copy the linklink copied!8. Increasing the scale-up potential for disadvantaged entrepreneurs

This chapter examines the role that public policy can have in increasing the number of new start-ups with scale-up potential that were launched by women, immigrants, youth, and senior entrepreneurs, as well as those starting businesses out of unemployment. It discusses scale-up, the role that it has in promoting economic growth, innovation and job creation. The chapter discusses the barriers to scale-up faced by entrepreneurs from groups that are under-represented or disadvantaged in entrepreneurship and the ways that policy can address these obstacles. Policy advice is provided for national, regional and local governments and is illustrated with good practice examples from European Union (EU) Member States and non-EU OECD countries.

copy the linklink copied!Key messages

Scale-ups are important for job generation and innovation but some parts of the population are under-represented in growth-oriented businesses. For example, monitoring data from growth-oriented support programmes for women entrepreneurs in Ireland show that most participants hire several new employees and reach new markets shortly after completing the programme. Evidence from the United States shows that older entrepreneurs are much more likely than young entrepreneurs to operate high-growth firms – a 50 year old business starter is 1.8 times more likely to achieve high-growth than a 30 year old.

In the context of inclusive entrepreneurship, scale-up should be viewed differently. While many entrepreneurs from under-represented and disadvantaged groups do create high-growth firms, they are, on average, less likely to do so. Therefore policies that seek to support growth for inclusive entrepreneurship should seek to create higher quality start-ups and to increase the share of those that have the potential to create jobs and have economic and social impacts.

Scale-up policies address a wide range of policy areas, including the regulatory and institutional environment, skills, innovation, digital economy, access to finance and more. Therefore, policy makers need to consider a holistic approach to developing policies and programmes to enable scale-ups to realise their potential.

Policy makers need to better understand these challenges faced by entrepreneurs from under-represented and disadvantaged groups, including how overall framework conditions impact these groups differently. Other key challenges faced by these entrepreneurs in establishing businesses with growth potential include a lack of growth ambitions, greater risk aversion, a lack of skills to manage a growing business, difficulties access suitable financing and ineffective networks.

Entrepreneurs from disadvantaged groups face similar barriers to scale-up as other entrepreneurs, but often to a greater extent. A key barrier that policy needs to seek to address is a lack of motivation for scaling-up. This is especially significant among women: only 5.5% of new female led start-ups expect to create at least 19 jobs over the next five years relative to 12.3% of those led by men. In addition, women, immigrants, youth and senior entrepreneurs are less likely to have management skills, face greater obstacles to obtaining external finance for growth and have small and less effective networks, and are more likely to be risk averse. Another barrier to scale-up is regulatory disincentives concerning access to welfare benefits (e.g. unemployment insurance benefits) and tax measures (e.g. income splitting in households), which can also have a negative impact on business growth for inclusive entrepreneurship policy target groups.

A range of policy action have been implemented in European Union Member States to increase the growth potential of businesses operated by entrepreneurs from under-represented and disadvantaged groups. The vast majority are targeted at women and youth entrepreneurs and key areas of action include management training and strengthening networks. These types of initiatives can be adopted more widely and used to bridge specific groups of entrepreneurs into mainstream supports. It is also important for policy makers to do more to link tailored initiatives and mainstream business development support services.

Policy recommendations

Foster an environment that is conducive to scale-ups by diverse entrepreneurs.

-

Use regulatory impact assessments to identify and minimise the negative impacts of regulatory changes that impact business growth for different profiles of entrepreneurs, including motivations to grow. Priority should be given to gender assessments.

-

Increase the share of entrepreneurs from under-represented and disadvantaged groups that have motivations for scale-up by promoting role models with different backgrounds and through entrepreneurship education (in the formal education system).

-

Support dedicated business angel networks to improve access to external finance, notably for women entrepreneurs. This could include some financing to build up networks (e.g. operating costs) and promotion.

Adapt scale-up support programmes to better support entrepreneurs from under-represented and disadvantaged groups.

-

Offer management training and mentoring to help entrepreneurs from under-represented and disadvantaged groups with growth motivations acquire entrepreneurship and management skills to manage a rapidly growing business.

-

Offer tailored training programmes and bootcamps on digital skills, internationalisation and investor readiness for entrepreneurs from under-represented and disadvantaged groups.

-

Design tailored and targeted initiatives as a method to bridge entrepreneurs from under-represented and disadvantaged groups into mainstream support programmes.

-

Deliver support to growth-oriented entrepreneurs from disadvantaged groups in a progressive manner that requires a demonstration of success before more intensive support is offered.

Strengthen the evidence base on the effectiveness of policies and programmes.

-

Develop disaggregated data on business performance and programme evaluation to better understand the impacts of different profiles of entrepreneurs.

-

Undertake systematic and rigorous evaluations of programmes that support growth-oriented entrepreneurs. This is particularly true for finance programmes as there is a need to better understand the effectiveness of allocating risk capital investments to entrepreneurs from under-represented and disadvantaged groups.

copy the linklink copied!Scaling-up in the context of under-represented and disadvantaged groups

What is a scale-up?

Scale-up broadly refers to the transformation of start-ups into larger enterprises. However, the term is used inconsistently in policy literature, which can create some confusion. Some literature uses the term in a general sense to imply business growth, without necessarily defining it precisely (see, for example (OECD, 2019[1])). Other policy documents, including the European Union’s Start-up Scale-up Initiative, use the terms “scale-up” and “high-growth” interchangeably (see Box 8.1 for recent definitions of high-growth) while the technology and innovation literature often makes an association between scale-up and ICT. Other research measures the relative performance of firms by looking at the top proportion of performers rather than using a fixed benchmark (Lopez‐Garcia and Puente, 2012[2]).

The concept of a “high-growth firm” is widely known and has been defined by Eurostat and the OECD as enterprises with at least ten employees and an average annual growth in employment or revenue exceeding 20% over three consecutive years (Eurostat and OECD, 2007[3]). The European Commission subsequently introduced a new definition that sets a lower threshold – enterprises with 10% annualised growth in employment over three consecutive years, starting from at least 10 employees at the beginning of their growth (European Commission, 2014[4]).

However, there are other metrics that are also used, to measure growth including level of capitalisation, changes in market share and more. For example, academic research in Canada has proposed a new framework for analysing scale-up in Canada using a funnel approach to examine different stages of growth based on a firm’s level of capital: Start-up (under EUR 680 0001); Emerging (EUR 680 000 to EUR 6.8 million); Growth (EUR 6.8 million to EUR 68 million); Scaling (EUR 68 million to EUR 680 million); World Class (over EUR 680 million) (University of Toronto Impact Centre, 2018[5]). These types of approaches can be useful because different stages of growth present different challenges for the business, but it can be a challenge to obtain accurate data for small firms.

Regardless of how scale-up is measured, it must be recognised that business development is a process with varying phases of steady growth, stagnation, high growth and declines. This means that rapid growth does not have to be sustainable over a long period, even though it is often the focus of the discussion on scaling-up. The growth path can also take different forms, including organic (i.e. internally generated) and non-organic growth (i.e. through mergers and acquisitions, joint ventures or alliances). The latter is an often overlooked channel for growth, but SMEs accounted for 20% of mergers and acquisitions in the EU and US between 1996 and 2007 (OECD, 2019[1]).

While such approaches to measuring scale-up are useful for understanding macro-economic policy, labour markets and industrial change, they are likely unsuitable in the context of inclusive entrepreneurship for two reasons (see (Welter et al., 2017[6]) for a broader discussion on entrepreneurial diversity):

1. It is impossible to predict ex ante, which businesses will grow fast. They can be found across a wide distribution of different sectors and are not limited to the tech-sector (Brown, Mawson and Mason, 2017[7]). This is especially important to note in the context of inclusive entrepreneurship as women, immigrants, youth and immigrant entrepreneurs may self-select themselves into different sectors with lower growth potential, but this does not necessarily preclude them from growing their business. This decision is not only influenced by personal preferences but also by cultural norms and conventions.

