Chapter 4. Competition and extended producer responsibility

This chapter investigates the effect of EPR schemes on competition in markets. While consensus exists between different jurisdictions on how to assess these effects, there are also differences. Among other things, the chapter demonstrates widespread agreement that: i) EPR policies should be as pro-competition as possible, ii) monopoly should not be the default structure for producer responsibility organisations (PROs), iii) agreements among competitors to establish PROs should be assessed externally; iv) competition authorities should not distinguish between voluntary and government-sponsored agreements; v) waste collection, sorting and treatment services should be procured by transparent and competitive tender.

This chapter investigates the effect of EPR schemes on competition in markets. While consensus exists between different jurisdictions on how to assess these effects, there are also differences. Among other things, the chapter demonstrates widespread agreement that: i) EPR policies should be as pro-competition as possible, ii) monopoly should not be the default structure for producer responsibility organisations (PROs), iii) agreements among competitors to establish PROs should be assessed externally; iv) competition authorities should not distinguish between voluntary and government-sponsored agreements; v) waste collection, sorting and treatment services should be procured by transparent and competitive tender.

4.1. Introduction

The concept of “Extended Producer Responsibility” (“EPR”) has become a widely-established principle of environmental policy towards certain products. EPR may be promoted through a range of tools. These tools may affect competition in the markets for the products themselves as well as markets for waste management. How can EPR schemes be designed both to achieve environmental objectives and to protect competition in markets?

EPR makes producers responsible for the cost of managing their products once they become waste. EPR policies have been adopted in many OECD countries for packaging waste, electrical and electronic waste, batteries, tires and end-of-life vehicles. Pharmaceuticals, furniture, and agricultural-veterinary chemical containers are other examples. A take-back requirement imposed on producers appears to be the most commonly used instrument, with advance disposal fees and deposit/refund schemes used less frequently (OECD, 2013).

Competition laws in OECD and many other countries typically aim to promote economic efficiency, often along with other objectives. The laws define and prohibit anticompetitive conduct. Some also prohibit distortion of competition by state subsidy or state grant of exclusive rights. EPR policies have been the subject of competition authorities’ advocacy for more competition-friendly regulation. Companies and consortia engaged in the fulfilment of EPR have sometimes infringed competition law:

“The provisions most commonly examined by competition authorities concern limitations on independent collection and recycling services, quotas allocating recycled product to users based on historical market shares, and exclusivity-type provisions that prevent participants from dealing with third parties, thus preventing the development of rival waste management and recycling schemes.” (OECD 2010, p. 13).

The purpose of this chapter is to investigate the effects of EPR schemes on competition in markets. It follows up on the competition chapter of the 2001 OECD Guidance Manual for EPR.

The remainder of this chapter is structured as follows. The introduction describes the EPR measures, focussing on collective take-back systems. The second section briefly introduces the competition concepts that have been applied to EPR systems. The third section examines the competition issues that EPR schemes have or may generate in four markets – for the collective schemes, waste collection, waste recovery and disposal, as well as products. The last part identifies those areas where there appears to be consensus on how to address competition issues. It also identifies some areas where there are apparently differences in views. These differences can arise because of differences among competition laws, as well as among the products themselves.

4.1.1. EPR instruments

The competition concerns of collective take-back systems are the focus of this chapter. Two other EPR policies – advance disposal fees and deposit/refund schemes – are sometimes considered, too. A recent survey found take-back requirements to be the most common policy (72% of those EPR schemes surveyed) and applied to a wide variety of products. The other two instruments are used less frequently, 16% and 11%, respectively among those surveyed (OECD, 2013). A related concept, “product stewardship,” encompasses not only systems where producers have responsibility, but also where municipalities retain their waste management responsibilities and extend them to include recycling and reuse. In this paper, the term “collective take-back systems” includes systems where municipalities perform some waste management against payment from a collective of producers subject to EPR. In general, illegal collection, trade, recovery, and disposal of waste is not a subject of this paper; illegal handling can, if less costly than complying with laws, undermine legal markets and legally compliant businesses.

A product take-back policy requires “producers” in a jurisdiction (a term which includes anyone who puts a product on the market in that country) to take back the product at the end of its life. Product take-back is often accompanied by regulations that impose targets for reuse, collection or recycling. Take-back may be organised in different ways: Producers may take back the products themselves, or organise a cooperative system for doing so, or purchase the service. An advance disposal fee is an additional fee imposed at the point of sale; funds are used for disposal costs. A deposit/refund policy entails the purchaser paying a fee at the point of sale and, if the product is subsequently brought to a collection point, the fee being refunded.

EPR policies are not mutually exclusive, e.g. producers may charge an advance disposal fee to cover the cost of a take-back obligation. For example, with respect to waste collected from households, it is not uncommon for different fractions to be subject to fees, quotas on recycling, and bans on landfilling. Indeed, a well-established result in economics is that at least as many policy instruments – such as fees, quotas and bans – are needed as there are policy objectives – such as shares of different waste to be recycled or re-used (Tinbergen, 1967). Consequently, it is neither surprising nor inherently inefficient to subject waste streams to multiple instruments.

4.1.2. Markets and actors

EPR schemes may affect competition in several markets. One of these is the market for the organisation of systems or solutions to fulfil EPR obligations, that is, the market for PROs. Producer responsibility organisations (“PRO”) are frequently established to fulfil producers’ product take-back obligations. In some cases, a PRO may be created by groups of producers or waste management companies, or it may be an independent and unrelated company. A PRO frequently procures the services of waste collectors, sorters, and treatment companies, as well as monitors the fulfilment of the contracts so as to provide proof of fulfilment of the EPR responsibilities. Thus a PRO has several groups of users: producers, collectors, sorters, and treatment service providers. Alternatively, a PRO may procure some services, such as waste collection, from municipalities. The structure of markets for PROs differs; many are monopolies although some are oligopolies or competitive markets. PROs may or may not own the waste, a distinction that affects who gets the residual value of the waste. In some instances PROs themselves perform some waste management services, whereas in others they contract for the services. Differences between national legislation tend to make markets for PROs no larger than national.

A second set of markets are those for waste collection and sorting. These tend to be local up to national in scope, depending on what is collected and from whom. One option for collecting packaging waste subject to EPR from households is kerbside collection; a further option is to require households to deposit such waste at designated facilities. A third option is for informal but not illegal actors to collect recyclable waste. Kerbside collection of waste from households is usually a local natural monopoly in OECD countries. A natural monopoly is a market where the conditions of cost and demand imply it is cheaper for one entity, rather than two or more, to supply the market. Consequently, this kerbside collection service is often performed by a regulated private monopoly or a municipal monopoly. Collection from designated deposit facilities may exhibit different scale and density economies.

By contrast, the collection of recyclable waste from businesses tends to be subject to competition from a handful of rivals, that is, to be oligopolies. The geographic extent of these markets varies from local to at least national. E.g. markets for collecting waste lead batteries are national in Italy and Poland, local for end-of-life vehicles in the Netherlands, and provincial for recyclable materials from Dutch end-of-life vehicles. The geographic extent of markets for collection from businesses depends on a number of individual factors, including legal restrictions and transport costs.

Waste is sorted after it is collected from households. The sorting is done in relatively capital-intensive plants, which therefore enjoy scale economies. Experience suggests that the minimum efficient scale for sorting is larger than for collecting (see paragraph 106). That is, the scale at which the cost of sorting is minimised is larger than the scale at which the cost of collecting is minimised. Commercial packaging waste is usually sufficiently sorted at source and needs no further sorting. Sorted waste is often transported to a consolidation point, where the heterogeneous arriving loads are rearranged into homogenous loads and dispatched to be transported to specialised waste treatment facilities. A consolidation point enjoys economies of scope. This implies that a PRO established in one waste stream would find it easier to enter a new waste stream in the same geographic area than would a PRO without an appropriately located consolidation point.

