Chapter 3. Transport

The various types of transport (road, rail and maritime) together generate a turnover of about 5.08% of Romania’s GDP and employs about 133 100 people. Although Romania’s road transport is among the most regulated in the European Union, its rail transport is one of the most liberalised rail transport markets. Road transport is constrained by unnecessary documentation, such as authorisations for vehicle repair, complicated payment of local taxes, display of vehicle plates and copies of transport licences. Rail transport suffers from unclear provisions relating to private and public railway infrastructure and the ambiguous position of Romania’s state-owned rail freight operator in regard to private operators. Inland waterway and maritime transport is constrained by the lack of transparency in tariff calculation, a lack of open competition for pilotage and towage services and undue discretion given to the Romanian Naval Authority (ANR) regarding compliance of market participants with state regulations.

3.1. Economic overview of the Romanian freight transport sector

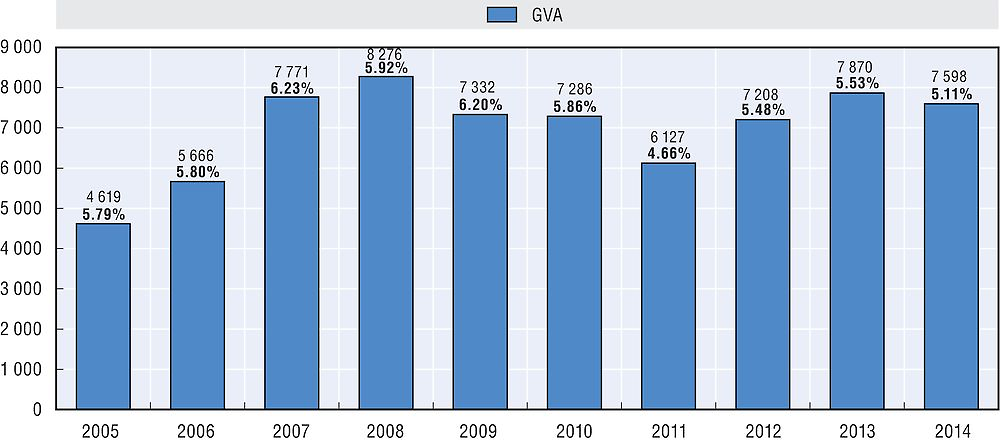

The freight transport sector includes activities related to the following transport modalities: road, rail, inland waterways, maritime and support activities for transport such as warehousing.1 The freight transport sector plays an important role in the country’s economy, generating a turnover of approximately 5.08% of gross domestic product (GDP) in 2014 and employing 133 100 people. Figure 3.1 shows that in 2014 the transport sector (including passengers) generated a gross value added (GVA) of approximately EUR 7.6 billion, representing 5.11% of Romania’s GDP. In 2014, Romania’s gross domestic product reached EUR 148.7 billion.

Source: Eurostat, National Accounts aggregates by industry (database), http://bit.ly/1Wn1OhH, GDP and main components (database), http://bit.ly/1dBAzYR (accessed on 26 January 2016).

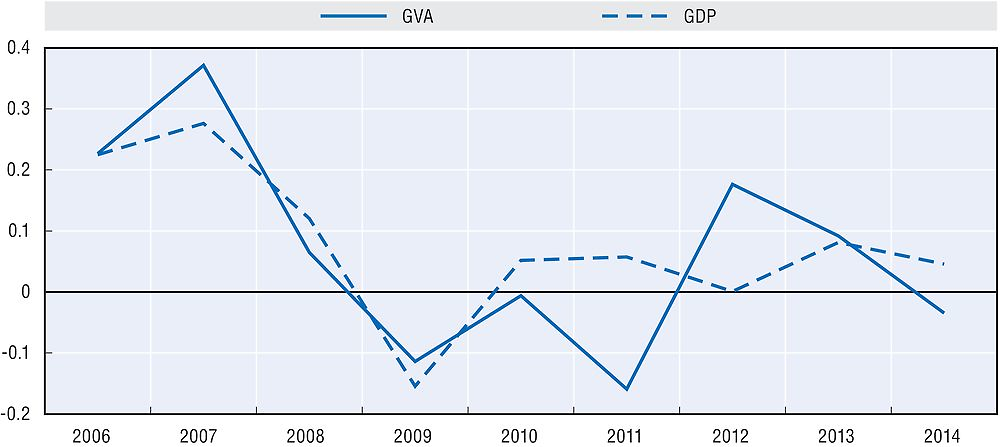

Figure 3.2 shows the relationship between the evolution of Romanian transport’s GVA and GDP.

Source: Eurostat, National Accounts aggregates by industry (database), http://bit.ly/1Wn1OhH, GDP and main components (database), http://bit.ly/1dBAzYR (accessed on 26 January 2016) and Musliu şi Asociaţii calculations.

According to Romania’s NIS, there were approximately 133 100 people employed in the freight industry in 2014, working for a total of 25 125 firms, of which 24 892 were operating in the road transport sector. Most of the companies are either small or medium-sized. Approximately 91% of these companies have 1 to 10 employees, 8% have 10 to 50 employees while the remaining companies exceed 50 employees. Employment in the freight transport sector has increased by approximately 12% from 2008 to 2014, although this increase relates exclusively to the road transport sector.

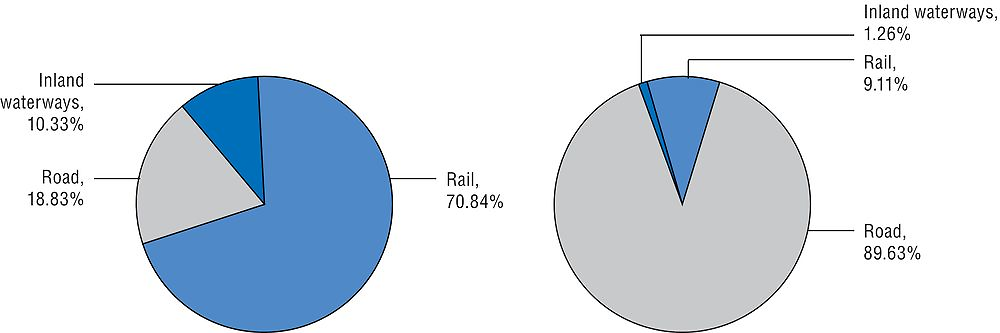

Figure 3.3 compares the modal split of Romanian inland freight transport in volume and value. In volume terms, the split was 70.84% for road, 18.83% for rail and 10.33% for inland waterways. In value terms, the split was 89.63% for road, 9.11% for rail and 1.26% for inland waterways.

Source: NIS, Goods transport, by mode of transport (database), http://bit.ly/21a7Nxe (accessed on 26 January 2016) and Musliu şi Asociaţii calculations.

Figure 3.4 shows the overall modal split of freight transported within and outside Romania including maritime and air transport in 2014. In volume terms, this was 60.95% road, 16.2% rail, 13.95% maritime, 8.89% inland waterways and 0.01% for air. In value terms, the split was 88.54% road, 9% rail, 1.25% inland waterways, 0.98% maritime and 0.23% air.

Source: NIS, Goods transport, by mode of transport (database), http://bit.ly/21a7Nxe (accessed on 26 January 2016) and Musliu şi Asociaţii calculations.

Road freight transport

Definition

The road freight transport sector refers to the transportation of goods between economic enterprises and between enterprises and consumers, including bulk goods and goods requiring special handling, such as refrigerated and dangerous goods.2

Transport can be for own-account (e.g. freight transportation between establishments belonging to the same firm) and for hire or reward. In Romania, road transport is the principal modality of moving freight, representing 70.84% of all inland freight transport volumes.

Infrastructure

The total length of the road network is 85 362 km as shown in Table 3.1. The roads are uniformly distributed along the country, the only exception being the Bucharest-Ilfov region which has a much higher density of public roads and where the majority of business is concentrated. Over the last eight years, the Romanian road network has grown by almost 12 000 km. However, there are still gaps in the highway system and connections between regions are still insufficient. The poor infrastructure is reflected in the length of the country’s road network, notably with respect to motorways and national roads. The network of motorways and national roads represents only 20% of the entire network, as shown in Table 3.1 below. In addition, approximately 90% of the national road network is made up of roads with only one traffic lane for each direction and with very low speed limits (average 66 km/h). This has an impact on both freight delivery time and safety. These roads do not ensure the possibility of overtaking local agrarian vehicles and thus reduce safety for heavy freight transport vehicles, which are the major users of the national road network.3

According to the National Union of Romanian Road Hauliers,4 to reach the European Union (EU) average of road network of motorways, Romania should build another 3 150 km of road.

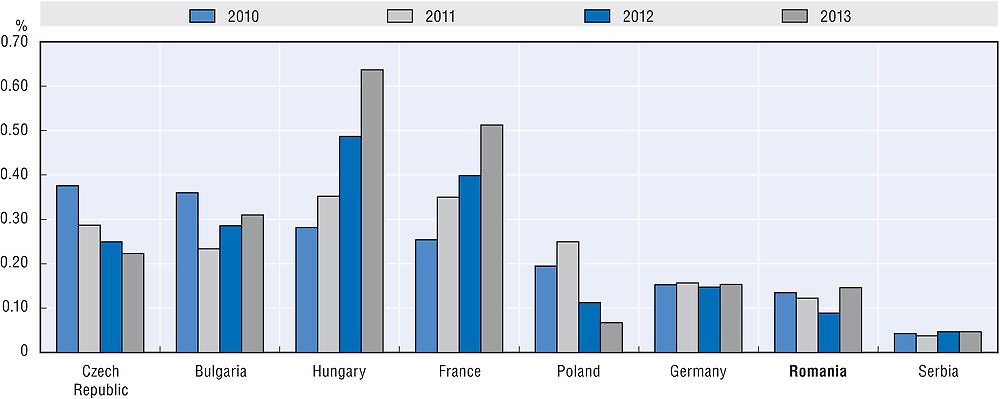

Nevertheless, Romania has made a significant investment in its road transport infrastructure over the past 4 years, although the trend and size of such investment differs significantly in Central and Eastern European (CEE) countries compared to Western European countries, as shown in Figure 3.5.

Source: OECD, Statistics, Infrastructure investment (Database), http://bit.ly/1ObFyBD (accessed on 26 January 2016).

Source: OECD, Statistics, Infrastructure investment (Database), http://bit.ly/1ObFyBD (accessed on 26 January 2016) and Eurostat, GDP and main components (database), http://bit.ly/1dBAzYR (accessed on 26 January 2016).

