5. Working time and its regulation in OECD countries: How much do we work and how?

Working time is a crucial variable shaping the labour market and its adaptability to shocks. It can affect key labour market outcomes, such as workers’ well-being, productivity, wages and employment. Documenting how OECD countries regulate working time, and understanding how different regulatory settings shape working time outcomes is crucial for policy makers seeking to balance equity, efficiency and welfare considerations. This chapter offers a detailed review of regulations governing working hours, paid leave, and teleworking in OECD countries. It discusses the role of collective bargaining in negotiating working hours or working time arrangements, and how OECD countries have adapted their working time regulation during the COVID-19 crisis. The chapter also provides an update on working time patterns and trends in time use across OECD countries and socio-demographic groups. It measures how differences across workers in working time outcomes have changed over time and driven inequalities in work-life balance.

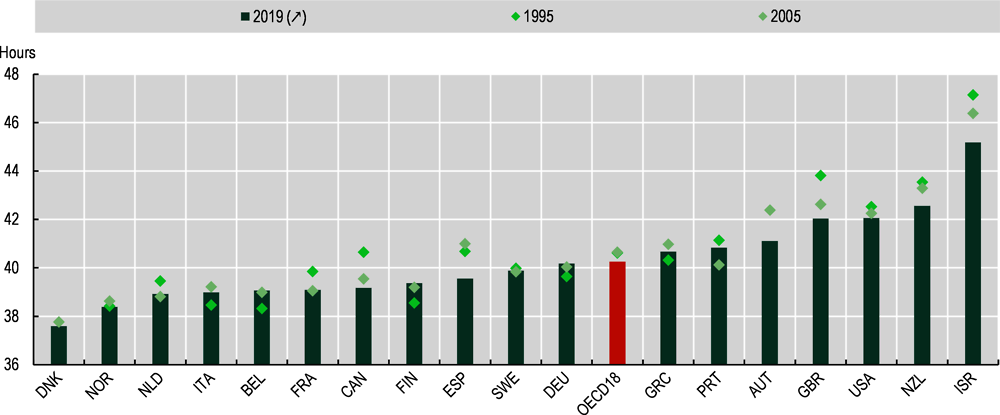

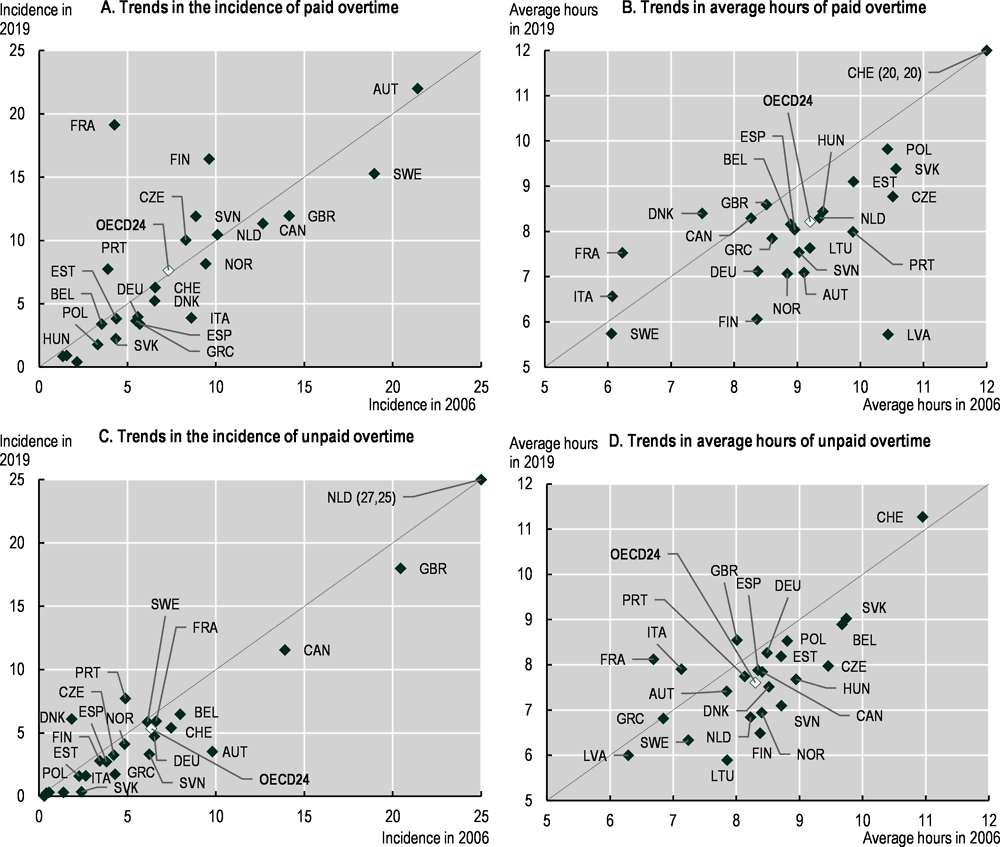

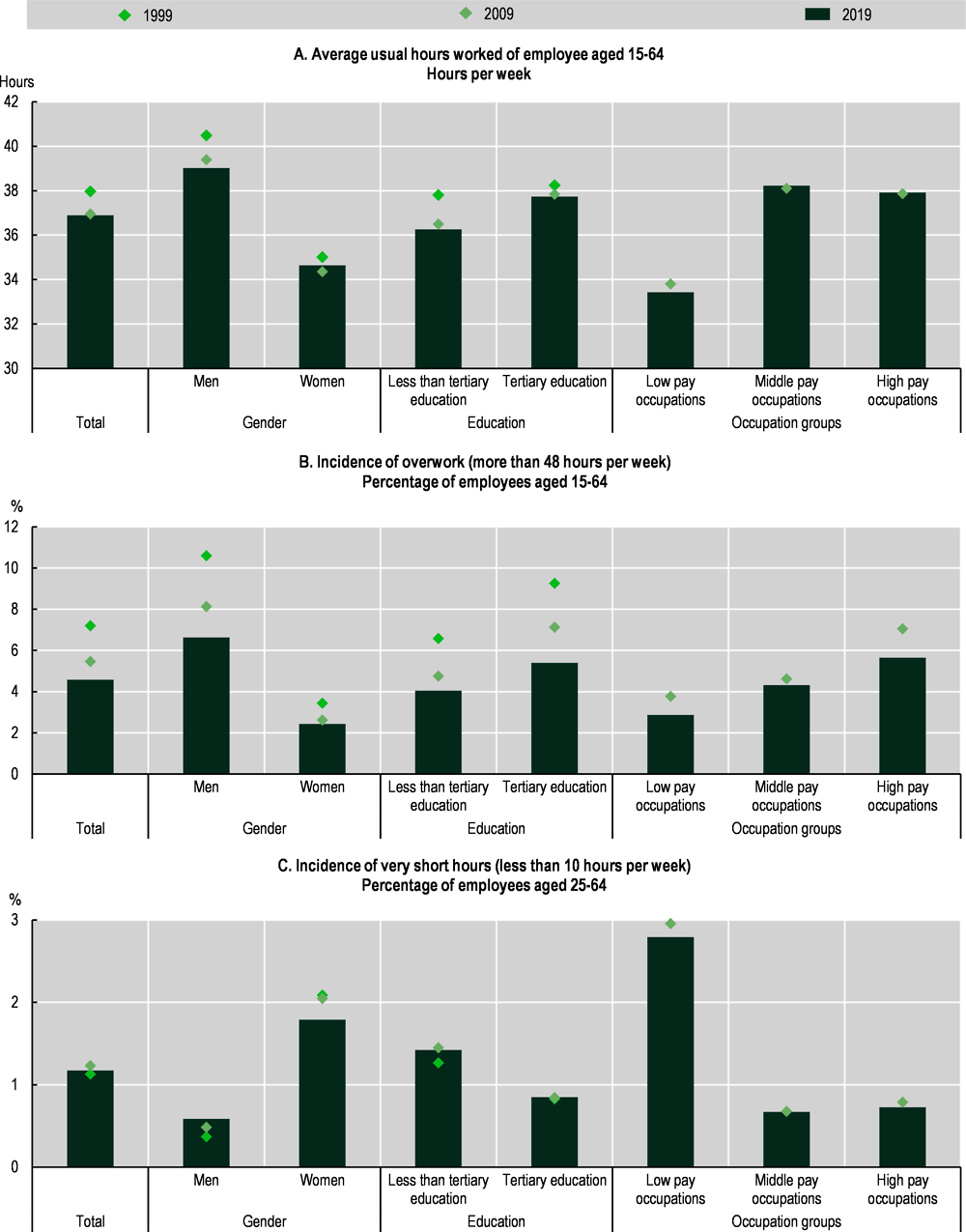

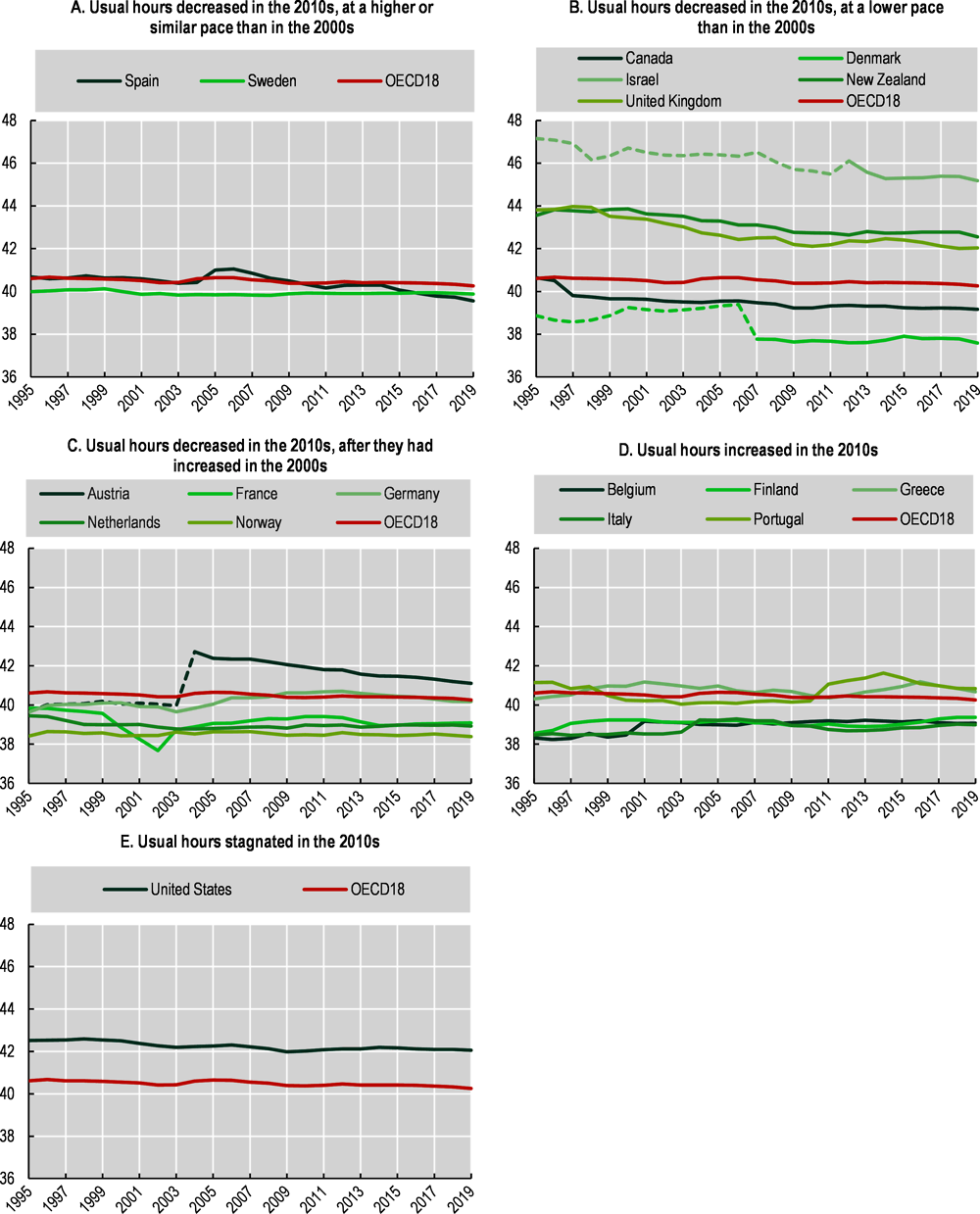

On average in OECD countries, usual weekly hours for full-time employees remained fairly constant between 1995 and 2019, despite small cross-country variations. The median full-time employee usually worked 40.5 hours per week in 2019, ranging from 37 hours in Denmark to 48 hours in Mexico and Colombia. Since the mid-2000s, the incidence of paid overtime has remained stable at just over 7.5% of full-time employees, while that of unpaid overtime decreased slightly, from 6.2% to 5.1%. For those working overtime, the average number of additional hours is considerable, amounting to 8.3 for paid overtime (7.7 for unpaid overtime), or one additional day per week in 2019.

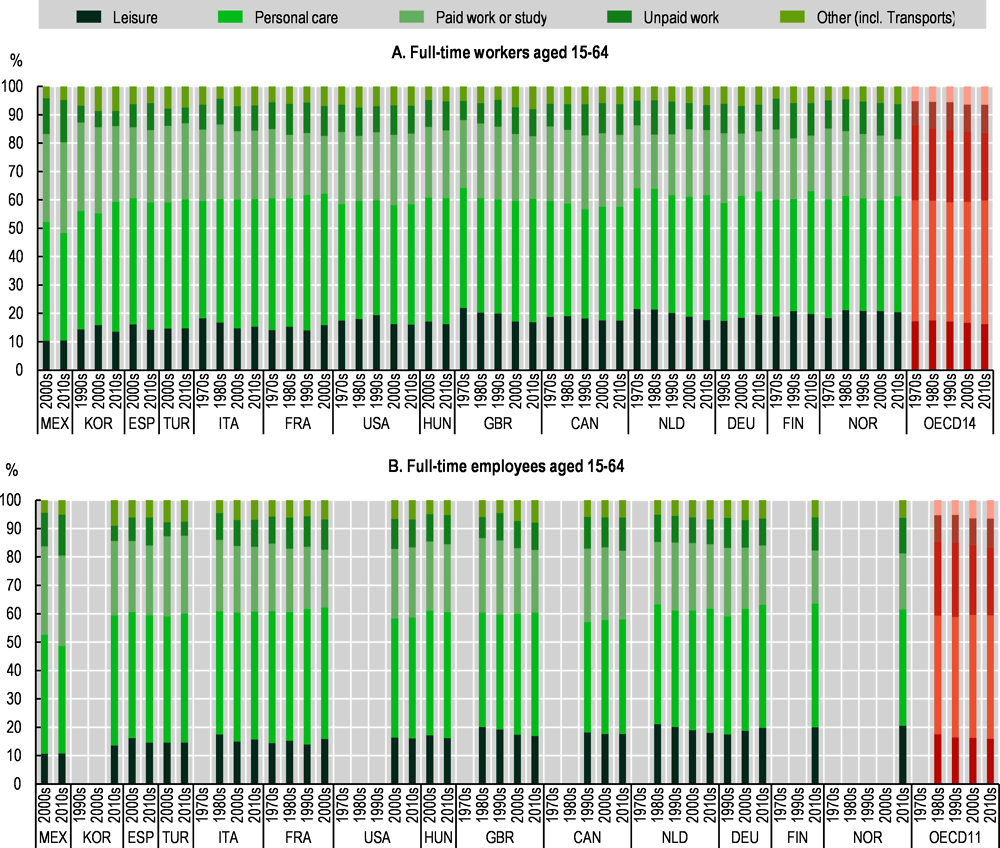

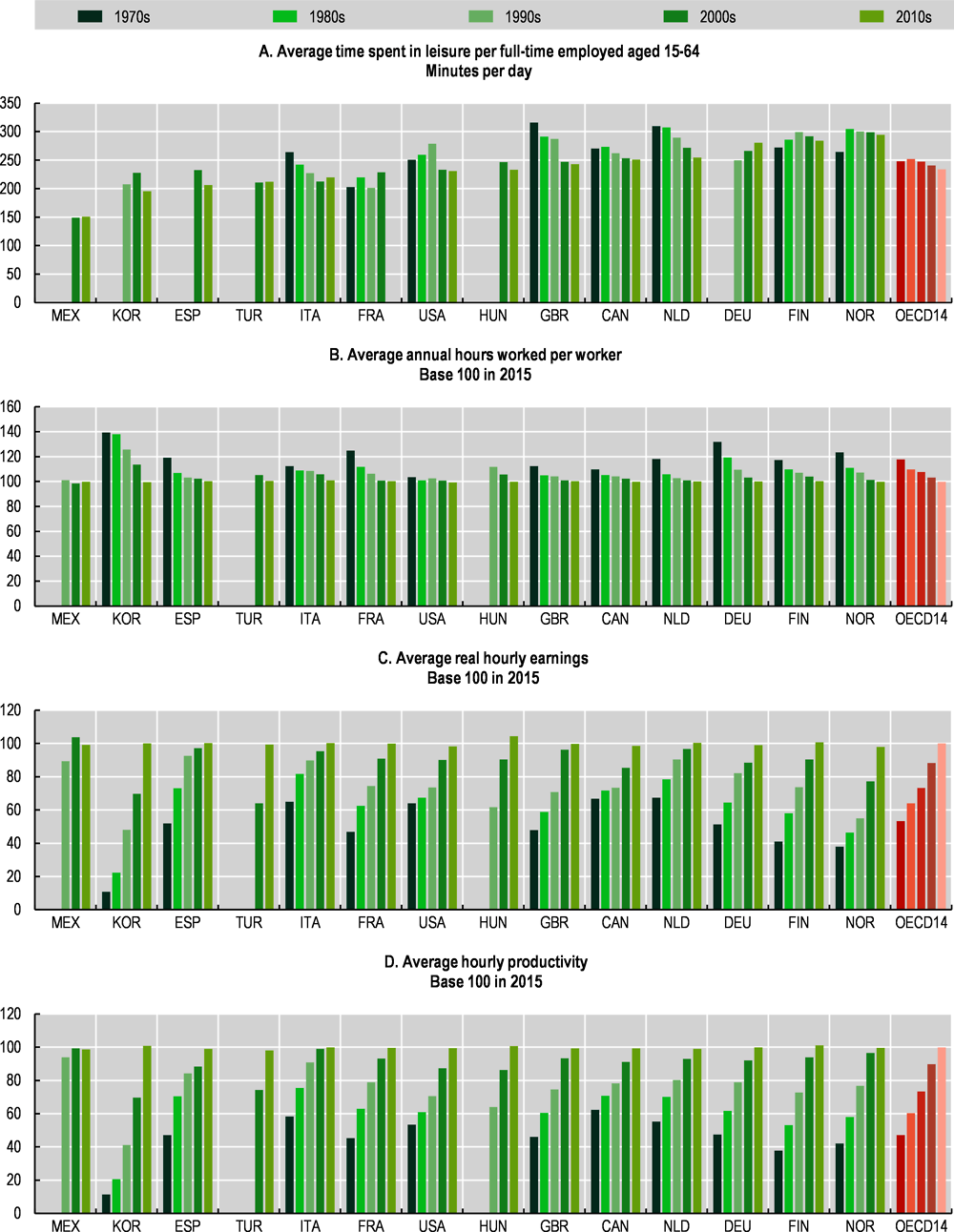

Leisure accounts for the third largest share of people’s time after personal care (which includes sleep) and paid work. Time allocated to leisure decreased by 1.5 hours per week for a full-time worker between the 1970s and the 2010s, on average in the 14 OECD countries for which data are available. This decrease started in the 1990s and accelerated over time. There are significant cross-country variations in work/leisure ratios: in the 2010s, Mexican workers spent more than three times as much time on paid work as on leisure, while Korean workers spent twice as much and German, Finnish and Norwegian workers spent about the same amount of time on both activities.

