2. Leveraging on e-procurement to increase efficiency and transparency of public procurement

This chapter focuses on analysing the e-procurement system of the State of Mexico, COMPRAMEX. E-procurement contributes to increased efficiency and transparency of public procurement procedures. COMPRAMEX has not led to remarkable achievements since 2013 when the public procurement law was enacted to advance the e-procurement agenda. The chapter assesses the current functions of COMPRAMEX from the viewpoint of efficiency. It also reviews the extent to which COMPRAMEX contributes to increasing transparency through publishing information related to public procurement in terms of coverage, quality and user-friendliness. Then, the chapter discusses the five key elements that the State of Mexico should take into account for the successful implementation of e-procurement reform: institutional leadership, stakeholder engagement, technical functionality, governance and capacity building. The chapter will provide recommendations and a roadmap on how to transform COMPRAMEX into a more comprehensive, transactional, interconnected and transparent e-procurement system with reusable and comprehensible data.

Countries have increasingly been harnessing digital technologies to achieve better outcomes and deliver services more effectively and efficiently. E-procurement refers to the integration of digital technologies in the replacement or redesign of paper-based procedures throughout the procurement process. (OECD, 2015[1]) It is an effective tool to ensure efficiency and transparency of public procurement processes. Indeed, the OECD Recommendation of the Council on Public Procurement calls upon countries to improve the public procurement system through the use of digital technologies to support appropriate e-procurement innovations along the entire procurement cycle.

E-procurement can significantly increase efficiency of public procurement procedures by eliminating paper-based processes that bear a high administrative burden. Decrease in administrative burdens stimulates greater competition in public procurement and delivers better procurement outcomes (lower prices and better quality). For example, European countries that made the transition to e-procurement as of 2016 reported savings between 5% and 20% (European Commission, 2016[2]).

In addition, e-procurement systems allow governments to increase the transparency of public procurement activities, as well as to collect consistent, up-to-date and reliable data. Transparency leads to making governments more accountable and gaining citizen trust.

E-procurement also promotes integrity in procurement processes by increasing traceability and strengthening internal controls that ease the detection of integrity breaches. It also reduces corruption opportunities by preventing unnecessary physical contact between prospective suppliers and public servants during the tender process (OECD, 2016[3]).

In 2013, the State of Mexico enacted the Public Procurement Law of the State of Mexico and Municipalities (Ley de Contratación Pública del Estado de México y Municipios, LCPEMyM). This Law aims to, as its principal objective, facilitate the digitalisation of public procurement procedures through the gradual introduction of COMPRAMEX, the e-procurement system of the State of Mexico. However, COMPRAMEX reform has not marked a consequential improvement. The State of Mexico has never carried out electronic modalities using COMPRAMEX due to its limited transactional functions such as the lack of an e-submission function. Therefore, all tender processes in the State of Mexico are still carried out on a paper-basis modality.

Under the current fiscal constraints, the State of Mexico needs to focus on using public funds in an efficient manner. Therefore, e-procurement could be positioned as one of the measures to deal with this situation through making the public procurement process more efficient and transparent. Currently, the State of Mexico has a reform plan to update COMPRAMEX by the end of 2020 by making its transactional systems more comprehensive but there are no clear roadmaps to implement this reform. The current climate could constitute a driving force for the State of Mexico to show a strong institutional commitment by advancing its e-procurement reform that stagnated since the legislative framework on e-procurement was reformed in 2013.

This chapter will start by assessing the current state of play of COMPRAMEX as a tool to increase efficiency and transparency of public procurement system. It highlights that the COMPRAMEX reform has not achieved significant progress since 2013, in spite of the regulatory requirement by the LCPEMyM. Then, the chapter discusses the five key elements that the State of Mexico should take into account for the successful implementation of the e-procurement reform: institutional leadership, stakeholder engagements, technical functionality, governance, and capacity building. Lastly, the chapter provides a roadmap on how to transform COMPRAMEX into a more comprehensive transactional, interconnected, and transparent e-procurement system.

VIII. RECOMMENDS that Adherents improve the public procurement system by harnessing the use of digital technologies to support appropriate e-procurement innovations throughout the procurement cycle.

To this end, Adherents should:

i. Employ recent digital technology developments that allow integrated e-procurement solutions covering the procurement cycle. Information and communication technologies should be used in public procurement to ensure transparency and access to public tenders, increasing competition, simplifying processes for contract award and management, driving cost savings and integrating public procurement and public finance information.

ii. Pursue state-of-the-art e-procurement tools that are modular, flexible, scalable and secure, in order to assure business continuity, privacy and integrity, provide fair treatment and protect sensitive data, while supplying the core capabilities and functions that allow business innovation. E-procurement tools should be simple to use and appropriate for their purpose, and consistent across procurement agencies, to the extent possible; excessively complicated systems could create implementation risks and challenges for new entrants or small and medium enterprises

Source: (OECD, 2015[1])

2.1.1. COMPRAMEX reform has not witnessed a remarkable achievement since 2013 regardless of the regulatory requirements. In order to increase efficiency, the State of Mexico could digitalise the procurement cycle by implementing functionalities aligned with regulatory requirements

E-procurement systems increase efficiency in public procurement by introducing standardisation, streamlining and integration of processes and result in better value for money in the use of public funds. E-procurement can increase competition in the market, thus reducing the prices paid by government, which can yield between 5% and 25% in cost savings (The Asian Development Bank, 2004[4]).

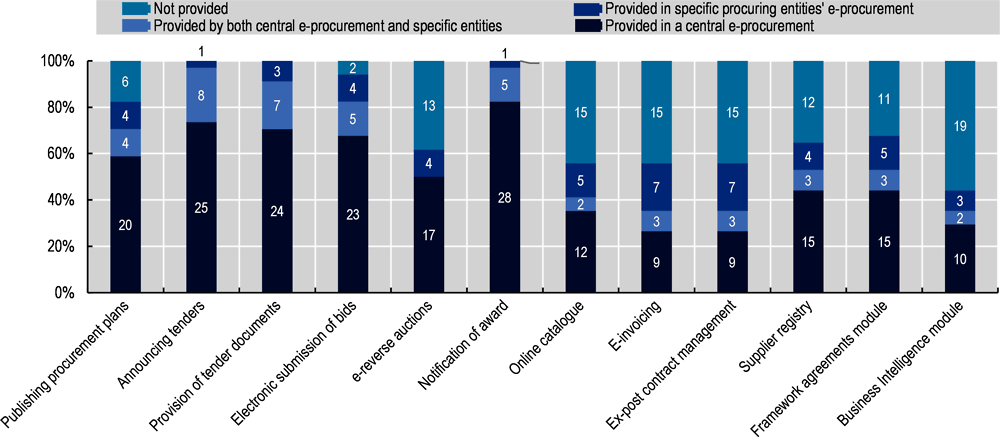

Recognising the benefits of e-procurement in increasing efficiency in public procurement processes, OECD countries have gradually been expanding functionalities of e-procurement systems to shift from platforms providing procurement information to more transactional systems.

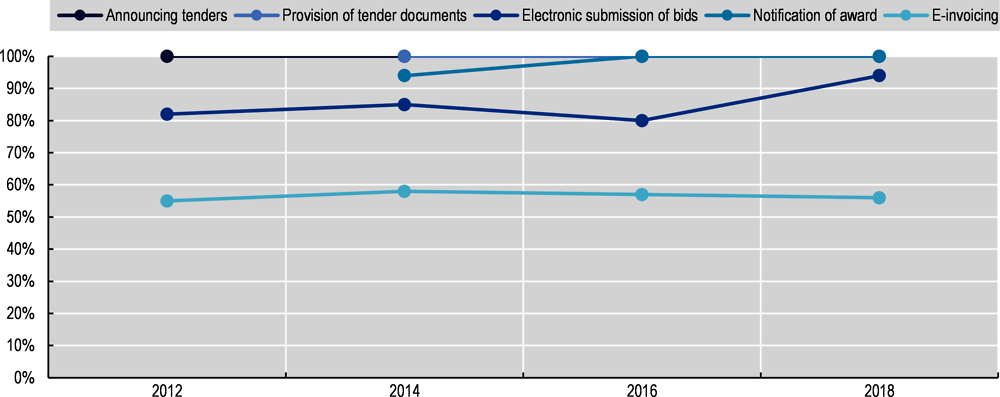

The Figure 2.1 shows the evolution of functionalities of e-procurement systems in OECD countries from 2012 to 2018. All OECD countries published tender announcements as of 2012, provided tender documents as of 2014, and carried out award notification as of 2016 in their e-procurement systems. Of all OECD countries, 82% had already put e-submission in place in 2012 and this rate increased to 94% in 2018. On the other hand, the introduction of e-invoicing has stagnated at around 55% with little progress between 2012 and 2018.

In 2018, almost all OECD countries had transactional systems during the pre-tender and tender phases, such as publishing procurement plans, announcing tender notices, providing tender documents, electronic submission of bids, and notification of award, while the transactional functions during the post-tender phase (or contract execution period) were still limited, for example, in e-invoicing and contract management.

