Executive Summary

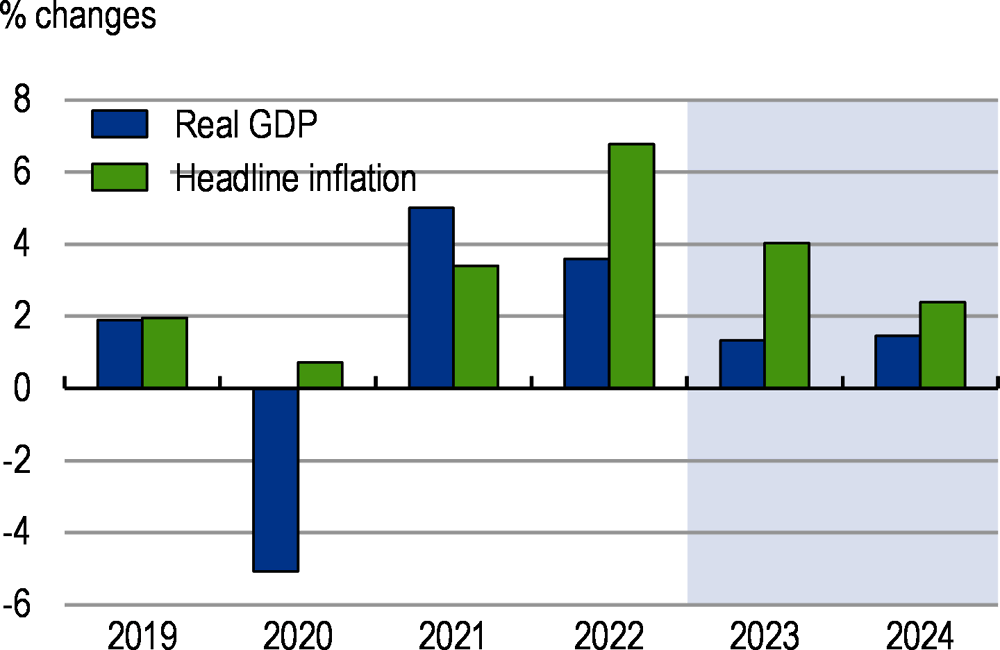

Canada’s economy recovered from the COVID-19 pandemic, but inflation has since surged. Charting a path towards lower inflation without sharp disruption to economic activity and employment is challenging given the uncertainties and risks.

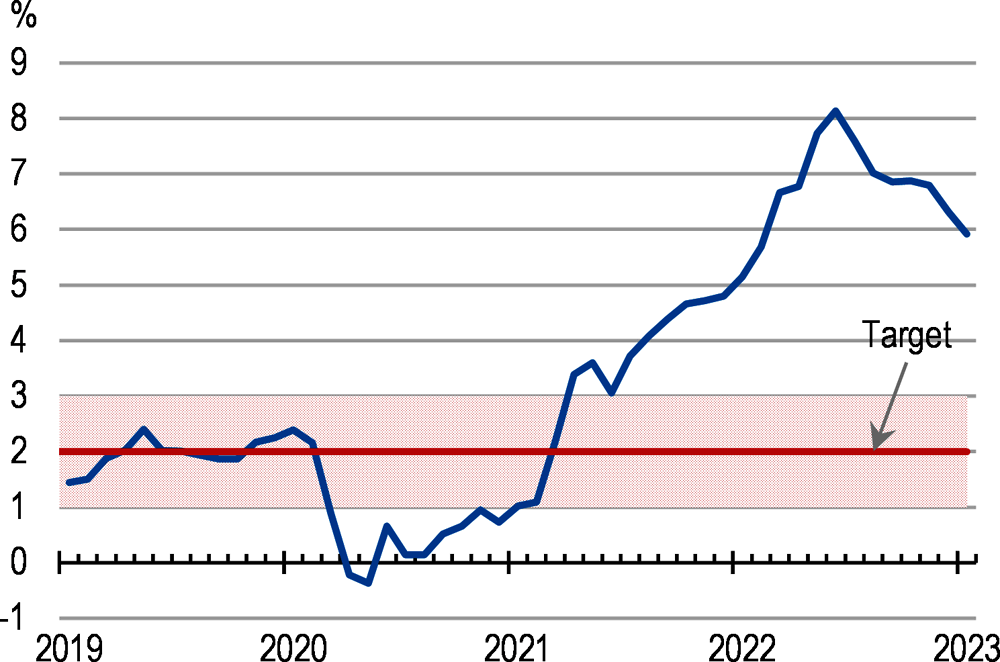

By the beginning of 2022 Canada’s economic output was above pre-pandemic levels. The rate of unemployment subsequently hit record lows, contributing to wage and price pressures, with headline consumer price inflation well above 3% (the upper bound of the Bank of Canada’s target range). The impact of Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine on global food and energy prices further fuelled inflation, which peaked at 8.1% in June 2022 (Figure 1).

Energy independence and limited direct ties to hard-hit economies have shielded Canada from some of the effects of the war. Canada has actively supported Ukraine, including through sanctions on Russia, an emergency immigration stream, military support and loans.

