Chapter 4. Policies to ensure Japan’s regional and rural revitalisation

This chapter is concerned with the revitalisation of Japan’s smaller cities and towns and its rural areas. It begins with a review of revitalisation policies in Japan and then presents a brief overview of economic conditions and trends in Japan’s intermediate and predominantly rural regions. It then presents the current package of revitalisation policies before turning to three key themes that emerge in discussions of regional and local revitalisation efforts. The first is the relationship between agricultural and rural development policies, which has been evolving in Japan in recent years. The second is the design of policies for geographically challenged regions, such as small islands and remote mountainous areas, of which Japan has many. The third concerns the policy framework for managing infrastructure, service delivery and economic development in places that are destined to lose much of their population over the longer term.

While Japan needs to make its large urban areas more dynamic and productive, it also needs to find better policies for unlocking the potential of smaller cities and rural areas. This chapter begins with an overview of the evolution of policies aimed at promoting the development of Japan’s non-metropolitan areas – rural areas, towns and smaller cities – and at their recent economic performance. The discussion then turns to the broad regional revitalisation strategy initiated by the government in 2014 before turning to specific policies concerned with SME promotion, entrepreneurship and innovation, rural development and policies supporting geographically disadvantaged regions. Finally, it explores policies for managing land use, service provision and economic development in towns and cities that are shrinking.

The evolution of Japanese revitalisation policies

The challenges facing non-metropolitan areas are not primarily about demography

The ongoing decline of many second-tier cities and rural areas in Japan is rooted not in demographic trends so much as in structural economic change. Indeed, Japan’s rural population began falling in about 1950, long before fertility dropped and the total population trajectory shifted towards decline.1 Many of its second-tier cities also began to lose population while it was still rising nationally. The principal factor at work was not low fertility or increasing longevity but the movement of labour out of rural activities, owing both to increasing productivity in agriculture and the shift in the structure of the entire economy towards industry and services, where agglomeration economies are particularly important and cities thus have an enormous advantage. Even second- or third-tier cities and rural towns have struggled in the face of such change. For a time, their lower costs and relatively abundant labour enabled some provincial towns and rural areas to benefit from industrial relocation, particularly of space- and labour-intensive industries. However, much of this activity moved offshore in the late 20th century, and the evolution of the Japanese economy towards more R&D- and capital-intensive activities simply reinforced the advantages of the big cities (Elis, 2011). Non-agricultural rural activities have also been hit hard, most notably in the decline of many mining towns and the struggles of smaller ports in the face of consolidation in that sector (Coulmas and Lützeler, 2011).

Japan’s complex geography has long exerted a powerful influence on the evolution of regional policies. Although a huge part of the population is concentrated around the three main cities, the rest is dispersed over a very wide area. The country comprises more than 6 800 islands, of which 316 are inhabited. All, apart from the 5 main islands,2 have fewer than 70 000 inhabitants, but they are spread over such a wide area that Japan’s exclusive economic zone covers 4 470 km2 – 12 times the country’s land area. Moreover, much of the country (and, in particular, of the main island of Honshū) consists of mountainous regions and complicated coast lines (35 000km in total). Altogether almost 70% of Japan is forested (comparable to the levels found in Nordic countries), much of that being quite mountainous as well; only 12% is cultivated, and roughly 8% is given over to roads, residential use and industry. As a result, the country is rich in terms of biodiversity, soil and water resources. However, infrastructure management, particularly for transport, is exceptionally complicated and costly, and many rural communities face unusually severe accessibility challenges. In addition, most of the country is vulnerable to natural disasters, most notably earthquakes, typhoons and tsunamis. Support for geographically disadvantaged regions has typically taken the form of infrastructure investments to improve connectivity, special conditions regarding tax sharing, support for some transport services (regular sea/air transport) and tax breaks for households and firms confronting specific local problems (e.g. for the construction of snow-resistant housing).

As urbanisation accelerated in the 1960s and 1970s, measures to support geographically disadvantaged regions were reinforced by special fiscal support for municipalities facing significant loss of population. These measures tended to focus on the rate of population decline. Not surprisingly, many of the beneficiary municipalities were also geographically disadvantaged. These early efforts relied to a great extent on the “traditional” instruments of regional policy used in other OECD countries: large infrastructure projects and tax breaks to encourage industrial location in particular places. These efforts only ever had a limited impact, and they were undercut from the 1970s onwards by a series of developments, including the oil shocks, which accelerated the structural shift towards high-value services (and thus towards Tokyo); globalisation, which has facilitated the transfer of manufacturing operations from Japan to overseas locations, a process that accelerated in the 1990s with the rise of the yen; and demographic shifts that made it harder for firms to recruit the labour they needed in many areas. Policy since the late 1990s/early 2000s has shifted again, towards reliance on innovation and cluster policies, though infrastructure policies remain important, as do tax breaks for, e.g. companies that relocate some headquarters functions to the regions (Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, 2014). These new approaches, particularly those concerned with innovation and entrepreneurship, are considered below.

Rural policy has changed considerably in recent years

For many years, rural development policy was almost coterminous with agricultural policy. Even as Japanese agricultural policy came to recognise the importance of multifunctionality, farming remained at the centre. Thus, the 1999 Food, Agriculture and Rural Areas Basic Act defined the stable supply of food and the preservation of multifunctionality as its key objectives.3 Sustainable agricultural production was seen as the means to achieve these two objectives, and rural hamlets were seen as important because they could support agricultural production by collective maintenance of land and water resources. This has lately begun to change, however, with the emergence of initiatives like the “sixth industry”, which is explored below. As will be seen, the challenge at present is to manage the trade-offs that sometimes emerge between facets of agricultural policy and rural development policy: in particular, this concerns the balance between the pursuit of higher productivity in farming and the desire to limit the depopulation of rural hamlets. More efficient rice farming might in many cases lead to an accelerated outflow of population. One of the major concerns of this chapter is how to manage these two objectives in tandem.

Regions and municipalities have also been increasingly active

As demographic pressures have mounted in recent decades, the local authorities themselves have tried an ever-wider range of strategies to combat population decline. Some of these have been purely local initiatives and others have been supported by the national or prefectural authorities. So far, nothing has stemmed the tide. The large cities have tremendous advantage in competing for younger people, in terms of the range of available job opportunities, educational opportunities and even “marriage markets”. The rise of two-income households tends to reinforce this advantage, because it is easier for both partners to find work in thicker labour markets. As a result, some places have competed to attract retirees instead, and not without success. However, the sustainability of some of the instruments employed is open to question: Elis (2011) notes that subsidies for real estate purchases can be substantial in some places, but it has become clear that cost escalation over time (as the newly arrived retirees grow older) is a problem. Other areas have pursued local policies to support fertility, including awards and even marriage brokerage offered by municipal governments.4 In some places, relocation subsidies, cheap housing and family-friendly services can indeed work, though this seems to be most promising in places close to a city offering employment and education opportunities.

The current push for regional revitalisation comes at a critical juncture

Japan has now experienced several decades of local and regional revitalisation initiatives. Such policies have been a recurrent priority of governments since the 1970s, in the form of policies aimed at industrial decentralisation, nodal development, relocation of the functions of the capital, decentralisation of corporate headquarters, “hometown revitalisation”, and the development of “regional core cities” and “wide community areas” (Sasaki, 2015). Even leading government ministers acknowledge that there is a need to explain how and why the current effort will be different;5 otherwise, there is a very real risk of cynicism about how much difference it will make. Some observers are already expressing concern about the failure of many subnational governments’ local revitalisation plans to engage critically with past policy failures, as well as inadequate assessments of local resources, capacities and demographic prospects (Nishimura, 2015).

Nevertheless, there are some reasons to think that this time can be different. First, the Masuda Report on the consequences of depopulation (Box 4.1), which appeared in 2014, has galvanised a large part of the political elite, particular those active in regional and local politics in places that are losing population. Secondly, public interest is also high. A Dentsu poll of 10 000 people conducted in April 2015 found that 80% were aware of the local revitalisation policy (though only about a third knew of its content) and three-quarters favoured steps to counterbalance the concentration of people and activity in Tokyo. Such awareness matters, because the “local revitalisation” initiative is predicated on developing a national popular movement: the aim is not to impose a central vision on the country from the top down but to use central leadership to mobilise bottom-up initiative in local communities (Kido, 2015). Thirdly, fiscal pressure is another factor setting the current effort apart from those of the late 20th century or even the early 2000s: local revitalisation is seen as central to generating growth and to longer-term prospects for putting Japan’s public finances in order. Finally, the current effort to build and sustain a whole-of-government approach to revitalisation is encouraging, in view of the often confusing multiplicity of objectives and mechanisms that have prevailed in the past. Sustaining this effort will be critical.

