Chapter 3. Building a culture of integrity in the public sector in Argentina

This chapter provides an overview of the strengths and weaknesses of the public ethics framework in Argentina. In particular it recommends addressing the current fragmentation of the public ethics framework by harmonising the different laws and regulations, developing a clear process for managing conflict of interest, updating and streamlining the Code of Ethics and strengthening efforts to build awareness of integrity in the public sector. Further efforts are also needed to reinforce merit in the public sector and to build and open and trusting environment to encourage public officials to raise concerns and report corruption.

3.1. Introduction

Ensuring a public service based on integrity requires approaches that go beyond laws and regulations. Public servants need to be guided towards integrity by defining common values and concrete standards of conduct and implementing them. Ethical norms and values transcend from mere words on paper through socialisation and communication which help public servants to personalise and adopt these. A common understanding is developed of what kind of behaviour public employees are expected to observe in their daily tasks, especially when faced with ethical dilemmas or conflict-of-interest situations which all public officials will encounter at some point in their career.

The building blocks for cultivating a culture of integrity in the public sector according to the OECD Recommendation of the Council on Public Integrity are (OECD, 2017[1]):

-

setting clear integrity standards and procedures,

-

investing in integrity leadership,

-

promoting a professional public sector that is dedicated to the public interest,

-

communicating and raising awareness of the standards and values, and

-

ensuring an open organisational culture and clear and transparent sanctions in cases of misconduct.

In addition, integrity measures are most effective when they are mainstreamed, into general public management policies and practices, such as human resource management and internal control (see Chapter 5), and when they are equipped with sufficient organisational, financial, and personnel resources and capacities. Translating the letter of the standards into effective implementation often proves to be the most challenging part of the process to move from an integrity framework to a culture of integrity in the public sector.

3.2. Building a strong normative framework for public ethics and conflict of interest by reforming the Public Ethics Law

Ethics laws or codes of conduct serve as the backbone to ensuring integrity in the public service. They can act as reference point for public servants regulating ethical norms and principles and conflict of interest. In Argentina, the current legal framework setting the standards of conduct and values expected from public officials is the Public Ethics Law (Ley 25.188 de Ética en el Ejercicio de la Función Pública). It is complemented by other regulations, such as the Code of Ethics (Table 3.1).

The Anti-corruption Office (Oficina Anticorrupción, or OA) is the responsible authority for implementing the Public Ethics Law in the executive branch, while the Supreme Court is responsible in the Judiciary, however only as far as financial and interest disclosures are concerned. Neither the judiciary nor the legislative have designated a specific authority to enforce the law. The mandate provided to the OA, clearly defines the OA as the lead entity for developing, promoting and implementing all regulations, policies and activities related to the promotion of ethics in the public administration and the management of conflict-of-interest situations.

The Public Ethics Law establishes a set of duties, prohibitions and disqualifying factors (incompatibilidades) to be applied, without exception, to all those performing public functions at all levels and ranks in all three branches, be it on a permanent or temporary basis, as a result of the popular vote, direct appointment, competition, or any other legal means.

3.2.1. Inconsistencies between the various legislations on integrity could be overcome during the current reform process of the Public Ethics Law

The public ethics framework in Argentina is scattered across various instruments (Table 3.1). In particular for the executive branch, the ethics law is complemented by Law 25.164, the National Public Employment Framework, and the Decree 41/99, the Code of Ethics. The National Public Employment Framework sets out the duties (Article 23) and prohibitions (Article 24). While some of these overlap with the regulations in the Public Ethics Law, they are formulated differently, diminishing clarity of what is allowed. In addition, the prohibitions of the National Public Employment Framework reach beyond the disqualifying factors in the Public Ethics Law. For example, Article 24b prohibits public officials to direct, manage, advise, sponsor, represent or provide service to persons which manage or exploit state concessions, administrative privileges or are suppliers or contractors of the state. In comparison, the Public Ethics Law’s prohibition only refers to providing services to anyone who manages or exploits state concessions and suppliers. The broader scope of the National Public Employment Framework is useful, because providing services to persons enjoying administrative privileges could be a source for a conflict of interest. While the provision of the Public Ethics Law would prevail, the contradiction between the laws undermines the clarity of the legal framework for public ethics.

Discrepancies also exist between the Code of Ethics, the Public Ethics Law and the National Public Employment Framework which means that only those provisions of the Code of Ethics are valid which do not contradict the Public Ethics Law or National Public Employment Framework. While the Public Ethics prevails, it could lead to confusion.

Similarly, while the National Public Employment Framework prohibits the acceptance of gifts, the Code of Ethics allows for gift under certain circumstances. While the OA has applied the exceptions under which gifts can be received according to the Code of Ethics (which was reinforced by Decree 1179), this discrepancy can nevertheless add to confusion as to what is legally accepted. Going forward, Argentina could consider to harmonise the gift policy. A zero-gift policy might drive employees to clandestinely disregard the rule and create a feeling of distrust. For example, sanctioning an employee for having accepted a small gift might create more resentment than trusting that they will not be unduly influenced by it. Feeling distrusted, the employees might begin to secretly accept small gifts and thereby develop a tolerance of non-compliance with the gift policy (OECD, 2018[2]). Therefore, the reform of the Public Ethics Law could establish a threshold under which gifts can be accepted without reporting them. Gifts over the threshold will need to be reported and a gift registry as mandated in Decree 1179/16 published on the website of the OA.

Overall, the reform process of the Public Ethics Law could harmonise the integrity-related provisions throughout the various frameworks. By doing so, public officials would have greater clarity over the rules and standards related to integrity.

3.2.2. A clear and realistic description of circumstances and relationships leading to a conflict of interest is needed A clear and realistic description of circumstances and relationships leading to a conflict of interest is needed

A clear and realistic definition of circumstances and relationships which could lead to a conflict of interest is indispensable for an effective public ethics framework. A comprehensive definition is the basis for developing a regulatory framework and guiding and awareness-raising measures to identify and manage a conflict-of-interest situation. A conflict of interest can be defined as “a conflict between the public duty and private interests of a public official, in which the public official has private-capacity interests which could improperly influence the performance of their official duties and responsibilities” (OECD, 2004[3]). Uncertainty over the norm can be avoided by clearly setting out what circumstances and relationships can be opposed to public interests and create a conflict of interest (OECD, 2004[3]).

The Public Ethics Law currently approaches the concept of conflict of interest in connection with disqualifying factors (incompatibilidades) for the public service. It, however, does not give a clear description or definition of circumstances which can result in a conflict of interest. This may lead to an equation of conflict of interest with disqualifying factors. However, if managed appropriately, a conflict of interest situation should not disqualify the public servant from public service.

Furthermore, Article 13 contains imprecise and difficult to understand wording: “It is incompatible with the exercise of public office:

a) directing, administering, representing, sponsoring, advising, or in any other way rendering services to whoever manages or holds a concession or is a supplier of the State, or performs activities regulated by it, provided that the public office held has direct functional competence with respect to the contracting, procurement, management or control of such concessions, benefits or activities;

b) be a supplier by itself or by third parties to any body of the State in which it carries out its functions.”

In other words, Article 13 forbids public officials to perform private activities when the public position has “direct functional jurisdiction” with those private activities. The concept of direct functional jurisdiction leaves room for interpretation and makes it difficult to understand for public officials what is allowed and what is not. It also raises difficulties in implementing the policies in a consistent and effective way as it does not guarantee similar interpretation and even enforcement.

The OA has worked to provide a reasonable and logical framework to clarify this concept through various resolutions in particular cases. These resolutions act as a reference for interpreting the rather vague and general concept of ‘direct functional jurisdiction’ and show the practical limitations for enforcing the concept. According to these the OA has interpreted ‘direct functional jurisdiction' as any function over the act or contract in question (De Michele, 2004[4]).

To avoid the use of this concept of direct functional jurisdiction and offering an operative concept of conflicts of interest, Argentina could include an explanatory and brief description of circumstances leading to a conflict of interest in the Public Ethics Law to increase clarity and contribute to a better understanding and subsequent identification of conflict-of-interest situations. In addition, it would also make clear that the concept of conflict of interest goes beyond contracting, procurement, management or control of such concessions, benefits or activities as Article 13 currently states.

The OA has published a brochure about conflicts of interest which includes a brief explanation of what constitutes a conflict of interest: A situation in which “the personal interest of the person exercising a public function collides with the duties and obligations of the office held” and “a confrontation between public duty and the private interests of the official”. A similar definition could be taken as the basis for a definition of conflict of interest by the way of describing circumstances and situations leading to a conflict-of-interest situation in the Public Ethics Law.

