Findings and recommendations

This report presents the findings and recommendations of the 2022 development co-operation peer review of the United States. In accordance with the 2021 methodology, the report does not cover all components identified in the peer review analytical framework but focuses on select areas of US development co-operation that were identified in consultation with the United States government and its partners. After an overview of the current economic and political context, the report analyses US development co-operation in five areas: the need for a coherent whole-of-government policy; coherence between domestic policies and development objectives; the extent to which the US development co-operation system is fit for purpose; efforts to achieve localisation of US development co-operation; and the extent to which US development co-operation is fit for fragility. For each area, the report identifies strengths of the United States as well as challenges that it faces and opportunities or risks that lie ahead.

Political and economic context

Since the last peer review in 2016, the United States has undergone significant political change. From January 2017, Donald Trump, of the Republican Party, served as president for four years. During this period, legislative support for and appropriation of foreign assistance remained relatively constant. Four years later, in January 2021, President Joe Biden, of the Democratic Party, took office. The Biden administration’s ability to advance its legislative agenda and the resources to implement it are constrained, given the narrow Democratic majority in the House of Representatives and an evenly divided Senate. All House seats and 35 Senate seats are up for election in November 2022. If the balance changes and the Democratic Party loses its majority in either body in these midterm elections, the administration will find it more challenging to advance its priorities.

The US economy suffered from the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, and Russia’s war against Ukraine may slow the recovery further. Resilient economic growth and a steady decline in the unemployment rate during the 2010s boosted material standards of living for Americans. Measures to contain the spread of the coronavirus contributed to the one of the largest shocks suffered by the US economy outside of wartime and led to very high unemployment. Cash transfers and expanded unemployment benefits helped cushion the impact on vulnerable households (OECD, 2020[1]). US real gross domestic product (GDP) had been anticipated to grow by 5.6% in 2021, then drop to 3.7% in 2022 and to 2.4% in 2023 (OECD, 2021[2]). However, underlying inflationary pressure and the war in Ukraine may result in a decline of more than 1% in global growth and higher inflation (OECD, 2022[3]).

The Trump administration defined its security strategy as protecting Americans and preserving their way of life, promoting US prosperity, supporting peace through strength, and advancing US influence in the world. The fourth pillar of the 2017 National Security Strategy prioritised partnering with countries that are interested in economic progress and aligned with US interests; a shifting away from development assistance based on grants and towards attracting private investment and catalysing private sector activity; and, in fragile states, working with “reformers” and synchronising diplomatic, economic and military tools (White House, 2017[4]). The strategy also sought to achieve better outcomes in multilateral forums in line with US interests.

The Biden administration’s Interim National Security Strategic Guidance, issued in March 2021, acknowledges the changing distribution of power across the world. It pledges that the United States will reinvigorate and modernise its alliances and partnerships and resume its position of leadership in international and multilateral institutions. The interim strategic guidance further recognises the “profound” risks posed by the COVID-19 pandemic, economic downturn, and climate and humanitarian crises and renews the US commitment to global development and international co-operation (White House, 2021[5]).

Development co-operation system

In November 2021, US Agency for International Development (USAID) Administrator Samantha Power announced her vision of more inclusive, accessible, equitable and responsive global development. To achieve this, she set forth three priorities: allow people from more diverse backgrounds and partners of all kinds to participate, making aid more inclusive and accessible; focus more on the voices and needs of the most marginalised, making aid more equitable; and listening to what partners are asking of the United States in countries where it works, making aid more responsive (USAID, 2021[6]).

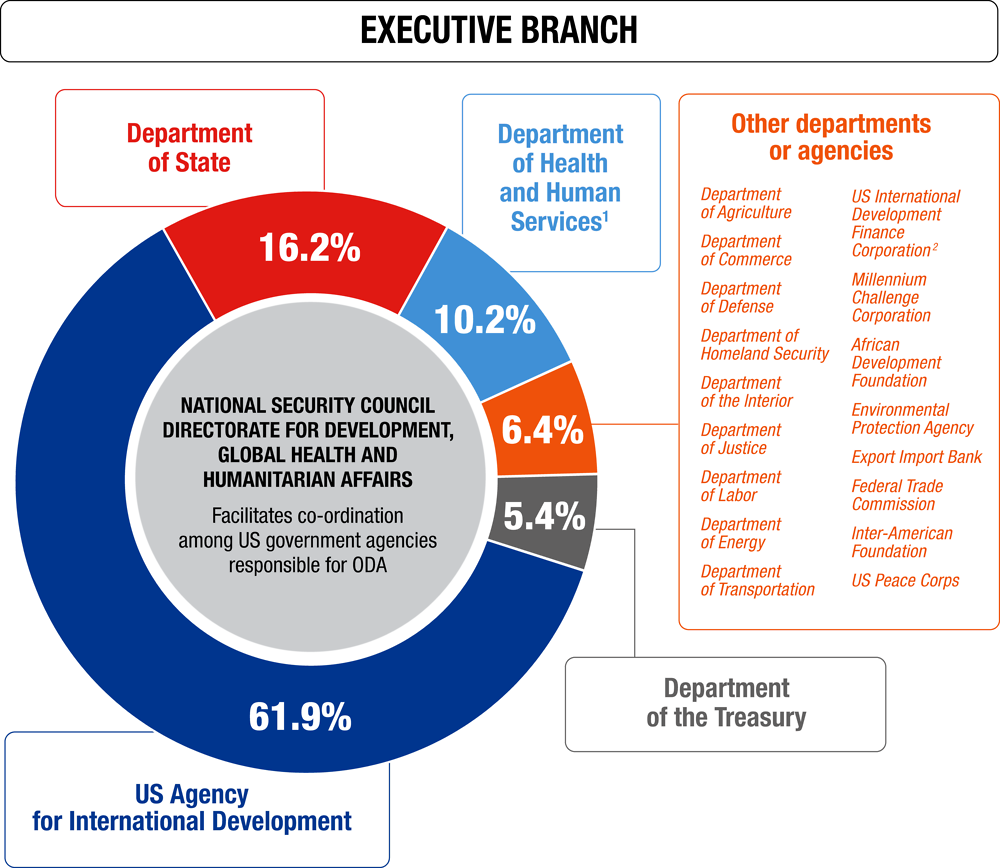

The development co-operation system of the United States is complex.1 Twenty-one federal government agencies provide official development assistance (ODA) and other official flows (OOF). USAID, the State Department, the Department of the Treasury, and the Department of Health and Human Services deliver the largest amounts of ODA (Figure 1). The Snapshot of the United States’ development co-operation accompanying this peer review provides more detail on the US development co-operation system (OECD, 2022[7]).

Strong and consistent bipartisan support for foreign assistance in the US Congress creates both opportunities and challenges. The US Congress repeatedly resisted efforts by the previous administration to cut the foreign assistance budget, and overall legislative support for humanitarian assistance remains strong. At the same time, the presence of a more diverse group of incoming members of Congress in recent years has led to increased congressional interest in development co-operation and to some extent greater congressional control over how the Department of State, Foreign Operations and Related Programs (SFOPs) budget is allocated and spent.

ODA from the United States reached its highest-ever volume of USD 42.3 billion in 2021, according to preliminary figures (in current prices), a 14.4% increase over 2020 (USD 35.6 billion in constant prices), reflecting an increase in contributions to multilateral organisations and the purchase of vaccines to be donated to developing countries. ODA had dropped in 2019 to USD 34 billion from USD 38 billion in 2016. The latest ODA volume represents 0.18% of gross national income (GNI), ranking the United States 23rd among DAC member countries. While it is close to the most recent high of 0.19% achieved in 2016, the share of national income dedicated to ODA by the United States falls short of the 0.20% of GNI it achieved in 2010 and 2011 and well short of the United Nations (UN) target of 0.70% of GNI.

