copy the linklink copied!Chapter 5. SME and entrepreneurship programmes in Ireland

This chapter examines recently completed, on-going, and planned Government SME and entrepreneurship programmes at national level by thematic area of policy intervention. Each section describes and assesses the main programmes. It focuses on a number of key issues including the ‘take up’ of the programmes by target firms and how well the programmes address the key policy challenges for SME and entrepreneurship in Ireland identified in this report (e.g. increasing productivity, increasing business dynamism, diversification of export markets, etc.). The Chapter concludes with a set of policy recommendations.

copy the linklink copied!Financing programmes

Credit Guarantee Scheme (CGS)

Ireland’s Credit Guarantee Scheme was launched in October 2012 and provided a 75% guarantee to banks against losses on loans to eligible SMEs with a value ranging between EUR 10 000 and EUR 1 million. It thus aimed to facilitate lending to SMEs with a viable business model but inadequate collateral. SMEs making use of the CGS were requested to pay a maximum premium of 2% per annum to the Department of Business, Enterprise and Innovation (DBEI). Up to the end of Q1 2019, 669 facilities have been sanctioned for a total value of EUR 107 million.

In March 2017, following a review of the scheme, an updated Credit Guarantee Scheme was established. The main differences with the previous scheme are:

-

An increase in the level of risk the State will take to 80% of individual loans;

-

An extension of the scope to cover other financial product providers, like lessors, invoice discounters etc.; and

-

An extension of the definition of loan agreements to include non-credit products and overdrafts.

Surveys among beneficiaries report that insufficient collateral represents the most important reason for using the credit guarantee, rather than securing a credit facility through the traditional commercial lending route (with 444 out of 487 respondents stating this as their primary reason). Around two-thirds of all CGS facilities were for working capital needs (SBCI, 2018).

Comparisons with other CGSs around Europe indicate that the Irish scheme is modest in size and outreach. In Flanders for example, a region of around 6.5 million inhabitants, slightly more than EUR 300 million in guarantees were disbursed in 2017 alone. In Denmark and Finland, countries with a population somewhat above Ireland’s, the corresponding 2017 number is around EUR 185 million (DKK 1.377 billion) and EUR 560 million respectively (OECD, 2019). The relatively low take-up of the CGS in Ireland is surprising given the high collateral requirements imposed by financial institutions and the lingering difficulties of small firms to access finance compared to most other EU28 countries. This might possibly be related to insufficient awareness of the existence and benefits of the credit guarantee scheme among potential beneficiaries.

The CGS in Ireland has not been subject to an impact evaluation, which would shed light on the reasons behind the relatively low take-up of its activities as well as on its economic impact and additionality. A recent survey conducted by the European Commission and the OECD indicates that such schemes are commonly evaluated, albeit with large variations in frequency and evaluation methods (Schich et al., 2017). Ireland could conduct an evaluation of its revised credit guarantee scheme, and consider further additional revisions to increase the take-up.

Local Enterprise Office (LEO) grants

Local Enterprise Offices (LEOs) can offer direct financial grants to micro-firms (10 employees or fewer) in the manufacturing and internationally traded services sectors. The latter requirement is there to ensure that financially supported firms have a potential to develop into indigenous export firms, which is in accordance with Enterprise Ireland’s (EI) overall mission.1

There are three main categories of grants under which direct financial assistance is provided:

-

Feasibility Grants (investigating the potential of a business idea);

-

Priming Grants (to part-fund a start-up);

-

Business Development Grants for existing businesses that want to expand.

There is also a Technical Assistance Grant available for eligible micro-exporters who are seeking to explore alternative markets for their product or service. The most recent impact report shows that LEOs in 2017 approved financial grants to a total value of EUR 16.6 million for 1 131 applications. The vast majority (> 80 %) were attributed to grants for business development and feasibility.2

Strategic Banking Corporation of Ireland (SBCI)

The SBCI, a state-owned bank, began operations in March 2015. It does not provide financing directly to SMEs, but provides funding at relatively low rates to financial institutions that in turn allocate funds to SMEs. It works with seven on-lending partners, three bank and four non-bank institutions, and has a funding capacity of more than 1 EUR billion. At the end of 2017, the SBCI had lent EUR 920 million to 22 962 SMEs. EUR 391 million of loans were drawn by Irish SMEs with an average loan size of EUR 37 300 in 2017, with 80% of loans for investment purposes. The SBCI has also continued to provide low cost liquidity to a number of non-bank lenders providing a range of products (leasing, hire purchase and invoice discounting).

The SBCI launched the Brexit Loan Scheme together with the Department of Finance, DBEI and the Department of Agriculture, Food and the Marine at the end of March 2018. The scheme provides 1-3 year term loans of between EUR 25 000 and EUR 1.5 million to eligible enterprises, at a maximum interest rate of 4%. Loans of up to EUR 500 000 can be underwritten without any collateral requirements and the scheme is budgeted at EUR 300 million. It is supported by EIB Group’s InnovFin SME Guarantee Facility.

The scheme has been available from 28th March 2018 and is planned to remain open until 28th March 2020. It aims to address the need for relatively short-term credit to face working capital challenges brought about by Brexit and is therefore only available for firms up to 499 employees that can prove to be impacted by the decision of the United Kingdom to leave the European Union (and complies to the InnovFin conditions which among others, excludes firms operating in primary sectors such as agriculture). The scheme mostly supports firms with export activities to the United Kingdom.

A new Future Growth Loan Scheme announced in Budget 2019, jointly funded by the DBEI and the Department of Agriculture, Food and the Marine provides a longer-term scheme facility of up to EUR 300 million to support capital investment by business. The scheme is delivered by SBCI at competitively priced rates with better terms and conditions than currently offered in the marketplace (e.g. no security is required for loans up to EUR 500 000) and offers loan terms of 8 to 10 years. This scheme includes the primary agriculture and seafood sectors.

Microenterprise Loan Fund Scheme

The Microenterprise Loan Fund, managed by Microfinance Ireland, was set up under the Action Plan for Jobs to support economic development and to increase employment and enterprise. This is achieved through the provision of unsecured business loans of EUR 2 000 to EUR 25 000 for commercially viable proposals to micro-enterprises that cannot get funding through normal commercial channels, for working capital, equipment, start-up costs, or marketing purposes. The loan term is typically 3 years for working capital purposes and can be extended to 5 years for capital expenditures. Interest rates range from a fixed rate Annual Percentage Rate (APR) of 7.8% for direct applicants to a fixed rate APR of 6.8% for applicants through the LEO Network, Local Development Companies and banks. Between October 2012 and the end of March 2019, the Fund received 4 724 applications and approved 2 065 loans to micro-enterprises for a total value of EUR 30 million, supporting 5 028 jobs. This fund is the only direct lender to indigenous microenterprises unable to source bank lending that is active in Ireland.

In an internal DBEI Review published in March 2015, Microfinance Ireland was reviewed as moderately successful in its first two years of operation. The lower than anticipated demand for microfinance represented a weakness, in particular in some counties (Department of Jobs, Enterprise and Innovation, 2015).. Since then, the demand for its services has increased significantly with applications volumes doubling since 2014. The Fund is now receiving in excess of 1 000 applications per year and since 2014 has achieved and beaten the job target of 770 jobs per year. Applications up to September 2018 were 18% ahead of 2017 (Microfinance Ireland, 2018).

Microenterprises generally make less use of external financing instruments than their larger peers, likely reflecting the more difficult access (Kraemer-Eis et al., 2018). In Europe, the number of microfinance loans has expanded by 20% between 2015 and 2017 and volumes by 32% over the same period (European Microfinance Network, 2018). The more successful schemes in Europe appear to have a significant impact on entrepreneurship, economic growth and social inclusion. One crucial characteristic for success appears to be the availability of non-financial support such as coaching and mentoring to their beneficiaries (see Box 5.1 for the experience in France and the Netherlands). The Microfinance Loan Fund compares favourably in its reach to Qredits, a similar scheme in the Netherlands, when equalised for population size, time in existence and loan size.

A key focus of the Fund is financially vulnerable sectors such as the unemployed, females, older adults, youth and migrants. As of September 2018, 23% of loans were for beneficiaries of the “Back to Work Enterprise Allowance”, of which 26% were women and 19% non-Irish passport holders.

