4. Developing the supply of innovation leadership in Brazil’s federal administration

This chapter looks at how the supply of innovation skills can be further developed in the pool of current and potential leaders in Brazil’s federal administration. More specifically, it looks at the emergence of competency-based training across the federal administration, at the efforts to improve the administration’s knowledge about existing skills and subsequent gaps, and about the National School of Public Administration’s role in developing leadership skills and competencies. The second part of the chapter identifies some levers to improve the learning culture across the administration, such as the development of networks and partnerships and innovative ways of developing skills.

The statistical data for Israel are supplied by and under the responsibility of the relevant Israeli authorities. The use of such data by the OECD is without prejudice to the status of the Golan Heights, East Jerusalem and Israeli settlements in the West Bank under the terms of international law.

“Supply and demand” is one of the foundational tenets of economics with the goal to seek equilibrium to produce healthy and sustainable economies. The same concept can be applied to leadership competencies such as those discussed in Chapter 3. There needs to be a supply of people with the right competencies ready to take up leadership positions in the government. This suggests the need to provide learning and development opportunities to leaders and to the potential pool of leaders, whether inside the civil service or beyond. However, this supply also has to be matched with a commensurate demand for these skills from those who take appointment decisions. Balancing supply and demand of leadership skills is at the core of senior civil service (SCS) systems. Without this balance, a country is unlikely to have an effective and sustainable leadership system and risks overinvesting in certain areas while not seeing the expected returns.

Much of the interventions so far established in Brazil focus on the “supply” side of skills and competencies – development opportunities for current and future senior leaders. This chapter looks at how the supply of innovation skills can be further developed in the pool of current and potential leaders. More specifically, it will look at the emergence of competency-based training across the federal administration, at the efforts to improve the administration’s knowledge about existing skills and subsequent gaps, and about the National School of Public Administration’s (Escola nacional de administração pública, ENAP) role in the skills and competencies development landscape. The second part of the chapter identifies some levers to improve the learning culture across the administration, such as the development of networks and partnerships and innovative ways of developing skills.

Skills and competencies in Brazil’s federal administration: An overview

In Brazil’s civil service, formal training (in particular academic education) tends to be used as an indicator of skill and capability, including for senior leaders. Academic training in a relevant field is usually one of the few criteria to assess candidates’ suitability to access the positions in the civil service. The 2019 decree1 on the “Criteria, Profile and Procedures to Appoint DAS and FCPEs” underlines once more that any appointment (Senior Direction and Counselling Group [Grupo Direção e Assessoramento Superiores, DAS] or “commissioned functions” [funções comissionadas do poder executivo, FCPE]) in the federal administration should be primarily based on a good reputation, relevant professional experience and academic qualifications.

The importance of academic degrees in the federal administration overall has been increasing over the past 20 years. Between 2000 and 2018, the number of federal civil servants with an academic degree2 increased from 49% to 75% (ENAP, 2018). Among the OECD countries that collect data on the level of civil servants' education, in 2015 in Chile 39% of employees in the central administration held an academic degree,3 61% in Australia and Estonia, 62% in Sweden, and 82% in Israel.4 The strong increase in the academic qualifications of Brazilian civil servants is a consequence of the retirement of civil servants without or with less academic qualifications, but also of an increase of people’s qualifications in the overall job market (ENAP, 2018).

After entering the federal administration, leaders and civil servants continue to have access to training opportunities. However, without information about the existing skills and competencies within the system, it is challenging for the federal administration to develop a systematic approach to development.

In this context, training decisions tend to be driven by individuals’ motivations and interest. Without individual or organisational planning, training does not always align with someone’s relevant responsibilities nor with organisational needs. As training is self-driven and bespoke, it can lead to the exploration of new skills and competencies that generate innovative ideas. Conversely, it can also create an environment in which it is hard to practice and evolve these skills and competencies outside of the classroom and can cause a misalignment with the true needs of the individual, organisation and system. Even when training involves bringing workplace issues into the classroom to create a strong link between work and the training, it is still difficult to replicate workplace conditions such as coalition building, political will and convincing co-workers that may be against the idea.

It is also challenging to address skills gaps. For example, the innovation skills survey conducted for this report (see Chapter 2) highlights that a vast majority of respondents from the federal administration want to improve their skills in at least one of the six areas assessed by the survey5 (see Figure 1.4 in Chapter 1). Almost 99% of senior civil servants and around 95% of the other categories surveyed responded “Yes” to the question “Do you want to improve your skills in the above-mentioned areas?”.

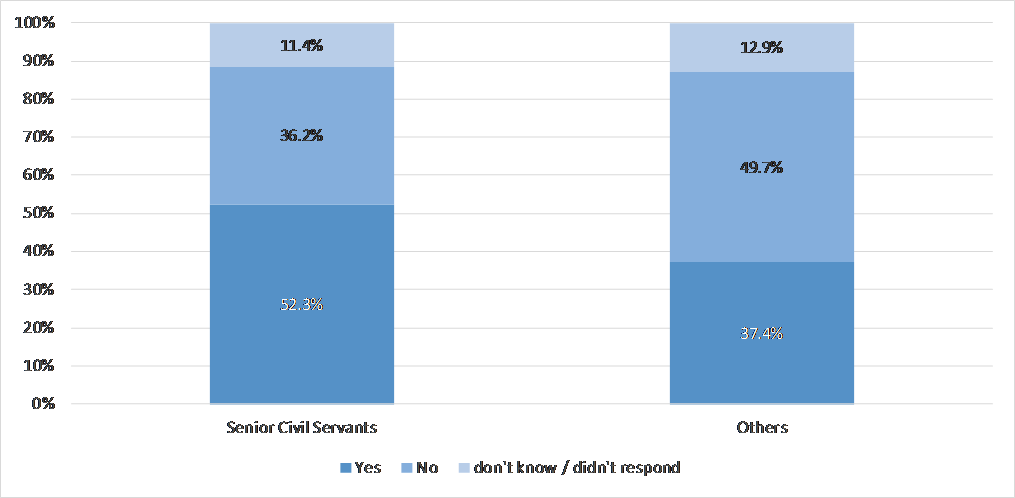

Despite the overall interest for developing one’s own skills for innovation, when questioned about the existing opportunities to improve those skills, responses suggest that there is still space to either increase those opportunities, or to improve communication about existing opportunities in the federal government (Figure 4.1). Only 52% of senior civil servants who want to improve their skills consider that they have opportunities to do so. This percentage decreases to 37% for other civil servants. The percentage of respondents who do not know whether there are opportunities available is equivalent in both groups (11% and 12%).

