8. Enabling SME linkages with foreign firms in global value chains

This chapter describes trends in MENA economies’ participation in global value chains and provides measures of supply chain linkages between multinationals established in the region and domestic SMEs. It gives an overview of relevant policies and programmes in the eight MENA economies to enable SME linkages with foreign firms in global value chains. The chapter also sheds light on policy priorities and discusses policy options for MENA governments to support business relationships with higher sustainable development impacts.

One of the most notable traits of the global economy over the past few decades is the organisation of international production, trade and investment within global value chains (GVCs), where different stages of the production process of various goods are located across different countries. Many factors have driven the rise of GVCs, including the reduction of barriers to trade and investment, the increasing sophistication of MNEs’ business strategies and the efforts by countries and industries to specialise in activities where they have or can develop a comparative advantage. The future of GVCs is driven by additional factors such as trade tensions and major disruptions brought about by Covid-19, which is leading companies and countries to reassess the benefits and costs of GVCs.

Taking advantage of GVCs is an important policy focus for countries aiming to raise productivity, create quality jobs, and acquire knowledge and technology that allow engaging in activities with higher levels of value added. Helping domestic firms, in particular micro, small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) to participate in GVCs is crucial in this regard, including by fostering linkages between SMEs and foreign companies. SMEs can plug into GVCs through the provision of inputs of goods and services to MNEs established in their countries. This enables them to create jobs, develop skills, improve workers’ conditions, upgrade products or services to meet global standards, or adopt more sustainable production processes.

MENA countries’ engagement in GVCs reflects the different compositions of their export baskets, their positioning in supply chains and other aspects such as trade and investment regulations, political stability, the quality of infrastructure and human capital. For example, Algeria’s participation in GVCs is limited to oil exports and hindered by a challenging, albeit improving, business climate. The scenario is similar in Libya, although the situation is aggravated by political instability and conflict. Egypt, Jordan, Morocco and Tunisia rely more on foreign inputs to engage in GVCs and diversify their exports, given their larger private sectors and greater openness to trade and investment. However, gains from GVCs in those countries have been relatively limited in terms of knowledge and technology diffusion and engagement in higher value-added activities. GVC participation in Lebanon is also confined to trade in relatively low value-added goods and adversely affected by the socioeconomic instability over the past few years and months.

Foreign business has to some extent helped SMEs in the region integrate in GVCs. For instance, foreign manufacturers’ sourcing of local inputs is relatively high in Egypt and Morocco, although it is not possible to infer whether this is the result of a proactive decision by the foreign firm or because of local content requirements. Overall, linkages between foreign and local businesses in the MENA economies covered in this report (MENA focus economies) mostly involve sourcing of low-skilled inputs rather than contractual arrangements for R&D or other upstream activities. Furthermore, in some countries, including Jordan and Morocco, sourcing relationships are dominated by foreign firms supplying intermediate inputs to other foreign firms hosted in the country, reflecting the fact that domestic SMEs face challenges in producing goods that meet international standards.

Policy efforts supporting greater and more resilient SME-MNE linkages can help MENA countries better engage in GVCs to support recovery from the Covid-19 crisis. Broader business climate reforms are pre-conditions for enabling business linkages, particularly in less diversified and competitive economies. For example, barriers to FDI in services in the region impede the deployment of foreign projects that are crucial for GVC participation and export diversification (Chapter 4). Openness to services can reduce input costs and improve the quality and availability of services. Targeted policy action is also required, for example to address the low levels of SME productivity, which reduce the propensity to promote transfers of technology and managerial expertise. Initiatives helping SMEs to establish business linkages to MNEs are particularly important in this regard. While MENA governments have deployed such initiatives, these often lack an overarching government strategy. Initiatives tend to be scattered across different institutions, implemented on an ad hoc basis and are not part of a specific, more explicit, linkages programme.

Assess and address barriers in the business environment preventing SME-MNE linkages. Priorities include improving legal security and property protection rights (e.g. investment, bankruptcy and intellectual property rights laws and regulations, and effective contract enforcement mechanisms) and reducing regulatory barriers hampering investment in sectors that are crucial for participating in increasingly digitised GVCs, particularly in the aftermath of the Covid-19 crisis. Active dialogue with the private sector is essential in this regard.

Establish mechanisms to facilitate the flow of information on GVC opportunities for domestic firms and on local suppliers and SME partners for foreign investors. This requires collaboration between investment promotion agencies (IPAs), SME agencies, investors and private sector associations, among other actors.

Foster the development of a market of business development services (BDS) for SMEs to establish linkages with MNEs in GVCs. This includes supplier development programmes such as those helping SMEs to form consortia (e.g. to respond to large orders from clients), improving quality, strengthening managerial and technical skills, etc. This also includes programmes to facilitate SME access to resources such as finance, technology, knowledge and skills. Co-operation between firms, SME agencies and BDS providers (e.g. incubators, private providers, associations, etc.) is important.

Promote RBC standards as a means to signal safe local sourcing, a signal that can be particularly important for multinationals doing business in conflict-affected states. Governments with more established RBC standards could include RBC principles and standards in, inter alia, industry-specific training programmes as a way to build absorptive capacity of domestic SMEs.

Move away from wide tax holidays to targeted tax deductions when firms forge R&D or other partnership agreements with local suppliers. Zone-based policies such as reduced VAT on deals between firms inside and outside zones can incentivise linkages, and be an alternative to local content requirements, but related administrative procedures should not discourage firms from using such tools.

Further promote investment by diaspora, and their anchoring through linkages with local suppliers, by increasing outreach efforts and developing, in consultation with diaspora representatives, tailored attraction strategies and programmes.

Support the efforts of firms to build more resilient GVCs and help them recover from Covid-19 crisis. This includes:

Collecting and sharing information on potential concentration and bottlenecks upstream, by developing stress tests for essential supply chains and by creating a conducive regulatory environment that is not a source of additional, policy-related, uncertainty.

Maintain, through IPAs’ intensified and digitised aftercare services, close contact with foreign firms with established relationships with local suppliers to address challenges related to disruption in GVCs resulting from the Covid-19 pandemic.

SMEs and entrepreneurs are widely acknowledged as major economic and social agents in all countries, contributing to important shares of employment and production and playing a significant role in innovation and value creation. For example, in the OECD area SMEs account for about 60% of employment and 50-60% of value added (OECD, 2019[1]). In developing and emerging economies, SMEs and self-employment also play an important role, as they provide sources of income, goods and services to millions of people and act as a social buffer in the absence of adequate social security systems and other sources of jobs. A recent ILO study notes that formal and informal self-employment accounts for above 50% of total employment in low-income countries and for 60% in lower middle-income countries. If employment in micro firms (2-9 persons employed) is also taken into account, the figures are about 90% of employment in low-income countries and over 80% in lower middle-income countries. In the MENA region self-employed (formal and informal) and micro enterprises account for 70% of employment, just behind South Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa (80% in both) (ILO, 2019[2]).

Encouraging and facilitating the participation of SMEs in international markets is an important means to promote innovation, economic growth and higher productivity. Internationalisation gives SMEs access to opportunities for business expansion, increasing productivity and acquiring international knowledge and technology. Furthermore, given their economic and social importance, SMEs can also be particularly effective actors to address the polarising effects of a country’s participation in global markets. Those effects include productivity and wage gaps between firms and industries, development gaps between geographical areas, inequalities of income, wealth and opportunities among social groups, etc.

SME participation in international markets can take several non-mutually exclusive forms. The most common are exporting directly to foreign countries and indirectly exporting by selling to other exporting firms. SMEs can also benefit from international markets by sourcing foreign goods, services, inputs, intellectual property and technology. Although a rarer practice, SMEs can also engage in joint ventures with foreign firms in their domestic market or in a foreign market. They can also participate in global value chains by focusing on specific segments of the production of a set of goods and services, for instance, by supplying a foreign firm in the host market with domestic inputs (goods or services).