A third set of markets are for waste recovery and disposal. The geographic extent of these markets may be national or even international, with inter alia legal restrictions, transport costs, and scale economies affecting their extent. For example, evidence from one case suggests that although international trade in end-of-life vehicles is restricted by legal barriers, spare car parts are increasingly traded internationally (European Commission decision No. 2002/204/EC (ARN) OJ L 68/18, points 17, 18, 72). Hazardous waste is subject to stricter international trade conditions than non-hazardous waste. The market in which secondary material is sold may also include primary raw materials: This appears to be the case for glass for containers and for lead.

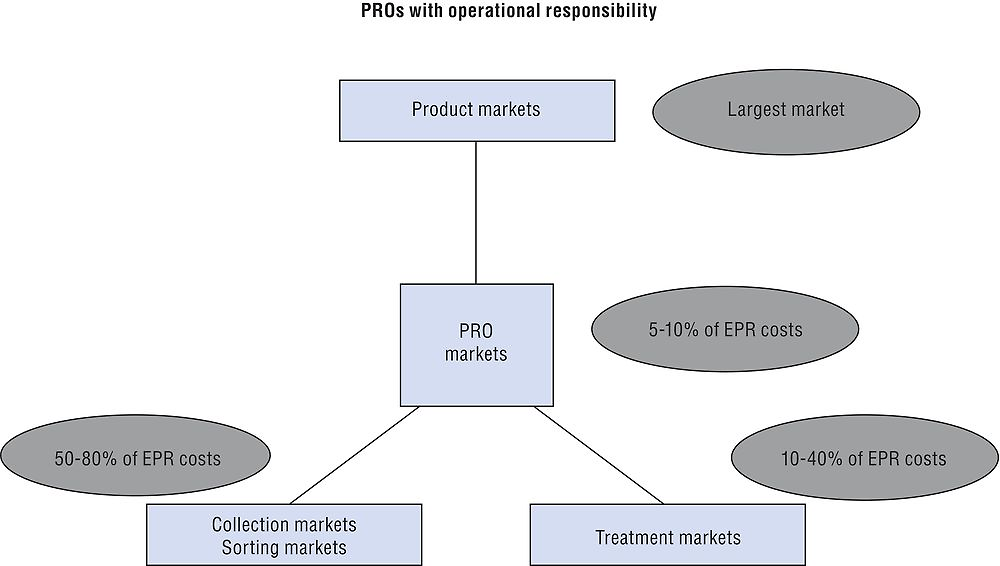

The three markets account for very different shares of the cost of handling waste for recycling or reuse according to EPR. One estimate is that PRO services approximately account for 5% to 10% of the total cost of EPR, whereas collection and sorting account for 60-80%, and recovery and disposal for the rest.1

A fourth set of markets are the product markets, that is, the markets for tyres or cars or consumer goods within packaging. The geographic extent of markets for products such as tyres, cars and electronics are usually national if not global. Suppliers to a product market may be of vastly different sizes. Depending on the waste stream, a given PRO may serve suppliers on many different product markets.

The relationship between these markets is a focus of this chapter. Figure 4.1 places these markets in relation to each other, and to the types of businesses or entities that act in them. If monopoly is the most efficient way to organise collection, then when is competition among PROs efficient? Are monopoly PROs subject to incentives to maintain competition in the markets where they procure services? When is it efficient for companies engaged in the different activities to contract exclusively with a single trading partner? Can competition in product markets be harmed by the conduct of PROs?

Note: In some countries collection, sorting and sometimes recycling is the responsibility of municipalities. As a consequence they decide with whom to contract for these services not the PROs.

4.1.3. The 2001 OECD Guidance Manual

The 2001 OECD Guidance Manual for EPR (OECD, 2001) identified a number of potential competition effects. Several of these concerned the effect on competition in product markets. First, to prevent a take-back obligation from serving as a barrier to entry into the product market, PROs need to be open to any producers of the products under a PRO’s purview. Indeed, the Guidance Manual warned against not only denial of access but also discrimination because of the potential for discrimination or denial to disadvantage certain competitors in the product markets. Such disadvantage could distort the product markets. Second, the Manual identified the risk that producers could use their co-operation in the context of a PRO as a cover for collusion regarding product markets. Relatedly, producers could use the PRO as a means to pass on unnecessary costs of the EPR programme, or they could attribute excess costs to the PRO in order to raise the price of products and recoup the funds as excess dividends in their role as joint owners of the PRO.

Some of the other potential competition effects identified in the Manual concerned the market for PROs, themselves. The Manual urged governments to keep the regulatory barriers to entry into the PRO markets as low as possible, for example by refraining from giving official status to one particular PRO. As an additional measure to limit PROs’ market power with respect to producers as well as with respect to sellers and buyers of collected materials, the Manual urged governments to allow for competition between PROs and producers’ individual arrangements.

Another set of concerns in the Manual was the effect of PRO procurement on competition in collection services. It urged PROs to use open, competitive and fair procedures, to sign contracts that are not excessively long, and to not preference municipalities or incumbents.

The Manual also identified potential competition concerns with respect to secondary or recycled materials. One concern was the possibility that excess material may be sold at “below market values,” harming competing recycled materials. A further concern was that mandates to preference local materials or that the specification to use particular materials could raise barriers to entry. The Manual also pointed out that requiring physical inspection of recycled materials can raise barriers to entry for recycled materials.

After more than a decade, the Guidance Manual’s competition concerns continue to be relevant. Experience shows that some of the identified concerns did indeed come to pass, as did unanticipated competition concerns.

4.2. Brief introduction to competition concepts

Competition laws apply to the behaviour of undertakings. The laws restrict inter alia what agreements may be entered into and what information can be exchanged and, for undertakings in a dominant position in a market, the conduct they may engage in. The laws typically prohibit mergers and acquisitions that lead or may lead to a restriction of competition. Competition laws in the European Union, but in few other jurisdictions, have rules on state aid: These rules govern state subsidies as well as the grant of exclusive rights. The interaction of competition laws with other, e.g. environmental, laws is governed by national legal frameworks.

Most competition laws aim to prevent reductions in consumer welfare. Competition often leads to lower prices, increased variety or more innovation, each of which increases consumer welfare. Competition law aims to prohibit conduct that impedes competition, while subject to national frameworks as to how to take the objectives of other laws into account. National competition laws often have other objectives, too, and these vary from one jurisdiction to another. Although most competition assessments consider only economic costs and benefits, some competition laws include a general public interest objective, and in at least one jurisdiction this enables environmental costs and benefits to be taken into account.

Competition laws in many jurisdictions, including the European Union and United States, apply to undertakings regardless of their ultimate ownership – state, municipal or private – or profit/non-profit status. Under EU law, for example, any entity engaged in an “economic activity” is subject to competition law.2

The “relevant market(s)” is a fundamental concept in competition law and policy. It is a conceptual tool to structure the identification of the competitive constraints to which a firm or firms involved in an investigation are subject. When the competition concerns centre on a firm’s supply – rather than purchasing – conduct, the competitive constraints include other firms that supply goods or services which customers consider to be good substitutes. Relevant markets are defined anew for each competition investigation. For the purposes of this chapter, a relevant market is a collection of products that are sufficiently close substitutes that customers switch among them and their suppliers compete. “Market” is used here, more loosely, to refer to collections of relevant markets that have something in common, such as physically similar services, even if those services are provided in different geographic areas. Also, “markets” are where transactions occur; they punctuate the physical process. Here, if it is relatively common for transactions to occur at a particular stage in the physical process, a “market” is referred to.

