Chapter 1. Assessment and recommendations

This chapter describes the main characteristics of vocational education and training (VET) and recent policy developments in Sweden. It assesses the strengths of the system, the challenges that remain, and summarises suggestions for policy advanced in later chapters of the report. Subsequent chapters examine different issues by presenting the topic, describing the challenge, advancing policy suggestions, providing arguments for the proposed policy solutions and discussing how these policy solutions could be implemented.

The statistical data for Israel are supplied by and under the responsibility of the relevant Israeli authorities. The use of such data by the OECD is without prejudice to the status of the Golan Heights, East Jerusalem and Israeli settlements in the West Bank under the terms of international law.

Introduction: Background

Sweden has made great strides in the development of its VET system

In the last decade, Sweden has introduced a wide range of reforms in its upper-secondary vocational education and training (VET) system. It has enhanced work-based learning by introducing stricter requirements on the provision of work placements by schools in vocational programmes and the role of the social partners by creating national architecture in which social partners can work with government to oversee the vocational education system. It has also established an apprenticeship system. Incentives are in place to encourage local engagement with the social partners, and more recently, new incentives have been introduced to encourage employers to pay apprentice wages, and to train workplace trainers so that they are adequately prepared to mentor workplace trainees and apprentices. A new and innovative system of post-secondary higher vocational education has continued to grow and develop. All these developments are positive.

But other challenges have emerged

The proportion of young people entering upper secondary VET has been falling. While apprenticeship has been launched the number of young people entering apprenticeship remains very small. Compared with many other countries, upper secondary VET schools, in terms of students enrolled, remain too small to deliver specialised vocational training. Despite successful national arrangements, local engagement of the social partners in the VET system remains patchy. The Swedish VET system also faces new challenges in responding to an increasingly diverse cohort of learners. The aim of this review, conducted a decade after a previous OECD review of upper-secondary VET in Sweden, and five years after a short exercise to look at post-secondary VET, is to address these challenges, and make proposals for how Sweden can advance further in the development of its VET system. Conclusions and recommendations from the two previous OECD studies are reported in Box 1.1.

This study draws on the extensive experience of the OECD in the area of VET

This is one of a series of OECD studies of VET and apprenticeship systems in more than 30 countries. As a contribution to this work, a background report was prepared on behalf of the Swedish authorities (Ministry of Education, 2018[1]). The OECD team undertook two missions to Sweden in March 2018 and in June 2018, and met and held discussions with a wide range of stakeholders, including the Ministry of Education which sponsored this exercise and other interested ministries, employers and trade union groups, and made visits to several vocational upper-secondary schools. This review draws extensively on these discussions.

This review looks primarily at upper-secondary VET

The review’s main focus is on upper-secondary VET, both for young people or adults returning to education. Post-secondary VET is addressed in Chapter 5 in the context of transition from upper-secondary VET to higher level education. Following this introductory chapter, each chapter will start with an introduction providing contextual information and comparing Sweden with other countries in relation to the chapter topic. Each chapter will then describe a policy challenge, followed by policy options. Finally, each chapter offers arguments supporting the proposed policy options and explores how these options could be implemented in Sweden.

The Learning for Jobs 2008 report recommended that Sweden:

-

Maintain comprehensive upper-secondary education, and not to differentiate vocational education and training (VET) programmes from those preparing for higher education.

-

Develop stronger mechanism through which the social partners could convey labour market requirements to VET providers, and creation of a national commission for VET composed of different government ministries and the social partners.

-

Scrutinise the regulations to ensure that public and independent schools experience the same regulatory regime to ensure the competition between schools is fair.

-

Publish information on the labour market outcomes of VET on a school and programme basis.

-

Introduce the mandatory and quality assured 15-week work placement in upper-secondary VET, and tightening the provision of VET programmes to the availability of work placements – indication of employers skills needs.

-

Develop an apprenticeship system to complement school based VET.

The 2013 OECD commentary on post-secondary VET :

-

Praised the Swedish system of higher vocational education (HVET) for being a highly innovative, and in particular for its capacity to encourage partnership between employers and training providers; for inclusion of quality assured and workplace learning in HVET (2-year programmes); for strong quality assurance arrangements for both higher vocational education and professional bachelor programmes; and for strong data and evaluation culture.

-

Pointed to some challenges, such as limited flexibility in provision for those who might wish to pursue post-secondary VET courses part-time, particularly adults in work; and difficult transition from HVET to university colleges and university programmes.

Source: Kuczera, M. et al. (2008[2]), OECD Reviews of Vocational Education and Training: A Learning for Jobs Review of Sweden 2008, OECD Reviews of Vocational Education and Training, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264113978-en; Kuczera, M. (2013[3]), A Skills beyond School Commentary on Sweden, OECD Reviews of Vocational Education and Training, www.oecd.org/education/skills-beyond-school/ASkillsBeyondSchoolCommentaryOnSweden.pdf.

