copy the linklink copied!3. The experience of Chile

This chapter presents a summary of service provision in Chile. It opens with a discussion of the background to services in Chile providing the origins and evolution of ChileAtiende into the service it provides today.

That status quo is presented in three parts: the oversight of services in Chile; the operation of ChileAtiende; and finally, an overview of the various other service delivery channels that exist in the country.

This chapter will consider the service design and delivery experience of Chile. To begin with, the chapter will present the origins of ChileAtiende and its evolution since then. Having traced its evolution, the chapter will consider the present status of service delivery in Chile with a discussion of both ChileAtiende and the other ways in which the public can access services.

Having described the current situation, this chapter will analyse the current situation in light of the conceptual framework advanced in the previous chapter in focusing on an analysis of the context, the philosophy and the enablers for service design and delivery in Chile.

copy the linklink copied!The background to services in Chile

When the Piñera administration took office in 2010, it made the experience of citizens in accessing services a political priority. To do this the President created a Committee - led by the former Modernisation and Digital Government Unit (MDGU, now the Digital Government Division) at MINSEGPRES - tasked with improving the proximity of the state to citizens and the ease with which public services could be accessed. This mandate allowed the committee to coordinate service delivery across agencies, engaging each institution in turn and offering support with improving their service delivery.

From these exchanges, the multi-channel model of ChileAtiende emerged to provide a single point of access to government. Modelled on the experience of Canada in the design and delivery of Service Canada (see Box 3.1), the vision for this network of physical locations, a telephone call centre and a website was for citizens to be able to access all they needed in the same place across multiple government services and with visibility of their historic interactions with the state. Alongside the creation of this multi-channel network was the ambition to build a brand, and a concept, that resonated with the public and increased adoption of services through the most appropriate channel.

The inspiration for ChileAtiende drew on several international examples including eCitizen in Singapore, Centrelink in Australia and Service Canada to be from the outside a network of provision across multiple channels and not just an online, e-government approach to meeting the needs of the public.

Service Canada was one of the inspirations because it has an impressive pedigree in wanting to meet the needs of Canadians. In 1998, the government undertook detailed surveys of citizens’ needs and expectations to develop “an integrated citizen-centred service strategy”. Yet it was not until 2005 that Service Canada formally began operations with a mandate to offer a single point of access to a wide range of government services and benefits through the Internet, by telephone, in person or by mail.

To fulfil this responsibility Service Canada has 610 locations across the 13 provinces and territories of the country with further mobile outreach services operating in remote and isolated areas. Online, Service Canada provides access to more than 72 government programs and services (Canada.ca, 2019[1]).

Service Canada recently opened a new flagship location designed with their users at its heart and acting as a testing ground for future innovations to be rolled out nationally. This includes the availability of virtual based service delivery increasing the availability of services by introducing access to offsite members of staff with particular specialisms. This understanding of the importance of moving from in-person to online is underscored by providing tablets, headsets and public Wi-Fi to encourage their visitors to self-serve where possible. The flagship location has also introduced innovations to support those who access services with the assistance of inclusive technologies putting a high priority on accessibility for all.

The Service Canada team also looks to enhance the accessibility of its services with those who are located outside the scope of their physical locations. The Satellite-in-a-Suitcase project for example is designed to bring connectivity to Canadians in remote communities. Given the geographic context of Canada there is a challenge of creating the necessary connectivity to ensure access to services. In response to the need Service Canada developed a solution that equips their outreach staff with the necessary mobile technology to connect to the same experience as those who visit any Service Canada Centre.

