Chapter 5. Ensure that motivation translates into a key asset for immigrant communities

Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) data shows that, in most countries, students with an immigrant background are more motivated to achieve and hold more ambitious educational and professional expectations than native students. This stems from parents’ and students’ desire to improve their socio-economic status, which is often the reason to migrate in the first place. However, many immigrant children lack the foundation skills that are necessary to succeed in school and suffer from cumulative disadvantage, which make them underperform compared to their ambitions.

This chapter examines policies and practices that can ensure immigrants and their families capitalise on high levels of motivation. Examples include: ensuring that individuals hold ambitious, but realistic aspirations by supporting skills development so individuals are able to realise their ambitions; providing career and education guidance by working with individuals and their families on the development of short- medium- and long-term plans and targets.

The statistical data for Israel are supplied by and under the responsibility of the relevant Israeli authorities. The use of such data by the OECD is without prejudice to the status of the Golan Heights, East Jerusalem and Israeli settlements in the West Bank under the terms of international law.

In public debates, opponents of migration sometimes depict immigrants as “lazy” and not willing to work hard. They blame immigrants for their poor academic, professional or integration outcomes, claiming that if only immigrants were more motivated, they would succeed. These opinions are mostly driven by the view that immigrants are a burden for welfare systems and that they come to host countries to exploit their benefits, without contributing in return. There is evidence that welfare concerns are the strongest driver of attitudes towards migration (Dustmann and Preston, 2007[1]).

PISA data shows that, in most countries, students with an immigrant background are more motivated to achieve and hold more ambitious educational and professional expectations than native students. This stems from parents’ and students’ desire to improve their socio-economic status, which is often the reason for migrating in the first place. However, many immigrant children lack the foundational skills necessary to succeed in school and suffer from cumulative disadvantage, which can lead to underperformance relative to their ambitions.

By ascribing immigrants’ poor outcomes to their low motivation, individual immigrants are blamed instead of tackling the real problem: understanding why high motivation and ambition among immigrant students does not translate into successful outcomes. The second route is likely to be more demanding and less popular since it might shift the blame from the immigrants to the education system and its shortcomings. However, if these problems are not resolved, high motivation among immigrants can undermine their integration in the long run. Unrealised ambitions can lead to psychological distress among adults, and specifically, among immigrants, unrealised ambitions can be detrimental to labour market integration and overall social cohesion.

This chapter examines some key differences in motivation and expectations between immigrant and native students, showing that the former are often more motivated and hold more ambitious (yet sometimes unrealistic) expectations for their future. It then outlines a set of principles that can guide the design and implementation of policies and practices to ensure that immigrants and their families capitalise on high levels of motivation. Examples include: ensuring that individuals hold ambitious, but realistic aspirations by supporting skills development, providing career and education guidance, and helping individuals and their families develop realistic short-, medium- and long-term plans and targets.

Differences in achievement motivation

One of the most important ingredients of achievement, both in school and beyond, is the motivation to achieve (OECD, 2013[2]). In many cases, people with less talent, but greater motivation to reach their goals, are more likely to succeed than those who have talent but are not capable of setting goals for themselves and staying focused to achieve them (Duckworth et al., 2011[3]; Eccles and Wigfield, 2002[4]).