The labour market in Sweden

Unemployment is low and employers are facing labour shortages

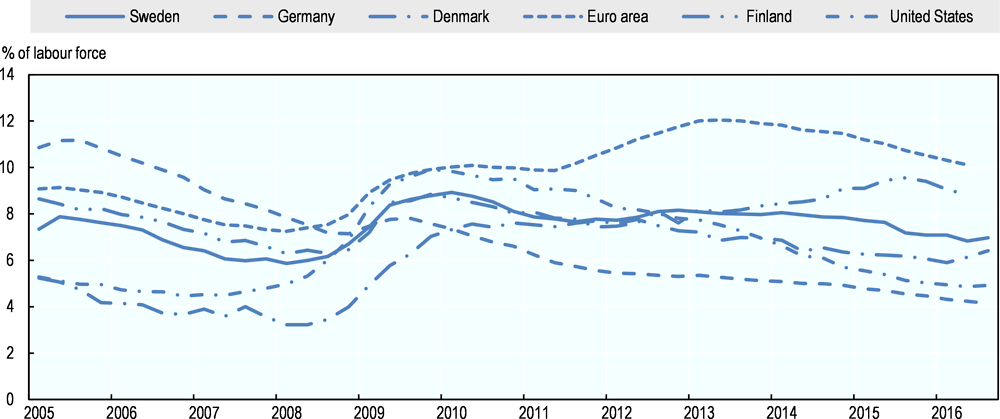

Unemployment has been falling in recent years. In 2016, 7% of the labour force were unemployed in Sweden, below the level of structural unemployment (OECD, 2017[4]). Shortages of skilled labour are appearing in many sectors, such as health, education and technology and in jobs requiring post-secondary and upper-secondary VET (Statistics Sweden (SCB), 2018[5]).

But unemployment in some groups remains high

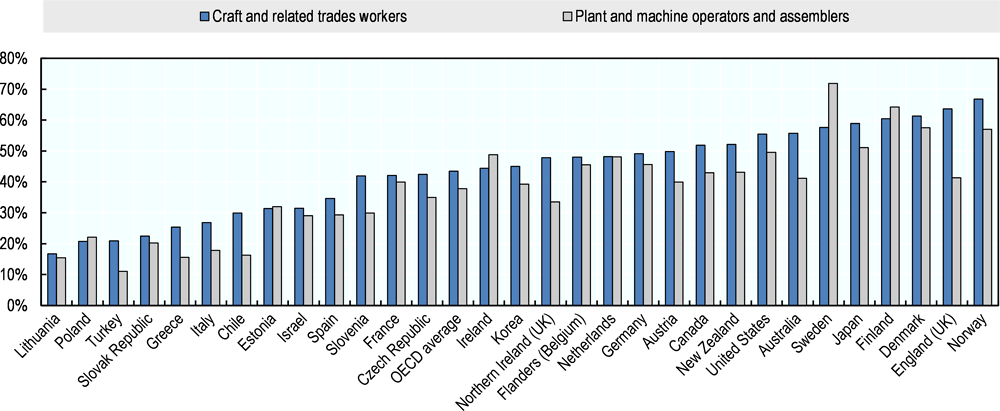

Despite the tightening labour market, unemployment has been rising in vulnerable social groups such as non-European born migrants and those with low educational attainment (OECD, 2017[4]; OECD, 2017[6]). In Sweden, even middle-level jobs requiring no more than upper-secondary education are often skills-intensive, leaving those with low skills or poor Swedish with fewer jobs to choose from. For example, workers in Sweden in semi-skilled occupations (e.g. clerks, service and shop workers, craft and related trade workers, plant and machine operators) are more likely to solve problems, use computers and other technologies than workers in similar jobs in many other countries (Figure 1.2 illustrates the use of computers in middle-skilled jobs). Sweden is responding to this challenge by facilitating access to adult education to those with a low level of education, by building a system of skills recognition allowing migrants to have their skills and knowledge recognised, and by modularisation of VET qualifications.

The VET system in Sweden

A snapshot of the upper-secondary system

At upper-secondary level, students choose between academic and VET pathways

Compulsory education, at primary and lower secondary level, begins at the age of 6 and ends at the age of 16. Students who successfully complete compulsory education can apply for one of the 18 national upper-secondary programmes, which usually last three years. Students who have passing grades in at least 8 compulsory subjects can apply for a national VET programme and those with passing grades in 12 compulsory subjects are eligible for higher education preparatory programmes. The scope of the courses in upper-secondary school is defined by upper-secondary credits, indicating the relative weight of the course in the full programme. All upper-secondary programmes comprise a total of 2 500 upper-secondary credits. All upper-secondary school programmes include the same eight core required subjects but the scope and so the amount of credits associated with the core/foundation subjects differ across vocational and higher education preparatory programmes. In VET programmes foundation subjects encompasses 600 out of 2 500 credit points, and in higher education preparatory programmes 1 100-1 250 out of 2 500. In addition to the foundation subjects, students study programme specific subjects. Academic and vocational programmes are provided within the same institutions and education is given on a full-time basis (Ministry of Education, 2018[1]; Skolverket and ReferNet Sweden, 2016[8]).

At post-secondary level, there are two main paths

Depending on their choice of upper-secondary national programme, students who have completed upper-secondary school with basic eligibility for higher education can apply to universities (universitet), university colleges (högskola) and/or higher vocational education (yrkeshögskola) (Ministry of Education, 2018[1]). Transition to a higher level education is more difficult for students completing upper-secondary VET programmes as they do not acquire an automatic eligibility for higher education upon completion of upper-secondary VET.

Introductory programmes

There are four introductory programmes

Students who do not meet the requirements for entry to upper-secondary National Programmes are admitted to one of four introductory programmes (introduktionsprogram) (Ministry of Education, 2018[1]). These programmes include:1

-

Vocational introduction: includes vocationally-oriented training providing access to the labour market or to Vocational National Programmes.

-

Individual alternative: prepares students for vocational introduction programmes or to the labour market. It should contain compulsory school subjects and may also contain upper-secondary subjects.

-

Programme-oriented option: targets students who missed the requirements for national VET programmes in a few subjects, and it aims to transfer them quickly to a specific national VET programme.

-

Language introduction: provides migrant students with training in Swedish necessary to start on National Programmes or continue other education pathways. Swedish language training can be combined with a range of courses from compulsory and upper-secondary level.