Development co-operation is an important dimension of national security and a leading instrument of US foreign policy

The Biden administration has renewed US commitment to global development and international co-operation and positions diplomacy, development and economic statecraft as the leading instruments of US foreign policy. The forthcoming National Security Strategy, which builds on the March 2021 interim guidance, will articulate the role of development co-operation (White House, 2021[5]).

USAID’s participation in the National Security Council has grown over the past 15 years as issues such as global health, humanitarian assistance, climate change, democracy, corruption, conflict and stabilisation, and food security have become central to foreign policy decisions.2 Consistent participation of the USAID administrator in the Principals Committee would help ensure that development perspectives are always considered in matters affecting national and global security. Whether the administrator participates is decided by each president and administration.

A whole-of-government development policy and refreshed institutional arrangements would provide unity of purpose to US efforts

The United States has not updated its whole-of-government development co-operation policy despite significant changes in the global development landscape. In 2010, the Presidential Policy Directive Number 6 on Global Development (PPD-6) elevated development as a core pillar of US international engagement and set ambitious development goals aligned with the United States’ strategic national objectives of peace, security, global prosperity, universal values and human rights (White House, 2010[8]). The previous administration’s National Security Strategy addressed development assistance, but much has changed in the past decade, including the role of the United States and other major powers. An updated policy would provide coherence to US development co-operation and offer its developing country, bilateral and multilateral partners clarity on US priorities.

Mechanisms for ensuring coherence in development policy across the US government (USG) were not maintained following the change in administration in 2017. The PPD-6 proposed that a national global development strategy be developed every four years and approved by the president alongside the Quadrennial Diplomacy and Development Reviews by the State Department and USAID. The PPD-6 also established an Interagency Policy Committee on Global Development, led by national security staff, and a US Global Development Council3 (White House, 2010[8]). These initiatives were not continued.

A whole-of-government development co-operation policy would enable the United States to achieve greater impact. A policy outlining an agreed, coherent and strategic vision for development co-operation might facilitate strategic conversations across the federal government about the content of such a policy and its ongoing implementation. A clear vision would provide direction to federal agencies and offer other US actors – states, localities, tribes, territories, and other stakeholders such as non-governmental organisations (NGOs), civil society, the private sector, philanthropic foundations and academia – the opportunity to lend their support. It would inform the USG regional, country and thematic strategies and provide a solid basis for the United States to engage proactively with multilateral, regional, bilateral and country partners. Such an approach underpins USG efforts at home and abroad to address the climate crisis (Box 2) and to promote gender equity and equality (White House, 2021[9]).

The 2030 Agenda provides a ready framework for the United States to agree to global development priorities and to exercise global leadership

The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) could provide a framework for the US commitment to global development. The United States played a key role in negotiating both the Addis Ababa Action Agenda and the 2030 Agenda, but these have not since featured prominently in its narrative or operations (Ingram and Pipa, 2022[10]). Nevertheless, the SDGs provide a coherent, integrated framework underpinning the national development plans and strategies of the developing country, bilateral and multilateral partners of the United States and also provide a basis for advancing sustainable development domestically. Acknowledging the interlinkages between the SDGs and using SDGs to describe the challenges facing the United States and its partners would ground the United States’ renewed commitment in an existing, broadly accepted vision of global sustainable development. This would also create synergies among US thematic priorities and enable the United States to leverage the efforts of those civil society and private sector actors that share a commitment to the 2030 Agenda.

More effective co-ordination across and between US government agencies can achieve greater interagency coherence

US development co-operation has the potential to be more than the sum of its parts. With 21 agencies engaged in development co-operation, extensive co-ordination is required in Washington, DC and at US embassies and missions. While internal co-ordination efforts are time consuming, they nevertheless add value at US embassies and missions where integrated country strategies articulate US priorities and set goals and management objectives for the USG. Country Development Cooperation Strategies in turn describe how USAID supports US priorities and partner country national development plans. Organising co-ordination around the key pillars of US engagement can create synergies across the USG interagency, as seen in Kenya.4 Particularly in sectors managed directly from Washington, DC or involving departments or agencies based in the United States, there is a risk of fragmentation in USG support, as noted in Kenya. USG efforts to control infectious diseases successfully leverage a whole-of-government approach – with, for example, the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) helping several countries to achieve epidemic control (Box 1).

Given the number of agencies and initiatives, keeping track of, programming and achieving synergies in different US government investments is challenging. The large number of agencies results in a complicated institutional system. The State Department offers guidance for developing foreign assistance strategies for each country through an Integrated Country Strategy (ICS) that aims to minimise fragmentation and improve co-ordination within foreign assistance planning,5 and interagency members use data and evidence, including from evaluations, to improve programming and inform decision making. However, use of data and evidence is focused at the activity level. A more strategic approach to evaluation and knowledge sharing across interagency members would enhance learning and improvement (Fit-for-purpose development co-operation system).

An integrated approach across the portfolio could lead to greater coherence. Interventions to support nature and wildlife conservancies and address trafficking of wildlife in Kenya, for example, are well co-ordinated and harness the considerable expertise, experience and resources available across the USG interagency. Kenyan government counterparts highly appreciate the specialised expertise that USG agencies offer. Wildlife trafficking initiatives are co-ordinated with efforts to combat corruption, terrorism, trafficking in drugs and people, and violent extremism. However, these interventions could achieve greater impact if delivered together with local authorities in a more integrated manner that addresses the multiple challenges facing rangeland communities, such as food security, access to health care and productive opportunities.

Strong internal co-ordination could extend to better co-ordination with partners. Partner government counterparts find it burdensome to deal with a range of agencies using differing administrative and reporting requirements, as seen in Indonesia and Kenya. Designating an overall point of contact at US missions and streamlining procedures across the interagency, as recommended in the 2016 peer review, would improve co-ordination with government counterparts in sectors supported by many interagency members.

Healthy lives and well-being are essential to sustainable development and building prosperous societies. In 2020, the United States invested 33% of bilateral ODA (USD 9.7 billion) in the health sector, primarily targeting infectious diseases such as malaria and HIV/AIDS – and recently COVID-19 – and investing in global health security. Its whole-of-government approach involving 15 agencies saves lives, protects people most vulnerable to disease, promotes stability in communities and nations, and leverages other resources to address and invest in shared global health challenges. Bipartisan support in the US Congress is critical.

Each entity brings particular strengths. USAID offers technical assistance, training, commodity purchase and private sector partnerships. The Department of Health and Human Services provides policy and management support and, within the department, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) offer expertise in epidemiology, surveillance, laboratory systems, emergency response and workforce development.

USAID and the CDC co-implement the President’s Malaria Initiative in 24 countries in sub-Saharan Africa and three programmes in the Greater Mekong Subregion of Southeast Asia. Since 2000, the United States has helped save almost 7.6 million lives and prevent more than 1.5 billion malaria cases.

The President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) is led by the Department of State and implemented by six other US government departments and agencies.1 PEPFAR has saved more than 21 million lives, prevented millions of HIV infections, and supported at least 20 countries in achieving epidemic control of HIV or reaching HIV treatment targets. The initiative helps countries build a firm local foundation to prevent, detect and respond to other health threats, thus enhancing global health security.

In 2014, the United States helped launch the Global Health Security Agenda, which enhances the world’s ability to prevent, detect and respond to infectious disease threats. The U.S. government response is co-ordinated by the White House National Security Council (NSC) for both Global COVID-19 Response and Health Security.

In 2021, USAID’s USD 310 million tuberculosis investments resulted in 3.8 million cases detected, a 20% decrease in notifications, an 89% treatment success rate and 33 000 health workers trained.

The US COVID-19 response assisted more than 100 partner countries to accelerate widespread and equitable access and delivery of safe and effective COVID-19 vaccines and to strengthen vaccine readiness. The United States assisted Moderna to sign a memorandum of understanding establishing Kenya as the location for the company's mRNA manufacturing facility on the African continent.

