Chapter 1. What TALIS 2018 implies for policy

The international report on the results of the 2018 Teaching and Learning International Survey focuses on the notion of professionalism and examines its various dimensions. This first volume, Teachers and School Leaders as Lifelong Learners, explores the knowledge and skills dimensions of professionalism for teachers and school leaders. This chapter, an overview of the main findings presented in the first volume, offers policy pointers emerging from these findings and discusses trade-offs that policy makers need to consider in designing teacher policies.

A note regarding Israel

The statistical data for Israel are supplied by and under the responsibility of the relevant Israeli authorities. The use of such data by the OECD is without prejudice to the status of the Golan Heights, East Jerusalem and Israeli settlements in the West Bank under the terms of international law.

Professionalism of teachers and school leaders

Teacher professionalism as an overarching framework for TALIS 2018

In today’s knowledge-based economies and societies, knowledge and skills are key to individual and collective success, with high expectations and demands placed on education systems and their teachers and school leaders. Teachers are expected to have a deep and broad understanding of what they teach and the students they teach. They are also expected to understand the research-theory-practice nexus and to have the inquiry and research skills to become lifelong learners who grow in their profession. But teachers today are increasingly expected to perform additional tasks, such as facilitating the development of students’ social and emotional skills, responding to students’ individual differences and working collaboratively with other teachers and parents to ensure the holistic development of students. The demands on school leaders are also significant. In many education systems, school leaders are not only expected to lead the administration and management of their school but also to create conditions that lead to improved teaching and learning. These include developing school improvement plans, encouraging teachers’ collaboration and participation in effective professional development, counselling students and parents about student progress and student orientation, and connecting the school to a larger network of schools and the local community. This is what communities expect from teachers and the question is how communities can best support their teachers to fulfil these expectations.

Teachers and school leaders are at the centre of any attempt to improve the quality of education. Decades of research have found that teachers and school leaders shape the quality of instruction, which strongly affects students’ learning and outcomes (Barber and Mourshed, 2009[1]; Darling-Hammond, 2017[2]; OECD, 2018[3]). As a result, education systems have sought how to:

-

attract high-achieving candidates into the profession

-

provide quality initial and continuous training to new recruits and in-service teachers

-

support teachers in the continuous development of their craft and spread good practices

-

foster job satisfaction and the status of the profession, with a view to retaining quality teachers and school leaders (OECD, 2005[4]).

The Teaching and Learning International Survey (TALIS) defines teachers as those who provide instruction in programmes at a given educational level as part of their regular duties in a target school. Target schools are defined as schools that comprise at least one teacher. Principals are defined as heads of target schools. In these definitions, active delivery of instruction is considered the core and common element of the mission of schools and the work of teachers, both within and across countries. Compared to the rich and animated debate on what defines the occupations of teachers and school leaders, the TALIS definitions are very simple. However, through the breadth and depth of indicators collected, TALIS aims to contribute to the debate about teaching as a profession (Guerriero, 2017[5]; Ingersoll and Collins, 2018[6]). By examining the “professionalism framework” through the lens of the indicators available in TALIS, it can help identify levers to enhance the degree of professionalism of teachers and school leaders worldwide.

TALIS defines teaching as a profession underpinned by five pillars:

-

the knowledge and skills base, which includes shared and specialised knowledge, as well as standards for access to the profession and development of specific skills through pre-service training and in-service professional development

-

the status and standing of the profession, captured through the ethical standards expected of professional workers, the intellectual and professional fulfilment of the job, and the working regulations applying to teaching (such as competitive reward structures on par with professional benchmarks and room for career progression)

-

peer control, which relies upon self-regulated and collegial professional communities that provide opportunities for collaboration and peer feedback to strengthen professional practices and the collective identity of the profession

-

responsibility and autonomy, captured through the degree of autonomy and leadership that teachers and school leaders enjoy in their daily work, to make decisions and apply expert judgement and to inform policy development at all levels of the system, so that professionalism can flourish

-

The perceived prestige and societal value of the profession.

Using these five pillars, this report takes stock of existing classifications and has adapted and expanded them to the new analytical potential of TALIS 2018 instruments. It examines not only the different attributes of professionalism, but also the policies and practices that support and enhance them. As part of the third cycle, and given the hundreds of variables collected over 48 countries – sometimes across 3 levels of education and at 3 points in time – TALIS 2018 will be released in two volumes examining these five pillars of professionalism. This first volume, Teachers and School Leaders as Lifelong Learners, explores the knowledge and skills dimension of professionalism. The second volume, Teachers and School Leaders as Valued Professionals, to be published in early 2020, will focus on status and standing, peer control, and responsibility and autonomy.

Using TALIS 2018 data, the professionalism of teachers and school leaders is measured through many different indicators. These range from fact-based indicators (teachers’ levels of education, participation in professional development, type of work contract and rates of absenteeism) to more subjective factors (sense of preparedness and self-efficacy, perceived needs for professional development, job satisfaction, and perceived levels and sources of stress). Although TALIS collects information on both teachers and school leaders, its analyses offer greater depth and a more complete picture for teachers than for school leaders.

TALIS 2018 results and policy pointers

As previously noted, this volume of the TALIS 2018 international report focuses on the first pillar of professionalism for teachers and school leaders: the dimension of knowledge and skills in their work. Any profession needs to have a specialised set of knowledge and skills that makes it distinctive and from which practitioners draw their legitimacy and prestige. This first volume shows how teachers and school principals see their practice and how they develop their knowledge and skills to help students develop the cognitive and socio-emotional skills and academic knowledge needed in today’s changing world. It examines how much the landscape of teaching has changed since the 2008 and 2013 cycles of TALIS, in terms of the profiles of teachers, school leaders and students and the climate in schools and classrooms. It also explores links between the content and features of initial teacher education and continuous professional development and individuals’ feelings of preparedness for the job, self-efficacy and job satisfaction. These analyses help to determine to what extent a strong knowledge and skills base supports the work of teachers and school leaders, as well as how and in what areas teachers and school leaders can develop further. The volume also examines teachers’ and school leaders’ perspectives on school resources issues and priority areas for intervention and additional spending. This helps give them a voice on these issues, as an important first step towards greater leadership and regulation by the profession.

This chapter presents an overview of the main findings on these issues and offers policy pointers to consider in designing teacher policies. Chapters 2 and 3 look at how teachers and principals continuously adjust their practices to changing times and how they best support students to develop cognitive and socio-emotional skills in our changing world. Chapters 4 and 5 examine support mechanisms to enhance the knowledge base of teachers and school leaders to drive the success of teaching and learning, through initial training (Chapter 4) and continuous professional development (Chapter 5).

Highlighting the connections between results on different cross-cutting issues, the summary of main findings that makes up the rest of this chapter is structured as follows:

-

Promoting quality teaching for every student examines whether teachers’ and school leaders’ work and working conditions shape environments conducive to student learning and well-being and also how to ensure quality teaching for every student.

-

Supporting the professional growth of teachers and school leaders throughout their careers analyses whether teaching is becoming increasingly professionalised in terms of knowledge and skills and how to support the professional growth of teachers and school leaders.

-

Attracting quality teachers and school leaders and monitoring workforce dynamics describes the teacher and principal workforces and suggests directions for attracting quality teachers and school leaders and monitoring workforce dynamics.

For each of these broad objectives, the chapter points out promising education policies and practices that could be considered to improve conditions for teaching and learning and professionalism for teachers and school leaders. These policy recommendations draw on findings emerging from the TALIS 2018 data or on evidence-based research. However, it is acknowledged that, as TALIS results vary across countries and economies, the proposed policy pointers may not be relevant to all education systems and should be interpreted as suggestive.

Promoting quality teaching for every student

To examine the skills of teachers, TALIS has developed indicators designed to capture what teachers do in their classrooms: how they distribute their class time on various activities; how often they use effective teaching practices; and how well they are able to implement certain practices and achieve certain goals.

Goal: Make the most of teachers’ time to support quality teaching

An important pre-condition for use of quality teaching practices is making the most of classroom time to implement them. On average across the OECD, teachers report spending 78% of classroom time on actual teaching and learning (the equivalent of 47 minutes of a 60-minute lesson), 13% of classroom time on keeping order in the classroom (the equivalent of 8 minutes) and 8% on administrative tasks (the equivalent of 5 minutes). Teachers’ reported self-efficacy is not independent of the use of class time. In most countries and economies that participate in TALIS, there is a significant inverse relationship between perceived self-efficacy in classroom management and class time spent on keeping order, although the direction of causality cannot be determined.

Some important trends in teachers’ use of time are also observed, for various time units. Overall, during a typical week, teachers report teaching a higher number of hours in 2018 than in 2013 (in about half of the countries with available data). Concomitantly, the number of hours teachers spend on planning and preparing lessons has decreased. This may not be worrisome, as long as lesson preparation has become more effective. This is made possible, for example, through the use of technology, ageing of the teacher population (lesson preparation time is typically longer for novice teachers than for more experienced teachers) or efficiencies in content (such as reusing lesson materials for different classes).

A more worrying trend is that, within single lessons, there has been an overall decline in classroom time spent on actual teaching and learning since 2008 (observed in around half of the countries). In other words, the overall proportion of lesson time efficiently used for teaching and learning has decreased over the past decade.

