2. A holistic policy framework for achieving a balanced sharing of paid and unpaid work

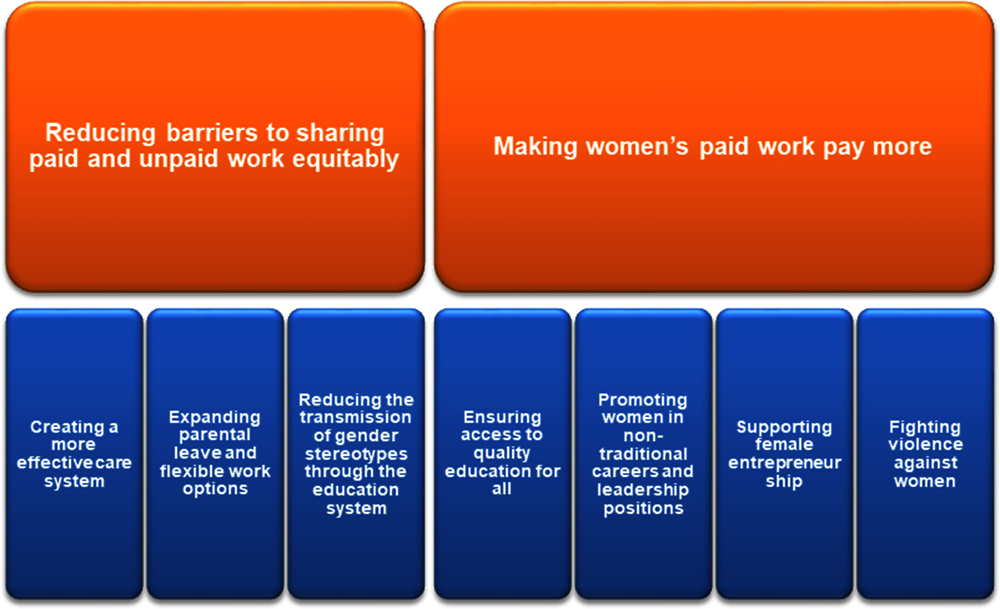

This chapter argues that achieving a better sharing of paid and unpaid responsibilities between men and women in Chile requires a comprehensive policy strategy and presents a holistic framework for its development using two policy axes. The first axis comprises the policies aimed at reducing the barriers that stand in the way of a more equitable division of time and responsibilities between men and women: Creating a more effective care system, expanding parental leave and reducing the transmission of gender stereotypes through the education system. The second axis includes the policies that aim to increase the participation of women in the labour market through ensuring that women’s paid work pays more: Ensuring access to quality education for all, promoting women in non-traditional careers and leadership positions, supporting female entrepreneurship and fighting violence against women. The chapter reviews each area in detail and provides policy insights for possible improvements.

As discussed in Chapter 1, many societal, institutional and economic factors are behind the higher unpaid work burden of women and their less favourable economic outcomes. Policy changes, as well as shifts in attitudes, have already reduced gender gaps in the labour market and have practically eliminated them in basic education. Nonetheless, some girls in Chile continue to leave school prematurely, and many women steer away from better-paid scientific and technical careers, are less frequently employed in quality jobs, work more frequently in the informal sector and earn less money. Substantial welfare and income gains would accrue to both men and women by further reducing these gaps. A more equitable division of paid and unpaid work is therefore a worthwhile policy goal.

Given the variety of drivers of the current division of paid and unpaid work, Chile needs to implement a comprehensive policy strategy to move towards a more balanced sharing of activities between men and women. As a contribution to such a policy strategy, this chapter puts forward a holistic framework, building on two policy axes, namely the following:

On the one hand, the policies aimed at reducing the barriers that currently stand in the way of a more equitable division of time and responsibilities between men and women, as distinguished from

On the other hand, the policies that aim to increase the participation of women in the labour market through ensuring that women’s paid work pays more.

The first policy axis focuses on reducing the burden of unpaid work that women have to carry out and the hurdles that make it difficult to share paid and unpaid and paid work more equally between genders. Key examples of the policy areas encompassed by this axis include the expansion of the public care system for both children and the elderly; introducing, or strengthening the regulations governing parental leaves and flexible work solutions; and promoting a gender-neutral approach at all levels of education.

The second policy axis spots light on the policies that contribute to reduce the gender gap in labour income, lessening, in turn, the incentive for women to spend long hours on unpaid work and freeing more hours for them to destine to paid work. Key examples of these policies include addressing any remaining barriers for all groups of girls to access quality education; the efforts to increase the share of women who work in the formal sector and have access to quality jobs; and fighting violence against women in public spaces and the workplace.

Figure 2.1 provides the diagrammatic illustration of the policy framework. The two policy axes are mutually reinforcing, in the sense that the interplay of positive policy changes across them will lead to significantly increasing the number of women who could and would like to work outside the home and that of men willing to take over caring and domestic tasks.

While not the only policies that could contribute to these changes, the specific areas addressed in this report emerged as the most relevant, in terms of both potential impact and feasibility, during a project’s fact-finding mission to Santiago de Chile. The reminder of the chapter reviews each area in detail starting with an assessment of the challenges and existing policies. A set of policy insights will follow, building on the lesson from the international experience and the OECD knowledge of international practices.

Creating a more comprehensive care system

Caring activities for babies, children and disabled, ill or elderly adults make for an important share of unpaid domestic work. In the absence of a comprehensive national care system, the bulk of these activities falls primarily on women. On a typical day, women in Latin America spend in average 1.5 more time on care activities for members of their own household than men do (3.4 hours against 2.1 hours). In Chile the gap is wider, since women spend almost twice as much time on these activities (3.0 hours against 1.6 hours) (INE, 2016[1]). This is more than in Argentina (where women spend 1.1 more time on care activities than men do) and less than in Peru (where women spend 2.2 more time on these than men do) (ECLAC, 2018[2]). The availability of affordable public and private care services could contribute to a re-balancing of the care burden between genders, if complemented by broader efforts to shift attitudes, along with the policies to increase parental leaves and part-time work opportunities for men and women.

Although Chile has a mix of private and public provision of childcare, important challenges remain. According to Article 203 of the Labour Code, employers with more than 20 female workers must provide childcare assistance to children under the age of two. This obligation discourages employers from hiring women formally beyond the threshold and leaves women working for smaller or non-complying employers uncovered. The Ministry of Labour would like to replace the current 20 female workers threshold by a more universal system, accessible to all workers and poor women, financed through a 0.1% contribution on taxable salaries.

In addition to the above provision, the programme Chile Crece Contigo extends the coverage of childcare to poor working mothers and student mothers, who belong to the 60% most vulnerable women according to the needs-adjusted income information about their household contained in the Social Household Register. Another programme, named the 4 to 7 programme, addresses the care gaps of school-aged children whose parents working hours are longer than school hours. A similar programme targets mothers of children aged 6 to 13, who belong to the three lowest income quintiles. Both programmes have a relatively restricted coverage at present, limited to a small number of municipalities (Chile Atiende, n.d.[3]).

Families not covered by the above service options can opt for either (formal or informal) private daily care, or care provided by another family member. Informal care options are prevalent in rural areas, where many employed women – in agricultural co-operatives, for example – continue to entrust their children to relatives, even though they are eligible to receive a voucher for childcare. The same is true among single women who live within an extended family.

