3. Key skills for innovative leaders in Brazil’s federal administration

This chapter maps the evolution of public sector leadership competencies, arguing that the call for public sector innovation requires leadership that is not only transformational, but also horizontal and distributed. It then presents the concept of leadership competency frameworks, illustrated by various examples used in many OECD countries. It then identifies the types of skills, mindsets and behaviours that leaders need to support innovation in the Brazilian context, based on insights from public servants and in the federal administration.

Chapter 1 built a case for the need to ensure high-quality leadership in Brazil to support a more productive, effective and innovative public service. Innovation cannot be successful without support from public leaders with the right skills, competencies and styles. Effective leaders mobilise and engage staff to promote desired outcomes, and ensure that employees have the right resources and opportunities to use their skills and drive positive change in their organisations.

The OECD survey presented in Chapter 2 finds a public service in Brazil that has some of the skills necessary to innovate, yet, innovation is not happening at the level needed or expected. The concurrent Innovation Systems review conducted by the OECD’s Observatory for Public Sector Innovation (OPSI) mirrors these findings (OECD 2019). The challenge for Brazil’s public leaders is to find ways of activating the full potential of the innovative talent that resides within their organisations. In the OECD’s discussions with Brazilian civil servants, leadership was one of the most cited reasons for both success and failure of innovation. The ability of senior civil servants to lead and drive innovation is therefore a strong determinant of successful innovation in Brazil. This chapter identifies leaders’ competencies for innovation by highlighting the characteristics of successful public sector leaders in a Brazilian context.

Evolution of the public sector leader

In the public sector, the practice of studying, defining and attempting to replicate good leadership was formalised in the 1980s and 1990s through competency-based leadership. Over the past 20 years, there has been an evolution in the understanding and expectation of public sector leadership, reflected in the competency models of senior civil service (SCS) systems in many OECD countries. While a “tough-talking, take-charge, individualistic view of public leadership is alive and well through the world” (Crosby and Bryson, 2018), there is growing evidence and academic rigour that identifies necessary alternatives to “heroic” models of public leadership. These alternatives recognise that public sector innovation cannot be successful if it is singularly driven or controlled by one leader from the top. Rather, these models focus on groups of leaders, both hierarchical and situational, that can successfully drive innovation together.

Sometimes called “adaptive”, “pragmatic” or “distributed” leadership, these models emphasise an “anti-hero” form of leadership. An anti-hero adapts his/her leadership style according to circumstances. Anti-hero leaders are aware of the limitations of their own knowledge and skills and build expertise among their followers, which they can rely on to complement their own expertise. This suggests that a leader in the context of public sector innovation should have a lower perception of their own innovation skills than those of the workforce they build around them, rather than the other way around, as appears to be the case in Brazil’s federal administration (see Chapter 2). The five pillars of anti-heroic leadership – empathy, humility, flexibility, acknowledgement of uncertainty and self-awareness – are helpful for thinking about the leadership styles necessary to build and support innovation capabilities within public sector organisations (Wilson, 2013).

Despite great interest among academics and public sector practitioners, the practise of distributed leadership in the public sector is quite nascent. Early in their adoption, distributed leadership models described the complex governance environments where true change requires co-ordinated leadership across multiple organisations which are not hierarchically organised. However, these are often difficult to implement within public sector organisations as they are not well aligned with traditional public sector hierarchies and accountably structures. These traditional heroic models are reinforced by oversight and audit organisations which enforce the traditional and current public sector accountability models, which view accountability as an individual activity, generally concentrated at the top.

A related strand of the public sector leadership debate revolves around values-based and ethical leadership. Values-driven culture and leadership is the first pillar of the OECD Recommendation of the Council on Public Sector Leadership and Capability. Values guide the judgement of public servants, including leaders, on how to perform their tasks in daily operations. The Recommendation acknowledges that specific values vary across countries, but common values include accountability, integrity, the rule of law and serving in the public interest.

