Chapter 5. Strengthening the social protection system

Indonesia has made great strides towards establishing a social protection system, supported by sustained political backing across administrations, the scaling up of key programmes and the emergence of a strong information architecture. This chapter charts the progress that Indonesia has made towards establishing a social protection system and identifies the key levers for strengthening this system in the future. It also recognises the constraints to systematisation and proposes reforms to the institutions, policies and information systems that underpin social protection as a means of enhancing its capacity to address the challenges identified in the report and underpin inclusive economic growth.

The Government of Indonesia (GoI) is fulfilling the commitment to establish a social protection system articulated in the National Medium Term Development Plan (RPJMN) 2015-2019. Important progress has been made in strengthening coherence and co-ordination across a number of dimensions, including legislation, policies and institutions. There has been a strong increase in spending on key programmes, such as Penerima Bantuan Iuran (PBI) and Program Keluarga Harapan (PKH). Nonetheless, further progress is required to realise the RPJMN’s vision of a comprehensive and coherent social protection system covering the entire population as the cornerstone of its inclusive growth strategy.

A minority of the poor population is accessing all the interventions to which they are entitled, and which they need to exit poverty on a permanent basis. Social insurance schemes face important constraints (and difficult financial trade-offs) with respect to increasing coverage. Active labour market policies to increase the skills and productivity of vulnerable workers do not operate at sufficient scale while workers are left vulnerable by low compliance with severance pay and minimum wage legislation, as well as the absence of an unemployment insurance fund.

At the same time, social protection policy makers at a national level must harness the power of sub-national government to address wide variation in local contexts across the country. In addition, ambitions to expand social protection are held in check by a lack of financing. Social protection spending remains very low by regional standards, which is in large part a function of weak domestic resource mobilisation. As a result, it is essential to optimise resources allocated to social protection by creating synergies and enhancing efficiency wherever possible.

This chapter outlines the main dimensions of the social protection system in Indonesia. It then identifies the main challenges to strengthening this system and proposes appropriate policy responses.

The institutional structure for social protection remains fragmented

Indonesia is developing the policy, legislative and information infrastructure for a social protection system. However, the overall system architecture is still characterised by extensive fragmentation and a lack of clear oversight. Efforts to enhance coherence are hampered both by the number of line ministries involved in provision of social protection programmes and by an excess of co-ordinating bodies.

The social protection system is not organised under one central co-ordinating body. The roles and responsibilities of legislative work, co-ordination, supervision, implementation and management are divided across various line ministries and administrative bodies. Furthermore, ministries with little or no experience have direct involvement in poverty-reduction activities.

The Coordinating Ministry of Human and Cultural Development oversees key social policies but it does not guide the direction of social protection specifically. It provides oversight to technical ministries directly involved in the delivery of key social protection programmes such as the Ministry of Social Affairs (MoSA), the Ministry of Health and the Ministry of Education and Culture. It is also responsible for ensuring policy co-ordination and harmonisation of programmes across ministries but not with specific reference to social protection.

The Ministry for Planning and Development (Kementerian Negara Perencanaan Pembangunan, BAPPENAS) is responsible for national development planning and budgeting. It plays a significant role in the planning of social protection programmes with two specific directorates responsible for social protection and poverty alleviation.

Dewan Jaminan Sosial Nasional (DJSN, the national social security council), established under Law No. 40/2004, is mandated to supervise the implementation of a national social security system (SJSN). This legislation empowers the DJSN to formulate general policy and synchronise implementation of the national security system. The DJSN works under direct supervision of the President and consists of government officials, experts in social protection, and members of employers and workers associations.

The DJSN is responsible for overseeing Badan Penyelenggara Jaminan Sosial (BPJS, the social security administrative body). BPJS, established under Law No. 24/2011, is responsible for social security policy development, harmonisation of the implementation of social security schemes, and monitoring social security funds. The BPJS law consolidated social insurance programmes under two independent bodies: BPJS Kesehatan (Health) and BJPS Ketenagakerjaan (Labour).

BPJS Health is responsible for achieving universal health coverage in Indonesia through the Program Jaminan Kesehatan Nasional (JKN, national health insurance). This programme includes both contributory and non-contributory components, thus cutting across the social assistance and social insurance pillars. Within the contributory component are three classes of member: wage recipients, non-wage recipients, and retirees and veterans. Different contribution rates apply for each category.

Under the BPJS Law, BPJS Labour is responsible for managing the old-age benefit, work accident insurance, death benefit and new pension programmes. The social security programmes for workers in the public sector, currently implemented by PT TASPEN and PT ASABRI, are scheduled to merge with the BPJS Labour programmes in 2029.