Policy pointer 1: Rethink teachers’ schedules

Designing and implementing effective pedagogical practices require time to prepare lessons and to try out, revise and improve specific practices. Thus, it is important for policy makers and other stakeholders to reflect on how the people, time, space and technology in education can be used most productively. This includes ensuring that teachers have enough time for activities that maximise student learning (such as lesson preparation, professional collaboration, meeting with students and parents, and participating in professional development).

Goal: Promote the use of effective teaching practices

The frequent and widespread use of high-leverage pedagogies and teaching practices is another important element of teaching quality. Among the wide range of instructional practices used by teachers in class, those aimed at enhancing classroom management and clarity of instruction are widely applied across the OECD countries and economies participating in TALIS, with at least three-fifths of teachers using them frequently. Practices involving cognitive activation (instructional activities that require students to evaluate, integrate and apply knowledge within the context of problem solving) are less widespread, with about half of teachers using most of these methods frequently across the OECD. Past OECD studies provide repeated evidence that cognitive activation practices are positively related to student learning and achievement (Echazarra et al., 2016[7]; Le Donné, Fraser and Bousquet, 2016[8]). Indeed, these practices can challenge and motivate students, and stimulate higher-order skills, such as critical thinking, problem solving and decision making. Teachers implementing these practices not only encourage students to find creative and alternative ways to solve problems, but also enable them to communicate their thinking processes and results to their peers and teachers.

Turning to a more subjective indicator of teaching quality, teachers’ reported self-efficacy, TALIS findings show that more than 80% of teachers feel confident in their capacity to teach and manage their classroom, on average across OECD countries and economies participating in TALIS. However, TALIS reveals findings corroborating a stronger difficulty for teachers in actively engaging students in learning than in managing their classroom as, for example, over 30% of teachers report low self-efficacy in motivating student learning, particularly when it comes to turning around a situation where a student shows low interest in school work.

With respect to effective use of classroom time as a third measure of teaching quality, TALIS data show that teachers tend to spend less classroom time on actual teaching and learning when teaching larger classes. Whether this suggests that resources be prioritised to better prepare and support teachers with classroom management, or to decrease class sizes, cannot be discerned from these data. Also, while TALIS data show that smaller classes tend to go along with more actual teaching and learning time, class size is no predictor for other quality indicators of teaching processes captured by TALIS, such as the use of cognitive activation practices and teachers’ reported self-efficacy in teaching.

Teachers’ practices also differ depending on the composition of the classroom they teach. In most countries and economies, when the share of gifted students in a classroom is larger and/or the proportion of low achievers is smaller, all three quality indicators of teaching processes examined (the use of cognitive activation practices, self-efficacy and the time spent on actual teaching) tend to be more prevalent, even after controlling for teachers’ characteristics.

Policy pointer 2: Support teachers in the use of effective teaching practices

Initial and continuous teacher learning that emphasises effective teaching practices could foster the use of pedagogies related to cognitive activation. Clinical experiences, where teachers can explore such strategies, could also facilitate their acquisition of related skills (Cheng, Cheng and Tang, 2010[9]). Teachers should be trained in the use of these practices, be aware of their importance, feel able to use them and enjoy the conditions to actually implement them.

Policy pointer 3: Promote small-group instruction to optimise classroom time

Education systems, as well as school leaders, should strive to give teachers greater flexibility in designing effective learning environments that optimise classroom time.

The opportunity cost of class size reductions are high and OECD education data show no evidence that reducing class size across the board has led to general improvements in outcomes. Still, there seems room for more creative solutions. For example, teachers should be encouraged and supported to set up their classroom space in a way that is conducive to more individualised and active learning approaches, splitting the room into different areas and groups, with adequate materials for students to complete tasks. Past research found that student attitudes about group-based learning improve with comfort and physical ease of communication within groups, such as small tables facing one another and facilities for easy mobility in the room (Espey, 2008[10]).

School leaders could also be given increased discretion to use human resources in more flexible ways at the school level, to enable teachers to work with smaller groups at least part of the time. An additional advantage of such an approach could be to provide an opportunity to trial new ways of working in teams with other teachers and support staff to assess the impact of such arrangements on students and teachers.

Goal: Foster openness towards innovation and effective use of ICT in teaching

The 2014 OECD report Measuring Innovation in Education: A New Perspective states that educational innovation can add value in four main areas:

-

improving learning outcomes and the quality of education

-

enhancing equity in access to and use of education, as well as equality

-

improving efficiency, minimising costs and maximising the “bang for the buck”

-

introducing the changes necessary to adapt to rapid changes in society (OECD, 2014, p. 21[11]).

A perspective of interest with regard to innovation concerns the general uptake of innovative practices by teachers and schools as core actors in educational processes. On average across the OECD countries and economies participating in TALIS, about 70% to 80% of teachers and more than 80% of school leaders view their colleagues as open to change and their schools as places that have the capacity to adopt innovative practices. However, this viewpoint is less common among young and novice teachers than among more experienced teachers. It is also less common in European countries than in other parts of the globe.

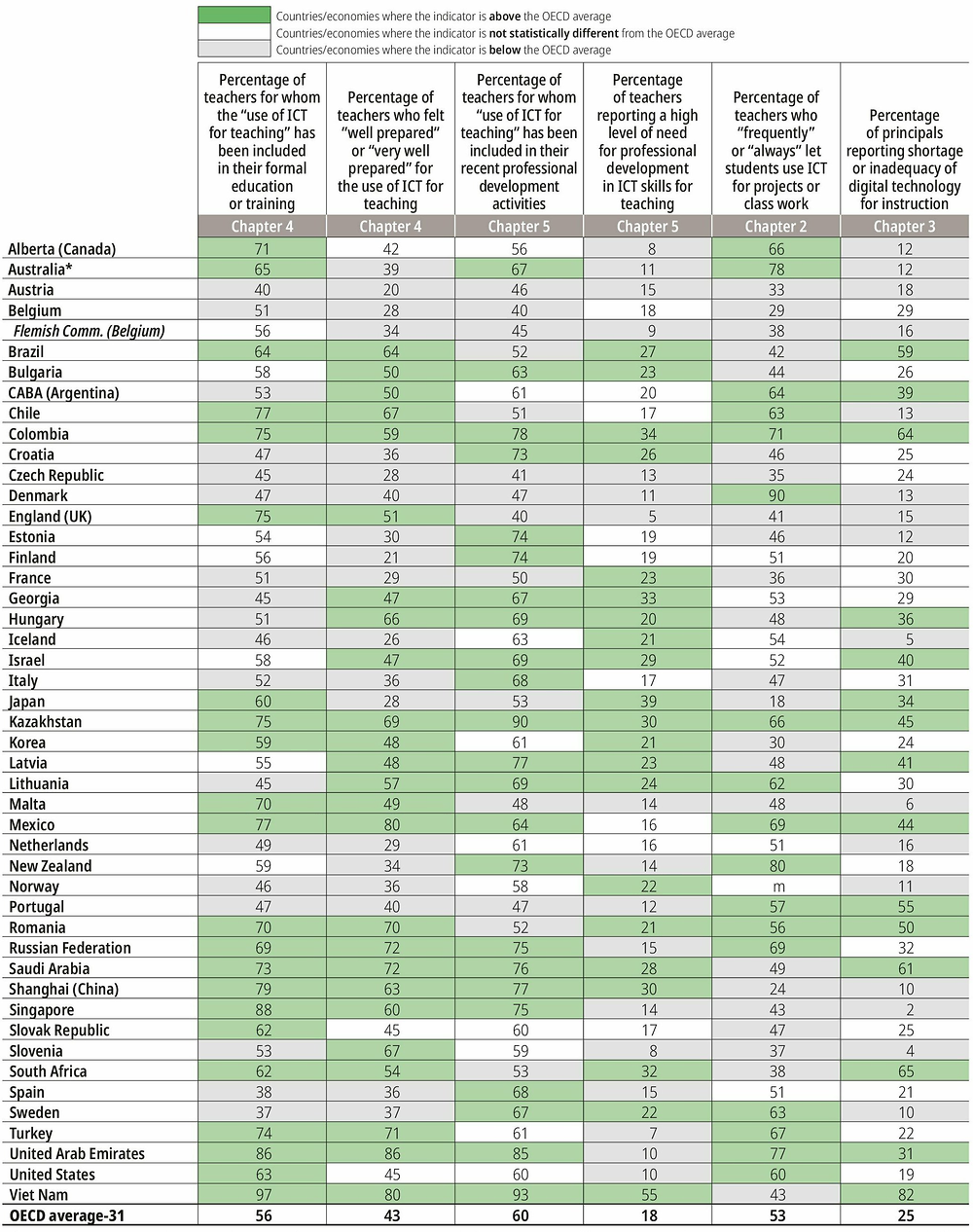

While asking teachers and school leaders about innovation-responsiveness among the staff of their school, TALIS allowed an open interpretation of the meaning of innovation. However, TALIS also collects information on the use of information and communication technology (ICT) in classrooms and schools, which can be considered an expression of innovation. ICT is also an example of innovation for which use is generally easier to monitor and measure, including through a survey like TALIS. Figure I.1.1 provides a snapshot of the use of ICT for teaching and the development of and need for related skills. The frequency with which teachers have students use ICT for projects or class work has risen in almost all countries since 2013, to a point where 53% of teachers across the OECD report frequently or always using this practice. In line with this, participation rates in professional development activities including ICT skills for teaching have increased in many countries since 2013. The rise in the use of ICT for projects or class work is not surprising, given the recognised digitalisation and spread of ICT tools in social and work activities. This rise can be explained by the dissemination of these technologies in all spheres of society and also by the renewal of the teacher workforce, with younger teachers being more familiar with these technologies.

