Chapter 7. Convergence

This chapter addresses trends in network and service convergence, its implications for broadband competition, innovation and investment dynamics, and provides a set of good practices to respond to opportunities and challenges. It examines changes in the value chain of broadband access and services and suggests that they be addressed in a holistic fashion, covering not only network infrastructure and traditional service providers, but also content, application and the so-called over-the-top providers (OTTs). The main policy and regulatory practices relevant to convergence are explained, including convergent regulators, convergent licensing regimes and bundling practices, and issues related to Internet openness.

Historically, distinct communication networks and their underlying technologies provided voice, data, radio and television services. Today, communication networks are shifting towards Internet Protocol (IP)-based solutions that, together with developments in terminal devices, allow access to IP-based applications on a multitude of devices, in a multilayered process that can be termed digital convergence. Convergence between traditional telecommunication operators and content providers (e.g. video delivery), has introduced an increasing number of new products and services in the Latin American and Caribbean (LAC) region.

This transition from public switched telephone networks (PSTN) to IP-based networks is closely linked to market-based broadband developments. Broadband has facilitated convergence, and convergence has stimulated demand for new services, which in turn has been a catalyst for the growth of broadband. Convergence must thus play an important role in developing a forward-looking broadband strategy.

Convergence is encouraging competition, content creation, collaboration, interoperability, mobility and product and service innovation. At the same time, however, it poses new challenges for businesses, consumers and governments in the Latin American and Caribbean region, some of which are described below.

Effects of convergence

The implications of convergence fall into three major categories:

-

Disruptions of the traditional communications industry. Technological innovation, digitalisation and increased connectivity have fused previously separated value chains (such as fixed/mobile and telecommunications/broadcasting) into mixed-value chains of access, which include content distribution service and device providers. Convergence has encouraged the upgrading and remixing of new configurations of products and services. The advent of the so-called over-the-top (OTT) players has profound implications for the telecommunications and broadcasting industries. The creation of new business models has blurred the lines between fixed and mobile communication services, and between telecommunication and content providers. This has removed the boundary between fixed-wireless and cellular connectivity, and between broadcasting and Internet services, with, for example, catch-up television, video on demand, streaming and cloud-based television.

-

Increased choice and new vulnerabilities for consumers. Users are at the centre of digital service delivery, and now have greater control over what they want to access, when and where. They are taking on an entrepreneurial role, creating their own content and services. The increased availability of broadband and convergence have resulted in the “on demand” market, which is connecting consumers and producers directly and making it possible to customise goods and services. Meanwhile, the new services are changing the relationship between suppliers and consumers. The digitalisation of media is increasing data security and privacy vulnerabilities, requiring consumers to assess more carefully what they are sharing and contracting with.

-

Regulatory boundaries have become less clear, challenging governments’ ability to deal with cross-cutting issues. Before convergence, communication regulation was dealt with in separate silos, and regulators dealt only with a few established traditional players. Convergence has blurred the distinctions between different sectors of policy and regulatory frameworks, reducing regulators’ ability to impose and enforce regulations and requiring that government departments and regulators co-operate on addressing cross-cutting issues. Jurisdictional issues are also becoming more relevant. Regulators and other national bodies may have difficulty enforcing their national legal frameworks if services are provided by players based in other countries. The rise of new technologies and players has been driving policy makers to rethink their traditional approaches, creating opportunities to lift some legacy requirements and to build, as much as possible, more technologically neutral and regulatory and policy frameworks that will prove serviceable in the future. In many cases, this has led to a review of regulations and regulatory bodies and to merging the existing bodies.

This chapter aims to shed light on the opportunities and challenges of convergence in the LAC region. In the coming years, as broadband speeds increase and the networks become more capable of delivering added-value services, policy makers in the LAC area will have to deal with issues related to, for example, adapting their own communications governance models to convergence trends, treatment of bundles and convergent offers, and Internet openness.

While Internet openness is a multidimensional concept that includes technical, economic, social and other dimensions (OECD, forthcoming), this chapter addresses a limited set of policy and regulatory issues related to Internet national governance arrangements, traffic prioritisation and network neutrality, zero rating, liability of Internet intermediaries and IPv6 (Internet Protocol version 6). Issues related to convergence of communication providers with adjacent sectors of the economy, such as banking, transport and tourism, will not be dealt with in this chapter, but the principles introduced in this section should offer a good basis for considering other cross-sectorial implications of ubiquitous connectivity.

Key policy objectives for the LAC region

Given the multilayered convergence of networks and services, policy makers are reassessing their policy and regulatory frameworks to adjust them to current and future developments. Policy objectives like those exemplified below should be at the centre of convergent policy:

-

Expand access to and use of services, applications and content. Users should be at the centre of communication policies. Policy makers should focus on frameworks that ensure that consumers and businesses benefit from greater choice in convergent networks and services over connectivity, access and use of IP-based services, applications, content and terminal devices. Consumers should be able to access any service at any time and from any place, and the regulatory framework should not only allow but facilitate the development of convergent services. Consumer choice, consumer protection and enforcing consumers’ rights should be the priority, no matter what the supporting technology and type of provider supplying the service.

-

Encouraging investment and competition in a convergent environment. Policy makers should establish an environment conducive to competition and investment. The goal should be for users to affordably and efficiently access the multitude of bundled or standalone voice, data and video services in the IP convergent world provided by such actors as access and content providers (as discussed in Chapter 4 on competition and infrastructure bottlenecks).

-

Promoting the free flow of information and innovation. Governments should promote the free flow of information both within and outside their borders to spur innovation, knowledge sharing and trade. Policy makers need to ensure the open, distributed and interconnected nature of the Internet and the functioning of its architecture and interoperability.

Tools for measurement and analysis in the LAC region

To assist policy makers in fulfilling their objectives, it is crucial to conduct regular assessments of the rapidly changing and converging communications ecosystem. Policy makers need sound evidence to construct a policy framework adapted to the challenges of convergence. The indicators below offer a roadmap of areas where data is needed to understand some of the salient issues of convergence.

In relation to understanding the main players in the converging ecosystem, the following indicators are important:

-

number of subscribers and revenues of integrated service operators (offering either fixed and mobile services or voice and broadcasting services) and data on market shares and evolution trends (as recommended in Chapter 4)

-

data on OTT Internet providers competing for “traditional” communication services (such as voice and audio-video services or Voice over Internet Protocol [VoIP]), including collection of number of subscribers, revenues and any other data that would be relevant for understanding competition trends and the evolution of the market.

To assess the state of bundled services, it is necessary to carry out:

-

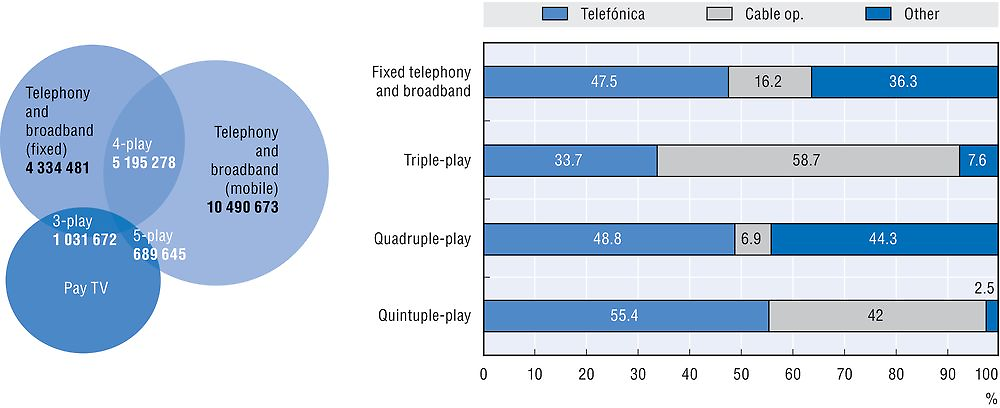

collection of data on bundled services, such as the number and percentage of bundled services, prices paid, data caps and length in time of the offer (Figure 7.1)

-

development of methodologies for market analysis of convergent offers.

