1. Coverage and inclusiveness

Contrary to perceptions that career guidance concerns mainly young people in school, survey data suggest that there is substantial demand for career guidance services among adults. However, adults most exposed to the risk of job loss and skills obsolescence use career guidance services less frequently than their less disadvantaged peers. This chapter examines the reasons why adults typically seek guidance as well as the main barriers to the use of these services.

Building inclusive career guidance systems is key to ensure that all adults, including the most disadvantaged, can access the assistance they need to make well-informed educational, training and occupational choices. The findings of this chapter for the six countries (Chile, France, Germany, Italy, New Zealand and the United States) covered by the OECD Survey of Career Guidance for Adults (SCGA) can be summarised as follows:

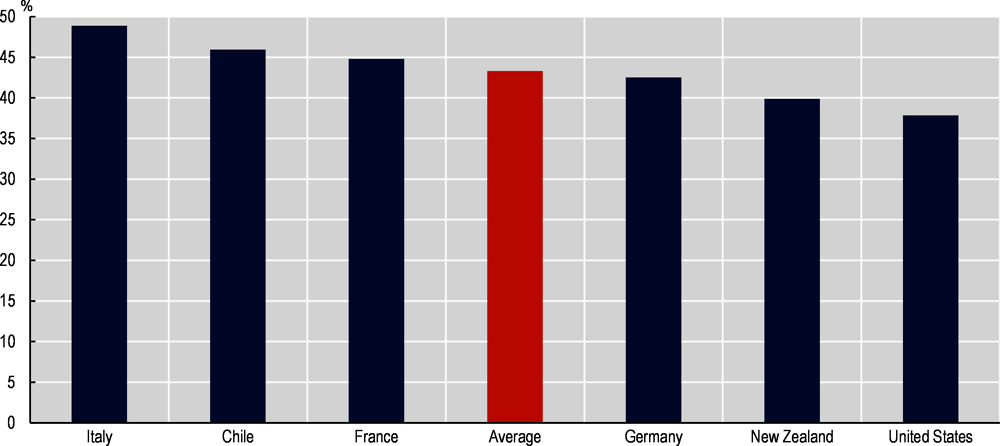

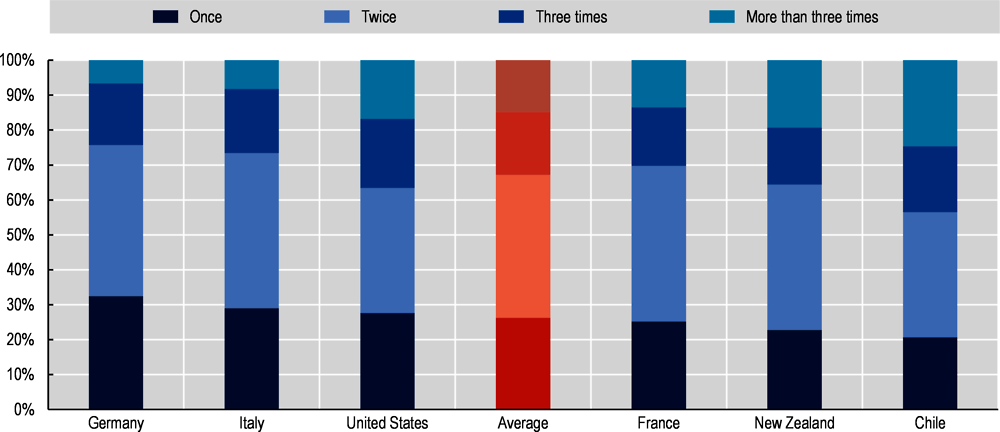

Contrary to perceptions that career guidance concerns mainly young people in school, there is substantial demand for career guidance among adults. On average, 43% of adults spoke with a career guidance advisor over the past five years. Most adults who used career guidance services had multiple interactions with advisors.