However, TALIS data suggest that there is limited preparation and support available for teachers that could enable them to implement innovative practices in their instruction. Only 56% of teachers across the OECD received training in the use of ICT for teaching as part of their formal education or training, and only 43% of teachers felt well or very well prepared for this element when they completed their initial education or training. Moreover, about 18% of teachers across the OECD still express a high need for professional development in ICT skills for teaching. Finally, with 25% of school leaders reporting a shortage and inadequacy of digital technology for instruction as a hindrance to providing quality instruction, TALIS data suggest that teachers may be limited in their use of ICT.

Policy pointer 4: Tailor support for integrating ICT in teaching and dissemination of good practices

International surveys and studies conducted in international and national contexts highlight the importance of how ICT is used in the classroom (Fraillon et al., 2014[12]; OECD, 2015[13]). A study conducted on the TALIS 2013 dataset of Spain showed that teachers’ use of ICT in the classroom is mainly dependent not only on teacher training in ICT but also on teachers’ collaboration with other teachers and teachers’ perceived self-efficacy and beliefs about teaching, as well as (although to a lesser extent) the availability of educational software or school infrastructure (Gil-Flores, Rodríguez-Santero and Torres-Gordillo, 2017[14]).

In particular, teacher professional learning opportunities should move forward from just acquiring the skills to master certain technological competencies to finding ways to tailor technology to specific subjects and specific activities within those subjects. Rather than narrowly focusing on the tools, training on ICT skills for teaching should reflect how technology can amplify great teaching and empower teachers to become better instructors. These opportunities should focus on building teachers’ competence in dealing with technology use in the classroom.

Furthermore, the scope of ICT skills can be quite broad, encompassing issues as diverse as the mastery of online search engines, managing social media, learning coding scripts, creating multimedia platforms and building awareness of the importance of digital responsibility. As teachers access more and more training, they will be more curious and will engage in exploring new areas of technology to implement in their instruction. However, teachers’ training and motivation may not be enough to ensure effective implementation of ICT in the classroom. That also requires education systems to provide systematic and sustainable support in providing the essential resources necessary to achieve better digital competence (Krumsvik, 2008[15]).

Policy pointer 5: Build and promote professional learning communities to disseminate innovative practices

Past OECD research (Kools and Stoll, 2016[16]; Vieluf et al., 2012[17]) has pointed out the value that professional learning communities offer by constantly providing feedback to teachers, thus supporting incremental change and positively affecting instructional quality and student achievement (Bolam et al., 2005[18]; Louis and Marks, 1998[19]). This suggests that the establishment of professional learning communities could facilitate spreading and fostering the use of innovative practices. Indeed, theoretical models on the effective implementation of digital technologies have acknowledged the importance of cultivating a school community based on “sharing and caring” practices leading to digital competencies (Krumsvik, 2008[15]).

The fact that school leaders report higher levels of openness towards innovation than teachers suggests that school leaders face an important challenge in fostering a school environment open to new ideas. School leaders can help to develop a spirit of innovation-responsiveness among their staff. This can be achieved not only by encouraging staff to readily accept new ideas, but also by working with them in school-based professional learning communities to proactively identify needs for change, and by making assistance available to support teachers in the process of change.

Goal: Build the capacity of teachers and school leaders to meet the needs of diverse classrooms and schools

TALIS results show that learning environments are diverse in terms of the ethnic and cultural composition of the student body, its socio-economic diversity and student composition in terms of special needs. Reflecting on the state of classroom diversity research, a recent OECD working paper noted that: “… the debate has centred on formal education settings with researchers analysing the processes and problems related to cultural, ethnic, linguistic, religious or national diversity at school. In turn, researchers and practitioners search for solutions, frequently focusing on desired teacher qualities and competencies.” However, in relation to finding solutions, the same paper also noted that: “From [a] reflective standpoint teachers can treat diversity as an asset and a source of growth rather than a hindrance to student performance.” (Forghani-Arani, Cerna and Bannon, 2019, p. 14[20]).

TALIS 2018 pays particular attention to multicultural diversity. The integration of world economies, large-scale migration and surges in refugee flows have all contributed to forming more ethnically, culturally and linguistically diverse learning environments than in the past in the countries that have been most exposed to these phenomena. Therefore, ensuring high-quality learning experiences for this diverse student body is of particular policy priority. On average across the OECD, 17% to 30% of teachers teach in schools with a culturally or linguistically diverse student composition, depending on the criterion considered (the proportion of refugee students, of students whose first language is different from the language of instruction, or of students with a migrant background). And, as some schools are affected by only one kind of diversity, the total proportion of teachers actually working in schools with at least one element of cultural or linguistic diversity is likely higher.

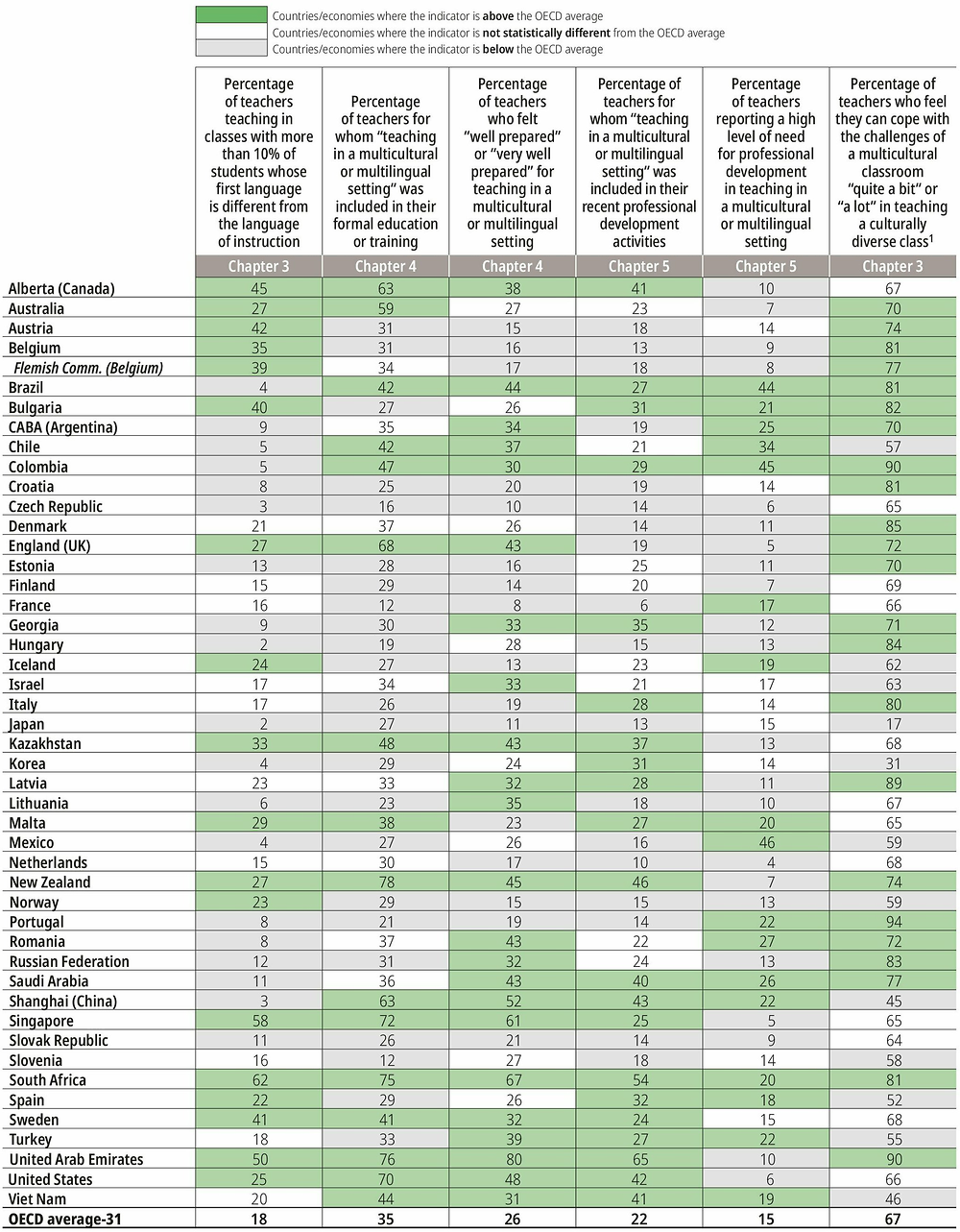

However, not many teachers are trained in teaching in such culturally or linguistically diverse classrooms. Thirty-five percent of teachers report that teaching in multicultural and multilingual settings was included in their formal teacher education or training, and 22% of teachers said it was included in their professional development activities in the 12 months prior to the survey. Furthermore, teachers who have previously taught in a classroom with students from different cultures report that they do not all feel confident in their ability to cater to the needs of diverse classrooms. When teachers completed their formal teacher education or training, only 26% of them felt well or very well prepared for teaching in a multicultural or multilingual setting. At the time of survey completion, 33% of teachers still do not feel able to cope with the challenges of a multicultural classroom, on average across the OECD. Teaching in a multicultural or multilingual setting is one of the professional development activities with the highest proportion of teachers reporting a high need for it (15%). While a high percentage of teachers (almost 70%) report high levels of self-efficacy with respect to promoting positive relationships and interactions between students from different backgrounds, fewer teachers (59%) feel able to adapt their teaching to the cultural diversity of students. This result signals that more efforts can be made by teacher education systems, but also by teachers themselves, to make use of relevant instructional tools and strategies to adapt their lessons.