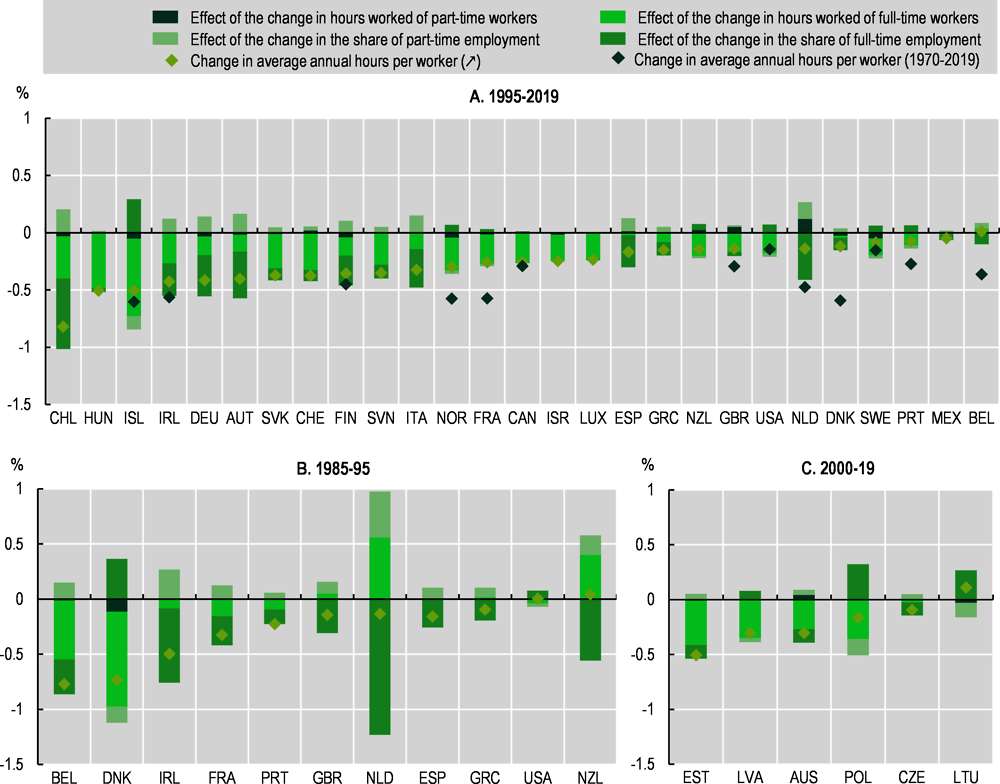

On average in the 11 OECD countries analysed, weekly hours actually worked per worker have decreased by 8 hours since 1970, but at a slowing pace (from 0.9% annually in the 1970s to 0.2% in the 2010s). Over the same period, hourly productivity has grown, also at a decreasing rate, from 3.7% annually in the 1970s to 0.7% in the 2010s. Comparing average trends in hours worked, leisure and productivity suggests that productivity growth has not led to extra leisure time for full-time employees.

Several insights emerge from this chapter’s review of the way working hours, paid leave and teleworking were regulated in 2020 in OECD countries, both through legislation and collective bargaining:

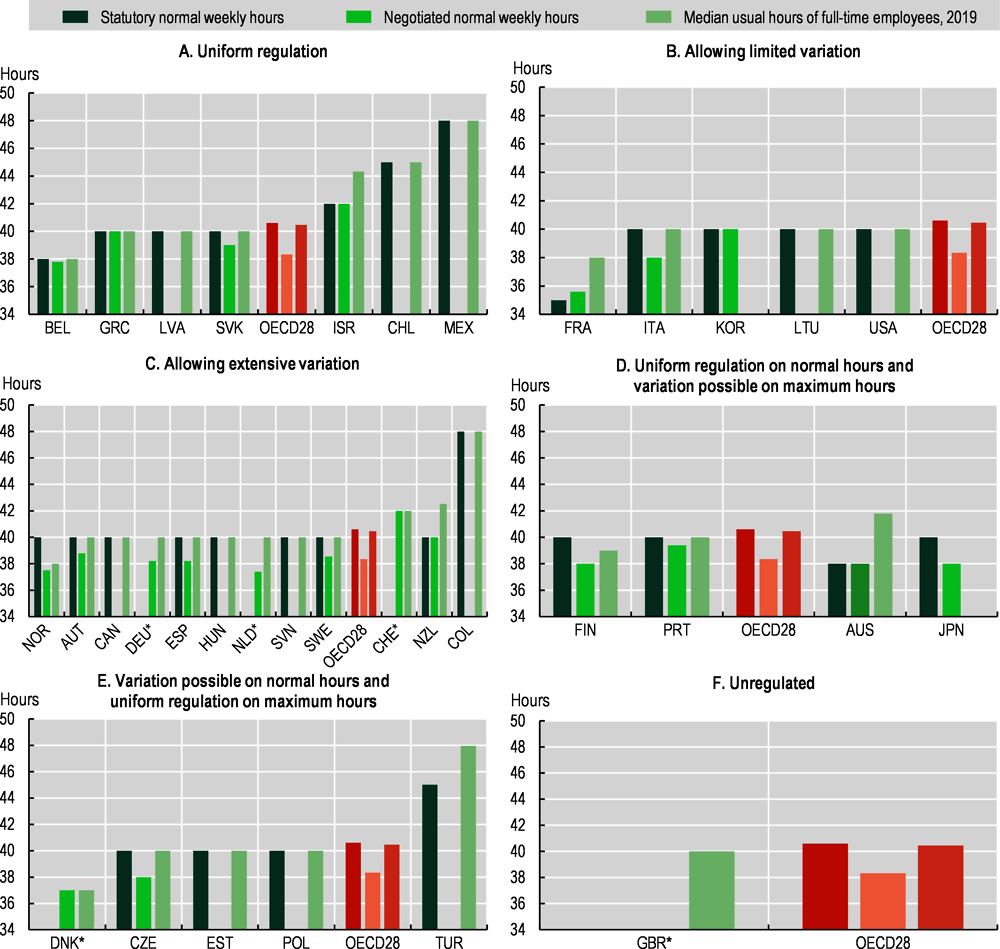

OECD countries can be clustered in six groups with different patterns of working hours governance. Those are characterised by the extent to which the limits on normal and maximum weekly hours can vary upwards: for example, in Chile, Israel and Mexico, rules are uniform – no variation is allowed, while some variation is possible either through derogation or averaging mechanisms in France or Lithuania; Austria, New Zealand or Sweden allow rules to vary to a larger degree. However, these patterns only affect usual weekly hours to a limited extent: in many countries where the possibility to exceed normal hours limits exists, it has no significant effect on median usual weekly hours – which are largely capped by statutory limits. Similarly, there is no strong relationship between patterns of governance and the frequency or duration of paid overtime.

In the majority of OECD countries, workers are entitled to a minimum amount of statutory paid annual leave. In a number of countries, collective agreements provide for substantially longer annual leave than this statutory minimum. In almost all countries, the amount of paid leave actually taken is higher than the statutory minimum.

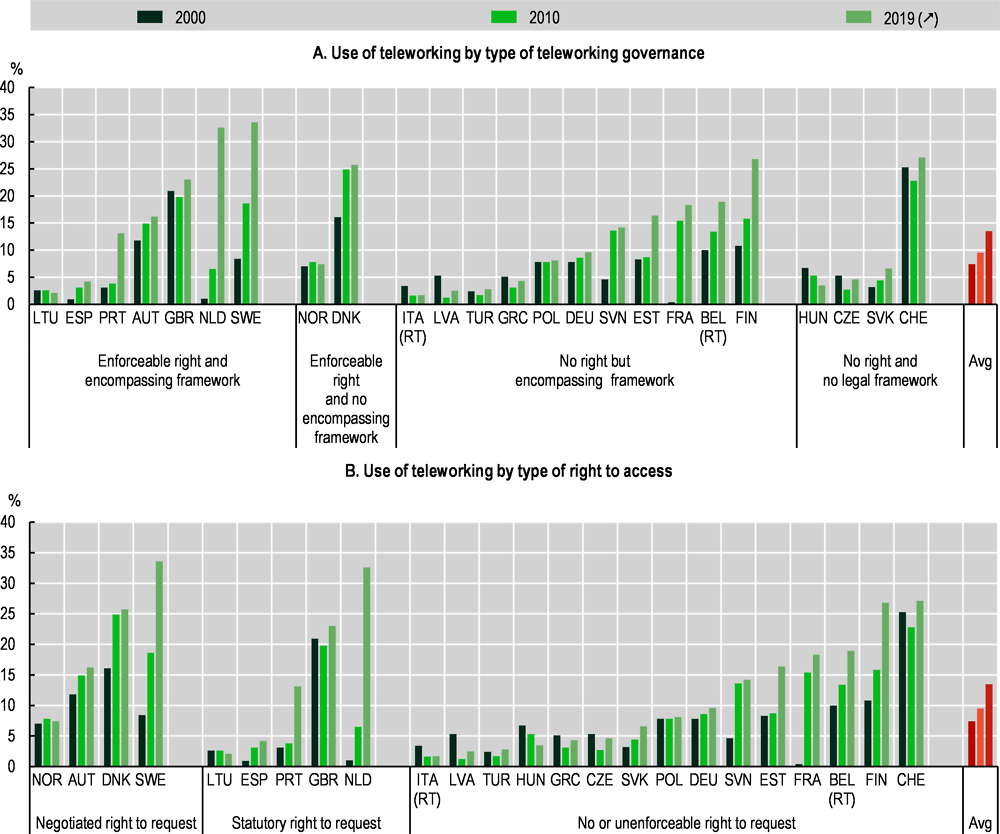

Access to teleworking is not guaranteed in all OECD countries. Legal rights to request teleworking, where they exist, can cover all employees (as in New Zealand or Spain) or some categories (as in Lithuania). In the Netherlands, Portugal and the United Kingdom employees have an enforceable right to request teleworking, while in some other countries employers can easily refuse to accommodate such requests. The way in which teleworkers’ working conditions are regulated (comprehensively or not, through dedicated legal frameworks or national/sectoral collective agreements, etc.) also vary. These regulatory differences affect access in practice: while the use of teleworking remained limited until the COVID-19 outbreak, it was higher on average in countries where there was an enforceable right to request teleworking, and highest in countries where this right was granted through collective bargaining.

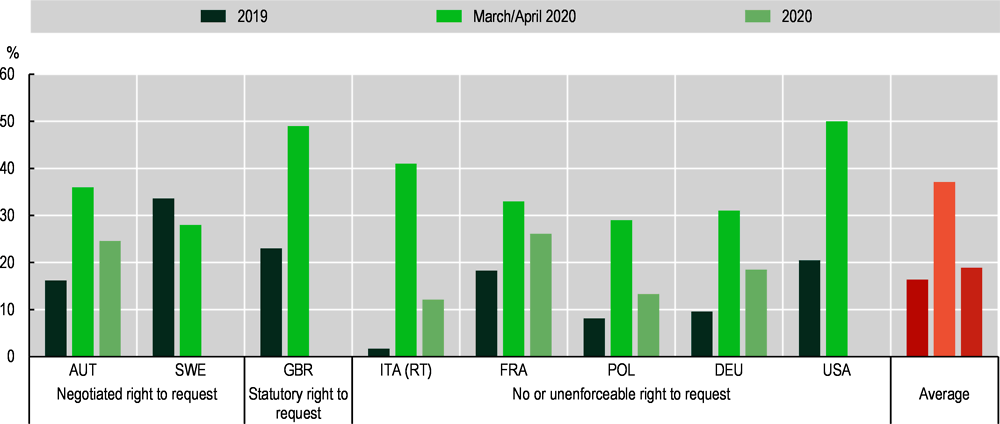

OECD countries have used working time as an adjustment mechanism during the COVID-19 crisis. They introduced policies enabling to work longer hours, to take more paid leave, to facilitate averaging arrangements and to telework more easily – which was reflected in the surge in the incidence of teleworking, from 16% in 2019 to 37% of employees in March/April 2020.

Hours worked and working time arrangements vary significantly between different groups of workers:

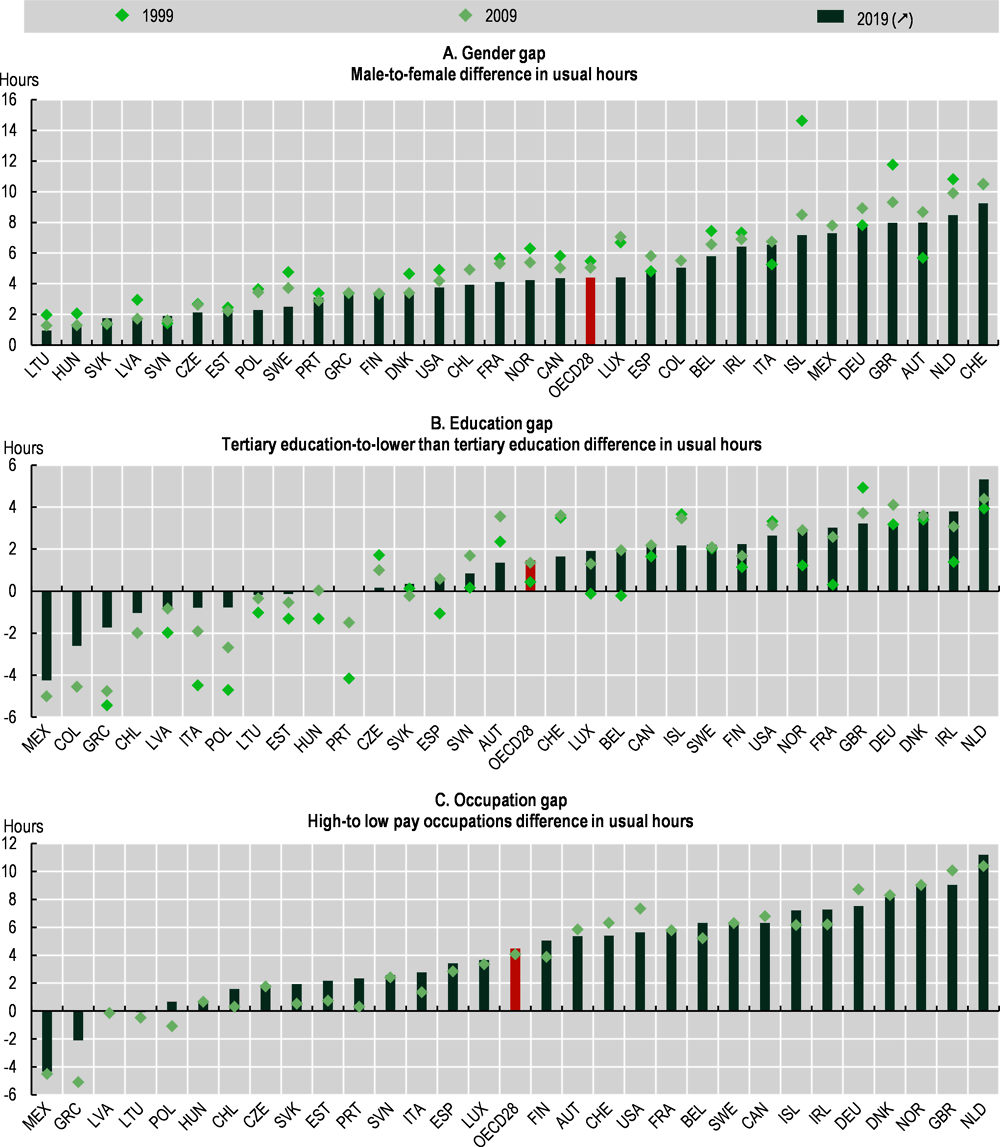

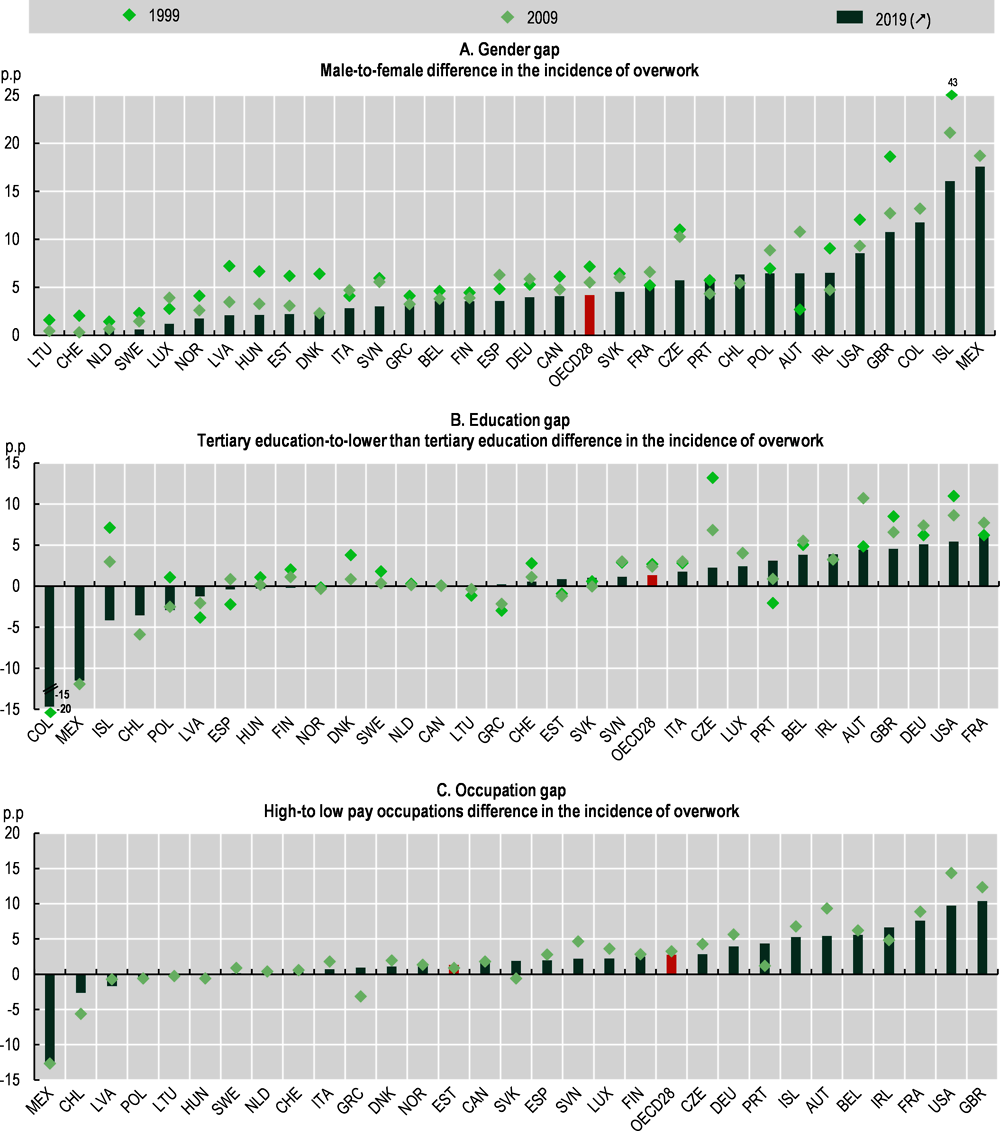

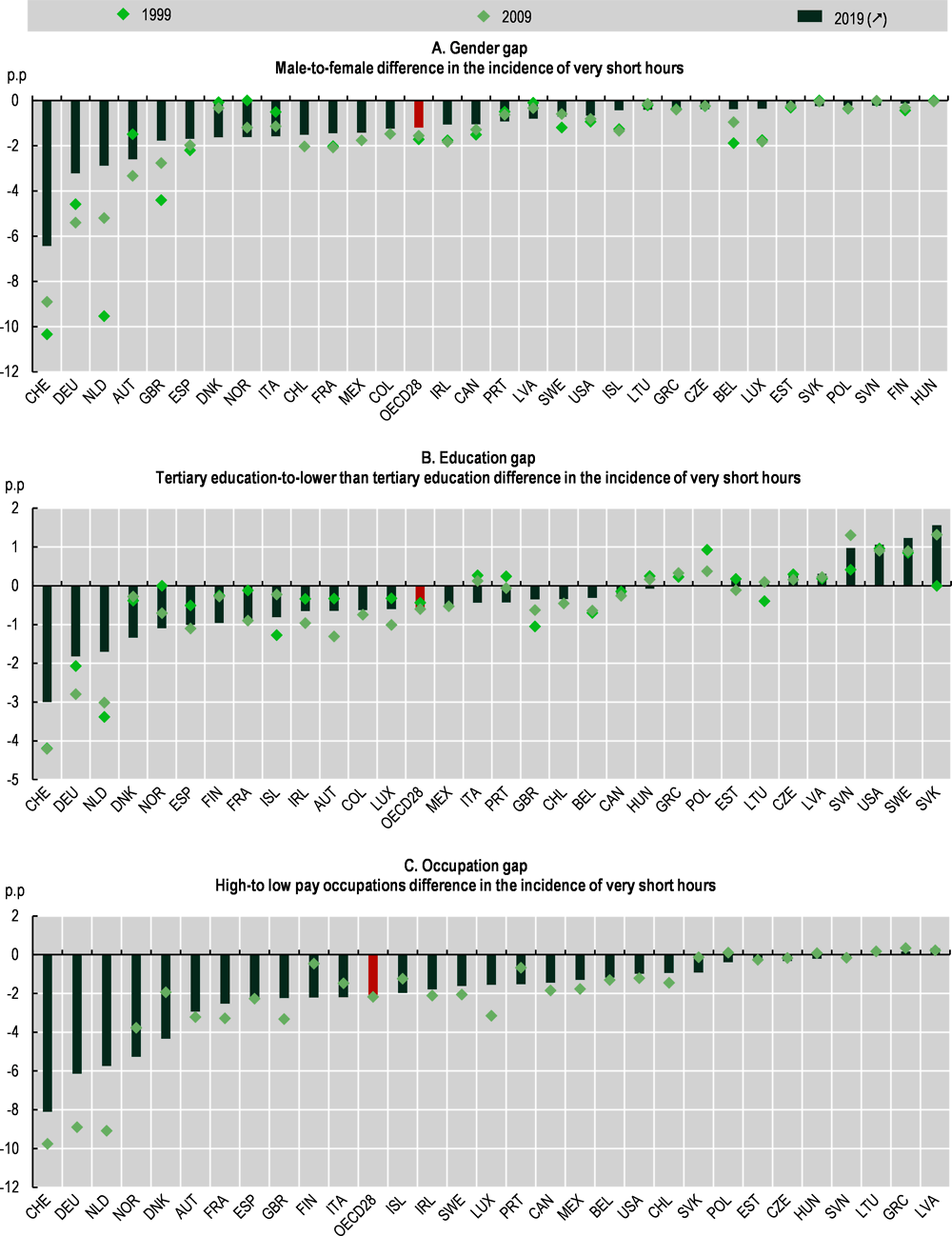

The prevalence of very short hours of work is higher and the prevalence of very long hours lower for women and low-educated workers, compared with men and highly educated workers respectively. However, while gender differences in working hours have been narrowing, educational gaps have been widening since 1999.

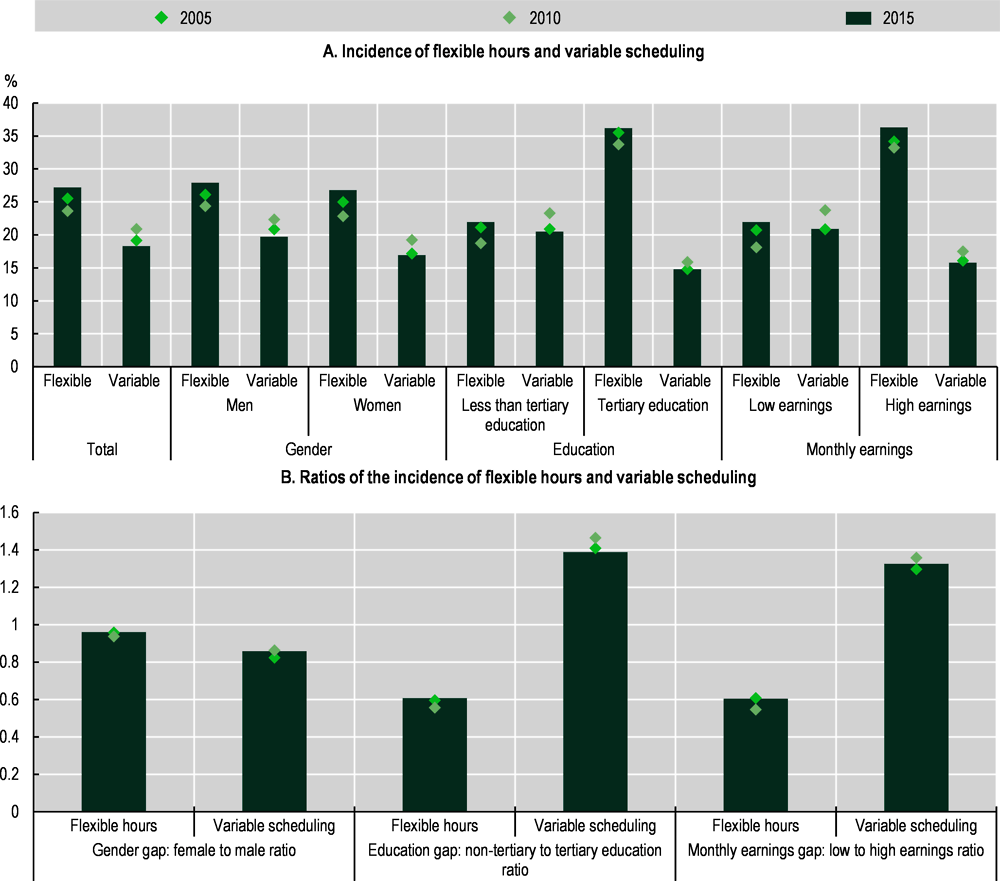

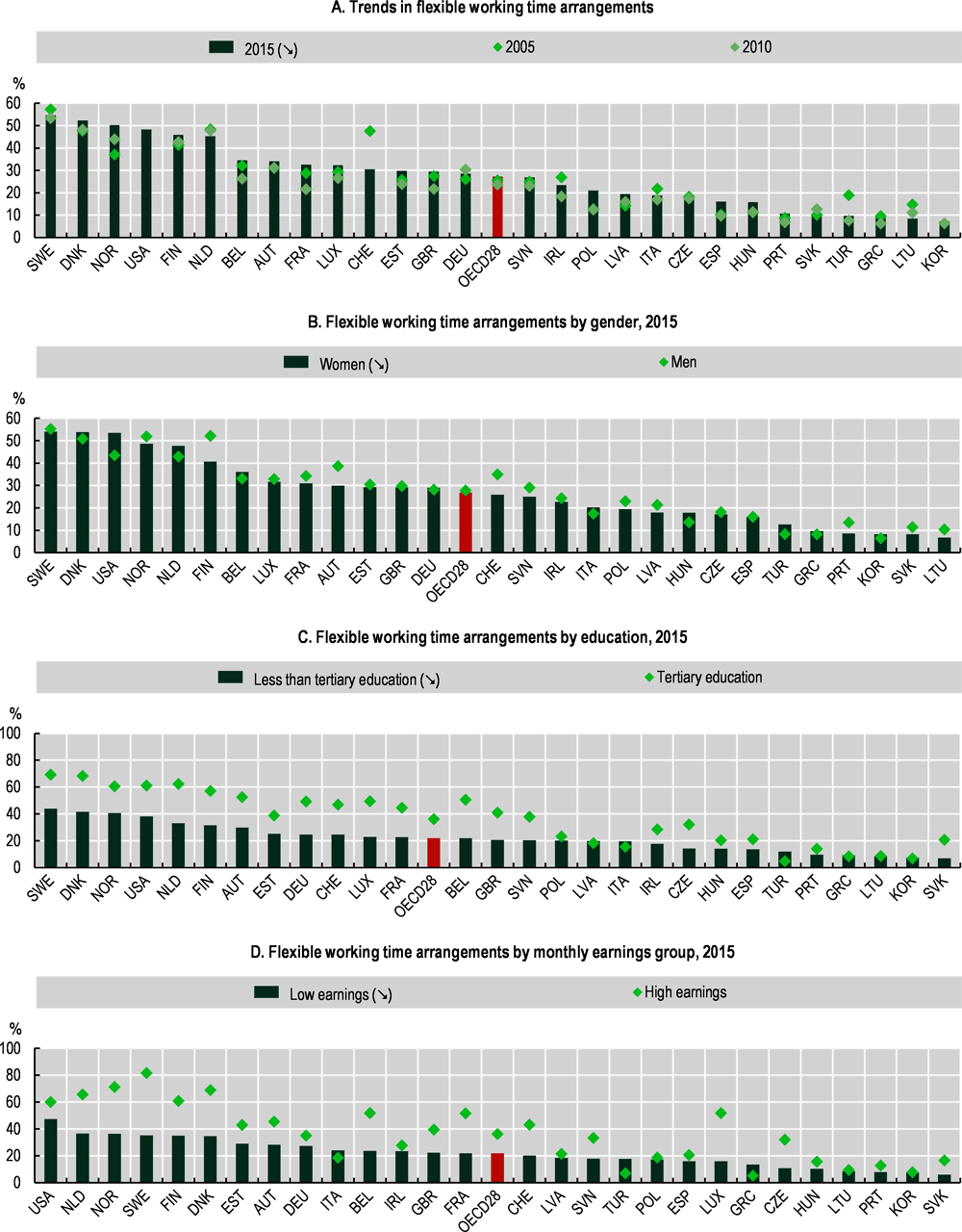

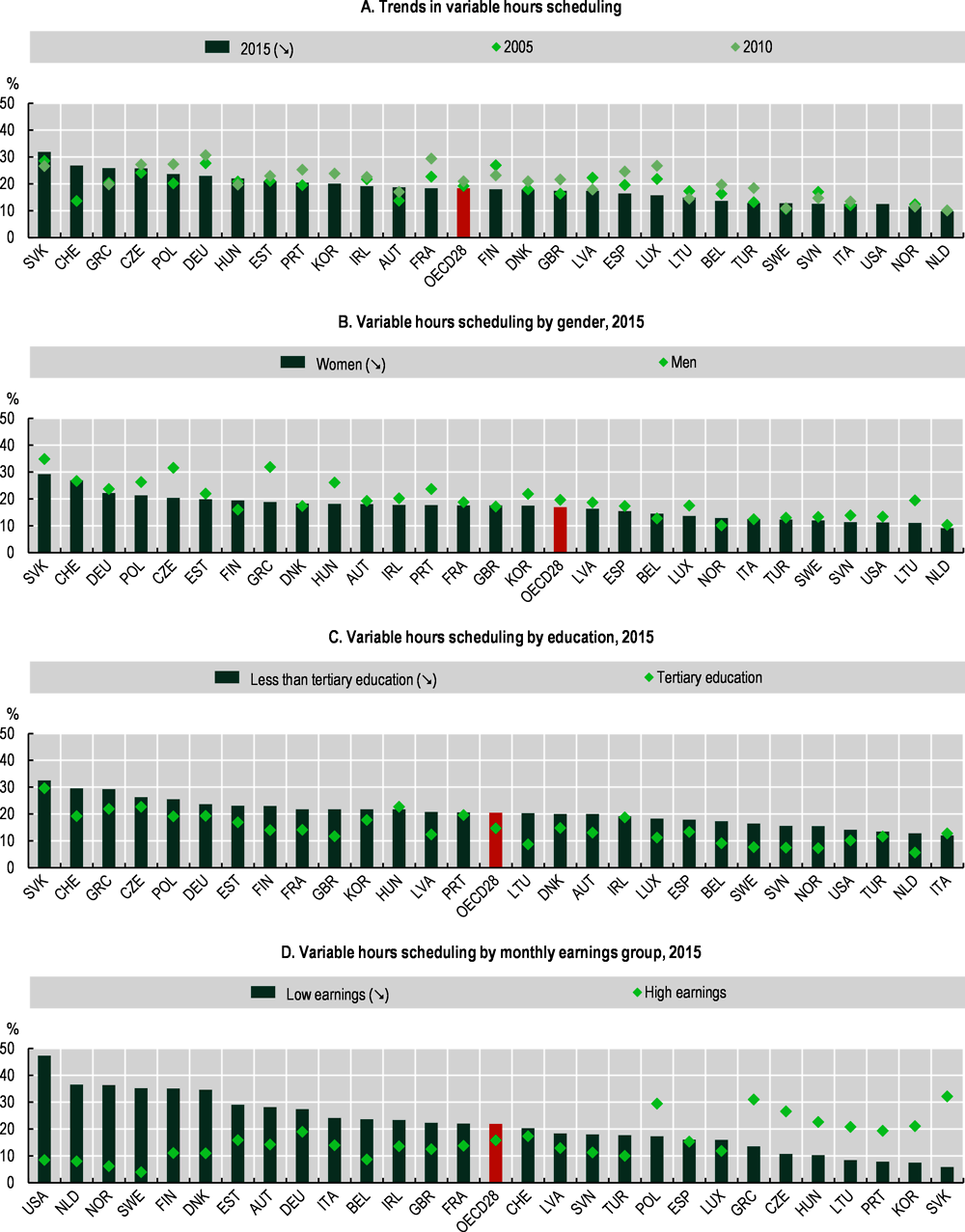

Flexible working hours arrangements, which allow workers to choose their schedule, are most often used by highly educated and highly paid employees. The education gap in access to flexible hours has been widening over the past decade, while the income gap has narrowed. By contrast, the incidence of variable scheduling – whereby workers have no control over their schedule – is highest for employees without tertiary education and low-paid employees.

