency supports these efforts by organising over 90 000 information events at school and universities. Job counsellors talk to students, ask them about their interests and aptitudes, present career paths and point out sustainable apprenticeships and study programmes.

The accessibility of apprenticeships is a challenge for the German vocational education system. The most vulnerable youths, particularly those with only a basic or no school leaving certificate, face major barriers to entry to the regular vocational training system. In order to mitigate this, it is possible for those interested in vocational education to take a training year (“Berufsvorbereitungsjahr”) prior to entering the regular dual vocational education. The Berufsvorbereitungsjahr is compulsory for adolescents under the age of 18 who have not completed any type of lower secondary education and have been unable to find an apprenticeship. Students completing the training year complete general education and training in a chosen occupational field on a full-time basis at a vocational school. In 2012, 49 000 students chose this route towards vocational education. Successful graduates are awarded with a basic lower secondary school leaving certificate at the level of “Hauptschule”, and are then eligible for an apprenticeship or further basic vocational training through a “Berufsgrundbildungsjahr”. This is an additional year of occupational training in fields such as construction technology or domestic management. Upon the successful completion of the Berufsgrundbildungsjahr, students may be awarded a lower secondary school certificate or have the opportunity to reduce the duration of future apprenticeships. In 2012, over 28 000 students participated in this pathway towards vocational education. Although students are not eligible for payment during the “Berufsvorbereitungsjahr” or the “Berufsgrundbildungsjahr”,they can receive financial support through the BAFöG (§ 2 BAföG) if they do not live with their parents.

There are other methods of bridging school and employment in Germany. Secondary school graduates can choose to complete a voluntary social year (“Freiwilliger Soziales Jahr”, FSJ) through a state-funded civic engagement programme for 6-24 months. Applicants must be under 27 years old and must have fulfilled attended all compulsory secondary education. The successful participants receive free lodging and board, work clothes and additional pocket money (approximately 350 Euros per month § 2 JFDG) in order to enable them to work at German or foreign public interest organisations such as charities, hospitals, church communities or human rights organisations. Other options available include a more environmental programme known as the “Frewilliges Ökologisches Jahr” (FÖJ), and state-funded voluntary work programmes like the federal volunteer service (“Bundesfreiwilligendienst”, BFD). Approximately 100 000 young people in Germany participated in one of the three programmes in 2014 (BMFSFJ, 2014). School graduates can also choose to join the voluntary military service (“Freiwilliger Wehrdienst”, FWD) for a period of 6-23 months. Volunteers receive free board, lodging and a salary that ranges from 777 euros to 1146 euros per month. In 2014, there were approximately 8 500 young people in the voluntary military service (Bundeswehr, 2014).

In 2013, approximately 250 000 young people participated in one of these alternative pathways to employment, which was roughly half the amount of trainees participating in the dual vocational system. However, interest in these transitions from education to work has declined since 2005, when over 400 000 young people took part in an alternative programme or scheme.

Conclusion and key findings

This Chapter has a number of key findings which reflect the structure and nature of the broader German vocational education system and its impacts with young people.

One key finding is that employers throughout Germany are systematically involved in the provision of vocational education. They provide training positions and partially fund the system. They also have a strong influence on the development of curricula and examination through collaboration at the federal level with the Federal Employment Agency, and ongoing discussions with regional chambers of commerce, regional employment agencies and social services. Employers who provided training places through the federal PV initiative and the EQ programme reported that their expectations with respect to the skills and attitudes of apprentices were largely met. Ensuring ongoing employer engagement in the vocational education and training system can help to align the needs of business with the requirements of young people, and may contribute to the general level of success of initiatives targeted towards German youth.

This Chapter has been strongly shaped by the significance of the vocational education system in Germany and the importance of vocational education to youth-related labour market policy. In most cases, the vocational education system is continuously reformed by policy innovations that aim to improve the transition from school to work for the most vulnerable young people.

This Chapter has also found that active labour market policies, including preparatory training schemes, personalised placement of apprentices and trainees and employer-led initiatives have been broadly successful in Germany. These programmes often specifically target vulnerable young people who may otherwise face serious obstacles when trying to access the vocational education and training system. In these cases, a focus on personalised assistance and the development of competences through workplace embedded training has appeared to increase the opportunities available to at-risk youth. Deepening co-ordination between different layers of governance and different stakeholders, including employers, training providers, employment agencies and chambers of commerce, are also a feature of a number of regional youth-focussed active labour market policies.

Improving the number and placement of apprenticeships has also been a focus of a number of federal and regional initiatives for at-risk youth. While Germany has a long history of dual education and around 50% of those enterprises that are eligible to offer apprenticeships do so, there are still a large number of young people who fail to find a suitable training place. In response to this problem, the PV programme has aimed to improve the placement of apprentices with SMEs while the JOBSTARTER initiative has attempted to increase the number of apprenticeships available by facilitating part-time or shorter duration placements. Expanding the opportunities for vocational education across Germany can help young people bridge education and employment and boost the overall performance of the German labour market.

While the vocational education system is often a part of the solution in addressing youth unemployment, it can also cause problems. The inclusion of disadvantaged young people and removing path dependencies for those with higher abilities are two major issues facing the German youth labour market.

For young people leaving compulsory education, embarking on a vocational education pathway can be an obstacle to future tertiary education. Some attempts have been made to improve this issue by recognising vocational attainments as qualifications for tertiary education. However, the German labour market is still relatively segregated between young people with tertiary qualifications and those with vocational qualifications.

