Executive summary

Belgium has been a member of the Development Assistance Committee (DAC) since 1960; its last peer review was in 2015. This peer review report assesses the progress made since then, highlights recent successes and challenges, and provides recommendations for the future. Belgium has partially implemented 53% of recommendations made in 2015, and fully implemented 35%. This review, which contains the DAC’s main findings and recommendations and the Secretariat’s analytical report, was prepared with reviewers from Luxembourg and Switzerland for the DAC Peer Review meeting for Belgium at the OECD on 14 October 2020.

Global efforts. Belgium stands out for its international commitment to countries and territories in fragile situations, and to gender equality – especially sexual and reproductive health and rights. A strong advocate of multilateralism in tackling global issues, it is actively involved in the reform of the United Nations. Although Belgium is committed to policy coherence for development, it does little to mobilise the co-ordinating and monitoring bodies that could assess the impact of its domestic policies on developing countries. Belgium mainly strives for coherence through its “comprehensive approach”, which targets coherence in its foreign policy. That said, new multi-actor partnerships have made it easier to factor development issues into key sectors of the Belgian economy, such as the chocolate industry, medicines and the diamond trade. Belgium’s commitment to global citizenship is exemplary. However, its communication strategy does little to explain the risks associated with engagement in fragile states.

Policy vision and framework. Belgium has modernised its policy framework by reasserting its partnership with the private sector and promoting “digital for development” in its focus on fragile contexts. This reorientation has led to a multiplication of themes, but without clarifying priorities; how the various themes relate to each other in addressing the causes and consequences of fragility; or how gender, environment and migration issues are integrated into the overall co-operation portfolio. The Law on International Co-operation reflects the general philosophy of the 2030 Agenda. The rights-based approach is used as an analytical framework to identify populations left behind whose rights and freedoms are being violated, but does not specify the consequences of the approach for programming. Finally, the policy framework highlights the role of partnerships in achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and the importance of respecting each actor’s mandate and right of initiative.