The State of Mexico has been taking initiatives to digitalise procurement processes. Indeed, advancing the e-procurement agenda was one of the principal purposes for the enactment of the Public Procurement Law of the State of Mexico and Municipalities (Ley de Contratación Pública del Estado de México y Municipios, LCPEMyM) in 2013. It intended to facilitate the digitalisation of public procurement procedures through the gradual introduction of e-procurement contributing to increased transparency and efficiency in order to bring the maximum benefits to the State of Mexico citizens.

Article 3, bullet I, of the LCPEMyM defines COMPRAMEX as the e-procurement system of the State of Mexico. Article 18 stipulates that COMPRAMEX shall be preferably used to carry out public procurement procedures for goods and services which are financed by state resources partially or totally. This principle also applies to municipalities.

COMPRAMEX aims at reducing costs of procurement procedures for both contracting authorities and suppliers, controlling public expenditures and achieving the maximum efficiency and transparency. (Article 19). Indeed, the introduction of COMPRAMEX is supposed to contribute to modernising the public procurement system and to increasing citizen participation in the procurement processes. The strategic use of COMPRAMEX aims not only to achieve more transparent procedures, but also increase competition through promoting the participation of more suppliers in public procurement processes and facilitating data collection to carry out evidence-based strategies.

Article 11 of the Bylaws of the LCPEMyM (Reglamento de la Ley de Contratación Pública del Estado de México y Municipios) states that the Ministry of Finance is in charge of developing and administering COMPRAMEX. Currently, the website of COMPRAMEX provides the following components:

Information on each individual procurement procedure (tender notice, tender documents, minutes of tender opening, contract award decision, and contract documents)

COMPRAMEX publishes the annual procurement programme of all the public entities of the State of Mexico including municipalities, although some entities do not fulfil the obligation of publishing it in COMPRAMEX. It also allows for the supplier online registration in order to reap its benefit to decrease administrative burdens and costs. For example, ChileProveedores, an advanced platform for supplier registration developed in Chile, reduced transaction costs by 50% (Shakya, 2017[9]). Furthermore, SICAPEM-PMCP (Sistema Integral de Contratación y Administración Patrimonial del Estado de México-Plataforma Mexiquense de Contratación Pública), the internal system of COMPRAMEX, facilitates the process of market research and financial management of contracts. COMPRAMEX also functions as a transparency portal of public procurement which publishes information on each individual public procurement procedure such as tender notices, tender documents, the minutes of a tender opening, contract award decision, and contract documents. This will be discussed further in the next section relative to access to information.

However, COMPRAMEX reform has not achieved the results foreseen by the LCPEMyM: the use of COMPRAMEX in public procurement processes remains very limited. Article 28 of the LCPEMyM defines three modalities of open tender in accordance with the means used:

Face-to-face (paper-basis), in which bidders submit their proposals exclusively on a paper basis in a sealed envelope, during the tender opening or by mail if specified in the tender notice. Under this modality, the clarification meetings and tender opening will be carried out in person and bidders must participate in these sessions.

Electronic (e-procurement), in which tender processes are carried out exclusively through COMPRAMEX. Under this modality, clarification meetings, tender opening, and contract award notification are carried out through COMPRAMEX, without the physical presence of bidders.

Mixed, in which bidders may choose whether to participate in person or electronically in clarification meetings, tender opening and contract award notification.

Although the Law foresees these three modalities, all the tender processes in the State of Mexico have been carried out in the paper-basis modality. In other words, the State of Mexico has never carried out electronic or mixed modalities through COMPRAMEX.

This situation is attributed to the limited transactional functions of COMPRAMEX. It only allows for the publication of tender notices and bidding documents, although LCPEMyM and its Regulations require that COMPRAMEX publishes tender notices, tender documents, minutes of the tender opening, contract award decision, contract documents, and when applicable the minutes of clarification meetings. Table 2.1 summarises the functionalities of COMPRAMEX.

The Law also foresees e-submission (Article 36) and e-signature (Article 65). It requires that the bids (technical and financial proposals) be submitted in an electronic format when the procurement procedures are carried out through COMPRAMEX meaning that contracts can be signed with electronic signature. However, these functions are still under development and not currently available in COMPRAMEX, which causes a discrepancy between the requirements of the regulatory framework and the actual situation.

In particular, e-submission of bids is a critical element to increase competition of public procurement through increasing the number of bid proposals, which is the central topic discussed in Chapter 5. E-submission allows bidders from outside the State of Mexico, such as Mexico City or even foreign companies, to participate in the tender process. In fact, almost all OECD members have an e-submission function in their e-procurement systems at a certain level of government.

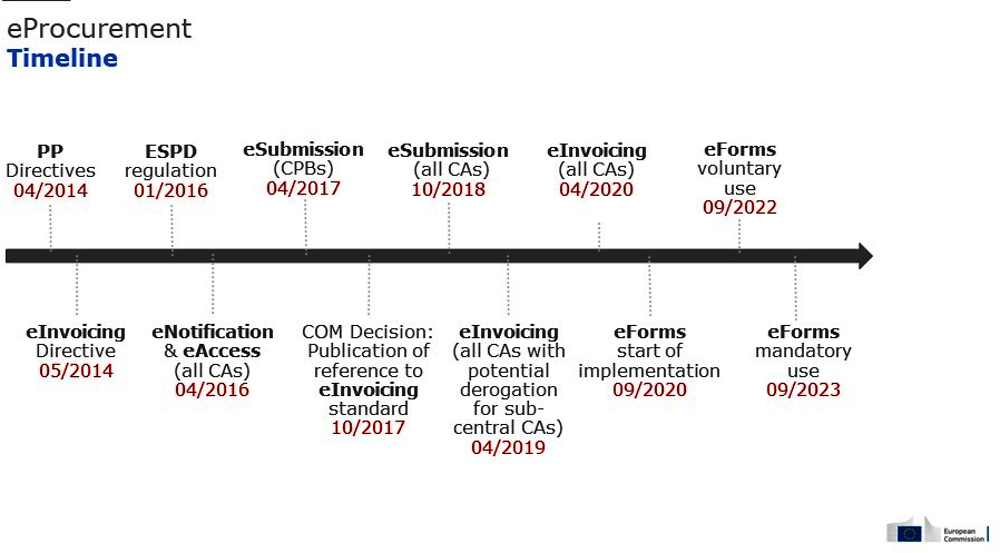

The European Commission developed an initiative to support the transition to an e-procurement system that covers the whole public procurement cycle for all European Union (EU) member countries. This initiative also includes mandatory e-submission of bids (See Box 2.2).

In preparation for the digital transformation of public procurement, the EU developed a phased nine-year (2014 - 2023) public procurement reform to introduce a compulsory and fully transactional e-procurement tool, including modules on e-invoicing, e-notification, e-access, e-submission and other e-forms, as well as a comprehensive reform to public procurement directives.

According to the guidelines published by the European Commission in 2014, the EU supports the process of rethinking public procurement process with digital technologies in mind. This goes beyond simply moving to electronic tools; it rethinks various pre-award and post-award phases. The aim is to make them simpler for businesses to participate in and for the public sector to manage. It also allows for the integration of data-based approaches at various stages of the procurement process.

According to the EU, digital government is one of the key drivers toward the implementation of the ‘once-only principle’ in public administrations – a cornerstone of the EU’s Digital Single Market strategy. And with the adoption of digital tools, public spending should become more transparent, evidence-oriented, optimised, streamlined and integrated with market conditions. This puts e-procurement at the heart of other changes introduced to public procurement in new EU directives and introduces the notion that in the age of big data, digital procurement is crucial in enabling governments to make data-driven decisions about public spending.

In order to achieve this goal, the new rules on e-procurement in the EU are to be gradually introduced with the following timeline:

In the Latin America and Caribbean region, e-procurement facilitated the e-submission function in 13 out of 19 countries surveyed as of 2016: Mexico, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, Guatemala, Jamaica, Panama, Peru, El Salvador and Uruguay.

CompraNet, the e-procurement system of the Federal Government of Mexico, has provided the e-submission function since 2000. (See Box 2.3) However, e-submission is not mandatory for federal government procurement. Contracting authorities can choose whether to allow electronic submissions, because the Federal Law on Public Sector Acquisitions, Leases and Services (Ley de Adquisiciones, Arrendamientos y Servicios del Sector Público, LAASSP) also foresees the three modalities: Face-to-face (paper-basis), electronic, and mixed. However, there has been a remarkable increase in the use of e-submission from 16% in 2012 to 43% in 2019.

In 2019, 43% of all the public procurement procedures at the federal government level applied the electronic modality, which uses e-submission through CompraNet, in addition to 12% for mixed modality, which might have used e-submission. This implies that at least 43% and up to a maximum of 55% of the tender procedures at the federal level applied e-submission in 2019 (CompraNet, 2019[12]).

This data from the Federal Government also demonstrates that it takes a lot of time to transform procurement practices from paper-based to electronic. Therefore, it is all the more urgent that the State of Mexico takes immediate actions to develop such functionality.