Source: Adapted from CNMC (2014), Informe Económico de las Telecomunicaciones y del Sector Audiovisual 2014, http://data.cnmc.es/datagraph/files/Informe%20Telecomunicaciones%20CNMC%202014.pdf.

The exercise of benchmarking the Internet’s openness is a complex one and demands, at least:

-

Compilation of quantitative and qualitative information and analysis of any complaints or reports of blocking and throttling by consumers and service providers (including conflicts between operators).

-

Collection of information on peering and transit agreements for monitoring the interconnection market.

-

Collection of information on bottlenecks and restrictions to openness across the whole value chain for broadband-based services (network providers, as well as content, application and terminal equipment providers).

-

Collection of data on zero rating offers, when they are permitted and exist. Information about any other offers where broadband access to contents and application is restricted is also useful to assess trends, bottlenecks and dominance issues.

-

Measuring the extension of use of IPv6 in the country and the proportion of government services supported by IPv6 (Box 7.1).

Establishing metrics to trace the progress of IPv6 adoption is not a simple task. Over the years, a variety of approaches and associated measurements have been attempted, reflecting the fact that the Internet is not a single integrated system but a collation of component subsystems, so that IPv6 measurements can be performed within any particular subsystem. The list below shows several possible measurements at the level of different sub-systems, giving a snapshot of the overall transition:

-

Measurements using the routing system: The Internet routing table can be used to track the number of advertised routes that constitute the IPv4 Internet, which may be compared with a comparable count of the number of routes in the IPv6 protocol. A complementary measure is to compare the number of unique autonomous system numbers contained in the routing table, which indicate the number of entities that have IPv6 networks interconnected to the Internet.1

-

Measurements using the domain name system: The domain name system can provide a useful measurement, since only domain names that can be resolved to an IPv6 address will be able to be accessed. One approach is to use the most common source of popular domain names, the Alexa list, and query this set of domains over time to establish the proportion of the names with an IPv6 address.2

-

Measurements using Internet traffic statistics: Another option is to look directly at traffic volumes in IPv4 and IPv6. Although most such data is generally considered to be proprietary and is not released publicly, an increasing number of Internet exchange points publish data about their volumes of IPv6 traffic so that estimations of the adoption over time can be made.3

-

Measurements of end client capabilities: For an end client system to be able to make a connection using IPv6, all the Internet subsystems must also be functional in supporting IPv6. One simple way of measuring the number of IPv6-capable clients is to use a dual-stack service point and offer both IPv4 and IPv6 capability. Counting the number of systems that prefer IPv6 to IPv4 gives a good indication when the sample is large enough.4 Another measurement technique is to carry out IPv6 connectivity tests with a sample of clients to determine their preferences.5

← 1. RIPE NCC measures the number of IPv6-enabled networks in a country. See http://v6asns.ripe.net/v/6?s=_ALL.

← 2. Lars Eggart started a study using this approach in 2007. The current results can be seen at www.eggert.org/meter/ipv6.

← 3. PCH maintains a directory of Internet exchanges with traffic statistics for IPv4 and IPv6 subnets. See www.pch.net/ixpdir.

← 4. Google measures the number of end hosts preferring to use IPv6 on its service infrastructure. See www.google.com/ipv6/statistics.html.

← 5. APNIC Labs measures IPv6 capability per country using this technique (APNIC, 2016).

Source: OECD (2010), Internet addressing: Measuring deployment of IPv6, www.oecd.org/sti/ieconomy/48459831.pdf.

Providing reliable measures of convergence is an ongoing exercise. It involves improving collection of network parameters, and surveys and statistical systems to measure the changing access and use of communication networks by consumers, businesses and institutions. This is particularly important in preparing for convergence trends.1

A major challenge to benchmarking convergence lies in the fact that most regulatory authorities do not have the legal competency to request information from many of the service providers (e.g. OTT) that are not classified as their traditionally regulated communication service providers. This absence of mandate affects the assessment of the impact of these new services and limits the ability of regulators and policy makers to obtain a clear picture of market developments and progress on policy objectives.

The solution to this challenge may be to expand the scope of the information-gathering mandate, while making sure not to overburden firms and taking advantage of new data collection and analysis methods. For example, the exploitation of large volumes of data or “big data” (OECD, 2015) may serve in the future to satisfy policy information requirements. New methods for collecting statistical information and the data produced by them have been receiving considerable attention, due to their timeliness, detail and frequency. They are likely to be increasingly used by national statistics offices and regulators to complement their traditional statistics on issues such as quality of service, security incidents and price statistics (Reimsbach-Kounatze, 2015).

Overview of the situation in the LAC region

The LAC region has seen different levels of development in the implementation of convergence-related regulation and policies. While some countries in the region have been at the forefront of some issues and policy development, such as on network neutrality and IPv6, a general overview of the region shows that most countries still have not addressed key issues related to convergence. It may be the case that many of these emerging issues have yet to affect LAC countries as much as some OECD countries. This is likely to change as broadband penetration rates increase in the LAC region.

Converged regulators

In the LAC region, discussions towards reforming regulators to create converged agencies are still in their beginning. In LAC, only the recently established Mexican Instituto Federal de Telecomunicaciones (IFT) and the Argentinean Ente Nacional de Comunicaciones (Enacom) can be considered fully converged regulators (Box 7.3). For the OECD/IDB questionnaire for this report, Jamaica reported that it was conducting studies to establish a single information and communications technologies (ICT) regulator. This would involve the potential merger of the Spectrum Management Authority, the telecommunication functions of the Office of Utilities Regulation and the spectrum functions of the Broadcasting Commission. Additionally, Colombia is going through a public consultation process to evaluate the possibilities of establishing a converged regulator (Box 7.3).

Reassessing the role of the regulator in light of current and future convergence trends is useful, as it brings into focus the need for changes in regulatory frameworks, the implementation of these frameworks and the need to avoid inconsistent regulation.

Licensing regimes

The simplification of the licensing regime is another area in which little development has been undertaken, even when no spectrum licence is involved. Most countries in the region still use individual licences and/or concessions for specific services, when convergence trends call for general authorisations covering any service or combination of services. Developing more affordable broadband services and a policy framework prepared for the 21st century requires, among other mechanisms, lowering regulatory entry barriers whenever possible, such as through general authorisations.

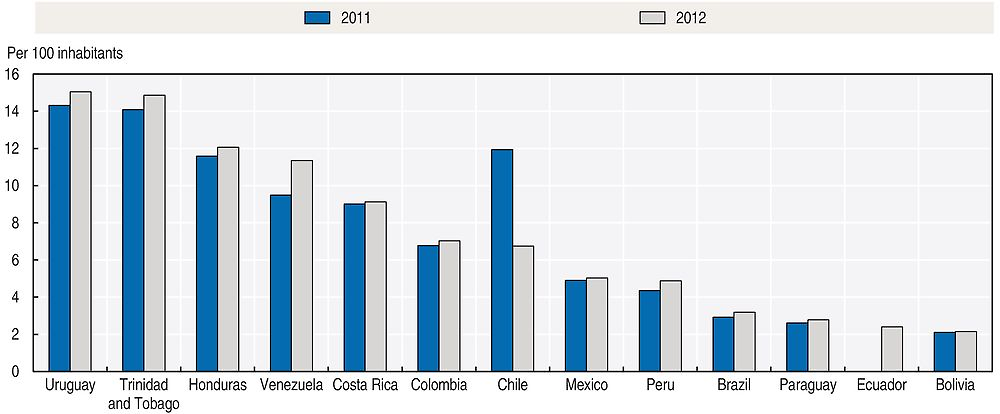

Bundling practices

The offer of multiple services over the same network is not a new phenomenon in the LAC region. Since the mid-2000s, it has seen bundling of communication services, at least of two or three fixed communication services. This was driven by cable television providers who were able to provide bidirectional services, especially voice telephony and broadband Internet access. It should be stressed that television services, especially free-to-air television, still play a central role in LAC economies, as in many OECD countries, despite increasing reports of “cord-cutting” trends as some users migrate to video on demand (VoD) subscription services.2 With the exception of Chile, terrestrial multichannel television subscriptions, for example, witnessed continued growth in the LAC region (Figure 7.2).

