Chapter 2. Financial incentives to address barriers to adult learning

This chapter discusses the main barriers to participation in and provision of adult learning reported by individuals and firms in Australia. If well-designed, financial incentives can help individuals and firms to overcome barriers related to cost and time, thus promoting greater engagement in adult learning. Six types of financial incentives are presented – individual learning accounts, training leave, training vouchers, subsidised training programmes, training levies, and tax incentives – along with examples of how they have been implemented in Australia and in other countries.

The statistical data for Israel are supplied by and under the responsibility of the relevant Israeli authorities. The use of such data by the OECD is without prejudice to the status of the Golan Heights, East Jerusalem and Israeli settlements in the West Bank under the terms of international law.

2.1. Key findings

The set of financial incentives that will be most effective at supporting broad and inclusive participation in adult learning in Australia depends on the barriers that individuals and firms face. This chapter first discusses the main barriers to participation in adult learning reported by individuals and firms in Australia. It then presents six types of financial incentives that have been used previously in Australia or introduced in other countries and discusses the advantages and disadvantages of each.

The key findings from this chapter include:

-

Low willingness to train is by far the most significant barrier to adult learning for individuals. Among those who reported that there were learning opportunities that they would be willing to participate in, the most commonly-reported barriers were lack of time, followed by cost.

-

Among under-represented groups, own-account workers were more likely to cite being too busy at work as a barrier, while lack of time due to childcare or family responsibilities were cited as larger-than-average constraints for the unemployed, those out of the labour force, and part-time workers. Cost was the most commonly-reported barrier for the unemployed.

-

Cost and the time employees spend away from work were the two most important barriers that employers reported to providing more training.

-

Five of the six financial incentives discussed in this chapter address financial barriers to participating in adult learning: training vouchers, subsidised training programmes, and tax incentives reduce the cost of training for individuals and employers; while individual learning accounts and training levies provide a mechanism to set aside money to fund current or future training. Training leave addresses the barrier of time constraints, by reducing the opportunity costs of participating in adult learning.

The chapter is structured as follows. Section 2.2 analyses the barriers to greater engagement in adult learning among adults and firms in Australia. Section 2.3 presents financial incentives to address barriers to participation, with examples from Australian and international experience.

2.2. Barriers to adult learning participation in Australia

Both individuals and firms benefit from investments in adult learning. By helping to address skills imbalances, adult learning contributes to firm competitiveness and success in national and global markets. For individuals, participating in adult learning improves employability and capacity to adapt to changing skills needs.

However, both individuals and firms face barriers which prevent an optimal and timely investment in adult learning. Identifying these barriers and their relative importance for different types of adults and firms helps to assess which types of policy interventions are most appropriate, and how to design them.

2.2.1. Barriers for individuals

By far, the greatest barrier to participation in adult learning in Australia as in other countries is low willingness to train: among adults aged 25-64 who did not participate in any formal or non-formal training activity in 2012, only 24% reported that there were learning opportunities that they would have wanted to take up, but could not (PIAAC). More recent results from the ABS’ WRTAL survey which focuses on participation in non-formal learning show similar results: only 9% of non-participants reported that they had wanted to participate in training in 2017, but could not.

Many reasons could explain why so many adults have low willingness to train, including a lack of understanding of the returns from training, the poor quality of the training available, negative attitudes towards learning, or the perception that existing barriers to participation are unsurmountable. Psychological biases may also play a role, including the myopic tendency to focus on current income and job stability while discounting potential future periods of reduced income and job instability (Productivity Commission, 2017[1]). As the demand for skills changes gradually, workers in occupations with a high risk of automation may have no trigger for acquiring new skills before the risks are realised. There may also be a tendency to stick to the status quo out of a fear of change (Wood, 2014[2]; Productivity Commission, 2017[1]). Low self-confidence may also limit workers’ willingness to engage in training, perhaps especially for unemployed adults or older workers who are overwhelmed at the prospect of retraining in unfamiliar technological contexts or embarrassed about their out-of-date skills given the length of time since they completed initial education.

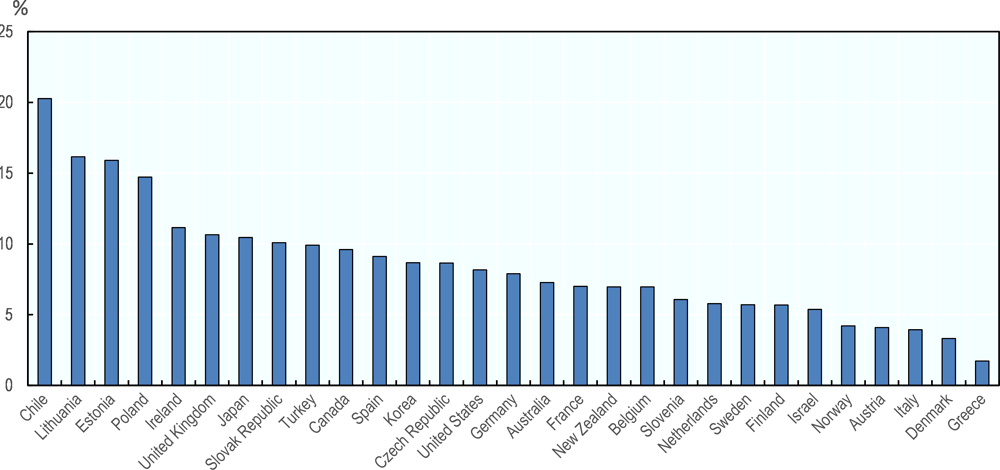

For some adults, low willingness to train may stem from a perception that returns to further training are low. A recent OECD working paper (Fialho, Quintini and Vandeweyer, 2019[3]) computes returns to job-related adult learning (either formal or non-formal) by country. In Australia, adults who participate in job-related adult learning have wage returns of 7% compared to those who do not, just below the international average (8.5%). Heterogeneity in returns to training across countries can be explained by a variety of factors, including how well employers recognise the value of training and the wage structure (Acemoglu and Pischke, 1998[4]). An Australian analysis exploiting the longitudinal nature of the HILDA survey to control for unobservable ability bias (Coelli and Tabasso, 2015[5]) estimates the returns to formal training (i.e. certified courses undertaken by adults while in paid work - not including initial education). It finds little evidence that formal training for Australian adults leads to significant improvements in standard labour market outcomes of employment, hours of work or wage rates; though it finds evidence of improved levels of job satisfaction and satisfaction with employment opportunities, particularly among women. These findings do not negate the fact, however, that adults with higher levels of educational attainment have more favourable labour market outcomes than those with lower levels of educational attainment1. For job seekers, returns to training are positive, but only in the medium term. A recent meta-analysis of active labour market programmes (Card, Kluve and Weber, 2017[6]) find that classroom and on-the-job training programmes for the unemployed have a positive impact in the medium term (after two years) in terms of employment effects, although the short term impact is insignificant or even negative due to “lock-in effects” (i.e. training participants suspend job search effort while training).