The National Team for Accelerating Poverty Reduction (Tim Nasional Percepatan Penanggulangan Kemiskinan, TNP2K) was established by Presidential Decree No. 15/2010 and reports to the Vice President. It is responsible for developing regulations and programmes for poverty reduction, for ensuring synergies across programmes through synchronisation, harmonisation and integration of poverty-reduction initiatives run by various line ministries.

The role of the TNP2K overlaps with the responsibilities of some key administrative bodies including the Coordinating Ministry of Human and Cultural Development, MoSA, BAPPENAS and the National Statistics Bureau. Its status is determined by the degree of support it receives from the President’s office.

MoSA is the lead agency for multiple social assistance programmes, including cash transfers and some social services such as rehabilitation and housing support. It does not have direct reporting requirements to DJSN, despite the latter’s co-ordinating function for social protection. Since 2015, MoSA has been responsible for managing data on the poor population, specifically for the social protection programmes targeting the poor, a role previously undertaken by Central Bureau of Statistics. This expansion of its workload was not matched with a concomitant increase in resources. While MoSA is responsible for the management and delivery of cash transfer programmes, sectoral programmes and subsidies are managed and run by individual line ministries.

Shared system functions should be expanded

Indonesia has developed a single targeting mechanism for social assistance programmes but does not have an integrated management information system. This constrains the GoI’s capacity to monitor and evaluate the functioning of social assistance programmes and to ensure that beneficiaries are receiving all the benefits to which they are eligible.

The absence of a management information system for social assistance is partly a function of fragmentation in the sector, not to mention the challenge of co-ordinating information flows across a country as large and diverse as Indonesia. Numerous programmes exist and responsibility for social assistance programmes at a national level is divided between MoSA, the Ministry of Education and numerous other institutions. Sub-national governments also have an important role in implementation. This situation has made it impossible to co-ordinate information systems as well as meaning that each programme has its own operational processes, monitoring and evaluation strategies, beneficiary lists and budgets (TNP2K, 2018[1]).

The rapid scale-up of certain social protection programmes has magnified the challenge of establishing and maintaining information systems. This has been a particular problem with PKH. As the World Bank’s Programme Appraisal Document for PKH notes, the programme’s existing management information system ‘was not designed to manage millions of beneficiary families and its performance, capability, and reliability have become so inadequate that many administration tasks cannot be carried out effectively, hampering efficiency, transparency, and accountability of the programme’ (World Bank, 2017[2]).

This situation is made harder by the fact that social assistance programmes do not use a single identification number. An individual might have multiple identification numbers if he or she was enrolled in multiple programmes in addition to national personal and family identification numbers. Box 5.1 explains how a new set of identification cards is helping to improve coherence in this regard.

Only once the scale-up plateaus will it be possible to fully understand the strengths and weaknesses of the PKH information system. At this point, it will be important to implement the action plan proposed by the World Bank to develop an adequate data system for the programme and establish the capacity required to monitor such a system. Meanwhile, MoSA will need to enhance its ability to collect and analyse data from other programmes.

Over the longer term, an ideal end-point would be a single management information system for social assistance. The lack of such a system places considerable financial and administrative strain on individual ministries to continually gather and update data that could be centrally managed with cost-sharing across programme implementing agencies. An integrated database would also simplify and streamline regular monitoring and evaluation through independent agencies.

Meanwhile, social insurance bodies such as BPJS Health, BPJS Labour, TASPEN and ASABRI have more sophisticated information systems that record all information relevant to their various programmes and the key indicators to measure programme risk. However, these are not sufficiently well co-ordinated or used to expand social insurance coverage.

Build on and refine the Unified Database

The Unified Database (UDB) is underpinning the development of a social assistance system in Indonesia. Covering approximately 27 million households (or 96 million individuals) in 2018, it not only serves as a targeting mechanism for a number of social protection programmes but also to ensure that beneficiaries eligible for one programme also receive other benefits to which they are entitled. From the perspective of the beneficiary, the UDB significantly increases the likelihood they will emerge from poverty by ensuring they access to a number of complementary social protection initiatives. From a systems perspective, the UDB ensures coherence between programmes in terms of whom they are targeting and serves as a basis for co-ordination.

However, not all ministries have opted to use the UDB for targeting or beneficiary selection with many, such as the Ministry of Education and Culture, adopting their own processes either due to outdated information in the UDB or due to missing variables that are integral to their targeting approaches. As a consequence, the intended beneficiaries of social assistance programmes often do not benefit from all the programmes to which they are entitled. Implementers of different programmes or local administrations attempt to address exclusion errors that might result from imperfect application of the UDB targeting. However, TNP2K (2018[1]) finds that “this results in an absence of centralised beneficiary management lists and a targeting system susceptible to bias by local actors”.

