1. Estonia: Well-positioned for further progress with gender equality

Gender inequalities persist in Estonia. The gender pay gap is narrowing, but remains above the OECD average, but the gender employment gap is stable as women continue to shoulder the bulk of unpaid work in and around the house in Estonia. Drawing on the detail in the subsequent chapters, this first chapter presents in a nutshell the most pertinent gender gaps, the associated challenges and relevant policy options to generate greater gender equality in the Estonian labour market and spur on economic growth.

Estonia has experienced huge economic change over the past 20 years: GDP per capita has doubled since 2000 even though it remains below the OECD average, and the labour market has changed due to the transformation into a market economy with a large service sector. Women have gained from this transition and are now experiencing increased returns to education. The female employment rate (72%) in Estonia is above the OECD average (61%), and the employment gender gap in favour of men is small at 3 percentage points – the OECD average is 15 percentage points. Also, Estonian women generally work full-time: at 13% the incidence of part-time employment among women in Estonia is just below half the OECD average.

Nevertheless, economic and labour market gender differentials persist. In other OECD countries the gender employment gap has narrowed, but not in Estonia. The gender wage gap at the median for full-time workers (at 19% in 2019) has narrowed but remains above the OECD average (12%). Women continue to shoulder the bulk of unpaid work in and around the house in Estonia, and the COVID-19 pandemic illustrated just how much an overburdened health care system and Estonian society more generally draw on women’s contributions to unpaid work. This raises immediate questions about women’s ability to engage in the labour market on parity with men, particularly during early and mid-career periods when wage increases are common and many career-defining promotions are made. Looking ahead, increased longevity, poor health among older men, and limited health care funding look set to increase the demands on women to do unpaid work, unless there is a change in attitudes and policy.

Looking forward, there is a lot to gain from more economic equality between men and women. Further opening up opportunities to women will also play an important part in supporting overall increases in economic growth and productivity. For example, if Estonia were to fully close its gender gap in labour force participation (LFP) rates by 2050, it could expect around 0.07 percentage points (p.p.) of additional growth in potential GDP per capita each year. This would be equal to potential output in 2050 being 2.3% higher than under a baseline growth trajectory. Noticeable effects on economic growth include: a more equal sorting of boys and girls into educational fields may lead to around +0.30 p.p. of additional annual growth), while a reduction of the gendered division of unpaid work may increase (+0.33 percentage points annual growth).

A more gender-equal society will also have different social benefits, including, better male health and fewer women exposed to partner violence. Estonia is in a good position to introduce policies with central government debt being the lowest among OECD countries. Furthermore, with the (planned) allocation from the EU recovery fund, there appears to be more fiscal space to invest in policies for gender equality.

This analysis underlying this review was mostly done prior to the war of aggression by the Russian Federation against Ukraine, which led to an in inflow of a great number of refugees in Estonia from February/March 2022 onwards. By 5 September 2022, Estonia had already received over 54.197 Ukrainian war refugees, mostly women and children, which is equivalent to around 4 2% of Estonia’s total population. It is as yet unclear how many Ukrainian refugees will end up in Estonia, for how long, and what the socio-economic ramifications might be.

1.1.1. Young women have higher educational attainment, but study choices remain traditional

The Estonian education system has a reputation to uphold as a high performer in OECD comparison. In 2018, it ranked first among the OECD countries in OECD PISA scores for reading literacy and science, as well as third in mathematics. The system in place ensures that students from different socio-economic backgrounds achieve similarly high results, while the gender gap in the OECD PISA scores has decreased over time. In Estonia, this translates to high proportions of young women with tertiary education: the difference in the proportions of young women and young men who have attained tertiary education is 22 percentage points, to the disadvantage of young men; this is considerably higher than the OECD average difference of 13 percentage points (Chapter 2).

Nevertheless, how well a university-level education pays off in the labour market also depends on the subjects that were studied. In school, girls outperform boys in reading and science, but boys outperform girls in mathematics, and this contributes to the different educational choices young men and women make. However, stereotypes also play a huge and important role and the notion that “math is not for girls” remains widespread, while in more gender equal countries the gender gap in OECD PISA scores tends to be smaller. There is a large gender gap in the proportion of boys and girls who conditional on their mathematics performance, report in the OECD PISA survey that “[their] parents believe that math is important for [their] career”. The mathematics-related stereotypes are considerable in Estonia and slightly larger than across OECD countries (Chapter 2).

1.1.2. Gender gaps in employment sector and pay are large

The high level of educational attainment among young Estonian women contributes to their high participation rate in the Estonian labour market. Furthermore, women and men in Estonia tend to work longer hours per week than women and men across the OECD on average (women: 34.0 hours; men: 40.0 hours): the gender gap in full-time employment and working hours is comparatively low – in 2019 women worked for 36.7 hours per week, while men did so for 39.4 hours (OECD, n.d.[1]).

Prima facie, the employment rates and working hours of men and women in Estonia bode well for gender equality in labour market outcomes. However, employment is highly gender-segregated and mirrors the differences in girls’ and boys’ educational choices. Men are overrepresented in industry sectors such as information, communication and manufacturing, where 30% of all male employees work, but only 18% of all female workers. On the other hand, 28% of all women in employment work in education, human health and social work activities, which only account for 2% of all men in employment.

The outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic initially hit women’s employment more than men’s, but it subsequently recovered quickly, and effects were cushioned by Estonia’s social protection system and pandemic response measures.

Even though the gender gaps in employment rates and working hours are relatively small in Estonia, women receive significantly lower pay than men. The gender wage gap at median earnings for full-time workers amounted to 17% in 2018, compared with 13% on average across the OECD. Nevertheless, strong gains were made over the past decade: the gender wage gap in Estonia has been shrinking much faster (-6 percentage points) than on average across the OECD (-1 percentage point) (Chapter 2).

There are significant differences in the labour market outcomes of ethnic Estonians and non-Estonians – in this context, the terms “Estonian” and “non-Estonian” refer to ethnic origin and not citizenship. Non-Estonians make up about 30% of the population and are predominately ethnic Russians, but also Ukrainians, Belarusians and Finns. For example, the gender employment gap is consistently larger among the non-Estonian than the Estonian population. Also, non-Estonian women are 5 percentage points less likely to be in work than Estonian women, and non-Estonian women that are in employment are paid about 20% less than Estonian women (about 1 EUR per hour worked) (Chapter 2).