Qredits in the Netherlands was founded in 2009 as a private foundation by a group of public and private partners. The idea behind Qredits is that it provides support to all groups in society that have an interest in entrepreneurship, have a viable business plan, but are not able to obtain loans otherwise.

In 2016 Qredits issued over EUR 42 million in business loans benefitting 1 750 entrepreneurs, 27% more than in 2015. 1 490 of these loans were micro-loans, up to EUR 50 000, which is twice the ceiling in Ireland. In addition, Qredits also provided 105 loans between EUR 50 000 and EUR 250 000. 155 received a flexible credit for a total of EUR 2 million. This working capital product has a EUR 25 000 limit and can be accessed and paid back as needed.

Apart from providing loans, Qredits also provides mentoring and business development tools for micro-entrepreneurs. Although non- finance activities have always been a part of Qredits’ portfolio, they have expanded strongly in recent years and almost half of all beneficiaries received coaching in 2014.

76% of surveyed entrepreneurs who benefited from micro-finance under the Qredit programme declared that they would have been unable to start their business in the absence of the programme. 42% of the beneficiaries of the Qredits stated that access to finance still represented the most important barrier to them to set up a business (Ibrahimovic and can Teeffelen, 2016). Both numbers suggest a considerable additionality of the micro-finance scheme in the Netherlands.

A counterfactual study conducted in 2016 came to the conclusion that the scheme had achieved the intended impact, providing finance mostly to SMEs that are deemed too risky to be served by regular financial institutions, but were generally as successful as firms in a control group (Kerste et al., 2016a).

ADIE (Association Pour le Droit à l´Initiative Economique) was established in France in 1989. It provides the following support measures:

-

Loans up to EUR 10 000;

-

"Start-up grants" funded by the French government or by local authorities;

-

Subordinated loans bearing no interest rates;

-

Micro-insurance schemes to protect micro-entrepreneurs and their business;

-

Microfranchising;

-

One on one business development services such as coaching, business planning, advice regarding administrative and legal procedures and so on.

In 2016, an evaluation by KPMG, an accounting firm, was released. It illustrated that for every one euro that was invested by tax payers, there was a collective return on investment of EUR 2.38 on average after two years of investment, both because of a decrease of welfare spending (like the revenu de solidarité active (RSA), providing a minimum income for unemployed and underemployed people or the solidarité spécifique (ASS) for unemployed people who do not qualify for the RSA) and because of increased contributions to social security (KPMG, 2017).

In Ireland, Microfinance Ireland provides mentoring support to its successful applicants. These services are paid for by Microfinance Ireland and provided through the LEO Mentor Panel. These supports consist of up to five mentoring sessions for start-up businesses and up to three for established enterprises.

Schemes to develop risk capital for innovative Irish firms

Development Capital Scheme

The Development Capital Scheme is designed to address the funding gap for mid-sized, high-growth, indigenous companies that have significant prospects for job and export growth. Through this scheme, Enterprise Ireland co-invests on a pari passu basis and with the same commercial terms as privately run and managed Funds, i.e. MML Capital Ireland, BDO Development Capital Fund and Cardinal Carlyle Ireland Fund. A total of EUR 225 million in funding is available, typically investing between EUR 2 to EUR 10 million in equity, quasi equity and/or debt.

Innovation Fund Ireland

Innovation Fund Ireland aims to attract global venture capital firms and experienced investment managers to Ireland to invest in innovative SMEs. It is managed by Enterprise Ireland and the Ireland Strategic Investment Fund (ISIF), which both invest EUR 125 million in the Fund. Approximately EUR 80 million has been committed to four funds which are actively investing and have completed their investment cycle. These funds are Sofinnova Ventures, Arch Venture Partners, Highland Capital Partners Europe and Lightstone Ventures.

Enterprise Ireland Seed and Venture Capital Scheme

The Seed and Venture Capital Scheme has been in operation since 1994 and was established to increase the availability of risk capital for SMEs. Since 1994 there have been four multi-annual programmes under the scheme. The government, through Enterprise Ireland has made a further EUR 175 million available for a fifth multi-annual programme (2019-2024) to stimulate job creation and support the funding requirements of young innovative Irish companies. All funds are independently managed by private sector fund managers who make the decisions regarding investments. To date, EI has committed more than EUR 510 million, which, using a co-investment model, has raised a total of EUR 1.19 billion in Seed and Venture capital funding.

Ireland Strategic Investment Fund (ISIF)

The Ireland Strategic Investment Fund, managed and controlled by the National Treasury Management Agency (NTMA), is a EUR 8.9 billion sovereign development fund with the mandate to stimulate economic activity and employment in Ireland on a commercial basis. ISIF absorbed the EUR 7.1 billion Discretionary Portfolio of the National Pensions Reserve Fund on December 2014. To ensure the efficient delivery of funds, the ISIF targets its investments in private sector entities that interface directly with SMEs. To date, commitments have been made to a number of funds, the details of which are included below (OECD, 2019):

-

SME Equity Fund – Carlyle Cardinal Ireland (CCI); ISIF committed EUR 125 million to this EUR 292 million fund focused on lower mid-market private equity investing;

-

SME Credit Fund – Bluebay; ISIF committed EUR 450 million to the Bluebay SME credit fund focused on lending to large SME and mid-sized companies;

-

DunPort SME Fund; ISIF completed a EUR 95 million commitment in 2018. The fund will provide a mix of Unitranche, Senior and Mezzanine debt to Irish SMEs with ticket sizes of EUR 3 million to EUR 35 million and terms of 3-5 years;

-

BMS Finance Ireland: The EUR 30 million fund provides debt finance to high-growth Irish SMEs for working capital, contract wins, capital expenditure, acquisitions and MBOs;

-

Causeway Capital; a EUR 60 million Dublin-based private equity fund that targets fast-growing small and medium businesses in Ireland and the United Kingdom;

-

Milkflex Fund: Milkflex Fund is a EUR 100 million fund which provides loans of between EUR 25 000 and EUR 300 000 to dairy farmers;

-

Finance Ireland: ISIF invested EUR 30 million in equity in Finance Ireland. whose overall strategic goal is to become Ireland’s leading broad based non-bank lender to the SME sector;

-

Muzinich Pan-European Private Debt Fund: ISIF committed EUR 45 million to the Muzinich Pan-European Private Debt Fund 7 which, in turn, targeted investment of EUR 67.5 million towards Irish SMEs through sub EUR 10 million loans;

-

Finistere Ventures: The Ag-Tech Fund was established with EUR 20 million to invest in technological companies in the food and agriculture sector;

-

Insight Venture Partners: A commitment of USD 100 million in a global investor focused exclusively on growth stage software companies;

-

BGF: An investment fund with EUR 250 million to invest as minority stakes of between 2 EUR million and 10 EUR million;

-

Motive Capital: USD 29.5 million investment in a Fintech specialist private equity investor.

Few sovereign wealth funds around the globe have an explicit mandate to support economic activities and employment (and focus solely on delivering commercial returns), and ISIF thus represents an outlier in this respect. Although precise data are not available, only a small fraction of institutional investor’s funds are directed to small companies, due to regulatory restrictions, the opacity of SME markets, limited scale and exit options (Boschmans and Pissareva, 2017) (World Bank, IMF, OECD, 2015). Given the relative novelty of ISIF’s mandate, it is advisable to closely scrutinise the economic impact and return on investment.

InterTradeIreland Seedcorn

The InterTradeIreland Seedcorn competition mirrors the real life investment process in order to improve participating firms’ ability to attract investors. The competition is aimed at early and new start companies that have a new equity funding requirement and has a total cash prize fund of EUR 280 000.

WDC Investment Fund

WDC Investment Fund is a EUR 50 million Evergreen Risk Capital Fund serving the Western Region covering the counties Clare, Donegal, Galway, Leitrim, Mayo, Roscommon and Sligo. The WDC Investment Fund has a number of targeted sub-funds:

-

WDC Business Investment Fund provides equity investment and loan finance to small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) with first round investments ranging from EUR 100 000 to EUR 1 million. The WDC’s Business Investment Fund invests across all sectors, including Lifesciences and MedTech, ICT, CleanTech, Creative Industries, Marine and Natural Resources, Food and Tourism.