Joint strategies facilitate whole-of-government efforts. To counter fragmentation, overlap and duplication, joint and individual agency strategies delineate roles, responsibilities and co-ordination mechanisms; integrate with other related strategies; and assess progress towards goals, including through activities to achieve results, performance indicators, and monitoring and evaluation plans.

Data helps to inform the focus of infectious disease efforts. But a broader interlinked set of targets will seek to track the social and legal impediments that hamper access to services. Greater use of strategic evaluation would determine if programmes are achieving their goals and inform improvement.

Although the US focus on infectious disease is complemented by a substantial increase of funding to global health security, the allocation of over 70% of bilateral ODA for health2 to communicable diseases in the FY 2022 appropriations means the United States is relatively less well equipped to help strengthen health systems in line with partner countries’ ambitions for universal health coverage.

Note: This practice is documented in more detail on the Development Co-operation TIPs • Tools Insights Practices platform at www.oecd.org/development-cooperation-learning/practices/the-united-states-whole-of-government-approach-to-global-health-challenges-ed48d383.

← 1. The six agencies are USAID; the Department of Health and Human Services (including the CDC, Health Resources and Service Administration, and National Institutes of Health); the Department of Defense; the Peace Corps; the Department of Commerce; and the Department of the Treasury.

← 2. This includes bilateral assistance for health from the State Department and USAID, but excludes the amount for Emergency Global Health Programs, which was not yet known for FY 2022.

Source: Congressional Research Service (2022[11]), Department of State, Foreign Operations, and Related Programs: FY2022 Budget and Appropriations, https://sgp.fas.org/crs/row/R46935.pdf; Government of the United States (2022[12]), 2022 OECD DAC Peer Review: Self-Assessment - United States of America; Government of the United States (2019[13]), United States Government Global Health Security Strategy, https://trumpwhitehouse.archives.gov/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/GHSS.pdf.

Articulating a strategic vision for US development co-operation

A forthcoming National Security Strategy and an integrated global development co-operation policy offer an opportunity to articulate an agreed, coherent and strategic vision for US development co-operation. Building on the interim guidance, the National Security Strategy will articulate the administration’s global development priorities and confirm how these contribute to the national security and foreign policy of the United States. In October 2021, the National Security Council (NSC) Directorate for Development, Global Health and Humanitarian Response commenced a process to develop an integrated global development co-operation policy, which is intended to build on PPD-6 (Government of the United States, 2022[12]). Through both of these processes, the United States might set out:

the links between the interests of Americans and those of people in communities around the world

how the United States will exercise global leadership in the face of multiple crises, global challenges, and threats to shared interests and values

an enhanced whole-of-government policy directing USG agencies and encouraging other actors to work together to make progress toward achieving the 2030 Agenda and the SDGs

the importance to the US federal government of working with its country, bilateral, regional and multilateral partners in pursuit of its vision

the importance of systematically addressing domestic policies that have negative consequences for developing countries.

1. To provide a strong framework for an effective whole-of-government approach, the United States Administration should set out an integrated global development co-operation policy co-ordinated by the National Security Council that:

underlines the relevance of development for all stakeholders, domestic and foreign, within the United States’ foreign policy

maximises the impact of its development co-operation by ensuring that all federal government departments and agencies work in a coherent and co-ordinated manner to deliver the policy

aligns all development co-operation to the Sustainable Development Goals, which provide both a common framework to work with partners and a clear link to poverty reduction and inclusive economic growth.

The United States is ideally placed to advance global public goods and address global challenges at home and abroad

Sustainable development is not a zero-sum game. The 2030 Agenda requires action at the subnational, national, regional and global levels in pursuit of sustainable, inclusive and sustained economic growth (UN, 2015[14]). US policies and regulations can have positive and negative spillover effects, including on developing country partners. Removing barriers to international trade and promoting the free flow of capital offer both opportunities and challenges. Companies may benefit from US integration into global markets, shifting jobs to developing economies where labour is cheaper and the overall cost of doing business is lower. However, without proper attention, the jobs created outside the United States may exacerbate existing problems with labour rights, equal opportunity and environmental stewardship in these economies (White House, 2021[5]).

The US ambition to build an equitable and inclusive global economy demands coherent action at home and abroad, which in turn requires coherence between domestic and foreign policies. The Biden administration recognises that domestic renewal is critical to foreign policy and is promoting action on a range of critical economic, social and environmental issues that impact and achieve mutual benefits for the United States and the world. Advancing these issues equitably requires a consistent and clear understanding of the effects of US policies – at home and abroad.

US efforts to address global challenges can reduce negative impacts on developing countries. The COVID-19 pandemic and the climate crisis vividly demonstrate how global challenges can negatively impact the United States. They also show the significant influence the United States can have to reduce the negative impacts at home and abroad. Given the size, importance and impact of its economy, the United States is ideally placed to lead action in response to global challenges, using its influence to encourage other nations to support solutions that benefit both their own people and communities around the world.

Managing trade-offs requires careful analysis, reconciliation and resolution of competing priorities. When US interests converge with those of its partners, US leadership can bring about positive change, as seen in its engagement to reform international taxation rules to ensure multinational enterprises pay a fair share of tax wherever they operate, counter corruption and combat illicit financial flows. However, where US interests diverge from those of developing countries or where competing interests exist across USG agencies, these differences need to be carefully considered and resolved. It is not easy to do so, and such decisions should not be left to chance.

Opportunities exist to do more to address negative spillover effects on development and advance sustainable development globally

The United States is thinking more intentionally about how domestic policies impact the rest of the world, as work on climate and COVID-19 demonstrate, but the tools to systematically do so are lacking. The United States ranks lower than many other OECD member countries on one index in terms of the effects of its policies on developing countries. The United States is ranked 22nd out of 40 countries overall on the 2021 Commitment to Development Index, scoring highest on security (6th), trade (10th) and health (17th) but low on environment (37th), technology (29th) and investment (24th)6 (Center for Global Development, 2021[15]). These rankings suggest that there is more the United States might do to address negative spillover effects of its policies on developing countries. The following paragraphs offer some examples.

The African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA) enhances market access for qualifying sub-Saharan African countries, but requires regular renewal.7 Enacted in 2000, it expanded duty-free benefits offered under the US Generalized System of Preferences (GSP) programme by adding new product lines. Any extension beyond its expiry in 2025 will require bipartisan support in Congress. Market access arrangements such as AGOA and GSP offer economic benefits to eligible countries and can help countries broaden their export base.8 To increase bilateral trade and investment, the Prosper Africa Initiative, which builds and expands on the US government's trade and investment support across Africa, including AGOA trade preferences.9

US anti-corruption efforts will be enhanced by addressing beneficial ownership and strengthening international co-operation in the exchange of information. The United States Strategy on Countering Corruption notes that legal and regulatory deficiencies in the United States and other high-income countries, including shortcomings in beneficial ownership transparency, allow assets to be laundered and the proceeds of crime to be obscured. The strategy also recognises the particular responsibilities in this area that rest with the United States as the largest economy in the international financial system (White House, 2021[16]). In addition to finalising beneficial ownership regulations, it will be important for the United States to ensure that coverage is comprehensive. Further, exchange of information and co-operation with other jurisdictions would enable the United States to be more fully compliant with anti-money laundering and counter-terrorist financing measures (Financial Action Task Force, 2020[17]).