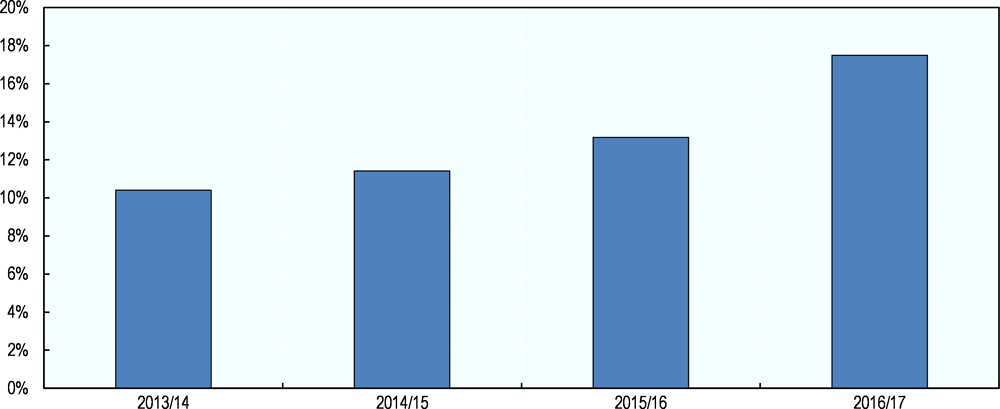

The proportion of students entering introductory programmes has increased

In recent years, the share of upper-secondary students (including those in national and introductory programmes) attending introductory programmes has been increasing and is now over 17% (Figure 1.3).

The introductory programmes cater for different groups with diverse needs

Introductory programmes cater to students with a wide range of needs, including both those who missed the requirements to enter the national upper-secondary programme of their choice by a narrow margin and those who have major weaknesses in their knowledge and skills. The programmes are designed to offer an individualised approach adapted to individual student’s needs. Introductory programmes prepare students for entering National Programmes, for continuing in further education, and for transferring to the labour market. Half of those starting on an introductory programme manage to enter National Programmes within five years (Skolverket, 2017[9]). Currently, more than half of all students in introductory programmes are migrants attending language introduction (this issue is discussed in more detail in Chapter 6 focusing on migrant population).

Upper-secondary VET

Apprenticeship and school-based VET lead to the same qualifications

Out of 18 national upper-secondary programmes 12 are vocational, all offered either as a school-based programme, or as an apprenticeship.2 Programmes in building and construction; electricity and energy; and vehicle and transport enrol the largest share of VET students.

The National Agency for Education (Skolverket) oversees upper-secondary VET

This government agency manages, on behalf of the Ministry of Education, the Swedish school system for youth and adults, including upper-secondary VET. It supports and evaluates the work of municipalities, independent providers and schools. While the ministry determines policy, at operational level the agency defines learning outcomes from education and training, how education and training should be delivered and how schools and students’ performance should be assessed. To this end, it develops a range of documents such as syllabi, national tests, grading criteria, and general guidelines. It also administers government grants. The agency organises support and training programmes for school-leaders and teachers, manages the registration of teachers and hosts the Teachers Disciplinary Board. It also conducts evaluations of VET policies (Skolverket and ReferNet Sweden, 2016[8]).

The Swedish Schools Inspectorate is responsible for supervision and quality assurance

The Swedish Schools Inspectorate, a government agency, contributes to school improvement and development. To this end, it conducts regular supervision of all municipal and independent schools, from pre-school to adult education and assesses applications to run an independent school (The Swedish Schools Inspectorate, 2015[10]).

Upper-secondary VET and academic graduates have not dissimilar outcomes

In 2016, one year after completion of their studies, around 80% of upper-secondary VET graduates were in employment. The level of attachment to the labour market and type of employment varied largely in this group, with only half of the VET graduates having a well-established position on the labour market (Skolverket, 2016[11]). Half of the graduates were in jobs corresponding to their areas of study, a correspondence that was stronger among men than women (Ministry of Education, 2018[1]). If the success of upper-secondary education is measured with either finding a job or continuing in education, performance of VET graduates is similar to those coming from academic programmes. In comparison to graduates from academic paths those graduating from VET are more likely to work and less likely to study, which is consistent with outcomes set up for these two types of programmes. In 2016, 9% of graduates from VET and 8% from academic programmes were NEET (neither employed nor in education or training) one year after graduation (Statistics Sweden (SCB), 2018[5]).

Enrolment in VET has been falling

Enrolment in VET fell until recently. Currently students in VET account for only a third of all youth in national upper-secondary programmes. Chapter 5 explores the reasons of this declining attractiveness of VET paths. Young men, migrants and the children of less educated parents are over-represented in VET programmes. 60% of VET students are men as compared to 47% in academic programmes. 80% are of Swedish background (born in Sweden and with at least one parent born in Sweden), four percentage points more than in academic upper-secondary education. Among VET students, only 34% have parents with post-secondary education, as compared to 64% among students enrolled in academic programmes (Ministry of Education, 2018[1]).

Adult education

Many adults in Sweden participate in different forms of education and training

In Sweden, 66% of adults participate in formal or informal education, 16 percentage points above the OECD average and one of the highest rates among the OECD countries (OECD, 2018[12]). The majority of adult learners who studied at least one year in municipal adult education opted for health and social care courses (Ministry of Education, 2018[1]). In other OECD countries such as Australia, Denmark, Finland, and the Netherlands the overwhelming majority of the cohort returning to upper-secondary education enrol in VET programmes (OECD, 2017[6]).

Municipalities are the main provider of adult education (komvux)

In Sweden, adults who have not completed upper-secondary education have a right to free education and training leading to upper-secondary qualifications and municipalities are obliged to provide it. Education and training in the adult sector may lead to the same qualifications as programmes for youth but is organised in courses rather than as National Programmes. Of all 61 118 students in municipal adult education who completed their studies in 2013, nearly 16% studied more than one year of VET courses, and nearly 10% studied between six months and one year.