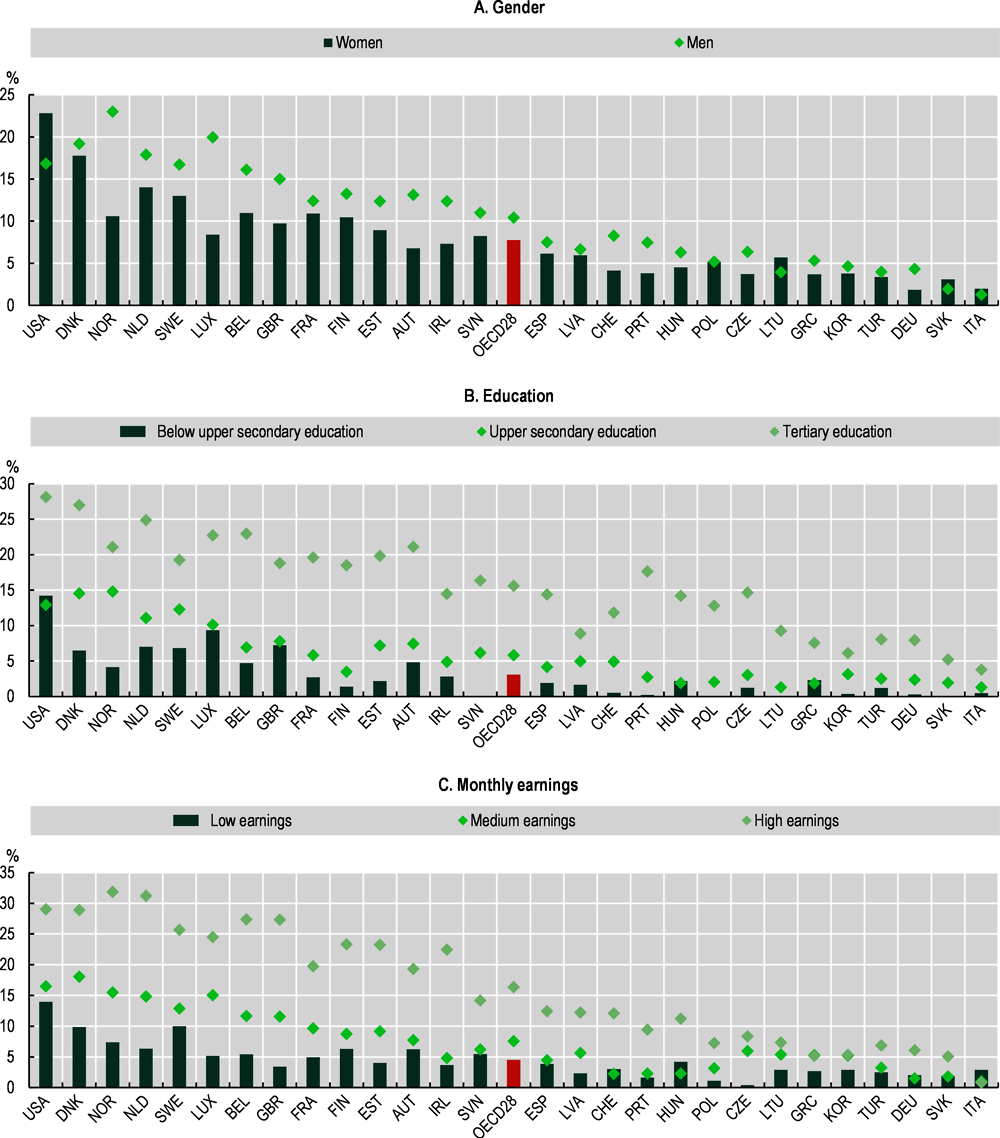

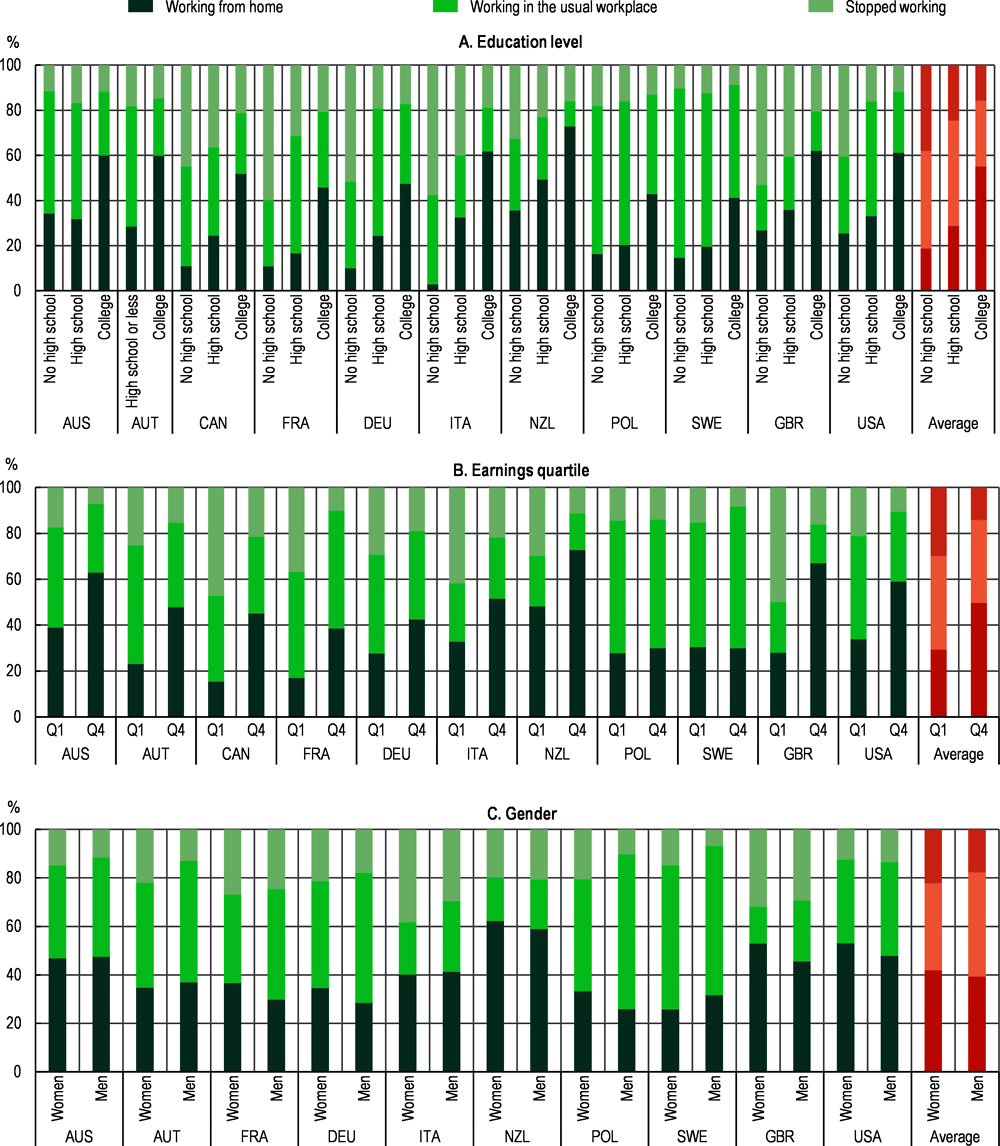

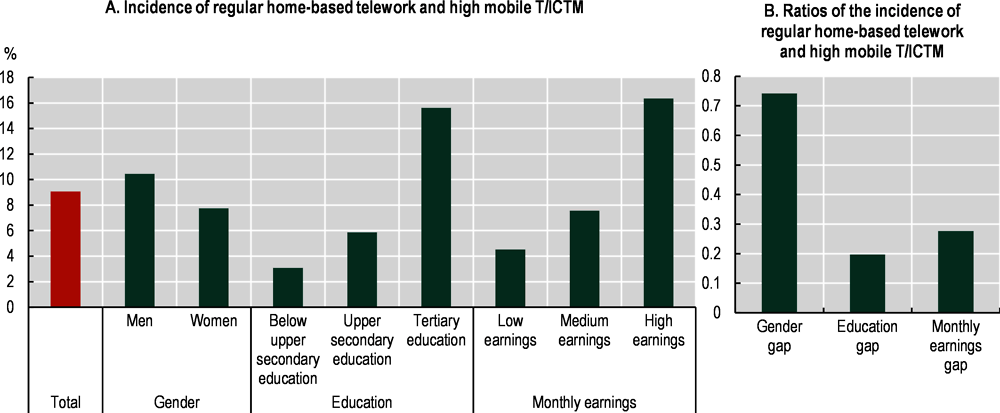

Prior to the COVID-19 crisis, teleworking arrangements were most often used by men, highly educated and highly paid employees in the majority of OECD countries. Disparities between educational and income groups widened during the first lockdowns, when 55% of highly educated workers were able to work from home on average, against 19% of low educated workers.

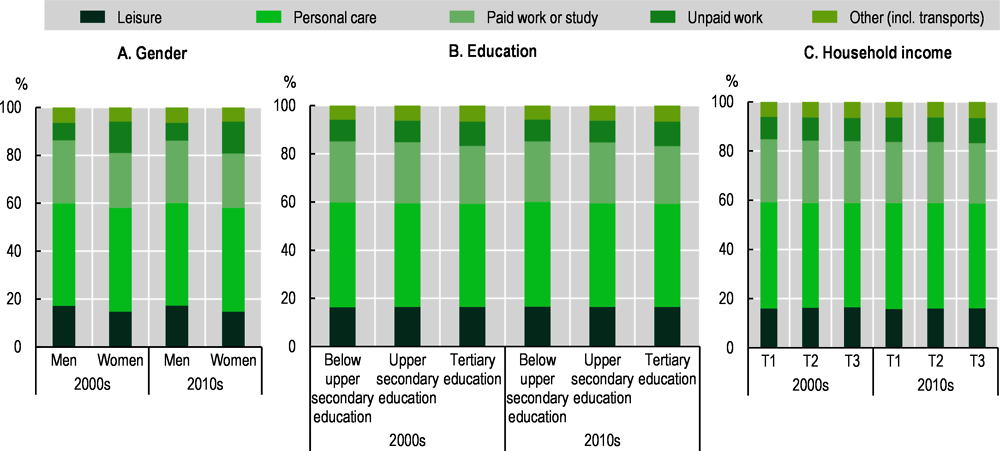

Available data for ten OECD countries reveal important work-leisure imbalances between men and women. Throughout the last 20 years, women have consistently enjoyed less leisure time per hour of work (paid and unpaid) than men. Ratios in the last decade are more comparable across educational groups, with workers of all education-levels spending on average 1.5 times as much time on work as on leisure. Higher paid workers spent on average less time on paid work and more time on leisure than lower-paid ones.

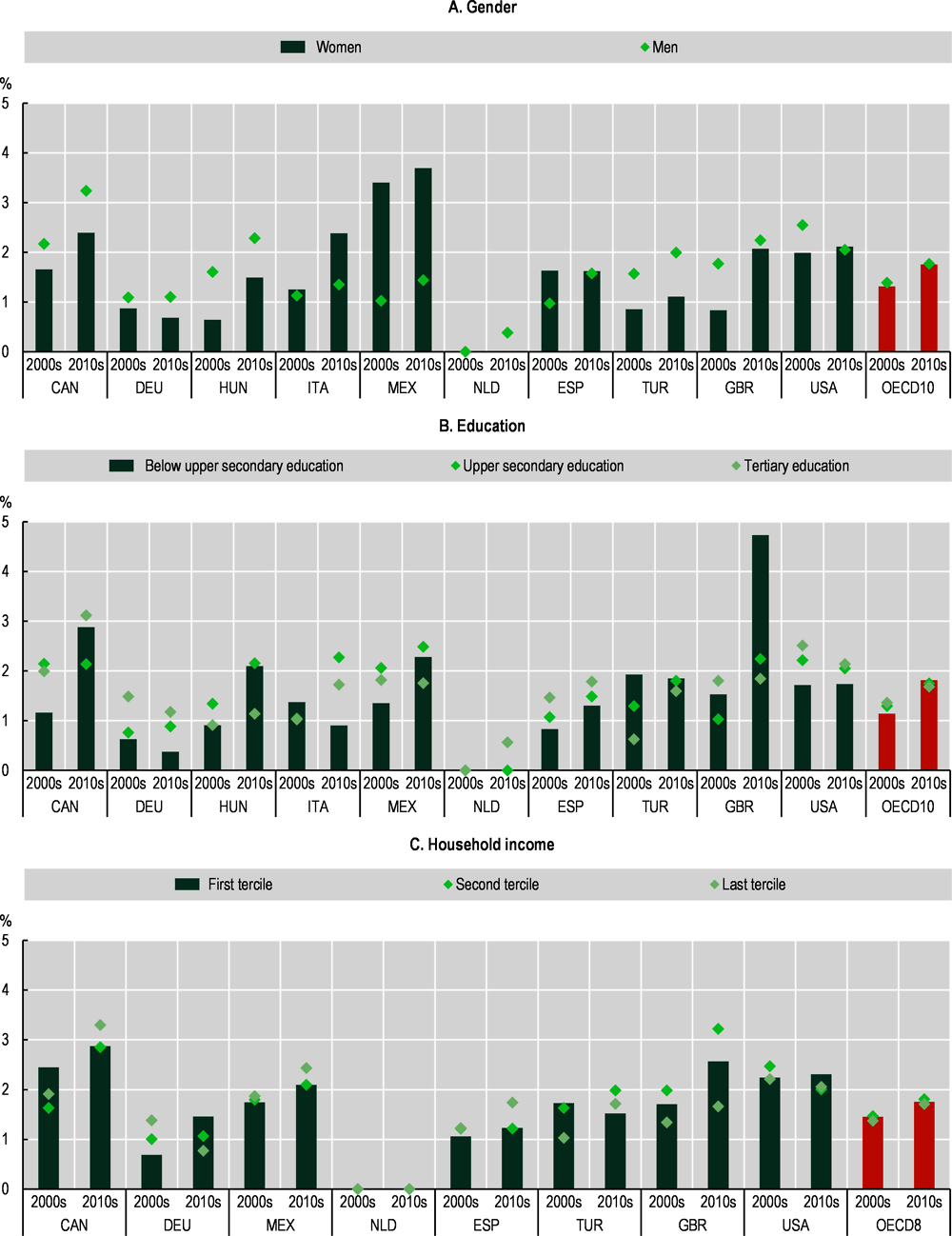

The share of workers defined as “time-poor” (i.e. those for whom the share of time devoted to leisure and regenerative activities is less than 60% of the median) increased over time for the ten OECD countries for which data are available, rising from 1.4% on average in the 2000s to 1.8% in the 2010s for men, and from 1.3% to 1.8% for women. In the last 20 years, the incidence of time poverty was lowest for the most highly paid third of workers.

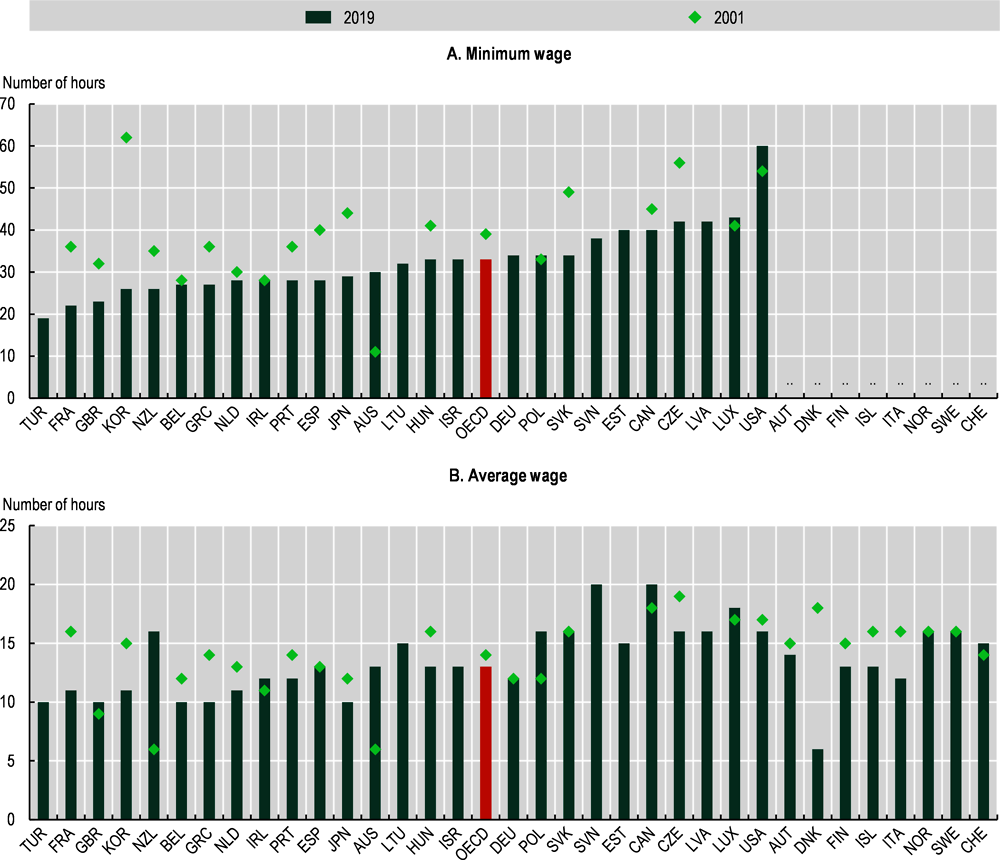

There are also important differences in the amount of work needed to achieve a given level of material well-being. In several OECD countries in 2019, a single childless minimum wage worker had to work more than 40 hours per week (i.e. more than the limit on normal weekly hours in most countries) to escape poverty.

