13. India

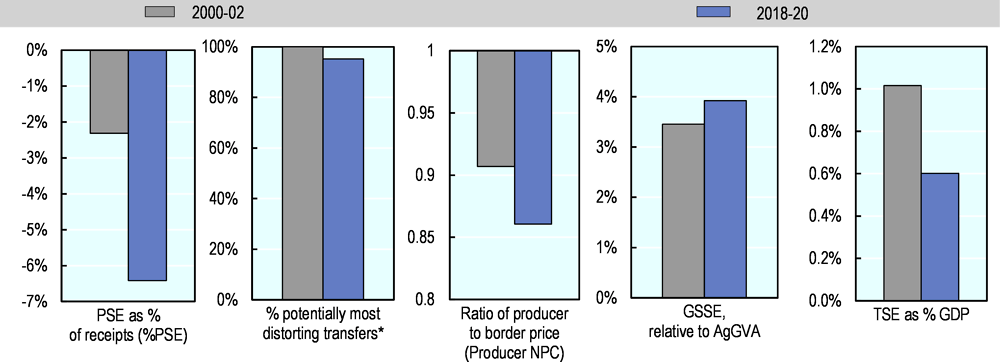

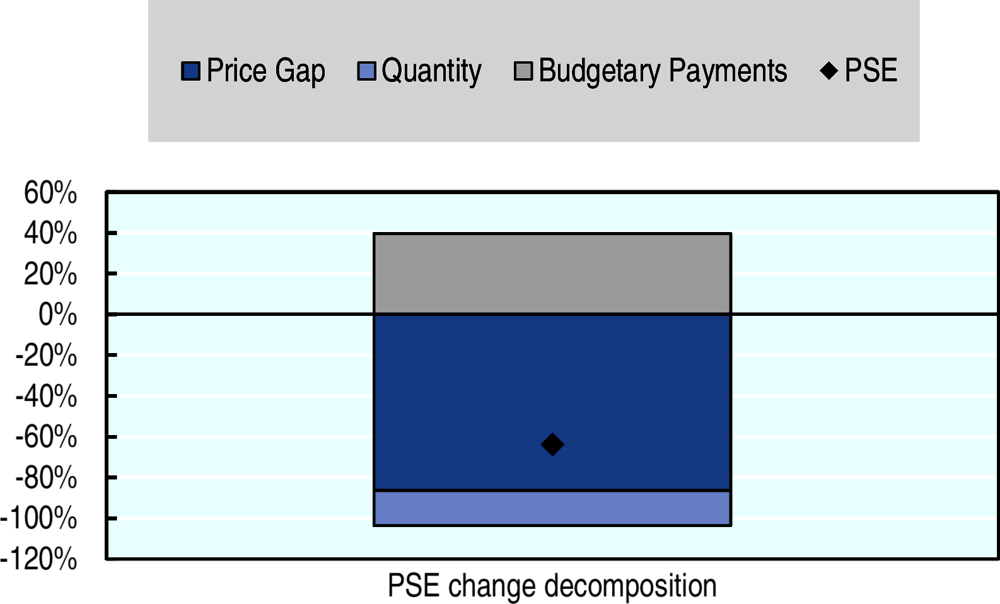

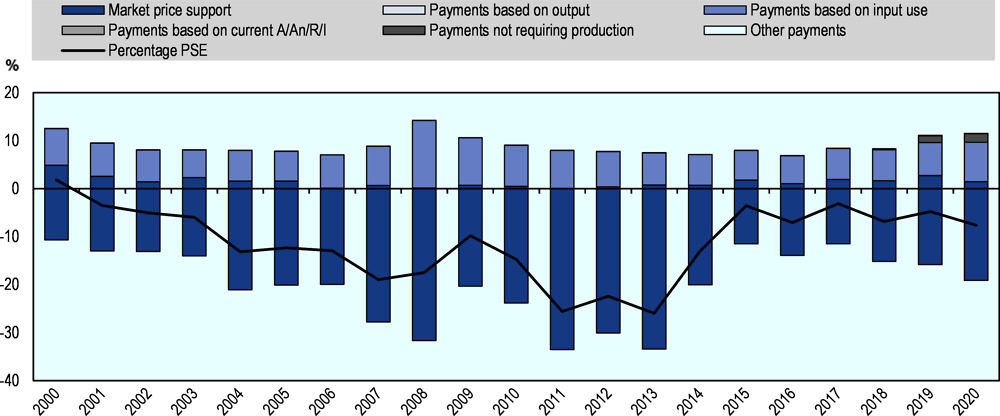

Support to producers in India comprises budgetary spending corresponding to 8.6% of gross farm receipts, positive market price support (MPS) of +2.0% of gross farm receipts for supported commodities, and negative MPS of -17% for those that are taxed. Overall, this led to negative net support of -6.4% of gross farm receipts in 2018-20. Support to producers was negative throughout the last two decades but fluctuated markedly. The negative producer support estimate shows that domestic producers on average have been implicitly taxed, as budgetary payments to farmers did not offset the price-depressing effect of complex domestic marketing regulations and trade policy measures. Virtually all gross producer transfers (whether positive or negative) come in forms that are potentially most production- and trade-distorting, a consistent pattern since 2000-02.

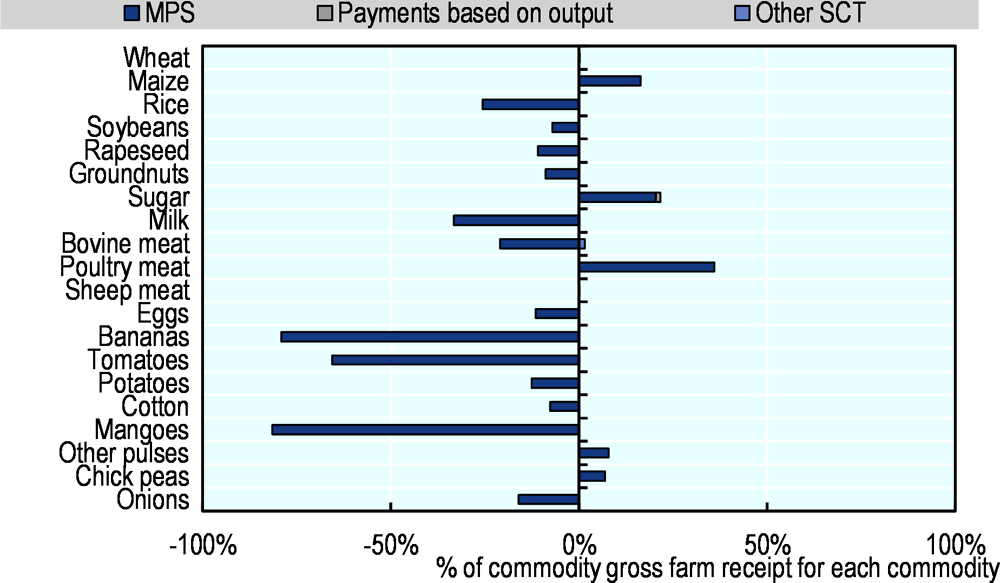

Single commodity transfers (SCT) follow the MPS pattern and vary by commodity. Most commodities were implicitly taxed between 7.1% and 81.5% of commodity receipts in 2018-20. Commodities with positive SCTs – ranging between 0.3% and 36% of commodity receipts in the same period – include wheat, maize, sugar, chickpeas, other pulses and poultry meat.

Budgetary transfers to producers are dominated by subsidies for variable input use, such as fertilisers, electricity, and irrigation water. However, budgetary allocations to the direct income transfer programme, PM-KISAN, have increased since its implementation in 2018.

In turn, public expenditures financing general services to the sector (GSSE), principally for infrastructure-related investments, are only half the level of subsidies for variable input use. At 4% in 2018-20, expenditure for GSSE relative to agriculture value-added increased compared to 2000-02.

