Chapter 3. Evolving E-Commerce Business Models

E-commerce facilitates trade across borders, increases convenience for consumers, and enables firms to reach new markets. Despite its short history, the e-commerce landscape has rapidly evolved through the development of new business models, which often integrate new and emerging digital technologies as well as new online payment mechanisms. This chapter analyses evolving e-commerce business models, focusing in particular on business-to-consumer (B2C) e-commerce, and includes examples from existing businesses to highlight firm-level innovations. It concludes by identifying key areas for policy action.

E-commerce has emerged as an economic and social phenomenon over the last 25 years, facilitating trade across borders, increasing convenience for consumers, and enabling firms to reach new markets. Over that short history, the e-commerce landscape has rapidly evolved through the development of new business models, which often integrate new and emerging digital technologies as well as new online payment mechanisms. This change has occurred in tandem with the wider social and economic implications of digital transformation.

Many e-commerce business models use online platforms, facilitating purchases between often unknown and dispersed buyers and sellers. Another emerging trend is the growth of subscription e-commerce business models, whereby users access goods and services in a continuous, recurring stream. Firms are also developing online-offline e-commerce business models that integrate digital ordering mechanisms alongside physical infrastructures, including within brick-and-mortar stores. This chapter discusses these business models as well as the digital technologies and payment mechanisms that enable them.

A business model is a “term of art” without precise definition that has emerged from the business and economics literature (Ovans, 2015[1]). Broadly, the term describes the strategies and mechanisms firms use to succeed in competitive marketplaces. The Oslo Manual, a statistical manual for the measurement of innovation, defines a business model as “all core business processes … as well as the main products that a firm sells, currently or in the future, to achieve its strategic goals and objectives” (OECD/Eurostat, 2018[2]).

A variation on this definition includes “the rationale of how an organization creates, delivers and captures value” (Osterwalder and Pigneur, 2010[3]). Notably, this lens of value creation has been used across the OECD, including in analyses of taxation and environmental policy (OECD, 2018[4]; Hilton et al., 2019[5]).

In this chapter, “business models” refer to commonly observable business processes, purposes, strategies and means of generating revenue through e-commerce, although the precise formulation of these features differ. The chapter also highlights the role of new and emerging digital technologies and online payment mechanisms in these business models.

New business models push out the e-commerce frontier in two ways (see Chapter 2). First, new business models can enable more transactions to move online in a given market or for a given set of participants, an effect known as the intensive margin of e-commerce. Second, new business models can enable whole new markets to emerge for goods and services that previously could not have been bought or sold online, or allow new participants to enter the market. This effect is referred to as the extensive margin of e-commerce.

Digital technologies enable e-commerce innovations and often serve as the backbone of business model developments. Some of these technologies, like smart assistants enabled by artificial intelligence (AI), constitute new channels for selling or purchasing products over electronic networks. Other emerging technologies, like big data analysis, foster the growth of new data-driven business models for e-commerce and can support transactions moving online.

Similarly, online payment innovations can help to unlock e-commerce potential by promoting trusted online transactions between unknown parties. Such innovations make e-commerce more convenient and can facilitate trade online along the intensive margin. Similarly, innovations that enable new groups to participate in e-commerce can facilitate more trade online along the extensive margin. This chapter considers evolving e-commerce business models, focusing in particular on the business-to-consumer (B2C) space, and uses examples from existing businesses to highlight firm-level innovations.

Data are both an input and an output of e-commerce transactions. Online transactions provide some actors with the ability to collect a range of detailed data, including:

-

Individual data (e.g. name, gender, age, location, place of residence),

-

Customer history (including, in some cases, the ability to track transactions over time and across multiple vendors),

-

In-store movements (in the case of some of the online-offline interactions) and other spatial information, and

-

Browsing history, Internet Protocol (IP) address, and data from connected devices (discussed further below).

As e-commerce is undertaken through digital means, such data can be more easily captured and utilised than they would have been for an offline transaction.

Data generated and gathered in the course of an e-commerce transaction are often particularly lucrative because they can help target product offerings, improve matching and create a better consumer experience. This data can also drive firm-level strategies to increase and extend user participation. As e-commerce expands, these flows are increasingly large and rich, yielding combinatorial insights and innovations (OECD, 2015[6]) and creating new sources of value (OECD, 2018[4]). The private use of data is sometimes controversial and is the focus of past and future work across the OECD (OECD, 2017[7]; OECD, forthcoming[8]).

Online platform e-commerce business models

An analysis of e-commerce would be incomplete without a discussion of online platforms, which act as both retailers and providers of digital marketplaces that bring buyers and sellers together online. Online platforms have become significant actors in the e-commerce landscape, facilitating a range of interactions between disparate actors. In the context of e-commerce, online platforms typically bring together buyers and sellers for the sale/purchase of either digital or physical products, a phenomenon known as a multi-sided market. Ongoing OECD work analyses online platforms and the resulting multi-sided markets that facilitate interactions between multiple groups or users, or “sides” (OECD, 2019[9]).

Increased scale and scope of goods and services

As multi-sided markets, online platforms benefit from both direct and indirect network effects, whereby economies of scale benefit users on both sides of the market. In the context of e-commerce, these sides can be understood as buyers and sellers. Typically, buyers gain utility from the presence of more sellers, assuming there is an expansion in the scope and/or variety of products for sale. Similarly, sellers are attracted to buyers to whom they can sell their products. As digital services, platforms are characterised by relatively higher fixed costs and comparatively lower marginal costs, meaning that the additional cost of hosting another buyer or seller can be close to zero.

In the context of e-commerce, online platforms act as intermediaries between buyers and sellers to facilitate the exchange of goods and services over the Internet. The large number of actors in a digital marketplace allows a potentially infinite variety of goods and services available for sale, in contrast to the more limited scope of products available in physical stores. For example, the average physical “super centre” store of the American retail chain Walmart typically holds approximately 120 000 items for sale while Walmart’s online store offers 35 million items for sale (Bloomberg, 2017[10]). As additional products can be added to online platforms at very low marginal cost, the scope and variety of previously unprofitable products increases, pushing out the extensive margin of e-commerce (Ellison and Ellison, 2018[11]).

The sheer scope of the goods and services that can be made available on online platforms can also enable the provision of so-called “long-tail” goods and services (Anderson, 2004[13]), namely very niche products with small markets where it might be otherwise unprofitable for offline sellers to operate. Further academic work identifies the consumer surplus resulting from increased scope and variety of product offerings from online platforms (Brynjolfsson, Hu and Smith, 2003[12]).

The sheer abundance of products available for purchase through some online platforms creates significant back-end logistical, distributional and supply-chain challenges for online retailers. Digital technologies can transform back-end operations to increase efficiency and enable efficient delivery, despite increasing volumes and rates of processing and production. Machine learning algorithms that improve with use can also optimise autonomous machines and robotics to improve the warehousing, fulfilment and logistics processes.

Online retailers have a range of applications for machine learning, including optimising back-end scheduling and optimal resource allocation, predicting product demand, classifying products and identifying keywords, and developing ideal inbound and outbound logistics. Machine learning can also help in the parcel sorting process. For example, the Chinese retailer JD.com has incorporated robotics into logistics centres and warehouses to improve parcel sorting, packaging and distribution. The company unveiled a fully automated sorting centre in 2018, which features the completely automated processing of 16 000 packages per hour with an accuracy rate of almost 100% (JD.com, 2018[14]).

