1. Exploring the VAT/GST implications of the sharing/gig economy as part of the platform economy – a broad perspective

This chapter provides the overall context of this report, most notably the explosive growth of the sharing/gig economy, its key features and the main business models that are considered relevant from a VAT/GST perspective, and the associated possible VAT/GST challenges and opportunities. It also describes the objective and the scope of this report.

The digitalisation of the economy via advanced technology has transformed the way people supply and consume goods and services. Particularly, the emergence of a so-called ‘sharing/gig economy’ signals a paradigm shift from ownership to the temporary access-based use of human or physical resources and/or assets, primarily by and among individuals for a consideration.

While the notion of ‘sharing’ assets and/or resources as a socio-economic model may not be entirely new, the recent technological developments, notably the rise of digital platforms that provide advanced technological solutions and trust building tools, have dramatically facilitated the expansion of the sharing/gig economy by increasing the accessibility to these assets and resources and the capability of users to transact with each other with great flexibility, trust and convenience and also by reducing information asymmetries and various transaction costs.

The prominent role of digital platforms in the sharing/gig economy has been recognised by the 2019 OECD report on the Role of Digital Platforms in the Collection of VAT/GST on Online Sales (the 2019 Digital Platforms report) (OECD, 2019[1]), which provides practical guidance to tax authorities on the design and implementation of a variety of solutions for digital platforms in the effective and efficient collection of VAT/GST on online sales. The 2019 Digital Platforms report acknowledged however that, within the platform economy, the sharing/gig economy has specific characteristics that required further evaluation and analysis (OECD, 2019[1]).

The exponential growth of the sharing/gig economy activity as facilitated by the digital platforms has revolutionised the commercial reality in a number of sectors, particularly in transportation (with the emergence of “ride-sourcing”) and accommodation (particularly short-term (vacation) rental) sectors. This new reality, involving large groups of new economic actors carrying out their commercial activities in new ways that may not yet be captured by traditional tax rules and administrative practice, may impact VAT/GST revenue, policy design and administration and the competitive position of traditional business activity.

Given the need to further evaluate the issue and to consult with relevant stakeholders on the role(s) of sharing/gig economy platforms in the VAT/GST compliance process in respect of the sharing/gig economy supplies, the OECD Working Party No.9 on Consumption Taxes (WP9) consisting of VAT/GST policy officials from OECD members and Partner countries, signalled a need to develop work in this area as a separate work stream. This work was expected to consider the sharing/gig economy within the context of the broader platform economy and to consider specific features and aspects that may affect the design and operation of the roles for digital platforms in the collection of VAT/GST as presented in the 2019 Digital Platforms report (OECD, 2019[1]).

This request for further OECD work in this area was widely echoed at the meeting of the Global Forum on VAT in March 2019, where tax authorities from around the world expressed the urgent need for work by the OECD on the VAT/GST treatment of the sharing/gig economy. Participants flagged the potentially significant impact on VAT/GST revenue, on tax administration and on the competitive position of traditional business activity as key drivers for this work. This call for work on the VAT/GST treatment of the sharing/gig economy was strongly supported by Business at OECD, through its membership in the Technical Advisory Group to WP9 (TAG). The OECD’s Committee on Fiscal Affairs (CFA) and the OECD Council confirmed the importance of this work by including it as a priority in the CFA’s Programme of Work and Budget for 2019-20.

Against this background, the OECD has developed this report with the active involvement of all relevant key stakeholders, including the business community and countries beyond the OECD membership via the Global Forum on VAT.

1.1.1. The objective of this report

It is recognised that the sharing/gig economy gives rise to a variety of economic, social, tax, legal and regulatory questions beyond VAT/GST policy design and administration and compliance. While this report considers the possible impact of these various aspects on VAT/GST policy and administration and vice-versa, where appropriate, it focuses exclusively on the VAT/GST aspects.

Accordingly, the overall objective of this report is to enhance tax authorities’ understanding of the sharing/gig economy from an economic and commercial perspective, identify and analyse the opportunities and challenges it creates for VAT/GST policy and administration and to suggest the possible policy approaches and measures that tax authorities could consider in this context.

The underlying assumption is that tax authorities may wish to monitor and consider the VAT/GST implications of the sharing/gig economy in light of their specific circumstances and policy objective(s). The policy objective may not necessarily be to bring (all) sharing/gig economy supplies within the VAT/GST net.

This report does not aim at prescription for national legislation. Jurisdictions are sovereign with respect to the design and application of their laws. Rather, the report seeks to enhance jurisdictions’ understanding of this evolving phenomenon and assist the tax authorities in evaluating and developing possible policy responses to address the VAT/GST implications of the growth of the sharing/gig economy, with particular guidance to maximising the effectiveness of such measures and to the extent possible their consistency across jurisdictions. International consistency will assist to facilitate compliance, lower compliance costs and administrative burdens and improve the effectiveness of the VAT/GST systems, recognising in particular that a number of the sharing/gig economy actors, notably digital platforms, are likely to be faced with multi-jurisdictional obligations.

Considering the sharing/gig economy as part of the broader platform economy but with specific characteristics, this report complements the 2019 Digital Platforms report (OECD, 2019[1]). It intends to be evolutionary in nature, notably in light of the rapid development of technology and a wide range of activities involved and their delivery processes.

1.1.2. The scope of this report

This report discusses the key features of the sharing/gig economy and its business models that are likely to be relevant from a VAT/GST perspective and presents a range of possible policy responses to address the impact of sharing/gig economy growth on VAT/GST policy and administration. These responses include potential roles for digital platforms involved in the sharing/gig economy supply chain as well as broader policy and administration options.

In evaluating available VAT/GST policy approaches against the key VAT/GST relevant features of the sharing/gig economy, this report takes into account the potential policy objectives pursued by a jurisdiction as well as the desirability for a jurisdiction to consider the Ottawa Taxation Framework Conditions, notably in respect of neutrality, efficiency, certainty and simplicity, effectiveness and fairness, and flexibility in framing and implementing the policy and administrative measures.

The report relies as appropriate on the International VAT/GST Guidelines (OECD, 2017[2]) and other relevant OECD work in response to the digitalisation of the economy, notably the 2019 Digital Platforms report (OECD, 2019[1]) and the 2020 Model Rules for Reporting by Platform Operators with respect to Sellers in the Sharing and Gig Economy (OECD, 2020[3]). Experience and analysis in jurisdictions that have taken VAT/GST measures in respect of the sharing/gig economy or that consider doing so, have informed this work and vice versa, as part of the ongoing sharing of analysis and experience.

While recognising that the growth of the sharing/gig economy may create different VAT/GST pressures, depending on the sector as well as jurisdictions’ market structure and their VAT/GST system, evidence suggests that the accommodation and transportation sectors currently create the most urgent pressure on VAT/GST policy in jurisdictions worldwide and are therefore likely to require the most urgent and/or most extensive policy and/or administrative action from a VAT/GST perspective. The accommodation and transportation sectors are therefore used as pilot sectors for the analysis of the operation of the sharing/gig economy, respectively based on the sharing of assets and the sharing of labour (see further Annex D to this report). The analysis of these two sectors is expected to be helpful in informing the analysis in respect of the other sharing/gig economy sectors as appropriate.