Exclusion from one or more social protection programme for which a beneficiary is eligible is a major constraint on the overall effectiveness of the system in reducing poverty. As the World Bank (2017[3]) notes, “While each individual program is relevant for poverty reduction by creating a transparent pathway for beneficiary households to mitigate a clearly-defined risk, none of these individual initiatives is by design to help all targeted households fully mitigate or absorb all risks.” Equally, the limited resources available to social protection also mean that inclusion errors can significantly reduce the poverty-reducing impact of the system as a whole. As shown in Chapter 3, this is a particular issue with the RastraRastra programme, which absorbs a significant portion of the overall allocation to social protection.

In the future, the UDB will be managed by the Sistem Informasi Kesejahteraan Sosial Next Generation (SIKS NG). SIKS NG will link databases managed by MoSA and other ministries, state-owned banks and BPJS. The regular verification and validation process will involve sub-national government. Online and offline SIKS applications were launched in 2017 and will be updated regularly. The government has identified two critical challenges to ensuring the success of the SIKS NG: lack of administrative capacity at the data entry, verification and validation level and ensuring implementing ministries use the new integrated system for their programmes.

Identity cards have an important role to play in developing a social protection system in Indonesia. Not only can they foster integration between schemes and thus expand coverage but they also have the potential to improve the efficiency of cash-based payment systems and promote beneficiaries’ financial inclusion. However, gaps in national registration processes are resulting in the exclusion of poor and vulnerable individuals.

The national identification card, known as the Kartu Tanda Penduduk (KTP) is the cornerstone of public administration. All citizens require a KTP to access public services. The card (which is valid for life) contains biometric information on cardholders that is stored electronically. The children’s identity card (Kartu Identitas Anak, KIA) is the equivalent of the KTP for children up to the age of 17. Newborn children are supposed to be issued with a KIA at the same time as they receive a birth certificate. The objective is for all children should possess a KIA by the end of 2019.

The Prosperous Family Card (Kartu Keluarga Sejahtera, KKS) is the basis for eligibility for social assistance and is provided to heads of families identified as being poor or vulnerable by the UDB. Giving effect to Presidential Regulation No. 63/2017 on Cashless Social Assistance Distribution, the KKS is linked to a bank account, which enables social protection beneficiaries to receive transfers electronically, thereby promoting their financial inclusion. It replaced the social protection card (KPS), which was provided to households eligible for the unconditional cash transfer (BLSM).

Households with a KKS that have children between age 6 and 21 in full-time education should automatically receive the Smart Indonesia Card (Kartu Indonesia Pintar, KIP), allowing them to receive the Program Indonesia Pintar (PIP). In the same way, holders of the KKS should also automatically receive the Healthy Indonesia Card (Kartu Indonesia Sehat, KIS), which entitles them free access to healthcare as PBI beneficiaries of JKN.

The KKS is provided by four banks (Bank Rakyat Indonesia, Bank Negara Indonesia, Bank Tabungan Negara and Bank Mandiri). By connecting beneficiaries to the formal banking sector (leveraging the high penetration of mobile technology across the population), the KKS contributes to the GoI’s commitment to enhancing financial inclusion among the poor and vulnerable. This enables beneficiaries to save and borrow.

The cards not only serve as a means of receiving benefits but can also be used to purchase subsidised goods in special shops (e-Warong). These shops are run by groups of beneficiaries enrolled in the PKH-KUBE programme in an initiative implemented by MoSA with the collaboration of other government agencies, the financial regulatory authority and commercial banks (World Bank, 2017[3]).

While Indonesia’s identification cards hold significant potential as a mechanism for greater systematisation of social protection as well as greater financial inclusion for beneficiaries, it must overcome a fundamental challenge with the KTP. Coverage of the KTP is not universal; estimates of the number of children in Indonesia without birth certificates range from 29% (or 24 million children) to 47% (DFAT/PEKKA/PUSKAPA UI, 2015[4]). This means that large numbers of children risk exclusion from social protection for administrative reasons. Lack of registration is particularly high among low-income households, with evidence showing the cost of registration to be the principal impediment, especially in remote areas (Duff, Kusumaningrum and Stark, 2016[5]).

A major challenge for the UDB is keeping track with the dynamics of poverty and vulnerability discussed in Chapter 1. Although the stock of poor and vulnerable households might have been relatively stable at 40% over recent years, there have been significant flows between income groups by individuals and households. Moreover, the overall poor and vulnerable population is shrinking as a proportion of the population.

