Chapter 4. The teaching workforce in Lithuania

This chapter presents a profile of the teaching workforce in Lithuania and describes current approaches to teacher initial education, recruitment, qualification requirements, work load, professional development and career structure. It considers the strengths and challenges inherent in the current system and makes policy recommendations designed to improve the management and development of the teaching workforce, including with a focus on planning the future supply of teachers and creating a more coherent teacher career pathway.

Context and features

Profile of the teaching workforce

In 2010, teachers made up 3.5% of the Lithuanian active population (total of employed and unemployed persons), which was the second highest concentration of teachers in any European Union country (Luxembourg is the highest at 3.6%; the EU average is 2.1%) (Eurydice, 2013, Figure D11). The majority of Lithuanian teachers (92% in 2015/16) teach in general education schools. Between 2009/10 and 2015/16, the total number of pedagogical staff dropped by 16.5%, but the drop was slightly more pronounced in vocational education: in general education schools a drop of 16.2% to a total of 33 097 pedagogical staff (compared to 39 497 in 2009/10); and in vocational education and training schools a drop of 19.3% to a total of 2 866 pedagogical staff (compared to 3 550 in 2009/10) (Lithuanian Education Management Information System – EMIS).

Pedagogical staff in general education schools in Lithuania comprise four different groups: teachers of Years 1 to 4 (representing 22.7% of the overall pedagogical staff); teachers of Years 5 to 12 and Years 1 to 4 in gymnasia (63.7% of the overall pedagogical staff); pedagogical staff providing assistance to students (11.7% of the overall pedagogical staff); and pre-primary pedagogues (1.9% of the overall pedagogical staff). As shown in Figure 4.1, the reduction in pedagogical staff between 2009/10 and 2015/16 was not distributed equally across the different professional categories. While the number of teachers for Years 1 to 4 decreased by 12.2% and the number of teachers for Years 5 to 12 and Years 1 to 4 in gymnasia decreased by 22.7%, the number of pre-primary pedagogues declined by only 6.5% and the number of pedagogical staff providing assistance to teachers actually increased by 19.8% (Figure 4.1).

Source: Data from the Lithuanian Education Management Information System (EMIS).

In vocational education and training (VET) schools, the body of professional staff comprise the following three groups in 2015/16: teachers (representing 30.4% of the overall pedagogical staff in VET), teachers of vocational training (65.5% of the overall pedagogical staff in VET) and tutors (3.8% of the overall pedagogical staff in VET). Between 2009/10 and 2013/14, the decline in pedagogical staff was most pronounced among teachers (a decrease of 24.4%), whereas the number of teachers of vocational training decreased by only 3.7% and the number of tutors increased by 9.4% (NASE, 2015).

As in other OECD countries, female teachers outnumber male teachers in Lithuania. The degree of feminisation of the Lithuanian teacher workforce is very high in general education schools, with 97.9% of female teachers at the primary level (ISCED 1) and 84.2% of female teachers at the secondary level (ISCED 2 and 3) in 2015 (NASE, 2015). The teaching profession in Lithuania is considerably aged and has become more so in recent years. In 2015, the average age of teachers in Lithuania was 48.5 years. Only 3.8% of teachers in general education schools were aged less than 30 years in 2015, compared to 6.3% in 2011. At the other end of the age distribution, 49.7% of teachers were aged 50 and over in 2015, compared to 41.6% in 2011 (NASE, 2015). International data clearly show that the ageing of the teacher workforce is a comparatively greater challenge in Lithuania (Figure 4.2). Insights from international surveys indicate that in international comparison Lithuanian teachers have considerably more years of experience teaching on average (Table 4.1).

Note: Year of reference for European data is 2013 and for OECD data is 2012.

Sources: European Commission/EACEA/Eurydice (2015a), Appendix to the Teaching Profession in Europe: Practices, Perceptions, and Policies, http://eacea.ec.europa.eu/education/eurydice/documents/thematic_reports/184EN_APPENDIX.pdf; OECD (2014), Education at a Glance 2014: OECD Indicators, https://doi.org/10.1787/eag-2014-en, Table D5.1.

Initial teacher education

Initial education of pedagogical staff for pre-school and general education schools in Lithuania is provided at colleges and universities. There are several different ways to acquire teaching qualifications in Lithuania:

-

Completing an initial teacher education programme at either the bachelor’s degree or master’s degree level (studies taken at the master’s degree level should grant graduates a pedagogical qualification for teaching a second subject or performing an additional pedagogical role, such as vocational guidance counsellor or career counsellor).

-

Completing an optional module of pedagogical studies as part of a bachelor’s degree programme that does not primarily aim at training pedagogical staff.

-

Completing pedagogical studies under non-degree study programmes after having completed higher education in a different study area.

Vocational education and training schools also employ vocational teachers in addition to teachers of general school subjects. Initial teacher preparation for vocational teachers is organised in a consecutive model whereby a vocational qualification is studied first, followed by pedagogical studies. VET teachers must have a vocational and pedagogical qualification. If they do not have a pedagogical qualification, they are offered a 120-hour course on pedagogy and psychology principles. These courses are provided by accredited teacher development institutions. Additionally, universities provide programmes for vocational teachers’ pedagogical education.

In order to attract young talented people to initial teacher education, the Lithuanian government established a targeted teacher education scholarship to support the acquisition of teaching qualifications to students having demonstrating good academic achievements. The amount of the scholarship is LTL 400 per month.

Qualification requirements

New qualification requirements for Lithuanian teachers came into force in September 2014. According to these requirements, a teaching position in pre-school and general education schools may be taken up by an individual having completed a tertiary education programme,1 holding a pedagogical qualification (or completing such qualification within two years after taking up a teaching position) and having completed studies in a specific school subject or programme. The requirement of completing studies in a specific subject or programme can be waived for individuals with at least 15 years of work experience in teaching a specific school subject or area as they are considered specialists in that subject or area. For teachers of initial vocational education and training programmes, there are two types of qualification requirements: either: a) holding a higher or post-secondary qualification2 and a pedagogical qualification (if not, a course in educational psychology must be duly completed); or b) having graduated from a vocational school, having completed secondary education, holding three years of practical experience in the respective study area and having completed a course in educational psychology.

Recruitment into teaching

Teacher vacancies must be publicly announced as required by the Ministry of Education and Science. Teachers are hired into schools through an open recruitment procedure organised at the school level and led by the school principal. Teachers apply directly to the school. After submitting their application and required documents, eligible candidates are invited for an interview with the school principal, plus up to three representatives of the school council may join the interview as observers. Following the interviews and consultation with experts, the school concludes an employment contract with the successful candidate. School principals have autonomy in teacher appointment, deployment and dismissal. They also confirm teacher job descriptions based on the requirements set out in national regulations.

In general, given the high number of pedagogical staff in Lithuania, job vacancies would appear to be very limited. International data indicate minimal vacancies as reported by school principals: in TIMSS 2011, 93% of students were in schools where the school principal reported no vacancies for mathematics teachers; and in PISA 2012, almost all students were in schools where there were no concerns about a lack of qualified teachers interrupting instruction (Table 4.2). However, there is an incentive programme to attract teachers to certain areas of shortage under which teachers working in schools far from their place of residence may have their transportation and/or accommodation costs covered by the school founder.

