23. Russian Federation

Support to agriculture

Around 78% of total support to agriculture (TSE) in 2017-19 was provided to producers individually, with the rest directed to general services for agriculture (20%) and to support agricultural commodity buyers (2%).

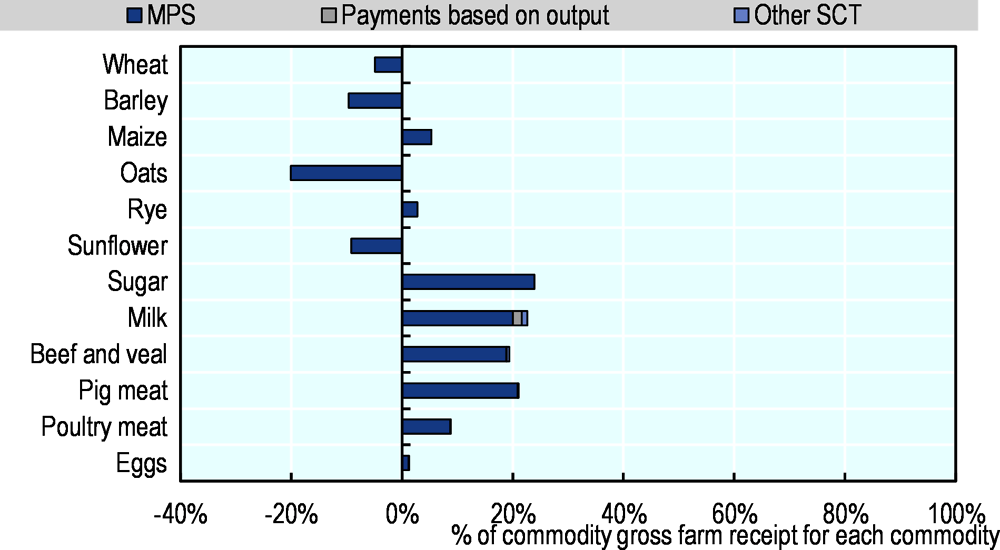

Support to producers fluctuated significantly over the long-term, but has stabilised somewhat since 2014 with levels between 9% and 13% of gross farm receipts (%PSE). The largest part of transfers to producers (73%) originates from the most distorting forms of support, such as subsidies based on output and variable input use and market price support. The aggregate market price support disguises strong variations in support across commodities: it represents a mix between the border protection for imported livestock products and sugar, and the implicit and explicit taxation of exported grains and oilseeds. Livestock producers additionally benefit from domestic grain prices being below the world levels. Within support to general services, the agricultural knowledge system, development and maintenance of infrastructure, and the inspection and control system absorb the largest shares of public funding.

Total support to agriculture (TSE) was equal to 0.7% of GDP in 2017-19. This percentage has been decreasing since the mid-1990s, largely reflecting GDP growth and the declining GDP share of the agricultural sector. Taxpayers provide 54% of total support transfers, the remaining 46% coming from consumers. Agricultural prices are supported at an average of 7% above the international levels (NPR).

Main policy changes

The State Programme for the Development of Agriculture is in its second phase of implementation from 2018 to 2025. Digital agriculture and agricultural export have been incorporated as separate projects of the Programme. The agricultural export component focusses on the development of export infrastructure, facilitation of access to foreign markets through phytosanitary improvements, and product promotion and positioning abroad. Greater emphasis is also given to family farming and rural co-operation. A change in the mechanism for providing direct product subsidies was announced for 2020, aiming to accelerate output growth. A self-standing State Programme on Integrated Development of Rural Territories was launched in early 2020 to boost investments in development of human resource capacity, rural infrastructure, and services in rural areas. The country became a fully-fledged participant of the Paris Agreement on Climate in 2019. The first national law on organic agriculture took effect on 1 January 2020.

In line with its WTO commitments, the Russian Federation has eliminated its tariff rate quota on pig meat. Pig meat imports are now subject to a flat ad valorem rate of 25%, less than half of the over-quota tariff rate previously applied. The ban on agro-food imports from a number of countries imposed in 2014 was extended until end-2020. As a member of the Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU), the Russian Federation was involved in the negotiation process of the Union’s free trade agreements with Singapore and Serbia which were signed in 2019. An interim agreement leading to the formation of a free trade area between the EAEU and Iran entered into force in 2019. Among other components, these agreements include mutual concessions in agro-food trade.

Assessment and recommendations

The State Programme for Development of Agriculture is aimed at boosting the agricultural production and agro-food import substitution. Most recently, the policy orientation was broadened to also include the development of agricultural export potential and accessing the markets of large agro-food importers.

Although there has been some shift towards area and per head payments, the most distorting subsidies and import protection continue to dominate the support provided, in order to achieve the stated objectives of import substitution and export development.

The farm sector’s development could be supported more effectively through a greater focus on investments in the sector’s long-term growth, such as infrastructure, technological innovation, and robust plant and livestock health systems.

Research and development (R&D) and knowledge transfer is one more critical area to improve competitiveness and support long-term growth. This area is key to the most recent export development objective which requires knowledge and skills to seize new demand signals and external market opportunities. Apart from developing new methods and technologies, it is also important to foster their uptake by agricultural producers and agribusiness. This challenge goes beyond agricultural policy and requires improvements in the general environment for investment and doing business.

Human capital is another key factor of long-term growth. Consecutive targeted programmes have directed resources for rural development. A substantial increase of such spending is foreseen within the new State Programme on Integrated Development of Rural Territories. This is a positive development, as much remains to be done to improve living conditions in rural areas and to secure skills and knowledge for rural economy.

The agricultural sector could become one of the main beneficiaries of the State Programme for the Preservation of the Environment, through its effects of improved waste management, reduced water and air pollution, forest rehabilitation, and support for the best available technologies. The agricultural sector should use these opportunities to seize the potentially considerable demand for environmentally friendly products domestically and abroad.

The success of the R&D, rural development, and environmental programmes will depend, among other things, on the consistency of actual funding with the initial financial targets. As these programmes significantly rely on sources other than the state budget, it is important to ensure that the planned activities and administration costs of these programmes are sufficiently attractive for commercial investors.

The country has recently become a fully-fledged participant of the Paris Agreement on Climate and at present has not yet communicated its Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs). A draft law on the regulation of greenhouse emissions has been prepared and is currently under a regulatory impact assessment. It outlines general regulatory principles and instruments but sets neither specific economy-wide or sectoral reduction targets, nor specific policy measures to achieve them.

