4. The role of STRATA in the evidence-informed decision-making system

This chapter examines the recent institutional transformation of the Government Strategic Analysis Centre (STRATA). It presents its new mandates in the area of strategic foresight, monitoring and evaluation as stipulated by the law of strategic governance. This chapter suggests that STRATA should focus its participation in the monitoring of planning documents to analytical support and focus on being an excellence centre for evaluations. Moreover, the chapter provides an assessment of the role that is entrusted in STRATA in promoting the quality of RIAs and ex post evaluations of regulations. Finally, it analyses the Centre’s recent organisational changes and discusses, in particular, the importance of the board of STRATA. The report suggests to continue building on STRATA’s recent transformation and proposes ways to foster trust, accountability and legitimacy as concerns STRATA’s operations and outputs.

In 2017, the Lithuanian Science and Education Monitoring and Analysis Centre (MOSTA) was moved under the responsibility of the Office of the Government. This transfer was motivated by a strategic need for leadership in the generation of evidence and analysis for the whole of government. In 2019, MOSTA was officially transformed into the Government Strategic Analysis Centre (STRATA) with the mission to foster high-quality evidence and public knowledge based on objective information. The intention is to leverage the expertise of the centre to strengthen the evidence-informed decision-making mechanisms to enable sound strategic governance from a whole of government perspective. At the time of conducting this assessment, the transformation process was ongoing. While STRATA’s mandate has been expanded significantly in a formal sense, the challenge is to assess whether the structure and resources have sufficiently evolved since the old mandate as MOSTA to meet the new challenges and needs. The question is to identify the further adjustments that are necessary to ensure that the well-intended strategic decisions effectively reach their goals.

In this context, this chapter offers an overview of STRATA’s current mandates and suggests refocusing its responsibilities on evaluation, foresight and regulatory impact assessment-related activities in order to increase its legitimacy and impact. Second, the chapter discusses the functions and decision-making processes related to STRATA’s role as a policy advisory. The chapter analyses the governance structure of STRATA, the establishment of its board and the development of activity plans. It recommends increasing the transparency of its decision-making processes and ensuring enhanced visibility of its work. Finally, the chapter identifies some operational challenges related to STRATA’s human resources, organisation and budget, and suggests that STRATA pursue its transformation to better reflect its new ambitious mandate.

STRATA has received an extensive mandate

The current legal framework gives STRATA a wide variety of responsibilities, which intervene at different stages of the policy-making cycle. Indeed, the Government Strategic Analysis Centre is responsible for:

carrying out foresight activities, monitoring and evaluation in the context of the Strategic Governance system (Parliament of Lithuania, 2020[1])

conducting thematic studies in the areas of expertise related to the previous MOSTA mandate

promoting the quality of regulatory impact assessment and ex post assessments

The new strategic governance system under development gives a large role to STRATA

In 2020, a new strategic governance law (XIII-3096) was adopted by Parliament, which aims at rationalising the strategic and planning system (Parliament of Lithuania, 2020[1]). In particular, this law seeks to minimise the number of strategic planning frameworks, in order to improve their implementation and facilitate their monitoring. STRATA has been given a mandate in several stages of the preparation and implementation of the main strategic planning documents of the Lithuanian government. In particular, STRATA has an explicit role in conducting strategic foresight for the preparation of the State Progress Strategy 2050 and the National Progress Plan 2030, as well as monitoring and evaluating these plans (see Figure 2.5 in Chapter 2).

Strategic foresight and planning

Articles 13-2 and 15-2 of the strategic governance law mandate STRATA to provide a “situation analysis” and to the Office of the Government for both:

the State Progress Strategy (SPS), which is a 30-year strategy. The SPS for “Lithuania 2050”, will be presented to the Parliament before the 1st of June, 2022, according to article 25-6 of the law of strategic governance (Parliament of Lithuania, 2020[2]);

and the National Progress Plan, which is a 10-year strategic plan. The NPP for 2021-2030 was approved by the government on the 9th September 2020 (Government of Lithuania, 2020[3]) (Parliament of Lithuania, 2020[1]).

According to the recently approved Strategic Governance Methodology (Government of Lithuania, 2021[4]), STRATA together with the Office of Government prepare the “future scenarios” based on strategic foresight methods. These scenarios are reviewed by the government. The SPS project is then prepared based on the selected scenario (Government of Lithuania, 2021[4]).

Monitoring

Article 15-5 of the strategic governance law gives STRATA the mandate to monitor the implementation of the 10 strategic goals and 50 key performance indicators of the State Progress Strategy, together with the Ministry of Finance and the Office of Government (Parliament of Lithuania, 2020[1]).

However, the exact distribution of tasks between STRATA and the Office of the Government in this regard has yet to be determined. The methodology for the strategic governance framework suggests that STRATA needs to prepare the report analysing the strategic objectives and their impact indicators of the National Progress Plan annually (Government of Lithuania, 2021[4]). The same methodology gives a role to monitor the use of funds associated with the implementation of the NPP to the Ministry of Finance. The individual Development Programmes, on the other hand, should be monitored by each ministry in their area of competencies. Each ministry reports on the implementation of the programmes to the Office of the Government directly.

Evaluation

Moreover, STRATA has also been mandated to evaluate the implementation of the NPP. Article 15-7 of the law of Strategic Governance mandates STRATA to conduct “intermediary evaluations and a final evaluation” of the NPP (Parliament of Lithuania, 2020[1]). Some ambiguities remain, however, as to how these evaluations will be conducted, whether they are in fact a sort of a monitoring, or whether they really involve in-depth analytical work and with what resources.

STRATA has also retained its previous mandate in the area of education, science and innovation

STRATA has retained its previous functions stemming from its old MOSTA mandate. Thus, it continues to perform forward-looking activities as well as other analytical studies in the following areas (see Table 4.1 for examples of these studies):

Workforce needs, as per the 2016 law of employment mandates (Parliament of Lithuania, 2016[5]).

Human and vocational training needs, as per the 1997 law of vocational education and training (Parliament of Lithuania, 1997[6]).

Supply of higher education competences, as per the 2009 law on higher education and research (Parliament of Lithuania, 2009[7]).

Sciences, Technology and Innovation, as per the 2018 law on technology and innovation. (Parliament of Lithuania, 2018[8]).