In the midst of Japan’s demographic transition, and in light of previous policies’ perceived inadequacies, the Japan Policy Council (JPC) in May 2014 published a study entitled “Stop Declining Birth Rates: The Local Revitalisation Strategy”, which sought to galvanise debate and policy making on the intersection between ageing and the economy. The report is often referred to as the “Masuda Report,” after JPC chairman Hiroya Masuda. The report attracted widespread public attention with its stark warning that 896 local governments – roughly half the total - risked “extinction” by 2040 through further declines in their populations of young women. It argues that the best response to regional decline would be a strategy of building “regional cities attractive to young people,” by forging a “new structure of agglomeration” and a “choose and focus” strategy of investment. The report emphasises the need to make these regional cities into the nodes of networks that function to “dam” the flow of younger people into the largest cities.

This approach is consistent with some recent government initiatives, particularly those of the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications (MIC), which Mr Masuda previously headed. The “autonomous settlement region,” which the MIC inaugurated in 2008, is anchored on “core” regional cities of at least 40 000 residents, building on transport, information and communication technologies (ICT) and other networks to link them with surrounding towns and villages and rationalise the region’s distribution of health, education, and other services. As of February 2015, there were 85 of these regions. The programme is financed with special incentive measures in the special “Local Allocation Tax” (LAT) (ordinarily used for emergencies). From fiscal year 2014, these incentives were increased to JPY 85 million for the core city and JPY 15 million for each area community (Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications, 2015).

The Masuda Report was presented to the Council on Economic and Fiscal Policy, the Industrial Competitiveness Council and other ranking policy-making organs. Its warnings and recommendations, and subsequent interventions by the JPC, have become important sources of inputs into, and showcases for discussion of, the revitalisation strategy. The report and the follow-up to it have been important in provoking discussion across Japan, as well as in focusing attention on the need to overcome sectoral policy approaches in favour of more integrated strategies for adapting to demographic decline.

Economic conditions and trends in performance

Japan’s rural regions are still relatively prosperous by OECD standards

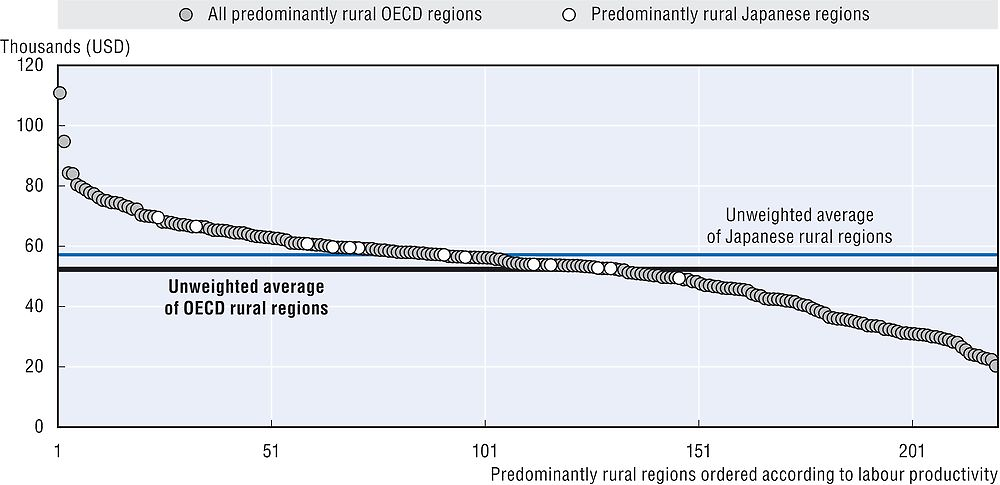

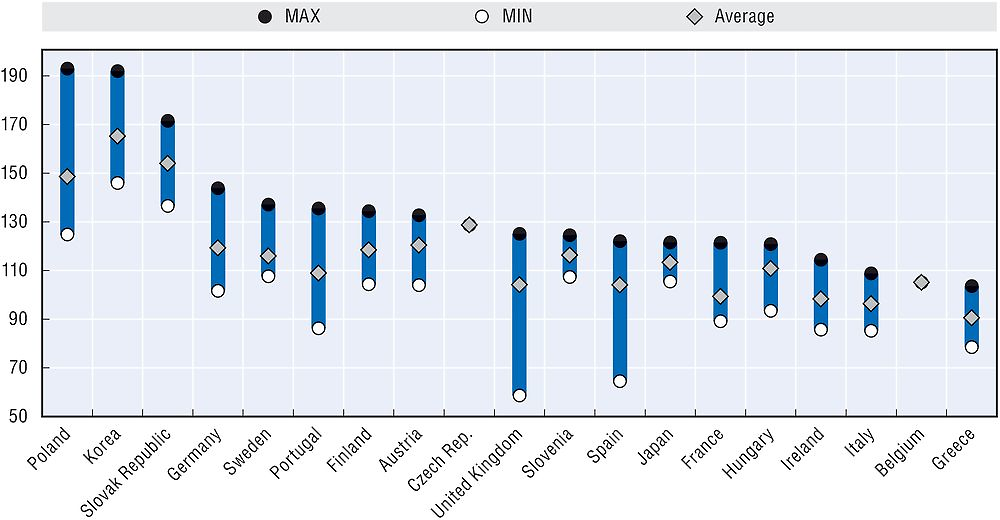

This chapter is devoted to the challenges facing Japan’s non-metropolitan regions, including smaller cities and towns, as well as rural areas. These are considerable. Nevertheless, it would be a mistake to focus on the problems to such an extent as to overlook some of the considerable strengths of such regions. Some of these have already been touched on in previous chapters, which have underscored the relatively low inter-regional disparities in general in Japan and, in particular, the fact that the income gap between predominantly rural (PR) and predominantly urban (PU) regions is among the lowest in the OECD. Rural regions in Japan also offer many advantages in terms of quality of life. This section reinforces that analysis by benchmarking predominantly rural Japanese regions against those of other OECD countries. While rural regions in Japan have tended to grow slowly – like all regions in Japan – they nevertheless exhibit certain strengths when seen in an OECD-wide context. In particular, GDP per capita in Japan’s predominantly rural regions was about 13.6% above the OECD average for such regions in 2012 (Figure 4.1), and only one Japanese PR prefecture was more than 10% below the OECD-wide average. Labour productivity in such prefectures was also about 10% above the OECD average in 2011 (Figure 4.2). This is particularly remarkable given that Japan’s economy-wide labour productivity is now below the OECD average (OECD, 2015a).

Source: OECD (2015b), Regional Statistics (database), https://doi.org/10.1787/region-data-en (accessed 10 September 2015).

Source: OECD (2015b), Regional Statistics (database), https://doi.org/10.1787/region-data-en (accessed 10 September 2015).

Growth has been weak but labour market performance has been relatively good

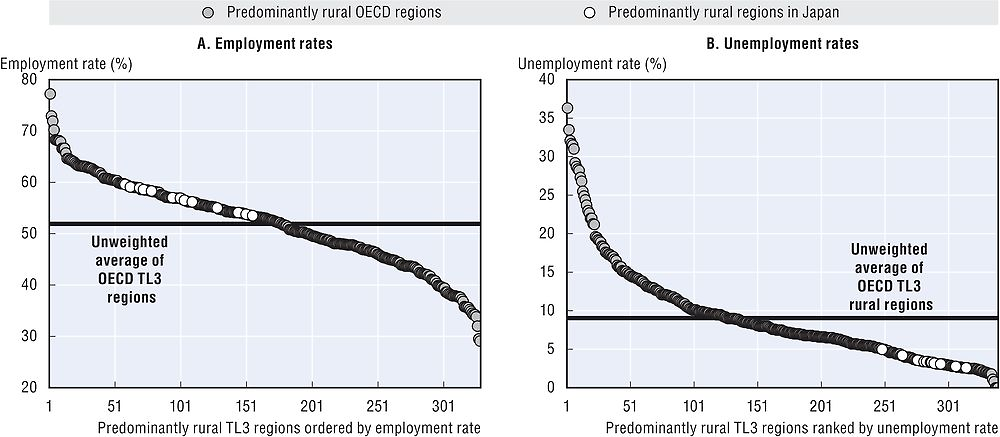

Not surprisingly in view of Japan’s national performance, the country’s PR regions have exhibited lacklustre growth performance in recent years. Even so, data for 2001-12 show the country’s rural areas very much in the middle of OECD rural regions when it comes to the growth of GDP per capita (Figure 4.3). As was seen in Chapter 1, of course, this owed much to population outflows rather than to strong aggregate growth performance. Those outflows have caused much concern, since many rural communities have been losing their most productive young people, but this smooth labour market adjustment has ensured that rural Japan does not experience the very high unemployment seen in many OECD rural regions. Indeed, as is clear from Figure 4.4, PR regions in Japan perform exceptionally well when it comes to labour market outcomes, especially unemployment. Labour force participation rates are above the average for PR regions in all but three of Japan’s PR prefectures. Employment rates are above, and unemployment rates below, the respective OECD averages in all of Japan’s predominantly rural regions.

