Chapter 2. Effectiveness of flood governance

This chapter looks at the Principles related to effectiveness of water governance. It brings attention to flood governance in association with the importance of defining and implementing clear institutional roles and responsibilities, policy coherence, the need for appropriate capacities to implement and manage floods at appropriate scales. It applies the Checklist and makes observations and analysis of each Principle, it points to particular areas of improvement and it points to examples of ways forward. The chapter contains case study examples highlighting flood governance under different contexts.

Principles 1 to 4 provide a framework for understanding whether the institutions and policies concerned with flood governance are performing effectively. Effectiveness of water governance relates to the contribution of governance to define clear sustainable water policy goals and targets at different levels of government and to implement those policy goals to meet expected objectives or targets.

The four Principles deal explicitly with institutional frameworks linked to policy development and implementation, such as co-ordination functions of water management and use. They include managing water across various scales (from local to transboundary) and various sectors, such as energy, agriculture, environment and industry, to ensure co-ordinated decision making and policy coherence. Finally, they also draw attention to developing the appropriate level of capacity to respond to various water challenges (see Figure 1.1).

The system used should enable institutions to realise their mandates (for example related to regulation of land and water use) and ensure that policies are implemented according to intentions for improved flood governance. Simply put, the performance of the governance system has a critical effect on for example, how well early-warning systems work, and to what extent flood control and mitigation measures achieve the desired results, as well as rapid-response mechanisms when flooding occurs.

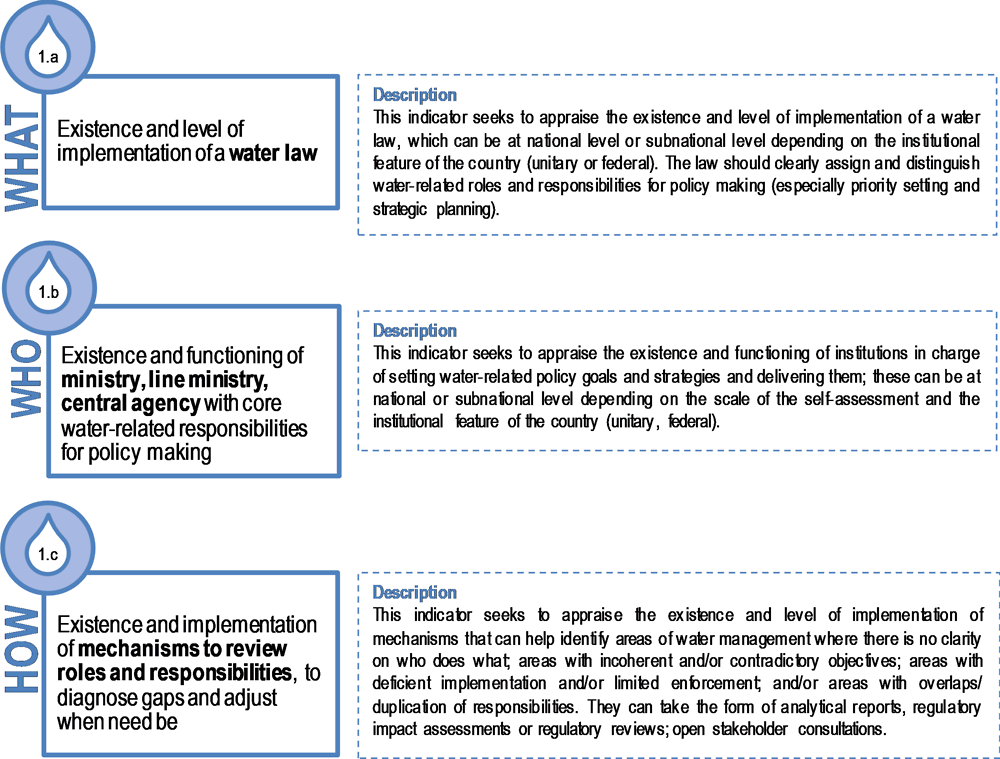

Principle 1: Roles and responsibilities

Principle 1. Clearly allocate and distinguish roles and responsibilities for water policy making, policy implementation, operational management and regulation, and encourage co-ordination across the responsible authorities.

To that effect, legal and institutional frameworks should:

a) Specify how roles and responsibilities for water are to be allocated, across all levels of government and water-related institutions for:

-

Policy making, especially priority setting and strategic planning;

-

Policy implementation, especially financing and budgeting, data and information, stakeholder engagement, capacity development and evaluation;

-

Operational management, especially service delivery, infrastructure operation and investment; and

-

Regulation and enforcement, especially tariff setting, standards, licensing, monitoring and supervision, control and audit, and conflict management;

b) Help identify and address gaps, overlaps and conflicts of interest through effective co-ordination at and across all levels of government.