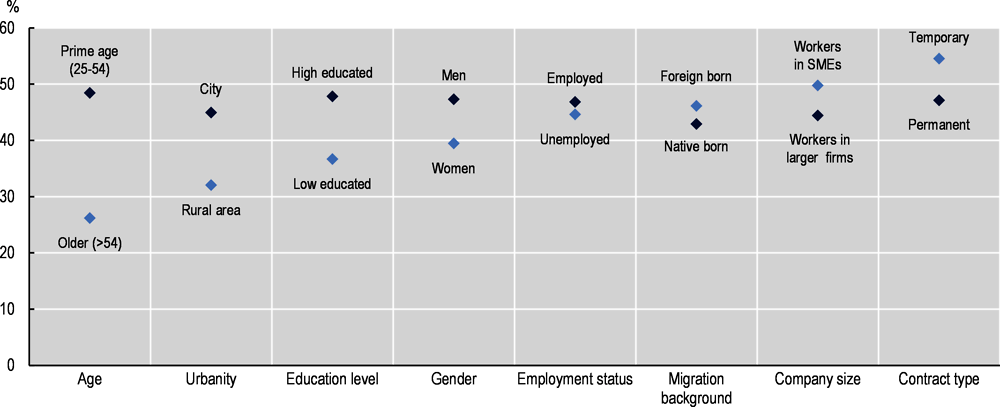

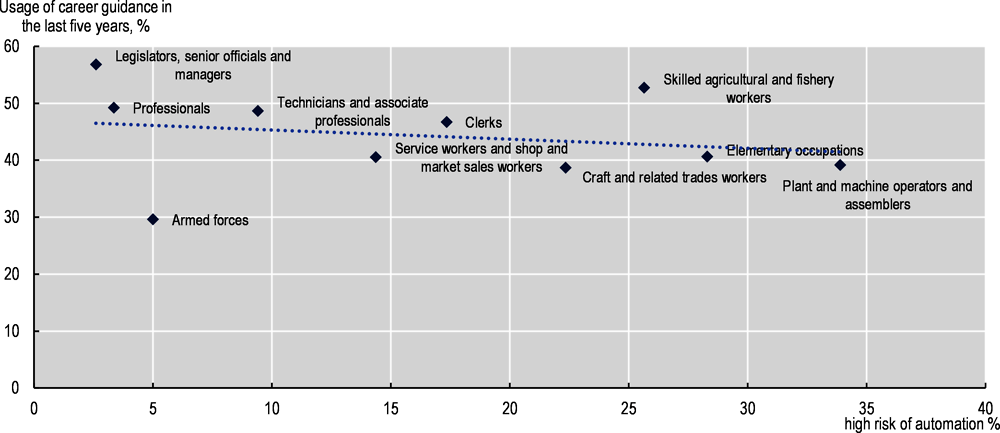

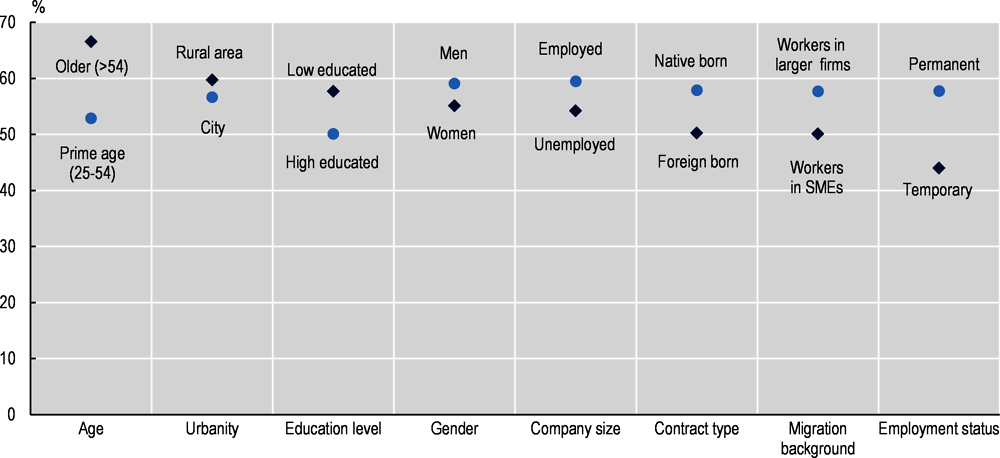

However, many of the same groups who already face disadvantage in the labour market and in training participation use career guidance services less often than the reference population. The largest differences in the use of guidance services are found between prime-age individuals (25-54) and older people (over 54) (22 percentage points), followed by adults living in cities and in rural areas (14 percentage points), high- and low-educated adults (11 percentage point), men and women (8 percentage points) and the employed and the unemployed (2 percentage points). Workers in occupations with a high risk of automation are also less likely to use career guidance than those in occupations with a lower risk of automation. By contrast, SME workers use career guidance services more than workers in larger firms (5 percentage points). There is no statistically significant difference in the use of career guidance for permanent versus temporary workers, or for native-born versus foreign-born workers.

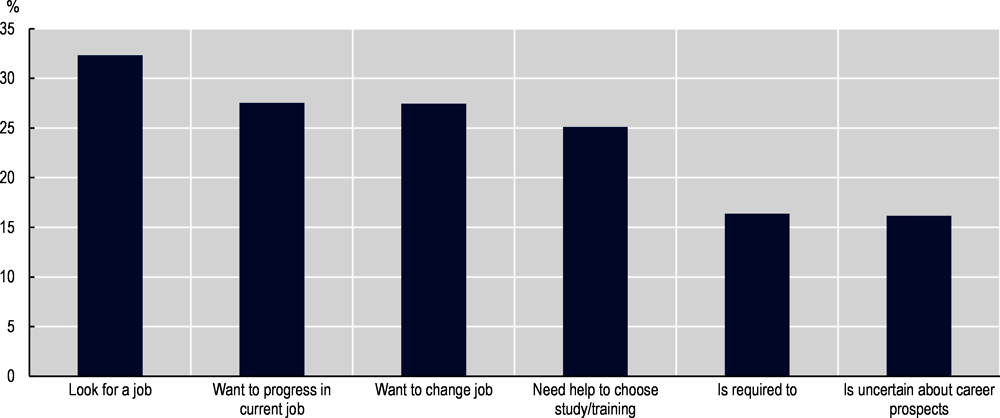

The most common reason for speaking with a career guidance advisor is to receive job search assistance (32%). Accessing information on education and training options is the second most popular reason (25%). Few adults speak with a career guidance advisor only because they are required to (e.g. to receive unemployment benefits).