Despite their importance in domestic economies, SMEs are generally under-represented in international markets. For example, in OECD countries SME contributions to overall exports is between 20-40% (OECD, 2019[3]). Those figures are lower in the MENA region: for example, in Egypt, a large and relatively open economy, only 6% of SMEs export and just 1.8% of enterprises with less than 20 employees are exporters (Helmy Elsaid et al., 2014[4]). Those figures are likely to be significantly lower if all enterprises, including informal ones, are considered.

The low levels of participation of SMEs in international markets are explained, to an important extent, by the inherent characteristics of small businesses. For example, SMEs concentrate in non-tradable sectors such as retail trade, construction and services (e.g. hairdressers, repair shops, restaurants, etc.). SMEs are also largely absent in internationally oriented sectors where scale matters and where large investments in tangible assets are the norm (e.g. commodities, heavy industry, large-scale manufacturing, etc.). There are other factors acting as barriers for SMEs with potential and drive to internationalise. Those include “internal” barriers such as low capacity to access information (e.g. on foreign markets) and lack of managerial and technical knowledge and skills (e.g. languages, finance, cultural norms, etc.). They also include “external” barriers such as burdensome regulatory procedures (in home and foreign markets), poor infrastructure, difficult business environments (e.g. corruption, weak property rights, etc.), among others.

The international fragmentation of production processes for certain goods reflected in GVCs, and other trends such as the increasing importance of digital technologies in the economy represent an opportunity to boost SME access to international knowledge and markets. Promoting the establishment of business linkages between (usually large and multinational) foreign firms established in a country and SMEs is an important tool to boost the participation of domestic actors in the global economy. It is also a practical alternative to mitigate the external and internal barriers to SME internationalisation by providing small business with direct access to international partners, knowledge and technology. Those SME-MNE linkages can take various forms of business partnerships, for example:

Supply/manufacturing agreements, whereby an SME or group of SMEs provide goods and services to a foreign firm or MNE. These agreements do not involve directly exporting to a foreign market but rather supplying a MNE established domestically. Conversely, supply agreements also occur when SMEs buy goods or inputs from foreign MNEs based in their home country (OECD-UNIDO, 2019[5]).

Licensing agreements, whereby an SME or group of SMEs acquire a license from an MNE to produce and sell goods under a brand or trademark or use patented technology.

R&D agreements whereby the MNE and SMEs undertake joint research and development of a product, service or production method.

All MENA economies participate in GVCs but not in the same way

The organisation of international production, trade and investment within GVCs has become a dominant feature of globalisation. Participation in GVCs can offer new opportunities to integrate in the global economy by allowing firms to join global production networks rather than having to build their own from scratch. Firms participating in GVCs can use international, instead of national, knowledge, resources and inputs in their production. As a result, economic activity has become more interconnected and complex (Kowalski et al., 2015[6]). Factors such as the level of development, geographical location, stability and the policy environment shape countries’ participation in GVCs. Sectoral specialisation is another key factor.

In the MENA region, firms’ participation in GVCs has been promoted as a key way to achieve higher export diversification and eventually more sustainable and inclusive development models. The impact on sustainable development has been limited, however, reflecting countries’ different compositions of export baskets or positioning in supply chains. For instance, Algeria and Libya participate in GVCs mainly because they are large exporters of commodities (Box 8.1). As a result, they need to use very few imported inputs in their exports, whereas countries with advanced levels of industrialisation and services rely highly on imported inputs for exports (e.g. OECD area). Large countries such as Egypt also rely on commodity exports to engage in GVCs but they have a higher domestic capacity for producing specific inputs and diversify their exports, such as in food supply, petrochemicals, electrical machinery and textiles.

Tunisia and Morocco participate in GVCs as light manufacturers and firms in the two countries use significant amounts of manufactured imports in their own exports. Besides textiles and garments, both economies are well embedded in supply chains of electrical, electronic, and to a lesser extent, ICT sectors that serve the EU market. Morocco has also successfully integrated into the global automotive value chain. Jordan and Lebanon are smaller countries that depend on imports of intermediate goods and services, notably in the garment and pharmaceutical supply chains in Jordan and in the processed food sector in Lebanon. But few countries use Jordanian and Lebanese goods and services as inputs into their own exports, thereby limiting the value-added of both countries’ exports.

MNEs can help countries plug into higher-value added segments of the supply chain

Along with trade, the “GVC revolution” has been driven largely by MNEs through FDI. FDI is not only an important channel for exchanging capital across countries, it is also an essential vehicle for the international flow of goods, services, and knowledge and serves to link and organise production across countries. With the establishment of foreign affiliates of MNEs, investment can play a key role in fostering the recipient’s country participation in GVCs. FDI motives shape the type and extent of GVC participation. FDI directed at establishing an export processing facility boosts backward linkages: MNEs’ affiliates import large shares of intermediate products that are used in production and export (Kowalski et al., 2015[6]).

In most of the eight MENA focus economies, and as described in Chapter 2, FDI is concentrated in capital-intensive sectors (natural resources, real estate and construction) or light manufacturing activities with low propensity to promote transfers of technology and managerial expertise, making it more challenging for the region to benefit from participation in GVCs.

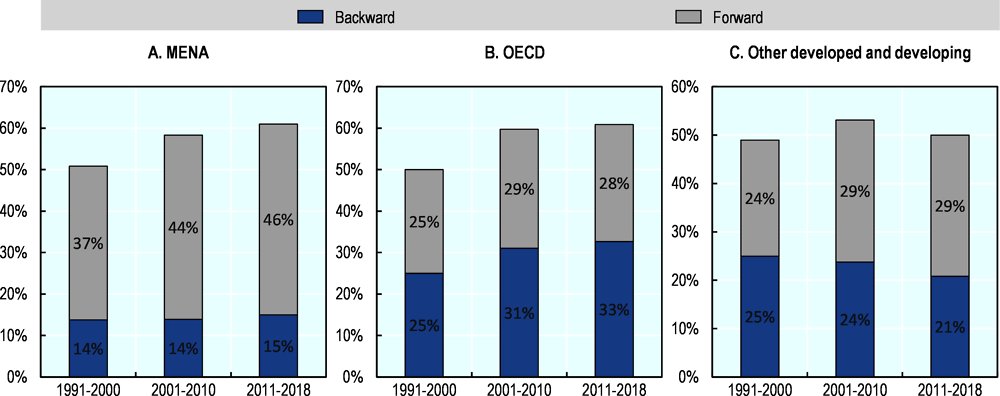

GVCs reflect the foreign and domestic value added of a country’s exports. For example, in a given set of products such as consumer electronics (TVs, mobile phones, etc.), some countries specialise in the R&D and design stages of the devices, others focus on the assembly of parts (which in turn can be produced in several countries), and yet others host logistics, marketing and aftersales services. GVC participation can be decomposed into backward participation and forward participation:

Backward participation, or foreign value added as a share of exports, indicates to what extent countries’ and companies’ exports depend on imported products. For example, in the case of consumer electronics, a country can specialise in the assembly of the products with imported components, and with the implied imported R&D and design of those products. That country would have high backward participation and a low share of vale added in GVCs. Along those lines, a country that produces raw materials such as the minerals used in the electronics components would have low backward participation (minerals do not require high levels of imports) and also low shares of value added in the consumer electronics GVCs.

Forward participation, or the exported value added incorporated in third-country exports, is the extent of relationships with foreign downstream buyers. Using the same example of the consumer-electronics value chain, countries specialising in the R&D and design stages of the value chain have a high forward and high value added participation with respect to those countries specialising in assembly.

Exports of commodities by MENA focus economies are behind the high forward participation rates of the region compared with OECD and other developed and developing economies (Figure 8.1). Commodities are used in downstream production processes that typically cross several borders. Relatively low backward participation in GVCs reflects MENA countries’ limited use of imported inputs in their manufactured exports, whereas other developed and developing countries rely more on imported inputs for exports.