Support for the care of elderly and disabled individuals is predominantly restricted to the 60% most vulnerable households. The mission of the Chile Cuida, a sub-system of the Inter-Sectorial Social Protection System, is to accompany and support people in dependent situations, as well as their caregivers, and to promote networks through different services. Twenty municipalities participate in the system, which provides, among other services, technical assistance and training (Ministerio de Desarrollo Social y Família, n.d.[4]). A bill, currently under approval, foresees the creation of a disability insurance system relying on salary contributions of 0.2%.

Expanding opportunities of access to care could benefit both carers and the cared for. The long-term educational and social benefits of early childhood education and care may be particularly strong among children from disadvantaged families – often of cultural and linguistic minorities, for example – notably, by supporting preparations to formal schooling in primary school and preventing psychosocial problems (Nores and Barnett, 2010[5]; Heckman et al., 2010[6]). In Chile, girls and particularly boys who attended formal early childhood education and care programmes tend to perform strongly in standardised tests once they are in primary school (Cortázar, 2015[7]).Conversely, carers and institutions for disabled or elderly citizens or family members may be unprepared and overstretched, putting elderly and disabled people’ mental and physical health at risk. In extreme cases, the resulting overload can contribute to cases of repeated violence against elderly people, including relatives. A 2012/2013 survey of the elderly in Veracruz and Santiago revealed that more than half of dependent seniors had experienced psychological violence and one in seven had suffered some form of neglect (SENAMA, 2013[8]).

Policy insights

Expand formal early childhood education and after-school care. The creation of a more universalised early childhood care system financed through a general employer contribution would be a step in the right direction. Under the current bill, employers of any size would contribute 0.1% of their employees’ salaries to a central fund. Mothers and single fathers working more than 15 hours a week as employees or as self-employed workers affiliated with the social protection system would have access to the benefits. After applying, they could choose to send their children to a public or a private provider, the latter pending accreditation by the Ministry of Education. Costs of up to CLP 245 000 (around USD 315) per month would be covered by the fund. If the cost of the private day-care provider exceed this sum, parents would bear the remainder of the cost (Yévenes, 2018[9]).

Although the abolition of the size threshold would reduce the disincentives for hiring women, and could lead to a reduction of the wage penalty that women working for larger employers experience (IDB, 2015[10]), the current reform project has also attracted a number of criticisms. Some critics note that the new regime would not be universal, since it would exclude several groups, such as, for example, the students, along with part-time and public sector workers (although, in principle, the latter should have access to employer-provided childcare, this is not always the case). Partly related, other observers criticise the definition of childcare assistance used, according to which qualifying for the benefit depends upon the payment of a contribution, rather than being a basic right that is freely accessible by the most disadvantaged. Others note that, by making access contingent on labour status, the bill further entrenches the view that obligations for childcare is a prerogative of the workers, rather than being a social obligation. Finally, some lament that the voucher does not cover the full cost of private day care and that it undermines the public childcare sector.

A first step to addressing the above criticisms would be to grant the benefit to any child under the age of two, regardless of the labour status of the primary caregiver. As a further step, after the introduction of a right to care for under-two year olds, the right could also be extended to older children until they reach school age, although this would require a substantial expansion of the childcare infrastructure. Increasing the spots available in public day-care programmes can be one important way to expand coverage. Evidence from many OECD countries suggests that publicly funded childcare tends to have a more uniform quality and offer better working conditions to childcare workers (Moussié, 2016[11]). The process of opening new public day-care centres can be gradual, giving sufficient time to train and hire qualified personnel and to expand the public budget devoted to early childhood care and education. At the same time, private providers, which adhere to quality standards, can continue to play a role. Given that market rates for private day-care often exceed the planned maximum amount, lower- and middle-income families should have priority of access to public day care. In areas where these are over-subscribed and where a rapid expansion is impossible, the government could consider an additional subsidy for low- and middle-income families linked to the market rate of private providers.

Small companies that are currently below the 20 female employee threshold might oppose the introduction of an additional mandatory contribution, in particular at a time where they are struggling because of the COVID-19 pandemic and its economic fallout. One option to address this concern could be to phase in the introduction, with longer lead-up times for companies that can demonstrate that the COVID-19 crisis strongly affected their revenues. In addition, an information campaign demonstrating the benefits to the firms themselves could support the introduction of the new regime. For example, case studies from textile companies in Jordan and Viet Nam showed that staff turnover and sick leave declined by a third and 9%, respectively, when the companies started offering workplace childcare. A recent report by the International Finance Corporation, provides further examples on the business case for employer-supported childcare, by showing the benefits that employers gained from providing the service (International Finance Corporation, 2017[12]).

In addition to expanded care options for pre-school children, families also need more options for qualified after-school care. To this effect, a further expansion of the 4-7 programme to all municipalities and income quintiles would represent a desirable option. This would expand the opportunities for parents to work full-time.

Investing in long-term care. Lessening the burden of care for elderly and disabled family members can go a long way towards supporting women’s access to labour markets. Ideally, this would require expanding the Chile Cuida programme, both geographically and across income groups. As one tool in this direction, easing access to information on services available locally can be a way to point families towards resources that could help them. For example, in La Plata in Argentina, a network of residents, academic experts and service providers created a website to provide such information. Respite care and training, aimed at providing short-term relief to families of any income category, is another tool. In Belo Horizonte in Brazil, for example, social and health workers spend a week in a family to allow carers to recover and to learn how to best care for their relatives (UN Women, 2017[13]). In addition to such temporary relief efforts, it is important to invest in long-term care infrastructure and insurance. With an ageing population, the need for more support in the form of regular visits by trained care workers, or of institutional care, is likely to increase. In this context, public oversight is a key to ensure the enforcement of care standards, as well as labour standards, for paid care workers, many of whom are women. A long-term care insurance programme, financed either through taxes or through a social insurance, could help pay for care. To keep costs in check, the eligibility and benefit limits can initially be quite restrictive, paying only in cases where the family is not able to finance the care for severely ill or disabled family members (Rhee, Done and Anderson, 2015[14]).

Expanding parental leave and flexible work options

Parental leave policies affect family decisions about the division of paid and unpaid work between partners. When there is no maternity leave, mothers may have to drop out of the labour force and subsequently find it difficult to re-enter. In OECD countries, the female employment rate rises slightly with the length of the statutory maternity leave but starts to fall when the duration exceeds two years. This underscores that beyond a certain limit, excessively long maternity leave periods may be counter-productive, leading to a widening of the gender employment gap, rather than shrinking it (Thévenon and Solaz, 2013[15]). It also brings to attention the important balancing role that fathers can play by taking paternity leave and their contribution to counter the frequent pattern whereby couples revert to a traditional division of labour when they become parents. For example, in Norway, couples whose child was born four weeks after the introduction of paternity leave reported fewer conflicts about the division of unpaid work and some improvements in the sharing of housework tasks than couples whose child was born just beforehand (Kotsadam and Finseraas, 2011[16]). Evidence from Sweden and Spain likewise suggests that couples split unpaid work more equally following the introduction of more gender-equal parental leave policies (Hagqvist et al., 2017[17]). A detailed analysis from Germany shows that fathers who took parental leave decreased their paid work afterwards and increased the hours devoted to childcare. However, only fathers who took more than two months of leave also increased the involvement in other types of unpaid work (Bünning, 2015[18]).

The leave available to parents in Chile exceeds the regional average. It involves a paid maternity leave of 18 weeks, which exceeds the minimum defined by the 2000 ILO Convention No. 183 on Maternity Protection and fulfils the recommendation of ILO Recommendation No. 191 (Figure 2.2). In addition, as one of the few countries in Latin America, Chile offers 12 weeks of parental leave. Half of this parental leave is reserved for mothers, while the other half can be taken by fathers as well. Part-time parental leave of 18 weeks at 50% of net pay is also an option.

