3. Fighting illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing

Illegal, unreported and unregulated (IUU) fishing is a serious threat to fisheries and fisheries-dependent communities that impairs the development of a sustainable ocean economy. Eradicating IUU fishing requires closing waters and markets to IUU operators and the products they harvest globally. Based on a survey conducted in 2019, this chapter reviews the policies that countries and economies apply in the fight against IUU fishing and evaluates the extent to which internationally-recognised best practices in some of the most important areas for government intervention against IUU fishing have been adopted. It identifies the regulatory loopholes and policy gaps that need to be addressed and provides information on effective measures that could be adapted and replicated across countries and economies.

To consolidate the benefits of the recent progress made in fighting IUU fishing through stricter regulation, closer monitoring and control and greater international co-operation, extra steps need to be taken to firmly close waters and markets to IUU operators and the products they harvest globally.

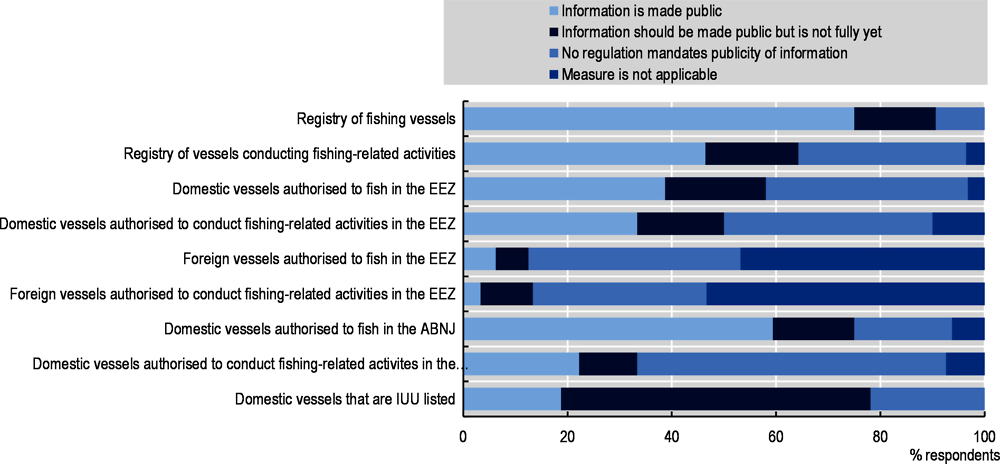

Registration and authorisation processes should be made fully transparent to facilitate co-operation between governments, across branches of government and between stakeholders so that they can join forces to better track IUU activities. G7 and G20 countries, which have expressed a shared ambition to curb IUU fishing following conferences in Charlevoix in 2018 and in Osaka in 2019, respectively, could lead the way by making public their vessel registries as well the lists of authorised vessels and those that have been identified as engaging in IUU fishing. Results of the survey conducted in this chapter show that only one in five responding countries and economies properly published lists of vessels identified as engaging in IUU fishing while over half of them did not publish the lists of vessels they authorised to conduct fishing-related activities in the high seas.

The issuing of a unique vessel identifier in the registration process should be adopted and harmonised, making use of International Maritime Organization (IMO) numbers whenever possible. A quarter of surveyed countries and economies reported they did not require an IMO number to register fishing vessels and a third did not require one to register vessels conducting fishing-related activities.

Transhipment (whereby fish are transferred from fishing boats onto larger refrigerated vessels, which then carry the fish to port while fishing vessels continue fishing) should be regulated more stringently and resources should be allocated to enforcement and monitoring. This is needed to ensure that products of IUU fishing do not enter the value chain unnoticed during transhipments. Evidence suggests that regulations of transhipment lag behind equivalent regulations of fishing. Better definitions and regulations of other fishing-related activities – such as the transfer of fuel, food and crew from “mother ships” to fishing vessels – would also improve control of fleets.

Best practices so as to gather information on who ultimately controls and benefits from vessel activities (i.e. the “beneficial owners” of vessels) should be identified and promoted. Indeed, many countries and economies have a legal framework to do so, but report practical difficulties.

Wider adoption of market measures should be encouraged internationally so as to increase the traceability in seafood value chains. This would also contribute to closing markets and access to support and services to operators that engage in IUU fishing. A third of the countries and economies surveyed for this chapter reported having issues in implementing their legal provisions to restrict support for operators convicted of IUU fishing (or not having any). Current negotiations on fisheries subsidies at the World Trade Organization (WTO) offer a unique opportunity to prohibit subsidies contributing to IUU fishing.

The effectiveness of country actions against IUU fishing should be measured so as to help fine-tune priorities and motivate on-going reforms.

A shared ambition to deter and eliminate IUU fishing

Illegal, unreported and unregulated (IUU) fishing is a serious threat to fisheries and fisheries-dependent communities, the ocean ecosystem, and society (Agnew et al., 2009[1]; Sumaila et al., 2020[2]; Konar et al., 2019[3]). The pressure on fish stocks resulting from IUU fishing harms law-abiding fishers by creating unfair competition, reducing their profitability and employment opportunities throughout the value chain. It can also affect revenues from other activities that depend on fish resources, such as tourism activities related to recreational fishing or marine wildlife watching. When replacing legal activities, IUU fishing also deprives countries of the associated fiscal revenues (Galaz et al., 2018[4]; Sumaila et al., 2020[2]).

IUU fishing weakens the capacity of governments to manage fisheries sustainably by adding fishing pressure that is difficult to quantify and account for when setting catch limits (Österblom, 2014[5]). It harms marine ecosystems and fish stocks when damaging fishing techniques are used and protected endangered species are targeted. By impacting the sustainability of resources and ecosystems, IUU fishing also risks worsening the implications of climate change on fish resources, most notably in the tropics (Gaines et al., 2018[6]; Gaines et al., 2019[7]; Pörtner et al., 2019[8]).

Ultimately, all the benefits to society associated with healthy and resilient fisheries are compromised by IUU fishing; including fisheries’ contribution to global food security today and in the future (Costello et al., 2020[9]). In countries and communities that depend on local seafood, IUU fishing threatens food security by diverting fish away from local markets, and putting food safety at risk when illegal seafood reaches consumers without having been handled, controlled and labelled correctly (Reilly, 2018[10]).1 IUU fishing vessels and operators are sometimes involved in transnational crimes, such as human rights abuses, drug or weapon smuggling, corruption and tax evasion (Witbooi et al., 2020[11]; UNODC, 2011[12]; Urbina, 2019[13]; Tickler et al., 2018[14]; Telesetsky, 2014[15]; Sumaila and Bawumia, 2014[16]).2 In some parts of the world, IUU fishing also exacerbates conflicts over scarce resources and disputed waters (Widjaja et al., 2019[17]; Spijkers et al., 2019[18]).