Higher VET

Higher VET programmes, by law, must reflect the needs of the labour market

Higher VET (HVET) programmes have developed gradually over the last 15 years to offer mid-level post-secondary vocational qualifications, involving up to two years of study if pursued full time. Local training providers, in collaboration with employers, propose programmes to the National Agency for Higher Vocational Education which may then be funded by the agency for a limited number of programme starts (up to five starts). Upon expiry of one grant period, the education provider is free to apply for another set of programme starts, possibly adjusted to changing labour market needs. To establish a new HVET programme, education providers must secure employers’ involvement. All two-year programmes have to include work placements with employers. Work-based learning is mandatory in courses leading to an advanced higher VET diploma (European Qualifications Framework [EQF] level 6). Programmes leading to a higher VET diploma at EQF level 5 usually include WBL even if its provision is not mandatory.

Most programmes involve two years of full-time studies, but some are as short as six months

A one-year programme (200 credits) yields a Higher Vocational Education Diploma, while a two-year programme (400 credits) yields an Advanced Higher Vocational Education Diploma. Each programme consists of several courses, in accordance with a plan drawn up by the education providers. Students can choose a programme in 15 different fields. 80% of students are in the fields of information and communications technology (ICT), finance, administration and sales, healthcare, construction fields and in technology and manufacturing. A little over half (54%) of the students starting courses in 2017 were women, but the gender mix varies markedly across the different programmes. HVET programmes may also offer Swedish language training, targeted at migrants (representing around 20% of HVET students), and integrated with regular teaching. These programmes and their connections to upper-secondary VET provision are discussed in more detail in Chapter 5. In 2016, 93% of the students were employed one year after graduation. 68% of those employed had a job that fully or to a large extent aligned with the HVET programme attended, and 91% expressed satisfaction with their education.

The National Agency for Higher Vocational Education oversees provision

The National Agency for Higher Vocational Education also has wider responsibilities for HVET, conducting reviews and inspections, collecting and publishing statistical data, and promoting quality improvements.

Overview of policy development: 1990s reforms

Reforms from the 1990s changed the education landscape

In the 1990s, large reforms transformed the whole education system in Sweden. It also had a profound impact on the organisation and delivery of upper-secondary VET programmes to young people and adults. It made VET and academic programmes more similar and allowed VET students to continue to higher education. The reform increased the role of municipalities in the education system, including in upper-secondary VET. Through the reform, municipalities received full employer responsibility for all school staff, the allocation of resources between different parts of the school system, the organisation of schools and adult education, and continuing professional development for staff (Ministry of Education, 2016[13]).

It also introduced a quasi-market in education

The 1990s reforms reinforced student choice and allowed private entities to establish private schools (also called independent schools). The aim of these reforms was to improve efficiency by empowering municipalities in planning and organising upper-secondary VET, increasing the educational offer and giving more choice to students and parents (Skolverket, 2012[14]). While empowerment of schools allowed them to address more effectively individual student needs and local labour market circumstances, competition created some risks. Competition among education providers for students inevitably creates an environment in which it is more challenging to encourage collaborative approaches. This is a particular challenge because of the relatively small size of upper-secondary VET schools in Sweden, relative to international comparators. This issue is pursued in Chapter 2.

Overview of policy development: 2010s reforms

More vocational content was added to VET programmes and apprenticeship were established

In 2011, a further reform introduced more vocational content into upper-secondary VET programmes and removed automatic eligibility for admission to higher education from VET programmes. Students opting for VET were given an opportunity of following an apprenticeship path3 (Ministry of Education, 2018[1]). As a result, students in vocational programmes can attend a mainly ‘school-based education’ or ‘apprenticeship education’. The content and diploma goals of the two paths are the same. Work placement of at least 15 weeks was reinforced in school-based VET programmes. In apprenticeship, students should spend at least half of their learning time in the work place. Chapter 3 discusses how Sweden could further develop and capitalise on work placement in school-based provision and apprenticeship programmes while building on what already has been achieved.

It reinforced the involvement of social partners

Sweden created a framework for social partner involvement at the national and local level. At the national level, National Programme Councils advise the National Agency for Education on specific VET programmes while at the local level, partnerships with social partners are established at the school level. Chapter 4 describes in more detail the existing arrangements and provides policy options for how social partners’ engagement in VET could be reinforced.

Recent developments

Better quality work-based learning is promoted

In recent years, Sweden has launched many initiatives. To promote good quality work-based learning, the National Agency for Education has developed measures to improve the preparedness of trainers in companies, and the competences of schools to organise and improve the quality of WBL. New legislation encourages employers to pay wages to apprentices (at the moment this is rare). Chapter 3 looks at how apprenticeship might be further developed, building on these initiatives by government.

Sweden invests in adult education

The policy objective is to re-skill and up-skill the unemployed and to allow adults to complete upper-secondary education. Vocational education and training (VET) for adults is an important element of this lifelong learning strategy. But currently, provision of adult VET is fragmented. Many municipalities (the main providers of adult education) are too small to offer a variety of courses. To increase and diversify the range of provision, the government provides grants for adult education conditional on at least three municipalities working together. The collaboration should also include other providers of adult education and training such as the Public Employment Service (PES) and reflects skills needs in the region. One of initiatives is the National Delegation for the Employment of Young People and Newly Arrived Migrants (DUA), which promotes co-operation between individual municipalities and the PES as well as other stakeholders through Local Job Track.4

Sweden introduced partial qualifications

In December 2017, Sweden introduced Vocational Packages (yrkespaket) in adult upper-secondary VET and introductory programmes. These are clusters of courses, leading to a partial qualification that can be a stepping-stone towards a full qualification. In February 2018 there were 60 Vocational Packages across a range of fields. The innovation has raised some concerns. Social partners in some sectors are reluctant to accept partial qualifications for young people. They worry that entry of young people with limited work experience and poor academic performance into the labour market may decrease the overall skills levels among their employees. Sectors facing large skills shortages are, naturally, more in favour of Vocational Packages (Ministry of Education, 2018[1]). This issue is discussed in more detail in Chapter 6 in the context of migrants and VET.