In other ways, however, the leave system is not as flexible as elsewhere and lacks coverage. Six weeks of maternity leave have to be taken prenatally and mothers and fathers cannot take parental leave concurrently. Since the costs of maternity leave are borne by the social security system, informal workers, not affiliated with the system, cannot benefit. Detailed analysis of the coverage capacity of the system suggests that in 2015 only 44% of mothers received maternity benefits (IPC-IG and UNICEF., 2020[19]). During the COVID-19 crisis, the government and the opposition co-operated to pass a law to extend paid parental leave to 90 days. To be eligible, the regular parental leave had to end after 18 March. Moreover, primary caretakers of children born after 2013 can ask for a leave of absence during which they are entitled to receive emergency family assistance (24 Horas, 2020[20]).

Dedicated paternity leave at childbirth in Chile only amounts to five working days, though it can be extended using part of the parental leave. The five days are slightly above the regional average, but far below the OECD average (Figure 2.2). However, it is important to note that the OECD average of around eight weeks reflects in part the extremely high entitlements of one year of paternity leave in Korea and Japan. Very few men in either of the two countries take any paternity leave, let alone during a one year period (Rich, 2019[21]). In Chile, the Commission on Women and Gender Equity launched an initiative to increase paternity leave to 30 days, 15 of which would be taken straight after the birth and 15 at any time in the first six months (Cámara de Diputadas y Diputados, 2019[22]).

Once back to work, parents have limited options to ease the time-crunch of simultaneously working and taking care of children. At 45 hours for full-time and 30 hours for part-time work, maximum work hours are above the standard work week of 40 hours common to many OECD countries. In addition, many workers work longer hours. In Latin America in the mid-2010s, 21.4% worked more than 48 hours and 8.1% worked more than 60 hours (ILO, 2018[24]). In Chile in 2013, 17% and 8% of male and female employees, respectively, worked more than 48 hours per week (Yañez, 2016[25]). The respective share increased to 29% and 19% among own-account workers. These figures do not take into account the time for commuting and the – at least – ten hours that a full-time worker normally devotes to childcare. Unsurprisingly, in this context, many families opt for the traditional one-breadwinner model: as depicted by Table 1.1, Chapter 1, in nearly half of two parent households with at least one child under the age of 14, one person does not work at all and this is typically the woman.

Few Chileans benefit from flexible work options. The recently introduced Act on Distance Work and Teleworking (March 2020) represents a step in the right direction, since it stipulates that the workers who opt for this arrangement benefit from all rights established in the Labour Code, while the right to disconnect is also recognised (ILO, 2020[26]). A pilot project launched by the National Institute for Industrial Property in 2017 investigated the possibilities of teleworking in the public sector (Soto et al., 2018[27]). In addition to recognising the importance of the quality of the physical and technological infrastructure as a pre-condition of success, the pilot project identified the crucial roles played by effective strategies of communication and training to engage civil servants. In Europe, around a third of employees can decide when they start and stop teleworking with a margin of autonomy, and more than 60% can take one or two hours off for personal or family reasons (OECD, 2016[28]). However, teleworking was not particularly common in Europe prior to the COVID-19 crisis: only one in five employees in 2015 had worked from home at least once over the 12 months prior to the outbreak.

Policy insights

Establish reserved paternity leave weeks as part of parental leave. Although Chile already has parental leave that either men or women can benefit from, as elsewhere, few fathers actually take the leave. Several European countries (including Iceland and Sweden) have successfully boosted their take-up through reserving a certain share of the parental leave for fathers, meaning that the total leave that a couple can use is longer if both take it. Another policy option is to lengthen paternity leave, which can per definition not be transferred to the mother (OECD, 2019[29])

Support the policies to increase the coverage of maternity and paternity benefits by stepping up the momentum of the broader policies to strengthen formalisation. This is important to ensure that parental leave be accessible to all workers, including the less protected ones. Currently, many new parents in Chile are not entitled to paid parental leave because they work without a formal contract and lack social insurance coverage. This situation underscores that the enforcement of parental leave arrangements would hardly generate sizeable results in terms of coverage if conducted in isolation from the broader policies to strengthen formalisation in Chile.

As a key priority, it would be important to keep the momentum of ongoing policy efforts to boost formal employment. Although an analysis of the policies to achieve this long-term objective is beyond the remit of this work, the broad requirements include making social security contributions progressive, increasing labour inspections and accurate monitoring of results (OECD, 2018[30]).

As part of these contextual policies, the government could consider prioritising sectors known for the relatively widespread presence of informality and the over-representation of female employment. These include a range of service activities, from personal care and household services, for example, to restaurants and hotels. As one regional example in the particular area of household services, Argentina has introduced a comprehensive set of measures to extend the coverage of social protection to domestic workers. These involve the introduction of mandatory written contracts, the dissemination of booklets that describe domestic workers’ rights, and the possibility for the employers to deduct the social security contributions paid on behalf of the domestic workers. These initiatives combine with awareness raising campaigns, with letters being written to high-income households reminding them of their obligation to declare any workers (Lexartza, Chaves and Cardeco, 2016[31]). If Chile were to follow a similar approach, it could consider providing tax-funded benefits to allow informally employed women eligible for the Chile Crece Contigo programme – which includes the promotion of active parenthood among its missions – receiving some limited paid benefits to take time off their jobs. Another potentially attractive option, particularly to the self-employed, could consist in the introduction of a contribution subsidy again intended to allow taking time off jobs.

Strengthen flexible work options. Depending on the type of job, flexible starting times and teleworking can reduce the time crunch that parents experience due to long working hours, commutes and family obligations. Compared to many other countries in the region, Chile has better prerequisites for teleworking in terms of its internet infrastructure and its recent teleworking laws have positive features. The government can encourage this process even further through multiple measures. For example, it can financially support those firms willing to invest in their ICT infrastructure; provide digital skills training in rural areas; and implement information campaigns that show the benefits of teleworking while also equipping managers with the skills on how to communicate effectively with employees that they see less frequently. (OECD, 2020[32]).

Reducing the transmission of gender stereotypes through the education system

There is a vast literature on attitudes about gender roles, how they are transmitted to children, including the role that stereotypes play in influencing the educational and occupational choices of girls and boys (OECD, 2012[33]; Karlson and Simonsson, 2011[34]; Wahlstrom, 2003[35]). As noted above, girls may shy away from choosing educational tracks and occupations perceived as traditionally masculine, such as STEM degree programmes (OECD, 2015[36]). Given that occupations characterised by a strong presence of male workers are often better paid, these choices can permanently hamper women’s earning potential (Kunze, 2018[37]). At the same time, boys brought up to believe in traditional gender roles may gravitate away from care professions (OECD, 2017[38]), and may be less willing to participate in housework and child care activities once they are adults (Lachance-Grzela and Bouchard, 2010[39]).

A stereotype-free educational approach can allow boys and girls acquiring full awareness of their strengths, along with the tools to nurture them so as to be able to pursue their interests and aspirations freely throughout the life cycle (UNESCO, 2004[40]). This positive approach rests on two notions:

The first is that the education system has a key role to play in tackling the persistence of gender stereotypes (Bousseau and Tap, 1998[41]; OECD, 2012[33]). For example, even though girls have gained access to schooling on a similar scale to boys in many countries, curricula and school materials have not followed through, implying that the representation of gender roles continues to be the same, using the old archetypes. Research has shown that in textbooks, men often appear in a wide variety of professional (paid) roles and women in domestic (unpaid) roles (EU, 2012[42]). A stereotype-free educational approach can significantly help addressing these gaps and their transmission between generations.