This strong focus on education, science and innovation, however, may impact the perception of STRATA as the whole of the government analysis centre. Indeed, focusing important resources on analysis in these thematic topics may detract STRATA from fulfilling its other functions to the best of its ability. The Lithuanian government could therefore consider transferring some of these functions back to the Ministry of Education, Science and Sport, which is in need of increasing its internal capacities for analysis. This would concern in particular the analysis of workforce needs, human capital and vocational training.

In the recent years STRATA has started to expand into other areas of expertise. It was, for example, asked to provide analysis on the management of economic consequences of COVID-19 pandemic by the Office of Government. Among the current ongoing activities some reflect the increasing scope of STRATA’s mandate such as a project on the “Green Course” opportunities in Lithuania or forecasting the needs for health personnel in Lithuania (STRATA, 2021[9]).

STRATA has a role in promoting the overall quality of regulatory assessments

Regulatory impact assessments

Firstly, STRATA has a role in promoting the quality of the RIAs by providing quality control for high-impact RIAs and general methodological support to ministries. As of 2020, quality control of higher impact legislation is delegated to STRATA (The Decision of the Government Meeting of the 15th of January, (Prime Minister’s Office, 2020[10]). STRATA together with the Office of the Government reviews the preliminary information on RIAs sent by the ministries and decides which legislative projects should be included in the semi-annual high-impact legislation list. In 2021, these semi-annual lists were substituted by a list covering a 3 years period (2021-24) with the possibility for revision (Government of Lithuania, 2021[11]). Once the list is completed, the ministries drafting these legal acts can solicit methodological help from STRATA and the Office of the Government sends the final RIA to STRATA for quality control. STRATA controls the quality of the impact assessment. In 2020, STRATA has controlled the quality of 12 RIAs (STRATA, 2020[12]). (See Chapter 3).

This role in quality control is important. In order to further focus STRATA’s contribution on the technical aspects of this control function, a regulatory oversight body could be created to make final decisions on the substantive quality of RIAs, which would avoid exposing STRATA in a political sense on those decisions and would also give them more weight and legitimacy. STRATA could provide analytical secretariat support to a regulatory oversight body.

STRATA also has a role in quality assurance by offering support to ministries that are drafting “proposals of evidence-informed decisions” (Parliament of Lithuania, 1994[13]), which includes RIAs. In this regard, STRATA has co-operated with ministries on conducting impact assessments. One such example is the ex ante impact assessment of the COVID-19 relief stimulus, where STRATA provided its expert opinion on the impact estimated by the Ministry of Finance (STRATA, 2020[14]). Furthermore, STRATA developed some cross-government RIA methodological guidelines (STRATA, 2020[12]). However, it is only one of several cross-government methodological guidelines for RIA to date.

As highlighted in chapter 3, a clear government-wide framework on co-ordination for RIA could be helpful to clarify the role of STRATA versus other institutions (such as Office of Government, Ministry of Justice, Ministry of Economy and Innovation, Ministry of Interior, Ministry of Finance) in providing methodological support for RIA. Thus, STRATA can act as the main methodological centre for RIA within this government-wide framework. This could allow STRATA, for example, to organise further government-wide training programme on RIA to staff from across the government rather than responding to ad-hoc requests. This would allow STRATA to build on the series of training seminars given in 2020-21.

Ex post assessments

Furthermore, STRATA may also have the mandate to provide quality assurance for ex post regulatory assessments upon request. As detailed in the previous chapter, the Ministry of Justice is in charge of co-ordinating ex post regulatory assessments. The Ministry of Justice plans to solicit STRATA’s advice on the quality of ex post evaluations. Indeed, article 23 of the ex post evaluation methodology prepared by the Ministry of Justice stipulates that ministries can ask STRATA for methodological support in conducting ex post regulatory assessments, in particular for example when sophisticated data analysis is needed (Government of Lithuania, 2021[15]). STRATA is not mandated, however, to respond positively to these demands, in which case ministries can contract out the evaluation.

The co-ordination of ex post evaluation and methodological guidance is a prerogative of the Ministry of Justice, which has extensive competences in legal matters but might lack capacities in analytical tasks and data analysis for evaluation. Following the recommendations made above, STRATA and the Office of the Government could have a greater role in co-ordinating ex post assessments for the former, and in providing methodological support to ensure the quality of these evaluations across government for the latter. In particular, STRATA could act as a focal point for these assessments. It could conduct cross-cutting evaluations that involve several ministries, and offer support for other high-priority evaluations.

STRATA also has a mandate to create and manage a ‘network of analytical competences’’ in public institutions

In order to ensure the overall quality of evidence and its use, STRATA is mandated by article 30 of the law on government to manage a network of public sector analysts (Parliament of Lithuania, 1994[13]). The training carried out by STRATA in the area of RIA, for example, contributes to this mandate.

STRATA should refocus its mandate on its role as the main advisory body in the Lithuanian EIPM system

STRATA’s extensive mandate presents many challenges due to conflicting functions

Overall, the aggregated mandates of STRATA create an incompatible mix of functions: some require strong political influence and commitment (e.g. monitoring the implementation of plans), while others benefit from increased independence and technical legitimacy (e.g. policy advice and evaluation).

Firstly, protection from undue political influence is a crucial element of evaluations’ credibility. This notion can be understood as an evaluation being free from undue political pressure and organisational influence (see Box 4.1 for a detailed explanation of this). The literature distinguishes between several types of independence: structural, functional and behavioural independence.

Independence in analysis and evaluations is indispensable to both ensure the credibility and ultimately the quality of studies. There are 3 main types of independence for the evaluations: structural, functional and behavioural independence (Vaessen, 2018[16]). The first two relate to the management of the evaluation, as regards the object, process as well as human and financial resources necessary to conduct an evaluation. Behavioural independence relates to the unbiasedness and integrity of the evaluator.

As such, independence requires avoiding conflicts of interests, complying with ethical norms of conduct and the independence of the evaluation commissioners themselves. In practice, independence is usually difficult to achieve in internal evaluations, where political influence is often exerted and various political interests are at stake. Accordingly, appointing an external evaluator is a common solution to foster more impartial and trustworthy results.