Source: OECD (2015b), Regional Statistics (database), https://doi.org/10.1787/region-data-en (accessed 10 September 2015).

Source: OECD (2015b), Regional Statistics (database), https://doi.org/10.1787/region-data-en (accessed 10 September 2015).

Policies for regional revitalisation

A new scheme for National Strategic Special Zones is being put into place

A new scheme for “National Strategic Special Zones” (NSSZs) was launched in 2014 as part of the 2013 Japan Revitalisation Strategy (Box 4.2). Special zones have long been a prominent feature of Japanese regulatory reform efforts, most notably the Special Zones for Structural Reform (SZSRs) launched by the government in 2002; by the end of 2014, there were no fewer than 1 235 such zones. These created the opportunity to experiment and pilot reform ideas in specific places, and it was hoped that such experiments would be a way to circumvent bureaucratic resistance to reform. The SZSRs were created at the initiative of local governments. Although a number of reforms piloted in the zones were extended to the whole country and their impact on investment and employment creation appears to have been positive, they achieved only limited success. This was in large measure because many of the proposals ran into entrenched opposition, not least from some central ministries (OECD, 2015c). In 2011, seven “Comprehensive Global Strategic Special Zones” were created to improve the business environment in cities, while a number of “Comprehensive Special Local Revitalisation Zones” were created for agriculture, tourism and culture. They provided for tax, fiscal and financial support as well as regulatory exceptions. By September 2013, 41 such zones for local revitalisation had been designated.

In March 2014, the government approved the creation of six National Strategic Special Zones. Considerable effort has been made to ensure strong national and local backing for them. A national-level Council on National Strategic Special Zones is chaired by the Prime Minister and includes the Minister of State for National Strategic Special Zones, other relevant ministers and private-sector experts. Each Special Zone has a headquarters, bringing together the Minister of State for National Strategic Special Zones, the mayor and local business leaders. The headquarters collects regulatory reform ideas from the private sector, which are then examined by the central government’s Council. The reforms can be extended nationwide. Once the reforms are agreed, the local headquarters is responsible for implementation. The six zones designated in March 2014 include major urban areas:

-

Tokyo area: centre for international business and innovation

-

Kansai area (Osaka, Kyoto and Hyōgo prefectures): hub for medical innovation and human resources

-

Okinawa prefecture: international tourism centre

-

Fukuoka City: promotion of start-up businesses through employment reforms

-

Yabu City, Hyōgo Prefecture: reform centre for agriculture in mountainous regions

-

Niigata City: reform centre for large-scale agriculture

The National Strategic Special Zones’ main objectives are: i) formation of international centres with the “best environment in the world”; ii) creation of international innovation in healthcare; and iii) the formation of action centres for agriculture. These objectives are to be achieved through regulatory reforms in urban development, education, employment, medical care and agriculture. The zones are intended to spark private-sector investment.

Source: OECD (2015c), OECD Economic Surveys: Japan 2015, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/eco_surveys-jpn-2015-en.

The new zones differ from them in several important respects.

-

The central government is playing a much stronger role in the definition and creation of the NSSZs, as well as in running them. Local political and business leaders are also deeply involved, so the approach is based on a search for social consensus rather than on top-down decision making.

-

The NSSZs provide for the possibility of tax breaks and subsidies.

-

The NSSZs are meant to be fewer but more significant; under the 2002 scheme, some 5 725 proposals for zones were put forward and 1 235 SZSRs were created. This time, there are just six, four for major urban areas and two focused on agriculture and rural regions.

The zones’ success will depend on the ability of the new structures, which bring together national government, local governments and business leaders, to advance and implement bold reforms. Although there is broad consensus on the need for deregulation, resistance to specific reform measures is often very strong. In the Fukuoka zone, for example, an attempt to relax employment protection for regular workers in venture businesses less than five years old was blocked (OECD, 2015c).

SME policies need to make the sector more dynamic and more internationally integrated

As noted in Chapter 1, Japan’s small and medium enterprise (SME) sector is very large and constitutes the backbone of many local economies. However, it is not particularly dynamic. OECD (2015c) reports that government support constitutes 10% of SME financing – 20%, if guarantees are included. This helps keep many low-productivity SMEs afloat – so-called “zombie firms”, which would probably fail if they were forced to rely on market-based financing (Solomon, 2014). Indeed, bankruptcy rates in Japan have fallen steadily for a decade, at a time when, owing to the crisis, they have tended to rise in most countries (Solomon, 2014; OECD, 2015c). It is important to recognise that the problem with firm turnover identified in Chapter 1 is linked to efficient exit as well as easy entry: continued public support for inefficient SMEs is an impediment to entry as well as exit, since it distorts competition in favour of incumbents and allows weak enterprises to soak up investment and other resources that might have been more efficiently deployed elsewhere. Given Japan’s productivity challenge, as well as its fiscal problems, it is essential to focus (limited) support on start-ups and to push SMEs towards more market-based financing. Government financing support should be limited to financing gaps that arise as a result of identifiable market failures and the cost of support (especially loan guarantees) should be sufficient to discourage heavy reliance on this source of finance.

This does not mean that there is no room for effective SME policies in Japan’s revitalisation. On the contrary, there are a number of steps that can be taken to help SMEs adapt and grow even while putting them under pressure to become more competitive. One way would be to build on the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry’s (METI) promising one-stop support initiative for SMEs to create a sort of “SME extension service”, comparable to the agricultural extension services that exist in many OECD countries. Agricultural extension is the function of providing need- and demand-based knowledge in agronomic techniques and skills to rural communities in a systematic, participatory manner; it helps farmers access scientific research and to apply that new knowledge to agricultural practices. Something similar could be done for SMEs (and start-ups) in respect of, for example, innovation and internationalisation. METI is already active in these areas, but it could help to bring as many such functions together under the aegis of the one-stop shops, which could in turn serve also as local platforms for collaboration among firms.

Internationalisation should be central to these efforts. METI’s 2011-13 Framework for Supporting SMEs in Overseas Business exceeded its targets and demonstrated the potential demand for such support, but more systematic efforts could be undertaken by national and subnational authorities to help SMEs overcome the barriers to integration in global value chains. While the indicators of low SME internationalisation in Japan are partly the result of their close links to large companies and the prevalence of indirect trading through general trading houses (shosha), METI research points to Japanese SMEs’ lack of experience, human resources, marketing and other know-how necessary for internationalisation (EJCIC, 2012). These are the same kind of obstacles facing SMEs in many countries (Wilson, 2007; OECD, 2009a). METI is active in these areas, but regional and local actors can also help their SME populations with these issues, particularly by organising the collection and dissemination of information and regional/local marketing efforts. On the basis of a comparative study of SME experiences in the Asia-Pacific region, APEC (2014) emphasises, among other things, the promotion of supply-chain finance and financial skills training, support for collaboration and clustering of SMEs, and assistance with standardisation and certification procedures (and, where possible, cross-border harmonisation of the same). Wilson (2007) underscores the importance of governments acting, at home or in international negotiations, to reduce the administrative burden of cross-border activities, the quality of advisory services and steps to encourage local networks to integrate into larger regional, national and international ones.

The potential pay-offs to such efforts are significant. METI analyses show a clear and positive correlation between SMEs’ outward foreign direct investment (FDI) and their rates of employment growth (EJCIC, 2012). Despite the fear that outward FDI might involve “outsourcing Japanese jobs”, it seems to be the case that such firms retain core functions in Japan even as they enhance their competitiveness by internationalising.