Measures addressing fragmentation have been introduced

Fragmentation and insufficient collaboration between various stakeholders represent a challenge not only in adult VET but also in VET provision targeting youth (see Chapter 2). The Swedish government has established a Commission of Inquiry investigating the issue of fragmentation. Branch schools – currently in a pilot phase – allow provision of some elements of VET to be concentrated in fewer schools.

New reform measures aim to help newly arrived adults transition to education and labour market smoothly

While some of these targeted and universal measures are new, others were based on previously implemented measures.

-

Education and Training Obligation (since January 2018): All newly arrived immigrants who benefit from the Public Employment Service’s Introduction Programme, and who have not attained compulsory education can be referred to, apply for, and undergo education and training.

-

Education Entry Grant: This grant aims to make it easier for low-educated adults to study at basic or upper-secondary level. The take up of the grant is lower than expected and the Swedish government plans to review it.

-

Vocational Introduction Employments (Yrkesintroduktionsanställning): These are based on collective agreements targeting recently arrived immigrants and other vulnerable groups (15-24 years-old). Work is combined with education with the financial support paid by the Public Employment Services. The education component (no wage entitlement) is restricted to a maximum of 25% of working hours.

-

Introduction Jobs:5 The wage subsidy will be capped at a gross salary of SEK 20 000 (approximately EUR 2 000 per month), and the limit will be 80%. Uniform supervisor support is introduced.

-

Entry Agreements: These enable newly arrived immigrants and the long-term unemployed to gain employment from an employer who participates in entry agreements. The employee is to be given the possibility of attending Swedish for Immigrants (SFI) and other short-term training programmes. An employer’s total payroll expense for a position under entry agreements amounts to SEK 8 400 (approximately EUR 800) per month in 2019. In addition, the employee will receive a tax-free, individual state benefit amounting to at most SEK 9 870 per month in 2019.

Strengths of the VET system in Sweden

Sweden has a strong evaluation culture ensuring that policy is based on solid evidence

Sweden has rich sources of data, including a national register, which identifies individuals on the basis of personal identification numbers. These are linked to a range of administrative data sets, including those on education and employment. New measures are typically introduced as pilot initiatives, and if successful, scaled up. For example, the apprenticeship path operated on a trial basis initially before being introduced more widely (Ministry of Education, 2018[1]). Areas where significant challenges are identified are examined by commissions of inquiry. For example, in the past a commission was set up to look at career guidance provision (Regeringskansliet, 2018[15]). Currently a commission of inquiry is focusing on the fragmentation of the VET system and explores whether, and how, regional co-ordination among VET stakeholders should be encouraged and enabled.

Upper-secondary VET is provided in a flexible way and allows individuals to build on their previous knowledge and experience

Specific VET courses lead to credits, not related to study time but to the goals of the course. Thanks to a modularised structure, students can transfer credits across programmes and types of education. For example, a young person who has not acquired all the credits necessary to complete upper-secondary education can take the missing courses in the context of adult education. In upper-secondary VET, school-based VET and apprenticeships lead to the same qualifications. Students who wish to obtain a VET qualification can therefore choose a path that suits them best. While it is too early to evaluate Vocational Packages, potentially they may also promote skills acquisition among those with the lowest skills levels and facilitate completion of upper-secondary education in this population.

Higher vocational education and training has been expanding

Advanced vocational education (the precursor of HVET) was launched in 2002 after a pilot phase that started already in 1996. At this point in time, a set of post-secondary vocational programmes outside of university were provided by diverse public and private institutions subject to fragmented regulation. The government judged that these diverse arrangements needed to be drawn together under the heading of HVET to ensure quality, simplify regulation, improve the information available to students and increase labour market relevance. Since then, enrolment in HVET has been increasing fast and is expected to grow further from 50 000 today to 70 000 students in 2022 (Ministry of Education, 2018[1]). HVET programmes are designed in close collaboration with employers and should genuinely match the demand for relevant skills from the labour market. The growing enrolment rate shows that these programmes are in demand both among students and employers.

Sweden has strengthened links between VET and the labour market

The first OECD review of VET in Sweden argued that the VET system in Sweden was the largely separated from the world of work (Kuczera et al., 2008[2]). At that time social partners’ involvement in VET was not systematic. Since then, series of reforms have brought the worlds of VET and of work closer together. The creation of a national framework for social partners’ engagements through National Programme Councils secured their systematic involvement in VET and work placement became mandatory in all VET programmes. These are considerable achievements. Building social partner engagement in VET is often very challenging.

Sweden is committed to help prepare young migrants to progress in education

Both asylum seeker and refugee children up to the age 18 have the right to attend school in Sweden up to upper secondary level,6 and schools are required to attempt to enrol newly arrived children within one month of their arrival. In addition, the Swedish school system has implemented measures designed to ensure that these children benefit from, and succeed in, their classes (Fratzke, 2017[16]).

For example, newly arrived students have the legal right to tuition in their native language. Although the capacity of schools to meet existing needs varies considerably in practice, almost half of foreign-born students have benefited recently from native-language tuition. Short of tutoring, newly arrived students may receive study guidance in their native language before, during or after lessons and or in special language workshops (Berglund, 2017[17]).

In order to support municipalities in providing newly arrived learners with appropriate education, towards the end of 2015 the National Agency for Education allocated SEK 200 million (approximately EUR 20 million) to 46 municipalities in which at least 10% of all the children in the municipality were newly arrived migrants. Then, in January 2017, a further SEK 2 138 million (approximately EUR 210 million) was allocated (2017-25) to support the capacity of public and independent schools (friskolor) to provide newly arrived students with education of high quality. The most relevant areas of investment are reportedly language learning, study counsellors, teachers’ didactical skills, and proper organisation (Bunar, 2017[18]).

