Keeping The Recovery On Track

Economic growth has picked up this year, helped by strong policy support, the deployment of effective vaccines and the resumption of many economic activities.

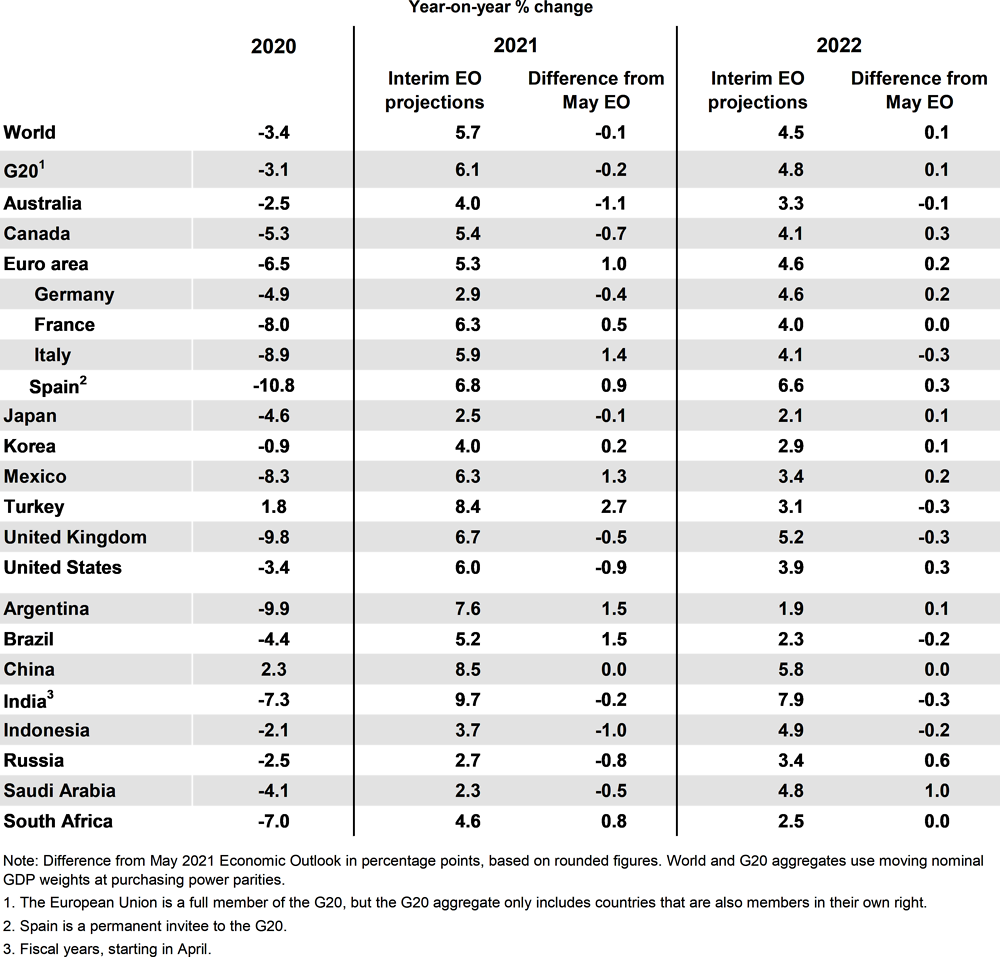

Global GDP is projected to grow by 5.7% in 2021 and 4.5% in 2022. A strong rebound in Europe, the likelihood of additional fiscal support in the United States next year, and lower household saving will boost growth prospects in the advanced economies.

Global GDP has now surpassed its pre-pandemic level, but output and employment gaps remain in many countries, particularly in emerging-market and developing economies where vaccination rates are low.

The economic impact of the Delta variant has so far been relatively mild in countries with high vaccination rates, but has lowered near-term momentum elsewhere and added to pressures on global supply chains and costs.

Inflation has risen sharply in the United States, Canada, the United Kingdom and some emerging-market economies, but remains relatively low in many other advanced economies, particularly in Europe and Asia.

Higher commodity prices and global shipping costs are currently adding around 1½ percentage point to annual G20 consumer price inflation, accounting for most of the inflation upturn over the past year.

G20 consumer price inflation is projected to moderate from 4½ per cent at the end of 2021 to around 3½ per cent by the end of 2022, remaining above the rates seen prior to the pandemic. Supply pressures should fade gradually, wage growth remains moderate and inflation expectations are still anchored, but near-term risks are on the upside.