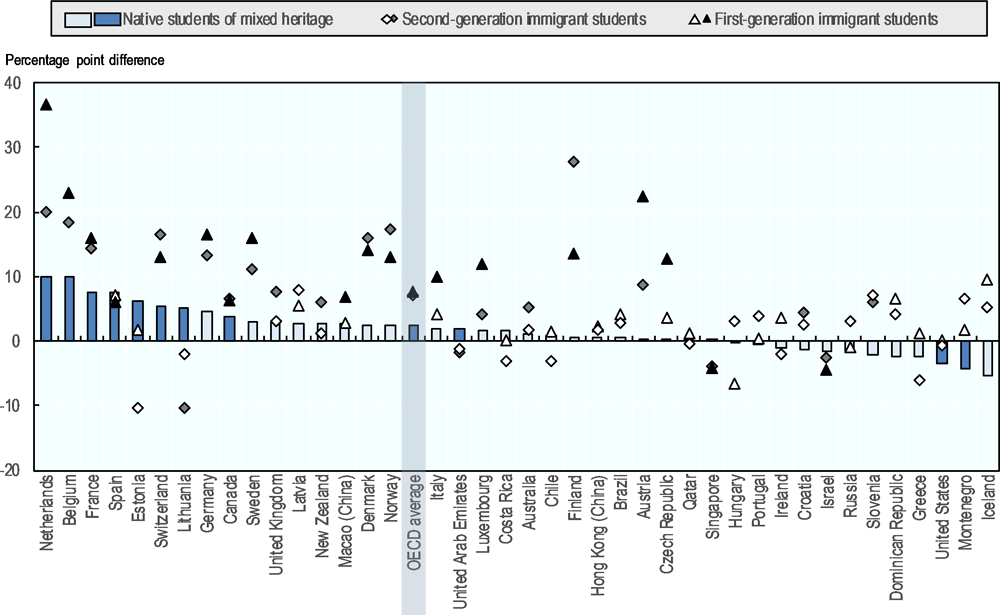

Students with an immigrant background tend to have greater achievement motivation than their native peers, measured by the extent to which students report strongly agreeing or agreeing with the statement ‘I want to be the best, whatever I do’. Figure 5.1 shows that in 20 out of 40 countries and economies with available data, first-generation immigrant students were more likely to express high levels of achievement motivation compared to native students. The inverse was true in only two countries. In Austria, Belgium, France, Germany, the Netherlands and Sweden, the difference was above 15 percentage points.

In the wide majority of countries, second-generation immigrant students and native students of mixed heritage reported levels of achievement motivation at least as high as native students. Only native students of mixed heritage in Colombia, Montenegro and the United States, second-generation immigrant students in Israel, Lithuania, Singapore and the United Arab Emirates, and first-generation immigrant students in Israel and Singapore, were less likely than native students to report so. In all other countries where significant differences between groups were observed, immigrant students expressed motivation to achieve.

The achievement motivation of students with an immigrant background is noteworthy, given widespread concern over lack of engagement and motivation to learn among secondary school students, especially socio-economically disadvantaged students, in many countries (OECD, 2013[2]). Despite facing many adversities, many students with an immigrant background display motivational resilience, and this represents a key asset for their integration journey.

Expectations to complete tertiary education

Students who hold ambitious expectations about their educational prospects are more likely to invest effort into their learning and take advantage of the educational opportunities available to them to achieve their goals (OECD, 2012[5]; Borgonovi and Pál, 2016[6]; OECD, 2017[7]; Nurmi, 2013[8]; Beal and Crockett, 2010[9]; Morgan, 2005[10]; Perna, 2000[11]). Therefore, expectations of further education can, in part, become self-fulfilling prophecies. When comparing students with similar levels of skills and similar attitudes towards school, those who expect to graduate from university are more likely than those who do not hold such expectations to earn a university degree (OECD, 2012[5]).