For these reasons, the fight against IUU fishing has become central to fisheries management and a key issue for international co-operation given its trans-boundary nature (High Seas Task Force, 2006[19]; Global Ocean Commission, 2014[20]). Evidence has shown that rapid, significant and lasting gains are at stake (Costello et al., 2020[9]; World Bank, 2017[21]) and the reforms needed to reap these gains are often more acceptable by fishing communities and the fish industry than are overall fishing restrictions (Cabral et al., 2018[22]).

The OECD report Closing gaps in national regulations against IUU fishing (Hutniczak, Delpeuch and Leroy, 2019[23]) showed that countries had made significant progress between 2005 and 2016 in adopting and implementing best practices against IUU fishing in line with international instruments developed by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). These instruments include the 2001 International Plan of Action to Prevent, Deter and Eliminate Illegal, Unreported and Unregulated Fishing (IPOA-IUU) (FAO, 2001[24]), the 2016 Agreement on Port State Measures (PSMA) (FAO, 2009[25]) and the 2017 Voluntary Guidelines for Catch Documentation Schemes (VGCDS) (FAO, 2017[26]).

The effectiveness of recent reforms in the fight against IUU fishing has been demonstrated at local and regional scales (Cabral et al., 2018[22]). Less is known about their combined impact on the incidence of IUU fishing at a global scale.3 Yet, as the 2020 deadline for achieving the Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 14 objective of ending IUU fishing approaches, IUU fishing continues to restrict the development of a sustainable ocean economy (Widjaja et al., 2019[17]).

Identifying where to focus reform

IUU fishing frequently occurs in areas where regulations and enforcement are weaker or absent; adapting to changes in regulation and surveillance technologies (OECD, 2005[27]). Reaping the benefits of the progress to date in the fight against IUU fishing will therefore depend on undertaking the necessary extra steps collectively to close waters and markets to IUU fishers and the products they harvest globally. This requires long-term efforts by the international community, backed by fishing communities, industry, and non-governmental organisations (NGOs), to push for concerted action, especially in domains that affect competition between countries. The negotiations at the World Trade Organization (WTO), which seek agreement on disciplines to prohibit subsidies that contribute to IUU fishing are of utmost importance in this regard. Regional Fisheries Management Organisations also have a key role to play as the primary mechanism for co-operation between fishing countries and coastal states to ensure sustainable fishing globally (Box 3.1).

Regional Fisheries Management Organisations (RFMOs) can take a number of measures to prevent illegal, unreported and unregulated (IUU) fishing in the areas or the fisheries they manage. These include: issuing of lists of vessels permitted to fish within the RFMO area as well as IUU vessel lists; promoting the adoption of catch and activity reporting systems as well as catch and trade documentation schemes; imposing trade embargoes on seafood products from non-compliant countries; mandating or undertaking on-board observer programmes as well as at-sea and in-port inspections; setting minimum standards for registration and authorisation procedures as well as port state controls; and establishing provisions to exclude or reduce the benefits of RFMO membership to flag states of vessels involved in illegal activities (OECD, 2005[27]). Hutniczak, Delpeuch and Leroy (2019[28]) show that recent conservation and management measures introduced by RFMOs mandate their members to adopt more comprehensive minimum standards for MCS and as well as more rigorous IUU vessel-listing mechanisms. Most RFMOs were found to review more regularly and with greater transparency the compliance with membership obligations, and to better co-operate and exchange information.

However, the report also noted there were important discrepancies in the implementation of best practices against IUU fishing remained across RFMOs, suggesting scope for improvement by learning from best performers. Furthermore, the report pointed to the need for improved governance of RFMOs so as to facilitate their decision-making processes (Chapter 5).

Impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic

Travel and other restrictions adopted in response to the COVID-19 pandemic have made in-person on-board observation, at-sea inspections and other forms of surveillance more challenging in multilateral fisheries. Consequently, in-person observation requirements were waived by several RFMOs, potentially increasing the opportunity for IUU fishing in some fisheries. There is a widespread expectation among RFMO secretariats that the reduced compliance monitoring will lead to increased IUU fishing, but currently the extent to which and where this is happening is unknown. The impacts of the pandemic on IUU fishing will depend on the type and the stringency of the observer requirements waived as well as on how fisheries are responding to the changes in prices and costs generated by this crisis. For example, the waiving of 100% observer coverage in Pacific purse seine tuna fisheries, a high-value industrial fisheries, could have significant impacts on IUU.

As the pandemic continues, finding pathways to restart international observer programmes and reinstate compliance monitoring to agreed-upon levels will become more urgent. Further, with in-person observation reduced, the role of countries in preventing IUU fishing through other means – e.g. by denying access to fish value chains and introducing market and port state measures – becomes increasingly important. In the longer term, increasing capacity for real-time monitoring and control of activities at sea and in ports (i.e. through accelerated uptake of remote sense technology) and harmonising data collection (i.e. through observer programmes and scientific research) between regions could make RFMO monitoring processes more timely and effective. As many authorities lack the capability to use remote sensing technologies to conduct MCS, the sharing of data relating to activities in the high seas between authorities with and without such capacity could benefit the monitoring of IUU.

Source: (OECD, 2020[29]; OECD, forthcoming[30]; Hutniczak, Delpeuch and Leroy, 2019[28])

The continuous evaluation of country regulations and policies against the frontier of best practices in the fight of IUU fishing is key to generalise their adoption. To win the battle against IUU fishing operators, authorities will need to regularly identify the regulatory loopholes and policy gaps that need to be addressed, share information on effective measures and technologies that can be adapted and replicated across countries, and co-operate to facilitate the transfer of technologies and capacity building (Widjaja et al., 2019[17]).4

This chapter aims to contribute to these goals by revisiting and updating the analysis undertaken by Hutniczak, Delpeuch and Leroy (2019[23]).5 Based on a survey conducted in 2019, and in light of the latest internationally-recognized best practices, it re-evaluates the progress made by countries and economies in some of the most important domains of government intervention against IUU fishing:

Vessel registration, by which countries collect and publicise information on vessels operating in their exclusive economic zone (EEZ) or flying their flag

Authorisation to operate in the EEZ, by which countries, as coastal states, regulate fishing and fishing-related operations in their EEZ

Authorisation to operate outside the EEZ, by which countries, as flag states, regulate the operations of vessels flying their flag in areas beyond national jurisdictions (ABNJ – that is, in the high seas) and in foreign EEZs

Port state measures, by which countries monitor and control access to and activities at port

Market measures, by which countries regulate how products enter the market and flow through the supply chain and economically discourage IUU fishing

International co-operation, by which countries engage in regional and global information sharing and joint activities against IUU fishing.

For each of these domains, information was sought through the survey on the legal and policy frameworks in place to deter, identify and punish IUU fishing, and the degree to which they were implemented in 2018 (Annex Table 3.A.1).6 A total of 33 countries and economies participated, including 26 OECD countries, as well as Argentina, the People’s Republic of China (hereafter “China”), Costa Rica, Indonesia, Chinese Taipei, Thailand and Viet Nam – together referred to as “emerging economies”.