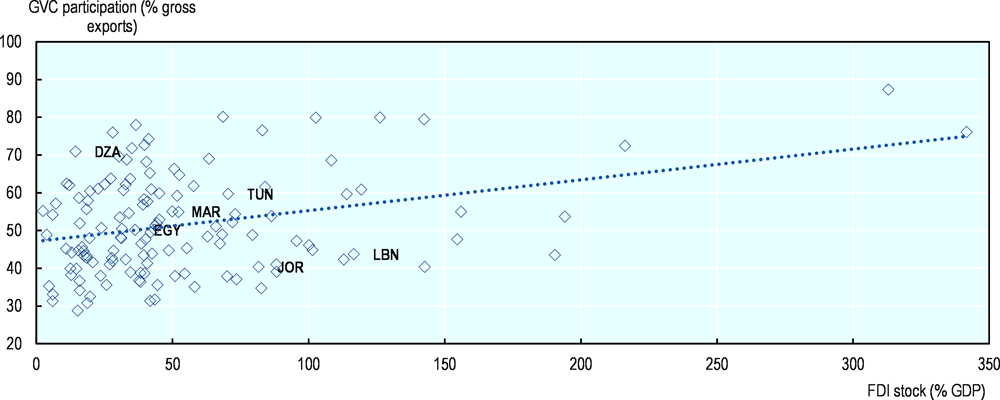

Jordan and Lebanon are the MENA countries that participate the least in GVCs despite high FDI stock-to-GDP ratio (Figure 8.2). In Jordan, the Qualified Economic Zone (QIZ) attracted large Asian textile MNEs that rapidly turned a country without a clothing industry into a leading regional garment exporter. However, the affiliates of MNEs did not invest in upstream segments of the textile industry in Jordan (e.g. R&D or clothing design), thereby limiting the value-added generated from exports and their sustainability (Azmeh and Nadvi, 2014[7]).

Tunisia, Morocco and, to a lesser extent, Egypt combine both higher FDI stock-to-GDP and GVC participation ratios in comparison with other countries. Besides the presence of an industrial base, generous tax incentives and trade facilitation measures given to foreign exporting firms, such as the offshore regime in Tunisia or free zones in Egypt, has driven participation in GVCs. Territorial disparities and high unemployment among young people and higher education graduates have nonetheless highlighted the limited impact of those countries’ participation in GVCs. Both Morocco and Tunisia report, for instance, a low demand for local skills in their GVC exports (UNECA, 2016[8]).

MNE affiliates in Algeria and Libya increase domestic value-added in exports as they focus on processing natural resources but help only to a small extent to plug these countries into new segments of the supply chain. Overall, the sectors that receive the bulk of FDI in these countries and the wider MENA region, e.g. real estate and petroleum activities, are also those with the least segmented or shorter supply chains, i.e. few intermediate inputs are needed to produce the final good.

While critical, there is little evidence on the use of services in GVCs in the MENA region. With increasingly digitalised GVCs, access to high quality services – particularly telecommunications, transport and specialised business services – is becoming all the more important. Almost half of value-added inputs to exports are service-sector activities, as most manufacturers require services for their exports (UNCTAD, 2013[9]). In addition, a significant part of the international production networks of MNEs are geared towards providing services inputs, as indicated by the fact that more than 60% of global FDI stock is in services activities. Evidence for Morocco and Tunisia, which are part of the OECD Trade-in Value Added Database (OECD TiVA), indicates that both countries use fewer services inputs in manufacturing GVCs in comparison with OECD member states.

GVC disruptions due to the Covid-19 pandemic has created challenges and opportunities for MENA economies (Box 8.2). Those disruptions affect MNE decisions to reorganise the geographical and sectoral spread of their production activities, providing possible opportunities for the MENA region. The region should seize potential opportunities if European MNEs seek to shorten their supply chains and reduce the distance between suppliers and clients (nearshoring). Similarly, some firms may diversify their supply networks to increase resilience to shocks, which will involve divestments from some locations but expansion in others.

Covid-19 has re-ignited the debate about the supply chain risks associated with international production, although there is no evidence that countries would have fared better in the absence of GVCs, as lockdowns have also affected the supply of domestic inputs. The pandemic has revealed both the strengths and weaknesses of GVCs, including for the supply of essential products. Past experience shows that global production networks can be disrupted and play a role in the propagation of shocks across countries and sectors. But they also help firms and countries to recover faster.

Ensuring sufficient supply of goods and services needed to fight the pandemic has been the immediate priority for policymakers. Pharmaceuticals, medical supplies and equipment, and healthcare provision depend much more on GVCs and international investment than in the past. Immediate urgencies at home are sometimes at odds with global objectives and the smooth functioning of GVCs, as suggested by the spread of export curbs on medical supplies introduced by numerous governments in Spring of 2020, including by MENA countries. These distortionary measures should remain temporary tools to mitigate the crisis, not permanent fixtures in the world trade system.

GVC disruptions have adverse impacts on the MENA region but also offer opportunities. Thanks to their proximity and trade ties with Europe, countries in MENA may benefit from the restructuring efforts of European MNEs, which may reconsider their dependence on Chinese manufacturing and shorten supply chains through nearshoring or onshoring. For instance, automotive manufacturers could create stronger business linkages in the region, as these manufacturers may aim to produce closer to their primary markets by investing in countries with favourable industry policies and low input costs.

In Morocco, for instance, both Renault and PSA dominate the auto manufacturing industry with well-developed supply chains throughout the country. In April 2020, Renault announced plans to exit the Chinese passenger car segment and relocate some production, along with its aim to increase its localisation rate (the percentage of value-added that is sourced locally) in Morocco from 50% in 2018 to 80% at the end of 2020. The entire value chain of Groupe PSA Kenitra’s plant is in Africa, particularly in Morocco where its ecosystem involves a network of 62 Moroccan suppliers. In Egypt, Fiat Chrysler Automobiles and PSA are also producing vehicles either through partnerships or contracts with domestic companies and are also expected to create stronger regional supply.

MENA governments and private sector associations can support firms’ efforts to build more resilient GVCs by collecting and sharing information on potential concentration and bottlenecks upstream, developing stress tests for essential supply chains, and creating a conducive regulatory environment that is not a source of additional, policy-related, uncertainty. Governments and the private sector can also work with SMEs to assess potential opportunities to participate directly or indirectly in relocating GVCs to the region in the aftermath of the crisis.

Source: (OECD, 2020[10]); (OECD, 2020[11]); (OECD, 2020[12])

Integrating SMEs in GVCs: the extent of linkages with foreign investors

Leveraging FDI to integrate SMEs in GVCs can be an opportunity for MENA countries to adopt a more inclusive development trajectory. Given the performance premium of foreign firms over domestic ones (see Chapter 2), supply chain relationships should positively support SMEs, depending on the extent and intensity of linkages, absorptive capacity of SMEs and the sector of activity. Local sourcing of MNEs, when not the result of restrictive trade policies such as high tariffs or local content requirements, can generate optimal demand for host economy firms and lead to productivity-enhancing knowledge spillovers. It can enable SMEs in the MENA region to export, develop managerial skills, upgrade products or services to international norms, innovate, reduce costs, improve working conditions, or produce more sustainably.

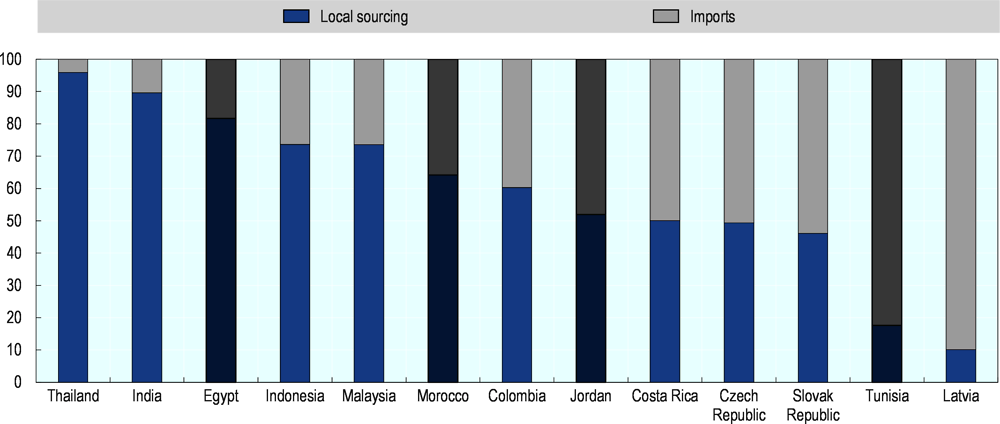

Manufacturing MNEs’ sourcing of local inputs is relatively high in the region

Foreign manufacturers present in some of the MENA focus economies source significantly from local producers (Figure 8.3).1 MNE affiliates in Egypt, Morocco and Jordan source more than half of their inputs from firms (both domestic and foreign) that produce locally. MNEs in Tunisia rely more on imported inputs. This mirrors, to some extent, the various ways MENA countries participate in GVCs – Egyptian exports rely less on foreign inputs than other MENA exporters do. Overall, linkages between manufacturing MNEs and local firms mostly involve sourcing of low-skilled inputs, rather than contractual arrangements for R&D or other upstream activities.