Source: Canada.ca, (2019[2]), Improving services for Canadians

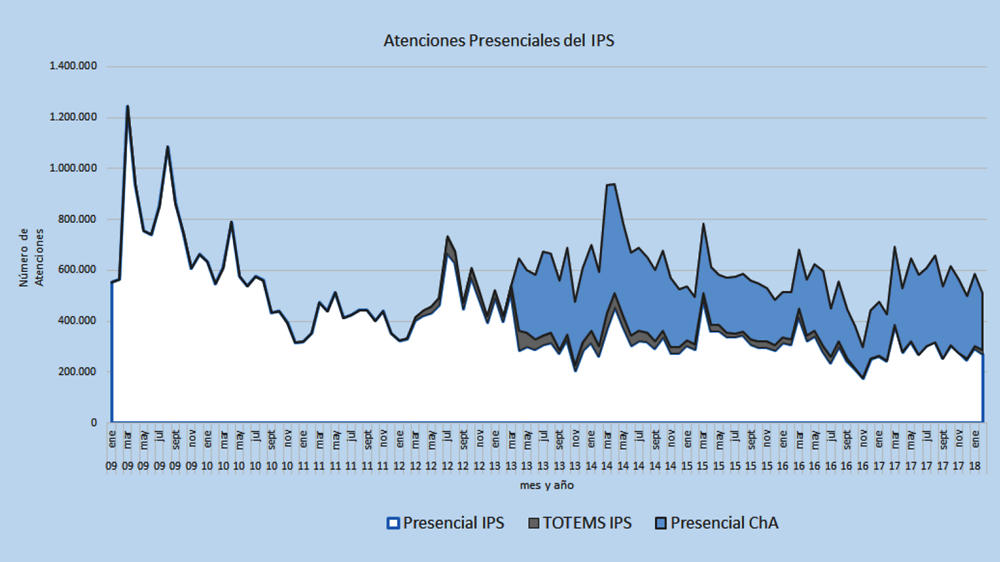

The means by which this vision was put into reality was through integrating two existing service delivery channels: Chile’s original e-government platform, ChileClick; and the physical network operated by the Social Security Institute (Instituto de Previsión Social, IPS) to administer the state pension. When reforms to the social security system reduced demand for IPS services (see Figure 3.1), its network of physical locations was combined with ChileClick to support a multi-channel strategy in order reduce the time and effort involved for citizens in visiting multiple locations for their needs of government to be met. This hybrid of physical and online channels would eventually become ChileAtiende.