2. A narrow understanding of business growth and scaling-up also overlooks the wider impact of business development going beyond pure growth figures (i.e. turnover or number of employees). That includes, for example, the development of highly innovative, environmentally or socially sustainable products and services. Impactful business development does not even need to be directly correlated to the business output. For example, migrant-led enterprises are on average more likely to employ immigrants, which can improve their integration into society (Bijedić et al., 2017[8]).

Therefore, this chapter considers scale-up in a broader sense. Much of the discussion will use the term “business growth” to refer to substantial growth but not at the same level as described in Box 8.1. Very few firms reach this rate of growth, and it would be expected that entrepreneurs from under-represented and disadvantaged groups are, on average, less likely to operate businesses that achieve high-growth. However, some will, and others are capable of growing their businesses at lower rates.

Why are policy makers interested in scale-up?

Start-ups are a key source of radical and disruptive innovations, and young firms contribute disproportionately to net job creation – the share of young SMEs in total job creation is about twice as large as their share in total job destruction or in total employment (OECD, 2019[1]). Older SMEs and older large firms account for the bulk of employment across EU Member States and non-EU OECD countries, but typically create fewer jobs than they destroy. This is confirmed by recent empirical research covering 20 EU Member States that found that young-small firms accounted for 40% of job creation despite accounting for 15% of total employment (Hallak and Harasztosi, 2019[9]). Moreover, the same study found that high-growth firms accounted for only a few percentage points of the population of firms but tended to create about 60% of new jobs across most countries and sectors. Among OECD countries, these few firms account for between 22% (the Netherlands) and 53% (France) of new job creation over five-year periods between 2001 and 2012 (Criscuolo, Gal and Menon, 2017[10]).

The impacts of these firms goes well-beyond job creation. Start-ups that grow in terms of employment, turnover, profitability or market share can also drive innovation, productivity growth and the competitiveness of national and sub-national economies. This can occur directly through their innovations and investments in human capital (Du and Temouri, 2014[11]), or indirectly through the generation of new demand for advanced products and services, generating knowledge spill-overs and strengthening the local entrepreneurship culture (OECD, 2010[12]; OECD, 2019[1]). There is also evidence that they can contribute to raising wage and income levels (OECD, 2019[1]).

There are considerable differences across countries in the extent to which younger firms are able to scale-up (OECD, 2019[1]). Rapid expansion of successful young firms appears to be more common in the United States than other OECD countries (Calvino, Criscuolo and Menon, 2016[13]), and there appears to be a gap between non-EU OECD countries and EU Member States (European Commission, 2016[14]). These differences can be explained by the industrial structure and size of the economy, as well as the institutional and policy settings (OECD, 2010[12]) and cultural attitudes towards entrepreneurship and risk (OECD/EU, 2015[15]).

These cross-country differences, combined with low productivity growth, persistent productivity gaps between micro-firms, SMEs and large firms, and widening wage and income gaps, have led to scale-up being a policy priority in many EU Member States and other OECD countries (OECD, 2019[1]). This is particularly true within EU Member States, where there has been a long-standing gap with the US in terms of start-up rates, availability of capital, and entrepreneurship culture (Braunerhjelm et al., 2016[16]). Consequently, there is a strong interest among policy makers in the EU to do more to promote and facilitate scale-up for start-ups with growth potential (see Box 8.2). There is, however, a need to do more to raise awareness about the untapped potential for business growth among groups that are under-represented or disadvantaged in entrepreneurship.

The European Commission's Start-up and Scale-up Initiative seeks to create opportunities for innovative entrepreneurs to become world-class leading companies. The Initiative brings together a range of existing and new actions, including:

-

Improved access to finance (e.g. a new Pan-European Venture Capital Fund of Funds was launched in April 2018);

-

Second chance for entrepreneurs (e.g. new insolvency law allows companies in financial difficulties to restructure as a way to prevent bankruptcy and avoid laying-off staff);

-

Simpler tax filings across multiple jurisdictions (e.g. simplifications of the EU VAT system).

Other key actions in the initiative include the Single Digital Gateway to facilitate online access to the information, administrative procedures and assistance services, the Enterprise Europe Network to improve connections between businesses and business support experts, and a set of measures to support the use of Intellectual Property Rights by SMEs and take action to support access by start-ups to the European public procurement market.

Source: (European Commission, 2016[14])

How many start-ups grow?

It is estimated that only 3% of start-up in EU countries grow (Svenssonn and Rodert, 2017[17]), and about the same proportion of micro-start-ups grow in OECD countries (4%) (OECD, 2019[1]). There are no consistent patterns across countries as to where firm growth occurs. Evidence from across EU and OECD countries shows that high-growth firms are in most economic sectors (Hallak and Harasztosi, 2019[9]; OECD, 2019[1]). Although high-growth firms are more common in regions with a high population density and a labour force with high skill levels (i.e. large urban areas), they can also operate in peripheral regions where their impact on net job creation and social inclusion can be significant (OECD, forthcoming[18]).

The impact of high-growth firms in the EU appears to be declining over the past two decades, likely due to the decline in the likelihood that new start-ups become high growth firms. Three possible explanations are offered by a recent study on business dynamics and job creation (Hallak and Harasztosi, 2019[9]). First, firms may be operating below their optimal scale due to imperfect information about their productivity, demand or credit constraints. Second, young innovative firms may be increasingly likely to be bought by larger companies rather than growing as independent firms. Finally, the decline in employment dynamism may be partly due to the aggregate productivity slowdown, which is linked with how labour is allocated across firms.

What is the scale-up potential among women, immigrant, youth and senior entrepreneurs?

There is mixed evidence on the potential for businesses operated by women, immigrants, youth and seniors to make substantial contributions to job creation, innovation and productivity growth. Some research suggests that, on average, many entrepreneurs in this groups do not create jobs. For example, longitudinal analysis in Austria shows that few women-operated businesses without employees grow (Korunka et al., 2011[19]), few high-growth firms in the US are operated by people under 25 years old (Azoulay et al., 2018[20]), and few refugee entrepreneurs have employees (Betts, Omata and Bloom, 2017[21]). This is also consistent with other metrics that are often associated with business growth and innovation. For example, only 3% of patent applications in Germany are made by women (Bundesministerium für Wirtschaft, 2012[22]).