Tackling the climate crisis requires significant US efforts to transition from a reliance on fossil fuels. The United States aims to promote ending its international financing of carbon-intensive fossil fuel-based energy and to eliminate fossil fuel subsidies from the federal government’s budget request for FY 2022 and beyond. Exploring innovation, commercialisation, and deployment of clean energy technologies and infrastructure is a critical part of the US approach (White House, 2021[18]). Following a pause on new oil and gas leases on public lands in the second quarter of 2021, the Department of the Interior resumed onshore oil and gas lease sales on federal land at a higher royalty rate than previously charged (US Department of the Interior, 2022[19]). This was not an explicit response to the significant increase in fuel prices resulting from Russia’s war against Ukraine, as some critics have claimed. Nevertheless, the resumption does point to the need for greater efforts to spur the transition to a low emissions, climate-resilient US economy. The 2030 domestic emissions reduction target in the United States’ nationally determined contribution is now aligned with a pathway towards 1.5°C warming. However, given that the United States has the highest CO2 emissions among OECD countries and accounts for 15% of global CO2 emissions,10 continued efforts on implementation will be needed to further reduce emissions and enable the United States to be in alignment to the 1.5°C temperature limit of the Paris Agreement (Box 2) and to improve policy coherence at home and abroad.

Achieving policy coherence requires a strategic vision, political leadership and effective mechanisms and tools

Greater coherence between US domestic policies and foreign policy objectives would help the United States reinvigorate its global leadership. In the face of unprecedented global challenges, effort across a broad front will be needed to “boldly engage the world”, as the administration has described its task (White House, 2021[5]). Integrating sustainable development throughout domestic and foreign policy making would be an important first step. The forthcoming National Security Strategy and an integrated global development co-operation policy are opportunities to set out how the United States will deliver coherent domestic and foreign policies. These documents might articulate a strategic vision, provide political leadership, and encourage the establishment of effective mechanisms and tools for the United States as it grapples with new challenges on the global landscape.

Systematic assessment can foster positive impacts of policies and regulations at home and abroad and reduce their negative spillover effects. Many countries, the United States included, create domestic policy in isolation from foreign and international development policy or global public goods (Dissanayake, 2021[20]). US law requires that some assistance to developing countries be assessed for its impact on US domestic economic interests. However, there is no reciprocal process whereby the United States systematically assesses the spillover impact of its domestic policies on the economic or sustainable development interests of developing countries. A key premise of the OECD Recommendation of the Council on Policy Coherence for Sustainable Development is that to achieve the 2030 Agenda, governments need processes, systems, structures and tools to manage and co-ordinate coherent policy at all levels (OECD, 2019[21]).

Coherent action at home and abroad to, among other things, counter corruption, address the climate crisis, and advance gender equity and equality must be systematic and endure. In these instances, the Biden administration has provided a strategic vision and political leadership and established mechanisms requiring the USG to take action and to report on progress (White House, 2021[9]; White House, 2021[18]; White House, 2021[16]). However, the institutional arrangements reflect the current administration’s priorities and, in the case of climate, depend on congressional funding for implementation (Box 2). In lieu of lasting, formal arrangements, executive orders requiring domestic and global efforts are important options available to the USG. However, these can easily be overturned or discontinued with a change in administration.

Updated institutional mandates could help deliver coherent policies. A range of institutions offer policy advice to the president. The Council of Economic Advisers and the NSC are long-standing entities and were established by statute.11 The National Economic Council and the Domestic Policy Council were created by executive order in 1993 to co-ordinate policy advice on domestic and international economic issues and domestic policies and to monitor implementation of the president’s economic and domestic policy agendas. The NSC considers development objectives alongside national security and foreign policy matters. However, when it comes to global and domestic food security, for example, the three aforementioned councils are not mandated to ensure routine coherence between US domestic policies and development objectives.

The United States has a long-established mechanism for analysing the domestic consequences and effects of regulations but not to address the transborder effects on partner countries. The Office of Management and Budget (OMB) in the Executive Office of the President requires that reviews of any significant regulatory action include regulatory analysis by its Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs. The focus is domestic, with effects of regulations beyond US borders reported separately (US Office of Management and Budget, 2003[22]). The Biden administration recognises the need to improve and modernise the regulatory review process to include distributional impact analysis, among other things (White House, 2021[23]). The United States might consider including in updated guidance a requirement to assess the positive and negative spillover effects of US regulations on partner countries and tools for doing so.

Moving the world off a dangerous and potentially catastrophic climate trajectory requires significant global reductions in greenhouse gas emissions and net-zero global emissions within 30 years.

One of President Biden’s first actions when he took office was to issue the Executive Order on Tackling the Climate Crisis at Home and Abroad, which provides vision, leadership and institutional mechanisms for the federal government to coherently address domestic, transboundary and long-term impacts of climate change and to contribute to achieving the SDGs. The executive order puts the climate crisis at the forefront of US foreign policy and national security planning, setting forth the aims of building resilience at home and abroad to the impacts of climate change and working bilaterally and multilaterally to support a sustainable global climate pathway.

The Leaders Climate Summit (April 2021) sought to raise climate ambition in advance of the UN Climate Change Conference (COP 26). In June 2021, the United States and other Group of Seven members committed to end direct government support for unabated thermal coal power generation by the end of 2021 and provide up to USD 2 billion to support developing countries in transitioning from coal. They further outlined strategies to decarbonise industry and pledged to reverse the loss of global biodiversity and conserve at least 30% of global land and marine areas by 2030.

The US nationally determined contribution (April 2021) set a target of reducing net greenhouse gas emissions by 50-52% below 2005 levels in 2030. Its long-term strategy (November 2021) aimed to achieve net-zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050. The Federal Sustainability Plan (December 2021) outlined how the United States will reduce emissions across federal operations, invest in US clean energy industries and manufacturing, and create clean, healthy and resilient communities.

In its International Climate Finance Plan (April 2021), the United States intends by 2024 to double annual public climate financing to developing countries relative to FY 2013-16. As part of this effort, the President’s Emergency Plan for Adaptation and Resilience (PREPARE) aims to provide USD 3 billion in adaptation finance annually by FY 2024. In USAID’s 2022-30 Climate Strategy (April 2022), which will guide its whole-of-agency approach to advance equitable and ambitious actions to confront the climate crisis, USAID commits to reduce, avoid or sequester 6 billion metric tonnes of CO2 equivalent; conserve, restore or manage 100 million hectares with a climate mitigation benefit; enable improved climate resilience for 500 million people; and mobilise USD 150 billion in public and private finance to address climate change. The USAID plan for global action on climate equity includes improving participation and leadership in climate action for Indigenous Peoples, local communities, and women and youth in at least 40 partner countries by 2030.

The executive order on tackling the climate crisis is an important but insufficient mechanism for addressing the domestic, transboundary and long-term impacts of climate change. While it reflects the priorities of the current administration, congressional approval is needed to enact laws and regulations to translate the pledges to action. The US Congress passed the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act in 2021, but the Build Back Better Act that would provide clean energy tax credits, electric vehicle rebates and other climate-smart investments was stalled in the Senate at the time of writing. The administration’s pledges and initiatives would benefit from early engagement with Congress and broad outreach to legislators.

Transitioning from fossil fuels to renewable sources of energy requires greater targeted efforts by the United States and coherence across all sectors and levels of government. The US 2030 domestic emissions reduction target is consistent with 1.5°C warming and the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 puts the United States in a strong position to keep the 1.5 degree goal alive and deliver on global climate pledges.

Note: This practice is documented in more detail on the Development Co-operation TIPs • Tools Insights Practices platform at www.oecd.org/development-cooperation-learning/practices/united-states-tackling-the-climate-crisis-at-home-and-abroad-173c7832.

Source: US Department of State/Executive Office of the President (2021[24]), The Long-Term Strategy of the United States: Pathways to Net-Zero Greenhouse Gas Emissions by 2050, www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/US-Long-Term-Strategy.pdf; Government of the United States (2021[25]), The United States of America Nationally Determined Contribution, Reducing Greenhouse Gases in the United States - A 2030 Emissions Target, www4.unfccc.int/sites/ndcstaging/PublishedDocuments/United%20States%20of%20America%20First/United%20States%20NDC%20April%2021%202021%20Final.pdf; The White House, (2021[18]) Executive Order on Tackling the Climate Crisis at Home and Abroad, www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/presidential-actions/2021/01/27/executive-order-on-tackling-the-climate-crisis-at-home-and-abroad/.