Certification and career structure

There are three different qualification categories teachers can aspire to: senior teacher, teacher-methodologist and teacher-expert. These qualification categories represent a sequence of career steps, associated with specific responsibilities and a salary supplement. Table 4.3 presents the number of teachers who had acquired the different qualification categories in 2013. As can be seen from the table, the vast majority of teachers in Lithuania have acquired a qualification category: almost half of the teachers in Lithuania are senior teachers (45%), and over one-third of teachers are teacher-methodologists (39%). The category of teacher-expert, however, appears to be reserved for a small minority (only 3%) of teachers across Lithuania.

It is voluntary for teachers to apply to a higher qualification category. The basic rules and criteria for certification are determined through a national framework. Every school is required to set up a certification board, which is responsible for decision making regarding their teachers’ promotion to different qualification steps. When making decisions about their teachers’ advancement to higher levels of certification (methodologist or expert), the school’s certification process must also involve external members. These external members usually represent the municipal authority and the national administration.

The main selection criteria to access a higher qualification category are related to teachers’ experience and qualifications. Teachers must have four years of working experience as a teacher to be eligible as a senior teacher, five years of working experience to be eligible as teacher-methodologist and six years of experience to be eligible as teacher-expert. In addition, the certification board considers the teacher’s formal qualifications in national priority areas. Currently, teachers applying for promotion to a higher qualification category must provide evidence of having undertaken professional development in the areas of information and communication technologies (ICT) and special educational needs (SEN). The certification process further involves a lesson observation conducted by the school administration or external evaluators.

Workload and use of teachers’ time

Teachers’ conditions of service are regulated by the Labour Code, government regulations and other legal acts. Responsibility for teachers’ employment conditions are shared between the government, the Ministry of Education and Science, the municipalities and the school leadership (Eurydice, 2014). Teacher employment in Lithuania is conceived on the basis of a workload system, i.e. regulations stipulate the total number of working hours and define the range of tasks teachers are expected to perform beyond teaching itself. A teacher’s working week consists of 36 hours comprising contact hours and additional tariff hours. These are defined as follows:

-

Contact hours refer to the time during which the teacher works directly with students and include lessons, extracurricular teaching and teaching in non-formal educational institutions.

-

Additional hours refer to the time allocated for indirect work with students and include lesson preparation, marking and class teacher responsibilities. While contact hours are recorded by teachers in official registers, the record keeping for additional hours is not formalised.

Together, the contact hours, additional hours and breaks between lessons are referred to as hours of pedagogical work. As explained in Chapter 2, teachers’ tariff salary is established for 18 contact hours per week. For teachers of general education subjects, the number of pedagogical working hours is established per school year. Beyond the hours of pedagogical work, teachers may receive salary allowances for additional responsibilities, such as supervision of the dormitory, workshops or other tasks for up to four hours per week.

In international comparison, Lithuanian teachers have on average some of the smallest class sizes (Chapter 1). Indeed, on this aspect (manageable class size) and other selected factors, Lithuanian teachers report relatively favourable working conditions compared to their counterparts in other countries (Table 4.4).

Teacher competency requirements and professional development

The 2007 Description of Teachers’ Professional Competence, approved by Order of the Minister of Education and Science, provides an overview of the skills and proficiencies Lithuanian teachers are expected to acquire. It relates to all teachers including in pre-primary, basic and secondary education as well as special education and vocational and non-formal education. The document groups relevant teacher competencies into four groups: i) general cultural; ii) occupational; iii) general; and iv) special competencies. However, at the time of the OECD review, work was underway within the Education Development Centre (EDC) to develop a new, more comprehensive framework of teaching standards and competency descriptors (more on this below).

According to the Law on Education, it is mandatory for teachers to undertake regular professional development. Teachers are entitled to a minimum of five days of professional development activities during a school year. The EDC is responsible for carrying out expert evaluation and accreditation of professional development programmes and the institutions providing these programmes. The Centre of Information Technologies in Education manages teachers’ individual professional development data in the Register of Teachers’ Professional Development Programmes and Events (Eurydice, 2014).

Professional development activities typically require the payment of a fee, which may be covered by the school budget or by participating teachers themselves. Schools are allocated specific funding for professional development through the student basket funding system (see Chapter 2). They can use this funding to buy the services of accredited providers of professional development and/or they may raise their own funds to buy the services of other (non-accredited) institutions.

There are a broad range of professional development providers. The EDC accredits mandatory courses in the areas of information and communication technologies (ICT) and special educational needs (SEN). It offers courses in a range of more innovative areas which are unlikely to be covered by other providers and has set up a network of learning consultants working directly with schools. In addition, the EDC has accredited 60 municipal teacher education centres across Lithuania. It also evaluates and accredits professional development bodies in higher education institutions. Other accredited providers operate under the auspices of publishing houses or specialised schools (e.g. music or arts schools). There is also a variety of private providers, not all of which are officially accredited.

Teacher professional development is funded through the state budget, as set out in the 2012 Concept on Teachers’ Professional Development. The Ministry of Education and Science plans the funding for teacher professional development and collaborates with research institutions to carry out needs analyses and evaluate the use of professional development offers by teachers. European Union funds also contribute substantially to financing teacher professional development in Lithuania. A range of European Union (EU) funded training offers have already been implemented in areas such as enhancing creativity and teaching methodologies. EU funds may also be used to offer specific seminars as part of EU projects or to organise larger conferences with the participation of international experts. The next cycle of EU funding is intended to focus on school improvement and student achievement, as part of which schools themselves are expected to set professional development priorities.

At the time of the OECD review there was no central public agency to co-ordinate teacher professional development in the country. Since February 2015, a new Division of Teacher Activity has been established within the Ministry of Education and Science. The new Division has a mandate to co-ordinate teacher performance evaluation, professional development and appraisal. Professional development is provided by a range of different institutions as described above. Information about available programmes, seminars and other events is typically published by the municipal education units and the regional teacher education centres. Schools and teachers select professional development in the free market using their own budgets for professional development.

Strengths

Policy documents promote a renewed focus on teacher professionalism

Promoting the professionalism of teachers is essential to enhance the focus on teaching quality and support teachers’ continuous professional learning so that they can best support the educational success of each of their students. The OECD review team commends Lithuania for the strong focus that it has placed on teacher professionalism in recent policy documents.

The curricula of primary and basic education (2008) and secondary education (2011) emphasise the importance for teachers to develop innovative teaching practices and differentiate instruction in order to prepare their students for life and work in the mid-21st century and respond to the diverse learning needs of all students. The focus on innovative and creative teaching is further emphasised through a number of programmes aiming to help teachers experiment with new approaches to teaching and learning. For example, the “Creative Partnership” programme, which involves schools from across 54 municipalities, enhances co-operation between schools and creative practitioners and provides professional development to participating teachers.

The programme of the 16th Government for the period 2012-16 puts the professional teacher in focus and sets out to: strengthen teacher status; ensure average pay above national average; change certification processes; ensure fair pay; improve initial teacher education; ensure good working and living conditions; support innovation, and enhance professional development processes. These intentions are further supported by a range of recent initiatives, such as the development of a teacher competency framework, the implementation of programmes to attract qualified graduates into teaching and the introduction of the 2012 Concept on Teachers’ Professional Development (more on these below). It is particularly positive that the focus on teacher professionalism is extended to include educators working in pre-primary education, recognising the importance of early learning and the need to recruit and continuously support qualified specialists at all levels of education.