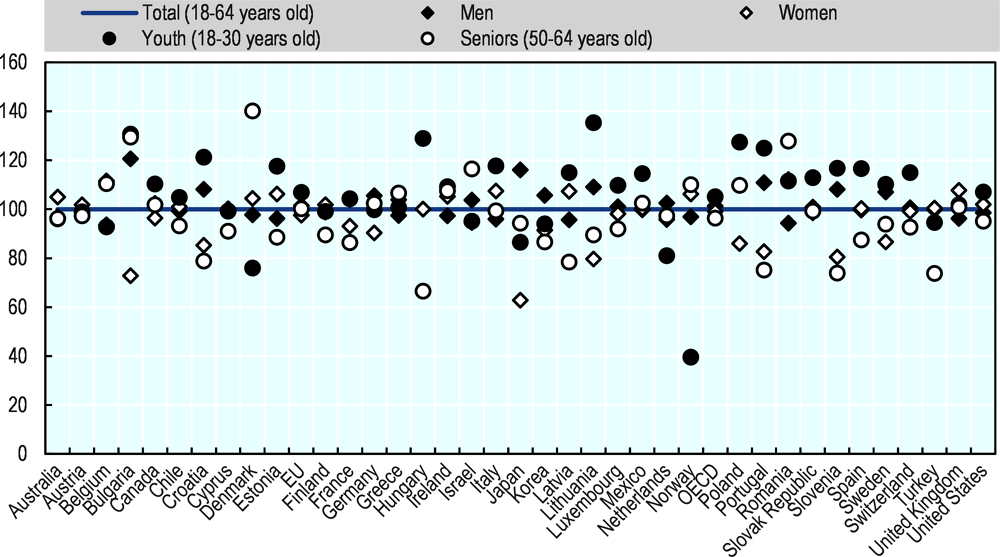

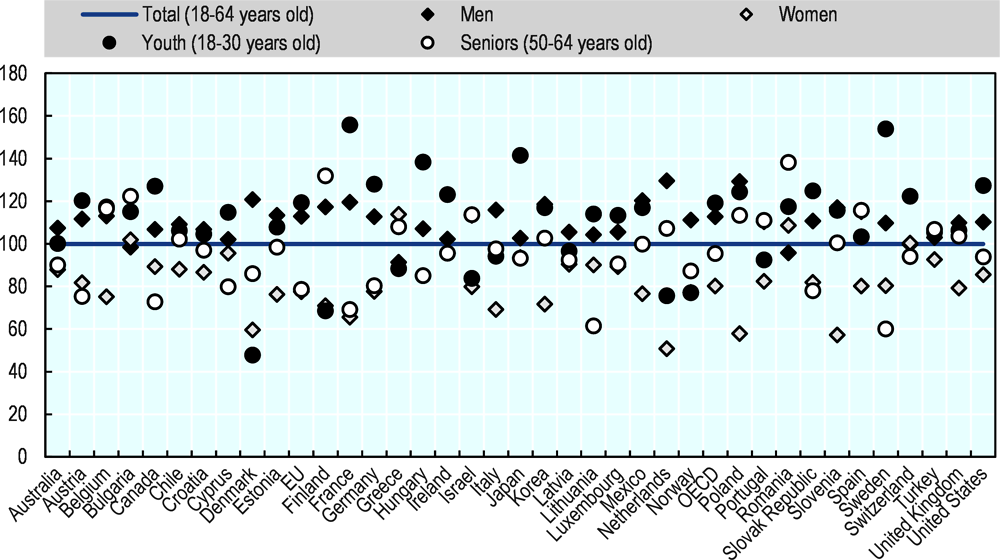

Moreover, internationally comparable data show that women and seniors are less likely to have growth ambitions than the overall average (Figure 8.1). They are also less likely, on average, to introduce new products and services that could be used to give their firms a competitive advantage (Figure 8.2) and sell to customers in other markets (Figure 8.3). This would suggest that entrepreneurs from these groups, on average, have lower potential for growth.

There is, however, evidence that some entrepreneurs in these groups do have potential for creating businesses with scale-up potential. Looking at high-growth firms, the academic literature is recognising that the factors that influence the growth motivations for women are increasingly similar to those of men (Saridakis, Marlow and Storey, 2014[24]). Programmes that support women entrepreneurs in growing their business have demonstrated some success, including Going for Growth in Ireland. In 2018, 66 participants participated in the completed the programme between January and June, and hired an additional 90 full-time and 20 part-time employees during this period (OECD/EU, 2018[25]). Nonetheless, women are less likely to operate growth-oriented firms and are more likely to operate businesses in sectors with lower growth potential (OECD/EU, 2016[26]; Lassébie et al., 2019[27]).

Evidence by entrepreneurs’ age from the US (Azoulay et al., 2018[20]) shows that older entrepreneurs appear to be much more likely that young entrepreneurs to operate high-growth firms. Although the average age of an entrepreneur that achieved high-growth in the US is 45 years old, the probability is fairly constant between 46 and 60 years old. Moreover, conditional on starting a firm, a 50 year old business starter is 1.8 times more likely to achieve high-growth than a 30 year old. Among young high-growth entrepreneurs, the probability of achieving high growth increases sharply between the ages of 25 years old and 35 years old.

Taking a broader perspective on growth, it is clear that some entrepreneurs from under-represented and disadvantaged groups have the potential to create jobs even if they are not operating high-growth firms (Box 8.3). Part I of this book shows that about one-quarter of self-employed women had employees in 2018, while the proportion was even greater among seniors (50-64 years old) and immigrants. The share among self-employed youth with employees is lower but some evidence from the EU shows that among businesses that operated between 2002 and 2005, those operated by youth had an average growth rate that was double that of businesses run by those over 40 years old (Eurostat, 2006[28]).

The evidence base on the performance of businesses operated by other target groups such immigrants and the unemployed is thinner but suggests that there are some growth prospects, particularly among high-skilled immigrants. Recent evidence from the US shows that immigrants are over-represented among entrepreneurs as well as among high-tech growth-oriented entrepreneurs (Pekkala Kerr, Kerr and Xu, 2017[29]). Research on entrepreneurs that started their business out of unemployment suggests that few are likely to generate businesses that create a substantial number of jobs. This is likely due to less access to information about business opportunities and lower opportunity costs, i.e. the decision to create a business does not detract from other income generating activities (Shane, 2003[30]). This is consistent with recent quantitative evidence from Germany, where recipients of start-up subsidies for the unemployed started businesses that generated less income, created fewer jobs and were less innovative (e.g. fewer patents filed) relative to unsubsidised start-ups (i.e. average start-ups) (Caliendo et al., 2015[31]). Nonetheless, businesses started by the unemployed had higher business survival rates, which is likely due, at least in part, to the financial subsidy.

The varied backgrounds of entrepreneurs from disadvantaged groups can also be a source potential advantages. For example, migrant entrepreneurs may be able to identify international markets, bridge cultural gaps more easily and have access to different sources of financial and/or social capital. Or, mobility restrictions may require alternate working solutions for entrepreneurs who experience disability. As such, depending on the target group, adaptation may require a stronger reliance on creative and unusual approaches, reliance on social networks or a higher effort compared to other groups (Kasperová and Blackburn, 2018[32]; Miller and Le Breton-Miller, 2017[33]).

Those who are forced to adapt to personal restrictions or specific challenges can show increased work discipline and risk tolerance. However, risk tolerance is both a positive and a negative attribute in the context of scaling-up. While it should increase the likelihood of realising intentions to scale-up, it can possibly increase the probability of business failure.

Having to rely on others can strengthen personal social skills and social networks. For example, if an entrepreneur has to rely on support from others in certain aspects of everyday life, they may become more adept at establishing contact with business partners. Facing uncommon challenges can lead to creative solutions, therefore enabling disruptive innovations (Miller and Le Breton-Miller, 2017[33]). The same duality holds true for the institutional framework. Inclusive entrepreneurship policy can act as an enabler for faster business development by reducing transaction costs, uncertainty and risks of individual behaviour (Welter and Smallbone, 2012[34]).

copy the linklink copied!Challenges to scale-up for entrepreneurs from disadvantaged groups

Scaling-up a business is a complex, dynamic process that depends on continuous adaptation and learning (see Box 8.4 for a brief overview of the factors that influence business growth). The process typically involves an evolution of the role of the entrepreneur, moving from a role that controls all aspects of the business to a position that likely requires delegating decision-making and authority. This evolution, and managing a growing number of clients, partners, suppliers, employees, products and services, and more, presents challenges for all entrepreneurs. However, entrepreneurs from under-represented and disadvantaged groups face most barriers to firm growth to a greater extent, on average. The key barriers include lower growth motivations, disincentives to scale-up in the regulatory environment, lower skill levels of entrepreneurship skills, difficulties accessing finance for business growth, and smaller and less effective entrepreneurship networks.

A number key factors impact the scale-up process, including the business environment, entrepreneur-specific characteristics and firm-specific characteristics (Welter, 2001[35]; Welter, 2006[36]).

Environmental factors

There are essentially three environmental factors that influence a firm’s ability to scale-up: market conditions, cultural norms and social attitudes, and the regulatory environment:

1. Market conditions determine the optimal size of firms within the market. This includes whether or not it is easy for new firms to enter and for incumbents to grow. The optimal firm size and firm size distribution within an industry, region or country is determined by several factors, notably economies of scale, market transaction costs, market structure, network effects and agglomeration externalities (OECD, 2019[37]). Likewise, current and expected market conditions affect entrepreneurs’ aspirations on business growth. It is important to recognise that these dynamics are changing rapidly with the emergence of the digital economy, which may lead to the emergence of winner-take-most dynamics with a small number of firms being able to exploit opportunities for enormous growth (the implications of which are subject to ongoing debate) (Andrews, Criscuolo and Gal, 2016[38]).

2. Cultural norms and social attitudes (i.e. normative institutions) can influence the availability of resources, i.e. human, financial and social capital. They can also negatively impact self-perceptions about whether entrepreneurship is a suitable activity, reduce self-confidence and even lead to discrimination. For inclusive entrepreneurship, these can have strong effects on individuals who are different from the “average” (OECD/The European Commission, 2013[39]).

