6. The role of non-governmental actors in taxpayer education

This chapter emphasises that taxpayer education is not the sole preserve of tax administrations, providing a brief summary of the role of non-governmental actors. It looks at the role of both civil society organisations and businesses, focussing on areas where they may be better placed than tax administrations to deliver taxpayer education initiatives.

While the survey only focussed on the role of tax administrations in taxpayer education, it is not an activity undertaken solely by them. Taxpayers do not get all their information from the administration and there are numerous actors who have the potential to play a role in taxpayer education; including the media, civil society organisations, academics, think tanks, businesses and business associations.

As the survey has shown, in many countries governments recognise the potential for non-governmental actors and are actively collaborating with them in taxpayer education initiatives. The survey featured 57 initiatives that refer to partnerships with non-governmental actors. The previous chapters have shown how these partnerships can be valuable in enabling initiatives to reach the target audiences, among whom non-governmental actors may be more trusted or have better access.

The role of non-governmental actors in taxpayer education is broad and goes beyond the scope of this report. This report is designed primarily to help understand the role tax administrations can play in taxpayer education; it is beyond the scope of this report to undertake a full mapping of the role non-governmental actors play. Consequently, it may be that the typology created in this report does not fully capture all the types of taxpayer education initiatives undertaken by non-governmental organisations.

This section does not, therefore, aim to provide a comprehensive description of the role of non-governmental actors, but merely to serve as a complement to the rest of the report and encourage further analysis of the role and function of non-governmental actors in taxpayer education. There is currently relatively limited research on the role of non-governmental actors, especially beyond civil society actors; further research could be of value, especially in understanding the impact of non-governmental actors in taxpayer education.

Many civil society organisations (CSOs) are actively engaged in taxpayer education activities, but there may be scope for them to do more. CSOs are non-governmental and generally not-for-profit entities which don’t represent commercial interests; they promote, rather, the public interest. While there has not been a comprehensive study of the role of CSOs in taxpayer education, there have been a couple of studies in recent years. These studies highlighted the active engagement of a number of CSOs in taxpayer education activities, yet within the range of functions CSOs perform with relation to taxation, taxpayer education appears the least widespread. This suggests that there may be untapped potential. Box 6.1 summarises the recent research.

Both the Overseas Development Institute (ODI) (Sharp, Sweet and Rocha Menocal, 2019[1]) and the International Budget Partnership (IBP) (Mohiuddin and de Renzio, 2020[2])have undertaken research on CSOs activities involving tax, with a particular focus on developing countries. The ODI study looked across eight countries (Brazil, El Salvador, Kenya, Nigeria, the Philippines, Uganda, the United States and Zambia), while the IBP study created a dataset of 171 CSOs across 66 countries and obtained further details on 38 of these through an online survey. Both studies created broad categories to describe the various functions that CSOs undertake with respect to tax and noted how common it is for CSOs to fulfil these functions. Table 6.1 below summarises the findings:

In these studies, the functions most clearly related to taxpayer education were those involving awareness raising on tax and literacy/awareness. Both studies find that these functions are the least common, although the IBP finds that nearly half of CSOs are undertaking some activities in this area and notes that the ODI survey “probably underestimated how much activity is happening in this area” (IBP, 2020). What is interesting in the case of the ODI study is not the low level of activity on awareness raising, but that CSOs are already engaged in that activity and that there was an identified need for them to do more in this regard, although funding was challenging. ODI also noted that such activity was taking place in lower-income countries, often at the sub-national level.

The IBP study dataset shows that all the CSOs undertaking literacy/awareness activities are also engaged in at least one other function, highlighting how the taxpayer education functions undertaken by CSOs are likely to be linked to other priorities (e.g., providing citizens with sufficient knowledge and understanding to participate in advocacy/campaigning or to effectively engage in holding governments to account). In addition, most CSOs working on tax are also working on the way in which governments spend their resources: 89% of those surveyed by IBP.

Both reports note a strong focus by many CSOs on international taxation issues and/or corporate tax issues; there may be less scope to develop taxpayer education initiatives in these areas, as the priority of CSOs on these issues is generally to engage the government and/or general public rather than taxpayers specifically (generally multinational enterprises).