International comparison

The Romanian road freight industry sector is dominated by competition in prices and quality of service. Two broad categories of road freight regulation exist in OECD countries:5 i) rules on traffic and vehicles and ii) rules on access to the marketplace. The first category includes the Highway Code, labour issues, carriage of hazardous substances and traffic restrictions. The second category covers mainly market access restrictions and price regulations. The main issues targeted by road freight regulation relate to safety, impact on the environment and use as well as maintenance of the infrastructure.

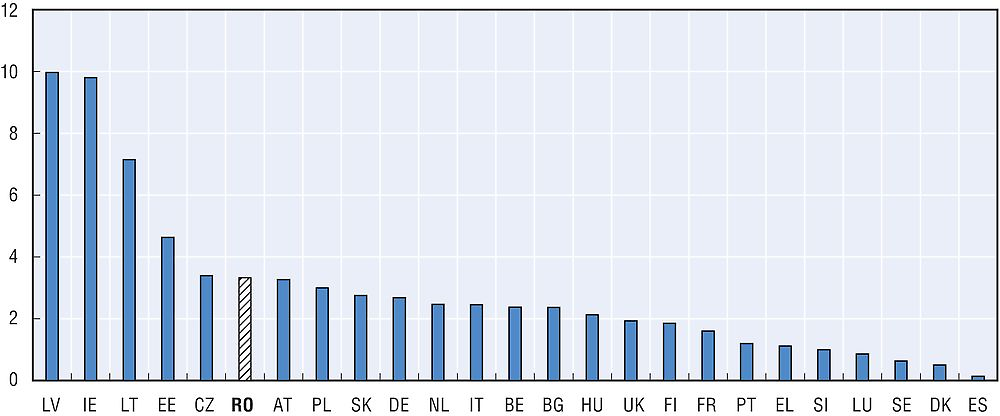

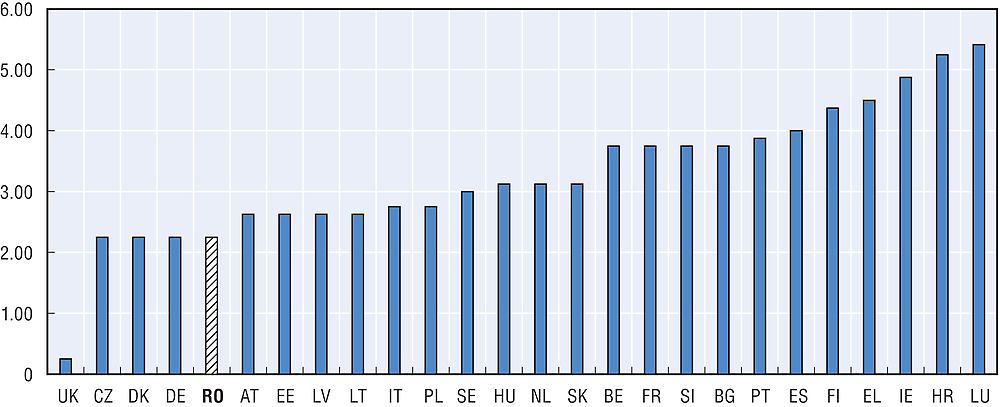

Figure 3.7 illustrates a comparison between Romania and other EU countries over regulatory constraints in road freight transport. According to the OECD’s Product Market Regulation Indicator (PMRI),6 Romania’s road freight industry is one of the most regulated in the EU.

Source: OECD PMRI, http://bit.ly/1VzCOE4.

Subsector characteristics

According to Romania’s NIS, the overall value of the road freight transport sector in 2014 was about EUR 6.8 billion and accounted for about 4.56% of Romania’s GDP. In the same year, employment reached approximately 117 200 people with 24 892 firms operating in this sector. The industry mainly consists of small companies, with about 91% of companies having 1 to 10 employees, 8% having 10 to 50 employees and only 1% having more than 50 employees. Over the last five years, the number of firms active in road freight has increased by approximately 10%, while employment has grown by 33%.

According to the Ministry of Finance (MoF), the largest players in road freight transport in the year 2014, expressed in turnover’s terms, were as follows:

Road freight transport in Romania is a very fragmented subsector, characterised by the predominance of small firms.

The most important trade associations in road freight transport are: the National Union of Romanian Road Hauliers (UNTRR),7 Romanian Association of International Road Transport (ARTRI),8 Federation of Romanian Transport Operators (FORT),9 Transport Heritage Association Europe 2002 (APTE2002),10 Transylvania Road Hauliers Association (ATRT),11 Road Hauliers in Construction Association (ATRC),12 Freight Forwarders Association (USER)13 and Romanian-Italian Association of Logistics and Management (ARILOG).14

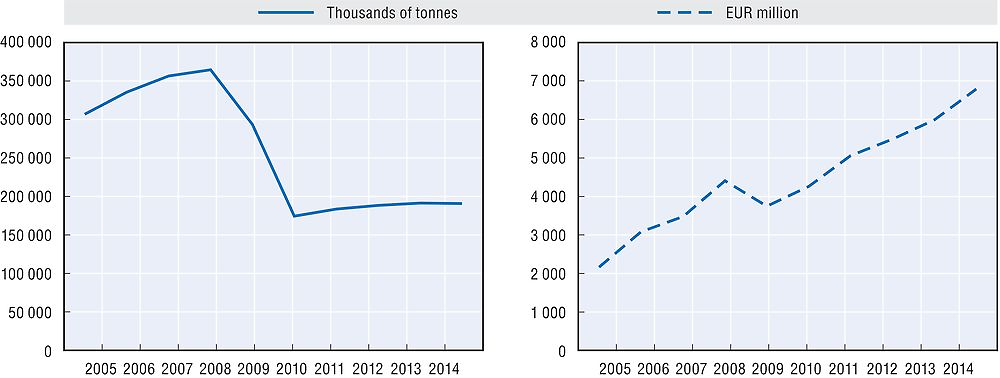

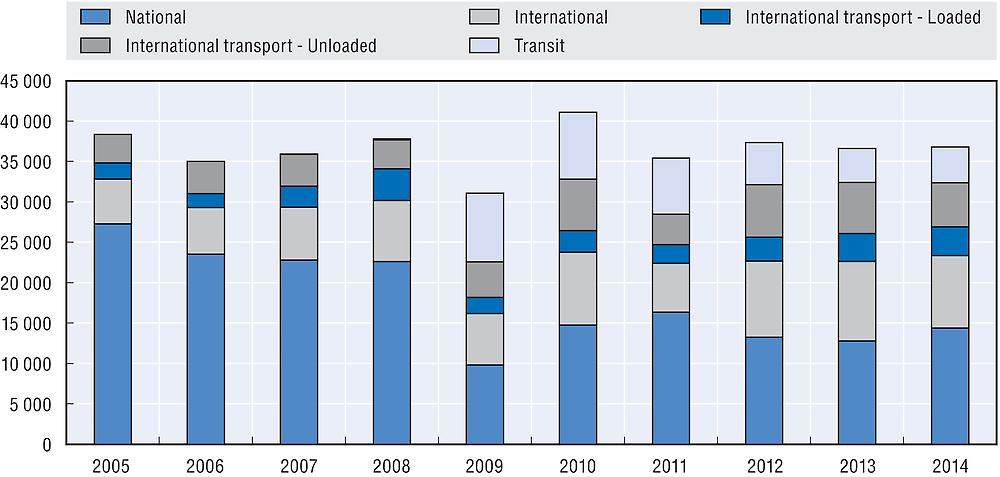

Figure 3.8 illustrates the evolution of Romanian road freight transport over the last decade (2005-14). This sector exhibits a sharp decrease during the outbreak of the global financial crisis, with a post-crisis gradual increase. The annual growth rate of goods transported by road decreased from +9.2% in 2006 to -0.3% in 2014. In value terms, the Compound Annual Growth Rate (CAGR) has fallen from +27% before the crisis to +12% in the period between 2009 and 2014.

← 1. The data on volume represents inland traffic whereas that on value also corresponds to freight road transport services provided by Romanian companies abroad. This may explain why over the crisis period, turnover increased whereas volume decreased.

Source: NIS, Goods transport, by mode of transport (database), http://bit.ly/21a7Nxe (accessed on 26 January 2016).

Road freight transport is the second transport modality used for import and export in Romania, following maritime transport. As shown in Figure 3.9, about 13.4% of the volume of goods transported by road in 2014 represented international transport. Transit transport is very low due to the lack of an efficient infrastructure. Indeed, Romania has not yet taken advantage of its status as a transit country for the southern regions of Eastern Europe.

Source: Eurostat, Summary of annual road freight transport by type of operation and type of transport (database), http://bit.ly/1yussbN (accessed on 26 January 2016).

According to the NIS, the main categories of goods that were transported by road in 2014 were: metal ores and other mining products (32.16%), non-metallic mineral products (19.8%), food products (8.98%), agriculture products (6.17%), wood and products of wood and cork (5.26%), secondary raw materials and municipal waste (3.24%), basic metals (3.05%) and coke and refined petroleum products (2.31%). Demand is therefore driven mainly by the following industry sectors: extraction, quarry, cement, food, agriculture and forestry.