Values-based leaders usually display a high degree of self-awareness, and are able to draw on and leverage the values of their colleagues as a motivating factor for both themselves and their teams. These values are ideally articulated in a structured way and used to guide decision making. Values-based leadership relates to two interconnected elements – a leaders’ own values, which they understand and use to make effective decisions – and a leaders’ ability to promote values in their workplace and inspire values-based behaviour among their followers (Treviño, Hartman and Brown, 2000).

Public sector leadership competency models

Leadership competencies are clear statements about the skills and behaviours that a government expects from its leadership cadre. When integrated into human resources processes, they become powerful strategic tools to guide decisions about leadership appointments, development, performance and accountability. Some OECD countries have actively used leadership competencies for decades, and they are now actively used in most OECD countries, as shown in Figure 3.1 (OECD, 2016).

The United States, whose senior leadership contains a mix of politically appointed and career civil servants, has developed a model with “five executive core qualifications”1:

Leading change: The ability to bring about strategic change, both within and outside the organisational goals. The ability to establish an organisational vision and to implement it in a continuously changing environment.

-

Leading people: The ability to lead people toward meeting the organisation’s vision, mission and goals. The ability to provide an inclusive workplace that fosters the development of others, facilitates co-operation and teamwork, and supports constructive resolution of conflicts.

-

Results driven: The ability to meet organisational goals and customer expectations. The ability to take decisions that produce high-quality results by applying technical knowledge, analysing problems and calculating risks.

-

Business acumen: the ability to manage human, financial and information resources strategically.

-

Building coalitions: The ability to build coalitions internally (i.e. intra- and inter-ministerial partnerships) and with other federal agencies, state and local governments, non-profit and private sector organisations, foreign governments, or international organisations to achieve common goals.

Additionally, each of the core qualifications has sub-components2 to provide greater clarity and nuance to the qualifications. This framework is used during hiring, selection and evaluation of both politically appointed and career senior leadership positions other than heads of agencies, who are vetted and approved by Congress.

In 2017, Estonia released its new leadership competency model, made up of six core competencies for leaders, specifically referencing innovation, designing for the future, achieving results and empowering others. “The 2017 competence model for the top civil service describes a leader who is a bold designer of the future, an achiever, an inspiring driver of innovation, a genuine value builder for target groups and an effective self-leader.”3

Chile also uses leadership competencies (Figure 3.3). Its Senior Executive Service System comprises 1 557 positions, or approximately 30% of the workforce, in the central government. Created in 2003, the Senior Executive Service System was developed to create a process of modernisation and transparency based around merit-based hiring decisions and open competition.

By developing and using profiles that focus on principles and values, attributes, and results as well as using an open merit-based process, the Chilean government received an average of 117 applications per position in 2017. As a result of moving to a profile-based recruitment system, Chile now has 28% of managers from the private sector, 29% are women (previously women comprised only 23.5%), and a strong cadre of future leaders that can use the profile to focus on specific training and experiences.