The second concept assumes that the potential for teachers to support students’ self-image, confidence and life paths remains largely underused, at present. A number of studies reveal that the attitude of the teachers affects the interest of the students in school subjects, influencing, in turn, career orientations (OECD, 2012[33]; OECD, 2015[36]). If teachers do not trust girls’ scientific abilities and provide them with less encouraging feedbacks, for example, girls’ success and interest in these subjects can be reduced (OXFAM, 2005[43]) (OXFAM, 2007[44]). For Chile, a study by the Ministry of Women and the National Women’s Service (SERNAM) (2009[45]) showed that teachers often address classes using masculine forms (such as “boys” and the male forms for all children and students, regardless of the gender). When giving examples, they tend to confine female characters to the “private world” spheres, namely the domestic, maternal and care settings, with male characters placed in the “public world” settings where fully-fledged economic activities take place.

Addressing discriminatory practices in the educational sector is a key component of the broader policies for promoting equal opportunities for men and women that the Chilean Government is pursuing. The efforts to revise the national curriculum date back to the turn of the century. They involved initiative aimed at levelling the visibility of both genders in textbooks, at promoting more participatory work methodologies in the classrooms, and widening the recourse to mixed work groups. More recently, the 2014-18 government programme recommended a gender-aware approach throughout all educational levels. In addition, the initiative Eduquemos con Igualdad (Let’s educate with equality), launched in 2016 by the Ministry of Education and Comunidad Mujer – a civil society organisation that promotes the rights of women – included guidelines for tackling educators’ gender biases and behaviours and for strengthening the engagement of parents in the creation of a gender-sensitive education (MINEDUC, 2018[46]). As another milestone, the 2015-18 plan on “Education for Gender Equality” identified patterns that reproduce gender stereotypes and inequalities (UDP, 2018[47]) and presented proposals for adapting the ongoing National Educational Reform to reflect the gender perspective (MINEDUC, 2015[48]). The resulting 2019 pre-school curriculum increased the representation of female writers or authors (Ministerio del Interior y de la Seguridad Publica, 2018[49]). With support of the National Women’s Service (SERNAM), the Ministry of Education (MINEDUC) developed a manual of guidelines to prevent gender biases in textbooks for distribution among publishers. The creation of training sessions facilitated the dissemination of the guidelines.

Recent assessments of the progress achieved provided an opportunity to take stock of the progress achieved. It revealed a number of areas where difficulties persist, particularly there remains scope for more concrete actions to integrate the gender perspective into the secondary curriculum (UDP, 2018[47]). In 2018, the Ministry of Education created a commission of experts with the task to identify gender biases in the curricula across levels of education, from preschool to high school. Although the findings have not been published, the commission has made several immediate and long-term recommendations to the government (MINEDUC, 2019[50]). These recommendations include expanding the gender-sensitive perspective to secondary education.

Policy insights

Introduce trainings to help teachers becoming more mindful about the importance of gender attitudes and stereotypes at school. One lesson from the international experience is that the efforts to create a culture conducive to gender equality should start from early education and with the willing support of the teachers (OECD, 2012[33]). Specific training is important to help the teachers adapting their pedagogical approaches to the age group of the children (UNESCO, 2017[51]). For example, teachers have played a pivotal role in the initiatives undertaken by the government of the Flanders (Belgium) to raise awareness about gender roles in Flemish schools. Teachers received trainings to detect the presence of gender attitudes and stereotypes in the curriculum material and were encouraged to propose solutions on how to improve the situation. There is evidence of teachers having subsequently become more mindful of the importance to avert the use of a spoken language with the children that could favour the development of stereotyped gender roles. Assignments that could reinforce the development of identity aspects (girls to carry out organisational and support roles such as taking notes, planning events, co-ordinating group work, and so on) have gradually diminished. These outcomes were helped by changing the organisation of the classrooms and making recourse to mixed groups to limit splitting boys and girls (Council of Europe, 2014[52]). The lessons from this experience provide a potentially useful benchmark against which to assess the pedagogical guides issued by the Chilean Government and progress with implementation.

Engage the families in the process of creating gender-sensitive education. Although the main responsibility rely on schools when educating future citizens, involving parents is key when introducing a new educational approach aimed at strengthening gender-sensitive education. The family often acts as “spokesperson” of entrenched prejudices and parents could view the new initiatives to change course with suspicion. One positive feature of the pedagogical guidance implemented by the Chilean Government lies in the fact that it invites teachers to take a more pro-active role by exploring options for co-operative forms of engagement with Parents’ Associations. Upfront engagement to raise the consciousness of parents could spill over to households, smoothing the transmission of traditional gender roles within the larger family. The Chilean pedagogical guides include a video for parents to watch ahead of discussion meetings as a tool to prepare their thoughts.

As one example of international practices to engage parents, in Peru the Ministry of Education launched a national campaign in 2019 to inform parents about the importance of mainstreaming gender-sensitive practices in education and their interactions with the curriculum. Almost 140 information centres opened to explain families how and why the gender approach is implemented in the education curriculum (MINEDUC, 2019[53]). In Ireland, as part of the gender mainstreaming strategy, the Ministry of Education and Science developed guidelines, which address the whole school community, including parents. The guidelines for primary and secondary schools provide parents with information about school obligations in relation to equality legislation, explanation of gender mainstreaming and what it entails and suggestions for actions that parents can undertake at schools (Council of Europe, 2011[54]; EIGE, 2020[55]).

Keeping the momentum for change is essential, given that fighting gender stereotypes through the education system is a long-term process. Enhancing gender equality in education is a long-term process that requires capitalising on present and previous efforts to promote improvements. By implication, continuous monitoring of achievements can be of great value to put Chile on a sustainable path of progress. As part of a defined long-term strategy, Chile could identify a clear set of intermediate targets and standards, against which to organise an independent monitoring body in charge of assessing progress and disseminating success stories at school.

A range of institutional, legal and cultural constraints lies in the way of reducing the barriers to achieving a more equitable sharing of unpaid work activities in Chile. The OECD suggests:

Create a more comprehensive care system

Expand formal early childhood education and after-school care. The current bill aims at the creation of a more universalised early childhood care system by abolishing the size threshold according to which employers with more than 20 female workers must provide childcare assistance to children under the age of two.

Invest in long-term care. As an immediate objective, this could require expanding the Chile Cuida programme, both geographically and across income groups. Easing access to information on services available in the local area can be a way to point families towards resources that could help them.

Expand parental leave and flexible work options

Establish reserved paternity leave weeks as part of the parental leave. Although Chile already has parental leave that either men or women can use, few fathers actually take the leave. Many European countries have had success with boosting their take-up through reserving a certain share of the parental leave for fathers, meaning that the total leave that a couple can use is longer if both take it.

Support the policies to increase the coverage of maternity and paternity benefits by stepping up the momentum of the broader policies to strengthen formalisation. Currently, many new parents in Chile are not entitled to paid parental leave because they work without a formal contract and lack social insurance coverage. This situation underscores that the enforcement of parental leave arrangements would hardly generate sizeable results in terms of coverage if conducted in isolation from the broader policies to strengthen formalisation in Chile.