The conflict-of-interest description should also make it clear that private interests go beyond economical and financial ones. The impartial performance of duties of public officials can be compromised by financial and economic interests, personal ties or relationships or other personal interests and undertakings. By prohibiting public officials to direct, administer, represent, sponsor, advise or in any other way render services, Article 13 raises a strong connotation that private interests equal economical and financial ones. As such it limits the applicability of the concept of conflict of interest. The Public Ethics Law could, therefore, clearly state that private interests go beyond economical and financial ones and includes personal and private occupational interests as stated in the definition of conflict of interest given in Article 41 of the Code of Ethics (Código de Ética de la Función Pública) and in accordance with the OA’s interpretation of conflict of interest in the resolution of specific cases. This way a strong operative concept of conflict of interest providing the basis for a logical legal framework would be created. In fact, articles 26 and 27 of the draft law to reform the public ethics law address this recommendation and propose a description of a conflict of interest that goes beyond economic interests.

3.2.3. Argentina could reform the Public Ethics Law to design a comprehensive system for managing conflict of interest

The vagueness of Article 13 of the Public Ethics Law is further exacerbated by not detailing a process according to which a conflict of interest can be declared and by not providing any solutions to resolve a conflict of interest. In fact, taken literally, the wording can be understood to signify a strong limitation to hold a public office or removal from office, because the law talks of incompatibilities with the public office without providing any resolution mechanism other than resignation or abstention. However, in the majority of cases where a conflict of interest was determined, the OA recommended solutions to resolve the conflict-of-interest situation, such as recusal of certain decisions, while not advising against the appointment (De Michele, 2004[4]).

Argentina has not regulated the process of declaring a conflict of interest, neither in the Public Ethics Law, the National Public Employment Framework or the Code of Ethics. Although Resolution MJSyDH 1316/08 makes it clear that any infraction of Chapter 5 of the Public Ethics Law on incompatibilities and by extension conflict of interest can result in administrative action, it does not detail how to declare a conflict-of-interest situation proactively. It is therefore unclear for public officials in a conflict-of-interest situation how to proceed. Argentina could reform the Public Ethics Law to introduce the duty to declare a conflict of interest, clearly state the actor and timeframe in which a conflict of interest has to be declared and state in which timeframe a resolution to the conflict has to be pronounced. For example, in Colombia, Article 12 of the Administrative Procedure Code (Código de Procedimiento Administrativo y de lo Contencioso Administrativo) establishes that the public official has to disclose his/her conflict of interest within three days of getting to know it to his supervisor or to the head of department or the Attorney General Office (or the Superior Mayor of Bogota or the Regional Attorney General Office at lower levels of government), according to public official seniority. The competent authority has then 10 days to decide the case and, if required, designate an ad-hoc substitute.

The proposed amendments should also help to identify a better set of remedies and solutions going beyond resignation and abstention to enhance the preventive capacity of the system as a whole. As such the law could include a non-exhaustive list of solutions that could be taken to resolve a conflict-of-interest situation, such as recusal on certain issues, divesting an economic or financial interest, creating a blind trust and similar. Article 31 of the draft law to reform the public ethics law includes this kind of solutions to resolve a conflict-of-interest situation before taking office and as such strengthens the conflict-of-interest provision.

In addition, the OA could release a form which has to be used to proactively declare and manage a conflict of interest at the specific moment it arises. The form should be filled out in collaboration between the employee and manager. It should include the following elements (Box 3.1):

-

Description of the private interest, pecuniary or non-pecuniary, impacting the official duties

-

Description of the official duties the public official is expected to perform

-

Identification of whether this is an apparent, potential or real conflict of interest

-

Signed employee declaration committing to manage the conflict of interest.

-

Description by the manager of the proposed action to resolve the conflict of interest

-

Signature of both manager and employee that has been discussed.

In order to manage a conflict-of-interest situation, employees in the Department of Social Service in Australia need to fill out a conflict of interest disclosure form. The employee is asked the following questions:

-

Describe the private interests that have the potential to impact on your ability to carry out, or be seen to carry out, your official duties impartially and in the public interest

-

Describe the expected roles/duties you are required to perform

-

The conflict of interest has been identified as non-pecuniary, a real, apparent or potential conflict of interest or pecuniary interest.

The employee then signs a declaration which declares that they have filled out the form correctly and that they are aware of the responsibility to take reasonable steps to avoid any real or apparent conflict of interest. The employee also commits to advise the manager of any changes.

The form then has to be completed by the manager describing the action proposed to mitigate the real or perceived conflict of interest and why this course of action was taken. This action has to be signed by both the employee and manager.

Once completed the form is sent to the section manager and the workplace relations and manager advisory section for retention on the employee’s personnel file.

Source: Department of Social Services, Australian Government.

The integrity contact point, which are recommended to be created in public entities (see Chapter 1), should be available for consultation in cases of doubts or act as an intermediary, if the employee does not feel comfortable to raise the issue with the manager. Once signed, the form should be reviewed by the integrity contact point and archived by Human Resources and kept with the employees file to be consulted in case of doubts over the adequate management of the conflict of interest. In contrast to the interests declared in the financial and interest disclosure, this form would identify the concrete situation at the moment when the conflict of interest appears and could infringe on the public servants’ duties and propose a solution. By proposing the solution themselves, it will also sensitise public servants on how to apply integrity in their daily work.

Targeting the private sector, Decree 202/2017 has introduced a mandatory conflict of interest declaration for anyone participating in a public procurement procedure, granting of a licence, permit, authorisation and acquisition of direct rights over a public or private property (rights in rem) of the state. This is a positive step towards reducing the risk of conflicts of interest in the procurement process by increasing transparency. The decree mandates that all government suppliers or contractors have to declare relationships, as defined by the decree, with the President, Vice-President, Chief of the Cabinet of Ministers, ministers or equal rank, even if do not have any decision-power in the procurement process, and to any public officials with decision power in the procurement process. The declaration has to be submitted prior to registering as government supplier and updated annually. The strength of the law is that it goes beyond relationships by consanguinity. It also includes any relation through society or community, a pending lawsuit, by being debtor or creditor, having received significant benefits or public friendship with a great familiarity and frequent contact. However, as criteria such as significant benefits or public friendship are not clear-cut, the OA could publish explanatory material for the private sector defining these concepts. In addition, it is positive that the law foresees steps to be taken in co-ordination with the OA to manage the conflict of interest, such as integrity pacts, participation of social witnesses or special supervision of inspection bodies.

3.2.4. The Anti-corruption Office could develop specific guidelines for at-risk categories of public officials such as senior civil servants, auditors, tax officials, political advisors, and procurement officials.

Administrative functions and sectors that are most at risk of corruption might need specific guidance taking into consideration the specific risk for these positions and sectors (see also Chapter 4). While the individual public official is ultimately responsible for recognising the situations in which conflicts may arise, most OECD countries have tried to define those areas that are most at risk and have attempted to provide guidance to prevent and resolve conflict-of-interest situations. Indeed, some public officials operate in sensitive areas with a higher risk for conflict of interest, such as justice, and tax administrations and officials working at the political/administrative interface. Countries such as Canada, Switzerland, and the United States aim to identify the areas and positions which are most exposed to actual conflict of interest. For these, regulations and guidance are essential to prevent and resolve conflict-of-interest situations (OECD, 2017[5]).

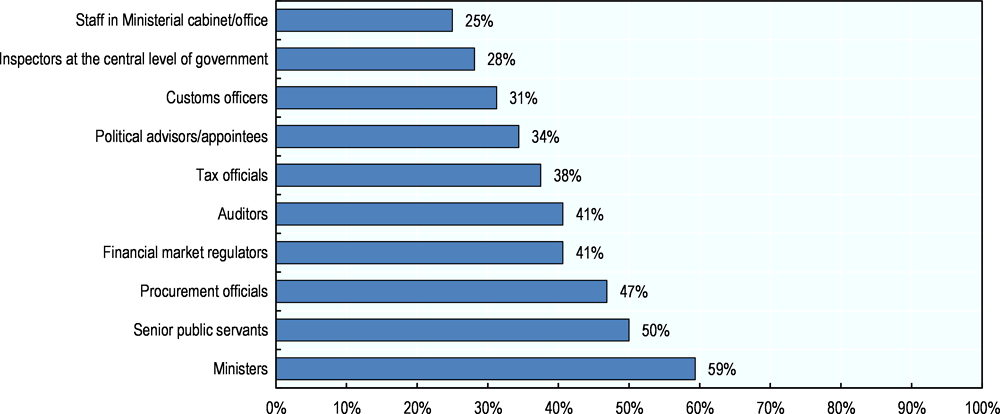

The OA currently provides guidance in specific cases to senior authorities upon designation taking into account the specific areas of risk for corruption. The OA could develop more general guidelines for specific sectors that are most at risk of corruption. For example, the OA could support public procurement officials in applying these regulations by providing a manual on conflict-of-interest situations specific to public procurement and how procurement officials can identify them. As a long-term goal, the OA could establish specific codes of ethics and guidance for other remaining at-risk areas such as senior civil servants, auditors, tax officials, and political advisors (Figure 3.1).