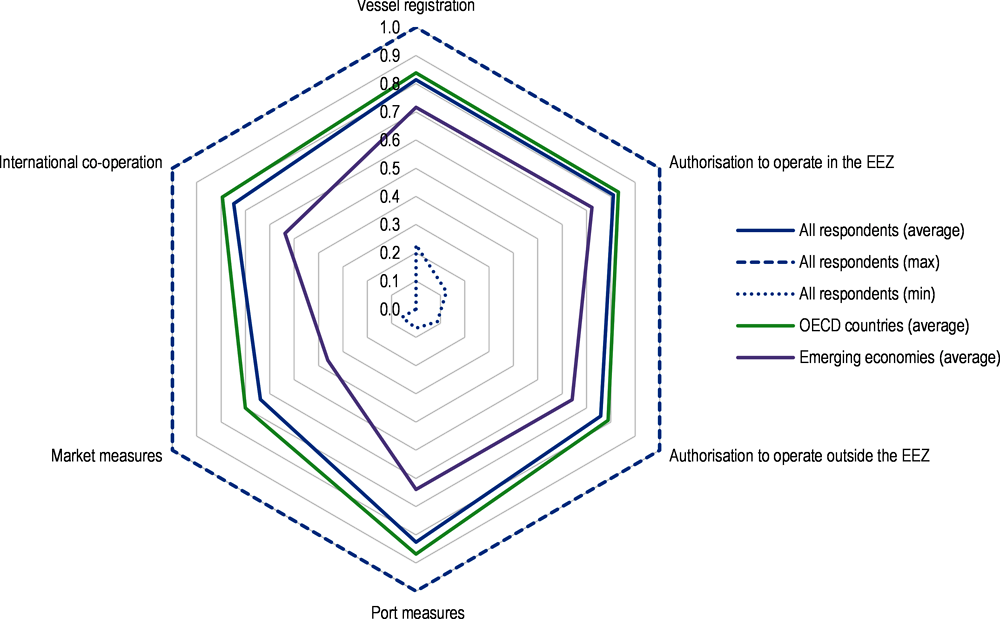

To identify patterns and trends in performance, answers were scored between 0 and 1, with increasing scores indicating higher levels of adoption and implementation of the regulation and measures at stake in each question. A score of 0 indicates no regulation was in place; 0.2 there was a regulation but it was reported as not implemented; 0.5 the regulation was reported to be partially implemented; and 1 refers to full implementation.7 Scores were then aggregated into six indicators at the level of the most important domains of government intervention against IUU fishing and indicators were averaged over all respondents – or OECD countries and emerging economies (Figure 3.1).8 As the survey included a series of questions which had already been submitted to countries and economies participating in the work of the OECD Fisheries Committee (COFI) in 2006 (with reference to their situation in 2005) and in 2017 (with reference to their situation in 2016), evidence of progress is also presented in relation to issues for which comparative data existed.9

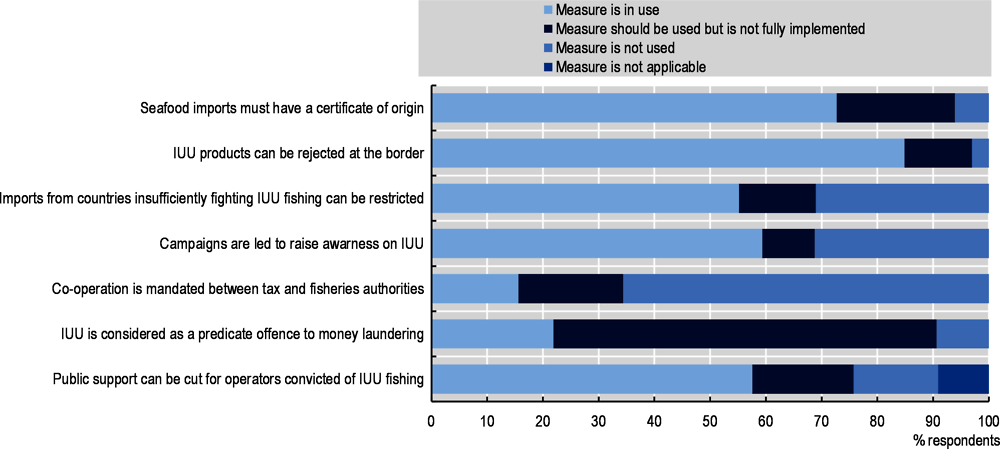

Overall, evidence shows that the average up-take of best practices is highest for port state measures (the average indicator scores 0.83 for all respondents) and for vessel registration and authorisation to operate in the EEZ (average scores are 0.81 for both) (Figure 3.1). At the other end of the spectrum, market measures are the least widely used across respondents (with an average score of 0.64). For example, only 55% of respondents fully implement restrictions on imports from countries identified as insufficiently fighting IUU fishing. Only one in three respondents have a legal framework mandating tax authorities to co-operate and share information with fisheries authorities so as to ease identification of the beneficial owners of vessels engaging in IUU fishing, and only one in six respondent fully implement it.

There has nevertheless been progress since 2005 in all areas of government intervention against IUU fishing. The most notable area of progress is port state measures, which were not widely used in 2005 but which in 2018 received the highest score on average for all respondents (Section 3.4). Much progress has also been made on several market measures. In particular, all respondents to both the 2016 and the 2019 surveys reported they could reject products originating from IUU fishing at the border in 2018, while only 38% of them could do so in 2005.

Registration and authorisation processes already had a relatively high uptake of best practices in 2005. However, several measures have seen significant recent progress. For example, while in 2005, only 36% of respondents prohibited parallel registration of vessels in more than one country, 93% did so in 2018.

Figure 3.1 shows a high variation in scores across countries and economies, whereby some fully implement all the measures listed under some indicators, while others implement very few.10 This demonstrates scope for peer learning and bilateral co-operation between countries and economies at the forefront of the fight against IUU fishing and those who need to reinforce their regulatory arsenals.

Evidence also shows that particular attention should be given to improving transparency and co-operation in all domains, including in areas for which overall scores are high. For example, only 19% of respondents fully implement legal provisions that mandate the publication of the lists of vessels identified as engaging in IUU fishing and about 40% of respondents still do not publish their national list of domestic vessels authorised to fish in the domestic EEZs.