A range of programmes now exist to support innovation in Japanese regions

The OECD defines innovation as “the implementation of a new or significantly improved product (good or service) or process, a new marketing method, or a new organisational method in business practices, workplace organisation or external relations” (OECD, 2011a). It thus encompasses a wide range of activities in addition to science-intensive research and development (R&D), including changes to production processes, management and organisation, training, testing, marketing and design. It is a social, institutional and geographical phenomenon, not just a technological or sectoral one. While science-intensive innovation tends to be concentrated in the largest cities, other forms of innovation can be, and often are, far more widespread. Moreover, there are opportunities for less populous areas to participate in high-tech innovation processes: Orlando and Verba (2005) find that incremental innovations associated with mature technologies are easier to anticipate than innovations in newly emerging technologies. This means that firms and investors involved in developing relatively mature technologies can plan in advance to locate in less populous, less costly places. Patent data tend to support this view. The implication is that policies that mitigate distance from thick markets and sources of knowledge spillovers can make less populous places more appealing to such innovators.

Japan’s regional innovation policies have long been characterised by cluster initiatives. There are various programmes to support industrial and knowledge clusters, depending on focused sectors and supporting ministries. The Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT) also promotes large-scale research collaboration among universities and companies for innovation, which could contribute to competitiveness of regions (Box 4.3). In addition, the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry (METI) has extensive programmes to revitalise SMEs through innovations. Although the initiatives by different ministries are gradually being integrated and co-ordinated, they remain rather fragmented and complex. For example, the Tokai region (Gifu, Shizuoka, Aichi and Mie prefectures), internationally renowned for its manufacturing (monozukuri) industry, has been supported by one knowledge cluster initiative, two industrial cluster projects and four regional innovation strategy support programmes. Most of these cluster projects are technology-oriented and organised by industrial sector (nanotechnology, life photonics, energy, etc.).

Japan’s regional innovation polices have been driven mainly by two ministries: the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry (METI) and Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT).

METI’s Industrial Cluster Programme, started in 2001, aimed to enhance the competitiveness of Japan through industrial clusters formed by local small- and medium-sized companies and venture businesses utilising “business seeds” developed by universities and other research institutions. By 2009, the METI promoted 18 projects nationwide based on the Industrial Cluster Plan starting from fiscal year 2001 through close partnership between METI’s regional Bureaus and about 10 200 regional SMEs taking on the challenge of new businesses and researchers etc. and more than 560 universities in total. Each cluster tried fostering network formation while also developing specific businesses. METI has allocated JPY 16.6 billion as the budget related to these activities in FY 2009. METI estimated more than 70 000 new businesses were launched under the Programme between FY 2001-07. After METI’s direct support ended in 2009, each project maintains and develops their network and activities by themselves. Since 2014, METI’s cluster support has been focused on smaller projects led by highly motivated private companies. Project managers are appointed to help the clusters, mainly with distribution channels: the idea is to link local actors, who are familiar with local assets, to outsiders who can help them tap wider markets.

MEXT’s Knowledge Cluster Initiative, started in FY 2002, aimed to create accumulation of knowledge for internationally competitive technological innovation by collaborative research among research organisations, R&D-oriented companies, and universities as a centre of knowledge. MEXT is supporting 15 regional clusters nationwide, among which 11 are global (to create regional innovations that are internationally competitive) and 4 are local (to create regional innovations that may be small in scale but maximize local characteristics). MEXT’s budget for FY 2009 was JPY 8.7 billion. The clusters produced more than 8 000 academic papers and 2 500 patent applications between 2002 and 2008 (Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, 2009).

In FY 2011, the MEXT, in collaboration with the METI and the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries (MAFF), introduced the Regional Innovation Strategy Support Program. The MEXT, METI and MAFF jointly selected 24 regions (9 regions for strengthening international competitiveness and 15 regions for advancement of research function and industrial concentration). The three ministries provide co-ordinated support to these regions.

Besides, the International Science Innovation Hub Development Project provides support for the construction of research facilities. In FY 2012, the MEXT selected 15 projects nationwide. Since 2006, the MEXT also started the Program of Innovation Centre Creation for Advanced Interdisciplinary Research Areas. This programme supports large-scale joint research among universities and companies which can lead creation of new growth industry. Twelve projects are selected.

Source: Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry (2009), 2009 Industrial Cluster Policy Brochure, available at: www.meti.go.jp/policy/local_economy/tiikiinnovation/source/2009Cluster(E).pdf; Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (2012), Brochure on Regional Innovation Strategy Support Program 2012, www.mext.go.jp/english/science_technology/1324629.htm (accessed on 6 August 2015); Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (2009), Brochure on Knowledge Cluster Initiative, 2009 edition, www.mext.go.jp/a_menu/kagaku/chiiki/cluster/1288448.htm (accessed on 7 August 2015).

From the competitiveness point of view, regions and cities need to think about how to link these different activities and stimulate cross-sectoral interaction, which could lead further innovation, and how to diffuse the results of innovation to a large number of companies and residents. The problem with a purely sectoral approach is that many of the most important innovations occur between sectors – e.g. the emergence of handheld devices for telephony, Internet use and even the viewing of film and television. Strengthening connectivity will play a crucial role (in metropolitan Japan, this will be an important function of the Chūō Shinkansen, as seen in Chapter 3). For Japan, however, policies to promote networking of individuals and institutions in a global setting could be more urgent. Both METI’s Industrial Cluster Programme and MEXT’s Knowledge Cluster Initiative promoted exchanges and tie-ups with overseas clusters to some extent (Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry, 2009; Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, 2009), although few joint innovation actions were found. Networked innovation can also open a new window for smaller cities and regions without full capacity to enter large-scale, international projects led by other cities and regions. Multinational enterprises and universities have a critical role to play as knowledge conduits for local SMEs. In order to support inter-urban networks, government financial support could prioritise joint projects undertaken by individuals and institutions located in at least two different cities/regions.

Since FY 2011, MEXT, METI and MAFF have selected regions that have proactive and prominent initiatives formulated through collaboration among local governments, firms and research institutions, and financial institutions as “regional innovation strategy promotion areas” and have built a system to offer support for continuous development from the research phase to commercialisation. As of FY 2014, there were 40 regions so designated, including 15 “regions for the enhancement of international competitiveness” and 21 “regions for the enhancement of research functions and industrial clusters”. The former are reckoned to have the basis for world-leading technologies and the potential to attract people and resources from overseas, while the latter have been selected for their potential to secure overseas markets in the future. The remaining four regions were selected to receive assistance in connection with reconstruction following the Great East Japan Earthquake.

Innovation and entrepreneurship must go hand in hand

Entrepreneurship has been recognised as one of the main engines of economic and social development. It is also critical to any innovation promotion effort, especially in non-metropolitan areas, where innovation is less likely to occur in large, established companies. New ideas and technologies do not create jobs or value added; entrepreneurs do. Innovative ideas, products and processes need entrepreneurs to bring them to market. According to a US National Commission on Entrepreneurship report (NCOE, 2001), innovation is the most important contribution of entrepreneurship at the local level. Together, entrepreneurship and innovation can generate economic growth and new wealth for a locality; and ultimately they improve quality of life for local residents (NCOE, 2001). Innovative entrepreneurship can have many local spillover benefits for existing local businesses (Acs and Audretsch, 1988; Acs and Varga, 2004; Drucker, 1984, 1985; Pavitt et al., 1987). In the second half of the 20th century, small entrepreneurs in the United States were responsible for 67% of inventions and 95% of radical innovations (Timmons, 1998). They have fuelled job creation and economic growth.

For innovation and entrepreneurship to flourish, the costs of failure must be reduced

The problem for Japan is that, as seen in Chapter 1, its entrepreneurship performance looks comparatively weak by international standards. Entrepreneurship is not widely seen as an attractive or respected option (see the survey data in OECD, 2013), and entrepreneurial failure tends to be very costly, not least because entrepreneurs and small-business owners often have little choice but to guarantee company debt, borrowing against their homes and other personal assets. Business failure often means personal bankruptcy and loss of one’s home (Solomon, 2014). This a particularly strong deterrent to older people considering entrepreneurship. Some go so far as to argue that the social stigma and financial repercussion of failure are so great that the founders of failed businesses become social outcasts, a risk few Japanese wish to take; those with reasonably good employment prospects, in particular, will be less likely to consider entrepreneurship, an activity that may thus – by default – be left largely to those whose chances are poorer (Wadhwa, 2010; Makinen, 2015). In a 2012 survey, the share of Japanese who thought that failed entrepreneurs should have a second chance was the second lowest in the OECD area (OECD, 2013). Not surprisingly, the employment prospects of failed entrepreneurs in Japan do appear to be poor, as are their chances of securing the funding needed to try again. This is a particular problem, because in other countries successful entrepreneurs often succeed only at the second or third attempt – after they have learned from failure. If failed entrepreneurs are less likely to enter the field again, then more entrepreneurs will be first-timers, making first-time mistakes.6 Little learning will occur. This contrasts with the experience of places like Silicon Valley, where the motto of “fail fast, fail cheap, and move on” is often quoted (Lee et al., 2011).