Compared to other OECD countries, adults with a tertiary degree have a lower willingness to train in Australia: only 23% of adults with a tertiary education in Australia are willing to train, compared with 34% across OECD countries. Australian adults with a tertiary education may have low willingness to train if they believe that having a qualification is sufficient for lifetime employability. In Australia, 45% of the population aged 25-64 has a tertiary education qualification, putting Australia among the top third of OECD countries (OECD average is 37%). About 20% of workers are over-qualified for their jobs (OECD, 2018[7]), which may reduce motivation to train further. OECD analysis, however, finds that the returns to non-formal learning rise with educational attainment and are highest for those with a tertiary qualification (Fialho, Quintini and Vandeweyer, 2019[3]). Workers with a tertiary qualification may be unaware of the potential benefits of non-formal learning, having participated predominantly in formal training.

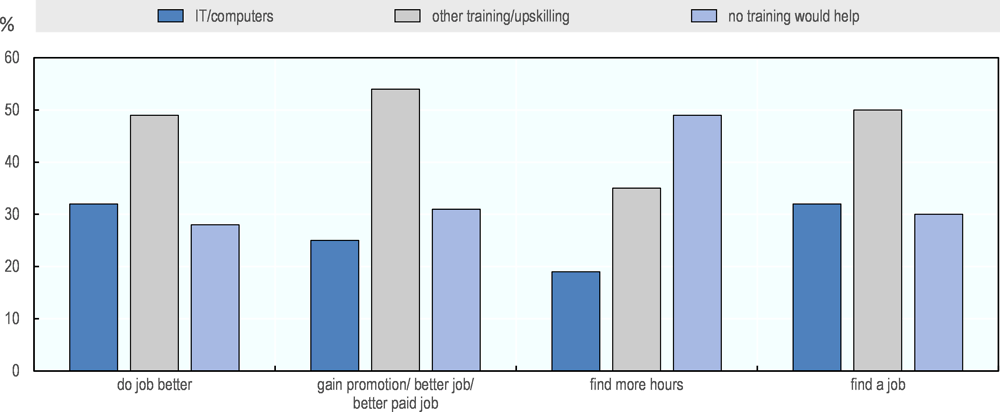

Since older workers have less time before retirement to recoup their investment, they may assess their returns to training to be low which may reduce their willingness to train. Indeed, according to the 2011-12 Survey of Barriers to Employment for Mature Age Australians (Figure 2.2), nearly a third of respondents (age 45 and over) reported that work-related training would not help them to do their job better (28%), find a job (30%), or gain a promotion or find a better paying job (31%).

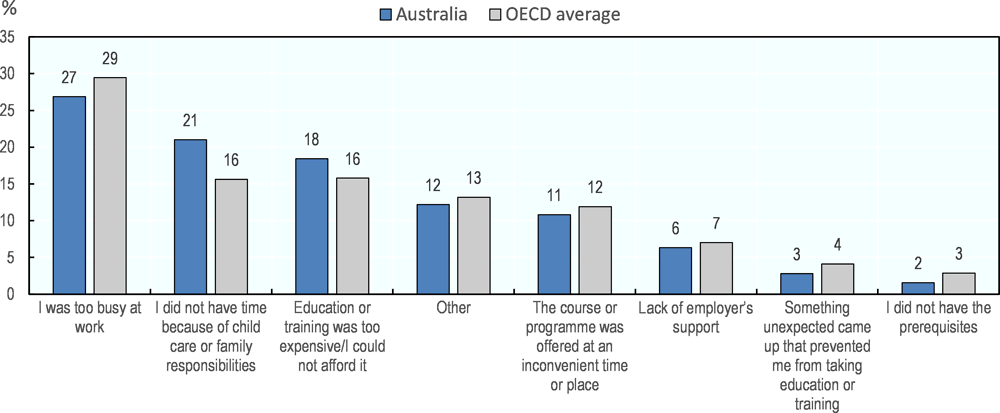

Among adults who did not participate in adult learning but would have liked to, the main barrier cited in the 2012 Survey of Adult Skills was being too busy at work (27%), followed by lack of time due to child care or family responsibilities (21%), and then cost (18%) (Figure 2.3). This ranking is similar to the OECD average, though cost and not having time due to child care or family responsibilities are more important barriers in Australia compared to the OECD average (Figure 2.3). This ranking is also generally consistent with 2017 findings from the ABS’ WRTAL survey relating to barriers to participation in non-formal learning: adults report that the main barriers are having too much work or no time (39%), followed by cost (28%), and followed by personal reasons (16%).

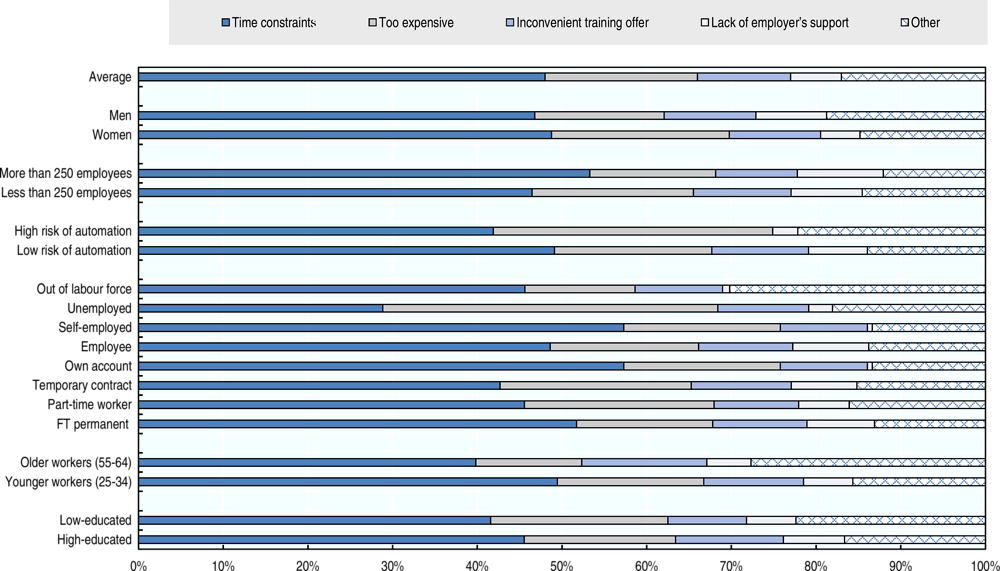

Some groups were more likely than the average to report being too busy at work as a barrier: full-time permanent workers (40%), workers in large firms (38%), own-account workers (37%), and older adults (30%). Childcare or family responsibilities were cited as major time constraints for unemployed workers (27%), those out of the labour force (40%), as well as part-time workers (31%). Women were three times more likely than men to report not having time because of childcare or family responsibilities (30% versus 10%), while men were nearly twice as likely as women to report being too busy at work (37% versus 19%). Workers in occupations with a high risk of automation were less likely to report time constraints as a barrier than workers in occupations with a low risk of automation. This may be explained by differences in working hours: on average, workers in high-risk occupations work two hours less each week than those in low-risk occupations (35.6 hours versus 37.8 hours, according to PIAAC).