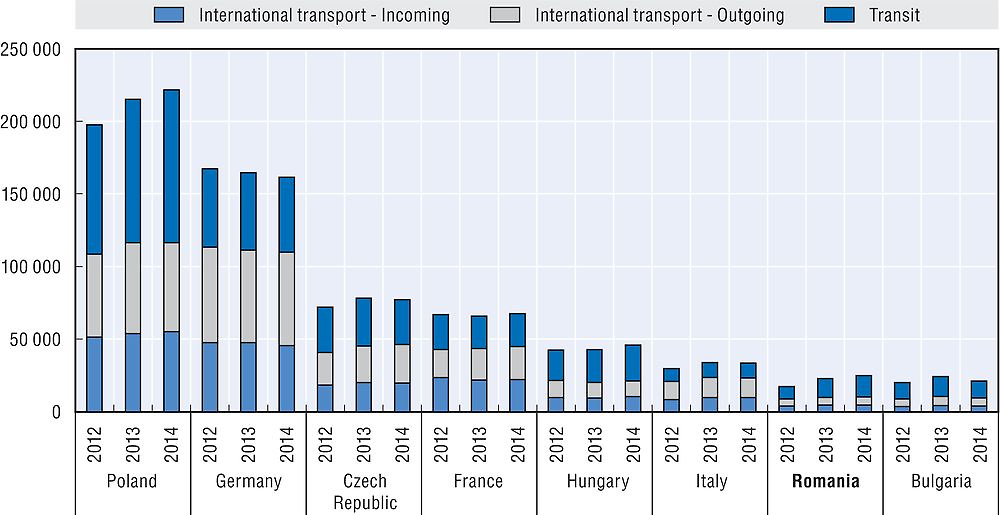

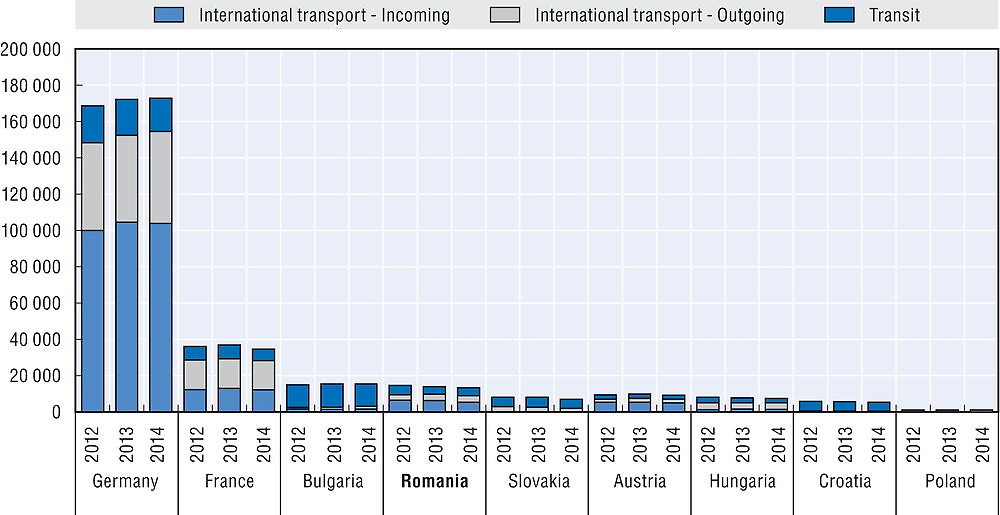

International road transport

As shown in Figure 3.10, compared to other EU countries, Romania operates small volumes of international traffic, including incoming, outgoing and transit international freight transport. Transit volumes are particularly small even if compared to other CEE countries, namely Hungary, Poland and the Czech Republic.

Source: Eurostat, Summary of annual road freight transport by type of operation and type of transport (database), http://bit.ly/1yussbN (accessed on 26 January 2016).

Relevant government authorities

The Ministry of Transport (MoT) is the central body of the state administration in charge of transport policy. The Ministry is responsible for regulation, economic policy and international agreements in the area of transport.

Other regulatory powers with respect to road transport are as follows:

-

Romanian Automotive Register (RAR) is a technical specialised body designated by the MoT as the competent authority in the field of road vehicles, road safety, environmental protection and quality assurance. The RAR has the following main tasks: granting national approval and certification of conformity for classes as well as individual road vehicles; licensing technical inspection stations and overlooking their activity.15

-

State Inspectorate for Road Transport Control is a permanent technical specialised body under the MoT monitoring compliance with national and international regulations in road transport, mainly regarding: the conditions for carrying out road transport activities; the training required to obtain a driving licence; road safety and environmental protection; technical conditions of road vehicles; tonnage and/or maximum size allowed on public roads.16

-

Inter-ministerial Council for Road Safety is a Government advisory body without a legal personality. Its main tasks consists of developing strategies for national road safety and priority actions for implementing these strategies; assessing the impact of road safety policy and coordinating research and communication related to road safety.17

-

Romanian Road Authority is a technical specialised body of the MoT. Its main activities are: delivering licences for road transport activities and professional certifications of specific transport personnel; evaluating the impact of state policies on road safety, through carrying out road safety audits, safety inspections, training activities, certification and professional training of road safety auditors.18

-

Regional and Municipal Councils control regional roads and may apply taxes in addition to the RO-vignette19 as well as establishing traffic rules and speed limits affecting freight hauliers, given that regional and municipal roads make up approximately 80% of the entire Romanian national road network.

Rail freight transport

Definition of the relevant sectors and ares of investigation

Rail freight refers to freight, cargo or goods transported by railways and does not include parcels or baggage transport services associated with railway passenger services.20

Infrastructure

The Romanian rail network is operated by Compania Naţională de Căi Ferate “CFR” (National Railway Company “CFR”) and covers the majority of urban and economic centres. It is connected to the European rail network by the railway administrations of neighbouring countries, namely Hungary, Serbia, Bulgaria, Moldova and Ukraine.

The network consists of approximately 20 000 km of track, with a railway route length of 10 777 km,21 of which around 37% is electrified (compared with the EU27 average of 52%).22 A significant proportion (72%) of the rail network is single track type; the EU27 average is 59%.

The length of Romania’s railway network has been constant over the last years. Due to the lack of maintenance funds, the technical parameters of the public railway infrastructure suffer continuing damage. This leads to a reduced quality of the services provided, one of them being a reduced speed for commercial freight trains (approximately 28.3 km/h). This affects the delivery time of rail freight transport which in Romania is significantly slower than road freight transport and explains the preference expressed by the business sector for road. The average delivery time of a container by rail normally exceeds that by road, due to the condition of the infrastructure and delays in the transferring/handling of containers from terminals.23

As shown in Figure 3.11, notwithstanding the above problems, Romania has made little investment in upgrading its rail infrastructure from 2010 to 2013.

Source: OECD, Statistics, Infrastructure investment (Database), http://bit.ly/1ObFyBD (accessed on 26 January 2016).

Source: OECD, Statistics, Infrastructure investment (database), http://bit.ly/1ObFyBD (accessed on 26 January 2016) and Eurostat, GDP and main components (database), http://bit.ly/1dBAzYR (accessed on 26 January 2016).

An important element affecting access to the marketplace is the infrastructure access fee. Calculating and levying this fee is the responsibility of the infrastructure manager, in line with EU legislation. The methodology for calculating this fee is based on the following charges: distance run, gross tonnage, traffic type (freight or passenger), route of movement, class of traffic section and its electrification systems for supplying traction.24

In order to have access to the railway infrastructure, railway transport operators must conclude an infrastructure access contract with the National Railway Company “CFR”. The access contract establishes the rights and obligations of CFR and railway transport operators concerning infrastructure capacity allocation and utilisation.

Figure 3.13 below shows that Romania has one of the highest railway infrastructure access fees among EU countries.

Source: European Commission (2014), Fourth report on monitoring development in the rail market, Report from the Commission to the Council and the European Parliament, 13.06.2014, http://bit.ly/1PMs4OR.

Liberalisation of the transport sector started in 1998 when the National Company of Romanian Railways, the old state-owned monopoly, was split into five independently-administered companies: CFR SA (dealing with infrastructure), CFR Călători (the operator of passenger trains), CFR Marfă (freight railway transport company), CFR Gevaro (services linked with restaurant cars) and SAAF (dealing with excess rolling stock to be sold, leased or scrapped). Following the introduction of open access to the monopoly infrastructure,25 competition among rail freight operators has increased over time. The market share of CFR Marfă has dropped from 100% in the year 2000 to just under 35% at the end of 2014.26 New entrants are therefore controlling more than half of this market.

In 2013, the MoT tried to privatise the national company CFR Marfă by selling off 51% of its share capital. Grup Feroviar Român, the second largest company operating in this sector, fulfilled all stages of the tender procedure and became the only qualified company to submit a tender for purchasing CFR Marfă in accordance with the conditions established by the MoT. The share purchase agreement between the MoT and Grup Feroviar Român was signed on 2 September 2013.27 The Romanian government set 13 October 2013 as the deadline for completion of privatisation of CFR Marfă, but in the end the transaction has not gone through.

International comparison

Figure 3.14 shows a comparison across EU markets of the degree of regulation in rail transport developed by the OECD.28 According to the OECD’s PMRI, Romania is one of the countries with the most liberalised rail transport in the EU.

Source: OECD PMRI, http://bit.ly/1VzCOE4.

Subsector characteristics

The freight transport sector is undergoing a severe structural crisis. Since 2008, about 10 000 jobs have been lost in this subsector.29 In 2013, the freight rail transport subsector generated an overall value of approximately EUR 680 million providing employment to approximately 16 400 people.30 In 2014, the same subsector generated an overall value of approximately EUR 603 million providing employment to approximately 13 500 people.31

The major player in this subsector is CFR Marfă, the former monopolist. Since 2001, an important number of private companies have entered the marketplace. According to data published by AFER (Romanian Railway Authority) on 31 December 2015, there are 23 railway freight operators, in addition to the state-owned CFR Marfă.

According to AFER and the MoF, the main rail freight companies in 2014, in terms of revenues, were as follows:

Competition in the Romanian rail freight subsector has increased over the past 10 years. In the year 2000, CFR Marfă was the only company in this sector whereas in 2009 there were 12 companies operating in the market and in 2015 this number increased to 24 companies. The incumbent company CFR Marfă has constantly lost market share in favour of competing private companies.

The most important trade associations in the rail freight sector are the Association of Romanian Railway Transport Operators32 and the Association of Romanian Railway Industry.33

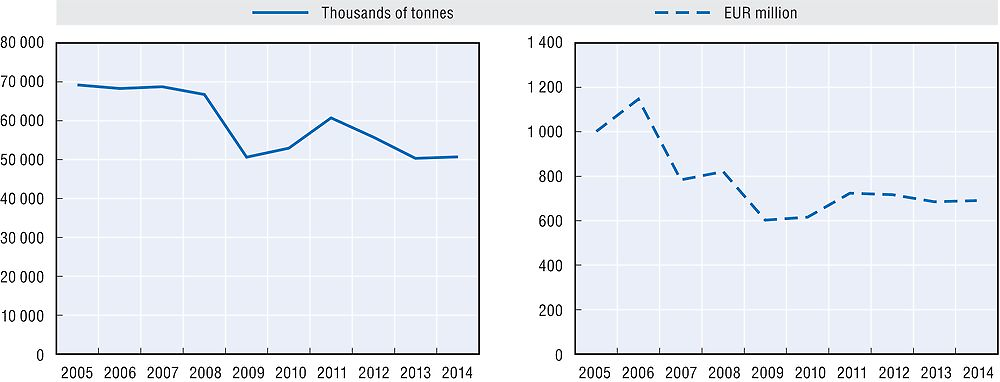

Figure 3.15 illustrates the evolution of rail freight transport over the last decade in Romania (2005-14), both in volume and in value terms. The rail freight transport recorded significant declines in the last 9 years, with the volume of goods transported by rail dropping from approximately 69 million tonnes in 2005 to approximately 50 million tonnes in 2014, representing a CAGR of -2.9%. In value terms, over the same period, the decline of the CAGR was -2.7%. This decline comes in the context of a constant increase in road freight transport volumes in Romania.

Source: NIS, Goods transport, by mode of transport (database), http://bit.ly/21a7Nxe (accessed on 26 January 2016).