A teacher competency framework is being developed

A professional profile or competency framework for teachers can help provide a common basis to organise the key elements of the teaching profession such as initial teacher education, teacher appraisal, certification, professional development and career advancement. Although the 2007 Description of Teachers Professional Competence provides a list of skills and proficiencies that teachers are expected to have, this description does not appear to be widely used or even known across the system. It does not provide a profile or illustration of what constitutes “good teaching” in the Lithuanian context and gives little guidance for teachers’ professional growth, professionalisation and career development. To fill this void, the Education Development Centre has been working on the development of a new competency framework for teachers that could be more closely embedded with teachers’ initial preparation and continuous learning. The competency framework describes values and attitudes that should guide all teachers in their professional activities and develops the competencies that are important for teachers’ professional development. These competencies are divided into three groups: general (or key) competencies, didactical competencies, and subject-related competencies (see Table 4.5).

The draft teacher competency framework aims to: i) describe teachers’ occupational competencies and knowledge, underlying skills and proficiencies as well as core values and attitudes; ii) demonstrate the possibility of competency growth in four stages; iii) describe how competencies could be demonstrated in professional activities and evaluated; and iv) assist teachers in their professionalisation and career development.

Based on interviews with representatives from the Education Development Centre and additional documentation, the OECD review team formed the impression that the development of the teacher competency framework was informed by evidence from international research on key aspects of effective teaching standards (OECD, 2013b). First, the draft framework is not designed as a stand-alone document but is embedded and aligned with other aspects of the teaching profession such as initial teacher education, career development and appraisal. Second, the framework is aligned with the Lithuanian Qualification Framework and it focuses on the key competencies that teachers are expected to develop through initial teacher education and professional development. Third, the competencies outlined in the framework are associated to different levels of performance with gradually increasing demands on teacher competencies. The competency framework also foresees the possibility to recognise prior learning based on evidence of achieved competencies. The intention is that the new competency framework should over time become part of the teacher certification process. Finally, the EDC is also working on recommendations for teachers to self-evaluate against the new standards and for school leaders to use the standards in regular teacher appraisal.

The (re-)definition of professional standards or profiles for the teaching profession can help acknowledge the great complexity of teaching in the 21st century and emphasise the need for continuous learning and development (OECD, 2013b). At the time of the OECD review visit, a public consultation process was ongoing and the draft standards had been discussed at 25 consultation events across six municipalities. As part of the implementation process, it will be important to continue to build on stakeholder involvement in order to ensure that there is a sense of ownership among teacher professionals. The participation of teachers in developing and implementing competency frameworks is essential to making them a credible basis to organise different aspects of the teaching profession. Teachers’ participation in developing standards for the profession recognises their professionalism, the importance of their skills and experience and the extent of their responsibilities (Hess and West, 2006).

There are initiatives to raise the attractiveness of teaching profession

There is recognition within the Ministry of Education and Science and across actors in the school system that teaching is not currently perceived as an attractive profession and that high-performing graduates are reluctant to choose teaching as a career. Throughout the visit to Lithuania, the OECD review team learned about a range of promising initiatives intended to enhance the attractiveness of the teaching profession. These included:

-

The introduction in 2010 of a programme of targeted scholarships for high performing students of initial teacher education.

-

The implementation of the programme “I Choose to Teach!”, to attract recent university graduates from different disciplines to work in schools. This programme was started with EU funding and is now managed by the School Improvement Centre with business support. Programme participants received tailored professional development to help them develop their teaching skills.

-

The implementation of state-sponsored initiatives to attract high-performing students from a range of disciplines into teaching and the provision of state funding for 400 teacher student places, which are attributed based on the completion of a motivation test.

-

There were also initiatives implemented by individual teacher education institutions, such as a mentoring programme for teachers run by the faculty of one of the teacher education institutions.

There is recognition of and willingness to address the oversupply of teachers

As described in Chapters 1 and 2, the demography of Lithuania is characterised by a significant decline in the student population, which has resulted in an oversupply of teachers. The Lithuanian authorities are well aware of this challenge and the OECD review team noted a commitment to policy experimentation in designing strategies to: i) address the current surplus of teachers; and ii) maintain the focus on preparing high-quality teachers for future generations. For example, EU funding supported a pilot internship programme for teachers, allowing teachers to undertake an internship outside the school sector once every eight years. It should be noted that teachers maintain their full teacher salary for the duration of the internship, which makes this a very cost-intensive initiative. The pilot experimented with different internship durations, from three months to one year. The pilot was being evaluated at the time of the OECD review visit and the OECD review team was told that preliminary findings indicated positive results in the sense that participants returned to their schools re-invigorated and with new ideas. Some participants left the teaching profession following their internship, which in a context of teacher oversupply, was also seen as a positive result.

Another initiative being considered at the time of the OECD review was to use EU structural funds for teachers’ professional re-orientation. Such a “re-qualification fund” would help teachers transfer to other employment sectors. At the time of the review visit, work was underway at the Ministry of Education and Science to develop the allocation mechanism for this fund.

Teachers have opportunities to apply for promotion and move up to specialist roles within their school

The presence of different qualification categories (senior teacher, teacher-methodologist and teacher-expert) associated with a teacher certification process has clear benefits. Teachers have a right to performance evaluation and can move up on the career ladder following a successful performance review.

The existence of teacher certification processes provides incentives for teachers to update their knowledge and skills and it rewards high performance and accumulated experience. The process for certification was widely perceived as fair, as it involves both school leaders and peers from another school. While teacher competency requirements are currently still under development as part of the new teacher competency framework (see above), clear requirements for formal qualification requirements have been set in 2014 and contribute to making the certification process transparent.

In addition to the advantages for individual teachers, the certification process and career structure has clear benefits for the school system as a whole. Methodologist and teacher-experts are expected to contribute to the development of their schools and the teaching profession more broadly by developing and spreading good practice both within and beyond their schools. The roles undertaken by methodologists and experts can be as diverse as co-authoring text books, coaching and mentoring other teachers and contributing to local, regional and national pedagogical events.

Professional development is valued and well-resourced

Teacher professional development in Lithuania is well-conceived and well-developed. Teachers are legally obliged to undertake professional development and are entitled to five professional development days annually. Schools receive regular funding for the purpose of teacher professional development through the student basket. Teachers interviewed by the OECD review team reported that it is common practice for teachers to make use of their five-day entitlement. This is also reflected in the results from the OECD Teaching and Learning International Survey (TALIS): in 2008, 95.5% of Lithuanian teachers reported that they undertook some professional development in the previous 18 months (compared to 88.5% on average across TALIS countries)3 (OECD, 2009). The importance attached to teacher professional development is also reflected in the professional development requirements that are part of the teacher certification and promotion processes. TALIS 2008 results also allow some insight to the benefits of professional development: Lithuanian teachers who reported having participated in more days of professional development were more likely to report having constructivist beliefs about teaching, which in turn was associated with greater job satisfaction, and to collaborate professionally and co-ordinate teaching (OECD, 2009).