Connected devices are also extensively used throughout the inventory, logistics and fulfilment systems of e-commerce firms. For example, radio frequency identification (RFID) is a technology that enables the transmission of information over radio waves to Internet-connected devices, while a variety of sensors can be embedded in products to help to track items for transit. These can help optimise the supply chain process, predict shipping times and provide real-time monitoring of levels of stock. Nonetheless, RFID technologies have yet to be widely adopted by enterprises, suggesting unrealised potential (OECD, 2017[18]).

In other cases, online platforms have created new markets for goods and services that were previously not traded online, again increasing the extensive margin of e-commerce. For example, new business models like the American company Uber and the Chinese company Didi Chuxing enable online ride-sharing services, a market that did not exist prior to 2011. Similarly, home-sharing platforms like Airbnb enable access to accommodation in a novel sharing arrangement that would otherwise not take place, particularly on a global scale, without the existence of an online platform.

Matching buyers and sellers

As online platforms scale, they must provide some form of matching mechanism to enable buyers and sellers to find each other in a way that is satisfactory to both parties. Reducing friction, as well as transaction and search costs for both buyers and sellers, is essential to improving utility on both sides, and thereby increasing the chance of a successful online sale/purchase. Notably, these matches can take place between both local and geographically dispersed actors, and for the sale of both physical and digital goods and services.

Where a firm’s business model is based on user engagement (revenue from advertising) or on successful sales (a commission for intermediating services), the firm has incentives to develop mechanisms to ensure successful matches. Unsuccessful matches also cause actors on both sides to leave the marketplace, thinning out the market (Fradkin, 2017[19]; Horton, 2014[20]).

The type of matching mechanism differs across online platforms, and typically relates to the nature of the good or service on offer and the ability of the buyer to form or express a preference for a good or service. For homogenous, non-differentiable services where buyers have few preferences (or difficulties in assessing and expressing preferences), some online platforms have had success with centralised matching.

Uber, for example, algorithmically offers rides to drivers based on location and the buyer’s preferences (e.g. a private limousine or a ride shared with others). As noted by Einav et al. (2016[24]), this choice rests on the on-demand nature of Uber’s services which prioritises safe transportation with few transaction costs, low prices and short wait times. Customers indicate their preferences and their destination, and an algorithm matches the customer with a driver. While customers are not given a choice about specific drivers or car model, they have the option to reject their match. Other inputs to the matching algorithm include passenger and driver location, as well as supply (number of drivers) and demand (number of passengers), which influences the price.

In contrast, search and filter mechanisms may be more effective in decentralised marketplaces with more heterogeneous goods and services for sale for which customers may have a range of preferences (Fradkin, 2017[19]). For example, those looking for an apartment to rent on Airbnb will typically have different preferences for location, room characteristics and price in a given area.

To match buyers and sellers, or indeed consumers and content, e-commerce firms can make use of data gleaned from their customers to algorithmically optimise and personalise matching and product recommendations. These data could include browsing patterns, the length and nature of user engagement with particular features, responsiveness to design or format changes, or the behaviour of other similar users.

For example, Amazon uses AI, in the form of neural networks (Amazon, 2016[21]), to train algorithms to generate recommendations based on user purchase history, product recommendations and ratings history. Personalised recommendations play a large part in steering consumer behaviour online – for example, some have estimated that 80% of Netflix activity is driven by algorithmic recommendations (Financial Times, 2016[23]).

Academic work has found that changes in algorithmic design can alter the rate of matching between buyers and sellers in the context of online platforms (Fradkin, 2017[19]), thereby improving overall engagement and the likelihood of matches. This is particularly important where online platforms earn revenue through successful transactions, as failed matches can cause actors to exit the marketplace.

Consumers typically express an initial preference by outlining core characteristics of the product or service they wish to buy (e.g. a product name or a location). The online platform’s search algorithm then offers a set of results for consideration for the consumer. This set of results may be derived from the online platform’s indexed knowledge of product and seller characteristics (see Box 3.2), and could be personalised based on the online platform’s existing knowledge of the buyer. The consumer will then typically use features in the search interface, including filter mechanisms, to refine the search results to determine the product or service that best matches their preferences. A range of academic work finds that the ranking of search results influences a consumer’s choice of what to purchase (Ursu, 2016[25]).

In general, when the online platform only benefits from user engagement (advertising revenue) or from a successful transaction (commission or selling fee), matching mechanisms are essential for the platform’s business model. Matching mechanisms are also often associated with pricing arrangements (see Box 3.5).

Pricing strategies on online platforms differ in accordance with the nature of the good or service on offer and buyer and seller characteristics. Some pricing arrangements are closely associated with the matching process on online platforms.

For example, Uber uses a pricing mechanism that operates in tandem with the process of centralised matching. Uber acts as the price-setting agent, dynamically changing prices in response to market conditions to facilitate matches in real time. “Surge pricing” of this nature can help clear markets faster and minimise transaction costs for buyers and sellers, thereby enabling e-commerce, although some consumers have complained about such practices (Riley, 2017[26]). Dynamic pricing is evident in other markets, including the airline industry.

As noted above, e-commerce enables the online sale of goods and services in niches that were previously unprofitable to offer for sale offline. However, as these goods and services typically also have comparatively smaller markets, pricing such goods is not necessarily obvious. Auction mechanisms are useful as a means of price discovery in these cases, particularly for unique or used products (Einav et al., 2017[27]), although transaction costs for buyers typically increase. Auctions are also often used for heterogeneous services, such as task-mediating services like Upwork and Thumbtack, where the specificity of the task results in a lack of an alternative price-setting mechanism with lower frictions (Fradkin, 2017[19]).

In the early days of e-commerce, auction mechanisms were prevalent on online platforms. Today, they have declined in use in the retail market, particularly for standard goods with large markets. On eBay, an e-commerce platform and online auction house, the share of auctions in the active listings declined from over 90% in January 2003 to just approximately 15% in January 2013 (Einav et al., 2017[27]). A notable exception is the use of advertising placement auctions for digital marketing purposes, as used by Google and Yahoo, and the use of bidding and auction systems to determine the ranking of products on many price comparison platforms.

The simplest and most common prices found on online platforms are those determined and posted by the seller. Seller-determined prices remove the physical and cognitive transaction costs associated with bidding in an auction. Seller-determined prices enable sellers to change easily their prices in accordance with their preferences (e.g. Airbnb hosts can easily change prices in accordance with their own schedule or requirements). The decline in the relative share of auctions on retail e-commerce platforms, and the growth in seller-determined prices, suggest that buyers may also prefer this format in many cases.

Online intermediaries are in a unique position to collect data about users on both sides of the market, including but not limited to transaction data, demographic data, and data on user behaviour, among others. This data may be offered, observed or inferred. When used in combination and potentially matched with other data, the price-setting agent may be in a better position to determine the consumer’s reserve price – namely, the highest possible price that each individual may be willing to pay.

This practice is known as personalised pricing, whereby some consumers may pay less for a given product and others may pay more than they would have done if all consumers were offered the same price (OFT, 2013[28]). While there is little empirical evidence of the use and extent of personalised pricing, by virtue of being personalised, such practices may be difficult to detect and monitor. Nonetheless, recent OECD work suggests that firms have the technical potential to personalise prices, and consumers report having experienced the practice, including on online platforms (OECD, 2018[29]). Personalised pricing practices have uncertain impacts of overall competitive conditions and consumer welfare.

The OECD Recommendation on Consumer Protection In E-Commerce (OECD, 2016[30]) notes that businesses should “provide information about the … costs associated with a transaction that is sufficient to make an informed decision.” When firms personalise prices, they should therefore disclose to consumers that they are doing so. However, such disclosures may have uncertain impacts on consumer behaviour (OECD, 2018[31]). Future experimental work from the OECD will aim to identify which approaches to disclosure are effective in enabling consumers to identify and comprehend personalised pricing, and the extent to which disclosure has a material impact on consumer decision making.