Indeed, TALIS shows that, overall, teachers who were trained in the area of teaching in multicultural and multilingual settings in their initial and/or in-service training also report higher levels of self-efficacy in teaching in such settings. Figure I.1.2 provides a snapshot of teaching in multicultural and multilingual settings and the development of and needs for related skills.

Some countries experienced a rise in the concentrations of students whose first language is not the language of instruction at school, of students from socio-economically disadvantaged homes and of students with special needs. A global trend is also evident in teachers’ reported needs for training in dealing with student diversity. Between 2013 and 2018, there has been a global increase in the share of teachers expressing a high need for training in teaching in a multicultural or multilingual setting, suggesting that teachers see this as a phenomenon likely to rise in importance in the future, if it is not already a pressing issue for them.

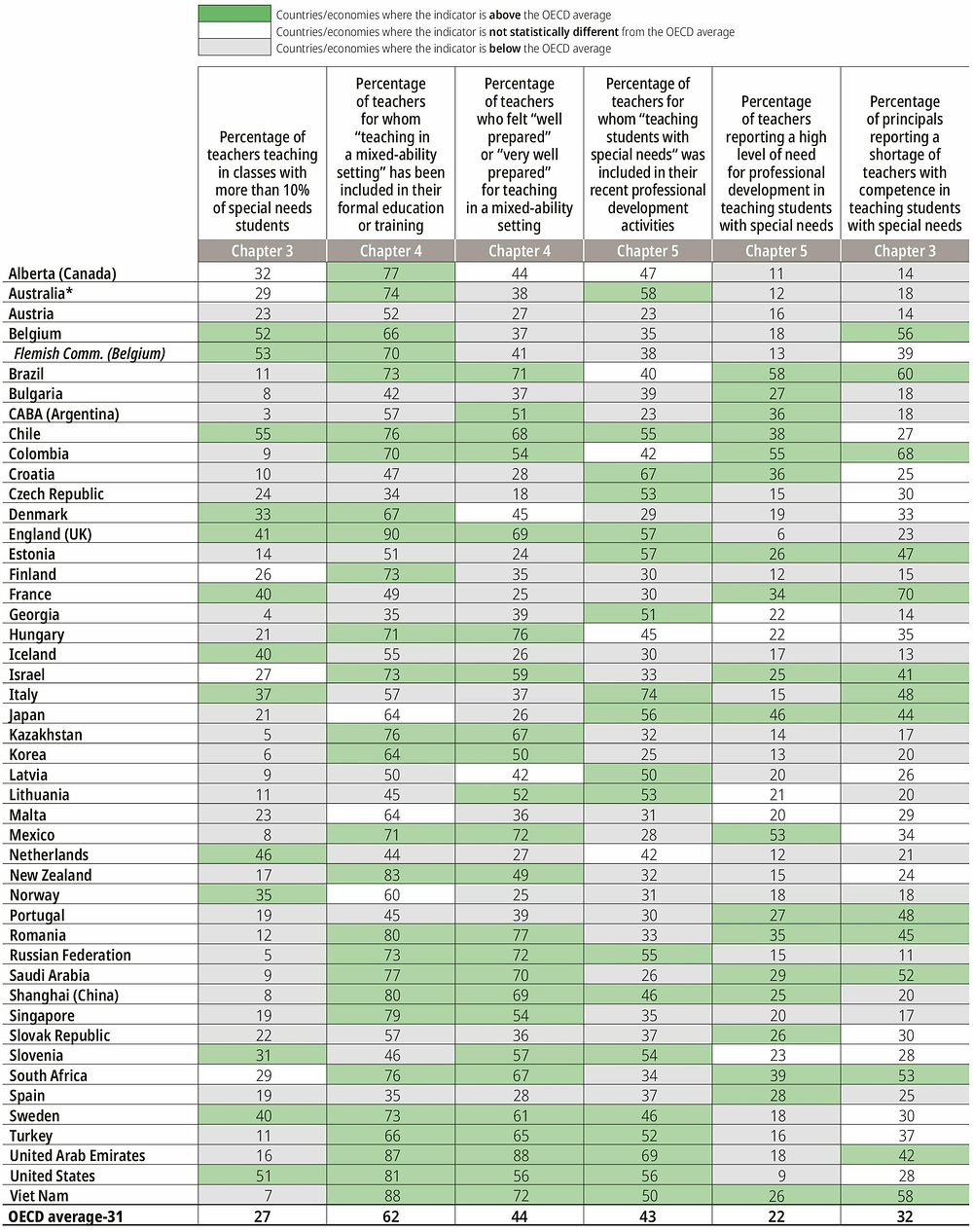

While countries differ with regard to the extent and nature of multicultural diversity, one issue that is of universal relevance relates to the inclusion of students with special needs in regular learning environments. In TALIS, special needs students are defined as “those for whom a special learning need has been formally identified because they are mentally, physically, or emotionally disadvantaged”. On average across the OECD, 27% of teachers work in schools with at least 10% of students with special needs. In some education systems, more than 50% of teachers work in schools with at least 10% of students with special needs.

TALIS does not ask teachers about the training they received in teaching special needs students as part of their initial teacher education or training. TALIS only asks whether teachers were trained in teaching in a mixed-ability setting. Although this aspect is broader and does not necessarily include teaching students with special needs, it provides some indication of whether teachers received at least some preparation in dealing with classrooms with students with diverse ability levels and, therefore, diverse learning paces and needs.

In this respect, TALIS shows that, on average across the OECD, 62% of teachers were trained as part of their formal teacher education or training to teach in mixed-ability settings, but only 44% of teachers, on average, felt prepared to teach in such settings when they finished their studies. Furthermore, although 43% of teachers, on average, participated in professional development activities including teaching students with special needs, training in teaching special needs students is the professional development topic with the highest percentage of teachers reporting a high need for it (22%). While participation in professional development on this topic has experienced one of the highest increases between 2013 and 2018, the percentage of teachers reporting a high need for it has also experienced one of the highest increases in the same period.

Finally, on average across the OECD, 32% of school principals report that delivery of quality instruction in their school is hindered by a shortage of teachers with competence in teaching students with special needs. This shortage ranks among the most frequent resource issues reported by school principals. Figure I.1.3 provides a snapshot of teaching special needs students as well as of the development of and need for related skills.

Policy pointer 6: Incorporate teaching strategies for diverse settings in the curricula of initialand continuous teacher training

Teachers need to prepare for teaching multicultural, multilingual and mixed-ability classrooms. Education systems need to have a systemic framework to prepare and support the teaching workforce to teach in diverse settings, including in diverse multicultural environments. To do so, they need to include this issue in the vision, planning and curricular design of initial training and in-service professional development.

Training systems could also offer opportunities for student teachers to study abroad as part of their formal teacher education or training. This would allow future teachers to develop intercultural and interpersonal skills useful for teaching culturally diverse classes, as indicated by past research (Rundstrom Williams, 2005[21]). One research study suggested that longer duration of study abroad had a greater impact on students than a short summer programme or a semester, in the areas of continued language use, academic attainment measures, intercultural and personal development and career choices (Dwyer, 2004[22]). A number of countries in Europe have adopted policies to hire teachers from diverse backgrounds and short-term preparation programmes for migrant teachers joining the workforce so that the teaching workforce can be more heterogeneous and reflect the diversity of the student body (Cerna et al., 2019[23]). These fast-track programmes can enable newly arrived teachers to learn about the pedagogical practices specific to the host countries, such as teacher-student interactions, classroom routines and traditions, etc. Teacher training programmes for diverse classrooms should include pedagogical approaches for second-language learning and support strategies to help students become socially integrated in diverse settings (Cerna et al., 2019[23]). These learning opportunities have been introduced by many countries in the form of elective courses and modules in their initial teacher education programmes. Opportunities that are particularly strong include practical training, such as cultural immersion programmes, to allow teachers to build intercultural competencies (Cerna et al., 2019[23]).

Going beyond training opportunities, school communities should also play an active role in preparing teachers to work in diverse environments. Schools should take into account teachers’ abilities and preparedness to teach in diverse environments when allocating teachers to specific classrooms and should team up teachers with more and less experience in this area to learn from one another.

Policy pointer 7: Implement school policies and practices to make the most of diversity

Countries and economies also need to equip school leaders and grant them enough autonomy to design and implement school-level policies and practices capable of supporting the learning of all students, irrespective of their abilities, learning needs, and social or cultural origins. These policies and practices can include information sessions for students about ethnic and cultural discrimination and how to deal with it, as well as meetings with teachers to discuss how to integrate global issues throughout the curriculum. For countries and economies with a stronger tradition of promoting multiculturalism, school leaders can consider organising multicultural events or supporting activities that encourage students to express diverse cultural identities and celebrate the richness of diversity.