From 2017 onwards, a decree by MoSA requires that the UDB be updated twice per year, in May and November. Sub-national governments can update it at any time. However, households in many parts of the country are difficult to reach and the demands associated with regularly updating the database, both in terms of cost and capacity, are often beyond local administrations. They might also not recognise the value or importance of doing so.

In this context, it is critical that individuals themselves are aware of their entitlements and are able to request enrolment in a programme for which they might be eligible. Indonesia has made progress in this regard through the development of single-window services and on-demand application. These interventions also yield important gains in terms of strengthening the social protection system.

MoSA’s integrated referral system (Sistem Rujukan dan Layanan Terpadu, SLRT), which operates at the district level, allows facilitators to identify poor and vulnerable households to ensure they are receiving appropriate social protection support. Following a successful piloting, SLRT is expected to be operating in 150 districts in 2019. On-demand application, which allows individuals to request enrolment in a programme, is a component of the SLRT but is managed by TNP2K. It currently operates in 12 districts. The SLRT is also equipped to deal with grievances (World Bank, 2017[3]).

Single window services have achieved some notable success in Indonesia in recent years. However, these are typically a mechanism by which local governments can improve access to (and provision of) local services. In this case, the SLRT is intended as a means for local governments to enhance access to national.

Nonetheless, the SLRT has the potential to improve the responsiveness of the social protection system and reduce targeting errors by keeping track of individuals moving in and out of poverty. It can also ensure beneficiaries are accessing the programmes to which they are eligible and, where needed, move beneficiaries from one programme to another.

Clarify and optimise sub-national government’s role in social protection

As discussed in Chapter 4, responsibility for social protection provision is shared between national and sub-national government as a concurrent function. Such an arrangement is consistent with other countries, where local administrations not only support the implementation of national social protection programmes and strategies but also monitor their impact and performance and provide reliable information that can inform policy-making at the national level. However, in Indonesia’s case, the degree of decentralisation and the variation that exists across the country make it a particular challenge as far as establishing a social protection system is concerned.

Sub-national governments are able to implement their own social protection programmes even though the Ministry of Home Affairs Regulation No 32 of 2011 prevents local governments from providing cash transfers to households on an ongoing basis. As TNP2K notes, “an increasing number of districts and provinces have been introducing their own social protection schemes…there is a danger that this proliferation…will reduce cohesion and co-ordination within the broader social protection system. Furthermore, challenges with existing regulations restrict local governments’ ability to design their own cash transfer programmes” (TNP2K, 2018[1]).

Another challenge with decentralisation relates to targeting. As with any sample survey, the data that served as the basis for the UDB is imperfect. Moreover, considerable time has elapsed since that survey and, as discussed above, the architecture required to ensure the UDB remains up to date is not yet in place. In this context, sub-national administrations have understandable misgivings about the UDB and are empowered to influence who receives the benefit, meaning they can correct for exclusion errors.

Ad hoc involvement by sub-national administrations in the targeting of benefits for different programmes makes it less likely that beneficiaries access all the programmes for which they are eligible. Moreover, eligibility can also be determined by local political factors, generating inclusion errors and diluting the resources available for poor and vulnerable households. Enforcing common standards for implementation is rarely practical, especially given the challenges related to social workers (also known as facilitators) discussed below. Mechanisms and opportunities for co-ordination between sub-national administrations and the central government are limited.

Although some 88% of social assistance spending is financed centrally, sub-national governments’ fiscal autonomy empowers them to contribute to the financing of social protection (Jellema and Hassan, 2012[6]). In theory, they are expected to top-up social protection budgets to increase benefit payments and finance the operations of facilitators. In practice, these contributions have never been formalised. However, certain sub-national governments implement social protection programmes of their own design, targeted at beneficiaries according to their own criteria.

This has been observed with the Village Funds. Although almost 90% of Village Fund expenditure is allocated to local infrastructure development, there is evidence that village administrations also provide cash transfers and food to households that they consider in need of support, without regard for national registries (Gama, Saget and Elsheikhi, 2018[7]). Indeed, a household might receive support precisely because they are not eligible for a national social protection programme.

As a result, the implementation of reforms designed by national social protection planners might differ widely from what was intended. This undermines attempts to reduce poverty by expanding a specific programme. As the World Bank (2017[8]) notes, “entrenched and idiosyncratic operating principles suggest that increasing any single programme’s coverage will bring only a small percentage of targeted households a ‘full’ benefit”.

