Adult mental health

Good mental health is vital for people to be able to lead healthy and productive lives. Living with a mental health problem can have a significant impact on daily life, contributing to worse educational outcomes, higher rates of unemployment, and poorer physical health. As of 2020, the COVID-19 crisis is also having a negative impact on mental wellbeing, especially amongst young people and people with lower socio-economic status (see Chapter 1).

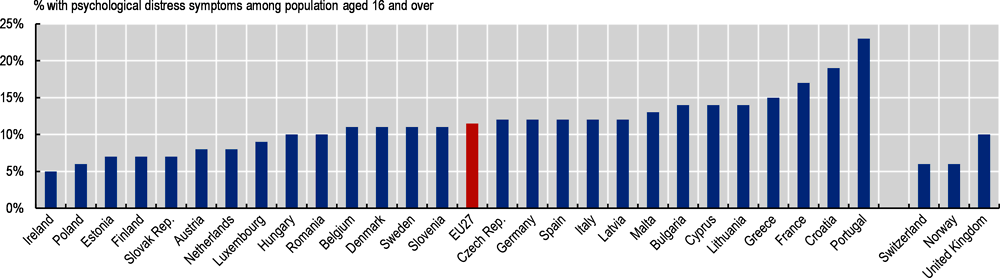

In 2018, one in nine adults (11%) on average across EU countries had symptoms of psychological distress (Figure 3.20). Prevalence ranged from about 5% in Ireland, Poland, Estonia, the Slovak Republic and Finland, to about 20% or over in Croatia and Portugal. While these rates suggest that psychological distress is common in all EU countries, they do not reflect a clinical diagnosis. Self-reported data can be influenced by cultural differences, and different levels of stigma and literacy around mental health.

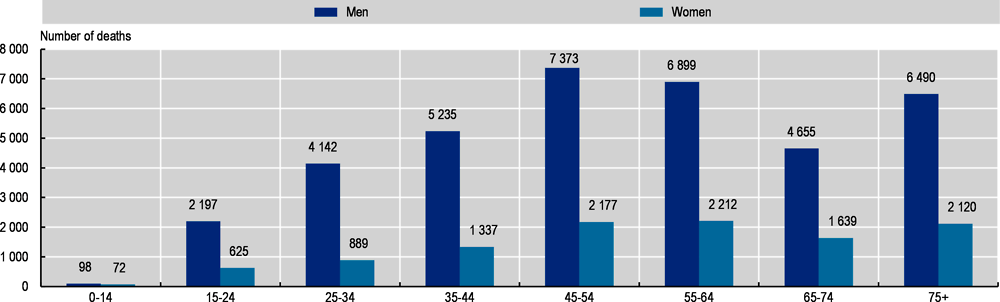

Without effective treatment and support, mental health problems can have a devastating effect on people’s lives, and significantly increase the risk of dying from suicide (OECD/EU, 2018). In 2017, over 48 000 people died of suicide across EU countries. The most frequent number of suicides were amongst men aged 45 and over (Figure 3.21). Gender differences in suicidal behaviour are significant; men represent over three-quarters of suicides in EU countries, though the gender gap is narrower amongst older age groups. In Lithuania, the suicide rate among men was more than five times higher than that for women.

On average, there were 11 deaths by suicide per 100 000 population across EU countries in 2017 (Figure 3.22). Suicide rates were lowest in Cyprus, Greece, Italy and Malta, where there were fewer than six suicides per 100 000 population in 2017. Lithuania and Slovenia had the highest suicide rate, with 26 and 20 deaths per 100 000 population, respectively.

Suicide rates have decreased in almost all EU countries, falling by 50% between 2000 and 2017. In some countries, the declines have been significant, including in Hungary, the Slovak Republic and Bulgaria, where deaths by suicide have fallen by more than 50%.

Effective approaches to reducing death by suicide include good access to support and mental health care; suicide prevention training for gatekeepers such as health workers and community leaders; reducing access to lethal means such as firearms and pharmaceuticals; responsible media reporting around suicide; and awareness and anti-stigma campaigns. Some EU countries include suicide prevention as part of their broader mental health policies, while others such as Ireland, Luxembourg, the Netherlands and Switzerland have specific suicide reduction plans.

In the Netherlands, the National Agenda for Suicide Prevention 2018-21 takes a multi-pronged approach, including suicide prevention training for General Practitioners and hospital nurses, improving aftercare following a suicide attempt, and training for persons in contact with identified high-risk groups such as agencies working with debt relief, unemployment support workers, and the police. In France, suicide prevention includes training for peer workers and General Practitioners, as well as a specific suicide reattempt prevention programme.

In Ireland, too, the National Strategy to Reduce Suicide 2015-20 focuses attention on groups at particular risk of suicide, and persons who have already presented with suicide attempts. Ireland focuses on strengthening pathways to services for people vulnerable to suicidal behaviour, and improving the capacity of community-based organisations to provide appropriate information around suicide and recognising risks.

In Switzerland, the suicide rate has decreased by 64% since 2000. While rates of ‘assisted suicide’ are rising, mainly in older people, since 2009 assisted suicides have been excluded from overall suicide data, explaining the sharp decline the year the reporting changed. Switzerland has taken steps to reduce deaths by suicide, including a suicide prevention action plan in 2016 that focused on providing fast access to mental health support, reducing stigma around suicide, and raising awareness of suicide risks.

The prevalence of psychological distress symptoms is based on EU survey on Statistics on Income and Living Conditions (EU-SILC). Questions are based on the module on mental health of the SF-36 questionnaire. The prevalence is calculated from responses to five items such as “Have you been very nervous over the past four weeks?” on a 5-point scale (0-4) ranging from ‘at no time’ to ‘all of the time’. The scores can amount to a maximum score of 20, which is then multiplied by 5 to get a maximum of 100. Someone is considered with psychological distress symptoms if they scored above 50. Items refer to feeling nervous, feeling down, feeling calm, feeling down-hearted or depressed, and feeling happy. Prevalence is weighted by population size.

Suicide data come from the Eurostat Database. The registration of suicide is a complex procedure, affected by factors such as how intent is ascertained, who is responsible for completing the death certificate, and cultural dimensions including stigma. Caution is therefore needed when comparing rates between countries.

References

OECD (2015), Recommendation of the Council on Integrated Mental Health, Skills and Work Policy, https://legalinstruments.oecd.org/en/instruments/OECD-LEGAL-0420.

OECD/EU (2018), Health at a Glance: Europe 2018: State of Health in the EU Cycle, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/health_glance_eur-2018-en.