Certain terms recur in this chapter, and it may be useful to define them. A monopoly is a single supplier to a market. Compared with perfect competition, a monopoly will set higher prices, produce a lower output, and earn above-normal profits. It may also have less incentive to minimize costs or adopt new technology. A firm free-rides when it benefits from the actions of another without paying or sharing the costs. Free-riding could be inadvertent, e.g. when a consumer buys a product subject to EPR from a foreign supplier, but neither consumer nor supplier pays for the waste handling. One definition of a barrier to entry is a factor that prevents or deters the entry of new firms into a market despite the incumbents earning excess profits. (OECD, 1993, paragraphs 134, 91 and 14) A change in cost is with reference to an unchanging good or service; if the quality declines but nominal cost remains the same, the cost has risen.

The next three sub-sections briefly describe three aspects of competition law and policy: The assessment of agreements and of single-firm conduct, and, for European countries, state aid rules. Mergers are not addressed here since the EPR context does not seem to present unique issues and merger assessment is well described in guidelines issued by the various authorities. The final subsection briefly addresses how competition laws interact with other laws.

The third main section of this paper describes the competition concerns that have arisen or may arise in EPR schemes. Examples illustrate the application of several aspects of competition laws. They also illustrate the differences among assessments of agreements between competitors as well as in the trade-offs between environmental and competition objectives.

4.2.1. Agreements

Agreements are categorised by the relationship between the parties involved. Agreements among competitors – horizontal agreements – are generally considered a greater risk to competition than agreements between suppliers at different links along the supply chain – vertical agreements. Agreements between competitors about price, the allocation of markets or customers, and bid-rigging – collectively termed “hard-core cartels” – are generally presumed to be anticompetitive. The exchange of information that could help to form or monitor a cartel is also generally viewed as anticompetitive. However, an agreement among competitors may also generate economic benefits, and analytical frameworks have been developed to aid the assessment of effects on competition under these circumstances. In the competition law context, “agreement” has a broad meaning well beyond a signed document and, in some jurisdictions, includes tacit understandings.

An agreement among producers to establish a PRO to fulfil producers’ EPR would usually be assessed as a joint venture to provide waste management and recycling. In contrast to hard-core cartel agreements, these agreements are assessed on a case-by-case basis, examining the facts of the individual situation to make an overall assessment. In many jurisdictions, these agreements are assessed under a two-step analytical framework, first to determine whether the agreement is anticompetitive, second to assess proponents’ evidence that the benefits from the agreement outweigh the negative effects, and that these benefits could not be achieved by less anticompetitive means.3

An example of a two-part analysis is contained in one of the two central competition articles in the law of the European Union, Article 101 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (“TFEU”). The EU competition law is particularly relevant since many EPR agreements concern markets within the European Union. Article 101(1) prohibits anticompetitive agreements and decisions of associations of undertakings. If an agreement is found to violate Article 101(1), then Article 101(3) becomes relevant. Its purpose,

“[I]s to determine the pro-competitive benefits produced by that agreement and to assess whether those pro-competitive effects outweigh the restrictive effects on competition. The balancing of restrictive and pro-competitive effects is conducted exclusively within the framework laid down by Article 101(3). If the pro-competitive effects do not outweigh a restriction of competition, Article 101(2) stipulates that the agreement shall be automatically void.” (European Commission, 2011, para. 20, footnotes omitted).

Although many jurisdictions follow a two-step analysis, they differ in what benefits they take into account. For many OECD jurisdictions, the benefits must be economic, e.g. cost savings, better quality, greater variety or faster innovation, and they must accrue to the users of the good. For example, better waste management has been included in the concept of “technical or economic progress,” one of the pro-competitive benefits listed in Article 101(3), in the VOTOB and DSD decisions, described below. By contrast, the competition laws of a few jurisdictions apply a public benefit standard that recognises non-economic benefits and detriments, such as environmental damage, that accrue to non-users of the good.4 Where costs – such as restrictions of competition – are significant, this raises questions of how to measure non-economic detriments such as environmental damage, and whether the competition authority has the expertise to do so (OECD 2010).

Horizontal agreements in the United States

Two other large jurisdictions, the United States and Canada, follow different processes. An agreement among competitors is, under the United States antitrust laws, first assessed as to whether it falls into the category of agreements that are illegal per se (US FTC and DOJ, 2000). Agreements in this category always or almost always raise price or lower output, so do not warrant investigation. Agreements to fix prices or output, rig bids, or to allocate customers, suppliers, territories, or lines of business are examples of agreements in this category. All agreements falling outside the illegal per se category fall into the category of those assessed under a rule of reason. This is a factual inquiry into the agreement’s overall effects on competition. The inquiry is flexible, depending on the nature of the agreement and the market circumstances.

Rule of reason analysis compares the state of competition with the agreement to the state of competition absent the agreement. The main question is: Does the agreement increase the ability or incentives profitably to raise price, lower output or quality, or delay innovation?

In the first stage of a rule-of-reason analysis, the absence of market power and the nature of the agreement can lead to the conclusion that the agreement is lawful. Market power for a seller is the ability to raise price above the competitive level for a significant period of time. Market power is unlikely if the cumulative market share of the parties to the agreement is small or if conditions of entry make it likely that a new entrant can compete effectively. Some agreements concern matters that have little effect on competition. By contrast, if harm to competition is evident from the nature of the agreement or if the agreement has already caused harm to competition, then the agreement is unlawful.

If the initial examination indicates there may be competition concerns, then the agreement is examined in greater detail. If this more-detailed examination finds that there is no potential for harm to competition, then the agreement is lawful. In the opposite case, then the question is whether the agreement is “reasonably necessary” to achieve “cognizable efficiencies.” “Cognizable efficiencies” are efficiencies that have been verified by the [competition] Agencies, that do not arise from anticompetitive reductions in output or service, and that cannot be achieved through practical, significantly less restricted means” (US FTC and DOJ, 2000). “Reasonably necessary” does not imply “essential”. Finally, to assess the overall competitive effect of an agreement, the magnitude and the likelihood of both the anticompetitive harms and the cognizable efficiencies are considered.

Environmental costs and benefits, like other non-competition public policy objectives, do not enter into the analysis.

Horizontal agreements in Canada

Canadian competition law divides agreements among competitors into two categories corresponding to, respectively, Sections 45 and 90.1 of the law (Canada Competition Bureau, 2009). In the first category are those that fix prices, allocate markets, or restrict output. These are illegal per se. However, an agreement in the first category may benefit from the ancillary restraints defence if it is directly related to, and reasonably necessary for giving effect to, a broader, lawful agreement. It need not be the least restrictive alternative to promote the objective of the broader agreement to qualify for this defence.

The second category of agreements consists of other forms of competitor collaborations. These are prohibited only if they are likely to substantially lessen or prevent competition. An agreement is assessed on the basis of a factual investigation. If it is anticompetitive, then it is illegal. However, if cost savings and other benefits from efficiency gains are “greater than and offset” any anticompetitive effects from the agreement, then the agreement is legal. Like in the United States, cost savings from reductions in output, service, quality or variety, or gains that are merely redistributive, or gains that will be attained if the agreement is prohibited or ordered to be modified, are excluded from consideration.

This brief description of how agreements among competitors are assessed under three different competition laws illustrates their subtle but important differences. Where, for example, competitors agree to charge a small fee to pay for recycling, these differences can generate different decisions on whether the agreement is legal.