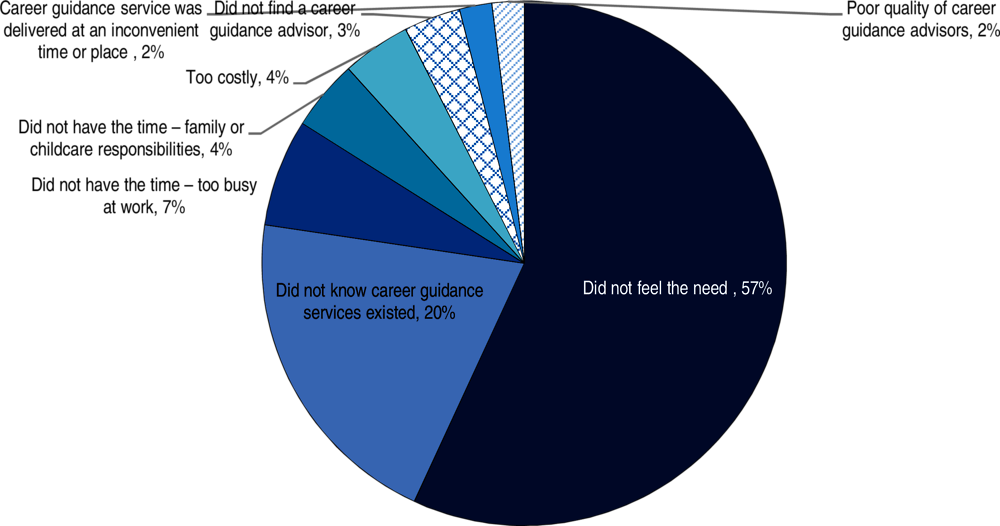

Of those adults who do not use career guidance services, most do not feel they need to (57%). The rest report a range of barriers: 20% did not know services existed; 11% did not have time (for work, family or childcare reasons); 4% found the service too costly; 3% did not find a career guidance advisor; 2% deemed the service of poor quality; and 2% thought the service was delivered at an inconvenient time or place.

In addition to speaking with a career guidance advisor, adults make use of other means to access information on job and training options. Some 69% of adults look for information online. A similar share (67%) relies at least to some degree on the advice of family members and friends. Some 57% of adults engage in career development activities (e.g. discussions with human resources professionals at work, visits to a job fair or a training provider).

Career guidance can help adults to navigate a changing world of work. Policy around career guidance has tended to focus on young people in schools, who are about to transition either into higher levels of education or into the labour market. But given the changing demand for skills as a result of technological change, globalisation, population ageing, and green transitions, career guidance is just as important for adults as it is for young people.

Career guidance refers to a set of services to assist individuals in making well-informed educational, training and occupational choices (Box 1.1). This report focuses on career guidance services available to adults (age 25-64). Services may either be targeted at adults who are employed, unemployed or inactive, or may be open to anyone regardless of employment status.1 A variety of terminology is used across countries to refer to the professionals who deliver career guidance services. For the purposes of this report, a ‘career guidance advisor’ is someone who delivers career guidance services, whether face-to-face, by telephone, instant messaging or video conference.

This chapter assesses the coverage and inclusiveness of career guidance systems in OECD countries. Section 1.1 looks at what share of adults use career guidance services, as a measure of coverage. Section 1.2 looks at inclusiveness, in particular assessing how the use of career guidance varies according to socio-economic characteristics, employment status, contract type, sector and occupation. Section 1.3 analyses the reasons why adults typically seek career guidance in the first place. Section 1.4 highlights the key barriers to the use of career guidance services. Section 1.5 explores the use of online sources of information on education and job opportunities, while Section 1.6 considers the use of less formal careers support (e.g. advice from family and friends, and participating in career development activities). Finally, Section 1.7 presents a profile of adults who might be at risk of being poorly informed.

This report uses the term ‘career guidance’ to refer to services intended to assist individuals to make well-informed educational, training and occupational choices. Across the globe, career guidance is known by different terms, including career development, career counselling, educational and vocational guidance and vocational psychology.

Effective career guidance performs a number of functions. It informs individuals about education, training and employment opportunities, and makes this information accessible by helping with its interpretation. Career guidance helps individuals to reflect on their strengths and interests, provides tailored advice, and empowers individuals to make better decisions about their lifelong career development and learning.

Career guidance can be provided in different settings, for different target groups, and through different channels. It is commonly provided by public employment services, private providers, educational institutions, and to a lesser extent, within companies. Services may be targeted to particular groups, such as young people in schools, unemployed adults or low-skilled adults, or they may be open to anyone. While traditional face-to-face interviews are still the way most services are delivered, career guidance services have diversified in the last decades to include remote alternatives, including telephone, instant messaging or video conference.

Source: OECD (2004[1]), Career Guidance and Public Policy: Bridging The Gap, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264105669-en.

Nearly all OECD countries have put in place some sort of career guidance service for adults. These services are provided by a variety of actors, including the public employment service (PES), dedicated public career guidance services, private providers, associations and social partners (see Chapter 2).

But while services may be available, a key challenge is whether they are accessible and used. Knowing how many people use career guidance services is difficult, considering that very little internationally comparable data exist on the use of career guidance services for adults (see Box 1.2).

To fill this information gap and shed light on the use, inclusiveness and quality of career guidance systems for adults, the OECD carried out in 2020 the Survey of Career Guidance for Adults (SCGA) in six OECD countries: Chile, France, Germany, Italy, New Zealand and the United States (see Annex B for more information on the survey methodology).