The COVID-19 pandemic and employment in Estonia

The COVID-19 pandemic and ensuing economic crisis hit Estonia hard: the employment rate dropped from 76.1% in Q4 2019 to a low of 72.2% in Q2 2020, but it rebounded to 74.4% in Q3 2021. The economic crisis initially hit women harder than men. In large part, this is because they tend to be overrepresented in sectors that were hardest hit by restrictions on social interaction, including leisure, hospitality and non-food retail. In addition, the additional care needs that have arisen partly due to school closures have fallen heavily on mothers. Many women reduced their working hours or left the workforce (Chapter 2). The initial negative impact on the gender employment gap in Estonia, which increased by 1.7 percentage points in Q2 2020 relative to Q4 2019, was among the worst across the OECD. But, the employment gap declined as the economy started its recovery in the second half of 2020, and by Q3 of 2021 the gender employment gap was smaller than before the COVID-19 pandemic (3.3 percentage points in Q3 2021 compared with 3.6 percentage points in Q4 2019). However, it is not yet clear whether the pandemic will have significant long-term implications for gender equality on the Estonian labour market.

In its reaction to the pandemic, the Estonian Government significantly extended support for workers and firms. The total economic stimulus package amounted to 4.1% of 2019 GDP, only slightly lower than the average of 4.5% across G20 countries. The main measure for workers and firms was a temporary wage subsidy scheme during the state of emergency (both in 2020 and 2021), which supported about 20% of all employment. Other measures included: covering social security contributions, a temporary reduction in fuel excise taxes, and the provision of liquidity to firms.

1.1.3. Traditional attitudes are common and fuel an unequal division of unpaid work

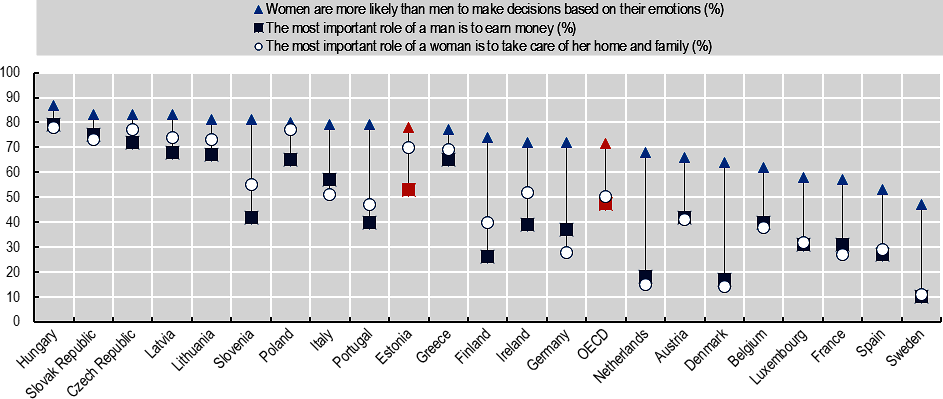

Attitudes towards gender equality and the innate abilities of men and women are relatively traditional compared to the OECD as a whole, which can be detrimental to the labour market position of women in Estonia. More so than people in OECD countries Estonians believe that women are more likely than men to make decisions based on their emotions (Figure 1.1). Such beliefs about the capacity for rational decision-making can impose substantial barriers to their access to lucrative and/or leadership positions.

The prevailing gender norms in Estonia also lead to a gendered division of unpaid work in and around the house. For instance, 70% of Estonians believe that the most important role of a woman is related to care and housework, which is about 20% higher than on average across the OECD (Figure 1.1). These beliefs contribute to an uneven division of paid and unpaid work within Estonian households, where women spend about 1.5 hours more per day on unpaid work than men, and more than half of Estonian women report that they felt overburdened by housework, compared to about one-fifth of men (Chapter 2). Because of competing expectations and responsibilities, women cannot prioritise their careers in the same way as men can, particularly during their early to mid-career when they are squeezed by care responsibilities, often raising young children and caring for elderly relatives at the same time.

1.1.4. Gender gaps change over the life course and differ notably from the rest of the OECD

In Estonia, like in many other OECD countries, gender gaps in employment outcomes change over the life course. Estonian women have substantially lower employment rates in their early- to mid- labour market career, particularly following childbirth. However, contrary to the average across the OECD and except for the youngest labour market cohorts (aged 20-29), the gender gaps in employment rates subsequently steadily narrow over the life course in Estonia, so that among older workers, women are more likely to work than men. In particular, OECD-wide the probability of employment of 55+ women is more than 15 percentage points lower than that of their male counterparts, but in Estonia, older women are nearly 5 percentage points more likely than older men to be employed (Figure 1.2).

This pattern is consistent with the significantly lower number of healthy life years of Estonian men. They are, for example, overrepresented in occupations with higher rates of workplace fatalities and injuries, but are also subject to traditional masculinity norms that encourage more risky and unhealthy behaviours, in particular the excessive consumption of alcohol, tobacco, or drugs. Life expectancy at birth is about 8.4 years shorter for Estonian men than for Estonian women in 2020 – one of the largest gender gaps in life expectancy in the OECD. These patterns are mirrored in the large gender gaps in deaths from cancer: 176 more men than women per 100 000 persons died from cancer in 2019 (Chapter 4).

Part of the reason for this gender gap in employment can be due to poor physical health among older male workers and inadequate personal finances among older female workers, requiring them to top up pension payments with labour market earnings, but wider labour market conditions have also suppressed male activity rates in older ages. The flexibilisation and industrial transition away from industry and toward services in the 1990s have increased the risk of unemployment, particularly among older-age, lower-educated blue-collar workers.

1.1.5. Glass ceilings are hindering women from entering management and boardrooms

Women often experience a slower career progression than men in comparable jobs and industries, which affects women’s representation across different levels of management. For instance, with 9% and just after Korea, Estonia has the second smallest share of women on corporate boards among OECD countries (27% on average). Furthermore, representation on the top of the corporate pyramid has been remarkably stable in Estonia, while several other countries have seen substantial increases in female board representation over the past decade – including in Estonia’s neighbour Latvia, where the share of women on corporate boards almost doubled between 2009 and 2019. However, when going down the corporate ladder, gender gaps become noticeably smaller, indicating that there is a pipeline of female talent. For example, 37% of managers in Estonia are female, which is above the OECD-wide average of 33% and in the upper third of all OECD countries (Chapter 2).