Identifying and mapping current leadership competencies

Supply-side interventions first require a competency mapping to identify the existing supply. Competency mapping ensures that the skills and competencies are readily identified and available when there is demand. It also helps to better align development initiatives to ensure they are addressing real gaps.

To start addressing this challenge, the former Ministry of Planning, in partnership with ENAP and others, has developed a data bank that has the potential to serve this purpose. This type of initiative has already been used in some of the Brazilian federal administration organisations that carry out selective procedures for appointed positions, like the Bank of Brazil. These internal data banks include information about professional competencies of civil servants who can potentially be qualified for appointed positions (Camões and Balué, 2015) and score potential candidates according to their experience and training. This could be a way to pre-qualify potential civil servant candidates for certain positions. The current database - Sigepe Talent Bank - can potentially start cross-referencing the existing civil service databases to compile more variables, such as skills developed outside work.

The Sigepe Talent Bank is a platform serving as a skills database for public servants. Public servants can upload their curriculum vitae into the system. The skills information is accessible to any public servant, allowing for a greater understanding of the skills and competencies within teams, organisations and the government as well as more targeted recruiting and hiring based on knowledge, expertise and experience.

This platform was created following a partnership between the Ministry of Economy and the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq). The CNPq is responsible for the Lattes Platform, which is a single information system for curricula vitae, and widely used amongst academics and researchers in Brazil.

As more civil servants (and possibly non civil servants in the future) put their data into the system, the higher the potential for better analysis of careers, skills and experiences, to help the federal administration make better training programmes, improve hiring decisions and facilitate the recruitment of qualified candidates.

Source: Interviews, Governo federal (2019), Portal do Servidor, https://www.servidor.gov.br/servicos/faq/banco-de-talentos-perguntas-frequentes

By becoming an online repository of civil servants’ skills, competencies and experiences, the Talent Bank initiative could help to begin systematising the leadership competency supply which currently exists within the civil service, to ensure that those looking for talent are able to reach beyond their own networks to find it. This may be an important step towards breaking down the reliance on personal networking which currently appears to dominate selection and appointment processes. At the same time, if the database remains exclusive to civil servants, it may reduce the visibility for people who are not civil servants but whose skills could be relevant for DAS positions.

Some OECD countries have been testing similar approaches. The Talent Cloud is one of the most ambitious projects of the government of Canada: this programme aims to become a validated, searchable repository of cross-sector talent (Box 4.2).

The government of Canada proposed to restructure government workforces to meet the changing needs of citizens in complex environments. In this context, Natural Resources Canada set out to test a new form of workforce planning – the GC Talent Cloud. The central idea was that the GC Talent Cloud would become a new digital platform of pre-qualified talent with a competency validation process and easy searchability. Free Agents was one of its earliest pilots to test the feasibility (including market viability, efficiency savings, psychological stress on workers in the gig economy, competency modelling and screening design) of a new type of workforce.

The objectives of the pilot were threefold:

-

1. demonstrate the benefits of the cloud-based free agency model for human resources

-

2. support, develop and retain talented public servants

-

3. increase the capacity of the public service to innovate and solve problems.

As many different types of work could benefit from the model, Natural Resources Canada’s Innovation Hub chose to forego the choice of a specific background or skill set for Free Agents. Instead, the Innovation Hub developed a set of attributes and behaviours that the public service innovation community considered valuable for innovation and problem solving in their organisations. These attributes formed the basis for the pilot’s screening process.

Candidates who successfully demonstrate these core attributes are offered lateral deployments to positions in a special unit of the Natural Resources Canada Innovation Hub. Because of the lateral deployment model, there is flexibility in the selection process and assessment methodology. Deployments do not need to have clear priorities or undergo a competitive process for appointment.

The Free Agent pilot tracks performance, project outcomes, costs, risks and benefits in order to make broad, data-driven recommendations about the long-term viability of the potential full-scale GC Talent Cloud model. Work is underway to develop a profile of skills and competencies useful for innovation in the public service. Once developed, this profile will provide the framework for Free Agents to pursue training and learning opportunities.

Source: OECD (2018a), Embracing Innovation in Government: Global Trends 2018, https://www.oecd.org/gov/innovative-government/embracing-innovation-in-government-2018.pdf

In parallel, the former Ministry of Planning has conducted a census of civil servants from the specialist in public policy and government management career. In partnership with the National School of Public Administration, in the second half of 2018 the Secretary of Management undertook a Demographic and Professional Trajectory Census of specialists in public policy and government management, in order to better understand who government managers are, where they are and what results they have helped to achieve in the federal public administration. This census is expected to provide better knowledge of the civil servants from this career, their career paths, experience and skills.

The emergence of competency-based leadership training in Brazil

More information about the available skills should help Brazil move forward with the competency-based approach designed back in 2006. Competency-based management (gestão por competências) was introduced in 20066 to help plan, monitor and assess capacity-building activities. Its focus was on identifying the knowledge, skills and attitudes needed to perform civil service functions.7 While this has yet to formalise into a national competency framework, it has served as a driver for reorienting and strengthening training opportunities and individual development.

The gradual emergence of competency frameworks in different institutions across the Brazilian federal administration and beyond is a strong indicator that organisations are open to taking a more structured approach to leadership development. Competency models have become foundational in leadership training. Various institutions in the Brazilian federal public administration, including the former Ministry of Planning, ENAP, the Court of Accounts and the Brazilian Development Bank, have developed their own frameworks to anchor their leadership development programmes (see Chapter 2). All of these programmes were created with the recognition that existing opportunities for leadership development were insufficient.

In parallel, Brazil’s Staff Development Policy and Guidelines8 regulate professional development through annual training plans for public organisations. Until 20109 this policy was steered by a committee which included the Secretary of Management (SEGES), the Secretariat of Personnel Management (SEGEP) and ENAP. While this policy acknowledged the importance of professional development, it never lived up to initial expectations. The evolution of the political context since its approval led to regular changes in priorities and operational objectives, as well as to the difficult task of co-ordinating multiple decision makers with conflicting priorities (Camões and Meneses, 2016).