Source: ITU (2015), ITU World Telecommunication/ICT Indicators Database, www.itu.int/en/ITU-D/Statistics/Pages/publications/wtid.aspx.

Despite their role in the region, many LAC telecommunications and cable operators have not been leaders in shifting their networks and businesses toward advanced services and bundles. However, this situation is changing, driven by demand and market pressures caused by OTT players competing for customers, as well as opportunities for integrated operators owning both fixed and mobile networks.

For this report, data were gathered on the services offered by leading operators in the region. Among some 97 operators (MNOs and MVNOs) in 26 LAC countries, close to 40% offered some type of bundled communication service (including at least a double-play of fixed broadband, fixed voice, television or mobile services). The majority, that is 60% of operators, did not offer any type of bundled services. The most common bundle in LAC is the triple-play, with fixed broadband, fixed voice and television. Quadruple-play services are rare, found in Brazil (Vivo, Claro and Oi), Barbados (Flow), the Dominican Republic (Claro) and Jamaica (Flow). The few quadruple-play services tend to be flexible and allow users to choose and arrange services with different characteristics as they see fit.

Despite the lack of widespread quadruple-play offers, the LAC telecommunication market shows signs of innovating on bundling with OTTs and other agents (such as banks and retail shops). Indeed, the review of services for this report suggest a growing trend in the region of reaching out to partners and added services to retain and gain new customers. This is undertaken by offering a range of services via set-top boxes or mobile apps of VoD content, music streaming, cloud storage (e.g. mClou from Movistra in Chile) and mobile payments (e.g. Vivo’s Zuum in Brazil, TigoMoney in Honduras and Paraguay and Orange’s M-peso). Operators in the LAC region are increasingly adding to their own services, the “premium” subscriptions of other digital partners such as Evernote (i.e. note taking and cloud storage) and Duolingo (i.e. language learning), as well as services from partners from other sectors such as e-book publishers (e.g. Vivo’s Nuvem de Livros in Brazil) and banks.

Retail chains in the LAC region, as in OECD countries, are beginning to create their own MVNOs. This often involves converting consumers’ loyalty to their retail chain to minutes of calls, such as the MVNO Móvil Éxito (using Tigo’s network) in Colombia.

As a regulatory response to that trend, according to the OECD/IDB questionnaire, half of LAC countries require that operators that offer communication services as a package (or bundle) also offer the different elements on a stand-alone basis. In addition, in just over half of LAC countries, whenever bundled services are sold (including handsets and mobile telecommunication services), companies are also required to provide invoices with information on the price of individual services and products.

In addition to these obligations for bundles related to consumer protection and information, competition authorities and sector regulators in the region should be ready to address the challenges arising from this trend, such as conducting market analysis, definition and competition enforcement in a rapidly changing ecosystem. In the LAC region, Colombia, Costa Rica and Nicaragua report that they include bundling considerations in their competition monitoring frameworks. Good practices on these issues will be addressed in the next section of this chapter.

VoIP regulation

In some LAC countries, Voice over IP (VoIP) services are subject to the general telecommunications regulatory framework. In others, VoIP services are framed in specific instruments. In 2015, according to information provided by countries in the OECD/IDB questionnaires, just over half of the LAC countries (56%) had VoIP services subject to general telecommunications regulation. Additionally, 31% stated they had specific policies or regulations to deal with VoIP. In all LAC countries analysed, VoIP is allowed, and no regulatory restrictions were found. Further examples of VoIP regulation in the region are included below (Box 7.8).

Internet openness

In OECD countries, a key principle for policy making related to the digital economy has been the concept of “Internet openness”, with governance approached through co-operation, using a multi-stakeholder model.3 In 2014, Brazil invited governments and other stakeholders from around the world to pursue a similar path, convening the NetMundial meeting (as discussed below). Alongside their participation in both these events, a number of LAC countries have been at the forefront of international discussions on issues such as network neutrality and IPv6.

On network neutrality issues, some countries, notably Chile (2010), Brazil (2014), Colombia (2011) and Ecuador (2015), have taken decisions to prohibit blocking, throttling and paid prioritisation by broadband Internet access providers (Box 7.12). Other countries, such as the Dominican Republic, Guatemala, Suriname, Trinidad and Tobago and Uruguay, are reported to be carrying out consultations on the topic. Policy makers in the region appear to be inclined to lay out principles to ensure network neutrality. Based on the rationales given by the initial countries to do so, they see this as essential to stimulate competition, promote innovation on the margins and ensure that consumers are able to access any lawful content, application or service provided over the Internet. According to the responses collected from the OECD/IDB questionnaire for this report, ten countries said they now have or are planning to introduce regulation addressing network neutrality.

Although principles related to network neutrality have been introduced in a number of countries in the LAC region, their interpretation or implementation may vary for fixed or mobile networks and for different commercial developments. A case in point is the approach taken by some authorities on the practice of “zero rating”, where data for specific applications or services are not charged relative to other usage. Zero rating is an issue currently being debated in LAC countries, and careful consideration by authorities should be given to this question and its effect on different policy objectives (such as affordability of services and competition dynamics). The good practices section of this chapter will discuss this issue.

Zero rating is becoming increasingly popular among LAC operators. Out of the 97 operators reviewed in the LAC region here, at least 23% offered some type of zero-rated offers. Examples of zero-rating social media applications (such as Facebook, WhatsApp, Twitter and Instagram) can be found, within different schemes, in Barbados, the Plurinational State of Bolivia (hereafter “Bolivia”), Brazil, Colombia, the Dominican Republic, Ecuador, Guatemala, Honduras, Jamaica, Mexico, Panama, Peru and Suriname. In most countries, these zero-rated services are offered under specific conditions (under a certain basic data plan, during a limited time and where VoIP services do not apply).

A few operators in the LAC region also offer music services (their own or under partnerships with OTTs such as Spotify, Deezer and Napster) under similar zero-rated plans that do not subtract from users’ data caps, such as the one offered by Tigo, Honduras. Others have started offering their own zero-rated chat apps to compete with OTT services, either native in their devices or downloadable in app stores, such as Twnel from UFF!, a MVNO operating on Tigo’s network in Colombia.

IPv6

As for IPv6, the Americas region is a leader, with 12.74% of end hosts capable of undertaking an IPv6 network transaction, followed by Europe, Oceania, Asia and Africa. In the LAC region, the five leading countries in IPv6 adoption are Peru, Ecuador, Brazil, Bolivia and Trinidad and Tobago, according to the measurements of their end-to-end IPv6 capabilities (Table 7.1). Other measurement options are available (see Box 7.1).

Good practices for the LAC region

Guiding principles for adapting regulatory frameworks for convergence

Given the increasing convergence towards IP broadband networks, it is necessary to review whether existing policy and regulatory frameworks will continue to apply and what measures should be taken to facilitate and seize the benefits of the transition.

A first step in assessing whether to update the current communication policy and regulatory frameworks involves evaluating if the reasons that inspired and justified their introduction still hold in the new environment. Such an evaluation should consider that regulation is usually applied to correct a market failure, such as lack of competitive choice, resource scarcity or to safeguard public policy objectives (e.g. widespread access, public safety, emergency communications, economic growth, privacy, consumer empowerment and security). In areas of traditional market failure, convergence may have created opportunities for market players to play a greater role by increasing choice and diversity and reducing scarcity, while in others, market failures may still exist.

