Executive summary

The COVID-19 pandemic hit the economy hard, provoking a marked downturn. The economy is recovering, supported by macroeconomic policies and progress in addressing infections.

Infections proved difficult to bring under control. The government reacted to waves of infections by introducing confinement measures, which with behavioural changes kept infection rates relatively low. However, pressure on the health service was intense in some parts of the country. Vaccination started relatively slowly, but by mid-year the pace had picked up substantially.

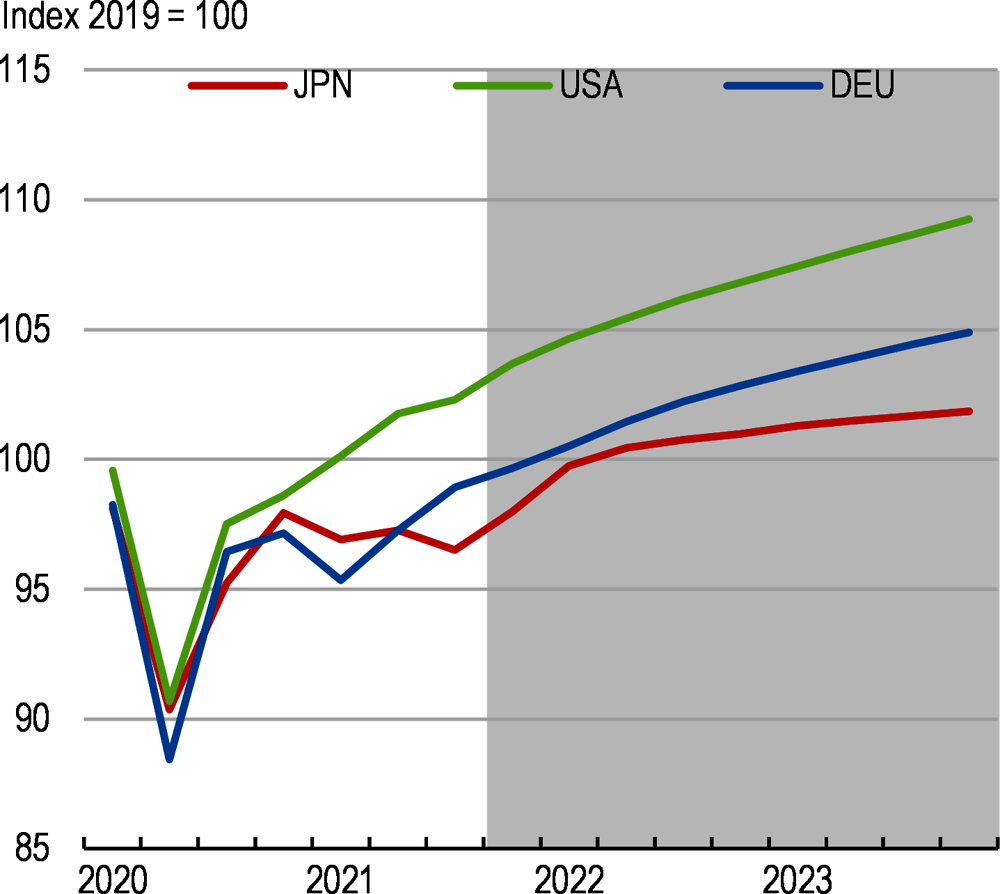

Output dropped and the recovery has been relatively modest. Economic activity tumbled in Spring 2020 as sanitary restrictions restrained consumption and investment. Government support and the reopening of the economy led to a partial bounce back, but difficulties in containing infections held back growth in the first half of 2021 (Figure 1). Employment contracted sharply and weak wage growth depressed household income.

Growth is on course to regain momentum. As sanitary conditions improve and vaccination coverage increases, the economy is set to strengthen (Table 1). Private consumption growth will remain subdued given sluggish wages. Exports rebounded as major trading partners recovered and are set to remain firm. The recovery in industrial production coupled with government support will lift investment. A weak recovery and temporary downward pressures on prices will likely keep inflation below target for some time.

Risks remain sizeable. Vaccinations are making progress, but losing the race against new variants could result in renewed states of emergency being declared delaying the recovery. This would aggravate scarring effects, particularly if the current cohort fails to make a successful transition from school and university into employment.

Macroeconomic policies are supportive and stimulus will become more targeted and withdrawn once the economy has emerged from the pandemic.