Policy responses in relation to the COVID-19 outbreak

On 17 March 2020, the government announced a plan of urgent actions to support economy due to the spread of the new coronavirus (GRF, 2020[1]). This plan includes 54 specific actions grouped under the following issues: (i) ensuring supply of essential goods (food included) and aid to the population; (ii) support to the sectors in risk zone (such as tourism, transportation, catering, hotel, entertainment, and sport business and some other activities); (iii) support to small and medium enterprises (SMEs) and individual entrepreneurs (IEs); and (iv) general systemic measures. In addition to the March plan, a separate assistance package is being prepared for “pivotal” businesses of national importance. Beyond these two packages, a number of additional measures have been also announced. The initiatives of particular relevance to the agriculture and food situation are presented below.

Agricultural policies

Imports of food products and other necessities are granted a customs regime of a “green corridor”. Import duties on vegetables, rye, rice, buckwheat, juices, baby food, and raw materials for baby food are lifted until 30 June 2020 (EEC, 2020[2]). Until the same date, a temporary ban is effective on the exports outside the EAEU area for onions, garlic, certain grains (rye, buckwheat, rice, and others), groats and whole meal flour (TASS, 2020[3]).

The Russian Federation has also introduced a quota for wheat, barley and maize exported outside the EAEC, effective for the period between 1 April and 30 June 2020 and amounting to 7 million tonnes in total (International Trade Centre, 2020[4]).

The majority of agricultural producers have the legal status of SMEs and IEs and are thus eligible for the assistance foreseen for such businesses in the government’s March plan. Fiscal aid is one area and includes: a moratorium on the collection of debt and penalties and a moratorium on bankruptcies; reduction of social security contributions from 30% to 15% on wages above minimal wage level and a six-months deferral of social contribution payments for micro-enterprises; deferral of rent payments for the objects rented from state and municipalities; and some other measures. SMEs and IEs can also benefit from a range of credit assistance measures, such as a possibility to make recourse to debt restructuring; deferral on principal debt repayment; access to credit at reduced interest and obtaining a zero-interest credit for wage payments; and other measures. SMEs and IEs will also benefit from a moratorium on all check-ups of businesses (except specific cases) until the end of 2020 and an automatic extension of licenses for six months (GRF, 2020[1]). Most recently, it has been announced that on top of the assistance included in the March plan, SMEs and IEs will receive grants to help them finance wage payments on the condition that they retain 90% of personnel.

As for the forthcoming assistance to large “pivotal” businesses, over one thousand companies of national importance are concerned, of which over a hundred are large agricultural enterprises, food processors and other agribusiness companies (Interfax, 2020). According to preliminary information, the measures for agricultural enterprises may include additional preferential credit and assistance for purchase of variable inputs (360tv.ru, 2020[5]).

Agro-food supply chain policies

The list of “pivotal” businesses also incorporates the leading fertiliser producers, such as Minudobrenia, Phosagro, Uralchem, Uralkali, as well as food wholesalers, retailers and caterers, such as Atak, Auchan, Billa, Vkus Vill, O’Key, Dixi Group, Lenta, and McDonalds. At the moment of writing, details on aid to these companies have not been announced, but it reportedly may also include credit assistance.

Consumer policies

The availability of food and other essential goods is made subject to operational monitoring at federal and regional levels, and a zero-interest credit for the formation of extra reserve stocks may be provided. Food retailers and wholesalers can benefit from subsidised loans to form stocks of goods. The transportation of food and other essential goods is freed from the restrictions on circulation of cargo transport within urban areas and weight control (GRF, 2020[1]). Administrative measures and anti-monopoly procedures can be used across the regions in the case of speculative food price rises.

The Agriculture Ministry announced on 31 March that it will sell 1 million tonnes of grain from its state stockpile on the domestic market to ensure supplies and keep prices down amid the coronavirus pandemic (Reuters, 2020[6]).

A range of additional social payments were introduced for people in need, families with a large number of children and unemployed, helping to support consumption of these groups (MTSP, 2020[7]).

Other

Beyond the federal measures described above, regions can introduce their own measures complementing federal assistance. The government is to provide approximately RUB 200 billion (USD 2.5 billion) of federal subventions to the regions to help implement their measures.