Since its official launch in 1996, CompraNet has evolved in its transactional functions. The most significant features of each version were as follows:

CompraNet 1.0 (1996): module to publish tender notices and disclose contract award decisions

CompraNet 2.0 (1997): access to bidding documents, upon receipt of a bank slip to prove payment of fees related to federal legal rights

CompraNet 3.0 (2000): electronic submission of bid proposals and contract award notices

CompraNet Plus 4.0 (2007): 4.0 never replaced CompraNet 3.0 because it ran into performance issues. After six months, the pilot implementation project was cancelled

CompraNet 5.0 (2010): Version 5.0 provides a wide variety of functions:

loading of documents related to non-open tender activity, such as closed tenders (restricted invitations) and direct awards, both permissible by law under certain circumstances

execution of various forms of e-auction, including English/reverse and Dutch auctions

traceability of user activities, such as loading and accessing documents

development of a supplier registry, against which government buyers can provide ratings (on a 0-100 scale) to record contract compliance

dissemination of documents such as minutes of clarification meetings, reports by social witnesses, executed contracts and any variations or modifications

Source: (OECD, 2018[13])

During the fact-finding mission, contracting authorities stated that all the procurement procedures should be digitalised in the State of Mexico, although there is no clear timeline or implementation plan to achieve this. Some contracting authorities shared their experiences of having received more bid proposals when they allowed for e-submission through CompraNet for their federal-funded procurement procedures. Recognising the benefit of e-submission in increasing competition through more bid offers, they restated the importance of developing the e-submission function for COMPRAMEX, to come in line with CompraNet.

The automatic notification of tender opportunities to suppliers is another function that contracting authorities raised in order to increase efficiency of public procurement. Currently, COMPRAMEX does not provide an automatic notification of tender opportunities to suppliers. Therefore, each supplier needs to check the website COMPRAMEX regularly to know whether or not there are tender notices which match their interests. In some cases, suppliers miss the tender opportunities that might match their areas. This situation leads to inefficiency and decreases the level of competition in public procurement. The automatic notification system is available not only in CompraNet but also in Tianguis Digital, the e-procurement platform of Mexico City, which implies that this function is becoming a standard e-procurement function in Mexico.

Currently, the State of Mexico has a reform plan to update COMPRAMEX by the end of 2020 by making transactional systems more comprehensive, providing new functions including e-submission and e-signature, in accordance with the LCPEMyM. The State of Mexico will also benefit from the introduction of an automatic notification system of tender opportunities to suppliers. In the medium and long term, the State of Mexico could consider the possibility of adding more advanced functions such as organising clarification meetings and tender opening meetings in a virtual way through COMPRAMEX, submission of invoices by suppliers and payment procedures.

It is also worth stating that article 33 of the LCPEMyM stipulates that tender notices of open tenders have to be published not only in newspapers but also in COMPRAMEX. This applies to all of the three modalities, including the paper-based modality. However, not all public entities comply with this obligation. This applies equally to the submission of the annual procurement programme. The State of Mexico should ensure that all the public entities in the State of Mexico publish their tender notices and the annual procurement programmes in COMPRAMEX, in accordance with legal requirements.

Implementing the e-procurement reform will allow COMPRAMEX to move towards a transactional tool in public procurement procedures. This will contribute to maximising the benefits of using e-government tools to achieve more efficiency and value for money in the use of public funds.

Using COMPRAMEX for the procurement of public works

Public works represent a significant portion of public procurement in countries. In the State of Mexico, public works accounted for 46.2% in terms of the number of procurement procedures and 17.3% in terms of value in 2018.

Regardless of this high number and volume of procurement for public works, the State of Mexico does not have an e-procurement system for public works. Indeed, the sole e-procurement system of the State of Mexico, COMPRAMEX, is an e-procurement platform exclusively for goods and services. In summary, an essential part of the public procurement market does not benefit from the efficiency and competition that an e-procurement platform could bring to the State of Mexico.

The current regulatory frameworks of procurement for public works consists of the 12th Book of the Administrative Code of the State of Mexico (Libro Décimo Segundo del Código Administrativo del Estado de México) and its Bylaw (Reglamento del Libro Décimo Segundo del Código Administrativo del Estado de México). These regulatory frameworks, however, do not refer to the use of e-procurement systems, except the e-tender notice.

According to Article 12.25 of the 12th Book of the Administrative Code of the State of Mexico and Article 38 of its Regulation, tender notices of public works have to be published at least (i) in one of the newspapers with the highest circulation in Toluca (the state capital), (ii) in one of the newspapers with the highest national circulation, and (iii) through an electronic platform that the Ministry of Control administers. However, this electronic platform has not been developed yet and tender notices of public works are published only in newspapers.

In order to comply with Article 12.25, the Ministry of Control has the idea to use its website to publish tender notices of public works in the short term. In the long term, however, the State of Mexico could consider the possibility of using COMPRAMEX not only for the procurement of goods and services, but also for that of public works.

Indeed, developing a separate e-procurement system would lead to financial and administrative burdens for both government and bidders, and contracting authorities and suppliers would need to learn how to use two separate e-procurement platforms.

There are examples of using one common e-procurement system for the procurement of goods, services and public works in Mexico. CompraNet, for example, can be used for the procurement of goods, services and public works. In 2009, the reforms to the Law on Public Sector Acquisitions, Leases and Services (Ley de Adquisiciones, Arrendamientos y Servicios del Sector Público, LAASSP) and the Law on Public Works and Related Services (Ley de Obras Públicas y Servicios Relacionados con las Mismas, LOPSRM) granted CompraNet a legal status as the official e-procurement platform for the federal government’s procurement activity. (OECD, 2018[13]) Mexico City also plans to extend the coverage of its e-procurement platform, Tianguis Digital, to the procurement of public works. The State of Mexico could benefit from considering the possibility of following these initiatives from across the country.

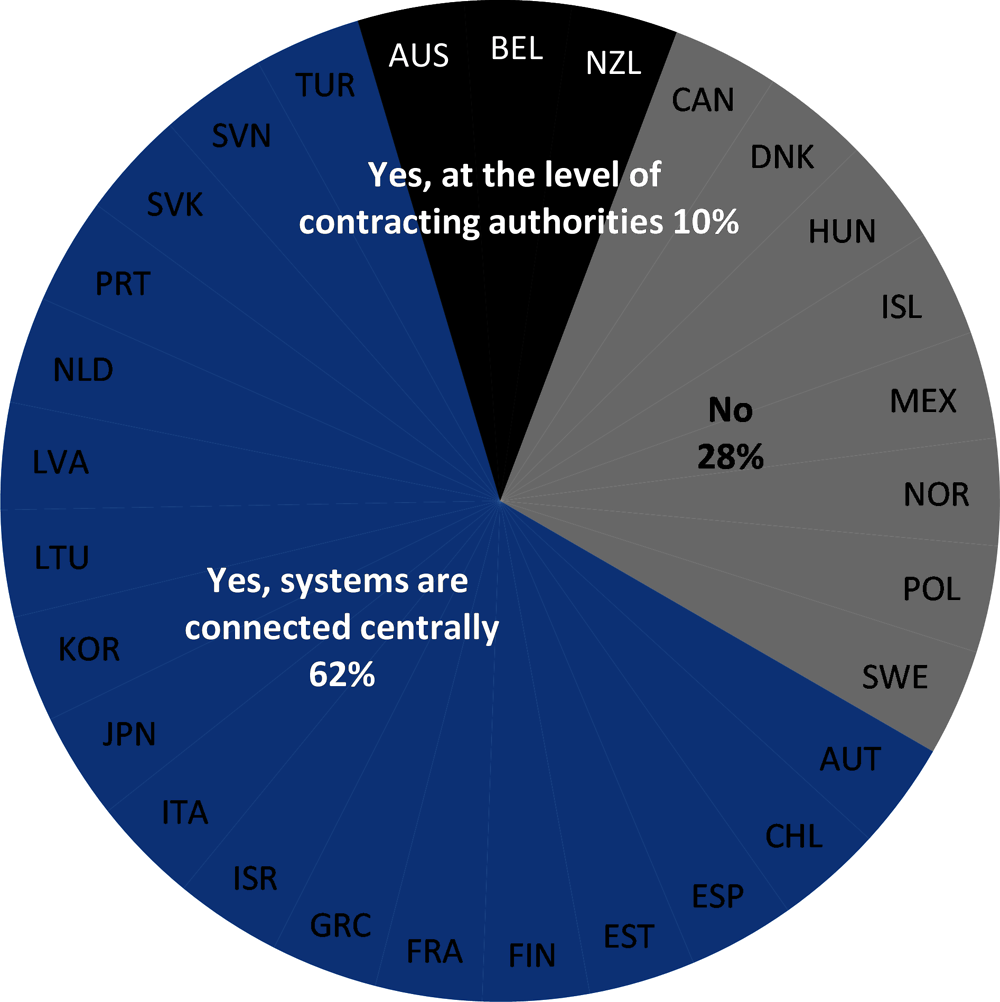

2.1.2. Integrating COMPRAMEX with other digital government systems to increase efficiency and transparency in public procurement and bolster anti-corruption initiatives

Integrating an e-procurement system with other government IT systems, such as those for public financial management (i.e., budget system, business and tax registries, and social security databases), leads to greater efficiency in the use of public funds. OECD countries are increasingly integrating their e-procurement systems with those for financial management. In fact, while only 37% of OECD countries reported some level of integration with other government IT systems in 2016, this percentage increased to 72% in 2018 (OECD, 2019[14]).