-

The Western Regional Audio-visual Producers (WRAP) Fund is a EUR 2 million regional fund for the audio-visual sector. It provides funding of up to EUR 200 000 for feature films, television dramas, animation and games that undertake a significant portion of their production in the WRAP area, which covers counties Clare, Donegal, Galway, Mayo, Roscommon and Sligo, and up to EUR 15 000 by way of loan for the development of feature films, television dramas, animation and games at any stage from treatment to pre-production. It is a joint initiative with Galway Film Centre and is supported by the local authorities of Clare, Donegal, Galway, Mayo, Roscommon and Sligo and Udaras na Gaeltachta.

-

WDC Micro-Loan Fund for Creative Industries provides micro-loans of up to EUR 25 000 on an unsecured basis to micro-enterprises in the creative industry sector.

-

WDC Community Loan Fund provides loan finance to community and social enterprises at a low interest rate. The WDC Community Loan Fund also provides bridging finance to facilitate community and social enterprises drawdown approved grant-aid.

copy the linklink copied!Innovation programmes

Overall innovation framework

The DBEI, along with the Department of Education and Skills (DES), is responsible for leading National Strategic Outcome 5 – A Strong Economy Supported by Enterprise, Innovation and Skills (NSO5). In June 2018, it published an investment overview which summarises the strategic investment priorities (with a foreseen capital funding of EUR 3.16 billion to 2022 and a planned total allocation of EUR 9.4 billion to 2027), which will deliver the NSO over the period 2018-27. The Strategic Investment Priorities (see page 11 of DBEI, 2018) include investments in line with the Innovation 2020 strategy (see below) as well as new initiatives such as regional ‘Technology and Innovation Poles’ (TIPs) and regional sectoral clusters (see Chapter on the local dimension).

The Innovation 2020 strategy, adopted in 2015, is an overarching policy framework for research and innovation and is a “whole government strategy” covering the implementation of 140 actions by Enterprise Ireland (EI), Science Foundation Ireland (SFI), the Local Enterprise Offices (LEOs) and a number of other departments and agencies. Innovation also is given a prominent place in the annually updated Action Plan for Jobs (Irish Government, 2018).

Innovation 2020 aims to increase gross expenditure on R&D (GERD) to 2.5% of GNP, a significant increase on the 2014 rate (1.5%), notably by the business sector investing more in R&D. A related target is to increase the number of research personnel in enterprises by 60% to 40 000. Both these targets appear ambitious, despite a gradual growth in absolute levels of business expenditure on R&D (BERD) from 2013 to 2015 (CSO, 2018), since faster GNP growth has resulted in lower GERD and BERD intensities. A third target to increase the number of “significant business R&D performers” (spending between EUR 100 000 and EUR 1 999 999) to 1 200 enterprises is challenging (the number was 918 in 2017).

Tax incentives for business R&D and innovation

R&D tax credit

An R&D tax credit was first introduced in 2004 in Ireland and has undergone several changes since then. The most significant change was in 2015, when Ireland’s tax credit became entirely volume-based, which led to a significant increase in the implied marginal tax subsidy rates for SMEs and large firms in both profit and loss scenarios (OECD, 2018). A payable element to the R&D tax credit was introduced in 2009, which is useful for smaller loss-making firms in the development phase and beyond. The payable element is limited by reference to the company’s corporation tax or payroll tax liabilities. Moreover, expenditure on activity outsourced to third level institutes is restricted to the greater of 5% of overall spend or EUR 100 000. Likewise, expenditure on activity outsourced to third party subcontractors is restricted to the greater of 15% of overall spend or EUR 100 000. These restrictions are also subject to ‘matched’ internal expenditure requirements, which can also be a barrier (a firm can only claim EUR 100 000 of outsourced expenditure, for example, if it has spent the same amount internally). A provision was also introduced to make it possible to carry forward unused credits (for three years), again useful for smaller loss-making firms in the development phase. However, upper ceilings apply to the amount of subcontracted R&D that can be claimed through tax credits. Under the R&D tax credit, companies can receive a credit of 25% of qualifying expenditure. This expenditure is also a deductible cost for corporation tax purposes. In practice, companies undertaking qualifying R&D can thus claim a refund from the Revenue of EUR 37.50 for every EUR 100 worth of R&D expenditure.

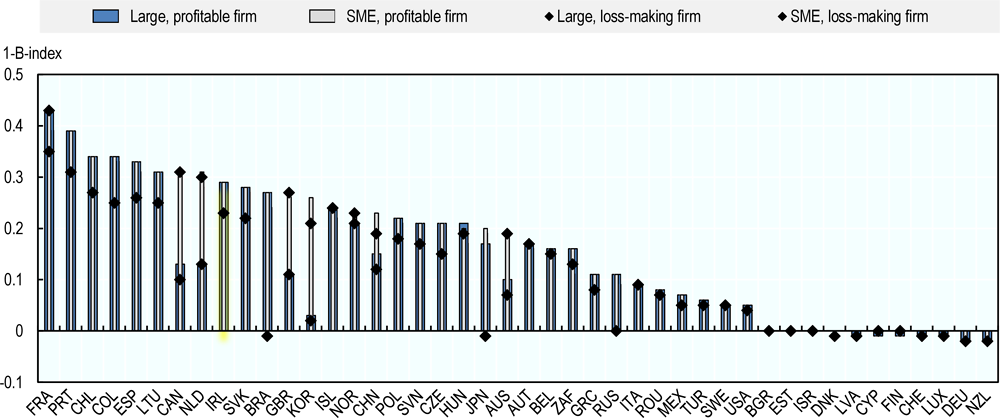

In 2017, Ireland had the highest share of tax incentives financing BERD (0.29% of GDP) and the sixth most generous R&D tax subsidy rate of the OECD and other selected countries (Figure 5.1).

The above data indicate that the current R&D support is already quite generous in an international perspective. The Irish Government may therefore consider optimising current schemes, for example by ensuring smaller companies have easier access to government support in this area, rather than further raising expenditures.

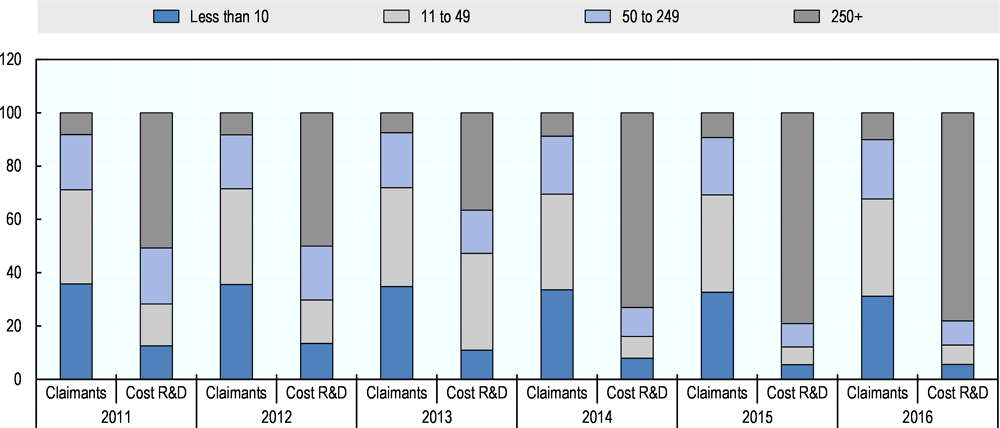

In particular, the distribution of the R&D tax subsidy to firms by size is heavily skewed to larger firms. Firms with more than 250 employees accounted for 10% of claims but 78% of the cost of the R&D tax credit in 2016. Similarly, the Large Case Division (LCD) of the Irish Revenue service handled 12% of claims but “LCD firms” (the largest corporate taxpayers) accounted for 70% of the cost of the R&D tax credit in 2017. While the statistics do not distinguish between indigenous and foreign-owned firms, these data suggest that MNEs are the main beneficiaries of the R&D tax credit. Two main reasons for the limited claims by smaller companies are:

-

The cost of preparing, filing and defending a claim is too high. The criteria for making claims, recording and justifying claims and so on as laid down by Revenue are onerous for SMEs – the rules appear to have been designed with large established R&D intensive (e.g. pharmaceutical) companies in mind, where development processes are very detailed and structured. In contrast, the rules are not a good fit with, for example, new, agile software development companies, where processes are fluid and fast and documentation is less necessary.

-

The risk of Revenue making a clawback of a claim, going back up to 4 years, can put SMEs off. Revenue data shows that revenue audits on R&D claims are both frequent and high yielding in terms of clawbacks of claims. SMEs may find it hard to carry a potential clawback liability and may see the risk as too high.