OECD countries have carried out regulatory reforms in the light of convergence. Some of the general principles guiding such policies can be used as a source of good practices for the LAC region:

-

Simplify. The guiding principle behind creating a regulatory framework adapted to convergence should be simplification of rules and procedures. Complex regulatory systems increase the costs of transaction, especially for new entrants and new services.

-

Uphold technologically neutral regulation when possible. Technology-neutral and device-agnostic regulatory frameworks are not only desirable, but critical to enable convergence of communication services. In a context where most services are shifting to IP-based networks and content is being accessed on a multitude of platforms and devices, it is not advisable to tie general frameworks, which do not involve scarce resources such as spectrum, to specific networks, technologies or devices.

-

Promote investment along the whole value chain for broadband access services. Encouraging investment by all market players is fundamental for increasing broadband access infrastructure and services. Any regulatory reform to address convergence issues should ensure that adequate incentives exist to encourage investment both in the network layer (access and transit infrastructure deployment) and in the applications layer (innovative services using broadband access).

-

Promote competition and innovation. The promotion of competition and innovation should be maintained as a guiding principle of any policy reformulation seeking the benefits of convergence. Policy makers should promote an environment for innovation without favouring particular platforms or participants. New convergent regulatory frameworks should above all promote a level playing field.

Some countries have actively engaged in convergence reviews for telecommunication and audio-visual markets and can therefore provide some firsthand experience for the LAC region. For example, Australia’s 2012 Convergence Review conducted a comprehensive consultation process to inform the examination of the operation of media and communications regulation. It aimed to assess the effectiveness of the Australian framework in achieving policy objectives in areas of media ownership, content standards, production and distribution of local content and the allocation of spectrum.4 In LAC region, the new Telecommunications Act of Ecuador is an example of a regulatory framework that takes convergence into account (Box 7.2).

The new Telecommunications Act in Ecuador, enacted in 2015, embraces the opportunities of convergence and stipulates in its Article 12 that the Ecuadorian state will “propel the establishment and exploitation of telecommunication networks and services that promote the convergence of services, in conformity with public interests and with the dispositions of the Act and its normative”. According to the new Act, the regulator ARCOTEL will be responsible for “regulations and norms that allow for the provision of multiple services on the same network to drive, in an effective manner, the convergence of services and assist with the technological development in the country, following the principle of network neutrality”.

Source: Ecuador (2015), Ley Orgánica de Telecomunicaciones, www.arcotel.gob.ec/wp-content/uploads/downloads/2015/03/ro_ley_organica_de_telecomunicaciones_ro_439_tercer_suplemento_del_18-02-2015.pdf.

Converged regulators

Policy makers need to respond to the changes brought about by convergence, over broadband networks, with a whole-of-government approach. These changes touch on a number of different sectors, increasing the chance of overlap between the responsibilities of different agencies and ministries.5 It is important to address all market actors in any review of legal and regulatory frameworks, to ensure a balanced approach across all services. The emergence of OTT content service providers and the popularisation of triple- or quadruple-play service bundles, including premium content, for example, have made it difficult to draw boundaries between content and data transmission (OECD, 2014a). Other issues, such as must-carry/must-offer obligations, copyright and retransmission issues are not easily classified in any of the two categories (audiovisual content or telecommunication regulation). Convergent trends affect competition dynamics among broadband and content/application providers, and these need to be analysed taking a holistic approach. Likewise, cross-sector mergers and acquisitions and market analysis (of fixed and mobile, content providers and telecommunications providers or OTTs) have a profound influence on the need to reinforce collaboration between competition and communications authorities.

Several types of institutional arrangements address regulatory convergence when assigning powers to the different agencies in OECD countries. Some combine ex ante with ex post regulation, as in the Netherlands; others combine ex ante regulators of several sectors into a single body, as in Australia; and others have created a unique regulatory authority for all sectors, acting both ex ante and ex post, as in Spain. In general, converged regulators address regulatory issues holistically, and serve as a one-stop shop for stakeholders, simplifying regulatory decisions, saving public resources and facilitating knowledge sharing.

Converged regulators integrating powers for both audiovisual and telecommunications services, including content-related issues for video/television services, can assess and impose regulatory measures on the full value chain of communications services (from networks to content), identify bottlenecks and detect possible leverage of market power in adjacent markets (such as bundling issues). Converged entities that combine ex ante and ex post powers have a better ability to co-ordinate regulatory decisions, and improve consistency, coherence and enforcement.

Any reform seeking to address convergence requires new tools, procedures and updated information requirements. Collecting data from OTTs and analysing their effects on broadband markets is challenging, but needs to inform policy making and regulation. The substitutability of new services is a crucial part of convergence, as is ensuring the availability of statistical and technical skills and resources so that competition analysis can be conducted. Mexico and Argentina in the LAC region have recently joined other OECD countries, such as Australia, Canada, the United Kingdom, the United States, Hungary, the Netherlands and Spain, in introducing a converged structure for its communication authority.

Mexico

The IFT is an independent and converged regulator, established in September 2013 in the context of the constitutional reform, with the objective to promote competition and efficient development of telecommunications and broadcasting in Mexico.

Source: IFT (2016), “Objectivos Institucionales”, Instituto Federal de Telecomunicaciones, http://www.ift.org.mx/conocenos/objetivosinstitucionales.

Argentina

The Enacom was created in December 2015 as a decentralised agency with the objective of overseeing the converged sector, including Internet services, fixed and mobile telephony, radio, postal and broadcasting services in Argentina.

Source: Enacom (2016), “Que és Enacom”, Ente Nacional de Comunicaciones, http://www.enacom.gob.ar/.

Colombia

In March 2016, the Colombian Ministry of ICT started in March 2016 rounds of multistakeholder consultations in the several regions of the country to develop a new policy and regulatory framework for telecommunications and broadcasting in that country. A key issue raised, and one where consensus is emerging Is on the need to have a unified regulator to deal with convergence in communications markets. This new regulatory framework is expected to be finalised in 2017.

Licensing regimes

Licensing requirements in broadcasting and telecommunication should be reduced to a minimum, to facilitate entry of new providers and to promote innovation and competition. This can be a notification-based, class-licensing approach, as typical of telecommunication services in most OECD countries. One of the few exceptions to this rule would be services using scarce spectrum resources, where licences involve coverage and QoS obligations. In such cases, consultation with the regulatory authority should ensure that competition is encouraged. In a converged environment, the difference between telecommunications and audiovisual services may no longer be as relevant, especially in the scenario where audiovisual services are provided over the Internet. Here, it is advisable to keep licensing requirements as uncomplicated as possible. Some countries in the LAC region have made considerable progress in this respect. Peru, in 2006, Colombia, in 2009, and Mexico, in 2014, for example, have recently taken steps to simplify licensing requirements for most services (Box 7.4).

Peru

The Telecommunications Act of 2000 (Reglamento General de la Ley de Telecomunicaciones) was modified in 2006 by Law No. 28737 to include a single licence granted by the Ministry of Transport and Communications (MTC) to any public telecommunications service. The Law embodies the Peruvian government’s objective to “promote the convergence of networks and services, facilitating the interoperability of different network platforms, as well as the offering of different services and applications on the technological platform, recognising convergence as a fundamental element to the development of different regions in the country”. Available at http://transparencia.mtc.gob.pe/idm_docs/normas_legales/1_0_892.pdf.