Source: Piccioto (2013[17]), Evaluation Independence in Organizations, Journal of Multidisciplinary Evaluation; Vaessen (2018[16]), Five ways to think about quality in evaluation, https://ieg.worldbankgroup.org/blog/five-ways-think-about-quality-evaluation (accessed on 13 May 2021); France Stratégie (2016[18]), Comment évaluer l’impact des politiques publiques : un guide à l’usage des décideurs et des praticiens, https://www.strategie.gouv.fr/sites/strategie.gouv.fr/files/atoms/files/guide_methodologique_20160906web.pdf; Wildavsky (1979[19]), The Art and Craft of Policy Evaluation, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-349-04955-4; OECD (2020[20]), Improving Governance with Policy Evaluations, https://doi.org/10.1787/89b1577d-en.

An evaluation’s impact can also depend on its perceived quality, in terms of perception of transparency and lack of bias, as much as it can on its technical quality. For evaluations to be used, stakeholders and users must therefore trust their independence. For this reason, STRATA is particularly well placed to conduct evaluations and provide methodological advice on how to conduct quality evaluations in that it’s an institution at arm’s length of government, which is well respected for its technical skills. This function also builds on STRATA’s responsibilities related to the methodological quality of ex ante and ex post assessments, in that they require similar skills and resources.

On the other hand, operational monitoring requires important capacities, which can be defined as “the totality of the strengths and resources available within the machinery of government.” (OECD, 2008[21]). Monitoring requires, in particular, a critical mass of technically trained staff and managers (Zall, Ray and Rist, 2004[22]). These elements rest on the availability of dedicated resources, human and financial, for the monitoring function. For this reason, the lead responsibility for monitoring is with the Office of the Government and the Ministry of Finance. In fact, in other OECD countries with monitoring and delivery systems monitoring is driven from the centre (Canada, the United Kingdom or Australia see Box 4.2).

Finland

The Prime minister’s office (PMO) in Finland is in charge of monitoring the government programme. Specifically, the strategy unit in the PMO monitors the implementation of 5 key policy objectives of horizontal nature and wide structural reform of social and health care services that are part of Finland’s government-wide strategy. Together with the 26 key projects, the key policy areas are monitored weekly at the level of the CoG in government strategy sessions reserved for situation awareness and analysis based on evidence and foresight. Milestones for each policy area and project are clearly defined and indicators for each strategy target are updated two to four times a year.

Canada

The Results Delivery Unit of the Privy Council of Canada is a centre of government institution in Canada, providing support to the Prime Minister on public service delivery. It was created in 2015 to support efforts to monitor delivery, address implementation obstacles to key priorities and report on progress to the Prime Minister. The RDU also facilitates the work of government by developing tools, guidance and learning activities on implementing an outcome-focused approach. The results and delivery approach in Canada are based on three main activities: (i) defining programme and policy objectives clearly (i.e. what are we trying to achieve?); (ii) focusing increased resources on planning and implementation (i.e. how will we achieve our goals?); and (iii) systematically measuring progress toward these desired outcomes (i.e. are we achieving our desired results and how will we adjust if we are not?).

Source: Government of Canada (2018[23]), The Mandate Letter Tracker and the Results and Delivery approach, https://www.canada.ca/en/privy-council/services/results-delivery-unit.html#toc2 (accessed on 13 May 2020); (Government of Finland (n.d.[24]), Hallitusohjelman toimeenpano, https://valtioneuvosto.fi/hallitusohjelman-toteutus/karkihankkeiden-toimintasuunnitelma (accessed on 13 May 2020).

STRATA can act in analytical support capacity in some limited ways, to support the interpretation of structural changes and to perform strategic evaluations in the areas of the national progress plan, within the 10-year plan for evaluation. The nature of STRATA’s position, at arm’s length of the centre of government, and the skills of its staff members, are better suited for foresight, advice and evaluation. Clearly, the Office of the Government and the Ministry of Finance, which by definition are close to power, is best situated to take the lead on the monitoring of high-level priorities in terms of the practical aspects.

STRATA is a key advisory body of the government

Many OECD countries have set up a system of actors and institutions aimed at providing credible advice to government and at facilitating the capacity to implement reforms. Due to the pace of technological, environmental and cultural developments, policy makers are continuously called to find new solutions to complex issues. One way in which governments have sought to increase their strategic capacities is by relying on networks of actors, within and outside of government, that provide evidence and policy advice – the so-called policy advisory systems. Advisory systems contribute to wider evidence-based decision-making approaches in that they provide credible evidence to governments.

Within the evidence-informed decision-making system, advisory bodies can have the function of both evidence suppliers or knowledge brokers (OECD, 2017[25]). Policy advisory bodies can also be very diverse in terms of organisational structures, mandates or functions in the policy cycle (OECD, 2017[25]). Advisory bodies can take various forms, such as advisory councils, commissions of inquiry, foresight units, special advisors, think tanks and many other bodies, all of which provide knowledge and strategic advice to governments (Bressers, 2015[26]) (Blum and Schubert, 2013[27]).

Yet, advisory bodies often share common features. First, their responsibilities are tailored to their organisational structure and positioning within government. Specifically, advisory bodies situated at arm’s length of government, such as STRATA, focus their mandates on responsibilities, which require a high degree of autonomy, transparency and legitimacy, such as (OECD, 2017[25]):

Evaluations: To provide (ex post) reflections and evaluations.

Evidence: To provide information, expertise and facts to policy makers.

Strategic foresight: To provide new perspectives, strategic foresight and explorations of the future.

This is the case of France Stratégie, for example, the main advisory body in France attached to the Prime minister’s office, which focuses its mandate on foresight, ex post evaluations and managing a network of analytical bodies (see Box 4.3).

France Stratégie is an independent advisory body that replaced the General Planning Commission in 2013 and is attached to the Prime Minister’s Office. It has three main responsibilities:

Conducting foresight studies and related research that shed light on medium and long-term policy issues that fall within its fields of competence (economics, social policy, labour, employment and skills, sustainable development and digital technology).

Conducting ex post evaluations of public policies. France Stratégie evaluates the impact of public policies using rigorous methodologies and compares them to the expected results at the inception of the policy.

Managing a network of advisory bodies. As the main policy research engine of the government, France Stratégie manages the network of 8 other governmental advisory bodies (Council of Economic Analysis, Centre for foresight studies and international information (CEPII), Labour Market Council, Council for Retirement, High Council for the Future of Health Insurance (HCAAM), High Council of Environment (HCC), High Council for Family, Children and Ageing (HFCEA) and the High Council for the Financing of Social Protection).