Very closely related to time constraints, 11% of adults who did not participate in adult learning but would have liked to report that the course or programme they were interested in was offered at an inconvenient time or place.

While cost was not the most important barrier for the average adult, cost was the single most important barrier for the unemployed (40%) (Figure 2.4). The fact that the unemployed report cost to be the most important barrier to participating in training reflects that Australia has one of the lowest expenditures on training for the unemployed across OECD countries (0.01% of GDP compared to the OECD average of 0.13% in 2016) (OECD, 2019[10]), and that few jobactive participants receive training (only 12.3% of active jobactive participants had commenced any education or training activity in October 2017, based on administrative records from the Department of Jobs and Small Business, OECD (2018[7])). Other groups also reported cost to be more important than depicted by the average: part-time workers (22%) temporary workers (23%), low-educated workers (21%), and workers in occupations with a high risk of automation (23%).

Given the public and private benefits to adult learning, costs are generally shared between employers, individuals and the government. Evidence from the Survey of Adult Skills finds that 17% of adults who participated in job-related non-formal learning activities in Australia contributed to the cost of training, compared to 21% across OECD countries on average. Own-account workers, part-time workers and those on a temporary contract are more likely than workers on a permanent contract to contribute to the cost of job-related training, according to the HILDA. Only 6% of permanent workers contributed to the costs of job-related training in 2017 versus 11% of own-account workers, 10% of employees on a fixed-term contract, 9% of part-time workers, and 8% of casual workers. According to the Survey of Adult Skills, nearly 80% of adults who participated in job-related training received funding from their employer for at least one learning activity, just above the OECD average (78% versus 77%). About 22% of workers reported that their employer had given them paid leave to complete their training, thus covering the opportunity cost of training. But this was more common for permanent workers than for own-account workers or those working on a part-time basis.2

2.2.2. Barriers for firms

According to the NCVER’s Survey of Employers’ Use and Views (SEUV), 60% of employers want to provide more training for their employees, with the most common barriers to providing more training being financial constraints (38%), employees being too busy to be trained (19%), and managers not having the time to organise training (14%) (Smith et al., 2017[11]). There are three dimensions to financial constraints for employers: the direct cost of training workers (i.e. training fees), indirect costs associated with training (e.g. transportation), and possibly most important, opportunity costs that come from lost wages and productive effort while the employee trains rather than works. Indeed, TAFE Enterprise (2018[12]) found that the most common barrier cited by employers was the time employees were required to spend away from work (74%), followed by cost (54%), and the inability to motivate staff to take part (46%). Releasing employees for training may be particularly costly for small firms with few employees as the firm’s productivity may be strongly affected if employees are absent.

An older report by the Australian Industry Group (AIG, 2008[13])3 identified barriers that prevent firms from increasing the skills of their workforce to required levels. The most common barrier cited was cost (52%). Related to the cost issue, 41% of firms reported they were concerned that staff might depart following training, and 36% cited a lack of government incentives.

Considerations about cost influence not only the decision about whether to provide training, but also the type of training employers choose to provide. Based on NCVER’s SEUV, cost effectiveness was the top reason cited by employers who used unaccredited training in 2017 rather than nationally-recognised training (Table 2.1). After cost-effectiveness (37% of respondents), unaccredited training was also viewed to be better tailored to the needs of employers (26%) and available at more convenient and flexible times (21%). Firms that chose unaccredited training over nationally-recognised training tend to be small or medium-sized, with many casual workers (Smith, Oczkowski and Hill, 2009[14]).

Between 2007 and 2017, there was a large increase in the share of employers citing “approach that was tailored to our needs” as the reason they chose unaccredited training over comparable nationally-recognised training, possibly suggesting that this has become more important to employers over recent years. The share of employers who reported cost-effectiveness as a reason for choosing unaccredited training over nationally-recognised training also increased during this period, and briefly spiked to 50% in 2015, then back to 37% in 2017 (Table 2.1). The temporary spike in the share of firms reporting cost-effectiveness of unaccredited training as a reason coincides with the short period during which the Industry Skills Fund (which subsidised both unaccredited and accredited training) was in place4.

2.3. Financial incentives to address barriers to participation in adult learning

The previous section displayed evidence that the high cost of training is one (though not the only) barrier to participation in adult learning. High cost of training could be one of the reasons for the observed declines in provision by employers and in participation by adults, as the generosity of financial incentives declined since 2012.

Well-designed and appropriately targeted financial incentives can be useful tools for raising incentives of individuals and firms to engage in training by reducing costs associated with financial and time constraints. Many countries employ financial incentives to reduce the financial burden on individuals and employers in adult learning, to encourage their participation and contribution, and to reduce under-investment. Table 2.2 highlights some of the main financial incentives available to encourage engagement in adult learning, either by reducing the direct cost of learning (e.g. subsidies, tax incentives), tackling temporary liquidity constraints (e.g. loans), setting aside resources for future training (e.g. individual learning accounts, levies/funds), or reducing opportunity costs of learning (e.g. paid training leave, job rotation).

This section discusses international experiences with individual learning accounts, training leave, training vouchers, subsidised training programmes, training levies, and tax incentives. When applicable, it also reviews Australian experiences. While this section assesses advantages and disadvantages of each financial incentive separately, it is worth keeping in mind that schemes to promote engagement in adult learning can and often do involve a package of financial incentives, rather than a single incentive in isolation.

2.3.1. Individual learning accounts5

An individual learning account (ILA) is a type of subsidy scheme that attaches training rights to individuals (rather than to employers or jobs) to fund current or future education and training activities. They can be tax-sheltered savings accounts opened by individuals for the purpose of funding current and future learning activities. More often, however, they are voucher-based schemes which preserve use of the term ILA.

Emerging in the late 1990s, the original philosophy underlying these initiatives was to empower individuals in education and training markets by encouraging them to take responsibility for their own education and training choices (OECD, 2017[18]). The key design feature of ILAs, and the reason they have attracted renewed interest, is that they make training rights portable from job to job and from one employment status to another. This is particularly important in the context of changing labour markets and skills needs. Since training rights are attached to the individual and not the employer, the individual can use the ILA to retrain in a new occupation. The portability feature also broadens training rights to workers who have limited attachment to their employment, including those in non-standard working arrangements.

If not carefully designed, ILAs are more likely to be used by high-skilled workers than low-skilled ones, potentially exacerbating inequality in skills outcomes (OECD, 2017[18]) and producing deadweight loss which arise from the fact that some beneficiaries would have participated in training even in the absence of the scheme. In France, employees with a tertiary education were over-represented in their use of the Compte personnel de formation (Individual Training Account – CPF) (accounting for 56% of validated CPF files over the 2015-2018 period, while representing only 38% of the 2016 labour force). Employees with less than upper-secondary education were under-represented (accounting for only 26% of validated CFP files, despite representing 42% of the 2016 labour force). Some OECD countries have tried to overcome this challenge by granting more training rights to low-skilled or other disadvantaged individuals. For example, France’s CPF grants low-qualified workers EUR 800 (euros) per year for training compared to EUR 500 for other workers. It is too early to say whether this approach delivers in terms of reducing inequality. Restricting access to some groups is another way to reduce deadweight loss, but this reduces the portability of ILAs.