According to the SCGA, 43% of adults have spoken with a career guidance advisor over the past five years on average across the six countries analysed. Rates span from 38% in the United States to 49% in Italy (Figure 1.1).2

The intensity of service, i.e. the number of interactions that an adult has with a career guidance advisor every year, is another important indicator of how well career guidance services are used. It provides insights on whether there is a follow-up after a first consultation, and if there is continuity in the service delivery. Most adults who use career guidance services have multiple interactions with advisors. Figure 1.2 shows that only one in four adults (26%) who spoke with a career guidance advisor over the past year had a single interaction, while 41% had two interactions, and 33% spoke with a career guidance advisor three or more times.

Internationally-comparable data on the use, inclusiveness, and quality of career guidance services is limited. The only available survey is the Adult Education Survey (AES), which covers adults’ participation in education and training (formal, non-formal and informal learning) and is one of the main data sources for lifelong learning in the European Union. The AES covers the resident population aged 25-64.

The AES provides two indicators on the use of career guidance services: (i) the share of adults who receive information or advice/help on learning possibilities from institutions/organisations; and (ii) the share of adults who looked for information concerning learning possibilities. The data refer to the 12 months preceding the survey.

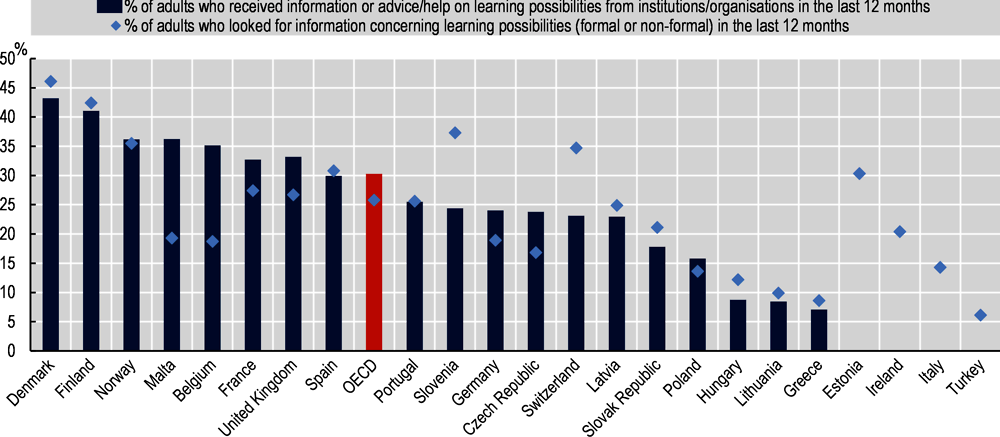

Figure 1.3 shows that – on average among OECD countries in the European Union – 30% of adults received information or advice/help on learning possibilities from institutions/organisations over the past year.1 Rates ranged from less than 10% in Greece, Hungary and Lithuania to over 50% in Austria and Sweden.

Some 27% of adults looked for information concerning learning possibilities over the past year. Rates spanned from less than 10% in Greece, Lithuania and Turkey to over 40% in Denmark, Finland and the Netherlands.

The AES also collects information on the types of providers (e.g. public employment service, education or training institutions), whether the service was offered free of charge, the type of information/advice offered (e.g. skills assessment, recognition of skills, learning possibilities), and channels of delivery (e.g. face-to-face, phone, online).

The AES has some limitations. The survey does not capture the quality of services delivered and only asks about guidance relating to learning, thus excluding guidance relating to occupational choices.

← 1. The results of the AES are generally aligned with the results of the OECD Survey of Career Guidance for Adults (SCGA). The SCGA found that 31% of adults spoke to a career guidance advisor over the past 12 months – very close to the 30% of adults in the AES who received information or advice/help on learning possibilities from institutions/organisations. There is some discrepancy, however, on the second indicator. According to the SCGA, 69% of adults looked online for information on employment, education and training opportunities over the past year – a much higher rate than what is captured in the AES (27%). This discrepancy can be explained by the fact that AES asks only about information concerning learning possibilities, while the SCGA also covers employment opportunities. It may also be due to differences in country coverage between AES and SCGA.

To be inclusive, career guidance systems need to be accessible to all, and particularly to those groups most in need of advice – e.g. those who are already struggling in the labour market and/or who need training but are not getting it. These disadvantaged groups include the unemployed who need guidance to look for a job, low-educated adults who may need help to select a relevant training or upskilling programme, migrants who may need to have their qualifications recognised, or older adults with obsolete skills or qualifications who need advice about how to upskill or retrain.

Based on the SCGA, Figure 1.4 shows differences in the use of career guidance services between adults who are already facing disadvantage at work and in training and their more advantaged peers. The largest gaps are found between prime-age adults (25-54) and older adults (over 54) (22 percentage points), followed by adults living in cities and in rural areas (14 percentage points), high- and low-educated adults (11 percentage point), men and women (8 percentage points) and the employed and the unemployed (2 percentage points).