The current legal basis to train people for DAS and FCPE positions10 is the same decree that introduced competency-based training in the federal administration. This decree also gives ENAP the responsibility to co-ordinate and oversee the management of training programmes for civil servants by schools of government of the federal administration, municipalities and foundations.

ENAP: A core institution for developing innovation skills

ENAP has been critical to the development of a competency-based approach by focusing on skills development through Masters, leadership development, senior executive programmes as well as specialised and general skills training. ENAP has gradually assumed the role of an informal “hub” or adviser for many leadership programmes. Although ENAP does not have the authority or ability to create a singular leadership curriculum that organisations use to develop leaders, the school’s presence in the formation of many of the existing programmes at least promotes a general coherence in the competency models and convergence in ideas and theories.

ENAP has also gradually become a hub for innovation skills development in the last few years. As of 2016 ENAP became a scientific, technological and innovation institution (instituição científica, tecnológica e de inovação), responsible for research and service development relevant to improve the efficiency and the quality of public services. The 2019 decree11 reinforces ENAP’s role in this field by centralising in ENAP the elaboration and execution of staff development programmes related to public sector innovation for improving the efficiency and quality of the services provided to citizens.

The development of public sector innovation within public administration schools is also common in some OECD countries. In France, ENAP’s French homologue (École nationale d’administration) is one of the founding members of the Chaire Innovation Publique, one of the first cross-cutting attempts to transform the future of working in the public sector through innovation. In Spain, a 2018 amendment created a Department of Public Sector Innovation in the Institute of Public Administration (INAP), and INAP is gradually becoming a key player in the process of transforming the public administration. To support the emergence of a culture of skills for transformation and innovation, INAP is investing in projects to develop a competency-based approach across the administration (Box 4.3).

The Spanish Institute for Public Sector Innovation (INAP) is an autonomous body responsible for the training of civil servants at all levels. INAP introduced a Department of Public Sector Innovation in 2018 to support the institute’s mission to transform the Spanish public administration and better address the needs of citizens.

One of the key areas of concern for the new department is new skills for the civil service, linked to the work that the institute is carrying out on the Sustainable Development Goals Agenda, digitalisation, social change and new realities. In this framework, the department is working to improve innovation skills in four areas:

-

1. establishment of a common methodology for the detection of training needs

-

2. preparation of skills models for different professional profiles

-

3. promotion of an approval and certification model for qualifications valid for all administrations (national and regional)

-

4. development and application of evaluation methodologies acquired formally and informally.

The department’s work aims to contribute to INAP’s ambition to become increasingly democratic, inclusive, diverse, sustainable, representative and aligned with the society it serves. To serve this purpose, focus is given to improving its selection processes and attracting valuable and diverse (highly skilled) talent, learning values, competencies and skills of public servants, and reflection and research on the challenges facing the state and its public administrations within a framework of partnerships.

Source: INAP’s presentation in the 6th Annual Meeting of the OECD Global Network of Schools of Government, Helsinki, September 2018.

From bespoke to systemic: Moving away from classroom training to creating a learning culture for innovation in the senior civil service

To shift a learning culture from sporadic to systemic also requires a review of the proper drivers that would encourage and push current and future leaders to obtain these skills and competencies. From the supply side, there needs to be a multi-method approach that allows people to learn in different and new ways, both in specialised programmes and also every day on the job. However, to truly have a systemic approach to a learning culture, there must be a demand for the skills that public leaders need. The 2019 OECD Recommendation of the Council on Public Service Leadership and Capability highlights many of these elements (Box 4.4).

The OECD’s Recommendation of the Council on Public Service Leadership and Capability recognises the fundamental need to develop a learning culture in public sector institutions. Under the Recommendation’s second pillar on “investing in public service capability in order to develop an effective and trusted public service”, OECD countries emphasise the contribution learning makes to this, by:

Developing the necessary skills and competencies by creating a learning culture and environment in the public service, in particular through:

-

1. identifying employee development as a core management task of every public manager and encouraging the use of employees’ full skill sets

-

2. encouraging and incentivising employees to proactively engage in continuous self-development and learning, and providing them with quality opportunities to do so and

-

3. valuing different learning approaches and contexts, linked to the type of skill set and ambition or capacity of the learner.

Source: OECD, Recommendation of the Council on Public Service Leadership and Capability, OECD/LEGAL/0445

Developing a skill or competency can be a targeted and finite activity, and may be a first step towards developing a learning culture. However, a culture of continuous learning requires a consistent focus on creating environments where employees are encouraged and supported to learn and develop their skills and competencies – both existing and new. Most skills and competencies are not binary where one either “has” or “does not have” it. Instead, it is often evolutionary where it takes time, practice and experience to master. Traditionally skills and competencies have been taught in a controlled environment, such as a classroom or lab, and then participants are expected to start using these out in the real world. More recently, experiential training has become popular – learning through hands-on experience, by doing the work with appropriate guidance and support.

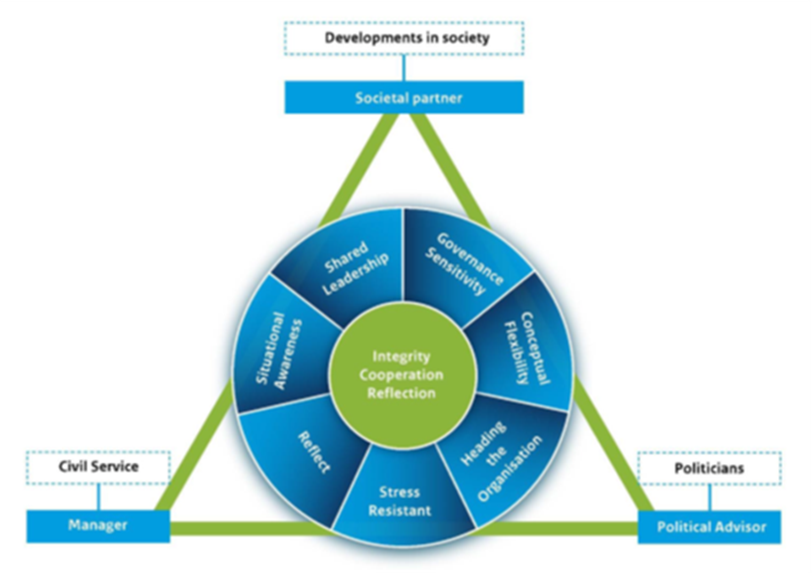

One of the challenges of experiential learning, particularly for leaders, is that it requires a high level of self-awareness and space for reflection. This goes against the traditional notion that leaders are the smartest and most experienced in the organisation. However, the idea that everybody is a novice and able to learn from experience is a fundamental tenet of innovation, since, by definition, participants are trying something new. This is aligned with the anti-hero approach to modern public leadership discussed in Chapter 3. The Dutch government has developed a vision for public sector leadership which focuses on three core competencies: integrity, collaboration and reflection (Box 4.5). Reflection recognises the need for leaders to take the time from their hectic daily schedules to reflect on their craft and learn from experience.