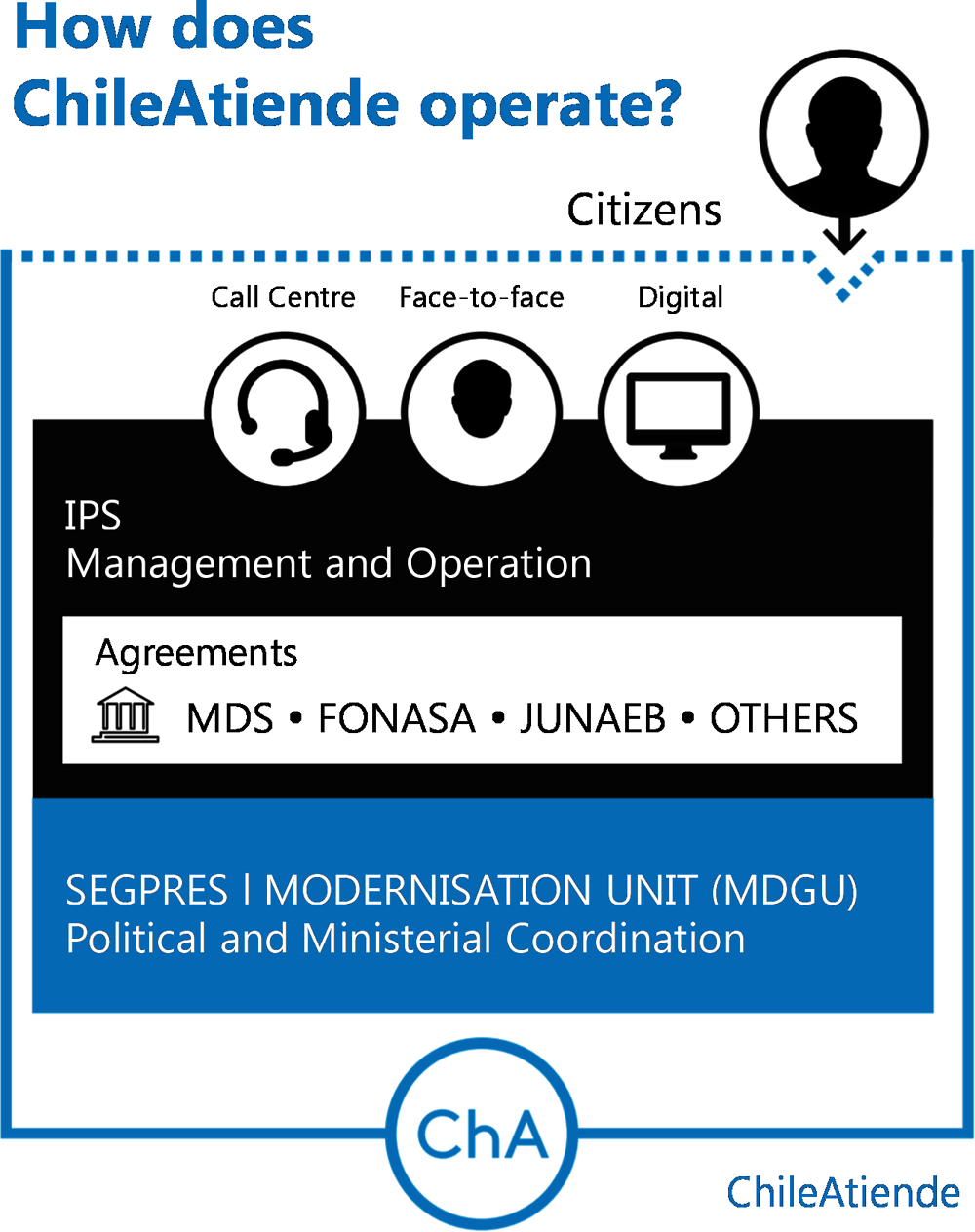

ChileAtiende itself was the result of bringing existing service delivery channels under a common brand but not common ownership. Face-to-face and telephone services were based on the longstanding service delivery model of IPS but the digital channel (initially the website and later expanded to social media and self-service kiosks) was commissioned by MDGU. Nevertheless, building on these established channels made it possible to take a more evolutionary approach. The IPS network represented an existing network of locations, providing a trusted source of access to the government across the country and with existing human, financial and physical resources to develop. The IPS network also had existing relationships with the National Health Fund (Fondo Nacional de Salud, FONASA) which reflected the intention of creating a unified service experience across the public sector.

Reflecting this patchwork approach, both the strategy and governance of ChileAtiende has been until recently split in two. The mandate of the President, MDGU and the Ministry General Secretariat of the Presidency (Ministerio Secretaría General de la Presidencia, MINSEGPRES) were responsible for the governance and political coordination for the network with its operation directed by IPS (see Figure 3.2).

The ChileAtiende Committee worked with the agencies to identify the most appropriate additional services to incorporate into the newly created ChileAtiende network. Although a mandate existed for creating ChileAtiende, there was no compulsion for the public sector organisations to include their services and so an approach was developed to encourage them to work with the new platform. Their approach to including services within ChileAtiende was three-fold:

-

1. First, identify the most heavily used services by citizens and businesses

-

2. Then, analyse those most heavily used services to identify other, related, services to add

-

3. Finally, increase coverage for services from small organisations with low levels of capability to develop solutions themselves

During this period, the government invested heavily in marketing with television campaigns running from 2011 to 2013 resulting in a suggested 30% increase in awareness and access of ChileAtiende. Having initiated this process and begun to work with public sector organisations to increase the quantity of services provided through the nascent ChileAtiende model, the priority became longer-term sustainability. Legislation was put to the Chilean Congress by the end of 2013 with the intent of establishing a standalone agency hosted at the Ministry of Finance (responsible for several public administration functions such as civil service, procurement and budgeting), with responsibility for the multi-channel service design and delivery agenda (Cámara de Diputados, 2013[5]). The Congress did not pass this legislation during this period.

The elections of 2014 returned former President Bachelet to office. Her previous period in power (from 2006 to 2010) had witnessed the creation of ChileClick and other e-government efforts as well as the pension reforms that affected the demand of IPS services and in doing so created spare capacity and the opportunity to develop ChileAtiende. Her term saw a shift away from central coordination to more localised decision making with public sector organisations delivering value according to their understanding of the needs of their users. As a result, there was no longer oversight and influence provided by the governance model that had been in place through the ChileAtiende Committee. Instead, efforts to leverage the ChileAtiende digital channel were channelled through the Modernisation of the Public Sector Programme (Ministry of Finance) and DGD, which ran a project to increase the number of transactions in ChileAtiende’s web channel for the period 2016-2019.

Moreover, due to the ChileAtiende brand being heavily associated with the Piñera Presidency there was also reduced enthusiasm within the new administration. Between 2014 and 2018, ChileAtiende enjoyed a lower profile with the IPS branding being re-emphasised and a more organisation specific approach becoming the priority. Although several institutions maintained the service focus of the ChileAtiende vision, some of the momentum to grow a cross-government, single purpose access point for citizens was lost.