As noted above, efforts have been made to simplify the R&D tax credit and make it attractive to smaller (indigenous) firms. However, the data suggest that larger firms are increasingly subsidised via the R&D tax credits with a growth of close to 300% in the value of R&D tax credits compared to 14% for SMEs in the period 2011-15 (see Figure 5.2). The increase in the value of R&D credits was particularly significant from 2014 onwards. This could be due to changes to the tax credit regime with the removal of the “base year” and incremental allowable amounts from 1 January 2015.

An empirical study published in 2018 investigated the impact of the R&D tax incentives by firm size as operated in France, Italy, Spain and the United Kingdom over the 2008-2009 period. In these four countries, the positive impact on firm behaviour (measured as the intensity of R&D expenses over sales) was much higher for small enterprises than for large ones. The research suggests that large enterprises, in contrast to SMEs, typically engage in R&D activities in the absence of tax incentives (Sterlacchini and Venturini, 2018). Efforts to make the Irish R&D tax credit more accessible to smaller firms would therefore likely increase its additionality and efficiency. This is especially relevant given significant deadweight of the current scheme. It has been estimated that 40% of the R&D in Ireland benefiting from the incentives would have occurred anyway (Department of Finance, 2016).

A pre-approval process for R&D tax credits would diminish the uncertainty of potentially incurring a clawback and paying penalties and encourage more take-up by SMEs. Another potential improvement is simplified and updated record keeping requirements (a reduction of the four-year period) and clearer guidance on the eligibility criteria.

In addition, with a view to increasing co-operation among businesses and with higher education, the limits on outsourcing R&D work to third parties or universities should be reviewed. This discourages collaboration and is likely to disproportionately affect SMEs as, with fewer resources, a collaborative approach may be the only way for an SME to progress.

Further, if a company does not have a tax liability in the current or immediate prior period, it can claim a repayment in cash of R&D tax credits in three equal instalments over a three-year cycle. In comparison, in the United Kingdom, SMEs can obtain refunds immediately after filing their corporation tax return. This is particularly significant for SMEs, which are more likely to be unprofitable at the R&D stage.

To provide a point of comparison, learning elements from Norway’s Skattefunn scheme, identified as a successful R&D tax credit scheme by a 2014 European Commission study are summarised in Box 5.2.3

Description of the approach

Norway introduced the SkatteFUNN refundable R&D tax credit for SMEs in 2002 as a volume based tax credit with a headline rate of 20% (which has remained stable since introduction) for SMEs. Where there is insufficient tax liability, firms receive a refund of unused credits in the following year. A ceiling of NOK 25 million applies to in-house R&D (inclusive of R&D procured from entities other than approved R&D institutions) and NOK 50 million to purchased (subcontracted) R&D when purchased from approved R&D institutions. The caps on eligible costs are applicable for each individual company, meaning that if a holding company has three subsidiaries, each of the three companies may benefit from SkatteFUNN up to the cap for each company.

The tax incentive is based on R&D projects, which are approved by the Research Council of Norway within the same calendar year as the application has been filed. In practice, this procedure is an ex-ante appraisal of whether or not a project qualifies as R&D or not. In 2017, more than 7 600 projects received support under the SkatteFUNN tax deduction scheme, a 10 per cent increase from the year before. The total cost for eligible R&D projects amounted to nearly NOK 31 billion, leading to tax deductions of just over NOK 5.5 billion. The scheme is considered to be well-suited for SMEs and an important instrument for restructuring industry and boosting trade.

Factors of success

The SkatteFUNN R&D tax incentive has been evaluated several times and was found to be effective in stimulating private R&D investments. Firms that previously invested less than the cap increased their R&D more than firms that previously invested above the cap. Firms that previously did not invest in R&D were more likely to invest. Additionality effects were found to be strongest in small, low tech and low-skilled firms.

A key factor of success is the simple application process (the application form was further simplified in 2018) to apply for a deduction. The application procedure is based on a self-declaration and advice and guidance is provided throughout the application. Moreover, the Research Council of Norway, which administers the scheme, has a policy of pro-active communication with potential applicants and of educating auditors and accountants. This has resulted in a sustained year-on-year increase in applications since 2011, with almost 50% of companies applying having less than 10 employees and more than 80% with less than 50 employees. Approximately 20% of the SkatteFUNN beneficiaries each year are new and slightly less than half have no prior experience in R&D (Benedictow et al, 2018).

The 2018 evaluation found that SkatteFUNN significantly increases recipient’s investments in R&D so that for every NOK 1 of tax credit, R&D expenditure increases by more than NOK 2. Positive effects were found on increasing innovation in terms of new products and processes as well as on labour productivity. The evaluation concluded that SkatteFUNN is better suited to enhancing smaller R&D projects (in smaller firms) than other R&D grant based instruments.

Obstacles and responses

While, the SkatteFUNN scheme does not stipulate any particular obligations with regards to inter-company collaboration, a company may choose to carry out the project using internal resources or to collaborate with other companies or external R&D institutions, applying the double cap for eligible costs when sub-contracting. If more than one company is involved in an R&D project, each company is required to submit a separate SkatteFUNN application, listing its share of specific R&D activities in the project.

However, both the 2016 and 2018 evaluations have not found a strong impact on co-operation with universities, colleges and research institutes. The 2018 evaluation noted that the number of collaborative projects with R&D institutions had remained stable over 10 years, and that despite the fact that collaborative SkatteFUNN projects had increased in both duration and total budget since 2009, this is not due to the share of extramural R&D rising. The evaluation concluded that despite the specific increases in the cost cap for extramural R&D, this has not stimulated additional collaboration (yet). This led the evaluators to recommend increasing the tax credit rate to 25% for intensive collaboration (defined as projects that spend at least half the budget on purchased R&D).

Relevance for Ireland

SkatteFUNN’s ex-ante evaluation (pre-approval) process is of relevance to the Irish case as it provides a high-degree of certainty, notably to smaller firms, about the eligibility of the planned expenditure. Combined with advice to smaller firms from institutions such as Enterprise Ireland, LEOs or Technology Gateways, it can help them define a feasible R&D project, and leverage additional uptake (and volume of credits) of the R&D tax credit by Irish SMEs.

The SkatteFUNN provision that allows doubling of the maximum eligible costs in case of sub-contracting to a research institute could also be a means of enhancing R&D efforts by smaller Irish firm while strengthening co-operation within the Irish innovation system. Increasing the R&D tax credit rate for intensive collaboration while reducing the rate for non-collaborative R&D could generate a significant behavioural additionality in the Irish system, boosting co-operation between larger (foreign-owned) and smaller (Irish-owned) firms as well as between both types of firms and the Irish research and technology infrastructures and centres.

For further information: www.skattefunn.no.

The Knowledge Development Box (KDB)

The Knowledge Development Box (KDB) initiative, a complementary measure, was introduced in 2016, and provides for a preferential tax rate on income from qualifying intellectual property (IP) resulting from R&D carried out in Ireland. Additional legislation was passed in 2017 which aimed to make the scheme more accessible to SMEs by allowing the exploitation of certain non-patented assets to qualify for relief. Under the scheme, firms can apply to the Controller of Patents, Designs and Trade Marks for a certificate when they believe that their IP generated as a result of R&D is novel, non-obvious and useful. If the certificate is granted, the SME will be entitled to a deduction equal to 50% of its qualifying profits in computing the profits of its specified trade, resulting in an effective tax rate of 6.25% on profits arising from the IP assets. Restrictions on outsourcing are less stringent than those under the R&D tax credit regime and since the share of the profits from IP that can be claimed depends on the share of R&D undertaken in Ireland, this would potentially benefit SMEs more than MNEs (the latter are more likely to develop IP based on research done partly elsewhere than in Ireland). However, in April 2018, fewer than 10 taxpayers had claimed tax relief under the KDB scheme, suggesting that it may not be proving easy for firms to use this new tax relief. The eligibility and administration procedures could be further examined as well as awareness of the scheme.

Direct support to incentivise domestic owned firms to innovate

At the national level, direct innovation support is delivered mainly by Enterprise Ireland (EI). EI targets three types of firms: high-potential start-ups (HPSU), established SMEs, and large companies (over 250 employees). The latter are eligible for R&D funding and business innovation funding under the De Minimis State Aid rules from the European Union (EU), which allows small amounts of aid unlikely to distort competition.