Nevertheless, the prevailing attitudes towards women in positions of power may contribute to the low representation in the upper ranks of corporate leadership. While a majority (57%) of Estonian women agree with the statement that businesses would benefit from more female representation in senior positions, only 45% of Estonian men agree with this sentiment (Chapter 2). These findings suggest there is scope for improvement in supporting conditions that would facilitate more women to break through the glass ceiling.

1.1.6. Compared to other countries Estonia has a low share of women entrepreneurs, but a relative high number of women who start a business

Estonian women, much like elsewhere in the OECD, are less likely than men to create a business, work in a new start-up, or be self-employed. Only in Türkiye is the share of women among employers lower than in Estonia. Only 19% of all self-employed workers who employ others are women, while across the OECD women make up more than a quarter (27%) of this group (Chapter 2).

Engagement in early-stage entrepreneurship among women is relatively widespread in Estonia. Indeed, Estonia has among the highest share of the female working-age population that is actively engaged in early-stage businesses, at 12%. This can be compared to the lower OECD-wide average figure of 8%. This could mean that policies to help self-employed women develop and scale up their businesses have the potential to support the incomes of a relatively large share of women (Chapter 2).

Like in most OECD countries, gender wage gaps in Estonia are larger when accounting for differences in educational choices and skills. Indeed, when comparing similarly skilled men and women – as measured by educational attainment (in terms of the highest level of completed education) and potential work experience (as measured by age) – the gender wage gap increases by about 5 percentage points relative to the original gap (Chapter 3). This reflects the fact that on average in Estonia, working women tend to be better educated than working men. One implication of this is that a better understanding of the gender wage gap requires focusing on differences in the characteristics of the firms and jobs in which women and men are employed, rather than differences in their skills.

1.2.1. Vertical and horizontal segregation are large drivers of wage inequality

One-quarter of the wage gap between similarly skilled men and women reflects the gendered segregation between firms (“horizontal segregation”). This is because Estonian women typically work in firms and industries that pay lower wages than the firms Estonian men work in. Another quarter reflects the fact that Estonian women also work in low-wage occupations within firms (“vertical segregation”). The remaining half is unexplained and may reflect differences in tasks and responsibilities within occupations or differences in pay for work of equal value (Chapter 3).

The sorting of women into low-wage firms reflects to some extent differences in non-wage working conditions, as women may be constrained to opt for firms with flexible working time arrangements due to childcare responsibilities and unpaid homework. However, it may also reveal the role of discriminatory hiring practices by employers in high-wage firms. Then again, the sorting of women into low-wage industries also reflects the tendency of women to sort into economic activities that are compatible with their past educational choices.

1.2.2. Pay practices within and between firms play an important role

A more detailed analysis of gender pay gaps based on Estonian administrative tax records uncovers the role different pay practices within and between firms play for men and women who are similarly skilled and have similar tasks and responsibilities in their jobs. These differences in firm pay practices account for about half of the gender pay gap in Estonia. Of this, three-fifths can be attributed to the fact that women tend to work in firms that pay lower wages. The other two-fifths of the explained part of the gender wage gap reflect gender differences in pay within firms, and can be attributed to a weaker bargaining position of female employees vis-a-vis employers, but may also partially reflect pay discrimination against women. The remaining half of the gender wage gap between similarly skilled men and women cannot be explained by differences in firm pay practices between or within firms (Chapter 3).

Differences in firm pay practices between men and women also explain why the gender wage gap is larger at the upper end of the wage distribution (Chapter 3). This may be because of the difficulty women face in accessing management and leadership positions in firms that tend to pay the highest wages. These barriers may additionally weaken women’s bargaining position, potentially exacerbating differences in pay practices for work of equal value within firms.

Pay gaps for similarly skilled men and women with similar tasks and responsibilities also differ across industries. Differences in the pay practices within firms are especially common in industries where labour market competition is weak. The differences in pay practices between firms tend to be smaller in industries where firms face more competition.

1.2.3. Motherhood and career breaks widen wage gaps

Similar to gaps in employment rates, pay differences between men and women increase with age until the mid- to late thirties, after which they start to decrease gradually (Figure 1.3). The increase in wage gaps over prime childbearing age coincides with the period where women reduce their engagement in full-time work following childbirth. The observed wage patterns across age groups seem to reflect what is often referred to as the motherhood wage penalty.

The motherhood wage penalty may reflect various factors. For example, mothers may choose to work in firms that offer family-friendly working conditions, which can come at the expense of wage levels, or they temporarily switch to part-time work to balance their care responsibilities with paid work. The lack of work experience and skill-deterioration during career breaks, including foregone wage increases, and/or lack of access to training and career opportunities, also contribute to the motherhood wage penalty. The effect of career breaks in Estonia can be pronounced as career breaks can be of long duration: workers are guaranteed to move back in the same position after parental leave career breaks of up to 3 years.

Decomposing the gender wage gap among men and women with similar attributes in between and within firm effect by age, suggests that the increases in wage gaps over prime childbearing age are not directly related to firm pay practices. This is because the total wage gap explained by pay differences within (“bargaining”) or across (“sorting”) firms remains roughly the same regardless of age, while the total wage gap increases markedly for the 30 to 39 year age group (Figure 1.3). Wage gaps for workers in their thirties must increase for other reasons including career breaks following childbirth.

Estonia has a comprehensive system of work-life balance supports for parents, in particular for children of at least pre-primary school age (children above the age of three). However, many parents with very young children see the balance of work and care commitments fully tilted towards care responsibilities. The lengthy parental leave career breaks are almost exclusively taken by mothers – to the detriment of their earnings and career development.

1.3.1. Supports for families with children age 3 and older are comprehensive

The majority of children between age 3 and school age are enrolled in pre-primary education (93%), most of which are attending local government childcare. These institutions provide their services for up to half of the day (7 a.m. to 7 p.m.), generally allowing parents to engage in paid work during the day. The parental fee for these services, which are paid as a percentage of family net income, are among the lowest OECD-wide (Chapter 4).