2. In line with the interim National Security Strategy, the United States should establish institutional and operational mechanisms to identify, analyse and take action to mitigate the negative transboundary effects of domestic policies on partner countries and should regularly report on such action.

3. The United States should fully implement the Executive Order on Tackling the Climate Crisis at Home and Abroad, which recognises that climate considerations should be at the centre of domestic action, foreign policy and foreign assistance to achieve global climate ambitions including in the areas of agriculture, biodiversity and energy.

This fit-for-purpose section explores how the United States’ current development co-operation system supports the delivery and implementation of the extensive and sizeable US foreign assistance programme through collaborating, learning and adapting and through its partnerships, development finance instruments, budget formulation and appropriation process, and human resources.

Many actors inside and outside the US government have interests and a stake in programming, overseeing and delivering US foreign assistance. Significant political investment is needed to strengthen and modernise the US development co-operation system and even to achieve many of the ambitions outlined in the first four goals of the new USAID-State Department Joint Strategic Plan.12 Development co-operation requires a more streamlined system and incentives that serve to break down silos, ease collaboration, simplify appropriations processes, build in adaptation, prioritise locally led initiatives, and put nimble and reactive arrangements in place. In the current domestic political climate and given the multiple global crises, a push to reform and build up such a system is more challenging.

Nonetheless, renewed US leadership and multi-stakeholder approaches to address global challenges are promising, and the commitment to re-engage multilaterally is a welcome sign for other DAC members. The United States continues to be a leader in health and humanitarian aid, as illustrated by its response to the COVID-19 pandemic and the sheer volume of ODA for these areas. Initiatives such as Feed the Future, Power Africa and Prosper Africa are examples of how the country brings together the private sector, official funding and civil society to tackle important issues, in line with leveraging its whole-of-government approach to health challenges (as discussed in Box 1). While ODA volumes increased significantly in 2021, there is still scope for the United States to further increase ODA levels in real terms and as a proportion of GNI in line with its renewed global leadership and positive historic economic growth as recommended in past peer reviews. The United States has improved its performance in implementing the DAC Recommendation on Untying ODA (OECD, 2018[26]). In 2020, 72% of its bilateral ODA covered by the Recommendation was untied, which is a significant increase from the preceding five years.

Wide stakeholder interest in foreign policy objectives and foreign assistance looks set to continue, as demonstrated by an abundance of directives and inquiries from a more global citizenry and more diverse Congress. The 2016 peer review encouraged the United States to continue to focus on sectors and programmes where it has a comparative advantage, a difficult feat for a large donor faced with a seemingly endless list of requests. Prioritisation and knowing when to enact sunset clauses or drop previous priorities and initiatives may be even more necessary today. But these would require the interagency and stakeholders to adopt a longer-term vision and strategic review of what the United States aims to achieve beyond the year-to-year budget negotiations and to have Congress on board.

The United States is a generous multilateral partner that could further leverage its partnerships in partner countries

The United States has made a point of re-engaging multilaterally since 2021, when it substantially increased core (unearmarked) contributions to multilateral entities to USD 9.1 billion, or 21.5% of its gross ODA (compared to a DAC average of 28.3%) – the highest volume of any DAC member. In addition, US government actors provided USD 7.3 billion in earmarked funding to the multilateral system in 2020.13 The FY 2023 budget request proposes a near doubling of funding for multilateral assistance reflecting proposed expanded investments in the Green Climate Fund and the Climate Investment Funds. As US support to international climate change initiatives increases, demand is growing within the federal government for a systematic, interagency approach to more strategically fund multiple climate vehicles across accounts and government agencies. Such an approach could also include being transparent and explicit about how the United States uses multilateral and bilateral channels, as was suggested in a recent OECD portfolio similarity analysis,14 and about the impact it has on the effectiveness of the system as a whole.

The United States does not have a multilateral strategy or operational guidance for multilateral assistance, as was recommended in the last peer review. The United States has invested heavily in strong, robust systems of multilateral partners (for example, whistleblower protection, anti-corruption, fraud, and prevention of sexual exploitation, abuse and harassment) and in upholding norms and standards (for food, for example). Multilateral partners cite challenges related to the lack of standard operating procedures, including for financial contributions, when a single multilateral partner engages across different USG entities as well as challenges arising from delays in appropriations. Twenty-one USG agencies provide foreign assistance to or partner with multilateral organisations. The Secretary of State submits an annual report to Congress with an agency-by-agency breakdown of their financial and in-kind contributions made to international organisations.15 The Department of the Treasury submits a similar report to Congress on the US role in shaping the policies and lending decisions of international financial institutions.16 Although both documents fulfil transparency requirements, it is unclear whether and how they are used to inform future allocations. In the view of some partners, one consequence of the more diffused USG engagement is that advocacy for greater use of pooled funds and multilateral channels is often missing at key decision points in government.

Outside of regular replenishments, the US government adopts a delegated approach to multilateral partnerships, leaving it up to USAID, the USAID Washington operating unit, the USAID country office or the embassy to decide the partner of choice. An advantage of this approach is that the decision falls to those with the greatest interest and involvement in a given investment. But there can be a missed opportunity to connect funding policies and decisions in governing boards or elsewhere to specific investments. As a result, the United States may be less able at the partner country level to systematically leverage the important contributions it makes globally to complement its bilateral priorities. The relatively expanded mandate of the Office of Development Cooperation’s Multilateral Affairs Team at USAID is working towards ensuring the interconnection between USAID’s country-level work and funding and engagement at the headquarters level in respective international organisation governing bodies.

At the country level, the United States tends to invest little in structured dialogue or partnerships with other bilateral and multilateral partners, as seen in Kenya and Indonesia. Its more delegated approach to multilateral partnerships offers one possible explanation: Unless the USAID country office is providing earmarked funding to multilateral organisations to fulfil its country programme, it does not consider its role is to build on complementarity between what is provided centrally from headquarters and the country programme. In addition, given the size of the development co-operation system, US country and regional missions invest heavily in internal co-ordination across several different agencies and initiatives, and this focus leaves less appetite and time for co-ordinating with external actors (A coherent whole-of-government policy). Another reason, as noted in the discussion of appropriations, is that accounts and budget lines are linked to specific accountability requirements. This can make partnering with other bilateral or multilateral actors, themselves accountable to many members or shareholders, arduous and time consuming as both partners must meet the various requirements.17 Furthermore, the United States’ earmarked contributions tend to be large in volume, which may not incentivise it to pool funding and harmonise reporting requirements with other members or shareholders. The United States has strong country partnerships with some entities in which it is one of the largest contributors, among them the World Food Programme, the Global Fund, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees and the United Nation Children’s Fund. Notwithstanding the systemic challenges, there may be an opportunity for the United States to build on its important multilateral contributions and act through a broader coalition of partners at the country level to share risk and be more influential.

Establishing the Development Finance Corporation and expanding official finance instruments face some challenges

The authorisation of the US International Development Finance Corporation (DFC) marked a historic shift away from the long-standing US approach of providing foreign assistance almost exclusively in the form of grants and making available a greater range of instruments.18 One of the goals of DFC, which has a financing ceiling of up to USD 60 billion, is to “drive private capital” towards US foreign policy objectives19 (US International Development Finance Corporation, 2021[27]). However, the removal of the US connection, or nexus, requirement that applied to projects supported by one of DFC’s predecessor agencies, the Overseas Private Investment Corporation, means that DFC operations are wholly untied.20 DFC’s revenue source is an annual congressional appropriation that leverages US Treasury lending, with the proceeds of loans being returned to the US Treasury. This is not the case for many other bilateral development finance institutions. DFC has no need to maintain a credit rating, which should make it easier to prioritise investments in low- and lower middle-income countries. However, its development mandate has not prevented Congress and the administration from requesting waivers enabling DFC to fund other priorities in higher-income countries. Some have argued that these could undermine DFC’s strong initial bipartisan support as it risks becoming more instrumentalised.21 DFC has so far exceeded its annual goal of ensuring that at least 60% of the investments it supports are in low-income, lower middle-income or fragile countries and contexts. As the Inspector General of DFC noted on 21 March 2022, “DFC faces a difficult challenge in making investments that balance the competing interests of financial performance, development impact, and foreign policy, all while maintaining accountability and transparency” (US International Development Finance Corporation, 2022[28]).