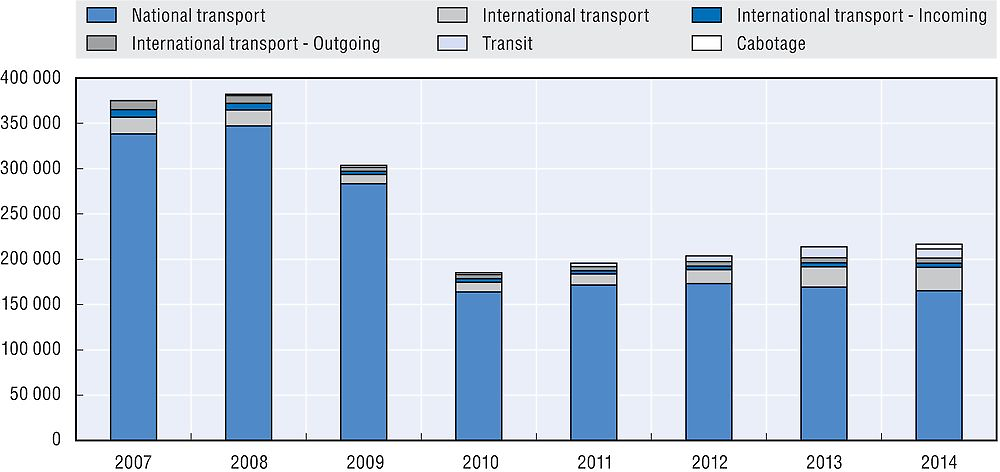

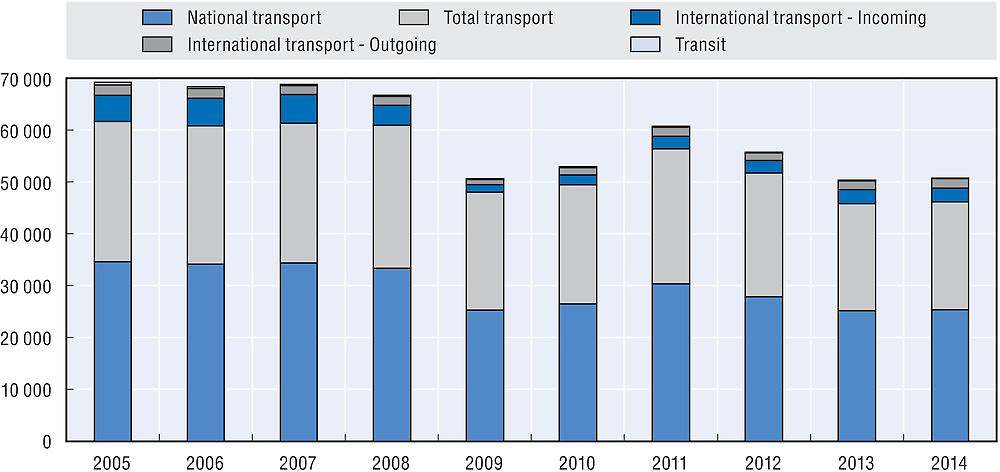

Figure 3.16 illustrates the structure of railway freight transport. National transport represents the biggest share (over 80%) of total freight transport. The poor state of the railway transport infrastructure and the high infrastructure access fees lead to insignificant volumes of international transit. Import and export represents a small part of the total railway freight transport – below 20% since 2008.

Source: Eurostat, Railway transport – Goods transported, by type of transport (database), http://bit.ly/1yussbN (accessed on 26 January 2016).

According to the NIS, the main categories of goods that were transported by rail in 2014 were: coal and lignite, crude petroleum and natural gas (35.71%), coke and refined petroleum products (29.51%), products of agriculture (6.42%), chemicals (5.52%), metal ores and other mining products (5.04%), basic metals (4.95%), non-metallic mineral products (2.74%) and wood and products of wood and cork (2.71%). Therefore, the major demand operators come from the following industry sectors: energy, agriculture and extraction.

International rail transport

International railway transport is negligible in Romania, compared to other European countries, confirming the weak attraction of Romania’s infrastructure for international traffic. This conclusion is in sharp contrast with the fact that Romania is located at the crossroads between three trans-European network corridors going from west to east and from south to north.34

Source: Eurostat, Railway transport – Goods transported, by type of transport (database), http://bit.ly/1yussbN (accessed on 26 January 2016).

Relevant government authorities

The following regulatory authorities are responsible for developing the rail freight national policy:

-

Railway Supervision Council (CSF) is the national authority monitoring railway service markets which intervenes when discrimination occurs notably with respect to access to infrastructure. The CSF may investigate, either on its own initiative or following a complaint, situations such as refusal of access or tariff discrimination implemented by the infrastructure administrator or railway transport operators. The CSF has authority to issue reasoned decisions and implement appropriate remedies.35

-

Romanian Railway Authority (AFER) is a technical body within the MoT, overseeing safety authorisations and licences related to the railway infrastructure administrator or rail transport operators. It also monitors the respect of the conditions needed for interoperability of the conventional and high speed trans-European railway system.36

-

Romanian Railway Licensing Body (OLFR) is the national authority designated for issuing licences for rail transport operators.37

-

National Centre for Railway Qualification and Training (CENAFER) is a national specialised body under the MoT, designed to ensure the regular professional training and testing of the staff carrying out typical activities in railway transport, in order to ensure safe conditions for circulation, transport security and railway services quality.38

Inland waterway and maritime freight transport

Definition

Water freight transport refers to goods transported on waterways by using various means such as boats, steamers, barges, ships, etc. Goods are carried to different places by these means both within and outside the country. When the goods are transported inside the country on rivers and canals, transport is referred as “inland waterway transport”. “Maritime transport” refers to movement of goods on ships on the sea and is carried out on fixed routes, linking a large number of origin and destination points in separate countries. Maritime transport therefore plays an important role in the development of international trade.

Ports in maritime and inland waterway transport serve as infrastructure to a wide range of customers including freight shippers, ferry operators and private boats. One of the main functions of ports is facilitating domestic and international trade of goods, often on a large scale.

Source: OECD (2011), Competition in ports and port services, http://bit.ly/1oDSwU2.

Some shipping services as well as shipping related activities taking place in ports are provided by the port administration under monopoly conditions, while others are subject to competition.39 Shipping related activities include safety services such as port pilotage and towing, activities related to ship operation40 and other shipping auxiliary activities.41

Infrastructure

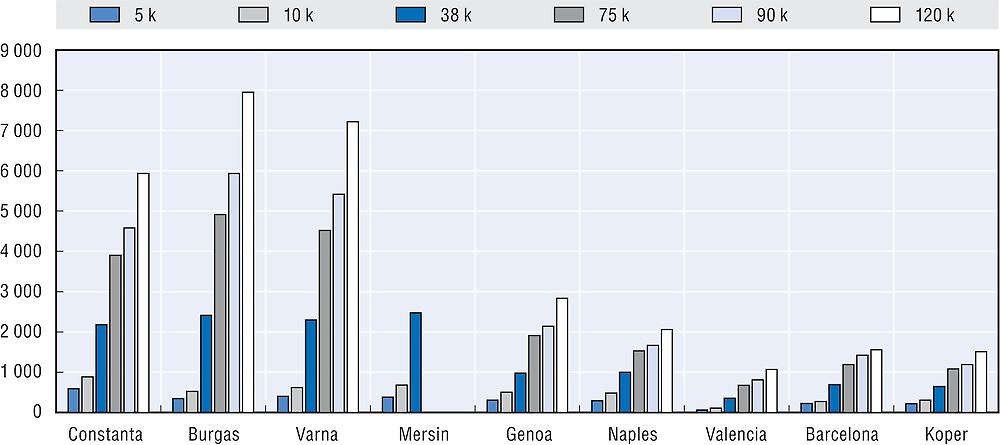

The naval infrastructure in Romania consists of maritime ports, river-maritime ports and river ports. There are three maritime harbours along the Black Sea, namely Consţanta, Mangalia and Midia. These ports are directly linked to the Danube-Black Sea Canal, which ensures connection between the Black Sea and the river Danube, the Poarta Albă-Midia Năvodari Canal and, indirectly, with the “Mihail Kogălniceanu” Airport located 20 km away from Consţanta.

The Port of Consţanta is the main Romanian sea port, playing a significant role as the transit node for the landlocked countries in central and south-eastern Europe. It has connections with all means of transport: railway, road, inland waterways and air. The volume of goods handled here represents more than 95% of the commodities handled in all maritime ports in Romania, with a total volume of 55.64 million tonnes in 2014 (of which 43.05 million tonnes corresponded to maritime transport and 12.58 million tonnes corresponded to river transport).42

The Port of Consţanta has gradually become one of the main distribution centres serving central and eastern Europe, having the fourth largest port surface in the EU, ranked just after Rotterdam, Antwerp and Marseille.43

The Port of Consţanta has also an advantageous geostrategic position, being located at the intersection of the Pan-European Transport Corridor No. IV, which goes from Dresden/Nuremberg to Istanbul (road and railway), with the Pan-European Transport Corridor No. VII, which connects the North Sea to the Black Sea by the Rhine-Main-Danube Canal. This port therefore links two European trade poles, Rotterdam and Consţanta, creating an inland waterway transport route from the North Sea to the Black Sea. In the southern part of the port, Consţanta also has a river area, which makes it a river-maritime port.

The Danube River can be divided into two structurally different sectors: the River Danube and the Maritime Danube. Several ports situated along the Maritime Danube, namely Brăila, Galaţi, Tulcea and Sulina, allow access for both river and maritime vessels, so they serve both international and inland transport. However, the lack of multimodal facilities for these ports represents a major obstacle in terms of alignment of port logistics to international transport, notably with respect to shipment of containers. Moreover, connections to national roads and rail networks are slow and inefficient. All these factors limit the volume of traffic operating in these ports.44

The inland waterway network is composed of the Danube, secondary navigable branches of the Danube and navigable canals. The navigable inland waterways have a total length of about 1 779 km, of which 1 647 are navigable rivers and lakes and 132 are navigable canals. The Danube River has a length in or along the border of Romania of about 1 075 km so is considered an important transport corridor. Romania has 30 inland river ports.45 Most of these ports have a poor infrastructure when compared to modern logistic requirements, with obsolete equipment, which prevents the efficient transport of goods. Also, these ports have inefficient connections with other transport modalities. These issues are reflected in the reduced volumes of cargo in these ports.46

According to the MoT Master Plan for the transport sector, investments are necessary to modernise and upgrade the Romanian inland waterway infrastructure. Indeed, following Bulgaria, Romania has the lowest investment rate on the Danube river infrastructure of all the Danube countries based on the length of its section of this river.47

Subsector characteristics

Maritime freight transport

Maritime transport is the most important modality of international freight transport in Romania. Approximately 60% of the goods imported and exported by Romania in 2014 were transported by sea, followed by road and inland waterways.