ILAs generally only cover tuition fees associated with training, and do not cover indirect costs (e.g. child care expenses, transportation costs) or opportunity costs (i.e. wage costs for the time spent off work). This means that on their own, ILAs are unable to address time constraints that prevent adults from participating in adult learning. Some countries offer paid education and training leave which supports the use of the ILA by covering opportunity costs. For instance, the French CPF can be used in tandem with the Congé Individuel de Formation (Personal Training Leave - CIF), which gives adults the right to up to one year of training leave with 80-100% of their salary replaced. Similarly, in Flanders (Belgium) the use of training vouchers (Opleidingscheques) can be used along with up to 180 hours of paid education leave (Betaald Educatief Verlof), with the maximum 180 hours reserved for vocational training in shortage occupations or for obtaining a first secondary education degree (OECD, 2019[19]). When users of Singapore’s SkillsFuture Credit undertake training in Workforce Skills Qualifications, both the learner and the employer are eligible for absentee payroll compensation. The next section discusses training leave in more detail.

Singapore’s SkillsFuture Credit (SFC) was introduced in 2015 to shift focus on adult learning from a workplace-centred approach to one that encourages individuals to initiate their own training. Every adult aged 25+ receives an annual SGD 500 (Singapore dollars) credit which can be used for eligible skills-related courses. It is a lifetime credit and works like a voucher, in that the government pays the tuition fee (up to a maximum of SGD 500) to the provider once the learner enrols in a course. The MySkillsFuture portal showcases all approved courses that can be subsidised with the SFC and allows users to register directly online, and keeps them informed about how much remains in their account.

The SFC is offered on top of an already generous set of incentives for adult learning in Singapore, including Workforce Skills Qualifications (WSQ), which are available to all individuals with 50% to 90% of course fees subsidised. Adults can use the SFC to pay for remaining course fees that are not already subsidised through WSQ. Alternatively, adults can use the SFC towards other approved courses, including selected massive open online courses (MOOCs). When used in conjunction with subsidies for WSQ, both individuals and employers receive “absentee payroll” compensation.

France’s Compte personnel de formation (CPF) credits each worker age 16+ who has a qualification with EUR 500 per year for training, while those without a qualification receive EUR 800 (up to a limit of EUR 5 000 and 8 000, respectively). The account is rechargeable, and starts to be credited again each time use of the account brings the total credit below a minimum threshold. The self-employed have been eligible for the CPF since 2018. Training credits are transferrable between employers and preserved upon job loss. They can be applied towards training in recognised qualifications or basic skills. If the employer agrees, training can take place during working time. If the credit does not suffice to cover the overall training costs, employers or training funds can provide complementary funding.

Reforms that were implemented in January 2019 converted the CPF from a time account (where each full-time worker was entitled to 24 hours of training per year, and those without qualifications were entitled to 48 hours per year) to the current money account.

Quality control requires careful consideration under an ILA scheme, as public entities no longer have a contractual relationship with the training providers that would allow them to put in place incentives for quality or performance (OECD, forthcoming). Users of Singapore’s SFC reported experiences of MOOC providers trying to “upsell” adults by encouraging them to make batch purchases of courses (e.g. buy five courses for the price of one, given the subsidy), even if one course would be sufficient to meet the learner’s training needs and the learner would not have time to pursue multiple courses (OECD, forthcoming). The United Kingdom’s experience with ILAs from 2000-01 ended abruptly due to several instances of fraud that arose due to a lack of monitoring and quality assurance systems, poorly informed learners, and a hurried implementation (Box 2.2).

In Australia, public sentiment towards demand-driven training entitlements is wary given recent experiences with fraud in the VET sector. An inquiry into the VET FEE-HELP programme (which was introduced in 2008 and expanded in 2012) concluded that the extension of the Australian Government’s income-contingent loans to VET courses resulted in many private providers entering the market. A limited number of these private providers engaged in misconduct, including use of high-pressure marketing techniques to increase enrolment (e.g. offering iPads or cash bonuses in exchange for enrolment) (Senate Standing Committee on Education and Employment, 2015[20]). The committee also noted a trend of rising fees for VET FEE-HELP eligible courses, as access to the loan scheme enabled students to pay more, which in turn allowed providers to charge more knowing that the Australian Government was ultimately responsible for the loan. The committee noted that there has been “a massive transfer of public wealth from the Commonwealth and state government – and taxpayers – to private individuals as a result of rushed rollout of demand driven entitlement schemes…”

The Scottish and Welsh experiences with voucher-based ILAs suggest that minimising fraudulent use of the learning account is possible with stringent vetting of training providers and quality assurance of eligible courses (Johnson et al., 2010[21]). Such monitoring and quality assurance systems can entail substantial costs, particularly if a country has a large number of training providers, as is the case in Australia6. France’s approach to assessing training providers may help to keep these costs low. In France, training providers can establish that they meet quality criteria required for working with public institutions by registering with the online Data Dock platform (www.data-dock.fr/), and providing supporting documents to justify their self-assessment. Australia has taken steps to improve quality assurance in its national VET sector. In a quality review commissioned after the VET FEE-HELP experience (Braithwaite, 2018[22]), the author recommends that the VET sector would benefit from greater and more timely access to provider-level NCVER data and more stringent standards for gaining and maintaining registration as a VET provider.

As it is the responsibility of individuals to decide what training to take and where, whether ILAs function well depends on having strong systems of information, including on provider quality. Lack of precise information about labour market needs and provider quality can jeopardize the programme’s success and lead to a poor use of public resources. In some countries, quality assurance bodies make the results from evaluations publicly available. In Norway, Skills Plus makes the results from inspections of Skills Plus programmes and adult training in study associations available on its website. In countries that make use of self-evaluation systems it is compulsory to make the results from internal evaluations publicly available, as is the case in Brazil with e-Tec programmes, and in Denmark, through the national VisKvalitet tool. Online databases that provide details on existing training programmes can also help individuals make informed training decisions. Australia’s national directory of vocational education and training providers and courses (www.myskills.gov.au) allows users to search VET qualifications by industry and to compare training providers on the basis of location, course fees and course duration. There is also a plan to make employment outcomes by qualification and training provider available, which would help adults make informed training investment decisions (OECD, 2019[16]).

In the United Kingdom, ILAs were announced in the 1999 budget law and officially launched in 2000. By 2001, around 8 500 training providers were accredited nationwide when the Department for Education and Skills started investigations related to illicit use of the ILAs. The fraudulent activity was based on collusion between learners and training providers, where learners would allow training providers to buy their learning account numbers without any training taking place. Some providers offered potential learners a computer at no cost as an additional incentive to participate in fraudulent activity. Following its investigation, the Parliamentary Committee of Public Accounts reported that the total expenditure on the scheme exceeded GBP 290 million with fraud and abuse amounting to GBP 97 million.