Especially in developing countries, civil society engagement on tax is highlighted in both reports as being relatively recent and continuing to evolve, including with respect to taxpayer education. The ODI study notes that many CSOs have limited technical tax capacity at the moment. This may limit the role they can play in taxpayer education currently but suggests there may be scope for expansion as capacity increases. The ODI study concludes that there is the “potential to foster civil society collaboration with the government in increasing tax compliance, while nurturing a stronger connection between tax collection, expenditure and accountability demands.” Research from Save the Children complements these findings (Wainer, 2019[3]), identifying a number of case studies of successful CSO contributions in developing countries and noting the scope for expansion. It also notes that when looking at engagement on domestic taxation issues, CSOs have been most impactful at the sub-national level, where there are closer/more direct links to service delivery, as well as to politicians and policy makers. Such sub-national activities were also found to involve greater collaboration with the authorities than national-level activities, where conflictual relationships were more likely to be observed.

Source: Author, from (Sharp, Sweet and Rocha Menocal, 2019[1]; Mohiuddin and de Renzio, 2020[2]; Wainer, 2019[3]).

Civil society organisations may have different objectives than tax administrations in engaging in taxpayer education. While the primary objective of most government-run initiatives is to improve voluntary compliance, that may not be the case for CSOs. CSO taxpayer education activities are much more likely to be related to objectives on tax policy, or to improving government accountability and providing sufficient understanding of tax matters to enable citizens to engage in tax policy discussions, or to ask the right questions on the functioning of the tax system so as to hold governments to account. While these different objectives among tax administrations and CSOs may produce an overlap in terms of the type of taxpayer education activities needed, creating the opportunity for partnerships, as demonstrated by the range of partnerships described in our survey, this will not always be the case.