The report endeavours to use neutral terminology rather than terminology that may already be used in specific jurisdictions or may have a different meaning across jurisdictions. It is important, therefore, for jurisdictions to take account of the broad meaning of the terms used in this report.

The report does not try to define the term “sharing/gig economy” as it is a concept that is likely to evolve over time. A number of different terms have been used in the literature as well as by jurisdictions that have either implemented policy actions to address the VAT/GST implications in this area, or are considering doing so. It has resulted in a unique set of nuances and challenges, not least for policy makers trying to measure its size and impact and identifying appropriate policy responses. Hence the report uses the term “sharing/gig economy” as a generic term to refer to part of the platform economy that has a number of specific features that are considered relevant from a VAT/GST perspective. Considering such specific features and building on already available definitions, a broad (working) description is used as a placeholder for the purposes of this report to refer to the sharing/gig economy as: “An accessibility-based socio economic model, typically enabled or facilitated via advanced technological solutions and trust-building tools, whereby human or physical resources and/or assets are accessible (for temporary use)/shared – to a large extent – among individuals for either monetary or non-monetary benefits or a combination of both”.

In general, sharing economy activities notably involve the temporary substitution of ownership of (sometimes) underutilised assets/resources as opposed to the transfer of ownership such as sharing of one’s apartment for short-term (vacation) rental purposes or sharing of a tool (equipment) for a manual work. Gig activities are in principle aimed at providing opportunities to a (high or low) skilled labour force to provide labour and/or professional services in the context of a labour market characterised by the prevalence of short-term and often non-standard contracts or freelance work as opposed to permanent jobs and standard labour contracts (c.f. Tax Challenges Arising from Digitalisation – Interim report 2018 of the OECD/G20 Base Erosion and Profit Shifting Project (OECD, 2018[4])). These gig activities could include cleaning, gardening or more intellectual services such as web design, IT services and consultancy. The distinction between sharing and gig categories is not always clear-cut (e.g. the case of a driver that has spare capacity in his/her car and offers to take passengers who want to travel to the same direction for a fee). Sharing/gig economy actors may often offer a mix of asset and labour sharing activities.

This report recognises that the VAT/GST status of sharing/gig economy actors (including platforms and underlying providers) in a given jurisdiction will generally be determined by that jurisdiction’s normal VAT/GST rules, often on a case-by-case basis in light of specific facts and circumstances. This includes the question whether a sharing/gig economy platform acts as a principal or as an agent for VAT/GST purposes (see Box 1.2. below). The new main challenges for VAT/GST policy and administration result from the large numbers of new economic actors that may enter the VAT/GST system as a result of sharing/gig economy growth. These new actors may often have a limited VAT/GST knowledge and/or capacity to comply (i.e. micro-businesses, SMEs) while their activities may involve considerable VAT/GST revenues and create risks of competitive distortion that are limited at an individual level but may be significant at an aggregated level. The aim of this report is primarily to identify and analyse these challenges and to present a range of possible options for tax policy and administration to address them.

1.2.1. The rapid growth of the sharing/gig economy on a global and regional level

The rapid growth of the sharing/gig economy is a global phenomenon. A range of major sharing/gig economy platforms are operating across multiple jurisdictions worldwide. As the sharing/gig economy continues to evolve, and given the complexity and variation of the platforms and activities involved, there are not yet a great deal of data available that provide a reliable insight into its true size. The collection of statistical data to measure its size, growth and activity has proven to be challenging but efforts are being made to develop a framework and methodology to improve the measurement of the sharing/gig economy. Despite these difficulties, available evidence suggests that the sharing/gig economy has significantly grown and expanded globally in recent years with significant potential for further growth in the future. A 2019 study covering the major markets around the world suggests that sharing/gig economy activity was worth USD 204 billion in 2018 and is projected to reach USD 455 billion by 2023 as consumers are becoming more receptive to the idea of sharing and as digitalisation accelerates (Mastercard and Kaiser Associates, 2019[5]).1

The sharing/gig economy is constantly evolving. The Covid-19 pandemic (see Annex B for further analysis) together with other developments in the regulatory domain (e.g. developments in labour law that could reshape the relations between the platforms and their providers) and in the technological landscape (e.g. the potential use of self-driving cars in the future) could transform the scope and scale of the sharing/gig economy both at national and global level. Hence there is a need for continuous monitoring of developments in this area.

Emerging key sectors of the sharing/gig economy

Given its versatile nature, the sharing/gig economy can potentially involve a wide range of activities across different sectors of the economy. Box 1.1. below describes the four emerging key sectors of the sharing/gig economy.

Transportation sector: typically, the platform connects drivers, who may be non-professional in the sense that they may not possess professional permits (e.g. taxi medallion) other than a legitimate driver’s license, with passengers, often private individuals, for either a short or long distance trip. It is noted that jurisdictions increasingly implement measures that require drivers to obtain professional permits to operate, notably in an online ride-sourcing context (see further in Annex D).

Accommodation sector: typically, the platform connects potential guests with professional or non-professional hosts offering accommodation services. Increasingly, the platform may offer other services such as air travel, car rentals and vacation experience either on their own name or on behalf of other platforms and/or third parties (see further in Annex D).

On-demand services sector: typically, the platform enables (often) private individuals to locate high or low-skilled labour force with spare capacity to provide labour and/or professional services. The services could include (skilled) manual work such as cleaning, moving, carpentry that mostly involve physical delivery and professional services such as web design, consultancy, legal, IT, data entry, ‘click-work’ that mostly involve digital delivery.

Collaborative finance, including crowdfunding, lending and donations: typically, the platform connects individuals and businesses to invest, lend and borrow money directly between and from each other without the involvement of traditional financial institutions such as banks. These mainly include crowdfunding platforms and peer-to-peer lending platforms (either individual-to-individual consumer lending or investor to SMEs and/or start-ups lending).