Chile returned to the polls in December 2017 and re-elected President Piñera for a second term. In returning to power, he made ChileAtiende the flagship for service delivery. A key priority in his manifesto was to digitalise at least 80% of public procedures before 2022, aiming at having a “no queues and paperless” State by 2025. In pursuit of this, there have been efforts to de-politicise ChileAtiende by passing legislation that would institutionalise ChileAtiende and establish it in its own right and insulate it from any political upheaval.

This legislation is identical to that previously sent by President Piñera to Parliament at the end of 2013 (Cámara de Diputados, 2013[5]). It is intended to give the Ministry of Finance two responsibilities. First, responsibility for the vision of shared service delivery across the whole of government. Second, oversight and responsibility for delivery of the ChileAtiende network instead of IPS. The intention is to enshrine both ChileAtiende and the service delivery ambition in law to provide a sustainable approach to multi-channel service delivery that persists from one administration to the next. However, this discussion has not been prioritised in Parliament, with no progress during the period of this study.

copy the linklink copied!Current approach to services in Chile

Oversight of services in Chile

Under the current administration in Chile, there has been steady support given to the modernisation and digital government agenda. The Government of Chile has worked with the OECD in developing several pieces of work to guide and shape the transformation of the public sector to take full advantage of digital government practices.

Digital Government in Chile: Strengthening the Institutional and Governance Framework (OECD, 2016[6]), delivered policy recommendations that guided subsequent reforms to the institutional framework for digital government in Chile in the creation of the Digital Government Division (DGD) in MINSEGPRES. This represents a step forward as now digital government is, by law, a public function performed by MINSEGPRES. As a follow up to this, Digital Government in Chile - Making the Digital Transformation Sustainable and Long-lasting, focused on embedding digital opportunities into everyday public sector operations in a whole-of-government approach.

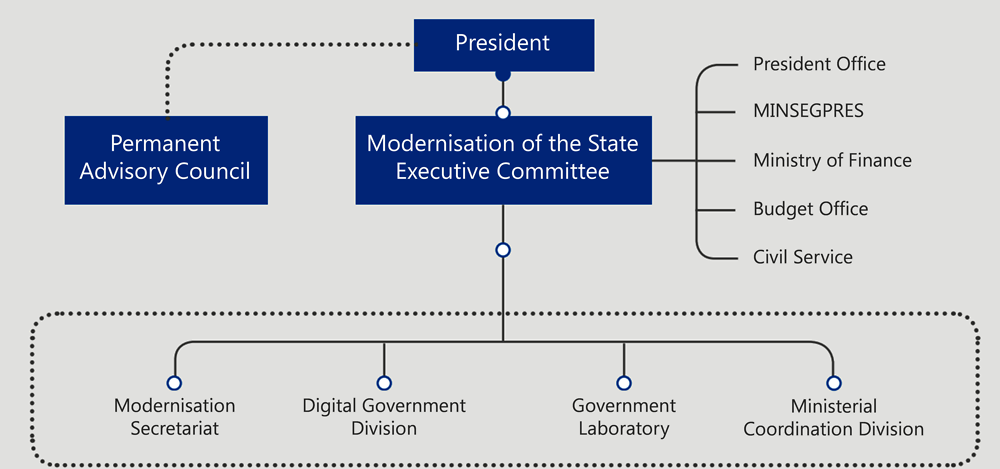

The priority given to this agenda is reflective of the importance placed on the modernisation of the Chilean public sector. As a result, President Piñera has established a new institutional architecture to coordinate and lead modernisation of the State efforts (see Figure 3.3).

One of the most critical contributors to this is the Permanent Advisory Council for the Modernisation of the State. This council is appointed with an advisory role to the President on matters concerning both policy and also the machinery and organisation of government in areas such as public employment, budgeting and the digital transformation of the public sector, among others. This is quite a broad remit, and extends beyond the delivery of services and ChileAtiende.

The Council is a permanent body that meets every 15 days with a membership of 13 people consisting of representatives from academia, the private sector and those with a history of working within government. The members of the Council are appointed by government but are independent, following the model set elsewhere in Chile by the Council for Productivity in terms of a partial refresh of the membership every year.