3.2.5. Argentina needs to introduce additional measures to implement the cooling-off period for pre- and post-public employment

The increasing trend of public officials’ movement between the public and private sector has blurred the border between the two sectors resulting in integrity concerns. While it is in the interest of the public sector to attract highly-qualified and experienced employees, the risk arises that public officials make decisions in the interests of their previous or future private employers, instead of in the public interest. Not adequately managing such a conflict undermines the integrity of the decision-making process and affects trust in the government. Therefore, policies must be designed, implemented and enforced that regulate the appearance or existence of conflict-of-interest situations (OECD, 2015[6]).

The risks arising from pre- and post-public employment are specific to each type:

-

Post-public employment: Former public officials make use of the information and connections gained during their public employment to unfairly benefit their new employer. For example, former public officials become lobbyists and use their connections to advance the interests of their clients. Similarly, during their time in office, public officials might already favour certain companies in decisions in the hope of being employed once they exit the public sector.

-

Pre-public employment: The appointment of public officials which have held key positions in the private sector creates the risk of policy formulation and regulation in favour of the previous employer or sector. This risk is in particular heightened when former lobbyists enter the public service in an advisory or decision-making capacity (Transparency International, 2010[7]).

The Observatory for Argentinian Elites (Observatorio de los Elites Argentinas) determined that 24% of the members of President Macri's initial cabinet (86 people) held a position in the private sector at the time of being appointed. Of these 86 officers, 60 were CEOs (Observatorio de las elites argentinas, 2017[8]). This can bring the risks of a heightened perception that policies and regulations are formulated not in the public interest, but in the interest of former employees and negatively affect the trust in the integrity of the public decision-making process.

While the OA is involved in advising ministers how to manage potential conflict of interest, currently limited rules or procedures for joining the public sector from the private sector or vice versa exists in the Public Ethics Law. The Public Ethics Law states that public servants have to recuse themselves from any decisions related to persons or matters they were linked to in the last three years. Moreover, it stipulates a cooling-off period of three years after leaving the public sector for public servants who have had decision-making functions in the planning, development and implementation of privatisations or concession of companies or public areas to join a regulatory body or commission of those companies or services they interacted with. The Code of Ethics foresees a cooling-off period of one year after leaving the public sector. The OA has applied this in several resolutions and advice given to high-level public servants in specific conflict-of-interest situations. Similarly, the OA sends out reminders of the cooling-off period.

To implement the cooling-off periods more effectively, for lower ranking officials it could be made mandatory for HRM offices to identify measures to manage a potential conflict-of-interest situation in collaboration with the public official and the supervisor based on the previous employers declared in the financial and interest disclosures. For the top five percent of public officials, the OA, who verifies the financial and interest disclosures, should advise the public official how to avoid a conflict of interest. While the OA is already fulfilling the advisory function in some cases, this could be made mandatory.

Argentina could consider to introduce different cooling-off periods according to the level of seniority or/and occupation instead of a one year blanket ban for every public servant and a three year ban for public servants involved in privatisations or concession of companies or public areas. In fact, article 36-40 of the draft law to reform the public ethics law addresses this recommendation and proposes a cooling off period according to the type of occupation. This is similar to the example of Canada where a one year cooling-off period exists for public officials, two years for ministers and five years for cabinet ministers. To effectively implement the cooling-off periods, many countries establish a public body or authority responsible for providing advice and overseeing the regulation. In Spain and Portugal, public officials are required to disclose future employment plans and seek approval from the advisory body (Transparency International, 2015[9]). In Argentina, the OA could fulfil the role of such an advisory body. During the cooling-off period, public officials would be required to regularly report on their employment situation in order for the OA to monitor the public official’s employment. Decisions taken on post-public employment cases should also be published online to enable public scrutiny. For Instance, in Norway, decisions are published online and routinely scrutinised by the media (Transparency International, 2015[9]). In addition, the introduction of sanctions for violating the cooling-off period would ensure a deterrent effect. For pre-public employment, this could be disciplinary sanctions, while for post-public employment, the public pension could be reduced and the private sector employer sanctioned.

3.3. Implementing integrity to support public officials to apply ethics in their daily work life

Promoting public ethics and providing guidance for identifying and managing conflict-of-interest situations for resolving ethical dilemmas are at the core of developing a culture of integrity in the public sector. Such efforts should be integrated into public management and not perceived as an add-on, stand-alone exercise.

Codes of ethics are an essential tool in guiding the behaviour of public officials in line with the official legal integrity framework. Codes of ethics make clear what kind of behaviour is expected of public officials and where the boundaries of behaving with integrity are. In order to be effective, codes of ethics should clearly articulate the core values governing the public service. A code can also provide guidance to public officials on ethical dilemmas and on circumstances and situations qualifying as a conflict-of-interest situation. On the basis of the code of ethics, in interaction with primary laws, a regulatory integrity framework can be built which promotes public ethics and managing conflict-of-interest situations in a coherent manner across the public sector (OECD, 2017[10]).

3.3.1. The Code of Ethics should be simplified

The Argentinian Code of Ethics is complementary to the Public Ethics Law which regulates the duties of civil servants, while the Code of Ethics guides behaviour and aims to cultivate integrity within the organisational culture. The Code of Ethics is applicable for the national public administration, encompasses twenty-eight general and particular principles for ethical conduct, such as probity, justice, transparency, responsibility and obedience. The principles are at times redundant, for example suitability (idoneidad) and aptitude (aptitud). Other principles are effectively not a principle, such as the particular principle of financial and interest disclosures. Argentina could consider reducing the numbers of principles to make them more memorable, meaningful and less confusing. Cognitive science has shown that a number of 5-9 principles are most suitable (Miller, 1956[11]). By concentrating on selected principles, more clarity is achieved. Within the OECD, several countries have decided to focus on key principles instead of overburdening the code. For example, in Australia the Public Service Values were reduced from fifteen rules to five values to make them more memorable. Similarly, the UK Civil Service Code outlines four civil service values. Based on the core values, individual departments might develop their own standards and values.

Similar to the revision of the Australian Public Service Values the principles could be tightened by avoiding repetition and only including actual principals that guide public ethics. The OA could involve public officials in choosing the most relevant principles for the Argentinian public service to create ownership and a common identity among public officials. In Colombia, public officials were consulted in the selection of five values ensuring that values were relevant for the public service (Box 3.3). In Brazil, a consultation process was conducted for the Comptroller General of the Union’s code of conduct raised issues that served as input for the government-wide integrity framework (Box 3.4).

In the past, the Australian Public Service Commission used a statement of values expressed as a list of 15 rules. For example, they stated that the Australian Public Service (APS):

-

is apolitical and performs its functions in an impartial and professional manner

-

provides a workplace that is free from discrimination and recognises and utilises the diversity of the Australian community it serves

-

is responsive to the government in providing frank, honest, comprehensive, accurate, and timely advice and in implementing the government's policies and programmes

-

delivers services fairly, effectively, impartially, and courteously to the Australian public and is sensitive to the diversity of the Australian public.

In 2010, the Advisory Group on Reform of the Australian Government Administration released its report and recommended that the APS values be revised, tightened, and made more memorable for the benefit of all employees and to encourage excellence in public service. It was recommended to revise the APS values to “a smaller set of core values that are meaningful, memorable, and effective in driving change”.

The model follows the acronym “I CARE”. The revised set of values runs as follows:

Impartial

The APS is apolitical and provides the government with advice that is frank, honest, timely, and based on the best available evidence.

Committed to service

The APS is professional, objective, innovative and efficient, and works collaboratively to achieve the best results for the Australian community and the government.