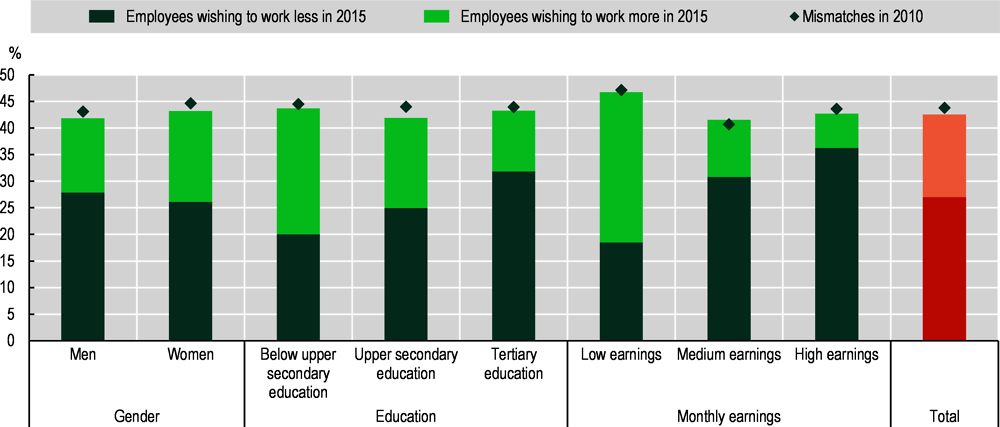

Overall, 43% of workers in OECD countries were dissatisfied with the amount of time that they spent working in 2015, with working too much being the dominant cause of dissatisfaction. The development of innovative collective bargaining practices and firm-level experimentation around working time reduction in recent years might be a sign that this dissatisfaction is being heeded, although more research is needed to confirm this conjecture.

Working time is a key component of people’s working lives. Regulating its duration and its organisation is necessary to correct possible market failures (due e.g. to asymmetry in market power between workers and employers) leading to inadequate protection of workers’ health and work-life balance, and to prevent negative externalities linked to excessive working hours or unpredictable schedules. Workers also need to be protected against the risks that unilateral cuts in working time and the corresponding reduction in income would pose to their material well-being. At the same time, worked hours being a production factor, the regulation of working time also impacts other key labour market outcomes, such as productivity and employment. In times of crisis, working time is a crucial policy instrument that can be adjusted to provide internal flexibility for firms. Therefore, understanding how different regulatory regimes relate to working time outcomes is key for policy makers seeking to balance equity, efficiency and welfare concerns.

This chapter focuses on three key dimensions of working time (see Box 5.1 for definitions): weekly working hours (both normal weekly hours excluding overtime and maximum weekly hours including overtime); paid leave and public holidays; and teleworking, as well as their corresponding outcomes (e.g. hours actually worked, leave effectively taken or actual incidence of teleworking). These have all been instrumental in providing internal flexibility to firms as a response to the COVID-19 crisis.

Section 5.1 documents the diversity of working time regulatory settings in OECD countries, looking both at the governance of working time rules (i.e. the way in which these rules are set, through law or through various types of collective bargaining, conditions for derogations, and the hierarchy between different types of statutory and negotiated rules) and the content of working time rules (such as the upper limits for weekly working hours, or the level of overtime premium). Taking into account the rules negotiated through collective bargaining is particularly important, since working time is typically one of the areas where social partners have margins of manoeuvre to factor in specific local needs, possibly leading to a large variation in practices (OECD, 2019[1]). Finally, the section reviews recent regulatory changes implemented as a response to the COVID-19 crisis.

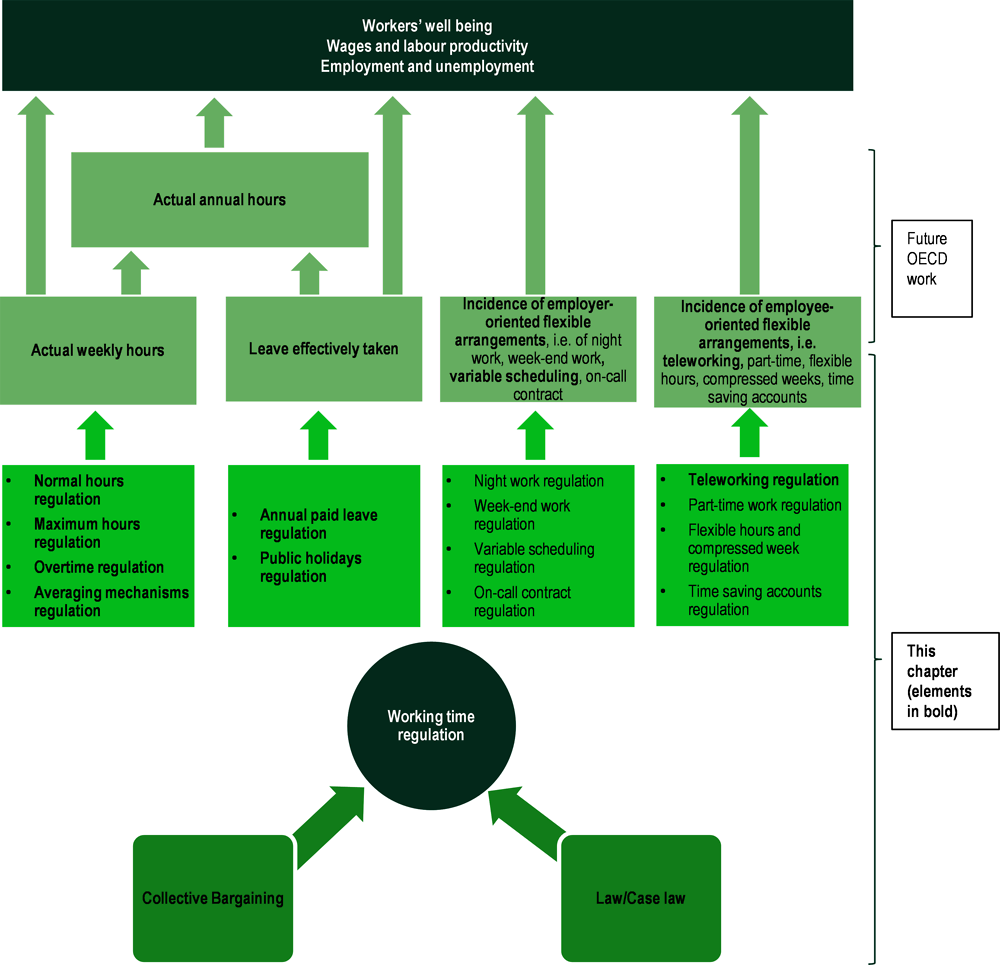

This comprehensive picture of working time regulatory settings is an essential first step to assess how working time regulation may relate to actual working time outcomes. These, in turn, may impact labour market outcomes, such as workers’ well-being, productivity and employment. This chapter concentrates on the first relationship, i.e. between rules and working time outcomes (see Figure 5.1).1 While it is often overlooked or taken for granted in the literature, this relationship might be expected to vary substantially with, for instance, the degree of heterogeneity allowed in working time regulations.

Taking a longer-term perspective, Section 5.2 investigates if younger generations work less than their parents, by looking at how the usual full-time work week2 has changed over time and across OECD countries. Fluctuations in the amount of time spent on work are mirrored by fluctuations in the amount of time spent on other activities outside of paid work. To get a better contextual grasp of development in working time, the section next reviews trends in time use, contrasting the shares of time spent on paid work, unpaid work, personal care, and leisure.

Finally, since national trends in working time may obscure changes in working time outcomes between socio-demographic groups, Section 5.3 exploits data from labour force and time-use surveys to assess disparities by gender, educational attainments and income groups, and the evolution of these disparities since the 1970s. The section presents trends in average hours worked, very long and very short hours, as well as various working time arrangements, disaggregated by groups. Patterns of mismatches between hours actually worked and the number of hours that workers would ideally like to spend working are also discussed.

Averaging arrangements: modalities used to average working hours, e.g. to exceed limits (both on normal and maximum hours) and/or overtime in any given week by smoothing the amount of hours on average, over a certain reference period.

Compressed working weeks: arrangements whereby a standard workweek is reduced to fewer than five days but workers work longer hours, thus keeping the number of hours per-week constant.

Derogations: derogations considered in this chapter are deviations in peius, i.e. deviations from the law and/or from higher-level rules that set a lower standard – i.e. provisions less favourable to workers. By default, it is almost always possible to deviate in melius from higher-level rules, i.e. to agree on a rule that is more favourable to workers. Deviations directly granted in the law also exist for particular groups, but they are not considered in this chapter as a source of variation from the norm: indeed such statutory derogations merely set different rules for different groups, but those rules are binding, and local actors cannot deviate from them.

Flexible working hours: arrangements whereby workers can choose their start and finish time.

Maximum working hours: maximum number of hours, including overtime, that workers are legally allowed to work.

Negotiated working hours: collectively agreed working hours set in collective agreements.

Normal working hours: number of working hours after which overtime conditions apply (or, put differently, working hours excluding overtime). In some countries, this number is set in the law (statutory normal working hours), in others it is set in collective agreements (negotiated normal working hours).

On-call contract: forms of employment where all or most working hours are set at the employer’s discretion, from no guarantee of any hour (“zero hours contracts”) to only a low guaranteed minimum. This should not be confused with “on-call duty”, which refers to periods of time during which the employee is expected to be work-ready, in the context of a traditional full-time or part-time contract.

Overtime hours: hours worked in excess of normal hours, that are subjected to specific conditions, such as workers’ possibility to refuse working overtime, or the application of overtime compensation, in the form of higher pay rates, or additional time-off.

Paid leave: annual period of time (usually expressed in number of days) during which workers can take time away from their work while continuing to receive pay and to be entitled to social protection, giving them the opportunity for extended rest and recreation. Paid leave is available in addition to public holidays, sick leave, weekly rest, maternity, long service leave and parental leave.

Public holidays: variety of cultural and religious non-working holidays that can be enshrined in statutory legislation at national or federal level, negotiated in collective agreements, or can exist de facto as unwritten cultural traditions.

Statutory working hours: the legal threshold after which overtime starts, as set in the law. They represent neither minimum (as workers may work part-time work) nor maximum hours (as workers can work overtime).

Teleworking: form of organising and/or performing work, using information technology, in the context of an employment contract/relationship, where work, which could also be performed at the employer’s premises, is carried out away from those premises on a regular or occasional basis.

Time-saving account: also known as time banking or working time account, such account allows the worker to build up “credits” by working overtime (paid at the normal hours rate), or to owe “debits” in hours worked (by taking advance leave), up to a maximum amount. Credits can be used as leave at a later date or traded against financial compensation.

Usual (weekly) hours: the number of hours individually worked by an employee during a normal week without any extra-ordinary events (such as leave, public holidays, strikes, or sickness), and without extraordinary overtime in addition to planned contractual overtime, as set in some employment contracts.

Variable scheduling work: contracts with regularly and unpredictably changing schedules (e.g. variable shift scheduling and on-call contracts).

Accounting for the regulatory setting that effectively apply to working time is key to derive expectations about how bindings rules are, and therefore how much variations can be expected in a given governance context.Drawing on the OECD Policy Questionnaire on Working Time Regulation (Box 5.2) this section documents in details the regulation of working hours, paid leave and public holidays, and teleworking at the beginning of 2020.3 It then presents synthetic information on the governance of working time and information on the content of the rules (statutory and negotiated)4 contrasting it to the latest available data on actual working time outcomes. Doing this allows gauging to what extent variation in regulations actually matters in producing variations in working time outcomes observed in practice.

Descriptions of working time regulatory settings in OECD countries presented in this chapter mainly rely on responses to the detailed policy questionnaires that were sent to Labour Ministries, employer organisations and trade unions in 2020. These responses, which inform Section 5.1 of the chapter usually correspond to the situation in 2020 prior to the COVID-19 crisis, except in the specific section on recent adjustments to regulation as a response to the COVID-19 crisis.

The questionnaires collected information on both statutory and negotiated rules in a number of areas of working time regulation. For information on regulation of working time that is set through collective bargaining, questions referred to the most frequent or the average clause among all workers covered by collective bargaining in the country.

The questionnaire was structured along six main blocks. The first block introduced the general organisation and governance of working time regulation (e.g. the hierarchy between statutory and negotiated norms and the degree of flexibility in deviating from standards set in the law or in collective agreements at higher levels). The second block was dedicated to the regulation of the amount of hours worked (daily and weekly working hours, as well as overtime). The third block examined the regulation of leave and public holidays. The fourth block looked at the regulation of the organisation of working time (e.g. unsocial hours and flexible working time arrangements). The fifth block collected information related to the existence of short-time work and more generally job retention schemes and how they have been adjusted as a response to the COVID-19 crisis (this information was exploited in Chapter 3 of this volume). Finally, the sixth block focused on recent reforms of working time regulation.

Questionnaires were pre-filled by the Secretariat and checked by contact points in Labour Ministries and social partners through the Trade Union Advisory Council and Business@OECD networks. Information for Canada presented in this chapter refers to the federal level.1 The information has been complemented and cross-checked with existing information from the OECD and other publicly available sources (government websites, other international organisation, and relevant research literature).

← 1. While detailed information was also received on regulation at provincial levels, it was not feasible to include all the different rules in this chapter, given the amount of variation between provincial regulations. Hence, most of the data on regulation related to Canada presented here refer to the Canadian Labour Code; the latter regulates the federally regulated private sector, or about 6% of the Canadian workforce. Labour standards for other sectors – such as manufacturing, construction, primary industries, and wholesale and retail trade – fall within the exclusive jurisdiction of the provinces and territories.

5.1.1. Weekly working hours

Regulatory settings of weekly working hours across OECD countries

In almost all OECD countries, limits on weekly working hours – both normal hours (excluding overtime) and maximum hours (including overtime) − and on overtime exist to prevent excessively long hours that may be detrimental to workers’ health and well-being (Pega et al., 2021[2]) and to productivity. Often, derogations to these rules (in the sense of rules being exceeded)5 and/or averaging mechanisms giving employers the possibility to increase working hours beyond these maxima under particular circumstances exist as well.

Three main types of rules can be found in OECD countries, often used in combination: i) rules setting limits on weekly working hours (both on normal and on maximum hours);6 ii) rules defining the conditions for the use and duration of overtime; and iii) rules defining the conditions of averaging − e.g. the possibility to exceed limits (both on normal and maximum hours) and/or on overtime in any given week by smoothing the amount of hours on average, over a certain reference period. These rules may be set by statutory law, by collective agreements, or be left to individual negotiations in some contexts.

Normal weekly hours

In the majority of OECD countries, the statutory limit for normal weekly hours is set at 40 hours a week, based on a five-day working week and eight-hour working days. Higher statutory maxima exist in Chile, Colombia, Israel, Mexico and Turkey. Belgium, France7 and Australia8 have a lower limit. In some other countries, there is no statutory limit on normal weekly hours: this is the case in Denmark, Germany, the Netherlands, Switzerland and the United Kingdom (see Annex Table 5.A.1). As mentioned above, these statutory limits can be exceeded through derogations allowing collective bargaining at the sectoral or at the firm level to overrule the limits set in the law:9 this is the case for instance in Austria, Belgium, New Zealand, Norway, Slovenia, Spain and Sweden.10 In some cases – for instance in Colombia – the normal weekly hours limit can be exceeded by mutual agreement between the employee and employer.

In many cases, employers can also exceed the default limit on normal weekly hours through averaging working hours over a reference period longer than a week, to determine the end of normal working hours, and the start of overtime (i.e. the point at which overtime pay rates start being paid, and in some cases, where a different tax treatment applies). This option exists in several countries, with different procedural requirements and modalities:11 in Belgium, Greece, Japan, Portugal and Sweden (where it needs to be agreed by collective agreement) and in Australia, Austria, Colombia, Finland,12 Norway, and Spain (where employees must consent to it). Finally in Canada, France, Hungary,13 Italy, Korea, Lithuania, Poland and Turkey, employers can unilaterally decide to use such averaging mechanisms for normal weekly hours. Significant differences in the parameters of averaging exist across OECD countries: in Australia, Colombia, France, Lithuania and Spain, for instance, the law stipulates a binding maximum period over which it is possible to average; in Belgium, Finland, Greece, Italy, Japan, Korea, Poland, Turkey and the United Kingdom, social partners can exceed the default maximum averaging period up to a higher binding ceiling. Independently of how they are set, maximum averaging periods for normal weekly hours vary quite substantially: where they are binding and set in the law, they range from 3 weeks in Colombia to 52 weeks in Spain, while they range from 6 to 12 weeks in Norway to 52 weeks in Belgium, where they are agreed upon collectively (see Annex Table 5.A.3).