The members of the Council see themselves as facilitators, especially where the topic has potential political sensitivity and this is helped by their apolitical status. Whilst the government sets the agenda, the Council is designed to help and improve what that agenda says in terms of how the government takes it forward, giving larger attention to the policies which have higher impact on the performance of the State.

The Council represents the perspective of those outside government and is complemented by the Executive Committee for the Modernisation of the State consisting of representation from the Office of the President, the Ministry of Finance and its Budget Office (DIPRES), the DGD of MINSEGPRES as well as the Chilean Civil Service. The make-up of this committee helps to achieve co-ordination by aligning finance with policy and delivery.

Through the Committee, four taskforces have been established to lead the modernisation agenda. First, the Modernisation Secretariat at the Ministry of Finance (former Modernisation of the Public Sector Programme) responsible for coordinating different cross-sectoral projects and exerting technical support to both the Council and the Committee. Second, DGD in MINSEGPRES responsible for digital transformation and data policies. Third, the Government Laboratory (Laboratorio de Gobierno, LabGob) providing focused consultancy to public agencies in terms of service design. Fourth, a co-ordination division within MINSEGPRES with oversight of government programmes and commitments that cut across organisations.

This Committee provides the high-level coordination and direction for the overall modernisation of the State agenda in Chile, including ChileAtiende. It is through their deliberations that the proposed legislation for institutionalising ChileAtiende is being reintroduced to the Chilean Parliament. Furthermore, this Committee has provided the foundation for the development of the Government’s Digital Transformation Strategy (Box 3.2) making provision for several critical elements in the service design and delivery agenda for Chile and setting out the ambition for the future digital transformation of the country. This strategy has set specific goals for public agencies to achieve in terms of digitalising public processes, which form the basis for “no queues and paperless” mandate in the country.

One of the key milestones for the modernisation of the State in Chile is the recently passed Digital Transformation of the State Law (MINSEGPRES, 2019[8]). Among several other mandates, this law may represent a shift in public service delivery as it requests public agencies (both at central and local levels) to only use electronic means to provide services (paperless approach), stressing the relevant role for DGD in defining and implementing sound and coherent data sharing, digital identity and advance electronic signature strategies. The implementation of this law, within a timeframe of five years, presents a unique and significant window of opportunity for public agencies to not only simplify or digitalise products and services but create public value by transforming how public services can adopt a user-driven approach in rethinking public services.

The Digital Transformation Strategy

President Piñera has placed the digital transformation of the State at the core of his administration. DGD, the agency responsible for digital government, has defined a strategy for 2018 to 2022 which aims at having a paperless and no queues public administration (Cero Papel and Cero Filas). The ambition is for public agencies to digitalise public service delivery so Chilean people can benefit from digital technologies to ease their interactions with government. The strategy is driven by three aims:

-

Better services for citizens and businesses, in order to increase public trust and well-being through timely and accessible services

-

Better public policies, transparency and accountability through the strategic and intensive use of data as well as increased spaces for citizens participation

-

Consolidated digital transformation of the State, as a long-term and permanent approach

The strategy sets out strategic and operational principles to be implemented. Additionally, the strategy establishes the operational needs for implementing the Digital Transformation of the State Law and the standards and technologies under the responsibility of DGD it requires (see below).

The Digital Transformation of the State Law

President Piñera promulgated the Digital Transformation of the State Law in November 2019 in order to provide the means for public agencies to deliver on the promise of simplifying interactions between citizen and State. The law mandates public agencies (both at central and local levels) to become paperless within five years, leaving paper-based procedures only for exceptional cases. The law requests that:

-

all administrative procedures will be digital-based and stored in digital records;

-

communications among public agencies will only occur through digital means;

-

documentation requested for administrative procedures will need to be digital-based, and in case of paper-based documents these will need to be digitalised;

-

administrative procedures will be signed using electronic signature;

-

all notifications from public agencies to citizens will occur through digital systems and e-mails

There are five years before it fully enters into force but a single year in which to define a regulatory framework of standards and identifying platforms to equip public agencies. As digital by default becomes the standard for administrative procedures, the law will require a series of enablers such as:

-

full interoperability between public agencies

-

the consolidation of a national catalogue of services

-

document management systems and standards (including strengthening the role of the National Archive in preserving official documents issued by public agencies)

-

the expansion and strengthening of ClaveÚnica as digital identity system

-

advance electronic signature mechanisms

DGD and the Modernisation Secretariats are responsible for coordinating and overseeing the production of these standards as well as for the compliance to the law before coming into force.