This is something the government is determined to address, having set explicit targets for increasing new start-ups over the coming years. To some extent, this may entail a degree of cultural change, which may not be easy or quick. Numerous observers, including Prime Minister Shinzō Abe (Nash, 2015), suggest that Japanese society is relatively risk-averse (Tabuchi, 2012; Kopp, 2012), and some survey data do indeed point to this conclusion (Iwamoto et al., 2012). Cultural change is often a slow and difficult process, but it can occur and policy can help to promote it. As Lindbeck (1995) and others have shown, cultural norms and habits do not exist in a socio-economic vacuum: they are themselves shaped by rules, institutions and incentives.

Here there are some steps that Japan can take to stimulate entrepreneurship, in particular by making entrepreneurial failure cheaper. The bankruptcy reforms of the last decade have already had a palpable positive effect in encouraging entrepreneurship among young, high-skilled Japanese (Eberhardt, Eisenhardt and Eesley, 2014), and further reforms are planned. The Civil Code is to be revised so that SME managers and entrepreneurs can in part be released from personal guarantees on corporate debt in certain (still to be specified) circumstances. Since these amendments will take time to prepare, the government has already asked banks to allow personal debt forgiveness to managers of bankrupt firms under certain conditions (Solomon, 2014).7 As noted in Chapter 1, the Revitalisation Strategy also includes steps to promote venture capital, and METI’s start-up support programmes now include loans and guarantees that are unsecured, with no need for guarantees and even the possibility of funding for second-attempt start-ups. Interest rates are slightly lower for women, youth and seniors (Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry, 2013). Entrepreneurship education is also taking root, with support from the government, but most programmes are still quite small. Regional and local authorities could do much here, expanding such programmes and designing curricula to reflect local conditions. Local communities, especially in rural areas, can also do much to increase social recognition of entrepreneurs and of the contributions their business ventures make to local revitalisation (OECD, 2011a).

Some rural areas are well-placed to attract entrepreneurs in knowledge-intensive services

As noted above, the shift towards an economy dominated by services initially reinforced the advantages of the big cities at the expense of non-metropolitan areas. However, this may be changing to some extent as a result of the growth of the information economy. Rural areas with attractive landscapes and amenities – and especially those that combine these attributes with good external connectivity – could make themselves into attractive locations for start-ups in knowledge-intensive service activities (KISA). A relatively new trend in entrepreneurship mixes knowledge-based competitiveness and services; it has been growing rapidly in amenity-rich rural areas of many parts of OECD countries since the turn of the century. OECD (2007) has published a list of KISA industries based on their International Standard Industrial Classification (ISIC). According to recent research (OECD, 2006; Martinez-Fernandez, 2010; Lafuente, Vaillant and Serarols, 2010; Vaillant, Lafuente and Serarols, 2011), KISA firms are both sources and carriers of knowledge that influences and improves the performance of clusters across all sectors of the economy. KISA firms cover management and business consulting, ICT, professional, health and legal services, together with insurance and financial services.

Although KISA firms have long been more common in large metropolitan areas, some rural regions have seen rapid growth in KISA, largely as a result of “amenity migration” (Vaillant, Lafuente and Serarols, 2011). Entrepreneurs and staff of KISA firms are often attracted to amenity-rich rural areas that are easily accessible to major urban areas. It is worth highlighting that, in contrast to technology-based manufacturing, KISA firms have tended to spread much more widely across rural territory. In Spain the autonomous region of Catalonia led the way in the growth of rural KISA firms, with up to 10% of new KISA firms created between 2003 and 2006 established in rural areas (Lafuente, Vaillant and Serarols, 2010). And while rural areas usually lag far behind their urban counterparts in knowledge-based firm creation (Roper and Love, 2006), the proportion of rural KISA firms in this amenity-rich region of Spain increased faster than in urban areas during the early 2000s (OECD, 2009b). The increased entrepreneurial activity of rural Catalonia has been accompanied by rising economic prosperity, with most parts of rural Catalonia benefiting from above-average economic growth (Lafuente, Vaillant and Rialp, 2007). In Japan, this sort of dynamic underlies the emergence of a small but growing IT cluster in the small town of Kamiyama (Box 4.4)

Kamiyama, a rural community in Tokushima Prefecture on the island of Shikoku that set out to attract IT start-ups several years ago. The programme was launched by Green Valley, a non-profit private group, and was designed to revitalise the town by offering abandoned houses to IT engineers and other workers as satellite offices. The project is small but it has attracted 10 IT ventures to this town of 6 100 since 2010 years. Underlying Kamiyama’s bucolic appeal is an advanced IT infrastructure built with the help of the prefectural government’s drive to extend broadband access to its entire territory. Fibre optic cables have been installed in each house and the monthly fee is low (JPY 2 625 in 2013) Data speed in Kamiyama is about 5-10 times faster than Tokyo, because there is so much less traffic. Significantly, Kamiyama also refrained from offering fiscal “sweeteners”, which might prove expensive and unsustainable over the long term, fearing that tech entrepreneurs who came in search of such perks might leave when they ran out: in contrast to old industrial investors building large factories, tech firms’ rely mainly on (highly mobile) human capital. While the long-term future of this venture and others like it is not assured, Kamiyama has made a promising start. The tech cluster has attracted international attention, but it is also significant that Green Valley’s revitalisation strategy goes beyond attracting IT firms: its efforts to attract and retain highly skilled workers by offering a good quality of life also extend to the promotion of cultural activities and exchanges, including an artist-in-residence programme.

An important part of Kamiyama’s focus is on changing the structure of the population: revitalisation may slow the decline of Kamiyama’s population or even reverse it. In 2011, the population, which had fallen from 21 000 in 1955 to just about 6 000 in 2010, rose – albeit by only twelve people. However, given national population trends it would be premature to bet on a change in trend and, in any case, that is not the focus. Green Valley’s founders emphasise the quality of the population, not its size. The key to future prosperity lies in attracting young and skilled people, so that even a smaller Kamiyama can offer opportunities and a good quality of life to its residents.

Sources: Tomoe, A. (2014), “Aging Kamiyama Hopes to Rejuvenate with IT Startups”, The Japan Times, January 1; Fifield, A. (2015), “With Rural Japan Shrinking and Aging, A Small Town Seeks to Stem the Trend”, Washington Post, 26 May; Green Valley Inc. (n.d.), “In Kamiyama”, http://www.in-kamiyama.jp/en/about-us/ (accessed 14 December 2015).

Although KISA firms are not intensive creators of employment, they generate economic spillovers for the (often low-density) communities in which they are located. Many KISA firms are one-person firms constituted by self-employed professionals. Apart from the fiscal benefits generated by the presence of KISA firms, they help retain wealth locally, as local firms and individuals use their services; and they create new wealth by generating revenues that complement existing services. Moreover, not only are KISA firms attracted to amenity-rich areas, they add to these amenities through the local supply of their services, as in the case of the Sunshine Coast (Box 4.5).

KISA firms have multiplied around an amenity-rich rural region in the Sunshine Coast of British Columbia, Canada. In this area endowed with exceptional natural amenities, several hundred businesses exporting services around the world have been created. These include engineering, architecture, marketing, publishing, design, information technology, wellness and counselling, financial management and more. Through networking and the establishment of a virtual cluster tying all these KISA firms together (Sunshine Coast Intelligence Services Cluster Network, www.coastisc.net/) the authorities have not only ended many rural KISA entrepreneurs’ sense of isolation but have also helped establish social and professional connections. This has given rise to a virtual local market with many KISAs using each other’s services. There are several examples of different KISA firms in the region that have combined their services to increase business reach and competitiveness. The availability of system amenities further increases the attractiveness of the area for new KISA firms. The Sunshine Coast is quickly gaining recognition not only for the exceptional amenities it offers residents but also for those it offers its growing community of KISA firms and entrepreneurs.

