Issue Note 2: Corporate sector vulnerabilities during the COVID-19 outbreak: Assessment and policy responses

This note investigates the financial vulnerability of non-financial firms associated with the confinement measures introduced in most economies to tackle the COVID-19 pandemic. Based on empirical simulations, it evaluates the extent to which firms may run into a liquidity crisis and discusses the immediate steps that governments can take to reduce the risks and depth of such crisis, ensuring that it does not turn into a solvency crisis.

Introduction

The health crisis caused by the COVID-19 outbreak has led public authorities to take unprecedented measures to contain the propagation of the virus. Administrative business shutdowns, quarantines and restrictions on mobility and social contact have brought large parts of economies almost to a standstill (OECD, 2020a). Sales across many sectors have plummeted. Nevertheless, financial commitments with respect to suppliers, employees, lenders and investors remain, depleting liquidity buffers of firms. The sharp reversals in earnings expectations for companies has significantly weakened their projected interest coverage and profitability ratios (OECD, 2020b). The large number of firms that are simultaneously affected constitutes a major challenge. Producers of intermediate goods or services have also experienced a drop in sales even if confinement measures do not require them to shut down. Since many firms along supply chains face liquidity shortfalls, trade credit losses may increase, further adding to cash-flow pressures.

The liquidity crisis may turn into a global corporate solvency crisis. With much less or no incoming revenues for an extended period of time and fewer options to deal with this shortfall, the long-term viability of firms is impaired, and firm voluntary closure and bankruptcies may follow. Human and organisational capital would be eroded and may vanish with defaults of firms that prior to the virus outbreak were profitable and with healthy balance sheets. Global value chains will be disrupted if highly integrated firms have to exit the market. High uncertainty about the future course of the economy will reduce corporate investment and consumption demand. As a result, a corporate solvency crisis could have serious long-term negative effects on economies by dragging down employment, productivity, growth and well-being.

The risk of a financial crisis is high. In the absence of a robust policy response, corporate defaults of a significant number of firms would undermine balance sheets of banks and institutional investors. This could close markets for debt and equity financing, and might feed a self-reinforcing downside spiral in the corporate sector, in turn significantly increasing the likelihood of a crisis. Moreover, bankruptcies across a wide set of firms combined with bailouts by governments of systemic firms might decrease competition, with consequences for future productivity growth.

Awareness of these risks has lead governments to adopt a range of emergency measures aimed at supporting firms’ liquidity. Aside from monetary measures taken by central banks, fiscal interventions include direct and indirect financing of the wage bill (including by extending the coverage and increasing the unemployment benefit replacement rate, short-term work schemes and temporary unemployment benefits), tax deferrals, debt moratoria and extension of state loan guarantees.

This note evaluates the risk of a widespread liquidity crisis using a cross-sector sample of almost one million European firms and discusses the pros and cons of different kinds of public support measures. The analysis covers all manufacturing and non-financial services sectors.1 The note focuses on the first-round effects of the containment measures induced by the crisis, abstracting from the potential cascading effects via supply chains, financial interconnections between firms and financial distress in the banking system – other than those implicitly assumed in the size of the sectoral shocks – as well as from the structural adjustments that will be needed in a second phase of the response to the crisis.2

Based on illustrative assumptions regarding the evolution of sales and elasticities of costs to sales, the note sheds light on the risk of corporate insolvency.3 Comparing the percentage of firms that would turn illiquid under a no-policy change scenario and under policy intervention, the results emphasise the key role of policies to avoid massive unnecessary bankruptcies. The main findings of the analysis are summarised in Box 2.1.

Without any policy intervention, 20% of the firms in the sample used would run out of liquidity after one month, 30% after two months and 38% after three months. If the confinement measures lasted seven months, more than 50% of firms would face a shortfall of cash. This result is mainly driven by the impact of the confinement in the most hit sectors.

Firms facing a high risk of liquidity shortfalls are mostly profitable and viable companies. However, a sizeable share of these firms do not have enough collateral to bridge a shortfall in liquidity with additional debt and/or are too highly leveraged to bridge the crisis through further bank loans.