Vertical agreements

Vertical agreements are assessed, under most competition laws, for their effects on consumers and competition on a case-by-case basis.5 Vertical agreements usually facilitate better co-ordination by suppliers of complements, to the benefit of consumers. However, they may exclude, or significantly weaken competition from, rivals. In the context of PROs, a PRO may enter into a network of parallel vertical agreements with a number of other, e.g. collecting, companies. Some vertical agreements require one party to deal exclusively with the other. An exclusive agreement can give incentives for parties to make efficiency-enhancing investments. On the other hand, an exclusive agreement or network of such agreements can harm competition: This can occur if rivals need access to products that are unavailable for long periods due to the exclusive agreements. There is a greater risk of harm if a large share of the market is foreclosed, the exclusive agreements have long durations, and simultaneous entry into both markets is difficult (ICN, 2013).6 Several cases have considered the competition effects of dominant PROs’ networks of exclusive agreements.

To summarise, horizontal agreements to fix price, allocate markets or customers, or rig bids – collectively called “hard-core cartels” – are generally presumed to be anticompetitive in many competition laws. The exchange of information that can help to form or maintain a cartel is also anticompetitive. But a horizontal agreement, for example, to establish a PRO to provide waste collection and recycling that did not exist earlier, would generally be assessed on the basis of its overall effect. The case-by-case assessment of the specific facts of the agreement and its context would aim to identify the agreement’s likely benefits and detriments. Jurisdictions differ in terms of which benefits and detriments can be considered. Vertical agreements are assessed on a case-by-case basis; although they usually generate cost savings to the benefit of consumers, they can nevertheless harm competition and consumers in some circumstances.

4.2.2. Single-firm conduct

The conduct engaged in by a single undertaking, acting alone, may violate competition laws. The terminology differs between laws e.g. “abuse of dominance” in European countries, “monopolisation” in the United States and “misuse of market power” in Australia, among others. The definitions also differ, although they all require at least that an undertaking have significant market power, which could be indicated by having a persistently high share in a market that is difficult to enter. An undertaking in a dominant position that abuses its dominance violates competition law. Whether conduct is abusive or not is determined case-by-case. Most often, abuse consists of conduct that excludes competitors or that increases the difficulty of market entry, although exploitation of customers, e.g. excessive pricing, constitutes an abuse under some competition laws. In order not to deter competition, “abuse” is not defined too broadly.

4.2.3. State aid

State aid, or government subsidy, as well as exclusive rights, may distort competition by allowing inefficient firms to remain in a market or to supply more to a market than they otherwise would.

Article 107(1) TFEU defines state aid as, “[A]ny aid granted by a Member State or through State resources in any form whatsoever which distorts or threatens to distort competition by favouring certain undertakings or the production of certain goods,” with a requirement that it affect inter-State trade. In the context of EPR instruments, in particular advance disposal fees, a key question is whether the charge is compulsory (European Commission, 2012, para. 34-35). Even if funds are administered by a private consortium that is independent of public authorities, if the funds are financed through compulsory contributions and managed according to legislation, then they are considered to be State resources within the meaning of the state aid rules. This point is relevant in two decisions involving advance disposal fees for environmental purposes, one on meat and the other on new cars.7

The process by which the level of fees is determined could also affect whether an advance disposal fee constitutes state aid. The service for which compensation is received has to actually be performed, the compensation cannot exceed what is necessary to cover the costs, and the way the compensation is calculated has to be established in advance and be objective and transparent. The level of “necessary costs” may be determined through the use of a public procurement procedure or by an analysis of the costs of a well-run, typical undertaking, including reasonable profit (European Commission, 2012, para. 42-43).

A threshold, EUR 200 000 per undertaking over any three year period, can eliminate state aid concerns for very small schemes (European Commission, 2012, para. 41).

In summary, state aid rules aim to ensure that subsidies and legal monopolies do not distort competition. State aid is not generally a topic in competition laws outside the European Economic Area, which includes the EU, or EU candidate countries.

The next topic, however, arises in every jurisdiction with a competition law: How can other social objectives and competition objectives accommodate each other?

4.2.4. Competition as one of several laws

National legal frameworks govern how laws with different objectives, such as environmental and competition laws, interact. In European Union countries, the interaction with Union-level competition law is also relevant. Conflicts in a particular case can be resolved by pursuing, for example, the environmental objectives in the least anti-competitive way.

When examining an instance where, for example, environmental law affects the conduct of an undertaking, a key distinction is made between conduct that is allowed and conduct that is compelled by the environmental law. In many jurisdictions anticompetitive conduct can be shielded only if the “other” law requires the anticompetitive conduct, or precludes any other conduct.8 Advocacy for competition during the preparation of legislation or other policy measures can influence the design of those measures to achieve the policy objectives at lower cost to competition.

An undertaking that performs a public service is, like other undertakings, subject to competition laws. Within the European Union, Article 106(2) TFEU addresses the situation of undertakings operating services of general economic interest or that have been granted a revenue-producing monopoly. Member States may not enact measures contrary to inter alia the competition rules. These undertakings are subject to the competition rules insofar as the application of the competition rules does not obstruct the performance of their assigned tasks. Legislation must define the obligations of the undertakings and of the authority granting the special task (European Commission, 2012, para. 51).

An Italian case illustrates the resolution of a conflict between competition and a public service law. Article 8, 2 of Law 287/90, says that the provisions of the Italian competition law,

“…do not apply to undertakings which, by law, are entrusted with the operation of services of general economic interest or operate on the market in a monopoly situation, only insofar as this is indispensable to perform the specific tasks assigned to them.”

The competition authority had found that COBAT, the consortium for collecting used lead batteries, had infringed the competition law through inter alia allocating quotas of used batteries to recycling companies. The First Instance Administrative Tribunal found that COBAT had been established to serve public interest objectives and thus its conduct fell under the provision cited above. Upon further appeal, the Council of State found that the restrictions on competition were not indispensable to the public interest objectives, and thus confirmed the infringement (OECD, 2010, pp. 64-5).9

The OECD Council Recommendation on Competition Assessment (2009) says, in the section on revision of public policies that unduly restrict competition, that “Governments should adopt the more pro-competitive alternative consistent with the public interest objectives pursued and taking into account the benefits and costs of implementation.”

4.3. Experience with competition in EPR

EPR schemes can affect competition both in waste management markets and in markets for the products subject to EPR. This section describes and illustrates many of the competition issues that have, or may, arise. Following along the scheme outlined in section 4.1, markets for PROs are addressed first, followed by markets for waste collection and for waste recovery and disposal. The final section focusses on markets for products, e.g. tyres, cars, and batteries. Product markets can have very large volumes of trade, and harm to competition in these markets that raises price – or reduces quality or choice – by only a small amount can imply large losses of consumer welfare.10

Although not a complete inventory of EPR schemes, the extensive list compiled by Kaffine and O’Reilly (OECD, 2013) indicates that EPR schemes are used more commonly in European and North American countries than elsewhere. Of the 385 schemes listed, 167 are at a national level in Europe and 179 in Canada at the provincial or federal level or in one of states of the United States. Of the 284 take-back schemes, the corresponding figures are 144 and 115, respectively. Nevertheless, the experience with competition cases involving EPR schemes appears to be largely European, with some cases from other jurisdictions. The reason for this disparity is not clear. Reflecting this disparity, much of the discussion of experiences focuses on markets within Europe.