Strengthen flexible work options. Depending on the type of job, flexible starting times and teleworking can reduce the time crunch experienced by parents, reflecting long working hours, commutes and family obligations. The recent teleworking laws has positive features that the government could strengthen even further, for example, by financially supporting firms willing to invest in their ICT infrastructure and digital skills training in rural areas

Reduce the transmission of gender stereotypes through the education system

Introduce training to help teachers becoming more mindful about gender attitudes and stereotypes at school. One lesson from the international experience is that the efforts to create a culture conducive to gender equality should start from early education and with the willing support of the teachers. Specific training is important to help teachers adapting their pedagogical approaches to the age group of the children.

Engage the families in the process of creating gender-sensitive education. One positive feature of the pedagogical guidance implemented by the Chilean Government lies in the fact that it invites teachers to take a more pro-active role by exploring options for co-operative forms of engagement with the Parents’ Associations. Upfront engagement to raise the consciousness of parents could spill over to the households, smoothing the transmission of traditional gender roles within the larger family.

Keep the momentum for change by identifying clear intermediate targets and standards. An independent monitoring body could be in charge of assessing progress and disseminating success stories among schools.

Ensuring access to quality education for all

As discussed in the review of the evidence section, different factors explain the particularly high risk being faced by young women in Chile to be NEETs, nearly twice more pronounced than observed among young men (see Figure 1.12, Chapter 1). For example, women often have no other choice but to drop out of school in case of teenage pregnancy or to renounce participating in the labour market altogether following childbirth in young adulthood.

The Chilean Ministry of Education has a number of policies to address drop-outs from school, including due to premature motherhood. The public and private schools that do not comply with the statutory recognised right of pregnant students and mothers to remain in school (recognised since 2009) are subject to a fine (MINEDUC, 2018[56]). The Ministry of Education’s protocol for the retention of students in the school system exempts pregnant students, as well as teenage mothers and fathers, from the standard requirement of 85% minimum attendance. It also sets out guidelines for facilitating the establishment of support networks involving parents and guardians. Furthermore, it mandates the school to respect the breastfeeding schedule of mothers (MINEDUC, 2019[57]). The Ministry of Education monitors the outcomes of these policies using a School Retention indicator (MINEDUC, 2016[58]), which allows tracking the capacity of the schools to identify and support students at risk of dropping out early. Evidence of an increase in the number of student drop-outs during the COVID-19 pandemic, has accelerated the introduction of a new pilot scheme to provide special support for students at a particular risk of dropping out of the school system, using scholarships, ensuring pedagogical and psychological support, and communicating the benefits of completing studies. As part of this, in nine regions of the country interdisciplinary teams of social and psychological pedagogues work with youth particularly exposed to socio-educational risks. A joint programme between the Ministry of Social Development and the Ministry of Education through the government agency Junaeb (Junta Nacional de Auxilio Escolar y Becas – National Board of School Aid and Scholarships) has similar objectives.

Preventive educational programmes have a key role to play in lowering the exposure of teenage girls to the risk of becoming pregnant. One welcome feature of the programmes implemented by Chile lies in the fact that they reach out to both boys and girls. In addition, the delivery of the services extends beyond the premises of the schools as a way of broadening coverage. One example is the programme Espacios Amigables, which the Ministry of Health co-ordinates with the support of the network of local Family Health Centers (CESFAM). The programme involves the provision of various assistance services to adolescents from 10 to 19 years old, ranging from health care, safe nutrition and sexual education, particularly targeting youth who are less likely to use other health facilities due to various barriers (scheduling, long waiting times, confidentiality, and so on). In a friendly care space, set with youthful taste, adolescents can meet trained staff in privacy. A friendly approach in an adapted space is important to make girls and boys feel that they can safely and comfortably raise questions, clarify doubts and address concerns. Additionally, workshops on sexual reproductive health and mental health are held in schools and community spaces, at convenient times that do not overlap with school hours. Moreover, the Programa Salud Integral Adolescentes y Jóvenes is a comprehensive programme that aims at improving access to, and offer of health care services by, adolescents and young people up to the age of 24 years. It has a gender sensitive focus, in the field of prevention, treatment and rehabilitation, involving families and the community.

Policy insights

Provide additional support to vulnerable girls and teenage mothers. Chile has made progress towards ensuring that teenage mothers stay in education and raising the impact of the policies to reduce underage/young pregnancies. Initiatives, such as the programme Espacios Amigables and the Plan de Salud Integral de Adolescencia, have helped in this direction by integrating prevention and education policies more closely. This is essential to combat teen pregnancies and to limit, in turn, school drop-outs.

In perspective, there could be scope for providing additional financial support to mothers and their young children as a way of ensuring that they acquire basic education and skills that they can use at work. For example, a programme in Uruguay aims at promoting educational projects for mothers under the age of 23 by providing financial support for the care of their children while on education and training. In Australia, the government offers a variety of transfer programmes to teenage parents, such as the JET Child Care Fee Assistance subsidy, for example, which allows mothers to pay for formal childcare during the completion of their studying curriculum and the transition to work. The amount, paid directly to childcare providers, is commensurate to the income of the household, the child’s age and the hours of recognised activities by the mother and her partner.

The findings of recent analysis for Colombia by Cortés, Gallego and Maldonado (2016) provide some useful guidance for programme design in that they suggest that, in order for Conditional Cash Transfer programmes to support the reduction of fertility rates among adolescents, they should be “conditional enough”. This requires the use of well-stated and enforceable pre-defined criteria to track school success and attendance. In Chile, the protocol for the retention of students in the school system rightly exempts pregnant students, as well as teenage mothers and fathers, from the standard requirement of 85% minimum attendance. Nevertheless, the findings of this study suggest that the observance of some form of conditionality might be advisable to qualify for the transfers. For example, the government could require that students complete the school year and enrol in the following grade in order to continue benefitting from the assistance and/or that the subsidy cannot be recuperated after too long an interruption of the programme.

Ensure comprehensive sexual education and information at school. Even though the right to sexual information and education in secondary schools in Chile has been guaranteed by law since 2010 (Ley 20.480), actual implementation is left to the discretion of each institutions, which can vary depending upon local convictions and beliefs. In addition, there is no minimum curriculum requirement and when taught, sexual education often focusses on biological differences, without preventive reproductive information. Since many parents do not communicate with their children about this topic, most teenagers inform themselves from the internet, often leading to misinformation and distorted views, which could affect emotional development (Obrach King, Alexandra et al., 2017[59]). A better way to support the sexual information of students is by guaranteeing a minimum curriculum on sexual and preventive education in every school and monitoring its implementation (UNESCO, 2018[60]). Moreover, a special advisor on health and sexual education inside schools could equip students with appropriate information. It is preferable that the advisor be a trained young person, with whom the students can more easily identify as a peer, rather than a regular teacher with whom they are likely to feel uncomfortable.

Reward and communicate the benefits of completing studies. Free education is a necessary pre-condition to decrease the cost of sending children to school, especially for poor families. However, free access to education may not be sufficient since the subjective perception of the benefits of school enrolment varies across households. To account for this, conditional cash transfers (CCTs) could provide regular transfer benefits to parents of poor backgrounds who choose to keep their children at school. Meta-analysis of 94 studies from 47 CCTs programmes shows that school drop-outs tend to diminish when the benefits are contingent upon school enrolments and attendances. Qualifying for the benefits is typically associated with an 80-90% attendance obligation. The benefits also reduce the exposure of children to child labour.