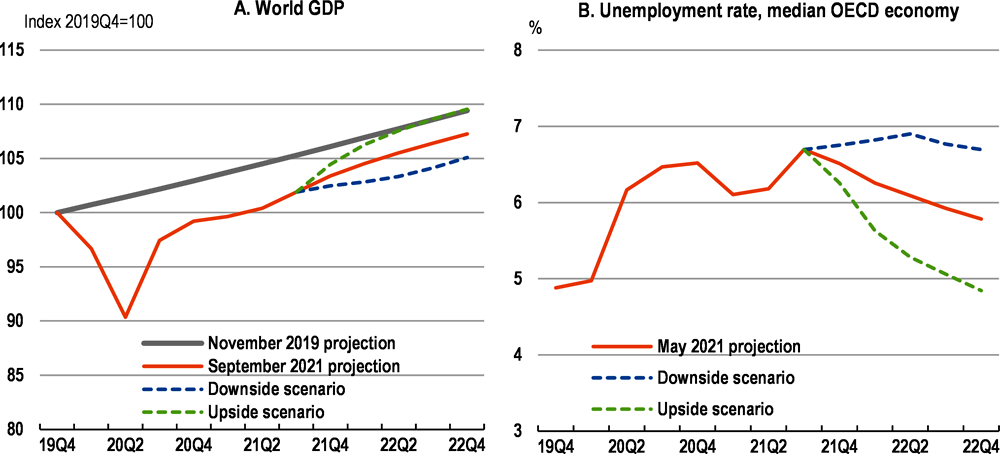

Sizeable uncertainty remains. Faster progress in vaccine deployment, or a sharper rundown of household savings would enhance demand and lower unemployment but also potentially push up near-term inflationary pressures. Slow progress in vaccine rollout and the continued spread of new virus mutations would result in a weaker recovery and larger job losses.

The difficult policy choices faced by some emerging-market economies with high debt and rising inflation are also a potential downside risk.

Governments need to ensure that all resources necessary are used to deploy vaccinations as quickly as possible throughout the world to save lives, preserve incomes and bring the virus under control. Stronger international efforts are needed to provide low-income countries with the resources needed to vaccinate their populations for their own and global benefits.

Macroeconomic policy support remains necessary whilst the near-term outlook is still uncertain and labour markets have not yet recovered, with the mix of policies contingent on economic developments in each country.

Accommodative monetary policy should be maintained, but clear guidance is needed about the horizon and extent to which any inflation overshooting will be tolerated, and the planned timing and sequencing of eventual moves towards monetary policy normalisation.

Fiscal policies should remain flexible and contingent on the state of the economy. A premature and abrupt withdrawal of policy support should be avoided whilst the near-term outlook is still uncertain.

Credible fiscal frameworks that provide clear guidance about the medium-term path towards debt sustainability, and likely policy changes along that path, would help to maintain confidence and enhance the transparency of budgetary choices.

Stronger public investment and enhanced structural reforms are needed to boost resilience, and improve the prospects for sustainable and equitable growth.

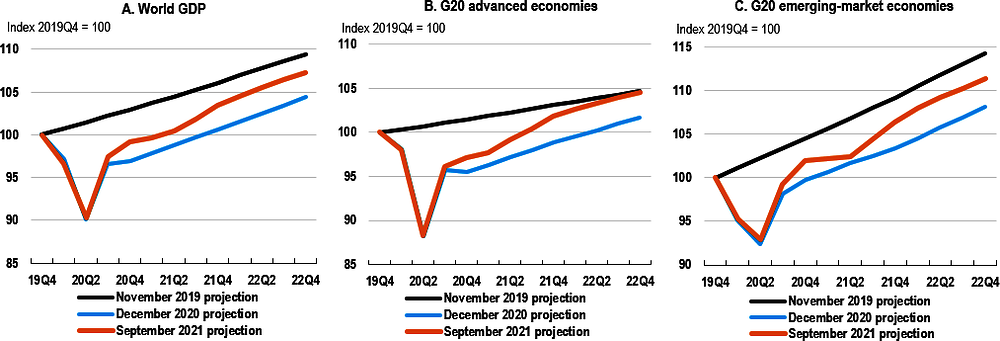

Economic growth has picked up this year, helped by strong policy support, the ongoing deployment of effective vaccines and the gradual resumption of many economic activities, particularly in service sectors. Global GDP has now surpassed its pre-pandemic level, but output in mid-2021 was still 3½ per cent lower than projected before the pandemic. This represents a real income shortfall of over USD 4½ trillion (in 2015 PPPs), and is broadly equivalent to one year of global output growth in normal times. Closing this gap is essential to minimise long-term scars from the pandemic via job and income losses.

The recovery remains very uneven, with strikingly different outcomes across countries, sectors and demographic groups in terms of output and employment (Figure 1), leaving countries facing different policy challenges. In some countries where output has returned to pre-pandemic levels, such as the United States, employment remains lower than before the pandemic. In others, particularly in Europe, employment has been largely preserved, but output and total hours worked have not yet recovered fully. Rapid rebounds in activity have occurred in a few emerging-market economies, but in some cases this has been accompanied by high inflation pressures.