France Stratégie has a staff of 40 experts (economists, sociologists, lawyers, engineers, and political scientists), 15 scientific advisers, and 20 support personnel. The institution is divided into 4 thematic units: economy, sustainable and digital development, labour employment and skills, society and social policies.

The autonomy of France Stratégie is guaranteed as it is solely responsible for its publications and communicates independently. It also aims to carry out its work in a non-partisan manner, in interaction with different political parties, unions as well as social and regional entities. Each year, France Stratégie defines its programme of work in accordance with policy priorities.

Source: France Stratégie (2021[28]), https://www.strategie.gouv.fr/ (accessed on 13 May 2021).

STRATA should focus on supplying evidence and evaluation, conducting strategic foresight and playing a methodological role in the greater EIPM system

In Lithuania, STRATA really stands out as the main cross-disciplinary advisory body available attached to the Centre of government. Moreover, STRATA through its independent nature and policy expertise could supply credible advice to the government that would enhance the evidence base of the government’s decision making and increase public trust.

In fact, since its creation, STRATA has already been recognised as a credible policy advisory body, and has received many requests for analysis by ministries. At the request of the Ministry of Interior, for instance, STRATA conducted an analysis of the effectiveness of the Lithuanian civil service and public sector in the international context, as well as on the effectiveness of the measures undertaken by the 17th Lithuanian government to improve the public sector (Ministry of Interior of the Republic of Lithuania and STRATA, 2020[29]). STRATA also developed projections on the supply and demand of healthcare specialists in Lithuania for the Ministry of Health (Jakštas et al., 2019[30]), as well as multiple economic pulse briefs on the economic situation related to the COVID-19 recession. The XVIIIth government’s programme implementation plan entrusted multiple tasks for STRATA in the area of national skill strategy, public sector innovations, strengthening capacities to conduct impact assessments among others (Government of Lithuania, 2021[31]).

For this reason, STRATA should refocus its mandate on advising state and municipal institutions on methodological issues related to evidence-informed decision making, as well on conducting “studies, evaluations and forecasts on strategic issues”, as mandated by article 30 of the law on government (Parliament of Lithuania, 1994[13]). This mandate would complement the quality control and assurance it provides in the area of ex ante and ex post regulatory assessment. On the other hand, as mentioned previously, STRATA is not best placed to conduct monitoring of the strategic governance system.

In practice, STRATA provides its advice in one of three ways:

Ministries and agencies can request STRATA to provide an analysis or conduct an evaluation by submitting their request to the Office of the Government (Parliament of Lithuania, 1994[13]).

The Office of the Government also can identify analytical priorities for the year.

Based on advice from STRATA’s board, the Office of Government then decides what evaluations and research will be conducted by the Centre each year in the annual activity plan. In this sense, STRATA’s functioning is close to that of Australia’s Productivity Commission (see Box 4.4), which also jointly decides on its work plan based on ministerial requests, priorities identified by the Prime Minister’s Office and self-initiated research. Indeed, while the Productivity Commission is independence by law, its work plan is largely defined by the government.

Australia’s Productivity Commission, located in the Government’s Treasury portfolio, is an independent government research and advisory body operating at arm’s length from the government. It produces research and policy recommendations in a wide range of economic, social and environmental issues. The Commission conducts studies both at the request of the government or through its own initiative. This self-initiated research is gathered under performance and annual reports. Moreover, the Productivity Commission acts as a secretariat for the inter-governmental review of government service provision.

Some of the main characteristics of the Commission include:

Independence: it operates under its own legislation, and its independence is formalised through the Productivity Commission Act. Moreover, it has its own budget allocation and permanent staff working at arm’s length from government agencies. Even if the Commission’s work programme is largely defined by the government, its results and advice are always derived from its own analyses.

Transparent processes: all advice, information and analysis produced and provided to the government is subject to public scrutiny through consultative forums and release of preliminary findings and draft reports.

Community-wide perspective: under its statutory guidelines, the commission is required to take a view that encompasses the interests of the entire Australian community rather than particular stakeholders.

The main products of the Productivity Commission are public inquiries and research studies requested by government. It also conducts performance monitoring and benchmarking, annual reporting on productivity, industry assistance and regulation. Furthermore, it can review competitive neutrality complaints.

The processes of governmental requests are well defined and each request comes with the terms of reference indicating the period of response so that enough time is allocated to conduct public inquiries. Generally, the period is from 9 to 12 months but can be shorter for more pressing issues.

Source: Productivity Commission (n.d.[32]), About the Commission, https://www.pc.gov.au/about (accessed on 13 May 2021).

STRATA’s role in managing a network of analytical competences is also crucial

In order to ensure the overall quality of evidence and its use, STRATA is responsible to create and manage a network of public sector competences, according to article 30 of the law on government (Parliament of Lithuania, 1994[13]). For this reason, STRATA is well placed to address the skills and capacity gap found in ministries and the centre of the government in regards to the supply and use of evidence. It could therefore take a leading role in nurturing a network of skilled analysts in co-operation with the Office of the Government, the Ministry of Finance and the Ministry of Interior, which retains overall competence for the civil service.

For instance, STRATA is well equipped to build partnerships with universities, to identify opportunities to establish master programmes in policy analysis and economics that are crucially needed to increase the supply in Lithuania, in co-operation with the Bank of Lithuania. As discussed in chapter 2, STRATA could partner with universities to develop a master’s degree to provide the Lithuanian civil service with a supply of quantitatively trained analysts.

Another way to promote analytical competencies in the public sector is for STRATA to foster and manage a network of analytical capacities across ministries and agencies. By giving seminars, sharing knowledge management and developing methodological guides for analysis and evaluation, STRATA could support the continuous development of public sector skills for evaluation. In doing so, STRATA could emulate what is done in Ireland with the Irish Government Economic Evaluation service, and its Internal Advisory Group across ministries in Ireland (OECD, 2020[33]) (see Box 4.5).