3. Regulations include any rules that influence business activity, including direct (e.g. taxation, business registration, licensing) and indirect regulations (e.g. the influence of education on entrepreneurship). A restrictive regulatory environment can increase the costs of doing business and reduce opportunities. These hurdles are typically more significant for entrepreneurs from under-represented and disadvantaged groups because these individuals often have below-average skill levels and less experience in the labour market so they are less able to navigate the regulatory environment (OECD/The European Commission, 2013[39]).

Entrepreneur-specific factors

The characteristics of the entrepreneur can decisively influence the trajectory and pace of business development (Renko, Harris and Cardwell, 2015[40]; Welter, 2006[36]). For individuals, the intention to scale-up the business is crucial and can be described as how much effort an individual is willing to exert to achieve a certain outcome. It has been recognised as an important factor for successful business development (Delmar and Wiklund, 2008[41]). An entrepreneur without growth ambitions will most likely not initiate a scaling-up process despite identifying a profitable opportunity. This may be the case if entering entrepreneurship was a temporary solution (e.g. to avoid or exit unemployment) or lifestyle entrepreneurship. Long-term commitment to scaling-up may then be viewed as unsuitable (Welter, 2006[36]).

Firm-specific factors

A firm’s ability to scale-up is also impacted by its ability to access and utilise resources, i.e. skills, finance and social capital. In most cases, external resources will be required for scale-up. It should be noted, that there are various interdependencies between the individual and the business. Access to external resources for the business can be facilitated by individual resources (e.g. extensive business specific knowledge, a stable credit record, an extensive professional network).

In addition, a number of business strategies can enable scale-up, including exploiting opportunities from digitalisation and pursuing market opportunities in new markets in other countries:

1. Innovation can help companies grow through the introduction of new or improved products and services, and/or new or more efficient processes and business models that allow them to undertake their activities more efficiently and at a lower cost. To realise this potential, firms will need to invest in developing new products, services, processes and business models, or adopting those developed by other firms. Both approaches require investments in knowledge development, as well as potentially strengthening collaboration with partners and other firms, particularly within local innovation ecosystems (OECD, 2019[1]).

2. Digitalisation has created a range of new opportunities for scaling-up, including cost reductions and the creation of new business models that can challenge existing ones in radically novel ways (OECD, 2019[1]; Goldfarb and Tucker, 2017[42]). However, there is a gap in the take-up of ICT among SMEs since they face greater barriers to adoption (OECD, 2017[43]) and this gap is even greater for many entrepreneurs from under-represented and disadvantaged groups since they typically have lower levels of digital skills and fewer financial resources to facilitate the adopt new technologies (see Chapter 7). To realise the scale-up potential of the digitalisation, firms need to invest in digital skills for workers and management, and to invest in complementary knowledge-based capital, such as research and development (R&D), data, and new organisational processes (OECD, 2019[1]).

3. Internationalisation can also drive scale-up by reaching more customers (including businesses) and/or accessing new inputs at a better cost/quality ratio that reduces production costs. (These can also be facilitated through digitalisation). A related strategy is to integrate into global value chains (GVCs), which present opportunities for entrepreneurs since they allow small firms to input into production networks rather than compete on outputs (OECD, 2019[1]). This can stimulate complementary investments in technology, process innovation or organisational change (Caliendo and Rossi-Hansberg, 2012[44]). Moreover, participation in GVCs can also lead to improved productivity through competitive pressures from foreign companies, access to new inputs, and knowledge spill-overs from foreign firms (Saia, Andrews and Albrizio, 2015[45]). To fully leverage the benefits of GVCs, entrepreneurs need to be able to invest in skills, management and processes (Brynjolfsson and Hitt, 2000[46]).

Women and seniors entrepreneurs are less likely to have scale-up motivations

Entrepreneurial motivations and intentions are influenced to a large degree by cultural norms and conventions (i.e. normative institutions). This includes decisions to pursue different business activities and strategies, as well as decisions to grow a business. Typically, businesses are perceived to be more likely to have a high-growth potential if they are young and small, or are located in the typical venture-backed, high-technology sectors. This view, however, contradicts empirical evidence (Brown, Mawson and Mason, 2017[7]).

These influences of cultural norms and conventions on entrepreneurs from under-represented and disadvantaged groups seeking to scale-up manifest in four ways. First, they self-select into activities and sectors that have lower growth potential. For example, entrepreneurs who experience disability tend to self-select into social entrepreneurship (Cardwell, Parker and Renko, 2016[47]), and women entrepreneurs towards less innovative sectors (e.g. the services sector) (OECD, 2017[48]). Second, discriminatory social norms may also negatively alter the self-perception of an individual. As a result, lower self-confidence can lead to missed opportunities for business development since risks are more likely to be avoided (Welter, 2006[36]). Third, social norms can lead to discriminatory behaviour towards several groups of entrepreneurs, notably people with disabilities. This can negatively affect self-perception, but also severely hinder access to human and financial capital. Finally, cultural norms and conventions influence how entrepreneurs interact with their networks, clients, partners, suppliers and business support services (Welter and Smallbone, 2012[34]).

The gender effects of cultural norms and conventions are strong. Media coverage on female entrepreneurs often focuses on characteristics and attributes which are stereotypical perceived as feminine (Byrne, Fattoum and Garcia, 2019[49]). This may in turn promote images of types of entrepreneurship that are seen as typical or socially acceptable for female entrepreneurs (Achtenhagen and Welter, 2011[50]). High-growth potential is commonly associated with masculine terms (Gupta, Wieland and Turban, 2019[51]). This can in turn discourage female entrepreneurs from entrepreneurial activity outside of typical female domains or lower their self-confidence.

There are also differences in risk aversion. Women and youth are more likely to report a “fear of failure” (see Chapters 2 and 3), which suggests that they would be less likely to pursue riskier activities such as growing a business. This negative self-perception is a commonly cited barrier among women entrepreneurs (OECD/EU, 2016[26]), which can lead them to scale-down their growth plans despite having strong business ideas.

Moreover, entrepreneurial intentions change over the course of life. For example, younger entrepreneurs are more likely to express high growth expectations than older ones (Davis and Shaver, 2012[52]). Entrepreneurial intentions of seniors are significantly positively influenced if it is perceived as socially acceptable (Kautonen, 2013[53]; Kautonen, Down and Minniti, 2014[54]; Kautonen, Tornikoski and Kibler, 2011[55]). Older entrepreneurs more frequently pursue non-pecuniary goals (Matos, Amaral and Baptista, 2018[56]) and are less likely to focus on business growth (De Kok, Ichou and Verheul, 2010[57]; Gielnik, Zacher and Frese, 2012[58]). A shift to entrepreneurship in later life is often accompanied by a reduction in income, but a higher quality of life (Kautonen, Kibler and Minniti, 2017[59]). They also have a shorter planning horizon compared to younger entrepreneurs (Schott et al., 2017[60]). Long-term benefits of business development may be less relevant to them, especially if they are accompanied by high financial risks. In the case of failure, a senior entrepreneur might lose her life savings (Trettin et al., 2007[61]). Therefore, monetary incentives for senior entrepreneurs to focus on business growth are often of lower importance. If an entrepreneur plans to retire in the near future, the question of business succession is likely to influence the decision to invest in business development as well. The entrepreneur cannot be certain that their successor will follow their strategies, nor can they be certain that a buyer will value their investment (Pahnke, Kay and Schlepphorst, 2017[62]).

Regulations about access to benefits and tax measures can contain disincentives to scale-up for many population groups

Regulatory institutions affect business development and the influence can be both enabling and restrictive. Regulatory institutions describe any laws or rules that govern business activities such as rules regarding market entry and setting up new businesses, labor market laws, tax policies or property rights. For example, if labor market regulations are too rigid they can negatively affect entrepreneurship, especially high-growth entrepreneurship (Baughn, Sugheir and Neupert, 2010[63]). Strong protection of employees and high wages can discourage entrepreneurs from hiring additional employees. But, deregulation does not necessarily always fuel growth and innovation because this can also create insecurity and lower commitment to employers, harming long-term efficiency (Henrekson, 2014[64]).