Source: OECD research based on public sources

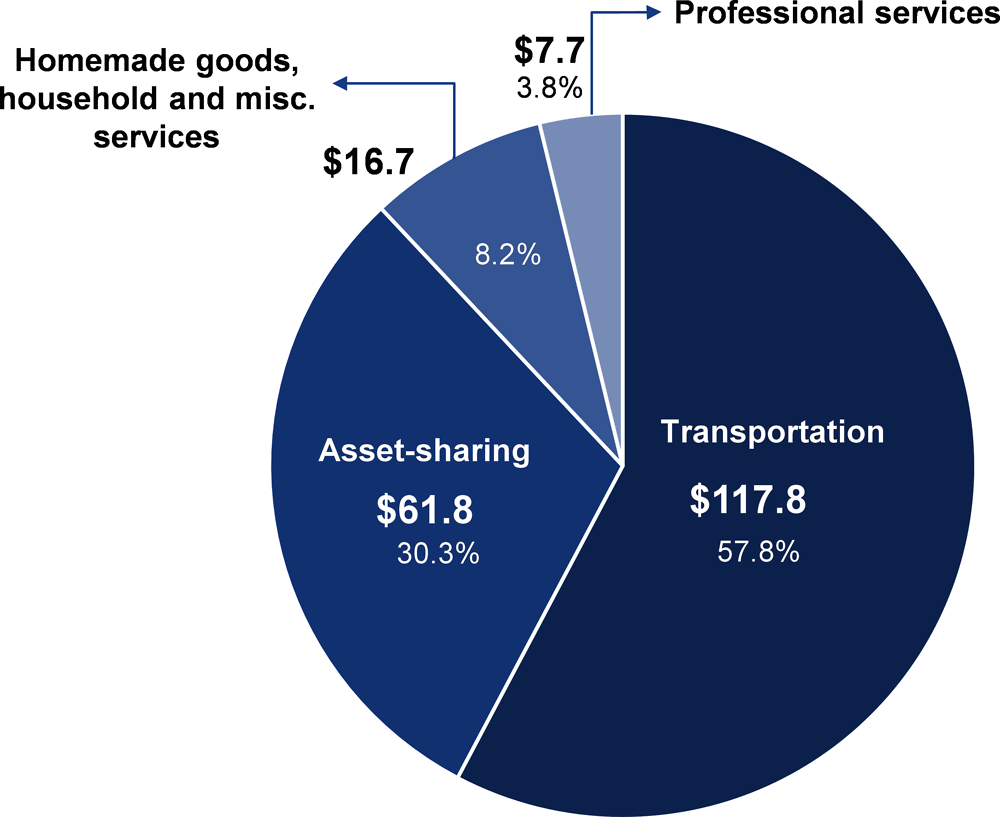

Among these sectors, evidence suggests that the accommodation and transportation sectors are the two largest sectors in terms of total transaction value. These sectors collectively represent approximately 90% of the total sharing/gig economy market value globally (see Figure 1.1. below).

It is projected that the growth rates of the current two largest sectors (i.e. transportation and accommodation) will remain high in the coming years as these two sectors continue leading the market. Sub-business models in the transportation sector, such as the delivery model (e.g. food delivery; shopping delivery), are also expected to grow rapidly as major ride-sourcing platforms are continuing to expand into these areas, leveraging their well-established network of drivers to differentiate their service offerings (see further description of sub-business models in Annex D). The professional services sector and the crowdfunding/lending sector are two other sectors with considerable growth expectations.

The sharing/gig economy in emerging economies

The sharing/gig economy is also in full expansion in the developing world where it is often very visible in daily life. A global survey conducted by Nielsen in 2014 indicated that people in developing countries are more receptive to the idea of sharing assets than those in developed regions: Asia-Pacific (78%); Latin America (70%); Middle East Africa (68%); Europe (54%) and North America (52%) (Nielsen, 2014[6]).

Evidence suggests that developing markets represent greater potential for gig economy growth in particular, in light of the often significant interest for freelance (“gig”) work among their growing populations. Paired with increasing mobile phone penetration and rising digital banking access, such emerging economies are projected to represent a greater portion of the global gig economy in the future with their accelerating freelancer participation rates (Mastercard and Kaiser Associates, 2019[5]).

The dominant sectors of the sharing/gig economy businesses operating in low and middle-income countries include motorbike taxi services; connecting freelance workers with potential clients; agriculture-related activities, notably involving the sharing of information on crop prices, agricultural disease risks and treatments, or the sharing of agricultural equipment and storage or processing facilities (e.g. by connecting farmers who own tractors with farmers in need of them).

While global platform giants that operate across multiple countries are also expanding their services in developing economies, some of the typical sharing/gig economy platform services have been replicated locally, and regionally dominant platforms have emerged, catering for region-specific needs and circumstances.

1.2.2. Drivers of the sharing/gig economy

The recent proliferation of the sharing/gig economy activities in the past decade has been largely driven by the advances in technology, enabled to a large extent by digital platforms that offer enormous potential to scale fast, increase the scope and frequency of transactions with reduced transaction costs and increased accessibility combined with enhanced trust assurance and ease of connection and payment.

In addition to the technological developments, available studies and evidence suggest that there are various social and economic factors that drive the growth of the sharing/gig economy. One key factor is the high market demand, i.e. consumers’ interest in the sharing/gig economy products/services and the desire to monetise (under)utilised existing uses of assets that has attracted significant levels of private funding especially in certain sectors e.g. ride-sourcing.

Another factor is the changing economic behaviour, notably in the aftermath of a financial and economic crisis, whereby people are seeking ways to save and earn supplemental income while embracing a more “flexible” work-life environment. This attitude is more profound amongst younger people. Evidence shows that individuals providing labour-intensive services are typically from the lower end of the income spectrum, while those providing capital-intensive services have higher average monthly incomes.

In addition, the absence of (adapted/targeted) regulation may play a role. One of the drivers for the growing popularity of the sharing/gig economy is arguably the low barrier to enter the sharing/gig economy, notably as a consequence of the absence of (adapted/targeted) regulation, allowing consumers and providers to switch roles easily and quickly. This means in practice that individuals may easily opt for a regular (full-time) activity, making the sharing/gig economy activities their primary source of income, or irregularly at a lower frequency (part-time) to supplement other income. This flexibility to determine when to supply services can be of great value, as it reduces the opportunity cost of working and increases efficiency. It may have positive well-being effects by allowing sharing/gig economy participants to work a few more hours or renting out an asset, and thus loosen their budget constraints and expand their opportunities.

Other social factors could include increased environmental concerns. People may consider the sharing of underutilised assets as an effective way to reduce waste and to engage in a more environmentally friendly and sustainable economy. Moreover, people may associate the sharing/gig economy with social initiatives, such as empowering communities and improving access to a variety of goods, services, and facilities that would otherwise be unavailable or restricted to large businesses or high income households. Development of a sharing mentality among younger people is an additional factor driving the change.

1.2.3. Business models operated by digital platforms in the sharing/gig economy – An overview

As indicated before, digital platforms are at the forefront of sharing/gig economy development and growth as they employ advanced technology to connect providers and users of a continuously growing variety of sharing/gig economy services. The digital platforms involved in the sharing/gig economy activities cover a broad spectrum, ranging from small start-ups focusing on a specific niche to global giants. New sharing/gig economy platforms are continuously emerging and their business models continue to evolve. Even within the same sector, variations of different business models may operate.