Observations

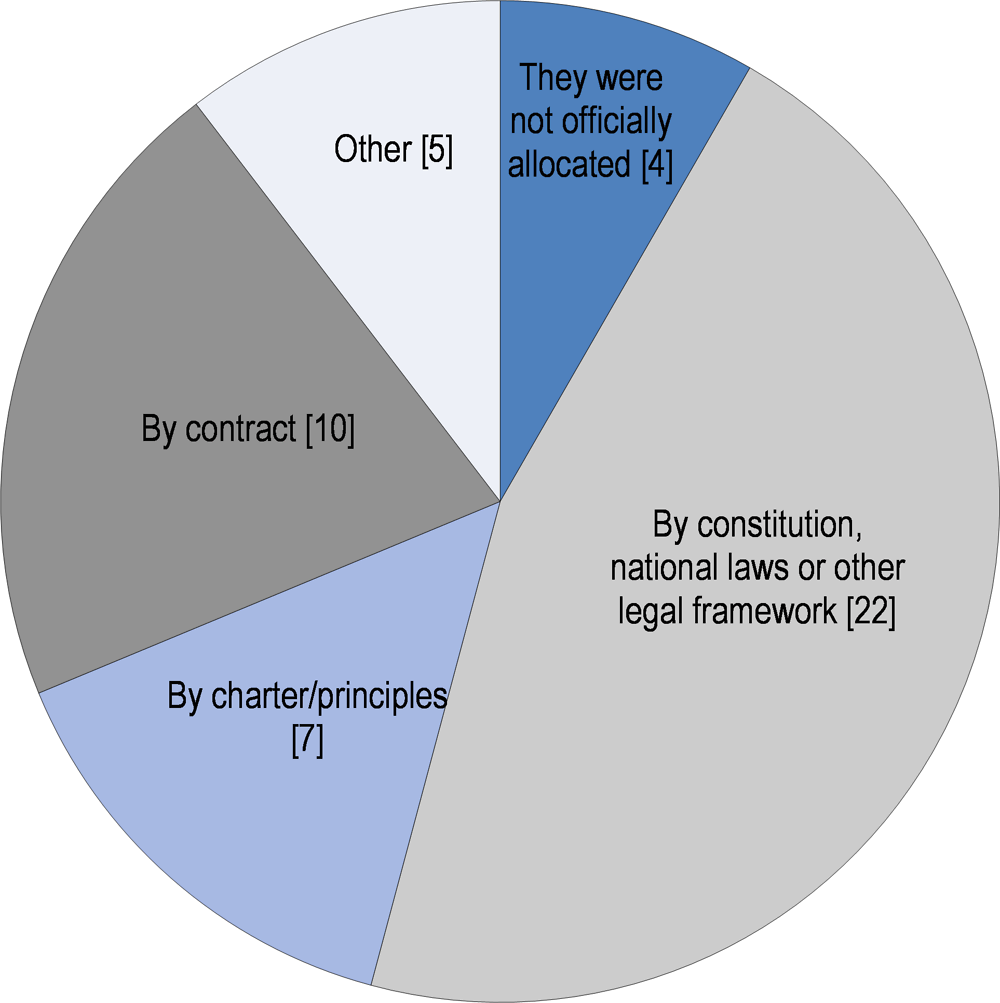

Various roles and responsibilities are involved in water management at large, and flood management in particular. In many OECD and non-OECD countries, the allocation of roles and responsibilities in flood management is widely distributed across several scales, ranging from national to sub-national and basin levels, as well as across sectors. Responsibilities are typically defined and allocated by the Constitution or by national law (accounting for 22 out of the 27 case studies collected). In other instances, modalities for defining the allocation of roles and responsibilities are set by contract, as evidenced by 10 of the case studies collected or by a charter, for seven cases. The case studies also illustrate situations where roles and responsibilities are not officially allocated but rather defined according to informal agreements, such as in the framework of partnerships (Figure 2). Unclear roles and responsibilities can lead to conflict between institutions, as occurred with the delta governance in Bangladesh. In France (Flood Prevention Action Programmes), the problem concerns discrepancies between the technical expertise and knowledge that undermines co-ordination across authorities.

Allocation of roles and responsibilities may be regularly reviewed to adapt to changing circumstances and to ensure they are appropriate. The European Floods Directive requires that Flood Risk Management Plans be reviewed every six years. The review and/or update of flood-risk management policies and plans can be a good occasion to take stock of and adjust the allocation of roles and responsibilities, as illustrated by 19 case studies. Other means include the organisation of internal meetings as part of projects and citizen platforms, such as observatories or public meetings. They may also be the prerogative of the national regulator or a parliamentary commission. Often, several of these processes are used simultaneously to revise the allocation of roles and responsibilities. For 19 out of 27 case studies collected, more than one review mechanism is used. The design and implementation of Flood Risk Management Strategies (FRMSs) often take place in a fragmented setting. To varying degrees, countries have allocated the increasingly complex and resource-intensive competences to lower levels of government, including management of floods. This is not always compatible with the unpredictable and inadequate revenues of the institutions concerned (i.e. funding gaps) and tends to result in less coordination between multiple authorities.

-

In France, for example, decentralisation has resulted increasingly in flood management policies at the local level. While the national government still have flood management programmes and controls policy and law making and procedures, the responsibility for flood infrastructure has devolved in part to the municipal level. Current territorial reforms in France have reallocated competences to the inter-municipal and metropolitan levels, for example for the maintenance of hydraulic structures used in flood prevention. However, French state services continue to manage flood and coastal risk prevention plans (Plans de Prévention des Risques d’Inondation, Plans de Prévention des Risques Littoraux).

-

Such multi-level coordination challenges are also seen in England, where the Floods and Water Management Act of 2010 attempted to tackle the issue by making it a statutory duty for national agencies and local authorities to co-operate and align their strategies (Hegger et al., 2013).

-

The division of responsibility is also a significant issue in Australia. The state governments are constitutionally responsible for land and water management, and by extension, flood management. However, Australian state governments, as in many other places of the world, face challenges in how to balance priorities in planning portfolios of economic growth and flood management risks. The responsibility of state governments for flood prevention and mitigation does not always match with financial responsibilities once flooding occurs. The consequences of flooding are for the most part paid for by a different level of government: the federal level (see Productivity Commission, 2014; Abel et al., 2011). A risk with this set up is that it can dis-incentivise state governments to make some of the required investments in flood management.

Institutional fragmentation can affect the effectiveness of flood-risk governance arrangements. Two-thirds of the case studies collected assess this impact using methods such as interviews, stakeholder consultation and stakeholder mappings or parliamentary reviews. In these cases, the assessment revealed that fragmentation can spark conflicts among stakeholders in charge of flood management (as illustrated in 13 case studies); generate negative environmental impacts (in 8 case studies); or lead to an uneven distribution of resources and unclear accountability lines (seen in 8 case studies also). Experience in other case studies attests to multi-level challenges that can derive from institutional fragmentation, including inconsistencies between national and local goals/strategies, overlapping or conflicting policies, and the heavy workload assumed by lower levels of government for handling flood management.

Dispersion across agencies is not inherently negative. It may also imply what is called “polycentricity” (Cairney, 2012), where responsibilities are not all concentrated in a single place. It is essential to assess carefully whether dispersed decision making is positive and desired, or negative and unwanted. This implies looking at co-ordination mechanisms among responsible authorities and stages of flood management and their effectiveness. In the United States, for example, the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) is responsible for “co-ordinating government-wide relief efforts. It is designed to bring an orderly and systemic means of federal natural disaster assistance for state and local governments in carrying out their responsibilities to aid citizens” (FEMA, 2016).

Various mechanisms are used to address the negative effects of institutional fragmentation. The majority of case studies collected illustrate that organisations and tools that bridge knowledge development and decision-making processes are most often used. They typically include research institutes, interactive maps and simulation models. Other typical mechanisms for tackling overlaps or conflicts of interest are vertical and horizontal co-ordination mechanisms, such as conferences that gather local and sub-national players in flood governance, and the use of co-ordinating actors (as in 17 case studies). Information and knowledge also help to co-ordinate roles and responsibilities, such as shared database and information systems and platforms through which stakeholders can create collective knowledge (as in 14 case studies). Inclusive decision-making processes are key for co-ordinating various flood management actors, interests and conflicts. For instance, Alsace-Moselle Water and Sanitation Union (Syndicat des Eaux et d l’Assainissement) in France has deployed an adaptive governance model to combat the challenges of fragmentation (OECD, 2018a). It consists of allocating roles and responsibilities at the lowest appropriate level for the topic concerned. This is done through the SDEA’s Thematic Commissions, which provide an opportunity for members to make proposals on the projects that SDEA is developing.

While monitoring the effectiveness, efficiency and inclusiveness of co-ordination mechanisms is current practice, it is not yet mainstreamed in flood-risk governance arrangements. Less than half of the collected case studies reported assessing the strength of their co-ordination tools. Those that do rarely use the same approach: some rely on indicators and regular monitoring (in two case studies), parliamentary reviews (1 case), research projects (1 case), while others carry out project implementation reviews (3 cases) and subsequent evaluations (2 cases).

Areas for improvement

As the observations show, the water sector is associated to high levels of territorial and institutional fragmentation of actors and lack of policy coherence (policy gap), and thus to deep complexity, provided that it faces overlaps. For each of the five stages of flood management1 (see definitions in Annex C of the Checklist), there is a diversity of responsible stakeholders at various scales. They can be responsible for policy making (e.g. defining flood-policy directions), policy implementation (e.g. financing and budgeting, capacity development, evaluation), operational management (e.g. running warning systems, owning and maintaining flood-risk management assets), and regulation and enforcement (e.g. land use in floodplains, the EU Floods Directive and standards and licensing issues). The lack of co-ordination mechanisms across multiple actors can hinder effective policy design and implementation for flood management (e.g. delays, high transaction costs, patchy information, etc.). In the case of flood management in the city of Granada, Spain, there are too many institutions involved, which ends up dissipating responsibility and leadership and affects the decision-making processes. There is an inherent potential for conflicts when the allocation of roles and responsibilities across policy areas and between levels of government is unclear.