Mirroring the farm-price-depressing effect on producers throughout the period covered, policies provide implicit support to consumers. Policies that affect farm prices, along with increased food subsidies under the Targeted Public Distribution System during the COVID-19 pandemic, reduced the costs for consumers with a consumer support estimate of 28.8% of expenditure on average across all commodities in 2018-20. Total budgetary support (TBSE) is estimated at 3.3% of GDP in 2018-20, contributing to an overall positive total support estimate (TSE) of 0.6% of GDP.

The most important new programmes and reforms came in the context of the COVID-19 economic support package of May 2020. New programmes include several schemes to support credit, on-farm services, infrastructure and other general services. The new Agriculture Infrastructure Fund supports farmers, farmer producer organisations (FPO) and agri-businesses, mainly through interest subsidy to credits for the set-up of post-harvest infrastructure such as cold storage, collection centres, and processing units.

Key reforms relate to three acts allowing farmers to sell their products outside of government-regulated markets. These remove limits on private stocking, trading or buying of commodities to promote barrier-free inter and intra-state trade of agricultural commodities: (1) the Essential Commodities (Amendment) Act; (2) the Farmers’ Produce Trade and Commerce (Promotion and Facilitation) Act; and (3) the Farmers’ (Empowerment and Protection) Agreement on Price Assurance and Farm Services Act. However, in mid-December 2020, India’s Supreme Court suspended implementation of the acts and mandated the creation of an expert committee to consult with farmer groups before proceeding.

Support to consumers in response to COVID-19 included distribution of an additional 5 kg of food grains per person and 1 kg of pulses per household per month between April and November 2020, targeting urban and rural poor, including migrant workers.

In May 2020, the state government of Haryana restricted cultivation of rice in eight district blocks with severe water scarcity. Under a crop diversification programme, the state government decided to shift 100 000 ha of rice area to other crops, primarily maize, millet and pulses, to be procured at minimum support prices.

India banned exports of all varieties of onions between 13 September and 31 December 2020 to curb domestic supply shortages. In October 2020, India also imposed stock holding limits for retailers and wholesalers until end-2020.

Starting in May 2020, the Animal Quarantine and Certification Services (AQCS) in the Ministry of Fisheries, Animal Husbandry and Dairying, and in co-operation with the Customs authority, relaxed certain requirements in sanitary certificates and promoted processing of trade documents through the trade Single Window. This aimed to streamline border processes for imports of selected agro-food products, including milk and dairy products.

Due to a combination of restrictive domestic marketing policies and border measures, for many products and over most of the period reviewed, Indian farmers have been receiving prices lower than those prevailing on international markets. The central government should work closely with states and Union Territories (UTs) in implementing the domestic marketing reforms initiated in 2020 in the context of COVID-19. This can build on progress already made by many states through the electronic National Agricultural Market (e-NAM) set up in 2016 and the 2017 model Agricultural Produce and Livestock Marketing (Promotion and Facilitation) Act. Marketing reforms should be adopted in a harmonised and consistent way across states and synchronise through coherent plans with reforms to the minimum support price system. Marketing reforms can foster more efficient markets and competitive agro-food supply chains across states. They need to be complemented, however, with investments in infrastructure, marketing, training and other general services to agriculture for farmers to reap the benefits in productivity and income. Several programmes initiated during the COVID-19 pandemic, and the earmarked budgetary allocations for rural infrastructure in the 2021 Union Budget, are positive steps in this direction.

The large share of employment in agriculture compared to its GDP contribution reflects the persistent productivity gap with other sectors and translates into low farm incomes. In the short to medium term, direct cash transfers to incomes of the poorest farmers can support their livelihoods as well as the adjustment to new market conditions. Such developments were enhanced through the direct income transfer programme PM-KISAN. In the long term, significant structural adjustments need to occur in a post-COVID-19 environment, including the transition of farm labour to other activities and consolidation towards sufficiently large farm operations to benefit from economies of scale. Policies need to facilitate this transition and continued reforms in land regulations need to be complemented by investments in key public services to the sector (such as education, training and infrastructure) and the broader enabling environment (including financial services).

India is an important exporter in a number of agro-food markets. The Agricultural Export Policy (AEP) framework adopted in 2018 was important to reduce uncertainty and transaction costs throughout supply chains, as it helps avoid export restrictions on organic and processed agricultural products. However, recent export restrictions on products such as onions directly affect India’s reliability as a supplier and exacerbate farm revenue losses. An extension of the AEP to avoid export restrictions on any agro-food products should be considered to create a stable and predictable market environment.

Further reducing tariffs and relaxing other import restrictions is also key for a predictable market environment, to exploit imports’ potential to contribute to diversification of diets, and to improve food security across all its dimensions. Together with domestic marketing reforms, moving away from export and import restrictions can provide farmers and private traders with incentives to invest in supply chains.

India’s Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) includes an economy-wide emission intensity reduction target, but no sector-specific targets. Policy efforts to mitigate greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions in agriculture concentrate around pilot projects for lower methane emission rice production, increased fertiliser efficiency, and soil health improvement. Possible savings from continued back-scaling of variable input subsidies (fertiliser, irrigation water and electricity) could be applied to train farmers to use such inputs more efficiently and sustainably by ensuring that extension systems focus on climate change, sustainability and digital skills. Rebalancing the support portfolio towards more investments in the agricultural knowledge system and knowledge transfer through FPOs is also needed to ensure sustained and sustainable productivity growth.

India made significant progress in recent years in eliminating inefficiencies in the food distribution system, and these efforts should continue. The government of India should continue the experimental replacement of physical grain distribution by direct cash transfers, and expand and adjust in light of experiences gained.

Overview of policy trends

Food security was an important objective of agricultural and trade policy since India’s independence in 1947. Food shortages in the early 1960s made crop productivity and farm output a key policy ambition. Although scope to further expand the area under cultivation was limited, the advent of the “green revolution” in the mid-1960s raised crop productivity through improved technologies and seed varieties. This was accompanied by expanded extension services and increased use of fertilisers, pesticides, and irrigation.

The government of India introduced several marketing regulations affecting the sale, stocking and trading of agricultural commodities. The Essential Commodities Act (ECA) introduced in 1955 provided for the control of production, supply, distribution, and pricing of essential commodities. During the 1960s and 1970s, most states also enacted and enforced Agricultural Produce Markets Regulation (APMR) Acts, with the first point sale of agriculture produce occurring at regulated market yards (mandis) under the ambit of Agricultural Produce Market Committees (APMC). Two institutions key to prices and distribution of wheat and rice were set up in 1965, namely the Food Corporation of India (FCI) and the Agricultural Prices Commission, later renamed the Commission for Agricultural Costs and Prices (CACP). The complex domestic marketing regulations and border measures increasingly penalised producers through gaps between international prices and those received by Indian farmers.

In the 1970s, government programmes encouraged increased production and processing of milk at three different levels: (1) at the farm-level, dairy farmers were organised into co-operatives and provided with advanced technologies, such as modern animal breeds that produced more milk; (2) at the district level, co-operative unions formed, which owned and operated milk processing plants as well as storage and transport equipment, and also provided animal health services; (3) at the state level, state federations conducted and co-ordinated the nation-wide marketing of milk. Government funding for agricultural research and extension increased, and many State Agricultural Universities (SAU) were set up. Institutional lending to farmers expanded by directing commercial banks (nationalised from 1969) to provide credit to agriculture. New financial institutions were established, such as the National Bank for Agriculture and Rural Development (NABARD) in 1982 and regional rural banks. Import competition was highly restricted in order to allow domestic agricultural production to increase.