Among the wide and complementary range of measures introduced by OECD countries, direct and indirect support to wage payments seems to be the most critical policy to curb the liquidity crisis, given the high share of wage costs in total spending.

Adding up different policy measures (tax deferral, debt moratorium and wage subsidies at 80% of the wage bill), the simulation suggests that after two months government interventions would decrease the percentage of firms running out of liquidity from 30% to 10% compared to a non-policy scenario.

The risk of liquidity shortages is high for a large portion of firms

Measures on social distancing and mobility restrictions dramatically affect services involving direct contact between customers and providers, activities gathering people in public and private places, and travelling, as well as non-essential manufacturing and construction activities involving close physical contact among workers. Activities that can be undertaken remotely or automatised are relatively less affected — to the extent that the supply chain is not broken and consumer demand can be maintained, at least in part. It follows that the decline in activity is assumed to be different across sectors but identical across countries.

Consistent with OECD (2020a) and Chapter 2, Issue Note 1, the following declines in revenues are assigned to a set of severely hit sectors: 100% in manufacturing of transport equipment (ISIC V29-30), real estate services (VL), arts, entertainment and recreation (VR) and other service activities (VS); 75% in wholesale and retail trade (VG), air transport (V51), and accommodation and food services (VI); and 50% in construction (VF) and professional service activities (VM).4 For the remaining non-financial sectors a conservative 15% revenue shock is assumed, while providing sensitivity analyses assuming a larger decline (e.g., a 30% shock).

Three alternative scenarios are considered with respect to the duration of the shock.

A “prolonged confinement” scenario, which projects the evolution of firms’ liquidity positions month by month since the start of the confinement, hence being agnostic on its length and avoiding modelling the recovery.

A “single-hit” scenario, which foresees a sharp drop in activity lasting two months, followed by a four-month progressive recovery and a return to pre-crisis activity levels from the seventh month after the start of the pandemic.

A “double-hit” scenario, which overlaps with the “single-hit” scenario for the first seven months but then models a second outbreak from the eight month onwards.

The “single-hit” and “double-hit” scenarios have the advantage of being closer to the predicted evolution of the pandemic and consequent confinement over time. However, the stylised “prolonged confinement” scenario provides a neat overview of firms’ resilience in a simpler way, relying on a smaller set of assumptions on the path of the recovery and, therefore, it is used as the baseline throughout the note.

A stylised accounting exercise allows to calculate the share of firms that become illiquid month by month following the introduction of confinement measures for each scenario. The economic shock from measures of social distancing is modelled as a change in firms’ operating cash-flow, resulting from the decline in sales and from firms’ limited ability to fully adjust their operating expenses. Next, the liquidity available to each firm is calculated as the sum of the liquidity buffer held at the beginning of each month and the shock-adjusted cash-flow (Box 2.2).

The approach relies on financial statements of non-financial corporations from the Orbis database, provided by the consulting firm Bureau Van Dijk, which collects balance sheet data on both listed and unlisted firms worldwide. After the application of standard data cleaning procedures and the exclusion of small firms to avoid concerns related to the quality of the data (e.g., those having less than 3 employees), the final sample consists of 890,969 unique firms, operating in both manufacturing and business non-financial services industries.

Orbis is the largest cross-country firm-level dataset available and accessible for economic and financial research. However, the extent of the coverage varies considerably across countries. To deal with data limitations, the note focuses on 14 relatively well-covered European countries, and purposely avoids in-depth cross-country comparisons, as well as the provision of absolute numbers on the aggregate depth of the shortfall.1 Moreover, firms in Orbis are on average disproportionately larger, older and more productive than in the population, even within each size class. The analysis is hence expected to deliver a lower bound for the liquidity shortages potentially affecting non-financial corporations.