By contrast, other potentially disadvantaged groups take up guidance more than their counterparts do. This is the case for foreign-born adults, workers in SMEs, and temporary workers, although differences are small (3 percentage points, 5 percentage points, and 7 percentage points, respectively). A tentative explanation is that these groups are proactive in seeking advice and guidance as they have more unstable work conditions. For example, temporary workers are more likely to experience unemployment than permanent workers. SME workers may be interested in moving into more secure, better-paid jobs in a larger firm.3 Foreign-born adults may need to look for information on how to access language classes, and/or on how to have their qualifications recognised – especially if they recently moved to a new country. Compositional differences may also play a role. For example, temporary workers tend to be younger, on average, than permanent workers. It should also be noted that the results for certain population groups (e.g. foreign born adults) need to be interpreted with caution, due to small sample sizes.

Running a pooled cross-country regression analysis can help to isolate the effect of each of the above factors on the use of career guidance. Table 1.1 shows probit regression results of the use of career guidance on a set of individual, job, and firm characteristics. These results confirm several of the descriptive relationships shown in Figure 1.4: being younger, living in a city, highly educated, and male continue to be the strongest predictors that one will use career guidance. Workers in SMEs continue to have higher likelihood of using career guidance than those in larger firms. Some of the relationships no longer hold, however. In particular, there is no statistically significant difference in the use of career guidance between permanent and temporary workers, or between native-born and foreign-born workers.

The use of career guidance services also varies across occupations, with persons working in occupations with a high risk of automation using career guidance services less than those in occupations with a lower risk. Figure 1.5 shows that, on average, the use of career guidance is lowest among less-skilled occupations (e.g. craft and related trade workers, plant and machine operators and assemblers, services and sales workers, and elementary occupations4), where less than 40% of workers spoke with a career guidance advisor over the past five years. These also tend to be the occupations with a relatively high risk of automation, according to recent analysis (Nedelkoska and Quintini, 2018[2]). The use of career guidance is highest among more skilled occupations with a lower risk of automation such as managers and professionals,5 where the rate stands at 50% or more.

Adults seek career guidance for different reasons, depending on where they are in their career, their employment status, and job ambitions. They may be looking for a new job, need assistance to choose a training or education programme, or may simply be obliged to consult with a career guidance advisor (e.g. to receive unemployment benefits, or if they plan to use subsidised training6 – see Chapter 2).

According to the SCGA results on reported reasons for speaking with a career guidance advisor (Figure 1.6):

The most common reasons are related to job-search assistance: 32% of adults who spoke with an advisor were looking for a job, and 27% wanted to change job (e.g. in a different sector).

Another common reason is to receive counselling on in-company progression (28% of adults).

Receiving information on education and training options is another popular reason for seeking career advice (25% of adults).

Uncertainty about future labour market prospects or being required to use career guidance were the least common reasons (16% of adults each).

Reasons for speaking with a career guidance advisor vary by employment status. For example, the SCGA shows that 72% of the unemployed seek advice to look for a job. About 39% of inactive adults (retirees, or those not working for other reasons) seek advice to look for a job and 29% because they need help to choose a study/training programme. About 37% of all workers (including permanent employees, temporary employees, employees without a contract, and the self-employed) seek advice because they want to progress in their current job and 33% because they want to change job.

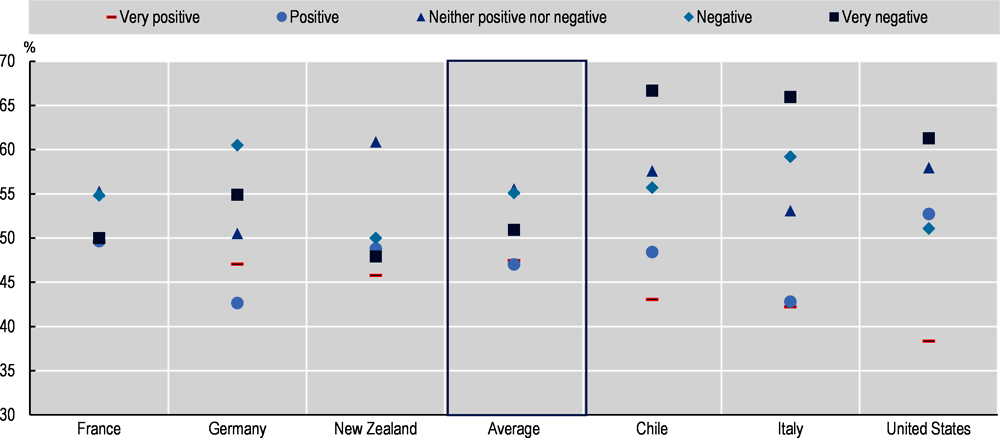

It could be expected that adults who are more worried about their future career prospects would be more proactive in looking for help from a career guidance advisor. The data seem to corroborate this assumption. The SCGA asked respondents about the future labour market prospects of their current job and sector. Those who were very negative, negative or neutral about their future labour market prospects were more likely to seek advice, on average (Figure 1.7). By contrast, adults who felt positive or very positive were the least likely to speak with a career guidance advisor. That said, this pattern does not hold consistently across all six countries in the survey.7

To increase take-up of existing programmes, it is important to understand the barriers preventing adults from seeking career guidance. Among adults who did not speak with a career guidance advisor over the past five years, 57% simply did not feel the need to (Figure 1.8). It is possible that these adults are already well-placed in their career, are not planning a career shift, or are not interested in exploring up- or reskilling options. It is also possible that they do not fully value or appreciate the potential benefits of receiving career guidance from professional advisors.