In the 1980s and 1990s, yield-enhancing “green revolution” techniques expanded to additional regions and crops such as pulses, oilseeds and coarse grains. Policy reforms were carried out in the rest of the economy, such as delicensing1 and deregulation in the manufacturing sector, but they largely bypassed agriculture, partly because of the prevalence of state regulations in agriculture. From 1980 to 1999, budgetary support to agriculture increased more than tenfold.

The National Agricultural Policy (NAP), formulated in 2000, set a priority on cropping intensity on existing agricultural land, developing rural infrastructure that supports all rural activities and developing and disseminating agricultural technologies. The National Policy for Farmers (NPF), approved in 2007, identified a need to focus more on the economic well-being of farmers rather than just on production.

The eleventh five-year plan, covering 2007-12, focused on bringing technology to farmers, improving the efficiency of investments, and improving access for the poor to land, credit and skills as well as addressing water management concerns. The twelfth five-year plan, for 2012-17, was articulated around expenditure on agriculture and on infrastructure along with an aim to improve the functioning of markets, more efficient use of natural resources, and governance in terms of institutions delivering services such as credit and animal health.

The 2012-17 plan took forward the Targeted Public Distribution System (TPDS) reforms that started in 1997. The plan recognised the need to reduce TPDS leakages (the grain released from government stocks for distribution under the PDS that did not reach beneficiaries) and suggested redirecting some food subsidies to other welfare schemes in order to achieve better targeting towards the poor, moving towards policies that are specific to individual states or areas, and redefining “poor” for the purpose of the TPDS. The 2013 National Food Security Act (NFSA) further addresses these concerns.

As of 2018, five-year plans were replaced by a framework of three-year action agendas, prepared by the National Institution for Transforming India (NITI Aayog, the erstwhile Planning Commission of India) a policy think-tank of the government of India). In 2016, the central government set the target of doubling farmers’ income by 2022-23. The central government approved the Agriculture Export Policy framework in December 2018 with the objectives of doubling agricultural exports by 2022-23 and boosting the value-added of agricultural exports.

Concerns around highly fragmented markets, inadequate physical marketing infrastructure, insufficient remuneration to farmers and high intermediation costs led the central government to suggest gradual amendments to marketing regulations under the Agricultural Produce Market Committee (APMC) Acts in 2003, 2007 and 2017. While shared with state governments as a recommendation for adoption, implementation of agricultural marketing reforms remained highly differentiated across India’s states. In June 2020, the government initiated reforms to domestic agricultural marketing regulations as part of the COVID-19 support package.

Over the past two decades, producer support was composed of negative market price support (MPS), and budgetary allocations, including almost exclusively input subsidies. India’s percentage PSE fluctuated markedly, registering a high of zero in 2000, a low of -31% in 2007, followed by large swings before stabilising in recent years (Figure 13.4). These variations were driven primarily by changes in the relative levels of domestic and international prices underlying MPS, while input subsidies followed a more steadily increasing trend. The particularly large absolute size of negative MPS in 2011-13 (and to some extent in 2007 and 2008) coincides with periods of high international commodity prices not or only partially transmitted to the domestic market, due at least in part to India’s use of export-impeding measures. (For example, export restrictions or export bans applied in several of those years to wheat, non-basmati rice, certain chickpeas, sugar and milk.) The negative value of the PSE reflects that, on average, domestic producers were implicitly taxed, as the increasing budgetary payments to farmers did not offset the price-depressing effect of complex domestic regulations and trade policy measures. Absolute levels of producer support became less negative since 2018, largely driven by higher budgetary allocations to the direct income transfer programme PM-KISAN.

Main policy instruments

Policies directly relating to agriculture and food in India consist of six major categories: (1) managing prices and marketing channels for many farm products; (2) making variable farm inputs available at government-subsidised prices; (3) providing general services for the agricultural sector as a whole; (4) making certain food staples available to selected groups of the population at government-subsidised prices; (5) regulating border transactions through trade policy; and more recently, (6) a farmer welfare focus through the income support scheme PM-KISAN. In addition, environmental measures concerning agriculture have gained prominence (OECD/ICRIER, 2018[1]; ICRIER, 2020[2]; Gulati, Kapur and Bouton, 2020[3]).

States have constitutional responsibility for many aspects of agriculture, but the central government plays an important role developing national approaches to policy and providing the necessary funds for implementation of programmes at state level. The central government (Union Cabinet) is responsible for some key policy areas, notably international trade policies, and for implementation of the National Food Security Act (NFSA) of 2013.

Policies that have been governing the marketing of agricultural commodities in India – from the producer level to downstream levels in the food chain – include the national Essential Commodities Act (ECA) and the state-level APMC Acts. Through these acts, producer prices are affected by regulations influencing pricing, procuring, stocking, and trading of commodities. Farmers bring their produce to sell in regulated wholesale markets (or mandis). This infrastructure is also used by governments to procure under the minimum support price system. Differences exist among states in the status of their respective APMC Acts and in how these acts are implemented.2 The electronic portal (electronic National Agricultural Market, e-NAM) set up in 2016 and the 2017 model Agricultural Produce and Livestock Marketing (Promotion and Facilitation) Act were shared with state governments as a recommendation for adoption.3 In June 2020, changes to domestic agricultural marketing regulations were initiated as part of the COVID-19 economic support package.

Based on the recommendations of the CACP, the central government establishes a set of minimum support prices (MSP) for 23 commodities each year. The CACP recommends the MSPs based on the India average costs of production at two levels: actual paid out costs of production (A2); and the imputed value of family labour. State governments can also provide a bonus payable over and above the MSP for some crops. National and state-level agencies operating on behalf of the Food Corporation of India (FCI) can buy wheat, rice and coarse grains as well. A number of other agencies can buy pulses, oilseeds and cotton at MSP – including through the Pradhan Mantri Annadata Aay Sanrakshan Yojna (PM-AASHA) programme introduced in 2018 – and some horticulture commodities without MSP are also procured. However, procurement under the price support scheme effectively operates mainly for wheat, rice and cotton, and only in a few states.

The only payments based on output concern the sugar sector and were introduced in 2018. The payments support clearing of arrears for sugar cane delivered and are directly provided to sugar cane farmers.

On the input side, major policies enable agricultural producers to obtain farm inputs at subsidised prices. Policies governing the supply of fertilisers, electricity and water provide the largest input subsidies. Other inputs are also supplied at subsidised prices, including seeds, machinery, credit, and crop insurance. In recent years, state-level loan debt waivers increased significantly, with local governments compensating lending institutions for forgiving debt to farmers. More than 70% of agricultural loans are from financial institutions such as commercial banks, with the rest stemming from non-institutional sources (e.g. moneylenders) (Reserve Bank of India, 2019[4]).

The Pradhan Mantri Kisan Samman Nidhi (PM-KISAN) scheme provides an annual direct income transfer of INR 6 000 (USD 84) per farmer to all farmers with land titles. The unconditional payment does not require farmers to produce, and targets farmers’ broad needs, from the purchase of inputs to needs unrelated to farming.

Programmes targeting the development and maintenance of infrastructure, particularly related to irrigation, attract the largest financial support within general services to agriculture. Budgetary support is also significant for public stockholding and for agricultural knowledge and innovation.

Public distribution of food grains operates under the joint responsibility of the central and state governments. The Targeted Public Distribution System (TPDS) operates under the NFSA in all states and UTs. Other Welfare Schemes (OWS) also operate under the NFSA. The central government allocates food grains to state governments and the FCI transports food grains from surplus states to deficit states. State governments are then responsible for distributing the food grain entitlements: allocating supplies within the state, identifying eligible families, issuing ration cards, and distributing food grains mainly through Fair Price Shops.