Ways forward

In addition to the division of responsibilities over multiple levels, the distribution of responsibility over sectors is relevant (e.g. water system management, disaster management, spatial planning) (see Principle 3). A clear definition and allocation of roles and responsibilities in flood management, combined with effective coordination mechanisms are thus essential to diagnose inconsistencies and redundancies, to avoid grey areas, and to ensure the effectiveness of the water policy cycle. It can also serve to mobilise sufficient and stable finance for flood management. Furthermore, catchment authorities (where they exist) and the increasing autonomy of lower levels of governments need to be granted the financial support and capacity to carry out flood functions. Closing the knowledge and expertise gap may facilitate collaboration amongst authorities. Co-operation in the form of partnerships is required between levels of government and basin levels, as well as across sectors, to meet flood challenges. The case studies also show that more than one co-ordination mechanism is often needed, and that co-ordination is mainly achieved through a mix of instruments, both formal (co-ordinating bodies, contractual arrangements) and informal (bridging concepts such as multi-layered safety, etc.).

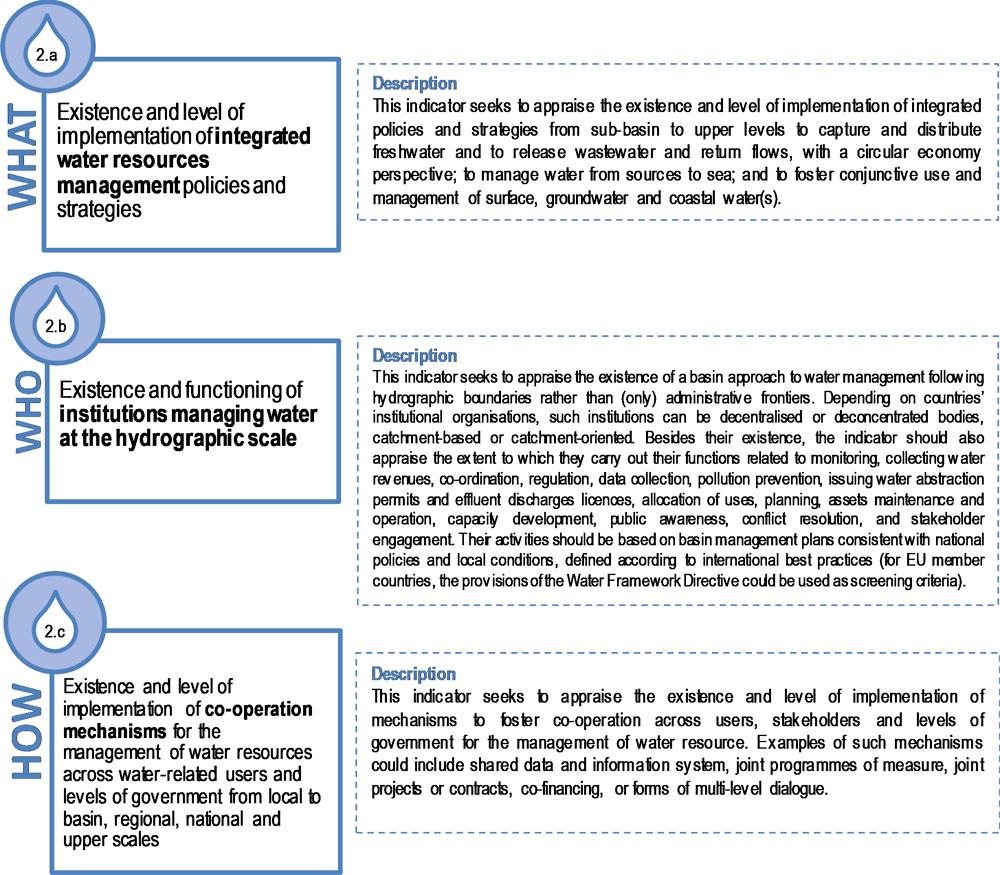

Principle 2: Appropriate scales within basin systems

Principle 2. Manage water at the appropriate scale(s) within integrated basin governance systems to reflect local conditions, and encourage co-ordination between the different scales.

To that effect, water management practices and tools should:

-

a) Respond to long-term environmental, economic and social objectives, with a view to making the best use of water resources, through risk prevention and integrated water resources management;

-

b) Encourage a sound hydrological cycle management from capture and distribution of freshwater to the release of wastewater and return flows;

-

c) Promote adaptive and mitigation strategies, action programmes and measures based on clear and coherent mandates, through effective basin management plans that are consistent with national policies and local conditions;

-

d) Promote multi-level co-operation among users, stakeholders and levels of government for the management of water resources; and,

-

e) Enhance riparian co-operation on the use of transboundary freshwater resources.

Observations

Water issues, including floods, cut across administrative boundaries both in their ecological and their political dimensions. The relevant scale for flood management depends on the area considered as a unit of management, which may vary from transboundary to city levels:

-

In the case of transboundary basins, various governments may be involved in flood management. Both the European Flood Directive and the Water Framework Directive recommend co-operation among neighbours in order to produce one single international Flood Risk Management Plan (Article 8.2) covering the entire transboundary river basin.

-

The Danube Flood Risk Management Plan is an exemplary transboundary initiative connecting different places. It was produced by the International Commission for the Protection of the Danube River (ICPDR), adopted in December 2015 and endorsed by Danube Ministers in February 2016 (ICPDR, 2015). The plan can be considered a major riparian co-operation mechanism on flood management at the basin-wide scale. Similar progress has been achieved in other transboundary river basin commissions in Europe, such as on the Rhine and Elbe rivers. Other transboundary initiatives include bilateral agreements, such as one for crisis management established after the 1997 flood on the Odra river basin shared between the Czech Republic, Poland and Germany. Similarly, bilateral agreements between the Slovak Republic and its neighbours define management steps in the case of critical hydrological situations.

-

Another example of linkages across scales but also of policies across levels is the Rhine flood-risk management plan, co-ordinated through the International Commission for the Protection of the Rhine (ICPR), created in 1950. In particular, co-ordinated measures implemented since 1995 and the drafting of the corresponding balances every five years have proved to be successful. The first Flood Risk Management Plan concerns the period 2015 to 2021 and will be assessed and eventually updated after six years. In the future, a digital instrument developed in 2015 should help ICPR determine the reduction of flood risks and the effects of measures when assessing the implementation of the flood-risk management plans in the International River Basin District Rhine. The initiative has also connected people, since public participation was key in the drafting of the plan.

-

Many other co-operation mechanisms are in place for transboundary flood management. The EU Common Implementation Strategy provides a platform to agree on views for implementation of both the European Flood Directive and the Water Framework Directive through the subsidiarity principle. It concerns the eight river commissions within ICPDR countries including the Danube and the Rhine.

-

-

National river basins or sub-basins, which are basins falling entirely within the boundary of a given country, are the primary scales considered by the European Flood Directive and the Water Framework Directive for the management of flood risk. Catchment-based governance, in theory, offers decision makers more flood-risk management (FRM) options compared to decision making on a smaller scale (Dieperink et al., 2013). For instance, it is relevant for flood forecasting and warning systems to be set up along the whole river. Catchment management organisations can also offer a platform for exchanging ideas and experiences on spatial planning, allocation politics or flood defence infrastructure construction. However, it is also worth noting that catchment approaches often fail to mesh with existing administrative boundaries.

-

In addition, the national scale often plays an essential role in flood governance. Governments set out FRMSs and are involved in the funding of flood-related measures. Moreover, since cultures of risk, administrative structures and dominant approaches to flood risks vary within countries, local initiatives should be consistent and co-ordinated with national frameworks. In Belgium, England and the Netherlands, some good practices were found (e.g. Delta Programme and Room for the River in the Netherlands; the co-ordinating role of the environment agency in England, river committees in Wallonia, co-ordination and stimulation by the Flemish Environment Agency (Vlaamse Milieumaatschappij)).