Differences in the sectoral structure of the economy, positioning within specific value chains, and policy factors can explain variation across countries. For instance, significant local sourcing can reflect a high local capacity for producing specific inputs, which may explain the higher share of local sourcing by foreign manufacturers in countries like Thailand, where advanced local supplier capabilities exist in some key sectors such as motor vehicles and machinery and equipment (OECD-UNIDO, 2019[5]).

Different shares of local sourcing by foreign investors can also be the result of restrictions to imports or legal and regulatory requirements to source from local and foreign suppliers. In Egypt, for instance, local content requirements (LCRs) in specific sectors like in the automotive industry (45% of localised content) or in Free Zones, combined with lengthy procedures on imports, result in higher shares of local sourcing by foreign firms (OECD, 2020[13]). In Tunisia, export-only firms belonging to the offshore regime have little sourcing or subcontracting activities with domestic, onshore firms due to taxation and burdensome administrative custom procedures (Box 8.3). The limited sourcing reduces potential spillovers from the offshore regime to the wider Tunisian economy.

The progress of Tunisia in GVCs is linked to foreign companies in the offshore regime – they account for nearly half of all offshore enterprises. Offshore companies are exempt from customs duties on imports and exports, benefiting from a reduced tax rate and especially simplified administrative procedures and better access to transport services. They can sell 30% of their turnover on the local market with prior payment of customs duties.

Opportunities for spillovers or technological externalities related to FDI are limited in the Tunisian manufacturing sector. Foreign offshore companies have few economic ties with the rest of the economy. Taxation, administrative and customs procedures constitute a barrier to the development of subcontracting relationships between foreign and local businesses and, more generally, to the training and technology transfer effects of offshore foreign companies on the Tunisian economy.

Offshore firms can get supplies on the local market and, in this case, are exempt from VAT. In practice, local sourcing is limited. Similarly, an onshore firm selling products to an offshore company should be able to be reimbursed for the VAT paid on its intermediate consumption. In practice, tax authorities reimburse businesses once a year, creating cash flow problems for some firms, especially small ones. In addition, requests for VAT credit lead sometimes to control checks by tax officials, which often discourage subcontracting.

Source: (Joumard, Dhaoui and Morgavi, 2018[14])

In the majority of MENA focus economies, the World Bank Enterprise Surveys indicate that MNEs affiliates in manufacturing are concentrated in the food and garment sectors. Accordingly, the shares presented in Figure 8.3 often represent foreign firms’ local sourcing practices in these sectors. In Jordan, in addition to the food and garment sectors, MNE affiliates in the pharmaceutical and fabricated metals sectors purchase significant shares of intermediate inputs produced locally. In Egypt, foreign investors in manufacturing appear to have a diversified portfolio, from low-value added industries, such as food processing, to machinery production, a sector in which foreign manufacturers purchases of locally produced intermediates is relatively high.2

MNE affiliates are a key source of revenue for local suppliers but not necessarily SMEs

In terms of market size, MNE affiliates can represent a large source of revenue for local suppliers. This is the case in Morocco and Jordan, where foreign firms buy more than half of the locally produced intermediates (Figure 8.4, panel A). But local sourcing in the two countries is mostly driven by foreign firms supplying intermediates to other foreign firms hosted in the same country (Figure 8.4, panel B). This is often observed when lead firms establish in host economies and large international first-tier suppliers –companies that provide parts and materials directly to a manufacturer of goods – locate affiliates in their proximity (OECD-UNIDO, 2019[5]). This could be occurring in higher-tech industries such as the automotive sector in Morocco or the pharmaceutical sector in Jordan, and where domestic SMEs face challenges in producing goods that are up to the foreign firms’ international standards. The purchase of local intermediate goods by foreign manufacturers matters less for producers in Egypt and Tunisia than in other countries. Nonetheless, SMEs3 and large firms jointly account for almost all intermediates supplied to foreign MNEs in the two countries, in sharp contrast with what is observed in Morocco and Jordan.

A conducive investment and business environment is a crucial ingredient for anchoring foreign investors into the domestic economy through deep linkages with SMEs. It is also essential to materialise the latent development gains from GVCs, beyond the more immediate objective of allowing domestic firms to participate in global production networks without developing the full range of capabilities required to produce a product or service. Factors such as trade openness, well-functioning finance supply and markets, intellectual property rights protection, a conducive innovation infrastructure, flexible labour market policies and competition rules that facilitate market entry and exit, need to be in place for countries to enable SME-MNE linkages and enhance knowledge and technology diffusion. This section focuses on two business climate areas that are priorities for enabling business linkages in MENA focus economies: addressing restrictions to FDI in sectors that are vital for GVCs and guaranteeing contract enforcement.

Opening up to FDI in services can increase the potential for MNE-SME linkages

Legal and regulatory restrictions on FDI limit market access and thereby reduce the potential for linkages between foreign investors participating in GVCs and domestic enterprises, including SMEs. As such, re-thinking FDI restrictions and reforming them when relevant is a basic step to promote stronger linkages between the global and the domestic economy (OECD-UNIDO, 2019[5]). The pace of investment liberalisation in MENA countries has contributed to some extent to attracting FDI to the region (Chapter 4). For example, the recent decision of Algeria to ease foreign ownership restrictions may help the country attract more FDI in the manufacturing sector and thus support export diversification.

MENA economies in general display moderate levels of FDI restrictions in the manufacturing sector, which is an important element in GVCs. Yet, compared with OECD countries – and with the exception of Morocco – FDI restrictions remain high in services sectors particularly vital to GVCs, namely wholesale and retail, transport, and financial and business services (see Chapters 4 and 9). Similarly, while most countries have made progress in removing barriers to goods trade, restrictions in services trade are still high (Karam and Zaki, 2015[15]). Along with trade barriers, FDI restrictions in services may impede the deployment of foreign investment in sectors such as infrastructure and logistics that are crucial for further GVC participation and strengthened business linkages (it is worth noting that construction is also an activity with high barriers to FDI in the region).

Further openness could help raise efficiency (and reduce input costs) in sectors dominated by large state monopolies and improve the quality and availability of services. Openness in services may also be particularly important for the competitiveness and productivity of small manufacturers throughout the MENA region. SMEs often rely more on high quality backbone services and other services provided by upstream, external providers.

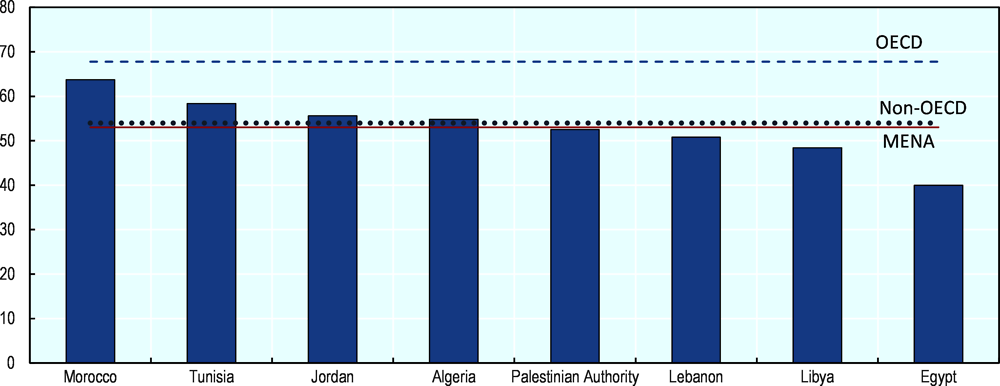

Guarantees of legal security and investor protection can strengthen linkages

MNEs, when contemplating engaging in business linkages with domestic firms, including SMEs, need to be reassured that their business interests, such as property rights will be protected throughout the lifespan of the contracts. Investors take into consideration the transparency and predictability of policies, as well as guarantees of legal security. Well-designed investment, bankruptcy and intellectual property rights laws and regulations are crucial to strengthen investor protection and contract enforcement. Since they increase confidence among parties, they also facilitate the establishment of business linkages in the form of partnerships, contractual arrangements, technology licenses, franchises, and research collaborations.