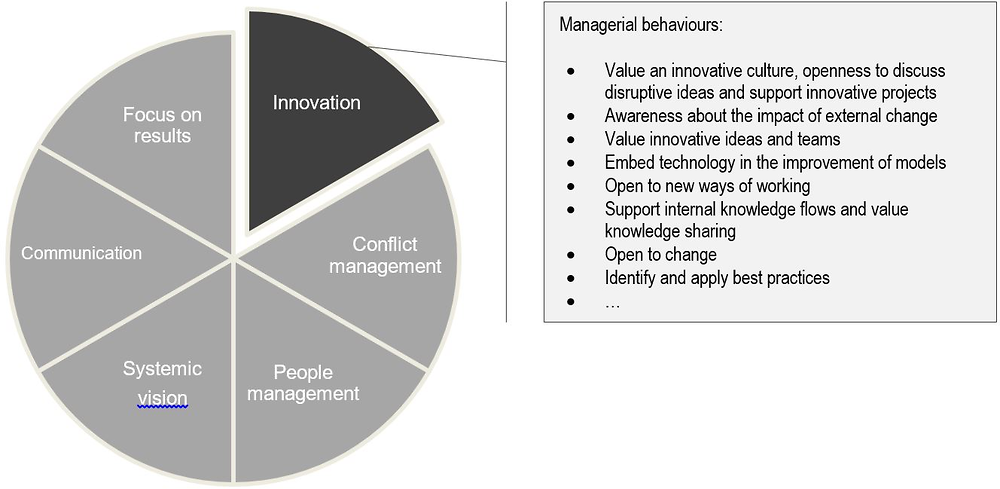

In Brazil, competencies for senior leaders have been at the heart of discussions about the quality of public management, within and outside the federal administration. The civil society organisation Vetor Brasil uses a competency-based approach to help municipalities and states recruit their leaders (see Chapter 5). Civil society stakeholders are also reflecting on the opportunities and challenges of applying competency-based approaches to the recruitment and development of public managers. Discussions at the Instituto República’s 3rd Annual Conference on Challenges for the Public Sector (2018) highlighted the need to map skills and skills gaps, which tend to happen when people assume new positions, particularly management (Instituto República, 2018). The Dom Cabral Foundation has also developed a competency model for public managers (mapa das competências gerenciais), which looks at innovation skills needed from a strategic perspective, specific for senior managers, middle managers and line managers (Figure 3.4) (Fundação Dom Cabral 2018).

Innovative leadership competencies for Brazil’s federal administration

As the Brazilian public sector continues to focus on driving results and public value for the country, it aims ensure sustainability through a strong, robust and flexible leadership cadre and pipeline of future leaders. One strategy to improve the development, hiring and assessment of current and future leaders is by identifying a group of competencies that reflects the skills needed to innovate in the public sector today and succeed in the future.

The National School of Public Administration (Escola nacional de administração pública, ENAP) was one of the first public sector institutions in Brazil to create a leadership competency model that includes innovation as a core competency.

The competencies discussed below and shown in Figure 3.6 are built on the foundation of ENAP’s model and input from Brazilian civil servants involved in innovation provided during the course of the OECD’s interviews and workshops. They are also built upon good practices around the world and leading literature on public sector leadership. These competencies can be taken into consideration alongside existing competency frameworks in Brazil in order to develop a framework tailored to the context of the Brazilian public sector.