Many girls and women lack the motivation to complete their education curriculum because they lack the support to develop a clear professional project. This consideration applies even more strongly to girls who are in secondary education but are already aware that their performance levels in the national test score will unlikely be high enough to qualify them to enroll in public tertiary education. School mentoring, student counselling and targeted scholarships are a key to helping girls and young women to remain and continue in education. One example of good practice is the Girls’ Network Mentoring Programme introduced by the United Kingdom. The aim of this initiative is to connect young girls between 14 and 19 years old and from disadvantaged schools with women from a range of established business activities. This mentoring allows girls to acquire information and building networks that would otherwise be impossible for them to access by relying solely on their own school and circle of family and friends. More than 500 mentors give practical advice and help girls with guidance about careers and university applications. Mentors receive a special training programme and, once girls complete their year-long mentoring journey, they graduate to become lifelong ambassadors of the programme.

Promoting women in non-traditional careers and leadership positions

The extent to which the election of a female President over two Presidential terms – President Michelle Bachelet, 2006-10 and subsequently 2014-18 – has contributed to changing the template of male-dominated politics in Chile is difficult to assess precisely. However, it is certain that a female leadership has represented a symbol of cultural change, which has fuelled a new momentum for greater equality and participation in all areas of public life (Albornoz Pollmann, 2017[61]). A quota law entered into force in 2017, as part of a broader electoral reform, with political parties being required to field no fewer than 40% of female candidates.

Importantly, the results of the Constitutional referendum in October 2020 set Chile to become the first country in the world to have as many female as male participants in its Constitutional Convention (Senado, 2019[62]; GOB, 2020[63]). International experience shows that although the participation of women in similar constitutional reforms has increased overtime, it still falls far short from parity with men. For example, in the 75 countries that engaged in constitutional reforms between 1990 and 2015 (including transitions from authoritarianism to democracy), only 19% of the members of the constitutional bodies were women (IPI, 2015[64]). The level of participation and inclusion in a constitution-making process can affect legitimacy, as well as, prospectively, the degree to which women will be able to represent their specific interests in the future (Philipps, 1998[65]; IDEA, 2019[66]; Hart, 2003[67]).

The above patterns have spilled over to the policies that influence the access of women to leadership and management positions in the business sector and could potentially set the tone for more future improvements. Following the introduction of a 40% target of women on the boards of state-owned enterprises – first set during President Bachelet’s two Presidencies and further enforced during the two Presidencies of President Pinera –, the actual percentage reached 42.1% in 2018 (Comunidad Mujer, 2018[68]). However, even though this achievement should have encouraged the private companies to emulate the experience of the state-owned enterprises, there is evidence that the record of accomplishments is still modest across the private sector. For the 40 largest companies rated in the stock market, the share of women on boards was a meagre 6.2% in 2018 (Comunidad Mujer, 2018[68]). A recent requirement by the Superintendencia de Valores y Seguros (SVS, Superintendence of Securities and Insurance) seeks to generate more information on the progress made by the private sector towards the standards of the public sector. In particular, “rule 385” provides on the adoption of social responsibility and sustainable development policies, referring in particular to the diversity in the composition of the board of directors and in the appointment of the company’s main executives (Sistema de Empresas, 2016[69]).

There are indications suggesting that the policy dialogue can foster the participation of women at all levels of governance in the private sector. A glance at the transport and mining sectors, which in addition to being economically important in Chile have a strong male-dominated tradition, seems to corroborate this view. The pay-off of gender-equity policies have been relatively significant in transport, likelihood reflecting the fact that the Ministry of Transport and Telecommunications and the sector associations decided to implement an ambitious gender equality strategy following a concerted implementation approach. In stark contrast, the participation of women in the governance remains relatively low in mining companies, which possibly reflects a less dialogue-centred approach, notwithstanding the abolition of the law that forbade women from working in the sector dates back to 1996.

In Chile, many women who opt for scientific careers struggle to combine the fulfilment of a lengthy and demanding academic curriculum with family responsibilities. Doctoral students and post-docs, for example, generally lack the rights to maternity benefits and pre- and post-natal care. In addition, the concentration of research activities in a few urban centres and the ‘excellence’ criteria for scholarships imply that it is difficult for more disadvantaged students to gain access to prestigious university programmes. Although these difficulties are common to both genders, for girls they appear compounded by higher care obligations and the impact of stereotypes.

The Chilean Government, the universities and research institutions have introduced a series of initiatives to increase the attractiveness of STEM careers to women. The year 2019 saw the launch of the campaign Mas Mujeres en Ciencias (More Women in Sciences) jointly organised by the Ministry of Women and Gender Equity and the Ministry of Sciences, Technology, Knowledge and Innovation. This initiative seeks to encourage female presence in historically masculinised professional careers. The Institutional Policy on Gender, issued by the National Commission on Scientific and Technological Research’s (CONICYT) and covering the eight year period between 2017 and 2025, aims to expand maternity leave rights for junior researchers and to improve the representation of female scientists in decision-making positions, for instance as heads of research groups (CONICYT, 2017[70]). Since 2020, the Ministry of Science includes a special Council for Gender Equity, delegated to elaborate action plans for gender equality in STEM. In 2013, the Faculty of Mathematical and Physical Sciences at the University of Chile created a gender equality admissions programme, which has led to increase the share of admitted women into its competitive engineering and science programme from 19% to 32%.

Policy insights

Strengthen women’s representation at the executive level in private sector companies. The system of a gender quota and targets has shown positive results in Chile’s congress and state-owned enterprises. However, the enforcement of similar quotas or voluntary targets on boards and in senior management positions remains difficult among private sector companies (OECD, 2019[71]). International practice shows that one way of supporting and accelerating the inclusion of women in leadership positions and eliminating wage gaps is by requiring companies to disclose statistics on the gender composition at different management levels. Further to encouraging the dissemination of good practices, disclosure can result in “name and shame” effects, by allowing singling out non-compliant companies. In Germany, the 2015 Act on equal participation of women and men in executive positions in private and public sectors set a 30% gender diversity quota for supervisory boards and required listed and co-determined companies (where workers can vote for representatives on the board) to establish targets for gender equality at the top two levels of management. Israeli state-owned enterprises have a legal target of appropriate representation for both genders on the board of directors – usually 50%, unless there is a sound reason why such representation is unachievable. Until reaching the goal, priority is for directors of the under-represented gender with a possibility to fine non-complying companies.

Step up monitoring and evaluation mechanisms. Specific and measurable objectives are a key to evaluate whether goals for women’s representation in different professions and at the leadership level are met. For example, strong internal monitoring mechanisms could support the goal of an equal pay for an equivalent work. In Australia, the Workplace Gender Equality Act requires non-public sector employers with 100 or more employees to disclose their “Gender Equality Indicators” in annual filings submitted to the Workplace Gender Equality Agency.

Raise girls’ interest in science, technology and mathematics. Students should become aware of STEM before moving to post-secondary education to be able to make informed decisions about future careers. Mentorship programmes can allow them to identify positive role models, including by drawing inspiration from high-level positions in public and private companies. By shaping girls’ career goals and enhancing perceptions that those goals are on reach, the impact of positive examples can be significant. In addition, mentorship programmes increase self-confidence, boost communication skills, and enhance leadership qualities more durably, which will benefit girls during their careers. In 2017 the OECD and the Mexican Government created the “NinaSTEMPueden” initiative for the promotion of conferences, workshops and mentorship programmes to enhance the attractiveness of STEM curricula to Mexican girls (OECD, 2020[72]).

Aside from mentorship, school textbooks could disseminate examples of male and female scientists, while introducing experimental and interactive science experiences at school could also help to increase girls’ interest in STEM. The University of Costa Rica, for example, has organised several science workshops for 7-13 year-old girls in 2019. Public awareness campaigns can support the general fight against traditional gender stereotypes by showing that excelling in STEM areas is compatible with family life. These campaigns should start at the earliest stage of education, including with the support of social media platforms. TV programmes and series promoting women role models in STEM could be a source of inspiration for young girls.