Approaches to increase trust

E-commerce platforms bring together buyers and sellers who may be dispersed geographically and involve parties that have not met before. Some sellers on online platforms are large and may have established brands that buyers may trust. In contrast, smaller, potentially unknown vendors may have more difficulty establishing conditions that would lead buyers to transact willingly with them. Third-party providers and sellers operating on multi-sided markets may be further unsure about payment or reliability from buyers who purchase their products.

Online platforms can provide mechanisms that help to resolve this essential information asymmetry, build trust on both sides of the market, and ensure that transactions are safe and reliable to foster e-commerce. Online platforms have the ability to easily collect, store and communicate information to both sides of the market in a verifiable way, particularly when there have been repeat transactions. This enables the entirety of the engagement with the platform, and not simply transaction history with a single seller on the platform, to build trust for online transactions.

In general, analysis on peer platform markets finds that consumers generally trust platforms, sometimes to a greater extent than conventional businesses in the same market (OECD, 2017[32]). Notably, this analysis finds that consumer trust in an online platform is generally higher than trust in unknown third-party sellers that may operate on the platform, and that consumer trust in the platform is the most commonly cited reason for proceeding with transactions even when the buyer may not trust the seller. This indicates that trust mechanisms developed by online platforms can enable more transactions, pushing out the extensive margin of e-commerce.

For many online platforms, a significant ex ante mechanism for building trust includes the performance of verification checks of the identity and/or the credentials of either buyers or sellers. For example, Uber, Lyft and other ride-sharing platforms confirm the identities of drivers through government-issued documentation like a valid driver’s license, vehicle registration, reviews of criminal records, and checks of the suitability of the vehicle. Airbnb verifies the identity of both guests and hosts on the platform through passports, while other online platforms confirm professional certifications and licenses. The verification of identities online can enable e-commerce (see Box 3.6).

Digital identity refers to the set of information used by a computer to authenticate an identity. This identity could be anonymous or pseudonymous, and relate to a civil identity, a corporate identity, or be linked to information provided by a user (age, gender, etc.), or established through browsing, selling or purchasing history. As such, it is possible for individuals or organisations to have multiple digital identities across various platforms and websites that may or may not be connected.

In response to this fractured digital identity landscape, both public and private schemes that seek to create unified digital identities are becoming increasingly prevalent. Government digital identity efforts usually consist of a unique number that links a digital profile to civil information like demographic or biometric data. For example, India’s Aadhaar programme issues a unique number to every Indian citizen which is a valid means of identification vis-à-vis the government as well as private Internet sites including Airbnb, Uber and digital wallet services (Nadadhur, 2018[33]).

Private firms also offer digital identity authentication services. Similar to government schemes, private firms provide users with online identities through mechanisms like unique numbers or accounts that verify a user’s identity across a variety of Internet sites. In contrast to centralised government efforts, this identity may be separate from a user’s civil identity or may be linked to only certain aspects. Facebook is one such private actor that increasingly acts as a digital identity provider. For example, many sites give users the option to use Facebook account information as identity verification instead of creating a new username and password.

Digital identities present a number of opportunities for buyers and sellers alike. For one, when sellers have access to information about buyers’ diverse tastes through their digital identity, they can make better use of algorithms that tailor their advertising and content specifically to the buyer’s needs. Such tailoring decreases bounce rates (the proportion of users that leave a website without making a click) and reduces cart abandonment (the phenomenon of placing an item in a digital checkout cart but not carrying out the sale), while increasing overall conversion rates (the proportion of users that make a purchase) (Deloitte, 2017[34]). Overall, digital identity schemes that share information with e-commerce firms can make sellers more efficient and profitable.

For consumers, these digital identity mechanisms can also represent an advantage in terms of ease-of-use and security. When users have a digital identity across many sites, they do not need to manually re-enter personal data such as shipping details, and are less likely to make mistakes when filling out online forms. With a unified digital identity, users also no longer need rely on an ever-growing list of passwords or the individual security systems of many different and potential unsecure sites to protect sensitive data (Deloitte, 2017[34]; Eggleton, 2016[35]).

Digital identities also pose certain drawbacks, particularly for buyers. Privacy issues and lack of control of personal data may be exacerbated by digital identity schemes, which could share personal information with e-commerce sites. For example, those taking part in the Aadhaar digital identity scheme have been reticent to link this data to certain functions like their digital wallets (see below) due to privacy concerns (Nadadhur, 2018[33]). To a large extent, the real impact of digital identity on e-commerce will depend on the nature of the digital identity systems adopted as well as how much user information is deemed appropriate to share with e-commerce firms. Policy makers therefore play a pivotal role in the development of digital identity in e-commerce and the level of control that buyers have over how their personal data is shared.

Security risks are another potential drawback of digital identities. Although digital identity schemes may offer buyers the opportunity to consolidate password data, these mechanisms themselves are not impervious to digital security threats. Particularly in the case that data associated with a digital identity are not anonymised, digital identities may be easily linked to sensitive administrative information like social security numbers or national identification data, and then exploited by third parties. Even when data are anonymised, digital identity schemes could in fact leave users more vulnerable. If a data breach of a centralised digital identity occurs, third parties could access users’ most sensitive data all in one place (Domingo and Enriquez, 2018[36]).

Beyond these potential advantages and disadvantages, interoperability issues create further challenges for the relevance and efficiency of digital identity initiatives. As both centralised government initiatives and private digital identity firms multiply, the ability of these systems to interact with one another influences the role that digital identity can play in e-commerce. Namely, the relevance of the benefits (and risks) of digital identity in the e-commerce sector may be muted if interoperability issues are not resolved.

Another significant ex-ante mechanism for building trust includes the imposition of minimum quality standards. Drivers wishing to participate as sellers with Uber in its American marketplace must pass a 19 point vehicle inspection test with a registered mechanic before their account can be activated (Uber Partner Help, 2018[37]). Third-party sellers on online platforms may be required to meet a minimum standard of service as a condition of using the platform; for example, some third-party sellers on Amazon must meet minimum requirements for returns and delivery times (Levy, 2016[38]; Levy, 2017[39]).

The most common ex post trust-building mechanism on online platforms is the use of reputation and review systems, whereby one or both sides of the transaction is able to rate or review the transaction through a mechanism that can be viewed by other users in the marketplace. Both reputation and review systems are a form of public good. Recent OECD work on trust in peer platform markets finds that reviews and ratings are important for consumer engagement with online platforms (OECD, 2017[32]).

Reputation systems track the performance of a user over time and help other users determine whether they wish to transact with them. They are an important mechanism of reducing moral hazard and information asymmetry between different sides of the market. Reputation systems were initially pioneered by eBay but have subsequently spread to most online platforms (Luca, 2016[40]), indicating their utility as a trust-building tool in e-commerce.

Research on online platforms like eBay and Amazon finds that the reputation of a seller impacts demand from buyers (Tadelis, 2016[41]). In the case of Airbnb, analysis suggests that incentivising reviews by offering a USD 25 coupon could improve the usefulness of the review (Fradkin et al., 2017[43]), while other research on Alibaba’s Taobao platform found that rewarding feedback with a coupon could be used as a signal of the quality of the seller (Li, Tadelis and Zhou, 2016[44]). However, there is a risk that reviews that are compensated could be biased (Cabral and Li, 2014[45]). Sellers may also have perverse incentives to manipulate their reviews (Mayzlin, Dover and Chevalier, 2014[42]).