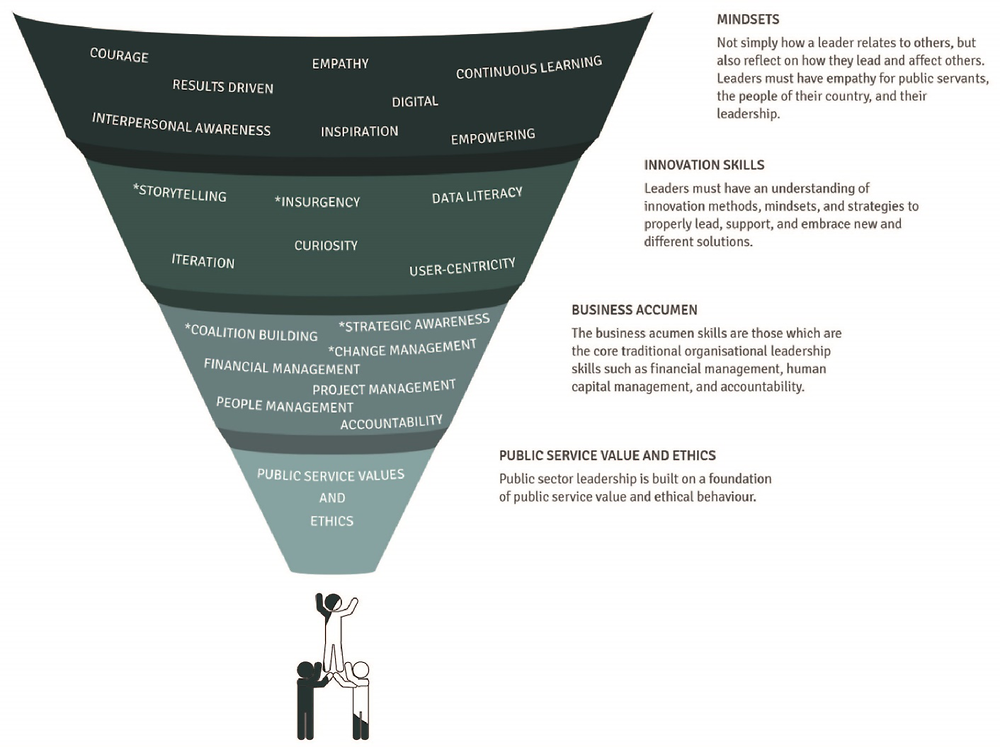

The competencies above are divided into three distinct, but interconnected groups: 1) innovation skills; 2) business acumen; and 3) mindsets; sitting on a foundation of ethics and public service values which guide decision making towards the public interest. Building on this foundation, leadership needs business acumen competencies to manage the business of their department, recognising that these competencies often differ in specific and important ways between the private and public sectors, and even among different public sector organisations. Moving to the next section, leaders need at least a solid understanding of the six innovation skills areas presented in Chapter 1 and measured in Chapter 2. Lastly the effectiveness of a leader and the ability to harness a leader’s and an organisation’s competencies is dependent on the mental approach, or mindsets, of the leader.

Certain competencies in the business acumen and innovation section have been marked with an asterisk (*). This is to denote that, as a baseline, leaders should have stronger knowledge of and experience with these skills. To help define a leader’s ability within each competency, the model views skills on a continuum:

-

1. aware: general understanding of the practice and how it applies to leading the public sector

-

2. capable: being able to use the skill and understanding its application

-

3. Specialised: adopting these skills in the leader’s day-to-day use and applying them in a more strategic and systematic way.

An individual leader should not be expected to be an expert in each competency, as doing so would reinforce the hero view of leadership and set unrealistic expectations that would disqualify strong potential candidates. Rather, a nuanced view of competencies should be job-specific to allow for flexibility while also ensuring that minimally, leaders are “aware” in each competency and “capable” in the most critical competency areas. For example, a chief information officer vacancy will likely require a “specialised” rating in skills such as iteration and digital.