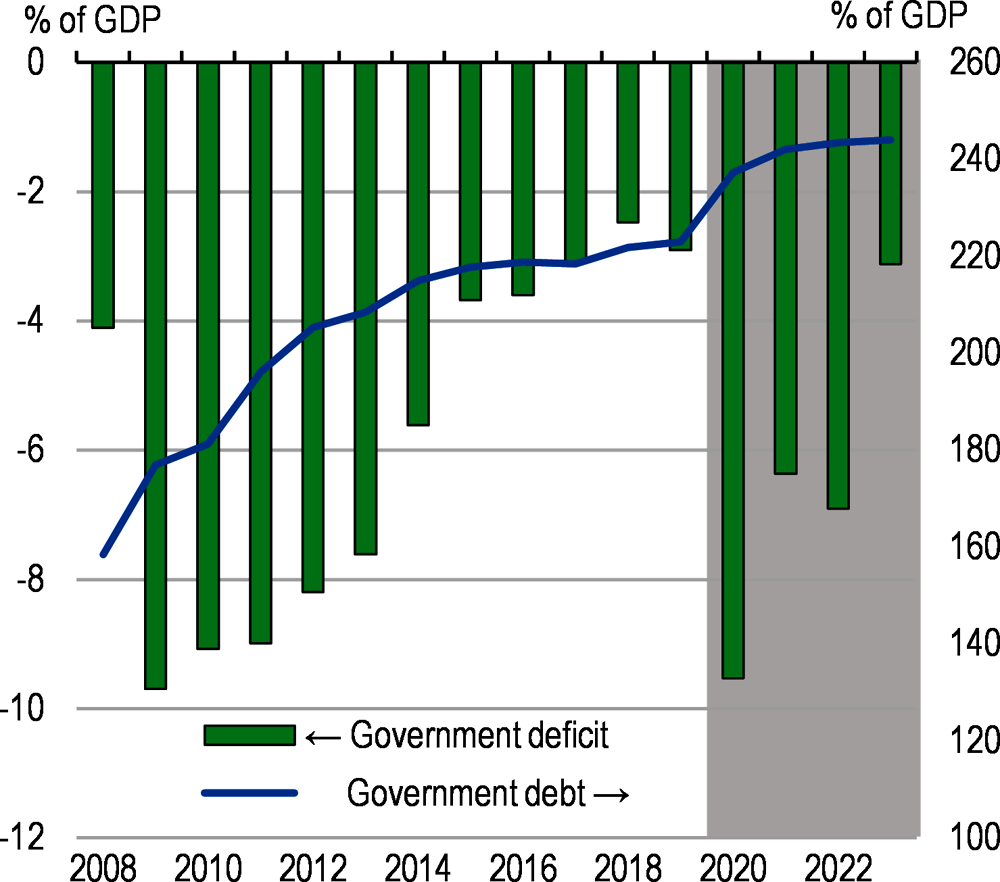

Fiscal policy reacted robustly. A variety of measures supported households and businesses affected by the pandemic, notably the Employment Adjustment Subsidy, cash benefits for SMEs and concessional loans. These measures successfully kept unemployment low and prevented widespread firm failure while containing the spread of infection. In addition, new economic measures, which focus on growth and distribution, were adopted after a new administration was formed in October 2021. However, they led to a ballooning budget deficit in 2020, pushing up debt to unprecedented highs (Figure 2). As the economy regains momentum, fiscal policy is rebalancing towards more targeted policies that will both underpin domestic demand and improve productivity or meet environmental targets.

Monetary policy has been supportive. The Bank of Japan reacted quickly, ensuring that monetary and financial policy was supportive and provided ample liquidity to stabilise markets and support for lending. The impact of the pandemic and one-off price reductions and subsidies led CPI inflation into negative territory before it picked up to around zero. Inflation is projected to increase gradually but remain below target for the foreseeable future. In these conditions, monetary policy will remain accommodative.

Financial vulnerabilities are largely structural. Bank lending rose rapidly during the pandemic as firms’ needs for working capital surged. The banking sector appears reasonably well capitalised and able to withstand further shocks. Some of the pandemic-induced lending is backed by government schemes. However, regional banks appear weaker and have been struggling in recent years. Efforts to restructure and merge these banks will strengthen overall financial sector resilience.

A combination of fiscal consolidation and structural reforms will be needed to ensure long-run sustainability. Policies that raise productivity growth, boost labour force participation, and allow for gains in public spending efficiency would help bring debt levels down to more manageable levels by mid-century.

Fiscal consolidation was knocked off course. The deterioration of the budget comes after a period of sustained reductions in primary deficits. As the economy regains traction, further action will be needed to secure long-term fiscal sustainability.

Social security spending and ageing-related spending for health and long-term care are rising. Gross government debt is set to rise further GDP by 2050 without corrective action. Consolidation efforts that raise additional revenue by increasing the consumption and carbon tax rates gradually would help stabilise debt in the medium term, but underlying spending pressures would then see debt levels rising once again.

Past labour market reforms have successfully raised employment, more than offsetting ageing’s impact on the size of the working-age population. But the pandemic has set this progress back and helping workers into employment would minimise scarring effects. Employment and wellbeing could be raised further by reducing labour market dualism. Planned reforms to pensions would help in this respect. Labour supply could also be lifted by reducing disincentives in pension and health insurance for spouses.

Productivity in the business sector has been sluggish, particularly in business services and smaller firms. Business dynamism, which spurs productivity gains by encouraging firm entry and subsequent growth and the exit of less productive firms, is weak compared with other countries. The structure of support for SMEs and personal bankruptcy rules act as impediments in this regard.