The 2017-20 EI strategy aims to “support more Irish companies to achieve greater scale and expand into new export markets”. This includes EI support for innovation with the aim to increase business R&D spend by 50%, reach a target of EUR 1.25 billion per annum by 2020, increase the level of innovation and entrepreneurship across Irish regions and improve connections between EI client firms and “international innovation ecosystems”. To reach these objectives EI foresaw, amongst other measures, introducing new innovation supports broadening the scope of direct in-company research, development and innovation (RDI) support to new sectors and further boosting innovation-led pre-commercial procurement (see section on procurement).

EI direct support schemes

In Ireland, “HPSU” (defined as start-up businesses with the potential to develop an innovative product or service for sale on international markets and to create 10 jobs or more and EUR 1 million in sales within 3-4 years of starting) are supported through the dedicated EI HPSU programme. In 2017, 90 new HSPUs were approved, the focus of HPSU being predominantly in the ICT sector. In practice, the HPSU scheme involves EI pre-screening the business case of applicant entrepreneurs and, when an entrepreneur or existing start-up is deemed eligible, the HPSU is then provided with advice on funding and other support from an EI Development Advisor. Firms that do not qualify are either encouraged to further develop their business case by following a start-up development programme or redirected towards a LEO for funding and support. Entrepreneurs managing HPSU or other tech-based start-up firms can also avail of the R&D tax credits and business innovation funding and support programmes, as well as various entrepreneurship education and training initiatives discussed below.

Increasing the engagement of SMEs in RD&I is facilitated by a suite of EI measures. The core elements of EI direct support to firms for RD&I include:

-

Innovation vouchers providing funding to assist a company explore a business opportunity or problem with a registered knowledge provider. Two types of vouchers are offered: Standard EUR 5 000 vouchers can be applied for during regular open calls; and Co-funded Fast Track Applications where the value of the voucher is EUR 5 000 and the company contributes 50% of the project costs in cash (hence total budget of maximum EUR 10 000). In 2017, 557 innovation vouchers were redeemed to solve small business problems (EI Annual Report 2017);

-

The Exploring Innovation grant aims to support better planning of R&D, Innovation or International Collaboration projects. The maximum grant for these feasibility study projects is EUR 35 000 (50% of eligible costs). The outputs should include a project plan that may form the basis of an application for R&D or other funding from EI. Hence, it acts as a pipeline for other EI funding schemes.

-

The RD&I fund supports firms in manufacturing or internationally traded services (not HPSU firms unless they have sustainable revenues of EUR 500 000). Two types of projects can be funded: R&D projects involving the resolution of technical challenges in order to develop new products, processes or services; and business innovation projects involving the implementation of a new services delivery or a new production method or a substantive change to the business model of the company. Maximum grants for R&D Projects are EUR 650 000 (although larger projects can be supported by EI on a case-by-case basis) and for Business Innovation Projects EUR 150 000 (with variable shares of project costs eligible in line with EU State Aid rules). A collaboration bonus of up to 15% is available for R&D projects where there is collaboration between two companies, but the total maximum funding cannot exceed 50% of the total project cost. In 2017, there were 99 R&D grant approvals in excess of EUR 100 000. According to EI’s Annual Report for 2017, 146 companies were engaged in substantial R&D projects of above EUR 1 million spend per annum and 982 client companies were engaged in significant R&D expenditure of above EUR 100 000 per annum. EI’s Key Manager Programme also offers a grant that can cover salary for innovation projects and recruit “innovation managers” who can be incorporated into an R&D Fund proposal.

-

The Innovation Partnerships can provide up to 80% of the cost of research work to develop new and improved products, processes or services, or generate new knowledge and know-how. The Programme encourages Ireland-based companies to work with Irish research institutes, resulting in companies accessing expertise and the research centre benefiting in terms of developing skill sets, intellectual property and publications. The application to EI is managed by the Principal Investigator in the participating research institute. All Innovation Partnerships projects require the company partner to provide minimum cash contribution of 20% of the total project cost. The average of EI funding per project is EUR 220 000 with some projects thus receiving significantly higher funding. In 2017, a record 85 innovation partnerships were approved, 36 of which were between EI client companies and higher education institutes (EI Annual Report 2017).

In November 2017 the new Agile Innovation Fund was launched to help companies commercialise innovations rapidly in (international) markets. The Fund gives companies rapid access to funding for innovation and to respond to changing market opportunities and challenges (such as those posed by Brexit). The Fund aims to support companies in sectors with rapid design cycles to maintain their technology position. The Fund is managed on a fast-track approval procedure and a streamlined online application process and companies can access up to 50% funding to support product, process or service development projects with a total cost of up to EUR 300 000.

In addition, EI has developed an Innovation 4 Growth programme which provides tailored executive education to managing directors and their top teams in Irish businesses. The programme is delivered by the Irish Management Institute in partnership with MIT Sloan School of Management in Cambridge, Massachusetts. The programme is designed around five modules and aims to develop increased innovation management skills and growth.

Direct support schemes from InterTradeIreland

InterTradeIreland runs the Challenge Programme which provides SMEs with a sustainable and repeatable process for managing innovation. Through workshops and coaching over a nine-month period, proven tools and techniques to help companies create, evaluate and commercialise new ideas are embedded in the company. Over 100 SMEs have benefitted from this coaching since the first programme in 2011. In addition, InterTradeIreland runs the All Island Innovation Programme, which aims to promote and encourage innovation across the Island. A series of innovation lectures, seminars and masterclasses are held throughout the year to share international best practice in areas of innovation. The events, which take place in Belfast, Dublin, Galway and Cork each year, are attended by over 1 000 business leaders, policy makers, students and academics from across the Island.

InterTradeIreland helps companies and researchers from Ireland and Northern Ireland to collaborate in Horizon 2020, the European Commission's seven year, EUR 80 billion, Research and Innovation programme designed to boost jobs and growth across Europe. The exchange of information, contacts and knowledge through the steering group and the relationships brokered and facilitated by InterTradeIreland is the most important element in achieving a step change in cross-border research cooperation. The total drawdown to March 2017 for collaborative North-South applications from Horizon 2020 is EUR 63.46 million. The programme aims to achieve its objectives by engaging industry, so that scientific ideas can be turned into viable products and services. Since 2014 InterTradeIreland has offered Cross Border and EU travel vouchers to 64 SMEs.

Attracting foreign-owned R&D and innovation-intensive high growth firms

The government’s investment, via SFI and EI, in a range of research and technology centres (discussed below) is a key element of a strategy to attract more knowledge- and innovation-intensive FDI and to connect these investments with indigenous firms and the Irish research base. IDA Ireland, the Irish foreign direct investment (FDI) agency, also provides a number of grants to support both large and “small multinational companies” (in partnership with EI) as well as IDA managed grants for: Innovation Vouchers; Research, Development and Innovation (RD&I) Feasibility Studies; and in-house R&D.

The small multinational company category seems to be synonymous with the IDA targeting of high-growth companies that are “typically operating less than seven years and have a turnover between USD 30 million – USD 70 million.” Since 2010, over 100 high growth global companies have established their operations in Ireland. In 2017, IDA Ireland reported 50 RD&I projects and investment in these projects of EUR 905 million. In 2016, IDA reported that the total R&D in-house expenditure of domestically hosted MNEs was EUR 1.64 billion. This compares to a target of winning a cumulative EUR 3 billion in new R&D expenditure and to encourage 120 additional companies to engage in R&D across the FDI portfolio (IDA Strategy).

Policy programmes supporting collaborative R&D and innovation

Collaboration, between enterprises (including MNEs) and between enterprises and the research base, in the Irish innovation system is fostered via investment in research and technology infrastructures, managed principally by EI and Science Foundation Ireland (SFI), in partnership with the IDA for certain programmes. These centres are complemented by a number of funding programmes such as SFI Industry Fellowships, Knowledge Transfer Ireland (KTI) and InterTradeIreland’s Fusion programme (which helps firms recruit a high calibre science, engineering or technology graduate in partnership with a third level education institution).

As part of Innovation 2020, the national research prioritisation exercise (RPE) (considered as Ireland’s response to the EU’s requirement to present a ‘Smart Specialisation Strategy’) has identified 14 priority areas (after a process of consultation with stakeholders, including industry) for targeting competitively awarded research investment and funding within six broad enterprise themes (ICT, health and wellbeing, food, energy, climate change and sustainability, manufacturing and materials as well as services and business processes).