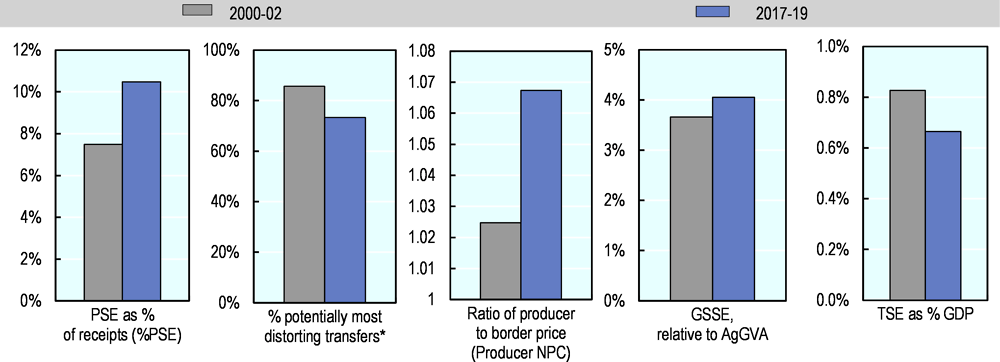

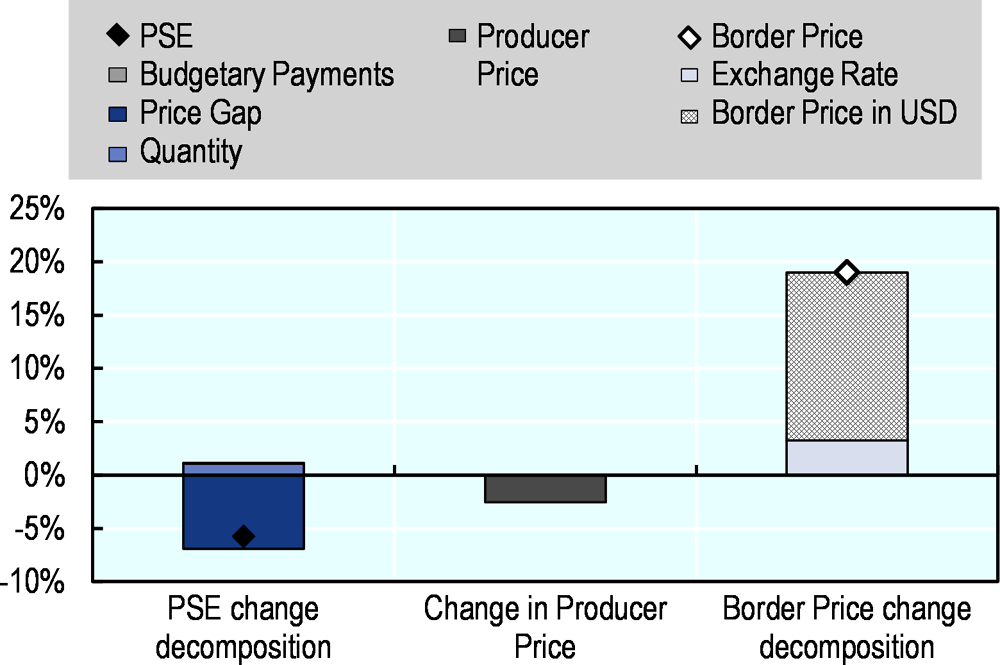

Support to producers (%PSE) was at 10% of producer gross receipts in 2017-19, below the OECD average but above the level observed in 2000-02 (7%). This total masks negative MPS measured for some commodities, equal to 1.6% of producer gross receipts in 2017-19. The share of gross producer transfers (whether positive or negative) provided in most potentially distorting forms declined from 86% in 2000-02 to 73% in 2017-19 (Figure 23.1). The total value of producer support in local currency fell by 6% in the most recent year, largely due to a decrease in the market price support as border prices rose on average, while domestic prices decreased (Figure 23.2). Prices received by farmers were on average 7% above those observed on world markets in 2017-19 (NPC), compared to 2% in 2000-02. This aggregate NPC disguises border protection for livestock products and sugar and taxation of grains and oilseeds. Products receiving the highest commodity-specific support relative to the value of gross farm receipts from those commodities (%SCT) are sugar (24%), milk (23%), pig meat (21%), and beef and veal (19%) (Figure 23.3). The share of Single Commodity Transfers (SCT) in the PSE was 62% in 2017-19. The expenditures for general services (GSSE) increased relative to the sector’s value added – they were equivalent to 4.1% in 2017-19, compared to 3.7% in 2000-02, which partly reflects the growth of agricultural output value. Total support to agriculture (TSE) as a % of GDP decreased from 0.8% in 2000-02 to 0.7% in 2017-19, mostly being a result of the GDP growth.

Contextual information

The Russian Federation has the largest land area in the world and is abundantly endowed with agricultural land. Natural, economic, and social conditions are highly diverse across the territory. The country is the world’s sixth largest economy in purchasing power parity (PPP) terms. Agriculture contributes 3% of GDP and nearly 6% of employment, with both shares having significantly declined since the mid-1990s. In 2019, the country ranked as the second world’s largest producer of barley, rye, sunflower seeds and sunflower oil and fourth largest producer of wheat; it is also among world’s top ten producers of dairy products, pig meat, and poultry.

The farm structure is dualistic, where commercial operations of different sizes co-exist with household units. Commercial units generate nearly 70% of agricultural output and produce virtually all grain, oilseeds, and sugar beet, 82% of animals for slaughter, and 61% of milk. Households engage in agriculture mainly for own consumption and generate less than one-third of total output value. They grow two-thirds of potatoes and 52% of vegetables produced in the country. The rural population is 37.3 million (1 January 2019), or 25% of the total. Households allocated on average 35% of their final consumption expenditures to food (2018), this share ranging from 50% for the poorest to 26% for the richest 20% of the population.

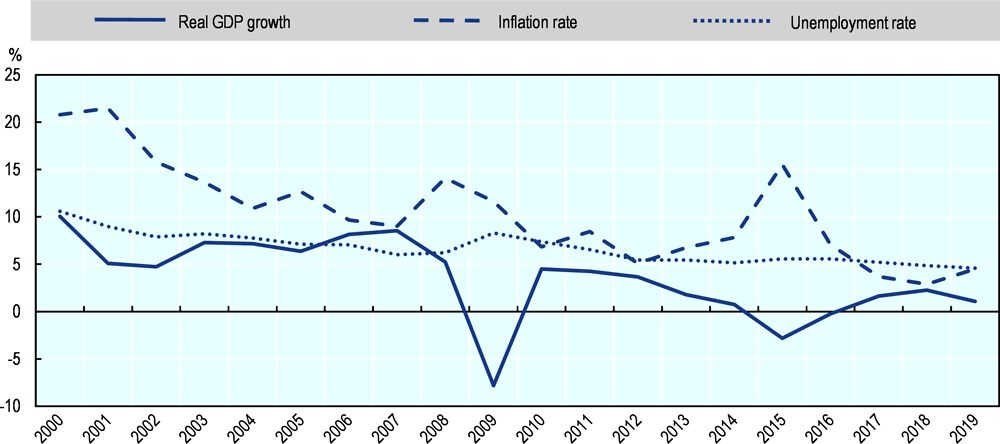

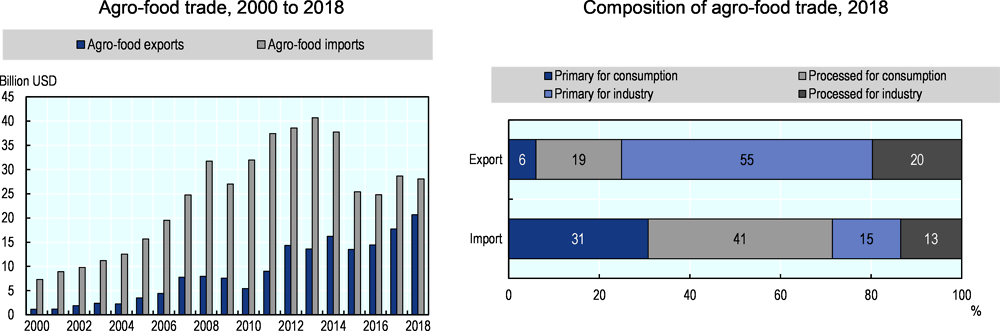

GDP continued to grow in 2019, after picking up in 2017 from the recession of the previous two years. Inflation accelerated, while the unemployment rate continued to decrease. According to preliminary estimates, agricultural output increased by 4% in 2019 compared to a 0.2% fall in 2018. In 2019, the Russian Federation was the largest exporter of wheat and barley, the fourth largest exporter of sunflower seeds and the fifth largest exporter of sunflower oil. The country is among the top five beef importers. Agro-food products account for a significant but declining share of total imports and for a smaller, but rising share in total exports. The negative agro-food trade balance has narrowed significantly since the beginning of the 2010s. The agro-food imports are focused on supplying domestic food consumption in primary and processed products, while exports are largely destined to agro-processors abroad.