Policy pointer 8: Reinforce the provision, support and training for teaching special needs students

Education systems should develop strategic policy actions to improve the quality and number of teachers equipped to teach special needs students, as they are increasingly enrolled in regular schools and classes.

As a first step, it would be important for education systems to invest in the detection and diagnosis of special needs students. What teachers perceive as behavioural issues (e.g. misbehaviour, low performance) could have other explanations (e.g. undiagnosed special needs). Misdiagnosis is costly for students, teachers and education systems as a whole. So an increased emphasis on training teachers to detect students who need to be directed to specialists for proper diagnosis would be desirable. In addition, education systems need to ensure that all students have access to professional diagnosis. This can be achieved by developing professional capacity for diagnosis and detection within schools or, in systems where private providers are responsible for such diagnosis, by ensuring that financial constraints do not impede the diagnosis of socio-economically disadvantaged students.

A recent OECD Education Working Paper analysed professional development needs in special education, using TALIS 2013 data. It suggested that education systems may need to pursue several means to address the shortage of teachers with skills for teaching special needs students. These include recruiting more teachers with the skills to teach special needs students, targeting training in this area and addressing over-reliance on part-time, non-permanent positions for teachers who work with higher shares of student with special needs. Such measures are a way to build continuity in instruction for special needs students and increased capacity for their teachers (Cooc, 2018[24]).

High-quality teacher training for special needs education should be provided to all teacher candidates as well as to in-service teachers. To encourage teachers to participate, specific competencies related to teaching in inclusive classrooms should be included in national standards frameworks. However, as education systems may not make such training available for all immediately, priority should be given to teachers teaching higher shares of special needs students, with a view to maximising impact in the short term (Cooc, 2018[24]).

The high need for training reported by teachers as observed in TALIS could also signal that these teachers’ schools do not have the necessary resources in terms of infrastructure or educational resources to support teachers serving special needs students. A special financial subsidy for mainstream schools that serve special needs students (e.g. for recruiting teacher aides) could improve the situation of both human and educational resources.

Goal: Foster a school and classroom climate conducive to student learning and well-being

An important issue for policy makers, principals, teachers and parents alike is to ensure that schools are safe environments, that classroom climate is conducive to student learning, and that relationships among students and with school staff are conducive to their development and well-being. Fortunately, on average across the OECD, schools in 2018 are, for the most part, immune from weekly or daily school safety incidents and, thus, provide students with safe learning environments.

However, one issue stands out in the reports of school principals on school safety. Reports of regular incidents related to intimidation or bullying among students are significantly higher than for the other school safety incidents, occurring at least weekly in 14% of schools, on average across the OECD. In TALIS 2018, a new item asks principals about the frequency of a student or parent/guardian reporting the posting of hurtful information on the Internet about students (akin to cyberbullying). In 2013, those types of incidents would likely have been included under the bullying item. Therefore, change in bullying over time needs to be interpreted cautiously, taking into account not only bullying, but also posting of hurtful information about students on the Internet (in 2018). Contrasting daily or weekly incidents of bullying (in 2013) with daily or weekly incidents of either bullying or the posting of hurtful information on the Internet (in 2018) reveals that seven countries and economies have experienced a reduction in the frequency of this phenomenon, as reported by principals. But in five education systems, their frequency has increased, according to principals. This calls for close monitoring and specific action.

At the classroom level, TALIS 2018 results suggest that teachers perceive relations between themselves and their students as very positive. On average across OECD countries and economies participating in TALIS, 95% of teachers concur that teachers and students usually get on well with one another – up from the percentage reported in 2008 for most countries with available data.1 Change in student-teacher relations over time also reveals that teachers’ beliefs in the importance of student well-being has progressed in the vast majority of countries since 2008.

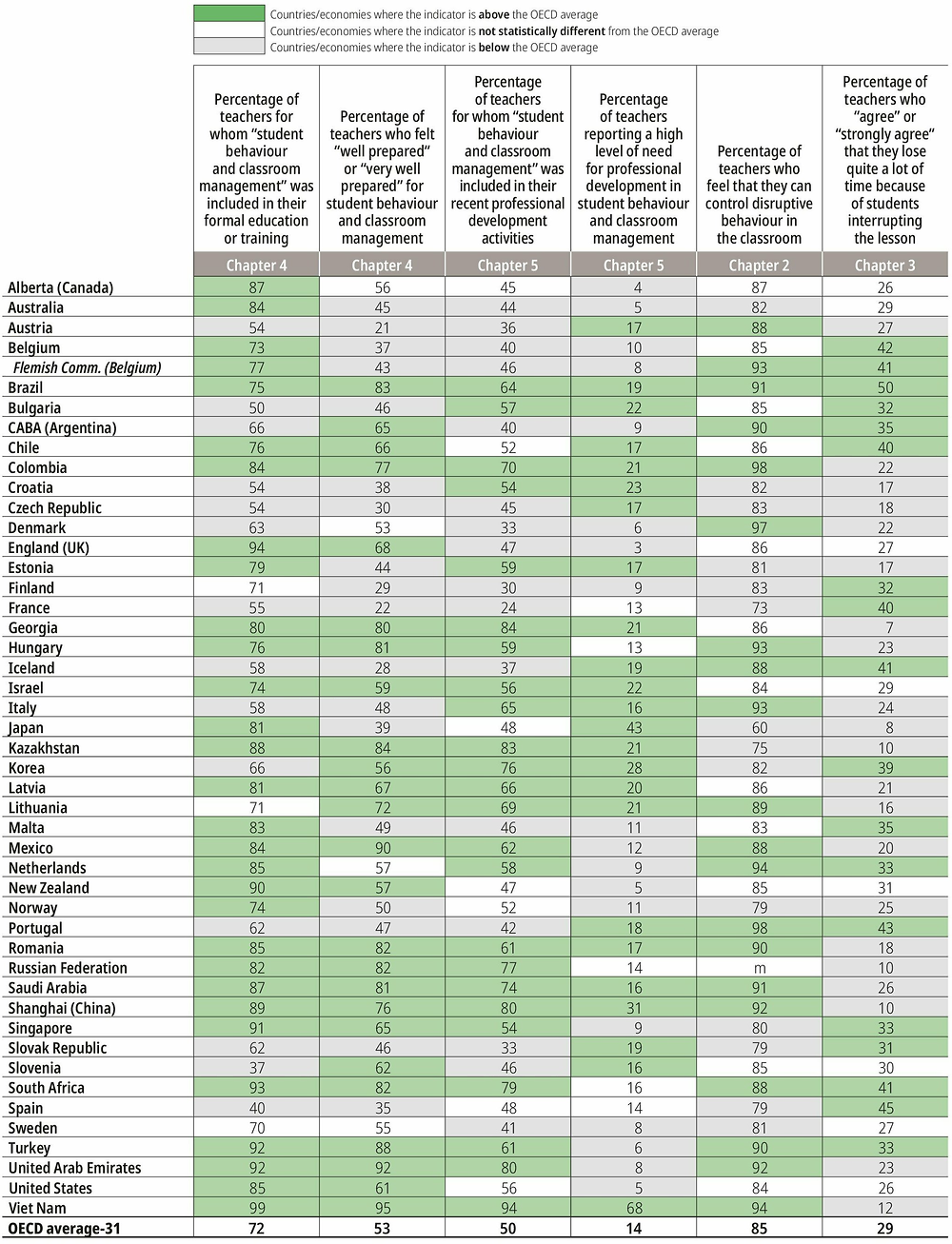

However, quite a few teachers face classroom disciplinary issues. More specifically, 29% of teachers, on average across the OECD, report that they “lose quite a lot of time because of students interrupting the lesson”, and a significant share of teachers do not feel they can resolve this situation. TALIS data makes it possible to examine the extent to which teachers are supported in this aspect of teaching. With regard to formal education and training, 72% of teachers, on average across the OECD, report having received initial training in student behaviour and classroom management. That is low compared to the share of teachers having received training in subject content, pedagogy and classroom practice. In addition, only 53% of teachers report that they felt prepared for this aspect of their work when they completed their initial education or training.

Across the OECD, 50% of teachers report that they received training in student behaviour and classroom management as a part of their recent professional development activities. While 85% of teachers feel that they can control disruptive behaviour in the classroom, a significant share of teachers across the OECD (14%) express a high need for professional development in student behaviour and classroom management. The problem of managing disciplinary issues is particularly pressing and an impediment to instructional quality in schools. Figure I.1.4 provides a snapshot of teachers’ training, self-efficacy and challenges with regard to student behaviour and classroom management.

Policy pointer 9: Implement system and school-level policies and practices to combat all forms of bullying

Teachers and school staff can play a crucial role in preventing bullying by working closely with students to build strong and healthy interpersonal relationships. A review of 21 studies on the effectiveness of policy intervention for school bullying found that such policies might be effective at reducing bullying if their content is based on evidence and sound theory and if they are implemented with a high level of fidelity (Hall, 2017[25]). School-level disciplinary policies could focus on monitoring and supervision of all students, communication and partnership among teachers, parent-teacher meetings and classroom management. Furthermore, information sharing and supportive communication is important in helping students cope with the harmful effects of being bullied. School programmes should educate students on measures to take when witnessing bullying. This can help schools to promptly identify incidents of bullying and develop suitable responses. Finally, the inclusion of social-emotional learning in regular classroom hours can improve the interpersonal and intrapersonal skills of students and build an overall healthy environment in the school.