The success of DFC will depend on how quickly it is able to deliver new instruments, particularly equity, and work with the US government and other partners.22 DFC faces challenges in its highly anticipated equity investment programme23 and in the time lag between investment decisions and disbursement of funds (US International Development Finance Corporation, 2022[28]). Sourcing a pipeline of transactions in partner countries is a persistent challenge and will require DFC to more regularly collaborate with in-country or country-dedicated headquarters staff of other USG agencies including USAID, the Departments of State and Commerce, the Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC), and the US Trade and Development Agency as well as with other bilateral and multilateral development finance institutions. Across USAID country offices, the loss of the in-house Development Credit Authority, which became part of DFC, is keenly felt. DFC’s Mission Transaction Unit works closely with USAID DFC liaisons at each USAID country office; collaboration at the country level would benefit from increased DFC overseas presence. DFC has legal restrictions that can prevent it from investing in certain countries or sectors where USAID can operate, such as textile investments that could have an adverse impact on US jobs.24 As a result, DFC is unlikely to extend debt or equity in some circumstances where there might otherwise be a positive development outcome, as seen in Kenya through its USAID East Africa Trade and Investment Hub.

Most foreign aid is congressionally earmarked and directed, limiting the government's flexibility on how funds are spent

Divisions in Congress and between Congress and the executive branch have resulted in less flexible funding for the Department of State, Foreign Operations, and Related Programs appropriations.25 The tighter congressional control can be explained by a desire to protect congressional prerogatives in the face of legislative gridlock26 and by the contrasting priorities of the executive and the legislative branches. The lack of alignment and mistrust has resulted in lawmakers increasingly seeking to bypass the legislative process and use other procedural means to direct foreign assistance spending in the form of harder directives, less flexibility and more requirements included in the policy instructions (Bolton, 2022[29]). This tighter control has translated into 600-700 policy instructions accompanying each of the past few fiscal years’ SFOP appropriations (USAID Office of the Inspector General, 2021[30]); the result is that effectively, more than 90% of US foreign assistance managed by USAID and/or the Department of State is either earmarked or congressionally directed funding. Although most of these policy instructions are not legally binding, it is in the executive branch’s interest for future appropriations to abide by them. In the FY 2022 Consolidated Appropriations Act, Congress continued to include a provision designating allocations set out in tables included in the policy instructions as legally required minimum amounts to be spent in the relevant country or sector27 (US Congress, 2022[31]).

The president proposes a budget that reflects the preferences of the executive branch two years before the start of the fiscal year. Agency-wide budget requests are guided by administration priorities; country-specific needs received through mission or country office resource requests; and global priorities such as the COVID-19 pandemic and climate change. USAID’s Office of Budget and Resource Management and the State Department’s Office of Foreign Assistance jointly submit a budget request to OMB, which plays an influential role in ensuring that the administration’s policy preferences and initiatives are incorporated into a proposed budget by using different levers at the budget request stage.28 One such lever is to send budget requests back to agencies with requests for adjustments to funding levels – a step known as passback (Pasachoff, 2016[32]). The president’s budget request is then sent to Congress, incorporated into a fiscal year Congressional Budget Justification for each USG agency and department.

Executive and congressional priorities do not always align, and the art of matching budget requests to actual appropriations intensifies once both chambers have passed the appropriations bill.29 Once enacted into law, a Section 653(a) report for the SFOPs – a comprehensive table that shows all country-level allocations by sector, directives, earmarks and initiatives – is sent to Congress.30 This process involves ensuring that country allocations overlaid with sector earmarks are respected. For example, a directive to spend a certain amount on a given sector or theme will have to be layered on top of country-specific earmarks even if this amount was never included in the President’s (or USAID country office’s) budget request. USAID’s Office of Budget and Resource Management and bureaus work with the State Department’s Office of Foreign Assistance and OMB to make adjustments and propose shifts to earmarks and directives allocated before the State Department and USAID submit the Section 653(a) report to Congress.31

Reconciling executive and legislative priorities with those of partner countries is complex and not helped by pre-obligation requirements and appropriations late in the fiscal year

Complex pre-obligation requirements as well as appropriations late in the fiscal year can negatively affect programme implementation by the State Department and USAID. Once the Section 653(a) report is submitted, the budget execution process begins and OMB apportions funds32 authorising the State Department and USAID to obligate funds.33 Country missions are required to provide additional information (via individual country-level congressional notifications and operating plans) explaining how funds will be used in that fiscal year and noting any divergence with the Congressional Budget Justification, including any special notification (related to budget items requiring pre-approval),34 new programmes and even implementing partners. In addition, sectoral directives can require spending plans, describing by technical area the work that is expected to be performed in each country. Moreover, for any number of technical sectors or countries, Congress occasionally includes a requirement for consultation prior to obligation. These notifications and plans are generally made six months or more into the new fiscal year. Delays can also impact localisation objectives (Localisation) and programming, given the short time span to obligate funds into new awards before the end of the period of availability of funds. Such requirements put pressure on USAID staff, especially in the offices of acquisition and assistance in country and regional offices and also in Washington, DC, where obligations are centralised.

Today, USAID is in a stronger position to advocate for country-specific needs in proposing the allocation of funds in the Section 653(a) process. The role of the State Department’s Office of Foreign Assistance has evolved since it was created in 2006, as USAID developed stronger legislative relations and built up stronger in-house systems and budget capability, most recently by reinforcing its leadership with the addition of a second deputy administrator for management and resources. The Office of Foreign Assistance, USAID’s Office of Budget and Resource Management, and the Bureau for Policy, Planning and Learning work together to make adjustments in line with the Appropriations Act across the 21 accounts (9 with USAID, 9 with the State Department, and 3 jointly managed and accounted for). In doing so, the Department of State and USAID have an opportunity to also make greater use of Integrated Country Strategies and Country Development Cooperation Strategies, which draw explicit links between US priorities and those of partner countries in justifying allocations. Further, USAID country offices are requested to provide concurrence or non-concurrence to activities that are funded through centrally programmed funds,35 strengthening USAID as the lead player in the US development co-operation system.36

Restoring trust between the executive and legislative branches is ongoing (A coherent whole-of-government policy). As a sign of more trust and less control, the FY 2022 Consolidated Appropriations Act for SFOPs has slightly less congressionally directed funding than the previous year’s appropriations act.37 This is an opportunity for USAID and the State Department to demonstrate that less-restricted funds provide the flexibility needed to meet partner country needs and contribute to better outcomes. Passing on early advice from the executive branch to congressional appropriators and allowing for more flexible programming within presidential initiatives would also show the executive branch’s goodwill. In short, USAID and the State Department have an opportunity to show that in the absence of directives, they are able to meet congressional and administration priorities and deliver results. Increasing the deviation authority (currently 10%) and extending the period of time to obligate resources,38 would allow for the USG to better respond to a country’s development needs.