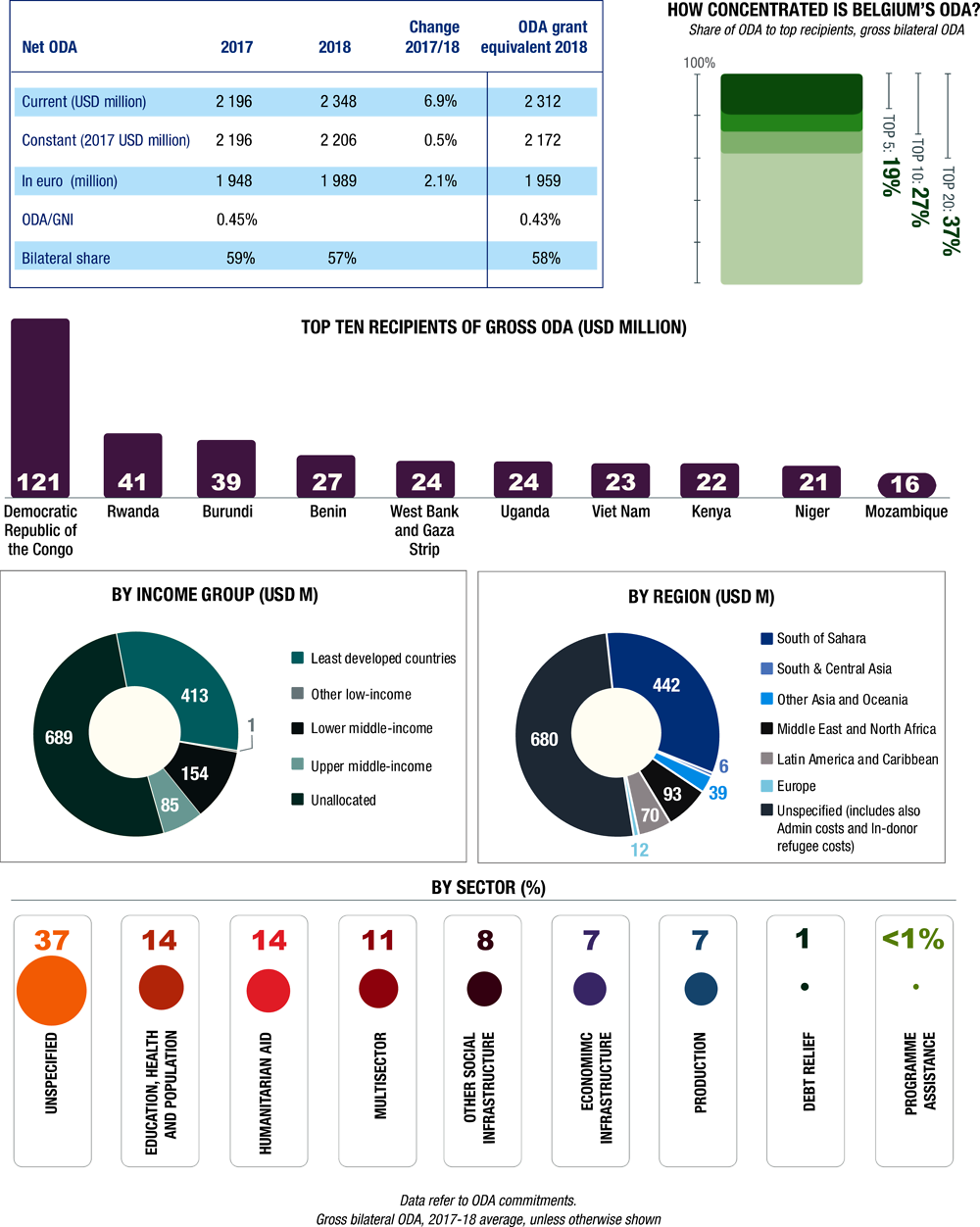

Development finance. Belgium is the 10th most generous DAC member for its official development assistance (ODA) as a proportion of gross national income (GNI). After years of sharp budget cuts, the ODA budget has been relatively stable at around 0.42% of GNI from 2015 to 2019, but no growth is forecast. Bilateral allocations, mostly in the form of grants, are broadly in line with the priorities set out in the Development Co-operation Act. They focus on least developed countries (LDCs) and fragile contexts, and a commitment to gender equality, although there is some thematic dispersion. The importance that Belgium gives to multilateralism is reflected in its allocations to the core budgets of 15 organisations. Belgium has launched several initiatives to mobilise additional resources for development finance. These initiatives, with varying levels of success, include waiving fiscal exemption on ODA expenditure, issuing humanitarian impact bonds and creating an investment fund that is open to private investment. As the Belgian Investment Company for Developing Countries (BIO) is strengthening its performance measurement mechanisms, doing more to clarify the expected results of each investment and their contribution to the SDGs to complement the overall intervention logic would enhance its effectiveness.

Structure and systems. Belgium’s development co-operation has implemented reforms to streamline its efforts, promote synergies and increase its flexibility and impact, particularly by strengthening partner autonomy. The Directorate-General for Development Co-operation and Humanitarian Aid (DGD) must now assume its role as a driving force for policy proposals and co-ordination. DGD staff are affected by the pace and nature of the reforms and are seeking greater support and more active communication. An inventory of needs and available skills, both within the DGD and among its partners, would enable the DGD to draw up an action plan to reconcile needs and resources and to become fully involved in workforce planning and forecasting. Strengthening the whole-of-government approach and increasing the level of decentralisation within the administration and on the division of responsibilities between the political and administrative levels would increase the effectiveness of Belgian aid.