This positive change has been driven by the international trend to cover the entire public procurement cycle with fully-fledged e-procurement solutions, from planning and preparation to contract execution and payment. For example, the Korean E-Procurement System (KONEPS) provides the highest connectivity from across systems assessed in the OECD area, as it is interconnected to over 200 external databases: 65 of them are from public entities, while others include databases from 12 private sector business associations, nine credit rating companies and the payment systems of 15 commercial banks (OECD, 2016[15]).

The Law on Digital Government of the State of Mexico (Ley de Gobierno Digital del Estado de México y Municipios) calls for the interconnection of different government systems. Section XI of Article 9 of this Law stipulates that the Digital Government Council should promote interoperability of ICTs available at federal, state and municipal levels in order to ensure the co-ordination necessary for the successful implementation of digital government.

Article 19 of the LCPEMyM requires COMPRAMEX to be interconnected with the budget system. According to the Ministry of Finance, COMPRAMEX is interconnected with its budgeting system (Sistema de Planeación y Presupuesto, SPP). However, this interconnection refers to the availability of the URL to move from COMPRAMEX to SPP in order to manually check budget information. In other words, the budget information such as the budget approval status does not automatically appear in COMPRAMEX. Article 14 of the LCPEMyM stipulates that public procurement processes cannot be started without confirmation of actual budget availability followed by the corresponding budget approval. Therefore, it would be ideal if COMPRAMEX (or its internal system SICAPEM-PMCP) could be automatically linked with the budgeting system in order to reflect the approval status without any manual processes.

The Electronic System for Government Procurement (Sistema Electrónico de Contrataciones del Estado, SEACE) administered by the Government Procurement Supervising Agency of Peru (Organismo Supervisor de las Contrataciones del Estado, OSCE) provides insights which the State of Mexico could consider for the integration of its e-procurement system with other government IT systems, in order to increase efficiency and transparency of procurement system (See Box 2.4).

Peru

OSCE, Government Procurement Supervising Agency of Peru, integrated its e-procurement system of Peru, SEACE, with other government systems such as:

2. The Integrated Financial Management System (SIAF) of the Ministry of Economy and Finance (MEF) allows direct online linking for certifying the budgetary credit, enabling procuring entities to publish their procurement notices. SIAF also allows online direct linking for transferring information and contract data (suppliers’ RUC, amounts, etc.). This linking enables the entities to register commitments, accruals and payments.

3. The National Registry of Suppliers (RNP) of the OSCE allows direct online linking in order to verify if the suppliers are registered in the RNP. That registration enables suppliers to participate, present their bids and be awarded with and sign the contract.

4. The Single Register of Contributors (Registro Único de Contribuyente, RUC) of the National Superintendence of Customs and Tax Administration (SUNAT) is directly linked with SEACE in order to obtain the denomination of the natural or judicial person that will be paid as a result of the procurement.

5. The INFObras System of the Office of the General Comptrollership of the Republic allows direct online linking with procurement related to public works, which enables publication of the procurement notice.

Source: (OECD, 2017[16])

In addition, the integration of COMPRAMEX with other government systems could support the efforts of the State of Mexico to implement the digital state platform of the anti-corruption system. System integration provides more visibility and accountability on the use of public expenditures, and makes the monitoring of economic activity easier. Indeed, Germany and Colombia provide insights on system integration to support anti-corruption initiatives by making public spending more visible. (See Box 2.4)

Germany

Germany’s anti-corruption framework was updated in 2017 with a law that introduced a competition register (Wettbewerbsregister). The register enables procurers to digitally verify whether potential suppliers have committed a criminal offence. Furthermore, the register permits public authorities to access company information. Once the procurement process is digitalised, information from the competition register can be incorporated directly into the e-procurement process. Connecting information across systems ensures that companies listed in the register are prohibited from registering for and participating in tenders.

Colombia

In 2015, Colombia upgraded its e-procurement platform. During the second phase of this upgrade, Colombia integrated the Electronic System for Public Procurement (Sistema Electrónico para la Contratación Pública, SECOP II) with the Integrated System of Financial Information (Sistema Integrado de Información Financiera, SIIF). This direct connection between the e-procurement system and the financial reporting system greatly increased data accuracy and transparency on spending by contracting authorities. Integrating procurement and budget data mitigated risks of corruption, cases of false accounting and late payment of invoices.

Source : (OECD, 2019[17]) and (OECD, 2016[18])

The State of Mexico could benefit from integrating COMPRAMEX with other systems such as the budget system, business and tax registries, and complaints system (Denuncia EdoMex), and transparency portal (Sistema de Información Pública de Oficio Mexiquense, IPOMEX), in order to enhance efficiency and transparency in public procurement.

Countries have been promoting open government strategies in order to improve transparency, accountability and citizens’ trust in the public sector. Open government is defined as “a culture of governance that promotes the principles of transparency, integrity, accountability and stakeholder participation in support of democracy and inclusive growth” (OECD, 2017[19]).

Access to public information has been the cornerstone of an open and inclusive government, because it is a fundamental element to reduce corruption and increase trust among citizens and their governments. (OECD, 2016[20]) Access to information is also one of the targets (16.10) of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) adopted by all United Nations Member States in 2015. (United Nations, 2015[21]) Proactive disclosure refers to disclosing relevant information without a prior public request. This voluntary disclosure of information contributes to enhanced transparency and openness, as well as avoiding the costs associated with the administrative procedures and fees to file a request for information (OECD, 2016[20]).

When public sector information is proactively published in open and machine-readable formats and, where possible, free of cost, it becomes open government data, facilitating its reuse by anyone – anywhere – without legal or technical limitations (e.g. copyrights, proprietary formats) (OECD, 2017[22]). The reuse of open government data enables any stakeholder such as citizens, civil society, and businesses to better understand and monitor governmental activities.

Public procurement is considered as one of the most important thematic areas of the open government strategy, and one of the most popular initiatives is open contracting, or publishing information related to public procurement in open and machine-readable formats.

E-procurement systems allow governments to provide information related to public procurement in open and machine-readable formats. Thus, they contribute to increasing transparency, as well as collecting consistent, up-to-date and reliable data on procurement processes. Transparency has the potential to gain citizen trust in governments and making governments more accountable.

The OECD Recommendation of the Council on Public Procurement calls upon Adherents to “allow free access through an online portal for all stakeholders including potential domestic and foreign suppliers, civil society and the general public, to public procurement information notably related to the public procurement system.” (See Box 2.6)

II. RECOMMENDS that Adherents ensure an adequate degree of transparency of the public procurement system in all stages of the procurement cycle.

To this end, Adherents should:

i. Promote fair and equitable treatment for potential suppliers by providing an adequate and timely degree of transparency in each phase of the public procurement cycle, while taking into account the legitimate needs for protection of trade secrets and proprietary information and other privacy concerns, as well as the need to avoid information that can be used by interested suppliers to distort competition in the procurement process. Additionally, suppliers should be required to provide appropriate transparency in subcontracting relationships.

ii. Allow free access, through an online portal, for all stakeholders, including potential domestic and foreign suppliers, civil society and the general public, to public procurement information notably related to the public procurement system (e.g. institutional frameworks, laws and regulations), the specific procurements (e.g. procurement forecasts, calls for tender, award announcements), and the performance of the public procurement system (e.g. benchmarks, monitoring results). Published data should be meaningful for stakeholder uses.

iii. Ensure visibility of the flow of public funds, from the beginning of the budgeting process throughout the public procurement cycle to allow (i) stakeholders to understand government priorities and spending, and (ii) policy makers to organise procurement strategically.

Source: (OECD, 2015[1])

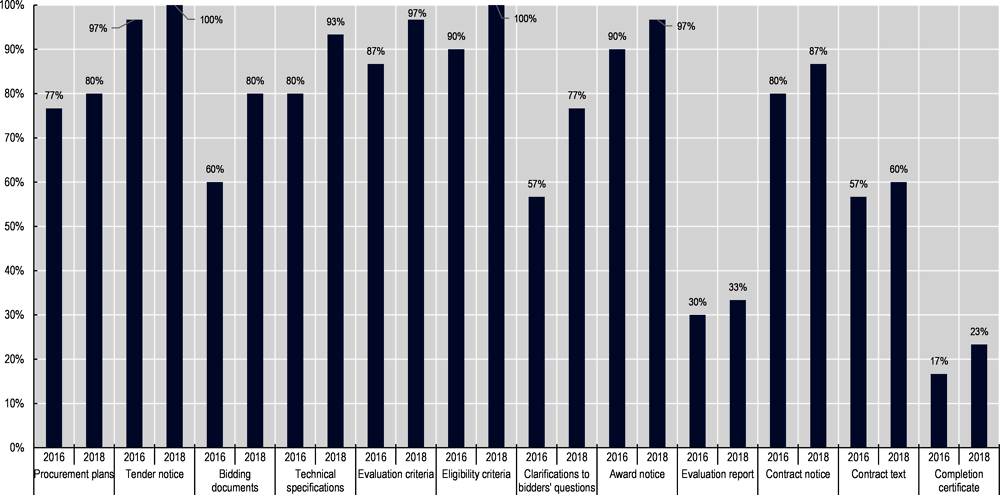

OECD countries have been publishing a wide variety of information related to public procurement. The 2018 OECD Public Procurement Survey data show that all the 30 countries surveyed published tender notices and eligibility criteria in 2018, while fewer countries published tender evaluation reports (33%), contract documents (60%), and completion certificates (23%) (OECD, 2019[8]).