For inclusive entrepreneurship, the strongest disincentive typically come from regulations that determine access to various benefits (e.g. unemployment benefits). Regulations that set certain limits for the eligibility of receiving benefits can also have an impact on business development. While they aim to support entrepreneurs in certain situations, they also form a barrier if the beneficiaries avoid losing the benefits. For example, entrepreneurs who experience disability may fear the loss of regular public benefits for persons who experience disability if they extend their business and pass a certain threshold (Cooney, 2008[65]).

Income splitting tax policies show contrary effects on female entrepreneurship. They can discourage female entrepreneurs from entrepreneurial activity in general or from intensifying efforts towards business development through family and tax policies promoting traditional gender roles (Sjöberg, 2004[66]).

Women, youth and senior entrepreneurs often have lower levels of entrepreneurship and management skills

Scaling-up requires, among others, restructured business processes, additional know-how or delegating tasks and responsibilities to employees. The entrepreneur’s individual resource endowments can facilitate this process and minimise the need for additional external resources. Entrepreneurs from under-represented and disadvantaged groups, on average, have lower levels of human capital. For example, migrant entrepreneurs can lack knowledge on local consumer behaviour or regulations, the latter reinforced by linguistic difficulties. Female entrepreneurs are more likely to have less business experience when they have taken parental leave (OECD/EU, 2016[26]). Senior entrepreneurs may be at a disadvantage as part of their knowledge, especially on digitisation and current trends may be outdated. Relevant sources of information, such as websites, are perceived to focus more on a younger audience (Kautonen, 2013[53]).

Moreover, acquiring human capital may be hindered due to restricted mobility, language barriers or lacking knowledge on relevant institutions. This is especially relevant for people who experience disability (Drakopoulou Dodd, 2015[67]) and, again, migrant entrepreneurs. For the former, the lack of suitable public transportation, or classes that take place in floors without elevators can exclude them from participation in regular education (Cooney, 2008[65]). For the latter, especially for first-generation migrants, it can be more difficult and time-consuming to obtain information in an unfamiliar environment (Bijedić et al., 2017[8]).

Scale-ups have higher risk, which increases the already high barriers to finance for women, immigrant, youth and senior entrepreneurs

Hiring employees and investing in new business processes and innovations need appropriate funding to fuel the scaling-up process. Entrepreneurs often have to make considerable up-front investments that only pay off at a later stage of the business development, e.g. through the realisation of innovative product ideas or business concepts. External financial capital can therefore become a significant obstacle for scaling-up, even though some entrepreneurs may be able to postpone the need for external financial resources.

In credit markets, adverse selection and moral hazard are exacerbated in the case of young, innovative businesses without loan history or collateral to secure a loan (OECD, 2019[1]). Due to their higher risk profile, fast-growing companies also typically suffer from higher loan rejection rates than averagely performing firms (OECD, 2015[68]). At the same time, traditional debt may be ill suited for new, innovative and fast-growing companies, which have a higher risk return profile.

Furthermore, the personal financial situation and the ability to acquire additional funding can be limited for entrepreneurs from under-represented and disadvantaged groups. Those who experience disability (Drakopoulou Dodd, 2015[67]) and migrant entrepreneurs (Kay and Schneck, 2012[69]) can face increased difficulties in this regard. Limited career opportunities can lower the financial capacity of entrepreneurs who experience disability, in turn hampering access to external financial means. If their disability is seen as a risk factor, this can increase interest rates (Cooney, 2008[65]). For senior entrepreneurs, their age can perceived as a risk for potential investors due to the potential health risks and shorter period to earn future returns (OECD/EC, 2012[70]).

Sector specific differences may be an important factor as well, especially regarding gender differences. Typically, technology-intensive sectors are perceived to have the highest growth potential, while female entrepreneurs are predominantly active in trade and services sectors and sectors that are less capital-intensive (OECD, 2017[48]). Low capitalisation has been a reason why banks frequently refuse credit applications of female entrepreneurs (OECD, 2016[71]; OECD/EU, 2016[26]).

Similar issues arise when entrepreneurs from under-represented and disadvantaged groups seek debt financing. In 2017, the business angel market in the EU was worth about EUR 7.3 billion, mostly concentrated in the United Kingdom, Germany, France and Spain (EBAN, 2017[72]). Generally, these investments are targeted at growth-oriented sectors (Levratto and Tessier, 2014[73]). In 2017, nearly half of business angel investment in the EU was concentrated in FinTech (25.2%) and ICT (21.3%) sectors (EBAN, 2017[72]). Entrepreneurs from under-represented and disadvantaged groups are less likely to operate in these sectors (see Chapters 2-6), which partially explains why women, immigrant, youth, senior entrepreneurs, and the (formerly) unemployed receive a small fraction of business angel investments.

Recent OECD analysis based on Crunchbase data found that raising capital is even more difficult for female-owned firms (Breschi, Lassébie and Menon, 2018[74]). Using a sample of 25 000 start-ups across a wide set of countries and sectors, female-led business ventures (i.e. those with at least one female founder) are significantly less likely to be funded. Even when they receive funding, the receive 23% less, on average, than male-led start-ups event after controlling for the location and the nature of the start-up, as well as for the education level and professional background of the founders. Female-led start-ups are also 30% less likely to have a positive exit, i.e. be acquired or to issue an initial public offering (Breschi, Lassébie and Menon, 2018[74]).

Women, immigrant, youth and senior entrepreneurs tend to have smaller and less effective networks

There is long-standing evidence that entrepreneurs from under-represented and disadvantaged groups have small and less diverse networks. Networks are groups of actors with a relationship or tie that connects them and they have an important role in facilitating access to resources, ideas and opportunities for entrepreneurs (OECD/EU, 2015[75]). A large number of factors influence access to networks, including cultural norms and conventions, discrimination, educational attainment, workplace experience and more.

The challenges to building entrepreneurship networks vary across different population groups. Women entrepreneurs, on average, tend to have informal networks with strong-tie connections, whereas men tend to have larger networks with weak-tie connections, involving business service providers and other entrepreneurs (OECD/EU, 2015[75]). Youth entrepreneurs typically lack experience in the labour market and in self-employment. This lack of experience means that they have had fewer opportunities to build connections. They also have difficulty entering networks since they have little to offer other network members. Conversely, senior entrepreneurs likely have many connections and a wealth of experience to offer others. However, their connections tend to have diminishing value if they have been out of the labour market for some time and can also face unsupportive attitudes from their closest strong ties (i.e. family and friends) and others in the community (e.g. partners, suppliers and customers). Immigrant entrepreneurs may face language challenges when interacting with relevant connections, which hinders their ability to build relationships. Moreover, there is evidence to suggest that immigrants are more likely to mistrust government and public initiatives (OECD/EU, 2014[76]). The long-term unemployed typically face multiple forms of deprivation, including difficulties accessing housing, education, health, work opportunities, and physical infrastructure.

copy the linklink copied!What can policy do to stimulate the creation of businesses with scale-up potential by disadvantaged entrepreneurs?

Build motivations and intentions for growth when appropriate

The first step to improving the scale-up potential of businesses started by entrepreneurs from disadvantaged groups is to try to increase the proportion of entrepreneurs that want to grow their business. However, this is not without caveats. Firstly, influencing the intention to scale-up can possibly result in problems regarding self-selection. Entrepreneurs that do not have the capabilities or initial intention to scale-up should possibly not be coerced into business development. Secondly, intentions cannot, for the most part, be changed in the short-term as the underlying factors are only to be influenced in a longer time-period. In the long-term, information and awareness campaigns can promote both growth ambitions and knowledge about relevant programmes.

Use role models to inspire growth

Role models are often used in promotional campaigns for entrepreneurship and they are also important when seeking to build motivations for scale-up. This is particularly important for entrepreneurs from under-represented and disadvantaged groups who may not be able to relate to a successful mainstream entrepreneur because the context around the success may be completely different (OECD/EU, 2015[15]). It is therefore important to have examples of success that are representative of the population as a whole, and specifically the target audience.