The Dutch vision of public sector leadership recognises that there is not one single ideal type of leader; rather there are qualities every public leader should show:

-

1. Integrity: The public leader works sincerely and consciously in the public interest, addresses the social issues and demonstrates this in his/her daily actions.

-

2. Co-operation: The public leader puts shared leadership into practice, is focused on the broader context and not exclusively his/her “own” domain, actively seeks collaboration and co-creation, and is able to understand various perspectives.

-

3. Reflection: The public leader has self-awareness and organises reflection in the field based on knowledge and practice, asks the right questions, and accordingly determines the course and position.

Source: Information provided to the OECD by the Office for the Senior Civil Service, Netherlands.

Competency models such as those discussed in Chapter 3 serve as a guide to help guide training programmes for leaders and potential leaders, but as the skills needed evolve and new skills emerge, competency models alone do not create a learning culture. Additionally, during a time of potential fiscal austerity, training dollars become scarce, which limits traditional training opportunities for leaders and employees. In the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis, most OECD countries reported that their training policies in central public administration were affected. While nineteen countries implemented measures to raise the efficiency of training, 16 reduced training budgets; and ten reduced the number of training days (OECD, 2016).

Because each person learns differently, there is no single solution to this issue. Instead, multiple approaches are required. There need to be solutions that incorporate classroom learning, experiential learning and peer learning. Additionally, employee development needs to be something that every people manager commits to. This means ensuring that managers are given the skills, competencies and tools to manage their teams in ways that integrate learning into their everyday work. This can be as simple as developing regular opportunities for their employees to learn from each others’ ongoing projects, and/or assigning tasks in ways that expand employees’ capabilities. In Ireland, a core pillar of the recent Civil Service People Strategy is to ensure that every manager is a people developer. In Finland, leaders meet once a month around various leadership topics. Leaders self-select which topic they want to address and it is relatively self-organised.

The third pillar of Ireland’s Civil Service People Strategy 2017-2020 is entitled “Build, Support and Value Managers as People Developers” and sets an outcome target of, “the civil service has great people managers enabling civil servants to perform to the highest levels and fulfil their potential.”

The actions laid out in this part of the people strategy commits the civil service to “foster a stronger culture of good people management by re-emphasising the people management role for all managers, so that they understand what is expected of them. Organisational HR units (OHRs) will support people managers by ensuring that they have access to effective tools, supports, professional HR advice and expertise, so that managers can further develop their capacity and confidence to deal with all people management issues. OHRs will be supported by a Central HR Advisory Service so that they can build the supports and services necessary to provide services to people managers. Managers at all levels will develop a stronger collaborative management culture by recognising and modelling good people management practices enabling the creation of a high performing work environment with the right conditions for dealing effectively with underperformance.”

Source: Civil Service HR Division (2017), “People Strategy for the Civil Service 2017-2020”, https://hr.per.gov.ie/wp-content/uploads/People-Strategy-for-the-Civil-Service-2017-2020.pdf.

Transforming executive innovation training

New forms of executive innovation training are emerging in Brazil and in many OECD countries. These trainings, often conducted by innovation labs in the civil service, are focused on helping leaders understand how to lead innovative projects and provide the support necessary for innovation to thrive. The Government Digital Services in the United Kingdom has developed an Agile for Leadership class, the Canadian government is looking at something similar regarding digital competencies, and Chile and Colombia actively engage senior leaders when their teams are engaged in innovation challenges through the country’s innovation labs. All of these initiatives allow leadership to gain first-hand experience in how innovation happens to better understand how they can support it.

Canada’s Digital Academy was launched in 2018 with the purpose of “placing the public service at the forefront of the digital age and to making its services more secure, faster and easier for all users”. The academy is hosted at the Canada School of Public Service, and its curriculum will support all levels of public servants, including senior civil servants (Box 4.7).

The Digital Executive Leadership Program, launched by the Canadian Institute on Governance, is part of the government of Canada’s Digital Academy initiative. The five-day course aims to provide public sector executives at all levels of government (federal, provincial, municipal) with the digital literacy and leadership skills they need to be effective decision makers in the rapidly changing policy and service delivery landscape.

The focus for the programme is centered on three core areas and how they are changing the landscape for governance, service delivery and policy development in the public sector: design thinking, digital technologies and data. The course provides participants with a basic grounding in key concepts from each of these three disciplines, and a practical understanding of how they can be applied to the business of government. In addition, the programme also provides participants with an understanding of the big strategic drivers of the digital era, and considerations for building and managing modern, digitally savvy teams in the public sector.

Source: Institute on Governance (2018), Digital Executive Leadership Program, in https://iog.ca/leadership-learning/digital/ (accessed 26 September 2019).

In Estonia, the Top Civil Service Excellence Centre is responsible for the development of Estonia’s senior civil servants. It has developed a training programme that focuses on experiential learning, applying modern problem-solving techniques, and even brain science to help leaders better understand themselves, build innovation skills and conduct activities on site where “seeing is believing”. This programme has gained such popularity that the governments of Finland, the Netherlands and the United Kingdom requested their leaders participate.

ENAP’s Training Programme for Senior Executives (Programa de Capacitação para Altos Executivos) has become a reference in the field of executive leadership training in Brazil’s public sector, and includes an important component on innovation. Created as a pilot project at the end of 2015, this programme was one of the most recent initiatives to map and develop the skills and competencies required to professionalise politically appointed public leaders. ENAP’s training is not mandatory, so the strategy is about creating a diversified offer in terms of themes and formats to nudge leaders into self-selecting for training.