Looking ahead, Indonesia’s progress towards universal health coverage has been an international success story but also provides a cautionary tale regarding how tensions between national and sub-national government can delay reform. In the early 2000s, health provision emerged as a key electoral issue at the sub-national government level, which in turn raised the level of political commitment at central government. Subsequent initiatives to enhance health coverage that were driven by national government, including JKN itself, have encountered resistance from sub-national governments reluctant to give up their schemes (Pisani, Kok and Nugroho, 2017[9]).

Empower social workers to implement and strengthen social protection policies

Social workers, known as facilitators in Indonesia, play a critical role in any social protection system. They have the face-to-face contact with poor and vulnerable households required to ensure they are receiving the holistic support they need (beyond income), and they have unique insight to how well social protection programmes – national or otherwise – are responding to people’s needs and how well such programmes are being implemented.

Social work faces fundamental challenges in Indonesia. It is not universally considered a profession and there are shortcomings in the education and training social workers receive. Consistent with many countries in South-East Asia, policies to elevate the status of social workers and improving their training are required. The GoI, which is the principal employer of social workers, has a role to play in both, by fully recognising and clearly articulating the role of social workers, by implementing regulations that govern their work, and through quality assurance for their training (O’Leary et al., 2018[10]).

Progress has been made towards addressing these challenges, in part as a consequence of the national and international response to the tsunami in Aceh in December 2004. Nonetheless, the potential of social workers to support the implementation of a social protection system is largely under-utilised. Facilitators are employed by MoSA, not as permanent employees but on the basis of annual contracts, which is a constraint on the development of a large, well-qualified body of social workers in social protection.

The principal responsibilities of facilitators are to ensure that eligible individuals receive benefits and to monitor compliance with conditionalities. As Chapter 2 notes, PKH is placing greater emphasis on supporting families more broadly. This is consistent with emerging evidence that supporting parents is critical for enhancing the cognitive developmental of young children, underlining the importance of embedding cash transfers such as PKH within a broader set of interventions aimed at families as a whole (Aboud and Yousafzai, 2015[11]; Arriagada et al., 2018[12]).

At the time of writing, not enough is known about the specific workloads (or the time required to fulfil these workloads) of social workers across Indonesia. It is therefore not possible to assess whether sufficient facilitators are employed or whether they possess adequate skills. All facilitators are supposed to receive centralised training courses when they start, but financial and logistical factors mean this doesn’t always happen. These factors also limit the possibility to provide further training to bring social workers up to speed with social protection reforms. Given the speed with which PKH and other programmes have scaled up in recent years, not to mention the complexity of the overall social protection system, it is not realistic to presume facilitators will be able to keep up.

Continue to consolidate social assistance programmes

The current approach to social assistance is one of targeting (resources to individuals most in need through a number of complementary arrangements that, together, will allow them to exit poverty on a sustainable basis. With the key social assistance programmes meant to be using the UDB and an associated system of cards to designate eligibility, the underlying architecture appears to be in place. However, it is frequently not the case that a poor individual will receive all the benefits to which they are entitled: in 2014 (before UDB was as widely used across social assistance programmes as it is today), less than 30% of families in the poorest decile that were receiving PKH also benefited from PIP and Rastra and were registered as PBI (World Bank, 2017[2]).