Although governments produce large amounts of information related to public procurement, they face challenges relative to quality and coverage. These data are often incomplete (as they do not cover all procurement stages, such as payments), fragmented across numerous public entities (not all entities publish information), or have been left largely unused for research and policy purposes (OECD, 2017[22]).

The following section assesses the progress of access to procurement information and open government data in the State of Mexico, and how COMPRAMEX could evolve towards a transparency tool to promote open contracting data by publishing information in open and machine-readable formats.

2.2.1. The State of Mexico discloses a variety of information through COMPRAMEX and Ipomex, but needs to improve its coverage, quality and user-friendliness

The State of Mexico has been advancing the agenda of access to information in an effort to increase transparency in public procurement. Article 3, bullet VIII, of Law of Transparency and Access to Information of the State of Mexico and Municipalities (Ley de Transparencia y Acceso a la Información Pública del Estado de México y Municipios, LTAIPEMyM) provides the definition of open data (datos abiertos), and requires that data shall be processed and collected in an automatic way by the public. Article 24 also refers to the availability of information and statistics generation in open and accessible formats.

Open data is defined as digital data that is accessible online to the public, and that can be used by any interested parties, with the following characteristics:

Accessible: data is available for any stakeholder for any purpose;

Comprehensive: data describes the details of the topic with the necessary metadata;

Non-discriminatory: data is available for any stakeholder without registration;

Permanent: data is preserved so that the historical versions remain available for public use;

Primary: data comes from the original source with the maximum level of breakdown;

Machine-readable: data shall be structured, totally or partially, to be processed and interpreted by electronic tool automatically;

In open formats: data shall be available in accordance with the logical structure used to store data in a digital file, whose technical specifications are available to the public, without posing any difficulty of access and costs; and

Freedom of use: data can be used free. Citing the source of origin is the only requirement for using data

Source: (Gobierno del Estado de México, 2015[23])

However, this concept of open data has not been fully applied, in particular in machine-readable characteristics, given the current situation where only the PDF data of some documents related to tenders are available. The details of this will be discussed later in the section.

Currently, the State of Mexico has two principal open data platforms that disclose information related to public procurement: COMPRAMEX and Ipomex, the transparency portal of the State of Mexico.

COMPRAMEX

Article 156 of the Bylaws of the LCPEMyM stipulates that the information related to public procurement processes and signed contracts should be registered in COMPRAMEX, and that this information should be accessible to the public free of charge. (Gobierno del Estado de México, 2013[24])

COMPRAMEX allows any stakeholder to obtain information of individual procurement processes based on two categories: ongoing procurement processes and past procurement processes carried out between 2015 and 2018. Users can filter information of one public entity from different types of institutions (central government, auxiliary bodies, courts, autonomous organisations, and municipal governments), although it is not allowed to choose one specific entity for the central government.

The information available is similar between ongoing procurement processes and past procurement processes. COMPRAMEX uploads in PDF format documents of tender notices, tender documents, minutes of clarification meetings, minutes of tender opening, minutes of second financial proposal opening, tender evaluation reports and contracts. The information available in these PDF documents allows stakeholders to understand the details of each individual procurement procedure. In particular, the State of Mexico applies a good practice by disclosing tender evaluation reports and contract documents, because these documents are not disclosed widely in the OECD countries. Indeed, among the 30 countries that responded to the 2018 OECD Public Procurement Survey, 33% publish the tender evaluation report, while 60% disclose contract documents (OECD, 2019[8]).

Regardless of this situation, however, there are some limitations of the information available in COMPRAMEX. In general, this information is available only for the central government. For some public entities, such as auxiliary bodies and municipalities, there is no information registered in COMPRAMEX, or only limited information can be found, such as tender notice date, but available without its PDF document. Furthermore, the information is not available for the procurement of public works, because COMPRAMEX is an e-procurement system exclusive to goods and services.

In addition, users need to download and review each non-reusable PDF document of each individual procurement to collect information. For example, users need to download PDF documents to find even the most basic information, such as contract amount. Furthermore, COMPRAMEX discloses the information of each individual procurement procedure without allowing users to obtain the aggregate information, such as the total procurement volumes of specific organisations. For example, in order to collect the statistics on the total volume of procurement of a certain entity, users need to painstakingly download and read all the PDF contract documents of all the procurement procedures carried out by a specific entity. The current system works well when users need information of one individual procurement procedure of a specific public entity. However, the current characteristics of COMPRAMEX are generally not user-friendly, in particular in terms of aggregating information.

In this sense, COMPRAMEX is different from CompraNet, which provides excel sheets for each fiscal year since 2002. These excel sheets include the basic information related to public procurement, including contract amounts for all the public procurement procedures (goods, services and public works, tender methods such as open tender, and modalities such as paper-based, electronic and mixed) for one fiscal year. This allows users to easily calculate the aggregated contract amount of one fiscal year with various customised options, for example calculating the total contract amounts of open tender procedures for the procurement of public works which used electronic modalities (CompraNet, 2019[12]).

Ipomex

A Law on Access to Information is at the centre of open government reforms. More than 100 countries, including 65% of countries in the Latin America and Caribbean (LAC) region, and 97% of OECD countries passed a Law on Access to Information. In general, these laws aim to (i) ensure the greatest degree of transparency of government operations and (ii) encourage reuse of information. (OECD, 2016[20])

Ipomex is the transparency portal of the State of Mexico for disclosure of information to the public in accordance with the LTAIPEMyM. This platform is administered by the Institute for Transparency, Access to Public Information of the State of Mexico and its Municipalities (Instituto de Transparencia y Acceso a la Información Pública del Estado de México y Municipios, INFOEM)

Ipomex discloses information related to public procurement not only for goods and services, but also for public works, unlike COMPRAMEX discussed earlier.

Article 92. XXIX of the LTAIPEMyM stipulates the minimum information that each pubic entity, including municipal governments, shall disclose in Ipomex on public procurement procedures for open tenders, restricted invitations and direct awards. Each public entity is also allowed to publish additional information, on top of the minimum information. The information is available in the HTML and downloadable in an excel format.

Table 2.5 shows the requirement of disclosing specific information related to public procurement in accordance with Article 92 of the LTAIPEMyM, and its actual availability in Ipomex, for each procurement procedure (open tender/restricted invitation and direct award).

Most of the information required by Article 92 is available on Ipomex. However, some information such as “proposal submitted by the bidder” and “Authorisations to proceed with a direct award” are not available. In addition, the link to PDF documents is available for financial and physical progress reports, certificate of receipt, payment, but the linked documents are blank pages that state "N/A.” The State of Mexico should take the necessary measures to fully comply with the requirements in Article 92.

Regardless of this situation, it can be concluded that the State of Mexico discloses a wide range of information related to public procurement through Ipomex. Indeed, Ipomex discloses all the information available in COMPRAMEX, except the link to the minutes of second financial proposals (PDF).

Regardless of these good practices in disclosing information through Ipomex, two main challenges remain for the information found in Ipomex: coverage and user-friendliness. First, not all public entities of the State of Mexico comply with the disclosure obligations. For example, no information is disclosed for some municipalities: the excel sheet is blank without any information or the excel sheet itself cannot be found in Ipomex. In fact, in early 2015, 87% of municipalities reported less than 50% of their transparency obligations in Ipomex, according to the introductory text of the LTAIPEMyM. (Gobierno del Estado de México, 2015[23]).

Another issue is user-friendliness. Ipomex only allows users to download an excel file with the combination of one public entity, one type of procurement (open tender/restricted invitation or direct award), and one fiscal year (2018, 2019, etc.). The current system works well when users need information for one public entity. However, it will not work optimally when users need information for multiple public entities at once. Even the simplest operations, like aggregating contract values of a contracting authority over time, require programming skills and painstaking tasks, because many excel sheets need to be downloaded, then extensively cleaned and restructured before one can start analysing the data. For example, in order to obtain information related to public procurement for all the public procurement methods (open tender, restricted invitation and direct award) for two fiscal years 2018 and 2019 for 300 public entities, users would need to download 1 200 excel files (four excel sheets per public entity multiplied by 300 public entities) from the Ipomex website. Furthermore, if users need the aggregated amount of contracts for these 300 public entities, 1 200 separate excel sheets need to be merged into one to calculate the aggregated amount.