In Estonia, all children attaining age 7 before the first of October of the current year must attend school. The state or municipally owned schools provide out-of-school-hours (OSH) services for children of school age, conditional to the needs of working parents. Where parents’ working time exceeds weekly school hours, students can attend “long day groups” organised by the basic schools, which offer homework assistance and recreational activities. However, just below 20% of Estonian children aged 6-11 participate in such out-of-school-hours services (Chapter 4).

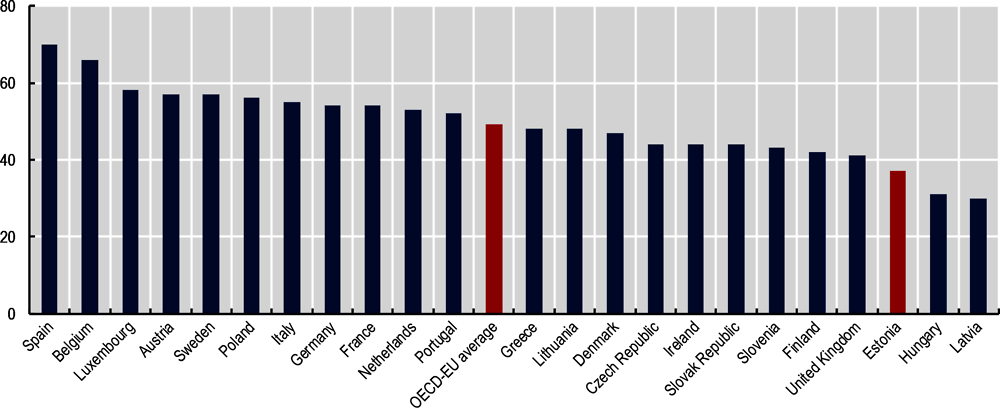

Men and women in Estonia generally enjoy widespread access to flexible working time arrangements that can help them balance care commitments with their working life. For instance, more than two-thirds of Estonian respondents to a Eurobarometer survey in 2018 reported that “flexitime” is widespread in their current job. This is substantially higher than the EU average of roughly 60% (Chapter 4).

1.3.2. Mothers of young children often leave the workplace for at least a year

The Estonian system provides statutory paid family leave entitlements of 605 days (maternity-, paternity- and paid parental leave), that can be taken until the child turns 3 years old and which is followed by access to publicly provided formal childcare. Maternity leave is granted for 14 weeks (100 calendar days), paid through the maternity benefit at 100% of earnings without a maximum payment ceiling, which can be used up to 10 weeks (70 calendar days) before and 4 weeks (30 calendar days) after the expected date of birth. If a mother decides to take out less than 10 weeks of mother’s parental benefit before birth, up to 6 weeks (40 calendar days) can be transferred to the shared parental benefit that can be used by the father as well. Fathers are entitled to paternity leave and paternity benefit that is payable for 30 calendar days at 100% of earnings up to a high threshold (about 3 times average earnings). Paid parental leave is a family entitlement, and it is thus up to the parents to decide who takes leave. Throughout the paid parental leave period, which can last for 68 weeks (475 days), the parent on leave is paid through the shared parental benefit at a payment rate of 100% of earnings (up to the same threshold as for paternity leave).

The shared parental benefit and paternity benefit can be taken up on a daily basis, allowing parents to spread the payments of the parental benefit over a longer period, while the maternity benefit has to be taken in one block. From the time the child is 31 days old, parents can freely decide who will receive the shared parental benefit. At the same time, both parents can take 60 calendar days of the shared parental benefit simultaneously, which is then deducted from the overall family entitlement. Both the paternity benefit and the shared parental benefit can be taken on a part-time basis (e.g. two days per week), while parents are allowed to earn income when receiving the shared parental benefit. Upon expiry of paid leave, parents can take unpaid leave as the period of job-protection upon childbirth lasts until the child turns three.

The length and payment rates of the Estonian parental leave scheme are comparatively generous: Estonia provides the longest full-rate equivalent paid leave period among OECD countries (Chapter 4). This makes Estonia the OECD country with the second highest public expenditure on maternity and parental leaves per live birth (Figure 1.4). According to the Estonian Social Insurance Board, most parents in Estonia use parental leave, and many do so for more than the 62 weeks during which the parental allowance is granted. The share (62%) of adults of childbearing age (25-44) who have interrupted their time in paid work to take care of their children for more than 2 years is nearly twice as high as the average among other European OECD countries.

In contrast to most other OECD countries, the Estonian system allows receiving payment of the parental allowance while not being on leave to facilitate more parents to remain in touch with the workplace when children are very young. The parental leave benefit is reduced by 50 cents for each Euro earned in excess of 1.5 times average salary (EUR 2 021.54 per month in 2022). As fathers’ earnings are often higher than mothers’ earnings, it makes sense from a household perspective if they were to claim the parental allowance. Yet, women still make up over 85% of paid parental leave takers and all adults of childbearing age who interrupt their presence in the workplace for more than 2 years to take care of their children are mothers. The combination in Estonia of a three-year-long job-protected parental leave (that is fully compensated until 605 days) and its disproportionate uptake by mothers explains why Estonian mothers with children under the age of 3 have one of the lowest employment rates (about 30% in 2019) in the OECD, only half the average among all member countries – about 59% (Chapter 4).

1.3.3. Towards a better sharing of career breaks after childbirth

To foster greater gender equality in labour market outcomes, it is necessary to encourage a more equal use of the leave entitlements among parents. In particular, it is important to limit mothers’ career breaks by increasing fathers’ use of leave entitlements around childbirth and the first years of their children’s life.

Previous attempts at increasing the attractiveness of paid parental leave for fathers in Estonia have improved use by fathers of parental leave benefit. For instance, following the 2018 increase of the labour earnings threshold above which parents lose parental leave benefit, the share of fathers among recipients of parental leave benefit doubled (from 8% in 2018 to 16% in 2021). The 2018 reform also triggered an increase in the share of fathers receiving the parental leave benefit who stay connected to work (from 53% to 71% between 2018 and 2021, while this share had been stable at around 50% before). However, there is a risk that in households where fathers receive both parental leave benefit and income from work continue working, this complicates the mother’s return to work, in view of the care needs of the very young child (Chapter 4).

One policy option involves following other OECD countries by extending parental leave periods for the exclusive use by fathers. This can be achieved either by a “father quota”, which grants fathers a non-transferable period of parental leave; a system of bonus-months that grants parents extra leave time if fathers take a specific period of leave of absence from paid work; or by increasing the length of paternity leave entitlements.