-

Finally, in many countries, crisis management, public information about floods and spatial planning are all managed at the city scale. In France, for instance, the recent territorial reform gave new competences on flood management to metropolitan areas and inter-municipal authorities, thus re-enforcing flood management at the city level. On the other hand, as is the case in Poland, shifting responsibilities to the municipal level without adequate resources can cause tensions or even backfire. In addition, responsibilities for public risk awareness and spatial planning are distributed at different scales: municipal, departmental, regional and national.

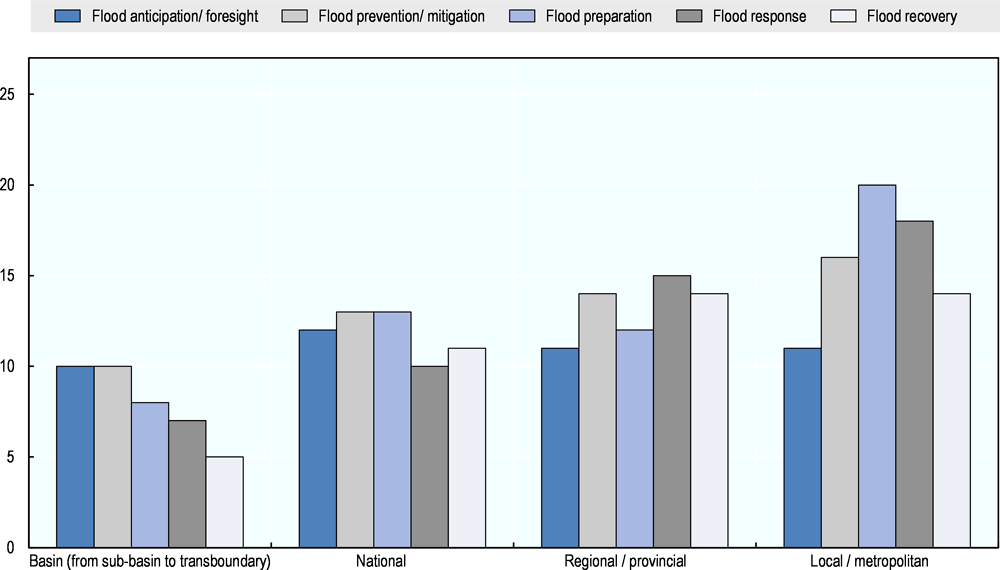

The relevant scale for flood management can also depend on the flood management function(s) under consideration. The collected case studies illustrate that in a given flood governance setting, different functions are managed at different scale. Figure 3 shows that while in a nearly equal number of cases, flood anticipation and foresight are managed at the national (for 12 case studies) or sub-national (either regional/provincial or local/metropolitan) levels (for 11 cases), flood prevention/mitigation, flood preparation and flood response are functions primarily managed at the local/metropolitan level (for 16, 20 and 18 cases respectively). Lastly, flood recovery is most often managed at sub-national level (either regional/provincial or local/metropolitan).

A number of challenges regarding flood management lie in aligning approaches at various scales. How to achieve a basin approach when governments are simultaneously devolving responsibilities to the local or city levels? How to ensure that local solutions, aiming to get rid of excess water as soon as possible, do not harm neighbouring communities? In many instances, vertical co-ordination is hampered by conflicting agendas, priorities and interests (as noted in 19 case studies), capacities and resources across scales (illustrated in 14 case studies). Challenges can also be the result of the legal allocation of roles and responsibilities or inconsistent budgeting, procurement and regulatory processes across levels of governance.

In the Australian context, flood mitigation planning and implementation are funded through state competitive grants processes, requiring local resources. Flood management is devolved to municipal levels, and usually only extends to city boundaries when preparing flood studies. Hence, flood management cannot be described as operating on a “basin” scale. Catchment management authorities, in states that have them, have limited legislative power to manage flooding and thus limited resources for it. Municipal government resources and skills to carry out flood management functions can also be a limiting factor and subject to competing local demands. Australia's National Strategy for Disaster Resilience acknowledges the increasing severity and regularity of disasters in Australia and the need for a coordinated, cooperative national effort to enhance Australia's capacity to withstand and recover from emergencies and disasters. With a view to clarify responsibilities, enhance policy coherence and consistency across the country in the way flood risk information was collected and made available to the public, the federal government initiated the Natural Disaster Insurance Review in 2011. As a response to its findings, a National Flood Risk Information Project was established that for instance delivered a portal on Australian Flood Risk Information. It aims to enable flood information, currently held by different sources, to be accessible from a single online location. The portal includes a database of flood study information and metadata.

A menu of options exists for multi-level co-ordination mechanisms. These mechanisms are used more or less regularly, depending on the scale. At the local and basin levels, responses involve enhanced engagement in flood-related decisions, while at the national level, vertical and horizontal mechanisms stand out. For instance, participatory processes are common practice at the local and metropolitan level in the case studies, together with joint programmes of measures, co-financing arrangements and joint projects or contracts. At the national level, the use of shared data and information systems is more widespread, as are inter-governmental dialogues, while at the basin level, the river basin committees and other participatory processes tend to be the preferred options. As a result of these co-ordination mechanisms, more than half of the case studies report having flood-risk management plans that are aligned with national policies and/or locally adapted to local conditions. The Netherlands’ national policy and flexible local implementation approach is a good example of resolution between geographical scales. At the international level, co-ordination is also essential, in particular across basins. The International River Protection Commissions for the Danube and Rhine rivers (ICPDR and ICPR respectively) were set up to encourage transboundary basin-wide management and enhance co-ordination at the river basin scale, building on existing national administrative arrangements and in line with the river basin management approach dictated by the EU Water Framework Directive.

Areas to improve

Further efforts are needed to align the administrative boundaries of municipalities, regions and states to hydrological imperatives, and thus reduce the administrative gap. The blurred allocation of roles and responsibilities, coupled with limited co-ordination across scales and levels of government, often leads to contradictory flood management strategies. For instance, an adequate alignment between local initiatives and national frameworks was lacking in Sweden. Besides, the issue of scale touches upon conflicts and the lack of connectivity between spatially dislocated communities in upper storage and lower impacted catchment, which is a key challenge for the Eddleston Water Project in Scotland.

The basin level is one important level at which linkages between water and land need to be managed, particularly when it comes to flood planning. Land, whether private or public, can be very challenging when managing floods, given that private property rights can be highly controversial in a context of increasing climate-driven flooding. This raises questions such as: at what scales should land and water linkages be managed? who should pay to protect private property? Who is in charge of compensating the destruction of land that is suffering devaluation? (McCarthy et al., 2018). In England, managing floods in the public space and reducing the risk of flooding at a property level has been a key challenge for the Herne Hill and Dulwich Flood Alleviation Scheme.

Ways forward

There is no unique or agreed solution on how to align approaches at the various scales. Equal attention needs to be paid to the trade-offs that such co-ordination efforts imply, since they involve time and institutional effort, and can generate multiple types of costs. Managing trade-offs related to fairness and equity in flood management is key to ensure that general and specific interests are heard. In the case of flood management, assessing the hydrological and geographical logic is fundamental to addressing the linkages between urban, rural and watersheds. Addressing the scale can also help manage other multi-level dynamics inherent in flood management, in particular linkages and co-ordination between water and land management. Involving landowners is just as important as haggling amongst administrative bodies to find potential solutions and mechanisms to mitigate and prevent floods.

Ensuring that flood management is being handled at the right scale requires clear roles and responsibilities, as well as adequate resources and skills to carry out their functions. Devolution of flood management at appropriate scales needs to address such co-ordination issues. In this sense, it is important to acknowledge that the institutional setting is not only defined at the national level, but in many cases can be related to transboundary water entities (Menard et al., 2018). Mechanisms and incentives for co-ordination among riparian states are important when it comes to transboundary flood governance, since they can build on existing national administrative structures. Transboundary cooperation presents opportunities for riparian States to identify shared interests and to develop actions for mutual benefits. For cooperation to take place political will is needed. Sometimes existence of an agreement between riparian states does not certify always a real cooperation in the whole basin.