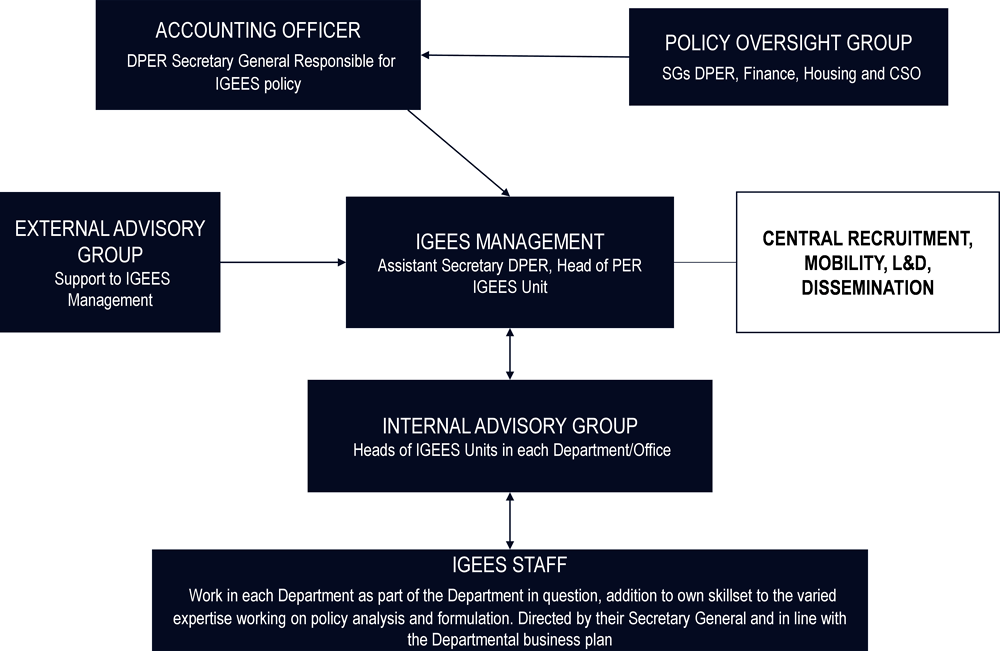

The Irish Government Economic and Evaluation Service (IGEES), situated in the Ministry of Finance, provides the government with policy and economic analysis, and manages a network of analysts. See Box 1.5 in Chapter 1 for more information on the service.

Since IGEES is a cross-governmental service with representatives in different governmental institutions, an Internal Advisory Group has been set up to co-ordinate the implementation of the IGEES strategy at the departmental level. The Internal Advisory Group is chaired by the head of IGEES at the Department of Public Expenditure and Reform and includes policy officers that represent their departments.

The group has an important role in co-ordinating daily activities of the IGEES scheme and managing its strategy implementation. Namely, it co-ordinates analytical capacity building and recruitment, mobility and Learning and Development Programme, production of analytical outputs and their dissemination through publication, events and awareness raising and championing the culture of evidence-informed policy making.

The development of the policy evaluation community is enhanced by the participation of the External Advisory Group in the co-ordination of the IGEES activities. The External Advisory group consists of stakeholders from universities and the wider research community. The full management scheme can be seen in the figure below.

In 2020 and 2021, STRATA witnessed some significant organisational changes However, more needs to be done to fully adapt its governance, organisation and resources to make the most of its new mandates and better respond to the government’s needs for cross-government analysis. Recently STRATA has adopted its new 2021-2025 strategy that should guide its transformation to fit its new broad mandate through the alignment of its organigramme and priorities (STRATA, 2020[34]).

The board of STRATA was created to help to plan the advisory activities of STRATA

One of the changes that STRATA underwent as part of its transformation from MOSTA in 2019 was the creation of the board, which consists of independent experts and one representative from the Government Office. The main function of the board is to set the vision of STRATA, to review its work and to advise on its annual activity plans, based on the needs expressed by Government. The new strategy of STRATA for 2021-2025 was adopted on 12 November 2020, and the new management structure was approved by the Office of the Government.

In order to provide credible and tailored advice, the composition of an advisory board or commission needs to ensure that membership is neutral; provides high-quality expertise; and, depending on the nature of the issues discussed, represents the age, gender, geographic, and cultural diversity of the community (Government of Canada, 2011[35]) (Quad Cities Community Foundation, 2018[36]).

OECD countries have ensured this neutrality, expertise and diversity in representation in a variety of different ways. For instance, in Norway, 40% of the board members of advisory bodies need to be women (OECD, 2017[25]). Similarly, Germany’s Federal Act on Appointment to Bodies ensures an equal representation of men and women (Government of Germany, 2015[37]). Box 4.6 provides a detailed discussion of how the Dutch Socio-Economic Council ensures the balance in the composition of its advisory group.

Dutch Socio-Economic Council

The Dutch Socio-Economic Council is a permanent policy advisory body established in 1950. The council is composed of 33 members from 3 different groups (11 per group): employers’ representatives, labour unions’ representatives and the so-called “Crown members” that are appointed by the government. The composition of this body reflects the varied interests of the Dutch society and, therefore, the advice of this tripartite council benefits from a high level of legitimacy.

Representation in Norwegian Official Committees

Norway has provisions that ensure that the composition of ad hoc advisory groups (“Norwegian Official Committees”) contains the representation of different personal characteristics (e.g. sex, age, ethnic background) as well as different political interests. Moreover, based on the opinions from these different groups or following public consultations, the committees are allowed to publish several distinct policy advice. This practice ensures the decision-making transparency and diverse representation.

Source: OECD (2017[25]), Survey on Policy Advisory Systems, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264283664-en.

In order to ensure neutrality, the boards of advisory bodies in most OECD countries are also subject to rules regarding conflicts of interests, acceptance of gifts, as well as the disclosure of contacts with interest groups and lobbyists (OECD, 2017[25]). Another important element of neutrality is transparency in decision making. Transparency is an important element to ensure that decisions and advice are based on evidence.

The composition of the STRATA board is already an important marker of the credibility of its advice, and by extent, the legitimacy of its decision making – for instance regarding the identification of analytical priorities through the development of its annual activity plan. The board should be able to issue its formal opinion on the activity plans of STRATA and help to align the needs of the government with the most optimal activity planning for STRATA, particularly as the Office of Government is part of the board. However, the last word on annual activities may still be given by the Office of the Government given that the more operational management issues are governed by the board in a collegial way. In addition, all senior executives related to STRATA should be subject to clear provisions related to conflict of interest, which should be publicly available on STRATA’s website. Apparently, senior managers within STRATA are subject to such provisions with official declarations according to the Law of 1997 of Adjustment of Public and Private Interests in the Public Service and these are checked by the Chief Official Ethics Commission. However, the results are not public and do not apply to members of the board. For example, in Australia, the Productivity Commission obliges its commissioners to declare their potential conflict of interests to its chair and the government but these are not public. In France, heads and boards of public institutions are subject to the law on the Transparency of Public Life and the scrutiny of a special authority, which forces a standard declaration concerning all aspects of conflicts of interest, which is checked by a special supervisory authority and is made public for elected public officials only.