The committee that examined the level of fraud and abuse and the actions taken drew several conclusions:

-

While the government undertook extensive piloting, these pilots did not provide workable solutions. Rather than re-plan the project, the government went ahead with a scheme that was not well thought through or tested and which was implemented in too short a time frame.

-

The government ignored advice from the pilots that the scheme was most likely to be successful where new learners had advice from intermediaries such as community groups and trades unions. Research suggests that instead, 45% of account holders first heard of the scheme from providers and many courses were not appropriate to learners’ needs.

-

To encourage new providers and new learners, the government decided to minimise bureaucracy, including checks on learners, providers and on the quality of learning. As this was not combined with rigorous monitoring downstream, the government was slow to identify emerging problems, including substantial fraud and abuse.

Source: Select Committee on Public Accounts (n.d.[23]), “Tenth Report”, https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm200203/cmselect/cmpubacc/544/54403.htm.

2.3.2. Training leave

Education and training leave gives adults time away from work to participate in learning, which addresses the most commonly-reported barrier to participation in adult learning, i.e. time constraints. Training leave can be paid or unpaid. During paid training leave, the learner continues to receive part or all of their salary while studying. Under unpaid training leave, the learner is guaranteed a return to their position once their leave is over and they retain their entitlement to health insurance and pension rights while on leave. Education and training leaves are typically regulated by legislation or by collective agreements. Australia is one of only a handful of OECD countries that does not grant education and training leave [Table 2.4 in OECD (2019[16])], though some employers have their own bi-laterally agreed leave arrangements. Evidence from the HILDA survey suggests that 22% of Australian adult workers receive paid leave from their employer to complete their job-related training, but permanent workers are more likely to receive paid leave than casual or own-account workers.

Training leave may be universal or provided only to certain workers, e.g. those with a minimum tenure in the company. Paid training leave may be limited to use with a particular employer, or may be portable from employer to employer and/or from one employment status to another. In Luxembourg, for example, all employees and self-employed people (including own-account workers) can access up to 80 days of paid training leave over the course of their career, and a maximum of 20 days every two years. Under Canada’s recently proposed Canada Training Benefit (CTB), workers need to accumulate 600 hours of insurable employment (i.e. paying Employment Insurance contributions) to be eligible for 4 weeks of paid training leave every four years (Box 2.3). CTB leave accounts are centrally managed by the Canada Revenue Agency, which supports the portability of the training leave from employer to employer, and from one employment status to another.

Canada recently announced plans for a new financial incentive to support adult training and proposed to invest CAD 1.7 billion in this new incentive over five years, starting in 2019-20. The benefit has three distinct but related components for learners. First, an annual CAD 250 (Canadian dollars) training credit for every adult aged 25-64 (subject to a lifetime limit of CAD 5 000) which can be used to refund up to half of the costs of training fees and works like a voucher. Second, a training support benefit for up to four weeks of paid leave every four years at 55% of average weekly earnings to cover living expenses, such as rent, utilities and groceries. Third, leave provisions to protect federally-regulated workers’ jobs while on training and receiving the training support benefit. The training credit is financed by public funds, while the training support benefit would be drawn from Employment Insurance (EI), which is comprised of mandatory employer and employee contributions. Some restrictions apply. The training credit is only eligible to workers who earn between CAD 10 000 and 150 000 from work, and who file a tax return. To be eligible for the training support benefit, workers need to accumulate 600 hours of insurable employment (i.e. paying EI contributions).

Source: www.budget.gc.ca/2019/docs/themes/good-jobs-de-bons-emplois-en.pdf.

A review of training leave practices in European countries found that in most cases, workers must obtain their employer’s permission to use training leave (Cedefop, 2012[24]). Requiring an employer’s permission may be a barrier in itself, since it implicitly confines the worker to training that is relevant to their current employment and prevents them from training for a new occupation. There are some exceptions. In Flanders (Belgium), employers cannot refuse a request for education and training leave, but the worker and employer must agree upon a timeline for the training. In France the employer can only deny or postpone a request for paid training leave under certain circumstances: i) the employee has not met the job tenure requirement, ii) the employee did not make the request early enough in advance (i.e. 60 days for training of six months or 120 days for training of more than six months), or iii) not enough time has elapsed since the employee was last granted training leave. If one of these conditions are satisfied, the employer can postpone granting the leave by up to nine months, but cannot refuse the request. Still, many CIF requests are ultimately denied by public institutions due to lack of resources (OECD, 2017[25]).

In some countries, employers can be reimbursed for wage payments and related social security contributions by the state during training leave. Singapore, for instance, provides employers with “absentee payroll” compensation for the period during which their employee trains in Workforce Skills Qualifications (Box 2.1). Similarly, in Flanders (Belgium), the government compensates employers the wage cost up to a maximum of 1.8 times the minimum wage during the employee’s paid education leave. While compensating employers for lost wages helps to reduce opportunity costs, feedback from countries where this is practiced suggests that wage compensation may not be sufficient, particularly for SMEs (OECD, 2019[19]). Stakeholders in Flanders reported that SMEs may find it difficult to plan and cover absences while their employees are training, as even a few employee absences can have a significant impact on production. In some OECD countries, including Denmark (Box 2.4), Finland and Portugal, job rotation schemes provide the employer with temporary replacement (usually an unemployed worker) for the employee during their training. This not only reduces opportunity costs for the employer related to releasing their employee to train, but it also provides work experience and training opportunities for job seekers.

Job rotation was first introduced in Denmark in the 1980s and allows a firm to send its workers on training while a job seeker covers for him or her. At their high point, there were 80 000 full-time participants in job rotation schemes, but as unemployment levels fell during the 1990s the schemes were gradually rolled back. Today there are around 1 100 full-time participants. Under the scheme, employers receive a hiring subsidy for every hour an employee is on training and an unemployed person is employed as a substitute. The replacement person is provided by the local job centre and receives wages from the employer. Costs are shared equally between the municipality and the national government (EUR 23.4 million in 2012). The job seeker often receives training (a few weeks or longer) in order to fill vacant jobs. A recent Danish evaluation focused on the effects on the unemployed: job rotation made participants enter into regular employment two to three weeks faster than otherwise, and income and employment effects are strongest for low-skilled job seekers. Job rotation is dependent on close cooperation between a business and the job centre in order to find good skill matches for job rotation replacements.

Source: Masden (2015[26]), “Upskilling unemployed adults. The organisation, profiling and targeting of training provision”; Kora (2018[27]), “Effects of being employed as a substitute in a job rotation project”, www.kora.dk.

2.3.3. Training vouchers and subsidised training places

Training vouchers and subsidised training places are both types of subsidies, but with important differences. Training vouchers are a type of subsidy in which the government pays the tuition fee to the training provider once the learner enrols in the course. Subsidised training places also involve the government paying the tuition fee to the training provider; however, this transaction takes place based on a prior contractual agreement to deliver specified education and training (e.g. Commonwealth Grant Scheme, VET subsidised places, and training provided through employment services). Such agreements often specify that the training provider will receive a certain amount of public funding per learner. Therefore, while both training vouchers and subsidised training places are “demand driven”, in that institutional funding follows learner enrolment, training vouchers give the learner more flexibility in deciding the type of training they undertake, and also create conditions for greater contestability between training providers by reducing entry barriers.