This situation is very different from that of CompraNet, which provides excel sheets with the basic information related to public procurement, including contract amounts for all public procurement procedures (goods, services and public works; tender methods such as open tender, and modalities such as paper-based, electronic and mixed) for one fiscal year.

2.2.2. Upgrading COMPRAMEX to store and disseminate public procurement information in a user-friendly manner

The State of Mexico has been advancing in ensuring access to public procurement information through the two platforms. COMPRAMEX provides PDF formats of some documents related to public procurement for goods and services. Ipomex provides more comprehensive coverage of information than COMPRAMEX in excel formats and it also discloses information related to the procurement of public works. However, both platforms face common challenges. Not all public entities comply with transparency obligations through COMPRAMEX and Ipomex, some do not disclose the information or publish low-quality information. In addition, both platforms lack user-friendliness in collecting information in re-usable and machine-readable formats, a fundamental pillar of open data. COMPRAMEX provides non-reusable PDF formats. Ipomex provides more comprehensive coverage of information than COMPRAMEX, but users need to download multiple excel files to analyse aggregated information because downloading options are limited with the combination of one public entity, one type of procurement methods, and one fiscal year of one individual procurement procedure, unlike the case of CompraNet.

The State of Mexico should provide reusable, higher quality and machine-readable data in a format that allows for analyses. This is a fundamental element not only for improving transparency and accountability, but also facilitating evidenced-based policy making through key performance indicators (KPIs) that measure the performance of public procurement systems, which will be discussed in Chapter 3.

For the time being, the State of Mexico could consider the possibility of publishing in COMPRAMEX all the public procurement information that is currently available in Ipomex. More flexible search options should be added in order to provide machine-readable and re-usable information. Search categories should comprise, although not be limited to, the combination of procurement information (such as contract amount, number of bidders), public entity (entity A, B, C), type of procurement procedures (open tender, restricted invitation, and/or direct award), and fiscal year (2018, 2019, 2020, etc.). For example, the aggregated contract amount for multiple public entities for open tender for 2018 and 2019 should be calculated in one search to avoid the current situation in which users download hundreds or even thousands of separate excel files to calculate this information.

The interconnection of COMPRAMEX with Ipomex should also be considered. Currently, public procurement officers need to update the information both for COMPRAMEX and Ipomex, which leads to duplicated tasks and risks of inconsistencies. Therefore, it would be ideal if the information updated in COMPRAMEX were reflected automatically in Ipomex. However, it is worth mentioning that COMPRAMEX and Ipomex are governed by regulations of different nature, and each platform is managed by different entities (Ministry of Finance for COMPRAMEX, and INFOEM for Ipomex). Therefore, the interconnection of these platforms should be considered as a potential option in the long-term, taking into account the co-ordination required.

The possibility of using COMPRAMEX for the procurement of public works is also important in this context, because currently COMPRAMEX is an e-procurement system only for the procurement of goods and services, and the procurement information related to public works is only available in Ipomex.

These efforts will also create the basis for the State of Mexico to consider the adoption of the Open Contracting Data Standard (OCDS), which Mexico has been trying to promote for some time. (See Box 2.8)

The Open Contracting Data Standard (OCDS) is an open data standard for public contracting, implemented by over 30 governments around the world. It is the only international open standard for the publication of information related to public procurement. It was created to support organisations to increase contracting transparency and enable deeper analysis of contracting data by a wide range of users.

The OCDS recommends data and documents to be published with the classification level of basic, intermediate, and advanced, and how to publish them. Thus, the OCDS facilitates the structured publication of data at all stages of the contracting process: planning, tendering, awarding, contracting and implementation.

In December 2015, Mexico announced its compromise to implement the OCDS for all government contracts, starting with the New Airport of Mexico City. Although the Mexican government has agreed to implement the OCDS, the information currently published in national and local e-procurement systems does not provide completely “sharable, reusable, machine readable data” as required by the OCDS.

However, Mexico has been active in promoting the OCDS. For example, Mexico established the Contracting 5 (C5) Initiative with Colombia, France, the United Kingdom and Ukraine, an international forum to exchange practices and knowledge on open contracting and build a shared knowledge-base towards the adoption of the OCDS by a greater number of countries.

Source: (OECD, 2017[22]) and website of OCDS

2.3.1. The State of Mexico needs a clear strategy and strong institutional leadership to advance the reform of COMPRAMEX

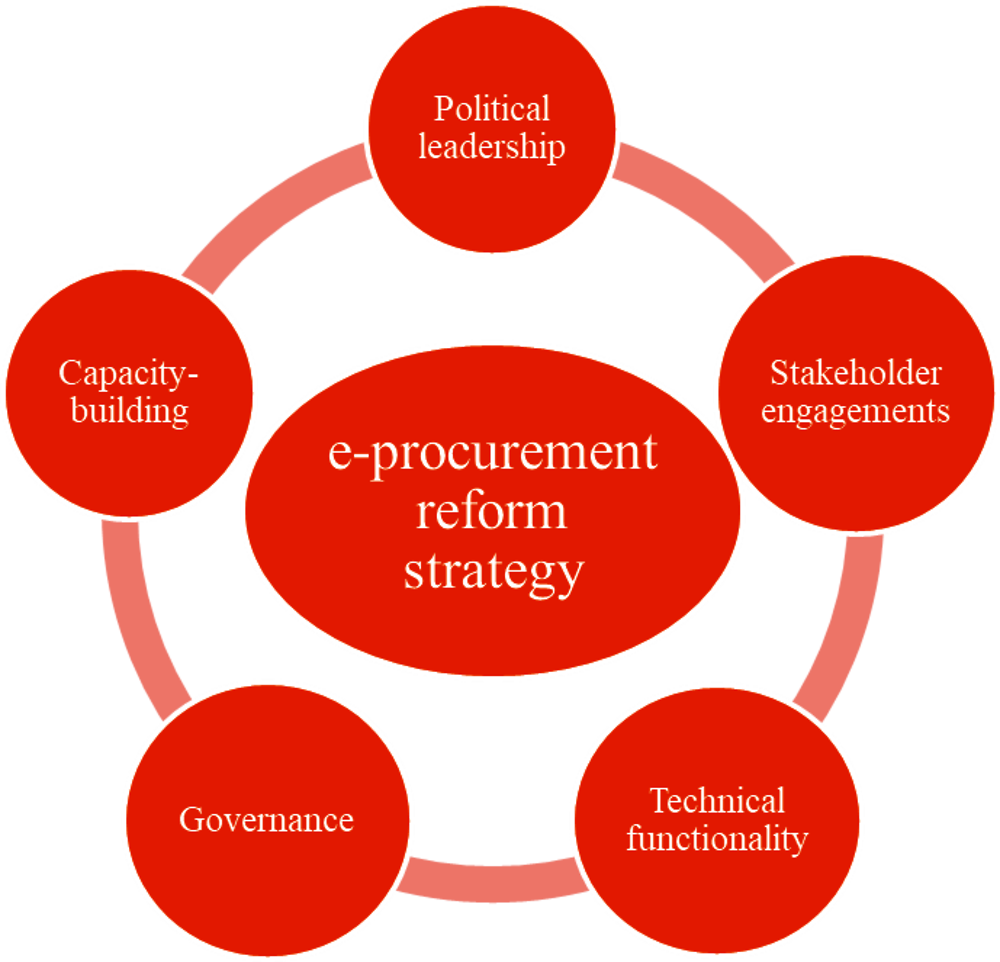

Implementing e-procurement reform requires time. Therefore, well-planned strategies and roadmaps are required for the successful implementation of e-procurement reform. This section discusses the factors that the State of Mexico should take into account in order to develop the e-procurement reform strategy for successful implementation. The development of such a strategy should focus on five key elements: institutional leadership, stakeholder engagement, technical functionality, governance and capacity building.

Institutional leadership is a decisive factor for the successful implementation of e-procurement reforms. Governments need to clearly define the vision for what is to be achieved through e-procurement reform and assign an agency responsible for advancing the agenda, backed by strong institutional leadership. For example, the Federal Government of Mexico set up a vision for the reform of CompraNet as a starting point of the process (Box 2.10).

Indeed, institutional leadership is a critical element for e-procurement reform in the State of Mexico. The reform has not achieved significant progress since 2013, when the LCPEMyM was amended to facilitate the digitalisation of public procurement procedures through COMPRAMEX. Currently, the State of Mexico has a plan by the end of 2020 to update COMPRAMEX by introducing e-submission and e-signature, which is foreseen in the LCPEMyM. The Ministry of Finance is in charge of implementation under the leadership of the DGRM and the General Directorate of the State IT System (Dirección General del Sistema Estatal de Informática, DGSEI). However, such implementation plan is still under development, which implies that the timeframe might not be achieved, considering the time necessary to implement the e-procurement reform.

In addition, lack of institutional commitment is reflected in the absence of the Digital Agenda of the State of Mexico, which has not been developed regardless of the requirement of the Law on Digital Government of the State of Mexico, issued in 2015. Article 9 of this law stipulates that the State Council on Digital Government should approve a Digital Agenda. However, five years on from the establishment of this law the Council has not taken the decisions to move forward this Agenda. Therefore, the State of Mexico should convene the State Council on Digital Government, in accordance with the Law, to discuss and develop the Digital Agenda. The Council consists of 31 institutions: the heads of the Ministry of State, the Ministry of Economic Development and the Ministry of Finance, as well as the heads of the remaining thirteen ministries, four mayors, the head of the Human Rights Commission, and the State’s Attorney General, among other stakeholders.