According to the NIS, in 2014 maritime freight transport generated overall revenues equal to EUR 75.3 million, with 284 people employed. In addition, in 2014 all shipping-related activities generated an overall value of EUR 366 million, with approximately 240 active firms and about 5 320 people employed.

As shown in the table below, freight shipping operations in Consţanta are mainly run by international shipping companies, whereas Romanian ship owners have gradually disappeared.

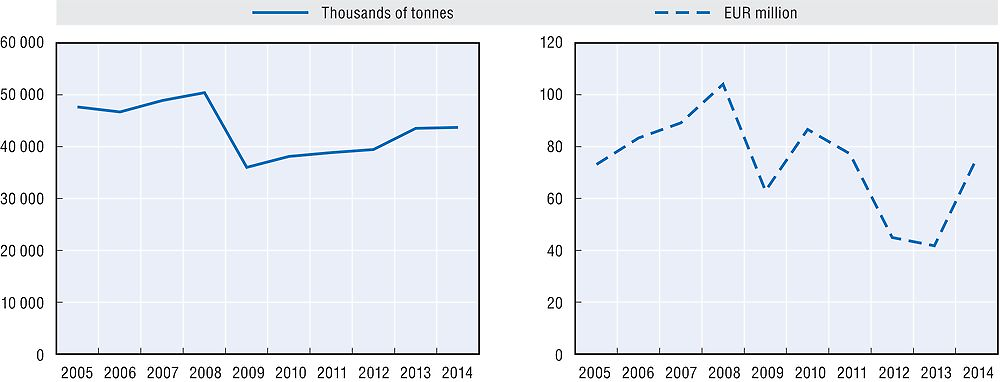

The maritime freight transport had a sharp decrease during the outbreak of the global financial crisis, reaching a positive evolution in terms of volume in the last five years, with a CAGR of approximately +4%. Figure 3.19 shows the evolution of maritime freight transport during the period between 2005 and 2014.

Source: NIS, Goods transport, by mode of transport (database), http://bit.ly/21a7Nxe (accessed on 26 January 2016).

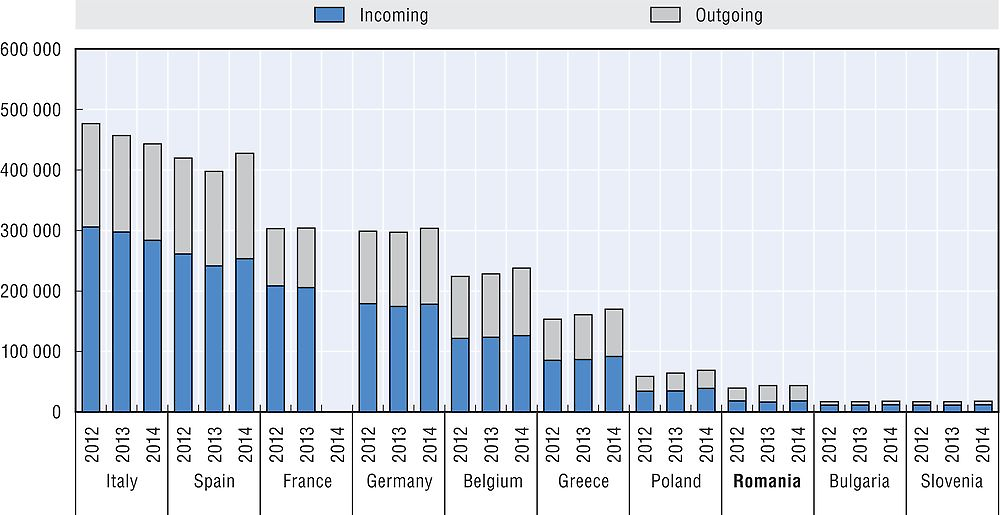

Figure 3.20 shows that Romania has suffered from the economic downturn which is reflected in the drop in imports. Since 2008, the volume of goods imported has been constantly decreasing.

Source: Eurostat, Maritime transport – Goods (database), http://bit.ly/1yussbN (accessed on 26 January 2016).

According to the NIS, the main categories of goods that were transported by sea in 2014 were: agricultural products (33.36%), coal and lignite, crude petroleum and natural gas (18.53%), coke and refined petroleum products (10.05%), metal ores and other mining and quarrying products (8.39%), basic metals (5.41%), chemicals (5.19%), secondary raw materials and municipal wastes (3.05%), wood and products of wood (1.34%), non-metallic mineral products (1.31%) and food products (1.24%). Demand is therefore coming mainly from the following industry sectors: agriculture, energy, extraction and chemicals.

Inland waterway freight transport

According to the NIS, inland waterways freight transport generated an overall value of about EUR 95.5 million in 2014. Employment in this sector reached 1 719 people in the same year. There are 90 active companies in inland waterway freight transport, of which 75 % have 1 to 10 employees, 15% have 11 to 50 employees, and the remaining 10% exceed 50 employees. The number of active firms active in inland waterway freight transport decreased from 112 in 2008 to 90 in 2014 and the employment recorded a decrease of -17% in the same period.

The major player in this sector is Compania De Navigaţie Fluvială Română NAVROM S.A., with an annual volume of over ten million tonnes of goods transported. NAVROM operates towards both internal routes such as Galaţi, Consţanta, Cernavodă, Medgidia, Mahmudia, etc. and external routes such as Ukraine, Serbia, Hungary, Austria and Germany. NAVROM is the incumbent company in the inland waterway freight sector, having being privatised by the Romanian government in 1998.48

According to the NIS, the first ten inland waterway freight companies in 2014 were:

The above table shows a highly concentrated subsector in which the largest company, NAVROM, holds a market share of over 50%. Moreover, there is significant disparity between NAVROM’s market share and the remaining companies.

Figure 3.21 shows the evolution of inland waterway transport over the period 2005-14.

Source: NIS, Goods transport, by mode of transport (database), http://bit.ly/21a7Nxe (accessed on 26 January 2016).

After a fast recovery and a significant increase in inland waterway freight transport in 2010, the volume of goods handled by inland waterways registered a constant decline in the period from 2011 to 2014, with a CAGR of -3.4%.

On the Danube, three types of transport operate: i) internal, ii) transit and iii) import/export. International transport represents a significant share (28% in 2010, 20% in 2011, 33% in 2012, 36% in 2013 and 32% in 2014) of the total volume of goods transported by inland waterways. Transit has an important share (over 15% in the period between 2009 and 2014), showing that the Danube River is an advantageous transport modality and represents an efficient alternative to rail and road transport.

Source: Eurostat, Inland waterways transport by type of vessel (database), http://bit.ly/1yussbN (accessed on 26 January 2016).

According to the NIS, the main categories of goods that were transported in 2014 by inland waterways were: metal ores and other mining products (44.97%), products of agriculture (31.18%), coal and lignite, crude petroleum and natural gas (8.09%), chemicals (5.69%), coke and refined petroleum products (4.7%) and basic metals (2.76%). Hence, demand is driven by the following industry sectors: extraction, energy, agriculture and chemicals.

International maritime transport

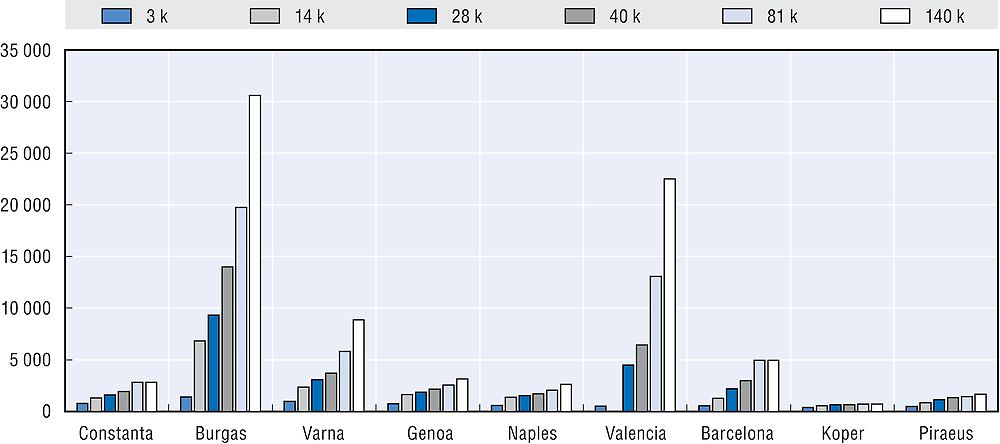

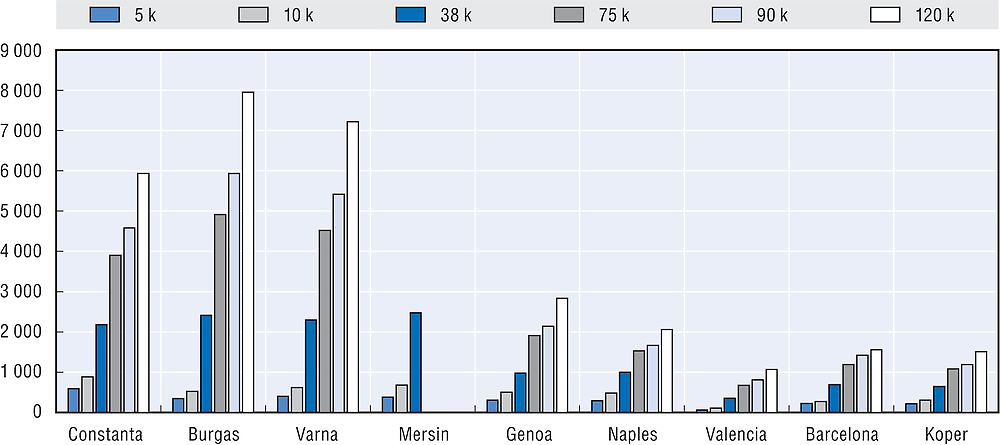

As shown in Figures 3.23and 3.24, inland waterway and maritime transport in Romania have not reached a significant scale.

Source: Eurostat, Inland waterways transport by type of vessel (database), http://bit.ly/1yussbN (accessed on 26 January 2016).

Source: Eurostat, Maritime transport – Goods (database), http://bit.ly/1yussbN (accessed on 26 January 2016). No data available for France, 2014.

Relevant government authorities

The MoT is the main authority responsible for regulation, authorisation, co-ordination and control in maritime and fluvial transport. The Ministry is also responsible for ensuring the functionality of harbours and other naval transportation infrastructure.