As part of an education system’s role in providing welcoming, respectful and safe learning environments, system-level policies could establish a code of conduct for students to combat bullying as a national priority and also develop monitoring frameworks. This can ensure that all schools are held accountable for implementing measures against bullying and can encourage viewing this issue as a shared responsibility.

Policy pointer 10: Reinforce the awareness of teachers and school leaders of student well-being for effective learning

Training programmes for teachers and school leaders should be updated with the most recent trends in bullying incidents to better prepare schools for the emerging challenges related to student safety. Training programmes and other professional learning opportunities, such as coaching activities and professional networks, should allow educators to communicate with one another and focus on the different contexts and situations where bullying incidents take place, both within and outside the school environment, in the real world and on line. Support from behavioural experts can help teachers to identify victims of bullying and intimidation, and training from counsellors can enable teachers to be better prepared to intervene and support all students who are victims of bullying.

Goal: Make the most of school leaders’ time to foster instructional leadership

The quality of conditions for teaching and learning also hinges on the time and efforts school leaders dedicate to supporting teachers and providing instructional leadership and related activities in their school. A research study on use of time by school leaders in an American school district (Miami-Dade County Public Schools) found that time spent by school leaders on instructional programme activities is positively associated with the staff’s perceptions of the school’s educational environment and teachers’ satisfaction with teaching in general (Horng, Klasik and Loeb, 2010[26]). The same study suggested that organisational management activities are also central to instructional leadership defined broadly. Another research study based on longitudinal data found that, while principals’ time spent broadly on instructional functions does not lead to increased student achievement, time spent on specific instructional investments, such as teacher coaching, evaluation and developing the school’s educational programme, positively influence learning gains (Grissom, Loeb and Master, 2013[27]). Neither of the two studies found positive effects related to the time spent by school leaders on classroom visits and observations.

Despite the benefits of instructional leadership and related activities emerging from research, TALIS findings suggest that school leaders are limited in the time and resources needed to express instructional leadership. On average across the OECD, school principals spend 16% of their working time on curriculum and teaching-related tasks and meetings (e.g. developing a school curriculum, teaching, observing their teachers’ classes, mentoring teachers, designing and organising professional development activities for teachers or being involved in student evaluation). This makes it the third most time-consuming task of principals, after administrative tasks and meetings (30% of principals’ working time) and leadership tasks and meetings (21%). Yet, this is not enough in the views of school leaders themselves. One of the most common resource issues hindering quality instruction reported by school leaders in participating countries and economies is the shortage or inadequacy of time for instructional leadership.

Fortunately, to the extent that solutions can be found to alleviate their administrative workload, school leaders do seem willing to engage more in instructional leadership activities. Principals report a great interest in improving both their school organisation and the practices of their teachers, with more than 70% of them attending training to become an instructional and/or pedagogical leader. Furthermore, the areas in which large shares of principals report a high need for professional development are in developing collaboration among teachers (26% of principals across the OECD) and training in using data to improve the quality of the school (24%).

Policy pointer 11: Rethink the role, responsibilities and schedules of school leaders

Education systems need to find ways to strengthen instructional leadership in the field of curriculum and teaching within schools. There are several possible avenues for this, each with different implications for the role, responsibilities and schedules of school leaders.

One approach is to strengthen school leaders in their role as instructional leaders. To achieve this, an important precondition is to ensure that school leaders have adequate time and support to develop their leadership in the field of curriculum and teaching.

Policy pointer 12: Encourage instructional leadership through clear professional standards for school leaders

A number of countries have introduced professional standards for teachers as a tool to make knowledge and competence requirements explicit. Likewise, defining and establishing clear professional standards for principals that stress the importance of and expectations for instructional leadership can be a powerful tool to stimulate a dialogue within the profession on the importance of this function, as well as an incentive for school leaders to engage more in these activities.

There is an additional advantage of professional standards and guidelines for instructional leadership. By articulating the base level of what school leaders need to know and the capacity they need to acquire, these instruments can also serve as a tool to guide school principals in the type of in-service training they need to lead their schools. This can also encourage them to reorganise their time to shift emphasis towards instructional leadership activities.

Policy pointer 13: Build capacity for instructional leadership and recruit instructional leaders among teachers

In light of the importance of instructional leadership to support the professional growth of teachers, training in instructional leadership should be viewed as a prerequisite for school leaders prior to taking up their duties. Furthermore, the training of school leaders in this area should be seen as an ongoing process, with principals also offered opportunities for professional development in instructional leadership after taking up their duties in order to consolidate and further develop these skills. Such professional development can take many forms, as discussed in the next section. Echoing the needs of teachers, school principals could also be given more opportunities to participate in communities of practice and collaborative enquiry with their peers from other schools in order to improve their instructional leadership.

But providing school leaders with pre-service and in-service training in instructional leadership is no guarantee that they will engage more in these activities. TALIS results show that time seems to be a constraint. To free up some time for school leaders to devote to tasks related to curriculum and teaching, one option could be for education systems or school management boards to create intermediate management roles or to devolve some management and administrative responsibilities to other teachers interested in building leadership capacity. For example, teachers showing exceptional leadership should find rewarding career tracks that allow them to pursue attractive careers, including school leadership paths, that foster their administrative and instructional leadership skills. Such an approach would allow school leaders more time to engage in curriculum and teaching activities, and it would also provide paths for teachers to grow and strengthen their professionalism.

Supporting the professional growth of teachers and school leaders throughouttheir careers

Professional knowledge and skills are defined as a common set of knowledge and skills that are acknowledged through high-level qualifications and constitute the core elements of membership in the profession. Teachers and school leaders require advanced or graduate-level education and specialised knowledge and skills that are typically acquired through participation in initial training programmes and continuous in-service professional development. As a result, the development of knowledge and skills takes place across diverse stages of the teachers’ and school leaders’ professional pathways (OECD, 2016[28]).

Goal: Provide high-quality initial education or training

To foster lifelong improvement of the knowledge and skills base of teachers and school leaders, it is imperative for education systems to provide pertinent training and facilitate access to it. Indeed, in relation to the attributes of professions, Ingersoll and Collins state that “… professional work involves highly complex sets of skills, intellectual functioning and knowledge that are not easily acquired and not widely held.” and that “… the underlying and most important quality distinguishing professions from other kinds of occupations is the degree of expertise and complexity involved in the work itself.” (Ingersoll and Collins, 2018, p. 202[6]).

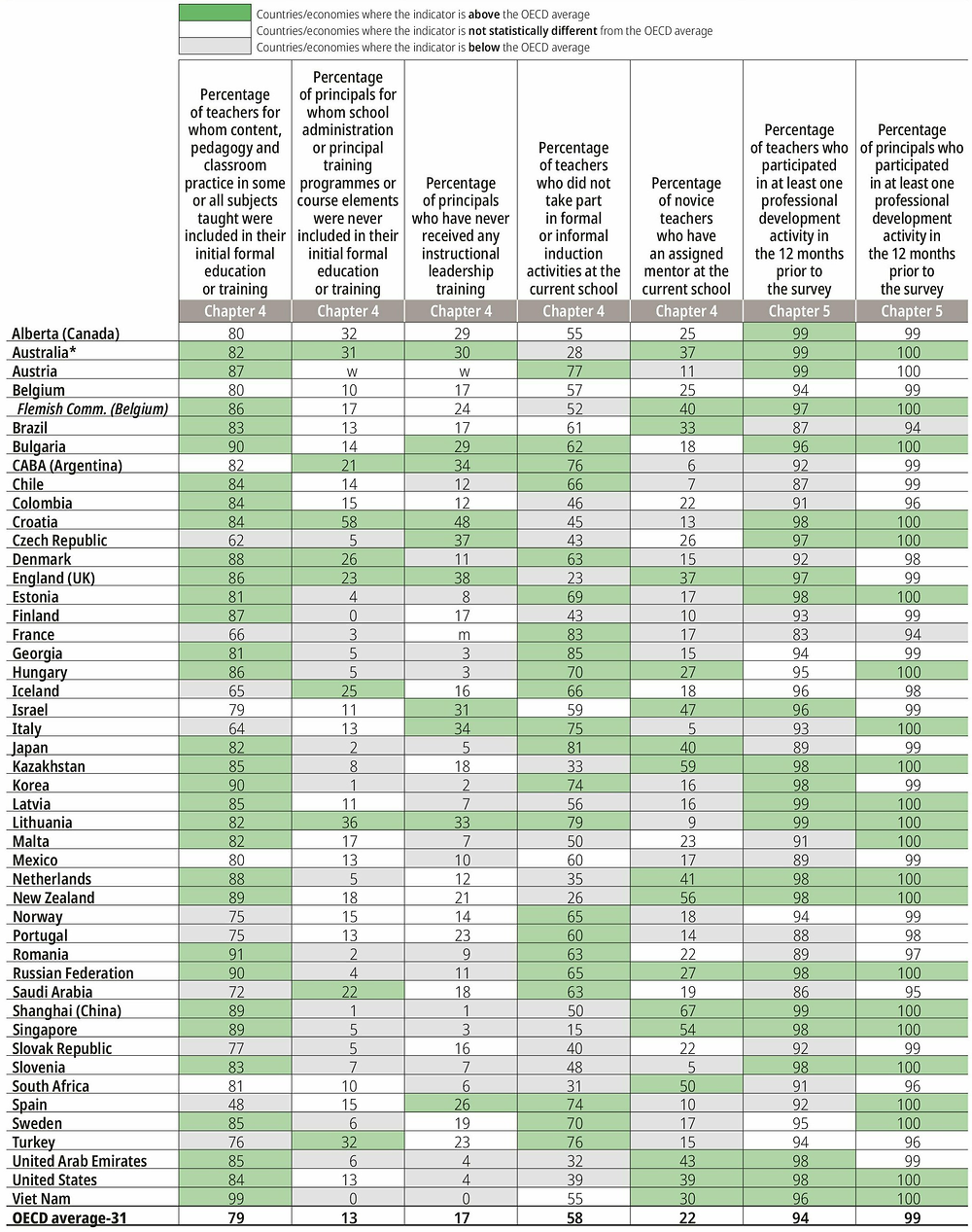

In this context, an essential aspect of strengthening professionalism throughout the education system is to ensure that teachers and school leaders start off in their jobs with a solid knowledge base. To examine the importance of credentials in the jobs of teachers and school leaders, TALIS has developed a rich set of indicators to describe the type and content of their initial training. Figure I.1.5 provides a snapshot of lifelong training for teachers and school leaders that includes key indicators on initial training.