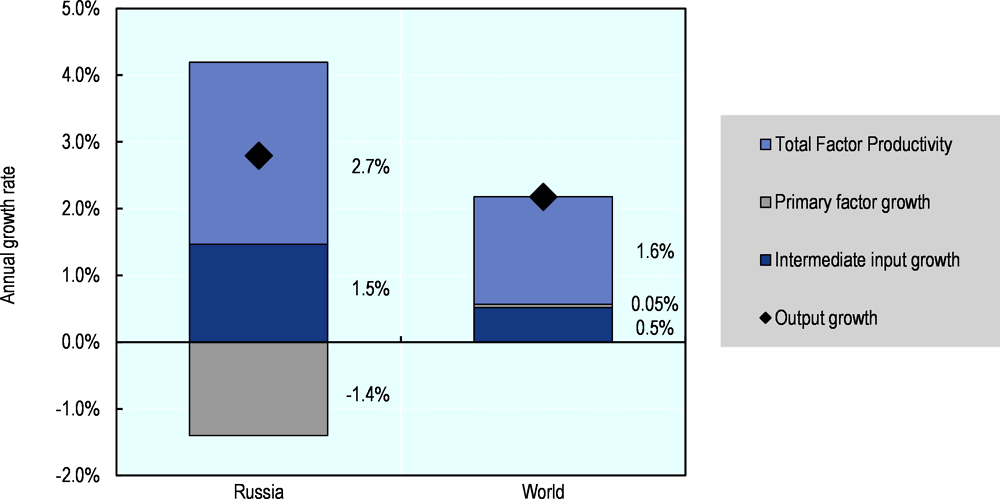

Agricultural output has been recovering from a deep recession in the 1990s. Output growth since 2006 has been driven mainly by the improvements in Total Factor Productivity (TFP), exceeding average global TFP growth. The higher use of intermediate inputs contributed to growth to a lesser degree, while the employment of primary factors, in particular of machinery and labour, has declined. The share of agriculture in total energy use decreased since the 2000s and was less than the OECD average in 2018, despite a greater importance of the sector in the economy than in OECD countries. Agriculture’s contribution to greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions has also declined and remains below the OECD level. Compared to the OECD area, agriculture accounts for a relatively small share of total water abstractions. Aggregate indicators suggest that water stress is much less of a problem than in many OECD countries. However, preliminary estimates point to the existence of a negative phosphorous balance on average in 2007-16.

Description of policy developments

Main policy instruments

The Russian Federation applies a range of price policy instruments. The main one is border protection, including Tariff Rate Quotas (TRQs) and non-tariff measures. Since the accession to the World Trade Organisation (WTO) in July 2012, the Russian Federation’s applied Most Favoured Nation (MFN) agricultural tariff has been reduced to 11.2% by 2018, or has been aligned with the average final bound agricultural tariff.1 In 2018, the applied agricultural tariff was nearly twice the non-agricultural tariff (6.1%). Animal and dairy products, beverages and tobacco, sugar and confectionary face the highest average import duties within the agricultural group (WTO/ITC/UNCTAD, 2019[8]). Border measures are in large part implemented within the framework of the Customs Union of the Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU). Domestic price regulation measures are also applied, such as grain interventions. The government can purchase or sell grain if the market prices move above or below the established price band. Prices at which market interventions are carried out, however, do not play the role of price guarantees. Restrictions on imports or exports can be imposed during the intervention periods.

Payments based on output for marketed livestock products are provided from regional budgets and there is also a national payment for milk, which is co-financed by the federal and regional governments. Concessional credit is one of the most important support instruments, with concessions taking the form of reduced interest rates fixed by the government, combined with a financial compensation to lending banks. For credit taken before 2017, concessions are also granted in the form of interest subsidies to borrowers. In addition, a range of subsidies for variable inputs are in place. Support is also provided through investment co-financing and leasing of machinery, equipment and pedigree livestock at preferential terms. Area payments for crop production began in 2013, replacing several previous nationwide input subsidies provided for sowing and harvesting campaigns. Agricultural producers also benefit from a number of tax preferences and from concessions on repayment of historical arrears on federal taxes and social contributions.

Most of the support measures described above are implemented within a multi-year State Programme for the Development of Agriculture (hereafter, State Programme) – the country’s main agricultural policy framework. It is based on the principle that support measures be co-financed by federal and regional governments, with co-financing rates varying across the regions and individual measures. In addition to support included in the State Programme, regions implement and finance their own, strictly regional support measures.

The current State Programme has been undergoing amendments since its launch in 2013 in response to the significant changes in overall economic conditions. Its sub-programmes were reconfigured in 2015 and 2017. The Programme’s initial budget targets were also adjusted in terms of the overall amounts of spending and shifts of funds within and between programme components. In 2018 and 2019, the State Programme underwent further changes in its structure, spending levels, administration, and implementation period (Mau et al., 2020[9]).

Some recently introduced State Programmes in other economic and social areas, such as rural development and environment, contribute to shaping the conditions for long-term development of agriculture.

Domestic policy developments in 2019-20

In 2019, the implementation period of the on-going State Programme was extended from 2020 to 2025. Food security based on import substitution remains the principal agricultural policy objective. However, export development and income growth of rural households are emphasised as additional objectives. The following growth targets in nominal terms are to be met by 2025 relative to 2017, the year ending the first phase of the State Programme: increase in agricultural production by 16.3%; increase in agricultural value added by RUB 2 079.6 billion (USD 32 billion)2 to reach a total of RUB 5 774 billion (USD 89 billion); more than a doubling of exports; and increase of fixed capital investments in agriculture by 21.8% (GRF, 2019[10]).

The structure of the State Programme was again modified in 2019 and at present incorporates six projects and four programmes. Projects have a fixed timeframe, while programmes represent continuous processes. The State Programme’s projects are: 1) development of the sub-sectors which ensure accelerated import substitution; 2) stimulation of investment activity; 3) technical modernisation; 4) export of products of the agro-industrial complex; 5) support systems for family farming and development of rural co-operation; and 6) digital agriculture. The four programmes are: a) development of land reclamation complex; b) ensuring general conditions of the functioning of the agro-industrial complex (covering market interventions, assistance related to abnormal climate and animal disease events and some other measures); c) scientific and technological support for the development of the agro-industrial complex; and d) veterinary and phytosanitary surveillance. Digital agriculture and agricultural export are new components of the State Programme, introduced, respectively, in 2018 and 2019. The project on digital agriculture aims at supporting the sector’s development through the introduction of digital technologies and platform solutions, including the creation, in 2020, of a Single Window sub-platform for collecting industry data from the national Digital Agriculture platform. Details on the agricultural export project are presented below in the section on trade policy.

The current version of the State Programme also emphasises family farming more explicitly. Thus, being previously scattered across other parts of the State Programme, measures related to support to family farms and rural co-operatives are now presented as one stand-alone project (project 5 above). Starting from 2020, the activity on rural development has been excluded from this State Programme and will be implemented as a separate, self-standing State Programme on integrated rural development (discussed below).

Apart from these new features, the current State Programme maintains the previous directions of support and the underlying measures. However, the project-and-programme approach is intended to improve the Programme’s administration and efficiency of spending. Of the aggregate funding during the whole implementation period, around 40% are to be budgetary sources (federal and regional) and the remaining 60% are to be mobilised from extra-budgetary sources, which include profits from commercial activities of public institutions, investments from private businesses, non-governmental organisations, and other sources (GRF, 2019[10]).