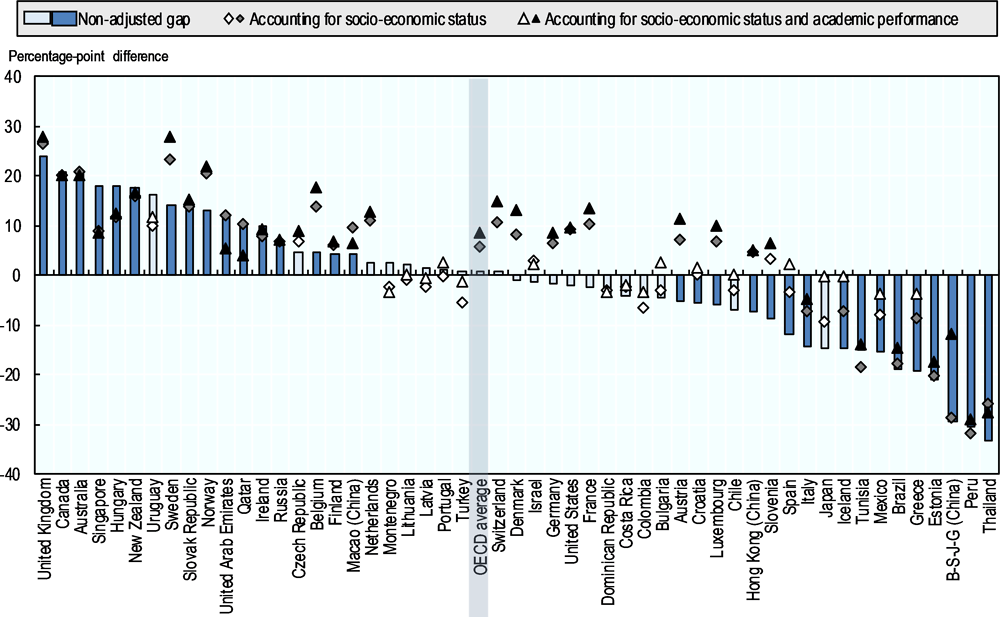

Despite the considerable challenges they often face, many immigrant students hold high educational expectations. Figure 5.2 shows that in 15 out of 52 countries and economies with available data, immigrant students who participated in PISA 2015 were more likely to expect to complete tertiary education compared to native students. In 11 countries they were over 10 percentage points more likely. By contrast, in 16 countries and economies, native students held more ambitious expectations for their education than native students did.

When comparing students of similar socio-economic status and, even more so, when comparing students of similar socio-economic status and academic performance, immigrant students are more likely than native students to hold ambitious expectations for their education. In 27 out of 52 countries and economies with available data, immigrant students were more likely to expect to complete tertiary education; the opposite was true in only seven countries and economies. On average across OECD countries, the percentage of immigrant students who expected to earn a university degree was eight percentage points greater than the percentage of native students who expected to do so.

PISA results also show that in most countries, immigrant students are more likely than native students to expect to work as managers, professionals or associated professionals, especially when comparing students with similar socio-economic status and academic performance. The data indicates that many immigrant students hold ambitious views for their futures and display the will to be active and successful contributors to society. The role of education systems is to nurture these ambitions and enable students to turn them into realised outcomes.

Unrealistic expectations

When students who expect to complete tertiary education have foundational skills, they are more likely to be able to achieve their goals. Immigrant students whose academic skills match their educational ambitions are more likely to be successful beyond their secondary education. On average across OECD countries, only 74% of immigrant students who held ambitious expectations for their education reached baseline levels of academic performance in reading, mathematics and science. By contrast, 87% of native students who held ambitious educational expectations attained baseline academic proficiency, about 15 percentage points more than the percentage of immigrant students who fit this profile.

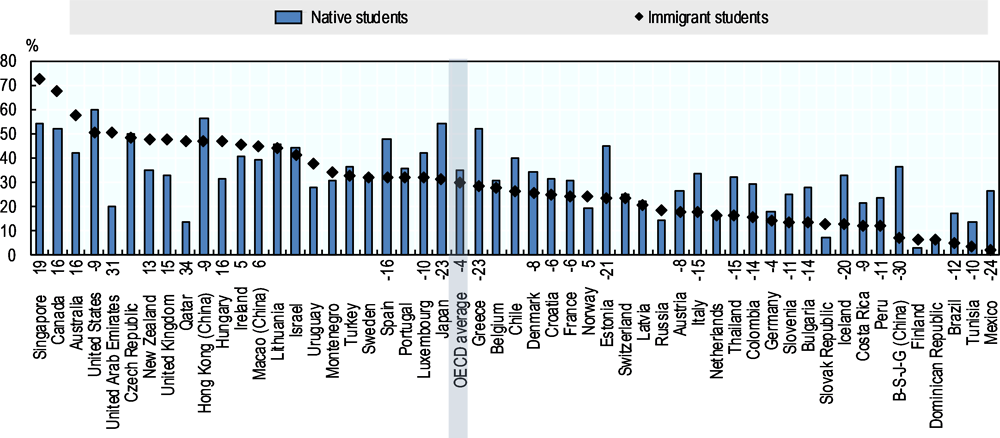

Figure 5.3 shows the percentage of immigrant and native students who expected to complete tertiary education and who reach baseline levels of proficiency in reading, mathematics and science. In 24 out of 52 countries and economies with available data, the percentage of students who held ambitious but realistic expectations of further education was lower among immigrant students than among native students. The opposite was true only in Australia, Canada, Hungary, Ireland, Macao (China), New Zealand, Norway, Qatar, Singapore, the United Arab Emirates and the United Kingdom. On average across OECD countries, immigrant students were four percentage points less likely than native students to hold ambitious educational expectations and attain baseline academic proficiency.

