Executive summary

Addressing fragility will be central to realising the post-2015 Sustainable Development Goals

States of Fragility 2015 is published at an important time for international development co-operation. In 2015, the world’s governments will agree on a successor framework to the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs). This framework will be more ambitious than ever, requiring in turn more urgent efforts to reduce the persistent poverty in fragile situations and strengthen the institutions that can deliver economic and social development.

Fragile states and economies lag behind in achieving the Millennium Development Goals

Many fragile states and economies have made important strides toward reaching the MDGs, but as a group they have lagged behind other developing countries. Nearly two-thirds of those now considered fragile are expected to fail to meet the goal of halving poverty by 2015. Just one-fifth will halve infant mortality by 2015, and just over one-quarter will halve the number of people who do not have access to clean water. These trends point to a growing concentration of absolute poverty in fragile situations. Today, the 50 countries and economies on the 2015 fragile states list (which is a sample group for analysis) are home to 43% of people living on less than USD 1.25/day; by 2030, the concentration could be 62%.

Fragility should be assessed differently in the post-2015 era

This report offers a new tool for assessing fragility that is more comprehensive than the traditional single categorisation of “fragile states”, and recognises the diversity of risks and vulnerabilities that lead to fragility. It identifies countries the most vulnerable in five dimensions of risk and vulnerability linked to fragility, and asks how likely they are to achieve the UN Open Working Group’s post-2015 goals and targets in those five dimensions: 1) violence (peaceful societies); 2) access to justice for all; 3) effective, accountable and inclusive institutions; 4) economic foundations; 5) capacity to adapt to social, economic and environmental shocks and disasters.

This approach to assessing fragility can help to identify national and international priorities by shedding light on which countries are the most vulnerable to risks, and can inform international financing allocations. This report proposes a model that can be modified to reflect the final negotiated development framework that will emerge in late 2015.

Left unaddressed, fragility will impede the post-2015 development goals

The goal of eradicating poverty will remain beyond the reach of many countries unless concentrated efforts begin now to address fragility. If institution building and conflict reduction continue at their existing pace, by 2030 nearly half a billion people could remain below the USD 1.25/day poverty line. Under a moderately optimistic scenario, in which countries’ institutions develop and conflict declines faster, that figure could reduce to 420 million people. A best-case scenario of rapid institution building and a widespread decline in conflict would reduce poverty to 350 million people.

Aid fills a significant finance gap in many fragile states, but there are huge imbalances in its distribution

While per capita official development assistance (ODA) to fragile situations has almost doubled since 2000, aid is distributed unevenly. Afghanistan and Iraq received significant flows in the MDG era – 22% of all ODA to fragile states and economies. At the same time, 10 of the world’s 11 aid orphans have been part of this pool of countries.

Remittances, the largest aggregate flow to fragile states and economies, benefit a small number of middle-income countries with big diaspora populations. Only 6% of foreign direct investment (FDI) to developing countries in 2012 went to fragile situations, and it was concentrated in just ten resource-rich countries.

Development finance can be better monitored and targeted at reducing fragility

Aid budgets are still adapting to the Peacebuilding and Statebuilding Goals (PSGs) endorsed in 2011 by conflict-affected and fragile countries, development partners and civil society. While there is no agreed framework for tracking aid to support the PSGs, a working model found that it remained low in 2012. Just 4% of ODA to fragile states and economies was allocated to the PSGs for legitimate politics, 1.4% for security and 3% for justice.

Some evidence suggests that aid is better aligned to needs for institution building: least developed countries (LDCs) with lower levels of institutional capacity receive higher per capita ODA financing. A significant burden of violence is concentrated in lower middle-income countries, however, and these contexts receive relatively limited per capita aid flows. Vulnerability to shocks and disasters is greatest among a cluster of LDCs and lower middle-income countries, but ODA to these states is not commensurate with their greater exposure.

Scaling up ODA to the poorest and most fragile countries could help to make greater inroads into reducing fragility in the post-2015 era, as can non-concessional finance to middle-income countries and investments in global public goods.

New norms are needed for tracking spending on peace and security

No international norms exist for tracking peace and security spending. Only UN peacekeeping (almost USD 8.5 billion per year) and ODA expenditures on security are tracked. A small portion of ODA, just 1.4% in 2012, is spent on security sector reform in fragile states. Agreeing on targets and norms for monitoring spending on global peace, security and conflict prevention would sharpen the focus on the quality of international efforts to prevent and reduce crises.