Growth picked up sharply in the second quarter of 2021 in countries in which containment measures were largely eased, or where infection rates remained low, helped by strong consumer spending on services and supportive macroeconomic policies. However, high numbers of infections are still occurring due to the spread of the more transmissible Delta variant, and there are marked differences in the pace of vaccinations and the scope for policy support across countries, particularly in many emerging-market and developing economies. The Delta variant has so far had a relatively mild economic impact in countries with high vaccination rates, but there are signs that it may weigh on confidence and lower near-term growth momentum. Many countries have imposed new containment measures to check the spread of the Delta variant, particularly in the Asia-Pacific region where vaccination rates have been relatively low.

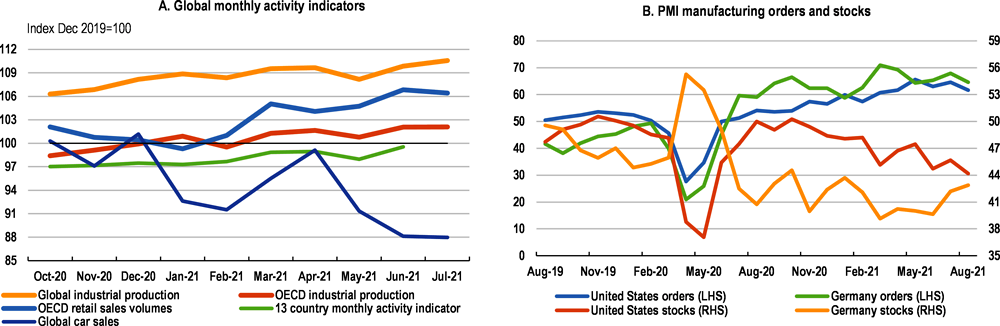

High-frequency activity indicators, such as the Google location-based measures of retail and recreation mobility, suggest global activity continued to strengthen in recent months, helped by improvements in Europe and a marked rebound in both India and Latin America (Figure 2, Panel A). In contrast, mobility weakened in some Asia-Pacific countries, including Australia, in which more stringent containment measures have been reintroduced. However, global PMI survey indicators of business output have softened since May, suggesting some moderation in the pace of the recovery, although they remain at levels consistent with continued global growth (Figure 2, Panel B). The softening was particularly apparent in many Asia-Pacific economies, including China.

Recent activity indicators also show signs of slowing momentum (Figure 3, Panel A). Retail sales spending weakened slightly in July, and global car sales have fallen sharply. Industrial production and global merchandise trade growth have also moderated, with supply shortages in key sectors, such as semi-conductors and shipping, and rising supplier delivery times holding back output in some industries, particularly car production. A widening discrepancy between new order levels and inventory holdings (Figure 3, Panel B) suggests that inventory rebuilding will be an important additional source of demand over time, but it also means that there is reduced capacity to meet new orders immediately, likely pushing up prices.

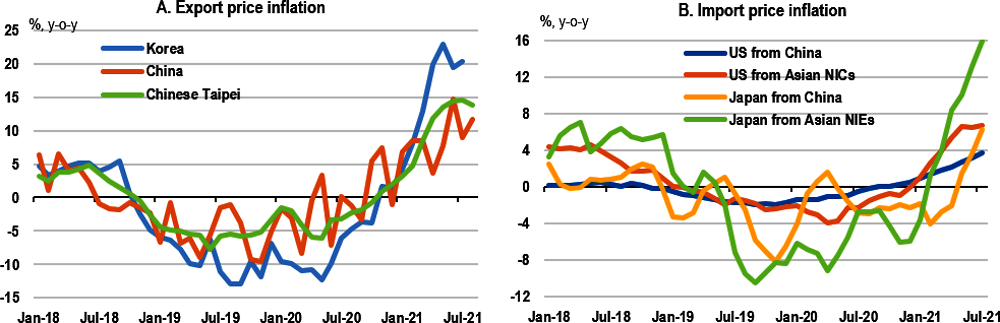

A key near-term uncertainty is the extent to which the Delta variant raises risks of persisting shutdowns in some Asian economies, with adverse downstream consequences for the availability of supplies and the pace of the global recovery. There are already broad-based increases in export prices from many key Asian economies, reflecting both rising input costs from higher global commodity prices, as well as capacity constraints and supply disruptions. This is being mirrored in rising import prices elsewhere (Figure 4), amplified by the tripling of global shipping costs this year (Box 1).