Product reviews are another form of feedback often used by online platforms. They enable buyers to review the quality and utility of the product (as opposed to the seller). These ratings are a means of ensuring that product quality on online platforms remains high, as low ratings impact sales (Chevalier and Mayzlin, 2006[46]), particularly when the ratings have been judged as useful by others (Chen, Dhanasobhon and Smith, 2008[47]). Private surveys also find that consumers trust online reviews to a similar degree as personal recommendations (Bright Local, 2017[48]).

Product reviews have significant impacts on offline behaviour as well. Pew Research finds that 45% of consumers check reviews before purchasing in a physical store (Pew Research Centre, 2016[49]), while Google finds that mobile searches for product reviews increased by 35% from 2015 to 2017 (Google, 2018[50]). This underscores the degree to which digital technologies are embedded in offline purchasing (see below).

Consequently, online platforms have experimented with mechanisms to ensure the review system’s quality, including using machine learning to display reviews that are more useful to other consumers (Rubin, 2015[51]). Some online platforms have also taken action against third-party sellers over attempts to manipulate ratings with fake or misleading reviews (Perez, 2016[52]; Broida, 2019[53]; Statt, 2019[54]).

Some online platforms have used other features to improve trust between unknown parties. Airbnb and Uber offer insurance to sellers for property damage that occurs during the course of a booking or transaction. In addition, some online platforms act as an mediating party should a dispute occur between the buyer and seller in a transaction, while others have customer service and return options for dissatisfied buyers. Some online peer-to-peer lending platforms, including Lending Club and Prosper, use algorithms to detect and protect against fraud (Xu, Lu and Chau, 2015[55]).

Blockchain is a technology that enables applications to authenticate ownership and carry out secure transactions for a variety of asset types (OECD, 2019[56]). For so-called public or unpermissioned blockchains, actors are able to verify transactions without the need of an existing trusted relationship through both cryptographic and market-designed incentives. Blockchain technologies are emerging and have yet to be applied in many domains or integrated into policy frameworks. However, as a radical means of facilitating disintermediated transactions, Catalini and Gans (2017[58]) note that blockchain could significantly bring down the costs of verification and networking associated with economic transactions, including e-commerce.

In the context of e-commerce, blockchain removes the need to use an intermediary for third party verification for trusted transactions. This could facilitate the development of distributed, peer-to-peer networks with multiple sides without the need for a centralised online marketplace. One emerging peer-to-peer marketplace of this nature is OpenBazaar, which features no fees for listings, selling or commissions, and accepts over 50 cryptocurrencies as payment (OECD, 2017[18]). Marketplaces like this could theoretically challenge the business model of firms that act as intermediaries between different sides of a market.

Other potential applications of blockchain related to trust could involve the development of a portable and decentralised reputation system. As noted above, reputation and review mechanisms have emerged as important enablers of e-commerce by increasing trust through the publication of previous transaction history. However, these rankings are not transferable from marketplace to marketplace, which could theoretically increase switching costs for users. Chlu, a new start-up, aims to provide a transferable record of a vendor’s reputation, using the immutable and public nature of blockchain, while also keeping them private using advanced cryptographic solutions (Chlu, 2018[59]). Such a system could also be used to aggregate rankings and performance from multiple online platforms or communities.

Mechanisms to facilitate firm participation

While the specific design of online platforms differ, each platform has incentives to add users, meaning that the entry costs for sellers that wish to participate on online platforms are typically low. This gives small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) and, in some cases sole traders, the ability to compete alongside more established firms on online platforms. When online platforms operate in multiple international markets, being active on the platform can give sellers access to new markets overseas.

However, there are a range of complementary investments that sellers may need to make to effectively buy and sell online. Trading at a distance, including potentially across borders, requires significant upstream and downstream investments in supply chain management, secure payment systems, delivery and fulfilment mechanisms, and customer-facing services like dispute resolution mechanisms and customer service. For e-commerce across borders, these activities may need to be conducted in foreign languages. Notably, these are all factors mentioned by firms as influencing their decision not to participate in e-commerce (see Chapter 2).

As a result, online platforms have begun to offer complementary services for firms that trade on their platform, including fulfilment, logistics, customer service and software-as-a-service (SaaS) offerings. SMEs disproportionately benefit from these services because they would otherwise require significant upfront fixed costs, while platform-enabled services can transform this fixed cost into a variable cost. These new solutions push out the extensive margin of e-commerce, enabling new participants to enter the marketplace.

Many major online platforms such as Amazon, Alibaba and Rakuten, offer fulfilment services to sellers that operate on the marketplace. These services are often integrated with the broader sales management interface of the platform and compete with other international fulfilment service providers, including Shipwire, Whiplash and Cloud Fulfilment. Such fulfilment services may be particularly useful in countries without a well-developed postal system or with a limited number of third party logistics service providers (see Chapter 2).

In the case of Amazon, there are over 2 million active sellers worldwide on Amazon Marketplace, and they are responsible for over half of the sales made on Amazon’s platform (Amazon Investor Relations, 2015[60]). Amazon’s fulfilment service, known as “Fulfillment by Amazon”, enables these sellers to use Amazon’s supply chain for downstream services including storage, packaging, shipping and foreign language customer services. Membership in the Fulfillment by Amazon programme enables third-party sellers to gain access to Amazon’s lucrative Prime subscriber base (discussed below).

In 2016, Amazon shipped more than 2 billion items for third-party vendors through Fulfilment by Amazon (Amazon, 2018[61]). In 2017, Amazon reported a 70% year-on-year increase in vendors using Fulfillment by Amazon. Revenues from services provided to third-party sellers, which includes commissions and any related fulfilment and shipping fees, and other third-party seller services, had grown to almost USD 43 billion by 2018, more than triple its value in 2014 (Amazon, 2018[61]).

Other online platforms include services that are specifically aimed at cross-border e-commerce, thereby enabling SMEs to access international markets. This appears to be a notable feature of online platforms that operate multiple, country-specific marketplaces. Thus, Amazon operates over 11 marketplaces in different legal jurisdictions and regions (Amazon, 2018[62]). Amazon customers from over 180 countries are then able to purchase through these marketplaces. Amazon sellers must meet certain listing and registration requirements prior to operating on an international marketplace (Amazon, 2018[62]). Amazon also provides legal and regulatory information specific to each jurisdiction for sellers, and directs international sellers to third-party solutions providers for advertising, customs brokerage and tax assistance.

Another large firm using an online platform is eBay, which operates almost 30 international websites, but offers no formal restrictions on listing in overseas marketplaces aside from the buyer’s indication of willingness to ship overseas. For US and UK-based sellers, eBay has developed an export logistics service for international sales, shipping and customs clearance, called the eBay Global Shipping Programme. Sellers send goods purchased on the platform to a domestic intermediary, who then handles the customs, taxes, tracking, insurance and shipping associated with the export process to over 80 countries (eBay, 2018[63]). This service also enables sellers to avoid any negative feedback (see the sub-section above on reputation mechanisms) or any damage that results from international shipping.

An analysis of the impacts of this programme finds that cross-border trade increased exports at the extensive margin by targeting SMEs, for whom export costs were otherwise prohibitive (Hiu, 2016[64]). The analysis also finds that the programme increased trade in products with smaller price-to-shipping ratios, while foreign consumers benefited from an increase in marketplace quality and product variety.