Recognise and reinforce the application of statutory maternity and paternity leave in the academic sector and support access to care services. Expanding these rights, as proposed by the roadmap for fostering the representation of women in science as set out by the Ministry of Science, can foster the attractiveness of academic careers to female science graduates. Mothers who return to work after their maternity leave should have the option to increase their working hours gradually.

Supporting female entrepreneurship

As discussed in the review of the evidence section, women in Chile are less likely to be entrepreneurs than men. While the proportion of men and women who are own-account workers is virtually the same, the share of those who are employers is about twice as large among men than women. Moreover, women entrepreneurs are much less likely to own or manage medium and large firms. Furthermore, recent analyses of the traits for starting a business suggest that women more likely than men become entrepreneur because they cannot find good employment alternatives. By contrast, men are more likely do so because they have identified a good business opportunity.

Women face higher barriers to entrepreneurship than men do in Chile. As discussed above, one important barrier stems as a side effect of a very restrictive marital law, which implies that is difficult for married women to start or close a business without the consent of their husbands (OECD, 2020[73]). Without consent, the woman cannot access the collateral, which undermines creditworthiness. Accordingly, a woman entrepreneur faces a higher risk of being subject to an interest rate penalty when launching a new business.

It is unfortunate that marital law stands in the way of women gaining access to financing, because it means that women have more difficulty to access existing support programmes (OEAP, 2018[74]) as per the short review below:

Launched in November 2019, the Fondo Lévantate Mujer of the Women’s Promotion and Development Foundation (PRODEMU) supports the entrepreneurship of more than 600 women through providing 250 000 Chilean pesos (approximately EUR 290) as a “seed financing” to enable the launch of new businesses.

The programme Mujer Emprende of the Ministry of Women, launched in 2015, targets female entrepreneurs whose businesses have existed for at least one year. Through the Escuela Mujer Emprende, the programme seeks to strengthen the business skills of these entrepreneurs. There are three different levels of training, depending on how developed the business is. It also seeks to strengthen the networks of female entrepreneurs. Around 1 000 women have participated in the programme to date.

The programme Yo Emprendo Semilla (previously Programa de Apoyo al Microemprendimiento), run by the Ministry of Social Development, is open to individuals from vulnerable households who have a potentially promising business idea. The programme provides around USD 600 in start-up capital, 60 hours of training and follow-up mentoring visits. An evaluation of the programme found that participation boosted employment, business practices and labour income in the short- and long-term. Compared to the control group, including individuals who did not receive the subsidy, the probability of still being self-employed 45 months later was higher among those who received a larger subsidy, although individuals who qualified for a smaller subsidy were more likely to be in wage employment (Martínez A., Puentes and Ruiz-Tagle, 2018[75]).

The Ministry of the Economy offers a technical co-operation service for small (SERCOTEC) and larger companies (CORFO). For example, it provides training, subsidies, and advice on accessing foreign markets. The SERCOTEC and CORFO programmes are open to men and women alike, but the subsidies of CORFO are 10% higher for women.

In addition to the impact of the marital law, the barriers to entrepreneurship include fewer opportunities for training and for accessing financial resources. Business networks are typically smaller and less effective for many women, particularly from low-income households. The lack of training opportunities, the difficulties to participate in networking events and to access financing sources, compound the impact of overburdening domestic responsibilities, travelling difficulties and the lack of information about available options. This context propels the fear of failure and a lack of trust in entrepreneurial skills (OECD/EU, 2017[76]).

Policy insights

Policies to promote gender-neutral education and awareness of role models can play an important role to change society’s perceptions about women’s abilities as entrepreneurs. In addition to these pre-requirements, there is room for strengthening women’s entrepreneurship even further in Chile by tackling the marital law, encouraging women to seek more external financing, and strengthening training programmes, including the mentoring and business development components of such programmes.

Step up the reform of the marital law by revamping the reform proposal that has been under discussion in Congress for the past eight years. As a minimum requirement, this would involve the abolition of the default rule, which foresees that the husband administers the marital property. The priority given to the most restrictive and disadvantageous option to women means that women have to pay a higher interest rate when applying for credit to launch a new business.

Encourage take-up of financing. Female entrepreneurs are less likely to seek funding to grow their business. A survey among entrepreneurs in Pacific Alliance countries found that male entrepreneurs are more likely to use each of the methods of financing mentioned by the questionnaire, including personal savings as the principal source, followed by friends and family; the financial system; public funds; business angels; investment funds and crowdfunding. Perhaps related to the impact of marital law, among Chilean micro-entrepreneurs, women seem less likely than men to seek a credit (Arellano and Peralta, 2016[77]), However, those who seek one seem to perceive public subsidies and access to private financing to be sufficient (OEAP, 2018[78]). It is unclear whether the same is true for entrepreneurs running small and medium enterprises.

The government should seek to maintain its good record of awarding funding to male and female entrepreneurs alike. It could also consider undertaking an in-depth study of the likelihood that male and female entrepreneurs obtain a funding tailored to their needs, taking into account their different personal and business characteristics. Finally, entrepreneurship-training courses for women could place more emphasis on when it makes sense to seek credit or other private or public-sector funding and how to go about obtaining it.

Enhance training programmes through long-term mentoring and business incubators. A review of existing programmes to support entrepreneurship in low- and middle-income countries confirms that training can play a powerful role in strengthening individuals’ business competences with positive feedback effects on job creation. However, to be successful they have to meet certain requirements, such as targeting early entrepreneurs, being intensive and offered in combination with financial support (Grimm and Paffhausen, 2015[79]). Networking and mentoring guidance – via the creation of women’s associations and forums, for example – are important catalysts of market information and can greatly facilitate knowledge sharing among peers.

These pre-conditions already apply to several of the Chilean programmes. Experience from European countries suggests that mentorship between experienced and new entrepreneurs can enhance business skills as well, if the mentor and mentee match well. Using interviews to figure out which mentor to match to which mentee is hence worthwhile. In addition, business accelerators or incubators can also provide opportunities for further training and networking in combination with business, financial and legal advice (OECD/EU, 2017[76]). Such accelerators could be run by the public sector itself or operated by the private or non-profit sector, with potential public funding (OECD/EU, 2019[80]).

Strengthening gender-sensitive approaches is essential to reach out to low income women. Work by the OECD shows that the adoption of gender-sensitive approaches in the design of training programmes is key to broadening access, thus expanding the pool of potentially interested women. Particularly, reaching out to women from low-income households requires the design of programmes that pay attention to certain day-to-day needs, such as women’s time schedules, for example, and the need for assistance at home. This is important to secure continuity of care responsibilities, of the children and the elderly, during the time spent in training (OECD, 2019[81]).

Fighting violence against women

Mounting intolerance of violence against women during the past years has brought the fight against gender-based violence to the fore of the demand for increased social justice in Chile. This development is part of a pattern common to other Latin American countries. One prominent example is the action entailed by the #Niunamenos collective, which launched an awareness campaign, focusing on violence against women and the victims of femicide following the murder of a young Argentine woman. Mobilisations throughout the region, which has the highest rate of femicides in the world, increased after this campaign. Prompted by domestic developments and further spurred by regional movements, the Chilean authorities have taken initiatives to strengthen the laws against sexual harassment and gender-based violence (Red Chilena Contra las Violencias Hacia las Mujeres, 2020[82]). Law 20, 066, approved in 2010 defined femicide for the first time. It follows from the 1994 Law on Domestic Violence, which did not acknowledge that this crime has a strong gender component, despite the fact that over 80% of those attacked are women and over 80% of the aggressors are men. In 2020, the Gabriela Law (Law 21 212) expanded the definition of femicides to include attackers beyond current or former partners. In addition, the Ministry of Women and Gender Equality has promoted the launch of several awareness campaigns and broadcast through social networks and television channels, such as in 2018 the “Do not let it pass: Campaign against gender violence in Chile”. The next section of this report provides a discussion of how the fight against gender-based violence has intensified during the COVID-19 crisis, including with the support of digital applications.