4.3.1. PRO markets

PROs fulfil producers’ EPR by organising inter alia the necessary collection, sorting and treatment of the specified waste. A PRO may be a monopoly, or it may compete against other PROs. Producers may also organise the fulfilment of their own EPR, but this is uncommon in practice. Many PROs were originally organised as monopoly joint ventures, fulfilling EPR for all producers selling specified products into a given country. This section first addresses some of the factors that influence whether monopoly or competition are more efficient. Three arguments that are often put forward to support monopoly for PROs are that the activity enjoys economies of scale, that a monopoly makes it easier to control free-riding, and that a monopoly is easier for regulators to oversee. But monopolies are subject to diminished incentives for efficiency and, where a monopoly service is legally required, buyers who have no choice but to deal with the monopoly can be exploited. This review of the arguments for and against monopoly is based largely on theory; the empirical experience comparing competition and monopoly among PROs in similar markets is limited to the few instances where competition replaced monopoly. If competition provides better outcomes than monopoly, then high barriers to entry or high switching costs can protect a monopoly or dominant firm. These are the second and third topics of this section. If it is difficult for new PROs to enter into competition with the incumbent(s), then competition may not develop. If any type of user – producers, collectors, sorters or treatment providers – finds it difficult to switch to a different PRO from its current PRO, then competition is dampened directly and, by making entry more difficult, indirectly. Conduct that raises barriers to entry and switching has been subject to competition proceedings.

They key insights into the competition concerns that PRO markets have generated are the following:

-

The first is linked to the question of whether and when a monopoly PRO is the most efficient way to organise the fulfilment of EPR. The cost of handling waste packaging in Germany fell significantly with the introduction of a number of changes including competitive bidding for collection and sorting, as well as competition among PROs and competition to supply services to PROs. Some argue that the quality fell as well. However, studies comparing PRO market structures in different countries and waste streams do not provide a clear answer, and the individual characteristics of markets likely lead to different answers. Key arguments concern scale economies, suppression of producer free-riding and regulatory oversight. A different argument – that temporary monopoly may be necessary to induce investment – may apply at the outset of an EPR scheme, particularly where future costs and revenues are very uncertain.

-

Second, competition in PRO markets can be suppressed by difficult conditions of entry by rival PROs. Some of these may be structural, but others may be strategic, i.e. entry being made more difficult by the conduct of incumbent PROs. Competition investigations have identified long-term exclusive contracts with waste collectors as raising barriers to entry. Sharing of collection infrastructure has been identified as one way to make entry easier, including entry at national scale. Prohibiting contracts with collectors that are long-term or exclusive are another way.

-

Third, difficulty in switching PROs can harm competition among PROs. The cost of switching can be influenced by inter alia vertical integration, the structure of fees, long-term exclusive vertical agreements, and non-portability of financial reserves.

-

Finally, although the experience to date is limited, clearing rules can directly affect competition among PROs.

Monopoly

Whether EPR for a set of products is most efficiently implemented by a monopoly depends on a number of factors. Each case is different, but some factors to consider are whether the activity benefits from significant economies of scale, and how the number of PROs affects the cost of free-riding and cost and effectiveness of regulatory oversight. In general, the main argument against monopolies is that they are often economically inefficient: Being free of competitive pressure – the risk that users will switch to a better offer – monopolies tend to be slower to seek more user-friendly solutions or lower costs, and are under less pressure to pass cost savings on to customers. It is unfortunate that the question, under what conditions are monopoly PROs more efficient than competitive ones, cannot be answered empirically. Although data has been collected, too many important cost factors differ among waste streams and countries to answer the question.11 In line with the Council Recommendation on Competition Assessment quoted above, many competition authorities take the view that any restriction on the establishment of multiple PROs or on new entry should be examined critically during the design phase, and if any restrictions are put into place, they should be phased out as soon as possible12 (OECD, 2013, p. 126).

Where producers jointly establish a monopoly PRO to handle their EPR, the PRO can be viewed as a joint venture to produce an input. An input production joint venture (“IPJV”) would normally be assessed under competition law on a case-by-case basis, as described above. Although there are potential cost savings, economic theory also points to potential negative effects: An IPJV may be used as a tool to enable the parent companies to charge cartel prices, or parent companies may free-ride on the efforts of others, resulting in inefficiency of the IPJV.13

This section finds that three arguments are often put forward to support monopoly in PRO markets, and a fourth argument in favour of temporary monopoly. These are: 1) the activity exhibits significant economies of scale compared with the size of market demand, 2) monopoly makes it cheaper to limit free-riding by producers, 3) monopoly makes regulatory oversight cheaper, and 4) temporary monopoly gives greater incentives to make risky investments.

Where there are significant scale economies, e.g. for some collection, this need not imply monopoly along the entire supply chain: Collection infrastructure may sometimes be shared, or allocated to different PROs at different periods. The amount of free-riding depends on both the incentives to engage in it and to suppress it. The benefits of free-riding would be lower if PRO fees were lower, which in theory is the case when PROs compete. Some of the methods used to suppress free-riding in PROs have been studied, but the studies did not allow a comparison of their effectiveness in monopoly versus competitive PRO markets. Regarding regulatory oversight, some direct costs may rise with more PROs, but so would the amount of information available to the regulator.

The arguments in favour of a temporary monopoly at the outset are somewhat different. If establishing a PRO incurs high sunk costs and there is uncertainty about the future costs and revenues of a PRO, then a temporary monopoly may be more efficient. Concentrating early-stage demand can reduce some of the uncertainty of a new venture. The consensus among competition authorities is that any restriction on the establishment of multiple PROs or on new entry should be examined critically during the design phase, and if any restrictions are put into place, they should be phased out as soon as possible (OECD, 2013, p. 126). In general, a monopoly not subject to economic regulation can exercise market power in the form of higher prices or lower quality, and is under less pressure to seek lower costs. These result in lower efficiency and lower consumer welfare.

Market power – monopoly and monopsony

The problem with monopolies stems from their not being subject to competitive pressure, that is, the risk that users will switch to a better offer. Even where monopolies are owned by their users, the absence of competitive pressure allows them to be inefficient (Ross and Szymanski, 2006). Where demand is obligatory, a monopolist’s market power is even greater since users cannot choose to do without (see example in Box 4.1).

The weakness of waste holders’ bargaining position vis-à-vis a monopoly was part of the analysis that led to the denial of a merger. The two lead collecting-and-recycling firms in Poland proposed to merge. The merger was found to be anticompetitive and denied. It was reckoned that the monopoly would have faced almost perfectly inelastic demand since the waste-holders had no alternative but to deal with the lead collector-recyclers at any price. Given this, the monopolist would have profitably raised price substantially (Acquisition of Baterpol Sp. z o.o. by Orzel Bialy S.A., 5 March 2009, cited in OECD, 2010, p. 81). Producers subject to EPR may have additional options not available to waste-holders in this market, so may be in a better bargaining position.

One consequence of weak competition is that suppliers do not pass on cost savings to buyers. Passing on any cost savings generated by the above-mentioned merger to waste-holders was considered “extremely doubtful.” In addition, monopoly collecting-recycling firms have little incentive for efficiency since they can recover any losses through higher fees. The Norwegian competition authority identified several examples where producer-importer owned collecting-recycling monopolies incurred excess costs and suggested this formed a pattern of inefficiency (OECD, 2006, p. 135). A further consequence of weak competition is that suppliers are under less pressure to adopt new, cost-saving technology. The adoption of better sorting techniques is attributed to opening of competition among German packaging PROs: “While new sorting techniques were already available during DSD’s monopoly, they became widely established only after competition was introduced” (OECD, 2013b, p. 107). In practice, however, it is difficult to estimate whether technological change is inefficiently slow or rapid.

Monopsony, or single buyers (typically the case of single PROs that procure services), generates analogous efficiency problems. Compared to a situation where they could negotiate with a number of potential buyers, suppliers facing a single buyer must accept worse terms. In the extreme, monopsony low prices can lead to suppliers exiting the market.