Access to the vocational education system is not guaranteed for all young people, not least because employers are not obliged to employ apprentices. Young people with low or no levels of secondary educational attainment or with specific disadvantages and disabilities often have trouble finding a training provider or apprenticeship place. These youths can either receive further school-based training in the transition system or, as in the framework of the JOBSTARTER initiative, they can receive several modular elements (modules) to obtain a vocational certificate. While some programmes aim to improve outcomes for disadvantaged young people, others do not make specific provision or assistance for young people with specific issues. For example, while the EQ programme aims to support young people with social disadvantages and learning disabilities, the relatively high drop-out rate may reflect a lack of customised support and assistance for vulnerable participants.

Other public initiatives target separate weaknesses of the vocational education system. For example, the Hamburger Jugendberufsagentur specifically aims to provide integrated employment services to youth who may have disengaged from the broader vocational education and training system. On the other hand, the PV programme customises the placement of trainees in small to medium-sized enterprises and aims to address skills mismatch while strengthening the SME sector in the medium- to long-term.

Employer groups have also developed initiatives to target young people. The “Nord-Chance” programme developed by the North German metal and electronics industry allows young people who have not found a vocational training opportunity within the placement period to pursue an industry qualification. Accordingly, they are trained and prepared by an educational institution for up to five months and subsequently placed in a firm. Similarly, the VerA initiative by the foundation “Senior Experten Service” (SES) aims to reduce the rate of early termination rate for vocational education by providing specialised support to young people through a team of 1 000 retired volunteer professionals.

References

BA- Bundesagentur für Arbeit (2014a), “BA-Finanzen – Monatsergebnisse des Beitragshaushalts, September 2014”, Nürnberg.

BA- Bundesagentur für Arbeit (2014b), “Arbeitsmarkt in Zahlen – Förderstatistik: Ausgewählte arbeitsmarktpolitische Instrumente für Personen unter 25 Jahre”, Nürnberg.

BIBB- Bundesinstitut für Berufsbildung (2015), “Neue Wege in die duale Ausbildung- Heterogenität als Chance für die Fachkräftesicherung: Ergebnisse, Schlussfolgerungen und Empfehlungen”, Bonn.

BIBB- Bundesinstitut für Berufsbildung (2014a), “Tarifliche Ausbildungsvergütungen 2013 in Euro: Gesamtübersicht 2013 nach Berufen”, Bonn.

BIBB- Bundesinstitut für Berufsbildung (2014b), “Tarifliche Ausbildungsvergütungen 1976 bis 2013 in Euro: Übersicht über die Entwicklung der Gesamtvergütungsdurchschnitte”, Bonn.

BIBB- Bundesinstitut für Berufsbildung (2014c), “Studienabbrecher für die duale Berufsausbildung gewinnen- Ergebnisse aus dem BIBB- Expertenmonitor Berufliche Bildung 2014”, Bonn.

BIBB- Bundesinstitut für Berufsbildung (2013), “JOBSTARTER Monitoring”, Bonn.

BMBF- Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung (2015), “Auf zu neuen Ufern! Mobilität in der dualen Ausbildung”, Ausgabe 1/2015, Bonn.

BMBF- Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung (2013a), “Berufseinstiegsbegleitung – die Möglichmache”’, Bonn.

BMBF- Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung (2013b), “Praxis erfahren! Das Berufsorientierungsprogrammem”, Bonn.

BMFSFJ- Bundesministerium für Familie, Senioren, Frauen und Jugend (2014), “Zeit, das Richtige zu tun, Freiwillig engagiert in Deutschland – Bundesfreiwilligendienst, Freiwilliges Soziales Jahr, Freiwilliges Ökologisches Jahr”, Berlin.

BMWi- Bundesministerium für Wirtschaft und Energie (2014), “Evaluierung des Förderprogrammems ‘Passgenaue Vermittlung Auszubildender an ausbildungswillige Unternehmen’ Abschlussbericht der Evaluation und Wirtschaftlichkeitsuntersuchung”, Bonn.

Bundeswehr (2014), “Freiwilliger Wehrdienst FWD”, downloadable from: https://mil.bundeswehr-karriere.de/portal/a/milkarriere/ihrekarriere/fwdmp (date: 10.10.2014).

Freie und Hansestadt Hamburg, Jobcenter team.arbeit.hamburg, Agentur für Arbeit Hamburg (2014), “Zwei Jahre Jugendberufsagentur Hamburg”, downloadable from: www.hamburg.de/contentblob/4436922/data/zwei-jahre-jugendberufsagentur.pdf (date: 01.12.2015).

HIBB- Hamburger Institut für Berufliche Bildung (2015), “Chancen und Übergänge verbessern, Durchlässigkeit erhöhen”, in: Berufliche Bildung Hamburg, downloadable from: www.hibb.hamburg.de/index.php/file/download/2446 (date: 01.12.2015).

HIBB- Hamburger Institut für Berufliche Bildung (2012), “Jugendberufsagentur – Begleitung von Klasse 8 bis zum Berufsabschluss”, in: Berufliche Bildung Hamburg, downloadable from: http://ftp.hbzv.com/Schulbehoerde/bbh_Ausgabe_02-2012 (date: 01.12.2015).

Ies- Institut für Entwicklungsplanung und Strukturforschung GmbH (2013), “Evaluation der Initiative VerA des Senior Experten Service”, Bericht 10.1.13. Hannover.

OECD (2015), Education at a Glance 2015: OECD Indicators, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/eag-2015-en.

Statistisches Bundesamt (2015), Berufsbildungsstatistik zum 31.12. Wiesbaden.

Statistisches Bundesamt (2013), “Bildung und Kultur: Berufliche Bildung”, Fachserie 11 Reihe 3, Wiesbaden.