Environmental policy objectives have become more ambitious. The government has committed to a target of net zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050 and an intermediate target for 2030. Meeting these objectives will be challenging. Renewables’ contribution to electricity supply is modest in comparison with other countries and is constrained by limited integration of regional power grids. Other potential contributions from innovative technologies, such as hydrogen and ammonia and carbon capture and storage are still nascent and relatively expensive. Thus far, limited use has been made of market-based instruments. A carbon tax is in use, but the rate is rather low. That said, energy costs are relatively high.

Pursuing the digital transformation may also help boost productivity growth and secure fiscal sustainability. The country is well placed to benefit from digitalisation, enjoying good infrastructure and skills, though complementary investments are also needed.

The physical infrastructure is good and skills are elevated. In addition, firms are world leaders in digital technologies and students rank well in international comparisons of skills. However, the pandemic revealed weaknesses as households, firms and government struggled to make use of digital technologies. Complementary investments would help harness the full power of digitalisation.

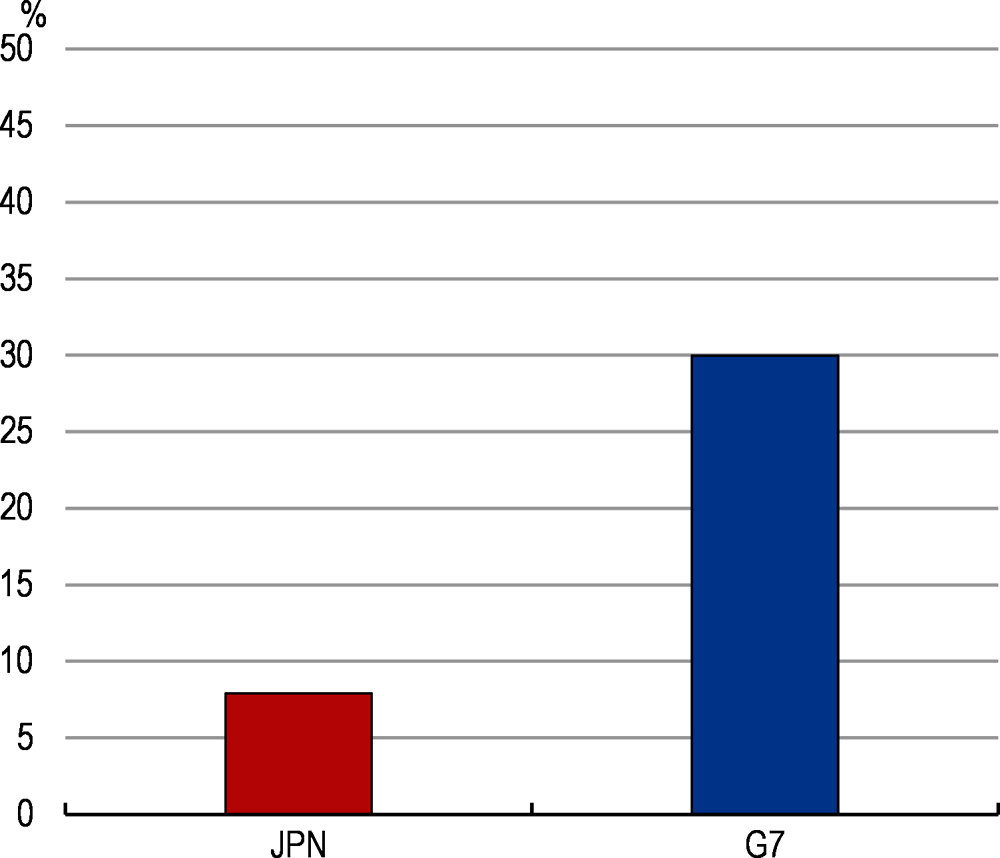

While the foundations are in place, government use of digital tools is limited. The government has made progress in developing competency and digital tools. However, the use of these government services remains comparatively low. Reliance on paper and even stamps remains widespread (Figure 3). The recent initiative to establish a Digital Agency in the centre of government will help create impetus for other parts of government.

Digitalisation can boost public service provision. Experience in trials and differences in the adoption of digital tools across the country suggest that gains in public spending efficiency are available in diverse areas such as health and long-term care, transportation and public investment. Better tailored services can be provided and transaction costs reduced markedly by making better use of digital information and technologies.

Private sector digitalisation is mixed. In some sectors, notably manufacturing, digitalisation is amongst the most advanced worldwide, but there are wide variations elsewhere with business services and smaller enterprises often being less well placed.

Investment in complementary and intangible assets is often lacking. Investment in ICT technologies and the intangible assets to make best use of new technologies is very concentrated. Weak business dynamism hinders the diffusion of new technologies and management methods.

Digitalisation is changing skill needs. The school system performs well in many areas, but digital skills are weaker. In part, schools have lacked the investments and training to incorporate new technology into their curricula. At university level, relatively few students study STEM disciplines, particularly women.

Retraining workers becomes more important in an era of disruptive change. As the share of non-standard employment has risen, ensuring training needs are met becomes more difficult. Government support for adult and continuing training, together with promoting more mid-career labour mobility, would help raise incentives for individuals to invest in training.