By targeting training at appointed SCS positions, ENAP is also building bridges between the political and the administrative spheres. Especially within Brazil’s system where the political-administrative interface is blurred, transforming the public sector in a sustainable way requires preparing leadership to face technical and political challenges, regardless of whether they are appointed from the civil service or from other sectors. To address this, ENAP’s approach is designed around real-life leadership challenges. This programme also offers different learning modalities to build these bridges, ranging from international training cycles, conferences and individual coaching to more informal events such as thematic dinners for senior executives and gatherings of the programme’s alumni.

The complexity of leadership and its challenges also means that developing leaders is more than a repetitive exercise; it is an iterative process. ENAP’s different training programmes are dynamic and grounded in partnerships with prestigious training institutions worldwide, namely the John F. Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University and the French School of Public Administration. One of the most recent editions (August 2018) focused on “Leadership and Innovation in a Context of Change”. During the course, participants worked on an ongoing challenge while developing skills and competencies related to adaptive leadership, technology management or innovation in public policies.

ENAP’s iterative approach to the Training Programme for Senior Executives involved testing different practice-oriented methodologies leading to a wide variety of complementary learning paths (Box 4.8). The programme’s success following ENAP’s restructuring in 2016 created the opportunity to strengthen ENAP’s mission to “plan, direct, co ordinate, guide and evaluate the training offer for senior executives”. ENAP’s Leadership Development Programme, a project-oriented course focused on developing business acumen in particular areas and innovative skills, combines online preparation and discussion with classroom training, and is targeted at managerial positions across the federal government.

Improving the skills of public servants

Created in 1986, the National School of Public Administration (ENAP) is a public foundation whose purpose is to promote, design and execute human resources training programmes for the federal administration.

It has also collaborated with outside organisations to bring advanced thinking around public sector leadership. For instance, ENAP partnered with Harvard University for a leadership programme with DAS* 5 and 6, as well as people in positions of “special nature”, such as ministers and vice -ministers. Bringing in outside partners helps to ensure content is current, timely and allows for multiple perspectives from inside and outside the current system.

ENAP was one of the first organisations in Brazil to create innovation training and competency models for training programmes. Starting in 1996, ENAP and the former Ministry of Planning, Development and Management also created the Innovation Award to celebrate innovators and their projects to improve services to the population.

In addition, the OECD observed ENAP’s role in the evolution and promotion of public sector innovation in Brazil. ENAP is serving as an informal “hub” for innovation programmes and training, working with various public sector organisations and civil society to promote, enhance and spread best practices of innovation training.

Leadership training

ENAP’s mandate on leadership training evolved with Decree No. 8.902/2016, which stressed that one of ENAP’s missions was to support and promote training programmes for people in leadership positions (DAS and “commissioned functions” [FCPE]). As part of its new mission, ENAP strengthened its partnerships with international leadership training institutions to develop and deliver short-term courses in areas related to innovative leadership in public organisations (Programa de Capacitação para Altos Executivos). Recent training offer for senior executives includes experiential and problem focused training programmes, in-company consultancy, and informal events for senior managers.

Note : * Senior Direction and Counselling Group.

Source: https://www.enap.gov.br.

There are also cases across the federal administration where civil servants were encouraged to attend leadership training programmes. A programme in the former Ministry of Planning established that civil servants could take training leave for priority fields for the ministry such as leadership, economics or public administration. Civil servants applied to the programme through a selection process, then were eligible to attend long-term courses, including Master and PhD degrees. The increase in the qualification of the ministry’s staff led in practice to an increase in the qualification of the people later appointed for leadership positions.

Investing in leadership development for innovation raises a challenge about ensuring the quality and impact of the training provided. In this context, it could be relevant to develop some sort of certification mechanism, such as, for example, France’s “School of Management and Human Resources” label, which consists in the certification, by a committee of independent experts, of training programmes which are either interministerial or relevant for more than one ministry. Despite the benefits of certification, attention should be paid to avoid creating overburdening processes.

To strengthen coherence around public sector innovation, France’s Interministerial Directorate for Public Transformation (Direction Interministérielle pour la Transformation Publique), under the Prime Minister’s Office, has created a “Public Transformation Campus”. The campus provides team training on project management, user centricity, digital, innovative approaches and managerial transformation. It also brought together respected actors in the field of innovation training in France. This includes, for example, the National School of Administration (École Nationale d’Administration), the Institute for Public Management and Economic Development (Institut de la Gestion Publique et du Développement Économique), or the National Centre for Territorial Civil Service (Centre National de la Fonction Publique Territoriale). The campus aims to develop synergies among existing training programmes and promotes the training delivered by its partners.

Reinventing skills development through innovation labs

ENAP’s innovation lab, GNova, uses design-thinking methodologies to help public institutions address their challenges. GNova’s approach is an interesting way to link experiential learning with classroom training by supporting bottom-up innovation processes, also tested in other countries. Teams from GNova partner with the civil servants from the client organisation to co-create and experiment solutions and prototypes, for example to improve the delivery of services to citizens.

In Chile, the Laboratorio de Gobierno developed a programme called Experimenta to develop innovation skills in a selected group of public employees through a learning-by-doing approach. This “learning-by-doing” approach whereby innovation labs partner with other public sector organisations to collaborate, co-create and design has become a popular and effective way to build innovation capacity and experience in organisations.

Investing in collaborative partnerships beyond the public sector

ENAP and other public sector organisations are not the only actors interested in improving the competencies of public leaders to steer public sector innovation in Brazil. Civil society is playing a key role in advancing innovation skills in the public sector. For example, the “Support Programme for the Development of Public Leadership” has emerged to help build public leaders’ capacity, including elected officials, engaged in changing Brazil based on the principles of integrity, democracy and sustainability. The programme is the result of a partnership between the “Political Action Network for Sustainability (Rede de Ação Política pela Sustentabilidade) and the Lemann Foundation. The content is developed by the two partner institutions and includes training on themes such as health, public safety and climate change. The second edition (2018) was open to 20 leaders throughout Brazil. Other examples include the Dom Cabral Foundation, which is working with ENAP, the Ministry of Economy (previously Ministry of Planning) and others on leadership training and development based on various leadership competency models; and the Getúlio Vargas Foundation has also created leadership programmes aimed at the public sector. These organisations are playing an important role to help develop a more mature understanding of the competencies needed for public sector leaders in Brazil and to bridge the gap between the public sector and civil society, the private sector, and academia.