MENA economies have taken steps to improve regulation and facilitate the upscaling and development of linkages between MNEs and SMEs. Most of the focus economies have introduced changes in their legal and regulatory investment regime and have made sustained efforts to move closer to achieving a more transparent and enabling investment climate, with modern dispute settlement provisions and strong guarantees of property rights protection (see Chapters 3 and 5).

The effectiveness of contract enforcement and dispute resolution in business is fundamental for SMEs to participate in GVCs, and good enforcement procedures are indeed associated with higher levels of business linkages (Amendolagine et al., 2019[16]) (OECD-UNIDO, 2019[5]). In the MENA region, albeit the ease of enforcing contracts varies widely across economies, all of them are below the OECD average (Figure 8.5). Enforcing contracts is harder in Egypt, Lebanon, Libya and the Palestinian Authority than in the average non-OECD economy. When enforcing contracts is cumbersome or when contract disputes cannot be resolved in a timely and cost-effective manner, foreign investors may refrain from engaging with local businesses. Therefore, guaranteeing legal security not only promotes linkages between foreign investors and local SMEs but also makes technology transfers more likely.

Modernising dispute settlement mechanisms is also key to supporting an enabling environment for foreign investment. Measures can include adopting e-justice systems to facilitate the management of the judiciary caseload, and organising the judicial system along key areas of specialisation, for example by creating specialised commercial courts, intellectual property courts, and land courts. Meanwhile, alternative dispute resolution mechanisms, including arbitration, mediation and conciliation, are increasingly used for resolving commercial and investment disputes. International investment agreements (IIAs) may provide an additional layer of security to covered investors, including by offering recourse to international investment arbitration to resolve investor-state disputes (See Chapter 5 on Investment Disputes and Management).4

Broadly speaking, linkages and partnerships among enterprises are initiatives to create opportunities and synergies, and address common problems. For example, SMEs can undertake joint actions to increase the quality of their offer, achieve economies of scale and scope by creating consortia, stimulate the supply of business support services and promote technology transfers, among others. Linkages and partnerships can be especially important for SMEs given their limited resources. As noted earlier in this chapter, when undertaken between foreign and local firms, partnerships and linkages can also enhance the positive impacts of FDI, such as increased business opportunities and employment in domestic enterprises.

There are a number of concrete actions that government agencies such as Investment Promotion Agencies (IPAs) and SME Agencies, private sector associations, MNEs, business development services providers and many other actors can take to foster the participation of SMEs in global value chains through linkages with MNEs based in their domestic markets. Those actions include disseminating information among SMEs and MNEs of opportunities for business linkages, the creation of databases of products, suppliers and buyers, programmes for the formation of SME consortia to supply large orders, supplier development programmes and several other initiatives. Actions can also include support to SMEs and MNEs to engage in responsible business conduct, and helping small businesses to take advantage of other tools such as participating in special economic zones and leveraging the financial and networking resources of diaspora investors. This section provides an overview of those actions and actors and their relevance to the MENA region.

Reinforcing business associations and enterprise networks

Enterprise networks and business associations constitute an important tool to disseminate information about business opportunities in GVCs through SME-MNE linkages. For instance, international or binational chambers of commerce are present in several MENA countries and can help explore and establish business partnerships between domestic SMEs and foreign firms. For example, in Egypt there a number of initiatives to promote partnerships between Egyptian and foreign enterprises, notably joint business associations with France, Germany, Italy, the United Kingdom and the United States. The aim of those initiatives is to foster industrial investments, technology transfers and the development of human resources, among other actions (OECD/The European Commission/ETF, 2014[17]). It is unclear, however, to what extent those and other initiatives have been effective at integrating SMEs in GVCs through partnerships with MNEs. Furthermore, although there are abundant business associations, especially at the national and sub-national levels across the MENA region, it is not clear to what extent those organisations are representative of the interests of SMEs (OECD/European Union/ETF, 2018[18]).

Transnational or multilateral initiatives to promote business partnerships can also prove useful to establishing SME-MNE linkages in the MENA region. For example, the Enterprise Europe Network (EEN) is a multinational initiative sponsored by the EU Programme for the Competitiveness of SMEs (COSME) and bringing together chambers of commerce and industry, technology poles, innovation support organisations, universities and research institutes, regional development organisations, and other groups. The EEN operates in over 60 countries and coordinates more than 3 000 experts and 600 member organisations providing business development services to SMEs, in particular in the areas of innovation, international growth and international partnerships. Of the MENA economies covered in this report, only Egypt, Jordan and Tunisia participate in the EEN.5 The EEN provides an extensive database of business opportunities, including but not limited to SME-MNE linkages – at the time of writing, no SME-MNE specific opportunities were found in MENA economies, although there were many partnership possibilities for accessing foreign technologies and brands.6

Other initiatives promoting Euro-Mediterranean economic co-operation can also provide useful platforms for strengthening SME-MNE linkages, particularly given the important presence of European direct investment in several economies in the MENA region. For example, ANIMA Investment Network promotes the development of investment, business partnerships and clusters in Europe, the Middle East and Africa to promote innovation, entrepreneurship and the internationalisation of enterprises (OECD/The European Commission/ETF, 2014[17]). This network brings together 70 organisations, including public and private and business development services providers to support SMEs and entrepreneurs and to promote the development of business support organisations in the Southern Mediterranean.7

Providing business development services for SMEs to engage in linkages with MNEs

Given their small resource base, SMEs rely more on services supplied by external providers than larger firms do. Those services range from supporting day-to-day business functions (e.g. accounting, legal, logistics, human resource management, etc.) to developing longer-term and strategic capabilities (e.g. management counsel, human resource development, access to technology, access to markets, etc.). The first category of services (business support) is important since it allows SMEs to focus on their core competences and externally contract functions that the firm has no capacity or strategic wish to perform. The second category (business development services) is essential for SMEs to build new competencies and achieve longer-term objectives such as increased sales, productivity, reaching new markets, and/or developing new products, services or processes.

Business development services (BDS) can provide important means to help small businesses to identify and engage in linkages with foreign firms in the context of GVCs. The markets for BDS, however, differ importantly among MENA economies in terms of diversity of services available and actors providing them. For example, Jordan has a relatively diverse BDS market, with public and private actors active in the provision of support to SMEs. These include the SME agency, JEDCO (Jordan Enterprise Development Corporation) which provides tailor-made support to firms with growth potential to undertake business diagnostics, address barriers to expansion and obtain coaching. Another actor in Jordan is the Local Enterprise Support Project (LENS), implemented by the US Agency for International Development (USAID) to encourage the growth of small businesses in target sectors, the development of private or non-government BDS providers, and to help SMEs to connect with industry associations, chambers of commerce and BDS providers. In addition, other public and private actors also implement a number of BDS programmes (OECD, 2019[19]).8

Other economies with diverse BDS markets include Morocco. The country relies on a solid presence of public and private actors and implements a number of flagship initiatives to provide strategic direction to economic development policy. At the other end of the spectrum is Algeria, with a less diversified BDS market and with fewer flagship initiatives mostly led by the public sector, reflecting lower levels of private sector development in the country (OECD/European Union/ETF, 2018[18]).9

The diversity of BDS and their suppliers in several MENA countries has not been decoded into comprehensive and structured databases allowing SMEs and entrepreneurs to search and filter specific programmes responding to their potential needs – including opportunities to establish SME-MNE linkages to participate in international value chains. In other terms, BDS markets remain fragmented into a wide but disconnected series of offers, hence limiting the reach and impact of such measures. To address such fragmentation, MENA governments and private sector actors could establish electronic BDS databases where suppliers and users could upload and consult available support.10

Furthermore, MENA countries could also draw inspiration from some BDS support schemes used to promote the participation of SMEs in public procurement, such as the electronic dissemination of procurement opportunities by MNEs in the domestic market (akin to the publication of public procurement opportunities in e-procurement platforms). This could be done by public actors such as SME agencies or IPAs, or by private associations, such as chambers of industry and commerce, or associations of SMEs and MNEs. Electronic portals could include up-to-date procurement opportunities by MNEs and electronic registries of suppliers.