Source: Own elaboration based on División de Gobierno Digital, (2019[9]), Digital Government Strategy and MINSEGPRES, (2019[8]), Digital Transformation of the State Law.

The operation of ChileAtiende

Responsibility for ChileAtiende

Whilst the Council and the Committee provide high-level oversight for the modernisation agenda, including both digital government and service design and delivery, there is a dedicated Committee for ChileAtiende. This Committee comprises representatives from the Presidency, DGD, the Budget Office, IPS and ChileAtiende, and monitors the specific strategy and operation of ChileAtiende. The operational responsibility for operating ChileAtiende today rests with IPS with all of those who work for ChileAtiende being employees of IPS.

As of today, the operation of the entire multichannel network relies on IPS and its ChileAtiende division. Face-to-face and telephone channels have been under its responsibility since the creation of ChileAtiende but the digital channel (web and self-service kiosks) only recently transferred from the DGD of MINSEGPRES. Involvement of DGD in ChileAtiende now focuses only on developing guidance in terms of technology and the provision of particular enabling technologies, such as ClaveÚnica, Chile’s digital identity solution (discussed in Chapter 4) and interoperability systems.

IPS has created an internal unit to lead on digital transformation rather than to draw on the resources and expertise of DGD. However, as their mandate is on the internal transformation of IPS rather than with a broader mandate to work with service delivery organisations across government it is anticipated that DGD will continue to develop the services and software required to support ChileAtiende, which may demand further clarification of roles.

Overall, government services in Chile operate independently and have to use a service specific platform. In the absence of a common service infrastructure, DGD manages PISEE (Plataforma Integrada de Servicios Electrónicos del Estado), a SOAP-based integrated interoperability platform which provides data exchange only for a number of Chilean services. Figures from DGD indicate that only around 18% of interoperability agreements between public agencies occur through PISEE in 2019.

Channel strategy1

The channel strategy for ChileAtiende is three fold: multi-service, multi-channel, and multi-layer.

By being multi-service, ChileAtiende sees services aggregated from 28 institutions with a total of 274 services available for use (167 from IPS and 107 from other organisations). The quantity of IPS services provided through ChileAtiende reflects the close historic relationship between the two and those services account for 50% of all requests with 22% being related to health care and access to FONASA.

In being multi-channel, services are provided across face to face, telephone and digital (including website, social networks and self-service kiosks):

-

Face to face: there are 254 physical locations where ChileAtiende can be accessed, with 192 of those permanent locations and the remainder accessed periodically by a mobile venue. In total, this provides 80% coverage of the country. A private provider puts on events for those without CA locations. 15% of these locations are shared with other service providers including the police, and the Service of civil registration and ID (Servicio de Registro Civil e Identificación, SRCeI). 39 are designed to be inclusive spaces, offering spaces for breastfeeding and entertaining children as well as offering translation services by video call.

-

The face-to-face channel is staffed by 1 500 officials and handles 6 million requests a year. This figure has dropped from a peak of 8 million visits in 2014. Many of those who use the face-to-face channel are unable to access services online.

-

Telephone: the call centre of 65 operators receives 150 000 calls a month. All of these enquiries are for information rather than as transactions due to current limitations of the country’s digital identity solution (see Chapter 4). Although many of the enquiries can be addressed by the team, a proportion of them are re-routed to the relevant provider elsewhere in government.

-

Digital: the digital channel comprises the website, social media and self-service kiosks channels. The website receives 24 million interactions a year however, the current limitations of the country’s digital identity solution mean that it is not possible to complete a transaction so these can only be for information. The social media team respond to 300 requests a day. Reflecting the increasing attention being paid to the digital channel the website is experiencing 30% year of year growth. The ChileAtiende website is a hub that hands off to services provided through the websites of the relevant organisation. The content for those websites, and ChileAtiende itself, takes place at the institutional level meaning that multiple sites must be maintained and there are challenges in tracking user journeys and performance. Some services have been developed for self-service kiosks; as these use a separate technical architecture to those services available online they could be defined as an additional channel.