Consumer price inflation has risen sharply

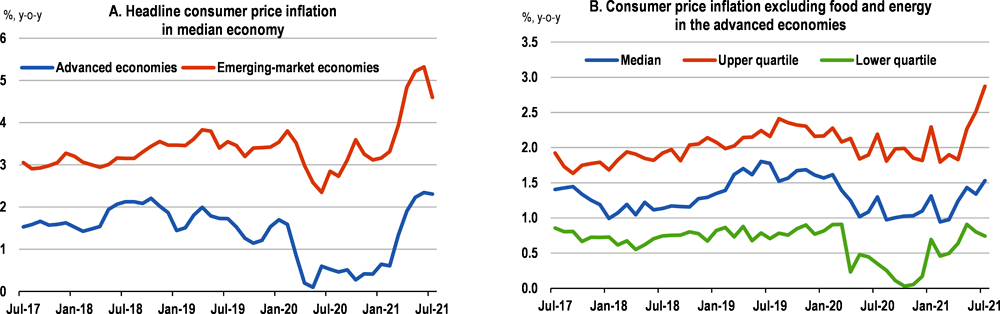

Headline consumer price inflation has also picked up around the world in recent months, pushed up by higher commodity prices, supply-side constraints, stronger consumer demand as economies reopen, and the reversal of some sectoral price declines in the early months of the pandemic. Annual inflation has risen to over 5% in the United States but remains at relatively low rates in many other advanced economies, particularly in Europe and Asia (Figure 5, Panel A). Part of the current rise in inflation reflects base effects, following price declines in the early phase of the pandemic. In many emerging-market economies, high energy and food prices have pushed up inflation, reflecting both strong price increases and the relatively high share of commodities in consumers’ expenditure.

Underlying consumer price inflation (excluding food and energy) has also risen, but in the typical advanced economy it remains at a similar rate to that observed prior to the pandemic (Figure 5, Panel B). Recent price rises have been particularly marked for durable goods where demand has outpaced supply, especially cars, and in some recently reopened contact-intensive service sectors. Overall, however, services price inflation remains modest and below medium-term policy objectives for general inflation in many advanced economies.

Near-term inflation risks are on the upside, particularly if pent-up demand by consumers is stronger than anticipated, or if supply shortages take a long time to overcome. The impact of past increases in shipping costs and commodity prices is already sizeable in the G20 economies, accounting for much of the rise in inflation over the past year, and is likely to linger through much of 2022 even if there are no further cost increases (Box 1). The distribution of observed price changes has also shifted to the upside. An increasing share of items in the price basket (by weight) now have prices rising at rates of 4% or more, particularly in the United States and the United Kingdom. The share of items with declining prices has also fallen (Figure 6), pointing to reduced risks of deflation.

Ultimately, a lasting upward move in inflation from the low rates observed before the pandemic is likely to occur only if wage inflation intensifies substantially, or if inflation expectations drift upwards. Aggregate wage pressures remain moderate, but sizeable increases in wages are occurring in some contact-intensive sectors that have reopened in the United States, such as leisure and hospitality (Figure 7). Signs of labour shortages have also appeared in survey indicators in North America and Europe, especially for small businesses and sectors dependent on seasonal and cross-border workers, pointing to upside risks if labour supply fails to rebound fully.

Policy choices during the pandemic may be contributing to differences in wage pressures across countries in the early stages of the recovery. Active use of job retention schemes helped to preserve employer-employee matches during the pandemic in many countries, enabling firms to reopen and meet stronger demand by raising hours worked. In other countries, including the United States, layoffs broke some existing job matches and raised recruitment difficulties as sectors reopened.

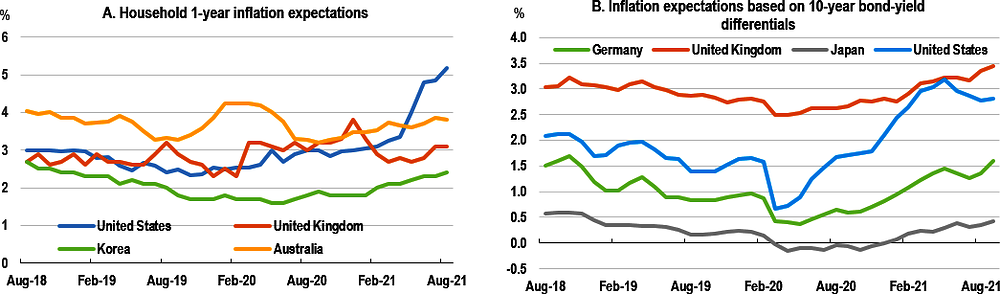

Indicators of inflation expectations have also risen this year, but generally remain moderate outside of the United States. Higher perceived inflation has pushed up one-year-ahead household inflation expectations (Figure 8, Panel A). A potential risk is that a longer period of higher inflation from persisting supply shortages could shift expectations further. Market-based indicators of medium and longer-term inflation expectations derived from bond yield differentials (and inflation swaps) have also risen, though in part this reflects a decline in perceived risks of deflation (Figure 8, Panel B).