Students who hold ambitious educational (and professional) expectations but do not attain baseline academic proficiency are unlikely to realise their goals. When expectations for the future are unrealistic, setting ambitious goals can have negative effects on immigrant integration in the long-term. Research has shown that unrealised ambitions are associated with psychological distress, such as stress and anxiety (Wrosch et al., 2007[12]), or long-term mental health problems (Reynolds and Baird, 2010[13]). Unrealised ambitions might have additional consequences for immigrants, who, in many cases, choose to leave their country specifically to achieve those goals. Migrants who do not manage to achieve baseline academic proficiency might feel disillusioned and disappointed by their host country and as a result their social attitudes might change and their efforts to integrate might be reduced.

Immigrant students appear to have levels of motivation and ambition at least as high as their native peers, so cases of failed integration are likely not attributable to a lack of motivation. Paradoxically, it appears that in many cases, immigrant students are “excessively motivated” and express unrealistically high expectations for their future. To ensure the successful integration of these students, education systems should either give them means to effectively achieve those goals, or redirect them towards more realistic, yet gratifying goals.

From evidence to action: Lessons from the field including examples of policies and practices to capitalise on the motivation of immigrants for long-term well-being

This section highlights policies and practices that countries and schools have used to draw on the motivation of students with an immigrant background. It provides policy responses and country examples at different levels of governance and offers opportunities and practical applications that can be assessed to promote the successful integration of students with an immigrant background.

Provide skills support to students and adults with an immigrant background to realise their ambitions

While students with an immigrant background might be highly motivated to achieve, they may not necessarily possess sufficient skills to reach their targets. Assessing the skills of students with an immigrant background, both foreign-born children who arrived after the start of schooling as well as native-born children of foreign-born parents, can help identify the needs of each individual child and target training. Identifying specific needs and targeting training can help students with an immigrant background gain the skills needed to realise their ambitions. Support requires an accurate assessment of children’s language skills (in both the mother tongue and the language of instruction) and other competencies at the time of entry into the education system as well as during their education. Continued assessment throughout their education is important because some children with an immigrant background may not exhibit difficulties at the beginning, but might progressively fall behind due to a lack of language practice and support at home. Poor measures of assessment upon entrance into the school system can have a detrimental impact on immigrant children because these children are more likely to be allocated to special education and lower-ability tracks (OECD, 2018[14]). This will not enable them to realise their ambitions and capitalise on their high motivation.

Some countries have practices in place to provide support to students with an immigrant background. The Finnish model of integrating newly arrived students into mainstream education provides that within the first year, an individual curriculum is designed for each student, tailored to his/her needs and based on his/her previous school history, age and other factors that affect school work. The individual curriculum is set in cooperation between the teacher, the student and the family (Dervin, Simpson and Matikainen, 2017[15]). The Finnish model can serve as an example on how other countries could implement an early assessment of skills and individual learning plan for all newly arrived students so that they are able to capitalise on their motivation to achieve.

Beyond the educational level, it is important to provide skills support to immigrants entering the labour market. Such support could boost growth and reduce welfare expenditures on immigrants (Zorlu, 2011[16]). Integrating immigrants more effectively into the labour market could also facilitate social integration and reduce the social costs of exclusion. International experience suggests that strengthening social connections and improving language proficiency can have strong positive effects on immigrants’ labour market outcomes in terms of employment, earnings and occupational status (Chiswick and Wang, 2016[17]).

One example is the job-related language courses for immigrants in Germany (OECD, 2017[18]). The programme combines language courses with employment, vocational and educational training and active labour market programmes. The courses provide German language and skills building with employment services. They start by assessing the participant’s proficiency in German, what kind of professional qualifications they hold, and what more they need to learn from the courses (European Commission, 2016[19]). German lessons cover general language skills (vocabulary and grammar) and workplace language skills. For skills building, participants learn about general and specialised career-related knowledge, job application training, and mathematics and information technology. The modules are well connected to facilitate the transition into the German labour market (European Commission, 2016[19]).

Offer specific educational and career guidance to students with an immigrant background

Students with an immigrant background are often highly motivated, but it is crucial that they are able to capitalise on their motivation and have realistic expectations to achieve their goals. Information on education and career opportunities and on the requirements of different pathways should be made available so that students with an immigrant background can fully benefit from education and training services (OECD, 2012[20]). Individual career counselling to provide specific advice on career decisions and direct contact with the professional world are also components of career guidance (Musset and Mytna Kurekova, 2018[21]).