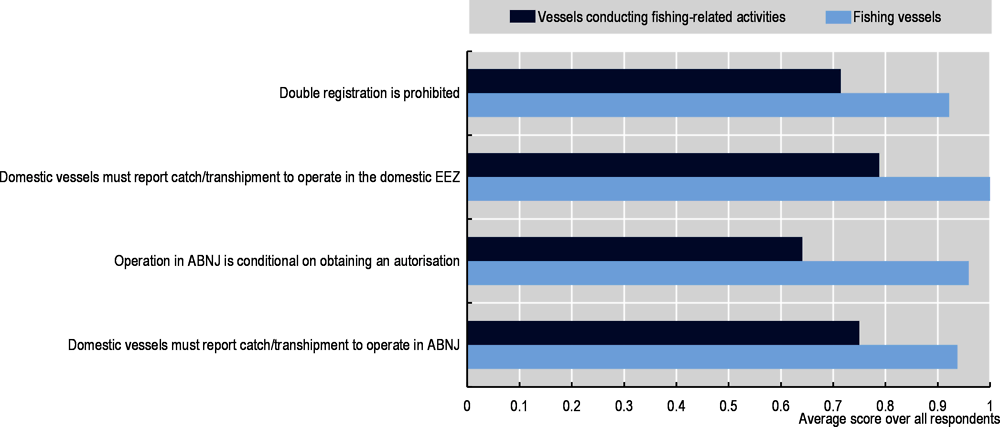

The information collected suggests that oversight on and regulation of transhipments (whereby fish are transferred from fishing boats onto larger refrigerated vessels, which then carry the fish to port, while fishing vessels continue fishing) are much less sophisticated than the oversight and regulation of fishing activities themselves. Given how extensive transhipment has become (Widjaja et al., 2019[17]), it is crucial to strengthen dedicated registration and authorisation processes to avoid unscrupulous operators using them to enter their products into the value chain.

Making public detailed information on vessels is key in the fight against IUU fishing

Governments have three main areas of responsibilities in regulating fishing before vessels actually start operating. First, vessels should be registered, that is documented and assigned a country’s flag. This allows the vessel to travel internationally and implies it is subject to that flag state’s laws. The more detailed and verified the information is included in the vessel registration processes, the easier it is to track vessel activities and to prevent and sanction illegal activities (FAO, 2001[24]).

Vessels then need authorisations to operate. Coastal states can deliver authorisations to operate in their economic exclusive zone (EEZ) to both their domestic fleet and to foreign vessels.11 In addition, vessels typically also need an authorisation from their flag state to operate in areas beyond national jurisdiction (ABNJ) and in the EEZs of foreign countries.

Authorisation regimes are a key tool for coastal states to combat IUU fishing and for the sustainable management of resources in their EEZ as it allows control over the total size of the fleet, its distribution over fishing areas, seasons, and target species, and the gear that can be used. Well-designed authorisation regimes contribute to limiting over-capacity and incentives to fish beyond sustainable limits. They also provide key information on actual fishing capacity, which allows to better estimate the requirements for MCS, as well as the impact of exerted fishing pressure on resources and ecosystems in domestic waters.

Authorisation regimes are a key tool for flag states as regulating domestically-flagged vessels in ABNJ and in the EEZs of other countries is key to ensuring they behave responsibly outside the EEZ, even where regulation, MCS, and governance are weaker. To ensure vessels operate in ways and in areas that are consistent with the authorisations they have been granted, authorities need to collect information on their operations. Fighting IUU fishing therefore requires authorisation regimes to be conditional on comprehensive and timely information-sharing by vessels.

Registration and authorisation have become more comprehensive but chasing IUU operators requires even more transparent information

Registration

Overall, surveyed countries and economies register vessels more comprehensively and with regulations that are more stringent for granting authorisations for fishing activities then was the case 15 years ago (Hutniczak, Delpeuch and Leroy, 2019[23]).12

In 2018, all respondents required fishing vessels to be registered (while only 57% of the subset of countries and economies surveyed in 2005 and 2018 did so in 2005). Comprehensiveness of the information collected through registration has improved: all respondents required information on vessels’ characteristics13 and details on the natural or legal persons in whose names vessels are registered. In addition, all respondents, except Costa Rica, also asked for details on the natural or legal persons responsible for managing the operations of the vessel.

There remains scope for improvement to chase illegal activities through registration by looking into a vessel’s history and beyond vessel owners and operators. The frontier of good registration practice now lies in the use of unique vessel identifiers (UVI) and the collection of information on the beneficial owners of vessels; that is, the natural persons who ultimately control vessel activities and benefits from them. Assigning vessels a unique, verified and permanent identifier such as an IMO number facilitates MCS by avoiding cases whereby vessels change flags or names in order to escape global oversight, or to quickly register in another jurisdiction when their illegal activities are discovered (Environmental Justice Foundation (EJF), 2013[31]). Yet, in 2018, a quarter of respondents did not require an IMO number to register fishing vessels and a third did not require one to register vessels conducting fishing-related activities.

Including information on the beneficial owners of vessels is essential in order to sanction those who ultimately benefit from criminal activities and change their risk/benefit prospects (Hutniczak, Delpeuch and Leroy, 2019[23]; FATF/OECD, 2014[32]). Yet, ensuring the availability of information on the beneficial owner of fishing activities is nevertheless challenging for authorities due to the complex and multi-jurisdictional legal arrangements that often characterise the fisheries sector. Partly as a result, only 64% of respondents report that they request information on beneficial owners when registering fishing vessels, while less than half do so for vessels that conduct fishing-related activities.

Authorisation

There is generally good uptake of best practices for authorisation regimes, with progress seen since 2005 and 2016. As coastal states, all respondents legally require that both domestic and foreign vessels fishing in their EEZs request authorisation and they all make it mandatory to report the catch in order to obtain and maintain the authorisation to fish. This increases product traceability, and reduces the scope to land illegal catch such as, for example, fish originating from a marine protected area, fish having been caught in excess of allowed quotas or protected species. Most respondents also make authorisation conditional on position reporting via the Vessel Monitoring System (VMS). This allows to verify that a vessel is not fishing in a prohibited area and to monitor suspicious movements such as a speed that is inconsistent with the declared gear, suggesting that another gear is being used fraudulently. Use of VMS for fishing vessels in the EEZ was reported as mandatory by all respondents except Viet Nam (while Colombia mandates it for domestic vessels only and not foreign ones).

As Flag states, all respondents permitting their fleet to fish in ABNJ legally require domestic fishing vessels to obtain a specific authorisation (only 86% of countries surveyed in both 2019 and 2006 requested this in 2005). All respondents, with the exception of Thailand and Viet Nam, can withdraw their authorisations to fish in ABNJ if vessels are found engaging in IUU fishing. The regulation of access to foreign EEZs through bilateral or chartering agreements has also improved. In 2018, all European Union countries surveyed reported implementing such regulation and publicising the lists of vessels authorised to fish in foreign EEZs in the “Who fishes far” database.14

Progress is needed, however, regarding participation in observer programmes, which allow independent specialists employed (or mandated) by governments to monitor vessels in order to ensure compliance with regulations and to better understand at-sea operations, such as where vessels are fishing, which species are being caught and how (i.e. the use of fish aggregating devices), transhipment activities, and catch or by-catch are discarded. About one in five respondents still do not have in place regulations that make observer programmes compulsory.