Both types of financial incentives can be targeted relatively easily at vulnerable groups, thus mitigating deadweight loss. In Australia, subsidised training places offered through employment services are targeted at job seekers who are in receipt of income support payments, and often more narrowly at job seekers with particular characteristics (e.g. parents, low-skilled, older workers, etc.). In countries that employ vouchers, access is often based on characteristics such as age, employment status, skills, income and wealth. For example, Flanders limited use of training vouchers to adults without a tertiary degree in 2015, after an evaluation revealed that almost half of beneficiaries were highly-educated adults and that lower-educated adults were under-represented.

With subsidised training places, there is considerable scope for governments to steer training content to skills in high demand or in low supply in the labour market. For instance, subsidised training places offered through employment services (e.g. Skills for Education and Employment, the Employment Fund, New Enterprise Incentive Scheme, ParentsNext, etc.) are all well targeted at portable skills for general employability or skills and training required by employers.

With training vouchers, the learner has more flexibility in deciding the type of training they undertake, but measures to steer the use of vouchers can still be employed. Some countries link the delivery of vouchers to the outcomes of career counselling. In Korea, for example, unemployed individuals receive advice before they can access the Vocational Competency Development Account. Similarly, in Australia, older adults at risk of unemployment can access public funding for training, but must first participate in a Skills Checkpoint assessment to identify suitable training linked either to skills upgrading, a future job opportunity, or an industry, occupation or skill in demand. In Flanders, vouchers are available both for training and for career guidance (Box 2.5), and the two are linked: adults who already have a tertiary qualification may only access training vouchers if the career counsellor assesses that training is needed. Another measure that some countries use is to restrict use of vouchers to a list of pre-approved training courses that are in line with labour market needs. In Estonia and Latvia, vouchers can only be used by individuals who enrol in training that has been identified to develop skills that are in shortage in the labour market (OECD, 2019[16]). In Austria and Greece, vouchers are available for both the employed and the unemployed to develop digital skills while in Israel vouchers must be used to develop skills such as Real-Time, Java, or Application Development. In Flanders, vouchers must be applied to courses that are labour market oriented (Box 2.5).

While greater targeting of vouchers helps to minimize deadweight loss and helps individuals gain the skills needed in the labour market, its benefit must be weighed against greater administrative cost. Feedback from the experience of the Walloon (Belgium) Chèque Formation (a voucher that was targeted at the development of ‘green’ and language skills), for example, suggests that this targeting can create significant administrative burden (OECD, 2017[18]).

With vouchers, issues around quality control primarily concern contractual relationships with training providers. As discussed above with ILAs, stringent vetting of training providers and quality assurance of eligible courses is needed to minimize the risk of fraudulent activity.

In Flanders (Belgium), adults can access vouchers for subsidised career guidance and training. Career guidance vouchers (loopbaancheques) help to inform use of the training voucher. Workers must pay EUR 40 per voucher, which entitles them to four hours of subsidised career guidance and they are eligible for two vouchers every six years.

Employees (including part-time and contract workers) can pay for recognised training or education programmes with training vouchers (opleidingscheques), which they purchase from the public employment service. The Flemish government covers 50% of the cost, with a maximum subsidy of EUR 125 per year. All employees are eligible for the training voucher, provided they do not yet have a tertiary qualification (however, those with a tertiary qualification can become eligible if a career counsellor assesses that they need training). Since 2011, the training vouchers may only be used towards training with a labour market orientation. A recent review found the rules for identifying “labour market oriented” courses to be too vague and as of September 2019 a single database will clarify which courses are eligible. Eligible courses will fall under one of three categories: basic skills (e.g. literacy, official languages, attainment of secondary qualification), job-specific skills (shortage occupations), and general labour market skills (e.g. communication, information and communication technology, teamwork, entrepreneurship, career management and social dialogue).

Source: OECD (2019[19]), “OECD Skills Strategy Flanders: Assessment and Recommendations.”

2.3.4. Training levies

Countries can encourage firms to set aside resources for future training via training levies, under which employers pay a (compulsory or voluntary) contribution to a pooled fund out of which training is financed. The primary advantage of a training levy is that it overcomes the free-riding problem that deters many employers from investing in training by pooling resources from employers and earmarking them for expenditure on training. By helping to overcome this market failure, training levies can promote higher levels of employer-sponsored training. They are also a relatively cheap way to increase investment in training from a public spending point of view. Levies also act as an automatic stabilizer by providing a steady flow of funding which prevents training from being linked to cyclical fluctuations.

However, there are several risks associated with levy schemes, including that they may be perceived by employers as nothing more than an additional tax, while at the same time removing employers’ autonomy about training investments. Australia’s experience with the Training Guarantee Scheme in the early 1990s demonstrates that without employer buy-in, levy schemes can lead to employers spending money on training without giving thought to their skills needs, resulting in low quality training outcomes. The Australian Training Guarantee required employers with a payroll above a certain threshold to contribute a minimum of 1.5% of their payroll to structured training (Fraser, 1996[28]). If employers did not contribute this amount to training, they were required to pay the shortfall as a charge. The scheme was suspended from July 1994 until June 1996 and formally ended in July 1996 (HIA, 2001[29]). Reasons given for abolishing the levy included that employers perceived the levy to be just another tax and funds were being spent on executive training, often with a recreational component (Department of the Parliamentary Library, 1994[30]). In Italy, much of the resources collected through training levies are used to finance compulsory health and safety training, which generates high deadweight losses by financing training that would have taken place in the absence of the levy (OECD, 2019[31]).

One way to achieve greater employer buy-in is to involve employers closely in the governance of levy schemes, including in decisions on training priorities and funding allocation (OECD, 2017[18]). Organising levy funds at the sectoral (or local) level promotes use of levy funds for training that meets the needs of employers in that sector (or geographical area), and can achieve efficiency gains by taking advantage of economies of scale. In Italy, for instance, the Fondi Inter professionali (Training Funds) were established with a national law but are managed by social partners (OECD, 2019[31]). One of the identified advantages of the Irish Skillnets model, a training levy organised at the sectoral level, is that it reduces the administrative costs of training, which is particularly relevant for SMEs (Marsden and Dickinson, 2013[32]).

Involving employers in decisions on training priorities and funding allocation has the additional advantage that training is more likely to meet specific labour market needs. A potential drawback, however, is that it could result in sub-optimal investment in portable skills and risk losing sight of national skills priorities, including support for vulnerable groups and support for transitions from one sector to another. A review of Australia’s training levy in the 1990s found that it had little impact on industries which had trained poorly before its introduction, and most training went to higher-educated and higher-skilled workers (Fraser, 1996[28]). Some countries design training levies to explicitly target vulnerable groups or to target specific training. Singapore’s Skills Development Fund was designed to target lower-income workers, under-educated individuals and SMEs (OECD, 2019[31]), and South Africa earmarks 40% of levy funds for use in accredited training that addresses scarce and critical national skills needs (OECD, 2017[33]). An alternative approach is to assign training rights to individuals, for instance via an ILA, while funding the account by an employer training levy. France’s CPF is funded in this way.