According to preliminary information, the federal budget allocated RUB 311 billion (USD 4.8 billion) to the State Programme in 2019, which is 6% more than last year (MoA, 2019[11]; State Treasury, 2020[12]). Around 35% of this expenditure was directed to stimulation of investment activities (project 2 above) consisting of interest subsidies on bank loans and the co-financing of investment projects, and nearly 20% was spent on the development of the import-substituting subsectors (project 1 above) covering key production subsidies (State Treasury, 2020[12]). This federal spending was topped up by contributions from the regions across the components of the State Programme. In addition, regions provided strictly regional support beyond the State Programme.

The federal funding for the State Programme for 2020 is planned at nearly RUB 284 billion (USD 4.4 billion), which is below the corresponding budget target set for 2019 at the beginning of that year (FL, 2018[13]; FL, 2019[14]). The projects on stimulation of investment activities and development of import-substituting subsectors are to absorb around two-thirds of total federal funding for the State Programme in 2020.

Grain market interventions were not particularly active during the monitoring period. The government announced market price maximums for grains for the 2018/19 and 2019/20 seasons which, if prices rise, would trigger public grain sales. However, due to abundant supplies, relatively small sales from intervention stocks were made during the 2018/2019 season, while no grain purchases have been carried out since the 2016/17 season due to high public stocks. In the first half of 2018, the grain industry benefitted from reduced transportation tariffs on domestic grain shipments from several distant regions in Siberia to other country regions. This preference was renewed for the period between 9 April and 31 July 2019. This measure adds to the temporary waiver of wheat export duty in effect since September 2016 (see trade policy developments). In August 2019, the government approved a “Long-term Strategy for Development of the Grain Sector up to 2035” (GRF, 2019[15]). Among others, it states the goal to develop a technologically advanced, competitive, innovative and investor-attractive grain industry. The key activities to achieve this goal are improvements in crop selection and seed production, technologies and machinery, quality testing, phytosanitary work, and infrastructure and logistics. Grain export enhancement is an important focus of the strategy, which, among other activities, foresees substantial private investments in export infrastructure.

Interest subsidies on short-term loans and investment credit, investment grants, leasing of machinery, equipment and livestock at preferential terms, and production subsidies in the form of the area payment and unified payment continued to constitute the bulk of producer support. The unified payment was introduced in 2017, integrating 27 previous individual subsidies across different components of the State Programme. This includes several subsidies for crop and livestock production, subsidies for insurance and interest on short-term credit, support of small-scale farmers, and the assistance provided within the previous component on “economically important regional programmes”. The purpose of the unified payment had been to simplify the budgeting and transfer of funds from the federal centre to regions. Regions top-up this payment and continue to allocate it across individual supports included in the unified payment, with producers, as previously, receiving the assistance in the form of individual supports. Every year regions can select specific types of individual supports within the unified payment depending on regional priorities.

Some changes in the implementation of the unified payment and the area payment for crops were introduced reflecting the efforts to increase agricultural insurance. Insurance covered 5% of total area planted to annual and perennial crops in 2016 and 1.7% in 2018 (MoA, 2019[11]). Starting from 2019, crop and livestock insurance have separate budgetary earmarks within the unified payment and the area payment to ensure potential uptake of this support by the regions.

The Ministry of Agriculture announced further changes in the implementation of the unified payment, area payment, and milk payment. Starting from 2020, the federal contribution previously directed to these subsidies is to be provided in two parts: one part will be used for “compensatory” support and another one for “stimulative” support. At the regional level, both parts will be topped-up from the regional budgets and allocated to specific supports depending on regional priorities. The range of the support elements available for selection by the regions remains the same as before (around 30 specific payments, of which 27 could previously be sourced from the unified payment at the regional level). The funds of the “compensatory” support are to be used to subsidise production at current levels, while the funds for “stimulative” support are to be used to subsidise planned increases in production. The regions select the products whose output they plan to increase and which thus becomes eligible for the “stimulative” part of the federal funding. The Ministry foresees to increase gradually the share of “stimulative” part against that of “compensatory” part of support. The concrete modalities of the new mechanism have not been officially approved at the moment of writing. However, the overall intention of this initiative seems to be an increase of the output-boosting effect of production subsidies.

The launch in 2020 of the State Programme on “Integrated Development of Rural Territories” for the period of 2020-25 was an important development (GRF, 2019[16]; Serova et al., 2020[17]). It foresees a considerable increase of investments in rural development. The federal budget plan earmarked RUB 36 billion (USD 555 million) for 2020 for this Programme, which is three-fold the average level of annual investments in rural development in 2016-19. In addition to federal investments, the Programme foresees to attract funds from the regional budgets and extra-budgetary sources. Investments are to be focussed on housing, development of human resource capacity, rural infrastructure, and improved provision of services in rural areas. The Ministry of Agriculture is the main implementing body. Ministries responsible for economic development, construction, road building, transport, education, environment, health, sports, culture, communications, and development of specific regions also participate in the implementation of this Programme.

In the context of climate change and sustainability, the following policy frameworks and developments are of importance. On 6 October 2019, the Russian Federation became a fully-fledged participant of the Paris Agreement on Climate by ratifying the Agreement, which it signed in April 2016 (GRF, 2019[18]). In 2014, the government approved an action plan for the reduction of greenhouse emissions. It focuses on the development of a regulatory and operational framework to achieve this goal, such as the systems for registration, evaluation and projection of emissions, as well as state regulation of emissions. As part of this plan, a draft law on the regulation of greenhouse emissions was prepared in 2018 and is currently under a regulatory impact assessment (GRF, 2018[19]). This document formulates general definitions, principles and instruments of state regulation of emissions, but at this stage does not contain any specific general or sectorial reduction targets. The other main national policy documents related to climate change are the “Climate Doctrine of the Russian Federation” (PRF, 2009[20]), and the “Comprehensive Plan for the Implementation of the Climate Doctrine of the Russian Federation for the period until 2020” (GRF, 2011[21]). The Climate Doctrine sets out a conceptual framework for the national activities on climate change, while the Comprehensive Plan formulates a unified state policy in that area. The latter spells out key actions assigned to the ministries and public agencies. In accordance with the Climate Doctrine and the Comprehensive Plan, the Ministry of Agriculture is tasked to promote climate adaptation practices such as adaptive landscape farming systems, sustainable water, air, and nutritional regimes, encourage the introduction of new agricultural crop varieties, and the optimisation of crop conditions based on long-term forecasts. Another policy document, the State Programme for the Development of Agriculture, as the main sectoral policy framework, has among its objectives the creation of favorable conditions for the efficient use of land; it also foresees investments in land reclamation and support of innovations for resource saving and energy efficiency. Beyond the long-term activities included in the framework policy documents mentioned above, policy measures have been emerging in the context of recurrent climatic disasters of the past years. Thus, attention has been given to creating a more formal regulatory basis for coping with the consequences of abnormal natural events. This includes the establishment of formal procedures for state support in respect of catastrophic weather events, such as the budgeting of the financial assistance through different administrative levels, and the assessment of damage and restoration costs (GRF, 2014[22]; MoA, 2015[23]).