Australia

In Australia, Section 29 of the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act of 2013 prescribes the disclosure of interest that can give a raise to material conflict as part of duties of public officials. Nevertheless, there is no standard list of items to be disclosed across the whole public sector and individual public institutions may have different disclosure rules and procedures.

Commissioners of the Australian Productivity Commission must make their conflict of interest declaration available to the government but they do not have to be made public. Section 43 of Australia Productivity Commission Act of 1998 stipulates that any “member of the Commission” (i.e. commissioner or deputy commissioner) must disclose to the chair any pecuniary or other interest that may “conflict with the proper performance of his or her functions as a member”. In turn, the chair has an obligation to report in writing the conflicting interests of his-own and those of the members of the Commission to the government. Moreover, any potential conflicting interests have to be reported either in the reports that were drafted with the participation of the Commission’s member in question or otherwise reported to the body to whom the function was conducted.

Finally, the Productivity Commission keeps an online registry of gifts and benefits (accessible on the commission’s website) received by the commissioners and staff members as well as the organisation presenting the gift and their estimated value.

France

In 2013, the French parliament ratified a Law on the Transparency of Public Life (loi relative à la transparence de la vie publique), which stipulated that all elected officials, senior civil servants and nominated heads of public institutions (including public enterprises) must declare their wealth and external revenue sources to the High Authority for Transparency in Public Life within 2 months following the nomination. These public officials have to declare the following items: all paid activities exercised within 5 years before the nomination to the public position, as well as the paid positions held while at the public office, remunerated consultancy activities during and 5 years prior to the nomination to the public office, financial participation in companies and shareholding; and professional activities of the marital partner among others.

Source: Australian Government Productivity Commission (n.d.) Governance, https://www.pc.gov.au/about/governance; OECD (2003), Managing Conflict of Interest in the Public Service; National Assembly of the French Republic (2003), Loi Relatif à la Transparence de la Vie Publique, https://www.legifrance.gouv.fr/loda/id/JORFTEXT000028056315.

The organisational structure has recently been adapted but capacities of STRATA have not changed significantly since its previous mandate as MOSTA

With the adoption of the 2021 - 2025 Government Strategic Analysis Centre transformation plan (STRATA, 2020[34]), STRATA attempted to realign its organisational structure with its new mandate.

Prior to the reorganisation, the Centre was structured in four thematic units, three of which were directly related to the old MOSTA mandate, while only one (the strategic competencies unit) reflected the broader mandate across the government (see Figure 4.2).

Therefore, most of the analysts were working in the units concentrating on the delivery of the old thematic mandate of MOSTA. Indeed, of the 37 analysts working in STRATA in 2020 (STRATA, 2020[38]):

In 2020, STRATA’s team still included the following 25 analysts who worked on issues related to the old MOSTA mandate:

STRATA also employed 10 analysts who worked in other fields, in particular related to the Centre’s new responsibilities related to impact assessment:

STRATA also had 3 data engineers, and a couple staff members who worked on internal and external communication.

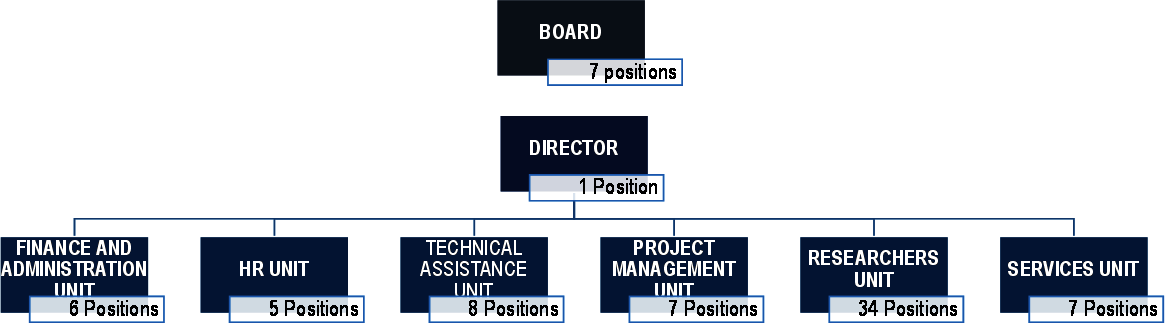

After the organisational transformation (see Box 4.9 below), the analysts were re-organised into one Researchers unit that currently includes 28 researchers concentrating on the fields of:

According to the transformation plan, this unit should be expanded to include a total of 34 researchers.

Source: STRATA (2020[38]), Government Strategic Analysis Centre: Mission and Direction of Activities, July 2020, Power Point; STRATA (2021[39]), Board Meeting Nr. 10: 2021 January 29, PowerPoint Presentation; (STRATA, n.d), STRATA’s website, https://strata.gov.lt (accessed on 27 May 2021).

On January 29th 2021, the new structure of STRATA was amended to better reflect the new mandate of this whole-of-government strategic analysis centre and to dismantle the previous units with a narrow thematic focus. Nevertheless, further capacities should be added to accommodate the extensive mandate of STRATA in the EIPM system and the appropriateness of the new organisational structure still needs to be tested in practice and will take time to show results. On the other hand, transferring some expertise back to the Ministry of Education, Science and Sport would not only further recalibrate the competences of STRATA to reflect better its new mandate, but it would also help to create space for the new functions.

On January 29th 2021, the Office of the Government approved STRATA’s new organisational structure. Instead of the thematic division of units, the new structure will feature the functional units. According to this plan, there will be a Services Group (7 people), Researchers Group (34 people), Project Management Group (7 people), Technical Assistance Group (8 people), Human Resources group (5 people), Administrative and Finance Group (6 people).

The Researchers Unit is further subdivided into 4 different groups: Economic Analysis Group (currently 4 people), Quantitative Research Unit (currently 11 people), Qualitative Research and Strategic Foresight Group (currently 8 people), PolicyLab: Design and Behavioural Research Group (5 people).

Source: STRATA (2021[39]), Board Meeting Nr. 10: 2021 January 29, PowerPoint Presentation.