At the time of the OECD review visit, work was ongoing to build a systematic approach for teacher professional development. The 2012 Concept on Teachers’ Professional Development introduces a coherent policy to further strengthen schools’ work in this area. It outlines three broad thematic areas for teachers’ professional development, which are further developed in the draft teacher competency framework (see above). Other important elements of the Concept on Teachers’ Professional Development include the possibility for teachers to accumulate funding for professional development over several years, and the establishment of a new function of “professional development consultant” to be introduced in schools, with the specific responsibility to support teachers in planning for professional learning. A key element of this work is the idea to liberalise the area of teacher professional development so that schools and teachers can take greater initiative in planning strategically for teacher development and school improvement, freely using the funds allocated by student basket.

Another noteworthy development is the recent establishment by the EDC of a network of educational consultants. These accredited consultants are expert teachers who have been specifically prepared to provide professional learning opportunities to teachers in fifteen national priority areas. At the time of the OECD review visit, work was ongoing to organise their work in a systematic way to offer “methodological days” for schools and create learning “ambassadors” in the different regions of Lithuania.

Challenges

Strategic vision for the teaching profession is only recently emerging and has not yet permeated the system

Stakeholders interviewed by the OECD review team voiced concerns about the lack of strategic oversight regarding teacher policy in Lithuanian education. While both the National Agency for School Evaluation (NASE) and the Education Development Centre (EDC) are developing initiatives that have a bearing on the teaching profession, there appeared to be a lack of strategic oversight at the level of the Ministry of Education and Science. Such oversight is important to ensure policy coherence and help co-ordinate different actors that are involved in teacher policy development and implementation. The Lithuanian Education Council particularly emphasises the need to reform teacher initial education and in-service training and also the teacher certification system (Lithuanian Education Council, no date). The OECD review team picks up each of these points in more detail below.

Although work is underway to develop a new teacher competency framework, at the time of the OECD review visit there appeared to be little debate or common understanding across the system regarding what constitutes “good teaching”. The 2007 description of teacher competencies is not currently being used to inform the professional practice or learning of individual teachers. In the absence of a widely shared reference document defining good teaching, the main guiding document for teachers appeared to be the existing curriculum and examination guidelines. However, these documents provide insufficient guidance for teachers regarding evidence-based teaching practice and the different roles and responsibilities that are expected of teachers at different stages of their career. Quite the contrary, the strong focus of teachers on preparing students for national examination bears risks of curriculum narrowing and limited focus on broader 21st century skills, which are unlikely to be measured in national examinations.

There are serious concerns related to the supply and demography of teachers in Lithuania

An ageing teaching workforce is more of a concern in Lithuanian than in OECD countries on average. In 2012, on average in the OECD countries, the proportion of teachers aged 50 or older was 30% in primary education, 34% in lower secondary education and 38% in upper secondary education (OECD, 2014, Table D5.1). In Lithuania, 43% of lower secondary education teachers were aged 50 years or older in 2013, which is also higher than the average for the European Union countries (37%) (European Commission/EACEA/Eurydice, 2015b, Figure 1.3). As noted above, national statistics show a significant increase in the proportion of Lithuanian teachers aged over 50 in recent years. The ongoing ageing process of the teacher workforce brings a number of challenges to the school system. A specific feature of the teaching profession in Lithuania is the absence of an obligation for teachers to leave the profession at a specific age. There is no specific document regulating statutory dismissal of pedagogical staff once they have reached the official retirement age. The Labour Code provides that teachers may retire upon mutual agreement, but there is no formal obligation for them to do so (Eurydice, 2014). In 2015, 7.1% of Lithuanian teachers are at the retirement age (EMIS).

At the other end of the age pyramid, there is evidence that a significant proportion of graduates from initial teacher education end up not entering the teaching profession – according to official sources, this concerns a proportion as high as 85% of entrants into initial teacher education (NASE, 2015). This is not only a source of considerable waste and inefficiencies, but it also raises concerns about a potential future undersupply of teachers. Given the current age profile of Lithuanian teachers, there is likely to be a retirement wave of teachers within the next five to ten years, at which point there will be a risk of a shortage of qualified teachers. Shortages are likely to be concentrated in specific subject areas, particularly in mathematics, science and technology. Although there are currently no teacher shortages across the education system overall, a stagnant professional body is likely to perpetuate teaching traditions that Lithuania may wish to reform, and may hinder the introduction of innovations and other initiatives.

Teaching is not perceived as an attractive career choice

Lithuanian teachers reported only average levels of job satisfaction in TALIS 2008 (88% in Lithuania; 90% TALIS average), despite the fact that they also reported relatively favourable working conditions (OECD, 2009, Table 4.19). Many of the stakeholders interviewed by the OECD review team commented on the lack of attractiveness and low prestige of the teaching profession. Especially among young men, the teaching profession is not perceived as an attractive career choice. According to internationally comparable statistics, in 2009, 85% of teachers in Lithuania were women, compared to 72% on average across the European Union (Eurydice, 2012). As in other European Union countries, women are comparatively more dominant in teaching positions at the lower levels of education and in Lithuania the level of male employees is acutely low in primary education: in 2010, women represented 97% of Lithuanian teachers in primary education and 81% in lower secondary education, compared to 85% and 67% in the European Union respectively (European Commission/EACEA/Eurydice, 2013, Figure D12). The lack of attractiveness of teaching as a profession is reflected in the small proportion of students in teacher education coming from among the most qualified graduates from secondary education.

This is related to the low relative salaries of teachers (see Chapter 3) which, to a great extent, determine the teaching profession’s social standing. As a result, the teaching profession is not competitive in the labour market, causing difficulties in attracting young people and males to the teaching profession and in keeping those already on the job motivated. In addition, teachers in Lithuania, like their counterparts in 20 European education systems (European Commission/EACEA/Eurydice, 2015b, Figure 1.5), do not have civil servant status and there are concerns regarding job security and working conditions, especially for beginner teachers. Where teachers have to be dismissed because of redundancy, it is likely that the burden of adjustment falls on the less experienced teachers who were employed most recently.

Concerns related to the organisation of teacher working hours may also contribute to the low attractiveness of the teaching profession. As mentioned above, the tariff salary for teachers in Lithuania is established for 18 contact hours per week. However, in the context of declining student numbers and teacher oversupply, many schools have responded by lowering the number of contact hours of their teachers, which results in lower salaries and lower pension rights for these teachers. National data clearly show a phenomenon of teachers in small schools taking on a second job (Table 4.6). Stakeholders interviewed by the OECD review team also reported their perception of an imbalance in the distribution of contact hours across the teaching staff in a given school, with beginning teachers being given fewer. These perceptions are borne out in national data that clearly show lower contact hours (less than 16 hours) and pedagogical hours on average for “teachers” compared to for “senior teachers” (Chapter 3, Table 3.4). This negatively impacts on the salaries of these teachers and may risk further decreasing the attractiveness of the profession for recent graduates.