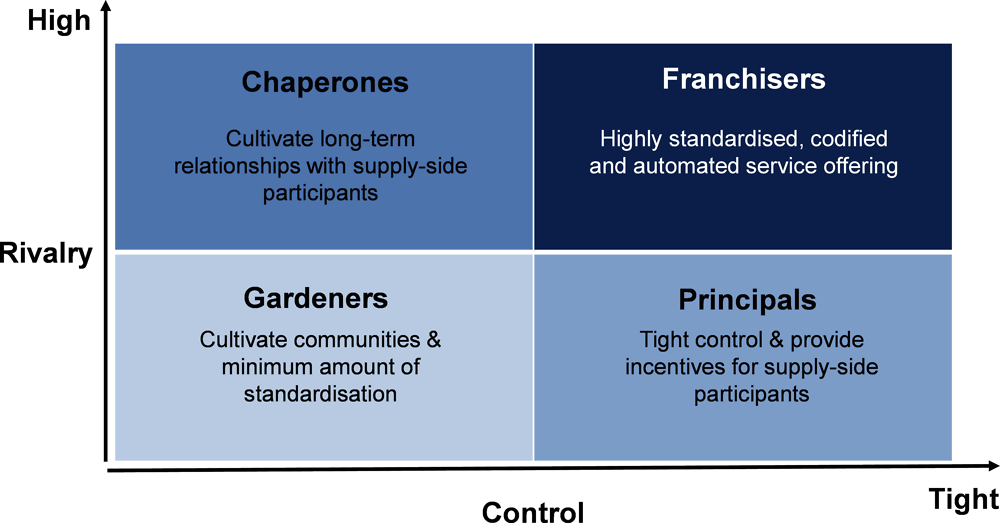

Figure 1.2. below illustrates four typical business models operated by sharing/gig economy platforms categorized on the basis of their “control” and “rivalry” dimensions as follows:

The “control element”, i.e. the level of control exercised by the platform operator (e.g. whether the platform dictates the terms of the service delivery), will often differ among platforms. For example, a platform may exercise a high degree of control over the entire service delivery (e.g. acting in the name of the provider or reselling the service, managing content and sales, matching providers with users through a centralised app, dictate the price); or the platform may exercise a loose control and act more like an overseer of the platform rather than a supervisor, in which case the platform controls the user experience on the platform, but the underlying supply and its terms are controlled by and contracted between the provider and the user. It orchestrates the participants’ efforts and it gains a competitive advantage by cultivating long-term relationships with supply-side participants. Despite the differences in business models, all platforms appear to exercise control to some extent as it is in their own interest to streamline the services to facilitate the transaction and create optimal experience for customers.

Additionally, the “rivalry element”, i.e. the degree to which a market mechanism operates in the platform, may also differ among platforms. For example, users may be allowed to set their own prices based on recommendation by the platform algorithm that takes into account supply and demand; or prices may be set on the basis of a dynamic pricing algorithm that reflects changes in supply and demand, or on the basis of predefined categories rather than on dynamic adjustments. The providers may be obliged to apply prices as determined by the platform (typically used by ride-sharing/car-pooling platforms).

From a VAT/GST policy perspective, it may be useful to note that these variations in business models within sectors may have an impact on the degree of control that a platform operator exercises over the supply/users of the platform; the information collected by or available to the platform; the payment flows for the sharing/gig activities facilitated by the platform. Annex D provides a more detailed description of the business models operated by the major platforms in the two largest sharing/gig economy sectors, i.e. the accommodation and transportation sectors, including the key features of these platforms and functions performed.

Evolution and convergence of business models

Increasingly, as digital platforms operating in the sharing/gig economy scale up, it is not uncommon to see a platform facilitating a variety of services based on different business models. For example, a ride-sourcing platform may facilitate a ride-sharing/car-pooling service, matching drivers with passengers going in the same direction and sharing the costs of the ride. Equally, some platforms, notably in the accommodation sector, are facilitating platform-to-platform supplies that allow the host platform to provide (an access to) a wider range of offerings by other platforms or third parties to the final consumer.

At the same time, another important trend observed is the ongoing convergence between sharing/gig economy activities and business models and the broader (traditional and platforms) economy. In order to remain competitive, traditional economic operators that are faced with competition from sharing/gig economy operators have started adjusting and expanding their offering to compete with this new reality. This could include launching their own applications on existing platforms, launching competing platforms and/or acquiring existing platforms. In addition to creating online distribution channels to compete with sharing/gig economy platforms, traditional operators may also differentiate their service offerings. Existing hotel brands have for instance started to offer apartment and homestays. Similarly, sharing/gig economy platforms continue to expand their services and are starting to resemble their traditional counterparts in certain cases (e.g. platforms in the accommodation sector moving towards owning and controlling accommodation). At the same time, sharing/gig activity may create new capacity, e.g. people acquiring assets with the sole purpose of offering them for short-term rental through a platform instead of using underutilised assets. These trends may gradually reduce the difference between sharing/gig economy actors and other economic operators in the traditional and/or the broader platform economy.

It is recognised that the sharing/gig economy gives rise to a variety of economic, social, tax, legal and regulatory questions beyond the area of VAT/GST administration and compliance. The analysis in this report, however, focuses exclusively on the VAT/GST implications of sharing/gig economy growth, thereby taking account of evolutions in these various other areas on VAT/GST policy and administration and vice-versa, where appropriate.

To further analyse the VAT/GST implications of the sharing/gig economy, section 1.3.1. below first further explores and distils the specific features of the sharing/gig economy that are relevant for VAT/GST policy design and administration. Section 1.3.2. considers the main actors in a sharing/gig economy supply chain and analyses their interactions that are likely to be relevant from a VAT/GST perspective. This is complemented with a sectoral typology based on the key operational features of sharing/gig economy activities in Section 1.3.3. The broad VAT/GST opportunities and challenges associated with sharing/gig economy growth are finally analysed in Sections 1.3.4. and 1.3.5., in light of what is discussed in the preceding sections.

1.3.1. Key features of the sharing/gig economy that are relevant for VAT/GST policy design and administration

As the sharing/gig economy continues to evolve rapidly and new business models emerge and converge with existing business models, it is increasingly difficult to draw the line between sharing/gig economy activities and other activities in the broader economy. Nevertheless, the sharing/gig economy has specific characteristics compared to the broader platform economy that merit further evaluation and analysis from a VAT/GST perspective.

Digital platforms are at the forefront of sharing/gig economy growth, by connecting providers and users through advanced technological solutions and trust-building tools such as online reviews, reputation mechanisms and secure online payment systems (see Annex D for a further overview of platform features). For the digital platforms involved in the sharing/gig economy, these tools are essential features as the need for quality assurance, verification, optimisation of customer experience and payment security is crucial for their success.

The underlying activities in the sharing/gig economy are generally not new (e.g. transport services, accommodation rentals), but the rise of sharing/gig economy platforms powered by digital technology has enabled their scale, scope and frequency to reach an unprecedented scale at global level. Some of these activities may have been typically untaxed or non-taxable under existing VAT/GST regimes (e.g. the exploitation of an asset by a private individual). The scope of these sharing/gig activities is potentially limitless as long as technology is capable of supporting interactions between providers and interested customers.

Sharing/gig economy providers are often private individuals2 that may carry out high numbers of low-value (“micro”) transactions, particularly in gig economy sectors such as transportation (ride-sourcing). These individual providers may undertake the sharing/gig economy activities to supplement their primary source of income and their engagement may thus be of an infrequent/occasional nature and be spread across multiple platforms.

These providers may often use assets that they also use partly for private purposes. These (private individual) providers are often likely to have no or limited knowledge of VAT/GST obligations and may not have the capacity to comply with these obligations even if they are aware of them. Moreover, the profile and status of sharing/gig economy providers is diverse and in constant evolution. While private individuals acting in a self-employed capacity with an often higher-than-average level of income volatility may represent a large share of sharing/gig economy providers, it does not exclude that their activities may just as easily be performed by individuals that have incorporated their business activity and/or that are less exposed to income volatility, or that these providers’ relationship with a platform evolves to one that may become akin to an employer-employee relationship under some business models (These aspects are further considered in section 1.3.2 below).