Under its subordination there are several entities with specific tasks:

-

Romanian Naval Authority (ANR) is the state authority responsible for navigation safety. Its main tasks are: elaboration and submission for approval to the MoT of draft legislation and binding rules; implementation of rules, regulations and international conventions in Romanian legislation; inspection, registration and recording of Romanian-flagged vessels; recording and certification of seafarers; technical supervision, classification and certification of ships.49

-

National Company Maritime Danube Ports Administration S.A. Galaţi works under the MoT and operates as port authority for the ports whose infrastructure was leased by the MoT, namely Galaţi, Brăila and Tulcea.50

-

National Company Fluvial Danube Ports Administration S.A. Giurgiu acts as port authority within its area of activity. It is responsible for managing the port land, harbour limits and port infrastructure established by MoT for the following river ports: Bechet, Călăraşi, Calafat, Cernavodă, Cetate, Corabia, Drobeta Turnu Severin, Giurgiu, Orşova, Olteniţa, and Moldova Veche.51

-

National Company Navigable Canals Administration S.A. Consţanta is a national company subordinated to the MoT which acts as port authority according to legal regulations and statutes along the Danube-Black Sea Canal and the Poarta Albă-Midia Năvodari Canal and in the ports located in this area.52

-

National Company Maritime Ports Administration S.A. Consţanta is a joint stock company assigned by the MoT to develop activities of national public interest in its capacity as a port administration. The company fulfils the port authority functions for Consţanta, Midia, Mangalia and Tomis Marina ports.53

-

Lower Danube River Administration Galaţi A.A. operates as an autonomous administration under the MoT and serves as a waterways authority on the Romanian Danube sector. Its main tasks are to ensure minimum depth navigation by providing dredging, ensuring coastal and floating signals, conducting topographic measurements, performing construction and repair works to ensure navigation conditions, ensuring pilotage of ships on the Danube stretch between Brăila and Sulina and in the ports situated in this sector and providing the water transport infrastructure to all companies in the sector.54

-

National Company of Naval Radio Communications “Radionav” S.A is a company that works under the MoT and provides radio communication services related to maritime operations and navigation safety.55

-

Romanian Maritime Training Centre (CERONAV) is a public institution that provides theoretical and practical training to staff of sea, river, harbour and oil platforms in accordance with national legislation, international regulations and training standards set by various accredited bodies. As a national body, CERONAV fulfils the obligations of the Romanian state arising from international conventions and agreements relating to staff preparation and training.56

-

Romanian Agency for Saving Life at Sea (ARSVOM) is a specialised technical body under the MoT, responsible for searching and saving human lives at sea and intervening in case of casualties generated by pollution.57

The main trade associations in the inland waterway freight transport are: Romanian Association of Inland Ship Owners and Port Operators (AAOPFR); Romanian Association of Ship owners; Romanian Ship Agents and Brokers Association; Romanian Naval League; and, Employer Organization “Port Operator” Consţanta.

3.2. Restrictions to competitiveness in road freight transport

The road freight sector has historically been a highly regulated sector. In the last decades many OECD countries have significantly liberalised their road freight sector. According to a report by the OECD (2000), “Competition Issues in Road Transport”, the results of the liberalisation have been almost entirely positive, such as reduction of operators’ costs, improved efficiency and innovative new services development. For example, in the United Kingdom deregulation has promoted the development of new types of logistics services, such as distribution contractors providing road haulage as part of an integrated package of logistics service.

The same study by the OECD finds that as of 1998, among the main remaining regulatory constraints in road freight were the complete prohibition of cabotage, pricing, or entry regulations enforced by professional bodies, price control, competition law exemption for road freight, criteria other than the technical, financial and safety criteria considered in granting a licence/permit/concession, regulatory competence to limit the capacity or the number of competitors and reservation of certain freight for rail transport.

Although in 2016 we did not find those obstacles identified within the Romanian road freight transport sector, Romania’s road freight industry remains one of the most regulated in the European Union, as shown in the economic overview (Koske et al., 2014).

Description of the European legal framework

Most road freight transport regulations in Romania are based on European legislation, as they either directly implement European regulations, or transpose European directives. The main pieces of European legislation are the following:

-

European Regulation No. 1071/2009 setting the provisions with which undertakings must comply in order to gain access to the occupation of a road transport operator.

-

European Regulation No. 1072/2009 on common rules for access to the international road haulage market lays down the provisions to be complied with by undertakings that wish to operate on the international road haulage market and on national markets other than on their own (cabotage). It includes provisions relative to the documents to be issued to such undertakings in order to obtain a Community licence. Finally, it also sets down provisions regarding the sanctioning of infringements and co-operation between Member States. The purpose of the regulation is to improve the efficiency of road freight transport by reducing the number of empty trips in international transport operations.

-

European Directive No. 96/53 laying down the maximum authorised dimensions for certain road vehicles circulating within the Community, the maximum authorised dimensions in national and international traffic and the maximum authorised weights in international traffic. The directive also ensures that Member States cannot restrict vehicles that comply with these limits from performing international transport operations within their territories.

-

Directive No. 2003/59/EC on the initial qualification and periodic training of drivers of certain road vehicles for the carriage of goods or passengers. As part of the overall effort to increase safety on European roads, the directive establishes the mandatory initial qualification and periodic training requirements for drivers.

Authorisations

Authorisations required for the provision of services might represent legal barriers to entry on the market. In general, authorisations should ensure consumer protection. However, often the requirements of authorisations are stricter than necessary for consumer protection and can unnecessarily reduce consumer choice. Also, they may make it more difficult, expensive and time-consuming for new companies to enter a market.

The authorisation for repairing, adjusting, reconstructing and dismantling of vehicles

Description of obstacle

Article 122 (m) of the Government Emergency Ordinance No. 195/2002 regarding the traffic on public roads states that the repairing, adjusting, reconstructing and dismantling of vehicles are to be undertaken only by authorised operators. The authorisation is granted by the Romanian Automotive Register (RAR), the technical specialised body designated by the Ministry of Transport (MoT) as the competent authority in the field of road vehicles, road safety, environmental protection and quality assurance.

In order to obtain this authorisation, vehicle repair garages must provide the following documents: i) a copy of the certificate, issued by the RAR, attesting the professional ability of the garage manager, ii) the “criminal record” of the economic operator’s manager, iii) a copy of the company registration certificate issued by the National Trade Register Office, iv) a copy of the tax registration certificate issued by the National Agency for Fiscal Administration, v) a copy of the certificate of incumbency issued by the National Trade Register Office with the corresponding activity field, and vi) a list of the equipment used for providing the service. The opening of a garage is subject to an authorisation tax with the amount depending on the number of technical activities planned to be carried out in it.

In addition, for the authorisation to be maintained, the vehicle repair garages must annually obtain a visa. The visa is granted by the RAR after checking the technical ability of the vehicle repair garages by verifying the existence and conformity of the equipment used for performing the garages’ activities. The vehicle repair garages must pay an annual tax for the abovementioned audit of their technical ability.

Harm to competition

The authorisation requirement constitutes an administrative burden that may reduce the number of operators and raise administrative costs.

Policymakers’ objective

The objective of the provision is to ensure public safety on the roads.

Legal frameworks from other European countries such as France, the United Kingdom and Spain do not require an authorisation in order to run a vehicle repair garage.

In France, starting up a garage is subject to proving the professional qualifications of the person who leads the activity of the operator. Such a person must possess a certificate of professional competence, a certificate of professional studies, a degree or the equivalent of a degree issued by a national directory of professional certifications, or have three years of relevant experience working in the European Economic Area.

Also, French legislation establishes the obligation of garages to be registered in the National Register of Professions. In order to be enrolled in the abovementioned register, the manager of the garage must have attended a preparatory course that is organised by the regional Chamber of Commerce and Industry.

For the registration, the manager of the garage must submit the following documents: i) a statement of intent to create the garage, ii) a statement concerning any (or no) criminal record of the manager iii) the certificate granted by the Chamber of Commerce and Industry attesting to the completion of the preparatory course, iv) a copy of the identity card of the manager.

In the United Kingdom, there seems to be no obligation for the manager of a garage or for the employees directly involved in repairing vehicles to pass an exam or to have a diploma in order to prove their professional qualifications. To convince customers that the garage is reputable, the garage owner joins a trade association with codes of practice that have been approved by the Trading Standards Institute or a trading-standards approved scheme such as “Buy With Confidence”. The membership inspection regime to which garages voluntarily submit ensures that they are monitored in terms of their premises, equipment, technical training, customer care and operation of the code of practice and of their individual ability to quickly remedy any problem, as it arises, to their customers’ satisfaction.

Recommendation

We recommend that the provisions be repealed. The obligation to obtain an authorisation in order to run a vehicle repair garage is disproportionate to the envisaged aim of public safety on roads. The quality of the repairs performed by the garages could be ensured by requiring the manager of the garage to possess a certificate of professional studies or a degree issued, for instance by the RAR, in case the manager does not have a certificate of professional studies. Also, the employees directly involved in repairing, adjusting, reconstructing and dismantling vehicles should have a certificate of professional studies.

Moreover, the policymakers’ objective – public safety on the roads – is supposed to be achieved through periodic technical inspection. According to Government Ordinance No. 81/200058 all vehicles and trailers must be inspected at regular intervals by the RAR or by bodies authorised by the RAR. The ordinance provides a basis for checking that vehicles throughout Romania are in a roadworthy condition and meet the same safety standards as when they were first registered.

Therefore, no authorisation should be required for the garage to operate. Instead, the garage should be checked by the RAR in order to prove that its manager possesses a certificate of professional studies or a degree issued by the RAR and that its employees have certificates of professional studies.

Certification of drivers

Description of obstacle

According to Article 1 of Annex 5 of MoT Order No. 1214/2015 on the approval of norms establishing the conditions for obtaining a professional attestation by road transport staff, in order to transport goods with vehicles exceeding the applicable dimension and/or weight limits, so-called “abnormal load transport”, drivers must obtain a certificate of professional competence. This provision only applies to drivers who use vehicles registered in Romania for transport.

An abnormal vehicle is one that due to its construction exceeds at least one of the maximum dimensions of axle, bogie or total weights (for unloaded vehicles) authorised by Directive No. 96/53/EC and national legislation. The legal dimensions and weights vary between countries, and between regions within a country.59

The abnormal load transport certificate for drivers is required in Romania in addition to the general certificate, called the “certificate of professional competence”.

Harm to competition

The professional certificate for abnormal load transport affects drivers and operators, provides less flexibility in replacing the drivers for these types of transport because an operator needs a driver with an additional certificate in order to transport goods in abnormal vehicles. Also, the provision increases the administrative burden of road transport operators. Moreover, the provision applies only to those drivers who perform transport operations with vehicles registered in Romania. Therefore, besides the additional cost and administrative burden, it discriminates in favour of foreign transport operators with drivers operating vehicles registered in other countries. We did not find a similar requirement in any other European Union Member States.