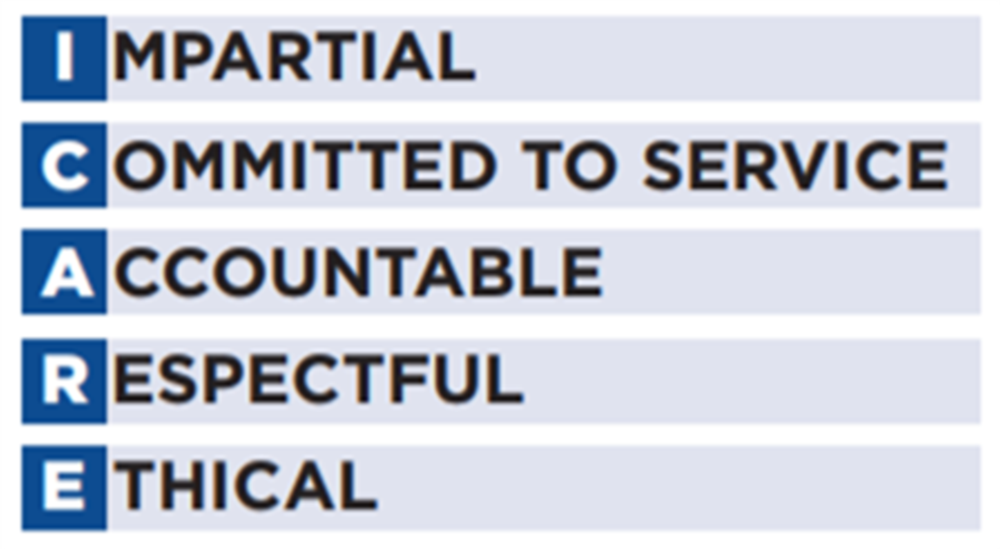

Ethics and public service values

Values and ethics exist as a social contract between the government and citizens. As the Brazilian public sector continues to focus on rooting out corruption, there is a clear need to make ethics and values explicit within any competency model. This can be done by framing ethical considerations in a clearly articulated set of public service values. While such values may vary by country, commonly stated values in OECD countries’ public services include accountability, impartiality, the rule of law, integrity, transparency, equality and inclusiveness.

Research on ethical leadership suggests that there are two important aspects to ethical leadership (Treviño, Hartman and Brown, 2000). First, the leader should be ethical themselves – this means they have a clear understanding of their values and those of their organisation, and they use these to guide their decision-making processes. Second, they need skills to impart ethical decision making down throughout the organisation they lead. This implies that they need be seen by others as taking values-based decisions, and they need to support others to follow these values when taking their own decisions. This suggests a need to ensure distributed leadership, relying on common values to guide the collective rather than a specific individual. This should therefore improve the collective ethical actions of the group (Van Wart, 2011).

Another finding from the ethical leadership literature is that developing values-based leadership is a long-term goal rather than a competency that is easily learnt. Recent research suggests that ethical leadership does not start once one is a leader. Rather, the primary influence on the ethics of leaders is their own managers and leaders during the early stages of their career (Brown and Treviño, 2006). As such, developing values-based leadership and organisational culture is never finished. This is why the first pillar of the OECD’s 2019 Recommendation of the Council on Public Service Leadership and Capability calls for values-driven culture and leadership in the public service, centred on improving outcomes for society.

Brazil has a number of recent documents on ethics and values that have shaped some of the current discourse around leadership, innovation and change in the public sector. In 1994, Decree No. 1171 – Professional Ethics of the Public Civil Servant of the Federal Executive Branch – was put into law (Casa Civil, 1994). The decree outlined 15 pieces of deontological ethical guidance. The last two pieces of guidance made explicit the core functions and prohibitions of public servants, liking ethical behaviour to efficient service provision. In 2007, Decree No. 6029 formalised and centralised the review of ethical standards by creating a Public Ethics Commission.

The first pillar of the OECD Recommendation of the Council on Public Service Leadership and Capability calls for a values-driven culture and leadership in the public service, centred on improving outcomes for society. In the context of this Recommendation, “values” refers to core organisational values that guide the judgement of public servants in how to perform their tasks in daily operations. While such values may vary by system, commonly stated core public values include accountability, impartiality, the rule of law, integrity, transparency, equality and inclusiveness. The first principle of this Recommendation is that countries:

Define the values of the public service and promote values-based decision making, in particular through:

-

1. clarifying and communicating the shared fundamental values which should guide decision making in the public service

-

2. demonstrating accountability and commitment to such values through behaviour and

-

3. providing regular opportunities for all public servants to have frank discussions about values, their application in practice and the systems in place to support values-based decision making.

Source: OECD (2019b), Recommendation of the Council on Public Service Leadership and Capability, https://legalinstruments.oecd.org/en/instruments/OECD-LEGAL-0445 (accessed 4 April 2019).

During the OECD’s discussions with innovators and leaders conducted as part of this review, the OECD observed that most conversations around ethics focused on prohibitive actions and compliance, rather than on the ethical principles themselves. This narrative centred on explicit expectations and prohibitive activities, results in a heightened sense of risk and an immediate concern of protecting an individual’s career by avoiding many of the ambiguities that can stem from the intersection of laws, values and ethics. The guiding principles of conduct appear to be increasingly compliance and fear-based rather than motivational and values-based. When personal protection takes precedent over proactively serving society, the civil service often resorts to retrenchment to protect the status quo without recognition that the status quo can also be doing harm. This situation appears to be reinforced by the career system (see Chapter 2), which many suggest creates a competition that prioritises the status quo.