Some of these steps have recently been made in Estonia. For example, in 2020 paternity leave was extended from 10 working days to 30 calendar days, which has led to increases in paternity leave uptake among fathers, much of which is taken for the full available entitlement. In terms of further amendments to the family leave schemes in Estonia, maternity leave has been reduced from 20 to 14 weeks in 2022, compensated by an equivalent increase in shared parental leave entitlements. While parents were previously only able to decide on the 71st day following the child’s birth which parent would receive the parental benefit, fathers with a one-month-old child will now have the option for a shared parental benefit. Since then, parents have been allowed to take parental leave simultaneously for up to 60 days and take the parental leave in turn, rather than having to decide which parent takes the parental leave in full (Chapter 4).

1.3.4. A continuum of work-life balance supports

After parental leave entitlements are exhausted, it is vital to ensure that good quality and affordable formal childcare services are available to provide families with a de facto continuum of supports towards that the reconciliation of work and family commitments. If taken in one continuous block, paid parental leave runs out after 18 months but almost every tenth child aged between 18 and 36 months does not get a childcare place. Moreover, even if they do, it is often with significant delay – complicating parents’ labour market engagement until then (Chapter 4). This situation is alleviated by the amendment that the parental benefit can be used on a daily basis until the child reaches the age of three. This will allow parents to spread the payments of the parental benefit over a longer period. The current possibility of earning income while receiving parental benefit will continue, so that the parent can work at a volume of their choice while raising the child.

Estonia spends about 3% of GDP on family benefits, almost the same as in Iceland (3.2% of GDP). But where 70% of such spending in Iceland – and over 60% in Denmark and Sweden as well as 40% across the OECD on average – goes toward formal childcare and other family services, this proportion is only 27% in Estonia (i.e. 0.8% of the total 3% of GDP that go to any public spending on families). There is a case for a greater focus on formal childcare supports and other family services in public spending on family benefits.

While recent demographic trends may exert downward pressure on the demand for formal childcare over the current decade, if more parents choose to take leave for a shorter duration – in view of the potential career and earnings ramifications, this would necessitate an increase in childcare capacity so that more one-year-olds can get a place. A reduction in compulsory school-starting age could open up kindergarten places, but this may not fit in with prevailing education policy objectives. In any case, more public investment in good quality formal childcare seems needed to ensure that parents with very young children can return to work when they want, rather than when a childcare place becomes available.

1.3.5. Alleviating the long-term care burden for families

In Estonia, informal care is the backbone of current long-term care (LTC) provisions, meaning that long-term care responsibilities curtail family members’ (especially women’s) ability to participate actively in the labour market. According to the Estonian Social Survey, women made up almost 60% of informal long-term carers in 2019, and women assisting elderly relatives and family members with disability were nearly twice as likely as their male counterparts to devote 20 hours or more per week providing such care. Long-term care needs are likely to increase in future years as the Estonian population is ageing rapidly, while it is also ageing less healthily than in most other EU countries. One in four Estonians aged 65 years or older report long-standing severe limitations in usual activities due to health problems in 2019, as opposed to one in six on average in other European OECD countries (Chapter 4). Estonia aims to improve the efficiency of integrated long-term care service delivery. However, it will also require significant additional funding to reduce the care burden of families.

Traditional gender norms are common in Estonia. They contribute to an unequal division of unpaid work to the detriment of women and fuel the notion that women are less productive employees than their male colleagues. Both these factors contribute to gender differences in bargaining power over wage rates and/or hiring decisions.

1.4.1. Most wages are individually negotiated, and pay transparency could reduce inequality

The negative effects of traditional gender norms on the gender pay gap within firms could potentially be mitigated if wages for specific jobs are negotiated through collective bargaining on the industry- or firm- rather than at an individual level. However, only 6% of Estonian workers are members of a union, and Estonia has the lowest trade union density OECD-wide. Coverage of employees by collective bargaining agreements is also the lowest among OECD countries (Figure 1.5). Overall, wages were set by collective bargaining in only 6% of Estonian firms, which is less than a tenth of the average in other European OECD countries (Chapter 5).

As the vast majority of wages in Estonia are individually negotiated, an implementation of pay transparency policies could pave the way to more female bargaining power and less gender-based discrimination in the Estonian labour market. However – and although these policies rely on aggregate, not individual data – many employers and employees view them as conflicting with the obligation stipulated in the Employment Contracts Act to keep individual wages confidential. This may have contributed to lower average support for pay transparency policies (57%) than in other European OECD countries (63%) (Chapter 5).

1.4.2. Enshrining pay transparency on the Estonian labour market

In 2016, the Gender Equality Act and Other Acts Amendment Act was introduced to enshrine pay transparency measures in law. It was envisioned to mandate firm-level reporting of the gender composition of the workforce and pay differences between men and women in different job categories. This would help employers to close unjustifiable gender pay gaps, but could also contribute to reducing horizontal and vertical segregation that drive gender pay gaps across job categories. The latter is particularly important for top jobs, as employers are typically not required to report gender pay gaps in job categories where the number of employees of either gender falls below a given threshold. The Act also foreshadowed the introduction of a Pay Competence Centre at the Labour Inspectorate in charge of monitoring equal pay reporting and the implementation of a gender-equal job valuation.

The Act would have operationalised the concept of “equal pay for work of equal value”, by mandating pay transparency reporting along a gender-neutral job classification system that is validated and verified based on objective work-related characteristic. It would have been similar to practice in some other OECD countries (e.g. in Belgium, Finland, France, Iceland, Portugal and Spain). However, as the Gender Equality Act and Other Acts Amendment Act was not adopted before the parliamentary elections of 2019, the wide-ranging measures to enshrine pay transparency in the Estonian labour market were not legislated at all. These gaps will be addressed in the near future as Estonia works on ensuring compliance with the EU pay transparency directive.

1.4.3. Ensuring compliance with pay transparency measures

A critical factor in the success of pay transparency policies is the compliance of employers with the reporting of gender pay gaps. Specific enforcement mechanisms need to be established to ensure employer compliance. However, imposing financial penalties on “non-compliers” has not led to high compliance rates in most of the OECD countries with systematic and regular reporting on gender gaps in private sector firms. A potential reason for this may be the low level of fines and/or incomplete monitoring of pay transparency policies by the established government agencies.