Facilitate the acquisition of entrepreneurship skills for growth

At individual and business level, policies aimed at stimulating scaling-up of entrepreneurs from under-represented and disadvantaged groups should facilitate acquiring the resources required for business growth, i.e., human, social and financial capital. Adequate training possibilities can help to build the human capital of both entrepreneurs and employees. As some entrepreneurs from under-represented and disadvantaged groups face the challenge of restricted mobility or language barriers, comprehensive and easily accessible services that are available in multiple languages, can be a viable approach.

Develop business management skills for growth

Firms that scale-up need to adjust their management practices to manage the changes in organisational dynamics brought on by growth. This likely requires new leadership and management skills to be able to cope with the rapid growth and emerging complexities such as growing sales (e.g. marketing, building new relationships); project management (e.g. logistics), finance (e.g. capital and cash flow management) and strategic thinking (e.g. building internal leadership, coordinating a growing number of actions) (OECD, 2010[77]). Entrepreneurs from under-represented and disadvantaged groups face greater challenges in these areas due to their lower level of entrepreneurship skills and less experience in entrepreneurship (OECD/The European Commission, 2013[39]).

Starting Strong in Ireland (Box 8.5) is geared toward women entrepreneurs with high-growth ambitions. The strength of this approach is that the initiative leverages coaching and peer-learning simultaneously, which is both cost-effective and also enables participants to build their entrepreneurship networks.

Target group: Women entrepreneurs with growth ambitions

Intervention type: Training, mentoring and peer coaching

Description: Starting Strong is designed for ambitious female entrepreneurs who are at an early-stage of business development. Participants’ businesses have typically moved well beyond the concept stage but remain in the early revenue stage. The initiative was developed in 2014 by the Going for Growth initiative, which was the winner of a European Enterprise Promotion Award 2015 in the Investing In Entrepreneurial Skills category. Starting Strong was launched in response to a clear demand by those who had very strong growth potential, but had not yet achieved two years revenues, which was part of the criteria for acceptance for participation in Going for Growth. To qualify for Starting Strong, candidates were required to be highly innovative, to have a longer development cycle than the norm and to have very significant growth ambitions from the outset. Having tested the initiative over two cycles, a further criterion was added- candidates must have generated at least some sales.

The initiative uses a similar approach to Going for Growth, which leverages volunteer contributions from successful entrepreneurs, who facilitate peer support round tables through a structured approach in six-month cycles. These are referred to as Lead Entrepreneurs. They share their experience with their group, nurture a culture of trust and collaboration and facilitate the sharing of experiences and challenges. This approach provides support and “good” peer pressure and inspires women entrepreneurs to achieve their goals.

There are two key differences between Starting Strong and Going for Growth. First, as the Going for Growth businesses are well established, on average six years old, they tend to have positive cash flows and an established relationship with key stakeholders, including funders and customers. The opposite is the case for the more recently established Starting Strong businesses. Related to this are differences in relation to perceived barriers to growth. The barriers that all the Starting Strong participants identify most frequently relate to funding, access to finance and cash flow. This barrier is mentioned by just over one third of Going for Growth participants. People related issues (recruitment and management) are most frequently cited by Going for Growth participants. Reflecting these differences, a set of tailored agendas and workshops have been developed to meet the specific stage of development needs and concerns of Starting Strong participants.

The initiative receives financial support from Enterprise Ireland, and financial and in-kind support from corporate sponsors.

Results achieved: The 2019 cohort has 17 participants. Total combined turnover for the businesses is EUR 2.4 million, which is an increase of almost EUR 500 000 over the cycle (21%). At the end of the cycle, nine of the participants had export experience and there were 75 people employed in the participants’ businesses.

Lessons for other initiatives: This initiative uses peer-learning, which can help participants build their networks with similarly ambitious entrepreneurs. This environment can also create some positive peer pressure to help motive the entrepreneurs to achieve their goals. As they achieve their initial growth goals and begin to grow significantly, participants of Starting Strong can apply for participation in Going for Growth. An important element of the structure of the initiative is the use of “Lead Entrepreneurs”, who may be graduates of the related initiative Going for Growth. This giving-back element reduces the need to recruit new successful entrepreneurs to help run the initiative.

Source: (Going for Growth, 2019[78])

It is important for policy makers to use hands-on learning methods such as mentoring and networking to provide the opportunities to build skills needed to manage rapidly growing businesses and expand social capital endowments by establishing contacts with more experienced entrepreneurs. While some entrepreneurs from under-represented and disadvantaged groups have networks within their groups, access to other networks can generally be difficult (Halabisky, 2015[79]). Mentoring and raising awareness towards existing business networks can be an entry point for the further development of social capital. Mentoring initiatives can be used to draw upon synergies between different types of entrepreneurs.

For example, young entrepreneurs can provide up-to-date formal education and knowledge regarding current trends and digitisation, whereas senior entrepreneurs can contribute accumulated experience. The mentors do not only need proven business experiences, but should also have been trained in working with under-represented and disadvantaged groups to ensure they understand their specific needs and potentials. For example, Unternehmerinnenbrief NRW (Box 8.6) offers business knowledge and access to networks to female entrepreneurs. It also facilitates access to potential investors.

Target group: Female entrepreneurs

Intervention type: Network, certification programme

Description: The Unternehmerinnenbrief NRW is an initiative of the North Rhine-Westphalian Ministry of Home Affairs, Local Government, Construction and Equal Opportunities. It aims to build a network to support women in starting and growing businesses and women across all sectors.

Women entrepreneurs can apply to Unternehmerinnenbrief NRW in eight regions in the Federal State North Rhine-Westphalia (NRW). Applicants must have already finished the planning phase of their business. The application process includes submitting a business plan, which is verified by an independent expert committee. Acceptance into the network is signalled by a certificate to indicate that they have a verified business plan with potential for growth.

This certificate opens up a network for other entrepreneurs, banks, business associations, chambers of commerce and business consultants that can provide advice. Each certified member is assigned a mentor for one year to provide support and advice. Those entrepreneurs that are not certified, can also access support to improve their business plan.

Results achieved: More than 300 women entrepreneurs have been awarded a certificate.

Lessons for other initiatives: The initiative can operate with few resources because it largely operates as a matchmaking system for entrepreneurs and business development support organisations. The awarding of a certificate provides can help provide additional incentives because it unlocks further business support.

Source: (Ministry of Homeland, Municipal Affairs, 2019[80])

Support the acquisition of innovation and digital skills

To increase their chances of seizing market opportunities to grow their business, entrepreneurs need to have, or be able to access, state-of-the-art knowledge and technologies that can be implemented in their business operations. It is important to recognise that innovation not only involves research and development (R&D) activities, but also the adoption of new technologies and processes, as well as the introduction of new products, services, processes and business models (OECD, 2019[1]).

Policy makers can use training programmes to build entrepreneurship, innovation and digital skills for entrepreneurs from under-represented and disadvantaged groups (see Chapter 7).

Another approach is to leverage existing innovation infrastructures such as science parks and business incubators (OECD/EU, 2019[81]). Overall, there is evidence that business incubators and business accelerators can be effective supports for new and growing businesses (i.e. improved business survival rates, greater employment creation, greater revenue growth) and evaluations suggest that similar results can be achieved in business incubators that focus on supporting entrepreneurs from under-represented and disadvantaged groups. The keys to success for these initiatives include offering strong pre-incubation services, building strong linkages with mainstream business support providers and investors, delivering support in flexible modules, and ensuring that incubator staff are trained to support the targeted entrepreneurs (OECD/EU, 2019[81]).

In addition, policy makers can help entrepreneurs link with universities and research institutions to improve their access to technical knowledge and technologies. These types of initiatives are increasingly common in the EU, and several good examples are in Austria (OECD/EU, 2019[82]) and the Netherlands (OECD/EU, 2018[83]). These types of arrangements also offer valuable learning opportunities for youth entrepreneurs in higher education. Policy makers and higher education institutions can seek inspiration and guidance on strengthening the linkages between higher education and the business community from the OECD/EU HEInnovate framework and tool (www.heinnovate.eu).