The country’s first law on organic products took effect on 1 January 2020 (FL, 2018[24]). It regulates production, storage, transportation, labelling, and marketing of organic products. The law formulates the basic terms, such as “organic products”, “organic agriculture”, “producers of organic products”; it introduces a graphical label for organic products; it defines the basic requirements for the production of organic products; it stipulates the maintenance of a unified state register of developers of organic products; and it provides for a voluntary confirmation of the conformity of the production of organic products by certification bodies accredited in the national accreditation system. This law, however, states that voluntary confirmation of conformity does not replace the obligatory confirmation of conformity of organic products in the cases when this is required by the legislation of the Eurasian Economic Union and the Russian Federation.3 The country’s organic food industry is in the early stages of development, so the government expects this new law to provide impetus to the evolution of this sector. According to the Ministry of Agriculture, about 100 certified producers of organic products operate in the country, and the value of the organic product market is estimated at more than EUR 180 million, or 0.2% of the world organic production (MoA, 2019[25]). Some estimates also indicate that imported organic products currently account for up to 80% of the Russian Federation’s organic food market (USDA, 2019[26]).

The government sees a considerable growth potential for the demand for environmentally clean products in the Russian Federation both on domestic and foreign markets. The federal Ministry of Agriculture has prepared a draft law on agricultural products, raw materials and food with improved ecological characteristics which at the moment of writing has gone through public discussion, but has not yet been submitted to parliament. Currently, work is underway to create an appropriate regulatory framework, including a set of national standards (MoA, 2019[25]).

In November 2018, the amendments on bioethanol for fuel use were introduced to the 1995 Federal Law which regulates production and turnover of ethyl alcohol, alcoholic and alcohol-containing products (FL, 2018[27]).4 The changes include a new clause containing the definition of bioethanol, exclusion of bioethanol from excise taxation and from the minimum price regulation for ethyl alcohol. Other amendments relate to the licensing of production, storage and supply of bioethanol, requirements for the equipment used for bioethanol production, and other issues. The amended Law also stipulates a ban on the production of bioethanol from food raw materials to exclude the possibility of using it as a surrogate of alcoholic beverages.

The State Programme “Preservation of the Environment” was launched as a cross-sectoral framework in October 2018, with the implementation horizon currently set at up to 2024. Through this Programme, the Russian Federation intends to make its major contribution to the Paris Agreement and achieve other national goals of sustainable development. The Programme integrates specific components on areas of prime environmental importance, such as industrial and urban waste management; clean air; clean water; rehabilitation and preservation of unique water sources, including the Volga river and lake Baikal and others; preservation of biodiversity; preservation of forests; and adoption of the best available technologies with the focus on “green” technologies. Although none of these components specifically target agriculture, this sector can potentially be among the main beneficiaries of this State Programme through the effects of better waste management, reduced water and air pollution, forest rehabilitation, as well as the availability of support for the adoption of green technologies.

Trade policy developments in 2019-20

The Russian Federation, together with Belarus, Kazakhstan, Armenia and Kyrgyzstan, is a member of the Treaty on the Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU). Meat imports from the non-CIS area into the EAEU area are subject to tariff rate quotas (TRQs) which are allocated to each EAEU member. Until 2020, the Russian Federation had applied import quotas for beef, pig meat and pig trimmings, and poultry meat. In accordance with the country’s WTO commitments, tariff quotas for pig meat and pig trimmings have been eliminated as of 1 January 2020, with a flat 25% import tariff applied to all imports of the items concerned. The quota volumes and import tariffs for beef and poultry meat remain unchanged, as foreseen by the country’s WTO commitments.

The Russian Federation also participates in the EAEU’s TRQ for rice imported from Viet Nam. A quota of 10 000 tonnes was opened in 2017 according to the Free Trade Agreement between the EAEU and Viet Nam. Before 2019, it had been allocated to Belarus and the Russian Federation. In 2019, the share of the Russian Federation was reduced to 8 776 tonnes from 9 039 tonnes in the previous year, as Armenia also joined the TRQ (150 tonnes), while the share of Belarus was increased from 961 tonnes to 1 074 tonnes.

In June 2019, the ban on agro-food imports from the European Union, the United States, Canada, Australia, Norway, Ukraine and several other countries was extended until 31 December 2020 with no changes in the list of products covered. This list includes live swine (except pure-bred animals for breeding), meat and certain meat by-products, milk products, fruits and vegetables, prepared foods, fish, and salt. The ban was initially introduced on 7 August 2014 for a period of one year after the imposition of sectoral sanctions on the Russian Federation in the context of developments related to Ukraine. Sanctions and counter-sanctions have since then been extended several times.

On the export policy side, export development is a growing policy priority. Beyond the longer-term growth in grain and oilseed exports, this re-orientation is also due to more recent increases in the production of other agricultural products, notably swine and poultry meat.

The Project “Export of Products of the Agro-Industrial Complex” has recently been included in the State Programme. It seeks to increase agro-food exports to USD 45 billion per year by the end of 2024, and formulates the following objectives: generation of additional volumes of exportable goods, development of export infrastructure, facilitation of access to foreign markets in the sanitary and phytosanitary area, and creation of an effective system of product positioning abroad.

The People’s Republic of China, India and Southeast Asia are regarded as key markets for export development. In late 2018, the Federal Service for Veterinary and Phytosanitary Surveillance of the Russian Federation and Chinese customs authorities signed protocols on mutual supplies of poultry meat and milk products. As of early 2020, China had reportedly allowed poultry imports from 55 Russian companies and dairy imports from the first 10 Russian companies, and an additional list of 23 dairy suppliers was submitted for approval in February 2019 (Vesti Ekonomika, 2020[28]; USDA, 2019[29]). In 2019, the Russian Federation agreed veterinary certificates for exports of dairy products to Turkey and exports of processed pig meat products to Singapore. In October 2019, the Minister of Agriculture of the Russian Federation and his homologue from the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia signed a memorandum on mutual increase of agricultural exports. The Russian Federation expects to increase exports of all key agricultural products, such as grains, meats, feedstuffs and processed food.