If self-provision of EPR were a feasible alternative for producers, then the threat of self-compliance might restrict the exploitation of market power by PROs. The Swedish competition authority investigated whether an individual firm could realistically satisfy its EPR without joining a PRO. It noted that PROs tended to be controlled by “the major actors in the market.” The investigation “found that the chances [of self-provision] tend to be either remote or non-existent” (OECD, 2006, p. 146). This finding suggests both that the self-compliance option places no meaningful restraint on the conduct by PROs, and that suppliers who compete against the major actors depend on their rivals for a necessary input.

In summary, a monopoly that is not subject to a real competitive threat – or regulation – can exercise market power by inter alia charging high prices and not tackling inefficiency. Such a monopoly is under less pressure to lower costs, to adopt cost saving technology, and to pass on any cost savings to users Similar arguments apply to single buyers, or monopsonists. While these have been more theoretical arguments, there is some empirical support. One study found that self-provision of collection-recycling was not a realistic threat (OECD, 2006, p. 146). Another study found that certain monopoly PROs incurred excess costs. (OECD, 2006, p. 135) A merger decision found that a monopoly provider of a legally required service would be able to raise prices to an extreme level (Baterpol Sp. Zoo by Orzel Bialy S.A., cited in OECD 2010, p. 81). Together, these suggest that, if a PRO is a monopoly, it will have and exercise market power. Where a monopoly PRO is owned and run by the obligated industry, then there is a risk that it be used to exercise market power by raising prices, and a risk that free-riding by individual firms within the obligated industry will reduce the PRO’s efficiency.

Economies of scale

Monopoly may, however, be the least-cost structure to supply a market. If technology is stagnant and products are fairly homogeneous, and there are significant economies of scale, then the market might be supplied at least cost by a monopoly. Economies of scale means that average cost is minimised at a scale that is large compared with the size of the market. An example where scale economies might be significant would be the treatment of waste that requires highly specialised systems with onerous permitting procedures (both of which imply high fixed costs), but that arises in relatively small quantities. If the international movement of waste is restricted, then demand may be sufficiently low that these services are provided at lowest cost by a monopoly.

One potential source of economies of scale is high fixed costs. A key question is how large are the fixed costs incurred by a PRO from organising the collection, transport, and treatment of waste, and on-going monitoring costs. If these constitute a relatively small share of total costs, then this would not imply scale economies. Collection frequently enjoys substantial scale economies. Collection could therefore be a source of scale economies for a vertically integrated PRO. However, if shared access to the collection infrastructure is feasible, then the scale economies in that activity need not imply scale economies for integrated PRO services. The Swedish competition authority pointed out that separating the financing of producer responsibility from the collecting part would aid in assuring equal access to infrastructure (OECD, 2006, p. 146). Collection infrastructure has been shared in different ways.14 Economies of scale at smaller scale can limit the feasibility of producers fulfilling their EPR obligations themselves, since individual producers usually generate smaller quantities of waste than the entire national market.

Free-riding

Reducing the cost of free-riding is another argument made in favour of monopoly PROs. Free-riding is where one firm benefits from the actions and efforts of another without paying or sharing the costs. It arises when it is difficult to exclude users who do not pay. Free-riding reduces the incentives to provide the good or service, and in the extreme may result in it being withdrawn. In the PRO context, the main concern is that producers may not pay for all of the collecting-recycling services they use. They may, for example, under-report quantities or not know the movement of their products, so not know which quantity to report in which market. In addition, producers may split their EPR among more than one PRO in a given market. Relevant factors in assessing this argument include how the structure of PRO markets affects the incentives to free-ride, the difficulty of detecting it, and the effectiveness of suppression tactics. A separate concern is that competitive PROs may shirk their obligations with respect to public information campaigns, or to inspect the quality of the sorted material. Regulatory oversight can detect the former type of free-riding, and independent inspection the latter.

Lower fees would lower incentives to free-ride, all else equal. In principle, more competition leads to lower costs and lower prices. However, as pointed out in the introduction, the effect of number of PROs on collection-recycling fees is not proven in the limited empirical literature. It is, however, argued that PROs in competitive markets have incentives to target free-riders, since these producers would incur no switching costs.

It is argued that detecting free-riding is easier if there is a single PRO. Where multiple PROs provide the same service in a market, a system is required to ensure that the total quantity of collected waste from individual producers does not exceed the total quantity reported to PROs as having been put on the market. National registers, operated by Member States of the EU, is one mechanism that has been put into place too recently to evaluate their effectiveness.

A study was carried out on the effectiveness of tactics to suppress free-riding on PRO services (Marbek, 2007). A four-case study on efforts to reduce producer free-riding in European packaging waste and WEEE take-back systems found a number of common elements: First, the programmes were mandatory, without free-riding by design: Even small producers had to pay something. Second, the programmes were operated by monopoly PROs. Third, government failure to enforce was identified as the key determinant of remaining free-riding. Closer reading of the case studies shows that members were made at least partly responsible for detecting free-riders, e.g. retailers agreed with the PRO to monitor whether suppliers had audited proof of having paid the recycling fee, and to charge them if not. Also, members were given incentives to monitor compliance, e.g. collectors were paid only for the weight of material for which a fee had been paid, and not for all material they might collect. In the case of bottle-collecting machines, they could detect whether a deposit has been paid, and did not pay out if it had not (Marbek, 2007). Whether the effectiveness of the tools mentioned – retailer monitoring of suppliers, monitoring of collected material, paying collectors only for fee-paid collected waste – would be reduced by multiple rather than monopoly PROs was not studied, since all the case studies concerned monopoly PROs.

Regulatory oversight

Ease of regulatory oversight is another argument made in favour of monopoly PROs. Regulators incur higher costs to award multiple licenses, monitor data from multiple sources, and hold multiple PROs to account, it is argued. Regulators may therefore prefer to deal with only a single entity. Experience shows, however, that regulators do not face insurmountable difficulties in licensing non-monopolies (RPS et al., 2014, pp. D-13, 14, 16). However, where the incremental cost of regulation is high, the consumer benefits from additional entry – e.g. lower costs or higher quality or quicker innovation – need to be weighed against those costs.

Regulatory oversight may be enhanced by having multiple regulated firms. In particular, the multiple sources of information represented by multiple firms (in this case PROs) may provide more information to the regulator. More information can allow better regulation.

In summary, the cost and effectiveness of regulatory oversight may be affected by the number of firms regulated. Costs of licensing and inspection may be lower with fewer firms, but the regulator would have access to more information, and perhaps different points of view, where there are more firms subject to its oversight. This can lead to better regulation.

Incentives to invest

An argument for a temporary monopoly at the outset of an EPR scheme is to give incentives to make risky, irrecoverable investments. Where there is uncertainty, the fact that sunk costs cannot be recovered if the venture turns out badly can make the initial investment uninviting. Guaranteed monopoly and, with legal obligations to buy the service, guaranteed demand reduce the risk of an unprofitable venture.

Monopoly may also be used to aggregate early-stage demand in order to exploit scale economies, which in turn gives incentives to make sunk investments. Although it does not concern a PRO, the Sydhavnens Sten and Grus decision illustrates these dynamic considerations for a new waste recovery facility. In the decision, the European Court of Justice considered whether the grant of exclusive rights to process non-hazardous building waste arising within Copenhagen violated European competition law (Case C-209/98, Entreprenørforeningens Affalds/Miljøsektion (FFAD) v Københavns Kommune, judgment of the ECJ of 23 May 2000, ECR [2000] I-3743). The court found that although the grant of an exclusive right led to a restriction of competition, it could be regarded as necessary for the performance of a task serving the general economic interest. (ibid., point 81) The restriction enabled the chosen undertakings to receive a sufficiently large flow of waste for them to be interested in expanding the limited processing capacity. (ibid., pt. 83, 79) In this case, the benefit of the restriction – the establishment of capacity to manage building waste which would not otherwise be built – was seen to outweigh the cost in terms of restricted competition for the duration.