Teachers are not adequately prepared to meet current and emerging demands in teaching

Initial teacher education does not sufficiently prepare the next generation for teaching

The review team formed the impression that there is a traditional approach to the organisation of classrooms in Lithuania with frontal teaching still being the predominant approach. Teaching and assessment practices have remained relatively traditional as a large majority of teachers in Lithuanian schools have been in their teaching positions for many years (often decades), and have often taught in the same school for all of their teaching careers. In 2009, 58.2% of Lithuanian teachers had been employed in the same school for more than ten years, compared to 37% on average across the European Union (Eurydice, 2012).

However, generational change in the teacher workforce will not automatically bring about innovations in teaching and learning, as there are a range of concerns around the adequacy and quality of the current provision of initial teacher education in Lithuania. Teachers interviewed by the OECD review team indicated that their preparation had focused mostly on acquiring knowledge in the specific subject matter they were teaching. Across stakeholders interviewed, there was an impression that the main focus of teacher initial education courses remained on traditional subject matter and the content of the curriculum. There seemed to be limited focus on the actual teaching process and subject didactics necessary to prepare teachers for a career in dynamic and fast-evolving classroom contexts. It appeared necessary to connect initial teacher education more closely to real-life classrooms and ongoing professional development, which would ensure coherent teacher learning all through their career.

Concerns related to professional development

Even though the importance of professional development is clearly recognised in Lithuania, its provision appears fragmented. The amount of money allocated for teacher qualification development differs by more than a factor of three among Lithuanian municipalities (Ministry of Education and Science, 2015). The supply of the professional development offer in Lithuania is based on a liberal market in which providers compete for participants. There is a diversity of providers, including the national and regional Education Development Centres, private companies, international bodies, cultural centres, universities and individual programmes sponsored by EU structural funds. However, the Lithuanian school system lacks a strategic approach to needs analysis, which would help target the professional development offer to emerging and evolving priority areas for Lithuanian schooling.

Although the offer of professional development is abundant, it is important to note that among the “barriers to teachers’ participation in professional development” reported by teachers in TALIS, the majority of Lithuanian teachers indicated that “there is no suitable professional development offered” (in 2008, 53.2% of Lithuanian teachers reported this, compared to 42.3% on average across TALIS countries) (OECD, 2009). This underlines the need to develop a strategy to target professional development better to the needs of Lithuanian schools.

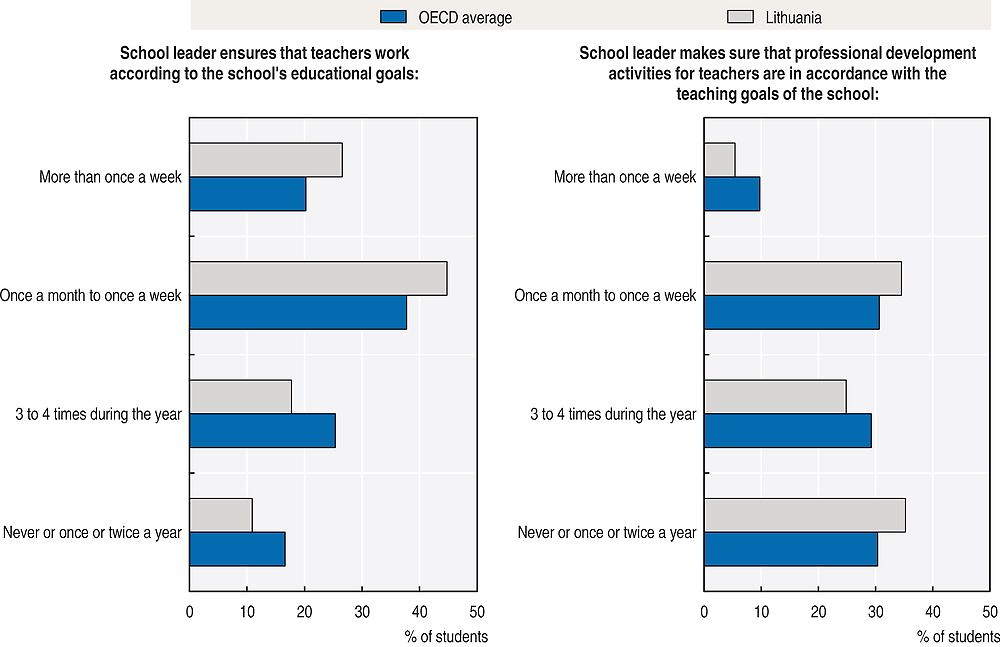

On the demand side, the review team formed the impression that professional development was predominantly a choice by individual teachers and was not systematically associated with school development needs. Despite the requirement for Lithuanian schools to establish a school-level continuing professional development plan (as is the case in the majority of European Union countries, European Commission/EACEA/Eurydice, 2015, Figure 3.7), there was little evidence of school-centred professional development that would emphasise the community of learners within the school. School leader reports from PISA 2012 indicate that while it is frequent practice to ensure teachers work to the school’s educational goals, more so than on average in OECD countries, it is a less frequent concern to link professional development activities to these (Figure 4.3). There was a comparatively weak correlation (0.35) in Lithuania between activities to promote instructional improvements and professional development and the framing and communicating of the school’s goals and curricular development, as measured in PISA 2012 (OECD, 2013a, Table IV.4.16). The OECD review team notes that at the school level – similar to the system level – there appeared to be a lack of needs analysis and targeting of professional support to meet the individual and collective learning needs identified through teacher appraisal and school self-evaluation. For example, the PISA 2012 survey asked school leaders whether their school had implemented a standardised policy for mathematics that included staff development and training and this was far less common in Lithuanian schools (30% of Lithuanian students were in schools that had done so, compared to 62% on average in the OECD) (OECD, 2013a, Table IV.4.32). As considerable national and international funding goes into teacher professional development, there is a need to make the use of such funding more efficient and make sure that it contributes to raising the quality of teaching provided in schools.

Source: OECD (2013a), PISA 2012 Results: What Makes a School Successful (Volume IV): Resources, Policies and Practices, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264201156-en, Table IV.4.8.

Concerns related to the certification process and career pathway

The teacher certification process has clear benefits. It provides incentives for teachers to update their knowledge and skills and it rewards teachers for their performance and experience. However, there are a range of implementation aspects that raise concerns.

First, certification is a one-off process that does not require regular “re-certification” or confirmation of teachers’ continuing performance at the expected level. It therefore provides no guarantee that teachers update their skills on an ongoing basis and continue to engage in professional learning throughout their career. Regarding the process itself, while formal criteria are clearly defined, a large part of the certification decision is based on “historical data” regarding the teacher’s fulfilment of professional development requirements. While the certification process involves a lesson observation, in the absence of teaching standards, there was little evidence that quality criteria were consistently applied.

Second, while it is expected that teacher-methodologist and teacher-experts develop and spread good practice, they are not held accountable for the degree to which they engage in such responsibilities and there is little knowledge at the system level regarding the contributions they make. This corps of highly qualified professionals is a strong resource of the school system, which could potentially be used more effectively. While the review team formed the impression that most methodologist and experts take on broader roles beyond the borders of their own school (such as contributing to other schools or regional events), there appeared to be room for these teachers to play a greater role within their own schools to enhance pedagogical leadership and the development of professional learning communities.