The sharp rebound in global demand, supply disruptions and depleted inventories have pushed up commodity prices and transportation costs around the world, particularly in North America and Europe. This box uses empirical estimates for the G20 countries to assess the impact of higher input costs on consumer price inflation. The results suggest that higher commodity prices and shipping costs account for much of the observed pick-up in import price inflation and consumer price inflation seen over the past year, with such effects likely to persist for some time.

Global commodity prices in July and August this year were around 55% higher than a year earlier. Oil prices have rebounded to their pre-pandemic level; metals prices have surged, due to strong demand in China and developed economies; and global food prices have risen to their highest level in a decade, amidst strong demand and weather-related disruptions to production in key food exporting economies (Figure 9, Panel A).

Containerised freight rates have also soared this year, continuing the rise that began in 2020 (Figure 9, Panel A). Spot prices in early September were around 2-3 times the level a year earlier, pushed up by strong demand for consumer goods and supply impediments leading to shipping delays. Vessels are currently used at almost full capacity and containers remain scarce. Congestion at ports and lower productivity at terminals and inland depots have also led to bottlenecks. Distancing rules, temporary closures and reinforced hygiene standards have increased intervals between crew shifts, especially following the spread of the Delta variant in many Asian economies. This has prolonged processing times at ports, hampered the return of containers to Asia and generated delays along the entire shipping chain. This atypical situation appears likely to persist for some time, with significant additional shipping capacity only likely to appear in 2023.

The overall effect of the recent rise in global cost pressures on consumer price inflation in the G20 countries depends on the impact of higher commodity prices and shipping costs on merchandise import price inflation, and the subsequent pass-through to consumer price inflation. Empirical estimates of these two relationships can be used to assess the implications for G20 price inflation of the changes in shipping costs and commodity prices since the start of the pandemic and their potential evolution.

The illustrative estimates suggest that past commodity price and shipping cost increases are currently adding around 11 percentage points to annual merchandise import price inflation in the G20 economies, and around 1½ percentage points to annual consumer price inflation (Figure 9, Panel B). In contrast, these factors were pushing down annual G20 consumer price inflation by around ¼ percentage point in the latter half of 2020. Overall, this suggests that higher commodity prices and shipping costs account for around three-quarters of the 2¼ percentage point change in G20 consumer price inflation since the latter half of 2020.

The central scenario assumes that shipping costs rise by a little over 25% in the fourth quarter of 2021, in line with the growth rates seen in the second and third quarters, before stabilising in the first half of 2022 and then moderating towards their pre-pandemic level as bottlenecks ease and capacity expands. Commodity prices are held flat at their average level in July and August 2021, as conventionally assumed in OECD projections.

Even on this basis, the impact of input price rises on consumer price inflation takes time to fade, reflecting inertia in price adjustments and the impact that past consumer price inflation has on private sector expectations. Such effects are smaller than they once were, especially in advanced economies, reflecting greater monetary policy credibility and the removal of automatic wage-price indexation mechanisms. Nonetheless, persistent but ultimately transient cost pressures can push up inflation for a sustained period.

Significant uncertainty also remains about the outlook for input costs. In an alternative illustrative scenario in which commodity prices rise further in the fourth quarter of 2021 and shipping costs remain elevated throughout 2022, the upward pressure on prices is more persistent (scenario 2 in Figure 9, Panel B). Annual G20 consumer price inflation would be pushed up by around 1¾ percentage points in the fourth quarter of 2021, and by more than 1 percentage point on average in 2022.

The global economic recovery is projected to continue but remain uneven. Vaccination campaigns are proceeding at different rates around the world, and the scale of macroeconomic policy support and the ability to reopen contact-intensive activities differs considerably across economies. Some targeted restrictions on cross-border mobility continue to be needed, and the Delta variant has led to domestic containment measures being re-imposed in many countries with relatively low vaccination rates. This will affect the prospects for a full recovery in all countries.

Global GDP growth is projected to strengthen to 5¾ per cent in 2021 and 4½ per cent in 2022 (Figure 10; Table 1). Near-term momentum has moderated in some countries due to the impact of the Delta variant and temporary supply constraints, but these factors are projected to unwind over time, with shortfalls in growth in the latter half of 2021 being made up through faster recoveries in 2022.