Platform technology allows these providers to easily access large numbers of potential customers with no or minimal upfront investment. The sharing/gig economy can thus potentially transform a large number of individuals operating through a platform into businesses (possibly with global coverage) that can collectively compete with the (largest) traditional economic operators. For example, the large numbers of private individuals that are now offering their property for short-term rental via accommodation platforms have become real competitors for the traditional hotel sector. The line between a private individual and a business thus becomes increasingly difficult to draw.

Sharing/gig economy platforms may often have no physical presence in the jurisdiction where the transactions that they facilitate are carried out (performed and/or used or consumed). The providers of the sharing/gig economy activities generally have a presence in the jurisdiction where these activities are performed and/or carried out. This presence may involve the physical presence of the provider in the taxing jurisdiction (e.g. driver’s presence in the ride-sourcing sector) or may be limited to the presence of provider’s assets in the taxing jurisdiction (e.g. immovable property of a certain value to be located in the taxing jurisdiction). Providers may temporarily move across jurisdictions to engage in sharing/gig economy activities (e.g. frontier workers or people who stay in a jurisdiction for a couple of months to undertake a sharing/gig economy activities) even though these cases are rare. While users and providers of sharing/gig economy activities may often both have a physical presence in the jurisdiction where these activities are performed and/or consumed at the time of this performance or consumption (e.g. the transportation services or the short-term rental), this is not necessarily always the case (notably where services can be provided remotely) and providers and users may have their usual residence or business establishment in different jurisdictions.

Sharing/gig economy activities generally involve the (temporary) use of resources (assets and/or labour) without involving any transfer of ownership of assets. These activities could involve renting, swapping and sharing of assets; either for a fee or against compensation of the cost of the activity proportionate to the use of the asset (cost-sharing arrangements). Sharing/gig economy activities may also be performed for a non-monetary consideration (i.e. in-kind compensation).

Certain types of the sharing/gig economy activity may however no longer involve the “sharing” of excess capacity as described above but evolve towards a more traditional type of service activity, facilitated by a digital platform. Take the example of a driver who leases out a car that (s)he did not have before in order to offer rides, versus a driver that may have spare capacity in his/her car and plan on driving particular route with passengers who want to travel on the same route. The same is true for (underutilised) assets in the accommodation sector: it may become increasingly less clear whether a short-term rental activity relates to a (temporarily) underutilised property, or whether the property has for instance been acquired as an investment and is predominantly offered for short-term rental.

Payments in the sharing/gig economy are typically made through electronic means of payment (e.g. credit cards, e-banking, bitcoins, etc.) with or without the involvement the platforms (payment processing can be outsourced to third parties). This widespread usage of electronic means of payment could enhance the access to data to facilitate the tracing and monitoring of sharing/gig economy activities and/or to relevant data for VAT/GST compliance in respect of the sharing/gig economy supplies (incl. to support platforms taking on these compliance obligations on behalf of the sharing/gig economy suppliers). Evidence suggests that cash payments are still accepted in certain sectors and/or by certain operators, especially in developing economies.

1.3.2. Identifying the key actors/interactions that may be relevant from a VAT/GST perspective – A basic scenario of the sharing/gig economy supply chain

Determining the role/status of the actors involved in the sharing/gig economy supply chain is an important element when considering the VAT/GST treatment of a sharing/gig economy supply. Building on the key VAT/GST relevant features of the sharing/gig economy, Box 1.2. below provides an illustration of a basic scenario of the sharing/gig economy supply chain and potential interactions among the key sharing/gig economy actors with additional considerations from a VAT/GST perspective.

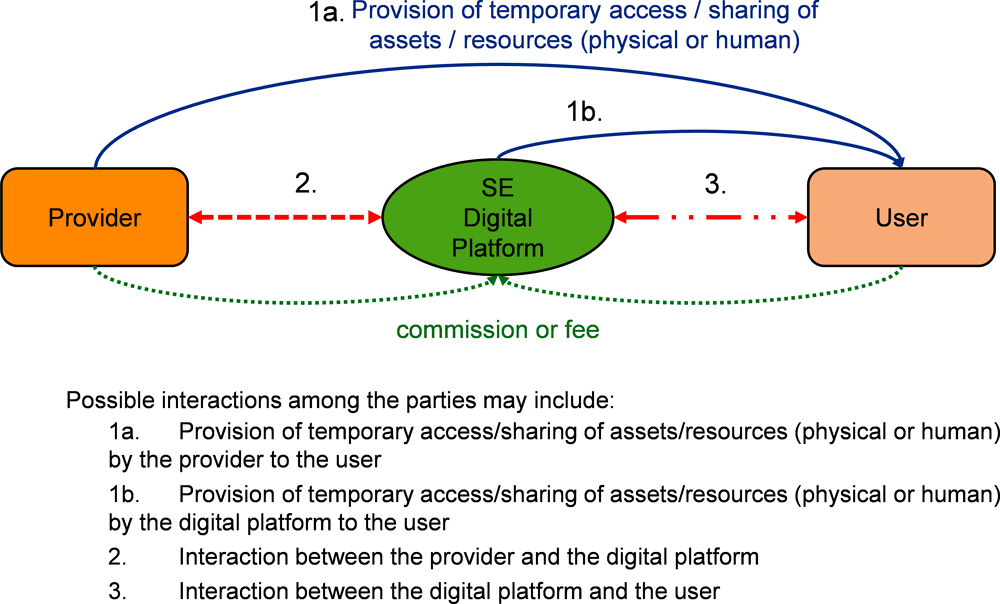

Although there are many different sectors in which sharing/gig economy platforms operate, and their business models vary, a sharing/gig economy transaction will typically involve the following different group of actors/participants, which may not necessarily be located in the same jurisdiction:

The provider1 (often a private individual) who shares assets, resources, time and/or skills in exchange for a consideration/fee (monetary);

The user of these assets, resources, time and/or skills. Often the user is a private individual, but users with a business status cannot be excluded particularly in certain sectors (e.g. the accommodation and/or on-demand services sectors).

The sharing/gig economy platform (SE Digital Platform) that enables access to advanced technology and trust building tools and allows providers to be connected with other users for the provision of sharing/gig economy supplies, directly or indirectly, to such users. Several terms may be used at national level to denominate these actors, including: “platforms”, “(online) marketplaces”, “electronic interfaces” or “intermediaries”.

With respect to the role of the digital platform in the supply chain, two main broad scenarios can be distinguished:

Under scenario 1 (illustrated with arrow 1a on the diagram), the sharing/gig economy platform directly connects the provider(s) and the user(s) with respect to a sharing/gig economy supply. In return, the digital platform may receive a consideration/fee from either the provider or the user or both (the “agent role”).