A number of research and technology ‘centres’ have been developed and the RPE is used as a guiding framework for further investment. These infrastructures include:

-

SFI funded Research Centres;

-

EI funded network of industry-led Technology Centres; and

-

EI funded Technology Gateways.

The SFI Research Centres focus on applied and basic research combined (ABC), while the EI sponsored Technology Centres and particularly the Technology Gateways work closer to the immediate needs of firms (notably SMEs). While SFI Research Centres undertake fundamental and earlier-stage applied research, they are increasingly working with industry to support embedding and scaling of technology. SFI Research Centres also work extensively with SMEs. Some observers point to an overlap in activities and engagement with industry between SFI Research Centres and EI Technology Centres.

A further programme supporting mobility of researchers into industry is the Marie Curie Career Fit Programme, which addresses skills gaps for innovation in SMEs by sourcing highly experienced international researchers or engineers to work with sectoral challenges facing companies associated with the Enterprise Ireland Technology Centres. It provides an opportunity for experienced researchers to develop their careers in market focused applied research in Ireland’s Technology Centres, with an enterprise secondment between 6 and 12 months during the Fellowship.

Science Foundation Ireland Research Centres and related measures to support collaboration

SFI has funded 17 SFI Research Centres to date, with an investment of EUR 450 million by the government and a further EUR 250 million from industry collaborations (SFI, 2018). They support basic and applied research with strong industry engagement, economic, and societal impact that address critical and emerging areas of the economy. To add to the 12 Centres that existed in 2016, four new Centres were launched in 2017 in the fields of Smart Manufacturing (CONFIRM), additive manufacturing (I-FORM), neurological diseases (FutureNeuro), and the bio economy (BEACON). A 17th research centre in the field of future milk/precision agriculture (VISTAMILK) was launched in 2018 (in partnership with the Department of Agriculture, Food and the Marine). During 2018, SFI completed the review process concerning phase 2 funding for the seven research centres launched in 2012, with 6 of the 7 Research Centres funded for a second 6-year term. Cumulatively the SFI Research Centres have signed more than 750 collaborative research agreements with over 400 industrial partners representing cumulative company commitments of over EUR 180 million (> EUR 90 million in cash) and have won EUR 195 million from EU and international funding agencies (SFI, 2019).

An interim evaluation (covering the first seven centres funded from 2013) of the Research Centres programme (Indecon, 2017) concluded that the research centres had generally outperformed targets when it came to attracting cash funding from industry. Collaborations with industry were split between 45% Irish-owned and 55% foreign-owned firms. Of the firms that participate in Research Centres, one-third were large (>250 employees), and two in five (42%) small (<50 employees). The evaluation, however, emphasised the need to increase the transfer of skills from research centres to enterprises, notably through increasing the number of Master’s graduates (which fell short of target).

The SFI Research Centres Spokes programme is a complementary measure which aims to attract new partners to work with the SFI Research Centres, based on a co-funding requirement (EUR 21 495 000 grant commitment in 2017). The Spokes programme also provides a vehicle to link together, in a meaningful and relevant way, different Research Centres.

SFI also supports co-operation with industry through specific funding programmes, namely: SFI Partnership (grant commitment in 2017 of EUR 6 190 000), TIDA (EUR 4 595 000) and Industry Fellowships (EUR 1 903 000). In total in 2016, 1 603 industry collaborations were supported by SFI awards involving 399 MNEs and 491 SMEs.

The SFI Partnership programme is a flexible programme that enables companies to work with academic researchers through a joint research programme funded 50% by the company (cash) and 50% by SFI. Three awards were made in 2017. The Industry Fellowships Programme supports a post-doctoral researcher or member of staff in an Irish research organisation to go from academia to industry or an industrial researcher to spend time in an academic laboratory (full or part-time for up to 24 months). A maximum grant of EUR 100 000 is available to fund the salary and other costs of the researchers in a company. Since the launch in 2013, 145 SFI industry fellowships have been awarded (SFI, annual review 2017).

The SFI TIDA programme aims to support the commercialisation of research by enabling researchers to focus on the first steps of an applied research project which may have a commercial benefit if further developed (patents, licences or spin-out companies). A 2016 evaluation (Frontline, 2016) concluded that TIDA was an important programme as it plugged a gap in the commercialisation pipeline at the early technology readiness levels. If successful, the TIDA projects can benefit from support from other agencies, such as the EI Commercialisation Fund. This supports researchers in HEIs and research organisations to take research outputs with commercial potential to the stage where they can either be transferred to industry through a license or used to develop a new start-up company. Some observers point to a bridging gap for companies bringing technology to next level, requiring market/customer/technology validation (solving the right problem at the right price for customers) over 1-2 years and requiring funding of between EUR 500 000 and EUR 3 million.

Technology Centres

EI and IDA sponsored Technology Centres have as a mission to introduce companies to the research expertise in Irish higher education institutions with the aim of generating innovative technologies leading to job creation. The Technology Centres are collaborative entities established and led by industry enabling Irish companies and multinationals to work together with qualified researchers associated with the research institutions. Technology Centres are operating in fields such as energy research, composites, dairy processing, data analytics, manufacturing research, etc.

A Technology Centre receives, on average, State funding of the order of EUR 1 million per year over a five-year period. Continued funding depends upon a range of metrics such as increasing industry research funding, growing the numbers of companies involved, licences and the revenue from them and spin-offs, new products and processes leading to increased export sales. At the beginning of 2017, more than 420 companies (165 EI clients, 120 IDA clients and 135 other companies) were benefiting from this industry-led research programme. In total, 785 companies were involved in the Technology Centres programme at the end of 2017, of which 525 held full membership.

Technology Gateways

EI coordinates a national network of 15 Technology Gateways in partnership with 11 Institutes of Technology. It may be argued that the Institutes of Technology level of expertise is better suited to indigenous SMEs in less technologically advanced sectors. The Technology Gateways are expected to deliver technology solutions for Irish industry (all sizes) close to market needs and act as local access points to the resources available in the wider network of Irish research and innovation infrastructures. According to EI, the Gateways have completed more than 2 750 industrial projects since 2013 with a total value in excess of EUR 15 million (of which 46% from industry). In 2017, 436 projects were approved with 462 companies working on 700 projects during the year (EI annual report 2017).

The Gateways’ projects are funded through the direct funding programmes of EI and directly from companies (the funding share from companies is one of the primary metrics for the Gateways) and range from between EUR 5 000 and EUR 10 000 (e.g. innovation voucher type support) to EUR 200 000 (e.g. funded by the Innovation Partnership Programme). To optimise the potential of the network, three sector-specific clusters have been established in engineering, materials and design (six Gateways), applied internet of things (five Gateways) and food and beverage technologies (seven). A new round of the Programme involves a Government investment of EUR 26.75 million over for the period 2018-22.

InterTradeIreland support for collaboration

The FUSION Programme develops and facilitates strategic partnerships. Each project is initiated by a company which has a specific technology need. Through FUSION, the company is matched with a college or university in the opposite cross border jurisdiction that can provide the necessary expertise. A high-calibre graduate is then employed by the company to deliver the agreed project. The graduate acts as the link-agent in transferring and embedding technology and knowledge transfer from the academic into the company. This transfer of knowledge is always on a cross-border basis, with the ultimate aim of increasing overall levels of technological innovation, research and development within the participating enterprises.

FUSION has assisted over 700 partnerships since establishment in 2001. Projects can be supported for 18 months to a maximum of EUR 67 900. These are typically in new product, service or process development. 12 month projects which are typically focussed on process improvement can be supported up to EUR 47 400.

The US-Ireland R&D Partnership is a tri-jurisdictional innovation funding alliance which was officially launched in 2006. Its aim is to promote collaborative innovative research projects which create value above and beyond individual efforts. To date a total of 43 projects have been awarded funding which represents a combined investment value of EUR 67 million. The Centre to Centre funding activity is focussed on supporting industry and academic collaboration on a tri-jurisdictional scale. This element has been particularly successful at attracting the involvement of SMEs.