Other online platforms have pursued similar cross-border strategies for SMEs in other parts of the world. For example, the Chinese online platform Alibaba recently announced plans to open an electronic world trade platform in Malaysia. This online resource aims to provide Malaysian SMEs support with tariffs, customs and logistics associated with international trade. The electronic resources are complemented by a regional distribution centre established by Alibaba’s partners, and additional co-operation with respect to payment mechanisms (Alibaba, 2017[65]).

More generally, an analysis by eBay found that among the micro, small and medium-sized enterprises (MSMEs) from 18 advanced and developing economies operating on its platform, about 90% to 100% sold internationally, and were also likely to serve multiple markets (eBay, 2016[66]). Recent analysis by the OECD and the World Trade Organization (WTO) also identified online platforms as useful mechanisms for enabling international trade for SMEs in developing countries (OECD/WTO, 2017[67]).

Subscription e-commerce business models

Another business model that is of increasing interest in e-commerce is the subscription model. This business model is characterised by regular and recurring payments for the repeated provision of a good or a service. In the e-commerce context, this encompasses a range of new and emerging businesses, from streaming services like Netflix to recurring purchases of consumer products like Dollar Shave Club. The subscription business model can relate to recurring purchases of digital goods and services, or a combination of both digital and tangible products (such as a newspaper subscription that includes access to digital content).

Subscription e-commerce business models typify a broader trend towards more continuous, digitally-enabled access to or provision of goods and services. Digital technologies enable easy ordering of goods and services, removing transaction costs associated with the purchasing process, thus improving convenience for consumers. Firms benefit from regular and ongoing revenue streams. The OECD E-Commerce Guidelines recognise the increasing importance of subscription models to e-commerce, and note that firms should disclose to consumers: “terms, conditions, and methods of payment, including … recurring charges, such as automatic repeat purchases and subscription renewals, and ways to opt out from such arrangements” (2016[30]).

Access to digital products by subscription

One aspect of the emerging trend of e-commerce subscription business models is subscription access to digital products. This encompasses the ordering of intangible products that can be delivered online, including software, media and services like cloud computing. These services increasingly form part of larger supply chains for some firms, or are bundled or complementary to other purchases.

Subscription models have become a feature of successful media companies, and provide a means of diversifying revenue streams away from advertising. As digital media is easily reproducible and shared, subscription services are predicated on access to a wide range of media content rather than individual purchases of specific content.

Many emerging subscription services offer access to digital products that are only tradeable as a result of digital transformation, like software services. As noted in economic literature, the pricing of non-rivalrous digital goods with low or zero marginal costs is not always obvious for firms. One solution is bundling many digital products and charging a single price (Bakos and Brynjolfsson, 1999[68]; Bakos and Brynjolfsson, 2000[69]). Some current e-commerce subscription business models, such as Spotify or Netflix, are practical examples of this theoretical insight (Goldfarb and Tucker, 2017[70]).

Blockchain enables new kinds of decentralised and radically transparent markets and business models. For example, business models that aim to monetise content creation, like traditional music labels or film studios, have been negatively impacted by easy duplication and sharing of digital products. Some firms have created new digital media business models that earn revenues through subscription access to bundles of digital products, who funnel a share of revenues to content creators.

As the use of assets and transactions can be automatically captured in a detailed and transparent way on a blockchain, it becomes increasingly easy to price and deliver access to information and digital goods with a high degree of precision. This in turn may provide a new business model for the purchase and sale of digital content. For example, the Open Music Initiative (2018[72]) is an example of a start-up that aims to use blockchain technologies to promote and enforce digital rights management to enable compensation for artists.

Some digitalised subscription models pursue a so-called “freemium strategy” whereby usage of or access to content is provided with some limitations, or only when users accept exposure to advertising. Those who pay the relevant subscription fee may enjoy a more extensive level of service, which may include additional content or the absence of advertising. This model can help new and small firms gain market share by enabling the consumer to experience the service without initial up-front costs. As those users who pay for premium services are also likely to use the service more, firms are able to scale up responsively (European Commission, 2015[73]).

An example of the freemium model is used by The New York Times, which aims to convert revenues from subscriptions of printed newspapers into digital subscription services. In this model, there is a a paywall that emerges after a user accesses a certain amount of free content (Kumar et al., 2011[74]). The New York Times’ digital subscription revenues exceeded USD 1 billion in 2017 (Ember, 2018[75]).

In 2018, the United States Recording Industry Association estimated that music streaming accounted for 75% of American music industry revenues (RIAA, 2018[76]). At the end of 2018, the music streaming firm Spotify, one of the vanguards of the streaming business model, had 207 monthly active users, of which 116 million were freemium (ad-supported users). Approximately 96 million users had subscribed to a full subscription package (Spotify, 2018[78]). Consistent growth in premium subscriptions enabled Spotify to make a profit at the end of 2018 for the first time in its history. However, the company’s business model relies on paying royalties to content holders, which amounted to approximately 70% of its revenues in 2018 (Financial Times, 2018[79]).

Software and information technology applications are other intangible products that are increasingly ordered online as an ongoing service through a subscription business model. Typically, the model includes the licensed provision of software and other information technology applications over the Internet. Ubiquitous computing and the extensive use of cloud hosting underpin this business model (see Box 3.9).

Subscription e-commerce business models for software and information technology applications increasingly replace legacy pricing arrangements, which typically involved a single, perpetual license for a specific version of a product. One example is Adobe, a software provider that converted its full service offering into the cloud-based Adobe Creative Cloud suite (Sanitago, Gnanasambandam and Bhavik, 2018[81]). This enables dynamic service provision with ongoing updating and re-versioning of features and functionality, rather than a two- or three-year production cycle. Ongoing collection of data on customer use and preferences enables more tailoring to specific user needs.

Such business models are also more scalable, and in some cases can be offered at a price point competitive enough to attract new customers. This could include SMEs which may be able to convert the cost of investing in ICTs into an ongoing operating cost. Downward trends in information and communication technology (ICT) investment in OECD countries over time suggest that firms may indeed be using cloud computing to substitute for other kinds of investment (OECD, 2019[56]).

Cloud computing refers to a service model that provides clients with flexible on-demand access to a range of computing resources (OECD, 2014[80]; OECD, 2019[56]). As a set of combined technologies, cloud computing provides individuals and organisations with the ability to access resources, including software applications, storage capacity, networking and computing power) through an online interface. Some well-known variants of the cloud computing service model (OECD, 2018[4]) include:

-

Infrastructure-as-a-service (IaaS): IaaS refers to the delivery of infrastructure such as computing capacity. Also known as hardware-as-a-service, IaaS encompasses all of the physical computing resources that support delivery of applications as a service, such as computing services, database storage and networking capabilities. IaaS provides major cost savings to customers, as it provides access to additional computing capacity on demand, without the need for major capital investments in additional hardware.

-

Platform-as-a-service (PaaS): PaaS is a method by which an entire computing platform can be utilised remotely over the Internet via cloud computing. PaaS refers to a broad collection of application infrastructure, including operating systems, application platforms and database services. PaaS provides a way for customers to outsource their platform infrastructure needs and therefore avoid the need to purchase and implement a new platform. This service model typically allows cloud computing companies to charge customers only for the share of the resources they use, which is especially useful for a business that requires a specific application it would only use on occasion.

-

Software-as-a-service (SaaS): SaaS is a software model that incorporates the delivery and management of a software application to a remote client via the Internet. SaaS relies on the centralised hosting of a software application that is typically accessed via a web browser application. SaaS can be configured to allow public access or private access, where only users with the proper credentials are granted access to a particular hosted software application.