Accountable

The APS is open and accountable to the Australian community under the law and within the framework of ministerial responsibility.

Respectful

The APS respects all people, including their rights and heritage.

Ethical

The APS demonstrates leadership, is trustworthy, and acts with integrity, in all that it does.

Sources: Australian Public Service Commission (2011), “Values, performance and conduct”, https://resources.apsc.gov.au/2011/SOSr1011.pdf; Australian Public Service Commission , “APS Values”, https://apsc-site.govcms.gov.au/sites/g/files/net4441/f/APS-Values-and-code-of-conduct.pdf.

In 2016, the Colombian Ministry of Public Administration initiated a process to define a General Integrity Code. Through a participatory exercise involving more than 25 000 public servants through different mechanisms, five core values were selected:

-

1. Honesty

-

2. Respect

-

3. Commitment

-

4. Diligence

-

5. Justice

In addition, each public entity has the possibility to integrate up to two additional values or principles to respond to organisational, regional and/or sectorial specificities.

Source: Departamento Administrativo de la Función Pública, Colombia.

The Professional Code of Conduct for Public Servants of the Office of the Comptroller General of the Union was developed with input from public officials from the Office of the Comptroller General of the Union during a consultation period of one calendar month, between 1 and 30 June 2009. Following inclusion of the recommendations, the Office of the Comptroller General of the Union Ethics Committee issued the code.

In developing the code, a number of recurring comments were submitted. They included:

-

the need to clarify the concepts of moral and ethical values: it was felt that the related concepts were too broad in definition and required greater clarification

-

the need for a sample list of conflict-of-interest situations to support public officials in their work

-

the need to clarify provisions barring officials from administering seminars, courses, and other activities, whether remunerated or not, without the authorisation of the competent official

A number of concerns were also raised concerning procedures for reporting suspected misconduct and the involvement of officials from the Office of the Comptroller General of the Union in external activities. Some officials inquired whether reports of misconduct could be filed without identifying other officials and whether the reporting official’s identity would be protected. Concern was also raised over the provision requiring all officials from the Office of the Comptroller General of the Union to be accompanied by another Office of the Comptroller General of the Union official when attending professional gatherings, meetings, or events held by individuals, organisations or associations with an interest in the progress and results of the work of the Office of the Comptroller General of the Union. This concern derived from the difficulty in complying with the requirement given the time constraints on officials and the significant demands of their jobs.

Source: OECD (2012), Integrity Review of Brazil: Managing Risks for a Cleaner Public Service, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264119321-en.

3.3.2. Entities could develop their own codes of ethics to respond to entity-specific corruption risks

A revision of the overarching public integrity management framework, namely the Public Ethics Law and the Code of Ethics, would bring the possibility to elaborate organisational codes, aligned to the rules and standards, to effect a real cultural change.

Just as different organisations face different contexts and kinds of work, they may also be faced with a variety of ethical dilemmas and specific conflict-of-interest situations. For instance, the challenges might differ significantly between the Ministry of Foreign and Religious Affairs, Ministry of Productivity, the Ministry of Energy and Mining, and the different supervisory and regulatory bodies. Organisational Codes of Conduct provide an opportunity to include relevant and concrete examples from the organisation’s day-to-day business to which the employees can easily relate (OECD, 2017[5]).

The organisational codes should be created using consensus and ownership, and should provide relevant and clear guidance to all its employees. Consulting and involving employees in the elaboration of the codes of conduct through discussion or surveys can help build consensus on the shared principles of behaviour and can increase staff members’ sense of ownership and compliance with the code.

In addition, the experience of OECD countries demonstrates that consulting or actively involving external stakeholders – such as suppliers or users of the public services – in the process of drafting code may help to build a common understanding of public service values and expected standards of public employee conduct. External stakeholder involvement could thereby improve the quality of the code so that it meets both public employees’ and citizens’ expectations, and could thus communicate the values of the public organisation to its stakeholders. In the United States, the proposed Standards of Conduct were opened to commentaries and responses to the comments included in the preamble of the final regulation explaining why suggestions were accepted or rejected (Gilman, 2005[12]).

In Argentina, several entities and state-owned enterprises have developed a specific code of ethics by adopting their own codes of ethics, government entities can respond to specificities of functions that are considered particularly at risk. However, it may be challenging to maintain consistency among a large number of codes within the public administration. Therefore, the OA could encourage further adoption of entity specific codes of ethics and stipulate that entities have to develop their own codes of conduct based on the existing state Code of Conduct and Ethics. This would be in line with the new strategic objective of ‘Zero Corruption’ of the Internal Control System which states that each entity should develop their own Code of Ethics (SIGEN, 2017[13]). The OA would need to provide clear methodological guidance to assist the entities in developing their own codes, while ensuring that they align with the overarching principles. Such methodological guidance should reduce as much as possible the scope for developing the code as a “check-the-box” exercise, and should include details on how to manage the construction, communication, implementation, and periodic revision of the codes in a participative way.

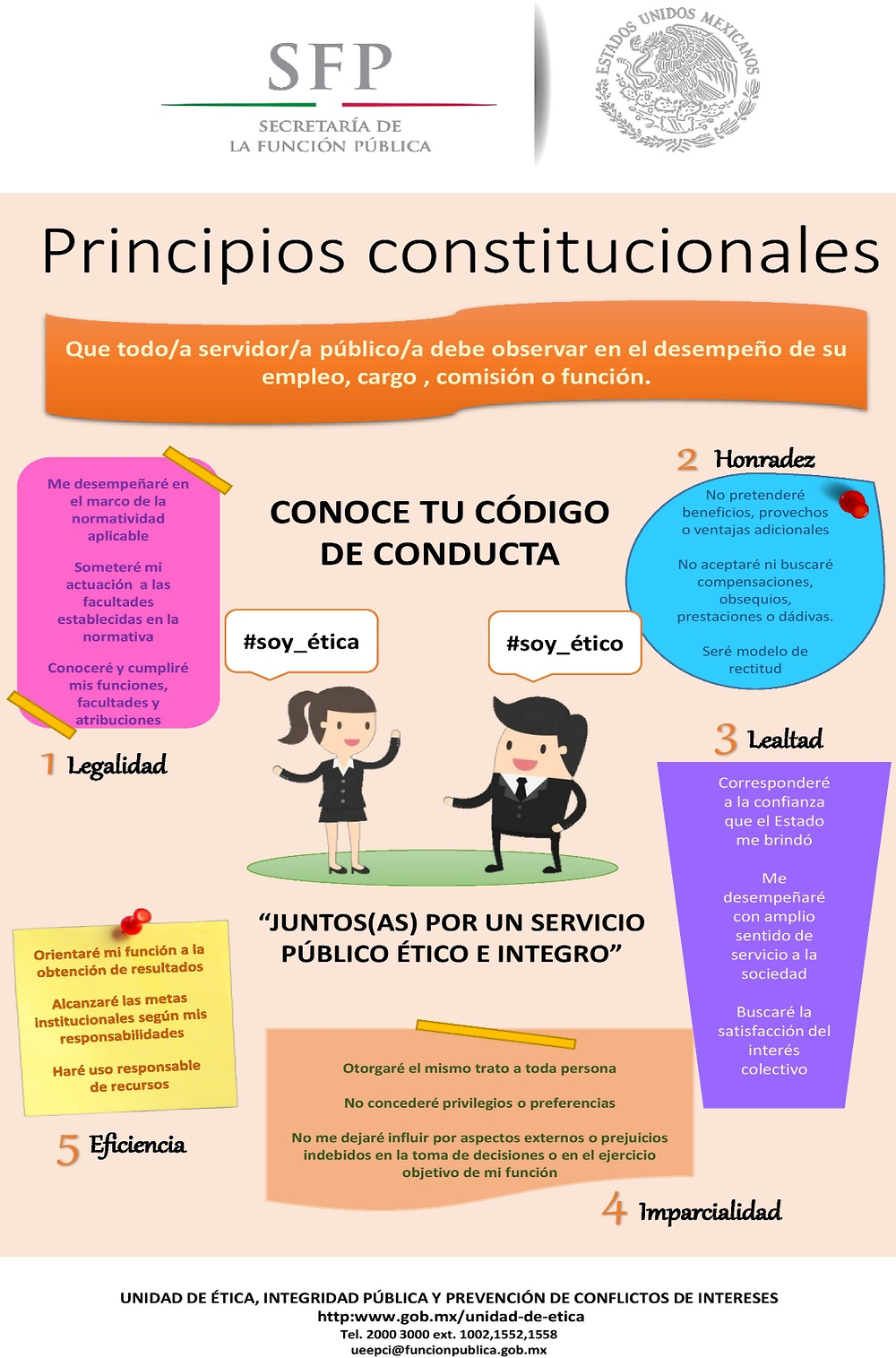

For example, in Mexico the Ethics Unit in the Ministry of Public Administration (Secretaría de la Función Pública) developed a short document outlining the main features the organisational codes should consist of to maintain consistency among the various codes and to support the ministries in the development thereof. In addition, the Ethics Unit revises each code of ethics to ensure it is in line with the overarching code of ethics.