Disruptive Technologies Innovation Fund

To complement these existing initiatives and to support private investment in emerging and enabling technologies, in 2018 the government announced the launch of a Disruptive Technologies Innovation Fund (DTIF) which will invest EUR 500 million over 10 years. The DTIF is being implemented by the DBEI and its agencies and will seek applications for funding on a competitive bid basis. The projects selected should last up to three years and be large-scale projects in the range of EUR 5 to 10 million total cost, inclusive of enterprise co-funding, and should fit within the research priorities for 2018-23 (for the first phase of funded projects to 2022). Collaboration is an essential requirement (MNEs, research organisations, etc.), as is the participation of at least one SME and the project proposals must demonstrate they will be sufficiently “disruptive” and benefit the Irish economy (all consortium participants must be based in Ireland to receive funding, but non-Irish based organisations may participate). A first call was launched in June 2018 and 27 collaborative projects were successful with over EUR 70 million awarded up to 2021. A second call was launched in June 2019.

Innovation challenges and policy options

Innovation 2020 provides an overall policy framework for boosting the innovation potential of Irish SMEs but the traceability of progress toward objectives and readability of the Irish policy framework is reduced by the multiplicity of closely related and often inter-dependent plans (Action Plans for Jobs, Investing in Business Enterprise and Innovation 2018-2027, STEM education plan, Enterprise 2025, etc.). In addition, agency level strategies, while necessary, further diffuse the link between the stated objectives in terms of enhancing business innovation (and ultimately productivity), the existing (or planned) programmes and actual progress towards these objectives. The current progress reports are more akin to activity reports than a tracking of progress towards objectives. Overall, it would be advisable to develop a more detailed ‘theory of change’ or ‘impact pathway’ that illustrates how government interventions are expected to lead to expected objectives notably in terms of increasing indigenous SME R&D and innovation activity and outcomes.

There is a need to rebalance financial support (notably the R&D tax credits) for R&D and innovation from larger (MNE) firms towards indigenous SMEs. A stronger emphasis (in both R&D tax credits and direct funding) should be given to collaborative (beyond bilateral co-operation) projects involving groups of smaller firms working together on technology adoption as well as product development or process improvement.

It is recommended to review the R&D tax credit with a view to enhancing the share of non-R&D or ‘sporadic’ R&D active SMEs benefiting from the scheme. A 2016 evaluation noted that the “R&D tax credit demonstrates reasonable additionality, but the deadweight indicates that there may be scope to increase the “bang for buck” without materially damaging business incentives to invest in R&D”. An appropriate response would be to adjust the R&D tax credit rates so that ‘intensive collaboration’ is rewarded while a reduced rate for non-collaborative R&D would be applied. It is also recommended to introduce a pre-approval process for R&D projects of SMEs to reduce uncertainty about whether planned R&D will be eligible for a tax credit.

copy the linklink copied!Internationalisation programmes

The Brexit challenge

Internationalisation is viewed as an increasingly critical issue given the uncertainty over the outcome of the UK’s Brexit process. As the United Kingdom is a major export market for many Irish companies, notably smaller indigenous firms which are exporting for the first time, the need to reduce “exposure” to the UK market and drive diversification of Irish exports to new markets has been given high prominence. The evidence available and most informed observers consider that there is a major threat for Brexit in terms of disruption of supply chains and loss of markets – Cross-border Trade with Northern Ireland plays a particularly important role for many Irish SMEs. For over half (51%) of Irish exporters, Northern Ireland is the destination for more than 50% of their exports, while for 26% of Irish firms, Northern Ireland is the destination for approximately 100% of their exports (InterTradeIreland, 2018).

Nevertheless, Brexit may be an opportunity for Ireland. For instance, a survey of the EOY Alumni community found that 58% think that Brexit will result in the relocation of business to Ireland (from the United Kingdom) and 32% considered that it will force their business to look at new export opportunities outside of the United Kingdom.

Main internationalisation programmes

In June 2018, the Irish Government announced the Global Ireland – Ireland’s Global Footprint to 2025 initiative, which includes a number of objectives related to exporting and internationalisation of Ireland in terms of culture, aid, etc. The exporting objectives by 2025 are aimed at accelerating diversification of exports by Enterprise Ireland clients so as to double the total value of exports of EI clients outside the UK from the 2015 baseline, double Eurozone exports and increase diversification with at least 70% of exports going beyond the UK. These targets are similar to those set for the “Expand Reach” objective of Enterprise Ireland’s 2017-20 strategy.

SBCI, a state-owned bank, launched the Brexit Loan Scheme together with the Department of Finance, Department of Business, Enterprise and Innovation (DBEI) and the Department of Agriculture, Food and the Marine at the end of Q1 March 2018. The scheme was designed to support internationalising companies and is particularly well suited for young exporters needing working capital. The programme is described in Section one of this Chapter (Strategic Banking Corporation of Ireland (SBCI)).

In the field of internationalisation, Enterprise Ireland (EI) has the main remit to support and develop Irish indigenous firms with export activities. Other agencies are also active in promoting specific sectors such as Bord Bia for the food sector.

Enterprise Ireland’s suite of activities in support of exporting firms include:

-

Brexit Be Prepared Service. The advisory service and grant (up to EUR 5 000) is intended to enable exporters to hire consultants to support companies in how they can respond to threats and opportunities arising from Brexit.

-

Market Discovery Grants, launched in January 2018 by EI, provides support towards internal and external costs incurred when researching new markets for products and services. Support under the Market Discovery Fund applies when eligible companies are either looking at a new geographic market for an existing product/service or an existing geographic market for a new product/service. Support can be provided over an 18-month period from project start date to project end date with a maximum grant of EUR 150 000. 157 Market Diversification grants were awarded in 2017.

-

The Market Research Centre through which EI makes available to its clients market research reports purchased from leading providers. Companies can view these reports at the Market Research Centre in the Dublin office or via the LEOs. EI also produces a range of market access guides which provide companies with key information on specific markets that are of significant importance to Irish exporters;

-

EI International Offices Network. In line with Global Ireland, EI’s and Bord Bia’s current network of overseas offices will be reinforced with expended presence in several EU cities;

-

Trade missions & events (57 ministerial led trade events in 2017);

-

Supporting export selling capabilities through three main initiatives: Graduates for International Growth (G4IG); the International Selling Programme and Excel at Export Selling workshops.

The International Selling Programme is the flagship programme designed to equip Irish companies with the necessary capability to deepen their presence in an existing international market or enter a new international market. Delivered in partnership with Dublin Institute of Technology (DIT) this practical programmes aim to improve participating companies’ ability to access new markets and grow export sales. Graduates for International Growth (G4IG) helps ambitious internationally trading companies recruit graduates with the potential to be the next generation of business development executives. Excel at Export Selling aims at rapidly embedding the proven tools of good international selling practice into the sales teams of Irish companies across all industry sectors.

In terms of outcomes, in 2017, EI reported 1 391 new overseas contracts in supported firms, 350 new overseas presences and 51 first-time exporters outside the United Kingdom. In 2017, exports in EI client companies were up by 7% on 2016 levels.

InterTradeIreland provides a suite of supports to support Irish SMEs in exporting across the border with Northern Ireland and with preparations for Brexit. InterTradeIreland supports include: sales supports and services such as the Trade Accelerator Voucher worth up to GBP 1 000 or EUR equivalents for professional cross-border advice; and Acumen which provides financial assistance to source and fund the right sales and marketing employee to help develop cross-border sales (funding of up to EUR 18 750 available). InterTradeIrelands Brexit Advisory Service has been operational since May 2017 and provides supports to businesses trading across the border including dedicated events, a tariff checker tool and the Brexit Start to Plan Voucher for professional advice in relation to Brexit.

The agro-food sector’s special position within the Irish economy and the potential for the sector to grow further, as well as its particular vulnerability to Brexit, is reflected in the adoption of the Food Wise 2025 Strategy, a 10 year plan for the sector. The Strategy reflects the importance of a deep understanding of what consumers, often in distant markets, really want, and ensuring Irish farmers and food companies are aware of those needs. The Strategy also highlights the importance of communicating key messages about what makes Irish food unique to the international market. Food Wise 2025 has identified ambitious and challenging growth projections for the industry over ten years.

The LEOs also offer support for exporters through the Technical Assistance for Micro Exporters grant, The grant covers 50% of eligible costs up to a maximum of EUR 2 500 for micro enterprises to explore and develop new market opportunities, for example by researching export markets, exhibiting at trade fairs, preparing marketing material, and developing websites specifically targeting overseas markets.