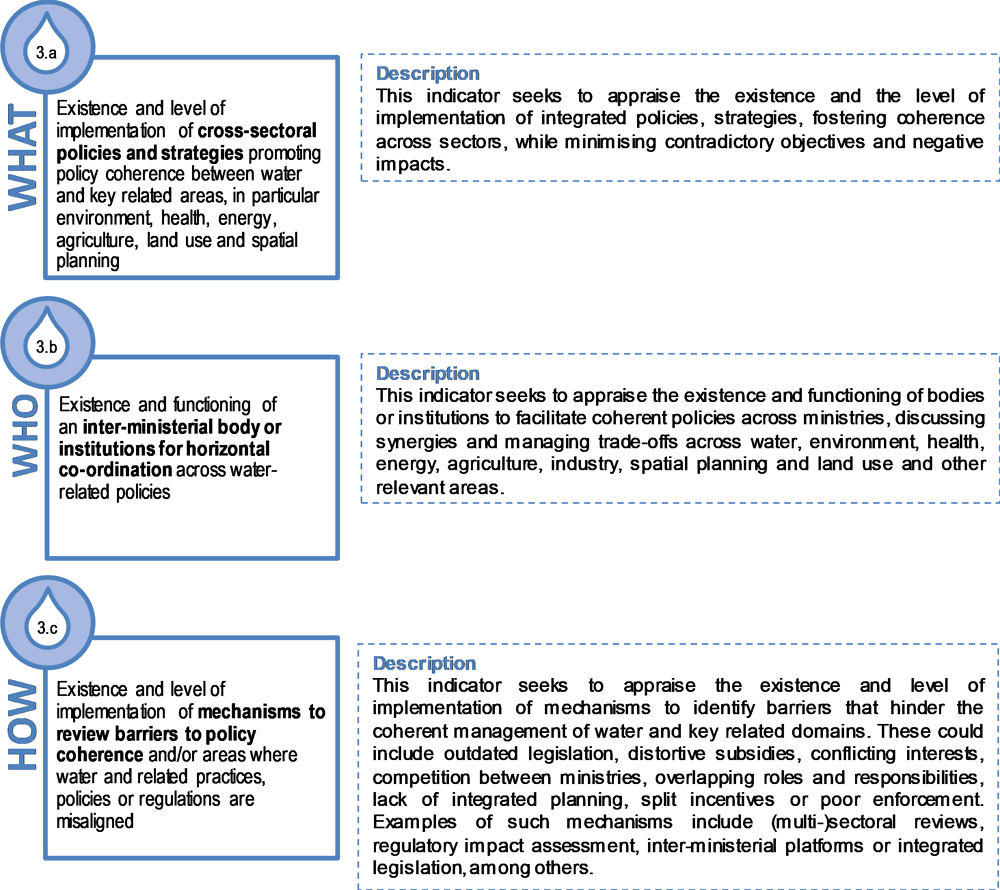

Principle 3: Policy coherence

Principle 3. Encourage policy coherence through effective cross-sectoral co-ordination, especially between policies for water and the environment, health, energy, agriculture, industry, spatial planning and land use through:

-

a) Encouraging co-ordination mechanisms to facilitate coherent policies across ministries, public agencies and levels of government, including cross-sectoral plans;

-

b) Fostering co-ordinated management of use, protection and clean-up of water resources, taking into account policies that affect water availability, quality and demand (e.g. agriculture, forestry, mining, energy, fisheries, transportation, recreation, and navigation) as well as risk prevention;

-

c) Identifying, assessing and addressing the barriers to policy coherence from practices, policies and regulations within and beyond the water sector, using monitoring, reporting and reviews; and

-

d) Providing incentives and regulations to mitigate conflicts among sectoral strategies, bringing these strategies into line with water management needs and finding solutions that fit with local governance and norms.

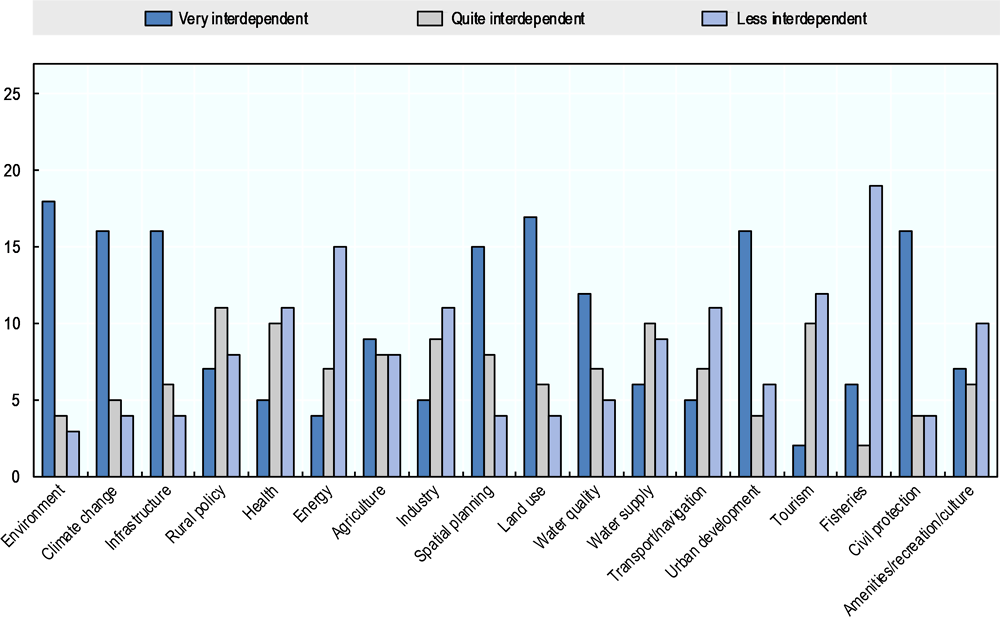

Observations

Flood risks are affected by decisions taken in various sectors. The most inter-dependent sectors include land use, civil protection, the environment, climate change, infrastructure, spatial planning and urban development. Thus, FRMSs cannot be isolated from these policy fields. Recent research shows that establishing a specific strategy or sector, such as FRM for instance, tends in practice to lead to a lack of integration among strategies (Matczak et al., 2016). Policy coherence within FRMSs, but also between FRMSs and other policy areas, is thus essential. For instance, FRMSs may require dams to be empty so that floodwater can be stored, while water supply strategies may require dams to be full, to guarantee stored water for all uses. Such concerns may become more critical if climate change puts pressure on water supplies. Water supply needs can also increase flood risk if groundwater extraction leads to subsidence, an issue in some cities.

Flood risks are often managed by water managers, but it is important to remember that spatial planners and risk managers also have an important role in cross-sector co-ordination. Indeed, cross-sectoral co-ordination should be careful to consider the role of spatial planners, who are generally in a good position to look at areas holistically (Hartmann and Driessen, 2013). Flood management should be included in spatial planning curricula, and spatial planners should be trained to take flood risks into account (De Smedt, 2014). Effective planning controls are the first line of defence and are at the heart of effective flood management. Integrating flood management and spatial planning is a top priority for effective cross-sectoral co-ordination in the field of FRM. It is essential that sectors other than water start to see flood risks as their problem. In addition, while in many countries, such as the Netherlands, water agencies take the lead on water infrastructure, flood management is often co-ordinated by risk managers, either through the interior ministry, civil protection, or a directorate general for the prevention of risk.