Third, certification decisions are based on the level of the education sector and subject-specific competencies. This rigidity means that a teacher at the primary level cannot transfer with the same qualifications to teach at the upper secondary level. The OECD review team also encountered examples where a teacher could be at different qualification levels for the different subjects that he or she was teaching. For example, a teacher of mathematics and Lithuanian could be a teacher-methodologist in mathematics and a teacher-expert in Lithuanian. In this way, certification decisions would appear to not give due consideration to the full set of competencies that are important for teachers to be effective both within and beyond their classroom.

There are few possibilities for teachers to receive professional feedback

Unlike most other OECD countries, there are no requirements in Lithuania for school leaders to implement regular teacher appraisal and performance review cycles. The certification process is voluntary and is typically only implemented for those teachers who apply for it. Regular teacher appraisal and feedback may be implemented at the initiative of individual schools, but this largely depends on the leadership style of the principal and the evaluation culture of the school. Hence, there are wide variations across schools in the extent to which teachers have the opportunity to benefit from professional feedback to improve their practice. The absence of regular teacher appraisal processes also means that there is no mechanism to make sure that consistent underperformance will be identified and addressed. The National Agency for School Evaluation (NASE) reported that a trial initiative to introduce annual evaluation conversations with teachers was cancelled due to union resistance.

The only institutionalised opportunity for external feedback comes through external school evaluation, which includes lesson observations of individual teachers, followed by a feedback conversation. The external experts are required to include in their feedback no less than three strengths and no more than two areas for improvement, and teachers may request a more detailed discussion if they wish. While this is a very positive element of school evaluation, such evaluations are only implemented once every seven years and cannot replace the more regular feedback that teachers need to review and improve their practice on an ongoing basis.

While frequent observation, evaluation and feedback can help improve the practice of all teachers, it is particularly important for beginning teachers who have limited experience in the classroom. In Lithuania, although there is a legal probationary period of three months, there is currently no mandatory induction period for new teachers. Schools may organise their own procedures for induction, mentoring and coaching of new teachers, but international evidence indicates that while many schools have some elements in place, such practices are not widespread: in 2008, 69% of the principals surveyed in TALIS reported that there was no formal induction programme for new teachers in their school (compared to 29% on average across TALIS countries) (OECD, 2009); only 53% of Lithuanian students in PISA 2012 were in schools with a teacher mentoring system, compared to 72% on average in the OECD (OECD, 2013a, Table IV.4.32).

Policy recommendations

Develop a strategic vision for the teaching profession

As mentioned above, many valuable initiatives are underway to support teacher professionalism in Lithuania. The review team commends the progress made towards the development of a teacher competency framework and strongly encourages Lithuania to pursue its efforts in completing and implementing the framework as a core guiding document to support teacher professionalism in the school system. The teacher competency framework should be implemented in a way as to provide a common basis to guide key elements of the teaching profession such as initial teacher education, regular teacher appraisal, certification processes, teacher professional development and career advancement. Clear, well-structured and widely-supported professional standards for teachers can be a powerful mechanism for aligning the various elements that are part of teachers’ professionalism.

The four stages of teacher development described in the draft competency framework allow for the use of the framework as a basis for certification and career advancement processes. Going further, the OECD review team recommends establishing a more explicit link between the four stages of teacher development outlined in the competency framework and the existing career steps of senior teacher, teacher-methodologist and teacher-expert. It would be helpful if the document could describe the different roles associated to different career steps alongside the needed competency requirements. For the competency framework to be relevant and “owned” by the profession, it is essential that the teaching profession takes the lead in further developing and implementing it.

Manage the teacher supply

While it is important to ensure the continuous entry of new talent into the teaching profession, there is no need to increase the overall size of the teaching workforce in Lithuania. On the contrary, the continuing decline of the student population is likely to result in further school consolidation and teacher redundancy. This makes it necessary to continue developing strategies for reallocating, redeploying and retiring teachers currently employed in schools which will be affected by school (or class) consolidation.

One option to address the current oversupply of teachers would be through legal changes regarding the conditions under which retired teachers can continue to teach. In Hungary, for example, a policy was introduced that obliged teachers to choose between receiving a salary or a pension. However, there are risks associated to such a policy. Any policy which institutionalises incentives or pressure for teachers to leave the profession needs to carefully consider projected demographic fluctuations. In Lithuania, based on current population projections, teacher shortages are likely to occur in the mid-2020s. Hence it might be more effective to focus on developing a short-term incentive policy, making it voluntary and attractive for experienced teachers to plan for their own succession and leaving the profession while transmitting their accumulated knowledge and coaching others.

In this context, it is important to note that there are a number of areas in which teachers made redundant by school consolidation could assume new responsibilities. These include engaging them to help mainstream special needs students in regular schools and classes; using them to implement strategies to individually support students who are falling behind; and involving them in advisory roles within or across schools. This could go alongside offering early retirement packages for some teachers who are close to retirement age.

It would be essential to frame such policy in the context of targeted needs of the school system and to help teachers in specific areas of oversupply to move out of the profession while at the same time continuing to encourage specialists in key areas of shortage (such as the STEM subjects) to join the profession. In addition, the Lithuanian authorities should consider prioritising national funding for teacher students to subject areas in which the school system is facing shortages. As noted above, the policy of funding 400 study places in initial teacher education is helpful, but could be made more efficient by focusing further on key priority areas.

Even if there is currently an oversupply of teachers, it is important for the school system to plan ahead and ensure an adequate rate of teacher renewal so the school system is continuously provided with new ideas and perspectives. It is also important that newly educated teachers are not lost for the profession by moving into other career pathways. Therefore, continuing to work on improving the attractiveness and prestige of the teacher career should remain a priority. In addition to allocating funding to improve salaries for new teachers (see Chapter 3), the OECD review team recommends a more strategic approach to teacher education and more coherent career pathways for teachers (see below).

Create a more coherent teacher career pathway for teachers

Although career steps exist in Lithuania, there is room to further develop the teacher career in order to recognise and reward teaching excellence and allow teachers to diversify their career pathways. This is likely to contribute to make teaching an attractive career choice.

Schools and teachers are likely to benefit from a more elaborate career structure for teachers, which would more clearly define each key stages of the career. An important policy objective should be to match the career structure for teachers with the different types and levels of expertise described in the draft teacher competency framework. The current draft describes four stages of teacher development, which could be easily matched to the existing career steps of teacher, senior teacher, teacher-methodologist and teacher-expert. This would reinforce the matching between teachers’ competencies and the roles that need to be performed in schools to improve student learning.

Focus in particular on beginning teachers

The first two to three years on the job should be seen as an important first career phase, during which new teachers need to be systematically supported to develop their skills. Research from different countries points to the importance of ensuring that beginning teachers receive adequate guidance (OECD, 2010; Jensen and Reichl, 2011). At this early stage of teachers’ career, it is particularly important to ensure that teachers can work in a well-supported environment and receive frequent feedback and mentoring. One way of paying greater attention to this career phase would be to require graduates from initial teacher education to apply to be “provisionally certified” in order to seek employment as a teacher. Provisionally certified teachers could then apply for full certification upon completion of an induction period (more on this below), based on an appraisal in relation to the teacher competency requirements.