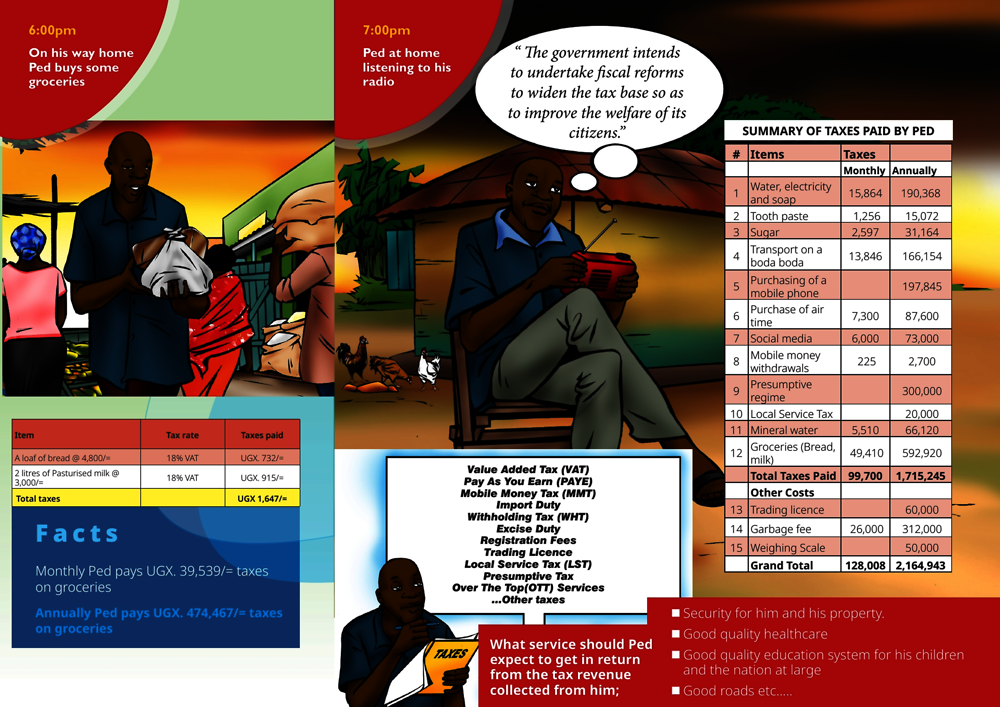

Equipping citizens with the tools to hold the government to account for the tax system is an important part of the social contract, and CSOs are especially well placed to fulfil this role. While the advocacy that many CSOs engage in may be beyond the remit of taxpayer education, helping citizens to know how to engage in their own advocacy towards the government, and how to use data to hold the government to account, is an important function that can help build trust in the tax system in the long term. The Uganda-based CSO SEATINI (The Southern and Eastern Africa Trade Information and Negotiations Institute) demonstrates this approach with their A Day in the Life of a Ugandan Tax Payer, which seeks to identify all the ways in which a Ugandan citizen engages with the tax system on a given day, encouraging people to reflect on the services provided in return (Figure 6.1). CSOs are well placed for this role because of their independence from the government, their generally good understanding of the communities they represent and their ability, as a result, to tailor initiatives to people’s needs. CSOs can therefore make effective partners for taxpayer education initiatives that are seeking to increase the accountability of the tax system (as covered in Chapter 4), though in such cases it is especially important to ensure the CSO is able to retain its independence, otherwise trust can be lowered rather than increased.

CSOs looking to hold governments to account will often consider the whole fiscal system, looking at spending decisions as well as revenue-raising policies and administration. This is a much wider remit than revenue authorities may feel comfortable developing themselves, and it may be challenging to set up the cross-government work to enable government-run initiatives to cover the same breadth of issues that CSOs can cover. CSOs can play a vital role in these areas. In some cases, this can be in partnership with the government, in others independently. The Child Rights Networks in Kenya, supported by Save the Children, are an example of how CSOs can encourage accountability (Box 6.2).

Save the Children has been supporting domestic resource mobilisation in Bungoma and Wajir in Kenya since 2018. It facilitates networks of civil society groups that deliver health and other social services to children and families through Child Rights Networks (CRNs). The CRNs work with communities to mobilize input into budget and tax processes.

The activities undertaken by the CRNs include radio programmes and flyers to inform citizens about tax, highlighting the importance of everyone contributing their fair share and illustrating how to participate in tax policy processes.

In Bungoma, CRNs have helped citizens to analyse the operation of the existing tax laws for business permits and market fees, leading to reform proposals being provided to the local county assembly, and adopted. These reforms appear to have been successful, in part thanks to the engagement of taxpayers in the reforms, encouraging compliance because of the taxpayers’ perceived ownership of the policy.

The initiative has also improved the relationship between the CRNs and the government. The relationship had previously been conflictual, as the CRNs had only been advocating on spending decisions, with no recognition of the challenges of restricted budgets. With CRNs now taking a broader focus on tax and spending together, the relationship is reported to have improved, with a greater sense of shared purpose between CSOs and government. This highlights how increasing taxpayer education to hold governments to account does not need to be adversarial.

Source: Save the Children.

Civil society organisations may have more diverse resources, flexibility and access to creative skills, which can help in creating engaging taxpayer education initiatives. While the previous chapters of this report have shown that many governments have been innovative and creative in their approaches to taxpayer education, it can be hard to encourage such an approach within government structures. As reported by many in the survey, securing sufficient resources, both human and financial, is a constraint on many government-run initiatives; in addition, bureaucratic procedures can stifle the creativity of initiatives. While CSOs also struggle with resources, especially financial, the CSOs undertaking taxpayer education initiatives may give them higher priority – and resources – and may be better able to work flexibly, drawing on creative skills for citizen engagement within the organisation.

Businesses and business associations can play a valuable role in taxpayer education, especially for SMEs. While large businesses will generally have tax skills in-house (or be able to contract them), SMEs, especially new (or newly formalised) businesses may be more comfortable accessing information on tax compliance through peers, rather than the government. This may be especially important where the taxpayer has limited trust in and/or experience in interacting with the government and may fear that seeking assistance could result in an investigation or audit. This role has been highlighted by several governments in explaining the importance of partnerships with business associations for the delivery of some initiatives; 14 initiatives featured in the survey were in partnership with business associations.

Providing taxpayer education for companies in the supply chain appears underutilised, but with potential. In an OECD survey on tax-official perceptions of taxpayer behaviour (OECD, forthcoming) in all regions, multinational enterprises (MNEs) were perceived as being more compliant than local companies. While this may in part be a result of their greater resources, including greater access to professional tax skills and services, it does suggest that MNEs could play a useful role in building compliance with local companies in their supply chain. One company that has taken this approach is Safaricom in Kenya. Box 6.3 below shows how Safaricom’s requirement that its vendors demonstrate compliance has led to Safaricom engaging in taxpayer education activities.

Safaricom is Kenya’s biggest corporate taxpayer and together with 19 other companies has committed to the B Team Responsible Tax Principles, which aim to raise the bar on how businesses approach tax and transparency.