Matching human resources to agency needs is a work in progress

USAID does not have a global strategic workforce plan as recommended in the 2016 peer review, and an interim plan is in effect only until the end of FY 2022. While USAID did not provide a timeline for replacing the interim plan, its new Global Development Partnership Initiative is a hiring effort to rebalance the proportion of Foreign Service officers, civil servants and contractors in its workforce. USAID is starting to recover from the 2017 hiring freeze that affected staff based in Washington, DC and has been increasing recruitment with a particular focus on enhancing its human resources in terms of gender and inclusive development, democracy and anti-corruption, global health, humanitarian assistance, climate change, and diversity, equity, inclusion and accessibility (Box 3). Conversations with members of Congress about increasing the number of direct hire (foreign and civil service) positions relative to contractors are constructive and have already led to some changes. One example is an increase in the number of civil servants hired in the new Bureau for Humanitarian Assistance, which provides technical backstopping to foreign service nationals (Being fit for fragility). The FY 2022 appropriations act recognises that USAID lacks sufficient personnel to respond to urgent needs around the world and allocates funds to support an increase in Foreign Service and civil service positions; the policy instructions, or joint explanatory statement, accompanying the act justify this increase also on the basis of USAID’s localisation objective39 (US Congress, 2022[31]) (Localisation).

As localisation becomes more of a priority, a key challenge is creating more positions of leadership for career locally hired (Foreign Service national) staff. Agency-wide, there are currently about 12 foreign service national grade 13 positions – the highest grade for career locally hired staff – and these are usually created to retain a specific person rather than systematically based on function or organisational needs. Foreign service national staff are of high quality, as several partners in both Jakarta and Nairobi confirmed, and their knowledge of the local context, culture and language is invaluable to programme success, as evidenced by the county liaison teams in Kenya that are led by foreign service nationals. The focus on localisation will require more contracting officers and better retention of experienced officers who have deep knowledge of the system. As USAID reconsiders its risk appetite to prioritise localisation, there will also be implications for its human resource needs in posts and in Washington, DC (Localisation). Foreign service nationals in USAID appear to have greater opportunities than other DAC member counterparts to go to other country missions as third country nationals or to regional hubs on detail assignment.

USAID faces some challenges in advancing a diverse, inclusive and equitable workforce. A 2020 Government Accountability Office report found that the odds of promotion in the civil service were 31 to 41% lower for racial or ethnic minorities than for whites in early- and mid-career. In the Foreign Service, average promotion rates were lower for racial or ethnic minorities in early- to mid-career, even if differences were not statistically significant when controlled for various factors. In short, the proportions of racial or ethnic minorities were generally smaller in higher ranks.

USAID acknowledges the need for a more diverse, inclusive and equitable workforce, reinforced operational and administrative roles, and an increase in the number and contribution of foreign service nationals. Progress has been made in terms of strong leadership and capacity. USAID is taking steps to meet these objectives through the following:

Strong policy commitment and leadership – The newly established Office of the Chief Diversity, Equity, Inclusion and Accessibility (DEIA) Officer, located within the administrator’s Office, works to help ensure that USAID’s programmes, people, processes, policies and practices reflect the diversity of the United States as a whole, are inclusive and consider equity in all decisions. The DEIA office works to embed DEIA principles across the agency – that is, to meet people at the local level and expand the collective space for ownership, innovation and leadership to help USAID achieve its transformative mission around the world and internally through its own workforce.

Reviewing hiring strategies and paid positions – Committed to thinking more actively about where it recruits, USAID recently reinforced efforts to diversify its candidate pool through partnership agreements at Historically Black Colleges and Universities. The agency also is considering how it might expand requirements around medical clearances, graduate-level degrees and overseas experience to better target those it refers to as “Equal Employment Opportunity Groups”. These changes would also include creating posts with work-study opportunities and providing more paid internships.

Capacity and continuous skill development – USAID launched a new Respectful, Inclusive, and Safe Environments (RISE) learning and engagement platform for staff that covers a wide range of DEIA-related content. Since June 2021, more than 6 000 USAID staff have participated in a RISE training, event or seminar. USAID now requires Foreign Service hiring managers and promotion board members to complete training on unconscious bias, and 80% of overseas posts have completed a five-day intercultural competence, diversity, equity, inclusion and accessibility workshop.

Expanding and diversifying partnerships – WorkwithUSAID.org, which USAID launched in November 2021, serves as a free resource hub that provides the knowledge and networks to help organisations work with USAID.

Well-supported country systems – USAID recognises that DEIA is contextual and varies from place to place. In Kenya, a DEIA regional co-ordinator is working with mission leadership, the DEIA Council and the staff association to help identify gaps and barriers to equity and inclusion and meet the DEIA objective.

Note: This practice is documented in more detail on the Development Co-operation TIPs • Tools Insights Practices platform at www.oecd.org/development-cooperation-learning/practices/towards-a-more-diverse-equitable-inclusive-and-accessible-workforce-at-usaid-6f2ddfc5. The FY 2022 Consolidated Appropriations Act requires USAID to develop “workforce diversity initiatives and a staffing report on the onboard personnel levels, hiring, and attrition of the Civil Service, Foreign Service, and Foreign Service National workforce of USAID for each operating unit” and to report progress to appropriations committees in Congress every quarter until 30 September 2023.

Source: US Congress (2022[31]), “Division K – Department of State, Foreign Operations, and Related Programs Appropriations Act, 2022”, www.congress.gov/117/crec/2022/03/09/168/42/CREC-2022-03-09-bk4.pdf; US Government Accountability Office (2020[33]), USAID: Mixed Progress in Increasing Diversity, and Actions Needed to Consistently Meet EEO Requirements, www.gao.gov/products/gao-20-477.

Operational bottlenecks in mission hiring arrangements jeopardise quality country programmes. Kenya offers an illustration. While the number of USAID staff has increased substantially in recent years, 100 of the current 380 posts are vacant. Although locally engaged staff are the bedrock of a country office and many programmes, it can take as long as one year to hire such staff under personal service contracts that are more like procurement contracts for goods and services than for human resources.40 In addition, once a post is occupied, career progression is impossible without a reclassification of posts that requires an entirely new recruitment process, further threatening programme delivery. While country offices have a certain amount of leeway in deciding the percentage of programme costs that can fund administrative and staffing, operational bottlenecks tend to impair this flexibility.

The United States is committed to using evidence but could enhance learning through strategic evaluation and sharing knowledge across interagency members

The United States has in place robust evaluations as well as strong collaboration, learning and accountability mechanisms with built-in pause and reflect moments. The Foundations for Evidence-Based Policymaking Act of 2018, which builds on the 2010 Government Performance and Results Act Modernization Act, requires federal agencies to evaluate the impact of programmes; increase the use of data, evidence and evaluation in the policy-making process; and make data accessible to the public. USAID and other agencies have access to a strong evidence base that informs US strategies, programmes and activities. Data are generated for both accountability purposes and for learning and based primarily on monitoring of results and evaluation of performance at project and programme levels. In USAID, strategic collaboration, continuous learning and adaptive management link all components of the programme cycle. Taking the time to pause and reflect is an essential Collaborating, Learning and Adapting (CLA) practice (Box 4).

Learning is important for USAID. To improve the effectiveness of US development co-operation, USAID is making CLA practices more systematic and intentional throughout the programme cycle and dedicates resources to help staff apply them. Each of the three stages involves the following:

Strategic collaboration – USAID and stakeholders identify shared interests and work together, reducing duplication of effort and sharing knowledge.

Continuous learning – USAID and stakeholders use data from monitoring, portfolio reviews, research, evaluations and analyses to reflect on implementation. Pause and reflect moments catalyse learning.

Adaptive management – USAID and partners apply learning and make adjustments during implementation. Adaptive management is particularly important in less stable and transitional contexts.

USAID’s CLA Toolkit helps staff understand CLA, make it systematic and intentional, and ensure that there are the necessary resources to support it. It guides practitioners as they identify learning questions; consider potential collaborators and areas of co-operation; determine how data and knowledge inform decision making; and know when to adapt and how to help others to do likewise. It also helps with approaches to capturing, distilling and sharing knowledge across individuals, teams and programmes.