Introduce a requirement for teachers to renew their qualification levels

It is a strength of the Lithuanian system that different qualification levels exist in the teaching profession and that access to higher qualification levels is granted through a voluntary application process. However, the review team recommends that those teachers who do not apply for a higher qualification level should be required to regularly renew their qualification status. Requirements for re-certification could be set after a specific period time, such as every five to seven years. The basis for renewal could be as simple as an attestation that the teacher is continuing to meet performance standards that are agreed for the profession. Teachers at all career levels need to continue to learn and update their practice. Even methodologists and experts will need coaching/mentoring to stay up to date with pedagogical developments. Box 4.1 provides an example from Australia, where teacher registration fulfils the function that certification could have in Lithuania.

Registration is a requirement for teachers to teach in Australian schools, regardless of school sector. All states and territories have existing statutory teacher registration authorities responsible for registering teachers as competent for practice. The levels of teaching registration vary according to the jurisdiction. In most jurisdictions, teachers reach the first level of registration from the relevant authority upon graduation from an approved initial teacher education programme. Currently, each teacher registration authority has its own distinct set of standards for registration; however, from 2013 jurisdictions will be progressively introducing the Australian Professional Standards for Teachers (the Standards) which will provide a national measure for teachers’ professional practice and knowledge. Advancement to full registration (or professional competence) is achieved after a period of employed teaching practice and, from 2013, an appraisal against the Standards at Proficient level.

In all states and territories, after teachers have initially become registered within their jurisdiction, they must renew their registration. The period of registration varies but is most commonly five years. The main function of the registration process is that of certifying teachers as fit for the profession mainly through the mandatory process of accessing or maintaining “Full/Competence” status – as such, these processes ensure minimum requirements for teaching are met by practising teachers. Registration processes constitute a powerful quality assurance mechanism to ensure that every school in Australia is staffed with teachers with suitable qualifications who meet prescribed standards for teaching practice. At their initial level (provisional/graduate registration), they also provide a policy lever for setting entrance criteria for the teaching profession and, through the accreditation of initial teacher education programmes, strengthen the alignment between initial teacher education and the needs of schools.

Source: Santiago, P. et al. (2011), OECD Reviews of Evaluation and Assessment in Education: Australia 2011, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264116672-en.

Diversify roles and responsibilities associated with career steps

It was the impression of the review team that the most common tasks taken on by teacher-methodologists and teacher-experts in Lithuania were outreach functions at the level of the municipality. While collaboration beyond the school borders is an important aspect of the school’s work, it would be important to further diversity and clarify the range of roles that should be taken on by teachers at different qualification levels. In particular, there should more focus on teacher leadership in whole-school improvement. Experts and methodologists could be designated to support the school leader with specific aspects of leadership such as the co-ordination of professional development for the school, classroom observations, teacher performance evaluations, co-ordination of student assessment approaches, and so forth.

If Lithuania is to develop more systematic induction and mentoring approaches (as recommended below), the task of mentoring beginning teachers should also be a key responsibility for methodologists and experts. The current age structure of the Lithuanian teaching profession also creates a need for new functions, such as helping teachers who have been in the same school for a long time keeping their knowledge and skills up to date, or supporting colleagues with the use of information and communication technologies (ICT).

Develop a strategic approach to teacher education and professional learning for the mid-21st century

Initial teacher education

The current age structure of the Lithuanian teacher workforce has placed initial teacher education under pressure, as it heightens the importance of effectively preparing new teachers to replace those who will retire in the next five to ten years. Several stakeholders mentioned the need for initial teacher education to become more relevant to today’s classrooms and to incorporate the advances of recent international research regarding effective teaching and learning in the mid-21st century. Initial teacher education should not only provide sound basic training in subject-matter knowledge, pedagogy related to subjects, and general pedagogical knowledge; it also needs to develop the skills for reflective practice and research on the job. The design of initial teacher education needs to be regularly reviewed and such review should take into consideration the views of current school leaders and teachers.

The teaching career should be seen in lifelong learning terms, with initial teacher education providing the foundations. In this perspective, the stages of initial teacher education, induction and professional development need to be better interconnected in order to create a more coherent learning and development experience for teachers (OECD, 2005). Ideally, the teacher competency framework should provide the link between these different stages of teacher learning and provide the basis for a coherent approach to lifelong learning for teachers.

Induction

To support teachers in the transition from initial education to actual work in schools, the Lithuanian education system would benefit from the introduction of more systematic induction and feedback systems for new teachers. Most high-performing education systems require their beginning teachers to undertake a mandatory period of probation or induction, during which they receive regular support and can confirm their competence to move on to the next stage of the teaching career (OECD, 2010). Box 4.2 provides an example from Northern Ireland in the United Kingdom. Research indicates that beginning teachers benefit from systematic induction and mentoring programmes as long as mentors are carefully selected, well prepared for their tasks and given adequate time to carry out their mentoring role (Hobson et al., 2009; OECD, 2010).

In Northern Ireland, a “career entry profile” is established for each beginning teacher upon completion of initial teacher education. This profile outlines the teacher’s strengths and areas for further development in relation to the Northern Ireland competency model. When taking on a first teaching position, there is a formal one-year induction period to help teachers address the personal and professional needs and objectives identified in their career entry profile. The induction period involves a programme of both centre-based and school-based professional support. The board of governors, upon recommendation of the school principal, approves the teacher’s completion of the induction period and the teacher professional organisation (General Teaching Council for Northern Ireland) holds a record of completion of induction.

As part of the induction process, teachers then prepare a personal action plan, which forms the basis for a two-year period of Early Professional Development (EPD). This phase involves within-school support by a “teacher tutor” and by the regionally-based Curriculum Advisory and Support Services. It is aimed at helping beginner teachers further develop and consolidate their competencies. When the beginning teacher and teacher-tutor agree that all the criteria for EPD have been met, they will seek confirmation by the school principal. The board of governors approves the completion of EPD, based on the recommendation of the principal and a final reflection document produced by the teacher concerned.

The early teacher education and development phases are further strengthened through the Teacher Education Partnership Handbook, which provides guidance to all those involved in the process, including student teachers, beginning teachers, teacher tutors, education and library boards and higher education institutions.

The availability of teacher tutors in each school is an important element in facilitating the transition of teachers from initial education into full-time teaching at a school. Teacher tutors are responsible for placement and care of student teachers in a school. They are typically senior teachers who can draw on their own experience to support beginning teachers through their first years of teaching. The tutors are expected to hold regular meetings with beginning teachers, draw up action plans, assist in lesson planning, observe classroom practice, review progress and provide general support to help the beginning teacher reflect upon his or her practice and improve classroom teaching. Tutors can play a key role in helping beginning teachers understand existing standards, self-appraise their practice and use feedback from others to review and improve their practice.

Source: Shewbridge, C. et al. (2014), OECD Reviews of Evaluation and Assessment in Education: Northern Ireland, United Kingdom, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264207707-en.

Regular teacher appraisal

To support continuous improvement of teaching practices the review team recommends establishing a requirement for school leaders to implement regular formative teacher appraisal processes. This should be an internal process carried out by line managers, senior peers and the school principal with a focus on teachers’ practices in the classroom. It could be implemented on an annual basis. The main outcome would be feedback on teaching performance and contribution to school development, which should lead to a plan for professional development. It can be low-key and low-cost and include a mix of methods appropriate to the school. Some of the elements should be individual goal-setting linked to school goals, self-appraisal, peer appraisal, classroom observation, structured conversations with the school principal and peers. Such appraisal practices would ensure that all teachers receive regular feedback on their practice.