Source: OECD (2012a), OECD Territorial Reviews: Småland-Blekinge, Sweden 2012, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264169517-en.

The promotion of new entrepreneurial activity must be conducted in parallel with the attraction and retention of talents. Because of the current lack of adequately skilled labour for these enterprises in many regions, encouraging an overly rapid increase in new knowledge-based start-ups, with its consequent requirements in terms of qualified labour, may simply lead these ventures to leave. New firms must be able to inject new ideas and innovations into the local industrial fabric so as to create a positive contagion effect and lead existing business owners to also adopt more modern business methods, albeit at a pace that a region’s labour market can sustain. Many local economies also need a greater diversity of consumer services to increase their attractiveness to entrepreneurs and highly skilled workers. New ventures in proximity services – everything from hair-dressing to restaurants – should therefore be valued, both because they provide much needed private proximity services and amenities, and because they help to integrate and optimise the economic contribution of segments of the population that may not otherwise find their place in the local economy.

The experience and skills of older people are an entrepreneurial resource

As noted in Chapter 1, encouraging entrepreneurship among older Japanese is an increasingly important priority. While much of the literature suggests that older people are less likely to take entrepreneurial risk, it also finds that older entrepreneurs are more likely to be successful, not least because they have more developed networks, more experience and, in many cases higher skills and more financial resources.8 Moreover, it appears that the propensity of older people to start businesses – whether simply to be self-employed or to build a job-creating business – is rising over time. The evidence also points to the degree to which relatively simple policy interventions can stimulate entrepreneurship among older people. Box 4.6 gives a summary of the main messages emerging from joint European Commission-OECD work on the issue. While some things, such as the tax and social security implications, are central government competences, many of the others are relatively low-cost actions that Japanese regions and towns may want to consider.

To increase entrepreneurship by older people, policy should:

-

Create a positive awareness of the benefits of entrepreneurship for older people among older people themselves, and in society in general.

-

Assist business start-ups by older people by supporting relevant business networks for older entrepreneurs and providing training to fill knowledge gaps on entrepreneurship skills for those who have spent their working life as employees.

-

Ensure that older entrepreneurs have access to financing schemes, recognizing that some groups of older entrepreneurs (e.g. those starting a business while unemployed) may need start-up financing while others (e.g. those with high incomes) may not.

-

Highlight the possibility of acquisition, rather than start-up of a business, as a means into entrepreneurship for an older person as it may be quicker, less risky and can facilitate another person retiring who may wish to do so.

-

Encourage older people to play a role in promoting entrepreneurship by others by becoming business angels or by mentoring younger entrepreneurs.

-

Ensure that tax and social security systems do not contain disincentives to entrepreneurship for older people, including investment in other businesses.

-

Reduce the likelihood that a failed venture will leave the entrepreneur destitute – the risk of losing home, life insurance and other savings is particularly serious towards the end of one’s career.

Source: OECD/European Commission (2012), “Policy Brief on Senior Entrepreneurship: Entrepreneurial Activities in Europe”, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg, available at: http://www.oecd.org/cfe/leed/EUEMP12A1201_Brochure_Entrepreneurial_Activities_EN_v7.0_accessible.pdf.

Online networking platforms are relatively simple to create and can be helpful for propagating a range of tools for would-be entrepreneurs. For example, the “Best Agers” and “female” schemes operating in a number of European countries use such platforms to organise training events, webinars, mentoring circles and other events (Kautonen, 2013). In the United Kingdom, the PRIME (Prince’s Initiative for Mature Enterprise) initiative offers information, training, workshops and networking events for older entrepreneurs; in addition, it provides free or low-cost business advice, either through referral to accredited advisors or volunteer mentors (Kautonen, Down and South, 2008). It has also provided micro-finance in the past. There may also be a need for help with access to finance: though many senior entrepreneurs are in a stronger financial position than their younger counterparts, EMN (2012) finds that age discrimination is very often a real problem when they do need access to credit. In some cases, they may be asked to take out additional insurance to cover the risk. At best, that implies additional costs, but very often it is even more of an obstacle: insurance companies can be as reluctant to cover older entrepreneurs as banks are to lend to them. Yet few public programmes to assist entrepreneurs with access to finance are adapted to the needs of older workers.

Seniors may also play a role in promoting entrepreneurship without going into business themselves. One should not overlook the entrepreneurial potential of older workers, particularly retired managers and executives, as a resource for younger entrepreneurs. This is particularly true with respect to the large cadre of retired or soon-to-be retired managers of SMEs. Individuals who know how to run small and medium businesses, particularly small- and medium-sized manufacturing businesses, must be seen as a rare and valuable resource for a region or locality. Research suggests that the hardest phase of development for new firms and sectors to finance is not start-up but the long – and usually loss-making – period of “learning-by-doing”, when the new entrepreneurs are ironing out the “bugs” in their processes (OECD, 2011b). The difference between survival and exit can hinge not on the overall character of the product or the nature of the production technology but on relatively small differences in quality control, the management of order flow and stock control, etc. A reduction of 1-2 percentage points in the share of defective products or a reduction of just a few hours in order turn-around times can be decisive. The shorter this learning-by-doing process is, the greater the firm’s survival chances. Experienced managers can help here, and many regions might consider organising programmes to match local businessmen with entrepreneurs, whether on a voluntary basis or as paid consultants.

Business successions present a challenge and an opportunity

While the growing propensity of older Japanese to express an aspiration to become entrepreneurs or self-employed is to be welcomed, the other reality that the MIC’s recent employment status surveys underscore is the ageing of the population of active entrepreneurs. In 1979, just 18.9% of Japan’s active entrepreneurs were above the age of 50 and only 6.6% above 60. Those shares grew steadily, decade by decade, apart from a brief decline in the late 1980s/early 1990s, and by 2012 fully 46.7% of active entrepreneurs were over 50 and almost one-third (32.4%) were over 60. This is more than just a consequence of population ageing – the older cohorts’ share of the active population rose from 25.2% to 38.6% over the same period. This matters, because it means that the future of a steadily growing share of Japanese SMEs is in question as their founder-owners approach retirement.

In many OECD regions, low birth rates combined with high numbers of business owners approaching retirement age mean that, over the next decade or two, there may be unparalleled shortfalls of business owners, with potential negative effects on local economies (OECD, 2011b). Succession issues have become one of the main concerns of business development officials in many OECD countries. In North American rural communities, for example, the baby-boom generation of entrepreneurs and business owners is retiring but there is a lack of rural youth available and willing to take up those businesses. In such places, many family businesses are run by the older generation, while the younger generation increasingly tends to migrate to bigger cities and often has little interest in continuing the family business. Many businesses stand to close, not because of financial problems but because there is no one to take over once the owner retires. A recent assessment by the Canadian community development programme, Canada Futures, found that the family ensures only a small minority of successions in non-metropolitan areas. For businesses that did not have a family member willing to take over the business, two-thirds had not developed a succession plan and over 80% of older owners planned to sell their businesses but were unable to find buyers. As a result, some 30.6% of retiring business owners decided to close their businesses (Camire, 2011).

This represents a challenge, but it is also an opportunity – an opportunity to attract new, younger talent to a region or locality. It is also a chance to infuse firms with new dynamism: the 2015 SME White Paper reports that the performance of SMEs in which founders handed over control to younger successors improved. However, smooth business successions must be planned well in advance. To avoid unnecessary closures, local business facilitators can help older entrepreneurs to develop succession plans. Experience elsewhere suggests that most businesses are far from being “sale-ready” when the time comes for the current owner to retire. When a family member does not take over, great care must be taken to make the business as attractive as possible to a prospective buyer. Business owners need to prepare and value their businesses. They have to review and upgrade their firms’ processes to optimise their attractiveness, and they often need assistance with this process.

METI’s SME Agency and the Japan Finance Corporation are both active in this area, with programmes to support smooth successions, including the transmission of skills and techniques, and assistance with financing. However, more can be done. Local business development officers can help connect buyers and sellers, providing information about businesses that are for sale to potential young entrepreneurs in the community, as well as to inbound investors and migrants who may be looking for an opportunity in the area. In fact, an inventory of potential business succession opportunities (possibly web-based) could help bring to a community people who might be attracted by the lifestyle and amenities it has to offer. It could also be a way to offer opportunities for women and older workers who wish to become entrepreneurs or alternative business strategies for locals who already work as self-employed entrepreneurs. The important thing is to help connect buyers and sellers (Clark, 2011). Local financial institutions need to be receptive to financing business transition opportunities within the community. Support in the form of leverage loans is often needed to ensure a smooth transition to the new owners. One valuable benefit to the buyer is the potential for local mentorship from the previous owner, often within the same community. Business facilitators should help ensure that, where possible, this option remains a part of any succession plan.