Under scenario 2 (illustrated with arrow 1b on the diagram), the platform first acquires the sharing/gig economy supply from the (underlying) provider and then it provides it in its own name to its user(s). Under this scenario, the platform is regarded by national legislation as the supplier of the service (the “principal role”). Often, these platforms contract with the individual underlying provider and they act as the contracting party to provide the service.

In determining the exact role/status of the digital platform and the underlying providers, it is recognised that national labour law may have an impact. This is particularly the case where the platform is considered to have a legal or de facto employment relationship with the (underlying) provider under national labour law. Under such circumstances, the platform may be considered as having provided the supply in its own name and on its own behalf (i.e. acting as principal) and the underlying provider may be considered as an employee.

Other actors can also be involved in the supply chain of a sharing/gig economy activity, with direct or indirect connection to the digital platform and/or the provider and/or the user. For example, in the food (meal) delivery activities, different providers may be involved in the preparation of the meal and subsequently in the delivery of the meal to the customer. In the accommodation sector, an agent may directly interact with a platform with respect to the listing of apartments that may belong to different owners who are not necessarily known to the platform.

1 Even though the sharing/gig economy may involve supplies between (large) businesses, the focus of the analysis is particularly on the involvement of private individuals as this may trigger questions with respect to their treatment from a VAT/GST perspective.

Source: OECD analysis.

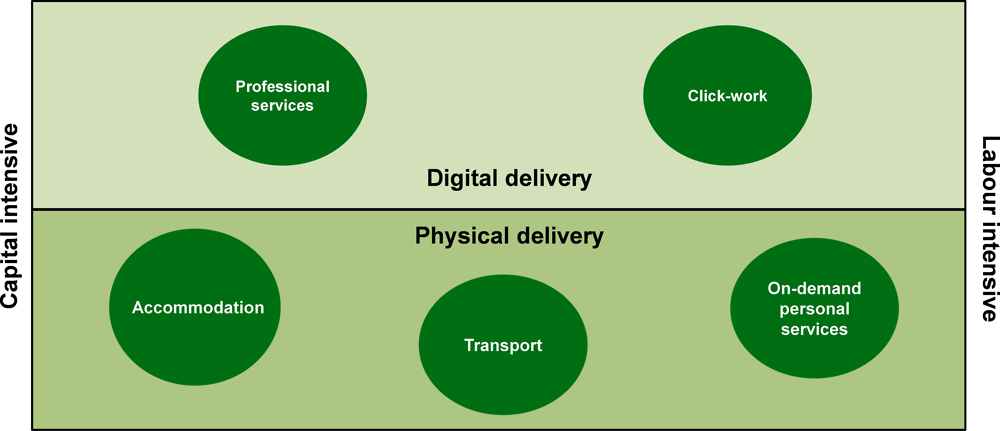

1.3.3. A sectoral typology based on VAT/GST relevant operational features

Sharing/gig economy activities are diverse and constantly evolving. The impact of these activities on VAT/GST policy and administration may be equally diverse and tax authorities’ policy responses may need to be tailored to take account of the specific features of sharing/gig economy activity. In structuring their policy analysis and design process, it may be helpful for tax authorities to categorize the main sharing/gig economy operators and/or sectors on the basis of a set of key operational features that are likely to be relevant from a VAT/GST perspective. Figure 1.3. below suggests such sectoral typology based on sharing/gig economy activities’ reliance on capital and/or labour (capital intensive vs. labour intensive) and on the mode of service delivery (digital or physical delivery). As will be discussed further in this report, these features are likely to be relevant for VAT/GST purposes, e.g. digitally delivered activities may be more likely to have cross-border aspects (could for instance be delivered remotely); capital-intensive activities may involve higher value transactions and actors that are more likely to have the capacity to comply with their tax/regulatory obligations.

1.3.4. Broad VAT/GST opportunities

The growth of the sharing/gig economy can create opportunities to facilitate and enhance VAT/GST compliance and administration and offer potential to broaden the VAT/GST base. These opportunities arise in particular from the central role of a relatively limited number of sharing/gig economy platforms in stimulating and facilitating these activities through advanced technology and data analytics. The crucial role of big data and enhanced data analysis in the sharing/gig economy business models provides considerable opportunities for greater visibility and traceability of economic activity, for formalisation of previously informal economic activity, and for more efficient tax collection and compliance.

Potential positive impact on the VAT/GST base

The sharing/gig economy is an enabler for potentially enormous numbers of individuals, often with no or limited investment, to mobilise their labour and/or assets for financial gain. The sharing/gig economy thus has the potential to expand a jurisdiction’s tax base by enhancing economic activity beyond the simple substitution of an existing type of activity by a new one, by creating new markets, and/or drawing new actors in the economy. The reality is, however, more complicated. Depending on the design of a jurisdiction’s VAT/GST system, the growth of the sharing/gig economy may present both an opportunity for growth and a threat to the VAT/GST base (see the section on VAT/GST challenges/risks further below).

The development of the sharing/gig economy also creates considerable opportunities to formalise activities that were not previously within reach of the VAT/GST net. One of the key drivers of the sharing/gig economy is the rapid expansion of digital connectivity via mobile devices and the strong growth of secure solutions for mobile payments. More generally, the sharing/gig economy is primarily data and technology driven. As the sharing/gig economy continues to expand and cover increasing shares and segments of economic activity, these key features are likely to create unique opportunities to reduce the cash-driven informal economy and considerably expand the formal sector, not least in developing economies.

Opportunities to increase efficiencies for tax administrations and sharing/gig economy providers

Sharing/gig economy business models and the technologies employed by the sharing/gig economy platforms are likely to provide opportunities for tax authorities to increase the efficiency of administration and collection of the tax. Beyond the opportunities for data collection and increasing the efficiency of tax collection through the involvement of the platforms (further discussed under Chapter 3), the sharing/gig economy is likely to create opportunities for tax administration to enhance the efficiency of risk-based compliance management and audit strategies, notably through systems checks at the platform level rather than carrying out audits for each individual provider. In addition, the technology-based and data-driven operation of sharing/gig economy platforms offers opportunities to significantly facilitate VAT/GST compliance for sharing/gig economy providers and to reduce these providers’ compliance costs (discussed under Chapter 3). Indeed, sharing/gig economy platforms are already working closely with tax administrations in a growing number of countries to leverage these emerging opportunities (including by sharing data/information to support providers’ VAT/GST compliance).

1.3.5. Broad VAT/GST challenges/risks

This section of the report discusses a number of VAT/GST challenges created or exacerbated by the growth of the sharing/gig economy. These challenges and risks may notably include the possible erosion of a jurisdiction’s VAT/GST base resulting from the shift in economic activity from a relatively small number of largely tax compliant long-established traditional businesses to large numbers of new relatively small business actors (incl. non-standard workers) that may often be less compliant and/or not be subject to taxation because their activity remains below a VAT/GST exemption threshold. In addition, the varying and ever-evolving business models and types of interactions between sharing/gig economy actors may often make it particularly challenging to determine the VAT/GST nature and status of these actors and their activities and to determine and implement a proper VAT/GST treatment.