While restricting spending of training funds to national skills priorities helps to ensure that investments are well spent, an overly burdensome process for recouping training funds can also discourage their use, especially among smaller firms. In South Africa, for example, few firms recoup their skills training funds due to the cumbersome process involved in completing reports which demonstrate that their proposed training meets national skills priorities. Furthermore, while the cost of training levies is low from a public spending perspective, the administrative costs associated with setting up and managing levies can be considerable.

Some countries waive mandatory levy payments for SMEs, given their higher cost constraints. For instance, in the United Kingdom, SMEs are exempt from paying the apprenticeship levy. But while they do not pay into the levy fund, they are still able to access subsidies for apprenticeship training up to a designated funding band (OECD, 2017[34]).

2.3.5. Tax incentives

Tax incentives can encourage participation and contribution by individuals and employers in adult learning by reducing costs associated with education and training, similar to subsidies. Tax incentives aimed at individuals can be tax allowances (i.e. deductions from taxable income) or tax credits (sums deducted from the tax due). At the firm level, a range of measures are possible, including tax allowances, tax credits, tax exemptions, tax relief and tax deferrals. Reductions or exemptions in social security contributions7 are also used to encourage employers’ investments in training.

Tax incentives have a number of advantages over other types of financial incentives. Administrative costs of delivering the programme are generally low because countries can leverage the existing tax infrastructure. Since they are part of the annual tax return process and do not require the recipient to file a separate application, awareness and take-up of tax incentives may also be higher among individuals than other types of financial incentives.

However, tax incentives can be harder to target compared to other financial incentives and therefore carry higher deadweight loss as they often favour groups who already have the best access to education and training. In the Netherlands, the tax deduction (aftrekpost scholingsuitgaven) was used primarily by highly-skilled individuals and had a very high deadweight cost, leading to a decision to move away from tax incentives in favour of direct subsidies (OECD, 2017[18]). Since individuals must generally wait until after the end of the tax year to claim compensation, tax incentives fail to reduce liquidity constraints which may prevent access by lower-income individuals and smaller firms. Further, tax incentives can only reach workers, leaving out vulnerable groups such as the unemployed and inactive workers. Low-income workers benefit little or not at all from tax incentives in countries with a progressive tax system, as the amount of tax they must pay is already low. Similarly, young or struggling SMEs may not generate sufficient profits to make use of tax incentives.

A key limitation in the context of preparing workers for changing skills demands is that most tax allowances, including Australia’s tax deduction for self-education expenses, are only available when the training concerned is related to a workers’ current employment. Apart from being vague and difficult for tax authorities to monitor and regulate, this requirement prevents use of tax incentives for training that could allow individuals to change career or occupation. Exceptions are the Czech Republic and the Netherlands, where the tax incentive can be used to fund training that is not work-related. Germany and Austria (Box 2.6) also allow tax relief for individuals who pursue work-related professional training that prepares the individual for a change in occupation. In most cases, countries exclude training that is entirely leisure-related (OECD, 2017[18]).

Tax incentives that allow firms to cover the indirect costs of training can help firms to overcome one of their main barriers, i.e. the cost of releasing workers to train. Some tax incentives are designed to cover wage payments during training periods. For instance, Italy’s Tax Credit 4.0 (Credito di Imposta Formazione 4.0) covers 40% of labour costs for the entire duration of training up to a maximum of EUR 300 000 per firm per year. To be eligible for this support, firms must provide training in “Industry 4.0 skills”, including ICT.

In light of the advantages and disadvantages of the various financial incentives discussed above, Chapter 3 provides an analysis of Australia’s current set of financial incentives, and considers improvements that could be made to better address time and cost barriers. The chapter also reviews framework conditions that must be in place for financial incentives to work effectively.

In Austria, tax filers can deduct expenses related to training as part of a work-related expenses tax deduction (Werbungskosten). Such expenses are deductible both for education and training related to one’s current employment, as well as for training which would prepare the individual for a change in occupation.

Retraining costs are only deductible when the training is comprehensive enough to enable an individual to start working in a new occupation unrelated to their previous occupation, e.g. training a worker from the printing industry to be a nurse. This means that expenses for individual courses or course modules for an unrelated professional activity are not deductible as retraining costs. However, such expenses are deductible if they represent education or training costs relevant to the taxpayer’s current employment.

Eligible reasons for retraining are not strict and may include external circumstances (e.g. economic restructuring or plant closures), dissatisfaction in the occupation, or interest in professional reorientation. The taxpayer may be asked to prove, however, that he or she is pursuing retraining in order to take up another occupation. This is assumed to be the case if the tax filer no longer earns income in the previously practiced occupation, if future employment in the previous occupation is endangered, or if job or earning prospects can be improved by retraining.

Source: Austrian Ministry of Finance website (www.bmf.gv.at/steuern/arbeitnehmer-pensionisten/arbeitnehmerveranlagung/abc-der-werbungskosten.html)

References

[4] Acemoglu, D. and J. Pischke (1998), “The Structure of Wages and Investment in General Training”, NBER Working Paper, Vol. 6357, https://www.nber.org/papers/w6357.pdf (accessed on 13 May 2019).

[8] Adair, T. and J. Temple (2012), “Barriers to Mature Age Labour Force Engagement in Australia: Report on the 2011-12 National Survey on the Barriers to Employment for Mature Age People”, National Seniors Productive Ageing Centre, https://nationalseniors.com.au/uploads/201208_PACReport_Research_BarriersMatureAgeEmployment_Full_1.pdf (accessed on 4 April 2019).

[13] AIG (2008), “Skilling the existing workforce : final project report”, Australian Industry Group, Sydney, https://trove.nla.gov.au/work/31871780?q&versionId=44562895 (accessed on 11 April 2019).

[22] Braithwaite, V. (2018), “All eyes on quality: Review of the National Vocational Education and Training Regulator Act 2011 report”, Australian Government, Canberra, https://docs.education.gov.au/system/files/doc/other/all_eyes_on_quality_-_review_of_the_nvetr_act_2011_report.pdf.

[6] Card, D., J. Kluve and A. Weber (2017), “What Works? A Meta Analysis of Recent Active Labor Market Program Evaluations”, Journal of the European Economic Association, Vol. 16/3, pp. 894-931, https://doi.org/10.1093/jeea/jvx028.

[24] Cedefop (2012), “Training leave: Policies and practice in Europe”, European Centre for the Development of Vocational Training, Luxembourg, https://doi.org/10.2801/12416.

[5] Coelli, M. and D. Tabasso (2015), “Where Are the Returns to Lifelong Learning?”, Forschungsinstitut zur Zukunft der Arbeit Institute for the Study of Labor.