The typical level of education attained by teachers varies slightly across countries. On average across OECD countries and economies, 50% of teachers report a bachelor’s degree or equivalent as their highest educational attainment. Another, smaller share of teachers (44%) report a master’s degree or equivalent, including stronger specialisation and more complex content than a bachelor’s degree, as their highest educational attainment. Across the countries and economies with available data, most teachers completed a regular concurrent (rather than consecutive) teacher education or training programme, which grants future teachers a single credential for studies in subject-matter content, pedagogy and other courses in education during the first period of post-secondary education. In some systems, a significant share of teachers did not complete any formal teacher education or only completed fast-track or specialised education or training programmes.

Policy pointer 14: Offer alternative paths into the profession while preserving quality training

Faced with teacher shortages and the prospect of mass retirements in some countries, education systems are increasingly required to provide multiple ways into the profession to satisfy the demand for teachers, including fast-track or alternative routes. In doing so, they need to establish mechanisms to ensure that all teachers start off their teaching career with adequate and quality training.

At the school-level, educational institutions and schools should ensure that, regardless of local circumstances, all teachers are equipped with sufficient training in the content and pedagogy of the subjects they teach.

At the system level, a recent OECD review of initial teacher preparation identified a series of system-level policies and initiatives to ensure quality of initial training. These include:

-

establishment of rigorous accreditation institutions monitoring the work of teacher education providers (possibly including “fast-track” providers)

-

teacher evaluation conducted at some point of the teachers’ initial training (at entry, during the mid-years of training, and/or towards the end of their training programme)

-

establishing teaching standards that define precisely what is required and expected of teachers when they enter training and when they are ready to start teaching (OECD, 2019[29]).

Goal: Provide novice teachers with fulfilling working conditions and tailor-made support

Among all the steps of a teacher’s career pathway, the early career years are those that deserve the greatest support and attention to ensure effectiveness and well-being. New teacher graduates mostly enter the profession with some degree of training through initial teacher education programmes (such as graduate degrees, certification courses or other pathways of entry), as well as some practical training opportunities. However, additional support activities and structures in the initial years of teaching can help teachers to cope with the challenges they face, as well as to maintain their motivation levels. Both are critical to making them competent and effective, and also to convincing them to remain in the profession (OECD, 2019[29]). Given the impact of teachers on student learning, the effectiveness of teachers new to the profession is an important policy issue. An effective education system requires all teachers, including new teachers, to provide high-quality instruction to students (Jensen et al., 2012[30]).

TALIS 2018 data shows that teachers in their early career years tend to work in more challenging schools that have higher concentrations of students from socio-economically disadvantaged homes and students with a migrant background. In addition, on average across the OECD, 22% of novice teachers report that they would like to change to another school if that were possible.

Furthermore, novice teachers feel less confident in their ability to teach, particularly in their classroom management skills and their capacity to use a wide range of effective instructional practices. This result could be linked to the amount of time they have available for planning and teaching their classes, as novice teachers spend less time in actual teaching than more experienced teachers. With regard to workload, after adjusting for full-time or part-time work, novice teachers work as many hours per week in total as teachers with more than five years of experience, on average across the OECD. These findings highlight the importance of providing adequate mechanisms to support novice teachers.

Induction to teaching is a key component of the teaching profession. According to Ingersoll and Collins (Ingersoll and Collins, 2018[6]), the objective of induction is to “… aid new practitioners in adjusting to the environment, to familiarize them with the concrete realities of their jobs, to socialize them to professional norms, and also to provide a second opportunity to filter out those with substandard levels of skill and knowledge.” (p. 203[6]). TALIS has developed a large set of indicators describing the support received by novice teachers, school provisions in terms of induction and mentoring programmes and the actual participation of new teachers in these programmes.

Despite empirical evidence showing that teachers’ participation in induction and mentoring is beneficial to student learning (Glazerman et al., 2010[31]; Helms-Lorenz, Slof and van de Grift, 2013[32]; Rockoff, 2008[33]), these programmes and activities cannot be considered commonplace in TALIS countries and economies. On average across the OECD, 58% of teachers report not having participated in any formal or informal induction activity at their current school (Figure I.1.5). Novice teachers are more likely to participate in both formal and informal induction activities at their current school than more experienced teachers. While school principals generally consider mentoring to be important for teachers’ work and students’ performance, only 22% of novice teachers have an assigned mentor, on average across the OECD (Figure I.1.5).

Policy pointer 15: Review the distribution of novice teachers to schools

Teacher shortage is one of the most pressing problems faced by current education systems. Although there are many reasons for teacher shortages, one of the most salient factors is attrition in the early years of teaching. For example, in Australia, 30% to 50% of all teachers leave the profession in the first five years. In the United Kingdom, attrition rates are even higher, with 50% of teachers leaving the profession within five years after graduation (den Brok, Wubbels and van Tartwijk, 2017[34]).

TALIS data show that teachers in their early career years tend to work in more challenging schools. One solution to reduce attrition in the early years is, thus, to review how novice teachers are distributed across schools, with a view to assigning them to less challenging working environments in their first placements, and to encourage more experienced teachers to work in disadvantaged schools, to reduce the need to staff them with less experienced teachers. An additional advantage of such an approach would be potential effects in fostering equity, as students in challenging schools would be taught by more experienced teachers. Indeed, evidence has shown that students coming from a disadvantaged background benefit the most under effective teachers. This reduces the achievement gap with students from more privileged backgrounds (Sanders and Rivers, 1996[35]).

In countries with more centralised teacher allocation and compensation mechanisms, a possibility would be to create a fixed-term first assignment for recent graduates of initial teacher education programmes, using a separate algorithm that would only assign them to a subset of schools considered less challenging. A complementary approach would be to create salary incentives for experienced teachers who are working in less challenging schools to accept teaching positions in more challenging schools. This would encourage applications from experienced teachers and reduce the need to fill these positions with novice teachers. The goal of this approach would be to change mindsets, so that teaching in more difficult schools would be seen as a prestigious stage in a teacher’s professional growth and career trajectory rather than a necessary first ordeal, and would be recognised accordingly in financial terms. However, several education systems have introduced financial incentives to attract teachers into schools with more challenging circumstances, with mixed results and little evidence of the effect of such measures on teacher allocation across schools (OECD, 2018[3]). One possible explanation for this could be that financial incentives have to be significant to be effective.

Funding mechanisms that consider the socio-economic context of students and schools and, in the case of more decentralised systems, greater school autonomy and increased budgets for selecting and managing teachers, could help attract effective teachers to schools with higher concentrations of socio-economically disadvantaged students (OECD, 2018[3]). But financial and non-financial incentives might also be needed to better align teaching resources with needs.

When assignment of novice teachers to a challenging school is unavoidable, school leaders have a role to play in easing the transition of recent graduates to the profession, e.g. providing the induction and coaching they need, allocating them to less challenging classes, making sure that their teaching assignments allow some degree of efficiency gain in lesson preparation (e.g. having several groups of the same grade) or pairing them with more experienced teachers in joint teaching arrangements.

Policy pointer 16: Design effective context-based induction and mentoring activities

Induction programmes should be designed to aid new practitioners, or practitioners who are new in their roles, to adjust to their working environment and become acquainted with the realities of their jobs, as well as to avoid early attrition from the profession. A crucial element in planning induction opportunities for teachers is to allow mentors to reduce their teaching load, so that they can balance their working time between lesson preparation and actual teaching and can meet the demands of participating in induction. A possible approach could be to provide financial support to schools (in decentralised systems) or additional teacher allocations (in centralised systems) to enable recruitment of novice teachers on a full-time basis but with a reduced teaching load that would increase incrementally over the first years in the profession as they gain experience.

Policy pointer 17: Give school leaders an active role in the development and promotion of induction and mentoring opportunities

It would also be important for the extent and intensity of induction support developed by school leaders for new teachers to be tailored to their school’s context and student composition. Induction programmes could include team-teaching opportunities, as they can foster greater collaboration among teachers within schools and help new teachers to learn from experienced teachers who are more familiar with the specific school context.