A temporary monopoly may be efficient at the outset of an EPR programme. Relevant factors to compare costs and benefits include uncertainty, the size of sunk costs, and the existence of significant scale economies over the size of demand. Although it may be more efficient to establish a temporary monopoly, the basis for the decision should be reviewed critically at the design stage, and subsequently reviewed regularly to learn whether conditions have changed. Restrictions on competition should be removed as soon as possible.

Barriers to entry

The exercise of market power can be limited by new entrants. But if entry is not likely, or timely, or sufficient in size or scope, then the entry of new competitors cannot be relied upon to keep market prices low or quality high. Consequently, an examination of barriers to entry is very often part of a competition analysis and comments on barriers to entry are very often part of the assessment of the impact of regulation on competition in a market.

A barrier that simply slows entry, without preventing it entirely, can affect competition in a market. Entry barriers are often divided into structural and strategic. Structural entry barriers are cost and demand factors. They include economies of scale and, usually, the time and cost to meet legal requirements. A law that grants an exclusive right to serve a market is an entry barrier. Strategic barriers are barriers that have been deliberately created or enhanced by the market incumbent. They can include long-term exclusive agreements or certain pricing practices that give buyers incentives not to switch suppliers. It may be difficult to distinguish legitimate business conduct from conduct to raise barriers to rivals’ entry. This subsection examines some of the conditions in PRO markets that may delay or even prevent entry.15

Structural barriers to entry

Sunk costs are investments that cannot be recovered once committed. Costs to meet legal requirements are an example. The riskiness of entry depends on the interaction between sunk costs and uncertainty about future market conditions. If sunk costs are high, then more uncertainty about future profits in the market makes entry less attractive.

An obligation to enter a market nationwide, increases sunk costs if the best entry strategy absent the obligation would be to enter at small scale in a limited area. A universal service obligation is often imposed to prevent new entrants from “cherry picking” the most profitable areas. Substantial experience with ensuring universal service in, e.g. postal delivery and tele-communications, shows that these obligations are often unnecessary and may protect inefficient incumbents. Changing the service obligation can considerably shrink the sunk costs of entering, which improves the prospects for entry. Among the questions to be considered in assessing a universal service obligation is whether the service, as well as the price, need be the same in high- and low-cost areas (OECD, 2004b). An example where sharing certain waste collection infrastructure lowered the cost of nationwide coverage is provided in Box 4.2.

Access to the incumbent’s collection infrastructure was at issue in Sweden. Regulation required waste packaging PROs to serve the entire country. An entrant was unable to duplicate the incumbent’s collection infrastructure: In rural areas, it was very costly, and in urban areas the incumbent used municipal sites that could not be duplicated. The incumbent was accused of denying access. The entrant complained to the competition authority, accusing the incumbent of abuse of dominance. After consultations with the competition authority, the parties entered into commercial negotiations that lead to a solution whereby the two firms shared the collection infrastructure at issue, and shared the costs. This enabled both PROs to offer nationwide service (Nordic Competition Authorities, 2010, pp. 51-2; Plastkretsen/FTI dnr 152/2008, decided 10 July 2009)

Subsidy to enter a market reduces the level of sunk cost. In some instances in Norway, the first PROs established in a waste stream received direct economic support or other services from the state (OECD, 2006, p. 122).

Two other structural barriers to entry that could be relevant for PROs are economies of scale and network effects. The former are entry barriers because entrants typically operate at smaller scale than incumbents, so have higher average costs than incumbents. Network effects arise when the value a user gets from a product depends not only on his own consumption but also on the number of other users who also consume it. In the case of different types of users, A and B, then the value a user of type A gets depends on the number of users of type B. An example is newspaper readers and advertisers. An entrant would need to attract not just users of type A, as it must in markets for products without network effects, but also simultaneously attract users of type B, e.g. both producers and collectors are necessary to the success of a PRO.

Strategic barriers to entry

Strategic barriers, in contrast to structural barriers, are deliberately created or enhanced by the market incumbents.

Denying entrants access to “essential facilities” or strategically increasing users’ switching costs are strategic entry barriers that have featured in competition cases in the PRO market. Although the definition of “essential facilities” differs somewhat between jurisdictions, the basic idea is that there is something to which access is necessary to compete in a market, it cannot be feasibly duplicated, it can be feasibly shared, and it is controlled by a monopolist or a dominant firm. If a competitor is denied access, then the monopolist may be ordered to grant access under reasonable conditions – itself hard to define. The recognition that ordering access can diminish incentives for private investment in such facilities has limited the frequency with which mandatory access is ordered under competition laws.

Collection infrastructure has several times been found to be an essential facility for packaging PROs. Leading examples are the European Commission’s decision on DSD’s agreements, as well as its decisions granting exemptions for the French Eco-Emballages and for the Austrian Altstoff Recycling Austria AG (“ARA”). These decisions essentially prohibit long-term exclusive contracts between PROs and waste collectors. An exclusive contract means that one or both parties agree to deal, in a certain product, only with the other party. The decisions restrict the duration of contracts (EC DG Competition, 2005, point 81). And they prohibit any requirement that collectors send all their waste to a single PRO (Commission Decision No. 2001/837/EC DSD 2001 OJ L 319/1, confirmed by Case T-289/01 DSD, judgment of 24 May, 2007; Commission Decision No. 2004/208/EC ARA, ARGEV, ARO 2004 OJ L 75/59; Commission Decision No. 2001/663/EC Eco-Emballages, OJ 2001 L 233/37). However, the Commission’s decision on DSD explicitly accepts the necessity of a countrywide network of long-term exclusive contracts for collection and sorting in order to incentivize the investments for the first-ever extensive take-back system (Commission Decision No. 2001/837/EC DSD 2001 OJ L 319/1, point 156).

More recently, the statement of objections sent to ARA by the European Commission in 2013 concerns inter alia an alleged refusal by ARA to grant access to its household collection infrastructure. This infrastructure consists of containers and bags, as well as the contracts with waste collectors and municipalities. Austrian law requires PROs to offer collection nationwide, but duplicating the infrastructure is impossible. Thus, any competitor would depend on access to ARA’s infrastructure. If proven, denial of access to an essential facility would constitute an abuse of dominance (European Commission, 2013). At writing, proceedings are ongoing. In Austria, a new law would allow the nationwide coverage requirement to be met by a combination of own and shared collection infrastructure (OECD, 2010, p. 72).

Conditions of entry are important determinants of competition in markets. Some barriers erected by incumbents, such as denial of access to essential facilities, can be addressed under competition law. In some instances, this implies sharing of infrastructure or limiting the extent and duration of exclusive contracts (see Box 4.2). Regulation may inadvertently make entry more costly or time consuming or, if imposing numerical restrictions, impossible.

Switching costs

Switching costs can be a barrier to entry and directly dampen competition. Although some switching costs are inevitable, a dominant firm can make entry more difficult if it can increase the costs that suppliers of a necessary input incur when they switch customers. High switching costs can also dampen competition directly: If, for example, it is costly to switch suppliers, then other suppliers are viewed as less substitutable for a buyer’s current supplier.

Several elements that raise switching costs are reviewed here. One is vertical integration, i.e. ownership links between producers, collectors or treatment providers and a PRO. Second, the structure of fees charged by a PRO has been found to raise producer switching costs. Third, operating in the same way are requirements that a producer channel all its EPR through a single PRO. Fourth, the non-portability of a PRO’s financial reserves can raise the cost of producers switching. Long-term agreements that make one PRO the exclusive trading partner of waste collectors, reviewed above as a strategic barrier to entry, can also be viewed as raising collectors’ switching costs.