The study assumes that the last available data for each firm (end of 2018) represents its financial situation in normal times with respect to its average revenues, operating expenses, debt payment and taxes. The economic shock from measures of social distancing is modelled as a change in firms’ operating cash-flow. To reflect firms’ adjustment capacity, elasticities of intermediate costs to sales and of the wage bill to sales are estimated by assuming, for simplicity, that they are identical and constant across countries and sectors. Each month, firms’ shock-adjusted cash-flow (assuming zero investment spending) is determined as follows:

(1)

where , , refer, respectively, to the size of the shock in sector s in month t, the elasticity of intermediates cost to sales, and the elasticity of wage bill to sales. Firms’ sales, intermediate costs, wage bill, taxes and debt payments are annual values divided by 12 to obtain average monthly values.

The elasticities of intermediate inputs to sales and of the wage bill to sales are estimated through a panel regression analysis based on yearly data. The former is close to unity, while the latter is estimated around 0.4. As expected, these calculations suggest that firms have a higher ability to adjust intermediates consumption than labour input. To take into account the fact that the ability to adjust is lower when looking at monthly rather than annual figures, in line with Schivardi and Romano (2020), both elasticities are conservatively reduced to 0.8 and 0.2, respectively.

Next, the liquidity available to each firm is calculated month by month as the sum of the liquidity buffer held at the beginning of the period and the shock-adjusted cash-flow, assuming zero investment spending:

(2)

where refers to the liquidity remaining from the previous month and is equal to a firm’s cash holdings in the first period.

← 1. ountries included in the sample are: Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Spain, Sweden and the United Kingdom.