India’s Foreign Trade Policy, formulated and implemented by the Directorate General of Foreign Trade (DGFT), is announced every five years, but reviewed and adjusted annually in consultation with relevant public agencies. Amidst the COVID-19 outbreak, in March 2020 the central government extended the application of the current Foreign Trade Policy 2015-20. India’s Basic Customs Duty (BCD), also known as the statutory rate, is agreed at the time of the annual budget approval.

For several decades, India managed its agricultural exports through a combination of export restrictions, including export prohibitions, licensing requirements, quotas, taxes, minimum export prices,4 and state trading requirements. The application or elimination of such restrictions can change several times per year, taking into account concerns about domestic supplies and prices.

Regarding export subsidisation in agriculture, the Agricultural and Processed Food Products Export Development Authority (APEDA), under the responsibility of the Ministry of Commerce and Industry (MOCI), in recent years provides financial assistance to exporters in the form of transport support.5

The 2018 Agriculture Export Policy framework includes three main areas for action. First, ensuring that processed agricultural products and organic products not be subject to export restrictions. Second, undertaking consultations among stakeholders and Ministries in order to identify the essential food security commodities to which export restrictions could still be applied under specific market conditions. Third, reducing import barriers applied to agricultural products for processing and re-exporting.

India ratified the Paris Agreement on Climate Change on 2 October 2016, with its Intended Nationally Determined Contribution (INDC) submitted a year earlier becoming its NDC. The NDC includes a commitment to reduce the emissions intensity of GDP by 33-35% below 2005 levels by 2030, but specifies that this commitment does not bind India to any sector-specific mitigation obligation (Climate Action Tracker, 2018[5]).

With regard to agriculture, India’s NDC has a strong focus on climate change adaptation, as addressed in several of the central government’s main programmes for agriculture (entitled “missions”). These include, among others, the National Mission for Sustainable Agriculture; the Paramparagat Krishi Vikas Yojana mission promoting organic farming practices; the Pradhan Mantri Krishi Sinchayee Yojana mission promoting efficient irrigation practices; and the National Mission on Agricultural Extension & Technology.

Domestic policy developments in 2020-21

The most important domestic policy development during 2020 relates to the reforms initiated to domestic marketing regulations as part of the May 2020 COVID-19 economic support package (see details below in ‘Domestic policy developments relating to COVID-19’).

The central government has been fast tracking the integration of the e-National Agriculture Market (e-NAM) with Farmer Producer Organisations (FPOs) and warehouses. Starting August 2020, e-NAM connects farmers, FPOs, traders and warehouses with the mobile application Kisan Rath listing transporters available for moving products from farm gate to wholesale markets. The new E Gopala app provides livestock farmers with information relating to cattle health and diet (ICRIER, 2021[6]).

The government set up a high-level committee in September 2020 to prepare a roadmap for improving the legal framework on land leasing, headed by the Secretary of the Department of Land Resources within the Ministry of Rural Development. The roadmap focuses on formalising lease arrangements and addressing ceiling restrictions on landholdings to allow small farmers to expand the size of their operational holdings. In addition, it aims to ensure that direct income transfers and other welfare benefits reach farm workers who do not own any land6 (Economic Times, 2020[7]).

In June 2020, the central government increased the minimum support price (MSP) for several kharif crops (spring sown, winter harvested): for instance, the MSP was increased by 3% for paddy rice to INR 18 680 (USD 256) per tonne, by 5% for maize to INR 18 500 (USD 245) per tonne, and by 5% for soybeans to INR 38 800 (USD 514) per tonne. The MSPs for cotton medium and long staple were also increased by 5% to INR 55 150 (USD 756) per tonne and INR 58 250 (USD 798) per tonne, respectively.

In August 2020, the Fair and Remunerative Price for sugarcane was also increased for marketing year 2020/21 by 4% to INR 2 850 (USD 40) per tonne for a recovery rate of 10%. There was also an approved premium of INR 28.8 (USD 0.4) per tonne for higher productivity7 (Government of India, 2020[8]).

In addition, in September 2020 the government raised MSPs for six rabi crops (winter sown, spring harvested). To encourage planting of pulses and oilseeds, the highest increases in the MSP were introduced for lentils by 6.3% to INR 5 100 (USD 70) per tonne, by 4.6% for chickpeas to INR 5 100 (USD 70), and by 5% for rapeseed and mustard to INR 4 650 (USD 64) per tonne. The MSP for wheat was increased by 2.6% to INR 1 925 (USD 26) per tonne (Government of India, 2020[9]).

In November 2020, the Ministry of Finance earmarked an additional INR 1.34 trillion (USD 18 billion) for fertiliser subsidies for 2020-218, in spite of a prior February 2020 government decision to reduce the fertiliser subsidies (AMIS, 2020[10]).

The government of India allocated in 2020 INR 2.8 billion (USD 38 million) for the formation and training of 10 000 FPOs. The 2021 Union Budget for the agricultural sector presented in February 2021 an amplified focus on infrastructure, with a 33% increase in the allocation to rural infrastructure development for 2021.

On agri-environmental policies, in May 2020, the state government of Haryana restricted the cultivation of rice in eight district blocks with severe water scarcity. Under its crop diversification programme, the state government decided to shift 100 000 hectares of rice area to other crops, primarily maize, millet and pulses that will be procured at MSP. Farmers shifting their production are provided with a payment of INR 7 000 per acre (USD 237 per hectare) of area under new crops (Down to earth, 2020[11]).

As of March 2021, 32 states and UTs implement the “One nation, one ration card” programme under the Targeted Public Distribution System. The “One nation, one ration card” programme aims to address the difficulties of migrant beneficiaries who often cannot access the subsidised food grain quota due to the change in residence for employment purposes. Other objectives of the programme are to better target beneficiaries and reduce leakage by biometric authentication of beneficiaries, as well as automation of Fair Price Shops (FPS) (Government of India, 2021[12]).

The food subsidy allocation increased from INR 1.15 trillion (USD 13 billion) in the 2020-21 budget estimate to INR 4.22 trillion (USD 48 billion) in the revised budget estimates, reflecting the additional cost of free food grain distribution in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic (see details below), as well as the government’s decision to pay the Food Corporation of India’s (FCI) loans9 and return to budgetary transfers to fund the food subsidy cost. The 2021 Union Budget also proposes to discontinue the National Small Savings Fund (NSSF) loan to FCI for food subsidy (The Hindu, 2021[13]).

On 30 November 2020, India announced it plans to achieve 20% ethanol-blending with gasoline (E20, i.e. 20% of ethanol mixed with 80% of gasoline) by 2025, five years ahead of its previous target set in 2019, to reduce its dependence on oil imports. To meet the new 2025 target, the government announced that 12 billion litres of ethanol would be needed, with 7 billion litres of ethanol produced from 6 million tonnes of surplus sugar and 5 billion litres of ethanol from excess grain. In addition, the government introduced an interest subsidy scheme of INR 45 billion (USD 626 million) to enhance the domestic ethanol distillation capacity from rice, maize, sorghum, wheat, and barley (Reuters, 2021[14]; AMIS, 2021[15]).

The government of India is setting up a common data infrastructure with information on all farmers in the country, integrating data from food subsidies recipients, the direct income transfer programme PM-KISAN, and the Soil Health Card (ICRIER, 2021[6]).

The National Bank for Agriculture and Rural Development (NABARD) earmarked INR 50 billion (USD 683 million) for 2021 for transforming Primary Agricultural Credit Societies (PACS) into multi-service centres or one-stop shops for receiving technical assistance (ICRIER, 2021[6]).

Domestic policy responses to the COVID-19 pandemic

In March 2020, the Ministry of Agriculture and Farmers’ Welfare (MAFW) launched new features of the electronic National Agriculture Market (e-NAM) platform to address difficulties with physically travelling to APMC mandis markets for selling crops. The features included: (i) a warehouse-based trading module to facilitate trade directly from warehouses based on e-Negotiable Warehouse Receipts (e-NWR); (ii) a Farmer Producer Organisation (FPO) trading module whereby FPOs can trade their produce from their respective collection centre without bringing the produce to APMC markets (Government of India, 2020[16]).