Aligning processes for vessels conducting fishing-related activities with those for fishing vessels is urgent

Transhipment of fish from fishing vessels onto larger refrigerated cargo vessels has become a widespread phenomenon (Global Fishing Watch, 2017[33]). This can facilitate and reduce the cost of delivering fish to ports while allowing fishing vessels to continue fishing without going back to port to land their catch. Such practice is particularly pervasive in high seas fisheries. In the process, some of the operations that normally happen at port happen at sea; and controlling these requires specific procedures to avoid co-mingling of IUU and non-IUU caught fish prior to landing and further muddying the traceability of supply chains. Monitoring of transhipments is also key to allowing effective estimation of fishing pressure as it allows fishing vessels to remain at sea longer and exert a continuous fishing effort. It can also help identify fishing vessels that remain at sea full-time, thus escaping port inspections. Finally, unmonitored transhipment is a blind spot of choice for all kinds of trafficking and criminal activities (UNODC, 2011[12]; Witbooi et al., 2020[11]).

While progress has been made since 2005, registration and authorisation processes for fishing-related activities remain more lax than for fishing vessels (Figure 3.2). In fact, there has been little progress since 2016 when this issue was raised in Hutniczak, Delpeuch and Leroy (2019[23]). For example, while all respondents give authorisations to fish in their EEZ conditional on catch reporting, over 20% do not require domestic vessels conducting fishing-related activities in their EEZ to report transhipments of fish. Regulation of fisheries-related activities outside the EEZ is even more lax as over a fifth of respondents allow vessels to conduct such activities in ABNJ without any authorisation (43% of respondents having replied to earlier surveys did so in 2005). Costa Rica, France, and Viet Nam reported no or minimal oversight of fisheries-related activities.

More generally, laxer regulation of fisheries-related activities may in part result from the difficulty in defining these activities and putting in place an appropriate regulatory framework. Transhipment of fish from a fishing vessel to a refrigerated cargo vessel is the classic example of a fishing-related activity which implies physical movements of fish. However, the transfer of fuel, food and crewmembers from “mother ships” to fishing vessels are often included in this category of activities even though regulation needs are potentially different. International discussions to clarify the stakes and to identify best practices in the regulation of these activities would contribute to improving their regulation, monitoring and control.

Increased transparency is needed to improve control

A need for more transparency stands out as an important area for needed progress with respect to the registration and authorisation processes. Information on registered and authorised vessels are still not made public by several countries and economies (Figure 3.3). For example, only a handful of respondents reported publishing the lists of foreign vessels authorised to fish and conduct fishing-related activities in the EEZ. In addition, only one in five respondents reported properly publishing lists of vessels identified as engaging in IUU fishing.

Publicity of information is particularly important regarding activities happening in ABNJ as these areas are more difficult to monitor (Berkes, 2006[34]). Yet 59% of respondents do not publish the list of vessels authorised to conduct fishing-related activities in ABNJ (Figure 3.3).15 This is a missed opportunity to improve the fight against IUU fishing at a low cost. Easy access to details on vessels would facilitate MCS at sea and in ports. In addition, public availability, and regular updates of IUU vessels lists allow coastal, flag and port States to crosscheck information on vessels and, accordingly, deny licenses, re-flagging or port entry. It could also serve as a basis for insurers and other service providers to exclude these vessels from their services and help all stakeholders involved in the sector (including fishers, NGOs and researchers) to detect illegal activities, alert competent authorities, and sometimes even stop illegal activities (Cavalcanti and Leibbrandt, 2017[35]).

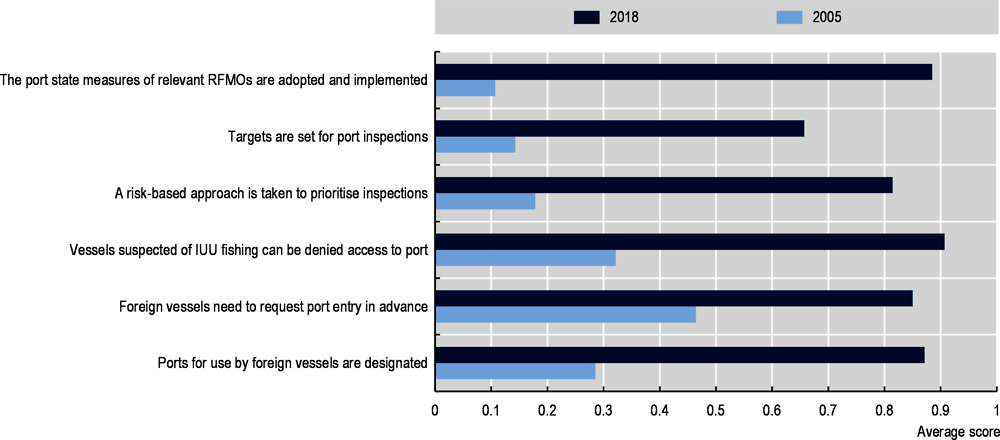

Since monitoring and inspecting vessels at sea is expensive and sometimes difficult, authorities have increasingly turned to Port State Measures (PSMs), as an additional, often less expensive and safer tool to fight IUU fishing (Kopela, 2016[36]; Doulman and Swan, 2012[37]). Average scores over all respondents displayed in Figure 3.4 show that many PSMs are now widely implemented across countries and economies. These include: designating a list of ports for use by foreign-flagged vessels to better direct available control capacity; demanding advance requests from foreign vessels to use ports (with a view to allow coastal states to verify information with the vessel’s flag state), and the possibility to deny port entry to vessels suspected of IUU fishing. As inspecting all vessels entering ports is not possible due to time and economic constraints, authorities have increasingly adopted risk-based approaches to inspection and have set quantitative targets for the number of port inspections. Together these measures can limit the scope for illegally caught products to enter the market. They also increase costs for operators engaging in IUU fishing by forcing them to consume fuel and to spend time in search of weakly-governed ports where to land their illegal catch (Petrossian, Marteache and Viollaz, 2014[38]).

The average score for the indicator aggregating all questions related to PSMs is of 0.83 for 2018, the highest score of all indicators.16 For countries and economies having responded to both to the 2019 and 2006 surveys, this score increased from 0.25 in 2005 to 0.83 in 2018. This progress correlates with the development of the FAO Port State Measure Agreement (PSMA) (FAO, 2009[25]), which sets out universal minimum standards to prevent IUU fishing products from being landed in ports by foreign-flagged vessels. Adopted in 2009, it came into force in 2016 and has since then been ratified, accepted or approved by 85% of respondents (and all OECD countries surveyed, with the exceptions of Colombia and Mexico). It is hard to identify the exact role played by the PSMA in the progress observed, as this observed progress could also indicate the reverse causality with the agreement being the result of the growing realisation that some measures were needed and wanted by governments. However, this seems to suggest that international discussions on best practices are associated with widespread adoption. It is interesting to note that the PSMA process seems to have had positive spill-over effects as some measures that are part of the Agreement, such as the designation of ports for use by foreign vessels, have been adopted even by States which are not yet signatories. Similar initiatives could usefully be launched in areas that are less universal, such as markets measures.