Guidance is crucial in countries with differentiated schooling and education sectors, where students and their families are expected to make important decisions on which school a student will attend and/or where there are few second-chance opportunities for students. Education and career guidance is thus particularly important for students with an immigrant background, given the limited knowledge students and their parents might have about career opportunities, and how best to prepare for them.

Career guidance can include providing information about careers, using assessment and self-assessment tools, interviews, career-education programmes, taster programmes, work-search programmes and transition services. Young people in all levels of education often face obstacles to obtaining the guidance they need, because of a lack of access, poor quality of services, or limited resources that are not always dedicated to career guidance (OECD, 2018[14]). Furthermore, studies on career guidance (Sawyer, 2006[22]; Resh and Erhard, 2002[23]; Yogev and Roditi, 1987[24]) suggest that immigrant and/or ethnic-minority students might be advised to temper their career aspirations, implicitly or explicitly, based on low and unfair expectations for immigrant and/or minority students.

Quality career guidance goes hand in hand with education guidance for students with an immigrant background and their families. In Sweden, municipal authorities have a responsibility to inform newly arrived families of their rights with regard to pre-school and school education. Interpreting services should be made available, when required, at the welcome meetings for recently arrived families. These families are also entitled to an interpreter to enable them to participate in the ‘personal development discussion’ held with all parents twice a year. Schools are obliged to communicate with all parents and must therefore adopt the measures necessary (MIPEX, 2015[25]).

Another example stems from Finland, which has received an increased number of refugees and immigrants with new demands for education and employment and related services such as guidance and validation of prior learning. A new reform on career guidance services aims to take these new demands into account (ICCDPP, 2017[26]). The one-stop guidance centres provide basic support to youth under 30 years going through life transitions. The centres have institutional representation from municipal, education, social and health authorities.

Guide immigrant families towards realistic expectations and targets as well as work closely with counsellors

Parent engagement is crucial for students with an immigrant background to achieve positive academic, and social and emotional outcomes. Numerous studies indicate that students are better learners when their parents are involved in their education (Desforges and Abouchaar, 2003[27]; Fan and Chen, 2001[28]; Jeynes, 2007[29]; OECD, 2012[20]; Schofield, 2006[30]).

However, there are a number of challenges regarding the involvement of immigrant parents in the educational and career choices of their children. For instance, parents might face language difficulties as well as cultural bias (e.g. specific stereotypes linked to certain education pathways) and barriers regarding their involvement with school staff (Musset and Mytna Kurekova, 2018, p. 65[21]). Furthermore, immigrant parents might lack sufficient information about the education system (including policies, rules, means of test taking and learning) and career paths in a new institutional context. This may prevent them from advising their children outside traditional family career pathways (Gonzalez and al., 2013[31]; Mitchell and Bryan, 2007[32]; Musset and Mytna Kurekova, 2018[21]). Studies show that family roles, expectations and values tend to differ across cultures, and are projected into career decisions of immigrant students (Ma and Yeh, 2010[33]; Mitchell and Bryan, 2007[32]; Bimrose and McNair, 2011[34]).

Due to the difficulties associated with immigration, immigrant parents may believe that the best way for their children to succeed in the new country is to thrive academically in their new schools, graduate from high school, and pursue postsecondary education (Fuligni and Fuligni, 2007[35]; Suárez-Orozco, Suárez-Orozco and Todorova, 2008[36]). Other studies find an association between parents’ expectations and students’ academic achievement which might reflect both that parents whose children attain baseline academic proficiency tend to hold more ambitious expectations for them, but also that parents’ expectations and their encouragement and support have a positive impact on students’ achievement (OECD, 2018[14]; Areepattamannil and Lee, 2014[37]).

More specifically, Roysircar, Carey and Koroma (2010[38]) studied United States college major preferences among Asian Indian students and found that parents’ preferences for science and math significantly shaped preferences as well as actual choices of first and second-generation students. Ma and Yeh (2010[33]) analysed how individual and family factors affected educational and career aspirations of Chinese immigrant youth in New York and found a key importance of English fluency. Higher English fluency combined with career-related support from parents led to higher career and educational aspirations, while lower fluency predicted plans to work immediately after high school (Musset and Mytna Kurekova, 2018[21]).