Other factors beyond working time regulation are likely to affect working time outcomes. Nonetheless, understanding with precision the manner in and extent to which limits on normal weekly hours apply or are likely to be exceeded or bypassed in practice is crucial to go beyond “de jure” statutory limits on working hours, and to assess the expected degree of variation between statutory rules and outcomes. The governance of working hours in each country produces rules that are more or less binding; the more binding the rules, the more uniform the expected outcomes, and the larger the expected role of regulation in determining working time outcomes. In what follows, countries are clustered in six groups with different patterns of governance of normal weekly hours, according to how binding limits on normal hours are − accounting for possible derogations at lower levels of norms − and how easily averaging mechanisms for normal hours can be introduced (for a more detailed explanation of the clustering logic applied, see Annex Table 5.A.6):

In Chile, Estonia, Israel, Latvia, Mexico and the Slovak Republic, rules governing normal hours are uniform, with a binding upper limit that corresponds most frequently to the statutory default, and no possibility to derogate from it nor to use averaging mechanisms.

In Australia, Belgium, Finland, Greece, Portugal and Japan, rules governing normal hours are mostly uniform, with a limited possibility for variation. The upper limit on normal hours (either the statutory default or the one collectively negotiated at the national level) is binding, with no possibility to derogate from it. Yet there is a limited possibility to use averaging mechanisms through collective agreement (or with the employee’s consent in Australia14 and Finland).

Canada, the Czech Republic, France, Hungary, Italy, Korea,15 Lithuania, Poland, and Turkey allow for a more extensive variation in normal hours rules. The upper limit (most frequently the statutory default, except in Canada and Italy where it is negotiated) is binding, with no derogation allowed, but employers can unilaterally decide to use averaging mechanisms. Hence the regulation of normal hours is likely to be mixed, neither uniform nor fully heterogeneous. Slovenia and the United States16 are also in this group, since it is not possible to use averaging mechanisms, but the upper limit on normal hours can be exceeded through derogations at lower levels of bargaining (including individual agreements, e.g. in the United States).

Austria, Colombia, New Zealand, Norway, Spain and Sweden, allow for large variation in normal hours rules: the default upper limit (most frequently negotiated at the national or sectoral level) can be exceeded through derogations at lower levels17 of bargaining, and there is a (limited) possibility to use averaging with the employee’s consent or through collective agreement. The regulation of normal hours is thus likely to be mostly heterogeneous.

In Denmark, Germany, the Netherlands and Switzerland, rules governing normal hours are fully heterogeneous: there are no statutory nor centrally bargained upper limit on normal hours and limits are mostly negotiated at the firm-level (except in Denmark and the Netherlands, where the sectoral level dominates).

Finally, in the United Kingdom, normal hours are unregulated, and usually left to be determined in individual contracts with no higher-level limits. Neither are there any statutory nor centrally bargained limit on maximum weekly hours or overtime (see below).

Maximum weekly hours and overtime

Countries may also fix limits on maximum weekly hours (i.e. including overtime) (see Annex Table 5.A.2).18 This is the case in a large majority of OECD countries, and notably in most EU Member States and Norway which limit the maximum weekly hours to 48 hours on average over four months, in line with the EU Working Time Directive.19 In addition to rules on maximum hours, some countries have dedicated limits on the quantity of overtime work that can be performed in a given period of time. For instance, in Belgium, overtime is limited to a maximum of 143 hours within the period of reference used for averaging;20 in Chile, overtime is limited to 12 hours per week; in Switzerland, it is limited to 2 hours per day, and 170 hours per year.21 Limits go up to 45 hours per month and 360 hours per year of overtime in Japan (see Annex Table 5.A.2). In Australia,22 New Zealand and the United Kingdom,23 there are neither dedicated limits on overtime nor on maximum hours.

As with the limits on normal hours, limits on both overtime and on maximum hours can be binding (this is the case for instance in Finland, Mexico, the Netherlands, and Turkey), or might be exceeded24 through collective agreements (e.g. in Canada, Norway and Spain) or through individual agreements (e.g. in the Czech Republic, or Hungary) – see Annex Table 5.A.7. Even where derogations are not possible, limits on overtime and/or maximum hours may still be bypassed through averaging mechanisms (in some cases, averaging is possible in combination with derogations). While the averaging of normal hours is a way to delay the starting point of overtime in any given week, averaging maximum hours or the quantity of overtime is a means of bypassing the upper legal limit of overtime in any given week, provided this is compensated over the reference period. As for normal hours, procedural requirements and modalities vary across OECD countries. In Austria and Denmark, averaging of maximum weekly hours requires a collective agreement. In Estonia, Germany, Latvia, Norway and Portugal, the averaging of maximum weekly hours (and the maximum quantity of overtime in the Czech Republic and the Slovak Republic) can be introduced pending employees’ consent. In Hungary,25 the Netherlands, Slovenia or Sweden, maximum weekly hours (and the quantity of overtime in Switzerland) can be averaged unilaterally by employers. The maximum duration for averaging might be binding, it might be extendable by agreement under a ceiling (e.g. in Hungary or in the Netherlands), or in some cases (as in Austria and Denmark) there might be no binding limits on the duration of the averaging period for maximum weekly hours that can be negotiated (see Annex Table 5.A.3). In practice, maximum averaging periods for maximum hours or overtime vary across countries (and often, across sectors within countries), ranging e.g. from 6 to 12 weeks in Norway (most frequently negotiated provisions), to 52 weeks in Estonia.

Another source of variation between countries comes from overtime compensation. Most countries establish a minimum compensation for overtime hours. The latter can be either binding (meaning that lower level agreements can only set a higher compensation rate) – this is the case e.g. in Belgium,26 Israel, Italy, Portugal, Slovenia or the United States27 (see Annex Table 5.A.2), or there can be a possibility to agree on a lower compensation at lower levels (e.g. in Germany, Japan, or Latvia). Compensation can often take the form of a higher rate of pay, or of compensatory time-off (or it can be a combination of both). It ranges from a minimum rate of 110% in France and Italy, to 200% in Latvia and Mexico, and 150% in most countries. In Australia and Sweden, minimum compensation rates are determined in sectoral and firm-level agreements (and in industry-wide modern awards in Australia), and are therefore only relevant to covered workers. There are no provisions guaranteeing a minimum overtime rate higher than the wage rate for normal hours at all in New Zealand and the United Kingdom.

Following the same logic as exposed above for normal hours, the governance of overtime and maximum weekly hours across OECD countries can be described in terms of how binding the limits on overtime and maximum hours are and how easily averaging mechanisms for overtime or maximum hours can be introduced. Using these two criteria, OECD countries can again be clustered in six groups with different patterns of governance of overtime and maximum weekly hours (see details of the logic applied in Annex Table 5.A.7):

In Chile, Greece, Israel, Mexico, Poland and Turkey, rules governing maximum weekly hours/overtime are uniform. The upper limit (that corresponds most frequently to the statutory default) is binding, with no possibility to derogate from it, nor to bypass it using averaging mechanisms. In all these countries there is a binding minimum compensation for overtime hours.

In Belgium, the Czech Republic, Denmark, Latvia, and the Slovak Republic, rules governing maximum weekly hours/overtime are likely to be mostly uniform. The upper limit (most frequently the statutory default) is binding, but there is a limited possibility to use averaging mechanisms, only with the employee’s consent or through a collective agreement. In all these countries but Latvia and Denmark, there is a binding minimum compensation for overtime hours (in Latvia a lower minimum can be agreed upon, in Denmark there is no encompassing minimum compensation).

In Colombia, Finland, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, Korea, Lithuania, the Netherlands, Spain, Switzerland and the United States, the regulation governing maximum hours/overtime is likely to be mixed between uniform and heterogeneous.

In Finland, Germany,28 Korea,29 the Netherlands and Switzerland, the binding upper limit can be bypassed relatively easily, since employers can unilaterally decide to use averaging mechanisms. The minimum compensation for overtime is binding in the Netherlands and Korea, but it can be lowered in collective agreements in Finland, Germany and Switzerland.

In Colombia, France, Italy, Japan, Lithuania, Spain, and the United States, averaging is not possible, but the upper limit on maximum weekly hours (statutory or negotiated at a central level) can be exceeded through derogations at lower levels of bargaining (including through individual agreements in the United States). Except in Japan, the minimum compensation in these countries is binding.

In Austria, Canada, Estonia, Norway and Portugal, maximum hours/overtime rules are likely to be mostly heterogeneous: upper limits (statutory default or collectively negotiated at the national or sectoral level) can be exceeded through derogations at lower levels of bargaining, and there is a limited possibility to use averaging with the employee’s consent in most countries, or through collective agreement in Austria and Canada.30 In all these countries, there is a binding minimum compensation for overtime hours.

In Hungary, Slovenia and Sweden, maximum hours/overtime rules are likely to be fully heterogeneous: existing limits can be exceeded through derogations at lower levels of bargaining, and there is a unilateral possibility for employers to use averaging mechanisms. While the minimum compensation is binding in Hungary and Slovenia, there is no encompassing minimum compensation rate in Sweden.

Finally, in Australia, New Zealand and the United Kingdom, maximum hours are unregulated: overtime / maximum weekly hours are usually left to be determined in individual contracts with no higher levels limits;31 there are no encompassing minimum compensation for overtime hours.

Patterns of working hours governance across OECD countries

Table 5.1 combines the two previous country groupings, to capture the overall governance of weekly hours across OECD countries. Six patterns of governance of working hours emerge, which can be expected to produce more or less heterogeneous rules governing working hours:

Countries with uniform rules for both normal and maximum hours: in this group, upper limits on weekly hours (both normal and maximum hours) are set in the law or in cross-sectoral/sectoral agreements. Limits are binding (no derogations are allowed), and bypassing them with averaging mechanisms is only possible with employees’ consent or a collective agreement. The majority of workers in this group of countries is subject to similar rules, with relatively little variation.32 Belgium, Chile, Israel, Greece, Latvia, Mexico and the Slovak Republic fall into that category.

Countries allowing for some variation in both normal and maximum hours rules: upper limits on weekly hours (both normal and maximum hours) are set in the law or in cross-sectoral/sectoral agreements. However, limits can either be exceeded through derogations at lower levels of bargaining, or be bypassed through averaging mechanisms unilaterally introduced by employers. Heterogeneity can be expected to be higher in this group of countries compared with the previous one. France, Italy, Korea, Lithuania and the United States are in this group.

Countries allowing for a more extensive variation in both normal and maximum hours rules: upper limits on normal hours are either non-existent, can be exceeded through derogations (sometimes in combination with averaging), or can be bypassed through unilateral averaging; the upper limit on maximum hours can be exceeded through derogations (sometimes in combination with averaging) or bypassed through unilateral averaging. Within this group, Colombia, Germany, the Netherlands, Spain, and Switzerland allow for limited local variation of the maximum hours limit, but more extensive variation for normal hours; Canada, Hungary and Slovenia allow for a limited variation of the limit on normal hours, but more extensive variations for maximum hours; and Austria, New-Zealand, Norway and Sweden allow for extensive variations on both dimensions. Hence, heterogeneity could be highest in this group compared with the two previous ones.

Countries with uniform rules for normal hours, but allowing for variation of maximum hours rules: in this group, upper limits on normal hours are set in the law or in cross-sectoral/sectoral agreements; limits are binding (no derogations are allowed), and bypassing them with averaging mechanisms is only possible with employees’ consent or a collective agreement. By contrast, the upper limit on maximum hours can be bypassed through averaging mechanisms introduced unilaterally by employers, and / or exceeded through derogations. Hence the majority of workers is subject to similar rules governing normal hours, but potentially to different rules for maximum hours. Australia, Finland, Japan and Portugal belong to this category.

Countries with uniform rules for maximum hours, but allowing for variation of normal hours rules: in this group, upper limits on maximum hours are set in the law or in cross-sectoral/sectoral agreements; limits are binding (no derogations are allowed), and bypassing them with averaging mechanisms is only possible with employees’ consent or a collective agreement. By contrast, the upper limit on normal hours can be adapted locally through averaging mechanisms introduced unilaterally by employers, and/or through derogations. Hence the majority of workers is subject to similar rules governing maximum hours, but potentially to different rules governing normal hours. The Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Poland, and Turkey are in this group.

Countries where working hours are largely unregulated: there are no binding limits on either normal or maximum working hours; the United Kingdom is in this group.

This grouping is inevitably a simplification of the complexity of the governance of working hours. It necessarily focuses on some aspects (here, the rules governing the limits to normal and maximum hours), to the detriment of others.33 Moreover, the logic behind this clustering exercise focuses on one dimension (the heterogeneity vs. uniformity of rules and expected outcomes), while others could have been considered. More generally, in focusing on the governance of working hours, it does not account for the contents of rules themselves (although information on this is presented in Annex 5.A), which obviously matter for outcomes irrespective of their uniform or heterogeneous nature. Nonetheless, this clustering exercise adds nuance to the estimation of the relationship between working time regulation and working time outcomes. Indeed, it suggests that there are significant sources of heterogeneity in rules governing working hours in some countries, which should be accounted for when assessing the impact of working time regulation reforms on labour market outcomes (put differently, the “bite” of reforms is likely to vary between countries, depending on the degree of uniformity of their working time regulation).

Working hours regulation and hours worked

A good metric to capture how much a typical full-time employee works in any given week is median usual hours in the main job. Usual hours refer to the number of hours that full-time employees effectively work on average in a “normal” week (excluding the effect of particular events such as leave, public holidays, strikes, or sickness, that may affect working hours in any particular week – see Box 5.3 for more details).34 On average in the OECD,35 the median full-time employee usually worked 40.5 hours per week in 2019.36 Across countries, median usual hours ranged in 2019 from 37 hours per week in Denmark to 48 hours in Mexico and Colombia – see Annex Figure 5.A.1.

Outcomes observed reflect, at least to some extent, the content of rules on weekly working hours. The very high statutory limits on normal weekly hours in Chile, Colombia, Israel, Mexico and Turkey go hand in hand with a high median in usual weekly hours. Countries where normal weekly hours are regulated through locally negotiated limits (e.g. Denmark, Germany or the Netherlands) do not display a particularly high median in usual weekly hours compared to the OECD average – which is coherent with the fact that negotiated limits37 were systematically lower or equal to limits set by statutory law38 in OECD countries for which data exist (see Annex Figure 5.A.1).

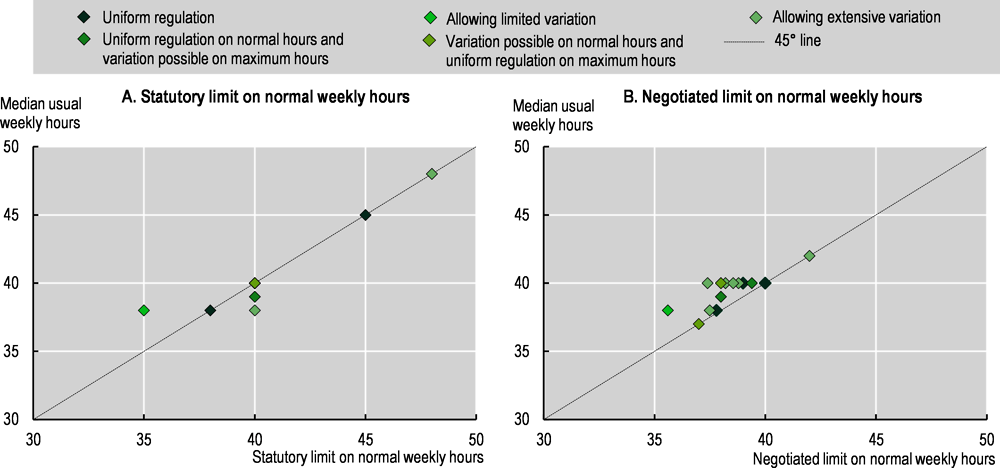

Importantly, in most countries for which data are available, median usual weekly hours remain at or under the applicable upper statutory limit in normal hours39 (Figure 5.2); in other words, statutory limits appear to act as a cap on hours in practice. By contrast, in most countries, usual weekly hours observed are higher than the negotiated limit on working hours indicated on the chart, pointing to the use of sectoral derogations – indeed data on negotiated limits presented in this chapter are often derived from available information on particular sectors.

The term working hours refers to several concepts. It can refer to a rule: the amount of work for which a worker is employed (contractual hours), or the amount of work for which she can legally be employed on the basis of the regulation she is subjected to (statutory working hours, negotiated working hours). It can also refer to the number of hours actually worked by this employee: in this case, a further distinction exist between actual working hours and usual working hours.

Actual hours, as defined in the 1962 ILO Resolution concerning statistics of hours of work, refer to all hours effectively spent working, including overtime hours and excluding absences (International Labour Organisation, 1962[3]). Although not explicitly stated in the resolution, actual hours of work routinely include both paid and unpaid hours at work. Usual hours of work are hours that an employee typically works over a definite amount of time (e.g. a day, a week, or a month), in the absence of any extra-ordinary events (such as leave, public holidays, strikes, or sickness), and without extra-ordinary overtime in addition to the regular overtime potentially included in her contract.