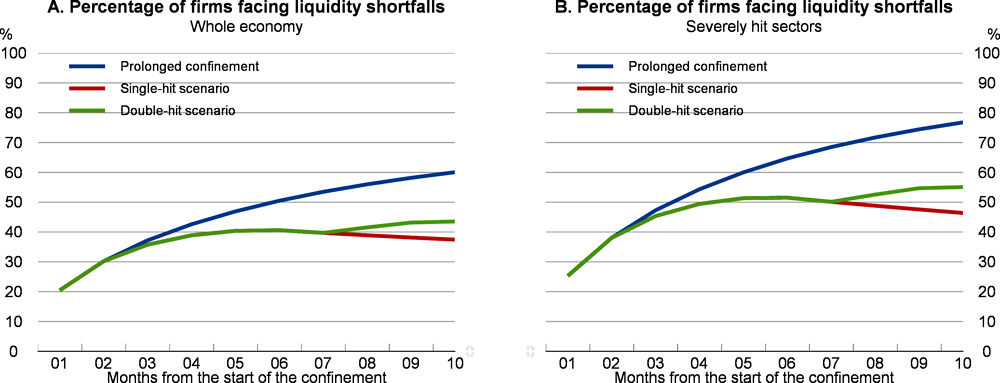

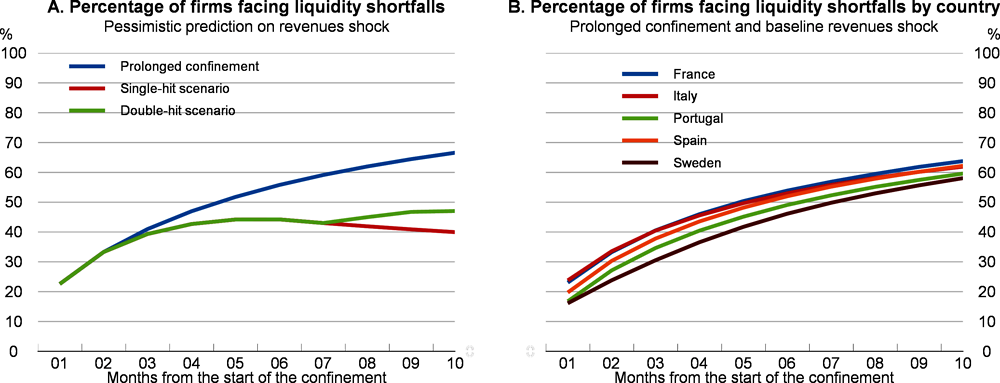

The main results (Figure 2.10, Panel A) suggest that, in the absence of government intervention, 20% of firms in the sample would run out of liquidity after one month, 30% after two months, and around 35-38% (depending on the scenario considered) after three months. If the confinement lasted seven months, more than 50% of firms would face a liquidity shortfall in the “prolonged confinement” scenario. By contrast, assuming that economic activity progressively resumes after two months of confinement, as in the “single-hit” and “double-hit” scenarios, the percentage of firms facing liquidity shortfalls would reach 40% after seven months. This share would increase to 45% after 10 months in the case of a second confinement wave (“double-hit” scenario).5 The percentage of firms running out of liquidity is significantly higher when focusing on the most severely hit sectors (Figure 2.10, Panel B). For instance, in these sectors the percentage of illiquid firms would rise up to 70% (50%) in the “prolonged confinement” (“single-hit” or “double-hit”) scenario after seven months.

It is important to stress again that these estimates are likely a lower bound given the sample bias towards healthier firms and the conservative assumptions made on elasticities. At the same time, to reflect the decision of most governments to provide general support to firms in the first stage of the crisis, the simulations include also firms that would have faced liquidity shortfalls even in the absence of the COVID-19 pandemic. After one month, the percentage of such firms ranges between 1.5% and 6.5%, depending on cash-flow in normal times. Thus, even when considering the 6.5% upper bound estimate, the COVID-19 crisis would imply a threefold increase in the share of firms experiencing liquidity shortages after one month.

Overall, the findings suggest that, due to the COVID-19 crisis, a large amount of otherwise profitable firms would run into a liquidity shortfall that may trigger bankruptcy. This shock could therefore have large and permanent adverse effects.

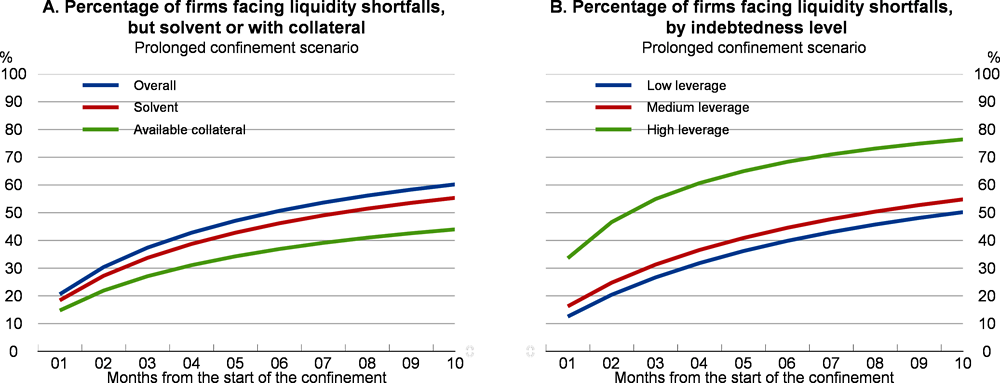

Firms facing liquidity shortages are often solvent, but their access to additional debt financing may be limited due to low collateral

Firms may run into a liquidity shortfall if their assets are not liquid enough to cover current expenses. However, they may still be solvent if the value of their assets is larger than the value of their liabilities or, equivalently, if they have collateral to pledge in order to obtain additional bank financing (Figure 2.11, Panel A).6 Only a relatively small percentage of firms (around 10%) among those expected to face liquidity shortfalls would be close to insolvency when evaluating their overall net worth. At the same time, even though solvent, they might have difficulties in accessing new bank financing: around 28% of firms turning illiquid during the confinement would lack the collateral to tap into additional debt financing. Moreover, a decrease in asset valuations during the confinement would reduce the value of firms’ potential collateral, further impairing their ability to obtain funding. Similarly, and despite its development over the last two decades, market-based financing from non-banks might also be affected, as the price of traded debt rises in periods of acute market stress, and so does the business’ cost of financing (OECD, 2020c). Finally, highly leveraged firms tend to have a higher probability of facing liquidity shortages. Combined with the high uncertainty about sales and other incoming cash-flows in the near future, this makes obtaining new loans more difficult (Figure 2.11, Panel B).