Another 20% of adults did not speak to a career guidance advisor because they did not know services existed – suggesting that there is a need to advertise career guidance services more widely. About 11% did not have the time (for work, family or childcare reasons) – suggesting that more could be done to deliver services more flexibly to fit workers’ and/or care givers’ schedules. The remaining 11% report not using services because they were too costly (4%), they did not find a career guidance advisor (3%), the service was of poor quality (2%), or delivered at an inconvenient time or place (2%).

Some adults who do not feel the need for guidance are part of vulnerable groups who could potentially benefit from career guidance services. For example, 67% of older adults, 60% of those living in rural areas, and 58% of low-educated adults said that they did not feel the need to speak to a career guidance advisor – higher than their less disadvantaged counterparts (Figure 1.9). However, women, the unemployed, foreign-born adults, workers in SMEs and temporary workers were less likely to say that they did not feel the need to speak to a career guidance advisor than their counterparts.

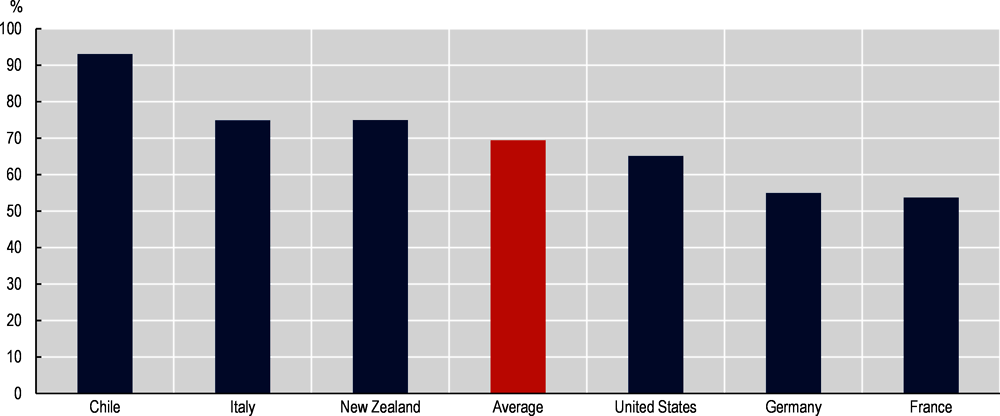

Before or instead of seeking advice from a career guidance advisor, many adults look independently online for information on employment, education and training opportunities. Although this form of career guidance and advice requires autonomy and initiative from the users, it is generally based on sound and up-to-date information on labour market needs. Based on the SCGA, 69% of adults looked online for information on employment, education and training opportunities over the past five years, with rates ranging from 55% in Germany and France to over 90% in Chile (Figure 1.10).

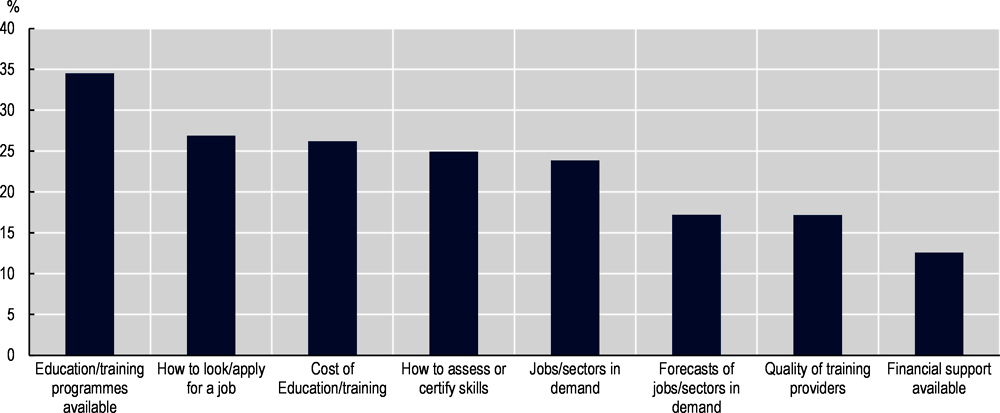

Adults look online for information on employment, education and training opportunities for various reasons. While the most common reason to speak to a career guidance advisor is to receive help with a job search, most adults who look for information online are looking for information on education and training programmes. Figure 1.11 highlights the main types of information that adults look for online:

Most adults look for information about available education and training programmes (about 35% of adults who look online). About a quarter of all respondents are interested to learn more about the cost of education and training programmes (26%). Far fewer adults look for information on the quality of training providers (17%), or the financial support available to meet training costs (13%) – perhaps reflecting the fact that this type of information is rarely available online (see Chapter 2).

Just over a quarter of adults (27%) look for information on how to search/apply for a job.

A quarter of adults (25%) look online to understand how to have their skills and competences certified or assessed (e.g. through recognition of prior learning processes).

Some adults go online to find out about jobs in demand or those forecasted to be in demand (24 and 17%, respectively) – probably with a view to better target their job search efforts or education choices.

In addition to speaking to a career guidance advisor or looking online for information on employment and training options, many adults use more informal types of career support. They can ask family members and/or friends for advice. They can also engage in different types of career development activities, such as discussing with human resources (HR) professionals at work, visiting a job fair or a training provider.