Strong support from macroeconomic policies and accommodative financial conditions should continue to underpin demand in the advanced economies. Higher investment spending in Europe, helped by the Next Generation EU funds, and an assumed additional boost to infrastructure spending in the United States in 2022 are important factors aiding the recovery next year. A rebuilding of depleted inventory levels, improvements in confidence and labour market conditions, and declines in still-elevated household saving ratios will also help to maintain demand next year, offsetting headwinds from a gradual unwinding of pandemic-related fiscal measures. Growth should also pick up in Japan, Korea and Australia as infections abate and sanitary restrictions are lifted.

Prospects in emerging-market economies are mixed. Growth in China is projected to remain close to its pre-pandemic path and commodity exporters are benefitting from high export prices and strong global demand for goods. However, household real incomes have been hit by higher energy and food prices, and risks of further virus outbreaks remain high in many countries where vaccination rates are low. Scope is limited to provide substantial policy support in some countries, particularly where inflation pressures are already rising and policy interest rates have been raised to stabilise expectations. The risk of lasting costs from the pandemic also persists. The output shortfall from the pre-pandemic path at the end of 2022 in the median G20 emerging-market economy is projected to be twice that in the median G20 advanced economy, and particularly high in India and Indonesia.

The annual rate of consumer price inflation in the G20 economies is projected to peak by the fourth quarter of 2021, at around 4½ per cent, before slowly receding next year (Figure 11; Table 2). The impact of commodity prices and rising shipping costs on inflation is projected to ease gradually as supply capacity expands (Box 1) and costs stabilise. Base effects on annual inflation from price declines for some goods and services in 2020 will also fade. Underlying domestic cost pressures should generally remain moderate, with the recovery in labour markets from the pandemic, in terms of employment and hours worked, not yet complete. Nonetheless, inflation is expected to settle at a level above the average rates seen prior to the pandemic. This is welcome after many years of below-target inflation outcomes, but it also points to potential risks.

Inflation has risen particularly quickly in recent months in the United States, Canada and the United Kingdom, and even with some easing of price pressures through next year, average annual inflation in 2022 is projected to be around 2¾-3 per cent. Core consumer price inflation is projected to remain under 2% in the euro area and Japan, but pick up as the recovery progresses. Amongst the major emerging-market economies, upside surprises have been sizeable in Argentina, Brazil, Mexico, Russia and Turkey, and are likely to persist for some time. Tighter monetary conditions in many of these economies should however help to limit domestic pressures on prices, particularly by the latter half of 2022. Consumer price inflation in China remains modest, despite fast-rising producer prices, due to sharp declines in domestic food prices.

The baseline projections are conditional on the evolution of the pandemic, the pace and global spread of vaccine deployment, and the reopening of all economies over time. The distribution of risks is now better balanced than a year ago, but significant uncertainty remains.

On the upside, faster global progress in deploying effective vaccines would boost confidence and spending by consumers and companies, and encourage a greater decline in household saving rates than built into the baseline projections. In a scenario of this kind, starting from the fourth quarter of 2021, with household saving rates reduced by a further 2 percentage points in the typical advanced economy, global output could return fully to the path expected prior to the pandemic (Figure 12, Panel A). Global GDP growth would be raised substantially, to over 6¼ per cent in 2022 and in the typical economy unemployment would return to pre-pandemic rates (Figure 12, Panel B). However, stronger demand would also put upward pressures on inflation, potentially pushing up G20 price inflation by over ¾ percentage point next year.

A potential consequence of this scenario is that stronger inflation pressure in 2022 could raise financial market expectations of an earlier start to monetary policy normalisation, and create difficulties for some emerging-market economies. Clear guidance by the monetary authorities that the additional inflation pressures were only temporary would help to anchor inflation expectations and limit financial market repricing.

The major downside risk is that the speed of vaccine deployment, and the effectiveness of existing vaccines, will not stop the transmission of more contagious variants of concern that then require new or modified vaccines. In such circumstances, stricter containment measures might need to be used again, confidence and private sector spending would be weaker than in the baseline, and some capital would be scrapped. In such a scenario, output would remain weaker than the pre-crisis path for an extended period. World GDP growth could drop to under 3% in 2022, with G20 inflation also being pushed below 3% and unemployment rising further.

Such downside shocks can be cushioned by macroeconomic policies. In the scenario shown, the automatic fiscal stabilisers provide support in all countries, and policy interest rates are allowed to decline where space exists. Additional discretionary fiscal actions could also be undertaken to support demand, but are not included in the scenario.

Governments need to deploy vaccinations as quickly as possible throughout the world to save lives, preserve incomes and bring the virus under control. The recovery will remain precarious and uncertain in all countries until this is achieved. Failure to ensure the global suppression of the virus raises the risks that further new, more-transmissible variants continue to appear, or that the number of cases surges again in the Northern hemisphere during the winter months, with containment measures having to be reintroduced.