Several measures were aimed at limiting transportation disruptions and delays in supply chains. For instance, on 25 March 2020, the Ministry of Home Affairs issued a notice information to states and UTs that transportation of animal feed and fodder was considered an essential service and would thus be exempted from any inter-state restriction under the 2005 Disaster Management Act (Government of India, 2020[17]). The relaxed norms for agriculture-related activities under the lockdown also allow for the inter-state movement of harvesting and sowing machinery (Times of India, 2020[18]). In addition, Indian Railways set up special railway parcel trains for the transportation of essential items, including food products, in small parcel sizes (Government of India, 2020[19]).

Central and state level governments have been making efforts to maintain the operation of distribution channels for fruit and vegetables. States such as Odisha set up ‘vegetable counters’ as an alternative channel of distribution in addition to providing support to small farmers for selling their produce in district and urban centres (Deccan Herald, 2020[20]).

In March 2020, the central government granted the 3% prompt repayment incentive (PRI) to all farmers for all short-term crop loans of maximum INR 300 000 (USD 3 938) which are due up to 31 May 2020, even if farmers fail to repay loans until this date (Government of India, 2020[21]).

Support to agriculture is also part of the May 2020 INR 18.3 trillion10 (USD 250 billion) special economic package to recover from the COVID-19 pandemic and achieve a ‘self-reliant’ India. First, several of the economy-wide measures within the package such as easing the liquidity pressure for small enterprises or Non-Banking Financial Institutions (NBFI) also concern agri-businesses. Second, the specific agro-food support package within the overall May 2020 package has several components:

fiscal support to infrastructure and other general services programmes

reforms to domestic agricultural marketing regulations to provide farmers with a better price discovery mechanism and to enhance private sector investment in supply chains.

The fiscal support to migrant workers backs the creation of new public works for migrants returning to rural areas from urban areas affected by the COVID-19 lockdown. The programme allocated INR 1.15 trillion (USD 16 billion) to the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MNREG), including payments covering working hours in rural infrastructure projects such as micro-irrigation systems.

Fiscal support for enhancing financial services includes INR 300 billion (USD 4 billion) for 30 million farmers, within the Additional Emergency Working Capital for Farmers implemented by the National Bank for Agriculture and Rural Development (NABARD). It also includes INR 2 trillion (USD 26.3 billion) of credit for 25 million farmers under the Kisan Credit Card (KCC) scheme.

Funds destined to on farm services, agricultural infrastructure and other general services projects include several programmes (Ministry of Agriculture and Farmers' Welfare, 2021[22]):

The Agriculture Infrastructure Fund ten-year programme to support post-harvest infrastructure such as cold storage, collection centres, and processing units. Support (INR 2.1 billion (USD 29 million) in 2020) is to be provided as interest subsidy to credits for the set-up of these types of infrastructure. Beneficiaries include farmers, farmer producer organisations (FPOs), and agri-businesses.

INR 100 billion (USD 1.32 billion) scheme to assist 200 000 micro agro-food enterprises to upgrade food standards and product marketing.

INR 133.4 billion (USD 1.75 billion) outlay for the National Disease Control Program to address foot and mouth disease and brucellosis by vaccinating 530 million animals (cattle, buffalos, sheep, goats, and pigs).

INR 150 billion (USD 1.97 billion) for the Animal Husbandry Infrastructure Development Fund to support private investment in dairy processing and cattle feed infrastructure.

With the objective to avoid COVID-19 spread in mandis after India entered lockdown in March 2020, APMC laws were suspended and transactions could be undertaken in places outside the mandi system. This encouraged the central government to initiate reforms to domestic agricultural marketing regulations in June 2020 as part of the May 2020 COVID-19 support package, under the strategy ‘One India, one agriculture market’ (ICRIER, 2021[6]). The proposed reforms included a set of ordinances aiming to: deregulate major food crops from the 1955 ECA; allow farmers to sell their agricultural products outside of government-regulated markets; and allow barrier-free inter and intra-state trade of agricultural commodities. The government also proposed providing a legal framework for farmers to facilitate contract-farming schemes with processors and other market actors in supply chains in order to reduce price risk.

On 20 September 2020, the Indian Parliament passed the following Acts in support of the proposals:

The Essential Commodities (Amendment) Act, which would remove limits on private stocking, trading or buying of several commodities, including cereals and oilseeds.

The Farmers’ Produce Trade and Commerce (Promotion and Facilitation) Act, which would allow farmers to sell their produce in other places in addition to markets notified under state Agricultural Produce Market Committee (APMC) Acts (mandis). The act proposes to set up an electronic trading platform and a dispute resolution mechanism. It would also promote barrier-free inter-state and intra-state trade.

The Farmers’ (Empowerment and Protection) Agreement on Price Assurance and Farm Services Act, which would create a national framework for contract farming through an agreement between a farmer and a private sector buyer (i.e. processor, wholesaler, retailer, exporter) for the sale of future farm produce. The act provides for a three-level dispute settlement mechanism by the conciliation board, Sub-Divisional Magistrate, and Appellate Authority as the highest level of appeal.

Major protests of farmers from several states demanding the repeal of the bills11 led the central government to consider potential amendments.12 In mid-December 2020, India’s Supreme Court suspended the implementation of the bills and mandated the creation of an expert committee to consult with farmer groups before proceeding with their implementation (Business Standard, 2021[23]).

The central government introduced support to consumers in March and June 2020. On 18 March 2020, the government of India decided to distribute a six-month quota of subsidised food grains in one go to beneficiaries under the TPDS, with the objective to prevent eventual panic buying under the COVID-19 lockdown and potential price increases (Economic Times, 2020[24]). On 26 March 2020, the government approved the free distribution of an additional 5 kg of food grains per person13 and 1 kg of pulses per household (according to regional preferences) per month for three months under the programme Pradhan Mantri Garib Kalyan Ann Yojana (Prime Minister’s Food Security Scheme for the Poor) targeting urban and rural poor, including migrant workers (Government of India, 2020[25]). In June 2020, the programme was extended until November 2020 (AMIS, 2020[26]).

In addition, in March-April 2020, specific state- or UT-level initiatives also targeted distribution of grains and other food products. Some of these include the following (IFPRI, 2020[27]):

States such as Andhra Pradesh, Chhattisgarh, Delhi, Gujarat, Karnataka, Maharashtra, Manipur, Odisha, Punjab, Uttar Pradesh, Tamil Nadu, Telangana, and West Bengal are providing additional quantities of wheat and rice (between 1 kg and 10 kg per month for varying periods and for different categories of households).

States such as Andhra Pradesh, Gujarat, Haryana, Karnataka, Odisha, Punjab, and Tamil Nadu are also providing other agro-food products such as pulses, oil, salt, or sugar.

Trade policy developments in 2020-21

On 28 March 2020, the Ministry of Commerce and Industry (MOCI) extended the existing quantitative import restriction for dried peas until end March 2021. Restrictions include an import quota of 150 000 tonnes per year, Minimum Import Prices (MIPs) of INR 200 (USD 2.7) per kg14 and a requirement of clearing all pea imports only through the port of Kolkata. On 16 April 2020, MOCI fixed the quantity of peas by type that can be imported under the quantitative restriction at 75 000 tonnes for green peas and 75 000 tonnes for other peas (but setting the quantity allowed for yellow peas at 0 tonnes, imposing a de facto import ban) (DGFT, 2020[28]) (WTO, 2020[29]).

In turn, the most favoured nation (MFN) tariff for lentils,15 from all origins except the United States, was reduced between June and December 2020 from 30% to 10%. The tariff on lentils from the United States was reduced from 50%16 to 30%.