1.6.1. Advice from family members and friends

Family members or friends can be a source of informal advice and career guidance, though such advice is not a substitute for professional career guidance. Advice from family and friends may lack reliability and impartiality, and may fail to take into account an adult’s skills, merit, preferences, or labour market needs. Moreover, the usefulness of such advice largely depends on how informed one’s friends and family are, which in turn depends on one’s socio-demographic background. Adults who are more highly-educated or from more privileged socio-economic backgrounds tend to have networks of family and friends who are better informed and better connected.

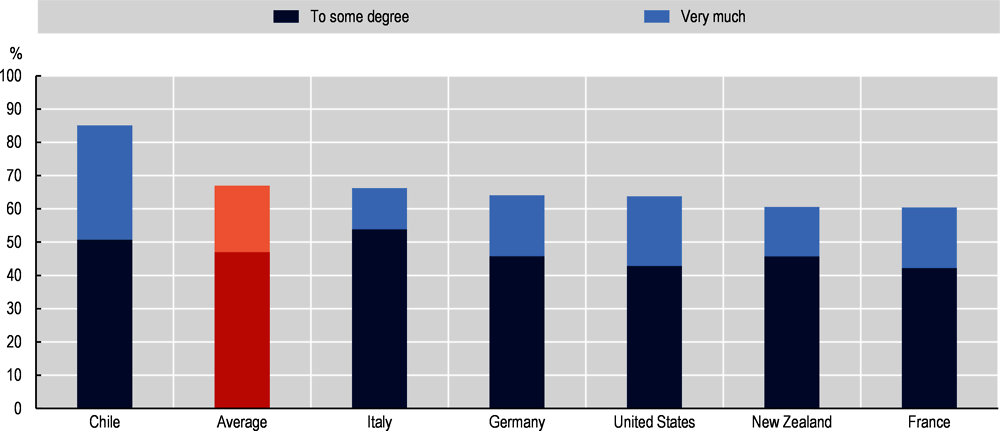

The SCGA suggests that the advice of family and friends is an important source of career information for adults. Nearly half of adults (47%) rely “to some degree” on the advice of family and friends to make choices that will affect working life (Figure 1.12). Another 20% relies “very much” on this advice, with this share being the lowest in Italy (12%) and the highest in Chile (34%). Only 13% of adults report that they do “not at all” rely on family and friends for advice.

1.6.2. Career development activities

Participating in career development activities may allow adults to gain a better understanding of the employment and training opportunities available to them. Examples of career development activities include speaking with HR personnel or a manager at work, visiting a job fair, visiting a training provider, participating in job rotation/work site visits, or doing an internship. These activities may also give adults an opportunity to think more concretely about their skills, ambitions, and career preferences.

More than half of adults (57%) participated in one or more career development activities in the 12 months preceding the survey. The most common activities were speaking with one’s manager or HR professionals at work (15%), visiting a job fair (14%), or visiting a training provider (13%). Fewer than 10% of adults participated in workplace career development activities, such as job rotation/work site visits, internships or apprenticeships. Results are quite consistent across the six countries analysed.

According to the SCGA, most adults (76%) access information about education and employment opportunities through formal channels, either by speaking to a career guidance advisor or looking online or both. Adults who do not access any formal or informal career support or those who rely solely on informal support may be most at risk of making poor education and employment decisions. This section uses clustering techniques to identify groups of adults who might be at risk of being poorly informed.

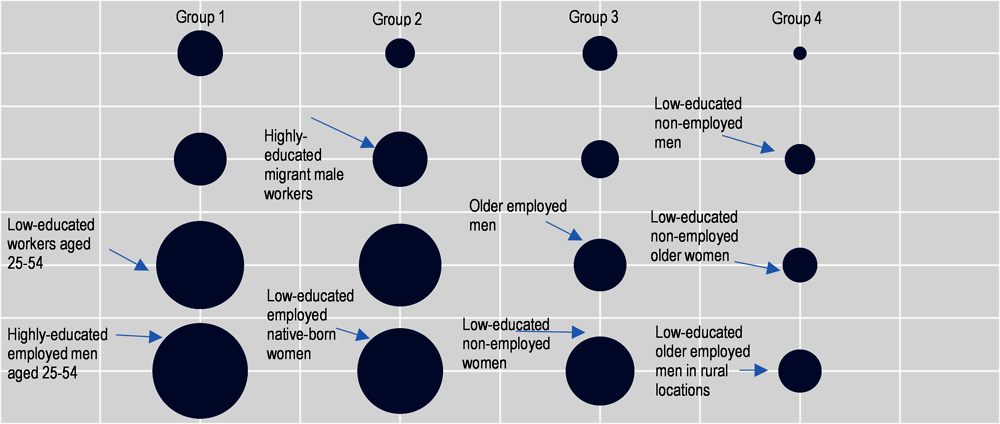

Adults in the sample were divided based on their use of different types of career support. Table 1.2 shows the four largest and most meaningful groups for analysis. Adults in Group 1 used all types of career support (both formal and informal). Those in Group 2 did not speak to a career guidance advisor, but looked online for information and made use of informal support (advice from family or friends, or participation in a career development activity). Adults in Group 3 used only informal support, while those in Group 4 did not consult any career support at all.