These computing resources can be priced on-demand and used in a flexible, scalable and adaptable manner, enabling users to reduce the costs of fixed investment in ICTs. Cloud computing therefore increases the availability, capacity and ubiquity of computing resources in a way that enables other digital technologies, including AI and autonomous machines like drones (OECD, 2015[6]; OECD, 2017[18]). It also allows users, like SMEs and individuals, to access computing resources that would otherwise be prohibitively expensive.

An interesting extension of this trend is the growing competitive marketplace of PaaS models for businesses wishing to sell online – namely, a form of e-commerce that has emerged from the growth of e-commerce itself. Shopify, BigCommerce, Lemonstand and Magento are all PaaS solutions for businesses that wish to build online stores. While they range in features, these packages typically offer website hosting, thematic design options, payment gateway services, analytics, as well as inventory and fulfilment integration, and they tend to integrate with multiple online sales channels, including social media. Shopify, one of the earliest and best-known e-commerce PaaS vendors, hosts more than 600 000 active online stores and has facilitated USD 55 billion of gross merchandise volume (Shopify, 2018[82]). In 2015, Amazon closed its own native PaaS offering (Amazon Webstore) and directed its merchants to Shopify, which remains the case today.

Subscription access to tangible and bundled goods and services

A recent e-commerce trend has been the growth of subscription business models for tangible goods, including in categories like beauty supplies (Birchbox), minerals (Celestial Minerals), groceries (Blue Apron, Hello Fresh), snack foods (Nature Box), cosmetics and self-care products (Dollar Shave Club, Harry’s), and many more.

This sector of e-commerce has grown in value over the last five years, and the largest of these retailers generated more than USD 2.6 billion in sales in 2016 (Chen et al., 2017[83]). While this space is volatile, new entrants have drawn significant interest from venture capitalists in recent years and there have been some notable success stories. For example, Dollar Shave Club, a subscription service for shaving materials founded in 2011, gained 5% of the US market share in razor cartridges within five years when it was acquired by Unilever for USD 1 billion (Cao and Mittelman, 2016[84]).

Many of the subscription business models for tangible goods and services relate to goods and services that deplete with use and require replenishment (Chen et al., 2017[83]). An interesting development in this space has been the use of connected devices that utilise streams of data through sensors, software and network connections associated with physical goods to make continuous or recurring purchases of tangible goods. For example, over the last five years, smart home speakers have emerged as a popular consumer good. These smart home speakers use a combination of AI and cloud computing to respond to natural language requests.

Many of the leading retailers of these devices are associated with popular online e-commerce brands, including Amazon, Google, JD.com and Alibaba. These devices are able to make digital and physical purchases in response to voice commands (Amazon, 2018[85]; Bateman, 2016[86]; Cadell, 2017[87]). Recent reports have noted that users of these devices appear to have increased their purchases of standardised products that require replenishment, including paper towels and diapers (Kim, 2017[88]; Pandolph, 2017[89]). Some firms that sell smart home speakers have encouraged this trend by offering voice-exclusive deals for specific products (Warren, 2017[90]).

An extension of this trend is the use of connected devices that automatically order goods that require replenishment. In some cases, “smart” appliances can automatically detect when they run low on essential supplies and automatically purchase additional supplies. For example, the Amazon Dash programme (Amazon, 2016[91]) enables the automatic replenishment of supplies for connected devices like dishwashers, washing machines, printers and water filters.

Other forms of e-commerce subscription services rely on a mix of bundled digital services and tangible goods and services. This has been a common form of diversification for conventional media companies – for instance, in return for a fee, many newspapers offer regular delivery of physical newspapers alongside open digital access to their website. Notable media companies who pursue this model include The Economist (The Economist, 2019[92]), Le Monde (Le Monde, 2019[93]) and the Financial Times (Financial Times, 2019[94]).

An example of this model is Amazon’s subscription service know as Amazon Prime, which enables access to a range of tangible services (free shipping, food delivery) alongside access to digital services (free streaming of video and music content). Amazon Prime offers fast delivery (usually under two days) for all purchases on eligible products without additional cost. Amazon Prime subscribers in some major cities are able to receive shipping within two hours without additional cost. Depending on the country, Amazon Prime membership also offers access to additional services including free streaming of video and music content, free access to popular e-book titles, restaurant delivery and data storage. There were over 100 million paid Prime members across the world in 2017 (Amazon, 2018[95]), who had access to unlimited free shipping on over 100 million items (Amazon, 2018[95]). Amazon gains an increasing amount of revenue from retail subscription services, which have more than quintupled in revenue since 2014 to almost USD 14.2 billion in 2018 (Amazon, 2018[61]). Retail subscription services captures not only revenues from Amazon Prime but also other Amazon subscription services.

As more transactions go online, fast and efficient delivery of tangible products becomes more important. Many of the biggest e-commerce providers have succeeded in improving their delivery time by optimising the logistics and supply chain fulfilment process. However, consumer demand for free and fast shipping services and the high rate of returns for some items have resulted in significant costs. Amazon, for example, posted net shipping expenses of USD 27.7 billion in 2018 alone and has driven further innovations in the delivery process (Amazon, 2018[61]).

In particular, firms have attempted to innovate in the provision of delivery services for the final leg of delivery to the requested location, or the so-called “last mile”. The costs of the final last mile of delivery can comprise up to half of the product’s total transportation costs and is subject to considerable expenses in terms of fuel, vehicle, labour and time costs (McKinsey, 2016[97]).

Some e-commerce firms have experimented with the use of autonomous delivery devices, including the use of unmanned aerial vehicles (commonly known as drones) or autonomous ground vehicles and robots. Autonomous devices are connected devices that make use of developments in cloud computing, machine learning and data to make sense of constant streams of data from a wide variety of sensors.

In the People’s Republic of China (hereafter “China”), JD.com won a national pilot for the use of its smart drone technology, which has been in development since 2015 (Meredith and Kharpal, 2017[98]). Seven types of drones are in use across four Chinese provinces to deliver packages weighing from 5 to 30 kilogrammes, with plans to test the delivery of packages up to 1 000 kilogrammes. The drones are battery powered, can fly up to 100 kilometres per hour, and could reduce shipping costs by up to 70%. JD.com has plans to open more than 200 drone airports in mostly rural areas across China (JD.com, 2017[99]), potentially driving access to a larger scope of goods and services through e-commerce. In collaboration with the Japanese e-commerce platform Rakuten, JD.com will deploy this technology for local deliveries in Japan in 2019 (Lim, 2019[100]). However, many countries and regions still ban the commercial use of drones in urban areas (ITF/OECD, 2018[101]).

Another interesting development is the use of autonomous ground vehicles and robots for last mile deliveries. Some forms of lightweight autonomous robots are being tested to make deliveries in the city of Washington, District of Columbia (D.C.). These pilot robots are approximately 70 centimetres tall, weigh approximately 23 kilogrammes and can carry approximately 10 kilogrammes of products, but are restricted to speeds of just 6.5 kilometres per hour. The robots use cameras, computer vision and artificial intelligence to navigate sidewalks and urban environments, albeit currently with human supervision (Lonsdorf, 2017[102]), and just five such robots made over 7 000 deliveries over a period of 18 months. Most transport and zoning regulations do not have provisions that enable the use or testing of such devices. Recently, a pilot program was extended to enable further testing of so-called “personal delivery devices” in Washington, D.C. (Washington DC District Department of Transport, 2018[103]).

Online-offline e-commerce business models

Consumers increasingly leverage online tools throughout the lifecycle of the commercial process, including for research, price comparison, delivery and customer service (Verhoef, Neslin and Vroomen, 2007[104]). This includes the ordering process, which is at the core of an e-commerce transaction (see Chapter 1). Digital technologies, including mobile applications, self checkouts, electronic kiosks and smart shelf technology, have become increasingly embedded in each stage of the retail process. To a large extent, the ubiquity of these tools is driven by the rise of mobile commerce and the spread of high-speed broadband in many parts of the world.