This section finds that vertical integration can make entry by new PROs more difficult: Ownership links between producers, collectors or treatment providers and a PRO discourage them from switching their custom to a rival PRO. Also, the structure of the fees charged by a PRO, non-portability of financial reserves built up in a PRO, and requirements contracts can raise the cost of producers switching. Long-term exclusive agreements between a PRO and waste collectors can raise collectors’ switching costs.

On the other hand, these ownership arrangements and agreements can have positive effects, such as encouraging investments that pay off only if the relationship is maintained. Therefore, as indicated in in the following, these types of arrangements and conduct need to be assessed case-by-case.

Vertical integration

Vertical integration between users and PROs may hinder users’ switching to rival PROs. For example, the acquisition from producers by a financial investor of the German packaging PRO, DSD, was seen as freeing producers to choose the best waste solution on a purely economic basis. This promoted entry by new providers of waste solutions, as well as made DSD no longer subject to interference in favour of shareholders. Earlier, waste management companies had ended their ownership of DSD. As a consequence of the sale, the German competition authority ended a proceeding against DSD (OECD, 2006, p. 105). The Norwegian competition authority, also, has expressed the view that “splitting the waste-management value chain and differentiating the various recycling sub-markets can resolve the problems of today’s waste recycling systems” (OECD, 2006, p.138).

On the other hand, producers on whom the EPR are imposed may find that joint ownership of a PRO is the best way to ensure that the organisation and infrastructure will be in place when those responsibilities have to be executed, and that producers would have the best incentives to ensure that the EPR are fulfilled in the most efficient manner. Producers may also be concerned that an independently owned PRO may exercise market power against them in the form of inefficiency and higher fees.

Whether vertical integration results in a more or less efficient provision of EPR is an empirical question. One relevant comparison is the liquidity of the market for the shares of a producer-owned PRO and the liquidity of the market for PRO services: If the capital market is less liquid, then it impedes producer switching. Not only is its effect on switching costs and therefore competition among PROs relevant, but also other effects on competition in product markets. These are addressed in a later section.

Fee structures

The structure of fees can raise switching costs. A loyalty discount or rebate means that the price depends on the quantity or proportion of purchases from the given supplier in a way that discourages buying from a different supplier. The economic incentives from a loyalty discount or rebate bind the buyer to the supplier, having the same effect as an exclusive contract.

The structure of fees initially charged by the German packaging PRO, DSD, was found inter alia to raise producer switching costs to exclude rivals in the PRO market. More detail is provided in Box 4.14. The European Commission found that DSD had abused its dominant position by charging customers according to the volume of packaging bearing the Green Dot™ trademark rather than according to the volume of packaging for which DSD provided the take-back and recycling service. This discouraged producers from switching PROs or self-complying since such actions would not reduce the fee owed DSD and would increase costs, e.g., fees paid to a different PRO. DSD was ordered to modify its pricing formula so that fee were payable only on packaging benefiting from the PRO services (European Commission Decision No. 2001/463/EC (DSD) 2001 OJ L 166/1, points 114-116, 154).

Requirements contracts

A requirement that a producer use a single PRO within a waste stream rather than splitting the service among several PROs can make entry into the PRO market more difficult. A newly-entered PRO may be unable to provide the range of services required by a given producer. The European Commission has regarded the practice as “necessary to encourage vital investment in…collection and recycling infrastructure,” but it would no longer regard it with such leniency if recovery and recycling targets had been reached (DG Competition, 2005, points 72-5).

Financial reserves

Non-portability of financial reserves has been identified by some as an impediment to competition among PROs for producers. In some jurisdictions, producers who switch PROs cannot take with them the share of the contingency reserves which they have paid in, although they do take their EPR responsibility with them to the PRO which they newly join. This imposes a high switching cost on producers. A report commissioned by the Irish environment department recommends that a switching code be developed for Ireland “to facilitate the transfer of the producer’s contribution to the contingency fund from one PRO to another.” It points out that, although potentially complex, other sectors such as pension funds manage such transfers. The proposal anticipates payments made by a producer who withdraws from the market would remain in the PRO to pay for treatment of the orphaned products. And it recognises that a PRO’s financial reserves need to be sufficient to cover the cost of collecting and treating waste in the event the PRO ceases operation (RPS et al., 2014, pp. 61-6).

The Norwegian competition authority takes a similar position on the portability of financial reserves. The authority recommended that two features of national environmental regulations for PROs be changed: The absence of an upper limit on the size of financial reserves a PRO may accumulate, and members of a PRO having no right to take “their” share of the reserves with them when they switch PROs. Non-portability of PRO financial reserves has arisen in Norway in the case of end-of-life vehicles and WEEE (Konkurransetilsynet 2008c; Nordic Competition Authorities, 2010, p. 51).

Non-portability of financial reserves is not universally viewed as an impediment to producers’ switching. An Oslo district court heard the complaint of a large WEEE producer who had switched to a new PRO without taking a share of the previous PROs’ financial reserves. The producer later asked for a share of the reserves to be paid out and was denied. The court noted that the producer had indeed switched to a new PRO, and that several smaller producers had earlier departed the PROs without asking for a share of the financial reserves. The court ruled in favour of the PROs.16

Other competition issues

A few other competition issues have arisen in PRO markets. One is the effect of clearing rules on competition. Second is an agreement for two PROs to specialise in different areas, and not to compete to serve the same waste stream. A third issue is the possibility of predatory pricing: In this abusive strategy, prices are initially low to encourage exit but later, after rivals have exited, prices are exploitatively high.

Clearing

Where there are multiple PROs in a market, “clearing” is needed to ensure that the legal threshold for taken-back waste has been met (Bio, 2014, p. 105). Clearinghouses collect and aggregate data from the various PROs to ensure the data is fair and accurate, liaise with public enforcement authorities, and may allocate costs for, e.g. reimbursement of local authorities for help desks and provision and maintenance of areas for waste collection containers. The design of the clearing system should take into account the incentives of firms to create and exploit market power; and it should avoid becoming a tool for cartelisation through information exchange. One of the ways regulation can increase market power is for the penalty for non-compliance to be high, so that firms have little real alternative than to deal with an exploitative monopoly.

Although it has now been changed, and appears to be an isolated example, the former system of WEEE clearance in the United Kingdom illustrates how monopoly can be created in an apparently competitive PRO market. Under the former regulation, the treatment of every kilogram of WEEE collected from households had to be financed by a PRO. However, the actual obligation of each PRO was revealed only after the end of each compliance period (one year). At the end of a compliance period, the different PROs would settle up, with those in surplus selling “evidence” of compliance to those in deficit. The regulation guaranteed that there would be demand for 100% of the obligated WEEE: A PRO who did not fulfil its obligation would be subject to criminal sanctions. Thus, it was advantageous for a PRO to have access to WEEE that exceeded its forecast obligation, since it could predict with certainty that another PRO would require that surplus in order to meet its obligations. At this point, the PRO in deficit was subject to exploitative pricing by the PRO in surplus. In addition, this system dis-incentivised PROs from attracting producers/importers from their rivals (United Kingdom Department for Business, Innovation and Skills, 2013, points 21, 43, 38).17 All in all, these regulations provided little incentive to reduce the cost of collecting and treating WEEE. The new regulations make a number of changes. First, they reduce the penalty for not meeting the obligation: A PRO in deficit at the end of a compliance year must pay a compliance fee, rather than be subject to criminal sanctions as before. Second, producer/importers may not withdraw from a PRO during the course of a compliance year (United Kingdom Department for Business, Innovation and Skills, 2014, p. 13). The first change reduces the market power of PROs who over-comply, and the second change removesdisincentives to compete for producers.

Specialisation agreement