While these figures are based on several assumptions and must be interpreted with caution, they underline the merit of swift and decisive public intervention to safeguard companies and avoid potential bankruptcies of otherwise healthy companies. Such intervention is crucial to prevent the temporary shock implied by the COVID-19 crisis from permanently scarring the corporate sector, with serious consequences for the shape of the recovery and long-run growth prospects.

Public policies to reduce liquidity shortages and curb bankruptcy risk

Countries have already introduced a wide range of measures to help firms deal with the disruptions associated with COVID-19 (Box 2.3). The simple accounting model described above is used to illustrate the expected impact of stylised policy interventions in three areas:

Deferral of tax. To support businesses during the pandemic, several countries have introduced tax deferrals. The tax deferral is modelled as a moratorium of (hypothetical) monthly tax payments.

Financial support for debt repayment. A large number of countries have also established legislative frameworks that temporarily allow firms to postpone their debt payments or alternatively offer state guarantees to facilitate access to short-term debt facilities. The potential impact of such policies is modelled as a moratorium on short-term debt.

Temporary support to wage payments. A critical response to avoid widespread liquidity shortfalls consists of relaxing firms’ financial commitments vis-à-vis their employees. Schemes such as a shortening of working time, wage subsidies, temporary lay-offs and sick leave have been introduced across countries, though in different combinations. All these measures reduce the wage bill firms have to pay. They are modelled in two alternative ways: as an unconditional reduction of the wage bill by 80% in all sectors;7 and as a support adjusted to the sectoral size of the shock and modelled through an increase to 0.8 of the elasticity of wage bill to sales.8

This box provides some examples of concrete measures OECD economies have implemented to support workers and companies through the COVID-19 crisis. The OECD Covid tracker gives a more detailed overview of country-level health and economic measures adopted. Tax policy measures to tackle the COVID-19 crisis are summarised in the Tax Policy Database in Response to COVID-19 Pandemic (OECD, 2020d). Additionally, several OECD economies have introduced policy responses targeted specifically at SMEs (OECD, 2020e).

Many OECD countries subsidise temporary reductions of hours worked in firms impacted by confinement measures. Austrian authorities, for example, support wages of workers in all sectors (except public service) of up to 90% of the net salary. The scheme allows to temporarily reduce the number of hours worked to zero, however, workers are required to work at least 10% of the working-time calculated over the full period in which the firms receives support through the short-time work scheme. The maximum period of support through short-term work is three months (and might be extended to six months if necessary). The total amount taken over by the government varies with the gross salary. For gross salaries up to EUR 1,700, authorities pay 90% of the net salary. Workers with salaries below EUR 5,370 still receive 80% of their salary, whereas higher salaries are not subsidised.

Another set of measures consists of financial support for debt repayment. The Business Credit Availability Program (BCAP) in Canada, for example, supports access to financing during the COVID-19 crisis in various ways for firms across all sectors. Small businesses with up to CAD 1.5 million in total payroll costs in 2019 can receive interest-free loans up to CAD 40 000 to cover operating costs (e.g. utilities, payroll, rent, debt service). These loans are fully guaranteed by the public. One-fourth of the loan is forgiven if it is repaid by the end of 2022. If not, the loan will be automatically converted to a three-year loan at a 5% interest rate. Larger businesses can tap additional bank-based debt financing up to a total loan amount of CAD 6.25 million, guaranteed to up to 80% by the authorities. These loans comprise only operating costs and cannot be used to fund dividend payments, share repurchases and other shareholder payments, increases in the compensation of executives or to refinance or repay existing debt.

Besides guaranteed loans, a couple of OECD countries directly subsidise firms' operating costs. Norway, for example, compensates Norwegian firms that suffered significant losses of turnover due to the COVID-19 crisis. All taxable registered companies in most sectors (except oil and gas, financial industry and utilities) in Norway are eligible for this compensation under the condition that they were not already in financial distress before the crisis.

Temporary reductions in tax rates or deferrals of tax or social security payments constitute a further possibility to prevent liquidity shortfalls in the short term. Korea has introduced a temporary special tax reduction for SMEs located in COVID-19-related disaster areas until the end of 2020. VAT payments by small businesses, i.e. businesses with less than KRW 80 million in annual revenues, are reduced as well until the end of 2020. Small businesses can further defer taxes up to one year and social security contributions up to three months.