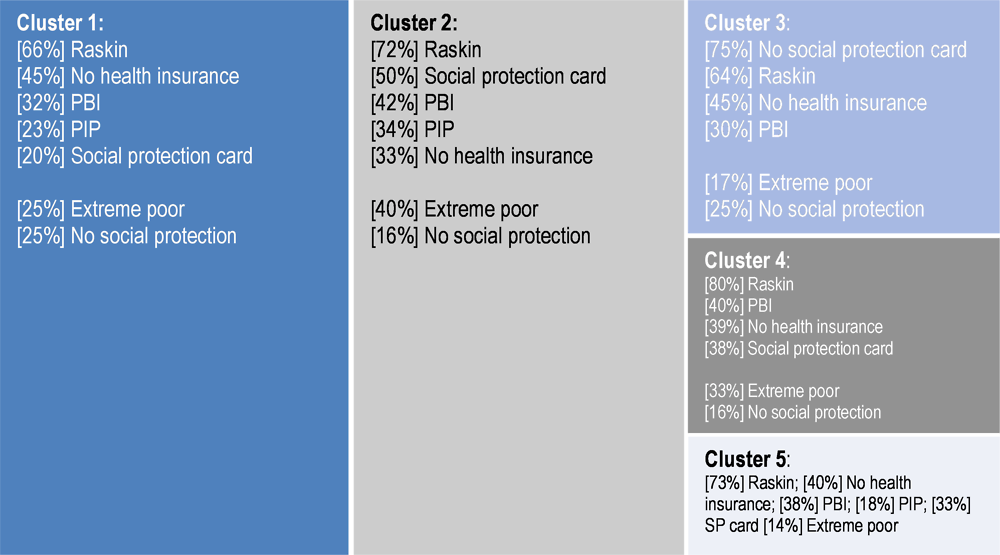

This picture of fragmented coverage is borne out by the Latent Class Analysis (LCA) carried out in Chapter 1. Figure 5.1 identifies coverage of social protection mechanisms amongst the five poor clusters identified in Chapter 1 using data from Susenas 2016 (excluding PKH, receipt of which was not specified by the survey). It demonstrates significant variation between the different clusters in terms of which social protection programmes they receive (including health insurance). Raskin is the only programme with coverage in excess of 50% in any of the poor clusters. This exercise also shows low coverage of social protection cards.

The challenges inherent to linking poor households to a range of complementary interventions indicate a need to rationalise programmes in alignment with the vulnerabilities identified by the LCA in Chapter 1 and invest in the ones that are most effective in reducing poverty. For example, to address child poverty, there is overlap between PKH and the PIP.

This report supports the recommendation of TNP2K that PKH and PIP be merged. The results of Chapter 3 indicate that PKH is more effective at reducing poverty and support the GoI’s decision to continue scaling up the programme. The logic for maintaining both programmes is weakening. However, this is unlikely to be straightforward, given that different ministries are responsible for implementing these programmes and the populations covered by the respective programmes are different (even though by design there should be significant overlaps).

This report also acknowledges TNP2K’s proposal that PKH does not serve as a mechanism for providing benefits to poor and vulnerable elderly individuals or those with severe disabilities, since benefits to these groups should be provided by other social protection programmes. However, incorporating a benefit for the elderly within PKH has been a critical means of increasing support for such an intervention and has thus made it more likely that poor elderly individuals will receive some form of public income support.

Universalisation of a child grant would eliminate a number of the institutional and geographical factors responsible for the low levels of coverage currently achieved by PKH. However, the cost would be prohibitive, unless benefits are so low as to have a minimal impact on poverty. It would be difficult to achieve universal coverage of a child grant given the large numbers of children without proper identification, including birth certificates.

Scaling up and better targeting an integrated PKH-PIP benefit to cover the 23 million children registered on the UDB might represent the optimal outcome. This expansion should be accompanied by a concerted effort to enhance access to early childhood education and learning facilities and other complementary interventions.

Prepare for growing pressure around benefits for the elderly

As Chapter 1 discusses, old-age poverty is high and has not achieved the same decline as poverty among children in recent years. Given the challenges inherent to increasing social insurance coverage in Indonesia (discussed below), pressure for more effective social assistance for the elderly is likely to build as Indonesia’s demographic transition progresses. This would also be a mechanism for mitigating the disadvantages women face over the course of their lives.

TNP2K proposes a universal pension for all individuals aged 70 and over who are not in receipt of a contributory pension (TNP2K, 2018[1]). At the present time, this proposal is unlikely to gain traction: the financial implications of such an intervention would be very large and there is a lack of both political and popular demand for the measure. Nonetheless, it is important to prepare the social protection system as a whole for the rapid ageing of the population, rather than relying solely on growth in social insurance arrangements. As such, it is important to consider the scope and design of both contributory and non-contributory arrangements.

Social assistance for the elderly should be harmonised with social insurance arrangements in order to establish a coherent set of public policies for individuals in retirement. TNP2K’s proposal that a social pension be provided from age 70 onwards would create a large discrepancy in retirement ages between social assistance and the contributory system (where the retirement age was 56 for men and women in 2018 but will rise to 65 over time).

Taking advantage of the greater consistency of retirement ages across different programmes, Thailand established a voluntary savings scheme, the National Savings Fund, in 2015 by which individuals can supplement the low monetary value of the old-age allowance without jeopardising their access to it. Indonesia’s old age savings scheme provides social insurance access to non-wage earners, including low contribution rates for those with low incomes, but members must also contribute to schemes providing survivor benefits and compensation for injury at work. BPJS is considering subsiding these contributions for the poor and at-risk to enhance the affordability, flexibility and attractiveness of the saving scheme (TNP2K, 2018[1]).

As Chapters 1 and 3 of this report demonstrate, girls and women in Indonesia tend to be poorer than men at almost every stage in the life cycle. Disadvantages women face earlier in life, for example a lower likelihood of completing education, have a significant impact on their prospects at working age. Female labour force participation is much lower than the equivalent metric for men and women’s incomes are lower as a result. The cumulative effect is to leave women extremely vulnerable in old age.