Many firms have taken advantage of the ubiquity of digital technologies to develop business models based on a combination of both online and offline features. These business models serve as extensions of e-commerce, pushing the frontier of online purchases into physical stores (see Box 3.12). Some business models combine online ordering with offline distribution, which may be useful to enable the online purchase of products whose quality may not be assessed from a distance, such as perishable goods like groceries. Other online firms are moving offline by adding brick-and-mortar elements to enable the online sale of other goods, like clothing, where fit may be difficult to assess from a distance. Finally, some business models combine offline and online mechanisms by bringing online ordering very close to the point of purchase, including within brick-and-mortar stores.

Mobile technologies enable consumers to conduct a range of digital activities, including online shopping. Consumers use digital technologies throughout the commercial process, but smartphones enable shoppers to research, compare prices, and ultimately make transactions from any networked location. A Google survey found that 82% of surveyed consumers research products on their smartphones before making purchases in brick-and-mortar stores (Google, 2016[105]). The actual act of purchasing through a smart, connected device is referred to as “m-commerce,” whereby consumers complete a commercial transaction using a mobile device (OECD, 2013[106]).

OECD work highlights m-commerce is an emerging trend (OECD, 2013[106]) with ramifications for consumer protection (OECD, 2018[107]). The ubiquity of smartphones is the foundation for many of the online aspects that can be increasingly found in offline commerce. Smartphone features also enable other innovations in the retail space, including location-based offers (Grewal et al., 2016[108]). Similarly, the ability to purchase goods and services by mobile application is central to some of the business model innovations outlined in more detail below.

Online-offline distribution mechanisms

As e-commerce has become more prevalent, many conventional firms and retailers have experimented with the inclusion of online distribution channels alongside their existing brick-and-mortar operations. However, leveraging the Internet, or other electronic networks, to integrate e-commerce into an existing firm-level business model often requires a range of complementary investments and capacities. This can include, but is not limited to, supply chain and fulfilment arrangements and consolidated inventory systems.

The most common form of e-commerce consists of simple direct shipping to the customer’s home after they have purchased online from a distance and without the physical inspection of the product. However, this carries delivery costs arising from dispersed fulfilment and delivery chains, or dependence on third-party logistics services (see Box 3.11). Thus, many firms are experimenting with mechanisms for fulfilment through existing physical infrastructure or retail locations.

For example, many firms have developed “click-and-collect” mechanisms to enable consumers to order and purchase online, while collecting the relevant items in a local brick-and-mortar store or another location such as a locker. This allows consumers to immediately purchase the good or service online, but to save on shipping costs, delays and inconveniences associated with delivery. Notably, this mechanism enables firms to retain their current centralised inventory system and reduces operational costs associated with physical brick-and-mortar stores, while also acquiring useful data about the user.

To the extent that click-and-collect mechanisms are located in a brick-and-mortar store, this mechanism may also allow consumers to check the quality and assess the colour, style and size of the product within the store itself. In addition, consumers are able to make returns in store, which may increase their propensity to purchase online. A survey by the United Parcel Service (UPS) finds that consumers were more willing to purchase online if they could return in a brick-and-mortar store (United Postal Service, 2018[109]).

Other interesting developments in this space include curbside fulfilment, whereby consumers can order groceries online and then drive to their local brick-and-mortar store for immediate fulfilment (Howland, 2016[110]). This model enables retailers to minimise expensive investments in home-delivery supply and logistics systems, and has been adopted by major retailers like Walmart, Amazon, Target and Nordstrom.

Online groceries – A new e-commerce frontier

In its most conventional form, e-commerce consists of committing to buy a product online, usually using a device that is not close to the product purchased. However, many products are perishable, or they may have quality characteristics that are difficult to assess online, through pictures or at a distance. For example, private surveys have found consistently high estimates (69% to 84%) of surveyed US consumers prefer to purchase fruits and vegetables in brick-and-mortar stores in order to physically assess the quality and suitability of the product, which may be because fresh products are of variable quality and individuals have subjective tastes (Griswold, 2017[111]; Nielsen, 2017[112]). Perhaps as a result, this category of online shopping has seen comparatively little growth so far (see Chapter 2).1

Developing an effective method of selling groceries online could be an opportunity for firms, as groceries, including food and non-alcoholic beverages, accounted for 14% of household expenditure on average across 34 OECD countries in 2017 (OECD, 2019[113]). Some private sources find that consumers take 1-2 trips to the supermarket each week, representing significant friction and inconvenience that could be mitigated through e-commerce (Food Market Institute, 2017[115]).

Many firms have attempted to develop processes to successfully sell perishable food and groceries online. Some online business models offer direct shipping of purchased groceries alongside guarantees related to quality and customer satisfaction to give consumers confidence in the purchase of perishable goods and services. However, this model typically necessitates the development of a cold-chain direct fulfilment and logistics system, which is expensive. Instacart, an emerging start-up in this space, enlists contract workers to physically select the relevant groceries ordered by the consumer and drop them off at their desired location. Instacart provides detailed instructions to its contractors about how to select produce in order to meet minimum quality standards (Griswold, 2017[111]).

Some firms include online and offline components in order to successfully sell groceries online. For example, Alibaba, a Chinese e-commerce online platform, has refined its business model to facilitate the sale of perishable goods and services by opening brick-and-mortar stores. Over 25 Hema supermarkets have been opened across China for the sale of perishable goods including live seafood, fruits and vegetables. The supermarkets also act as fulfilment centres for purchases made online through the Hema application. Customers within a 3 kilometre radius can order products online and have their orders hand-selected by store workers and then delivered to their home within 30 minutes using smart logistics technology (Xiaohan, 2017[116]).

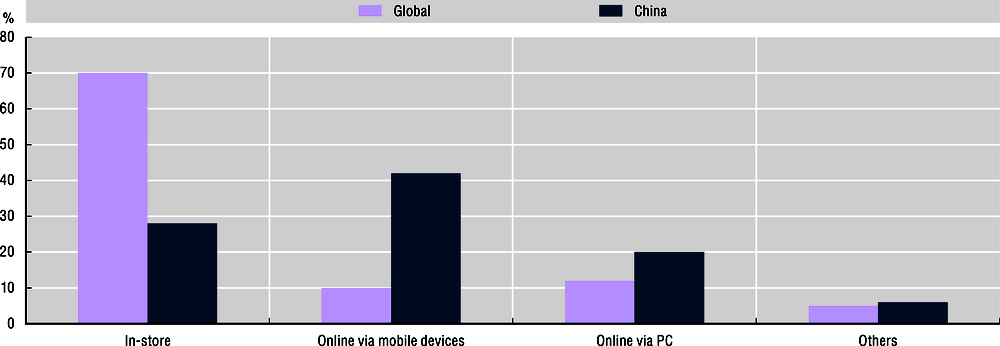

Data and insights from its online business enable Alibaba to optimise the brick-and-mortar experience inside Hema stores, resulting in 300% to 500% more sales per unit area than other supermarkets (Najberg, 2017[117]). Customers who use the application make purchases up to 35% of the time they use the application (conversion rate), while online orders account for more than 50% of all sales from Hema. Notably, the rival Chinese e-commerce firm JD.com is following suit by opening new digitally infused brick-and-mortar experiences and also has plans to develop fully automated convenience stores (see below) (Bloomberg, 2018[118]). A global survey found that Chinese customers may be more willing than other consumers to buy groceries online (Figure 3.1).