National ownership and international commitment are needed to reduce fragility

Fragile states have untapped opportunities to pursue development. Capitalising on them will require national ownership, international commitment and innovation. Multi-sectoral efforts to reduce violence, build trust in government and improve the quality of public services will be key to achieving a post-2015 goal for peaceful and inclusive societies.

Aid will need to be much smarter in the post-2015 era

The post-2015 debate offers a historic opportunity to make the international approach to fragility and financing “fit-for-purpose”. Far greater international political will is needed to support nationally owned and led plans, build national institutions at a faster rate, and help countries to generate domestic revenues and attract private finance. To this end, donors must be more flexible and risk tolerant to on-budget aid modalities that build national institutions. The international community can also develop more demand-driven aid innovations that support domestic revenue generation, enable South-South and triangular co-operation, and make greater use of public finance instruments that help to attract FDI.

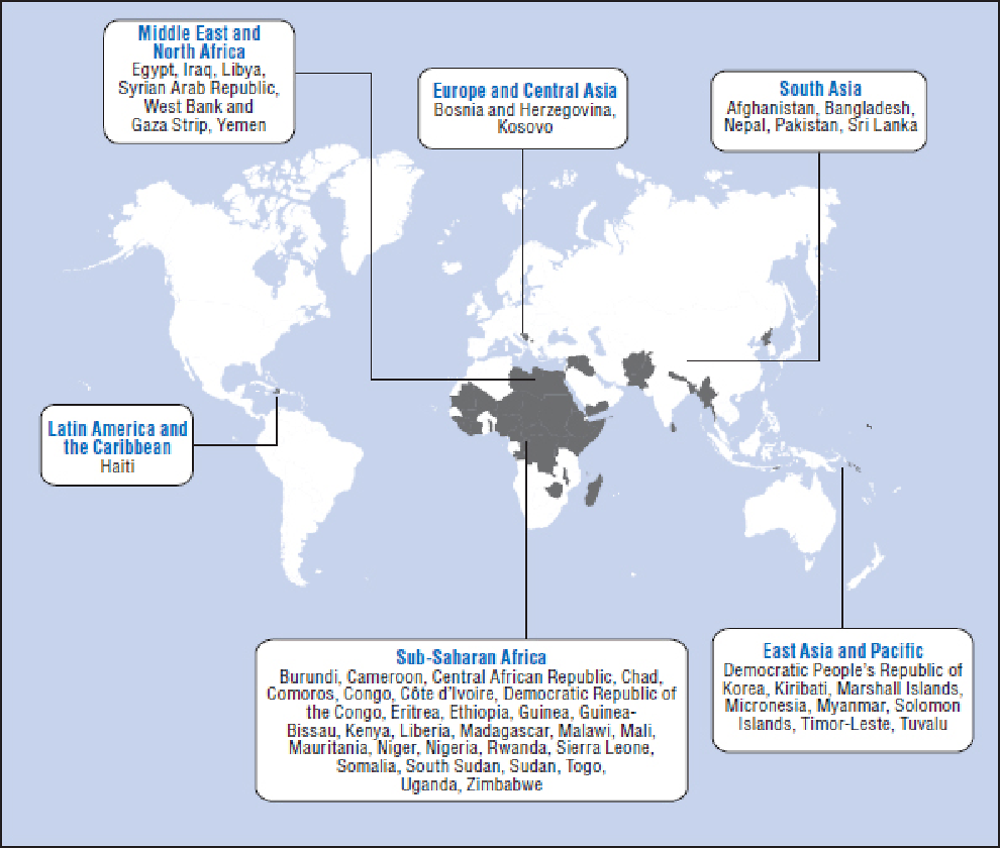

Note: For this report, the list of fragile states and economies assembled by the OECD results from a compilation of two lists: the countries on the World Bank-African Development Bank-Asian Development Bank Harmonized List of Fragile Situations, and the countries on the Fragile States Index developed by The Fund for Peace which are in the “alert” and “warning” categories (scores above 90).

Sources: 2014 Harmonized List of Fragile Situations put together by the World Bank, Asian Development Bank and African Development Bank, available at: http://siteresources.worldbank.org/EXTLICUS/Resources/511777-1269623894864/HarmonizedlistoffragilestatesFY14.pdf; The Fund for Peace (2014), “Fragile States Index 2014”, The Fund for Peace, Washington, DC, available at: http://ffp.statesindex.org.