Figure 1.12 shows the results of a cluster analysis. The analysis identifies “clusters” of adults in the sample who share similar socio-economic characteristics (i.e. age, gender, place of birth, place of residence, education, and employment status). Groups 1 and 2 include both high-educated and low-educated adults. On the other hand, adults in Groups 3 and 4 tend to be lower educated, older and more likely to live in rural areas. Beyond these broad descriptions, the largest clusters in each group can be characterised as follows:

Group 1: These adults fall into two main clusters: highly-educated employed men aged 25-54 (representing 42% of this group), and lower-educated workers aged 25-54 (36%).

Group 2: Adults in this group fall into two main clusters, made up mostly of workers: lower-educated native-born women (41%) and highly-educated foreign-born men (38%).

Group 3: The two largest clusters of adults in this group are made up of lower-educated adults. The first includes non-employed women (47%). The next largest cluster is made up of employed men aged 55+ (27%).

Group 4: These adults fall into three main clusters, all made up of older, lower-educated adults who are either: employed men living in rural areas (45%), non-employed women (29%), or non-employed men (22%).

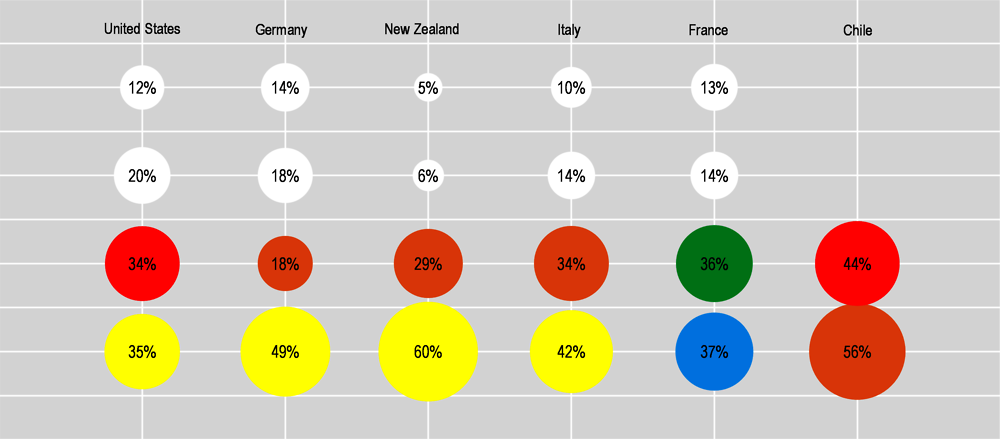

There is some variation across countries in the socio-economic characteristics of the largest clusters in each group. Figure 1.14 shows country-level results from a cluster analysis of all adults in Groups 3 and 4 (i.e. those who are most at risk because they did not speak to a career guidance advisor or look online for information). In most countries covered in the survey, these groups tend to be older (age 55+), low-educated and not employed. The exceptions are Chile and France. In Chile, the largest cluster is made up of employed men aged 25-54. In France, the largest cluster is made up of employed low-educated women living in rural areas.

In the United States, in addition to the characteristics mentioned above (older, low-educated, not employed), adults in Groups 3 and 4 also tend to live in rural areas.

In several countries, the second-largest cluster of at-risk adults is employed men. This is the case in Germany, New Zealand (employed male immigrants) and Italy (employed men aged 25-54).

This analysis suggests that in most countries, policy responses to boost access to formal career support should target low-educated and older adults, though individual country policy responses can be more targeted. In the United States and France, policy responses that involve also reaching out to adults living in rural areas would be beneficial. While adults who are not working are most at risk, several countries also have a significant cluster of employed adults who do not access career support. Efforts to connect employed adults with formal career services should focus on employed men in Germany, New Zealand (particularly immigrants), Italy, and Chile. In France, they should focus on employed women.

References

[2] Nedelkoska, L. and G. Quintini (2018), “Automation, skills use and training”, OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Papers, No. 202, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/2e2f4eea-en.

[1] OECD (2004), Career Guidance and Public Policy: Bridging the Gap, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264105669-en.

Notes

← 1. Career guidance for adults excludes services for young people who are still in initial education (i.e. who are still studying and have not yet had an employment spell). For example, career guidance services offered in schools fall outside the scope of this report.

← 2. The SCGA also collects information on adults who spoke to a career guidance advisor during the 12 months preceding the survey. There is very little substantive difference in responses between adults who used career guidance over the last five years and those who used it over the last year. To benefit from larger sample sizes, therefore, the figures in this report refer to adults who have used career guidance services over the previous five years – unless otherwise specified.

← 3. This finding stands in contrast to previous evidence showing that large firms provide more career support than smaller firms. It could be that workers in SMEs are more proactive than those in larger firms in seeking advice independently, given that they receive less career guidance from within their company. Moreover, even if large firms are more likely to offer career guidance services than SMEs, these services tend to target only the ‘high-performers’ or the high-skilled rather than being open to all employees (see Chapter 2). This could also help to explain the discrepancy.

← 4. Elementary occupations include cleaners and helpers; labourers in mining, construction, manufacturing and transport.

← 5. As defined by the ISCO-08 major group 2. It includes professionals in various categories: science and engineering; health; teaching; business and administration; information and communications technology; and legal, social and cultural.

← 6. In Germany, for example, adults willing to use the training subsidy ‘Bildungsprämie’ need to make an appointment with a specially trained counsellor in one of the 530 guidance offices in adult education centres.

← 7. It is possible that differences reflect not only different demands from users, but also different country strategies about career guidance (e.g. what services are available and who they target).