Summary of policy options

Chapter 2: Strengthening collaboration and consolidation of the VET provision

Swedish VET is relatively decentralised and market driven with public and private providers competing for students. Chapter 2 shows that in this context, schools and school owners have week incentives to collaborate in planning the provision of VET and that VET provision for youth is fragmented. In international comparison, Swedish upper-secondary schools offering VET programmes cater to few VET students. The chapter argues that to better match VET provision to the labour market needs and to make the system more effective, Sweden may introduce measures that foster collaboration across schools and encourage concentration of provision in fewer institutions. The proposed measures should span the youth and adult sector and apply to all VET schools, including public and independent VET schools.

Policy options include:

-

As a first step, collaboration between VET schools should be encouraged. Collaboration may cover diverse options, including sharing facilities and teachers, helping with the work-based learning component of programmes, offering specialist training to students from other schools lacking relevant teaching expertise, collective engagement with the social partners and other matters. Collaboration efforts may build on some existing initiatives, such as branch schools.

-

To improve the match between the provision of VET and labour market needs, social partners should be part of this process and be able to convey their needs. Currently, provision is heavily driven by students’ preferences and schools competing for students, and less so by labour market needs.

-

As a second step, in programmes where economies of scale can be reached VET schools should be merged to create larger institutions, drawing on the positive experience of many other countries that have consolidated their VET school systems. In practice it would mean that VET programmes would be offered in fewer schools and the schools with VET provision would enrol a larger number of VET students. Consolidation would not prevent schools from offering both VET and Higher Education Preparatory Programmes.

-

Funding incentives may be necessary to encourage and reward collaboration, and sometimes mergers, when the effect is to improve the quality of provision.

-

These policy options, as well as options discussed in other chapters of this report, should apply to all VET schools, including schools run by private and public providers. Including independently run schools into this process may be a challenge. But excluding them would result in different arrangements for different providers, which would contribute to unfair competition and would discourage collaboration. This would be highly undesirable. The proposed policy options should apply to VET for youth and adults, so as different provisions complement each other. Such co-ordination of provision would allow to offer a more diverse range of courses and programmes and better address individual and local labour market needs. This is consistent with the mandate of the National Commission of Inquiry on dimensioning of upper-secondary education that focuses both on the upper-secondary system for youth and adult education.

Chapter 3: Enhancing work-based learning

Chapter 3 focuses on work-based learning (WBL) in apprenticeship programmes and WBL as a component of the upper-secondary VET programmes provided mainly in schools. In recent years, Sweden has successfully increased the provision of WBL in VET. Chapter 3 shows that Sweden could further improve the quality of workplace experience and increase the associated benefits by vesting social partners with more responsibility over WBL. It argues that by giving more prominence to WBL in planning VET provision, Sweden could tie VET delivery more closely to employer needs. Finally, it discusses how to increase the attractiveness of apprenticeships to employers and students.

Policy options include:

-

To address quality challenges, WBL tasks currently assumed by individual VET teachers could be usefully shared with and supported by other bodies, such as reinforced local bodies where social partners are represented, as argued in Chapter 2 and Chapter 4.

-

While retaining an important role for individual VET teachers, social partners would therefore be more involved in the organisation and management of WBL than they are now. Within this framework, the social partners, working collectively and in co-ordination with VET schools, might offer systematic support to individual companies with the provision of WBL, certification of companies offering WBL according to criteria agreed with social partners, and provide regular guidance and feedback to schools and National Programme Councils on the content of WBL and methods of assessment of practical skills.

-

The responsibility of VET schools and social partners for WBL should be clearly defined and both parties should be kept accountable for delivery of WBL. The school inspectorate and social partners may share the responsibility for quality assurance of WBL in VET programmes.

-

Employer willingness to offer WBL could be used more fully to steer students towards occupations in demand in the labour market, and to adjust school provision. This should improve the match between the mix of training provision and skills in demand among employers. To facilitate the match, a website platform may be created where companies and schools announce their needs in terms of WBL.

-

Over recent years, the involvement of social partners in formal VET in Sweden has been gradually increasing. Apprenticeship has been growing, as have the numbers of apprentices receiving wages, but numbers remain small. Building on these trends, employers in Sweden should:

-

Be allowed to select their apprentices (as in other countries).

-

Be granted a stronger influence over the content and modes of delivery of WBL in apprenticeship.

-

Be more strongly encouraged to pay apprentices a wage.

-

-

Wages for apprentices and stricter regulation on WBL quality would increase the cost of apprenticeship provision for employers. Financial and/or non-financial incentives may therefore also be necessary to maintain the attractiveness of the scheme to employers. Current grant support to employers providing apprenticeships should be evaluated and if necessary adjusted.

-

Changes in apprenticeship schemes should be designed to increase the attractiveness of apprenticeship to employers. Governments may help employers provide good quality training and meet requirements for WBL, for example by providing a framework for co-operation across companies.

Chapter 4: Empowering social partners

Sweden has successfully built social partners’ engagement in VET at the national level, but social partners’ involvement at the local level varies affecting the quality of provided education and training. The chapter argues that Sweden may create a framework for systematic social partners’ involvement at the local level. The chapter discusses college initiatives that are led by the social partners and drive local provision towards specific skills requirements, often in response to labour shortages. It argues that Sweden can strengthen social partners’ involvement drawing on this positive experience.