Other BDS programmes used in public procurement could also prove valuable for SME-MNE linkages, by helping small suppliers to form consortia to source large orders of goods and services, and comply with certain standards and increase quality. In addition, measures to ensure that payments by MNEs to supplying SMEs are made in time, could also prove essential in avoiding cash flow stress in small firms and a de facto financing of larger firms by SMEs.

Unfortunately, most MENA governments do not implement any of those procurement programmes. However, SME-MNE linkages could provide an opportunity to develop such practices first in the context of GVCs and then extend them to public procurement markets.

Investment promotion agencies can also use a variety of tools to connect businesses

National investment promotion agencies (IPAs) can also use policy tools such as targeted supplier development programmes, matchmaking services and high-quality supplier databases. Training and supplier development initiatives offer funding to MNEs that support local SMEs in acquiring skills or technology, or in meeting specific requirements. Other possible initiatives include the creation of SME or business development centres to help SMEs upgrade their capabilities.

IPAs are often the lead agency for implementing business linkages programmes or share that responsibility with other institutions, such as ministries of industry, trade and innovation, or SMEs agencies and BDS providers. Often, linkages programmes target priority sectors that IPAs promote. MENA IPAs, along with other government agencies and private sector associations, could further contribute to the formulation of an adequate set of linkage policies and to the implementation of supplier development programmes (see Chapter 6 on investment promotion and facilitation strategies).

MENA IPAs have at their disposal some tools to promote business linkages. For instance, all agencies offer foreign investors matchmaking services with local suppliers. They also all have a local supplier database, or rely on one run by another government agency, that allows MNE affiliates to connect with relevant suppliers. But tools to promote linkages are often implemented on an ad hoc basis, and are not part of a specific, more explicit, linkages programme. IPAs that wish to be more active in supporting the creation and forging of linkages may need to have a clear mandate to provide investors with accurate and timely information on local suppliers and SME partners, and ensure co-ordination with ministries and other agencies (OECD, 2019[20]).

The quality of supplier databases differs across MENA economies. For instance, not all MENA IPAs are equipped with databases that list certifications held by local suppliers. Databases are also not publicly available online, which requires potential foreign investors to contact the IPA to enquire about the existence and features of local suppliers. In Tunisia, the foreign investment promotion agency, FIPA, provides matchmaking services but relies on the local supplier database of another agency, APII, the Agency for the Promotion of Industry and Innovation. The database is available online, includes both companies in manufacturing and services and provides information at the product level. It also lists certified companies, i.e. businesses with a specific quality certification.

Some MENA IPAs offer capacity building for local suppliers (Algeria, Lebanon, Palestinian Authority, and Tunisia). These IPAs have in common a mandate to promote domestic investment in addition to foreign investment. A minority of MENA IPAs provide assistance in recruiting and training programmes for local staff, which is similar to OECD IPAs (OECD, 2018[21]). Training local staff is often carried out by other agencies, such as SME development agencies, whether in the MENA region or elsewhere. Co-ordination across agencies is thus crucial to ensure good implementation of linkages policies.

An example of an IPA that has managed to promote business linkages is Czech Invest, notably thanks to the Supplier Development Programme, which offered an online access to a database of local suppliers in specific sectors and matchmaking and negotiation services (Box 8.4). Other effective programmes include Thailand’s Board of Investment Unit for Industrial Linkage Development (BUILD), which illustrates that linkage promotion needs to be part of a longer-term development plan that is coordinated across multiple actors. BUILD flexibly and informally coordinates linkages activities with other government bodies, the private sector and academic institutions (OECD-UNIDO, 2019[5]).

Czech Invest launched the Supplier Development Program in 1999, with a focus on electronics, the Czech Republic’s fastest growing sector and its second largest FDI sector after automotive. The programme aimed to boost Czech suppliers’ competitiveness but also improve the communication between local companies and MNEs. It consisted of targeting specific local businesses to participate in training and technical assistance programmes to heighten their product quality and improve their absorptive capacity, providing matchmaking services by setting up meetings between MNEs and selected producers and providing assistance during negotiations. The agency also provided financial intermediation for businesses expansion, notably by giving an affidavit to a lending bank or when the MNE as a partner can guarantee the contract for supplies.

The Czech IPA also operates an online database of local suppliers to ease communication between foreign investors and suppliers. The database serves as an effective tool for identifying and categorising suppliers in the Czech Republic and as a means of clearly presenting individual industrial sectors. The database is intended primarily for foreign investors entering the Czech Republic and those that are already operating there, as well as for other foreign and domestic companies that are interested in obtaining supplies from the Czech Republic. It also allows searches for suppliers according to first, second and third tier.

Promote safe business linkages through responsible business conduct

RBC principles and standards set out an expectation that all businesses contribute to sustainable development, and avoid and address adverse impacts of their operations. This entails integrating and considering environmental and social issues within core business activities, including in the supply chain and business relationships (see Chapter 10). MNEs increasingly base their decisions about where to invest on the ability to ensure predictable and reliable supply chains, capable of delivering effectively at each stage. Costs of delays due to, for example, labour unrests or environmental damage, can be substantial. Ensuring efficiency of supply chains has become even more relevant in the aftermath of the Covid-19 outbreak as they have become more vulnerable to disruptions generated by the pandemic.

Clearly communicating RBC priorities and expectations, including to the private sector, would help promote linkages with MNEs, and hence maximise the development impact of FDI in the MENA region. Suppliers of MNEs may find that following RBC principles and standards gives them an advantage over businesses that do not, as they are able to address concerns that may come up in due diligence efforts of the MNE. Governments could also use RBC as a tool for MNE-SME matchmaking. RBC expectations should be included in FDI facilitation efforts and may help attract MNEs that are more inclined to source locally. For instance, one element of supplier databases and matchmaking events could be RBC. Governments could also include RBC principles in industry-specific training programmes as a way to build absorptive capacity of domestic firms. This could encompass supporting cost-sharing efforts within and among industries for specific due diligence tasks, participation in initiatives on responsible supply chain management and cooperation between industry members who share suppliers.

Smart incentive regimes and zone-based policies can support deeper linkages

MENA economies widely use tax and non-tax incentives to promote and encourage investment activities that enable economic and social spillovers (see Chapter 7). They are also one of the tools available to governments to influence MNEs’ sourcing decisions, and can consist of tax deductions to subtract certain expenses or reward firms for training their local suppliers (e.g. on training programmes, R&D activities, capacity building of SMEs, and environmental protection). Tax incentives (particularly tax holidays) can impose significant fiscal costs on the countries using them. Targeted approaches should be preferred

Most MENA economies target wide sectors or regions, either via special incentive provisions for less developed regions or additional zone-based incentives. Only a few countries, such as Morocco, have a more targeted approach to incentives, with specific incentives to promote skills, R&D, and high-tech activities. Outside of the region, several countries use targeted incentives to support SME engagement with foreign companies. For instance, projects in Thailand are granted expenditure deduction from taxable income incurred for spending on the development of local suppliers through training and technical assistance. More broadly, incentives on linkages could include the expenditures of lead firms in assisting and auditing their suppliers to adhere with the company’s quality, environmental, health and safety standards (Galli, 2017[22]).