Annual portfolio reviews and midterm Country Development Cooperation Strategy stocktaking complement each USAID country office’s ongoing CLA activity. These aim to guide course correction, revisit assumptions and inform future planning at the country level.

More effort could be made to reach across to other US government agencies to collaborate, learn and adapt, drawing lessons from foreign assistance successes and failures and building on good examples from USAID.

USAID’s new, elevated and expanded post of chief economist and greater use of strategic evaluation could deliver insights on the extent to which programmes are achieving their goals and also inform improvements. Strategic dialogues with key stakeholders led by USAID’s chief economist and backed by a new Office of Behavioral Science and Experimental Economics will look at ways in which USAID programmes can be strengthened to better meet development objectives. Since evaluations are decentralised to country offices and headquarters units in USAID, these tend to be mostly context specific. Together with monitoring, activity-level evaluations, and evaluations of sector, thematic, country and regional programmes, the new dialogues can generate information about achievement of broader goals. Learning from the different types of evaluations would also facilitate improvement beyond individual teams and units within agencies.

4. Building on strong leadership and substantial additional ODA contributions the United States has made in response to the COVID-19 pandemic and multiple crises, the United States should:

5. As it re-engages multilaterally, the United States should outline an approach that drives greater coherence, clarity and transparency on how and when the United States decides to use multilateral channels and on the advantages of doing so, especially given the increased resources and the number of government actors involved.

6. To increase discretion and flexibility in future foreign assistance appropriations and better align to partner country needs to reduce poverty, USAID and the State Department should hold more strategic-level dialogue with the Congress about the results and impacts of its strategies and programmes.

7. USAID should have a medium-term workforce plan or strategy guiding its significant hiring and on-boarding effort to rebalance the ratio of Foreign Service officers, civil servants and contractors in its workforce. It should also work to further increase the number of locally hired staff in line with diversity, inclusion, equity and accessibility objectives.

8. The United States International Development Finance Corporation should have a clear roadmap for delivering new financial tools including equity instruments, reinforce its human resources in partner countries, and work more in partnership with the United States government and other partners.

The United States has strong foundations for localisation, but needs clarity of purpose to support the ambitious vision

The United States has a long history of trying to localise its development assistance to increase ownership and sustainability, with varying success. Local Solutions, a component of the USAID Forward reform initiative introduced in 2010 under the Obama administration, established a goal of awarding 30% of US assistance to local organisations and partner countries (USAID Office of the Inspector General, 2019[34]). This was followed by the Journey to Self-Reliance under the Trump administration. The 2018 Acquisition and Assistance Strategy, and the subsequent introduction of the New Partnerships Initiative were developed to help address some of the internal constraints to diversifying the entities with whom the agency partners.41 These efforts have left both a legacy cadre of staff who have been involved in localisation initiatives and lessons to systematically draw upon (USAID, 2021[35]). Progress has been made but slowly, in the face of bureaucratic hurdles and regulatory and statutory requirements, competing priorities, measurement challenges, and special interest resistance (Steiger, Maloney and Runde, 2021[36]; USAID Office of the Inspector General, 2020[37]; Government of the United States, 2022[12]). Beyond USAID, there are strong traditions of community-driven and locally led development in the Peace Corps, the Inter-American Foundation and the African Development Foundation.

The new approach to localisation reflects both continuity of these efforts as well as significant changes in ambition and direction. USAID Administrator Power builds on the past in her vision for global development, which includes a commitment to allocate 25% of funding to local organisations within four years, including by building on metrics of previous efforts (USAID, 2021[6]; Ingram et al., 2022[38]).The vision is also a shift in emphasis, seeking to address the power dynamics within development co-operation, reach the most marginalised populations and put people at the centre of the development process. As USAID Administrator Power stated in November 2021, at least 50% of USAID assistance by the end of the decade “will need to place local communities in the lead to either co-design a project, set priorities, drive implementation, or evaluate the impact of our programs” (USAID, 2021[6]). USAID is in the process of setting out how to implement the administrator’s commitment.

Creating a shared understanding of localisation within USAID, the wider interagency and with partners will be essential for driving effective, co-ordinated action. Drawing on lessons from prior reforms and ensuring that there are manageable and clearly signposted initiatives and common metrics with simple, clear and consistent direction will be critical to successful implementation of the new vision (USAID Office of the Inspector General, 2020[37]; King, Garber and Hirschfeld, 2022[39]). There is political willingness to support localisation, including on the part of private sector contractors and the wider civil society, as well as bipartisan support in Congress (Cooley, Gilson and Ahluwalia, 2021[40]; Ingram et al., 2022[38]). As yet, however, there is no unified definition of localisation and its constituent parts that is shared across the US interagency and understood externally. Rather than an end in itself, localisation is a process that helps to address power imbalances, enhance equity in programming and expand the number of non-traditional partners from underserved communities and craft development efforts so that their outcomes are ultimately sustained by local people with local resources (Government of the United States, 2022[12]). It will be important to develop a clear theory of change for what a shift to localisation brings in terms of sustainability and development impact across a variety of contexts, including authoritarian ones. For agencies that seek to localise more, this clarity could help them partner with other US government agencies with complementary development models that are already localised such as the Inter-American Foundation, the United States African Development Foundation, PEPFAR and the Peace Corps.

Increasing local partner funding needs to be context specific and supported by a coherent strategy

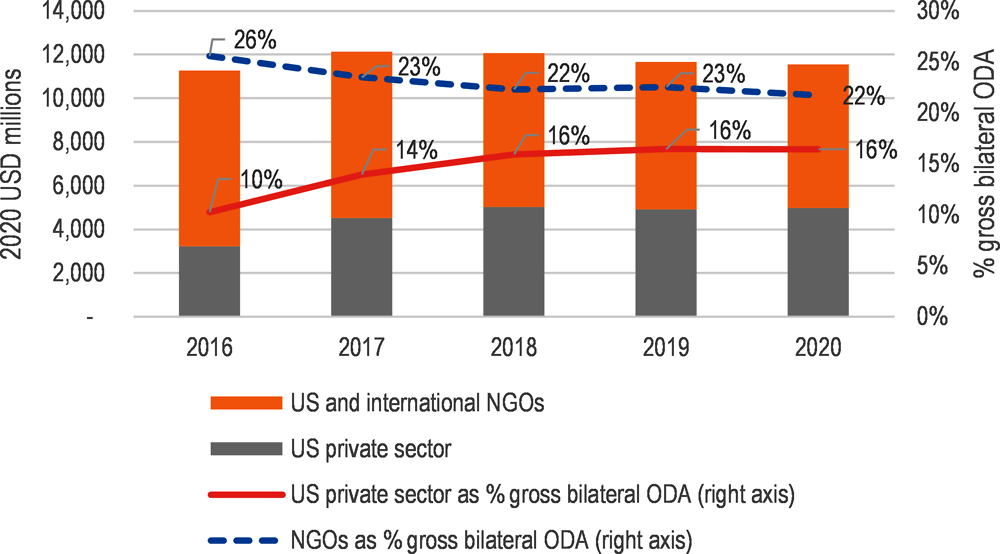

Defining a local partner will be important for determining what counts as localisation. USAID’s aim to have 25% of funding delivered directly to local partners requires a clear, agreed definition of a local partner. US assistance delivered through CSOs amounted to USD 6.6 billion,42 or nearly 22% of gross bilateral ODA in 2020, a proportion that has been broadly constant for the last five years (Figure 2). However, almost none was delivered through developing country CSOs, according to OECD Creditor Reporting System (CRS) data (OECD, 2022[41]). USAID guidance on grants and contracts provides different qualifying criteria in definitions of local entities and locally established partners that include local offices of international NGOs or locally registered companies,43 or in other guidance. The definitions matter, as they will feed into the metrics of success and shape the nature of USAID’s localisation approach (USAID Office of the Inspector General, 2021[42]).