While the process for formative teacher appraisal should remain school-based, it should be linked to the framework of teacher competencies. This would allow all school leaders to develop a shared understanding of expected teaching standards and of the level of performance that can be achieved by the most effective teachers. It would also be important that school-based teacher appraisal processes are validated through external school evaluation and that school leaders are held accountable for establishing teacher a school-based teacher appraisal policy.

Linking teacher appraisal to professional development and school improvement

It was noted above that teacher professional development appears fragmented and lacking in focus on key priorities for the school system. To ensure that the provision of teacher professional development responds to the needs of the system, the OECD review team recommends linking provision more closely to a systematic analysis of needs, both at the school level and at the system level.

At the system level, the offer of professional development should be informed by the competency requirements outlined in the teacher competency framework, and thereby address concerns raised above about the fragmentation of professional development provision. This could be achieved by the Ministry of Education and Science and/or the Education Development Centre by reviewing professional development offers, and, developing guidance documents on the extent to which existing professional development relates to teacher competency framework. They could then, with the competency framework in mind, provide guidance for schools on relevant training offers. For an example from Memphis, Tennessee in the United States, see Box 4.3.

The city of Memphis, Tennessee in the United States has developed a system that explicitly links professional learning to teacher appraisal. In Memphis City Schools, appraisal is based on teaching standards, and professional development is linked to teachers’ competencies on the standards. Thus, a teacher who has poor performance on a specific indicator on a teaching standard can find professional growth opportunities related to that indicator. Memphis City Schools publishes a professional development guide each year that lists the professional growth offerings by standard and indicator. In addition, most of the professional development courses are taught by Memphis City School teachers, ensuring that the course offerings will be relevant to the contexts in which these teachers work.

Source: OECD (2013b), Synergies for Better Learning: An International Perspective on Evaluation and Assessment, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264190658-en.

At the school level, teachers’ individual choices of professional development should be more strongly influenced by: a) their own appraisal results and identification of areas for improvement; and b) priorities of the school development plan. Effective teacher appraisal should give teachers a choice from a wide range of possible professional learning activities that meet their individual needs in relation to the priorities of the school’s overall development plan. Conversely, the appraisal results of individual teachers should also be aggregated to inform school development plans. In Korea, for example, results of the teacher peer review processes not only feed into teachers’ individual professional development plans, but are also used to inform a synthetic report on professional development for the whole school bringing together the results of all appraised teachers (without identifying individual teachers) (Kim et al., 2010).

References

European Commission/EACEA/Eurydice (2015a), Appendix to the Teaching Profession in Europe: Practices, Perceptions, and Policies, Eurydice Report, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg, http://eacea.ec.europa.eu/education/eurydice/documents/thematic_reports/184EN_APPENDIX.pdf.

European Commission/EACEA/Eurydice (2015b), The Teaching Profession in Europe: Practices, Perceptions, and Policies, Eurydice Report, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg, http://bookshop.europa.eu/en/the-teaching-profession-in-europe-pbEC0115389/?CatalogCategoryID=QN4KABste0YAAAEjFZEY4e5L.

European Commission/EACEA/Eurydice (2013), Key Data on Teachers and School Leaders in Europe, Eurydice Report, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg, http://eacea.ec.europa.eu/education/eurydice/documents/key_data_series/151en.pdf.

Eurydice (2014), European Encyclopedia on National Education Systems: Lithuania, https://webgate.ec.europa.eu/fpfis/mwikis/eurydice/index.php/Lithuania:Overview.

Eurydice (2012), Key Data on Education in Europe 2012, Education, Audiovisual and Culture Executive Agency, Brussels, http://eacea.ec.europa.eu/education/eurydice/documents/key_data_series/134en.pdf.

Hess, F. and M. West (2006), A Better Bargain: Overhauling Teacher Collective Bargaining for the 21st Century, Program on Education Policy and Governance, Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts, http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED498038.pdf.

Hobson, A.J. et al. (2009), “Mentoring beginning teachers: What we know and what we don’t”, Teaching and Teacher Education: An International Journal of Research and Studies, Vol. 25, No. 1, pp. 207-216.

Jensen, B. and J. Reichl (2011), Better Teacher Appraisal and Feedback: Improving Performance, Grattan Institute, Melbourne, http://grattan.edu.au/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/081_report_teacher_appraisal.pdf.

Kim, K. et al. (2010), OECD Review on Evaluation and Assessment Frameworks for Improving School Outcomes: Country Background Report for Korea, Korean Educational Development Institute (KEDI), Seoul, www.oecd.org/edu/evaluationpolicy.

Lithuanian Education Council (no date), Lietuvos Švietimo Taryba – Dėl Pedagogų Rengimo Politikos Tobulinimo (Lithuanian Education Council – For Teacher Training Policy Development), www3.lrs.lt/pls/inter/w5_show?p_r=9495&p_k=1.

Ministry of Education and Science (2015), Lietuva Svietimas Regionuose Mokykla 2015 (Lithuanian Regional School System 2015), Svietimo Aprupinimo Centras, Lietuvos Respublikos svietimo ir mokslo ministerija.

Mullis, I.V.S. et al. (2012), TIMSS 2011 International Results in Mathematics, International Association for the Evaluation of Educational Achievement (IEA), Amsterdam and TIMSS and PIRLS International Study Center, Boston, http://timssandpirls.bc.edu/timss2011/downloads/T11_IR_Mathematics_FullBook.pdf.

NASE (2015), OECD Review of Policies to Improve the Effectiveness of Resource Use in Schools: Country Background Report for Lithuania, National Agency for School Evaluation, Vilnius, www.oecd.org/edu/school/schoolresourcesreview.htm.

OECD (2014), Education at a Glance 2014: OECD Indicators, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/eag-2014-en.

OECD (2013a), PISA 2012 Results: What Makes a School Successful (Volume IV): Resources, Policies and Practices, PISA, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264201156-en.

OECD (2013b), Synergies for Better Learning: An International Perspective on Evaluation and Assessment, OECD Reviews of Evaluation and Assessment in Education, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264190658-en.

OECD (2010), Improving Schools: Strategies for Action in Mexico, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264087040-en.

OECD (2009), Creating Effective Teaching and Learning Environments: First Results from TALIS, TALIS, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264068780-en.

OECD (2005), Teachers Matter: Attracting, Developing and Retaining Effective Teachers, Education and Training Policy, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264018044-en.

Santiago, P. et al. (2011), OECD Reviews of Evaluation and Assessment in Education: Australia 2011, OECD Reviews of Evaluation and Assessment in Education, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264116672-en.

Shewbridge, C. et al. (2014), OECD Reviews of Evaluation and Assessment in Education: Northern Ireland, United Kingdom, OECD Reviews of Evaluation and Assessment in Education, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264207707-en.

Notes

← 1. Or post-secondary education acquired before 2009 or specialised-secondary education acquired before 1995.

← 2. Or specialised-secondary education acquired before 1995.

← 3. It should be noted, however, that the average duration of such professional development was shorter in Lithuania than elsewhere (11.2 days compared to 15.3 on average across TALIS countries).