MENA economies participation in GVCs is in part driven by the setup of exclusive zone-based regimes (e.g. Tangier free zone in Morocco, the Suez Canal Special Economic Zone in Egypt) or special exporting regimes (offshore regime in Tunisia, the QIZs in Jordan). Often, the objectives of these regimes is spurring new investments and trade, creating jobs and fostering economic opportunities. While such regimes have managed to attract investment and foster trade, notably by offering generous tax incentives and adequate services, their positive impact and spillovers on the local economy is not clear-cut. For example, the zone of Tangier, which attracted global leaders in the automotive and aeronautic sector, only partially succeeded in connecting local SMEs to zone producers and to upgrade their capabilities to plug in new segments of GVCs (IFC, 2019[23]).

To promote linkages, some governments exempt MNEs in exclusive regimes from paying value added tax (VAT) on locally purchased inputs. VAT exemptions can help compensate for possible cost disadvantages of local products compared to foreign supply. It can also level the playing field between local suppliers and imports in cases where imports by MNEs are also exempt from VAT (Sabha, Liu and Douw, 2020[24]). Some MENA economies introduced such VAT incentives but their expected impact on linkages has not always materialised. For instance, in Tunisia, firms with an exporting status (offshore regime) are exempt from VAT on local supplies. Similarly, an onshore firm selling products to an offshore company can be reimbursed for the VAT paid on its intermediate consumption. In practice, few linkages exist between the two, notably due to cumbersome administrative procedures (Box 8.3).

Non-tax incentives can be as important as tax incentives to promote linkages, if not more so when the regulatory environment is complex. For instance, Egypt eased the regulatory and administrative procedures on local firms that supply businesses in zones, which have duty-free regimes. Although products and services sold to these zones are treated as exports and therefore subject to the same trade rules, some administrative incentives are given to local suppliers in specific sectors. These suppliers do not need to obtain the approval from the trade control authority to source some goods that are usually subject to quality control (OECD, 2020[13]).

Linkages policy is framed in some MENA economies as a local-content requirement (LCR), which sometimes can discourage foreign investors and potentially confine relationships to low-skilled activities to meet the requirements. Incentives to forge proactively meaningful relationships with local suppliers can be a better alternative for host countries to reap the sustainable development benefits of FDI (Box 8.5). For instance, in Jordan, the government envisaged setting a LCR on renewable energy investment, which would have increased the cost of inputs for downstream power producers (OECD, 2016[25]). As an alternative, the government could provide tax deduction to power producers financing the upgrading of local suppliers so that they can produce renewable energy components that are not available locally.

Local content requirements may discourage FDI by establishing hard conditions to achieve local requirements that restrain competition from imports, which might contribute to higher production costs and ultimately higher prices to downstream industries and consumers. Potential short-term gains in the targeted industry can therefore act as a drain on the rest of the economy. The costs in terms of forgone investments is not necessarily compensated by improved local development outcomes, if any, such as increased employment, investment and technology transfer (OECD, 2020[26]).

The literature on the potential effects of LCR is extensive, and while there may be situations where these policies could potentially increase domestic welfare depending on market characteristics (e.g. potential learning and technological spillovers, economies of scale etc.), the overall evidence suggests that they tend to lead to a suboptimal allocation of resources (Stone, Messent and Flaig, 2015[27]). The inefficiencies arising in other sectors due to the LCR can also reduce job growth, undermining the original goals for imposing the LCR. They can also cause a decline in trade, including for the imposing economy.

In pursuing such objectives, proactive tax tools incentivising meaningful linkages between foreign investors and local SMEs, such as targeted tax incentives, can offer an alternative to LCR policies. Targeted incentives generate less negative economy-wide effects and their long-term benefits on upgrading the capacity of suppliers can be higher, even if they are more costly and require stronger institutional capacity to be effectively implement. When LCR exist, local suppliers are mostly hired for lower value, site-specific operations such as construction, support services and non-productive functions. This is often done to meet the requirements rather than leveraging comparative advantages (Bamber et al., 2014[28]). In the best of cases, LCRs should dovetail with the interest of investors in reducing costs by procuring goods and services locally, but local content targets need to be both realistic and flexible and must be accompanied by broader policies supporting business linkages.

Diaspora investors can forge enhanced linkages with local business

MENA economies have large diaspora scattered worldwide that can positively influence cross-border investment flowing to their origin countries. Diaspora investors are also more likely to forge linkages with local suppliers than non-diaspora foreign investors (Amendolagine et al., 2019[16]). Chinese or Indian diaspora, for instance, have strongly contributed to the integration of both countries in GVCs, especially through investment (Buckley et al., 2007[29]). The diaspora can stimulate investment by reducing transaction and information costs as they often have links to local networks (Chen, Chen and Ku, 2004[30]). They can also circumvent challenges in remote or risky areas and provide a positive signal about the region. As with MNE affiliates, diaspora firms have higher productivity levels and better export performance relative to domestic firms (Boly et al., 2014[31]).

Evidence on investment by MENA diaspora in their home countries is limited. According to one survey, diaspora investors from MENA economies are doubtful that local businesses would be willing and able to work with them (Malouche, Plaza and Salsac, 2016[32]). They also believe that they do not benefit from the same preferential treatment accorded to foreign investors and do not expect much support from their governments to help them invest. A study on Tunisia reveals that potential diaspora investors often report not being aware of investment incentives offered to foreign investors (UNDP, 2016[33]). Existing Tunisian diaspora investors do not forge more partnerships with local businesses than other foreign investors, and their overall impact on jobs and wages is weaker than the impact of foreign firms. Tunisian diaspora investors are more present in remote or rural regions than foreign firms are, however.

MENA governments could further promote investment by diaspora, and their anchoring through linkages with local suppliers, by increasing outreach efforts and developing, in consultation with diaspora representatives, tailored attraction strategies and programmes. Lebanon developed several initiatives to attract greater investment from its diaspora (Box 8.6). The Moroccan government is active in attracting diaspora investors through regional investment centres and the Houses of Moroccans Living Abroad, a program that provides information to expatriates. Governments could also collect micro-level data on diaspora investors, as for instance API in Tunisia, to compare them with non-diaspora investors and monitor differences in trends and impacts (UNDP, 2016[33]).

Several government ministries and agencies are involved in attracting Lebanese diaspora investors and anchoring them through linkages with local SMEs. One of the objectives of the Lebanese IPA is to identify concrete investment opportunities across all regions of Lebanon and actively promote them locally and internationally among diaspora members. The Lebanon SME Strategy aims to facilitate linkages between the SMEs and MNEs, as well as with the diaspora, and share success stories of Lebanese expatriates.

The Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Emigrants is engaged in the promotion of diaspora investment through its foreign embassies and consulates. For instance, the Lebanese Diaspora Energy initiative, launched by the Ministry in 2014, has among its objectives to establish linkages between the diaspora and residents to provide opportunities for sharing experiences and establishing business and social connections. The initiative also aims to explore opportunities for Lebanese residents and expatriates to work together to restore the image of country and trust in the economy.

Source: (UNCTAD, 2018[34]).

References

[16] Amendolagine, V. et al. (2019), “Local sourcing in developing countries: The role of foreign direct investments and global value chains”, World Development, Vol. 113, pp. 73-88, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2018.08.010.

[7] Azmeh, S. and K. Nadvi (2014), “Asian firms and the restructuring of global value chains”, International Business Review, Vol. 23/4, pp. 708-717, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibusrev.2014.03.007.

[28] Bamber, P. et al. (2014), “Connecting Local Producers in Developing Countries to Regional and Global Value Chains: Update”, OECD Trade Policy Papers, No. 160, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/5jzb95f1885l-en.

[31] Boly, A. et al. (2014), “Diaspora investments and firm export performance in selected sub-Saharan African countries”, World Development, Vol. 59, pp. 422-433, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2014.02.006.

[29] Buckley, P. et al. (2007), “The determinants of Chinese outward foreign direct investment”, Journal of International Business Studies, Vol. 38/4, pp. 499-518, https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.jibs.8400277.

[30] Chen, T., H. Chen and Y. Ku (2004), Foreign direct investment and local linkages, https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.jibs.8400085.

[22] Galli, R. (2017), “The role of investment incentives for structural transformation a comparative analysis of investment incentives legislations in Sub-Saharan African, South-Asian and”, ILO Working Papers, No. 994955393402676, International Labour Organisation, https://ideas.repec.org/p/ilo/ilowps/994955393402676.html (accessed on 27 February 2021).