Data on hours actually worked (actual and usual hours) are collected in two main data sources: household-based surveys, such as labour force surveys (LFS) – which can be complemented with time-use surveys, the latter being more irregular and with smaller sample sizes – and establishment surveys, such as the European Structure of Earnings Survey (EU-SES).

There are some limitations to using household-based surveys, and labour force surveys in particular; first, while the European Union – Labour Force Survey (EU LFS) recently moved toward ongoing data collection, most other OECD countries do it on a discontinuous (albeit regular) basis such as one week per month or one week per quarter. This can affect the accuracy of data on both hours actually worked and hours not worked, since by nature, it does not account for unexpected irregularities in hours worked and hours not worked – for example, hours not worked on holidays, in bad weather, or because of school closings. Second, LFS data depend on respondent recall and proxy responses, so hours worked and not worked may not be correctly reported due to faulty memory or lack of information.1 Finally, LFS data only cover resident employees. In countries, such as Belgium, Luxembourg or Switzerland, with many cross-border workers, employment data from this source may not correspond to those employed in the country’s production of output, thus affecting working hours measures.

Data on working hours available in establishment surveys are generally considered more reliable than data based on individual recall, since they are extracted from payroll information. However, establishment survey data only cover paid hours, rather than all hours actually worked. In addition, both the practice and reporting of data collection of paid hours differ widely across OECD countries, making cross-country comparisons difficult. In some countries, such as Norway, sick leave or maternity leave are paid by the government or social partners, and are not captured in paid hours in establishment surveys; in other countries, such as the United States, paid sick leave is provided by employers, and is thus counted as hours paid in the establishment surveys. Finally, establishment surveys may not be representative of all industries (historically they mainly used to cover the manufacturing sector, although recently coverage has been expanded to include the service sector).

Since cross-country comparison is key in this chapter, data from labour force surveys is favoured to measure usual and actual hours of work.

← 1. However, concerns over respondent error in labour force surveys seem to be less of a problem than previously thought. The advent of time-use surveys has led to research that compares short-term recall of hours worked and longer term recall used in household surveys. For example, comparisons between the 1998 Canadian Labour Force Survey and Time Use Survey found that, overall, average numbers of hours worked were similar between the two surveys. A study based on American data (Fleck, 2009[4]) showed that time-use survey responses accurately reflected hours worked when the data were collected in or near the reference period, but that hours reported were 5% lower in data collected during later weeks. Usual concerns remain over proxy responses.

In order to explore how the governance of working hours regulation relate to median usual hours worked across OECD countries, Figure 5.2 compares statutory and negotiated provisions on normal weekly hours with data on median usual hours worked, by patterns of governance identified in Table 5.1.40 Figure 5.2 does not reveal any particular relationship between governance patterns and the content of statutory and negotiated provisions, as countries do not cluster by type of governance on the Y-axis. Looking at Figure 5.2, the extent to which the degree of uniformity versus heterogeneity of rules affects actual outcomes is not obvious: countries are close to the 45 degrees lines in both panels, irrespective of their governance patterns. In accordance with expectations, in countries with a uniform regulation of normal hours, usual hours observed for the median full-time employee tend to follow the statutory limit41 (see Annex Figure 5.A.1).The same holds true in three out of four countries allowing for a limited variation of normal hours regulation.42 There is slightly more divergence between the median usual week and regulatory limits in countries where more variation in normal weekly hours are possible. Interestingly, variations go in both directions: in Germany and the Netherlands, the median in usual weekly hours is higher than regulatory limits; but in Norway, it is lower than these limits. Importantly, however, there is no deviation between the statutory limit and median usual hours in close to 80% of countries which, in theory, allow for more variation. Furthermore, the data do not show more dispersion between workers in countries allowing for more variation in working hours rules.43 In fact, the highest standard deviations in usual weekly hours are observed in Mexico,44 where working hours rules are, in theory, uniform, and in Colombia, which allows for extensive variation. By contrast, the lowest standard deviation is observed in Switzerland, which also allows for extensive variation. Correlations between governance patterns and standard deviations in usual weekly hours are not statistically significant.45

All in all, Figure 5.2 suggests that where the possibility to deviate (in peius) from default limits on normal hours exist, it does not seem to be widely used, while in some cases where the regulation is, in theory, uniform, with no possibility for variation, these regulations might not be fully enforced. In other words, the relationship between working hours regulation and working time outcomes is not a straightforward one, even when considering different sources of rules and their articulation. This finding should inform future research on the relationship between working time outcomes and labour market outcomes (the second relationship in Figure 5.1); it also confirms that other factors beyond regulation (e.g. taxes and transfers, or cyclical effects) are likely to matter in determining working time outcomes.

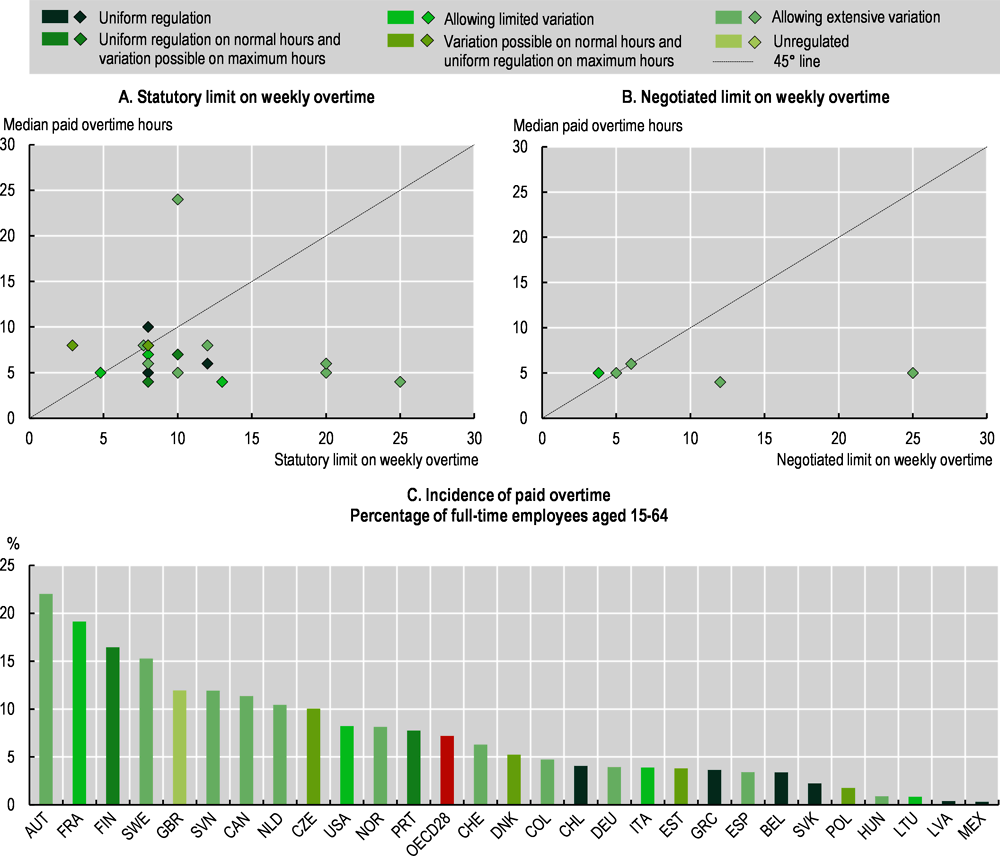

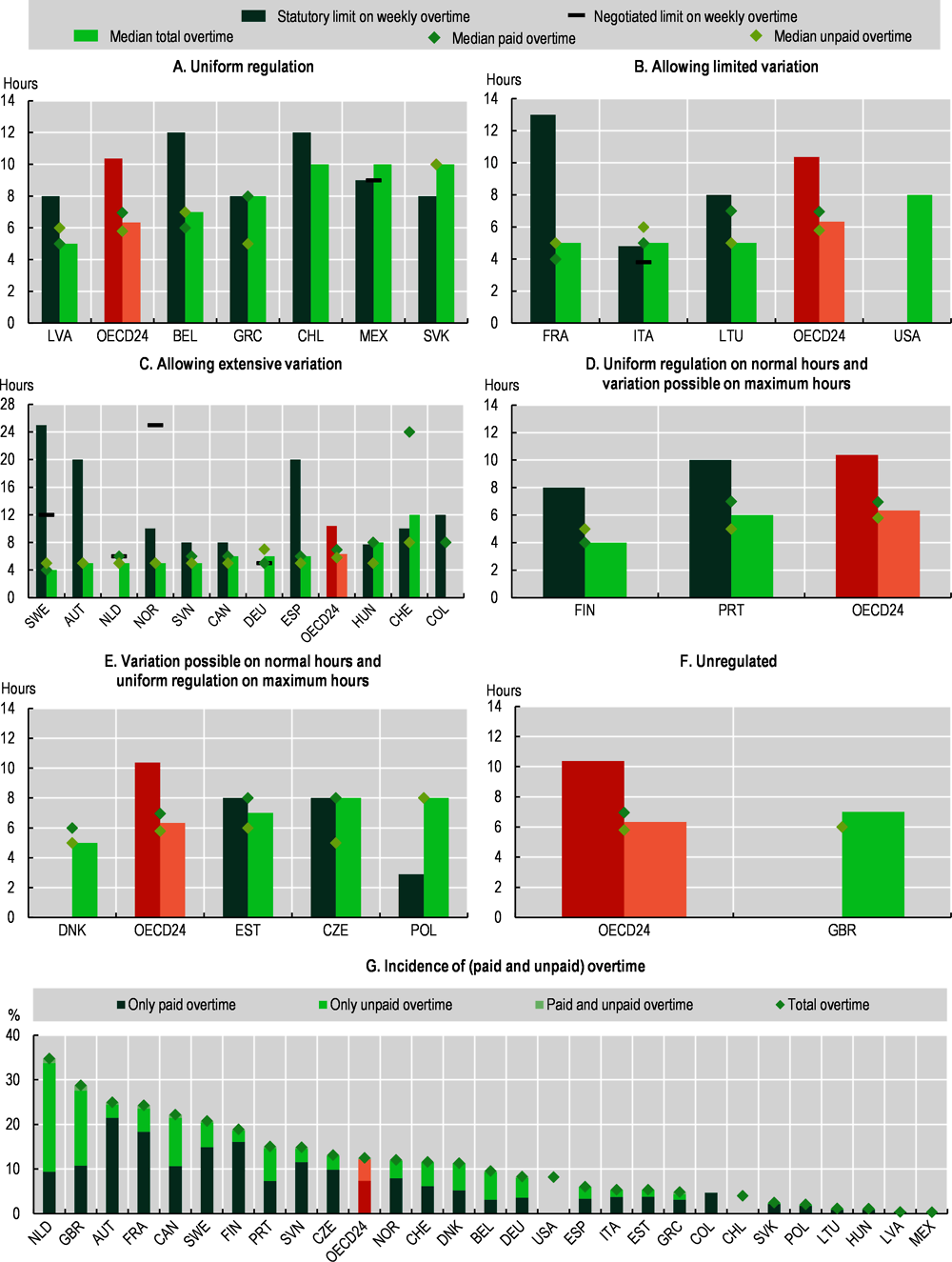

Turning to overtime, Figure 5.3 shows statutory and negotiated46 limits on weekly overtime, as well as the incidence and median hours of overtime per full-time employee in OECD countries in 2019, by patterns of working hours governance. Measurements of overtime are clouded by several issues that should be taken into account from the outset and kept in mind when analysing the data in Figure 5.3 (and Annex Figure 5.A.2). Overtime hours are often not accurately recorded (Green, 2017[5]), which means that the data limitations inherent in any survey (wrong recollection, approximation, etc.) are probably heightened. Measurement of unpaid overtime is likely to be particularly patchy. For that reason, Figure 5.3 focuses on paid overtime – which is also more likely to be directly related to working time regulation than unpaid overtime (however see Figure 5.9, Annex Figure 5.A.2 and the brief discussion below for data on unpaid overtime).

On average in OECD countries for which data are available, 7.7% of full-time employees worked paid overtime in 2019. The incidence of paid overtime ranged from 0.4% of full-time employees in Latvia to 22% in Austria. On average across OECD countries, among employees that reported paid overtime, the median amount of reported hours was 8.3 hours, i.e. about one additional day of work per week. However, this figure varied largely across countries, ranging from 5.7 hours in Latvia, to 20 hours in Switzerland. In parallel, 5.1% of full-time employees on average worked unpaid overtime in 2019, ranging from 0.02% in Latvia, to 25.4% in the Netherlands. The median amount of unpaid overtime was 7.7 hours, among those who reported it, on average across countries, ranging from 5.9 hours in Lithuania, to 11.3 hours of weekly unpaid overtime on average in Switzerland (see Figure 5.9 for detailed data on paid and unpaid overtime).

Simply eyeballing Figure 5.3 and Annex Figure 5.A.2, there does not seem to be a clear-cut link between the incidence and median hours of paid overtime: some countries have a high incidence, but a low amount of weekly paid overtime (e.g. Austria, Finland), some have a low incidence, but a high median (Estonia, Greece, the Slovak Republic, or the United Kingdom), while some have both a high incidence and a high median (e.g. the Czech Republic) (here again several countries may hide behind the same point in the scatterplot – see Annex Figure 5.A.2 for the detailed data).

Where data on both statutory rules and negotiated provisions could be collected, there is no clear pattern in the relationship between statutory and negotiated provisions: in Italy and Sweden, negotiated provisions tend to fix a lower limit on weekly overtime than that authorised in the law (although in both cases social partners could negotiate a higher limit), while the reverse is true in Norway (see Annex Figure 5.A.2).

Here again, Figure 5.3 does not display a clear-cut relationship between the degree of variation allowed in the rules and the actual degree of variation in outcomes observed. The median amount of paid overtime for full-time employees tend to stay within the limits fixed in the law or in higher level collective agreements in most countries47 that give extensive possibility for the upper limit on overtime to vary. By contrast in some countries where the upper limit on weekly overtime is supposed to be uniform, with only limited possibilities to bypass it through averaging mechanisms agreed upon in collective agreement, the median amount of paid overtime observed is higher than the binding limit – which points to rule evasion or lack of enforcement of the binding limit (this is the case in the Slovak Republic and Poland, see Annex Figure 5.A.2).48 More generally correlations between governance patterns and standard deviations in the median amount of paid and unpaid overtime are not statistically significant.

Finally, Figure 5.3 shows that the way that overtime rules are set are only one of the factors shaping actual overtime outcomes on the ground. There is no strong relationship between particular governance patterns and levels of incidence or average hours of paid overtime: irrespective of their governance patterns, there are countries below and above the OECD average for both incidence and average hours (see Figure 5.3 and Annex Figure 5.A.2). Figure 5.3 also shows that there is a large variation in the incidence and median hours of overtime actually measured within the groups of countries identified above for their similarities in terms of governance.

This last point is not necessarily surprising since governance patterns are based on information on overtime limits: variation in the incidence of overtime might be more directly related to variation in the rules for minimum compensation of overtime detailed in Annex Table 5.A.2. As shown in Panel C, the incidence of paid overtime is above average in Sweden and the United Kingdom, where there are no encompassing minimum compensation for overtime hours; it is the second highest in France, where a binding minimum compensation exists, but is the lowest of the OECD (at 110% of the normal rate, as in Italy). Similarly, the lowest incidence of paid overtime is observed in Mexico, where the existing binding minimum compensation is the highest in the OECD (at 200% of normal wage and 300% after 9 hours). However, the highest incidence is observed in Austria, where there is a binding minimum compensation that is comparable to the OECD average (at 150% of normal wage); and in Latvia, where the incidence is really close to that observed in Mexico, the minimum compensation is higher than average (200%), but it is not binding. In other words, variation in incidence appears at best partly related to variation in minimum compensation rules.

Beyond regulatory settings and the size of the overtime premium, many other factors are influencing the quantity of overtime work. Workers’ supply of overtime is likely to be correlated with both their position in the wage distribution and the shape of that distribution: on the one hand, working overtime may be a necessity to make ends meet for low-paid workers; Anxo and Karlsson (2019[6]) found for instance a positive correlation between the incidence of low-paid jobs and of paid overtime. On the other hand, the possibility to work paid overtime might not be available in the lowest-paid jobs,49 and be more frequent in higher-paid jobs. The tax treatment of overtime is likely to be another relevant factor – see e.g. Cahuc and Carcillo (2014[7]). Finally, social and cultural norms around overtime work are also likely to play a role.

5.1.2. Annual paid leave and public holiday

Regulatory settings of paid leave and public holidays across OECD countries

In the majority of OECD countries, employees are entitled to annual paid leave, e.g. to a period during which they can take time away from their work while continuing to receive their wage and remaining entitled to social protection. Workers can take a specified number of days or weeks of leave. Paid leave is available in addition to public holidays, sick leave, weekly rest, parental leave, etc. Annual paid leave, together with public holidays is an important factor for workers’ well-being and for preserving human capital,50 and a key determinant of the overall amount of working time each year. Paid leave can be regulated at different institutional levels, but is in general framed by national and international legislations (e.g. the EU Working Time Directive (Directive 2003/88/EC),51 the ILO Holidays with Pay Convention 132)52 that establish statutory minimum standards that can be further specified in collective agreements – at national, sectoral or firm level − or in the individual contract (for detailed content on statutory and negotiated paid leave and public holidays, see Annex Tables 5.A.4 and 5.A.5). Generally, the regulations on paid leave laid down in collective agreements are more generous than statutory entitlements (e.g. derogations to the law providing less generous leave are not allowed).