Finally, in being multi-layer, services are provided according to the depth of integration with a given institution. For a number of services, and in all three channels, users can fully complete an enquiry or transaction with the relevant party but as highlighted, the constraints with digital identity mean more common experience is to provide information and then signpost a user elsewhere to carry out the necessary final interaction with the relevant service through the provider’s own, separate, channel. Only services provided by FONASA can be paid for.

Currently, only 6% of the total number of public service transactions in Chile are offered directly through ChileAtiende meaning the vast majority of service interactions take place directly between a user and the relevant service provider’s website, call centre or physical location (Ministerio de Hacienda, 2018[3]). Although ChileAtiende accounts for a small proportion of the total transactions carried out between the Chilean government and the public it reports a 71.5% satisfaction rating, which is the highest of all service providers2.

Other service delivery channels3

With ChileAtiende accounting for a small proportion of all transactions between citizens and the state, an important part of understanding service design and delivery in Chile is how alternative channels manifest themselves. One of the biggest drivers for standalone services is the desire for different parts of government to trace their users. As a result, there are several different ‘My account’ services provided by organisations including ChileAtiende, FONASA and IPS amongst others.

In several cases, ChileAtiende lists the transactions and services offered by other parts of the government. Ongoing efforts to make ChileAtiende the preferential entry point for citizens in accessing public services are led by the Presidency, while for some agencies the ambition is that the separate bespoke channel would be replaced by working increasingly closely with ChileAtiende.

Service of civil registration and identity (Servicio de Registro Civil e Identificación, SRCeI)

The SRCeI has the largest service delivery network in Chile, operating from more than 400 offices across the country. A small number of these are co-located with ChileAtiende. Their call centre receives 60 000 calls a month and 30 000 contacts a year online. The ChileAtiende call centre and website provide a seamless experience of access SRCeI services.

The SRCeI falls under the remit of the Ministry of Justice and is responsible for managing 23 base registers including those dealing with identity, births, vehicles and drivers. The SRCeI provides the underlying identity infrastructure for Chile’s physical identity card the Cédula de Identidad as well as working with the DGD of MINSEGPRES on the digital identity solution ClaveÚnica.

As well as maintaining registers, the SRCeI also issues certificates with around 13 million issued in persona and 19 million issued online each year. All certificates are available through the ChileAtiende website (as well as their own). The most popular certificate is one related to police records, which is needed when looking for a job. An integration for this data is provided to the Attorney General’s Office but no other services are using it despite the frequency with which it is requested.

Certain services provided by the SRCeI require the presence of a notary and as a result, there is a legal requirement for SRCeI to offer a face-to-face channel. This is one reason why SRCeI transactions are not all available at ChileAtiende locations.

Internal Revenue Service (Servicio de Impuestos Internos, SII)

The SII has 60 branches around the country and through their web channel alone handle 200 million transactions a year. 95% of those transactions are dealt with by first layer support agents.

SII’s integration with ChileAtiende works in two ways. First, with the ChileAtiende call centre providing direct, first layer support to citizens for a certain amount of enquiries and routing them on to SII contacts where appropriate. Second, the ChileAtiende website contains information about 80 transactions. This information is duplicated on the SII’s own website.

National Health Fund (Fondo Nacional de Salud, FONASA)

FONASA provides universal health coverage with private providers and counts 80% of the Chilean population (14 million people) amongst its users. Those on low incomes do not pay a fee whilst others pay 7% of their monthly income to access the health insurance and the level of care they access varies depends on the level of that payment. Citizens have the option of accessing private health providers if they pay a top up. It is expected that FONASA services such as certificates and sick leave approval status can be available through ChileAtiende in the near future.

It operates its own network of face-to-face service locations, a telephone call centre and a website. However, there are integrations with ChileAtiende locations in order for citizens to obtain the certificates and vouchers that are required to demonstrate eligibility or proof of payment. 80% of all transactions relating to healthcare insurance take place in person.

Superintendence of Social Security (Superintendencia de Seguridad Social, SUSESO)

SUSESO operates their own physical location with 74% of all claims made in person with a call centre that is able to provide information but no transactions. The other 26% of transactions are handled online, reflecting the low digital confidence of their users. SUSESO are eager to be absorbed into ChileAtiende do not want digital transformation to mean simply that some more digital certificates are available online, they view the potential of digital transformation via ChileAtiende to mean the creation of a universal platform that can respond to the unique challenges of any existing, or newly developed service.