Agricultural policies and rural development

At national level, the broad outlines of rural development policies are defined in two basic documents: the Headquarters’ Comprehensive Strategy for Regional Revitalisation and MAFF’s Basic Plan for Food Agriculture and Rural Areas, a medium-term policy document that is renewed every five years. The current plan was adopted in March 2015. It, in turn, reflects the approval in December 2013 of a “Grand Design” for agriculture called the “Plan for Creating Agriculture, Forestry, Fishery and Regional Revitalisation” under the Headquarters for Agriculture, Forestry, Fishery and Regional Revitalisation, which is chaired by the Prime Minister with the Cabinet Secretary and the Minister of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries as vice-chairs. It presents agriculture, forestry and fisheries policies, on the one hand, and regional policies on the other as the two wheels of a cart. The aim is to balance the two and to realise complementarities between them, largely via the measures to enhance the multifunctionality of agriculture, forestry and fisheries.

Thousands of rural hamlets face the risk of depopulation

One of the primary concerns of Japanese policy makers confronting depopulation is the fate of the country’s small hamlets, which are disappearing at an alarming rate. At present, there are around 130 000 agricultural hamlets9 in Japan; on average, they have around 30 ha of farmland, two-thirds of which consists of rice paddies, the rest being used for other crops. In 2010, there were about 198 households per hamlet, a figure that was up almost 2.5-fold since 1970 but some 7% down over the previous decade. However, median hamlet size rose from 48 to 50 households over the period, suggesting that the average has been hugely influenced by hamlets in proximity to cities, where the number of non-farming households rose very rapidly.10 However, only about 9-10% of households were actually engaged in agriculture; most live from non-farm income sources. Depopulation and ageing both are more advanced in rural hamlets and proceeding faster than in other areas of Japan, thanks largely to the emigration of young people to the cities, which reflects both the employment and consumption opportunities that cities offer and the drastic decrease in labour required for agriculture. A number of observers have expressed great concern about the prospect of tens of thousands of these hamlets simply disappearing (see e.g. Odagiri, 2012, 2015).

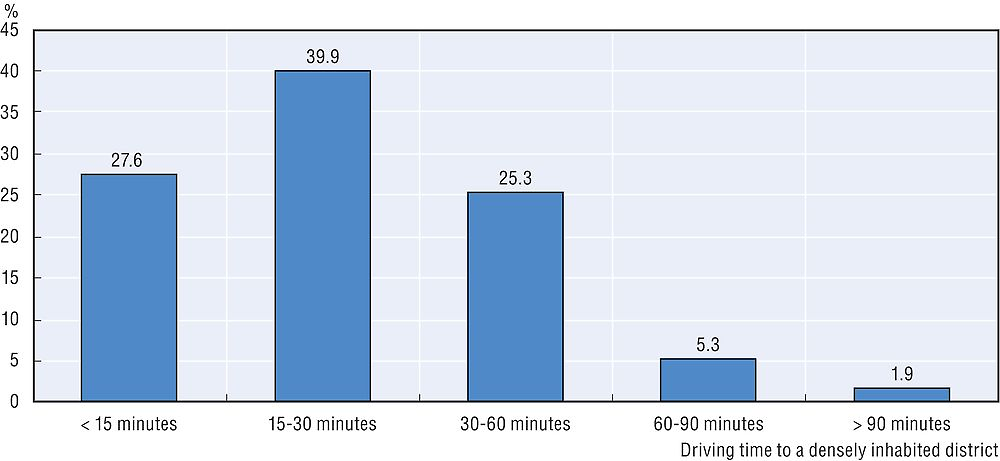

In fact, many of these hamlets are not facing any immediate threat. According to the agricultural census of 2010, two-thirds are within half an hour’s driving time of an urban centre, while over 90% are within 1 hour (Figure 4.5). In some cases, these urban centres may not be very large, but given that the criterion used requires a density of 4 000/km2, they are unlikely to be small, because pockets of such very high urban density do not often appear in isolation. This implies that the vast majority of hamlets are effectively within the commuter belts of reasonably good-sized cities and, indeed, almost 56% of hamlets fall within zones associated with city planning.11 This is not entirely surprising: it reflects the facts that cities in Japan – as in most places around the world – have historically grown up fastest in places with satisfactory food supplies near at hand. Large-scale, long-distance trade in perishable foodstuffs is a relatively recent development, so the best farmland in a country is often in the immediate vicinity of its largest cities. That is one reason that the conversion of farmland for urban development is such a perennially difficult issue: it is not a matter of countries “running out of land” but a problem that arises because the best farmland is in the places where the pressure for urban development is greatest.12

Note: Densely inhabited districts are defined as contiguous census blocks with a population of at least 5 000 and an overall population density of at least 4 000/km2.

Source: Agricultural census, 2010. Data provided directly by Official Statistics of Japan (Government of Japan).

The fact that so many hamlets are clustered around cities does not mean that they face no challenges. In some cases, they, like hamlets deep in rural areas, perform important environmental functions, and they are often exposed to negative externalities from nearby cities. However, the survival chances of hamlets close to cities are probably greater than those of more remote places. Issues like connectivity are less of a problem for hamlets close to cities, and they have many more options when it comes to survival strategies, since they can be more attractive to commuters and retirees, and they may have particular appeal for young people wishing to start families. Attention to landscape and rural amenities can help them differentiate the quality of life they offer from that of nearby cities while retaining many of the benefits of proximity to urban services.

The rationale for policy towards small hamlets needs to be crystallised

Perhaps the most fundamental problem with respect to the survival of rural hamlets lies in the fact that the government has yet to define the rationale for supporting their continued existence. To say this is not to suggest that the authorities should simply turn their back on such communities and leave them to their fates. On the contrary, there are a number of reasons why the authorities do not want to see them disappear. The point is rather that it is impossible to devise efficient and effective policies to support the viability of agricultural hamlets without a clear understanding of what those reasons are. Once this rationale is clarified, it becomes possible to determine which policy interventions to preserve hamlets would make sense. This is a critical point because, given Japan’s demographic trends, there is no doubt that many hamlets will disappear and the resources to support their continued viability are in any case limited; the government cannot ensure the survival of all rural hamlets, and excessive dispersion of effort will undermine the effectiveness of policy. Of course, it is not for officials in Tokyo simply to decide which hamlets to maintain and which to close, but they will have to make decisions about infrastructure investment, support programmes and the like, and that requires a clear understanding of when, where and why policy should intervene to support hamlets’ viability. Some (probably many) hamlets that do not meet those criteria will still survive – they will find other strategies – and some that qualify for support may not prove to be viable in the long run. But national policies need to be framed so as to ensure that measures for the support of rural hamlets are broadly consistent with the broader goals of the Grand Design and the National Spatial Strategy.

One of the obvious concerns is the role hamlets play in agricultural production, particularly in managing rivers, irrigation systems and other watercourses. Major infrastructures (reservoirs, intakes, pumps and main canals) are usually operated and maintained by the Land Improvement Districts (LIDs).13 However, tertiary irrigation and drainage canals are generally managed by local residents (Figure 4.6). This would suggest a clear agri-environmental case for supporting many hamlets. However, much depends on the direction of agricultural policy. It is often assumed that agricultural production and the viability of rural communities go hand in hand, but this is not necessarily the case. Rice production is not labour-intensive, and efforts to foster the consolidation of rice farms in the interests of productivity reduce labour demand. While rice farms remain very small (2 ha on average, according to MAFF), the share of agricultural lands cultivated by large-scale (10 ha or more) farmers is increasing rapidly: it rose from 7.9% in 2000 to 18.7% in 2010. In many areas, there is a tension between the promotion of agricultural productivity and sustaining the population, especially where the main actors are large-scale farmers who take over land from small-scale producers (Box 4.7). In some suburban areas, though, farmland consolidation and the diversification of agricultural production are proceeding in tandem, which is helping to sustain or even increase the local population. That is why many prefectures prefer to diversify agricultural production and to promote collective farming in areas where rice is the major crop. In many areas, there has been a move towards community agriculture, in which a large number of small farmers operate as one larger organisation, contributing land, labour or capital as they are able. In hamlets close to cities, there is a lot of part-time farming. Both strategies help sustain hamlets’ population but at the expense of lower farm productivity.