Whatever the parents’ educational background, parents who value education and are able to provide their children with strategic direction and support can help their children’s integration into the host country school system. These efforts also promote a climate at school and at home, that supports the academic, social and emotional development of their children.

Visiting homes, recruiting culturally appropriate and trained specialists, providing learning resources and information to families, launching awareness campaigns, and training teachers and staff to work with culturally and linguistically diverse children are all ways that education systems can support immigrant parents in their efforts to help their children succeed (OECD, 2014[39]).

Furthermore, it is important for school counsellors to work closely with families and educate them about different types of educational and career opportunities available in the host country. For instance, parent-teacher meetings could be used for distributing information on university admissions and financial support so that parents can be involved in the career development process and provide assistance for their children. Additionally, providing this information in the immigrant’s mother tongue and during hours convenient for working parents could be a helpful measure for guiding immigrant families towards realistic expectations concerning their children (Ma and Yeh, 2010[33]).

References

[37] Areepattamannil, S. and D. Lee (2014), “Linking Immigrant Parents’ Educational Expectations and Aspirations to Their Children’s School Performance”, The Journal of Genetic Psychology, Vol. 175/1, pp. 51-57, https://doi.org/10.1080/00221325.2013.799061.

[9] Beal, S. and L. Crockett (2010), “Adolescents’ occupational and educational aspirations and expectations: Links to high school activities and adult educational attainment.”, Developmental Psychology, Vol. 46/1, pp. 258-265, https://doi.org/10.1037/a0017416.

[34] Bimrose, J. and S. McNair (2011), “Career support for migrants: Transformation or adaptation”, Journal of Vocational Behavior, Vol. 78/3, pp. 325-333.

[6] Borgonovi, F. and J. Pál (2016), “A Framework for the Analysis of Student Well-Being in the PISA 2015 Study: Being 15 In 2015”, OECD Education Working Papers, No. 140, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/5jlpszwghvvb-en.

[17] Chiswick, B. and Z. Wang (2016), Social contracts, Dutch language proficiency and immigrant economic performance in the Netherlands: a longitudinal study, IZA.

[15] Dervin, F., A. Simpson and A. Matikainen (2017), “EDINA Country Report – Finland”, Edina Platform, https://edinaplatform.eu/research/country-reports/.

[27] Desforges, C. and A. Abouchaar (2003), The Impact of Parental Involvement, Parental Support and Family Education on Pupil Achievements and Adjustment: A Literature Review RESEARCH, DfES publications, Nottingham.

[3] Duckworth, A. et al. (2011), “Self‐regulation strategies improve self‐discipline in adolescents: benefits of mental contrasting and implementation intentions”, Educational Psychology, Vol. 31/1, pp. 17-26, https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410.2010.506003.

[1] Dustmann, C. and I. Preston (2007), “Racial and Economic Factors in Attitudes to Immigration”, The B E Journal of Economic Analysis & Policy, Vol. 7/1.

[4] Eccles, J. and A. Wigfield (2002), “Motivational Beliefs, Values, and Goals”, Annual Review of Psychology, Vol. 53/1, pp. 109-132, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.53.100901.135153.

[19] European Commission (2016), ESF Success story: Job-related language courses for migrants in Germany go national, http://ec.europa.eu/social/main.jsp?langId=en&catId=89&newsId=2570&furtherNews=yes (accessed on 10 January 2019).

[28] Fan, X. and M. Chen (2001), “Parental involvement and students’ academic achievement: A meta-analysis”, Educational Psychology Review, Vol. 13/1, pp. 1-22.

[31] Gonzalez, L. and E. al. (2013), “Parental involvement in children’s education: Considerations for school counselors working with Latino immigrant families”, Professional School Counselling, Vol. 16, pp. 185-193.

[26] ICCDPP (2017), Finland- Country Paper, http://iccdpp2017.org/download/Country_Paper_Finland (accessed on 10 January 2019).

[29] Jeynes, W. (2007), “The relationship between parental involvement and urban secondary school pupil academic”, Urban Education, Vol. 42/1, pp. 82-110.

[35] Lansford, J., K. Deater-Deckard and M. Bornstein (eds.) (2007), Immigrant families and the educational development of their children, Guilford, New York.