Policy options include:

-

Building on existing local consultation arrangements, and the successful experience with colleges, Sweden could establish a more systematic institutional framework to engage the social partners at local level. This would promote collaboration between different stakeholders, and reinforce links between national and local bodies in which social partners are represented. A model inspired by the college initiative, in which programmes and institutions collaborate and meet the quality requirements of the social partners, could be encouraged.

-

This proposition is linked to policy options advanced in other chapters of this report. Chapter 2 proposed the consolidation of VET provision in fewer but larger VET schools, facilitating social partner engagement as social partners would not have to engage with so many small institutions.

-

Drawing on the Danish experience, local social partner organisations may serve as a link between local and national levels, ensuring that National Programme Councils are fully apprised of local circumstances and interests, and that local approaches take full account of national development.

-

Stronger local engagement of the social partners would facilitate an enhanced role for the social partners in the quality assurance of local VET provision. This role could involve ensuring that national VET programmes are taught and configured so as to meet local labour market requirements, supporting the provision of work placements and apprenticeships, and quality assuring the work placements that are delivered. This might be underpinned by making school evaluations give credit to schools for facilitating such local engagement of the social partners, and the quality assurance which might follow.

Chapter 5: Increasing the attractiveness of VET

In Sweden, enrolment in upper-secondary VET has been falling. Chapter 5 argues that clear and workable pathways from upper-secondary VET to post-secondary education and training would increase the attractiveness of VET to students. To this end, Sweden may reinstall academic content providing eligibility for higher education in the routine coursework in VET programmes. The chapter also discusses pathways of progression from upper-secondary VET to post-secondary professional programmes and argues that these post-secondary programmes should be accessible and attractive to adults returning to education.

Policy options include:

-

A strong VET system needs to be attractive to a diversity of students, including those with stronger academic performance as well as those who are less academically oriented. The evidence suggests that the declining popularity of VET in Sweden may be related to the weak pathways from VET to higher education, and VET being perceived as an option for low performing students.

-

To reverse this trend Sweden may reinstall academic content in the routine coursework in VET programmes,7 but allow students who are less interested in academic subjects to opt out of them. Currently, all upper-secondary programmes including school-based VET and apprenticeships last three years. Combining demanding VET and academic coursework may therefore require an extension of the programme duration leading to a double qualification. The Technology Programme that can be topped up with a fourth year leading to an ‘upper-secondary’ engineering degree provides an example of a programme leading to both vocational and academic qualifications.

-

Links between upper-secondary VET and the post-secondary level could usefully be strengthened and entry points from upper-secondary VET to post-secondary education diversified. For example, individuals may receive extra credits in the admission process if they bring with them the relevant work experience. Stronger and more diverse progression pathways between upper-secondary and post-secondary VET would require co-ordinated provision and co-operation among upper-secondary and post-secondary providers. Post-secondary institutions, including HVET institutions and/or university colleges, should be part of the proposed regional co-operation scheme discussed in Chapter 1.

-

Post-secondary VET provision should be available to adults who wish to upgrade their competences. To attract working adults, programmes should be provided in a flexible way allowing for a combination of work and study. (Currently, most post-secondary VET programmes are full time).

Chapter 6: Unlocking the potential of migrants through VET in Sweden

Sweden is experiencing shortages of vocational upper-secondary graduates and this is expected to continue. In this context, the recent increase in humanitarian migrants presents a set of opportunities, but these can only be fully realised if Sweden can address associated challenges. Sweden already has measures supporting entry of young humanitarian migrants into vocational programmes and the labour market such as introductory programmes and, in particular, the Language Introduction Programme, which is explicitly designed for newly arrived students. However, many newly arrived students in the Language Introduction Programme experience difficulty in transitioning to a national vocational programme, exhibiting relatively low transition rates compared to other introductory programmes and to those in other countries.

As a means to address barriers preventing the success of such learners at risk of poor outcomes, Sweden recently introduced Vocational Packages into the introductory programmes. While Vocational Packages are an attractive alternative for newly arrived students, there are potential risks in introducing the possibility of obtaining partial qualifications within introductory programmes. Vocational Packages may prevent young people from considering occupations that are difficult to be modularised into shorter training programmes, resulting in young people ultimately foregoing the opportunities of building long-term employability. The introduction of Vocational Packages within introductory programmes may unintendedly provide an early exit from the initial education system for young people who otherwise show significant potential. Social partners in some sectors are concerned that young people may move into the labour force with limited work experience and academic proficiency.

For humanitarian migrants, transitions between educational institutions or programmes unfortunately present opportunities to leave or drop out of the education system. While Sweden has a strong and well-functioning adult education system, such discontinuity is a matter for concern. For young people without an upper-secondary qualification, the transition to upper-secondary adult education is not automatic.

Policy options include:

-

The policy priority should continue to be that young people, including humanitarian migrants, attain full upper-secondary qualifications. Vocational Packages should be primarily regarded as an entry point to full VET, while ensuring that partial qualifications are well integrated into the qualifications system. This can be implemented by actively providing feasible and attractive opportunities to continue in VET after Vocational Packages through building seamless VET pathways, by strengthening the co-operation between upper secondary schools and municipal adult education, and by strengthening individual assessment, personalised approaches and career guidance.

-

Sweden should continue to address barriers preventing newly-arrived young migrants from accessing VET, given that newly arrived learners, in particular those who arrive in Sweden when they are in their late-teens, face extra barriers when entering into a national vocational programme. With more flexible entry requirements, more young people would enter into and complete national vocational programmes. For those who missed the chance to obtain upper-secondary qualifications within a national programme, adult education remains essential. Sweden should continue to develop and adjust a range of adult VET provision and supporting measures to better suit those students who have not attained upper-secondary qualifications and overcome institutional issues in the transition to upper-secondary adult education, including information transfer between education institutions.

References

[17] Berglund, J. (2017), Education Policy – A Swedish Success Story? Integration of Newly Arrived Students Into the Swedish School System, International Policy Analysis, Berlin, http://library.fes.de/pdf-files/id/ipa/13259.pdf.