Stronger international efforts are needed to provide low-income countries with the resources needed to vaccinate their populations for their own and global benefits. These include vaccine supply and assistance to help overcome domestic logistical hurdles to vaccine deployment. Effective multilateral action is also required to share knowledge, medical and financial resources, and avoid harmful bans to trade. Such bans would be self-defeating given the strong cross-border linkages in supply chains for vaccines and healthcare products.

Macroeconomic policies should remain supportive

Macroeconomic policy support continues to be needed whilst the near-term outlook is still uncertain and labour markets have not yet recovered, with the mix of policies contingent on economic developments in each country. Clear guidance from policymakers is required about the expected path towards medium-term objectives and the likely sequencing of future policy changes to help anchor expectations, maintain investor confidence and ensure adequate support for the economy.

Where the recovery is well advanced and vaccination efforts are almost complete, the focus should be increasingly on medium-term objectives, rather than emergency policy support. In other countries, where the recovery or the pace of vaccinations is less advanced, and containment measures are still being deployed, targeted policy support continues to be needed to help support demand and the incomes of workers and companies in contact-intensive sectors.

Clear forward guidance is needed to help maintain monetary policy accommodation

Monetary policy is still very accommodative in the major advanced economies, as appropriate until there are clear signs of durable progress towards medium-term policy objectives. Policy interest rates have been unchanged, with the exception of Korea, and many central banks continue to provide additional monetary stimulus through asset purchase programmes, even where the pace of purchases is now moderating.

Temporary overshooting of headline inflation from transient capacity pressures should continue to be tolerated provided underlying price developments are contained and inflation expectations remain well anchored. Maintaining accommodative monetary policy for longer will be easier for central banks that have already announced that they would seek to overshoot the inflation target for some time, including the US Federal Reserve. Nonetheless, clear communication is needed about the horizon and extent to which any such overshooting will be tolerated, together with guidance about the planned timing and sequencing of eventual moves towards policy normalisation.

Key steps towards eventual normalisation should be sequential, starting with removal of emergency measures to ensure well-functioning financial markets, as has already begun, an eventual stabilisation of central bank balance sheets (by only reinvesting the proceeds from maturing assets), and subsequently increases in policy interest rates. Such steps should be well communicated and state-dependent, guided by financial conditions, sustained improvements in labour markets, signs of durable inflation pressures and the support being provided by fiscal policy. In the absence of clear guidance, a key risk is that moves to slow asset purchases and initial increases in policy rates trigger significant repricing in financial markets by changing expectations of the timing of future changes in interest rates.

Higher long-term interest rates in the advanced economies can further restrict the room for manoeuvre in many emerging-market economies, particularly ones facing strong upward pressure on inflation from commodity price increases and past currency depreciation. In countries with strong macroeconomic policy frameworks and a broad local investor base, accommodative monetary policy can be maintained provided inflation expectations remain well anchored. In others, further policy rate increases may be required to ensure stability and mitigate against potential adverse spillovers from financial market risks.

Fiscal policy support should be contingent on the state of the economy

Fiscal policy support should remain flexible and contingent on the state of the economy. The strong fiscal stimulus being implemented this year, including in the United States and the euro area, continues to provide impetus for the recovery by supporting demand, preserving incomes, and ensuring ample spending on healthcare and vaccinations.

A premature and abrupt withdrawal of policy support should be avoided whilst the near-term outlook is still uncertain. Any moderation in fiscal spending in 2022 should come from contingent reductions in crisis-related spending as the economy strengthens and vaccination coverage expands, rather than substantial discretionary consolidation measures. Debt service burdens remain low, helped by the space provided by accommodative monetary policy, despite high deficits and rising debt levels. This provides room while interest rates remain low for sustained fiscal support to ensure a full and durable recovery.

As the recovery progresses, the focus for policy should increasingly move towards improving the prospects for sustainable and equitable growth, including through additional public investment in health, digital and low-carbon infrastructure and changes in the composition of taxation. Policy actions to ensure debt sustainability should be a priority only once the recovery is well advanced and labour market conditions have returned fully to pre-pandemic levels. Credible fiscal frameworks that provide clear guidance about the medium-term path towards sustainability, and the likely policy changes along that path, would help to maintain confidence and enhance the transparency of budgetary choices.

The fiscal situation varies considerably among emerging-market economies and developing countries, but many face difficult trade-offs between supporting incomes, providing adequate resources for the deployment of vaccines, and ensuring debt sustainability. Robust policy frameworks, improved revenue collection, and the reorientation of spending towards health and social priorities would help to maintain investor confidence and strengthen efforts to reduce the pandemic-related surge in poverty. Longer government debt maturities would reduce the impact of any fluctuations in interest rates. Enhanced international support for vaccinations and a stronger global safety net would also bolster confidence in these economies.