Collaborative partnerships between the public sector and external stakeholders can help advance public leadership for innovation. Such partnerships can create access to a wider body of knowledge, perspective and technology, and help generate a better understanding of problems, policy issues, and define and test potential solutions (see, for example, OECD 2017b). In the field of leadership skills and competencies for innovation, the launch of the Public Innovation Chair (Chaire Innovation Publique, CIP) in France provides a good example of this type of collaborative partnerships. The CIP’s approach focuses on bringing in different stakeholders to prepare current and future senior civil servants to innovate through design, digital technology and behavioural insights.

The Public Innovation Chair (CIP) aims to be a new space to co-create the 21st century administration through a multidisciplinary and iterative approach to policy making and public service delivery. The CIP looks at how public sector innovation (often based on concepts from design, behavioural economics or digital transformation) challenges the traditional ways of working and affects the way people and resources are managed, and how decisions are taken. This means looking at the impact of digital transformation (including digital governance or use of data); user-centered design (starting from the experience of users, civil servants and citizens); and new ways of working (including labs, open innovation, agile innovation, start-up mode).

The Public Innovation Chair works to mainstream innovation, including among public sector leaders. By helping senior civil servants understand new ways of working in government, they contribute to government innovation and are better placed to incentivise innovation in the organisations they lead. In this context, the CIP aims to:

-

1. experiment by supporting innovative field projects

-

2. advance research and analysis to understand how public administration is changing at national and territorial level

-

3. monitor progress and share knowledge on innovation

-

4. learn innovation through initial or continuous training.

The CIP is not a traditional academic chair and none of its core partner institutions have a permanent body of professors. While this characteristic means that the CIP’s leadership may not be clear in the public sector landscape, it also creates space for more flexibility and scaling up.

Source: ENA/ENSCI (2017), Presentation of the Public Innovation Chair.

Using networks to support innovators

Interest in public sector innovation has been growing throughout the Brazilian federal administration. The public innovation awards were established in 1996 to reward new ways of working in the public sector. In 2016, the then Ministry of Planning and ENAP organised the first Innovation Week and ENAP hosted the first innovation lab (GNova). In parallel, public sector innovation became a growing field of research among Brazilian academics and practitioners. Some of the first reflections and analysis of the Brazilian experience helped map trends, success stories, opportunities and barriers for innovation (see, for example, ENAP/IPEA [2017]).

Innovation remained a relatively isolated activity in the federal administration landscape. While awards and events celebrated innovation across the public sector, initiatives and teams remain the exceptional way of working in the administration. The lack of a clear mandate to innovate possibly reinforced the perception of risk associated with innovation; most innovations are very context-specific, which made them hard to scale up or to replicate in different contexts (ENAP/IPEA, 2017).

Despite little systematisation of innovation across the administration, the success stories helped support an emerging innovation-oriented organisational culture. Awards and events give visibility to initiatives and help people learn from each other’s experience (OECD, 2015), which can help motivate civil servants. Awards are widely used across OECD countries to recognise successful public sector innovation in different areas of the civil service. In the United States, the Presidential Rank Awards Programme recognises a select group of career members of the Senior Executive Service for exceptional performance. In Chile, the Funciona! recognises teams of civil servants who have created innovative initiatives in their institutions, with an effect on internal efficiency and/or in the quality of services provided to citizens (OECD, 2017a).

Besides giving visibility to innovations, events and awards can also help to build a community of practice around innovation. Innovators are change agents and, as such, they often struggle to get support within their own organisations. Facilitating communication between innovators, who often face similar challenges, can help them support each other, strengthen their motivation and capacity for action, and even help scale up innovations (OECD, 2017). This type of informal, self-driven network is a common form of innovators networks in OECD countries. In Finland, for example, the Change Makers network is a loosely organised and self-managed team of experts from different ministries, with different backgrounds, education and expertise. What is shared among the participants is the need and the will to build up a working culture based on a “whole government” mindset and “crossing the silos” ways of working.

Institutional support to networks of innovators is also an important element to strengthen the visibility and impact of public sector innovation. Formalising innovation networks can help give consistency to different networks, creating a coherent vision of innovation, and consolidating the impact of the network on the public innovation landscape. The gradual launch since 2015 of InovaGov, the Federal Network of Innovation in the Public Sector (Rede Federal de Inovação no Setor Público) responds to that need to formalise networks of innovators. In the Brazilian federal administration context, formalising a network for innovation may also give some legitimacy to time spent on innovation (ENAP/IPEA, 2017). Developed by the Department of Public Management Modernization (Departamento de Modernização em Gestão Pública, Inova) of the former Ministry of Planning, the InovaGov was supported by strong institutional actors such as the Court of Accounts (Tribunal de Contas da União) and the Council of Federal Justice (Conselho de Justiça Federal). InovaGov has grown to become a space where different sectors interact. It creates value by opening the discussions outside the public sector to include businesses, academia and non-governmental organisations.

Networks of innovators are also common across most OECD countries. Similarly to InovaGov, the most common purpose of innovators networks in OECD countries is to help members share their experience, like Portugal’s Common Knowledge Network RCC, which is a collaborative platform to promote the sharing of practices and information about modernisation, innovation and simplification of public administration.

The development of InovaGov raises questions about the role of Inova and of the Ministry of Economy in building the supply of skills for innovation. In many OECD countries, innovators networks build the capacities of members through training provide support to develop specific projects or guidance to public institutions (OECD, 2017). In Chile, the Network of Public Innovators, created in 2015, aims at being a movement of diverse actors motivated by the search for tools, experiences and approaches that facilitate the development of innovations to improve public services for their users. The network employs a threefold strategy that includes collective learning, making public innovation visible and connecting motivations to innovate (OECD, 2017).

While capacity building is not at the core of InovaGov, the network’s missions naturally include some capacity building about innovation tools and practices. Co-ordinating with other training providers, in particular ENAP, is fundamental to develop a shared vision and approach to innovation for Brazil’s federal administration. Having a coherent approach to skills and competencies development can help identify common challenges and needs, in a context of heterogeneity of skills and competencies needs and a myriad of public sector careers that hamper career mobility. As described above, coherence is particularly important when it comes to leaders’ skills and competencies to support innovation.