[18] Bunar, N. (2017), Migration and Education in Sweden: Integration of Migrants in the Swedish School Education and Higher Education Systems. NESET II Ad Hoc Question No. 3/2017, NESET II, http://nesetweb.eu/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/Migration-and-Education-in-Sweden.pdf.

[16] Fratzke, S. (2017), Weathering Crisis, Forging Ahead: Swedish Asylum and Integration Policy, Migration Policy Institute, Washington DC, https://www.migrationpolicy.org/sites/default/files/publications/TCM-Asylum-Sweden-FINAL.pdf.

[3] Kuczera, M. (2013), A Skills beyond School Commentary on Sweden, OECD Reviews of Vocational Education and Training, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://www.oecd.org/education/skills-beyond-school/ASkillsBeyondSchoolCommentaryOnSweden.pdf.

[7] Kuczera, M., T. Bastianic and S. Field (2018), Apprenticeship and Vocational Education and Training in Israel, OECD Reviews of Vocational Education and Training, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264302051-en.

[2] Kuczera, M. et al. (2008), OECD Reviews of Vocational Education and Training: A Learning for Jobs Review of Sweden 2008, OECD Reviews of Vocational Education and Training, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264113978-en.

[1] Ministry of Education (2018), Review of VET in Sweden. Background Report.

[13] Ministry of Education (2016), OECD Review of Policies to Improve the Effectiveness of Resource Use in Schools (School Resources Review). Country Background Report: Sweden, http://www.oecd.org/education/school/CBR_OECD_SRR_SE-FINAL.pdf.

[12] OECD (2018), Education at a Glance 2018: OECD Indicators, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/eag-2018-en.

[6] OECD (2017), Education at a Glance 2017. OECD Indicators, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/eag-2017-en.

[4] OECD (2017), OECD Economic Surveys: Sweden 2017, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/eco_surveys-swe-2017-en.

[15] Regeringskansliet (2018), En utvecklad studie- och yrkesvägledning, (A Developed Study of Career Guidance), https://www.regeringen.se/rattsliga-dokument/kommittedirektiv/2017/11/dir.-2017116/ (accessed on 1 December 2018).

[9] Skolverket (2017), “Accounting for government assignments Recognition of the mission on monitoring of the secondary school in 2017”, http://www.skolverket.se.

[11] Skolverket (2016), Sök statistik om förskola, skola och vuxenutbildning. Etableringsstatus 1 år efter avslutade gymnasiestudier läsåret 2014/15 (XLSX) Tabell 2, https://www.skolverket.se/skolutveckling/statistik/sok-statistik-om-forskola-skola-och-vuxenutbildning?sok=SokC&verkform=Gymnasieskolan&omrade=Efter%20gymnasieskolan&lasar=2016 (accessed on 5 December 2018).

[14] Skolverket (2012), “Mapping the School Market Synthesis of the Swedish National Agency for Education’s school market projects SKOLVERKETS AKTUELLA ANALYSER 2012”, https://www.skolverket.se/om-skolverket/publikationer/visa-enskild-publikation?_xurl_=http%3A%2F%2Fwww5.skolverket.se%2Fwtpub%2Fws%2Fskolbok%2Fwpubext%2Ftrycksak%2FBlob%2Fpdf2946.pdf%3Fk%3D2946 (accessed on 4 June 2018).

[8] Skolverket and ReferNet Sweden (2016), Vocational Education and Training in Europe - Sweden, Cedefop ReferNet, Sweden, https://cumulus.cedefop.europa.eu/files/vetelib/2016/2016_CR_SE.pdf.

[5] Statistics Sweden (SCB) (2018), “Increased shortage of job seekers with upper secondary education”, https://www.scb.se/en/finding-statistics/statistics-by-subject-area/education-and-research/analysis-trends-and-forecasts-in-education-and-the-labour-market/labour-market-tendency-survey/pong/statistical-news/labour-market-tendency-survey-2017/ (accessed on 17 October 2018).

[10] The Swedish Schools Inspectorate (2015), The Swedish Schools Inspectorate for International Audiences, https://www.skolinspektionen.se/globalassets/0-si/09-sprak/the-swedish-schools-inspectorate.pdf.

Notes

← 1. The Swedish Parliament reformed the introductory programmes in 2018. The resulting changes will be introduced in the school year 2019/2020. This report describes the introductory programmes as amended by the Parliament in 2018.

← 2. Students who complete the three-year Technology Programme (TE) can also opt for a fourth vocational oriented year leading to a so-called upper-secondary engineering degree. In 2016/17 there were 527 students in the fourth year TE programme.

← 3. An apprenticeship path had been operating on a trial basis since 2008.

← 4. DUA has a mandate to increase dialogue between schools, employers, municipalities, public employment services (PES) and social partners to the benefit of refugees and asylum workers. DUA aims to consolidate and co-ordinate existing measures (e.g. joint skills assessment) from both PES and municipalities and build local agreements with some compulsory elements (Local Job Track).

← 5. This brings about the disappearance of former types of aid: Step-in Jobs, Special Employment Support, Enhanced Special Employment Support, Trainee Jobs Welfare and Trainee Jobs Shortage.

← 6. In order to have the right to attend upper-secondary school, asylum seekers must join the school system before they turn eighteen.

← 7. A Bill was presented to the Parliament in the second quarter of 2018 with proposals that all VET-programmes should by default include courses necessary to obtain basic eligibility to higher education. The proposal included an opt-out solution. The Bill was rejected by the Parliament (www.regeringen.se/495397/contentassets/5bd6e1343c8f403785b394ec275d7073/okade-mojligheter-till-grundlaggande-prop.-201718.184.pdf).