Colombia

The licensing regime implemented by Law No. 1341 of 2009 (Ley de TIC) laid out a single-licensing regime in Colombia (Título Habilitante Convergente) that only requires registration, reducing administrative barriers and easing the entry of operators into the market. This licensing regime aims to favour convergence and the supply of different services over the same network. However, broadcasting licences continue to require a specific licence (also simplified) and could benefit from further regulatory convergence. Available at www.alcaldiabogota.gov.co/sisjur/normas/Norma1.jsp?i=36913.

Mexico

In the context of the Constitutional Reform (2013) and the Federal Telecommunications and Broadcasting Law (2014), Mexico’s licensing regime moved to a single-licensing system (closer to class licensing) which allows the provision of all telecommunications and broadcasting services with a single licence (with the exception of services involving radio-electric spectrum or orbital resources), awarded for renewable 30-year terms. To obtain a unique concession, a request that complies with the minimum requirements must be submitted. The request is then reviewed by the IFT within 60 calendar days, with the understanding that the IFT will grant the concession after this period, assuming all requirements are met. This single license however is not available to all actors in the Mexican market, as additional regulatory requirements are currently applied to Mexico’s incumbent operator (Telmex). Available at http://www.diputados.gob.mx/sedia/sia/spi/SAPI-ISS-64-15.pdf.

The model for authorisation applied in the European Union to provide electronic communications services is defined in a directive on the authorisation of electronic communications networks and services (Authorisation Directive) 2002/20/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of March 2002 (updated in 13 November 2009).

According to Article 3, member states must ensure freedom to provide electronic communications and services, and companies may not be required to obtain explicit decisions by regulatory authorities. To get authorisation, it is enough to submit a notification with information limited to what is necessary for the identification of the provider, such as company registration numbers, and the provider’s contact persons, the provider’s address, a short description of the network or service, and an estimated date for starting the activity.

Source: http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=celex:32009L0140.

For licensing, Colombia and Mexico take a similar approach to that of the European Union, and only require previous notification to the relevant authority (Box 7.5). In the United Kingdom, television services are licensed by the Office of Communications, Ofcom, in an approximate time frame of 25 working days (non-committal) for a USD 3 500 fee. Video-on-demand services are licensed by the ATVOD (Authority for Television on Demand) based on providers’ revenue, starting at about USD 250.

In general, operators should be allowed to provide any service, facilitating economics of scope and convergent services on a national basis. This will help promote economies of scale. Any potential issue for competition and obligations should be addressed after conducting a market analysis.

Bundling practices

Broadband IP-based networks facilitate a bundling of communication services. These range from basic double-play to triple and quadruple-play offers of fixed and mobile broadband Internet access, pay-television, fixed telephony and mobile voice. Operators in the LAC region are increasingly including innovative services in their bundles, such as those resulting from partnerships with OTT providers as well as home monitoring, mobile payments, e-learning applications, computer security and cloud storage services.

Bundles can be beneficial to consumers, allowing them to purchase several services at a significant discount over the cost of stand-alone equivalents (OECD, 2011b, 2006) and can also reduce complexity of subscribing to multiple services of multiple providers. Conversely, bundling of services may also complicate choices for consumers by increasing complexity, making price comparisons more difficult, and reducing billing transparency. Operators may also benefit from bundling practices, which may lead to cost savings, through economies of scope and scale or simplified distribution and marketing. In competitive conditions, these should, in turn, benefit consumers via price reductions. Bundling services also allows for the use of a single platform (such as through the use of “boxes” that allow for the provision of triple-play bundles over the same device (OECD, 2011b).

One of the biggest challenges of bundling practices for policy makers, however, is to determine their impact on competition. Operators that are in a position to offer bundles based on their own infrastructure may leverage dominance from one market to other markets, and alternative operators may not be able to compete on an equal footing. Policy makers should consider that account bundling may be a potential barrier to competition when performing market analysis, while also taking into account the potential benefits to consumers. Some good practices in this area are summarised below:

-

Obligation to provide separate prices for stand-alone services and billing. A lack of transparent information about services and their prices makes consumer price comparisons more difficult and may lead to market inefficiencies. To facilitate consumer choice, it is good practice to require that the prices of bundled services be provided separately. Regulators and consumer-protection agencies should encourage providers to make available more information on the characteristics of packages they are selling and to make prices clear and understandable for consumers. Many regulators, including those in the LAC area, have tried to increase billing transparency by issuing regulations that require operators to disaggregate the price of each service component (including handsets, if included) in the bundle. These practices are in line with what is set out in the OECD Consumer Toolkit and its application to communication services (OECD, 2008; OECD, 2010; OECD, 2013). Additionally, websites and tools that can help users compare bundled offers are beneficial to consumers and lead to stronger price and service competition. Regulators are in a good position to provide these tools to the public (Box 7.6).

-

Monitoring the market for anti-competitive practices. Regulators and competition authorities need to work together to address problems with market dominance in bundles. They should co-operate on developing new market analysis frameworks and tools, to address issues related to bundles and cross-effects, such as those between competition in content provision and competition in telecommunications and OTT services (Box 7.7).

Colombia

To increase transparency of offered prices and to allow for users to directly compare different types of communication services and bundles, the Colombian regulator, the Comisión de Regulación de Telecomunicaciones (CRC) has issued the Comparador de Tarifas, so that users can choose to match several services and filter per region, budget, etc., to see the best available offers.

Brazil

The Brazilian regulator Agência Nacional de Telecomunicações (ANATEL) announced the creation of a mobile app for early 2016, to allow users to compare services they wish to include in their bundled plans and see the best available services in their regions. This comparison has only been made possible since ANATEL started requesting that operators offer in their websites all available stand-alone and combined offers, in an easily comparable and standardised format.1 ANATEL will gather this information, filter per region and systematise it in the mobile app.

← 1. Resolução No. 632 do Conselho Diretor da ANATEL of 7 March 2014, approved by the General Regulation for the Rights of Consumers of Telecommunications Services, www.anatel.gov.br/legislacao/resolucoes/2014/750-resolucao-632.

Source: ANATEL (2015), Projeto de aplicativo sugerido pela Anatel receberá prioridade, www.anatel.gov.br/institucional/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=688:projeto-de-aplicativo-sugerido-pela-anatel-recebera-prioridade&catid=104&Itemid=354.

Despite the growing importance of Internet-based services commonly known as “over-the-top” (OTT), their definition and implications for the analysis of telecommunications and broadcasting services does not generally have a legal status. The term OTT is commonly used but often not clearly defined. With this in mind, the Body of European Regulators for Electronic Communications (BEREC) carried out a report on OTT services, addressing their implications for competition and on the current EU regulatory framework for electronic communications (ECN/S Framework, available at https://ec.europa.eu/digital-agenda/en/telecoms-rules), which offers a useful definition and taxonomy of OTT.

BEREC defines OTT service as “content, a service, or an application that is provided to the end user over the open Internet”. This includes what is provided as content, service or application, meaning anything provided over the open Internet, generally without involvement of the Internet Access Provider (ISP for end users, in “retail Internet access markets”) in the control or distribution of the service. According to BEREC, OTT services thus include “the provision of content and applications such as voice services provided over the Internet, web-based content (news sites, social media, etc.), search engines, hosting services, email services, instant messaging, video and multimedia content, etc.”

Other taxonomies of OTT exist, for example those based on the type of service offered (as suggested in the 2014 OECD Report on “The Development of Fixed Broadband Networks” (OECD, 2014b). Others are based on business models (direct payment from users or advertisement, for example). BEREC, however, compares the relevancy of each OTT service against electronic communications services (ECS) categorisation. The taxonomy is summarised below:

OTT-0: OTT services that qualify as ECS (e.g. OTT voice services with the capacity to make calls to PSTN/PATS as a substitute for traditional voice services).

OTT-1: OTT services that do not qualify as ECS, but potentially compete with ECS and are therefore relevant for market analysis to assess dominance (e.g. OTT voice or instant-messaging services that do not convey signals to the PSTN/publicly available telephone service (PATS) and that require the caller and called party to subscribe to the same service).