[33] Ma, P. and C. Yeh (2010), “Individual and familial factors influencing the educational and career plans of Chinese immigrant youths”, Career Development Quarterly, Vol. 58/3, pp. 230-245.

[25] MIPEX (2015), “Policy indicators scores 2007-2014”, Migration Policy Integration Index, http://www.mipex.eu/download-pdf.

[32] Mitchell, N. and J. Bryan (2007), “School-family-community partnerships: Strategies for school counselors working with Caribbean immigrant families”, Professional School Counselling, Vol. 10/4, pp. 399-409.

[10] Morgan, S. (2005), On the edge of commitment : educational attainment and race in the United States, Stanford University Press, https://www.sup.org/books/title/?id=3634 (accessed on 25 June 2018).

[21] Musset, P. and L. Mytna Kurekova (2018), “Working it out: Career Guidance and Employer Engagement”, OECD Education Working Papers, No. 175, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/51c9d18d-en.

[8] Nurmi, J. (2013), “Socialization and Self-Development: Channeling, Selection, Adjustment, and Reflection”, in Handbook of Adolescent Psychology: Second Edition, https://doi.org/10.1002/9780471726746.ch4.

[14] OECD (2018), The Resilience of Students with an Immigrant Background: Factors that Shape Well-being, OECD Reviews of Migrant Education, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264292093-en.

[18] OECD (2017), OECD Skills Strategy Diagnostic Report: The Netherlands 2017, OECD Skills Studies, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264287655-en.

[7] OECD (2017), PISA 2015 Results (Volume III): Students’ Well-Being, PISA, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264273856-en.

[39] OECD (2014), International Migration Outlook 2014, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/migr_outlook-2014-en.

[2] OECD (2013), PISA 2012 Results: Ready to Learn (Volume III): Students’ Engagement, Drive and Self-Beliefs, PISA, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264201170-en.

[20] OECD (2012), Equity and Quality in Education: Supporting Disadvantaged Students and Schools, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264130852-en.

[5] OECD (2012), Grade Expectations: How Marks and Education Policies Shape Students’ Ambitions, PISA, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264187528-en.

[11] Perna, L. (2000), “Differences in the Decision to Attend College Among African Americans, Hispanics, and Whites”, The Journal of Higher Education Freeman Freeman, Vol. 71/2, pp. 117-141, https://doi.org/10.2307/2649245.

[23] Resh, N. and R. Erhard (2002), “Pushing up’ or ‘cooling out’? Israeli counsellors’ guidance on track placement”, Interchange, Vol. 33/4, pp. 325-349.

[13] Reynolds, J. and C. Baird (2010), “Is There a Downside to Shooting for the Stars? Unrealized Educational Expectations and Symptoms of Depression”, American Sociological Review, Vol. 75, pp. 151–172.

[38] Roysircar, G., J. Carey and S. Koroma (2010), “Asian Indian College Students’ Science and Math Preferences: Influences of Cultural Contexts”, Journal of Career Development, Vol. 36/4, pp. 324-347, https://doi.org/10.1177/0894845309345671.

[22] Sawyer, L. and M. Kamali (eds.) (2006), Att koppla drömmar till verkligheten. SYO-konsulenters syn på etnicitet i övergången från grundskolan till gymnasiet” [Connecting dreams to reality. The views of career counsellors on significance of ethnicity in the transition from primary to secondary], Fritzes, Stockholm.

[30] Schofield, J. (2006), Migration Background, Minority-Group Membership and Academic Achievement Research Evidence from Social, Educational, and Developmental Psychology, Programme on Intercultural Conflicts and Societal Integration (AKI), Social Science Research Center Berlin.

[36] Suárez-Orozco, C., M. Suárez-Orozco and I. Todorova (2008), Learning a New Land: Immigrant Students in American Society, Harvard University Press, Cambridge.

[12] Wrosch, C. et al. (2007), “Giving Up on Unattainable Goals: Benefits for Health?”, Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, Vol. 33/2, pp. 251-265, https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167206294905.

[24] Yogev, A. and H. Roditi (1987), “School counsellors as gatekeepers: guidance in poor versus affluent neighbourhoods”, Adolescence, Vol. 22/87, pp. 625-639.

[16] Zorlu, A. (2011), Immigrant participation in welfare benefits in the Netherlands, IZA.