A lack of policy coherence can have severe distributional impacts on both the costs and benefits of flood management. Policy incoherence can: raise economic costs, as when infrastructure investments could have been avoided had there been better co-ordination (as exemplified in 19 case studies); generate conflicting actions, as for instance when urban policies support the development of housing in floodplains, while flood management policies use these floodplains for flood discharge (seen in 17 case studies); or alternatively, increase flood risks (16 cases). Other negative impacts of policy mismatch include greater risks of human casualties and greater transaction costs, for example, when conflicts arise between stakeholders involved in flood management. Lack of coherence in water-related areas can work against flood prevention policies.

A range of mechanisms can be employed to increase coherence and mitigate conflicts between flood management policies and other sectors. Some are legal/administrative, including legislation, regulation, cross-sectoral plans, inter-institutional agreements between sub-national authorities, financial incentives (e.g. subsidies) and contracts; others include learning mechanisms, such as research programmes, schooling and knowledge co-creation projects in different sectors. This can help ensure that flood management strategies include consideration of other sectors. For instance, 22 case studies collected reported that their strategies include information on areas that have the potential to retain floodwater (e.g. natural floodplains), while in other cases, the strategies include aspects of land use, infrastructure, environmental protections, spatial planning and soil/water management.

In many countries, existing procedures, rules and instruments could help promote proper consideration of flood risks in spatial planning. Examples of cross-sectoral policy co-ordination include Flanders’ “water test” and “signal areas”. The “water test” (watertoets) requires governments to obtain the expert advice of authorised water managers before granting construction permits (Wiering and Crabbé, 2006). “Signal areas” (signaalgebieden) are undeveloped areas with “hard planning” prospects (residential and industrial areas) located in flood-prone areas (De Smedt, 2014). Both these concepts require that permits be allocated subject to flood mitigating measures (e.g. flood-proof housing). French “zoning plans” (plans locaux d’urbanisme) and “territorial coherence plans” (schéma de cohérence territorial) and Polish “local spatial development plans” (miejscowy plan zagospodarowania przestrzennego) take into account housing developments, environmental considerations, transport and networks, approaches that have been found to encourage reflection on flood risks. Key elements of such approaches include risk awareness, knowledge exchange, active policy entrepreneurs and instruments that are not only enforceable but also actively enforced. These urban plans can also be regulated, in high flood-risk areas, by flood-risk prevention plans established by state services in conjunction with local authorities. The state of Queensland in Australia offers another example of cross sector coordination efforts. Its revised development legislation is now considering the possibility of granting some say to emergency response agencies, whose personnel and resources are put at risk due to floods (Raadgever et al., 2016). Cross-sector coordination measures should be increasingly promoted at all levels of government.

Areas to improve

OECD and non-OECD countries generally face problems in striking a balance between conflicting financial, economic, social, environmental areas and policy drivers for collective enforcement of flood policy (objective gap). For instance, municipalities may be willing to develop new housing and real estate, but this may conflict with the need to reduce flood risk. Often, time scales for policies diverge and can be difficult to align. In Bangladesh, for instance, different sectors compete fiercely for financial resources. One of the biggest challenges for the Flood Risk Maps for Surface Water in England and Wales was the limited data and information sharing across ministries and other essential water-related players. Water and flood policies are, in many cases, driven by decisions made in policy areas where water experts have little say (OECD, 2011). The issue of floods is generally spread across many different policy areas.

In practice, policy coherence in flood management is jeopardised by several factors: differences in policy goals, vested interests and perverse incentives, insufficient consultation and co-ordination, as well as inconsistencies and rigidities in the institutional structures that govern sectoral policies. Poor allocation of roles and responsibilities can create silos and amplify conflicting objectives. This is often the case when ministerial portfolios are strictly defined without sufficient mechanisms for cross-sectoral co-ordination.

Ways forward

Water is not an isolated sector and needs to seek out approaches that provide win-win solutions and combine diverse interests. Removing frequent bottlenecks through policy coherence and greater co-ordination is essential if governments are to prevent and mitigate floods. Legislation is also a good tool for ensuring policy coherence among national, regional/provincial and municipal authorities responsible for water, and other policies related to environment, land use and spatial development. The Environment and Planning Act in the Netherlands, to take effect in 2021, simplifies the current laws and combines them into a single act, to speed up decisions on projects and activities, among other things. Conflict mitigation and resolution mechanisms are needed to manage trade-offs across flood-related policy areas and take advantage of synergies. Assessments of the distributional impacts on flood management of decisions taken in other areas can help avoid future mismatches.

Climate change and flood management (usually considered under disaster risk reduction) are often treated as separate domains, because scales, frameworks, policies, time horizons, actors and institutions tend to differ. This can lead to competition over how to address the same issues, leading to redundant investment and policy inconsistency. Adaptive governance provides a window of opportunity to generate more collaboration and increase socio-ecological resilience. It is a good means for addressing climate and water-related disaster challenges, because it is founded on the view that governance systems are based on learning. This helps the players concerned to modify their practice based on new insights and experiences and to be flexible enough to respond to the uncertainties of climate change and water-related disasters. Such governance is polycentric, and values local knowledge and the sharing of responsibility between different levels of government. It also facilitates participation and collaboration of other sectors, interests and institutional arrangements (Keessen et al., 2013).

Making the most of policy complementarities requires ministries and other actors in water management to share responsibility and information. Their temptation to retreat into silo approaches can be mitigated by greater involvement of spatial planners and risk managers in flood management, since they generally consider the issues in a broad, interdisciplinary context. Governance mechanisms that encourage policy complementarities can help to increase capacity (e.g. by combining management of multiple sectors – waste, water, energy) and optimising financial resources.

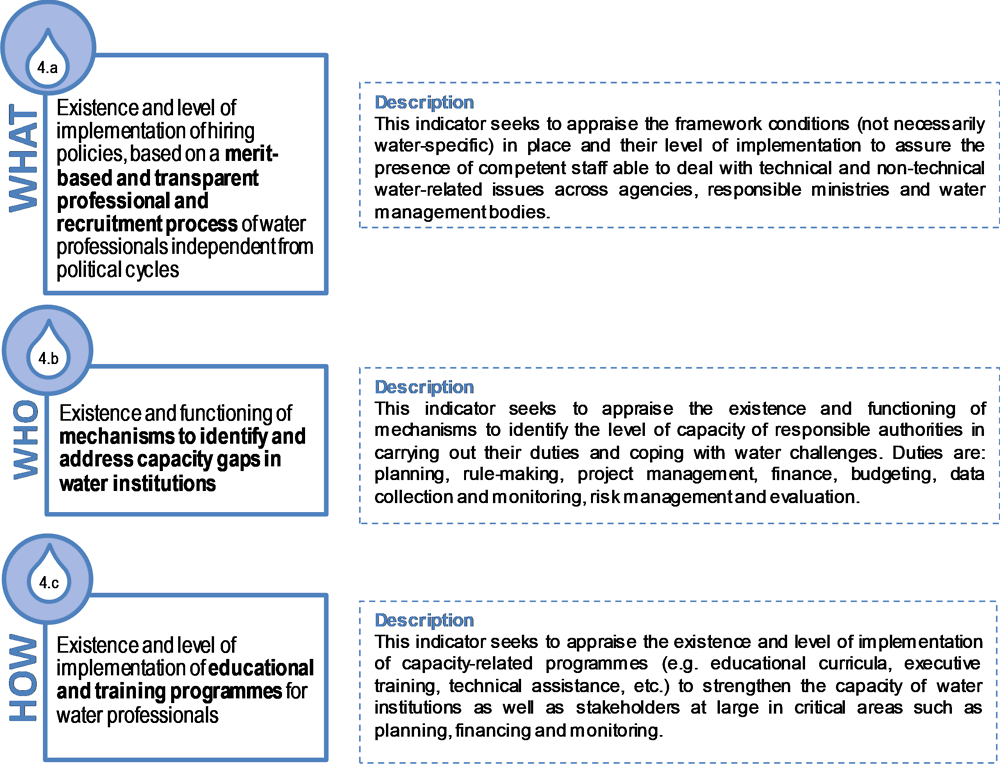

Principle 4: Capacity

Principle 4. Adapt the level of capacity of responsible authorities to the complexity of water challenges to be met, and to the set of competencies required to carry out their duties, through:

-

a) Identifying and addressing capacity gaps to implement integrated water resources management, notably for planning, rule making, project management, finance, budgeting, data collection and monitoring, risk management and evaluation;

-

b) Matching the level of technical, financial and institutional capacity in water governance systems to the nature of problems and needs;

-

c) Encouraging adaptive and evolving assignment of competences upon demonstration of capacity, where appropriate;

-

d) Promoting hiring of public officials and water professionals that uses merit-based, transparent processes and are independent from political cycles; and

-

e) Promoting education and training of water professionals, to strengthen the capacity of water institutions as well as stakeholders at large and to foster co-operation and knowledge-sharing.

Observations

Flood governance is contingent on mobilising the right capacities. OECD defines capacity as “the process by which individuals, groups and organisations, institutions and countries develop, enhance and organise their systems, resources and knowledge; all reflected in their abilities, individually and collectively, to perform functions, solve problems and achieve objectives” (OECD, 2006). Capacities fall under different categories2: technical capacity (e.g. modelling, early-warning systems, projections); financial capacity (e.g. ability to allocate funds for the construction of flood defences, willingness and capacity to pay for insurance schemes, capacity to raise taxes); human capacity (e.g. knowledge, skills, leadership, stakeholder engagement); governmental capacity (e.g. departments dedicated to flood management, policies, co-operation with research institutes); and infrastructural capacity (e.g. capacity to build green infrastructure, adaptive buildings, retention facilities, dams). The case studies indicate that each of these capacities is needed and in use for flood governance and that they condition the effective prevention and management of floods. Yet capacity levels vary widely: for example, rural areas with low population density have very different capacities for coping with flood risks from densely populated urban areas.

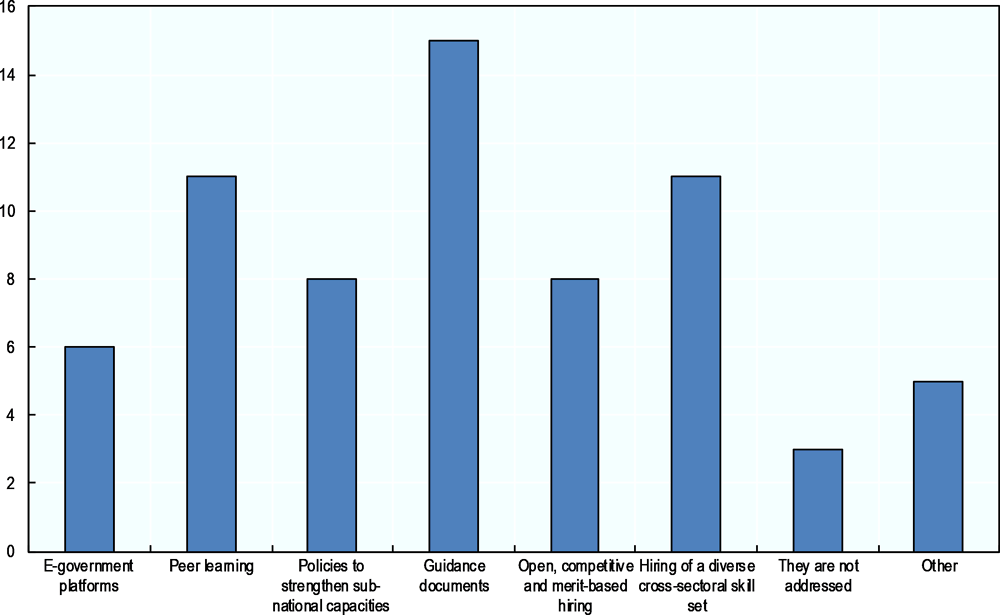

Some of the most common capacity gaps3 in water and flood management include carrying out reforms, managing multi-level relations, allocating responsibilities and funds, ensuring co-ordinated, coherent policy approaches, and attracting skilled and competent flood-risk professionals. Assessing where technical capacity, staff, time, knowledge or infrastructure are lacking is a critical step in bolstering FRGAs. The case studies collected show different ways of identifying capacity gaps: 16 case studies carry out studies examining governance capacity at various levels, 14 cases conduct post-event reviews, while a smaller number rely on an index of technical, financial, infrastructure or human capacity.

If infrastructure is one of the “hard” capacities generally well developed in OECD countries, more attention could be paid to the quality and resilience of this infrastructure. The G7 Ise-Shima Principles for Promoting Quality Infrastructure Investment call for i) ensuring effective governance, reliable operation and economic efficiency with a view to safety and resilience against natural disasters; ii) ensuring job creation, capacity building and transfer of expertise and know-how for local communities; iii) addressing social and environmental impacts; iv) ensuring alignment with economic and development strategies, including aspects of climate change and environment, at the national and regional levels; and v) enhancing effective resource mobilisation including through public-private partnerships.4 In addition, the OECD has developed a Framework for the Governance of Infrastructure that offers a methodology for analysing challenges, mapping out options for how to solve them, and guiding decision-making processes.5

Developing and strengthening capacity throughout the policy cycle can be a daunting and resource-intensive task. The case studies collected illustrate some ways to address capacity gaps (Figure 2.8. How capacity gaps are addressed in flood governance), such as guidance documents (used in 15 case studies) and hiring a diverse cross-sectoral skill set and peer learning (in 11 cases). Workshops and public meetings, guidebooks, and support programmes on flood risks are highlighted in the case studies as mechanisms that help educate and train flood governance stakeholders (e.g. flood plan managers, flood-risk professionals).

The case studies suggest several instruments for responding to co-ordination failures. As for policy complementarities, the Dutch Delta Programme, in collaboration with many other ministries and actors,6 has set up a Water and Climate Knowledge and Innovation Programme, focused on knowledge development and joint fact-finding through the development of a coherent set of knowledge agendas based on three pillars: i) bringing together the explicit and implicit knowledge from all stakeholders, including knowledge institutes, ii) developing knowledge only if it supports decisions and iii) managing knowledge only on demand. Social media and digital tools were used to encourage learning from each other (Bloemen, 2010). Furthermore, in Japan, drills (emergency exercises) are organised annually to prepare potential disasters with all stakeholders concerned at all levels and sectors. Such exercises help facilitate interaction, while building knowledge and behaviour about emergency response in cases of disasters. Finally, in England and Wales, a research study on potential measures to address financial capacity failures was carried out by UK Water Industry Research (UKWIR, 2016). Increased knowledge of funding opportunities and capabilities amongst different communities has helped them to undertake flood-risk measures and improve collaboration with water companies and other stakeholders.

Areas to improve

Many case studies indicate persistent challenges in making flood governance effective, efficient, inclusive and trustworthy. In the Chakar river basin of Sibi Balochistan, Pakistan, for instance, and at the intersection of the Arga and Aragon rivers in Spain, capacity needs to be built among such key stakeholders as farmers, associations of water users and citizens, so that they can effectively take part in decision making. Discrepancies in capacity not only affect a wide range of stakeholders but also amplify territorial disparities (urban, peri-urban and rural). In such cases, the differences in capacity, as well as political and economic factors, can complicate the relationship between places (OECD, 2013b).