In Alibaba’s Hema supermarkets, a companion mobile application is available to enable shoppers to determine the origin and provenance of perishable fruits and vegetables. Another new technology trialled for product safety and quality includes the use of distributed ledger technologies to track product provenance (see Box 3.13).

Existing applications of distributed ledger technology in e-commerce largely relate to tracking the origin and provenance of goods and services to ensure product safety and quality. For example, IBM has collaborated with a range of retailers including Walmart and Costco (Aitken, 2017[120]) to develop a permissioned distributed ledger database that tracks products from supplier to retailer, including information on production, inspection, farm of origin, factory and processing, expiry date, storage temperatures and shipping (Unuvar, 2017[121]).

This is of particular use in systems with multiple intermediaries, including producers, wholesalers, retailers, couriers and regulators, each of which have incomplete information about the upstream and downstream production process. Distributed ledger technologies transform a previously cumbersome and manual process into a system that can provide specific information about product provenance in less than 3 seconds (Unuvar, 2017[121]). A system like this could also be used to ensure that illegal products are not traded, or to ensure that foods labelled “organic” have indeed passed the requirements to be labelled as such.

Going offline to ensure the right fit

Some consumer goods, like clothing, can vary in their suitability based on their fit to the consumer. Thus, while clothing is one of the most popular products bought and sold online (see Chapter 2), the sector has struggled with significant returns. As noted in Chapter 2, approximately 5% of given online transactions were refunds, of which 57% are related to the fashion industry. Consumers may often buy multiple items of a similar size, shape or colour, with the intention of trying them on and returning those that do not fit (Orendorff, 2019[122]).

As a consequence, an interesting emerging e-commerce business model for online fashion businesses is the inclusion of offline features to enable the sale of fit-critical goods and services online. An offline distribution channel re-introduces frictions to the business model and may increase costs, but also increases the extensive margin of e-commerce by enabling new types of products to be sold online. In particular, firms that sell heterogeneous or bespoke products like clothing may benefit from this kind of business model.

For example, several online apparel retailers have opened brick-and-mortar stores that allow consumers to try on products before ordering them online. Bonobos, an American online retailer, has opened over 30 “guideshops” to enable consumers to try the product for fit and quality (Waldron, 2019[123]). Consumers then place their order online, a process that increases conversion, minimises returns and increases the average purchase value. A similar model is pursued by bespoke tailor Indochino, whose service involves an in-person suit fitting service with a second follow-up and in-person alteration. A physical component of the traditional e-commerce experience has been added by online brands including Amazon Books, Birchbox, Bonobos, Daniel Wellington, Harry’s and Warby Parker.

A unique feature of the offline stores provided by these online retailers is that they are purely show-rooms – that is, spaces that are purely for fitting purposes, and the clothes or goods on display at the shop cannot actually be purchased on the spot. The inventories themselves are typically highly curated with a limited selection of inventory to try on. Data from the online business regarding consumer choices and preferences facilitate this selection. This enables the online retailer to avoid complicated “balance on hand” questions about store-level inventory that typically require an extensive separate inventory and logistics chain. This also erodes the so-called institutional capability of traditional retailers to choose the optimal product mix throughout the supply chain, a previous source of comparative advantage (Hodson, Perrigo and Hardman, 2017[124]).

As the actual ordering and purchase of goods and services is typically conducted online (via application), the brand can retain a centralised inventory and distribution chain, and avoid the need for an additional payment system. Moreover, the process increases the conversion of online sales while reducing the additional costs associated with returns of unwanted products. The spaces are often smaller than other brick-and-mortar retailers, and often leased on demand. This approach also increases the productivity of the space itself – as much as five times the revenue per square foot in comparison to legacy retailers – while reducing overall overhead costs (Taggart and Granville, 2017[125]).

These initiatives are also notable as they have been adopted by vertically-integrated brands, whose low price point and value offering is predicated on the ability to cut overall production costs through the curation of the entire product production lifecycle from design to sales. While the offline features re-introduce frictions into the purchasing process for consumers, the seller is able to leverage insights from their core online service offering to maximise the utility of the offline space while minimising the expensive and inefficient burdens associated with traditional retail, like inventory management and point-of-service purchasing. Tellingly, some surveys show that consumers already use brick-and-mortar stores as showrooms in order to browse and understand product characteristics before purchasing online (Freeman, 2014[126]; Khan, 2018[127]).

Online ordering in brick-and-mortar stores

Other firms are increasingly experimenting with the inclusion of online ordering mechanisms within or very near brick-and-mortar stores themselves in order to boost sales, enable customisation and increase efficiency. This appears to be a salient trend for businesses that rely on convenience or service on demand.

Ordering, purchase and payment by application or kiosk for almost immediate pick-up has been adopted by many restaurants. For example, the American fast food chain McDonald’s has installed digital self-order kiosks in all 14 000 of its US stores (Hafner and Limbachia, 2018[128]). These kiosks rely on touch-screen technology to relay information via wireless networks from customer orders to the kitchen, where the meals are made on demand. For some restaurants, the use of these kiosks has increased revenues (Hafner and Limbachia, 2018[128]; Garber, 2014[129]). Users tend to spend more time considering their options when using an automated kiosk, which can result in selecting more items for purchase (Houser, 2018[130]). Similarly, increased revenues may result because users are more likely to customise their orders, which typically carries an additional fee. Academic work also finds that online ordering resulted in 14% more customisation requests than orders made in person (Goldfarb et al., 2015[131]).

Other firms have experimented with the use of ordering by mobile application prior to almost immediate pick-up from the store. McDonald’s, for example, has plans to further enable ordering and payment by mobile application, while Starbucks allows consumers to “skip the queue” by purchasing via application and picking up in store. Some reports suggest that orders made through mobile application can be up to 20% higher than other orders (Wong, 2015[132]).

An emerging and innovative example of embedding online ordering mechanisms within brick-and-mortar stores is the partially automated grocery store pioneered by Amazon (Amazon, 2018[133]). A mobile application facilitates entry into the store, after which point consumers can simply select the products they wish to buy, and then immediately leave the store without a formal checkout process. The aim of their business model is to increase the efficiency of the shopping experience by partially automating the payment process.

The partially automated grocery store, known as Amazon Go, uses geo-fencing technology, embedded sensors, computer vision, infrared detection and deep learning to automatically detect when consumers take products from shelves. Purchase and payment is undertaken automatically through the digital wallet associated with the customer’s Amazon account (see section on innovative payment mechanisms below). The process is more efficient and convenient than other grocery stores (McFarland, 2018[134]), and removes frictions from the typical brick-and-mortar grocery experience by partially automating the payment process. Notably, the goods and services for sale are mostly pre-packaged (e.g. sandwiches), with few items with significant variation in quality like fresh produce. Alibaba and major online firm Tencent have also developed unmanned convenience stores that use quick response (QR) codes for entry and purchase (Soo, 2017[135]; Zhang, 2018[136]), while other automated stores in Korea have experimented with palm vein scanning for custom verification (Chang-won, 2018[137]).

On the intensive margin, the Internet of Things and connected devices have been used as mechanisms for digital marketing to boost sales within physical stores. Digital advertising via mobile phones can be used to provide shoppers with discounts based on proximity, providing personalised offers (Grewal et al., 2016[108]). For example, Coca Cola has developed new forms of digitally-interactive marketing that uses browsing history, IP address, approximate age and gender to develop custom advertising and discounts to consumers inside some American supermarkets (Darrow, 2017[138]).

Innovative payment mechanisms