The 2021-2025 strategy developed together with the board in January 2021 aims at making STRATA the main institution in charge of promoting evidence-informed decision making across government. Some of the new key performance indicators for STRATA include the share of legal acts accompanied by high-quality RIAs and the share of recommendations and insights used in decision making (STRATA, 2020[34]). The implementation of this medium-term transformation plan will be essential for STRATA to fulfil its new ambitious mandate.

The current STRATA’s funding mix is currently not in line with its new mandate

The current STRATA mandate is highly dependent on funding received from the European Union, and specifically project-based, funding. Indeed, currently around 73% of STRATA’s funding comes from projects. Most of these projects are due to end at the end of 2022 (STRATA, 2020[38]). While project-based funding ensures independence and additional capacities to STRATA, policy advisory bodies also need some stable funding to:

maintain the independence and credibility of their advice (OECD, 2017[25])

remain flexible and agile in responding to the government’s needs, as STRATA has shown it is capable of doing through the COVID-19 pulse reports (STRATA, 2020[40]).

Therefore, there is a need to adjust resources of STRATA, and provide the centre with some core resources commensurate with its responsibilities at least over a 4 to 5 year cycle, that could be then subject to performance assessment and review. STRATA has a distinct budget line within the budget of the Office of the Government. Additional funding from EU projects as well as ministries could supplement the core financial resources and increase the autonomy and expertise of STRATA. STRATA should report annually on its total financial expenditures and project management.

Refocus and clarify STRATA’s mandate

STRATA’s mandate needs to be refocused clarified in order to focus its responsibilities on tasks that require a high degree of autonomy and expertise. To this extent, the Lithuanian government should:

Focus STRATA’s responsibility in regards to monitoring the implementation of the National Progress Plan to analytical support to the office of the government.

Clarify STRATA’s role in the RIA process. For instance, STRATA could:

Serve as a general focal point for Ministries’ analytical units to help promote good practices, methodological tools and skills in evaluation, impact assessment and analysis, as part of a strategy to promote better regulation, to facilitate high-quality impact assessment, to strengthen a process of reviewing the fitness of the existing stock of regulation. Give a formal role to STRATA in the area of ex post evaluation. In particular, STRATA could:

Develop general guidelines for ex post evaluation in co-operation with Central project management agency and Supreme Audit Institution.

Conduct high-profile cross-sectoral evaluations and analyses.

Engage with a community of evaluators across ministries, sharing methods, organising seminars and peer review of the work.

STRATA should help address the analytical capacity gaps within Lithuanian public sector through:

The creation of a tailored academic master’s programme in economics and quantitative policy analysis in co-operation with universities to increase the supply.

Managing the annual recruitment and the selection of a set of professional analysts for the government. After validation by STRATA, these analysts would be dispatched across government by a decision of the Office of the Government and the Ministry of Finance, to serve the strategic needs of the Centre of Government. Some of these analysts could also work at STRATA, the Office of Government and the Ministry of Finance, of course, but this should not be exclusively the case.

Promoting a culture of evidence-informed policy making among the network of analytical units in the ministries and agencies, which can be characterised as knowledge brokers.

Organising seminars that could be opened both to government analysts as well as other researchers working in the academia, NGOs or the private sector, publishing a series of government working papers, and supporting the effort of the Government, including the Prime Minister and the Chancellor, to increase awareness to the analytical work undertaken by the government to inform policy choices and to promote an Evidence-Informed Approach for policy making.

Strengthen STRATA’s operations

There is a need for the Government to strengthen STRATA’s operations through the following actions:

Supporting the implementation of STRATA’s ambitious and forward-looking strategy for 2021-25, while monitoring progress. The goal is to facilitate an adaptation of STRATA’s governance and organisational structure in line with the new functions so that they match its new mandate. This includes recalibrating STRATA’s human resources and expertise to better reflect the new mandates.

Strengthen the credibility and integrity of STRATA’s advice. While the Office of the Government may be approving the programme of STRATA’s activities following the formal advice from the board, the board should be responsible for the issues regarding strategic development. Integrity should be strenghtened by introducing provisions for conflict of interest for STRATA’s board members.

Provide STRATA with an appropriate funding mix, including core public funding, complemented by project-based financing. The goal is to ensure that government core priorities can be met in the longer term, while preserving incentives for dynamic management.

References

[27] Blum, S. and K. Schubert (2013), Policy analysis in Germany, Policy Press.

[26] Bressers, D. (2015), Strengthening (the institutional setting of) strategic advice: (Re)designing advisory systems to improve policy performance. Research on the practices and experiences from OECD Countries.

[28] France Stratégie (2021), strategie.gouv.fr.

[18] France Stratégie (2016), How to evaluate the impact of public policies: A guide for the use of decision makers and practitioners (Comment évaluer l’impact des politiques publiques : un guide à l’usage des décideurs et des praticiens), https://www.strategie.gouv.fr/sites/strategie.gouv.fr/files/atoms/files/guide_methodologique_20160906web.pdf (accessed on 13 May 2021).

[23] Government of Canada (2018), The Mandate Letter Tracker and the Results and Delivery approach, https://www.canada.ca/en/privy-council/services/results-delivery-unit.html#toc2 (accessed on 13 May 2021).

[35] Government of Canada (2011), Health Canada Policy on External Advisory Bodies, https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/corporate/about-health-canada/public-engagement/resource-centre/policy-external-advisory-bodies-health-canada-2011.html#a2.3 (accessed on 6 November 2019).

[24] Government of Finland (n.d.), Hallitusohjelman toimeenpano, https://valtioneuvosto.fi/hallitusohjelman-toteutus/karkihankkeiden-toimintasuunnitelma (accessed on 13 May 2021).

[37] Government of Germany (2015), “Federal Act on Appointment to Bodies of 24 April 2015, http://www.gesetze-im-internet.de/englisch_bgrembg/englisch_bgrembg.pdf (accessed on 13 May 2021).

[31] Government of Lithuania (2021), Aštuonioliktosios Lietuvos Respublikos Vyriausybės programos nuostatū įgyvendinimo planas Nr. 21-20649 (The Implementation Plan of the 18th Government of the Republic of Lithuania), https://lrv.lt/uploads/main/documents/files/VPN%C4%AEP%20projektas.pdf (accessed on 27 May 2021).

[15] Government of Lithuania (2021), Ex-post Vertinimo metodologija (Ex-post Evaluation Methodology).