The government also allowed imports of 0.2 million tonnes of pigeon peas and other pulses from Mozambique outside the quota limits for these pulses in 2020-21, under the existing Memorandum of Understanding between the two governments.

In April 2020, India notified the WTO that it exceeded its limit on rice support for marketing year 2018/19, invoking for the first time the ‘peace clause’.17

The Ministry of Commerce and Industry (MOCI) banned exports of all varieties of onions between 13 September and 31 December 2020 to curb domestic supply shortages18 (Hindustan Times, 2020[30]; Economic Times, 2020[31]). In mid-October 2020, the MOCI also imposed stock holding limits, in place until 31 December 2020: 2 tonnes for retailers and 25 tonnes for wholesalers (Economic Times, 2020[32]). In turn, to facilitate imports of onion and address domestic shortages, the government relaxed the requirements for fumigation and related declarations on the Phytosanitary Certificate (PSC) necessary for importation, for the period October 2020 to January 2021.

In May 2020, the central government launched the Rice Export Promotion Forum (REPF). The Forum seeks to help traders boost rice exports under the supervision of the Agricultural and Processed Foods Export Promotion Development Authority (AMIS, 2020[33]).

In October 2020, the Gujarat state government approved, export subsidies for skimmed milk powder (SMP) until 30 April 2021. The programme provides a total of INR 1.5 billion (USD 20 million) for six months and for a maximum amount of 30 000 tonnes of SMP to the Gujarat Cooperative Milk Marketing Federation Ltd. The export subsidy provides INR 50 (USD 0.7) per kg of SMP exported if the FOB price is above INR 180 (USD 2.5) per kg (GAIN IN2020-0153, 2020[34]).

In December 2020, the central government approved a subsidy of INR 35 billion (USD 480 million) to sugar mills for the export of 6 million tonnes of sweetener during the marketing year 2020/21, as part of the efforts to help mills clear outstanding dues to sugar cane farmers (Times of India, 2020[35]).

In December 2020, the government launched a digital interface for foreign investors to connect directly with farmers (Economic Times, 2020[36]).

The Union Budget 2021 presented early February 2021 introduces the Agriculture Infrastructure and Development Cess (AIDC) (i.e. levy) on selected imported goods for financing agricultural infrastructure programmes, including the following agro-food products: 17.5% on crude palm oil; 35% on apples; 5% on cotton; 40% on peas; 20% on lentils; and between 30% and 50% on selected types of chickpeas. Also in February 2021, the MFN tariff for cotton was raised from 0% to 5%.

Trade policy responses to the COVID-19 pandemic

The Ministry of Shipping issued specific guidelines to main ports applying from 22 March to 14 April 2020 on exemptions and reductions of penalties, demurrages charges, and other port fees for traders in relation to any potential delay in cargo port operations (Government of India, 2020[37]). At the same time, port protocols were adjusted, ranging from quarantine measures to additional documentation requirements and examinations, while at the end of March 2020 ports were advised by the Ministry of Shipping that they could consider the COVID-19 pandemic as grounds for invoking ‘force majeure’, a clause absolving companies from meeting their contractual commitments for reasons beyond their control (Bloomberg, 2020[38]).

On 27 March 2020, the central government extended the 2015-20 Foreign Trade Policy that was due to expire and be replaced by the Foreign Trade Policy 2020-25 (Business Standard, 2020[39]).

Starting May 2020, the Animal Quarantine and Certification Services (AQCS) in co-operation with the Customs authority relaxed certain requirements in sanitary certificates and promoted processing of trade documents through the trade Single Window. This has the objective of streamlining border processes for imports of selected agro-food products (including milk and dairy products) (GAIN IN2020-0126, 2020[40]).

India is the seventh largest country by land area and the second most populous after the People’s Republic of China with over 1.3 billion people (Table 13.3). While the share of urban population continued to increase over the past decade, about two-thirds of the population still live in rural areas. At just 0.15 hectare per capita, agricultural land is very scarce.

Agriculture accounts for an estimated 42.4% of employment, but its 16% share in GDP indicates that labour productivity remains significantly lower than in the rest of the economy. The productivity gap is also reflected in the evolution of farm incomes, which correspond to less than one-third of non-agricultural income. Agriculture’s weight in the economy has gradually declined, mostly in favour of services which led economic growth over the last two decades and played a more important role in India’s economic development than in most other major emerging economies.

Indian agriculture is continuing to diversify towards livestock and away from grain crops. While grains and milk remain dominant, there has been a gradual change in the composition of production to other crops – such as sugar cane, cotton, fruit and vegetables – as well as certain meat sub-sectors. The livestock sector has seen faster and less volatile growth than the crop sector. The agricultural sector continues to be dominated by a large number of small-scale farmers, as the national average operational holding size has been in steady decline.

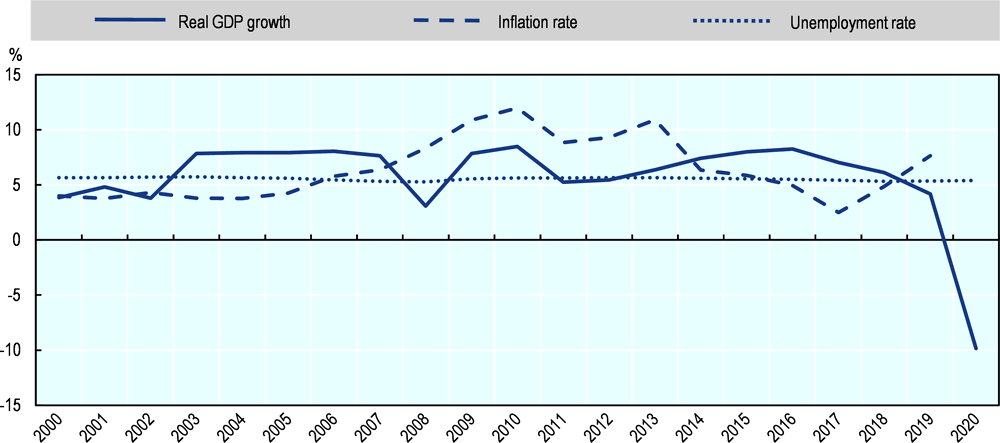

Real GDP growth was decelerating prior to 2020 (5.8% in 2019), highlighting remaining structural bottlenecks in areas such as labour markets or the business environment. The COVID-19 pandemic and related restrictions led to a drop in GDP of about 10%. The low unemployment figures (averaging 5.4% in 2018-20) hide significant degrees of informal employment. Against the background of higher prices for selected food items, inflation increased to 9% in 2019 (Figure 13.5).

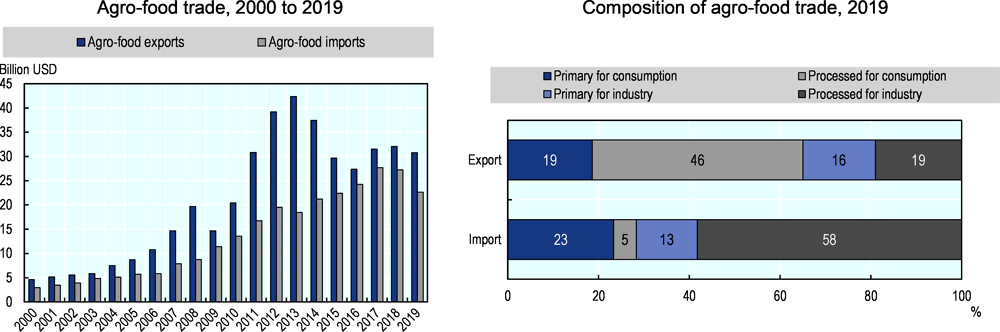

India has consistently been a net agro-food exporter over the last two decades, but agro-food imports have been increasing since 2007, while exports have declined from the peak of 2013. Products for direct consumption – of low value, raw or semi-processed, and marketed in bulk – dominate agro-food exports, representing 65% of the total in 2019. Processed products for further processing by domestic industry are the main import category, accounting for 58% of total agro-food imports (Figure 13.6).