The Bank of Canada has been tightening monetary policy since spring 2022. This has tempered demand and helped keep long-term inflation expectations anchored. Inflation has started easing and OECD projections envisage it reaching target by the end of 2024. Annual output growth of 1.3% is expected in 2023 and 1.5% in 2024 (Figure 2).

Risks are elevated. As an open economy, Canada’s main risk is a rapid slowing in global demand. Canada is also exposed to heightened volatility in commodity and financial markets from Russia’s war against Ukraine. Domestically, uncertainty in how consumer spending will evolve remains elevated. Higher interest rates, softening home values, and uncertainty in the employment outlook point to households becoming more cautious. Rising interest rates exacerbate macro-financial risks given high household debt. However, financial-stress indicators generally remain low. Like elsewhere, there is growing concern about volatility and reduced liquidity in fixed-income markets.

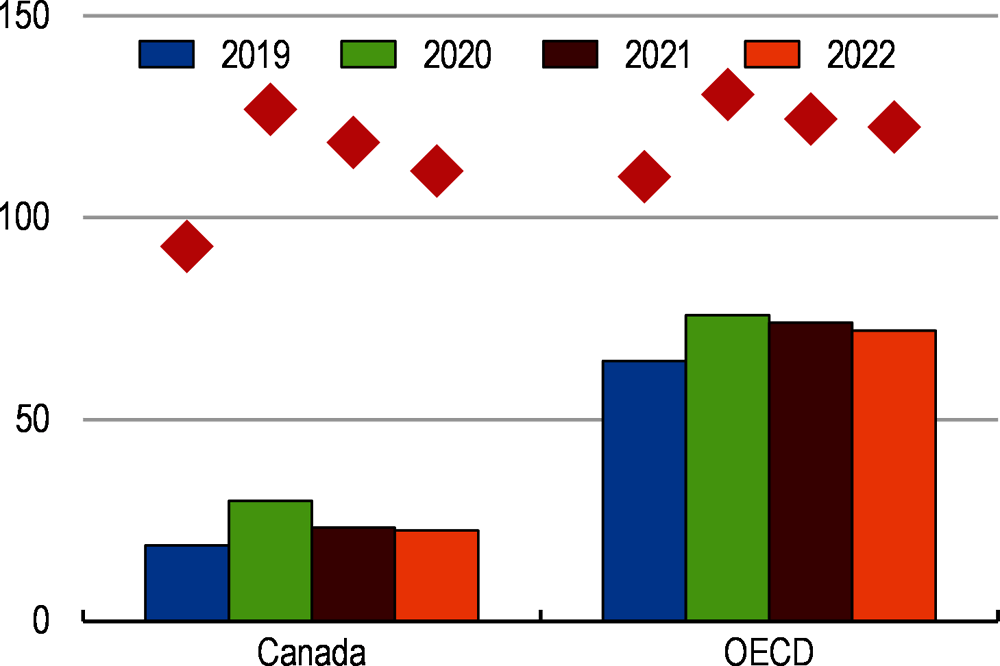

Canada’s fiscal balances are expected to improve further. However, continued rapid improvements over the longer run will be more challenging given large multi-year spending pressures.

Fiscal deficits are shrinking. For 2022, the unwinding of COVID-19 support, recovery in revenues from the lifting of lockdowns and other constraints, plus revenue boosts from higher commodity prices, have helped reduce deficits. This is despite new spending, including temporary support for Canadian households in the face of rising living costs and investments to further the green transition. A general government deficit of 1.7% of GDP is expected for 2022, after 11.4% in 2020. Public debt still stands above the pre-pandemic level (Figure 3), but is expected to decline rapidly. Canada fares better than most countries in this regard.

Tax reforms and improved public spending efficiency could boost growth potential and sustainably lower the fiscal deficit. Recent budgets have included savings through public spending efficiency gains that remain to be detailed. Recent large commodity price increases raise questions about the adequacy of taxation of windfall gains and how related public revenues are spent, particularly in the provinces. Long-term reform should aim to reduce economic distortions from the tax system, including through less reliance on taxes on income and more use of indirect taxes.

Canada’s productivity and investment growth has weakened relative to the United States and other leading OECD economies. Lowering internal trade barriers and better competition policy would help improve performance.

Inter-provincial non-tariff trade barriers are high. Canada is unusual in the degree to which differences in technical standards and regulations across sub-national jurisdictions hamper flows of goods and services. The barriers extend across many activities, including the dairy sector and legal and accounting services. Similarly, non-recognition of certain qualifications between provinces reduces the efficiency of Canadian labour markets and limits mobility.

There is scope to improve competitiveness. Foreign ownership restrictions remain a feature in some sectors. In addition, competition law must change to handle challenges related to Big Tech. These include barriers to entry linked to data access, abusive and exclusionary practices, and lock-in of consumers and businesses to service providers.

Money laundering remains an issue. Canada is strengthening its capacity to counter financial crimes, including through better corporate transparency measures. Russia’s war against Ukraine has also increased attention on Russia-linked money laundering.