Grain export remains a highly important area of export development. The Ministry of Agriculture of the Russian Federation announced plans to construct new grain transit points and grain terminals in the country’s areas with the main exportable surplus production, including the Far East. As in the case of meat and dairy, China is also considered as a destination with high potential to further boost grain exports. Since mid-2010, Russian phytosanitary authorities have worked on phytosanitary aspects of exports to China and signed respective protocols on wheat, maize, rice, soybeans and rapeseeds. In February 2018, China allowed wheat imports from six Siberian and Far East regions in the Russian Federation. Further protocols on increasing exports to China were signed during the St. Petersburg International Economic Forum in June 2019. Thus, one additional large Siberian region was approved for wheat imports to China, and imports of soybeans from all Russian regions were allowed (previously, they were possible only from specified regions of the country). Protocols were also signed on the expansion of the list of allowed exports to China to include other grain and oilseed products, such as barley, and meals of oilseed and sugar beet (Agroinvestor, 2019[30]).

In 2019, the temporary reduction to zero of the wheat export duty, originally introduced in September 2016, was extended until 1 July 2021. The zero export duty applies to all wheat except durum wheat and planting seeds of other types of wheat.

On 1 October 2019, the Russian Federation, as an EAEU member, signed the Framework Agreement on Comprehensive Economic Cooperation and the Free Trade Agreement between the EAEU and the Republic of Singapore (EAEU, 2019[31]; EAEU, 2019[32]). Even though Singapore’s import regime grants free entry to imports from all origins, the EAEU Commission considers the fixation of the duty-free regime between the parties in a formal trade agreement as an important step in view of possible changes in Singapore’s import tariff regime: Singapore’s WTO commitments give it the possibility to implement import duties on agricultural goods of up to 10%. Regarding the imports of agricultural goods from Singapore into the EAEU area, some key product groups, including meat, dairy and some others, are excluded from any tariff commitments. Other agricultural goods are to benefit from duty free entry immediately after the agreement takes effect, or to be subject to different schedules of duty reductions within a transition period of ten years.

On 25 October 2019, the Russian Federation, as an EAEU member, also signed a Free Trade Agreement with the Republic of Serbia. The agreement provides for certain exemptions from an otherwise free trade regime. Within the agricultural group, sugar and certain alcoholic beverages imported into Serbia from the EAEU area remain subject to MFN import duties, while tariff rate quotas are established for specific processed cheese, spirits from grape wine, and cigarettes. Serbian poultry meat, specified processed cheese, sparkling wine, ethyl alcohol and tobacco products entering the EAEU continue to pay EAEU common tariffs, whereas tariff rate quotas are be applied to specified cheeses, alcohol, and cigarettes containing tobacco (EAEU, 2019[33]).

An interim agreement leading to the formation of a Free Trade Area between the EAEU and its member states and the Islamic Republic of Iran entered into force on 27 October 2019. In its agriculture chapter this agreement foresees a reduction of between 25% and 100% of EAEU import duties on a broad range of products imported from Iran, notably certain fish products, vegetables, and fresh and dried fruits. The EAEU benefits from 20% to 75% tariff reductions on products such as beef and veal, butter, certain confectionery and chocolate, mineral waters, oil and fat products (EAEU, 2018[34]).

The EAEU also actively promotes economic and trade relations with other countries. In 2019, memoranda of co-operation and memoranda of understanding were signed with Indonesia, the African Union, Bangladesh, Argentina, and the Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific (ESCAP). These documents aim at increasing economic co-operation, bilateral trade and investments, and among other issues, cover those related to agriculture.

The Russian Federation, as an EAEU member, continued to participate in the development of the Union’s regulatory base. Developments in the phytosanitary and sanitary area over the monitored period include the amendments to the EAEU unified veterinary requirements for goods subject to veterinary control and surveillance; unified veterinary certificate; amendments to unified quarantine phytosanitary requirements. In the area of technical regulation, amendments to EAEU technical regulations on food safety, and on the labelling of food products were introduced; an EAEU technical regulation on the safety of alcohol products was adopted; and the agreement on the mechanism of traceability of goods within the EAEU was signed. The EAEU also worked on specific issues of customs regulation, among other topics.

References

[5] 360tv.ru (2020), “Agricultural support measures are to be developed in Russia amid the pandemic”, https://360tv.ru/news/dengi/mery-podderzhki-selskogo-hozjajstva-razrabotajut-v-rossii-na-fone-pandemii/ (accessed on 7 April 2020).

[30] Agroinvestor (2019), “China allowed imports of additional types of Russian agricultural products”, https://www.agroinvestor.ru/markets/news/31869-kitay-razreshil-postavki/ (accessed on 6 June 2019).

[31] EAEU (2019), “Framework agreement on comprehensive economic cooperation between the Eurasian Economic Union and its Member States, of the one part, and the Republic of Singapore, of the other part”, http://www.eurasiancommission.org/ru/act/trade/dotp/sogl_torg/Documents/%d0%a1%d0%b8%d0%bd%d0%b3%d0%b0%d0%bf%d1%83%d1%80/EAEU-Singapore%20Framework%20Agreement.pdf.

[33] EAEU (2019), “Free trade agreement between the Eurasian Economic Union and its Member States, of the one part, and the Republic of Serbia, of the other part”, http://www.eurasiancommission.org/ru/act/trade/dotp/sogl_torg/Documents/%d0%a1%d0%b5%d1%80%d0%b1%d0%b8%d1%8f/Agreement.pdf.

[32] EAEU (2019), “Free trade agreement between the Eurasian Economic Union and its Member States, of the one part, and the Republic of Singapore, of the other part, 1 October”, http://www.eurasiancommission.org/ru/act/trade/dotp/sogl_torg/Documents/%d0%a1%d0%b8%d0%bd%d0%b3%d0%b0%d0%bf%d1%83%d1%80/EAEU-Singapore%20FTA_Main%20Agreement.pdf.

[34] EAEU (2018), “Interim Agreement leading to formation of a free trade area between the Eurasian Economic Union and its Member States, of the one part, and the Islamic Republic of Iran, of the other part”, Eurasian Commission, http://www.eurasiancommission.org/en/.

[2] EEC (2020), “Decision of the Eurasian Economic Commission No. 33 of 3 April, 2020”, https://docs.eaeunion.org/docs/ru-ru/01425324/err_08042020_33.

[14] FL (2019), “On federal budget for 2020 and for 2021 and 2022 planning period”, Federal Law of 2 November 2019 No. 380-FZ, https://rg.ru/2019/12/06/byudzhet-dok.html.

[24] FL (2018), “Federal Law of 3 July 2018 No. 280-FZ “On Organic Products and Amendments to Certain Legislative Acts of the Russian Federation””, http://publication.pravo.gov.ru/Document/View/0001201808030066 (in Russian).

[27] FL (2018), “On Amending the Federal Law on State Regulation of the Production and Turnover of Ethyl Alcohol, Alcohol and Alcohol-Containing Products, and on Limiting the Consumption (Drinking) of Alcoholic Products”, Federal Law of 28 November 2018 N 448-FZ.

[13] FL (2018), “On federal budget for 2019 and for 2020 and 2021 planning period”, Federal Law of 29 November 2018 No. 459-FZ, http://publication.pravo.gov.ru/Document/View/0001201811300026.