One option to ensure greater compliance with pay transparency reporting measures is to introduce the obligation for employers to publish their gender gap statistics so that both employees and the general public can access them. This is, for example, done in the United Kingdom, where it has increased awareness over pay transparency, and also allowed some employers to enhance their attractiveness among job candidates, employees, customers and suppliers concerned by working with a socially-responsible employer.

It is important to avoid a large administrative burden for the many small- and medium-sized firms in Estonia. A public agency could be tasked with the responsibility of using administrative data to compute firm-level gender gaps, such as implemented in Lithuania (as the only OECD country). This approach would also be easy to implement in Estonia, based on the “palgad.stat” already managed by Statistics Estonia to report occupation-based gender composition and pay gaps at both the national and local (county) level. In this context, Estonia is developing a Pay Mirror app that, by 2024, will allow employers to automatically generate information on the gender pay gaps that prevail within their organisation, based on administrative data. This application is expected to increase the buy-in of pay transparency policies among employers and ensure high quality, accurate and comparable figures across employers.

Apart from pay reporting, other measures can also support equal pay for work of equal value. For instance, it is possible to target measures at specific sectors where discriminatory pay differentials are particularly large. Also, the creation of online training courses directed at employers and devised along with good practice, in Estonia for example in the framework of the Virtual Competence Centre at the Ministry of Social Affairs, could raise awareness and promote gender equality among key stakeholders. The implementation of good practice can be incentivised with a government-led certification programme to reward employers who take a set of concrete actions to improve the labour market situation of women.

In many ways, work-life balance and pay transparency policies come too late – they seek to remedy gender gaps in the labour market after years of social interactions that largely endorse traditional gender roles. For a structural shift towards gender equality, this ex-post approach should be complemented by efforts to chase out social norms that view men and women as fundamentally different and unequal.

1.5.1. Promoting gender equality in the education system

Many Estonians do not consider the promotion of gender equality as personally important to them: only a small majority (54%) recognise gender disparities as an issue, which is about a third lower than among European OECD members overall (81%) (Figure 1.6). Norms regarding gender equality often emerge early in life and are perpetuated through stereotypical educational pathways boys and girls often choose. Gender mainstreaming in education could thus be a particularly powerful tool to change the perception of the younger generation in Estonia. For this, it would be important that school staff and educational materials do not perpetuate traditional gender norms. To help achieve this, systematic pre- and in-service training on gender equality for teachers at all levels of education as well as career counsellors and youth workers can help, as they can directly influence young people’s career choices. It is also important to embed gender equality throughout the curriculum, including in specific school subjects, such as civic education, to avoid conscious and unconscious bias, notably against girls and women.

Currently, the use of textbooks in Estonian schools is subject to an independent review and confirmation that the information contained in the textbook is age-appropriate, consistent with the national curriculum, and that it contributes to “the moral, physical and social development of the pupil”. However, while spreading gender stereotypical worldviews is a matter of consideration in the review process of textbook proposals, and the curricula of both basic and upper secondary schools in Estonia define gender equality as core values, there is no efficient national mechanism to prevent a textbook full of gender stereotypes from reaching children. The review of textbooks could be improved by an increased focus on gender equality, potentially supported by public guidelines to tackle gender bias in instructional materials.

1.5.2. Improving the recognition of education, health and welfare (EHW) jobs and encouraging digital competencies

Specific actions can help to create more gender equality in participation in EHW (education, health and welfare) and ICT (information and communication technology) studies and training. Both of these fields are heavily segregated by gender and face noticeable labour shortages today and in future projections.

Limiting the sorting of female and male students and adults into different fields of study and different jobs involves improving the status of EHW jobs. Retaining more women and attracting more men in EHW jobs notably implies offering better opportunities for career progression through wage structures that reward professional development instead of tenure. This can, for instance, be achieved by incentivising successful completion of in-service training offering essential new qualifications with pay raises. Supplementary information campaigns (e.g. through adult learning, school career counselling, etc.) on such improved employment conditions can attract more men and women in these sectors.

In Estonia, teaching digital skills has been considered a national priority since the launch of the Tiger Leap programme in 1996. Since the mid-2010s, an impressive set of policies have been implemented to fully mainstream the theoretical and applied learning of basic and more advanced digital skills in the Estonian education system, from enhanced teacher training offer, to increased funding for ICT equipment in basic and upper-secondary education, to the decision in 2022 to make the teaching of digital competences mandatory in kindergarten. To ensure that the improved participation of male and female students in ICT activities translates into more girls choosing ICT careers, one could consider more systematically adopting a gender lens throughout the curriculum, for instance by increasing pupils’ and students’ exposure to female role models working in STEM fields. In France, a one-hour in-school intervention of female scientists strongly affected high school students’ perceptions and choice of undergraduate major.”

1.5.3. Gender mainstreaming in other parts of public life

To foster more gender equality in Estonia it is not only important to embed gender mainstreaming in education and life-long learning, but it is also necessary to engage the Estonian public in taking an active role in promoting gender equality in other aspects of life.

Establishing gender equality as a national priority and embedding it at the core of national policies can put it at the forefront of future policy making. This can include gender budgeting and a regular assessment of the impact of policies on men and women. It is important to embed such practice in the national budget in a long-term and sustainable perspective, rather than regarding external funds aimed at supporting short-term one-off projects.

1.5.4. Combatting gender-based violence

It is important to involve more Estonians in the fight against gender-based violence. Currently, awareness that intimate partner violence is an issue is relatively low. While nearly a majority of respondents (59%) in European OECD countries is willing to intervene when witnessing an incident of intimate partner violence, this held only for a minority of respondents in Estonia (37%) (Figure 1.7).

One approach to raise awareness around intimate partner violence is regular communication of how and why national policies combat such violence, potentially in the form of yearly events on strategic dates, e.g. on the International Day for the Elimination of Violence against Women. Such yearly information campaigns need to be accompanied by greater promotions of the reporting mechanisms available to the public, to encourage victims, witnesses, as well as (potential) perpetrators to report the violence they undergo, witness, or (intend to) perpetrate – which could potentially become a game-changer in the fight against gender-based violence (Chapter 6).