Directorate of Labour (Dirección del Trabajo, DT)

DT operates from its own locations with 50 staff members attending to 750 000 calls year. It is the intention for ChileAtiende to provide a first layer of support in resolving simple, standardised procedures and, in time, for all procedures to be handled directly by ChileAtiende, at least over the phone. However, previous attempts at equipping ChileAtiende call centre staff to handle DT enquiries proved unsuccessful with the enquiries still being routed to DT.

DT has a commitment to developing services that focus on the needs of the user, ensure integration is possible and look to simplify interactions. However, many of their services are still paper based and so a technical platform is under development to create an omni-channel experience for their users. Whilst they would like to collaborate more extensively with their partnering organisations there was clear frustration that they had been unable to achieve an integration with FONASA despite their services accounting for 70% of DT’s activity and such an integration having benefits on both sides.

Ministry of Social Development and Family (Ministerio de Desarrollo Social y Familia)

The Ministry operates its own call centre and website as well as a channel for written correspondence (both email and postal). The services it provides are included in the ChileAtiende website. In this case, a strong multi-channel approach has been developed with municipal governments with various services being made available through locations across Chile’s 350 municipal governments.

Having integrated with the ChileAtiende call centre (in terms of enquiries being re-routed) the ambition is that the relationship between the Ministry and ChileAtiende would develop along the same lines as the provision of municipal governments and see requests for information and transactions handled by ChileAtiende.

National Consumer Service (Servicio Nacional del Consumidor, SERNAC)

SERNAC operates its own call centre, 16 physical locations and website (including a chatbot and click to call functionality). In addition to their own physical locations, they have co-located offices with 200 municipalities and are increasing their coverage through an alliance with ChileAtiende.

The nature of the service SERNAC provides (in providing support to consumers) means that the organisation is aware of the importance of putting users at the heart of what they do to ensure their needs are met. As such, their ambition is that it should not matter which channel is used or the provider so long as the necessary information can be exchanged to simplify the eventual outcome.

Like the Ministry of Social Development and Family, SERNAC has developed strong working relationships with municipal governments and encouraging them to adopt a consumer focus to their efforts in order to bring services closer to the citizen. It is better for everyone if the municipalities are able to resolve issues as close to where the citizen is based as possible.

350+ municipal governments

Although the Ministry of Social Development and Family and SERNAC have developed mechanisms for providing services through municipal government the local and regional service delivery experience is not one that has been the focus of the ChileAtiende project other than to highlight that each municipality provides a local face to face, telephone and sometimes also web based approach to accessing services.

References

[5] Cámara de Diputados (2013), Establece un sistema de atención a las personas y Crea el Servicio Nacional de Atención Ciudadana, Chileatiende., https://www.camara.cl/pley/pley_detalle.aspx?prmID=9536&prmBL=9125-06.

[2] Canada.ca (2019), Improving services for Canadians, https://www.canada.ca/en/employment-social-development/corporate/portfolio/service-canada/improving-services.html.

[1] Canada.ca (2019), Service Canada Programs and Services, https://www.canada.ca/en/employment-social-development/corporate/portfolio/service-canada/programs.html.

[9] División de Gobierno Digital (2019), Estrategia de Transformación Digital del Estado.

[7] Gobierno de Chile (2019), Agenda de Modernización del Estado.

[4] Laboratorio de Gobierno (2016), La nueva relación entre Estado y ciudadanos a través de ChileAtiende.

[3] Ministerio de Hacienda (2018), Presentación Nueva Institucionalidad ChileAtiende.

[8] MINSEGPRES (2019), Ley 21.180 de Transformación Digital del Estado, https://www.leychile.cl/Navegar?idNorma=1138479 (accessed on 12 December 2019).

[6] OECD (2016), Digital Government in Chile: Strengthening the Institutional and Governance Framework, OECD Digital Government Studies, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264258013-en.

Notes

← 1. Figures throughout this section are unpublished but provided during the OECD mission to Chile in January 2019.

← 2. This is according to an independent citizen satisfaction assessment that is used to gauge satisfaction with 80% of all citizen services.

← 3. Figures throughout this section are unpublished but provided during the OECD mission to Chile in January 2019.

Metadata, Legal and Rights

https://doi.org/10.1787/b94582e8-en

© OECD 2020

The use of this work, whether digital or print, is governed by the Terms and Conditions to be found at http://www.oecd.org/termsandconditions.