Policymakers’ objective

There is no official recital for this particular provision. However, it seems that the objective of the provision is to ensure public safety on roads.

The relevant Romanian provision exceeds the requirements of European legislation. Thus, in order to enhance road safety in Europe by ensuring a common level of training and the achievement of the necessary skills and competences for professional drivers, European Directive No. 2003/59 requires a mandatory initial qualification and periodic training for truck drivers, with both attested by the certificate of professional competence. The directive does not require an additional certificate of professional competence for drivers in order to carry out road transport of goods with vehicles exceeding applicable length or weight limits.

Recommendation

The provision requiring an abnormal load transport certificate for drivers should be abolished. Professional qualification requirements concerning abnormal load can be addressed in the initial training undertaken for obtaining the certificate of professional competence. In other EU Member States, such as the United Kingdom and Spain, there is no obligation to obtain a certificate of professional competence for “abnormal load transport”. Thus, the courses related to the abnormal load should be part of the general course. This abolition will harmonise Romanian legislation with that of other EU Member States.

Conformity certificates for superstructures fitted on vehicles transporting dangerous goods

Description of obstacle

Currently only one undertaking in Romania, IPROCHIM SA, is entrusted with issuing certificates of conformity with respect to superstructures fitted on vehicles transporting dangerous goods, and transporting packaging containing dangerous goods. The list, which includes only IPROCHIM, was issued by the Ministry of Economy (MoE) and approved by the Order of the MoE No. 971/2014.

Any undertaking aiming to perform the activity of issuing certificates must first submit a request to the MoE proving that it fulfills the conditions stipulated by Order No. 2737/2012 of the MoE.60

In our understanding, all these conditions are clear and non-discriminatory. Thus, theoretically, any legal person established in Romania and registered in the Trade Register who proves that they can perform specific tasks regarding conformity assessment and inspection of specialised superstructures, should be appointed and designated by the MoE as a certificate-issuing body.

The main shareholder of IPROCHIM SA is the MoE, which owns 72.99% of its shares. The ministry is also in charge of authorising the operators who wish to issue such certificates of conformity. This creates a certain conflict of interest resulting from the fact that the MoE acts as a regulator, operator, and the authority empowered to authorise operators. In practice, requests for authorisation have been submitted by undertakings interested in acting as a certificate-issuing body which did not receive an official response, although, according to Romanian legislation, the MoE should answer within 30 days of receiving an application.

Harm to competition

IPROCHIM SA currently holds a monopoly in the market, leading to higher costs for transport operators who need to obtain a certificate of conformity with respect to superstructures.

Recommendation

Given that the conditions for authorising the performance of this activity set forth in Order No. 2737/2012 of the MoE are clear and non-discriminatory, and considering that operators whose application was rejected or not answered may challenge this decision in court, no recommendation concerning the relevant provisions is given. However, the MoE needs to act in a diligent manner in the light of its potential conflict of interest when receiving requests for authorisations submitted by undertakings interested in acting as a certificate-issuing body.

Transport manager

Description of obstacle

Article 15 of the Methodological Norms approved by Order No. 980/2011 of the MoT,61 which regulates the criteria that must be fulfilled by an undertaking in order to become a road transport operator, both on its own account and for hire/reward, requires the applying undertaking to have professional competence. Undertakings shall thus appoint a transport manager who must have a certificate of competence, fulfill the requirement of good repute, permanently manage the transport activities of the undertaking and must be an employee, director, owner, shareholder or manager of the undertaking. Additionally, the transport manager must reside in the European Union. Finally, this article provides that a natural person can be a transport manager only within one single undertaking.

The requirements of the Romanian legislation are in line with European Regulation No. 1071/2009 – but the obligation of the transport manager to lead only one single undertaking is more stringent.

Thus, according to Article 4 of European Regulation No. 1071/2009, transport managers can either be direct employees or persons so closely linked to the business that they have a real, direct connection with the operator. They can also be independent third parties, such as transport consultants, in the case where the operator does not have a transport manager with a genuine link to the undertaking. According to Article 4 para. (2), a transport manager who does not have a genuine link to the undertaking may serve up to four separate transport operators, as long as their combined fleet does not exceed 50 vehicles. The European regulation provides that Member States may decide to lower the number of undertakings and/or the size of the total fleet of vehicles which the manager may manage.

However, even if the Member States can determine the maximum number of transport operators led by a manager, the Romanian provision makes no link to the total combined fleet of operators, which seems to be the relevant criterion.

Policymakers’ objective

There is no official recital for the provision. It should ensure the quality of transport manager services, since, if a transport manager works for several separate undertakings at the same time, he may not always be available to brief drivers (e.g. on the characteristics of the goods transported, or on the route to choose to avoid delays or additional charges) or to respond to the client’s demands.

Harm to competition

Romanian transport managers are prevented from expanding their business by covering more than one undertaking. This also raises costs for Romanian undertakings, especially for the small ones, which must bear the cost of hiring their own transport manager.

Recommendation

We recommend modifying the relevant Romanian legislation by inserting the provision from the EU legislation, where transport managers can cover up to 4 undertakings and up to 50 vehicles.

More restrictive provisions than those in the EU regulation are not justified, notably due to the fact that Romanian freight hauliers generally have small fleets, so managers can carry out their tasks for more than one operator.62 If the restriction is lifted, the costs of the services performed by a transport manager may drop when he operates as an independent transport manager, and can provide services for more undertakings.

Local taxes

Description of obstacle

Local authorities in their capacity as managers of national roads that cross a municipality can impose additional taxes to those established by the government for using the Romanian national road network (the Romanian vignette).

Local and county councils also charge fees for the use of the local and county roads that they manage.

Harm to competition

These additional taxes increase the costs and administrative burden of road transport operators. There are frequent complaints that these taxes are not levied in a transparent manner and can lead to uncertainty and discrimination of some operators in relation to others. Also, it is difficult and time-consuming for freight hauliers to pay such taxes, as currently there is no efficient tax payment system in place.

As for fee transparency, access to information is often difficult. Most of these taxes are published on the websites of municipalities. However, in practice most of those websites are not well-organised. Also, often the decisions of the municipalities concerning the taxes are published together with other decisions, making it difficult to find them and to calculate the amount to be paid. Theoretically, for operators to find out whether they must pay a tax in a certain locality, they would need to study all local or county council decisions, as there is no official centralised system dealing with local taxes. As a consequence, road transport operators usually only learn of these taxes when they have to transit that locality and are being sanctioned by the competent authorities.

These taxes usually cannot be paid at major points-of-sale for road transport operators (e.g. gas stations), but only on the premises of city halls and county councils. To pay the fees, drivers are forced to leave their vehicles in a parking space and go to the city hall/local council during their operating hours. Generally, no 24/7 service is provided for fee payment, and fees cannot be paid by using a typical means of payment, such as the internet, telephone, etc. Thus, road transport operators in transit suffer a considerable disadvantage when compared to local transporters; they are often stuck in traffic until they obtain the authorisation, or become offenders for reasons difficult to control.

The absence of a transparent and efficient charging system leads to an additional administrative burden, and a differential treatment of market players.

The amount of local road taxes is sometimes even higher than the cost of the national vignette. For instance, the vignette for the national road network (totalling approximately 15 000 km) which consists of roads of normal European carrying capacity of 11.5 tonnes/axle and a total capacity of 40 tonnes, costs EUR 1 210 (RON 5 363) annually, compared to, for instance, Consţanta County, which has county roads with a lower carrying capacity totalling about 800 km in length and an annual fee of EUR 1 400 (RON 6 300).63 The fact that local fees are often much higher than the national vignette is also confirmed by the MoT in Romania’s General Transport Master Plan, issued in 2015.

Policymakers’ objective

The main objective of local taxes is the regulation of local traffic and to avoid congestion in municipalities. Taxes are also aimed at ensuring investment in the infrastructure and its maintenance and thus a high level of road quality and safety, providing drivers with an appropriate network of national, county and local roads.

Recommendation

We do not recommend abolishing local road taxes. However, we recommend that the Romanian government introduce an appropriate legal framework to ensure the transparency and efficiency of the payment system for local road taxes. Local authorities should also find a way to ensure transparency of the tax requirements, notably by making the application of these taxes more transparent for hauliers. County and local councils need to publish these charges and make them easily accessible since they are likely to apply not only to local operators, but also to operators coming from other regions of Romania, as well as from abroad. In particular, in order to ensure easy access for foreign operators, the information related to local taxes should also be made available in English.

To guarantee transparency of local taxes, a good measure might be to publish all road taxes on the websites of the MoT, and the Ministry of Regional Development and Public Administration. Also, an efficient payment system of taxes could be introduced through a new legal framework.

An efficient payment system might involve online payment or payment by mobile phone, as is currently implemented in cities such as London and Milan – but also in Romania. For example, payment for the toll bridge at the Feteşti-Cernavodă station on the A2 Bucureşti- Consţanta highway, introduced by Emergency Government Ordinance No. 8/2015 that ensures tax payment, is made by means of a closed-circuit television (CCTV) system, which records the licence plate of each vehicle entering and exiting the perimeter of the city.

Spare parts for tachographs

Description of obstacle

According to Order No. 181/2008 of the MoT,64 undertakings authorised to perform the installation, repair and/or verification of tachographs and speed limit devices must use only spare parts provided by the manufacturer of those tachographs and speed limit devices, or by suppliers appointed by the manufacturer.

Harm to competition

This provision is likely to eliminate other producers of spare parts for tachographs and speed limit devices. It may also raise costs for transport operators, as it prevents competition on the spare parts aftermarket.

Policymakers’ objective

There is no official recital for this particular provision. A speed limitation device is a piece of equipment used to limit the top speed of a vehicle. A tachograph is a device intended for installation in road vehicles to display, record, print, store and automatically or semi-automatically output details of the movement, including the speed of such vehicles, and details of certain periods of activity of the drivers. A tachograph, moreover, provides information to the road traffic inspection authority regarding the transport operators’ compliance with the regulations, mainly observance of working hours and possible overwork in the road transport industry. The regulation should ensure road safety and prevent accidents. Taking into consideration the importance of these devices for road safety, it is mandatory to eliminate every possibility of their manipulation by the operators. Sometimes, tachographs are manipulated to enable drivers to drive longer and take less rest. If the spare parts aftermarket were to be opened, it might lead to an increased risk of manipulation of these devices.

Moreover, even if the tachograph spare parts aftermarket were to be opened, its impact on competition and on the transport operators’ costs would be reduced as the tachographs generally have a longer life span than that of the trucks; because of this the volume of the spare parts aftermarket for tachographs is relatively small.