1.6.1. Women’s employment has been important for past economic growth, but not more than men’s in Estonia

Over the past 20 years, the gender gap in employment among Estonian men and women has barely changed. However, both men and women saw their employment rates increase in unison, which raised the overall labour input in the economy and thus may have had positive effects on aggregate output in the country. Indeed, Estonia experienced strong economic growth over the last two decades (3.93% growth in GDP per capita per year) (Chapter 7).

With the use of a growth accounting exercise, the link between changes in employment rates and economic growth over the last 20 years can be uncovered. In Estonia, the changes in women’s employment rates are estimated to have contributed roughly 0.40 p.p. to the average annual GDP per capita growth, which is somewhat lower than the contribution the similar increase in male employment rate had (0.57. p.p.). This is predominately due to the increase of the male working-age population, which means that in absolute numbers, the male labour force increased somewhat more than the female labour force. Across the OECD, however, women had a much stronger effect on average annual growth than men (0.28 percentage points relative to 0.08 percentage points) (Chapter 7).

The overall decline in working hours had a dampening effect on economic growth across the OECD and Estonia. While working hours among men generally decreased more than women’s hours in paid work, working hours among Estonian women declined about as much as those of Estonian men over the past 20 years. As a result, the changes in women’s working hours reduced economic growth by 0.26 percentage points each year in Estonia, while it increased growth marginally across the OECD overall (+ 0.03 percentage points) (Chapter 7).

1.6.2. Closing gender employment gaps can boost economic growth

Further rises in female employment participation, bringing these closer towards male levels, hold the potential of spurring further economic growth in the future. As such, Estonia could potentially generate a noticeable boost in economic growth until 2050 (in potential GDP per capita) when tapping more into the economic potential of women and closing the gender gaps in labour force participation rates and working hours. Such projections are based on a simplified version of the OECD Long-Term Model and various labour market scenarios on projected labour force participation trends. The obtained estimates result from a purely mechanical simulation and assume that any changes in labour market outcomes do not interact with factors outside of the model or have any indirect effects beyond its scope.

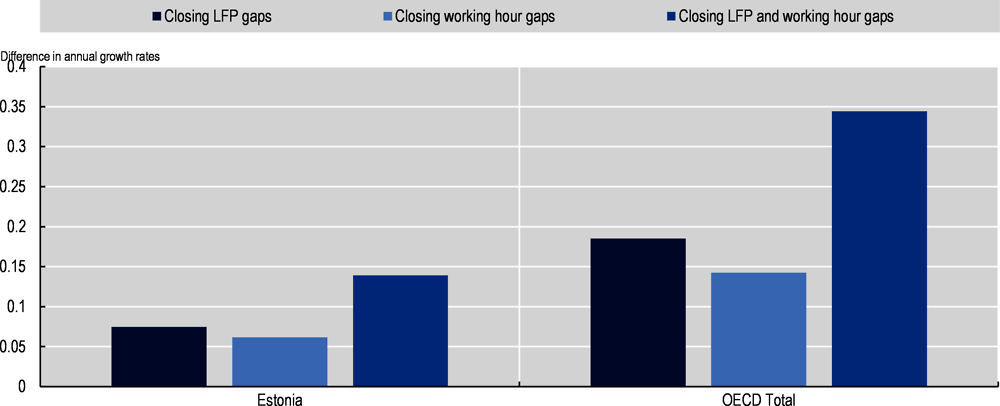

For example, if Estonia fully closed its gender gap in labour force participation by 2050, it could expect 0.7 percentage points of additional growth per year (Figure 1.8). The potential accumulated boost under this scenario could amount to 2.3% of additional GDP per capita in 2050. At the same time, closing the gender gap in working hours could increase annual growth by 0.06 percentage points and lead to 1.9% of additional GDP per capita in 2050. A joint closing of labour force participation and working hours gap is estimated to produce an additional 0.14 percentage points of growth each year – or raise GDP in 2050 by 4.3%.

While the growth potentials from closing gender gaps in the labour market are quite considerable for Estonia, they are noticeably larger in some other countries. For example, across the OECD overall, about 0.19 percentage points of growth each year could be expected if the OECD-wide gender labour force participation gaps would be closed by 2050. This is because Estonia already has a relatively small gender gap in labour force participation and working hours, and would thus benefit to a lesser degree than other countries with larger gaps. However, as the gender gaps on the labour market have been particularly persistent over the last 20 years, Estonia is missing out on a substantial boost to economic growth that could be unleashed if men and women had the same engagement and chances on the labour market.

1.6.3. Addressing Estonia’s particular gender equality and labour market challenges

The labour market scenarios discussed here do not say anything about the mechanism with which further gender equality and growth can be accomplished. For instance, as in many other countries, Estonia has relatively gender-segregated educational pathways. This segregation is particularly strong regarding STEM-studies (Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics) and may have a dampening effect on the overall productivity of women workers in the economy. With less gender stereotyping in education and a more equal sorting of boys and girls into educational fields, women could gain increased access to more productive jobs. This may subsequently boost annual potential economic growth per capita by 0.30 percentage points until 2050 (Chapter 7).

Estonian women carry out most of the unpaid work in and around the house. Such persistent gender norms and a traditional division of paid and unpaid work can have substantial effects on women’s opportunities in the labour market, e.g. through career breaks during career-defining periods (see discussion of the motherhood wage penalty above) and discriminatory behaviour towards women regarding hiring and career advancement. An equal sharing of unpaid work, as well as parental leave-taking, should increase women’s access to more productive jobs. The potential boost to potential GDP per capita growth until 2050 may amount to 0.33 percentage points per year (Chapter 7).

Health problems that impair the ability to work and reduce the quality of life become more prevalent as individuals age. As such, the health status of the workers becomes an important determinant of life satisfaction and labour market attachment at older ages. Estonia has a relatively large gender gap in life expectancy and expectancy of disability-free life years. As a result, and in sharp contrast to other OECD countries, Estonian women above the age of 55 are more likely to be employed than Estonian men of the same age. An increase of male life expectancy, coupled with a closing of the gender labour force participation gap among older workers, may boost the aggregate national output in Estonia by 0.03 percentage points per year until 2050. Naturally, as male life expectancy increases, the total population of Estonian males grows as well and a larger fraction of men will reach retirement age relative to the baseline scenario. Thus, annual GDP per capita growth decreases by roughly -0.10 percentage points until 2050, as the total economic output is divided by a larger population base, at the same time as aggregate GDP increases due to the productive contribution of a larger old age labour force.