ENAP is also exploring the potential of formal and informal networks to improve the impact of its leadership programmes. Informal thematic discussions and dinners such as those organised by ENAP, between senior civil servants from different administrations and experts, have the potential to help leaders exchange experiences and discuss challenges, which often help identify shared concerns or commonalities. OECD research indicates that while most OECD countries provide institutional support for innovators networks, informal and self-driven public sector innovation networks are even more common across the OECD (2016a).

Another of ENAP’s major initiative is the Alumni Network of the Senior Executive Training. Regular events for alumni allow them to strengthen personal and professional networks and build additional value from continuous training.

Finally, formalising networks should not come at the expense of informal or non-governmental initiatives. Individual motivation is a powerful driver of innovation and appears to have more influence on the outcome of innovation than formal processes (see, for example, ENAP/IPEA [2017]). In fact, in the past years, Brazil’s civil society has been increasingly involved in discussions to improve innovation and, more broadly, the quality of the public sector. Various initiatives have emerged from the civil society involving the municipal, state and federal level.

The civil society organisation Vetor Brasil has been helping municipalities and states to recruit public leaders and trainees (see Chapter 5). Since its creation in 2015, the recruitment programmes developed by Vetor have enabled the creation of a network of talented and engaged professionals that support excellence in the public service. Likewise, the civil society organisation Brava works to support innovation and digitalisation across government in order to improve public management. It brings together stakeholders and innovators to support a culture of better public management. Brava’s initiatives include working with schools to help students understand policy making and stimulate critical thinking. Brava has also set up an open online platform to inform citizens about public challenges and help identify innovative solutions.

Vetor Brasil is a non-profit civil society organisation working to improve the governance of the public sector. Since 2015, Vetor Brasil has collaborated with public institutions to improve human resource management skills in the government, including to develop new strategies to attract, select and develop public sector professionals.

Vetor’s programme “Leaders of Public Management” (Programa Líderes de Gestão Pública) is based on partnerships, mainly with local and state level administrations. Vetor’s approach includes a skills diagnosis and pre-selection of qualified candidates. After the hiring decision (by the public authority), the selected candidate becomes a member of Vetor’s professional network. The network aims to empower and support these leaders throughout their careers in the public sector.

Source: Interviews and Vetor Brasil, in https://vetorbrasil.org/

Recommendations and roadmap

Ensuring there is a proper supply of the skills and competencies for public sector leaders requires an ongoing, systemic approach that needs constant and consistent oversight, nurturing, and long-term planning and flexibility. There will always be a need for adaptation and flexibility of leadership styles and competencies due to the breadth of activities and responsibilities within the public sector. At the same time, a bespoke training model whereby each ministry and institution is individually responsible for ensuring a supply of current and future leaders will only serve to reinforce the fragmentation of the current model in Brazil.

These recommendations therefore focus on activities that shift the learning culture from sporadic to systemic. While every ministry will have a role in the shift, the OECD recognises the importance of ENAP and the Secretariat of Planning and Management in the Ministry of Economy as the main stakeholders to lead the reforms, reinforce and oversee the continuous learning culture in the Brazilian public sector.

For supply-related recommendations, there are two clear areas of focus: create a trusted ecosystem with a unified view of leadership and ensure the training that is offered actually supports and enables this unified view to become a reality. Additionally, the need for constant internal and external communications and feedback is critical for these initiatives. As stated in the OECD’s upcoming public sector innovation review of Brazil, the need for clarity and clear signals as to what is expected is critical to many innovative initiatives (OECD, 2019 forthcoming).

Strong learning cultures are dynamic, flexible, constantly experimenting to explore what works, and comprise a variety of diverse activities. Because of this complexity, the recommendations are separated into:

Immediate: Activities that can begin immediately and are logical next steps based on the understanding of the current system.

Second-stage: Activities that represent the logical follow-up to the short-term recommendations. These activities will require some reassessment based on feedback and outcomes of the implementation of the short-term recommendations.

Longer term: Activities that require careful planning, greater investment, more time and a strong systemic foundation. These recommendations will need additional evaluation as changes in complex and dynamic systems are difficult to predict over a long time frame.

Immediate recommendations

As discussed earlier in the chapter, ENAP has served as both an informal hub for leadership programmes and an early adopter in recognising innovative competencies, creating new curriculum and experimenting with new training models. Because of its unique position and its mission, ENAP is already well positioned to increase its role in promoting and establishing a stronger learning culture in Brazil’s public service today and in the future.

As neither ENAP nor the Secretariat of Planning and Management are likely to be given legal purview over all leadership professional development, both could continue to play a role in the broader system. This means continuing to encourage training providers to work with networks within and outside the civil service. These networks have relevant knowledge and experience which could benefit training programmes, strengthen the link between learning and implementation, and help build stronger bonds between leaders and future leaders in various areas.

Additionally, the Secretariat of Planning and Management could also have the responsibility to make training information easily available for senior civil servants, civil servants and people working in the federal administration. This could be inspired by what already exists in the “Portal do Servidor,” and could consist of an online tool compiling all the information available on training available by topic, tool, date, target group, type of training, price and any other information that might be useful.

Lastly, GNova and ENAP could further develop experiential training methods that connect implementation of innovative projects with capacity building, including at the leadership level. GNova’s training approach for civil servants is a relatively recent one, and will need further iteration. Once the programme is relatively stable, the focus could shift to capacity, scale and replication for an even greater impact.

Second-stage recommendations

ENAP could use its trusted network and expertise to create a unified competency model that can be the foundation of leadership training across the Brazilian ecosystem. This competency model does not need to be built from scratch – ENAP and other organisations should review their own competency models as well as the OECD model from Chapter 3 to firmly establish a leadership competency model that properly emphasises the competencies and skills that Brazil requires of its leaders, especially with innovation skills and mindsets. ENAP should not pursue this alone; it should collaborate with outside organisations, civil society and ministries to co-create an inclusive, shared solution.

The competency framework can also be used to assess the current skills and talents to establish a baseline within the public administration, specific organisations or careers. The Secretariat of Planning and Management could partner with ENAP to pilot a competency assessment methodology. This pilot could be across one ministry, or within a single career, with a view to expanding it in a phased approach. The assessment could use information that is already available, such as that from the Talent Bank (see Box 4.14), which could also align with the competency model to standardise its approach to competency identification and assessment.