Delivery and partnerships. Belgium uses predictable and flexible instruments to fund its partners. Establishing common strategic frameworks for non-government co-operation actors has proved useful in streamlining and consolidating some of the bilateral effort, and could serve as inspiration in drafting country strategies that cover all funding channels. Belgium has improved the transparency and accountability of its development co-operation to the Belgian public and in partner countries and territories. It is involved in co-ordinating technical and financial partners and is recognised by its peers for its political courage in its exchanges with governments on human rights issues. Despite being involved in consultation exercises, alignment with the development priorities of its partner countries and territories, country ownership and its use of country systems are declining.

Results, evaluation and learning. Belgium is reforming its results-based management approach to highlight how its co-operation contributes to the SDGs. It will need to ensure that the new monitoring modalities also inform strategic decision making, including in partner countries and territories, and do not constrain adaptive management in fragile contexts. Belgium has established an evaluation system based on the capacities of implementing partners, allowing the Special Evaluation Office to focus on transversal and strategic evaluations and on monitoring the implementation of recommendations. As the DGD and Enabel develop new instruments for knowledge management, greater clarity on the learning strategy and the role of each actor would allow for better co-ordination of efforts.

Fragility, crisis and humanitarian aid. Belgium’s approach to fragility and emergencies is based on extensive experience in fragile contexts, a revised institutional framework to improve its flexibility and responsiveness, stronger whole-of-government co-ordination and updated risk management. Nevertheless, resources allocated to peacebuilding, conflict prevention and the United Nations peace and security reform do not match Belgium's level of ambition. Similarly, efforts to raise awareness of in the specific challenges to design and carry out programmes in fragile contexts have not yet reached all Belgian co-operation staff. Belgium is a highly valued humanitarian actor, both for its strategic advocacy and for its efforts to ensure flexible and predictable funding that matches its priorities. The growing gap between the humanitarian budget and staffing levels poses a serious reputational risk, however.

1. The Federal Public Service (FPS) Foreign Affairs should expand the mechanisms set up under the comprehensive approach, strengthen co-ordination between task forces and involve key partners more systematically. It should build on this approach to anchor the whole-of-government approach in its development agenda.

2. DGD should continue to adapt its approaches to ensure that programming is driven by resilience and development needs, rather than implementation modalities, by:

ensuring that budget lines, funding channels and management systems provide the necessary flexibility for adaptive management and partnerships

continuing to raise awareness among its staff and that of its partners, including those in support roles, of the implications of operational issues specific to fragile contexts.

3. Belgium should clarify the delegation of authority in defining co-operation policy, developing country portfolios and managing strategic and technical knowledge in order to streamline decision making and optimise learning.

4. Belgium should develop comprehensive country and regional strategies that include all delivery channels active in priority regions, countries and territories, and focus the dialogue with implementing partners on priorities identified in the process.

5. Drawing on its experience of robust dialogue, Belgium should ensure that the governments of partner countries and territories are involved sufficiently early enough in defining country portfolios in order to strengthen ownership and mutual accountability and ensure sustainable results.

6. BIO should strengthen its efforts to measure and communicate ex-ante and ex-post results for each investment, and to seek synergies with Enabel’s portfolio.

7. The DGD should, in consultation with its partners, develop an overall strategic framework which clarifies:

the order of priorities and how these priorities and cross-cutting themes are addressed in fragile contexts

the operational consequences of a rights-based approach for reducing poverty and leaving no-one behind.

This reflection could serve as a roadmap for developing future thematic and regional strategies and country portfolios.

8. In pursuing its comprehensive approach, Belgium should mobilise the task forces created under this approach as well as other existing or upcoming mechanisms to identify domestic policies that have a negative impact on developing countries and relay the challenges to the relevant federal public services, ministries and their cabinets.

9. Belgium should establish a roadmap to maintain the stability in ODA volumes in the short term before returning to a medium-term growth path.

10. As part of a strategic workforce planning, the DGD should map the skills available across the system, assess whether they match its strategic priorities, support the continued roll-out of recent reforms and build capacities to deliver on those reforms. This could include job rotations across departments and with the other direct bilateral co-operation actors.