Indonesia’s current social protection system does little to address the disadvantages women face over the course of their lives. When considering the future of social protection in Indonesia, it will be critical to ensure reforms are gender-sensitive and mitigate rather than reinforce these disadvantages.

As Chapter 3 notes, promoting social insurance coverage of the informal sector and recognising the impact of child-bearing on women’s potential to contribute to such arrangements will be very important in this regard. Higher social assistance coverage among the elderly would also help to reduce women’s vulnerability in old age.

Strengthen the contributory system to reach the missing middle

As this review has identified, Indonesia confronts a significant missing middle problem. Although poverty has declined significantly since the Asian Financial Crisis, the proportion of the population classified as poor and vulnerable has remained relatively consistent, at around 40% of the population. Social assistance programmes have predominantly been targeted at households in extreme poverty, while only households at the high end of the income distribution are enrolled in pension programmes. At the heart of the missing middle problem lies the high proportion of workers in informal employment.

Through the SJSN and BPJS Laws of 2004 and 2011, social insurance has been at the forefront of systematisation of social protection. Institutional arrangements for health and labour insurance have been integrated into BPJS Health and Labour respectively, with DJSN providing oversight of both. At the same time, new programmes have been added to broaden coverage of contributory arrangements. However, health and labour social insurance arrangements have very different administrative and financial modalities, which limits the extent to which co-ordination between them is feasible.

Rapid growth in the proportion of the population covered by health insurance has been the major success story of social protection in Indonesia. By using general revenues to subsidise contributions of individuals with limited capacity to contribute, it is on the way to achieving universal health coverage in a relatively short period of time. However, its success has come at a cost: overcoming the missing middle challenge has resulted in adverse selection and behavioural responses outlined in Chapter 3 that are undermining the sustainability of the system.

BPJS Labour has also sought to distinguish between different types of member as a means of expanding coverage, establishing different arrangements for wage and non-wage workers. As mentioned above, contributions are lower for non-wage workers (who are not enrolled in the new JP scheme) but the GoI does not subsidise pension contributions like it does health contributions.

Although this dual system might facilitate enrolment in at least one public programme, it weakens the coherence of the retirement landscape. If some form of social pension were to be introduced, it would be important that it doesn’t serve to further fragment this space; a requirement that social pension recipients do not receive other forms of pension might control costs of universalisation but it would reduce coherence.

Faced with perhaps the fastest demographic transition ever registered (as well as a large-scale informal sector), Viet Nam is making a major push to increase pension coverage. Following China’s example, a social insurance reform in 2014 has made it much easier to enrol in social insurance for low-income workers in agriculture and the informal sector on a voluntary basis. However, low contribution rates will translate into low pensions in retirement.

The composition of the informal sector indicates that a differentiated strategy for reaching this group is required. The proportion of the informal workforce classified as employees and own-account workers respectively is very similar; together they account for 85% of the informal labour force. Recent experience from Viet Nam indicates that increasing coverage in small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) is critical to reaching individuals in the middle of the income distribution (Castel and Pick, 2018[13]).

Although Indonesia’s SME sector is not an extensive as Viet Nam’s, it accounts for 97% of domestic employment (OECD, 2018[14]). Expanding coverage among these workers would go a long way towards enhancing social insurance coverage in Indonesia and might also promote higher levels of formalisation and tax compliance. A combination of contribution incentives and stronger enforcement are likely to hold the key to expanding coverage amongst Viet Nam’s SMEs and might do likewise in Indonesia (Castel and Pick, 2018[13]).

Increasing social insurance coverage (and enhancing formalisation) will require a broader restructuring of employment legislation in Indonesia. Current severance pay arrangements impose a cost on compliant employers and risk distorting employment decisions. As a result, many employers do not implement these arrangements properly, leaving employees vulnerable to a sharp loss in income in the event they lose their jobs, especially since Indonesia lacks an unemployment insurance scheme. Reviewing these arrangements while incentivising and enforcing employer contributions to social insurance has the potential both to better protect the employee and to improve the functioning of the labour market.

An issue for consideration in this regard is whether Indonesia requires an unemployment insurance fund. Viet Nam has such a fund but it is notable that it does not seem to prevent workers from wanting to access retirement savings when they change job. In the Indonesian context, the provident fund serves the purpose of a precautionary saving arrangement for formal sector employees.

A bright future for social protection but higher funding is needed

A number of the reforms proposed in this report are far-reaching, institutionally disruptive, or difficult to implement. They will require strong political will and technical expertise. Recent evidence indicates that these necessary conditions for reform are falling into place. Social protection in Indonesia has received strong support from successive administrations since the Asian Financial Crisis. This has been a critical factor behind some the passage of the two landmark social insurance laws and, more recently, the scale-up of social assistance.