In addition to the laws against domestic violence, the Chilean legal system involves laws and regulations to combat harassment and violence against women in the public sphere. The 2012 Law No. 20 607 introduced sanctions against workplace harassment into the Chilean labor code. Schools and universities, in contrast, only have voluntary internal protocols for actions against school abuse, although cases can be reported to the Superintendence of Education if an institution does not take action. After almost two years of debate, the street sexual harassment law was unanimously approved in 2019. The penalties can range from 61 days to 5 years in prison with fines from USD 60 to USD 100 000.

Policy insights

Lower the barriers that prevent the victims of violence and harassment to access the justice system. Victims of violence against women often hesitate to report the crime for fear of high risks re-victimisation amid lengthy procedural requirements. Recent analysis of the issue suggests that on average, the processing time for sexual crimes in oral trials requires 947 days and fewer than 8% end with a conviction (Fiscalia de Chile, 2019[83]). Moreover, the Criminal Code defines rape and sexual abuse, narrowly implying that many practices considered as sexual violence are not recognised as crimes (OCAC, 2020[84]). Providing training to police and justice officers on how to address violence against women, including best practices on how to interact with the victims, can make the process of reporting these crimes less difficult. For example, in 2019, Mexico launched a police-training Programme that aims to ensure the correct application of procedural protocols in situations of gender violence. Hardly any victim can meet the current six-month deadline for reporting harassment or sexual violence, in particular against minors. Acknowledging the fact that the decision to report can be longer, a time extension seems desirable.

Encourage and guarantee safe complaint processes for victims. At workplaces, in schools and universities, women may be even more reluctant to report harassment or violence if the perpetrators are in a superior hierarchical position, such as teachers, supervisors or managers (ILO, 2018[85]). Accordingly, the Chilean Government could consider devoting more efforts to implementing safe complaint mechanisms to facilitate the reporting of these situations at the work place. International experience on the matter suggests that the policy initiatives to encourage companies to adopt complaint mechanisms can rely on different tools, such as collective agreements, for example, the regulations on Occupational Health and Safety and the employment legislation (Eurofound, 2015[86]). In the Scandinavian countries and the Netherlands, for example, the employers’ obligation to set out procedures or measures to tackle violence and harassment in the workplace is a part of the approach to safeguard employees’ mental and physical health. As such, it pertains to the regulations for improving well-being and health issues at work. Legislation in Belgium and France has introduced a specific duty on the employer to prevent violence and harassment. Ireland advices the employers to introduce a code of conduct in order to show their commitment to tackling abusive behaviour, which is highly relevant in case of a court claim.

The regulatory framework can also focus on prevention, setting out principles and guidelines to enable the employers adopting more pro-active initiatives. In compliance with these guidelines, some private employers have workshops and trainings in place to explain the law against sexual abuse at work and to raise awareness about the different manifestations of sexual abuse at work, along with how to report them. The role of social partners can also be important to scale up preventive actions at workplace level drawing from their expertise, including by helping the design of individual support, such as the presence of confidential counsellors.

Educate the youth about different aspects of sexual violence and harassment. Although Chile has launched awareness campaigns for sexual violence, these campaigns do not target teenagers, despite the fact that young women are often victims. One international example is the campaign #IlikeHowYouAre launched by Spain in 2019 to prevent gender violence among young people and targeting teenage girls and boys. Through the promotion of respect, acceptance and autonomy in the couple, the campaign focuses on the main manifestations of gender violence, with the aim of identifying and preventing them. A completely digitally supported campaign, it is disseminated through social networks. Other campaigns target street sexual harassment. In Argentina, the campaign #Cambiáeltrato, which showed a young man explaining to another that his behaviour with women on the street was not appropriate, went viral.

Monitor transport security. The lack of secure transports can lead women to restrict their movements as a way of reducing the exposure to risky behaviours. Such resolutions can discourage, in turn, women from participating in labour markets, with the adverse effects on incomes being potentially important for households in remote areas. In Chile, the 2018-22 Agenda for a Gender Equity Policy in Transport of the Ministry of Transport and Telecommunication defines goals to analyse the transport needs of women and to increase the security in public transport. While statistics on access to and security of transport and commuting characteristics for men and women exist for Santiago, similar information do not exist for rural areas, which limits the capacity to assess the effectiveness of policies (Duchène, 2011[87]).

A range of concomitant policies can reduce the gender gap in labour income, thus contributing to lessening the incentive for women to spend more hours on unpaid work by. The OECD suggests to:

Ensure access to quality education for all

Provide additional support to vulnerable girls and teenage mothers. Chile has made progress towards ensuring that teenage mothers stay in education and raising the impact of the policies to reduce premature pregnancies. In perspective, there could be scope for providing additional financial support to mothers and their young children as a way of ensuring that they can acquire basic education and skills that they can use at work.

Ensure comprehensive sexual education and information at school. This requires guaranteeing a minimum curriculum on sexual and preventive education in every school and monitoring its implementation. A special advisor on health and sexual education inside schools could support students with appropriate information. It is advisable that the advisor be a trained young person, who the students can more easily identify as a peer, rather than a regular teacher.

Reward and communicate the benefits of completing studies. Conditional cash transfers (CCTs) could provide a regular transfer benefits to parents of poor background who choose to keep their children at school. School mentoring, student counselling and targeted scholarships can be a key to helping girls and young women staying in education, if the mentors receive adapted training.

Promote women in non-traditional careers and leadership positions

Strengthen women’s representation at the executive level in private sector companies. The gender quota system has shown positive results in Chile’s congress and state owned enterprises. However, the enforcement of a similar system or voluntary targets on boards and in senior management positions remains difficult among private sector companies.

Step up monitoring and evaluation mechanisms with the aim to support the goal of equal pay for equivalent work. In Australia, the Workplace Gender Equality Act requires non-public sector employers with 100 or more employees to disclose their “Gender Equality Indicators” in annual filings submitted to the Workplace Gender Equality Agency.

Step up efforts to raise girls’ interest in science, technology and mathematics. Students should become aware of STEM before moving to post-secondary education so as to be able to make informed decisions about future careers. Mentorship programmes can allow them to identify positive role models, including by drawing inspiration from high-level positions in public and private companies. School textbooks could disseminate examples of male and female scientists. Public awareness campaigns can support the general fight against traditional gender stereotypes by showing that excelling in STEM areas is compatible with family life.

Recognise and reinforce the application of statutory maternity and paternity leave in the academic sector and support access to care services. Expanding these rights, as proposed by a roadmap of the Ministry of Science for fostering the representation of women in science, can foster the attractiveness of academic careers to female science graduates. Mothers who return to work after their maternity leave should have the option to increase their working hours gradually.

Support female entrepreneurship

Step up the reform of the marital law by revamping the proposal that has been under discussion in Congress for the past eight years. As a minimum requirement, this would necessitate the abolition of the default rule, which foresees that the husband administers the marital property.