Several OECD economies have complemented subsidies, loan guarantees and tax-related measures with “soft” tools to ensure repayments and to safeguard operating cash-flow. In France, for example, the authorities actively support mediation over credit conflicts between private parties with a free, fast and reactive mediation service. French SMEs can also mobilise credit mediation if they experience difficulties with one or more financial institutions. Furthermore, the Ministry of Economy and Finance has set up a crisis unit dedicated at inter-company credits to monitor the use of trade credit.

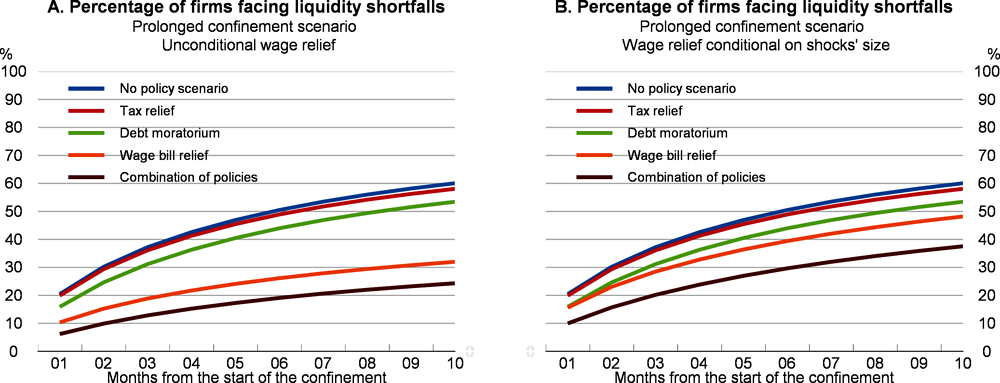

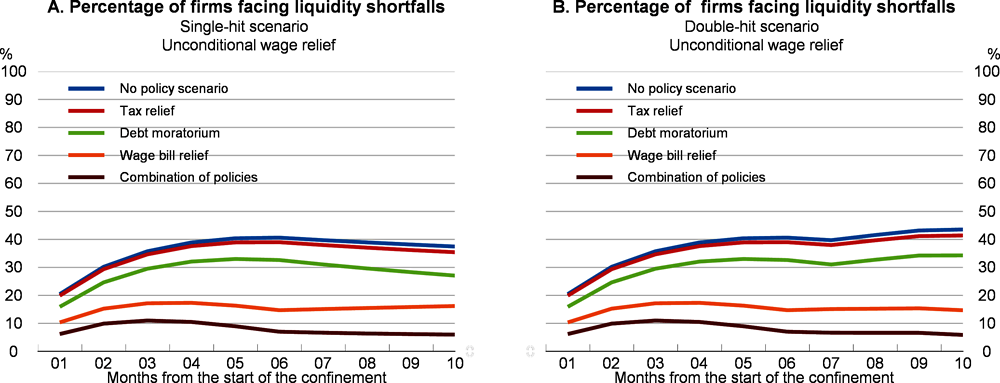

Figures 2.12 and 2.13 illustrate the extent to which each measure curbs the risk of a liquidity crisis compared to the no-policy intervention scenario. In particular, Figure 2.12 looks at the two alternative temporary supports to wage payments under the prolonged confinement scenario. Figure 2.13 further distinguishes between the “single-hit” and “double-hit” scenarios when assuming an unconditional reduction of the wage bill by 80% in all sectors. Tax deferral has the lowest impact on firms’ liquidity positions, followed by debt moratorium policies. Subsidies to the wage bill seem to be the most powerful measure (yet potentially costly), in line with the fact that wages and salaries are often a relevant component of operating expenses. Adding up the three different measures, public intervention after two months, for instance, would decrease the number of firms running out of liquidity from 30% to 10%.