In the short term the elaboration of the organisational codes should be piloted in one ministry, ideally in the same sector where the Ethics and Transparency Unit already exists (Chapter 1), so that this unit can lead the process, supported by the OA.

3.3.3. Argentina could reinforce the Code of Ethics with guiding and orientation material for ethical dilemmas and conflict-of-interest situations

The code is a helpful tool to define the core values public officials should observe in their work. However, additional guidance on what it means to adopt these values in their daily work could help public officials to internalise them. For example, the Code of Ethics does not provide any practical guidance how to react when two principles might oppose each other. While the specific ethical competences will need to be developed through training and practice, some general guidance could complement the code on how to react when faced with an ethical dilemma.

In Australia, for example, the REFLECT model provides public officials with general sequenced steps and reflections on how to proceed (Box 3.5). In the Netherlands, the government issued a brochure entitled “The Integrity Rules of the Game” which explains in clear, everyday terms the rules to which staff members must adhere. It considers real-life issues such as confidentiality, accepting gifts and invitations, investing in securities, holding additional positions or directorships, and dealing with operating assets (OECD, 2013).

The Australian Government developed and implemented strategies to enhance ethics and accountability in the Australian Public Service (APS), such as the Lobbyists Code of Conduct, and the register of ‘third parties’, the Ministerial Advisers’ Code and the work on whistleblowing and freedom of information.

To help public servants in their decision making process when facing ethical dilemmas, the Australian Public Service Commission developed a decision making model. The model follows the acronym REFLECT:

-

1. REcognise a potential issue or problem

-

2. Find relevant information

-

3. Linger at the ‘fork in the road’ (talking it through)

-

4. Evaluate the options

-

5. Come to a decision

-

6. Take time to reflect

Source: Office of the Merit Protection Commissioner (2009), “Ethical Decision Making”, http://www.apsc.gov.au/publications-and-media/current-publications/ethical-decision-making.

The OA has developed several guides and manuals to make public servants aware of the values that guide public service. Concerning guidance and orientation specific to conflict-of-interest situations, the OA has developed an online conflict-of-interest simulator. Through the selection of answers to certain questions, public officials receive an assessment assess whether they are in a situation of current or potential conflict of interest. The simulator is available for future, current and past public officials. By asking the public official various questions, the simulator determines if the official is in a conflict-of-interest situation. If a potential conflict of interest is detected, the simulator informs the official of the violated norm of the Public Ethics Law and advises the public official to seek guidance of the OA. The simulator is a useful tool to enable officials to clarify any doubts they might have over a situation. It could be further improved by including contact details to the OA or integrity contact point to facilitate the contact and links to any guiding material.

3.4. Mainstreaming integrity in Human Resources Management

The Merit principles requires staffing processes to be based on ability (talent, skills, experience, competence) rather than social and/or political status or connections. In governance, merit is generally presented in contrast to patronage, clientelism, or nepotism, in which jobs are distributed in exchange for support, or based on social ties.

A merit based civil service is a fundamental element of any public sector integrity system. A growing body of research shows that merit-based civil service management reduces corruption risks (Dahlström, Lapuente and Teorell, 2012[14]). The reasons for this are multiple:

-

As a first step, having merit systems in place reduces opportunities for patronage and nepotism, which, in extreme cases, can be serious forms of corruption when jobs are created solely for the purpose of awarding salaries to friends, family, and political allies. This constitutes a direct diversion of public funds for private gain.

-

Merit systems also provide the necessary foundations to develop a culture of integrity and public ethos. By bringing in better qualified professionals and providing for longer-term employment, merit systems reinforce civil servants’ commitment to public service principles and values and reinforce an open culture, where employees do not risk losing their job when raising integrity concerns.

-

Having merit systems in place provides the necessary infrastructure and processes to integrate integrity testing and values-based assessments to HR decision making.

There is a wide range of tools, mechanisms and safeguards that OECD countries use to promote and protect the merit principle in their public administrations. Regardless of the specific tools, the following features are all essential components of a merit-based civil service:

-

Predetermined appropriate qualification and performance criteria for all positions.

-

Objective and transparent personnel management processes which assess candidates against the criteria specified in a) above.

-

Open application processes which give equal opportunity for assessment to all potentially qualified candidates.

-

Oversight and recourse mechanisms to ensure a fair and consistent application of the system.

3.4.1. The merit principle could be reinforced by limiting the use of short-term contracts and using the same qualification and performance criteria for these positions as for permanent positions

In order to have a merit based civil service system, there needs to be a transparent and logical organisational structure which clearly identifies positions and describes the role and work to be performed by this position. This ensures that the creation of new positions is done with the right intent, based on functional need. In systems where patronage and nepotism is a high risk, it is necessary to make the full organisational chart open to public scrutiny.

Argentina has recently begun developing a common job classification system that would enable the kind of classification architecture necessary to identify appropriate job profiles. Article 16 of Decree 2098/2008, the Collective Labour Agreement of the National System of Public Employment (SINEP), states that the state as employer shall develop the a Nomenclature Classifying Positions and Functions together with a Central Directory of Labour Competencies and Minimum Requirements for Positions and Functions. In 2017, the National Office of Public Employment (ONEP) developed the Nomenclature classifying positions and transversal functions for administrative positions to identify and organise the general framework of functions and tasks of positions and standardise those positions with similar tasks. The Nomenclature classifies those positions with cross-cutting characteristics, i.e. non-specific positions in an entity with essential supporting functions. In compliance with article 58 of Decree, the General Labour Agreement for the National Public Administration, cross-sectional profiles have been drawn up which will be used for the next selection processes in 2018. At the time of this review, the classification for technical positions was under review.

Together with the classification of positions and identification of profiles, ONEP prepared a common Directory of Competencies, not yet formally regulated, presented to all entities and initiating training activities. The ONEP provides technical assistance and permanent guidance to HRM regarding the implementation of the Directory of Competencies in the different HRM processes (e.g. the elaboration of job profiles in the selection process and development of specific training itineraries)

These steps may begin to reinforce the merit principle in the civil service in Argentina Implementing these tools will require significant resources to support implementation and oversight, to ensure they are used as intended.

In addition to predetermined qualification and performance criteria for all positions, personnel management processes need to be established to assess candidates against the established criteria. Merit-based systems generally emphasise the process of entry into civil service or public institution is generally the first line of defence against nepotism and patronage.

In general, the following principles should be applied to all of these processes:

-

Objectivity: decisions are made against predetermined objective criteria and measured using appropriate tools and tests that are accepted as effective and cutting edge by the HR profession.

-

Transparency: decisions are made in the open, to limit preferential treatment to specific people or groups. Decisions are generally documented in such a way that key stakeholders, including other candidates, can follow and understand the objective logic behind the decision. This enables them to challenge a decision which seems unfair.

-

Consensus: decisions are based on more than one opinion and/or point of view. Multiple people should be involved, and efforts should be taken to strive for a balance of perspectives, particularly on processes which are less standardised and open to subjective interpretation, such as interviews or written (essay) examinations.

Argentina’s selection system for permanent civil servants appears to follow the spirit of these principles. Additionally, a new resolution (E 82/2017) appears to extend merit based recruitment to senior levels of the civil service. This is a positive development which stands to improve stability and effectiveness of public management in Argentina.

Despite these positive signs, it appears that employment regimes (e.g. contratados) designed for temporary workers allow employers to bypass merit-based recruitment. By law, organisations are expected to limit non-permanent contracts to 15% of the total workforce, however various sources suggest that these regimes are used for staffing positions of a permanent nature beyond their intended scope. Many workers may find themselves on short-term contracts that are renewed indefinitely (Bertelsmann Stiftung, 2016[15]; OEA/Ser.L. and SG/MESICIC/doc.490/16. rev. 4, 2017[16]).