In order for a foundation of values and ethics to shape the culture for both leaders and civil servants, the focus of work needs to shift towards citizen interests. When the system skews towards heavy punishment, ambiguity can cause inaction.

In 1999, Australia developed a Code of Conduct as part of the Public Service Act. This Code of Conduct set forth basic requirements and expectations of employees. Additionally, the Public Service Act also developed the “APS Values” as additional mandatory standards of behaviour.

In the Australian Public Service Commission’s State of the Service Report 2017-18, an ethical review of employees potentially in breach of these mandatory standards occurred with 569 employees – or the equivalent of 0.4% of the civil service – a three-year low.

Just as interesting, the Australian Public Service Commission also uses the report to look at how well the values are being implemented and influencing the culture of the Australian Public Service.

Source: Australian Public Service Commission (2018), State of the Service Report 2017-18, https://www.apsc.gov.au/sites/default/files/18583_-_apsc_-_sosr_-_web.pdf

Business acumen

The business acumen competencies are traditional organisational management competencies such as financial management, people management and accountability.

Within this area, three critical competencies require greater focus and experience: 1) change management; 2) strategic awareness/political savvy; and 3) coalition building. As discussed in Chapter 1, guiding an organisation through change is a key requirement of modern public sector leadership. Leaders must be able to be flexible, adapt and guide organisations through ambiguity and complexity.

To manage change, leaders must also have a strong grasp of the political environment within both their organisation and the system-at-large. This also requires building coalitions and moving from an organisational perspective to a systems perspective (Crosby and Bryson, 2018). Therefore, achieving results is not an individual activity, but a collaborative process leading to shared outcomes among agencies and sectors, and greater democratic accountability to ensure responsiveness and inclusiveness (Van Wart, 2013).

In OECD workshops with public servants, there appeared to be agreement that the business acumen competencies of senior management are the strongest of the three included in the model. Because these are more tangible and better understood, management training is often dedicated to these competencies and promotion opportunities stem from one’s ability in business acumen.

However, many of these business acumen competencies change in the context of innovation. For example, the concept of project management has continued to evolve with governments increasingly focused on the delivery of products and services. The need to understand modern approaches to more agile forms of project and product management is critical for leaders to manage teams, high-priority initiatives and accountability. Agile project management is also one of the skill sets with the lowest reported usage according the OECD survey on innovation skills presented in Chapter 2. Likewise, traditional budget management becomes more challenging when dealing with iterative processes and remains one of the common barriers to citizen-centred activities which require collaboration across institutional (and budgetary) silos.

In discussions about public sector leadership, it is often assumed that the “manager” of a team is also the “leader” of the team. Managers of teams, organisations and ministries are expected to be both proficient managers and leaders to the point that the terms are generally used interchangeable. If managers were all proficient leaders, innovation would likely be occurring at a higher level than it is today in Brazil. Therefore, it is important to differentiate the terms and their implications.

Even in origin, manager and leader have different meanings. The modern day definition of leader stems from an old English term “to be first.” Meanwhile, manager has its roots in Italian and French, and the French word, ménager, means “to keep house.”

Managers provide process oversight and keep things running smoothly. In terms of the Brazilian public sector, managers appear to focus first and foremost on documenting activities that auditing organisations require so as to prove that each step was followed in a defined process. This activity becomes the core driver for managers – valuing the checkbox of activities over attempting to inspire and lead.

As William Saito, special adviser from the Cabinet Office of Japan, stated in the 2015 OECD Idea Factory: “In the age of rapid innovation, it is important to distinguish between leadership and management... Today we really need leadership. While managers are needed to optimise mass production and cost reduction, leadership is needed for the rapid rate of innovation. Companies need to hire for leadership qualities, such as constantly doing new things and not being afraid to fail.”

Therefore, the challenge is not developing managers, but elevating the current and future public sector managers into public sector leaders. This requires a great focus on the development of innovation skills and mindsets while maintaining and reviewing the strong standard already established for business acumen in light of innovation in the public sector.