Illicit trade in seafood products is a global business through which operators make high profits at often comparatively low financial risk (Sumaila et al., 2020[2]). Market measures are thus precious tools in the fight against IUU fishing that lower associated benefits and increase financial risk by closing markets to products that originate from IUU fishing. Market measures generally involve improving seafood traceability, raising consumer awareness of IUU fishing as well as restricting public support for operators engaging in IUU fishing and restricting market access for IUU-caught fish (without creating unnecessary barriers to trade seafood products) (FAO, 2001[24]).

Some measures have become almost universal among survey respondents. For example, they all report that regulation requires imported seafood to be accompanied by a certificate of origin confirming their legal sourcing, with the exceptions of Australia and Chile.17 Overall, however, the indicator on markets measures has the lowest average score of all indicators computed for 2018 (0.64). Indeed, despite growing evidence of their effectiveness (Ma, 2020[39]), a number of market measures remain sparsely used (Figure 3.5).

Measures by seafood-importing countries to close their markets to products originating from IUU fishing have been designed to not only affect IUU fishing benefit prospects, but also to encourage exporting countries to intensify their fight against IUU fishing, in co-operation with importing countries. Such measures are used by EU countries and the United States. The EU scheme is based on a colour-coded warning scheme, which informs third countries if problems are detected in their fulfilling of international and regional rules related to the prevention of IUU fishing. This can then lead to the introduction of provisions for embargoes on fish products originating from countries identified as non-cooperating (Hutniczak, Delpeuch and Leroy, 2019[23]). In the United States, the Seafood Import Monitoring Program (SIMP), establishes reporting and recordkeeping requirements for imports of selected seafood products on the basis of a risk-based traceability programme. Importing firms of such designated products are required to report key data from the point of harvest to the point of entry into the market. This can potentially affect the competitiveness of exporting countries and sourcing choices of importing firms, hence creating incentives for improved policies against IUU fishing in exporting countries. Other OECD countries are considering similar measures.

Measures that should be much easier to set up, such as campaigns to raise consumer awareness and create demand, and potentially a premium, for certified and legally sourced products, are also not universally used by respondents (Petrossian, Weis and Pires, 2015[40]).

Only about one in three respondents have a legal framework mandating tax authorities to co-operate and share information with fisheries authorities to facilitate the detection of illicit proceeds and the identification of nationals who are the beneficial owners of IUU fishing vessels and only 16% of respondents reported fully implementing this legal framework. Increasing co-operation between government departments and agencies is key to identifying and prosecuting criminals at all levels of the fishing industry (Witbooi et al., 2020[11]).

In addition, it is important to trace the financial flows generated by IUU fishing to identify the complex networks of related criminal activities. Considering IUU as a predicate offence for money laundering would allow for more in-depth investigations and the use of adequate sanctions. Yet, while 91% of respondents legally consider IUU as a predicate offense for money laundering, only 22% reported fully implementing this regulation.

Progress remains to be made in cutting government support to operators engaging in IUU fishing. This is a key target of SDG 14, and one area of focus for negotiations on fisheries subsidies at the World Trade Organization (Chapter 4). However, 15% of respondents still do not have legal provisions in place to restrict support for operators convicted of IUU fishing and only 58% of respondents reported properly implementing the restrictions.

Recent progress has been made in fighting IUU fishing through stricter regulation, closer monitoring and control and greater international co-operation. Most notably, port state measures ‒ by which authorities monitor and control activities at port ‒ are today widely used internationally. Progress has also been made in aligning vessel registration and authorisation processes with international recommendations. Consolidating the benefits of such progress however requires taking extra steps to firmly close waters and markets to IUU operators and the products they harvest globally, while investing in measuring the effectiveness of country actions against IUU fishing would help fine-tune priorities and motivate on-going reforms.

In particular, vessel registration and authorisation processes need to become fully transparent in order to facilitate co-operation between governments, across branches of government and between stakeholders so they can join forces to better track IUU activities. G7 and G20 countries, which have voiced a shared ambition to curb IUU fishing following conferences in Charlevoix (2018) and in Osaka (2019), could lead the way by making public their vessel registries as well the lists of authorised vessels and those that have been identified as engaging in IUU fishing. The issuing of a unique vessel identifier in the registration process should be adopted and harmonised, making use of International Maritime Organization (IMO) numbers whenever possible. The international community should also collectively decide on best practices so as to gather information on who ultimately controls and benefits from vessel activities (i.e. the “beneficial owners” of vessels); indeed, many countries and economies have a legal framework to do so, but report practical difficulties.

International co-operation is necessary to strengthen the regulation of transhipments, whereby fish are transferred from fishing boats onto larger refrigerated vessels, which then carry the fish to port (while fishing vessels continue fishing), so that products of IUU fishing do not enter the value chain unnoticed during these operations at sea. Better definitions and regulations of other fishing-related activities – such as the transfer of fuel, food and crew from “mother ships” to fishing vessels – would also improve control of fleets.

Wider adoption of market measures internationally would increase traceability in seafood value chains and close markets and access to support and services to operators that engage in IUU fishing. Current negotiations on fisheries subsidies at the World Trade Organization (WTO) offer a unique opportunity to prohibit subsidies that contribute to IUU fishing.

This chapter builds on the analysis of answers to a survey run in 2019 by the OECD Secretariat inquiring about the legal framework that was in place to deter, identify and punish IUU fishing, and the extent to which it was implemented, in 2018, in individual countries and economies.

A total of 33 countries and economies replied to the survey, including 26 OECD countries (Australia, Belgium, Canada, Chile, Colombia, Denmark, Estonia, France, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Japan, Korea, Latvia, Lithuania, Mexico, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Poland, Slovenia, Sweden, Turkey, the United Kingdom and the United States), as well as Argentina, China, Costa Rica, Indonesia, Chinese Taipei, Thailand and Viet Nam – together referred to as “emerging economies”.

The survey followed the methodology used in Hutniczak, Delpeuch and Leroy (2019[23]), with the addition of a few new questions that were included following suggestions from respondents to the previous survey. Questions were defined to reflect the best practices and established standards from the relevant literature, in particular international agreements and guidelines related to the fight against IUU fishing adopted by the FAO.