The growth of the sharing/gig economy as a (potential) threat to the VAT/GST base

Depending on the design of a jurisdiction’s VAT/GST system, the growth of the sharing/gig economy may present both an opportunity for growth (discussed above) and a threat to the VAT/GST base. While VAT/GST is a broad-based consumption tax levied on most goods and services, many jurisdictions have chosen to relieve individuals and micro-businesses from the requirement to register and/or charge and account for the tax when their activities remain below a certain materiality threshold. These exemption thresholds differ from jurisdiction to jurisdiction, and differences may exist between sectors within a given jurisdiction, e.g. to minimise competitive distortion risks. In these jurisdictions, depending on the type of activity, many of the sharing/gig economy providers are likely to remain below the exemption threshold and thus be relieved from registering and/or charging VAT/GST and not contribute directly to a jurisdiction’s VAT/GST revenue.

This may have an adverse effect on a jurisdiction’s VAT/GST revenues, where activities carried out by traditional economic actors, which are VAT/GST registered and contribute to a jurisdiction’s VAT/GST revenues, are replaced by large numbers of sharing/gig economy actors, which are below the VAT/GST registration threshold and do not contribute directly to VAT/GST revenue. This may trigger a risk of VAT/GST base erosion that may be more or less important depending on a country’s economic structure and the activities involved. In the accommodation sector, for example, the sharing/gig economy may reduce the number of bookings at traditional hotels in favour of bookings with providers that are not VAT/GST registered, thus reducing the VAT/GST revenue from the hotel sector. This may increasingly create serious challenges especially for jurisdictions with a large tourism industry. Similarly, in the transportation sector, the sharing/gig economy may negatively affect the traditional taxi industry actors and reduce the VAT/GST revenue from these actors as drivers may find it easier and more flexible to switch to the sharing/gig economy activities, notably in cases where these are less regulated than their traditional counterparts.

Identifying the VAT/GST status and role of sharing/gig economy providers is not always straightforward

Identifying the VAT/GST status of the providers/users is important not only to determine economic operators’ potential VAT/GST compliance obligations but also their entitlement to associated rights, in particular their right to input VAT/GST deduction.

While acknowledging that it is for a jurisdiction’s national VAT/GST law to determine whether the providers of the sharing/gig economy supplies are regarded as taxable persons for VAT/GST purposes, evidence suggests that it becomes increasingly difficult to draw the line between a private individual and a taxable business for VAT/GST purposes in the sharing/gig economy. Drawing this line becomes even more challenging as in a number of cases private individuals may not (only) make use of underutilised assets/resources to develop a sharing/gig economy activity, but acquire assets with the sole purpose of exploiting them for a new economic activity (e.g. drivers purchasing cars to provide ride-sourcing services, individual owners purchasing apartment units for rental purposes only, etc.). This triggers a number of compliance and administration challenges and risks discussed further below.

Evidence suggests that many of the providers of the sharing/gig economy supplies are likely to be unknown to the VAT/GST authorities as well as be unaware of their VAT/GST obligations, or of the fact that they could benefit from simplifications to facilitate VAT/GST compliance. VAT/GST compliance risks are likely to arise from these providers’ unfamiliarity with VAT/GST obligations and low level of and/or limitations to their capacity to comply. Risk analysis on the basis of data provided by sharing/gig economy platforms has confirmed these compliance risks in certain jurisdictions. These risks are likely to vary across jurisdictions and sectors, depending on a range of aspects including the VAT/GST framework (e.g. level of thresholds), its complexity, the quality of taxpayer services, compliance culture, prominent sharing/gig economy sector(s) and the profile of its providers.

Identifying the VAT/GST status of underlying providers is also an important compliance issue for sharing/gig economy platforms as it may affect their own VAT/GST obligations, including in respect of the VAT/GST treatment of fees and commissions (notably in the context of cross-border activities) and in respect of their reporting obligations (invoicing, etc.). For instance, if the transaction between the platform and the underlying sharing/gig economy provider is considered a business-to-business (B2B) supply, many jurisdictions require the VAT/GST on the commissions/fees charged by the platform to the provider to be accounted for on a reverse-charge basis when the platform is not located in the taxing jurisdiction. If the transaction is treated as business-to-consumer (B2C) supply, the platform may be required to register in the taxing jurisdiction (via a vendor registration system). To address this challenge, some platforms operate a webpage through which providers can inform the platform of their personal tax status. However, platforms often experience difficulties in verifying the underlying providers’ VAT/GST registration information, notably in the absence of a reliable, real-time verification mechanism of such information operated by tax administrations.

In cases where VAT/GST registration or collection thresholds apply, the platforms may encounter additional challenges in determining whether a particular underlying provider is above or below the threshold. Particular challenges arise from the fact that underlying providers may often engage in multiple sharing/gig economy activities through multiple platforms and/or when an agent (e.g. a local booking agency) operates on a platform on behalf of multiple individual providers without making these providers’ information known or visible to the platform.

The VAT/GST treatment of the sharing/gig economy activities

As illustrated in Box 1.2. above (under section 1.3.1), determining the VAT/GST treatment of sharing/gig economy activities requires the determination of the status of two main groups of interactions:

the interactions between the sharing/gig economy platform and its users (the providers/users of the underlying activities); and

the interactions between the sharing/gig providers and users of these activities.

In determining the VAT/GST treatment of sharing/gig economy activities, it is thus important to identify the role and status of the actors involved in the sharing/gig economy supply chain (platforms, underlying providers, users, any other third parties such as payment service providers) as well as the type of their supplies. All these aspects have an impact on the overall treatment of the supply for VAT/GST purposes, including determining the place of taxation, notably for cross-border supplies as appropriate (c.f. International VAT/GST Guidelines Chapter 3 (OECD, 2017[2])).

This may not always be straightforward (e.g. by simple reference to the VAT/GST treatment of similar traditional economic activities). The varying and ever-evolving business models and types of interaction(s) among the actors in the sharing/gig economy (especially, the providers and the digital platforms) have an impact on the nature of these activities and/or supplies and therefore their VAT/GST treatment.

In this context, it is critically important to determine whether the platform acts as a “principal” or as an “agent” in the sharing/gig economy supply chain, as described and illustrated in Box 1.2. under section 1.3.1. above). This determination will impact the VAT/GST treatment of the supplies involved and the associated compliance obligations for the various actors. This could include the following treatments (illustrative and non-exhaustive):

Where a platform is considered acting as a principal, it will normally be considered as the provider of the underlying sharing/gig economy supplies to the final customers for VAT/GST purposes (e.g. transportation services). It is then for the platform to comply with all the associated VAT/GST obligations. This may notably apply where the platform acts in its own name towards the sharing/gig activity customers. This will in principle also apply where the labour model underpinning the relationship between a platform and its users has been challenged by authorities as constituting a de facto employer/employee relationship. Where the platform is considered acting as a principal, it may be considered as having received that same supply from the underlying sharing/gig economy provider and having supplied it onwards to the final customer. The VAT/GST treatment of this supply will notably be determined by the status of the underlying provider (including whether it acts as an independent contractor and whether its activities are above the VAT/GST exemption threshold that may be applicable in the relevant jurisdiction).