[30] Department of the Parliamentary Library (1994), “Training Guarantee (Suspension) Bill 1994”, Parliament of the Commonwealth of Australia, https://parlinfo.aph.gov.au/parlInfo/download/legislation/billsdgs/UDQ10/upload_binary/UDQ10.pdf;fileType=application%2Fpdf#search=%22legislation/billsdgs/UDQ10%22 (accessed on 22 March 2019).

[3] Fialho, P., G. Quintini and M. Vandeweyer (2019), “Returns to different forms of job related training: Factoring in informal learning”, OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Papers, No. 231, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/b21807e9-en.

[28] Fraser, D. (1996), “Training guarantee: its impact and legacy 1990-1994”, Department of Employment, Education, Training and Youth Affairs, http://hdl.handle.net/11343/115427.

[29] HIA (2001), “HIA Policy Training Levies”, National Policy Congress, https://hia.com.au/-/media/HIA-Website/Files/Media-Centre/Policies/training-levies.ashx (accessed on 22 March 2019).

[21] Johnson, S. et al. (2010), Personal Learning Accounts: Building on lessons learnt Personal Learning Accounts, UK Commission for Education and Skills.

[27] Kora (2018), Effekter af ansættelse som jobrotationsvikar [Effects of being employed as a substitute in a job-rotation project ], http://www.kora.dk/ (accessed on 27 November 2018).

[36] Korbel, P. and J. Misko (2016), Uptake and utility of VET qualifications, National Centre for Vocational Education and Research, Adelaide.

[26] Madsen, P. (2015), Upskilling unemployed adults.The organisation, profiling and targeting of training provision: Denmark., European Employment Policy Observatory, Luxembourg:, http://vbn.aau.dk/files/227968798/Denmark_Review_Upskilling_Mar2015_final.pdf.

[32] Marsden, J. and P. Dickinson (2013), “International Evidence Review on Co-funding for Training”, in BIS Research Paper number 116, Department for Business, Innovation and Skills, http://www.gov.uk/bis (accessed on 18 April 2019).

[9] Nedelkoska, L. and G. Quintini (2018), “Automation, skills use and training”, OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Papers, No. 202, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/2e2f4eea-en.

[31] OECD (2019), Adult Learning in Italy: What Role for Training Funds ?, Getting Skills Right, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264311978-en.

[16] OECD (2019), Getting Skills Right: Future-Ready Adult Learning Systems, Getting Skills Right, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264311756-en.

[10] OECD (2019), “Labour market programmes: expenditure and participants”, OECD Employment and Labour Market Statistics (database), https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/data-00312-en (accessed on 17 April 2019).

[19] OECD (2019), OECD Skills Strategy Flanders: Assessment and Recommendations, OECD Skills Studies, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264309791-en.

[7] OECD (2018), Getting Skills Right: Australia, Getting Skills Right, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264303539-en.

[17] OECD (2017), Financial Incentives for Steering Education and Training, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, Paris, https://www.oecd.org/publications/financial-incentives-for-steering-education-and-training-acquisition-9789264272415-en.htm.

[18] OECD (2017), Financial Incentives for Steering Education and Training, Getting Skills Right, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264272415-en.

[25] OECD (2017), Getting Skills Right: France, Getting Skills Right, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264284456-en.

[33] OECD (2017), Getting Skills Right: Good Practice in Adapting to Changing Skill Needs: A Perspective on France, Italy, Spain, South Africa and the United Kingdom, Getting Skills Right, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264277892-en.

[34] OECD (2017), Getting Skills Right: United Kingdom, Getting Skills Right, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264280489-en.

[35] OECD (n.d.), “Individual Learning Schemes: Panacea or Pandora’s Box box”, Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development, Paris.

[1] Productivity Commission (2017), “Upskilling and Retraining, Shifting the Dial: 5-year Productivity Review, Supporting Paper No. 8”, Productivity Commission, Canberra.

[23] Select Committee on Public Accounts (n.d.), “Tenth Report”, https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm200203/cmselect/cmpubacc/544/54403.htm.

[20] Senate Standing Committee on Education and Employment (2015), “Getting our money’s worth: the operation, regulation and funding of private vocational education and training (VET) providers in Australia”, Commonwealth of Australia.

[14] Smith, A., E. Oczkowski and M. Hill (2009), “Reasons for training: Why Australian employers train their workers”, National Centre for Vocational Education and Research, Adelaide, https://www.ncver.edu.au/__data/assets/file/0026/8369/reasons-for-training-2147.pdf.

[11] Smith, E. et al. (2017), “Continuity and change: employers’ training practices and partnerships with training providers”, National Centre for Vocational Education and Research, Adelaide, https://www.ncver.edu.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0028/267571/Continuity-and-change.pdf.

[12] TAFE Enterprise (2018), “Skills and Australian Business Report 2018”, https://www.tafensw.edu.au/documents/60140/86282/TAFE+Enterprise+Training+Report.pdf/bf500d82-3956-2ed5-5b39-b80d9c090dd5.

[15] White, I., N. De Silva and T. Rittie (2018), “Unaccredited training: why employers use it and does it meet their needs?”, National Centre for Vocational Education Research, Adelaide, https://www.ncver.edu.au/research-and-statistics/publications/all-publications/unaccredited-training-why-employers-use-it-and-does-it-meet-their-needs (accessed on 11 April 2019).

[2] Wood, S. (2014), When losing your job means losing yourself, Sydney Morning Herald, https://www.smh.com.au/opinion/when-losing-your-job-means-losing-your-self-20140719-3c7vb.html.

Notes

← 1. According to the ABS Survey of Education and Work for May 2018, adults age 25-54 with a Bachelor degree or above have lower unemployment rates (3%) than those with below Year 12 (9%), as well as a higher likelihood of participating in the labour force (90% versus 71%).

← 2. Temporary workers are the exception as employers are slightly more likely to offer temporary workers paid leave for training than permanent workers. A similar phenomenon is observed in France, where 70% of requests for paid education leave (Congé Individuel de Formation, CIF) were accepted for employees on fixed terms contracts, compared to only 49% for permanent employees (OECD, 2017[25]).

← 3. This study is independent from the biennial surveys that the Australian Industry Group has undertaken since 2012 on workforce development needs.

← 4. In 2015, the Australian Government introduced the Industry Skills Fund, which subsidised accredited and unaccredited training for SMEs. The government closed the programme in late 2016. Even though both accredited and unaccredited training were eligible under the ISF, the introduction of the programme lowered the cost of unaccredited training relative to accredited training because there were already subsidies available for accredited training (e.g. Commonwealth Grant Scheme, state-supported places in VET) but none for unaccredited training. One of the conditions of the ISF was that it could only apply to training that was not already eligible for funding under other government programs.

← 5. Much of the information in this section comes from the forthcoming OECD working paper, “Individual Learning Schemes: Panacea or Pandora’s Box.”

← 6. There were 4 989 registered training organisations in VET and 140 providers in higher education in Australia in 2014 – a very high number of providers per capita when compared internationally (Korbel and Misko, 2016[36]).

← 7. These are compulsory payments that can be levied on both employees and employers and are paid to government. They confer entitlement to receive a future social benefit, e.g. unemployment insurance benefits or old age pensions.