[1] GRF (2020), “Plan of urgent actions to ensure stable economic development in the situation of the spreading new coronavirus infection”, Government of the Russian Federation, http://static.government.ru/media/files/vBHd4YRxpULCaUNNTFLVpPSZbMCIA2Zq.pdf (accessed on 17 March 2020).

[18] GRF (2019), “On adoption of the Paris Agreement”, Resolution of the Government of the Russian Federation of 21 September 2019 N1228, http://government.ru/docs/37917/.

[15] GRF (2019), “On approval of the long-term strategy for the development of the grain complex up to 2035”, Order of the Government of the Russian Federation of 10 August 2019 N1796-p, http://government.ru/docs/37668/.

[16] GRF (2019), “On approval of the State Programme of the Russian Federation ‘Integrated development of rural areas’ and on the introduction of the amendments in certain acts of the Government of the Russian Federation”, Resolution of the Government of the Russian Federation of 31 May 2019 N696, http://mcx.ru/upload/iblock/f31/f31f147cde547c84d723ab425a340a3c.pdf.

[10] GRF (2019), “On introduction of changes into the Resolution of the Government of the Russian Federation of 14 July 2012 N717”, Resolution of the Government of the Russian Federation of 8 February 2019 N98.

[19] GRF (2018), Draft Federal Law «On state regulation of emissions and absorption of greenhouse gases and on the amendments to certain legislative acts of the Russian Federation», https://regulation.gov.ru/projects#npa=86521.

[22] GRF (2014), “On approval of the rules for the provision of other inter-budgetary transfers from the federal budget to the budgets of the subjects of the Russian Federation to compensate agricultural producers for damage caused by natural emergencies”, Resolution of the Government of the Russian Federation of 22 December, 2014 No. 1441 (as amended on 14 November, 2018, No. 1371), http://publication.pravo.gov.ru/Document/View/0001201412250009 ; http://publication.pravo.gov.ru/Document/View/0001201811230006?index=1&rangeSize=1.

[21] GRF (2011), “On approval of the Comprehensive Plan for the Implementation of the Climate Doctrine of the Russian Federation for the period until 2020”, Order of the Government of the Russian Federation No. 730-р dated April 25, https://rg.ru/2011/05/03/klimat-doktrina-site-dok.html.

[4] International Trade Centre (2020), Market Access Map – COVID-19 Temporary Trade Measures, https://www.macmap.org/covid19.

[9] Mau, V. et al. (2020), “Agrofood sector in 2019”, Russian Economy: Trends and Outlooks, Gaidar Institute for Economic Policy, Higher School of Economics, RANEPA, Moscow.

[11] MoA (2019), “2018 National report on the implementation and results of the State Programme for Development of Agriculture and Regulation of Agricultural Product, Raw Materials and Food Markets in 2013-2020”, http://mcx.ru/upload/iblock/61d/61d430039b8863186a4fbb1f60fab1c6.pdf.

[25] MoA (2019), “Background information on the implementation of measures aimed at adapting to climate change in agriculture, introduction of the Green Growth Strategy in the context of Bio-economy and Circular Economy issues”, Note submitted to the OECD Secretariat, 30 December 2019.

[23] MoA (2015), “On approval of the procedure for assessing damage to agricultural producers from emergencies of natural nature, improving methods of calculation of the costs of eliminating the consequences of natural emergencies”, Order of the Ministry of Agriculture of the Russian Federation of 26 March, 2015, No.113, http://publication.pravo.gov.ru/Document/View/0001201505070042.

[7] MTSP (2020), News on COVID-19., https://rosmintrud.ru/social/236.

[20] PRF (2009), “On Climate Doctrine of the Russian Federation”, Order of the President of the Russian Federation of 17 December 2009, No. 861-рп, http://pravo.gov.ru/proxy/ips/?docbody=&firstDoc=1&lastDoc=1&nd=102134636.

[6] Reuters (2020), Update 1 – Russia to sell half of grain stockpile amid coronavirus, https://www.reuters.com/article/health-coronavirus-russia-grains-stockpi/update-1-russia-to-sell-half-of-grain-stockpile-amid-coronavirus-idUSL8N2BO3PB.

[17] Serova, E. et al. (2020), “On the Situation of Rural Territories in the Russian Federation in 2018”, Annual Monitoring Report, Higher School of Economics, Moscow.

[12] State Treasury (2020), Report on Execution of Federal Budget, 1 January 2020, http://www.roskazna.ru/.

[3] TASS (2020), A ban of the EEC on exports of critically important goods to third countries has taken effect, https://tass.ru/ekonomika/8222325.

[26] USDA (2019), GAIN Report No. RS 1823, 1 March, 2019, https://gain.fas.usda.gov/Recent%20GAIN%20Publications/Russia%20to%20Adopt%20New%20Law%20on%20Organics%20_Moscow%20ATO_Russian%20Federation_3-1-2019.pdf.

[29] USDA (2019), “GAIN Report No. RS 1903, 28 February”, https://apps.fas.usda.gov/newgainapi/api/report/downloadreportbyfilename?filename=Russia%20Sets%20Ambitious%20Dairy%20Exports%20Goal%20for%202025_Moscow_Russian%20Federation_2-28-2019.pdf.

[28] Vesti Ekonomika (2020), “China will increase food purchases from Russia, 10 January”, https://www.vestifinance.ru/articles/131068?utm_referrer=https%3A%2F%2Fzen.yandex.com&dbr=1.

[8] WTO/ITC/UNCTAD (2019), World Tariff Profiles, http://stat.wto.org/TariffProfile/WSDBTariffPFHome.aspx?Language=E.

Notes

← 1. Agricultural tariff corresponds to the WTO definition and covers the HS-codes as specified in Annex 1 of WTO Agreement on Agriculture.

← 2. All values in roubles for 2019 are converted into US dollars using average official exchange rates of the Central Bank of Russia for 2019. All values in roubles for 2020 are converted into US dollars using the official exchange rate of the Central Bank of Russia on 10 January 2020.

← 3. The term “confirmation of conformity” refers to either a declaration of conformity by manufacturer or certification of conformity by a third party (voluntary or mandated by the legislation).

← 4. This law does not apply to the production and turnover of automobile gasoline blended with ethyl alcohol or alcohol products, which is subject to specific technical regulation of the EAEU.

This document, as well as any data and map included herein, are without prejudice to the status of or sovereignty over any territory, to the delimitation of international frontiers and boundaries and to the name of any territory, city or area. Extracts from publications may be subject to additional disclaimers, which are set out in the complete version of the publication, available at the link provided.

https://doi.org/10.1787/928181a8-en

© OECD 2020

The use of this work, whether digital or print, is governed by the Terms and Conditions to be found at http://www.oecd.org/termsandconditions.