Reliable data on the numbers of employees on different contracts is not available. This is also a cause for concern since, without reliable data on the numbers of employees and types of contracts, oversight and accountability is impossible to maintain. Statistics from the Ministry of Finance suggest that contracted staff made up 20% of the total in 2017. However similar statistics from the Ministry of Modernisation suggest that 34% of the workforce is on short term contracts. Decree 263/2017, creating an integrated information data base on public employment and wages (Estructura Base Integrada de Información de Empleo Público y Salarios, or BIEP), aims to improve the quantity and quality of data available. The National Directorate of Information Management and Wage Policy (Dirección Nacional de Gestión de Información y Política Salarial) in the Public Employment Secretariat of the Ministry of Modernisation manages the system and receives the information from the different entities and processes and standardises it.

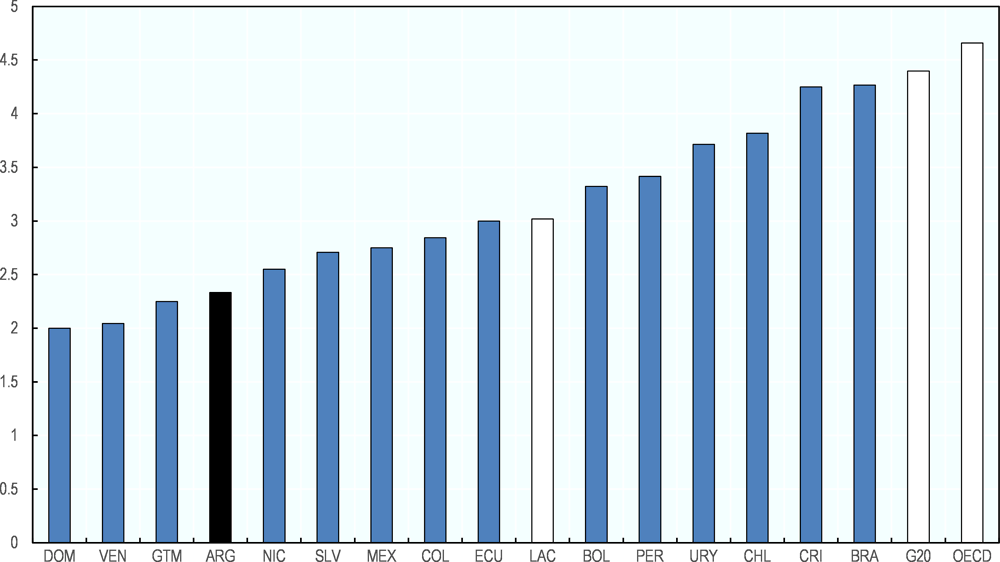

The assessment, concerning the weaknesses of the employment regime for temporary workers, is echoed by the Bertelsmann Transformation Index (2016) which states that, “Though civil service positions are meant to be assigned through merit-based competition, non-competitive recruitment is widely used to bypass the system. Many jobs in the public sector are the result of machinations within clientelistic networks, especially at the province level.” The Quality of Governance Expert Survey, data based on the survey of experts on public administration, confirms the high degree of politicisation of the public administration in Argentina (2.3) which is perceived to be below the Latin America (3.0) and OECD average (4.6). It is an indication of the extent to which politics and/or political affiliation impacts staffing in the civil service (Figure 3.2).

One approach would be to take steps to limit the use of short term contracts and plug the loophole that enables these employees to bypass the merit based selection process. Additionally, steps could be taken to apply merit based recruitment to short term employees in a similar way as it is applied to permanent staff. As an initial measure, for which implementation cannot yet be assessed, a new internal selection process for temporary staff was agreed with trade unions that signed the collective framework agreement for public employment. The aim is to standardise the selection of temporary staff through a transparent selection process.

Decree 93/2018 prohibiting the recruitment of relatives up to the second degree of the president, vice-president, ministers and similar positions is a step in the right direction to counter nepotism. However, by limiting the decree to ministers and above and relatives, only a small part of the big picture is covered. As such, Argentina could consider extending the prohibition to lower-ranking public officials, such as up to the level of secretary. In addition, a mandatory disclosure of family relations during the recruitment process could be introduced to ensure that any potential conflict-of-interest situation can be managed for lower-ranking officials.

A third fundamental component of merit is the principle of open and equal access. This is key as it helps to ensure that the best person for the job, is able to come forward and be considered for the job regardless of their location, demographic characteristics, social status, or political affiliation.

In Argentina, open recruitment appears to be part of the regulatory regime of civil servants (and now for Senior Civil Servants as well), although this review has not looked in detail at the effective functioning of this. Similarly to the point above, since these regulation do not apply to other employment regimes, there appears may be ways to bypass open recruitment.

3.4.2. To ensure that senior management acts as role models, integrity could be included as a performance indicator

Senior civil servants exemplify and transmit the public service and organisational values. The leadership fosters credibility in the norms and standards by making the values in the code of conduct applicable to the daily work and acting according to these. Above all, it can build trust in the processes. Empirical studies of ethical leadership show that it does have a beneficial impact not only on the ethical culture of an organisation, but also on performance: “subordinates ‘perceptions of ethical leadership predict satisfaction with the leader, perceived leader effectiveness, willingness to exert extra effort on the job, and willingness to report problems to management” (Brown, Treviño and Harrison, 2005[18]).

To be an ethical leader, two interrelated aspects are required:

-

the leader needs to be perceived as a moral person who understands their own values and uses them to make the right decision faced with an ethical dilemma

-

the leaders needs to be perceived as a moral manager who make open and visible ethical decisions, reward and sanctions others based on ethical criteria, communicate openly about ethics and give employees the opportunities to make their own ethical guidance and encourage them to seek advice (OECD, 2018[19]).

In Canada, the Key Leadership Competencies Profile defines the behaviours expected of leaders in the Public Service in building a professional, ethical and non-partisan public service. The competency to ‘uphold integrity and management’ highlights the role of leaders to create a work environment in which advice is sought and valued and ethical conduct is exemplified and encouraged. The Competency Profile is taken into account for selection, learning, performance and talent management of executives and senior leaders (OECD, 2019[20]).

One of the key leadership competences Canadian executives and senior leaders are measured against is to ‘Uphold integrity and respect’. This signifies that leaders model ethical practices, professionalism and integrity. They build an open organisational culture in which employees are confident to seek advice, express diverse opinions and uphold collegiality.

Examples of effective and ineffective behaviour to uphold integrity and respect for the different levels are given:

Deputy Minister

-

Values and provides authentic, evidence-based advice in the interest of Canadians

-

Holds self and the organization to the highest ethical and professional standards

-

Models and instils commitment to citizen-focused service and the public interest

-

Builds and promotes a bilingual, inclusive, healthy organization respectful of the diversity of people and their skills and free from harassment and discrimination

-

Exemplifies impartial and non-partisan decision-making

-

Engages in self-reflection and acts upon insights

Assistant Deputy Minister

-

Values and provides authentic, evidence-based advice in the interest of Canadians

-

Holds self and the organisation to the highest ethical and professional standards

-

Models and builds a culture of commitment to citizen-focused service and the public interest

-

Builds and promotes a bilingual, inclusive, healthy organization respectful of the diversity of people and their skills and free from harassment and discrimination

-

Exemplifies impartial and non-partisan decision-making

-

Engages in self-reflection and acts upon insights

Director General

-

Values and provides authentic, evidence-based advice in the interest of Canadians

-

Holds self and the organization to the highest ethical and professional standards

-

Models commitment to citizen-focused service and the public interest

-

Creates opportunities that encourage bilingualism and diversity

-

Advances strategies to foster an inclusive, healthy organization, respectful of the diversity of people and their skills and free from harassment and discrimination

-

Exemplifies impartial and non-partisan decision-making

-

Engages in self-reflection and acts upon insights

Director

-

Values and provides authentic, evidence-based advice in the interest of Canadians

-

Holds self and the organization to the highest ethical and professional standards

-

Models commitment to citizen-focused service and the public interest

-

Creates opportunities that encourage bilingualism and diversity

-

Implements practices to advance an inclusive, healthy organization, respectful of the diversity of people and their skills and free from harassment and discrimination

-

Exemplifies impartial and non-partisan decision-making

-

Engages in self-reflection and acts upon insights

Manager

-

Values and provides authentic, evidence-based advice in the interest of Canadians

-

Holds self and the organization to the highest ethical and professional standards

-

Models commitment to citizen-focused service and the public interest

-

Supports the use of both official languages in the workplace

-

Implements practices to advance an inclusive, healthy organization, that is free from harassment and discrimination