Source: OECD IdeaFactory (2015), “Shaping our future leaders”, https://www.oecd.org/forum/about/OECD-2015-IdeaFactory-Shaping-Our-Future-Leaders.pdf.

Innovation skills

In 2017, the Observatory of Public Sector Innovation (OPSI) developed “The six core skills areas of public sector innovation” (see Figure 1.4 in Chapter 1) based on insights from innovators around the world (OECD, 2017).

The skills model is intended to help individual civil servants become practitioners, and to ensure that leaders gain an understanding of innovation methods, mindsets and strategies to properly lead, support and embrace new and different solutions. By having a stronger understanding of innovation skills, leaders are able to provide the space and resources necessary for divergent ideas to be explored and tested. Without such an understanding, leaders can unintentionally undermine their organisation’s potential to use innovation skills, processes, methodologies or solutions.

As with business acumen, leaders should be more capable in some skills areas. During the OECD’s missions to Brazil, a leader’s ability to “win hearts and minds” and “articulate a vision” was seen as extremely important to current Brazilian public sector innovators. Many Brazilian public servants used the term “communication” to encapsulate the gap, but communication is a broad term that often translates into simply increasing the volume of talking or e-mails without increasing understanding, building empathy or creating coalitions.

Rather, public sector leaders should be strong storytellers. Storytelling can be defined as communications with empathy. Storytelling does not simply mean being an expert orator, but rather, explaining a vision, priority, change or initiative in a way that builds support. This requires leaders to understand their audience’s priorities, values, experiences and feelings to effectively deliver a message regardless of the medium.

Finally, as leaders drive, lead and make space for innovation, they themselves need to show a strong ability to challenge the status quo. This requires skills related to political process and timing, legal understanding to clarify areas where innovation is possible, and the ability to build new and different coalitions that allow for novel and divergent thinking. The OECD calls this skill set “insurgency”.

Mindsets

In the OECD’s discussions with leaders and innovators in Brazil, the mindsets of public sector leaders were the most cited factor in determining a successful innovative leader. They were also cited as the largest gap in Brazilian senior leadership.

While mindsets are usually listed as core competencies in many public sector leadership models, they are rarely tested, assessed and valued as much as technical competencies due to the lack of assessment tools.

Mindsets shape culture, values and experiences in the public sector. If leaders show they do not value a digital mindset, most digital projects are likely to fail due to a lack of leadership support (i.e. allocating the necessary resources, training employees in digital skills or helping teams overcome bureaucratic challenges) regardless of the demands of civil society. Therefore, without the proper focus on the mindsets of the public sector, good employees become disengaged or leave, new ideas are not generated, and progress stalls.

Additionally, many of these mindsets are necessary for successful implementation of innovation skills or business acumen. For instance, a leader will struggle to achieve results without having a clear vision, driving the change necessary to achieve that vision and communicating the vision appropriately. This also relates to a leader’s ability to be inspiring. Leaders who can collectively develop and sell a vision and inspire others are more likely to achieve results, see innovative ideas flow throughout the organisation and improve the value of the public sector.

Based on the OECD Digital Government Review of Brazil, the OECD recommends leaders also be equipped with a digital mindset. This does not mean that a leader must be fluent in digital technologies, but rather, that leaders, even in non-technical positions, must have an understanding of why digital is critical to any government solution and incorporate digital thinking into change processes as early as possible (OECD, 2018b).

Mindsets are not simply how a leader relates to others, but also reflect how they lead and affect others. Leaders must have a deep empathy for public servants, the people of Brazil and their own leadership. By having an understanding of the people that are part of their system, they also gain a greater interpersonal awareness whereby leaders understand how their actions, attitudes and demands impact others.

Mindsets are becoming more critical to the definition of good leadership in the public service. Certain mindsets were already listed in the Estonian and US models. Additionally, in 2014 the United Kingdom emphasised how critical mindsets were to leadership by releasing a Civil Service Leadership Statement (Figure 3.9).