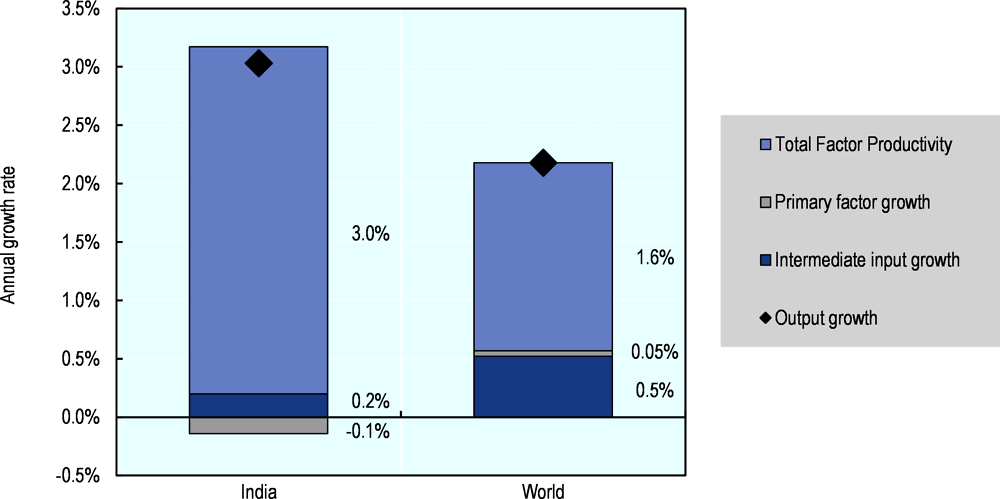

Agricultural output growth in India averaged 3% in 2006-15, well above the world average (Figure 13.6). This has been driven mainly by a significant increase in total factor productivity (TFP) at 3% per year, backed by technological progress in the form of improved seeds and better infrastructure (including irrigation coverage, road density, and electricity supply).

However, the sustained growth in agricultural output has been exerting mounting pressures on natural resources, particularly land and water. This is reflected in the nutrient surplus intensities at the national level, which are much higher than the average for OECD countries. The share of agriculture in total greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions is also higher than the OECD average, partly due to the weight of the agricultural sector in the Indian economy. Livestock rearing is the main source of GHGs (Table 13.3).

References

[15] AMIS (2021), AMIS Market Monitor Issue 85.

[33] AMIS (2020), AMIS Market Monitor Issue 79, June.

[26] AMIS (2020), AMIS Market Monitor Issue 81, August.

[10] AMIS (2020), AMIS Market Monitor Issue 84, December.

[38] Bloomberg (2020), Indian Ports In Confusion as Virus Lockdown Hits Operations, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2020-03-25/indian-ports-declare-force-majeure-amid-national-virus-lockdown (accessed on 10 April 2020).

[23] Business Standard (2021), Supreme Court order on farm laws, https://www.business-standard.com/article/opinion/supreme-court-order-on-farm-laws-none-to-praise-and-very-few-to-love-it-121011500390_1.html (accessed on 18 January 2021).

[39] Business Standard (2020), Foreign Trade Policy and Schemes to Be Extended for 6 Months, https://www.business-standard.com/article/economy-policy/foreign-trade-policy-schemes-to-be-extended-by-6-months-till-sept-30-120032701005_1.html (accessed on 31 March 2020).

[5] Climate Action Tracker (2018), Countries: India, http://climateactiontracker.org/countries/india.html (accessed on 15 January 2019).

[20] Deccan Herald (2020), Coronavirus: Self-help Groups in Odisha, https://www.deccanherald.com/national/east-and-northeast/coronavirus-self-help-groups-in-odisha-manufacture-distribute-1-million-masks-821618.html (accessed on 10 April 2020).

[28] DGFT (2020), Trade Notice No.6/2020-2021, https://content.dgft.gov.in/Website/TN%206.pdf (accessed on 20 February 2021).

[11] Down to earth (2020), Paddy or no paddy: Quest for equilibrium between water, livelihood in Haryana, https://www.downtoearth.org.in/blog/agriculture/paddy-or-no-paddy-quest-for-equilibrium-between-water-livelihood-in-haryana-71204 (accessed on 15 December 2020).

[36] Economic Times (2020), Amidst protests, India launches digital facility for foreign investors to connect with farmers, https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/economy/agriculture/amidst-protests-india-launches-digital-facility-for-foreign-investors-to-connect-with-farmers/articleshow/79765931.cms (accessed on 15 December 2020).

[7] Economic Times (2020), Centre sets up high-level committee to prepare roadmap for regularisation of land leasing in agri sector, https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/economy/agriculture/centre-sets-up-high-level-committee-to-prepare-roadmap-for-regularisation-of-land-leasing-in-agri-sector/articleshow/78176088.cms?utm_source=contentofinterest&utm_medium=text&utm_campaign=cp (accessed on 20 December 2020).

[32] Economic Times (2020), Government imposes stock limit on onion traders to check prices, https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/economy/agriculture/government-imposes-stock-limit-on-onion-traders-to-check-prices/articleshow/78828664.cms?from=mdr (accessed on 15 December 2020).

[41] Economic Times (2020), India considers changing new farm laws after mass protests, https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/economy/agriculture/india-considers-changing-new-farm-laws-after-mass-protests/articleshow/79569600.cms?utm_source=contentofinterest&utm_medium=text&utm_campaign=cppst (accessed on 15 December 2020).

[31] Economic Times (2020), Onion prices shoot up 28 percent after government announces easing on export ban, https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/economy/agriculture/onion-prices-shoot-up-28-percent-after-government-announces-easing-on-export-ban/articleshow/80019370.cms (accessed on 15 December 2020).

[24] Economic Times (2020), PDS Beneficiaries Can Lift 6-month Quota of Grains in One Go, https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/politics-and-nation/pds-beneficiaries-can-lift-6-month-quota-of-grains-in-one-go-ram-vilas-paswan-amid-coronavirus-concerns/articleshow/74695460.cms?from=mdr (accessed on 30 March 2020).

[40] GAIN IN2020-0126 (2020), Livestock and Products Annual, September.

[34] GAIN IN2020-0153 (2020), Dairy and Products Annual, November.

[12] Government of India (2021), Economic Survey 2020-21, https://www.indiabudget.gov.in/economicsurvey (accessed on 1 March 2021).

[8] Government of India (2020), Cabinet approves Fair and Remunerative Price of sugarcane.

[16] Government of India (2020), Finance Minister Announces Several Relief Measures, https://pib.gov.in/PressReleseDetail.aspx?PRID=1607942 (accessed on 10 April 2020).

[9] Government of India (2020), Government declares Minimum Support Prices (MSP) for Rabi Crops for marketing season 2021-22, https://pib.gov.in/PressReleasePage.aspx?PRID=1657457 (accessed on 15 December 2020).

[21] Government of India (2020), Government Gives Benefits to Farmers on Crop Loan Repayments Due to Covid-19 Lockdown, https://pib.gov.in/newsite/PrintRelease.aspx?relid=200815 (accessed on 10 April 2020).

[19] Government of India (2020), Indian Railways to Run Special Parcel Trains for Carriage of Essential Items in Small Parcel Sizes, https://pib.gov.in/newsite/PrintRelease.aspx?relid=200787 (accessed on 10 April 2020).