-

Promotes and respects the diversity of people and their skills

-

Recognizes and responds to matters related to workplace well-being

-

Carries out decisions in an impartial, transparent and non-partisan manner

-

Engages in self-reflection and acts upon insights

Supervisor

-

Values and provides authentic, evidence-based advice in the interest of Canadians

-

Holds self and the organization to the highest ethical and professional standards

-

Models commitment to citizen-focused service and the public interest

-

Supports the use of both official languages in the workplace

-

Implements practices to advance an inclusive, healthy organization, that is free from harassment and discrimination

-

Promotes and respects the diversity of people and their skills

-

Recognizes and responds to matters related to workplace well-being

-

Carries out decisions in an impartial, transparent and non-partisan manner

-

Engages in self-reflection and acts upon insights

Examples of generic ineffective behaviours for all roles

-

Places personal goals ahead of Government of Canada objectives

-

Shows favouritism or bias

-

Does not take action to address situations of wrongdoing

-

Mistreats others and takes advantage of the authority vested in the position

Source: Government of Canada, Key Leadership Competency profile and examples of effective and ineffective behaviours, available from https://www.canada.ca/en/treasury-board-secretariat/services/professional-development/key-leadership-competency-profile/examples-effective-ineffective-behaviours.html.

Having included integrity and institutional ethics as one of the competencies in the new Competency Directory, the ONEP could ensure that integrity is incorporated, both as a formal assessment criterion and in the way the assessment is conducted. For example, performance goals could focus on the means as well as the ends, by asking how the public official achieved the goals. The integrity component of performance assessments needs to be backed up by rewards or sanctions. Leaders who are particularly strong on integrity could be identified for career development opportunities, particularly to positions of higher ethical intensity. Those with lower assessments should be given developmental opportunities and, if necessary, removed from their position if significant risks are identified. Special recognition could also be given to those public officials that consistently engage in meritorious behaviour or contribute to building a climate of integrity in their department by for example identifying new processes or procedures that will promote the code of ethics (OECD, 2017[5]). During these meetings, it could also be helpful to discuss general issues concerning the division of labour, team work etc. If taken seriously and not as a check-the-box exercise, such a regular discussion would help to make integrity one of the priorities of work performance.

3.5. Developing capacities and raising awareness for integrity to promote a change of behaviour

3.5.1. The impact of the ethics training could be strengthened by designing more practical training elements and follow-up

Article 41 of the Public Ethics Law provides that the authorities responsible for implementing the Act shall run ongoing training programmes disseminating the contents of the Act and its implementing regulations and ensure that the persons covered by the Act are duly informed of its provisions. It adds that public ethics shall be taught in specific courses at all levels of the educational system. In case of the executive, the OA is the responsible entity. In practice, the OA is responsible for designing training specific to entities or to functions at higher risk of corruption, while the INAP leads the development of administration-wide training courses.

The OA has developed a Public Ethics Training System (Sistema de Capacitación en Ética Pública, or SICEP) which operates an online platform under the Ministry of Justice and Human Rights. Through this platform, the OA provides virtual courses to train public servants in integrity and public ethics. The OA also uses the online platform managed by the INAP to ensure that it reaches the majority of employees in the national public sector. In addition, the OA uses more traditional training options, such as face-to-face programmes and courses, seminars, workshops and discussion groups.

Under the premise of developing new teaching and technical resources, Argentina is currently collaborating with the World Bank to establish a system for training Federal Public Administration staff and employees on matters relating to integrity, public ethics and the implementation of transparency policies in administration. The OA developed the terms of reference for the design, elaboration and production of pedagogical and audio-visual material according to the tasks and responsibilities of the public servant. The training courses will focus on the following aspects:

-

Enforcement of the Civil Service Ethics Regulations nationwide: Training government employees in ethical principles and standards, transparency, and public information;

-

Administrative procedures, especially those relating to procurement and hiring, the implementation of transparency policies and respect for public ethics

-

The administering of asset and interest declarations in such a way as to support public ethics policies, transparency and the prevention of corruption and overcome the challenges associated with enforcing presentation of the sworn statements.

The project will also build a pool of trainers in the ministries to conduct the trainings in their ministries. The project estimates to enable the OA to have 50 trainers and, within three years, to have provided face-to-face and partly face-to-face/partly virtual training to 15,000 public servants (OEA/Ser.L. and SG/MESICIC/doc.490/16. rev. 4, 2017[16]). This is a positive step to ensure greater reach of the training and enhance the impact of the training as courses can be tailored to ministries’ specific needs. Once the capacities are built, induction training for public officials on public ethics should be made mandatory irrespective of the public official’s contractual status. In addition, refresher courses could be offered. Moreover, the OA needs to enable the exchange of experience between them to ensure good quality standards. For this purpose, trainers should meet from time to time to discuss problems they face, to exchange training case studies and to agree on the common approaches to ethical dilemmas. Trainers should also be encouraged to participate in each other trainings and be adequately compensated. The advantage of this trainer pool would be that entity and function-specific trainings could be held which would further help the public officials to internalise integrity as part of their official job identity as content will be even more relevant.

In addition, the Sub-Ministry of Labour Relations and Strengthening of the Civil Service (Subsecretaría de Relaciones Laborales y Fortalecimiento del Servicio Civil) in the Ministry of Modernisation, in collaboration with the INAP has developed a four hour online course on public ethics. By attending this course public officials can earn credits towards promotion in their administrative career. Moreover, the learning effect of the course could be further strengthened by including a discussion forum in which guided by a moderator, the participants are encouraged to think through an ethical dilemma and a conflict-of-interest situation. By imagining the situation and arguing for and against different options on the platform, the officials will memorise the situation better and will find it easier to identify similar situations.

A more extensive online course (36 hours) is offered for senior management. Throughout the duration of the course an online platform for exchange with the group is available. Participants are encouraged to actively participate in the discussions, seek advice or consult others. In addition, a tutor is available to answer any doubts or other questions during the learning process. Conducting some of the sessions in-person could maximise the training effect. While theoretical concepts can easily be taught online, acting ethical dilemma situations or conflict-of-interest situations out and discussing with other participants for one side or another can deepen the learning effect. For example, if one group argues why a situation constitutes a conflict of interest, while another argues against it, participants will memorise the situation better, identify better with the arguments and think through them. Considering this, INAP and the Sub-Ministry could conduct the practical exercise in-person. Depending on the size of the course, this could also be conducted in break-out groups, combining public officials from different areas to ensure various few points in the discussions.

In addition, the training could include a component in which senior management identify individual risks and challenges to integrity and develop a personal plan to mitigate these risks. In a follow-up to the training, participants discuss whether they were able to follow the plan, discuss barriers and opportunities in implementing the actions identified in the individual action plan and provide each other support and share solutions.

For both trainings, a large gap between the offered places and the actual inscription rate for the courses exists. This could be due to the voluntary nature of the courses. In 2017, only 2 063 places of 3 010 were filled. Therefore, Argentina could consider making these courses mandatory to ensure that the highest number of public officials benefit from the training and apply public ethics in their work. This would mean that the human and budget resources for the trainings need to be considerably boosted to ensure that all public officials qualifying for the training have access. In addition, the Secretary of Public Employment would need to reinforce its efforts to encourage public servants to undertake the course and promote it.

3.5.2. The Secretary of Public Employment could develop a mentoring programme for public officials at the junior level to build a pool of ethical leaders for the future

Partnering public officials in junior position who show the necessary potential to advance to leadership positions with senior managers who have proven integrity and ethical conduct and reasoning through a formal mentorship programme is another measure to motivate ethical behaviour in an organisation (Shacklock and Lewis, 2007[21]). This does not only support the junior public officials, but can also strengthen the senior public official’s ethical convictions and contribute to an open organisational culture in which public officials feel comfortable to report wrongdoing.

The Ministry of Modernisation has created a mentoring programme for junior public officials called “Leaders in Action’ (Líderes en Acción), aiming to equip junior professionals agents of change and innovators in their teams. The Ministry of Modernisation could strengthening this mentoring programme in the following way: Mentors could help their colleague to think through situations, where they have recognised the potential for conflict of values. In this way young professionals develop ethical awareness, so that they are able to foresee and avoid ethical dilemmas. The Secretary of Public Employment could pilot a mentoring programme in its own entity. The commitment of mentors could be positively assessed in the performance evaluations.