If the labour force participation of Estonia would increase independent of male engagement on the labour market, thus not being bound by convergence to male rates as in other scenarios, Estonia could potentially expect even more growth than under a simple closure of gender gaps in labour force participation. For example, if female labour force participation would convergence to the rates found among women in Iceland, which have the highest labour force engagement in the OECD, GDP and GDP per capita would be boosted by about 6% relative to the baseline scenario for 2050. This corresponds to an additional 0.19 percentage points of average annual growth between 2020 and 2050 and is driven by particularly strong increases of labour force participation for younger women (aged 15-39) and those aged 60 to 69.

Policy recommendations for Estonia

Promoting more gender quality in households and on the labour market could be beneficial for Estonian men and women alike. A more balanced sharing of work and family responsibilities amongst fathers and mothers could increase family well-being and enable men and women to reach their full potential in the labour market. Equal opportunities for women will also play an important part in supporting overall increases in productivity and spur elevated, more inclusive, economic growth. A more gender-equal society will also have different social benefits, including, better male health and fewer women exposed to partner violence. Estonia is well-positioned to tackle its challenges to more gender equality in society. To further support more gender equality in Estonia and to achieve higher social and economic well-being of women and men alike, this review recommends Estonian policy makers to:

Encourage a more equal division of the leave entitlements among parents. Estonia has recently extended paternity leave from 10 working days to 30 calendar days. Parents can take parental leave in turn, while 60 days can be taken simultaneously by parents since 2022. The parental benefit can be used on a daily basis until the child reaches the age of three. While parents were previously only able to decide on the 71st day following the child’s birth which parent would receive the parental benefit, fathers with a one-month-old child will now have the option to use the shared parental benefit. Reform increased flexibility in the use of parental leave and may make it easier for fathers to engage in childcare. To further stimulate fathers to engage in childcare, reforms could extend parental leave periods for the exclusive use by fathers – for example, through a “father quota” system. Reform could be introduced gradually, so that the leave period reserved for fathers is initially increased to 3 months, while the paid leave period mothers can take overall after childbirth is reduced to 15 months. To reduce gender gaps in labour market outcomes, it is key that the parental system generates a more equal share of parental leave entitlements among parents.

Provide a continuum of childcare supports to parents. Estonia has a comprehensive system of work-life balance supports for parents, and net childcare fees for parents are among the lowest in OECD countries. However, access is an issue for many families with very young children: almost every tenth child aged between 18 and 36 months does not get a childcare place. Despite the demographic trends, which will exert downward pressure on the demand for childcare places, more public investment in formal childcare is required to ensure that both parents can return to full-time work when the period of parental leave runs out, or when parents want to return to work before that time. At present spending on family benefits focuses on cash support rather than investing in relevant services: there is a case for introducing a greater focus in family support on family services, including formal childcare.

Enshrine pay transparency policies on the Estonian labour market. A renewal of the pay transparency measures originally planned under the Gender Equality Act and Other Acts Amendment Act of 2016 could mandate a firm-level reporting of the gender composition of the workforce and pay differences at different job categories. To ensure compliance with pay transparency, reporting measures could oblige employers to make their gender gap statistics publicly available. Government bodies, such as Statistics Estonia, could be tasked with the responsibility of utilising administrative data to compute firm-level gender gaps.

Complement pay transparency with other measures. Pay transparency policies could be used to enshrine the concept of “equal pay for work of equal value”. Mandating pay transparency reporting along a gender-neutral job classification system may achieve this. A government body, such as a Pay Competence Centre at the Labour Inspectorate, could validate and verify such a system. Online training courses directed at employers, for example in the framework of the Virtual Competence Centre at the Ministry of Social Affairs, could raise awareness and promote gender equality among key stakeholders.

Ensure that gender stereotypes are not perpetuated in the classroom. Compulsory pre- and in-service training on gender equality for future and incumbent teachers, career counsellors and youth workers at all levels and in all types of schools and higher education institutions can reduce gender stereotyping in education. Moreover, while avoiding spreading gender stereotypical worldviews is a matter of consideration in the review process of textbook proposals, and the curricula of both basic and upper secondary schools in Estonia define gender equality as a core value, there is no efficient national mechanism to prevent a textbook full of gender stereotypes from reaching children. The review of textbooks could thus be improved by an increased focus on gender equality. To enhance enforcement, the Ministry of Education and Research could publish guidelines to tackle gender bias in instructional materials.

Reduce gender-segregated sorting in education and respond to future labour demands. Teaching digital skills has been considered a national priority in Estonia since the launch of the Tiger Leap programme in 1996. Since the mid-2010s, an impressive set of policies have been implemented to fully mainstream the theoretical and applied learning of basic and more advanced digital skills in the Estonian education system, leading the share of primary and lower secondary schools with an elective subject focusing on ICT to reach 77% in 2020/2021, up from 50% in 2015/2016. To ensure that the improved participation of male and female students in ICT activities translates into more girls choosing ICT careers, one could consider more systematically adopting a gender lens throughout the curriculum, for instance by increasing pupils’ and students’ exposure to female role models working in STEM fields. To increase the attractiveness of EHW (education, health, and welfare) jobs, one could link pay rises with successful in-service training for new essential qualifications.

Involve all Estonians in the fight against gender-based violence. Regular communication of how and why Estonian policies combat gender-based violence at high coverage events must be accompanied by strengthening the promotion of reporting mechanisms, to encourage victims, witnesses, as well as (potential) perpetrators to report the violence they undergo, witness, or (intend to) perpetrate.

References

[2] European Commission (2018), Gender equality 2017, Special Eurobarometer 465 - June 2017, https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2838/431877.

[4] European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights (2020), Fundamental Rights Survey 2020, https://fra.europa.eu/en/data-and-maps/2021/frs.

[3] OECD (2021), OECD/AIAS database on Institutional Characteristics of Trade Unions, Wage Setting, State Intervention and Social Pacts (ICTWSS), https://stats.oecd.org/index.aspx?DataSetCode=CBC.

[1] OECD (n.d.), OECD Employment Database, https://www.oecd.org/employment/emp/onlineoecdemploymentdatabase.htm.