Lastly, ENAP could align training with any specific gaps identified based on current available data. With the Talent Bank and the OECD survey, there are already some data to determine if any adjustments need to be made in the training curriculum to ensure that ENAP is responsive to the current strengths and weaknesses within the public sector.

Longer term recommendations

Major changes in a large and complex system like the public sector will produce unexpected outcomes. Trying to evolve and improve the learning system in Brazil’s public sector requires both short-term agility and long-term perspective. Because of this dynamic, the recommendations in this section may continue to evolve and change.

In the longer term it could be useful to more clearly define the roles of the various actors in the system. While there does not need to be a single owner of the leadership development system, the lack of defined roles and responsibilities can cause adoption to slow or stall. The role of ENAP and the Secretariat of Planning and Management are both central, but so is the role of the Staff Development Policy Committee and how it engages with the responsibility to recruit, develop and use innovation-related skills. The role of ministries, institutions, careers and outside actors could also be defined. As with any living system, these roles will continue to shift and evolve, but creating an understanding of the roles and responsibilities in the system to track their evolution will be important so as to better integrate activities, reduce overlap and duplication, and address gaps and emerging needs. This may require the establishment of a training council that can serve to co-ordinate the system and update roles and responsibilities as they evolve.

As with any new model for leadership competencies, training providers could conduct a self-assessment to align training offerings with the new model to ensure the outcomes of the training will produce the newly defined skills and competencies. Based on ENAP’s extensive training, it is likely that much of the training is already fairly aligned, but tweaks may need to be made. Additional adjustment could be considered based on the findings from the public sector competency assessments. For instance, ENAP may invest too heavily, in terms of frequency of classes and curriculum development, in one competency while there are large gaps in a different competency which is going underserved. Again, the Talent Bank – which may need to be tweaked to align with the model – and the OECD survey can serve as a starting point for this analysis.

Regarding roles, ENAP could continue to develop partnerships with other training providers. No organisation has the capacity to train the entire public service, and ENAP should continue to look for trusted partners at the local, national and international level to improve innovative leadership. This also includes civil society organisations and networks both inside and outside the civil service.

Communication and feedback

As with any large-scale initiative that impacts the whole of government, communication with clear signals is critical to success. Communication is needed throughout the process and must be done in a way that can elicit feedback. Communication can serve purposes such as:

-

sending a clear signal of what is important

-

sharing a consistent vision across the ecosystem

-

influencing and impacting behaviours

-

allowing for feedback more easily.

For instance, the Secretariat of Planning and Management should work with ENAP to increase the understanding of innovation and innovative leadership through a constant and diverse communication plan. Part of this plan could link to specific trainings, but it should also specifically focus on winning the hearts and minds of the public sector with an aspirational vision for current and future leaders. Because of ENAP’s role of creating competency frameworks and curriculum as well as its informal role of supporting other public sector leadership programmes within various ministries and institutions, it is in a unique position to directly influence other institutions and ministries in terms of adopting the framework.

References

Camões, M. and I. Balué (2015), “Análise de processos seletivos para cargos comissionados no âmbito da administração pública federal”, VIII Congresso CONSAD de Administração Pública.

Camões, M. and P. Meneses (2016), Gestão de Pessoas no Governo Federal: Análise da Implementação da Política Nacional de Desenvolvimento de Pessoal, Cadernos ENAP, No. 45, National School of Public Administration, Brasília.

Civil Service HR Division (2017), “People Strategy for the Civil Service 2017-2020”, https://hr.per.gov.ie/wp-content/uploads/People-Strategy-for-the-Civil-Service-2017-2020.pdf.

ENAP (2018), Informe de Pessoal: Março 2018, National School of Public Administration, Brasilia.

ENAP/IPEA (2017), Inovação no Setor Público: Teoria, Tendências e Casos no Brasil, Pedro Cavalcante et al. (orgs.), National School of Public Administration, Brasilia.

Institute on Governance (2018), Digital Executive Leadership Program, https://iog.ca/leadership-learning/executive-leadership/executive-leadership-program-digital (accessed 1 March 2019).

OECD (2018a), Embracing Innovation in Government: Global Trends 2018, OECD, Paris, https://www.oecd.org/gov/innovative-government/embracing-innovation-in-government-2018.pdf.

OECD (2018), “Survey on Innovation Skills: Organisational Readiness Assessment” (Habilidades de Inovação: Avaliação de Prontidão Organizacional), unpublished.

OECD (2017a), Innovation Skills in the Public Sector: Building Capabilities in Chile, OECD Public Governance Reviews, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264273283-en.

OECD (2017b), Skills for a High Performing Civil Service, OECD Public Governance Reviews, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264280724-en.

OECD (2016a), Engaging Public Employees for a High-Performing Civil Service, OECD Public Governance Reviews, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264267190-en.

OECD (2016b), “Strategic Human Resources Management Survey”, OECD, Paris.

OECD (2015), The Innovation Imperative in the Public Sector: Setting an Agenda for Action, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264236561-en.

Notes

← 1. Decree No. 9.727

← 2. Degree, post-graduate, Master or PhD

← 3. Bachelor, Master or Doctoral degree

← 4. Data from 2015, collected through the 2016 OECD survey on the composition of the workforce.

← 5. Iteration, data literacy, user centricity, curiosity, storytelling or insurgency

← 6. Decree No. 208 of 25 July 2006, Ministry of Planning

← 7. Free translation: “ferramenta gerencial que permite planejar, monitorar e avaliar ações de capacitação a partir da identificação dos conhecimentos, das habilidades e das atitudes necessárias ao desempenho das funções dos servidores”.

← 8. Decree No. 5.707-2006 on the policies and guidelines to staff development in the federal direct, municipal and foundational administration, regulating Law 8.112 of 11 December 1990), available at: www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_Ato2004-2006/2006/Decreto/D5707.htm (accessed 22 October 2018)

← 9. In 2010, the Secretary of Management became part of SEGEP, which also included the Secretariat of Human Resources. A 2016 decree recreated the secretariats, but the Skills Development Management Committee has not been operational since.

← 10. Article 10 of Decree No. 9.727-2019

← 11. Decree No. 9.727-2019