A mismatch between the capacity needed to execute flood-related responsibilities and the capacity of the authority actually responsible can hold back flood management policies. Shortfalls in financial resources; in the political will to allocate resources to capacity development; in staff and technical skills; and in training tools and methodology, affect capacity development and need to be addressed. For example, the human capacity, tools and experience required to implement the EU Floods Directive are in short supply in the countries of the Western Balkans (European Commission, 2015). At present, higher education institutions in most Western Balkan countries are not turning out enough flood management experts and water professionals with the requisite skills to establish and operate databases, monitoring and early-warning systems necessary to comply with the Floods Directive (European Commission, 2015). Organisations also often fail to recognise the wide range of characteristics (both “soft” and “hard”) that are needed for effective flood management. Building sufficient capacity may include educating engineers to adopt a more holistic perspective on flood management, the exchange of expertise through communities of research and practice, and knowledge co-creation.

Ways forward

Assessing capacity gaps is a critical step towards reinforcing the skills needed to face and manage flood risks. Ensuring a diverse skill set within organisations is critical for effecting change, and can have a major influence on organisational culture and the flood management approach used (see for example Huitema, 2002). Including stakeholders from the public, private and non-profit sectors can play an important part in pooling resources, skills and expertise, and integrating flood management, as well as knowledge sharing. This also relates to the science-policy interface mentioned in Principles 5 and 8. Policy makers and decision makers may be quick to adopt measures and approaches they are familiar with (e.g. from their specialist field) but they may resist evidence-based findings if the findings do not mesh with their values or worldview. For example, engineers may be resistant to undertake new ecosystem-based measures that ecosystem scientists are quick to embrace (Huitema, 2002). Employing personnel who are receptive to scientific advances across a range of fields and disciplines, and who are conversant with the science, is important, as is ensuring that capacity building includes both “soft” and “hard” skills.

References

Abel, N. et al. (2011), “Sea level rise, coastal development and planned retreat: analytical framework, governance principles and an Australian case study”, Environmental Science and Policy, Vol. 14/3, pp. 277-288, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2010.12.002

Bloemen, P. (2010), “Transitions and the role of knowledge and innovation management”, presentation available at: http://edepot.wur.nl/326813http://edepot.wur.nl/326813.

Cairney, P. (2012), Understanding Public Policy: Theories and Issues, Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire, England; Palgrave, Macmillan, New York.

De Smedt, P. (2014), “Towards a new policy for climate adaptive water management in Flanders: The Concept of signal areas”, Utrecht Law Review, Vol. 10/2, pp. 107-125.

Dieperink, C. et al. (2013), “Flood Risk Management in Europe: Governance challenges related to flood risk management (Report No. D1.1.2)”, STAR-FLOOD Consortium, Utrecht, the Netherlands. ISBN: 978-94-91933-03-5.

Driessen, P.P.J. and H.F.M.W. Marleen van Rijswick (2011), “Normative aspects of climate adaptation policies”, Climate Law, Vol. 2/4, pp. 559-581.

European Commission (2015), “Flood prevention and management – Gap analysis and needs assessment in the context of implementing the EU Floods Directive”, Brussels, September.

FEMA (2016), website: www.fema.gov, consulted 15 June 2016.

Hartmann, D. and P.P.J. Driessen (2013), “The Flood Risk Management Plan: Towards spatial water governance”, Journal of Flood Risk Management, https://doi.org/10.1111/jfr3.12077

Hegger, D.L.T. et al. (2013), “Flood risk management in Europe: Similarities and differences between the STAR-FLOOD consortium countries”, STAR-FLOOD Consortium, Utrecht, the Netherlands.

Huitema, D. (2002), “Regge River Basin: Case Study 2 of the EUWARENESS research project, University of Twente”, available at: www.euwareness.nl/results/Ned-2-kaft.pdf.

ICPDR (2015), Flood Risk Management Plan for the Danube River Basin District, Vienna, Austria, available at: file:///C:/Users/hassenforder_e/Downloads/1stdfrmp-final.pdf.

Keessen, A.M. et al. (2013), “The concept of resilience from a normative perspective: Examples from Dutch adaptation strategies”, Ecology and Society, Vol. 18/2, p. 45.

Matczak, P. et al. (2016), “Comparing flood risk governance in six European countries: Strategies, arrangements and institutional dynamics”, (Report No. D4.1), STAR-FLOOD Consortium, Utrecht, the Netherlands.

McCarthy, S., C. Viavattene and C. Green (2018), “Compensatory approaches and engagement techniques to gain flood storage in England and Wales”, Journal of Flood Risk Management, Vol.11/1, pp. 85-94.

Menard, C., A. Jimenez and H. Tropp (2018), “Addressing the policy implementation gaps in water services: The key role of meso-institutions”, https://doi.org/10.1080/02508060.2017.1405696.

OECD (2018), Implementing the OECD Principles on Water Governance: Indicator Framework and Evolving Practices, OECD Studies on Water, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264292659-en.

OECD (2013b), Rural-Urban Partnerships: An Integrated Approach to Economic Development, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264204812-en.

OECD (2011), Water Governance in OECD Countries: A Multi-level Approach, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264119284-en.

OECD (2006), Applying Strategic Environmental Assessment: Good Practice Guidance for Development Co-operation, DAC Guidelines and Reference Series, Development Assistance Committee, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264026582-en.

Productivity Commission (2014), Natural Disaster Funding Arrangements, Inquiry Report no. 74, Productivity Commission, Canberra, Australia, available at: http://www.pc.gov.au/inquiries/completed/disaster-funding/report.

Raadgever, T. et al. (2016), Practitioner’s Guidebook Inspiration for flood risk management strategies and governance STAR-FLOOD Practitioner’s Guidebook, STAR-FLOOD Consortium, Utrecht, the Netherlands.

UKWIR (2016), “How best to align the funding processes with the various bodies involved in resolving flooding,” UK Water Industry Research Ltd., London.

Wiering, M. and A. Crabbé (2006), “The institutional dynamics of water management in the Low Countries”, in B. Arts and P. Leroy, Institutional Dynamics in Environmental Governance, Springer, Dordrecht, pp. 93-114.

Notes

← 1. Flood anticipation or foresight, flood prevention or mitigation, flood preparation or preparedness, flood response, flood recovery.

← 2. Generally, capacities can be distinguished between “soft” and “hard”. “Hard” capacities relate to tangible financial and infrastructural “deliverables” and associated technical skills (e.g. early-warning systems, urban green infrastructure, tax systems). “Soft”, more intangible capacities include human aspects such as leadership, staff motivation, shared values, co-ordination, social expertise, communication, facilitation and knowledge.

← 3. In the case studies collected, these capacity gaps are assessed most often through specific studies examining governance capacity at various levels (in 16 case studies) and post-event reviews (in 14 cases). Four of the case studies collected indicated not assessing capacity gaps.

← 4. They were released on 27 May 2016, see www.japan.go.jp/g7/summit/documents/index.html.

← 5. See OECD (2015), Towards a Framework for the Governance of Infrastructure, available online at: https://www.oecd.org/gov/budgeting/Towards-a-Framework-for-the-Governance-of-Infrastructure.pdf (accessed on 6 October 2016).

← 6. Ministry of Infrastructure and the Environment, the Ministry of Economic Affairs, the Foundation for Applied Water Research (STOWA), the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (NWO), the Royal Netherlands Meteorological Institute (KNMI), the Netherlands Environmental Assessment Agency (PBL), Deltares, the independent Netherlands Organisation for applied Scientific Research (TNO), Alterra, universities, and the Dutch Topsector Water.