The membership of the Council creates an opportunity to gain strong political buy-in from the whole-of-government. It is critical to develop the Digital Agenda of the State of Mexico, including the reform of COMPRAMEX. In Turkey, for example, the decision of the Prime Minister to include e-procurement reform into eleven high priority e-government agendas and projects not only demonstrated strong political commitment by the Turkish government, but also made it easier to allocate financial and technical resources. (The European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, 2015[25]) Strong institutional support would bolster the reform of COMPRAMEX as an advanced e-procurement system with improved transactional functionalities, interconnection with other government databases and open data platforms.

In order to demonstrate such a strong commitment, the State of Mexico would also benefit from establishing a website dedicated to e-procurement reform, which should clearly outline the reform vision, strategy, programme and timeframe to ensure that the efforts of the government are visible to the public.

2.3.2. The State of Mexico could establish a Plural Working Group to define the vision statement of COMPRAMEX reform

The Ministry of Finance is in charge of implementing e-procurement reform, under the leadership of the DGRM and the DGSEI. In addition to institutional commitment, it is critical to consider stakeholder engagement during the reform process. The OECD Recommendation on Public Procurement calls upon countries to invite stakeholders, including the private sector and civil society, to participate in public procurement reform, as it is a project with a multitude of stakeholders, each of whom has different views and conflicting interests. This participation process ensures that the reform gains strong social support through shared understanding between the government and stakeholders (See Box 2.9).

VI. RECOMMENDS that Adherents foster transparent and effective stakeholder participation.

To this end, Adherents should:

i. Develop and follow a standard process when formulating changes to the public procurement system. Such standard process should promote public consultations, invite the comments of the private sector and civil society, ensure the publication of the results of the consultation phase and explain the options chosen, all in a transparent manner.

ii. Engage in transparent and regular dialogues with suppliers and business associations to present public procurement objectives and to assure a correct understanding of markets. Effective communication should be conducted to provide potential vendors with a better understanding of the country’s needs, and government buyers with information to develop more realistic and effective tender specifications by better understanding market capabilities. Such interactions should be subject to due fairness, transparency and integrity safeguards, which vary depending on whether an active procurement process is ongoing. Such interactions should also be adapted to ensure that foreign companies participating in tenders receive transparent and effective information.

iii. Provide opportunities for direct involvement of relevant external stakeholders in the procurement system with a view to increase transparency and integrity while assuring an adequate level of scrutiny, provided that confidentiality, equal treatment and other legal obligations in the procurement process are maintained.

Source: (OECD, 2015[1])

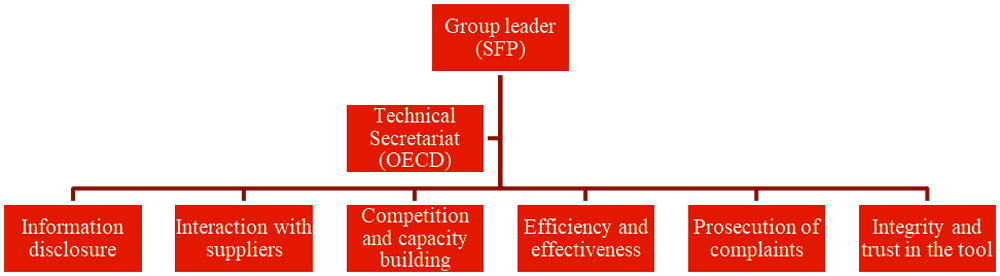

During the phase of designing a reform strategy for COMPRAMEX, the State Government could consider the experience of the Federal Government of Mexico relative to CompraNet’s reform. In 2018, the Ministry of Public Administration (Secretaría de la Función Pública, SFP) of the Federal Government convened a multi-stakeholder group for the reform of the e-Procurement system. This multi-stakeholder group included representatives from the public sector, business, and civil society, and worked towards the development of a shared vision statement regarding e-procurement in Mexico. The vision statement also aimed to serve as a guide for the future development of e-procurement tools in Mexico, including at the subnational level. This collaborative practice was in line with the principle of participation included in the Recommendation of the OECD Council on Public Procurement.

The Plural Working Group consisted of six subgroups: information disclosure, interaction with suppliers, competition and capacity building, efficiency and effectiveness, management of complaints and integrity and trust in the tool. Each subgroup was represented by a wide range of stakeholders, including the public sector, civil society, and businesses, and worked on specific key issues and themes, as Table 2.6 illustrates.

As already discussed, the establishment of the Plural Working Group was an indispensable element to set up a shared vision statement for Mexico’s e-procurement system (See Box 2.10).

In 2018, the multi-stakeholder working group convened by the Federal Government of Mexico to reform CompraNet developed a collaborative vision statement to establish new foundations for e-procurement systems in Mexico. In this vision, the Plural Working Group on Public Procurement recognised the opportunities provided by digital technology to enable a fully transactional system that supports the whole public procurement cycle, from planning through tendering and award (contracting), to payment and contract management, as well as subsequent monitoring and auditing. The vision statement considers the following twelve principles that capture the goals and ambitions of all stakeholders involved in the public procurement process:

1. Transactional: The entire public procurement cycle will be managed electronically and establish complete flows connecting each of the steps automatically.

2. Standardised: The entire public procurement cycle will conform to specifications and approved pre-established formats and adopt internationally accepted contracting data standards.

3. Transparent: The e-procurement system will be the only access point for information of the government procurement cycle for any type of procurement procedures.

4. Trustworthy: The information uploaded to the system will be accurate, complete, updated and secured under strict protocols.

5. Interconnected: The system will offer interconnection between the processes of the procurement cycle as well as between government information systems (e-government), including those of budget and revenue agencies.

6. Co-ordinated: The various entities and user units of the system will use it as a tool to ease co-ordination and facilitate consolidated purchases looking for the best market conditions and the standardisation of the procurement process. The system will include modules that allow for public procurement strategies such as reverse auctions and framework agreements.

7. User-friendly: The system is designed to offer users clarity on the available information and where to find it, as well as quick access to the system and high-speed navigation, A help desk provides useful advice to users, with sufficient numbers of qualified staff to address users’ needs.

8. Instrumental for users: The platform provides information for both public servants and the social and private sectors. It will help them in the following tasks: analysing public procurement and the performance of those involved in such activity; making decisions to participate in procurement processes; defining public procurement policies and improvement initiatives for public procurement; supporting audit and control tasks, and carrying out investigations and analyses of procurement outcomes, including the production of statistics and indicators. The platform will also facilitate the preparation of market research and Annual Plans of acquisitions, leases and services, as well as public works, so they can be published in a timely manner with updated information and provide useful input for the industry. The system’s Registry of suppliers, including suppliers profiles, shareholders, history of performance in public procurement and illicit actions, will contribute to informed decision making by procurement officials.

9. Accountable: The system links to citizen complaint mechanisms set up for the complete procurement cycle and includes an updated registry of suppliers that have been sanctioned.

10. Dynamic and innovative: A focus on process innovation will help the system introduce new information-management methodologies in procurement for public works, goods and services, based on knowledge from previous experiences, opinion and feedback from users, and guided by international best practices.

11. Geared towards economic competition: The system encourages competition, free concurrence and reduces entry barriers, transaction and administrative costs for all types of users.

12. Exemplary: The e-procurement system of the Federal Government will be a good practice for all other public e-procurement systems in Mexico to follow, such as those to be developed by states, municipalities and public entities subject to different procurement regimes.

Source: (OECD, 2018[13])

The State of Mexico could consider setting up a multi-stakeholder group in order to establish a dialogue with a wide range of actors for communication and feedback on upcoming reforms of its e-procurement system.

2.3.3. The plural working group could define technical functionalities for the future of COMPRAMEX

Governments need to define the technical functionalities of the e-procurement system to implement its reform. These technical functionalities could consist of, but are not limited to, the following:

Transactional functions of procurement processes: Which procurement processes (for example, e-submission) should be carried out by the e-procurement system and for which procurement categories (goods, services and/or public works)? In addition, it is important to define whether it is mandatory for each of those processes to be carried out electronically

Interconnectivity: Which digital government systems (for example, the budgeting system) should be inter-connected with the e-procurement system?

Access to information: What kind of information (for example, the number of bidders for each procurement process) is disclosed in the e-procurement platform and how the information will be collected?

The current situation and recommendations for COMPRAMEX have been already discussed in sections 1 and 2 of this chapter. The technical functionalities should be defined with a clear timeframe for implementation and aligned with the vision statement to be developed.

In addition, new functionalities should be introduced in a phased approach, supported by a piloting period with the participation of selected stakeholders. The piloting period would help reform leaders better understand the user environment for potential improvement, as well as training needs.