At the same time, school leaders need to encourage and support teachers to take an active part in induction and mentoring activities. To guarantee participation in induction, it could be useful to allocate a certain number of hours of paid non-teaching time dedicated to induction or mentoring activities within teachers’ weekly or monthly schedules. School leaders could identify which teachers are best suited to act as mentors for the new teachers at their school and whether they should be selected on the basis of the subject they teach, their years of experience in the school or their experience in the profession. Finally, education systems could design and establish career paths encouraging teachers to become mentors, through incentives such as salary bonuses or promotion to a mentor-teacher role, recognising their expertise and contribution.

Goal: Link initial teacher education with continuous professional development

A crucial component of professionalism among teachers and schools leaders is their participation in ongoing in-service professional development (Guerriero, 2017[5]). “The assumption is that achieving a professional-level mastery of complex skills and knowledge is a prolonged and continuous process and, moreover, that professionals must continually update their skills, as the body of technology, skill, and knowledge advances.” (Ingersoll and Collins, 2018, p. 205[6]). Under this approach, teachers and school leaders are considered lifelong learners, with different needs for training throughout their career path. Education systems and training institutions, at both national and local levels, need to accurately identify these needs and secure access to relevant training for teachers and school leaders.

First and foremost, TALIS findings support the idea that receiving pre-service training and/or in-service training in a given area is associated with a higher perceived level of self-efficacy in this area by teachers, and/or a higher propensity to use related practices.

In light of the value of pre-service and in-service training for teachers’ perceived self-efficacy and use of teaching practices, a key task when considering teachers as lifelong learners is to ensure adequate linkages between the content of teachers’ initial training and that of their continuous professional development. In this way, all aspects of a teacher’s work will covered at some point and consolidated and expanded upon over time (OECD, 2019[29]).

Across the OECD, about 80% of teachers report that their formal education or training included content, pedagogy and classroom practice in some or all of the subjects they teach (Figure I.1.5). Similarly, training in subject matter knowledge and understanding of the subject field and pedagogical competencies are the most frequent types of professional development attended by teachers. Other elements often included in teachers’ formal education and in their continuous professional development relate to student behaviour and classroom management (across OECD countries and economies, 72% of teachers had such content covered for their initial training and 50% for continuous professional development [Figure I.1.4]); teaching cross-curricular skills (65% for initial training and 48% for professional development [Tables I.4.13 and I.5.18]); and use of ICT for teaching (56% for initial training and 60% for professional development [(Figure I.1.1]).

These results reflect that there are certain areas that still emerge as very common topics for in-service training, despite being covered in the formal teacher education or training of a majority of countries and economies participating in TALIS. Conversely, teaching in multicultural or multilingual settings is more rarely included in both initial training (35% of teachers across the OECD) and continuous professional development (22%) (Figure I.1.2). However, it is important to acknowledge that there is large cross-country variation with respect to training and professional development on teaching in multicultural or multilingual settings. For initial training, 12% to 78% of teachers report inclusion of this topic in their initial training, while it ranges from 6% to 65% of teachers for continuous professional development.

TALIS findings show that school leaders have attained, on average, a higher level of education than teachers. However, just a little more than half of school leaders actually completed a programme preparing them for their job before they took up duties. Indeed, 63% of school leaders hold a master’s degree or equivalent, on average across the OECD (Table I.4.24). But only 54% of them had completed a programme or course in school administration or principal training before taking up their position as principal, with the same share having completed an instructional leadership training programme or course (Table I.4.28). In contrast, across the OECD, 99% of principals participated in at least one type of professional development activity in the 12 months prior to the survey (Figure I.1.5). Principals also tend to participate in more diverse training formats than teachers. On average across the OECD, 73% of principals report participating in a course/seminar on instructional leadership in the 12 months prior to the survey (Table I.5.10). These findings suggest that principals may compensate for a possible lack of initial training on leadership-specific skills with more intensive participation in continuous professional development activities after taking up their duties.

Policy pointer 18: Ensure links between the content of initial teacher education and professional development training

Countries and economies need to ensure that the curricula of initial education and in-service professional development are consistent, well-connected and complementary. This is not always easy. The first reason for this is the limited feedback loops between schools and initial teacher education (OECD, 2019[29]). But it is also a result of the “stickiness (resilience) of the implicit know-how of teachers” (Moreno, 2007[36]), whereby teachers may consider what they have learned as part of their initial education and during their first years of experience as a fixed or set reference.

Continuous professional development activities need to take into account and build upon the knowledge and skills that teachers and school leaders acquired as part of their initial education or training. Thus, curricula need to be designed in a concerted manner for pre-service and in-service training.2 The major challenge for establishing this continuum between initial teacher education and in-service training is articulating each stage in a cohesive manner. This may require systematic alignment across each education system, establishing consultations, feedback loops and, if these responsibilities are shared across several entities, collaboration between the different actors and stakeholders of initial teacher preparation and professional development systems.

Policy pointer 19: Foster pre-service preparation of school leaders

There is considerable room to improve the professionalism of school leaders by creating pre-service programmes that help them develop the leadership skills they need to effectively engage in the various practices associated with school success. These include developing and conveying a shared vision, cultivating shared practices, leading teams towards school goals, instructional improvement, developing organisational capacity, and managing change (Darling-Hammond et al., 2007[37]). TALIS results show that participation in professional development is the most common route principals use to develop their skills.

Education systems could provide prospective school leaders with more opportunities to develop leadership skills prior to their appointment as school principals. This could be done either through specific training modules that prospective school principals would need to undertake or validate ahead of taking up leadership duties (e.g. by making such training a prerequisite for any appointment to a leadership position) or through the creation of intermediate leadership roles for experienced teachers interested in growing into leadership roles (e.g. based on Australia’s department faculty head model).3

Policy pointer 20: Develop mentoring programmes for school leaders

Besides pre-service preparation, education systems could also provide school leaders with other relevant opportunities for in-service training upon appointment. A possible way to achieve this would be to create professional networks of principals. In such networks, more experienced principals mentor those who are newly appointed, and school leaders can learn from one another and share good practices to address common challenges. Several studies have reported on the advantages and disadvantages of mentoring for new school principals. These are helpful to guide the design of such programmes (Daresh, 2004[38]; Southworth, 1995[39]). If mentors are well paired to mentees and have good knowledge of the needs of new school leaders, mentoring for new school principals should, indeed, facilitate peer support and enable newcomers to make the necessary role and occupational identity changes. Such programmes would benefit mentors as well as mentees, provided both engage in the learning process. The process should be particularly beneficial if it encourages reflective practice rather than passing on outdated role assumptions.

Goal: Provide high-quality continuous professional development

Looking at TALIS 2018 data, it is clear that annual participation in professional development is almost universal among both teachers and school leaders. This is evidence of the level of professionalisation of their jobs. On average across the OECD, 94% of teachers and nearly 100% of principals participated in at least one type of professional development in the 12 months prior to the survey (Figure I.1.5).

TALIS data shows that teachers attended about four different types of continuous professional development activity in the 12 months prior to the survey. The most attended forms of professional development are courses or seminars attended in person (76% of teachers across the OECD) and reading professional literature (72%) (Table I.5.7). However, participation is lower for more collaborative forms of professional development: only 44% of teachers participated in training based on peer/selfobservation and coaching, learning and networking. Overall, on average across the OECD, 82% of teachers report that the professional development activities they participated in had an impact on their work (Table I.5.15), while regression results show that a positive impact of the training is highly correlated with higher levels of job satisfaction and/or self-efficacy in most TALIS countries and economies (Tables I.5.19 and I.5.14).

With respect to the forms of professional development that are most useful, TALIS asked teachers to describe the characteristics of the training they deemed impactful. While they were not directly asked why this training was impactful, teachers’ descriptions of impactful professional development can provide insights on the characteristics and design features of training that has spurred changes in teachers’ practice. This information, combined with insights from research, can feed into the design of these programmes. According to teachers’ reports, impactful professional development programmes are based on strong subject and curriculum content and involve collaborative approaches to instruction, as well as the incorporation of active learning. Evidence from the previous cycle of TALIS indicates that teachers who had positive views of their self-efficacy and job satisfaction are more likely to engage in more school-embedded professional development activities (Opfer, 2016[40]).

Research evidence is, to a large extent, consistent with TALIS findings. It has shown that even though traditional training in the form of courses or seminars can be an effective tool (Hoban and Erickson, 2004[41]), school-embedded professional development, such as peer-learning opportunities, tends to have a larger impact on teaching practices4 and can significantly reduce the cost of training (Kraft, Blazar and Hogan, 2018[42]; Opfer, 2016[40]). In particular, a recent meta-analysis review of 60 studies that employed causal research designs, found that teacher coaching (i.e. a school-embedded approach to in-service training) had a positive impact on both teachers’ instruction and students’ achievement (Kraft, Blazar and Hogan, 2018[42]).5 It is also noteworthy that the findings of Opfer (2016[40]) are based on TALIS 2013 data.

Policy pointer 21: Promote school-based, collaborative and active professional development responding to local needsand adapted to school-specific contexts

TALIS data and research findings concur to suggest that school-based and collaborative professional development could have the potential for more impactful effects on teaching practices and student achievement (Borko, 2004[43]; Opfer, 2016[40]). Yet, TALIS 2018 data also show a comparatively low percentage of teachers participating in collaborative training activities, such as peer/self-observation and coaching-based learning, suggesting that this is an area where there is room for improvement.