Macroeconomic policy support needs to be accompanied by effective and well-targeted structural reforms

In virtually all economies, the pandemic provoked a deep recession and potentially lasting structural changes. Demand has fallen sharply in some sectors but surged in others, including services that can be supplied digitally from different locations, and labour supply and cross-border trade have both been affected. In the face of such shocks, resources are not reallocated immediately or without cost. Mismatches in the labour market are almost certain; available workers may not have the right skills for new jobs, they may be where job prospects are not improving, or they may not know of the opportunities. It remains unknown how long lasting such effects will be. Nonetheless, the shocks underline the importance of policies to facilitate the reallocation of resources between different sectors and activities.

The need to accommodate the sectoral shifts arising from the pandemic at minimum cost, and address the potential long-term costs from the disruption to schooling during the pandemic, adds to the pre-COVID-19 longer-term challenges that require structural policy action. Many OECD economies were characterised by high and often growing inequalities of income and/or wealth, and all were faced with a host of challenges arising from the digitalisation of the economy and the need to address the threat of climate change. Governments need to seize the opportunity at a time when macroeconomic policies are supportive and demand is rising quickly to accelerate reforms. This will ensure that the extraordinary support mobilised to combat the current crisis, including plans to boost public investment, also advances longer-term objectives.

One priority is to ensure that support continues to go to the poorest households, especially as assistance is withdrawn and becomes more targeted. The effectiveness of targeted measures could be increased by setting clear state-contingent criteria, such as linking the scale and availability of the resources used to changes in labour market conditions.

The substantial fiscal resources being mobilised to support the economy during the pandemic can also be redirected to the digital and low-carbon transformations as the need for emergency income support diminishes. Improving broadband connectivity, helping firms develop online business models and enhancing digital skills are all areas in which further reforms would accelerate the adoption of digital technologies. Well-designed infrastructure investment projects, including expanded and modernised electricity grids and spending on renewables (coordinated across countries where relevant), and projects with shorter payback periods, such as more energy-efficient buildings and appliances, can also serve the twin objectives of closing employment gaps and achieving climate-related goals.

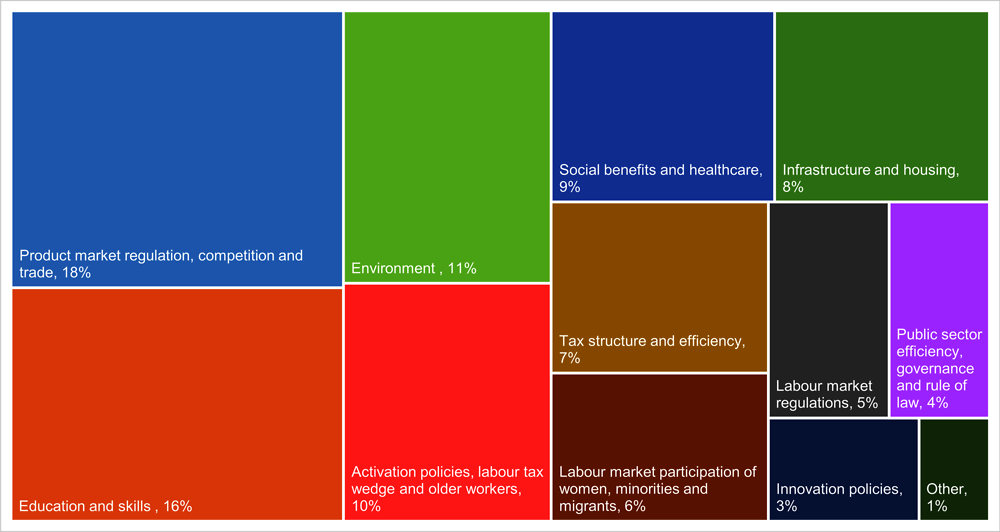

The structural policy recommendations to OECD member and key partner countries in the 2021 edition of Going for Growth cover a wide range of areas (Figure 13). Nearly two-fifths of the recommendations are for reforms to improve the functioning of labour markets (via changes in labour market regulation, education and skills, activation policies, and measures to raise the labour force participation of women, minorities and migrants). Substantial additional investments are needed in active labour market programmes, including employment services to help jobseekers find a job, and enhanced vocational education and training are required to create new opportunities for displaced workers, lower-skilled workers, and those still on reduced working hours. Participation in training while on reduced working hours, which has been encouraged in a number of OECD economies, can help workers improve the viability of their current job or improve the prospect of finding a new job. A particular challenge is to organise training in such a way that it can be combined with part-time work and irregular work schedules. This is easier when training courses are targeted at individuals rather than groups, delivered in a flexible manner through online teaching tools and their duration is relatively short.