Questions were organised into six sections, at the level of the most important domains of government intervention against IUU fishing:

Authorisation to operate and access resources in the domestic EEZ

Authorisation to operate and access resources outside the domestic EEZ

To identify patterns and trends in performance, each answer was scored between 0 and 1, with increasing scores indicating higher levels of adoption and implementation of the regulation and measures at stake in each question. Specifically: a score of 0 indicates no regulation was in place; 0.2 indicates there was a regulation but reported not to be implemented; 0.5 indicates the regulation was reported to be partially implemented; and 1 refers to full implementation. Scores were then aggregated into six indicators, at the level of the most important domains of government intervention against IUU fishing. Indicator scores were also averaged over all respondents – or OECD countries and emerging economies.

As the survey included a series of questions which had been submitted to countries participating in the 2005 survey, evidence of progress was computed in relation to issues for which comparative data existed. A subset of 14 of the respondents to the present survey also replied to the 2005 survey: Belgium, Germany, Ireland, Italy, the Netherlands, Slovenia, Australia, Canada, Japan, Korea, New Zealand, Norway, Turkey, and the United States. The countries surveyed in 2019 were also surveyed in 2016.

Annex Table 3.A.1 lists all questions; the weights attributed to individual questions within each indicator; additional information regarding the information gathered through the question, including, where relevant, the criteria on which partial and full implementation of the measure at stake would be based as well as the references on which the questions were based.

References

[34] Berkes, F. (2006), “ECOLOGY: Globalization, Roving Bandits, and Marine Resources”, Science, Vol. 311/5767, pp. 1557-1558, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1122804.

[22] Cabral, R. et al. (2018), “Rapid and lasting gains from solving illegal fishing”, Nature Ecology & Evolution, Vol. 2/4, pp. 650-658, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-018-0499-1.

[35] Cavalcanti, C. and A. Leibbrandt (2017), “Impulsivity, voluntary cooperation, and denunciation among fishermen”, Department of Economics Disccussion Paper, Vol. No. 10/17.

[9] Costello, C. et al. (2020), “The future of food from the sea”, Nature, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-2616-y.

[37] Doulman, D. and J. Swan (2012), Guide to the background and implementation of the 2009 FAO Agreement on Port State Measures to Prevent, Deter and Eliminate Illegal, Unreported and Unregulated Fishing, FAO Fisheries and Aquaculture Circular.

[31] Environmental Justice Foundation (EJF) (2013), Bringing Fishing Vessels Out Of The Shadows. The urgent need for a Global Record of fishing vessels and Unique Vessel Identifier, Environmental Justice Foundation, London, https://ejfoundation.org/resources/downloads/EU_Global_Record_briefing_low-res-version_ok.pdf.

[26] FAO (2017), Voluntary Guidelines for Catch Documentation Schemes, http://www.fao.org/fi/static-media/MeetingDocuments/CDS/TC2016/wpAnnex.pdf.

[41] FAO (2015), Voluntary Guidelines for Securing Sustainable Small-Scale Fisheries in the Context of Food Security and Poverty Eradication - At a Glance, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.

[25] FAO (2009), Agreement on Port State Measures to Prevent, Deter and Eliminate Illegal, Unreported and Unregulated Fishing.

[24] FAO (2001), International Plan of Action to Prevent, Deter, and Eliminate Illegal, Unreported and Unregulated Fishing, http://www.fao.org/3/a-y1224e.pdf.

[42] FATF (2012), International Standards on Combating Money Laundering and Financing of Terrorism & Proliferation (updated October 2016), Financial Action Task Force.

[32] FATF/OECD (2014), FATF Guidance: Transparency and Beneficial Ownership, http://www.fatf-gafi.org/media/fatf/documents/reports/Guidance-transparency-beneficial-ownership.pdf.

[7] Gaines, S. et al. (2019), The Expected Impacts of Climate Change on the Ocean Economy, https://doi.org/www.oceanpanel.org/.

[6] Gaines, S. et al. (2018), “Improved fisheries management could offset many negative effects of climate change”, Science Advances, Vol. 4/8, p. eaao1378, https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.aao1378.

[4] Galaz, V. et al. (2018), “Tax havens and global environmental degradation”, Nature Ecology & Evolution, Vol. 2/9, pp. 1352-1357, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-018-0497-3.

[43] Global Fishing Watch (2017), Analysis of Possible Transshipment Activity in the Indian Ocean Tuna Commission Convention Area in 2017 through the Use of AIS Data, https://globalfishingwatch.org/wp-content/uploads/GFW_IOTC_TranshipmentReview_2017.pdf.

[33] Global Fishing Watch (2017), The Global View of Transshipment: Revised Preliminary Findings, https://globalfishingwatch.org/wp-content/uploads/GlobalViewOfTransshipment_Aug2017.pdf.

[20] Global Ocean Commission (2014), From Decline to Recovery – A Rescue Package for the Global Ocean, https://www.mpaaction.org/sites/default/files/Global%20Ocean%20Commission_2014_From%20Decline%20to%20Recovery.pdf.

[19] High Seas Task Force (2006), Closing the Net Stopping illegal fishing on the high seas, Final report of the Ministerially-led Task Force on IUU Fishing on the High Seas.

[23] Hutniczak, B., C. Delpeuch and A. Leroy (2019), “Closing Gaps in National Regulations Against IUU Fishing”, OECD Food, Agriculture and Fisheries Papers, No. 120, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9b86ba08-en.

[28] Hutniczak, B., C. Delpeuch and A. Leroy (2019), “Intensifying the Fight Against IUU Fishing at the Regional Level”, OECD Food, Agriculture and Fisheries Papers, No. 121, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/b7b9f17d-en.

[3] Konar, M. et al. (2019), The Scale of Illicit Trade in Pacific Ocean Marine Resources, https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.32575.25764.

[36] Kopela, S. (2016), “Port-State Jurisdiction, Extraterritoriality, and the Protection of Global Commons”, Ocean Development & International Law, Vol. 47/2, pp. 89-130, https://doi.org/10.1080/00908320.2016.1159083.

[39] Ma, X. (2020), “An economic and legal analysis of trade measures against illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing”, Marine Policy, Vol. 117, p. 103980, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2020.103980.

[29] OECD (2020), Fisheries, aquaculture and COVID-19: Issues and policy responses, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://read.oecd-ilibrary.org/view/?ref=133_133642-r9ayjfw55e&title=Fisheries-aquaculture-and-COVID-19-Issues-and-Policy-Responses.

[27] OECD (2005), Why Fish Piracy Persists: The Economics of Illegal, Unreported and Unregulated Fishing, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264010888-en.

[30] OECD (forthcoming), “COVID-19 and multilateral fisheries management”.

[5] Österblom, H. (2014), “Catching Up on Fisheries Crime”, Conservation Biology, Vol. 28/3, pp. 877-879, https://doi.org/10.1111/cobi.12229.

[38] Petrossian, G., N. Marteache and J. Viollaz (2014), “Where do “Undocumented” Fish Land? An Empirical Assessment of Port Characteristics for IUU Fishing”, European Journal on Criminal Policy and Research, Vol. 21/3, pp. 337-351, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10610-014-9267-1.