2.3.4. The plural working group could help reviewing the current regulatory framework of public procurement, in accordance with the vision statement

E-procurement reform entails amendments to the regulatory framework. The LCPEMyM states that full digitalisation will be completed gradually. Potential amendments to the current LCPEMyM could involve the following aspects, to be identified by the Plural Working Group, to feed into the normative review recommended in Chapter 1.

New e-purchasing options such as framework agreements, which are discussed in Chapter 3.

New transactional functions of procurement processes (it should be clear in which cases it is mandatory to use those functions).

Interconnectivity of COMPRAMEX with other digital government systems, such as the budget system (SPP), business and tax registries, complaints system (Denuncia EdoMex) and the transparency portal (IPOMEX).

E-platform for the procurement of public works (for example, to use COMPRAMEX for the procurement of public works).

Information disclosure (for example, to publish the same level of information that is currently available in IPOMEX and to list all the information to be disclosed).

2.3.5. The State of Mexico should overcome potential barriers to COMPRAMEX reform through capacity-building and awareness-raising activities

Successful implementation of e-procurement reform requires a change management process. Governments should ensure that public procurement officers, as well as any other stakeholders, including suppliers, are not only aware of the strategic importance of e-procurement but also have the right skills and knowledge of the processes and functionalities of the new e-procurement system. Therefore, it is highly important to provide capacity-building opportunities.

Indeed, the 2016 OECD Survey on Public Procurement demonstrates that the main challenges faced by contracting authorities in OECD countries when using e-procurement systems are an organisational culture that is not as innovative as it could be (57%), limited ICT knowledge and skills (40%) and limited familiarity with the economic opportunities that e-procurement systems can offer (37%). According to a survey carried out by the OECD, the State of Mexico identified the lack of an open organisational culture focused on innovation, as the main obstacle to the development of an updated e-procurement system. These challenges need to be addressed by building capacities and raising awareness of the e-procurement system as a useful economic tool.

Currently, the State of Mexico does not provide training on COMPRAMEX. In addition, the guidelines on how to use COMPRAMEX are not available in the website. It would be indispensable to provide training on the new functions of COMPRAMEX not only to public procurement officials, but also to suppliers. The State of Mexico could consider developing training programmes on COMPRAMEX as part of its change management process, as was done in the case of the CompraNet reform (See Box 2.11).

In addition to the provision of training opportunities, the State of Mexico could set up a help-desk to answer questions on the use of COMPRAMEX. Currently, contracting authorities and suppliers can contact the Ministry of Finance for any questions related to the use of COMPRAMEX. However, having a dedicated help desk would facilitate the smooth transition into an updated version of COMPRAMEX. For example, in Colombia, the help desk administered by Colombia Compra Eficiente is staffed by a team of 30 officials, made up of two supervisors (one quality assurance role and one trainer) and 26 agents, each of whom processes an average of 944 cases per month. The service is available to users in three different channels: call, online chat and e-mail (OECD, 2018[13]).

Preparing users for changes to the e-procurement system should involve efforts to provide training targeted at suppliers and contracting authorities.

For procurement practitioners, SFP developed a face-to-face training programme, as well as online courses for self-training on the use of CompraNet. Around 10 800 procurement officials were trained through face-to-face sessions between 2011 and 2018.

Since 2012, more than 18 300 suppliers received face-to-face training at an average of 2 600 per year. However, it was necessary to expand the scope of training efforts, considering the number of suppliers registered in CompraNet (over 260 000 as of August 2018). Under these circumstances, SFP developed a series of training videos regarding different procurement processes and CompraNet, in order to deal with the limited resources to increase face-to-face sessions for suppliers. In total, eight videos were produced with a total count of over 340 000 views since 2015 and over 1 800 subscribers to CompraNet’s YouTube channel.

An additional Technical Guide for Suppliers on the use of CompraNet (Guía técnica para licitantes sobre el uso y manejo de CompraNet) was also developed in a PDF format available for free download from CompraNet.

Source: (OECD, 2019[26])

The State of Mexico reformed the LCPEMyM in 2013 in order to facilitate the digitalisation of public procurement procedures through the gradual introduction of COMPRAMEX. This was an important step to increase efficiency and transparency in public procurement. However, efforts have not led to transactionality in the use of COMPRAMEX: It has never been used to carry out procurement processes in the electronic modality since the reform in 2013. There is much room for improvement in transactional functions that do not comply with the requirement of the legal framework, its interconnection with other government systems and the disclosure of public procurement information in a user-friendly way.

This situation could be attributed to the weakness of several elements such as institutional will, awareness of the strategic importance of public procurement and a clear vision and roadmap for the reform strategy. This is illustrated in the absence of the Digital Agenda, a plural working group (or some other form of stakeholder engagement) and a clear implementation plan for the COMPRAMEX reform, which is scheduled to be completed by the end of 2020.

Therefore, the State of Mexico needs to develop strategies and a roadmap for the successful implementation of e-procurement reform. The development of the reform strategy should focus on five key elements: institutional leadership, stakeholder engagement, technical functionality, governance and capacity building.

The State of Mexico will benefit from considering the following recommendations and roadmap to reform COMPRAMEX to increase efficiency and transparency of public procurement, as Table 2.8 illustrates. The timeframe consists of three phases: short (within six months), medium (within one year), and long (over one year). The actions that fall into “short” and “medium” will be subject to the follow-up survey that is planned in one year after the launch of this review.

If successfully implemented, COMPRAMEX could be transformed into a more comprehensive, transactional, interconnected and transparent e-procurement system with reusable and comprehensible data.

References

CompraNet (2019), Contratos, https://sites.google.com/site/cnetuc/contrataciones (accessed on 18 February 2020).

European Commission (2016), EU Public Procurement reform: Less bureaucracy, higher efficiency, https://www.google.com/search?q=EU+public+procurement+reformless+bureaucracy+,+higher+efficiency&sourceid=ie7&rls=com.microsoft:en-GB:IE-Address&ie=&oe=&gws_rd=ssl#spf=1580380510830 (accessed on 30 January 2020).

European Commission (n.d.), Digital procurement, https://ec.europa.eu/growth/single-market/public-procurement/digital_en (accessed on 7 February 2020).

Gobierno del Estado de México (2015), Ley de Transparencia y Acceso a la Información Pública del Estado de México y Municipios.

Gobierno del Estado de México (2013), Reglamento de la Ley de Contratación Pública del Estado de México y Municipios, http://legislacion.edomex.gob.mx/node/108 (accessed on 6 January 2020).

OECD (2019), Follow-up Report on CompraNet Reform, https://www.oecd.org/gov/public-procurement/follow-up-report-on-compranet-reform.htm (accessed on 21 February 2020).

OECD (2019), Government at a Glance 2019, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/8ccf5c38-en.

OECD (2019), Public Procurement in Germany: Strategic Dimensions for Well-being and Growth, OECD Public Governance Reviews, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/1db30826-en.

OECD (2019), Reforming Public Procurement: Progress in Implementing the 2015 OECD Recommendation, OECD Public Governance Reviews, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/1de41738-en.

OECD (2018), Mexico’s e-Procurement System: Redesigning CompraNet through Stakeholder Engagement, OECD Public Governance Reviews, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264287426-en.

OECD (2017), Compendium of good practices on the use of open data for Anti-corruption: Towards data-driven public sector integrity and civic auditing.

OECD (2017), Government at a Glance 2017, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/gov_glance-2017-en.

OECD (2017), Public Procurement in Peru: Reinforcing Capacity and Co-ordination, OECD Public Governance Reviews, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264278905-en.

OECD (2017), Recommendation of the Council on Open Government, https://legalinstruments.oecd.org/en/instruments/OECD-LEGAL-0438 (accessed on 18 February 2020).

OECD (2016), Government at a Glance: Latin America and the Caribbean 2017, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264265554-en.

OECD (2016), Open Government: The Global Context and the Way Forward, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264268104-en.

OECD (2016), Preventing Corruption in Public Procurement.

OECD (2016), The Korean Public Procurement Service: Innovating for Effectiveness, OECD Public Governance Reviews, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264249431-en.

OECD (2016), Towards Efficient Public Procurement in Colombia: Making the Difference, OECD Public Governance Reviews, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264252103-en.

OECD (2015), Government at a Glance 2015, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/gov_glance-2015-en.

OECD (2015), OECD Recommendation of the Council on Public Procurement, http://www.oecd.org/gov/public-procurement/recommendation/OECD-Recommendation-on-Public-Procurement.pdf (accessed on 28 May 2018).

OECD (2013), Government at a Glance 2013, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/gov_glance-2013-en.

Shakya, R. (2017), Digital governance and e-government principles applied to public procurement, IGI Global, https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-5225-2203-4.

The Asian Development Bank, T. (2004), Electronic Government Procurement Roadmap.

The European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (2015), Are you ready for eProcurement?, https://www.ppi-ebrd-uncitral.com/index.php/en/component/content/article/427-ebrd-is-launching-a-guide-to-eprocurement-reform-are-you-ready-for-eprocurement (accessed on 12 March 2020).

United Nations (2015), Sustainable Development Goals, https://www.mendeley.com/library/ (accessed on 30 October 2019).