[4] Helmy Elsaid, H. et al. (2014), Small and Medium Enterprises in Egypt: New Facts from a New Dataset Small and Medium Enterprises Landscape in Egypt: New Facts from a New Dataset *, http://www.academicstar.us (accessed on 27 February 2021).

[23] IFC (2019), “Creating Markets in Morocco: A Second Generation of Reforms-Boosting Private Sector Growth, Job Creation and Skills Upgrading”, https://elibrary.worldbank.org/doi/abs/10.1596/32402 (accessed on 27 February 2021).

[2] ILO (2019), Small Matters: Global evidence on the contribution to employment by the self-employed, micro-enterprises and SMEs, ILO, http://www.ilo.org/global/publications/books/WCMS_723282/lang--en/index.htm (accessed on 27 February 2021).

[14] Joumard, I., S. Dhaoui and H. Morgavi (2018), “Insertion de la Tunisie dans les chaines de valeur mondiales et role des entreprises offshore”, Documents de travail du Département des Affaires économiques de l’OCDE, No. 1478, Éditions OCDE, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/546dbd75-fr.

[15] Karam, F. and C. Zaki (2015), “Trade volume and economic growth in the MENA region: Goods or services?”, Economic Modelling, Vol. 45, pp. 22-37, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econmod.2014.10.038.

[6] Kowalski, P. et al. (2015), “Participation of Developing Countries in Global Value Chains: Implications for Trade and Trade-Related Policies”, OECD Trade Policy Papers, No. 179, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/5js33lfw0xxn-en.

[32] Malouche, M., S. Plaza and F. Salsac (2016), Mobilizing the Middle East and North Africa Diaspora for Economic Integration and Entrepreneurship Mariem Mezghenni Malouche, The World Bank, Washington, DC., https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/26307 (accessed on 27 February 2021).

[10] OECD (2020), COVID-19 and global value chains: Policy options to build more resilient production networks, OECD, Paris, http://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/policy-responses/covid-19-and-global-value-chains-policy-options-to-build-more-resilient-production-networks-04934ef4/ (accessed on 27 February 2021).

[11] OECD (2020), Investment in the MENA region in the time of COVID-19, OECD, Paris, http://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/policy-responses/investment-in-the-mena-region-in-the-time-of-covid-19-da23e4c9/ (accessed on 27 February 2021).

[12] OECD (2020), OECD investment policy responses to COVID-19, OECD, Paris, http://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/policy-responses/oecd-investment-policy-responses-to-covid-19-4be0254d/ (accessed on 27 February 2021).

[13] OECD (2020), OECD Investment Policy Reviews: Egypt 2020, OECD Investment Policy Reviews, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9f9c589a-en.

[26] OECD (2020), OECD Investment Policy Reviews: Indonesia 2020, OECD Investment Policy Reviews, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/b56512da-en.

[3] OECD (2019), “Fostering greater SME participation in a globally integrated economy”, in Strengthening SMEs and Entrepreneurship for Productivity and Inclusive Growth: OECD 2018 Ministerial Conference on SMEs, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/400c491d-en.

[20] OECD (2019), Mapping of Investment Promotion Agencies: Middle East and North Africa - OECD, OECD, Paris, https://www.oecd.org/investment/investment-policy/mapping-of-investment-promotion-agencies-med.htm (accessed on 27 February 2021).

[1] OECD (2019), OECD SME and Entrepreneurship Outlook 2019, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/34907e9c-en.

[19] OECD (2019), SME Policy Effectiveness in Jordan User Guide 1: Reinforcing SME policy co-ordination and public-private dialogue, OECD, Paris, https://www.oecd.org/mena/competitiveness/sme-policy-effectiveness-in-jordan-user-guides.htm (accessed on 27 February 2021).

[21] OECD (2018), Mapping of investment promotion agencies in OECD countries - OECD, OECD, Paris, http://www.oecd.org/investment/Mapping-of-Investment-Promotion-Agencies-in-OECD-Countries.htm (accessed on 27 February 2021).

[25] OECD (2016), OECD Clean Energy Investment Policy Review of Jordan, Green Finance and Investment, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264266551-en.

[35] OECD/CAF (2019), Latin America and the Caribbean 2019: Policies for Competitive SMEs in the Pacific Alliance and Participating South American countries, SME Policy Index, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/d9e1e5f0-en.

[18] OECD/European Union/ETF (2018), The Mediterranean Middle East and North Africa 2018: Interim Assessment of Key SME Reforms, SME Policy Index, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264304161-en.

[17] OECD/The European Commission/ETF (2014), SME Policy Index: The Mediterranean Middle East and North Africa 2014: Implementation of the Small Business Act for Europe, SME Policy Index, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264218413-en.

[5] OECD-UNIDO (2019), Integrating Southeast Asian SMEs in global value chains: Enabling linkages with foreign investors - OECD, https://www.oecd.org/industry/inv/investment-policy/integrating-southeast-asian-smes-in-global-value-chains.htm (accessed on 27 February 2021).

[24] Sabha, Y., Y. Liu and W. Douw (2020), Investment Linkages and Incentives IN FOCUS Promoting Technology Transfer and Productivity Spillovers from Foreign Direct Investment (FDI), World Bank, http://www.worldbank.org (accessed on 27 February 2021).

[27] Stone, S., J. Messent and D. Flaig (2015), “Emerging Policy Issues: Localisation Barriers to Trade”, OECD Trade Policy Papers, No. 180, OECD, Paris, https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/trade/emerging-policy-issues_5js1m6v5qd5j-en (accessed on 27 February 2021).

[34] UNCTAD (2018), Investment Policy Review of Lebanon, UNCTAD, Geneva, https://investmentpolicy.unctad.org/publications/1196/investment-policy-review-of-lebanon (accessed on 27 February 2021).

[9] UNCTAD (2013), World Investment Report 2013, GLobal Value Chains: Investment and Trade for Development, UNCTAD, https://worldinvestmentreport.unctad.org/wir2013/ (accessed on 27 February 2021).

[33] UNDP (2016), Case Study : Assessing the impact of diaspora investments in Tunisia, UNDP, https://www.undp.org/content/undp/en/home/librarypage/poverty-reduction/case-study---assessing-the-impact-of-diaspora-investments-in-tun.html (accessed on 27 February 2021).

[8] UNECA (2016), Promoting Regional Value Chains in North Africa, UNECA, Addis Ababa, https://repository.uneca.org/handle/10855/23016 (accessed on 27 February 2021).

Notes

← 1. The measures focus on the manufacturing sector.

← 2. There are not enough observations for Morocco and Tunisia to include firms in the machinery sector (e.g. automotive sector).

← 3. SMEs are defined here as firms with less than 100 employees.

← 4. Along with dispute settlement provisions contained in the legislation and in IIAs, the adherence of all MENA economies to international conventions, such as the New York Convention on the Enforcement and Recognition of Foreign Arbitral Awards, also provides a guarantee that contracts will be enforced smoothly, in the event a dispute is brought before an arbitral panel rather than before domestic courts.

← 5. According to the latest edition of the SME Policy Index for the Middle East and North Africa, Morocco was part of the EEN; however, that country does not appear in more recent lists of EEN contact points (OECD/European Union/ETF, 2018[18]).

← 6. See https://ec.europa.eu/easme/en/enterprise-europe-network.

← 7. See https://anima.coop/en/ and http://ebsomed.eu/.

← 8. See, for example, the Business Development Centre, the Young Entrepreneurs Association, Injaz, the Crown Prince Foundation, the King Abdullah Fund for Development, the SME Association, Endeavor, and Oasis 500 (OECD, 2019[19]).

← 9. For a more complete overview of the BDS markets in the MENA region refer to the SME Policy Index for the Mediterranean Middle East and North Africa editions 2014 and 2018 (OECD/The European Commission/ETF, 2014[17]) (OECD/European Union/ETF, 2018[18]).

← 10. For example, the SME and entrepreneur portals and websites established in some Lain American countries providing up to date and structured search engines for small businesses to search for support to access markets, technology, finance, etc. (OECD/CAF, 2019[35]).