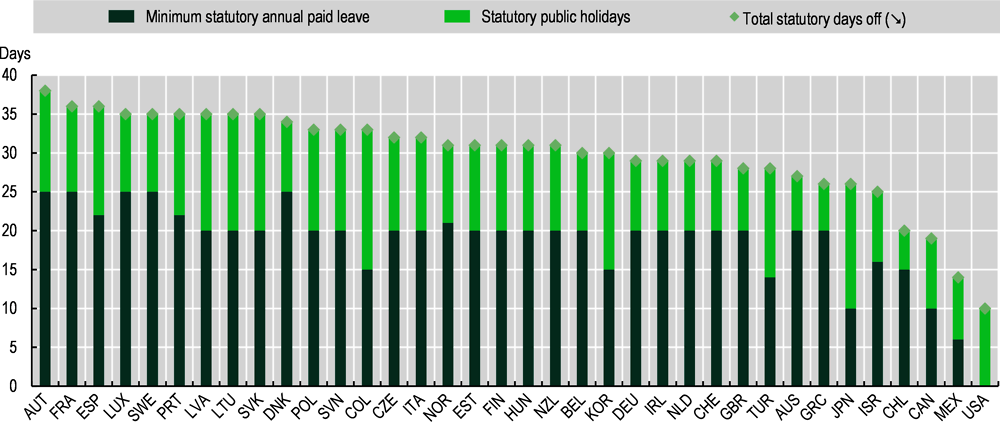

The minimum statutory amount of annual paid leave differs across OECD countries: while no statutory requirement exists in the United States,53 minimum entitlements vary from 6 days in Mexico to 25 days in some European countries.54 In many OECD countries, legislation sets a 20-day minimum entitlement. This is the case in Australia, New-Zealand, Switzerland and the majority of EU Member States in line with the EU Working Time Directive. In Austria, Denmark, France, Luxembourg and Sweden, the statutory minimum paid leave is 25 days, while in Portugal and Spain it is 22 days (Figure 5.4). The total amount of paid leave days may however depend on a number of factors, such as region, type of contract,55 occupation, years of service, sectors of the economy, or age. In many OECD countries, it increases with duration of service in the firm. In some countries (e.g. the Czech Republic, France, Sweden), access to paid leave may be granted before one year of service (see Annex Table 5.A.4). In many cases, these aspects are defined in collective agreements at various levels or determined in individual contracts.

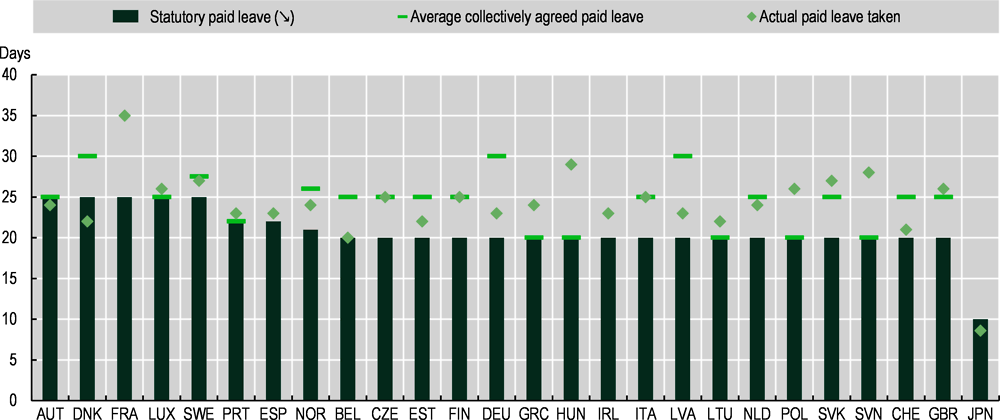

Data on negotiated paid leave are patchy, as collectively agreed rules are often too complex to allow producing even a rough general estimate. When available, data should thus be interpreted with caution given the diversity of rules applying. With these caveats in mind, data collected via the OECD Policy Questionnaire on Working Time Regulation and completed with information from Cabrita and Brandsma (2019[8]) on the most frequent clause on paid leave among all employees covered by collective bargaining, suggest that collective agreements can provide for substantially longer annual leave than the statutory provision (typically between 2.5 and 10 additional days,56 see Figure 5.5). In the Czech Republic, Finland, Italy, Latvia, Switzerland, the Slovak Republic and the United Kingdom, collective agreements typically provide up to 5 extra days per year. In the Netherlands, data suggest that workers covered by collective agreements generally benefit from 5.6 additional days of paid leave annually. In Sweden, negotiated annual paid leave is, on average 27.5 days long (i.e. 2.5 days longer than provided in the law). At 30 days, Denmark and Germany have the longest collectively agreed typical paid leave allowances, well above the statutory 25 days. In New-Zealand, 29% of employees covered by collective agreements have a higher entitlement to annual leave than the statutory minimum amount (Blumenfeld, Ryall and Kiely, 2015[9]).57 As mentioned above, collective agreements may grant even more days of paid leave in certain sectors58 or regions,59 sometimes depending on seniority.

In addition to granting extra paid leave, collective agreements often grant employees an influence over the timing of their leave (although the employer generally has the ultimate power to decide when paid leave is taken): this is the case for instance in the Czech Republic, Germany, Hungary or Sweden, where intensive consultation or even bargaining with the employees or their representatives is required on this issue. In Japan and Korea, an employer can refuse an employee’s choice of vacation days only if the normal operation of the enterprise would be disturbed.60 Generally, paid annual leave cannot be exchanged for financial compensation.

National public holidays come in addition to paid leave. These holidays may vary by year. While all OECD countries have a number of established public holidays (e.g. up to 18 days in Colombia), not all countries grant statutory paid public holidays (Figure 5.4).

In most countries, public holidays are set in legislation, and some61 or all of them are made into paid holidays; in some others, setting up the list of paid public holidays is left to collective bargaining at various levels, or to individual contracts. In the Netherlands or Sweden, for instance, collective agreements at national or sectoral level generally grant paid public holidays. In Japan, the United States and the United Kingdom, this is a matter for firm-level agreements or individual contracts. Furthermore, in some countries, derogations to the law exist that allow employers to require employees to work on a public holiday (e.g. in Belgium, Canada, France, Lithuania and New Zealand, see Annex Table 5.A.4), with financial compensation or time off. In Canada and New Zealand, for instance, employees working on a public holiday are paid 1.5 times their regular rate; in New- Zealand they are given another day off.

Paid leave regulation and leave actually taken

Figure 5.5 compares paid leave entitlements (both statutory and negotiated ones) and leave effectively taken by employees.62 Several insights emerge from this comparison. First, in all countries, except for Denmark and Japan, the average number of paid leave days actually taken is higher than the statutory minimum where it exists. The difference is particularly striking in France where the annual average number of days in paid leave was 35 in 2019, well above the statutory provision of 25 days, possibly due to the existence of negotiated paid leave63 and to the working time reduction scheme, Réductions du Temps de Travail (RTT).64 By contrast, in Japan, the average amount of paid leave taken is below the statutory provision (and well below the amount of leave effectively taken in other countries). In the United States, although there is no legally mandated paid leave, 85% of civilian workers have access to personal leave, sick leave, paid family leave, or vacation. Workers with consolidated leave plans (which provide a single amount of time off for workers to use for multiple purposes including vacation) have access to an average of 14 days of paid leave for their use after one year of service, while workers with no consolidated leave plan have access to an average of 9 days of paid leave for their use after one year of service65 (Bureau of Labour Statistics, US Department of Labor, 2019[10]).

Second, in countries where information on additional days provided through collective bargaining exists, two main patterns emerge: in a first group of countries (the Czech Republic, Finland, Italy, the Netherlands, Norway, Sweden and the United- Kingdom), the average amount of leave effectively taken is at or close to the negotiated provisions. In a second group (Belgium, Denmark, Estonia, Germany, Latvia and Switzerland), the amount of leave actually taken is below the negotiated provisions: in the case of Denmark and Germany, differences between collectively agreed paid leave (which are among the most generous in OECD countries) and average leave effectively taken are particularly marked. These patterns are however not straightforward to interpret as they do not account for the share of workers actually covered by collective agreements.

5.1.3. Teleworking

Regulatory settings of teleworking across OECD countries

While it prominently came to the fore during the COVID-19 crisis, teleworking (see Box 5.4 for a discussion about the different ways of defining the concept) had started being regulated in some OECD countries long before that. For instance, in European Union countries, the 2002 Framework Agreement on Telework signed by European social partners had led most signatory countries to define clear rules surrounding the practice of employees working away from the employers’ premises in laws or central collective agreements.

Since 2010, the issue of access to teleworking has been the object of reforms in several countries. For instance, in the United Kingdom, the Flexible Working Regulations Act of 2014 introduced the right to request flexible working arrangements (including teleworking) for all employees with at least six months of service (excluding agency workers). Employers’ ground for refusal was limited to business reasons. A similar reform was implemented in New Zealand in 2015, when an amendment to the Employment Relations Act allowed all employees (and not only, as was previously the case, those with caring responsibility) to request flexible work arrangements (including teleworking).

As of 2020, access to teleworking for workers is associated with different legal guarantees across OECD countries. In some, a statutory right to request teleworking is inscribed in the law; it can be more or less extensive (i.e. for all employees as in Spain or New Zealand or only for e.g. pregnant women, carers or workers with specific medical conditions, as in Lithuania), more or less conditional (i.e. enforceable for any reason as in the Netherlands, Portugal or the United Kingdom, or reserved to particular motives, e.g. work-life balance, as in Australia or Spain), and crucially, more or less enforceable, with limited possibilities for employers to refuse to accommodate employees’ requests in some countries, and no justifications needed for refusal in others, see Table 5.2. Where no statutory right to request teleworking exist, a majority of workers might be covered by a collective agreement effectively granting them this right, either at the national, sectoral or firm-level. By contrast, in a third group of countries, even though the possibility to telework might be inscribed in the law, the conditions of access to teleworking are left entirely to negotiation in individual contracts (or to firm-level agreements covering only a minority of workers).

In addition to guaranteeing workers a right to request teleworking, some countries aimed to encourage its development by introducing dedicated financial incentives for employers. In Poland, a 2014 amendment to the Act on Employment Promotion and Labour Market Institutions introduced grants for employers creating teleworking jobs for unemployed parents of a child under six years old, or for an unemployed carer who resigned from their previous jobs to take care of their child or dependant.

Different definitions of teleworking – and related cross-country data sources – are available for OECD countries. According to the most precise definition (found in Working Conditions Surveys) teleworking corresponds to situations where workers use information and communication technologies (ICTs) to work in a location other than the employer’s premises. Data sources based on this precise definition, however have a limited time coverage. Other data sources based on a looser definition of teleworking (which might not allow capturing the phenomenon as precisely) by contrast, allow analysing the evolution of the incidence of teleworking in OECD countries. Recognising the advantages and limitations of various data sources, this chapter uses several of them, on a case by case basis.

Teleworkers as “employees usually or occasionally working from home”: The EU-LFS data

The European Union Labour Force Surveys, compiled and harmonised by Eurostat, provide annual data on teleworking, defined as “employees working from home”, for European countries, Norway, Iceland and Switzerland, from 2000 onwards. They can be combined with data from the American Time Use Survey (ATUS) for the years 2003 to 2019. The underlying definition in the EU-LFS leads to a somewhat imprecise measure, since it excludes employees working remotely outside of their home but from another remote location not provided by the employer; it might also include employees working from home not using ICTs. However, this is the only comparable source that allows looking at the evolution of teleworking over time in these countries (over 20 years). In the chapter, the EU-LFS is used to compare the use of teleworking between countries by type of teleworking governance in the pre-COVID period (Figure 5.6), and the surge in teleworking during the COVID-19 crisis (Figure 5.7).

Teleworkers as “employees using ICTs always or most of the time, working in at least one other location than the employer’s premises several times a month”: Working Conditions Surveys

The European, American, and Korean Working Conditions Surveys all contain data on teleworking based on a comparable and precise definition, namely employees regularly using ICTs, and working in at least one other location than the employer’s premises several times a month. In addition, these sources are best adapted to an analysis of teleworking by socio-demographic groups, since they contain a rich array of other socio-demographic variables. The downside of using these sources is that there is only one data point (2015 for the European and American surveys, 2017 for Korea). In the chapter, these sources are used to compare the incidence of teleworking across groups (Figure 5.15).

Teleworkers as “workers working from home who were usually employed before the onset of the COVID-19 crisis”: The RePeAt data

The Representations, Perceptions and Attitudes on the COVID-19 crisis (RePeAt) survey collected data on workers working from home, at their usual workplace, or having stopped work altogether, as the first lockdowns went into effect in March and April 2020. It covered 11 OECD countries (Australia, Austria, Canada, France, Germany, Italy, New Zealand, Poland, Sweden, the United Kingdom and the United States) – see Foucault and Galasso (2020[11]) for more details. It is the only comparable source that allows measuring the incidence of teleworking (albeit loosely defined), during the first months of the pandemic. It also contains workers’ characteristics and can be used for analyses by groups. In this chapter, this source is used to look at the surge in teleworking during the COVID-19 crisis (Figure 5.7) as well as the profile of workers who teleworked in the first few months of the crisis (Figure 5.16).

Beyond access, regulations affecting working conditions of teleworkers have also evolved in many OECD countries in the last decade. For instance, the issue of who bears the cost of the teleworking equipment has been the object of regulations (often court decisions): in 2020 (in a case dating back from 2019 and the pre-COVID period) the Swiss Federal Supreme Court ruled in favour of an employee’s request to have her employer compensate her for teleworking costs. Similar judgments were pronounced e.g. in California, where employers have been required to reimburse a reasonable percentage of employees’ phone and internet costs. In Canada, the government introduced the possibility for those working from home to deduct employment expenses from their taxable income.

As of 2020, regulations of the working conditions of teleworkers were more or less extensive across countries, ranging from rules about the process of establishing teleworking arrangements (for instance that it has to be voluntary, reversible, etc.) to anti-discrimination provisions, rules about employers’ liabilities for occupational safety and health, working schedules and overtime, data privacy and cyber-security, and the cost of equipment and maintenance. These legal frameworks are sometimes set up in dedicated laws, or included in general labour laws (as in Australia, Chile, Greece, Lithuania, Portugal, Spain and Turkey, as well as Belgium and Italy for occasional teleworking) or in national or sectoral collective agreements (as in Austria, Denmark, France, Estonia, Greece and Belgium and Italy for regular teleworking). In some countries, there are no specific laws or provisions nor collective agreements, but the usual labour protection provisions apply to teleworkers without distinction (this is the case e.g. in Finland, Germany, Latvia, the Netherlands, Slovenia, Sweden, the United Kingdom and the United States).

Considering the regulation of these two main aspects e.g. access to teleworking and the working conditions of teleworkers, four patterns of teleworking governance are identified across OECD countries in 2020,66 which are summarised in Table 5.2:

In Australia, Austria, Italy (in the case of occasional teleworking, or “agile work”),67 Lithuania, the Netherlands, Portugal, Spain,68 Sweden, and the United Kingdom, there is an enforceable right to request teleworking − granted in the law or in collective agreements covering a large part of the workforce in Austria and Sweden – for at least for some categories of workers. Teleworkers’ working conditions are defined in an encompassing69 legal framework.

In Denmark, Norway, Canada70 and New Zealand, there is an enforceable right to request teleworking (centrally negotiated in Norway, and statutory in Canada and New Zealand). But rules on working conditions are left to lower level negotiations and there are no binding legislation or higher level agreement on the issue (although there might be non-binding guidelines).

In Italy for regular teleworking, Belgium,71 as well as Chile, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Japan, Latvia, Poland, Slovenia, Turkey and the United States, there are either no right to request teleworking or unenforceable ones (with unlimited reasons for employers to refuse employees’ requests). Yet working conditions for teleworkers are laid out in encompassing legal frameworks.

Finally, in the Czech Republic, Hungary, Israel, Korea, Mexico, the Slovak Republic and Switzerland, the issue of access to teleworking is left entirely to individual contracts or firm-level agreements, and legal frameworks specifying teleworkers’ working conditions are either very minimalistic, or entirely absent.

Teleworking regulation and the use of teleworking before the COVID-19 crisis

Despite the changes in regulations discussed above, the take-up of teleworking in OECD countries had, until the outbreak of the COVID-19 crisis, remained rather limited. In the EU in 2015, according to European Working Conditions Survey data, only 3% of employees regularly worked from home, a further 5% “highly mobile” employees worked regularly from several locations (including home), and another 10% of workers occasionally worked from home. These numbers increased only modestly over the years, going up from 7.4% of employees on average across European Union countries for which data are available (see Figure 5.6) in 2000, to 13.5% in 2019 (according to EU LFS data).

These differences in the use of teleworking across OECD countries might be partly attributable to the patterns of regulation identified above – although caution should be applied in drawing strong conclusions here. As shown in Panel A, Figure 5.6 the incidence of teleworking has been rising since 2000 in countries where an enforceable right to request teleworking exists (except in Lithuania). In most countries with no enforceable right to request teleworking and no encompassing legal framework, the incidence of teleworking had been stagnating below 10% since 2000. Finally, the incidence of teleworking was highest on average − and most steadily rising since 2000 − in countries where access to teleworking is granted trough collective bargaining, while it was below average (but rising) in countries where access is statutory − with the exception of the United Kingdom and the Netherlands in recent years. This is not really surprising when considering that in almost all countries where the right to request teleworking is statutory, this right does not apply to all workers but only to specific categories of workers.72 By contrast, the right to request teleworking, when negotiated through collective bargaining, often is more encompassing.