OTT-2: Other OTT services that do not qualify as ECS or compete with them, but which are relevant for ECS analysis, since they are sometimes bundled with ECS. These might include OTT non-voice and non-instant messaging that aggregate value to ECS bundles through services of e-commerce or video and music streaming.

BEREC’s proposal may serve as a guide to regulators to evaluate the standing of certain OTT services within their national legal definition of electronic communication services. Categorising different types of OTT services according to their interaction with existing definitions may serve as an exercise for monitoring new anti-competitive practices on the market and to benchmark possible changes towards a converged legal framework.

Source: BEREC (2015), “Draft Report on OTT Services”, http://berec.europa.eu/eng/news_consultations/ongoing_public_consultations/3320-public-consultation-on-the-draft-berec-report-on-ott-services; OECD (2014b), The Development of Fixed Broadband Networks, http://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/science-and-technology/the-development-of-fixed-broadband-networks_5jz2m5mlb1q2-en.

Some additional good practices covered in Chapter 4, on competition and infrastructure bottlenecks, are especially relevant in addressing competition issues in a convergent world: encouraging inter-platform competition to ensure replicability of bundle offers by alternative operators and regulating wholesale markets when needed.

Policy makers should, when possible, carefully consider exclusive long-term deals for premium content, especially when supply of premium content is bundled with broadband access. The impact on market competition of premium content acquisition by dominant providers should be assessed with caution. If needed, obligations to share content can be mandated to ensure competition.

VoIP regulation

Traditional telecommunication operators have widely regarded VoIP services provided by third parties as a threat to their revenues from legacy voice services. In response, some of them have excluded, surcharged and restricted VoIP services, or used price discrimination, absent explicit network neutrality rules or when permitted by the regulator.

Efforts to block VoIP service have not successfully discouraged offers by content and application providers, such as Skype or Viber. Other OTT messaging applications equipped with voice features such as WhatsApp, Facebook Messenger, FaceTime and LINE, have proven popular in the LAC region, as they have elsewhere. Some operators have sought to restructure tariffs, such as by including unlimited voice and text for particular locations or destinations, or have included their own or third-party VoIP pre-installed applications in order to increase the attractiveness of their own services in the face of competition from OTTs (e.g. Twnel from Tigo Colombia).

Authorities should analyse if and when VoIP services should be regulated in their countries against their policy objectives. In many OECD and LAC countries, regulators have taken the approach that VoIP providers that act as traditional voice operators and connect to the PSTN (having numbers assigned and a certain critical mass of subscribers or revenue, for example) should be subject to similar obligations. In Japan, there are various requirements if a telephone number is assigned. At the same time, other countries such as Australia, impose these obligations only on network operators.

A neutral approach focusing on services provided rather than technology may help to clarify some issues for applying obligations and including VoIP in numbering regulation frameworks. Belize and Colombia offer an interesting example of technology neutrality, while Chile is a good case of allocating “nomadic” or “non-geographic” numbers for VoIP services (Box 7.8). Other issues such as number portability are likely to arise in the future in the LAC area. In most OECD countries, portability between fixed voice service and equivalent VoIP service has already been instituted. In addition, local number portability to VoIP and portability between VoIP services can become more important if they become increasingly used to replace fixed telephony.

Belize

Since 2006, Belize has categorised VoIP services into two types in Belize: services where the end-user is not publicly available by means of an assigned unique telephone number, and those where the end user can be reached via an assigned telephone number (PSTN). The first type is not subject to licensing procedures with the regulator, while the second category is, including those used in private networks. They are also subject to the provisions of consumer protection, emergency calling and universal access. See PUC (2006).

Chile

Since 2007, Chile has regulated VoIP services that offer calls using PSTN. These services are subject to licensing regimes and have had nomadic numbering assigned by the Chilean regulator, the Subsecretaría de Telecomunicaciones (SUBTEL). They are also subject to interconnection, public security (interception), emergency services, among several other obligations of traditional voice services. See SUBTEL (2007).

Colombia

Due to the technology neutrality principle in Colombia established under the Law 1341 of 2009, all regulatory measures, including the assigning of numbers, are equal to all telecommunications network and service providers, without discriminating by technology. Therefore, no specific measures are applied to VoIP in the country. See Colombia (2009).

Costa Rica

VoIP fixed telephony was made equivalent with the traditional basic telephone service and is subject to the same regulations for telecommunications services available to the public.

Content distribution and regulation

Convergence has given rise to new models for content distribution, where consumers have gained the ability to access content over different networks and devices and interact with multiple providers. New digital content distributors, such as OTT video providers (e.g. Magine TV, Netflix, Sling TV and Hulu), now coexist and competition with traditional content providers. Moreover, users are producing content themselves. Seamless access to content providers over the Internet is fundamentally challenging the traditional location, time of day; device and technologically based regulatory frameworks that are widely in place to meet policy objectives in different countries.

Policy objectives in media and broadcasting have traditionally included goals such as ensuring diverse ownership, plurality of opinions, meeting community standards for programmes for children, protection of intellectual property rights and the production and distribution of local content. During convergence reviews, long-held objectives are unlikely to be changed. Rather, the issue is whether existing approaches are meeting these objectives and whether modifications can better meet such goals.

Broadband networks bring with them changes to the nature of media consumption. Some are more passive and linear, and most importantly, requiring a certain amount of scarce resources, such as spectrum frequencies (e.g. television and radio). Others are more interactive, transient and allow more freedom to shift providers or platforms, such as Internet-based services. Service providers can be classified by their reach, revenue and type of content created. Accordingly, content regulation should be as technology neutral and flexible as possible, but also account for the nuances of how content is delivered and to whom.

Each public policy objective regarding content regulation should be periodically reviewed. Any decisions taken should be applied consistently and clearly, as technological change continues and as convergence over broadband networks integrates a wider range of devices, services and content. At the same time, attention needs to be paid to the opportunities convergence makes possible, including empowering consumers, enhancing competition and innovation and upholding freedom of expression.

These innovations in the video delivery and content navigation technologies have convinced a majority of OECD countries to adopt a less onerous licensing regime. In many OECD countries, audiovisual services provided over the Internet are not subject to the same set of rules as traditional broadcasters and a few OECD countries have relaxed their broadcasting obligations (Box 7.9).

Canada

The Canadian regulator, Canadian Radio-Television and Telecommunications Commission (CRTC) has long promoted content created by Canadian artists by imposing obligations on broadcasters. However, in March 2015, after a long public consultation, the CRTC relaxed its Canadian content quotas on television. The CRTC chairman acknowledged that technological change has upended the TV business model and that the industry is an “age of abundance”.

Source: CRTC (2015), “CRTC Chairman speech to the Canadian Club of Ottawa”, http://business.financialpost.com/fp-tech-desk/crtc-relaxes-quotas-on-canadian-content-for-tv-broadcasters?__lsa=cda6-e620#1.

European Union

The European Union’s Audio-visual and Media Services (AVMS) Directive regulates television broadcasts and on-demand audiovisual media services,1 for which providers have editorial responsibility. The AVMS Directive includes a set of criteria to establish whether a given service falls under the scope of the Directive: i) editorial responsibility by the media service provider; ii) the principal purpose is the provision of programmes; iii) provided to the general public; iv) in order to inform, entertain or educate; v) service normally provided for remuneration, and so on. This list is not exhaustive. It should be noted that these criteria are technology-neutral, as they refer to the characteristics of the service provided, as opposed to the underlying technology. Furthermore, in July 2015, the EU Commission published a public consultation on the review of the AVMS Directive that sought out the views of all interested parties on Europe’s audiovisual media landscape, and a full report on the results of the consultation is forthcoming.