Enhance access to finance for business growth

Difficulties in accessing finance are widely recognised as one of the major obstacles for starting and growing a business and these barriers are often greater for entrepreneurs from under-represented and disadvantaged groups (OECD/The European Commission, 2013[39]; Marchese, 2014[85]). A lack of finance prevents entrepreneurs and SMEs from investing in innovative projects, improving their productivity, and seizing opportunities in expanding or accessing new markets (OECD, 2019[1]). There are several ways that policy makers can facilitate access to debt and credit for scale-up for entrepreneurs from under-represented and disadvantaged groups.

Address failures in equity markets

A common form of equity financing for growing firms is business angel investments (OECD/EU, 2015[15]). Business angels are typically individuals with a high net worth who invest in start-ups and growing businesses with the goal of making a profit in the medium to long-term. Often, business angels invest between EUR 25 000 and EUR 500 000, but can reach a much larger scale if individual investors pool their funds through networks, clubs or syndicates (EBAN, 2017[72]). It is also common for business angels to support the businesses that they invest in in other ways, including mentoring and providing access to networks and other professional resources.

Policy makers can facilitate business angel investment in businesses operated by entrepreneurs from under-represented and disadvantaged groups in several ways. First, they can facilitate the creation of business angel networks that are focused on social inclusion by subsidising the start-up and operational costs of these networks. This is most common in business angel networks that invest in growth-oriented women entrepreneurs (Box 8.7). Second, policy makers can provide training to growth-oriented entrepreneurs to improve their investment readiness. A study of proposed investment opportunities that were rejected by business angels in the United Kingdom indicates three principal reasons for rejection: (i) weakness in the entrepreneur or management team, (ii) poor marketing and (iii) flawed financial estimates and projections (Mason and Kwok, 2010[86]). Investment readiness training could address these issues. Third, governments could stimulate business angel investment by providing tax breaks, particularly for those investments in entrepreneurs from under-represented and disadvantaged groups. Fourth, governments could facilitate and improve matchmaking between investors and entrepreneurs from under-represented and disadvantaged groups. Fifth, governments could offer matching funding for business angel investments in inclusive entrepreneurship projects with scale-up potential.

Another issue is that few business angel investors are from under-represented and disadvantaged groups. For example, women account for only a small proportion of angel investors. In Central and Eastern Europe, women accounted for a lower proportion than in Western European (30% vs. 11%) and in the US, it is estimated that 20% of angel investors are women (EBAN, 2017[72]). Most research suggests that investor homophily leads to under-investment in businesses operated by entrepreneurs from under-represented and disadvantaged groups (i.e. investors are more likely to invest in entrepreneurs like themselves) (Lassébie et al., 2019[27]).

Target group: The business angel network targets women investors; the network invests in innovative entrepreneurs (male and female) seeking between EUR 100 000 and EUR 1 million.

Initiative type: Early-stage funding for start-ups.

Description: Femmes Business Angels was created in 2003 by a small group of women investors who were interested in promoting and supporting women in the economy and entrepreneurship. The network aims to invest in both male and female entrepreneurs.

Femme Business Angels is the only women business angels network in France, and the largest in Europe. There are currently about 150 women business angels who are members. To become a member, the business angels must commit EUR 20 000 to invest over two years and apply for membership after attending at least one of the network’s monthly meetings and meeting the board of directors. Members are also obliged to follow a code of ethics.

The projects that the network supports must be innovative and seeking between EUR 100 000 and EUR 1 million. Potential projects are reviewed by a team of angels but the investments are made independently as individuals.

The group was initially founded with support from the France Angels network and Conseil général d’Ile de France (i.e. local government). It now has a large number of partnerships with private sector corporations and business incubators. The network also receives support from Bpifrance, a public investment bank

Results achieved: Since its creation, network members have invested more than EUR 10 million in more than 150 start-ups.

Lessons for other initiatives: This is an example of a bottom-up initiative that has slowly grown with support from both public and private partners. It is an example of how policy makers can leverage initiatives launched by the private or non-profit sectors rather than creating something new and potentially duplicating ongoing activities.

Source: (Femmes Business Angels, 2019[88])

Venture capital (VC) is a form of early-stage investment that specifically seeks to support new start-ups with high-growth ambitions. This form of finance is receiving growing interest from policy makers because access to early-stage financing is a key determinant of success for high-potential start-ups (Lassébie et al., 2019[27]). It is, however, very rare for start-ups to receive formal venture capital investments, and even rarer for entrepreneurs from under-represented and disadvantaged groups. For example, a recent analysis of Crunchbase data (i.e. a private database with micro data on venture capital investments) found that women-operated start-ups are less likely to receive venture capital than male-founded ones and tend to receive less capital when they do receive financing (Lassébie et al., 2019[27]). This represents a missed opportunity to harness the growth potential of many new start-ups.

Policy can address barriers on both the entrepreneur side (e.g. improving investor readiness) and the investor side (e.g. increasing diversity among those making investment decisions) of the market (OECD/The European Commission, 2013[39]). In addition to closing gaps in terms of growth ambitions and the types of businesses operated, policies to improve access to venture capital for entrepreneurs from under-represented and disadvantaged groups should focus on training to boost investor readiness. Investor-homophily can be mitigated through government-backed VC funds that target specific groups or entrepreneurs, or have quotas. There is a growing number of examples of public institutions that seek to improve access to risk capital by directly offering funding (e.g. Competitive Start Fund for Female Entrepreneurs, which is operated by Enterprise Ireland). However, there are few evaluations of such approaches so it is not clear if this approach leads to an effective allocation of funds.

Improve access to debt financing for business growth

Debt financing also has a role in supporting business growth. Policy support for loan programmes that are geared to support growth are often delivered through business agencies or microfinance institutions. The most important element of public support and funds used in debt financing is to ensure that the screening mechanisms are able to select the business projects with reasonable chances of success. This can be difficult because growth-oriented projects typically have higher levels of risk associated with them. Supporting entrepreneurs from under-represented and disadvantaged groups introduces an additional element of risk since these entrepreneurs, on average, are less likely to succeed. In addition, the often have personal characteristics that make it more difficult assess past behaviour, e.g. many lack a credit history.

To improve access to debt financing for business growth, an effective approach is to operate small targeted funds for groups that have the greatest chances of success. In practice most examples are targeted at youth and women. One example of an initiative for growth-oriented youth entrepreneurs is the ENISA Young Entrepreneurs Facility (Box 8.8). This programme provides loans to innovative youth entrepreneurs and offers lower interest rates to more profitable businesses. One of the keys to success for this loan programme is that it provides incentives and rewards for borrowers that perform well.

More generally, the evaluation evidence points to two important success factors of loan programmes: strong monitoring efforts and timely interventions by the lender when repayment instalments are delayed (Marchese, 2014[85]). It is important that financial support is packaged with appropriate training, business development services, coaching and mentoring to help ensure that entrepreneurs can effectively use the financing (OECD/The European Commission, 2013[39]; Marchese, 2014[85]).

Target group: Entrepreneurs under 40 years old

Initiative types: Loans

Description: ENISA is a state-owned company under the responsibility of the General Directorate of Industry and SMEs in the Ministry of Industry, Commerce and Tourism. Its mandate is to provide financial support start-ups and newly created SMEs that are seeking to bolster their innovation activities.

The Young Entrepreneurs line of credit offers loans of EUR 25 000 to EUR 75 000, repayable over seven years. The interest rate charged is the Euribor rate + 3.25%, plus a variable rate (between three and six percentage points) that inversely depends on the profitability of the company. A bank endorsement is not needed to secure a loan.

Eligible firms are those that are under 24 months old and operated by someone under the age of 40 years old. Entrepreneurs are required to provide at least 50% of the value of the approved loan in financial capital or own funds.

The loans can be used to acquire fixed assets and fund operating activities. Firms operating in real estate and financial sectors are not eligible for loans.

Results achieved: A recent evaluation (Martí Pellón, 2018[89]) reported that the Young Entrepreneur Facility issued a total EUR 63.7 million to 1 380 borrowers between 2009 and 2013. By 2015, these entrepreneurs had created 2 494 additional new jobs. From a cost-benefit perspective, 57.6% of the principal borrowed had been paid back by June 2017 and the estimated cost per job created was EUR 3 800.