This statement reflects the importance of mindsets to delivering public value by emphasising that inspiring, confident and empowering are the three most critical roles and expectations of leaders.

Identifying the needed leadership competencies in Brazil’s senior levels is only the first step towards consistently deploying these skills. OECD countries increasingly develop policies, processes, systems and tools to ensure that their senior leaders have the abilities, motivations and opportunities needed to drive innovation and lead change. The emergence of senior civil service systems in many OECD countries aims to develop the supply of, and ensure demand for, the types of competencies discussed in this chapter. Chapter 4 looks at how some initiatives are emerging in Brazil’s federal public service to build the supply of such competencies through the development of current and potential future leaders. Taking into account that developing this supply of competencies will not achieve results if there no demand for them, Chapter 5 looks at what more needs to be done to build the demand for these competencies among those who take appointment decisions for these positions, and hold them accountable for performance.

References

Australian Public Service Commission (2018), State of the Service Report 2017-18, Commonwealth of Australia, https://www.apsc.gov.au/sites/default/files/18583_-_apsc_-_sosr_-_web.pdf.

Brown, M. and L. Treviño (2006), “Ethical leadership: A review and future directions”, Leadership Quarterly, Vol. 17/6, pp. 595 616, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2006.10.004.

Casa Civil (1994), Decreto No. 1.171, de 22 de Junho de 1994 que Aprova o Código de Ética Profissional do Servidor Público Civil do Poder Executivo Federal, www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/decreto/d1171.htm.

Crosby, B.C. and J.M. Bryson (2018), “Why leadership of public leadership research matters: And what to do about it”, Public Management Review, Vol. 20/9, pp. 1264-1286, https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2017.1348731.

ENAP (2010), “Desenvolvimento de competências de direção: A experiência da Escola Nacional de Administração Pública”, National School of Public Administration, Brasilia.

Estonian Government (2017), “Competency framework”, webpage, https://www.riigikantselei.ee/en/supporting-government/top-executives-civil-service/competency-framework.

Fundação Dom Cabral (2018), “Mapas das competências gerenciais”, unpublished.

Instituto República (2018), “Relatório da 3ª Conferencia Anual do Instituto República ‘“Serviço Público: Desafios no Brasil’”, unpublished.

OECD (2019a), The Innovation System of the Public Service of Brazil: An exploration of its past, present and future journey, OECD Publishing, Paris.

OECD (2019b), Recommendation of the Council on Public Service Leadership and Capability, OECD, Paris, https://www.oecd.org/gov/pem/recommendation-on-public-service-leadership-and-capability.htm.

OECD (2017), “Core skills for public sector innovation: A beta model”, OECD, Paris.

OECD (2016), “Strategic Human Resources Management Survey”, OECD, Paris.

OECD IdeaFactory (2015), “Shaping our future leaders”, https://www.oecd.org/forum/about/OECD-2015-IdeaFactory-Shaping-Our-Future-Leaders.pdf.

Treviño, L.K., L.P. Hartman and M. Brown (2000), “Moral person and moral manager: How executives develop a reputation for ethical leadership”, California Management Review, Vol. 42/4, pp. 128-142, https://doi.org/10.2307/41166057.

Van Wart, M. (2011), Dynamics of Leadership in Public Service: Theory and Practice, 2nd ed., M.E. Sharpe, Armonk, NY.

Wilson, R. (2013), Anti-Hero: The Hidden Revolution in Leadership and Change, OSCA Agency ltd.

Notes

← 1. For more information, see: https://www.opm.gov/policy-data-oversight/senior-executive-service/executive-core-qualifications.

← 2. For more about the US Office of Personnel Management executive core qualifications, see: https://www.hks.harvard.edu/educational-programs/executive-education/admissions-fees/executive-core-qualifications.

← 3. For more information about Estonia’s competency model, see: https://riigikantselei.ee/en/supporting-government/top-executives-civil-service/competency-framework.