Internationalisation challenges and policy options

A key challenge facing Irish SMEs is to diversify their export bases in the face of increasing global competition and an impending “Brexit shock.” As the UK market is the first step on the export road for may smaller Irish-owned firms, and in many cases the main or only export market, the urgency to diversify their overseas market is evident. The Government and Enterprise Ireland (as well as Bord Bia for the food sector) have taken a number of measures to help businesses anticipate and prepare for Brexit. It is too early to assess whether the various initiatives launched in the last two years will be sufficient to help smaller companies export further afield.

The range of funding and advisory programmes provided to SME exporting firms are similar to those of other advanced north-western European countries (e.g. Business Finland’s suite of assistance). However, there remains a challenge related to raising ambition in the management teams of smaller firms to begin exporting (first-time exporters) or to move beyond the UK market. Expanding programmes in favour of enhanced management skills, notably in second tier management, through coaching and training support would help to increase the number of ‘export-capable’ firms amongst Irish SMEs.

copy the linklink copied!Entrepreneurship education and skills programmes

The DBEI and other Government departments provide significant support for entrepreneurship education.4 Ireland's National Skills Strategy 2025, published by the Department of Education and Skills (DES) in January 2016, includes a commitment to develop an Entrepreneurship Education Policy Statement, which will inform the development of entrepreneurship guidelines for schools. In Ireland, at primary level, it is possible for entrepreneurship education to be incorporated directly as part of discretionary curriculum time or indirectly in areas such as drama, art, oral language, creative writing, project/group activity or art. Similarly, at secondary level, entrepreneurship education may be incorporated into business subjects or transition year projects.

The DES supports enterprise in schools through the development of a basic understanding of the principles and methods of business. It also encourages active and collaborative learning, the development of ICT skills and good arts education, all of which foster creativity, innovation, risk-taking and other key elements in entrepreneurial thinking and action.

Skills underpinning entrepreneurship are also central to the new Framework for Junior Cycle and there are many examples of good work being undertaken in many schools at transition year in mini-company formation and other projects designed to foster entrepreneurship.

In addition, the local enterprise offices (LEOs) and various non-governmental bodies run pupil/student entrepreneurship initiatives. At primary level, the Junior Entrepreneur Programme is a non-governmental (business sponsored) initiative to promote entrepreneurial skills for primary 5th and 6th class pupils over a 12 week period leading to the creation and production of a product/service. Similarly, in the South Dublin LEO area, Bí Gnóthach is an education programme that introduces 5th and 6th class students to many aspects of setting up and running a business. In addition, the Junior Achiever (JA) programme runs a range of inspirational activity-based learning sessions with primary pupils at all ages. Although not solely focused on entrepreneurship skills, the programme is delivered by business volunteers in schools.

At secondary level, the Student Enterprise Programme (SEP)5, run by the LEOs, introduces students to the practical experience of setting up a business. The SEP is Ireland’s largest student enterprise competition with over 23 000 students from 480 schools taking part. The programme provides free teacher resource packs including student workbooks, sample student business reports and videos of successful entrepreneurs. Other initiatives supporting student entrepreneurship education and learning include the Fóroige NFTE Youth Entrepreneurship programme6, which operates in and out of school activities and the All Island Youth Entrepreneurship awards. In the same vein, JA runs a range of activities promoting STEM and career success courses as well as Enterprise in Action (for 15-18 year olds) which encourages students to examine the role of an entrepreneur in today’s society.

An OECD/European Commission review of Entrepreneurship and Innovation in Higher Education in Ireland was published in 20177 and provides an detailed assessment of the situation based on the HEInnovate assessment framework (including a survey of all universities and Institutes of Technology). The report concluded that the Irish higher education system plays ‘a fundamental role in fostering entrepreneurial career paths’ for students and staff. A wide range of initiatives were identified including undergraduate and postgraduate courses, work-based learning, business start-up and incubation programmes, mentoring and coaching and national competitions such as the All-Ireland Business Plan Competition. These activities are driven by senior management in higher education institutions (HEIs), usually by a combination of the vice-president for research and the heads of faculty. An issue that the report raised was that the HEIs were heavily and in some cases totally dependent on temporary project funding, putting into question the sustainability of their entrepreneurship education initiatives. The report recommended that entrepreneurship education should be expanded across all disciplines, that there should be an increase in the number of interdisciplinary education activities and boost the number of places available on venture creation programmes.

The report noted that to support entrepreneurship and innovation, HEIs need to be entrepreneurial and innovative themselves in how they organise education, research and engagement with business and the wider world. This requires introducing supportive frameworks at national and HEI level for resource allocations, staff incentives, training for entrepreneurship educators, strategic partnerships and so on. A strong emphasis is placed on supporting teachers to teach entrepreneurship with continuous professional development activities supported by CEEN, the Campus Entrepreneurship Enterprise Network8 and the National Forum for the Enhancement for Teaching and Learning in Higher Education9. CEEN, the national network for promoting and developing entrepreneurship and enterprise at third level, runs a number of projects such as the Entrepreneurship Scholarship Scheme which was initiated in order to provide a pathway for entrepreneurial second level students (that have benefitted from NFTE support) into an entrepreneur-ready third level educational environment. In addition, Springboard+, which provides free and subsidised higher education courses in areas of identified skills needs, has provided a range of entrepreneurship courses around the country since it commenced in 2011.10

In terms of life-long learning and training focused on entrepreneurship skills, Enterprise Ireland, Science Foundation Ireland and local enterprise offices (LEOs) and a number of other government agencies support various initiatives aimed at incubation, early-stage entrepreneurship and high growth firms. The major initiatives including Enterprise Ireland’s entrepreneurial training activities linked to its equity financing, the boot camp programme in collaboration with the US National Science Foundation (NSF), and New Frontiers, Ireland’s national entrepreneur development programme, delivered at local level by Institutes of Technology and funded by Enterprise Ireland.

Overall, a broad range of entrepreneurship education and skills programmes have been developed in Ireland, reflecting a broadly held view that entrepreneurship education should become part of the core curricula at all levels. The initiatives are funded by government departments and agencies, in some cases in partnership with business, and delivered by educational institutes and not-for-profits and businesses. The main scope for improvement concerns shifting away from project based funding and further embedding and broadening entrepreneurial education at primary and secondary education levels. An opportunity also exists to adopt a more challenging approach to entrepreneurship education in the transition year, which could even provide credits into Business Studies in the third-level cycle. The on-going reform and merger of institutes of technology into technology universities may also provide an opportunity to strengthen entrepreneurial education related to specific vocational skills.

copy the linklink copied!Workforce skills development programmes

Chapter 3 of this report highlights that skills shortages are becoming more prevalent, especially among SMEs competing with multinationals on the labour market, which is compounded by issues such as cost of living (in Dublin) and infrastructure (in the regions).

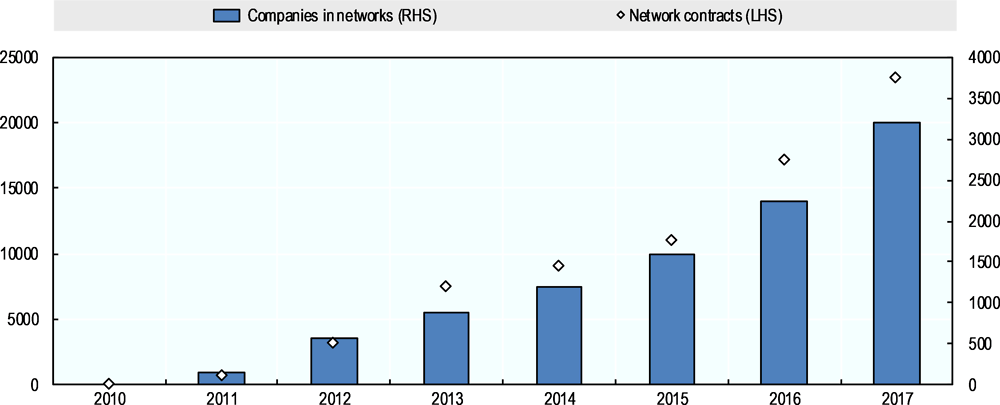

The Irish Government’s Action Plan for Jobs 2018 (the 7th in an annual series of plans) outlines a cross-departmental approach to maximising employment. A regional dimension is provided through eight regional action plans. The 2018 plan focuses on four objectives including preparing for Brexit, stimulating regional development through job creation, boosting participation and ensuring a growing talent pool and meeting skills needs, and boosting productivity.