← 1. In the Directive, the term “on-demand audiovisual media service” is defined as follows: “‘On-demand audiovisual media service’ (i.e. a non-linear audiovisual media service) means an audiovisual media service provided by a media service provider for the viewing of programmes at the moment chosen by the user and at his individual request on the basis of a catalogue of programmes selected by the media service provider” (European Parliament and CoE, 2010).

Source: European Parliament and CoE (2010), Audiovisual Media Services Directive – 2010/13/EU, http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32010L0013&from=EN.

Internet openness

The Internet’s decentralised nature and openness to new devices, applications and services has played an important role in advancing convergence and in its success in fostering the free flow of information, innovation, creativity and economic growth. This openness stems from the continuously evolving interaction among and independence from the Internet’s various technical components, enabling collaboration and innovation while continuing to operate independently of one another. It stems also from globally accepted, consensus-driven technical standards that support global product markets and communications.

At the international level, the roles, openness and competencies of the global multi-stakeholder institutions that govern standards for different layers of Internet components have served to expand the decentralised networks that the Internet is made up of today. The OECD Internet Policy Making Principles (2011) offer a reference framework, not only for OECD countries, but also those in the LAC region, as indicated by its endorsement by countries such as Costa Rica and Colombia (Box 7.10).

In 2011, consistent with the growing recognition of the critical role played by ICTs and broadband networks, and in particular the Internet, the OECD community came together through a multi-stakeholder process, to draw on the experience of participants in good practice for Internet policy and governance, which led to the adoption of the OECD Principles for Internet Policy Making, a cornerstone of the OECD’s work in the area. The Principles are:

-

promote and protect the global free flow of information

-

promote the open, distributed and interconnected nature of the Internet

-

promote investment and competition in high- speed networks and services

-

promote and enable the cross-border delivery of services

-

encourage multi-stakeholder co-operation in policy development processes

-

foster voluntarily developed codes of conduct

-

develop capacities to bring publicly available, reliable data into the policy-making process

-

ensure transparency, fair process, and accountability

-

strengthen consistency and effectiveness in privacy protection at a global level

-

maximise individual empowerment

-

promote creativity and innovation

-

limit Internet intermediary liability

-

encourage co-operation to promote Internet security

-

give appropriate priority to enforcement efforts.

Source: OECD (2011a), OECD Principles for Internet Policy Making, https://www.oecd.org/sti/ieconomy/oecd-principles-for-internet-policy-making.pdf.

At the national level, multi-stakeholder arrangements for governing Internet issues are also advisable, as exemplified by the case of CGI.br in Brazil or the Internet Advisory Board in Costa Rica (Box 7.11). Maintaining technology neutrality and appropriate quality for all broadband networks and services is also important in ensuring an open and dynamic Internet environment.

Brazil

The Brazilian experience in promoting a multi-stakeholder approach to Internet policy making has received international praise and contributed to the organisation of the 2014 NETMundial conference in São Paulo to discuss principles and a roadmap for Internet governance. Brazil’s success in implementing a participative and cross-sectoral framework for Internet policy making is the result of an innovative framework embodied by the Internet Steering Committee (CGI.br).

The CGI.br is responsible for establishing strategic directives related to the use and development of the Internet in Brazil, as well as guidelines for the implementation of Domain Name registration, allocation of IP (Internet Protocol) and administration of the Top Level Domain (TLD) “.br”. The CGI.br follows a multi-stakeholder model and consists of 21 members, including nine representatives from federal government, four from the business sector, four from civil society, three from the scientific and technical community, and a renowned Internet expert. Typically, this steering committee meets once a month and publishes its agendas and minutes online. A group of multi-sectoral consulting chambers support the steering committee by discussing specific topics in depth, such as changes to the technical structure of Port 25, which resulted in a drop in online spam.

The Internet Steering Committee’s decisions are supported and executed by the Centre for Information and Co-ordination (NIC.br), established in 2005 as a nonprofit organisation. NIC.br has a mandate to register and maintain .br domain names, respond to and treat security incidents, promote studies, measure indicators and recommend procedures and standards, among other operational assignments. CGI.br and ANATEL also counsel the President of the Republic on implementing exceptions to the network neutrality principle.

Source: CGI (2015), Comité Gestor da Internet no Brasil, www.cgi.br/.

Costa Rica

Costa Rica’s Internet Advisory Board is a multidisciplinary group composed of representatives from various sectors in Costa Rica, and has as its main purpose to discuss issues in the field of Internet and the Superior Domain .cr to encourage and promote the country’s development. The role of the Advisory Board is to discuss issues of national scope proposed by NIC Costa Rica (a unit of the National Academy of Sciences) and/or Advisory Board, related to the development, universal access and operation of the Internet; make policy recommendations to NIC Costa Rica; and create working groups to follow up on specific issues.

Source: Consejo Consultivo de Internet (2015), cr! Consejo Consultivo de Internet, https://consejoconsultivo.cr/.

Broadband networks are a key platform for innovation, economic opportunities and civic engagement. The extent to which these networks are open to facilitating these objectives has thus become a chief concern for all stakeholders. In the network neutrality or traffic prioritisation debates, different actors take their own assessment of the value that others bring to commercial negotiations over the exchange of traffic. For the most part, the system works with extraordinary efficiency, and most of the thousands of networks that exchange Internet traffic do so without a written contract or formal agreement.

In this increasingly converged environment, Internet service providers (ISPs) become gateways for content and applications, as they control content providers’ final access to consumers. This does not mean that IP termination for content and applications should be regulated. The nature of these markets tends to be two-sided, and content providers also have considerable bargaining power. Policy makers should monitor for any market failures and, above all, encourage competition for broadband access. Some good practices related to Internet openness issues are provided below:

-

Policies for traffic prioritisation/network neutrality. Prioritisation of certain applications or services may raise competition concerns related to the leveraging of dominant positions or favouring one competitor against another. If there are no particular issues in a market, given sufficient competition, and the available information suggests an efficient exchange market is in place, policy makers can forbear from direct action. This strategy is reliant on policy makers and regulators having appropriate information in areas such as the competitiveness of broadband access, the effectiveness of transit and peering markets and the efficiency of IXPs. Policy makers in some countries, including in the LAC region, have chosen to directly disallow prioritisation by ISPs, based on their assessment of available competition or its potential implications for competition (Box 7.12). In these cases, they should allow reasonable traffic management and the development of new innovative services that may need prioritisation, such as those in the telemedicine field.6 There should be no need in principle to act at the wholesale level, such as regulating interconnection agreements, as long as a market has sufficient competition.

-

Policies to address zero-rating practices. Offering certain services based on a zero rate to consumers is becoming a common practice in some countries in the LAC region. This practice may in some circumstances promote competition, in markets with a sufficient number of players to offer choices for consumers, benefiting existing and new users by providing innovative and less expensive offers. However, zero rating may also raise serious concerns in markets with insufficient competition. It may favour some applications or over-the-top service providers, very likely already dominant, at the expense of smaller or emerging ones. Additionally, zero-rate offers that result in “walled gardens” may limit the Internet experience of consumers, raising public policy concerns. In this context, when zero rating is permitted, it is advisable that policy makers monitor its existence and effects, and continue to encourage competition at the broadband services level, since zero rating becomes less of an issue when there is increased competition and higher data allowances. Directly prohibiting zero rating may have implications for a market where there is lower competition for transit and may reduce the effectiveness of peering. Nevertheless, in any market with limited competition for access, zero rating can affect competition among content providers. In general, zero-rating effects on competition and on consumers’ experience should be analysed on a case-by-case basis. Depending on the situation, regulators may consider that zero rating should not be allowed to preserve competition and/or Internet openness, while in other situations, mainly when there is sufficient competition, it may not have enough negative implications to justify intervention.