Cost-of-living increases are eroding real incomes. Successful implementation is key for a new national childcare reform. Deep disadvantage among Indigenous peoples needs to continue to be addressed.

Temporary measures are providing cost-of-living relief, but challenges remain in affordable housing. Some provincial measures are not targeted to the most vulnerable groups. A new set of federal measures helping with house purchase for low-income households, and boosting the supply of affordable housing, is being rolled out.

Implementation of the childcare reform will be challenging. The reduction in childcare costs and increases in the number of childcare places will take time to achieve given the substantial investment required. Also, monitoring the reform will be complex due to the large number of childcare suppliers across sub-national jurisdictions. Successful implementation would strengthen labour force participation, particularly among women, and boost living standards.

Significant socio-economic gaps between Indigenous peoples and non-Indigenous Canadians remain. Government policy continues to expand efforts to advance reconciliation, close gaps, and improve the living standards of Indigenous peoples. There is a need to continue supporting self-determination through transfer of powers to community governments and co-developing policy.

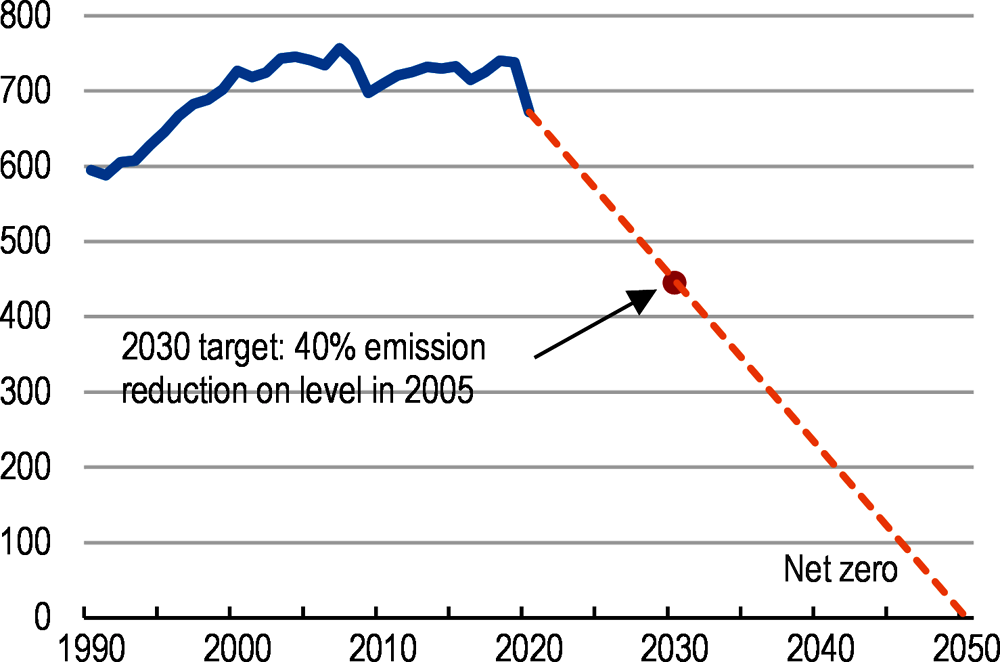

A new climate plan with a revised 2030 target is in place to accelerate Canada’s transition to net zero by 2050 (Figure 4). Achieving net zero requires deep energy savings and replacement of fossil fuels with clean energy. Residual emissions will need to be trapped and stored or offset with sequestration elsewhere.

Emissions pricing has a central place in the national emissions reduction plan. In 2023, strengthened minimum national stringency criteria take effect. These criteria include an increasing carbon price trajectory to CAD 170 per tonne of carbon dioxide equivalent emissions in 2030. Further tightening of stringency criteria, beyond that achieved in the latest update, would help harmonise and strengthen abatement incentives across federal, provincial and territorial carbon pricing schemes.

While much of Canada’s electricity comes from hydropower, more could be done to decarbonise power. Provinces will need more wind and solar energy to meet new demands on grids. Some provinces sell electricity at low regulated prices, which reduces returns to renewable-energy investment and discourages energy efficiency. Reforms to pool power and transition to market-based pricing could lower the cost of the green energy transition.

Oil and gas extraction contributes one quarter of Canada’s emissions. Together with technology support measures, the federal government aims to strengthen pricing signals for greener production. This should be done within current carbon pricing systems.

Road transport is a major source of emissions. Beyond measures to encourage electric vehicle take-up and reduce emissions from conventional vehicles, a policy focus is needed on reducing car dependency. Road user charging and fewer barriers to housing supply in cities could support the appeal and accessibility of public transport.

Canada uses large amounts of energy to heat buildings. Hitting emissions reduction targets will require, along with market-based incentives, fast adoption of tough energy standards for new buildings and rapid retrofitting of existing ones. Better information on buildings’ energy performance would improve incentives to upgrade energy-intensive homes and other buildings.

Reducing climate change impacts is important. Average temperatures across Canada increased by 1.9 degrees Celsius from 1948 to 2021. This is double the global average rate of warming. Canadian communities face increased risk of damage from flooding, melting permafrost and heatwaves in the years ahead.