[37] Government of India (2020), Ministry of Shipping issues Direction to All Major Ports, https://pib.gov.in/newsite/PrintRelease.aspx?relid=200867 (accessed on 10 April 2020).

[25] Government of India (2020), Rs 1.70 Lakh Crore Relief Package under Pradhan Mantri Garib Kalyan Yojana for the Poor, https://pib.gov.in/PressReleseDetail.aspx?PRID=1608345 (accessed on 30 March 2020).

[17] Government of India (2020), Transportation/Interstate Movement of Animal Feed, https://pib.gov.in/newsite/PrintRelease.aspx?relid=200793 (accessed on 10 April 2020).

[3] Gulati, A., D. Kapur and M. Bouton (2020), Reforming Indian Agriculture.

[30] Hindustan Times (2020), Government imposes ban on onion exports, https://www.hindustantimes.com/india-news/govt-imposes-ban-on-export-of-onions/story-XqKn0RiTl1DmRGYQLmCBPM.html#:~:text=The%20Union%20government%20on%20Monday,coming%20weeks%2C%20as%20exports%20surged.&text=The%20government%20had%20lifted%20the,a%20kg%20 (accessed on 14 December 2020).

[6] ICRIER (2021), Background information for the India chapter - 2021 M&E report.

[2] ICRIER (2020), Background Analysis for the 2020 Agricultural Policy Monitoring and Evaluation Report.

[27] IFPRI (2020), How India’s Food-Based Safety Net is Responding to the COVID-19 Lockdown, https://www.ifpri.org/blog/how-indias-food-based-safety-net-responding-covid-19-lockdown (accessed on 10 April 2020).

[22] Ministry of Agriculture and Farmers’ Welfare (2021), Assistance to Farmers affected by Floods and Covid-19 Pandemic, https://pib.gov.in/Pressreleaseshare.aspx?PRID=1697514 (accessed on 25 February 2021).

[1] OECD/ICRIER (2018), Agricultural Policies in India, OECD Food and Agricultural Reviews, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264302334-en.

[4] Reserve Bank of India (2019), Report of the Internal Working Group to Review Agricultural Credit, https://www.rbi.org.in/Scripts/PublicationReportDetails.aspx?UrlPage=&ID=942 (accessed on 10 January 2020).

[14] Reuters (2021), India brings forward target of 20% ethanol-blending with gasoline, https://www.reuters.com/article/india-ethanol-gasoline-idUSKBN29J2FF (accessed on 20 January 2021).

[13] The Hindu (2021), Union Budget 2021 - Food subsidy budget set at almost INR 2.43 lakh crore, https://www.thehindu.com/business/budget/union-budget-2021-food-subsidy-budget-set-at-almost-243-lakh-crore/article33719802.ece (accessed on 2 February 2021).

[42] The Hindustan Times (2020), Kerala Assembly passes resolution demanding withdrawal of farm laws passed by Parliament, https://www.hindustantimes.com/india-news/kerala-assembly-passes-resolution-demanding-withdrawal-of-farm-laws-passed-by-parliament/story-AEciWT0mTmIfhxNuTm08vK.html (accessed on 15 January 2021).

[35] Times of India (2020), Cabinet approves INR 3500 crore sugar export subsidy, https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/business/india-business/cabinet-okays-rs-3500-crore-sugar-export-subsidy/articleshow/79761819.cms (accessed on 15 January 2021).

[18] Times of India (2020), Govt Relaxes Norms for Agriculture and Farming Sector, https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/coronavirus-lockdown-govt-relaxes-norms-for-agriculture-and-farming-sector/articleshow/74983439.cms (accessed on 10 April 2020).

[29] WTO (2020), Compilation of questions for the Committee on Agriculture meeting of 28 July 2020, https://docs.wto.org/dol2fe/Pages/SS/directdoc.aspx?filename=q:/Jobs/RD-AG/78.pdf&Open=True.

Notes

← 1. Under the industrial licensing policies in place until the early 1990s, private sector firms needed to secure specific licenses to start operating.

← 2. In the seven states or UTs that do not have an APMC act, procurement can take place outside mandis.

← 3. Agriculture marketing also covers the futures market governed by the Securities and Exchange Board of India (SEBI), with the largest value of agricultural commodity trade taking place through the National Commodity Derivative Exchange (NCDEX). In addition, the Negotiable Warehouse Receipt System (NWRS) – established under the Warehousing Development and Regulatory Authority (WDRA) – aims to support farmers by storing products in warehouses. However, farmers, especially small and marginal, do not directly trade in agri-futures market in India.

← 4. This represents the price below which exporters are not allowed to export a specific commodity. A minimum export price is set taking into consideration concerns about domestic prices and supply of that specific commodity.

← 5. A Ministerial Decision on Export Competition at the WTO Ministerial Conference held in Nairobi in 2015 put an end to the subsidisation of agricultural exports, which for India would occur at the end of 2023 (https://www.wto.org/english/thewto_e/minist_e/mc10_e/l980_e.htm).

← 6. Only landowners or farmers with legal rights to operate on land are eligible for nearly all of the existing programmes for farmers, thus excluding tenant farmers from benefitting from such schemes. The average India tenancy rate is approximately 10% of rural households, with wide regional differences.

← 7. INR 2.75 per quintal (USD 0.4 per tonne) for every 0.1% increase above the basic 10% recovery rate (i.e. defined by the Cabinet Committee on Economic Affairs as the amount of sugar produced by crushing a given amount of sugarcane by weight).

← 8. Since 2015, the government has been postponing disbursements under food and fertiliser subsidies and the steep increase in 2020 is linked to accounting clearance of past dues.

← 9. For several years, the budgetary allocation for PDS has not been sufficient to cover FCI’s subsidy costs, forcing it to borrow from the NSSF at a rate of about 8%. Its outstanding loans are now above INR 2 trillion (USD 23 billion) (The Hindu, 2021[13]).

← 10. The total economic package of INR 20 trillion (USD 263 billion) includes the INR 1.7 trillion (USD 22.3 billion) relief package introduced in March 2020 and designed to provide a safety net to India’s most economically vulnerable citizens affected by the COVID-19 lockdown.

← 11. The Kerala state Assembly passed a resolution on 31 December 2020 demanding the bills withdrawal (The Hindustan Times, 2020[42]).

← 12. One of such considerations is for applying the same taxes to the private wholesale markets outside APMC as in the existing regulated markets. Under the Farmers’ Produce Trade and Commerce (Promotion and Facilitation) Act, private players would be allowed to set up wholesale markets where transactions would not attract any kind of tax. An additional consideration is that in case of a dispute between sellers and buyers, the government could also allow farmers to appeal to a higher court than what would be permitted under the new legislation (Economic Times, 2020[41]). On 21 January 2021, farmers’ unions rejected a central government proposal to suspend the implementation of the bills for a period of 18 months while the expert committee would conduct the consultations.

← 13. This is in addition to the regular food ration quota (5 kg of wheat or rice per person per month with wheat at INR 2/kg, and rice at INR 3/kg) under the National Food Security Act (NFSA) 2013.

← 14. MIP is around six times higher than the domestic price.

← 15. HS code 07134000.

← 16. The Ministry of Finance introduced tariff increases in June 2018 on various products imported from the United States, in retaliation to the duty increases introduced by the United States on steel and aluminium.

← 17. The peace clause protects a developing country against dispute action by WTO members in case it exceeds its support ceiling because of acquisition at an administered price for public stockholding for food security purposes. India informed the WTO that the value of its rice production was USD 43.67 billion in 2018-19 and that its non-exempt rice support amounted to USD 5 billion. India also noted that the 850 000 tonnes of rice stocks subsequently sold in the domestic market were not allowed for export.

← 18. Heavy rainfall in August damaged output by 40% to 50% in key growing states of Madhya Pradesh, Karnataka and Gujarat.