Recommendation

Even though this restriction is likely to exclude other producers of spare parts for tachographs and speed limit devices, and may raise costs for freight hauliers, the restriction seems proportional to the objective served, namely to promote road safety by avoiding the manipulation of these devices. Thus, no recommendation is made.

Waybills for transport and registration of incoming-outgoing wood material

European Regulation No. 995/2010, laying down the obligations of operators who place timber and timber products on the market, states that illegal logging is a pervasive problem within the European Union. “It poses a significant threat to forests as it contributes to the process of deforestation and forest degradation, which is responsible for about 20% of global CO2 emissions, threatens biodiversity, and undermines sustainable forest management and development. This also includes the commercial viability of operators acting in accordance with applicable legislation. It also contributes to desertification and soil erosion, and can exacerbate extreme weather events and flooding. In addition, it has social, political, and economic implications, often undermining progress towards good governance, and threatening the livelihood of local forest-dependent communities, and it can be linked to armed conflicts.”65 Combatting the problem of illegal logging in Romania has been a subject of ongoing concern in recent years.

Description of obstacle

According to Government Decision No. 470/2014 for the approval of Norms regarding the origin, movement, and sale of timber materials, the storage regime of timber materials, and the regime of round timber processing plants, as well as of measures for the implementation of European Regulation 995/2010. The undertakings that perform the activity of sale and transport of wood material must obtain specific waybills for the transport and register of the input-output of such materials. Both the waybills and the records are to be printed and sold only by the Imprimeria Naţională S.A., a state-owned company.

The waybills for the transport of wood materials are documents under a special regime, provided with specific security elements, are printed in blocks with 150 sheets, consisting of 50 sets of three sheets each, on carbonless copy paper, with the security elements applied on the first copy. The characteristics of the security elements contained in the waybills are established on the basis of a protocol with the Imprimeria Natională. The characteristics of the security elements are not made public. An Integrated Informational System of Tracking Wood Materials (SUMAL) was established for the traceability of timber harvested from the woods and to provide statistical information.

The waybill is issued by the operator who sells and transports wood material at the point of origin of transport. The operator must upload the standardised information in the SUMAL application, either online or using any electronic terminal that runs this application; this terminal must necessarily exist at the point of origin of the transport. The information uploaded refers among others to the series and number of the waybill for the transport of the wood materials, the point of unloading of the timber, the vehicle registration number and the species, type and volume of the timber. After receiving the information, SUMAL generates a unique code, as well as the date, hour, minute and second of the registration. The law requires that the unique code generated by SUMAL is written on the waybill. The unique code, as well as the date, hour, minute and second of the registration are also recorded in the register of input-output wood materials kept by the operator. The unique code attests to the legal origin of the transported timber. The registers of input-output wood materials are documents under a special regime they are printed in blocks with 100 sheets. The legal provisions do not stipulate whether the registers contain security elements.

Harm to competition

The provisions set up a monopoly in the printing forms of the waybills and the records of incoming-outgoing wood materials. The purchase of those required waybills and registers may therefore lead to higher costs for operators that sale and transport wood material.

Policymakers’ objective

The objective of the provision is to prevent illegal deforestation and smuggling of Romanian wood. However, the monopoly position held by Imprimeria Naţională on printing waybills and registers of input-output wood materials is not fulfilling the policymakers’ objective, namely to prevent illegal deforestation and smuggling of Romanian wood. Instead, this monopoly leads to higher costs for the operators who sell and transport wood material. The waybills also do not need to be printed with security elements as the unique code generated by the application SUMAL attests to the legal origin of the transported timber.

Recommendation

We recommend opening the market and allowing both the waybills and records of incoming-outgoing wood material to be printed by any company willing to perform such an activity.

Opening the market for the issuing of waybills for transport and records of incoming-outgoing wood materials, an activity which is currently performed exclusively by Imprimeria Naţională, should lead to a reduction in the price of waybills and records. The benefits arising from opening the market and liberalising the provision of this service are estimated to be worth approximately EUR 0.3 mln a year.

Geographic restrictions

Auditors of road safety

Description of obstacle

Law No. 265/200866 stipulates that the appointment of road safety auditors/inspectors is made for territorial areas and gives preference to individuals residing in those areas or close to those areas where the auditor/inspector needs to be appointed.

Road safety auditors/inspectors are professional individuals in charge of verifying road construction projects in terms of safety. They also periodically check the existing road infrastructure.

Harm to competition

These provisions create an entry barrier and favour auditors residing in the area where road infrastructure should be inspected in relation to auditors from other areas.

Policymakers’ objective

The law implements European Directive No. 2008/96 on road infrastructure safety management, which requires the establishment and implementation of procedures relating to road safety impact assessment, road safety audit, the management of road network safety, and inspections by Member States. Although the Directive stipulates the criteria for the appointment of road safety auditors, it makes no reference to territorial criteria.

There is no official recital for these specific restrictions. However, this may be necessary in order to make the deployment of auditors/inspectors’ activities more efficient in terms of costs and time.

Recommendation

This restriction exceeds the Directive No. 2008/96/EC requirements, and the appointment of road safety auditors/inspectors should not be linked to the geographical residence of the auditor/inspector. We recommend abolishing the provisions.

Additional tariffs

Description of obstacle

According to Government Ordinance No. 43/1997 on the road regime, as further amended and supplemented, managers of national roads apply tariffs in addition to the Romanian vignette to authorise access to the national road network for vehicles registered in a foreign country that is not a member of the European Union. These tariffs are established through bilateral agreements between Romania and third countries.

The provision authorises Romania to charge differential tariffs to third country hauliers as opposed to Romanian and EU hauliers. It may therefore lead to discriminatory treatment of third country hauliers.

Harm to competition

These provisions discriminate in favour of national and EU transport operators against those from a non-EU country.

Policymakers’ objective

During bilateral talks with third countries, Romania negotiates these additional tariffs together with the number of authorisations which are granted to third country hauliers, taking into consideration the interests of Romanian hauliers.

Recommendation

Even though this restriction is likely to create an entry barrier that discriminates against operators who are not members of European Union, it is our understanding that this restriction is justified for reasons of public interest. Thus, no recommendation for change is made for the specific provision.

Regulatory burden

Plate

Description of obstacle

Government Ordinance No. 27/2011 on road transport, as further amended and supplemented, provides that own-account transport operators, and transport operators who transport goods for hire or reward using a vehicle with a maximum permitted weight above 3.5 tonnes, are required to display on their vehicles a plate containing information related to the dimensions and maximum weight authorised for the vehicle. The plate must be displayed if vehicles do not have a manufacturer’s plate or the manufacturer’s plate does not contain the necessary information.

According to MoT Order No. 980/2011 if the vehicle has a trailer and/or a semi-trailer, it is necessary to have a plate for each trailer in addition to the plate for the vehicle.

In order to obtain the plate it is necessary that the dimensions and maximum weight of the vehicles, trailers and semi-trailers are established. This activity is currently performed exclusively by the RAR. According to the RAR website, there are two ways of establishing the dimensions and maximum weight: i) for vehicles without a towing device the dimensions and weight are established by the RAR based on the information from its database and the vehicle identity card and ii) for vehicles with a towing device, trailers and semi-trailers, the dimensions and weight are established by measuring them. In this case, each of them are measured separately. Thus, not all the vehicles are measured. However, in both the abovementioned cases, fees are received by the RAR.

Policymakers’ objective

In Romania as well as in Europe, heavy goods vehicles must comply with certain rules on weight and dimensions, for road safety reasons, and to avoid damaging roads, bridges and tunnels. These rules are established by European Directive No. 96/53 and Romanian legislation.67

The obligation to display a plate is required by Romanian law so that law enforcers can verify the compliance of the transport operators with the abovementioned legislation.

Harm to competition

Article 6 of European Directive No. 96/53 authorises Romania to opt for a regulatory system whereby information related to the vehicle’s dimensions and maximum weight is included on a plate. However, the same article from the directive stipulates that the information can also result from “a single document issued by the competent authorities of the Member State in which the vehicle is registered or put into circulation. Such a document shall bear the same headings and information as the plates.”

The requirement to display on vehicles a plate containing information related to the dimension and maximum weight authorised for the vehicle applies for all operators established in Romania. It represents an unnecessary burden for road transport operators and may also lead to a rise in costs for national operators compared to EU operators, who do not have such an obligation.

The total cost generated by the obligation to display such a plate on vehicles is approximately EUR 55 per vehicle. As mentioned above, if the vehicle has a trailer and/or a semi-trailer, it is necessary to have a plate for each, thus adding a EUR 55 charge for each additional trailer or semi-trailer. Approximately EUR 45 of this sum corresponds to the fee charged by the RAR for measuring the vehicle’s dimensions. The difference corresponds to the price of the plate. When the provision came into force in January 2014, in order to comply with the plate requirement Romanian transport operators had to purchase these plates, generating an estimated total cost of around EUR 6.3 million.

Recommendation

We recommend repealing this provision. The objective of the provision to verify the compliance of transport operators with the rules on weights and dimensions can be achieved through documentation, such as the vehicle identity card or the periodical technical inspection certificate, which should be carried by the vehicle driver. The vehicle identity card is the single document by which the vehicle is registered and put into circulation. It is issued by the RAR and contains the same headings and information as those appearing on the plate (the manufacturer’s name, identification number, dimensions and weight of the vehicle). The transport operator should keep the original vehicle identity card or a certified copy of it in case the operator is not the owner of the vehicle (for instance, in case of a lease). The periodical technical inspection certificate is issued automatically and free of charge by the RAR or by a body authorised by the RAR to perform periodical technical inspection. It is issued after the performance of the mandatory technical inspection that can include also measuring the vehicles. The periodical technical inspection certificate does not currently contain information referring to the vehicle’s dimensions and weight, but it can be inserted by the issuer. Both the vehicle identity card and the periodical technical inspection certificate should also be kept for trailers and semi-trailers. Carrying an identity card or a periodical technical inspection certificate by the vehicle driver would be in line with EU legislation regarding the vehicle’s dimensions and maximum weight.

According to our estimates, the benefits for road freight transport operators of abolishing the plate requirement for vehicles with maximum weight > 3.5 tonnes, would be approximately EUR 1.14 mln a year.

Copy of transport licence

Description of obstacle

According to MoT Order No. 980/2011 approving the Methodological Norms on the application of the provisions regarding the organisation and performance of road transport and related activities established by Government Ordinance No. 27/2011 on road transport, as further amended and supplemented, road transport operators must obtain a copy of the transport licence for each vehicle in their fleet, which must be renewed annually, although the road freight transport licence issued to transport operators is valid for a period of 10 years.