[11] Government of Lithuania (2021), Galima didesnio poveikio teisės aktų projektai, jų poveikio vertinimo atlikimo ir viešūjų konsultacijų vykdymo terminai (Higher Legislation Projects, their Regulatory Impact Assessments’ and Public Consultations’ Schedule), https://lrv.lt/uploads/main/documents/files/Apie_vyriausybe/geresnis%20reguliavimas/2021-2024%20m_%20Didesnio%20poveikio%20projektai_%20PV%20ir%20konsultaciju%20terminai_2.pdf (accessed on 21 June 2021).

[4] Government of Lithuania (2021), Strateginio Valdymo Metodika (Strategic Governance Methodology), https://e-seimas.lrs.lt/portal/legalAct/lt/TAD/5a6f68c4a8e511eb98ccba226c8a14d7?positionInSearchResults=0&searchModelUUID=ec7e06f0-8ee4-4478-a94c-1510659cba79 (accessed on 12 May 2021).

[3] Government of Lithuania (2020), Nutarimas Nr. 998 dėl 2021-2030 metų nacionalinio pažangos plano patviritnimo (Resolution Nr.998 on the Approval of the National Progress Plan for 2021-2030), https://e-seimas.lrs.lt/portal/legalAct/lt/TAD/c1259440f7dd11eab72ddb4a109da1b5?jfwid=32wf90sn (accessed on 13 May 2021).

[30] Jakštas, G. et al. (2019), Medicinos darbuotojų poreikio prognozavimo modelis: rezultatai ir išvados (Forecast model for medical staff demand: results and conclusions), MOSTA, Vilnius, Lithuania.

[29] Ministry of Interior of the Republic of Lithuania, M. and STRATA (2020), Viešojo Sektoriaus Ataskaita (Public Sector Report), Ministry of Interior of the Republic of Lithuania, Vilnius, Lithuania.

[20] OECD (2020), Improving Governance with Policy Evaluation Lessons From Country Experiences, OECD Public Governance Reviews, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/89b1577d-en.

[33] OECD (2020), The Irish Government Economic and Evaluation Services: Using Evidence-Informed Policy Making to Improve Performance, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/cdda3cb0-en.

[25] OECD (2017), Policy Advisory Systems: Supporting Good Governance and Sound Public Decision Making, OECD Publishing, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264283664-en.

[41] OECD (2008), “Ireland, Towards an Integrated Public Service”, https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/docserver/9789264043268-en.pdf?expires=1568115320&id=id&accname=ocid84004878&checksum=22A4C83734AC673029BF03301D6EF162 (accessed on 10 September 2019).

[21] OECD (2008), OECD Public Management Reviews: Ireland 2008: Towards an Integrated Public Service, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264043268-en.

[2] Parliament of Lithuania (2020), Strateginio valdymo įstatymas (Law on Strategic Governance).

[1] Parliament of Lithuania (2020), Strateginio valdymo įstatymas Nr. XIII-3096 (Law on Strategic Governance).

[8] Parliament of Lithuania (2018), Lietuvos Respublikos Technologijų ir Inovacijų Įstatymas (Law on Technology and Innovation).

[5] Parliament of Lithuania (2016), Lietuvos respublikos užimtumo įstatymas (Law of Employment of the Republic of Lithuania).

[7] Parliament of Lithuania (2009), Lietuvos respublikos mokslo ir studijų įstatymas (Law on Higher Education and Research of the Republic of Lithuania).

[6] Parliament of Lithuania (1997), Lietuvos Respublikos Profesinio Mokymo Įstatymas (Law on Vocational Training of the Republic of Lithuania).

[13] Parliament of Lithuania (1994), Lietuvos respublikos vyriausybės įstatymas (Law on the Governmen of the Republic of Lithuania).

[17] Piccioto, J. (2013), “Evaluation Independence in Organizations”, Journal of MultiDisciplinary Evaluation, Vol. 9/20, p. 15.

[10] Prime Minister’s Office (2020), Ministro pirmininko nota dėl numatomo teisinio reguliavimo poveikio vertinimo kokybės gerinimo (Note of the Prime Minister on the RIA Quality Improvement).

[32] Productivity Commission (n.d.), About the Commission, https://www.pc.gov.au/about (accessed on 28 May 2021).

[36] Quad Cities Community Foundation (2018), Advisory Board: Best Practices and Responsibilities, https://www.qccommunityfoundation.org/advisoryboardbestpracticesandresponsibilities (accessed on 5 November 2019).

[9] STRATA (2021), 2020-2021 Projektai ir Tyrimai: Analitika Įžvalgiems Sprendimama (Projects and Studies in 2020-2021: Analytics for Insightful Decisions), https://strata.gov.lt/images/leidiniai/analitika-valdymo-sprendimams-2020-2021.pdf (accessed on 25 June 2021).

[39] STRATA (2021), Board Meeting Nr. 10: 2021 January 29.

[14] STRATA (2020), Ateities ekonomikos DNR plano pirminė analizė (DNA of the Future Economy: ex-ante analysis), STRATA, Vilnius, Lithuania, https://strata.gov.lt/images/tyrimai/2020-metai/geresnis-valdymas/20200518-Ateities-ekonomikos-DNR-plano-analiz%C4%97.pdf (accessed on 22 June 2021).

[40] STRATA (2020), Kasdieninis ekonomikos būklės pokytis (Daily Economic Situation Change) May 6th, 2020, STRATA, Vilnius, Lithuania.

[12] STRATA (2020), Numatomo Teisinio Reguliavimo Poveikio Vertinimas (Ex ante Regulatory Impact Assessment).

[38] STRATA (2020), STRATA mission and directions.

[34] STRATA (2020), Strategija 2021-2025 (Strategy 2021-2025), STRATA, Vilnius.

[16] Vaessen, J. (2018), Five ways to think about quality in evaluation, https://ieg.worldbankgroup.org/blog/five-ways-think-about-quality-evaluation (accessed on 13 May 2021).

[19] Wildavsky, A. (1979), The Art and Craft of Policy Evaluation, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-349-04955-4.

[22] Zall, J., K. Ray and C. Rist (2004), Ten Steps to a Results-Based Monitoring and Evaluation System, The World Bank, https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/bitstream/handle/10986/14926/296720PAPER0100steps.pdf?sequence=1 (accessed on 22 August 2019).