These findings emphasise the need for massive public intervention, with support to wage payments emerging as the most critical among the wide range of measures aimed at alleviating liquidity crises, but there are several challenges related to the design of these measures that will need to be addressed in the future. In particular:

Country-specific dimensions. Country-specific institutional settings may shape the extent and the efficiency of the policy response. Given the importance of labour market policies highlighted in the note, it is likely that countries with already well-developed labour market support schemes are able to provide a quick response with less distortive effects.

Conditionality. Certain countries condition loan forbearance and wage subsidies on the actual reduction in payrolls, with the requirement that support is used to cover fixed costs only or to rehire fired employees after the crisis. The design of transfers and subsidised loans to corporations should ensure that firms preserve jobs when possible and do not divert resources toward exclusively private interests (e.g., to boost CEO compensation or dividend payments).

Short-term versus medium-term policy answers. In many cases, given the need for an urgent policy response during the so-called “phase one” of the crisis, policy has not been particularly targeted in the short term. Going forward, short-term, general policies might need to be refined and better targeted to ensure that public support does not contribute to resource misallocation, for instance by propping up unviable firms. Moreover, policies will also need to be refined to deal with the heterogeneous impact of the shock as firms will not be in the same position to face the crisis for reasons other than liquidity when the activity will slightly recover in the medium term.

New normal. The extent to which the COVID-19 crisis will disrupt economies is still uncertain. As the demand for some sectors might decline for a long period, policy design should find a balance between preserving pre-crisis job matches and allowing new matches via job reallocation. Similarly, deferring tax and debt payments will lead to a surge of corporate debt from an already record high level. Therefore, finding a balance between debt forbearance and bankruptcy procedures will be a critical challenge during the recovery.

References

De Vito, A. and J.P. Gomez, (2020), “Estimating the COVID-19 Cash Crunch: Global Evidence and Policy”, Journal of Accounting and Public Policy, forthcoming.

OECD (2020a), “Evaluating the Initial Impact of COVID-19 Containment Measures on Economic Activity”, Tackling Coronavirus Series, OECD Publishing, Paris.

OECD (2020b), “Initial Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on the Non-Financial Corporate Sector and Corporate Finance”, forthcoming.

OECD (2020c), “Global Financial Markets Policy Responses to COVID-19”, Tackling Coronavirus Series, OECD Publishing, Paris.

OECD (2020d), “SME Policy Responses”, Tackling Coronavirus Series, OECD Publishing, Paris.

OECD (2020e), “Italian Regional SME Policy Responses”, Tackling Coronavirus Series, OECD Publishing, Paris.

Schivardi, F. and G. Romano (2020), “A Simple Method to Compute Liquidity Shortfalls During the COVID-19 Crisis with an Application to Italy”, mimeo.

Notes

← 1. More specifically, it covers all economic sectors except the followings (Nace Rev.2 classification): agriculture (VA), mining (VB), financial (VK), public administration (VO), education (VP), human health (VQ) and activities of households and organizations (VT and VU).

← 2. A more detailed version of this note is available in the OECD-COVID hub.

← 3. The methodology is similar to the one used by Schivardi and Romano (2020) for the case of Italy, and is based on a number of assumptions detailed in the remainder of the note. It is also close in spirit to De Vito and Gomez (2020).

← 4. The assumptions on the decline in revenues in the hardest hit sectors are based on qualitative information from the OECD Policy Tracker.

← 5. The Annex reports this additional set of results: assuming a decline in output of 30% (rather than 15%) in the other manufacturing and non-financial sectors (Figure 2.A.1, Panel A); and for five countries among those with the best coverage in Orbis® (France, Italy, Portugal, Spain and Sweden) (Figure 2.A.1, Panel B).

← 6. Collateral is proxied by the difference between fixed assets and non-current liabilities.

← 7. According to the OECD COVID-19 policy tracker the amount of labour subsidy varies across countries between 60% to 100% with gross wage, with a great majority of countries providing a support ranging from 70% to 90%. This is the case for instance in Canada, Denmark, France, the Netherlands, Norway, Sweden and Japan.

← 8. Indeed, in some countries the support is targeted only to firms experiencing a sizeable shock in their activity. The elasticity implies that the support is ranging from 40% to 80% depending on the size of the sectoral shock.