[40] Petrossian, G., J. Weis and S. Pires (2015), “Factors affecting crab and lobster species subject to IUU fishing”, Ocean & Coastal Management, Vol. 106, pp. 29-34, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2015.01.014.

[8] Pörtner, H. et al. (2019), IPCC, 2019: Summary for Policymakers. In: IPCC Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate.

[10] Reilly, A. (2018), Overview of Food Fraud in the Fisheries Sector, FAO, Rome, http://www.fao.org/3/I8791EN/i8791en.pdf.

[1] Sandin, S. (ed.) (2009), “Estimating the Worldwide Extent of Illegal Fishing”, PLoS ONE, Vol. 4/2, p. e4570, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0004570.

[18] Spijkers, J. et al. (2019), “Global patterns of fisheries conflict: Forty years of data”, Global Environmental Change, Vol. 57, p. 101921, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2019.05.005.

[16] Sumaila, U. and M. Bawumia (2014), “Fisheries, ecosystem justice and piracy: A case study of Somalia”, Fisheries Research, Vol. 157, pp. 154-163, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fishres.2014.04.009.

[2] Sumaila, U. et al. (2020), “Illicit trade in marine fish catch and its effects on ecosystems and people worldwide”, Science Advances, Vol. 6/9, p. eaaz3801, https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.aaz3801.

[15] Telesetsky, A. (2014), “Laundering Fish in the Global Undercurrents: Illegal, Unreported, and Unregulated Fishing and Transnational Organized Crime”, Ecology Law Quarterly, Vol. vol. 41/no. 4, pp. pp. 939–997, http://www.jstor.org/stable/44320331.

[14] Tickler, D. et al. (2018), “Modern slavery and the race to fish”, Nature Communications, Vol. 9/1, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-07118-9.

[12] UNODC (2011), Transnational Organized Crime in the Fishing Industry: Focus on: Trafficking in Persons Smuggling of Migrants Illicit Drugs Trafficking.

[13] Urbina, I. (2019), The Outlaw Ocean : Journeys across the last Untamed frontier.

[17] Widjaja, S. et al. (2019), Illegal, Unreported and Unregulated Fishing and Associated Drivers., https://doi.org/www.oceanpanel.org/.

[11] Witbooi, E. et al. (2020), Organised Crime in the Fisheries Sector., Washington, DC: World Resources Institute, https://oceanpanel.org/blue-papers/organised-crime-associated-fisheries.

[21] World Bank (2017), The Sunken Billions Revisited: Progress and Challenges in Global Marine Fisheries, The World Bank, https://doi.org/10.1596/978-1-4648-0919-4.

Notes

← 1. While the impact of IUU fishing has not been estimated at a global scale, the contribution of sustainable fisheries to global food security today and in the future is discussed in Costello et al. (2020[9]). IUU compromises this contribution by diverting seafood products to illegal markets that are not always accessible to consumers – and who cannot easily find alternative nutritious food – and by affecting the sustainability of resources and thus their food production potential.

← 2. What is categorised as a crime varies across jurisdictions.

← 3. The most recent estimate of the global illegal and unreported annual catch dates back to 2009 (Agnew et al., 2009[1]).

← 4. There are other useful ways to fight IUU fishing which are outside the scope of the present paper but deserve attention and work. They include both public measures such as increasing sanctions for IUU activities, and actions by the fisheries sector and civil society that contribute to greater transparency and traceability of seafood products (Widjaja et al., 2019[17]).

← 5. This chapter complements work done by the FAO to track progress made by countries in reaching SDG target 14.6 with indicator 14.6.1 “Progress by countries in the degree of implementation of international instruments aiming to combat illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing”. Aggregate scores obtained by countries can be accessed at: http://www.fao.org/sustainable-development-goals/indicators/1461/en/. This chapter investigates similar issues with a greater level of detail to identify where reforms are needed in relation with precise policies and regulations.

← 6. Typically, for each element of regulation or policy recognised to be necessary to fight IUU fishing, countries were asked whether a legal framework or policy provisions exists and, if so, whether it is fully, partially or not implemented (however, there was no attempt to measure countries’ respective effectiveness in fighting IUU through the measures adopted and implemented). Countries were also invited to share references to the relevant legal frameworks and policy provisions as well as links to publically available information in questions related to transparency of information. The OECD revised the information provided by national authorities to the extent possible, and exchanged with national authorities to clarify and amend the information provided when necessary. Information was included in the database pending final validation by national authorities.

← 7. The scoring key for each question is detailed in Annex Table 3.A.1.

← 8. Scores are averaged over countries, counting all countries equally. The weights given to the different questions within indicators are reported in Annex Table 3.A.1. Indicators are built on the assumption that all the measures included under each indicator are complementary and that the best-case scenario for countries is to implement them all. It is, however, recognised that this may not be the case and that countries may have different priorities and portfolios of policies and practices to fight IUU fishing due to the particular situation of their fisheries.

← 9. Evidence of progress since 2005 is based on the responses to the subset of questions, which were already included in the 2006 survey referring to 2005. A subset of 14 of the respondents to the 2019 survey also replied to the 2006 survey: Australia, Belgium, Canada, Germany, Ireland, Italy, Japan, Korea, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Slovenia, Turkey, and the United States. The countries surveyed in 2019 were also surveyed in 2017, and the set of questions was very similar. Progress since 2016 is reported only where it is notable.

← 10. In line with the findings in (Hutniczak, Delpeuch and Leroy, 2019[23]) that the degree of implementation of best practices against IUU fishing appears to be often closely related to gross domestic product (GDP) per capita, average indicators for responding OECD countries score higher than those recorded for non-OECD emerging economies. The difference is however limited for vessel registration and authorisation to operate in the EEZ.

← 11. Under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), in force since 1994, coastal states, including island nations, have sovereign rights to the natural resources of the waters stretching up to 200 nautical miles from their coasts. Rights over this area, defined as their exclusive economic zone (EEZ), also come with the responsibility to monitor and control fishing and fishing-related activities.

← 12. FAO has developed the Global Record of Fishing Vessels, Refrigerated Transport Vessels and Supply Vessels (Global Record), an online comprehensive and updated repository of vessels involved in fishing operations compiled by State authorities and RFMOs, http://www.fao.org/global-record/background/about/en/.

← 13. Vessels’ characteristics include information such as length, tonnage, fishing method, engine power, and date of construction.

← 15. For example, researchers who use AIS data to analyse transhipment could double check whether the transhipments spotted using satellite data were legally authorised or not and accordingly alert authorities (Global Fishing Watch, 2017[43]).

← 16. While high scores are seen overall for Port State Measures, some respondents reported issues in implementing them. This suggests room for improvement even in countries participating in the PSMA.

← 17. The Voluntary Guidelines for Catch Documentation Schemes released on 5 April 2017 (FAO, 2017[26]) constitute a valuable source of guidance for the design of a CDS.