Source: Based on the data of the General counter of Official Statistics of Japan (2015), Census of Agriculture and Forestry, http://www.e-stat.go.jp/SG1/estat/List.do?bid=000001047529&cycode=0 (15 July 2015).

Rice is Japan’s most important crop, not only from an economic point of view, but also from a social and environmental perspective. It accounts for only 12% of total value added in agriculture and fisheries, and this share has been gradually and steadily declining. However, rice farming is the largest user of land and water. It accounts for more than 50% of the total cultivated area in Japan and accounts for the majority of agricultural water consumption. Over the last decade, MAFF has sought to increase the productivity of agriculture with policies targeting large-scale farmers and promoting farm consolidation – a major departure from traditional policies, which supported all types of farmers, often enabling low-productivity small-scale and part-time farmers to remain in business, rather than exiting the market in favour of larger, more efficient producers. At present, “business farmers” (i.e. those who make their living as farmers rather than using part-time farming to supplement their incomes) are a minority of all farmers but they now cultivate around half of all farmland; MAFF is working to increase that figure to 80% over the coming decade.

The average age of farmers in Japan is quite high (around 66, according to MAFF but this includes many part-time farmers) and few young people work in the sector, so the time is in some respects quite propitious for consolidation. Retiring farmers often lease their land to larger producers.1 The problem is that farm consolidation could undermine the viability of rural hamlets. Given the size of most hamlets, an average hamlet could profitably sustain just one or at most two rice farmers. If the remaining farmers sell or lease their land to such a producer, this accelerates population outflow. Often, the landowner who stops farming remains in the hamlet but his children are unlikely to do so. To maintain and demonstrate the multifunctionality of agriculture, MAFF designed a second set of policies to ensure payments to hamlets collectively maintaining irrigation and drainage facilities, as well as companion policies focused on rural development. However, these payments are tiny compared to overall levels of agricultural support and the tension remains.

← 1. Some owners do not wish to sell, and many cannot: leasing is preferred by the large producers in many areas, because land prices do not reflect the use-value of the land in cultivation but rather the potential for conversion to other uses.

Source: Shobayashi, M. (2015), “Looking Back at the 15-Year Development of Direct Payments in Japan: Is Multifunctionality a ‘New Bottle’ for the ‘Old Wine’?”, Agriculture and Economics, Special Issue, March, pp. 39-52 (in Japanese); information provided directly by the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries.

MAFF has unveiled a basic plan with a multi-faceted approach to rural revitalisation…

The policies for rural revitalisation in the 2015 Basic Plan for Food Agriculture and Rural Areas are grouped into three categories:

-

The first group is to preserve multifunctionality via a new direct payment scheme focusing on collective action for the maintenance of irrigation and drainage facilities and a new initiative to foster the establishment of networks among neighbouring hamlets.

-

The second category concerns the revitalisation of rural economies through the use of local resources. This includes support for the so-called “sixth industry”. “Sixth-order industrialisation” essentially involves the formation of integrated value chains encompassing production, processing, distribution and marketing by linking agriculture, forestry and fisheries producers to those with expertise in the secondary and tertiary sectors, particularly processing and marketing. The name reflects the fact that rural producers of (primary) agricultural commodities are engaged in processing (secondary) activities and in distribution/marketing (tertiary) operations – hence, 1 + 2 + 3 = 6. There are also measures to promote the consumption of local foods and to support the development of biomass and renewable energy, as well as greater use of ITC in farming and distribution.

-

The third group of policies aims to promote urban-rural exchanges, like green tourism, children’s experiences of agriculture and rural life, and welfare farms to foster collaboration with the medical, welfare and food industries.

In principle, each of these three strands of policy has much to recommend it and is consistent with the “small stations” initiative and other elements of the broader revitalisation effort. A focus on multifunctionality would help to clarify the rationale for supporting hamlets and also the instruments to be used. The “sixth industry” initiative has already begun to bear fruit in some places (see below). It is unlikely to have a dramatic macroeconomic impact – urban areas will retain their advantage in secondary and tertiary activities14 – but it really does not need to anyway: successful sixth-industry initiatives are already showing that, in a thinly populated rural area, even a small niche activity can make a big difference. Much the same can be said of the attempts to promote migration from cities to rural areas: they will not alter the settlement pattern much but they can make a difference in local communities, particularly those well-placed to attract former urbanites.

Elements of the plan’s agricultural policies will also have important implications for rural development. It promotes the production of fruits and vegetables, as well as livestock products, which are higher value-added products and also require more labour. This is consonant with the aim of increasing farmers’ income from farming and with sustaining more farmers on the land. Another important twist in the plan is the decision to treat community farming groups as business farmers (ninaite, or literally “leaders”). Ninaite are considered to be the future of Japanese agriculture. They are defined in the plan as efficient and stable farmers whose lifetime income and working hours are equivalent to those of people employed full-time in other industries in their regions. In keeping with policies to favour productivity, the government is promoting farmland consolidation and the promotion of full-time farmers, they include certified farmers15 and those expected to be certified, as well as community farming groups. The plan states that the government will support business farmers with subsidies, loans, financing, etc., and promotes the corporatisation of farming. The public corporations for farmland consolidation to core farmers through renting and sub-leasing (farmland banks), which were established in each prefecture in 2014, are also now incorporated into the basic plan as part of the consolidation drive. A key priority for MAFF is creating conditions to attract younger people into full-time farming; the ministry estimates that Japan needs to double the number of new farmers who start farming and remain with it and to increase the number of farmers aged 40 or less to 400 000 by 2023. This is to secure roughly the number of farmers needed to maintain the current level of agricultural production.

…but more can be done to address non-agricultural facets of rural development

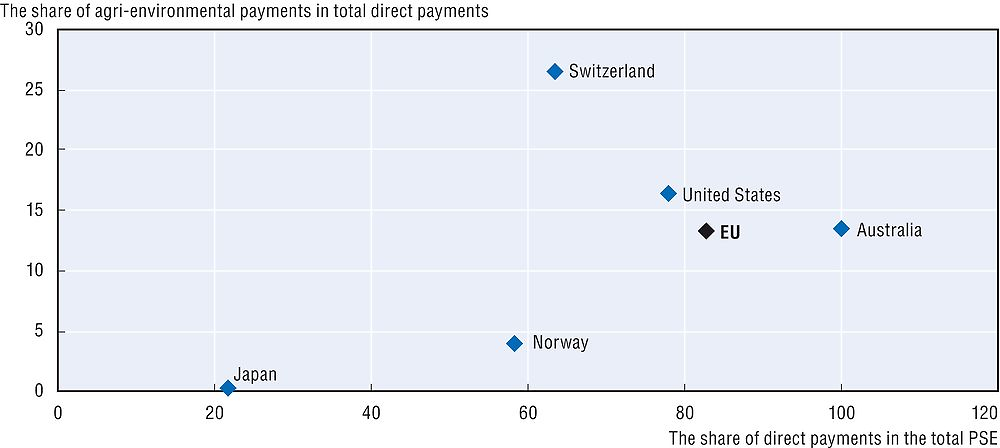

One major limitation of the 2015 plan is that its primary rural development component is still concerned with agriculture.16 The biggest policy measure in the rural development framework is the system of direct payments for maintaining irrigation and drainage facilities and agricultural roads but also for environmental protection and planting on roadsides. However, a policy focused on how local communities can support farm production and environmental/landscape management will not make hamlets attractive enough to draw young people into rural areas unless they are farmers. In fact, much more could be done by giving greater weight to other agri-environmental concerns, particularly landscape management. This would serve a dual purpose, advancing the goals of sustainable agriculture and also making hamlets more attractive places for non-farmers to settle. The share of direct payments in the total producer-support estimate17 for Japan is exceptionally low, at just below 22% in 2014, compared with levels of 58-83% in OECD Europe (the EU21, Norway and Switzerland), 78% in the United States and 100% in Australia. Moreover, the share of agri-environmental payments in total direct payments is also extremely low (Figure 4.7).18 In sum, just under 0.05% of producer support to agriculture in Japan consists of agri-environmental payments.

Source: OECD (2015d), Producer and Consumer Support Estimates (database), OECD, Paris, http://www.oecd.org/agriculture/agricultural-policies/producerandconsumersupportestimatesdatabase.htm (accessed 10 July 2015).