Lessons for other initiatives: There are strong incentives for the young entrepreneurs to succeed because the cost of the loan is related to the success of the company. Those that are more profitable are provided financing with lower interest rates.

For more information, please see: https://www.enisa.es/en

Build networks and eco-systems that support growth for all entrepreneurs

The concept of the local entrepreneurship ecosystem has gained traction in recent years as a way to conceptualise and build a supportive business climate. This concept focusses on the individual entrepreneur, rather than the “cluster” or “industrial district” approaches that focus on firms (Stam, 2015[90]; Stam and Spigel, 2016[91]; Autio, 2011[92]). Fostering entrepreneurship ecosystems means seeking to improve the setting and conditions within which entrepreneurs work (Malizia and Motoyama, 2016[93]).

While the literature on entrepreneurship ecosystems is largely descriptive, it is believed that the success of ecosystems is dependent on the number, diversity and capabilities of actors – including entrepreneurs, business development organisations, etc. – the strength of networks and learning opportunities between them, level of innovation, the governance and co-ordination of actors and a culture of risk-taking (OECD, 2019[94]).

Local authorities often play a key role in the development of a conducive business environment, including through partnership with the business community, research organisations and investors. Multilevel governance is an important dimension of any coordinated policy approach to SME growth (OECD, 2019[1]). The SPEED UP programme (Box 8.9) is an example of how cities and regions are working together to share good practice and learn about innovations in the delivery of business development. One of the participating regions is Flanders in Belgium, led by the City of Antwerp. It has selected the theme of supporting “target audiences” as its key issue, notably supporting the development of businesses led by women, youth and immigrants.

Target group: Innovative businesses operated by youth, women and immigrant entrepreneurs.

Intervention type: Peer-learning project for cities about supporting entrepreneurs business development infrastructure, notably business incubators.

Description: SPEED UP is an international programme that aims to trigger policy change and improve the implementation of the policy instruments that support entrepreneurship in participating cities and regions. The programme facilitates a learning process that engages policy makers, partner organisations and relevant stakeholders in an exchange of experiences about what works in supporting entrepreneurs through business incubators and other support infrastructure. The objective is to develop a shared ownership of programmes and ensure that encourage ecosystems to learn from each other. The programme is support by the EU Interreg Programme. Participating regions are: Tuscany Region (Italy), Region of Lisbon (Portugal), State of Brandenburg (Germany), Region of Flanders (Belgium), Champagne-Ardenne (France), Andalusia (Spain), and Mazowieckie Voivodeship (Poland). Each participating region selects a special theme that will be explored when they host the other regions for study visits.

In Flanders, the City of Antwerp is the leading organisation, but other key stakeholders that are engaged in SPEED UP, including Start it @kbc, imec, Startups.be, University of Antwerp, TakeOffAntwerp_Alliance, The CoFoundry, Netwerk Ondernemen, The Birdhouse, VOKA Bryo, Duval Union, and the BlueHealth Innovation Center. One of the most significant activities organised by the City of Antwerp was an international conference on “target audiences”, which looked at specific actions for promoting entrepreneurship among youth, women or immigrants. The city received seven international delegations for the event (Berlin, Lisbon, Tallinn, Warsaw, Reims, Seville and Florence), including key stakeholders from each city. On 21 and 22 March 2017, participants presented and exchanged on best practices on stimulating entrepreneurship among these target groups and visited man of the business development actors in Antwerp.

Results achieved: Participants in the two-day event in Antwerp reported an increased awareness about the challenges faced by innovative businesses, especially those operated by youth and women. They also learned about how different actors in the ecosystem provide targeted support to youth, women and immigrant entrepreneurs and the key success factors for different types of interventions.

Lessons for other interventions: This example demonstrates the importance of peer-learning across entrepreneurship ecosystems. While context is important, these types of events can help build connections across actors and provide inspiration about new approaches and innovations in entrepreneurship support.

Source: (City of Antwerp, 2017[95]; City of Antwerp, 2018[96])

Remove hindrances to growth in the regulatory environment

Policy makers continue to simplify administrative obligations for entrepreneurs and SMEs. The aim is to reduce the costs and amount of time spent on complying with regulations. These ongoing efforts are important but there are several other areas where more can be done to facilitate business growth.

The efficiency of the court and legal system is particularly important for SMEs, which typically need to divert a higher share of resources than large firms to resolving disputes (OECD, 2017[98]). Efficient judicial systems are intrinsically related to larger average firm size and tend to improve the predictability of business relationships. Conversely, there is some evidence that weak judicial systems hamper firm growth because firms are less willing to establish partnerships with other firms (Johnson, McMillan and Woodruff, 2002[99]). Moreover, weak contract enforcement also leads to low levels of relationship-specific investments, which can further constrain growth prospects (Nunn, 2007[100]).

Intellectual property rights (IPRs) are useful tools for entrepreneurs SMEs to protect their innovations and intellectual property, especially when products can be easily replicated by others. Strong IPRs can increase the perceived value of the firm, which can improve access to external sources of finance as well as attract knowledge and commercial partners (OECD, 2019[1]). Weak property rights have a negative impact on high growth aspirations (Estrin, Korosteleva and Mickiewicz, 2011[101]; Estrin, Korosteleva and Mickiewicz, 2009[102]). Entrepreneurs and SMEs often encounter challenges using IPRs when operating internationally, due to high costs, the need for multiple filings, regulatory and technical differences across countries and the robustness of IP enforcement in different jurisdictions (OECD, 2019[1]). Policy makers could do more to streamline procedures and reduce application costs and time, particularly in industries where innovation occurs at a rapid rate. It is also important to improve litigation and enforcement mechanisms for entrepreneurs and SMEs that operate internationally. This requires improved IP information, coordination and enforcement across jurisdictions, likely provided by international treaties (OECD, 2019[1]).

Policy makers also need to ensure that employment protection legislation (i.e. the rules of hiring and firing) is appropriate. While they have an important role in labour markets by protecting workers’ rights and building long-term relationships between employers and employees, they can restrict high-potential entrepreneurship (Baughn, Sugheir and Neupert, 2010[63]). Evidence shows that stricter employment protection legislation leads to slower firm growth in sectors which are more labour-intensive, more innovative, or characterised by greater uncertainty (OECD, 2019[1]). Moreover, strict labour protections appears to reduce growth among the best performing firms and contraction among the underperforming ones (Calvino, Criscuolo and Menon, 2016[13]; Bravo-Biosca, Criscuolo and Menon, 2016[103]).

Most of these actions would support scale-up for all growth-oriented entrepreneurs, but it is likely that entrepreneurs from under-represented and disadvantaged groups would benefit disproportionately since many have greater difficulties navigating the regulatory environment due to a lack of experience and/or lack of language skills (OECD/The European Commission, 2013[39]). There are also some actions that policy makers can use to address the challenges for specific groups.

Ensure bankruptcy laws are entrepreneur-friendly, particularly for youth entrepreneurs

Bankruptcy laws that ensure strong guarantees for investors without posing an excessive burden on entrepreneurs in case of failure can help stimulate investment for growing businesses (OECD, 2019[1]). Moreover, personal bankruptcy regulations that are entrepreneur-friendly can help support business creation and growth as the consequences of business failure are less damaging for personal finances (Lee et al., 2011[104]). Improving the efficiency of bankruptcy procedures for corporations can help reallocate resources to more efficient uses, improving labour productivity and value-added growth (Succurro, 2012[105]). This is particularly true in sectors that are most dependent on external finance. Several OECD countries have reformed their bankruptcy regulation to allow for automatic discharge, i.e. discharge takes place at the payment of the quota agreed upon in the enterprise insolvency proceeding, with no need for an additional court decision (OECD, 2017[98]). These issues can have a positive impact on youth entrepreneurs, as they are the most likely to have their personal financial situation impacted, i.e. they have major life events in the future.

Use regulatory impact analysis to assess impacts of new policies and regulations on under-represented and disadvantaged groups