-

Limiting liability of Internet intermediaries. Internet intermediaries (e.g. ISPs, search engines, portals) host, transmit and index and give access to content originated by third parties. These are critical attributes to fostering digital economies and the benefits they offer. A good practice for policy makers is to set appropriate limitations of liability for Internet intermediaries with regard to third-party content. Internet intermediaries can play an important role by addressing and deterring illegal activity, fraud and misleading and unfair practices conducted over their networks and services. Policy makers may, therefore, choose to convene stakeholders in a transparent, multi-stakeholder process, to identify the appropriate circumstances under which Internet intermediaries might take steps to educate users, assist rights holders in enforcing their rights or reduce illegal content (OECD, 2011). Any policy in this regard should seek to minimise burdens on intermediaries and in ensuring legal certainty for them.

Chile

In 2010, Chile was among the first countries to enact a specific law to protect network neutrality in electronic communications. The Network Neutrality Act, Law No. 20.453/2010, promotes transparency, by requiring the publication of the characteristic of Internet access, speed, quality of link, distinguishing between national and international connections and the nature and guarantees of the service; and prohibits blocking, interfering, discriminating, disrupting or restriction of any content, application or legal service through the Internet. Furthermore, the Act adopts a flexible view of traffic discrimination, by granting suppliers the ability to adopt measures or actions needed for traffic management and network administration, provided they are not intended to affect free competition or could do so.

Source: SUBTEL (2014), “Ley de Neutralidad y Redes Sociales Gratis”, Subsecretaria de Telecomunicaciones, http://www.subtel.gob.cl/ley-de-neutralidad-y-redes-sociales-gratis/.

Brazil

In 2014, the Brazilian Congress passed the Marco Civil da Internet, Law No. 12.965/2014 (or the Internet Civil Framework Act), which, among consolidating rights, duties and principles for the use and development of the Internet in Brazil, enshrined the principle of network neutrality. Its importance lies not only in its principles, but also in the way in which it was drafted, based on an open and collaborative consultation process, implemented at an unprecedented scale across the country. On network neutrality, the law sets the tone for promotion of transparency of information, by asking service providers for clear and complete information on service provision contracts, where details of the data protection regime and network management practices should be included; and for non-blocking, by affirming that it is a duty of the entity responsible for the transmission, switching or routing to treat all data packages equally, without distinction on grounds of content, origin and destination, service, terminal or application. The law goes on to prohibit traffic discrimination or degradation, which can only be implemented as a result of essential technical requirement and prioritisation of emergency services (regulatory exceptions are under discussion with several stakeholders).

Source: Brazil (2014), Marco Civil da Internet, www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_ato2011-2014/2014/lei/l12965.htm.

Colombia

Since 2009, the Colombian ICT Law has ensured network neutrality in principle, by guaranteeing users access to services and lawful content and applications of their choice. In addition to the general ICT law, Resolution 3502 of Colombia’s regulator, the Comisión de Regulación de Telecomunicaciones (CRC), passed in 2011, developed the principle laid down by Resolution CRT 1740 in 2007 and adopted some network neutrality principles for fixed ISPs, similar to those laid down by the FCC in the United States. These are: i) free choice; ii) non-discrimination; iii) transparency; and iv) and free information. The CRC Resolution incorporated two key elements: first, ensuring appropriate conditions regarding net neutrality by establishing defined QoS levels for access to the Internet, and second, clarifying the conditions for content blocking due to security reasons. The latter aimed to prevent ISPs from blocking, interfering with, discriminating or restricting the user’s right to use, send, receive or offer any content, application or service over the Internet. This resolution stated that traffic management should be applied in a non-discriminatory way with respect to content providers and allows for ISPs to engage in prioritisation of “time-sensitive traffic” and QoS management only if it does not degrade the user’s experience of the services provided.

Source: CRC (2011), Resolución No. 3502 de 2011, https://www.crcom.gov.co/resoluciones/00003502.pdf.

Peru

Since 2014, the Regulation on Quality of Service (Reglamento General de Calidad de los Servicios Públicos de Telecomunicaciones)1 has stipulated that telecommunications operators or ISPs that provide services for Internet access will not be allowed to limit the use of any application in any path (user-ISP or ISP-user). Moreover, in 2015, the Law for Broadband Promotion and Construction of the National Fibre Backbone (Ley de Promoción de la Banda Ancha y Construcción de la Red Dorsal Nacional de Fibre Óptica), Law No. 29904, established the principle of network neutrality, defined as “freedom of the use of applications and protocols of broadband”. Under Article 6 of this Law, providers of Internet access will respect network neutrality and are prohibited from blocking, interfering, discriminating or restricting the right of users to use an application or protocol, independent of its origin, nature or property.

Source: OSIPTEL (2014), Resolución de Consejo Directivo No. 12302014-CD-OSIPTEL de 10 Octobre 2014, https://www.osiptel.gob.pe/Archivos/ResolucionAltaDireccion/ConsejoDirectivo/Res123-2014-CD.pdf.

Ecuador

In 2015, the new Telecommunications Act of Ecuador (Ley Orgánica de Telecomunicaciones) included a clause specifically addressing network neutrality. The Act prohibits “limiting, blocking, interfering, throttling, prioritising or restricting the right of users to use, send, receive or offer any legal content, applications, development or service through the Internet or in their networks or other technologies of information and communications”. The Act also forbids limiting “the right of the user or subscriber to incorporate or use any class of instrument, dispositive or device on the network”, whenever legal, with the exception of cases established under the legal framework of Ecuador and those in which the competent authority decides, or when the client, subscriber or user expressly demands the limitation or blocking of content. Providers are allowed to carry technical actions to manage their networks, when considered necessary, and when within the exclusive scope of activities, they are authorised to perform to guarantee the provision of service.

Source: Ecuador (2015), Ley Orgánica de Telecomunicaciones, http://www.arcotel.gob.ec/wp-content/uploads/downloads/2015/03/ro_ley_organica_de_telecomunicaciones_ro_439_tercer_suplemento_del_18-02-2015.pdf.

IPv6

In mid-2014, the Latin American and Caribbean Network Information Centre (LACNIC), the organisation responsible for assigning Internet resources in the region, announced the exhaustion of its IPv4 address pool and expressed its concern regarding the pace of the deployment of Internet Protocol version 6 (IPv6) in the region (LACNIC, 2014). The IPv6 protocol was developed by the Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF) in 1996 as a response to the evident rapid growth of the Internet after its commercialisation in the 1990s. While hardware manufacturers, network vendors and the software development community have been ready for more than a decade, the deployment and rollout of IPv6 is still at an early stage in the LAC region, as elsewhere.

Following the announcement by LACNIC that its pool of available IPv4 addresses had reached the 4.1 million mark, stricter Internet resource assignment policies were implemented. In practice, this means that IPv4 addresses are now exhausted for Latin American and Caribbean operators. As agreed by the regional community, LACNIC’s pool of IPv4 addresses is considered officially exhausted and the Gradual Exhaustion and New Entrants policies have come into effect, introducing new procedures and requirements for those requesting resources. Two million of the remaining addresses may be assigned during this phase, in blocs of limited sizes. In addition, an organisation may only request additional resources six months after receiving a prior assignment. Once these 2 million IPv4 addresses are exhausted, LACNIC members will no longer be able to receive any IPv4 assignments. During this final phase, only new members will be able to request IPv4 addresses and only be able to receive one assignment from this space.

In 2008, OECD governments signed the Seoul Declaration on the Future of the Internet Economy, which specifically mentioned the transition to IPv6, declaring the need to “encourage the adoption of the new version of the Internet protocol (IPv6), in particular through its timely adoption by governments as well as large private-sector users of IPv4 addresses, in view of the ongoing IPv4 depletion” (OECD, 2008).

Governments can facilitate adoption through a number of policy measures and actions. The following measures have been recognised as having some positive effects on the deployment of IPv6:

-