Where the platform is considered acting as an agent, it may be considered as supplying digital/electronic services to its providers/users. The fees/commissions charged by the platform to their underlying providers/users are then treated accordingly for VAT/GST purposes, in jurisdictions where specific rules have been implemented for digital/electronic services.

Alternatively, the services provided by the platform to its providers/users may be considered as “intermediation services”, consisting of connecting sharing/gig economy providers with their customers and facilitating their interaction. These services are then treated accordingly for VAT/GST purposes.

These services may in certain cases be considered to be of the same nature with the sharing/gig economy supply by the underlying provider to the customer (e.g. considered as transportation or real estate rental services) and therefore trigger the same VAT/GST treatment.

Where cross-border supplies are involved, a different characterisation/treatment of those supplies among jurisdictions may result in cases of double and/or unintended non-taxation.

Other (third) parties can also be involved in the supply chain of a sharing/gig economy activity with direct or indirect connections to the digital platform and/or the provider and/or the final customer (end-user). This may further complicate the determination of VAT/GST treatments and obligations. For example, in the accommodation sector a real estate agent may represent a number of (individual) owners in advertising their properties on a digital platform (or multiple platforms) without these owners being known to the platform(s) (see in Annex D for an overview of other third parties that may operate in the accommodation sector).

Even within the same sharing/gig economy sector, the VAT/GST treatment of a sharing/gig supply may differ depending on the business model. This could be for instance the case for ride-sourcing for a fee and ride-sharing/car-pooling under a cost-sharing arrangement, where the determination of the consideration for the sharing/gig economy activity in a cost-sharing context (e.g. passengers pay a contribution to the estimated costs of the trip to the driver) may lead to different VAT/GST consequences. Similarly, the involvement of a consideration in-kind (e.g. in the case of exchange of houses in the accommodation sector) may create challenges notably in determining the taxable value.

Finally, as the platforms increasingly expand their offerings that may include a combination of different services/supplies (e.g. rental plus insurance) as well as non-sharing/gig economy activities either on their own or through other platforms or third parties, identifying the VAT/GST nature of these different types of (packaged or complex) services can present further challenges.

Input VAT/GST deduction challenges/risks

Sharing/gig economy providers often use assets that they also partly use for private purposes. This has great relevance for VAT/GST purposes, as input VAT/GST deduction is in principle limited to business inputs. No VAT/GST deduction is allowed for tax incurred on items used for private consumption. This raises obvious input VAT/GST deduction (and refund) risks for tax administrations, as it may be difficult to control whether many relatively small individuals have made the correct deduction. It may also raise compliance challenges for eligible providers, as it may be difficult to determine the actual amount of deductible input VAT/GST.

Tax administration and audit challenges

The rapid growth of the sharing/gig economy and the equally strong growth of self-employed sharing/gig economy workers and providers of services and assets may, over time, confront VAT/GST authorities with the challenge of dealing with large numbers of potentially new taxpayers, with a relatively small turnover and minimal knowledge of VAT/GST and other regulatory obligations and low willingness to comply. These actors may not always be visible to the tax authorities and, indeed, they may not even be located in the taxing jurisdiction.

Against the above, the tax authorities are likely to become confronted with the difficult challenge of balancing the need to protect revenue and minimise competitive distortions, which may point towards including large numbers of sharing/gig economy workers in the VAT/GST system, with the demands for an efficient tax design and administration, which may point towards limiting the number of “new” VAT/GST registrations from the sharing/gig economy, notably through high registration thresholds. This may also create pressure on tax authorities to consider alternative approaches and innovative mechanisms for the collection of tax relevant data and the VAT/GST, including through the enlistment of sharing/gig economy platforms in the VAT/GST compliance process in respect of the transactions they facilitate. Possible approaches in response to this challenge are discussed in detail under Chapter 2 and 3 of the report.

Impact on compliant operators in the traditional economy

Uncertainty around the VAT/GST treatment of sharing/gig economy actors and activities may (and is likely to) have an adverse impact on a jurisdiction’s compliance culture and create competitive distortion against compliant actors in the traditional economy, notably where the sharing/gig economy actors can benefit from a price advantage caused by a de facto preferential VAT/GST treatment.

This chapter has illustrated that sharing/gig economy growth can present both challenges and opportunities for VAT/GST policy and administration. It can exacerbate existing VAT/GST pressures and opportunities and/or create new ones. These pressures and opportunities are likely to differ across jurisdictions, depending on multiple factors that include the size and growth of the sharing/gig economy at national level, a jurisdiction’s overall VAT/GST system, tax administration’s capacity and a jurisdiction’s compliance culture. Chapter 2 of this report discusses possible steps for tax authorities to consider in developing a strategy in response to the impact of the sharing/gig economy on their VAT/GST policy and administration. Chapters 3 and 4 of the report present a detailed technical discussion of the various VAT/GST policy options available to tax authorities in response to sharing/gig economy growth within their jurisdiction.

References

[7] Constantiou, I. (2017), “Four Models of Sharing Economy Platforms”, MIS Quarterly Executive, Vol. 16/4, https://aisel.aisnet.org/misqe/vol16/iss4/3 (accessed on 25 February 2021).

[5] Mastercard and Kaiser Associates (2019), The Global Gig Economy: Capitalizing on a ~$500B Opportunity, Mastercard and Kaiser Associates, https://newsroom.mastercard.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/Gig-Economy-White-Paper-May-2019.pdf (accessed on 25 February 2021).

[6] Nielsen (2014), Is Sharing the New Buying?, Nielsen, https://www.nielsen.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2019/04/global-share-community-report-may-2014.pdf (accessed on 25 February 2021).

[3] OECD (2020), Model Rules for Reporting by Platform Operators with respect to Sellers in the Sharing and Gig Economy, OECD , Paris, https://www.oecd.org/tax/exchange-of-tax-information/model-rules-for-reporting-by-platform-operators-with-respect-to-sellers-in-the-sharing-and-gig-economy.htm (accessed on 25 February 2021).

[8] OECD (2019), An Introduction to Online Platforms and Their Role in the Digital Transformation, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/53e5f593-en.

[1] OECD (2019), The Role of Digital Platforms in the Collection of VAT/GST on Online Sales, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/e0e2dd2d-en.

[4] OECD (2018), Tax Challenges Arising from Digitalisation – Interim Report 2018: Inclusive Framework on BEPS, OECD/G20 Base Erosion and Profit Shifting Project, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264293083-en.

[2] OECD (2017), International VAT/GST Guidelines, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264271401-en.

Notes

← 1. The geographical coverage of the report focuses on Australia, Brazil, France, India, Indonesia, United Arab Emirates, United Kingdom and the United States. For the purposes of the report, the gig economy comprises of four sectors: asset-sharing (including accommodation), transportation-based services, professional services and handmade goods, household and miscellaneous services (HGHM).

← 2. Sharing/gig economy activities may also involve supplies between large businesses to exploit (under)utilised capacity and generate substantial efficiency gains in respect of various input factors, primarily real capital. However, focus of the analysis is particularly on the involvement of private individuals in the sharing/gig economy supplies as this may trigger questions with respect to their treatment from a VAT/GST perspective.