The current president, Joko Widodo, has played a key role in raising the profile of social assistance. A presidential election scheduled to take place in 2019 raises the possibility of a change in administration. However, the integration of social protection in key policy frameworks reduces the extent to which the momentum behind social protection would be reversed in that eventuality.

Donors are playing a critical role in supporting the development of a social protection system. Although volumes of official development assistance have declined substantially since Indonesia graduated from the International Development Association in 2009, development partners are supporting the development of social protection system through technical assistance and financing support, exemplified by the World Bank’s PKH loan mentioned in Chapter 4.

At present, a lack of financing is the greatest constraint to the effectiveness of social protection. Although social protection is becoming a high budget priority and will even drive higher overall public spending in 2019, Indonesia’s tax revenues remain too low to allow for a major scale-up of social protection in the short-to-medium term. Spending will increase in absolute terms but is likely to remain below 2% of GDP. Recent increases in tax revenues will need to be sustained to increase the social protection system’s capacity to reduce poverty and inequality.

References

[11] Aboud, F. and A. Yousafzai (2015), “Global Health and Development in Early Childhood”, Annual Review of Psychology, Vol. 66/1, pp. 433-457, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-010814-015128.

[12] Arriagada, A. et al. (2018), Promoting early childhood development by strengthening linkages between cash transfers and parenting behaviors, World Bank, Washington DC, http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/489331538646764960/pdf/130492-WP-PUBLIC-P163425-BriefCombiningCashTransfersandParentingInterventionsWEB.pdf (accessed on 7 February 2019).

[13] Castel, P. and A. Pick (2018), “Increasing social insurance coverage in Viet Nam’s SMEs”, OECD Development Policy Papers, No. 13, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/ec14725e-en.

[4] DFAT/PEKKA/PUSKAPA UI (2015), AIPJ Baseline Study on Legal Identity: Indonesia’s Missing Millions, Australia Indonesia Partnership for Justica (AIPJ), Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT); Perempuan Kepala Keluarga (PEKKA); Pusat Kajian dan Advokasi Perlindungan dan Kualitas Hidup Anak, Universitas Indonesia (PUSKAPA UI), http://www.dfat.gov.au (accessed on 16 January 2019).

[5] Duff, P., S. Kusumaningrum and L. Stark (2016), “Barriers to birth registration in Indonesia”, The Lancet Global Health, Vol. 4/4, pp. e234-e235, https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(15)00321-6.

[7] Gama, A., C. Saget and A. Elsheikhi (2018), Labour Market Inventory ASEAN 2010-15: Labour market policy in an age of increasing economic integration, International Labour Organization, Geneva, https://www.ilo.org/global/research/WCMS_650064/lang--en/index.htm (accessed on 30 January 2019).

[6] Jellema, J. and N. Hassan (2012), “Protecting poor and vulnerable households in Indonesia : Main report”, in Public Expenditure Review (PER), World Bank, Washington, DC, http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/459361468044650535/Main-report.

[14] OECD (2018), SME and Entrepreneurship Policy in Indonesia 2018, OECD Studies on SMEs and Entrepreneurship, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264306264-en.

[10] O’Leary, P. et al. (2018), “Developing the social work role in the Indonesian child protection system”, International Social Work, Vol. 00/0, pp. 1-15, https://doi.org/10.1177/0020872817747028.

[9] Pisani, E., M. Kok and K. Nugroho (2017), “Indonesia’s road to universal health coverage: a political journey”, Health Policy and Planning, Vol. 32, pp. 267-276, https://doi.org/10.1093/heapol/czw120.

[1] TNP2K (2018), The Future of the Social Protection System in Indonesia: Social Protection for All, The National Team for the Acceleration of Poverty Reduction, Jakarta.

[8] World Bank (2017), Indonesia Public Expenditure and Financial Accountability, World Bank, Jakarta, https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/29820 (accessed on 31 January 2019).

[2] World Bank (2017), Program Appraisal Document on a Proposed Loan in the amount of US$200 million to the Republic of Indonesia for a Social Assistance Reform Program, World Bank, Washington DC, http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/353221496152466944/pdf/Program-Appraisal-Document-PAD-disclosable-version-P160665-2017-04-15-04202017.pdf (accessed on 16 January 2019).

[3] World Bank (2017), Towards a Comprehensive, Integrated, and Effective Social Assistance System in Indonesia, World Bank Group, Washington, DC, http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/535721509957076661/Towards-a-comprehensive-integrated-and-effective-social-assistance-system-in-Indonesia.