3.5.3. The Anti-Corruption Office could design and test different behavioural reminders

Moral reminders have also shown to be an effective tool to counteract unethical behaviour by reminding people of ethical standards in the moment of decision making ( (Mazar and Ariely, 2006[22]) ; (Bursztyn, 2016[23])). Inconspicuous messages, such as “thank you for your honesty”, can have a striking impact on compliance (Pruckner, 2013[24]). To achieve this impact, however, the interventions have to be timed closely before the moment of decision making (Gino and Mogilner, 2014[25]). If the individual is exposed to the reminder at high frequency, however, the positive effect of the moral reminder might diminish over time. Nonetheless, where policy makers can place a message in proximity of an integrity risk decision that is not taken too frequently by the same person, this could make a great difference. Therefore, Argentina could identify processes and procedures for the potential installation of a moral reminder (OECD, 2018[2]).

The OA carries out several actions aimed at disseminating the norms on public ethics and conflicts of interest, as well as to encourage the self-evaluation of agents and officials regarding their situations:

-

Design of dissemination material (posters, leaflets)

-

Design of manuals on specific procedures (instructions on registration of gifts to public officials and trips financed by third parties)

-

In addition, the information bulletins are issued by OA, along with guidelines on public ethics issues, such as the newsletters on "Tools for Transparency in Administration. Guideline No. 1: Conflicts of Interest," "Tools for Transparency in Administration. Guideline No.2: Sworn Statements," "Tools for Transparency in Administration. Guideline No. 3: Citizen Participation."

In order to develop a targeted and effective awareness-raising campaign of the ethics values and standard, the OA could test measures in different entities to evaluate the effectiveness of each one. This could reinforce an already existing mechanism or developing new ones. For example, in Mexico, the Ministry of Public Administration conducted an experiment to test which kind of reminder message would encourage employees to comply with the gift registration rule (Box 3.7). Similarly, entities could choose a “value of the month” from the Code of Ethics which would be sent to all staff at the beginning of each month with a short explanation what it means in practice and what not. To encourage staff to read and internalise the value, a short quiz at the end could be included. If answered correctly, the official will gain points which can be accumulated over time and redeem their points for a small prize. In addition, statements by prominent people from public life could record short video messages underlining their commitment to public integrity and what it means for them to act with integrity. These videos could be spread throughout organisations’ internal communication channels or used as screensavers or desktop wallpaper changing periodically.

A gift registry only works when public officials actually register the gifts they receive. To test which kind of messaging motivates employees to comply with the gift registration rules, the Secretaría de la Function Pública (SFP) in Mexico, in cooperation with the research centre CIDE, conducted a field experiment: When SFP sent out reminder emails to public employee required to register their received gifts, they randomly varied the text of the message. Five different types of reminder messages were sent:

-

Legal: It is your legal obligation to register received gifts.

-

Honesty: We recognize your honesty as a public official. You are required to register gifts. Show you honesty.

-

Impartiality: Receiving gifts can compromise your impartiality. When you receive a gift, register it.

-

Social: More than 1 000 registration per year are made by your colleagues. Do the same!

-

Sanction: If you receive a gift and you do not inform us, someone else might. Don’t get yourself punished. Register your gifts.

The study then observed the amount of gift registered around Christmas (peak season for gifts) in comparison previous years and to a control group, who did not receive any reminder message. Having received a reminder email increased the number of gifts registered. However, some messages were more effective than others: Reminding public officials of their legal obligations and appealing to their impartiality and honesty encourage more people to register gifts than referring to sanctions or registrations made by colleagues.

The study illustrates two things: (1) small behavioural nudges can increase the compliance with an existing policy, (2) appealing to values and integrity changes behaviour more effectively than threatening with sanctions.

Source: Centro de Investigación y Docencia Económicas and Consejo Nacional de Ciencia Tecnología, Mexico.

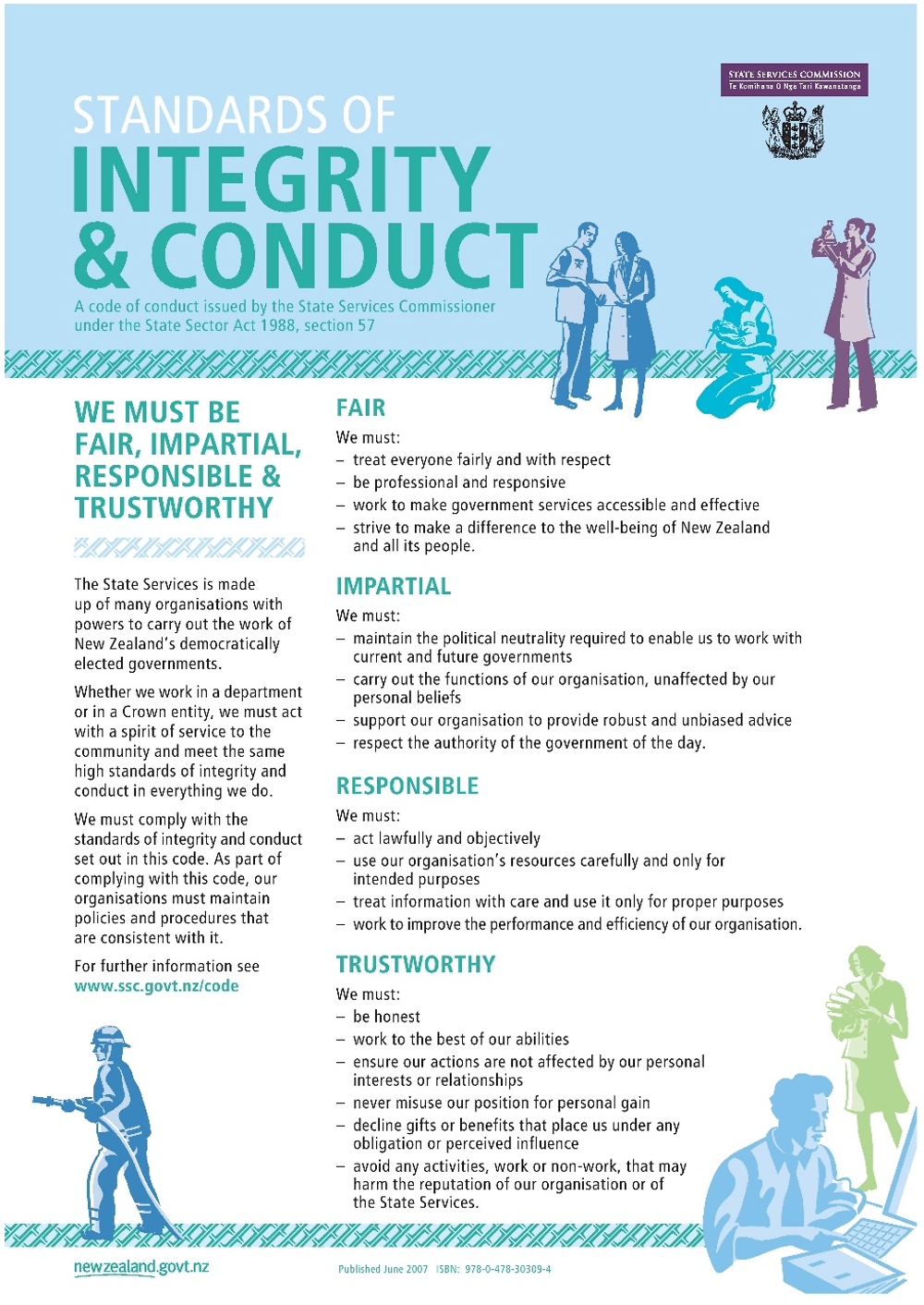

Another example would be to design and distribute posters with concrete examples about what a particular value might mean. The idea is that it would encourage public officials to think about the value and internalise it. For example, the poster of the constitutional principles in Mexico (Figure 3.3) and the poster of the Standards of Integrity and Conduct of New Zealand (Figure 3.4) , which is displayed to public officials and citizens in public institutions, gives concrete examples about what each value means.

3.5.4. On an annual basis, Argentina could award an Integrity in the Public Service Award to public officials showcasing ethical behaviour

A key factor in determining the ethical environment in an organisation is social identity (Akerlof and Kranton, 2011[26]; Tyler, 2011[27]). People orient their action by what they perceive to be acceptable within their social context – whether this is a culture, society, or peer group. Successful awareness-raising and communication campaigns aim to highlight integrity as part of the existing identity and as a norm that it is worth investing in. In this way the perception of public officials can be positively influenced.