As part of this commitment, Safaricom goes beyond its own operations when it comes to compliance. The company ensures tax compliance more broadly by requiring that its vendors – both existing and potential – comply with tax laws. Specifically, tax compliance verification is required before the company will engage procurement partners.

Recognising that vendors may need assistance, Safaricom does not simply make these demands of its vendors – it supports them. If the tax compliance of a vendor is in question, Safaricom partners with them to address the issue. The company also hosts forums for suppliers and partner agents‚ such as its mobile-money partners, to raise awareness of tax policies and promote tax compliance.

Source: Adapted from “The B Team Responsible Tax Principles in Action: Safaricom’s efforts to promote tax compliance in Kenya” (https://bit.ly/2ZXxzeB).

Social enterprises can respond innovatively to specific niches. The survey of government- administered initiatives highlighted that specific groups may have specific needs for taxpayer education, and that it can be challenging for governments to effectively design initiatives to reach such groups. Governments often report partnering with non-governmental actors in such cases, but non-governmental actors may also develop their own initiatives without government involvement. Social enterprises may be especially well-suited to such activities, as social enterprises are businesses that have specific social objectives as their primary purpose; they therefore are able to combine effective business strategies with a social-benefit purpose. CabDost in India is an example of a social enterprise emerging to support the specific niche of taxi drivers, adopting a range of innovative methods and combining taxpayer education with a broader mission to enable formalisation and access to finance (see (OECD, 2019[4]) box 2.1) .

Non-governmental actors can play several roles in taxpayer education, but their full potential has not yet been realised. There are good examples of both CSO and business engagement in taxpayer education, however these are relatively limited. From the limited studies/research available, it seems there is untapped (or at least unreported) potential for non-governmental actors to engage further in taxpayer education. This is likely to be the case also for non-governmental actors not addressed in this chapter (e.g., media and academics).

CSOs are likely to be vital in building a responsive and accountable tax system, but they may require support from donors and/or tax administrations to realise this role. CSOs bring skills and approaches that governments struggle to emulate, especially in reaching specific populations and encouraging accountability in the tax system. In many cases, tax administrations will find it more effective to partner with CSOs than trying to undertake those functions themselves. CSOs’ limited resources in areas such as technical tax capacity can limit their ability to fulfil their potential, and therefore more support is likely to be needed by them. The ODI report encourages donors to support civil society actors parallel to building government capacity, as part of support for building a “tax ecosystem” (ODI, 2019); it also highlights the benefits of flexible funding and longer-term horizons for donor-funded projects. There would appear to be scope to increase funding for CSOs on tax, as only 0.3% of ODA for domestic resource mobilisation currently goes to CSOs.1

Businesses should be encouraged to share and promote best practices. Peer-to-peer learning can be very effective, and some businesses may be best placed to help educate other businesses. Among compliant businesses there should be a clear interest in spreading best practice on tax compliance to ensure fair competition, although there is clear potential for conflicts of interest if this is not well managed. Delivering the learning via business associations may help reduce such risks. Governments may consider encouraging taxpayers recognised by initiatives such as “taxpayer of the year” to become proactive in spreading best practice among their peers. Businesses, investors and others can continue to enhance voluntary principles and to include commitments to support compliance by others on the supply chain by leveraging requirements.

The role of non-governmental actors in taxpayer education should be further researched. There is limited research on the role of non-governmental actors in taxation in general, and especially in taxpayer education. As such it is difficult to get a full picture of the current situation, and especially of the challenges faced (and solutions adopted) by non-governmental actors engaging in taxpayer education. Further research is therefore needed to help build better understanding, and to help tax administrations identify how best they can engage with and support non-governmental actors in pursuing shared objectives on taxpayer education.

References

[2] Mohiuddin, F. and P. de Renzio (2020), “Of citizens and taxes: A global scan of civil society work on taxation”, International Budget Partnership.

[4] OECD (2019), Tax Morale: What Drives People and Businesses to Pay Tax?, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/f3d8ea10-en.

[1] Sharp, S., S. Sweet and R. Rocha Menocal (2019), “Civil society engagement in tax reform”, Overseas Development Institute.

[3] Wainer, A. (2019), “Taxation With Representation: Citizens As Drivers of Accountable Tax Policy”, Save the Children Voices From the Field Blog.

Note

← 1. Average disbursements 2015-2019.